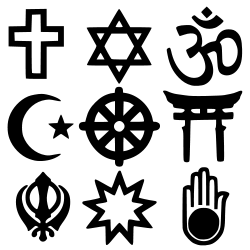

Religious symbols: Christianity, Islam, Isese, Hinduism, Judaism, Baha’i, Eckankar, Buddhism, Jainism, Wicca, Unitarian Universalism, Sikhism, Taoism, Thelema, Tenrikyo, Shinto

Religion is a range of social-cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural, transcendental, and spiritual elements[1]—although there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion.[2][3] Different religions may or may not contain various elements ranging from the divine,[4] sacredness,[5] faith,[6] and a supernatural being or beings.[7]

Religious practices may include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration (of deities or saints), sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, matrimonial and funerary services, meditation, prayer, music, art, dance or public service. Religions have sacred histories and narratives, which may be preserved in sacred texts, symbols and holy places, that primarily aim to give life meaning. Religions may contain symbolic tales that may attempt to explain the origin of life, the universe, and other phenomena; some followers believe these to be true stories. Traditionally, both faith and reason have been considered sources of religious beliefs.[8]

There are an estimated 10,000 distinct religions worldwide,[9] though nearly all of them have regionally based, relatively small followings. Four religions—Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism—account for over 77% of the world’s population, and 92% of the world either follows one of those four religions or identifies as nonreligious,[10] meaning that the remaining 9,000+ faiths account for only 8% of the population combined. The religiously unaffiliated demographic includes those who do not identify with any particular religion, atheists, and agnostics, although many in the demographic still have various religious beliefs.[11] A portion of the population, mostly located in Africa and Asia, are members of new religious movements.[12] Scholars have indicated that global religiosity may be increasing due to religious countries having generally higher birth rates.[13]

The study of religion comprises a wide variety of academic disciplines, including theology, philosophy of religion, comparative religion, and social scientific studies. Theories of religion offer various explanations for its origins and workings, including the ontological foundations of religious being and belief.[14]

Concept and etymology

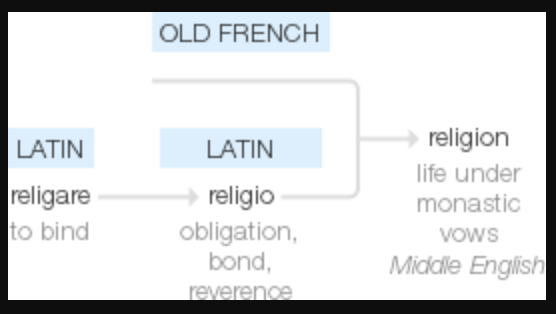

The term religion comes from both Old French and Anglo-Norman (1200s AD) and means respect for sense of right, moral obligation, sanctity, what is sacred, reverence for the gods.[15][16] It is ultimately derived from the Latin word religiō. According to Roman philosopher Cicero, religiō comes from relegere: re (meaning «again») + lego (meaning «read»), where lego is in the sense of «go over», «choose», or «consider carefully». Contrarily, some modern scholars such as Tom Harpur and Joseph Campbell have argued that religiō is derived from religare: re (meaning «again») + ligare («bind» or «connect»), which was made prominent by St. Augustine following the interpretation given by Lactantius in Divinae institutiones, IV, 28.[17][18] The medieval usage alternates with order in designating bonded communities like those of monastic orders: «we hear of the ‘religion’ of the Golden Fleece, of a knight ‘of the religion of Avys'».[19]

Religiō

In classic antiquity, religiō broadly meant conscientiousness, sense of right, moral obligation, or duty to anything.[20] In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin root religiō was understood as an individual virtue of worship in mundane contexts; never as doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.[21][22] In general, religiō referred to broad social obligations towards anything including family, neighbors, rulers, and even towards God.[23] Religiō was most often used by the ancient Romans not in the context of a relation towards gods, but as a range of general emotions which arose from heightened attention in any mundane context such as hesitation, caution, anxiety, or fear, as well as feelings of being bound, restricted, or inhibited.[24] The term was also closely related to other terms like scrupulus (which meant «very precisely»), and some Roman authors related the term superstitio (which meant too much fear or anxiety or shame) to religiō at times.[24] When religiō came into English around the 1200s as religion, it took the meaning of «life bound by monastic vows» or monastic orders.[19][23] The compartmentalized concept of religion, where religious and worldly things were separated, was not used before the 1500s.[23] The concept of religion was first used in the 1500s to distinguish the domain of the church and the domain of civil authorities; the Peace of Augsburg marks such instance,[23] which has been described by Christian Reus-Smit as «the first step on the road toward a European system of sovereign states.»[25]

Roman general Julius Caesar used religiō to mean «obligation of an oath» when discussing captured soldiers making an oath to their captors.[26] Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder used the term religiō to describe the apparent respect given by elephants to the night sky.[27] Cicero used religiō as being related to cultum deorum (worship of the gods).[28]

Threskeia

In Ancient Greece, the Greek term threskeia (θρησκεία) was loosely translated into Latin as religiō in late antiquity. Threskeia was sparsely used in classical Greece but became more frequently used in the writings of Josephus in the 1st century AD. It was used in mundane contexts and could mean multiple things from respectful fear to excessive or harmfully distracting practices of others, to cultic practices. It was often contrasted with the Greek word deisidaimonia, which meant too much fear.[29]

Religion and religions

The modern concept of religion, as an abstraction that entails distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines, is a recent invention in the English language. Such usage began with texts from the 17th century due to events such as the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation and globalization in the Age of Exploration, which involved contact with numerous foreign cultures with non-European languages.[21][22][30] Some argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply the term religion to non-Western cultures,[31][32] while some followers of various faiths rebuke using the word to describe their own belief system.[33]

The concept of religion was formed in the 16th and 17th centuries,[34][35] despite the fact that ancient sacred texts like the Bible, the Quran, and others did not have a word or even a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.[36][37] For example, there is no precise equivalent of religion in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[38] One of its central concepts is halakha, meaning the walk or path sometimes translated as law, which guides religious practice and belief and many aspects of daily life.[39] Even though the beliefs and traditions of Judaism are found in the ancient world, ancient Jews saw Jewish identity as being about an ethnic or national identity and did not entail a compulsory belief system or regulated rituals.[40] In the 1st century AD, Josephus had used the Greek term ioudaismos (Judaism) as an ethnic term and was not linked to modern abstract concepts of religion or a set of beliefs.[3] The very concept of «Judaism» was invented by the Christian Church,[41] and it was in the 19th century that Jews began to see their ancestral culture as a religion analogous to Christianity.[40] The Greek word threskeia, which was used by Greek writers such as Herodotus and Josephus, is found in the New Testament. Threskeia is sometimes translated as «religion» in today’s translations, but the term was understood as generic «worship» well into the medieval period.[3] In the Quran, the Arabic word din is often translated as religion in modern translations, but up to the mid-1600s translators expressed din as «law».[3]

The Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as religion,[42] also means law. Throughout classical South Asia, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between imperial law and universal or Buddha law, but these later became independent sources of power.[43][44]

Though traditions, sacred texts, and practices have existed throughout time, most cultures did not align with Western conceptions of religion since they did not separate everyday life from the sacred. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the terms Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Confucianism, and world religions first entered the English language.[45][46][47] Native Americans were also thought of as not having religions and also had no word for religion in their languages either.[46][48] No one self-identified as a Hindu or Buddhist or other similar terms before the 1800s.[49] «Hindu» has historically been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for people indigenous to the Indian subcontinent.[50][51] Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of religion since there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding, among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with this idea.[52][53]

According to the philologist Max Müller in the 19th century, the root of the English word religion, the Latin religiō, was originally used to mean only reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety (which Cicero further derived to mean diligence).[54][55] Müller characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt, Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only called law.[56]

Definition

Religious symbols from left to right, top to bottom: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, the Baháʼí Faith, Eckankar, Sikhism, Jainism, Wicca, Unitarian Universalism, Shinto, Taoism, Thelema, Tenrikyo, and Zoroastrianism

Scholars have failed to agree on a definition of religion. There are, however, two general definition systems: the sociological/functional and the phenomenological/philosophical.[57][58][59][60][61]

Modern Western

The concept of religion originated in the modern era in the West.[32] Parallel concepts are not found in many current and past cultures; there is no equivalent term for religion in many languages.[3][23] Scholars have found it difficult to develop a consistent definition, with some giving up on the possibility of a definition.[62][63] Others argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply it to non-Western cultures.[31][32]

An increasing number of scholars have expressed reservations about ever defining the essence of religion.[64] They observe that the way the concept today is used is a particularly modern construct that would not have been understood through much of history and in many cultures outside the West (or even in the West until after the Peace of Westphalia).[65] The MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions states:

The very attempt to define religion, to find some distinctive or possibly unique essence or set of qualities that distinguish the religious from the remainder of human life, is primarily a Western concern. The attempt is a natural consequence of the Western speculative, intellectualistic, and scientific disposition. It is also the product of the dominant Western religious mode, what is called the Judeo-Christian climate or, more accurately, the theistic inheritance from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The theistic form of belief in this tradition, even when downgraded culturally, is formative of the dichotomous Western view of religion. That is, the basic structure of theism is essentially a distinction between a transcendent deity and all else, between the creator and his creation, between God and man.[66]

The anthropologist Clifford Geertz defined religion as a

… system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.»[67]

Alluding perhaps to Tylor’s «deeper motive», Geertz remarked that

… we have very little idea of how, in empirical terms, this particular miracle is accomplished. We just know that it is done, annually, weekly, daily, for some people almost hourly; and we have an enormous ethnographic literature to demonstrate it.[68]

The theologian Antoine Vergote took the term supernatural simply to mean whatever transcends the powers of nature or human agency. He also emphasized the cultural reality of religion, which he defined as

… the entirety of the linguistic expressions, emotions and, actions and signs that refer to a supernatural being or supernatural beings.[7]

Peter Mandaville and Paul James intended to get away from the modernist dualisms or dichotomous understandings of immanence/transcendence, spirituality/materialism, and sacredness/secularity. They define religion as

… a relatively-bounded system of beliefs, symbols and practices that addresses the nature of existence, and in which communion with others and Otherness is lived as if it both takes in and spiritually transcends socially-grounded ontologies of time, space, embodiment and knowing.[69]

According to the MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions, there is an experiential aspect to religion which can be found in almost every culture:

… almost every known culture [has] a depth dimension in cultural experiences … toward some sort of ultimacy and transcendence that will provide norms and power for the rest of life. When more or less distinct patterns of behavior are built around this depth dimension in a culture, this structure constitutes religion in its historically recognizable form. Religion is the organization of life around the depth dimensions of experience—varied in form, completeness, and clarity in accordance with the environing culture.[70]

Classical

Budazhap Shiretorov (Будажап Цыреторов), the head shaman of the religious community Altan Serge (Алтан Сэргэ) in Buryatia

Friedrich Schleiermacher in the late 18th century defined religion as das schlechthinnige Abhängigkeitsgefühl, commonly translated as «the feeling of absolute dependence».[71]

His contemporary Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel disagreed thoroughly, defining religion as «the Divine Spirit becoming conscious of Himself through the finite spirit.»[72]

Edward Burnett Tylor defined religion in 1871 as «the belief in spiritual beings».[73] He argued that narrowing the definition to mean the belief in a supreme deity or judgment after death or idolatry and so on, would exclude many peoples from the category of religious, and thus «has the fault of identifying religion rather with particular developments than with the deeper motive which underlies them». He also argued that the belief in spiritual beings exists in all known societies.

In his book The Varieties of Religious Experience, the psychologist William James defined religion as «the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine».[4] By the term divine James meant «any object that is godlike, whether it be a concrete deity or not»[74] to which the individual feels impelled to respond with solemnity and gravity.[75]

Sociologist Émile Durkheim, in his seminal book The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, defined religion as a «unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things».[5] By sacred things he meant things «set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them». Sacred things are not, however, limited to gods or spirits.[note 1] On the contrary, a sacred thing can be «a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word, anything can be sacred».[76] Religious beliefs, myths, dogmas and legends are the representations that express the nature of these sacred things, and the virtues and powers which are attributed to them.[77]

Echoes of James’ and Durkheim’s definitions are to be found in the writings of, for example, Frederick Ferré who defined religion as «one’s way of valuing most comprehensively and intensively».[78] Similarly, for the theologian Paul Tillich, faith is «the state of being ultimately concerned»,[6] which «is itself religion. Religion is the substance, the ground, and the depth of man’s spiritual life.»[79]

When religion is seen in terms of sacred, divine, intensive valuing, or ultimate concern, then it is possible to understand why scientific findings and philosophical criticisms (e.g., those made by Richard Dawkins) do not necessarily disturb its adherents.[80]

Aspects

Beliefs

Traditionally, faith, in addition to reason, has been considered a source of religious beliefs. The interplay between faith and reason, and their use as perceived support for religious beliefs, have been a subject of interest to philosophers and theologians.[8] The origin of religious belief as such is an open question, with possible explanations including awareness of individual death, a sense of community, and dreams.[81]

Mythology

The word myth has several meanings.

- A traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon;

- A person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence; or

- A metaphor for the spiritual potentiality in the human being.[82]

Ancient polytheistic religions, such as those of Greece, Rome, and Scandinavia, are usually categorized under the heading of mythology. Religions of pre-industrial peoples, or cultures in development, are similarly called myths in the anthropology of religion. The term myth can be used pejoratively by both religious and non-religious people. By defining another person’s religious stories and beliefs as mythology, one implies that they are less real or true than one’s own religious stories and beliefs. Joseph Campbell remarked, «Mythology is often thought of as other people’s religions, and religion can be defined as misinterpreted mythology.»[83]

In sociology, however, the term myth has a non-pejorative meaning. There, myth is defined as a story that is important for the group, whether or not it is objectively or provably true.[84] Examples include the resurrection of their real-life founder Jesus, which, to Christians, explains the means by which they are freed from sin, is symbolic of the power of life over death, and is also said to be a historical event. But from a mythological outlook, whether or not the event actually occurred is unimportant. Instead, the symbolism of the death of an old life and the start of a new life is most significant. Religious believers may or may not accept such symbolic interpretations.

Practices

The practices of a religion may include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration of a deity (god or goddess), sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, funerary services, matrimonial services, meditation, prayer, religious music, religious art, sacred dance, public service, or other aspects of human culture.[85]

Religions have a societal basis, either as a living tradition which is carried by lay participants, or with an organized clergy, and a definition of what constitutes adherence or membership.

Academic study

A number of disciplines study the phenomenon of religion: theology, comparative religion, history of religion, evolutionary origin of religions, anthropology of religion, psychology of religion (including neuroscience of religion and evolutionary psychology of religion), law and religion, and sociology of religion.

Daniel L. Pals mentions eight classical theories of religion, focusing on various aspects of religion: animism and magic, by E.B. Tylor and J.G. Frazer; the psycho-analytic approach of Sigmund Freud; and further Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, Max Weber, Mircea Eliade, E.E. Evans-Pritchard, and Clifford Geertz.[86]

Michael Stausberg gives an overview of contemporary theories of religion, including cognitive and biological approaches.[87]

Theories

Sociological and anthropological theories of religion generally attempt to explain the origin and function of religion.[88] These theories define what they present as universal characteristics of religious belief and practice.

Origins and development

The origin of religion is uncertain. There are a number of theories regarding the subsequent origins of religious practices.

According to anthropologists John Monaghan and Peter Just, «Many of the great world religions appear to have begun as revitalization movements of some sort, as the vision of a charismatic prophet fires the imaginations of people seeking a more comprehensive answer to their problems than they feel is provided by everyday beliefs. Charismatic individuals have emerged at many times and places in the world. It seems that the key to long-term success—and many movements come and go with little long-term effect—has relatively little to do with the prophets, who appear with surprising regularity, but more to do with the development of a group of supporters who are able to institutionalize the movement.»[89]

The development of religion has taken different forms in different cultures. Some religions place an emphasis on belief, while others emphasize practice. Some religions focus on the subjective experience of the religious individual, while others consider the activities of the religious community to be most important. Some religions claim to be universal, believing their laws and cosmology to be binding for everyone, while others are intended to be practiced only by a closely defined or localized group. In many places, religion has been associated with public institutions such as education, hospitals, the family, government, and political hierarchies.[90]

Anthropologists John Monoghan and Peter Just state that, «it seems apparent that one thing religion or belief helps us do is deal with problems of human life that are significant, persistent, and intolerable. One important way in which religious beliefs accomplish this is by providing a set of ideas about how and why the world is put together that allows people to accommodate anxieties and deal with misfortune.»[90]

Cultural system

While religion is difficult to define, one standard model of religion, used in religious studies courses, was proposed by Clifford Geertz, who simply called it a «cultural system».[91] A critique of Geertz’s model by Talal Asad categorized religion as «an anthropological category».[92] Richard Niebuhr’s (1894–1962) five-fold classification of the relationship between Christ and culture, however, indicates that religion and culture can be seen as two separate systems, though with some interplay.[93]

One modern academic theory of religion, social constructionism, says that religion is a modern concept that suggests all spiritual practice and worship follows a model similar to the Abrahamic religions as an orientation system that helps to interpret reality and define human beings.[94] Among the main proponents of this theory of religion are Daniel Dubuisson, Timothy Fitzgerald, Talal Asad, and Jason Ānanda Josephson. The social constructionists argue that religion is a modern concept that developed from Christianity and was then applied inappropriately to non-Western cultures.

Cognitive science

Cognitive science of religion is the study of religious thought and behavior from the perspective of the cognitive and evolutionary sciences.[95] The field employs methods and theories from a very broad range of disciplines, including: cognitive psychology, evolutionary psychology, cognitive anthropology, artificial intelligence, cognitive neuroscience, neurobiology, zoology, and ethology. Scholars in this field seek to explain how human minds acquire, generate, and transmit religious thoughts, practices, and schemas by means of ordinary cognitive capacities.

Hallucinations and delusions related to religious content occurs in about 60% of people with schizophrenia. While this number varies across cultures, this had led to theories about a number of influential religious phenomena and possible relation to psychotic disorders. A number of prophetic experiences are consistent with psychotic symptoms, although retrospective diagnoses are practically impossible.[96][97][98] Schizophrenic episodes are also experienced by people who do not have belief in gods.[99]

Religious content is also common in temporal lobe epilepsy, and obsessive–compulsive disorder.[100][101] Atheistic content is also found to be common with temporal lobe epilepsy.[102]

Comparativism

Comparative religion is the branch of the study of religions concerned with the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices of the world’s religions. In general, the comparative study of religion yields a deeper understanding of the fundamental philosophical concerns of religion such as ethics, metaphysics, and the nature and form of salvation. Studying such material is meant to give one a richer and more sophisticated understanding of human beliefs and practices regarding the sacred, numinous, spiritual and divine.[103]

In the field of comparative religion, a common geographical classification[104] of the main world religions includes Middle Eastern religions (including Zoroastrianism and Iranian religions), Indian religions, East Asian religions, African religions, American religions, Oceanic religions, and classical Hellenistic religions.[104]

Classification

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the academic practice of comparative religion divided religious belief into philosophically defined categories called world religions. Some academics studying the subject have divided religions into three broad categories:

- world religions, a term which refers to transcultural, international religions;

- indigenous religions, which refers to smaller, culture-specific or nation-specific religious groups; and

- new religious movements, which refers to recently developed religions.[105]

Some recent scholarship has argued that not all types of religion are necessarily separated by mutually exclusive philosophies, and furthermore that the utility of ascribing a practice to a certain philosophy, or even calling a given practice religious, rather than cultural, political, or social in nature, is limited.[106][107][108] The current state of psychological study about the nature of religiousness suggests that it is better to refer to religion as a largely invariant phenomenon that should be distinguished from cultural norms (i.e. religions).[109][clarification needed]

Morphological classification

Some scholars classify religions as either universal religions that seek worldwide acceptance and actively look for new converts, such as Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Jainism, while ethnic religions are identified with a particular ethnic group and do not seek converts.[110][111] Others reject the distinction, pointing out that all religious practices, whatever their philosophical origin, are ethnic because they come from a particular culture.[112][113][114]

Demographic classification

The five largest religious groups by world population, estimated to account for 5.8 billion people and 84% of the population, are Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism (with the relative numbers for Buddhism and Hinduism dependent on the extent of syncretism) and traditional folk religion.

| Five largest religions | 2015 (billion)[115] | 2015 (%) | Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 2.3 | 31.2% | Christianity by country |

| Islam | 1.8 | 24.1% | Islam by country |

| Hinduism | 1.1 | 15.1% | Hinduism by country |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | 6.9% | Buddhism by country |

| Folk Religion | 0.4 | 5.7% | |

| Total | 6.1 | 83% | Religions by country |

A global poll in 2012 surveyed 57 countries and reported that 59% of the world’s population identified as religious, 23% as not religious, 13% as convinced atheists, and also a 9% decrease in identification as religious when compared to the 2005 average from 39 countries.[116] A follow-up poll in 2015 found that 63% of the globe identified as religious, 22% as not religious, and 11% as convinced atheists.[117] On average, women are more religious than men.[118] Some people follow multiple religions or multiple religious principles at the same time, regardless of whether or not the religious principles they follow traditionally allow for syncretism.[119][120][121] A 2017 Pew projection suggests that Islam will overtake Christianity as the plurality religion by 2075. Unaffiliated populations are projected to drop, even when taking disaffiliation rates into account, due to differences in birth rates.[122][123]

Scholars have indicated that global religiosity may be increasing due to religious countries having higher birth rates in general.[124]

Specific religions

Abrahamic

Abrahamic religions are monotheistic religions which believe they descend from Abraham.

Judaism

The Torah is the primary sacred text of Judaism.

Judaism is the oldest Abrahamic religion, originating in the people of ancient Israel and Judah.[125] The Torah is its foundational text, and is part of the larger text known as the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible. It is supplemented by oral tradition, set down in written form in later texts such as the Midrash and the Talmud. Judaism includes a wide corpus of texts, practices, theological positions, and forms of organization. Within Judaism there are a variety of movements, most of which emerged from Rabbinic Judaism, which holds that God revealed his laws and commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai in the form of both the Written and Oral Torah; historically, this assertion was challenged by various groups. The Jewish people were scattered after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. Today there are about 13 million Jews, about 40 per cent living in Israel and 40 per cent in the United States.[126] The largest Jewish religious movements are Orthodox Judaism (Haredi Judaism and Modern Orthodox Judaism), Conservative Judaism and Reform Judaism.[125]

Christianity

Jesus is the central figure of Christianity.

Christianity is based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth (1st century) as presented in the New Testament.[127] The Christian faith is essentially faith in Jesus as the Christ,[127] the Son of God, and as Savior and Lord. Almost all Christians believe in the Trinity, which teaches the unity of Father, Son (Jesus Christ), and Holy Spirit as three persons in one Godhead. Most Christians can describe their faith with the Nicene Creed. As the religion of Byzantine Empire in the first millennium and of Western Europe during the time of colonization, Christianity has been propagated throughout the world via missionary work.[128][129][130] It is the world’s largest religion, with about 2.3 billion followers as of 2015.[131] The main divisions of Christianity are, according to the number of adherents:[132]

- The Catholic Church, led by the Bishop of Rome and the bishops worldwide in communion with him, is a communion of 24 Churches sui iuris, including the Latin Church and 23 Eastern Catholic churches, such as the Maronite Catholic Church.[132]

- Eastern Christianity, which include Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Church of the East.

- Protestantism, separated from the Catholic Church in the 16th-century Protestant Reformation and is split into thousands of denominations. Major branches of Protestantism include Anglicanism, Baptists, Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Methodism, though each of these contain many different denominations or groups.[132]

There are also smaller groups, including:

- Restorationism, the belief that Christianity should be restored (as opposed to reformed) along the lines of what is known about the apostolic early church.

- Latter-day Saint movement, founded by Joseph Smith in the late 1820s.

- Jehovah’s Witnesses, founded in the late 1870s by Charles Taze Russell.

Islam

Islam is a monotheistic[133] religion based on the Quran,[133] one of the holy books considered by Muslims to be revealed by God, and on the teachings (hadith) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, a major political and religious figure of the 7th century CE. Islam is based on the unity of all religious philosophies and accepts all of the Abrahamic prophets of Judaism, Christianity and other Abrahamic religions before Muhammad. It is the most widely practiced religion of Southeast Asia, North Africa, Western Asia, and Central Asia, while Muslim-majority countries also exist in parts of South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Europe. There are also several Islamic republics, including Iran, Pakistan, Mauritania, and Afghanistan.

- Sunni Islam is the largest denomination within Islam and follows the Qur’an, the ahadith (ar: plural of Hadith) which record the sunnah, whilst placing emphasis on the sahabah.

- Shia Islam is the second largest denomination of Islam and its adherents believe that Ali succeeded Muhammad and further places emphasis on Muhammad’s family.

- There are also Muslim revivalist movements such as Muwahhidism and Salafism.

Other denominations of Islam include Nation of Islam, Ibadi, Sufism, Quranism, Mahdavia, and non-denominational Muslims. Wahhabism is the dominant Muslim schools of thought in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Other

Whilst Judaism, Christianity and Islam are commonly seen as the only three Abrahamic faiths, there are smaller and newer traditions which lay claim to the designation as well.[134]

The Baháʼí Lotus Temple in Delhi

For example, the Baháʼí Faith is a new religious movement that has links to the major Abrahamic religions as well as other religions (e.g. of Eastern philosophy). Founded in 19th-century Iran, it teaches the unity of all religious philosophies[135] and accepts all of the prophets of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as well as additional prophets (Buddha, Mahavira), including its founder Bahá’u’lláh. It is an offshoot of Bábism. One of its divisions is the Orthodox Baháʼí Faith.[136]: 48–49

Even smaller regional Abrahamic groups also exist, including Samaritanism (primarily in Israel and the State of Palestine), the Rastafari movement (primarily in Jamaica), and Druze (primarily in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel). The Druze faith originally developed out of Isma’ilism, and it has sometimes been considered an Islamic school by some Islamic authorities, but Druze themselves do not identify as Muslims.[137][138][139] Mandaeism, sometimes also known as Sabianism (after the mysterious Sabians mentioned in the Quran, a name historically claimed by several religious groups),[140] is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion.[141]: 4 [142]: 1 Its adherents, the Mandaeans, consider John the Baptist to be their chief prophet.[141] Mandaeans are the last surviving Gnostics from antiquity.[143]

East Asian

East Asian religions (also known as Far Eastern religions or Taoic religions) consist of several religions of East Asia which make use of the concept of Tao (in Chinese), Dō (in Japanese or Korean) or Đạo (in Vietnamese). They include:

Taoism and Confucianism

- Taoism and Confucianism, as well as Korean, Vietnamese, and Japanese religion influenced by Chinese thought.

Folk religions

- Chinese folk religion: the indigenous religions of the Han Chinese, or, by metonymy, of all the populations of the Chinese cultural sphere. It includes the syncretism of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, Wuism, as well as many new religious movements such as Chen Tao, Falun Gong and Yiguandao.

- Other folk and new religions of East Asia and Southeast Asia such as Korean shamanism, Chondogyo, and Jeung San Do in Korea; indigenous Philippine folk religions in the Philippines; Shinto, Shugendo, Ryukyuan religion, and Japanese new religions in Japan; Satsana Phi in Laos; Vietnamese folk religion, and Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo in Vietnam.

Indian religions

Indian religions are practiced or were founded in the Indian subcontinent. They are sometimes classified as the dharmic religions, as they all feature dharma, the specific law of reality and duties expected according to the religion.[144]

Hinduism

- Hinduism is also called Vaidika Dharma, the dharma of the Vedas.[145] It is a synecdoche describing the similar philosophies of Vaishnavism, Shaivism, and related groups practiced or founded in the Indian subcontinent. Concepts most of them share in common include karma, caste, reincarnation, mantras, yantras, and darśana.[note 2] Hinduism is one of the most ancient of still-active religious belief systems,[146][147] with origins perhaps as far back as prehistoric times.[148]

Jainism

- Jainism, taught primarily by Rishabhanatha (the founder of ahimsa) is an ancient Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence, truth and anekantavada for all forms of living beings in this universe; which helps them to eliminate all the Karmas, and hence to attain freedom from the cycle of birth and death (saṃsāra), that is, achieving nirvana. Jains are found mostly in India. According to Dundas, outside of the Jain tradition, historians date the Mahavira as about contemporaneous with the Buddha in the 5th-century BCE, and accordingly the historical Parshvanatha, based on the c. 250-year gap, is placed in 8th or 7th century BCE.[150]

- Digambara Jainism (or sky-clad) is mainly practiced in South India. Their holy books are Pravachanasara and Samayasara written by their Prophets Kundakunda and Amritchandra as their original canon is lost.

- Shwetambara Jainism (or white-clad) is mainly practiced in Western India. Their holy books are Jain Agamas, written by their Prophet Sthulibhadra.

Buddhism

- Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama in the 5th century BCE. Buddhists generally agree that Gotama aimed to help sentient beings end their suffering (dukkha) by understanding the true nature of phenomena, thereby escaping the cycle of suffering and rebirth (saṃsāra), that is, achieving nirvana.

- Theravada Buddhism, which is practiced mainly in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia alongside folk religion, shares some characteristics of Indian religions. It is based in a large collection of texts called the Pali Canon.

- Mahayana Buddhism (or the Great Vehicle) under which are a multitude of doctrines that became prominent in China and are still relevant in Vietnam, Korea, Japan and to a lesser extent in Europe and the United States. Mahayana Buddhism includes such disparate teachings as Zen, Pure Land, and Soka Gakkai.

- Vajrayana Buddhism first appeared in India in the 3rd century CE.[151] It is currently most prominent in the Himalaya regions[152] and extends across all of Asia[153] (cf. Mikkyō).

- Two notable new Buddhist sects are Hòa Hảo and the Navayana (Dalit Buddhist movement), which were developed separately in the 20th century.

Sikhism

- Sikhism is a panentheistic religion founded on the teachings of Guru Nanak and ten successive Sikh gurus in 15th-century Punjab. It is the fifth-largest organized religion in the world, with approximately 30 million Sikhs.[154][155] Sikhs are expected to embody the qualities of a Sant-Sipāhī—a saint-soldier, have control over one’s internal vices and be able to be constantly immersed in virtues clarified in the Guru Granth Sahib. The principal beliefs of Sikhi are faith in Waheguru—represented by the phrase ik ōaṅkār, meaning one God, who prevails in everything, along with a praxis in which the Sikh is enjoined to engage in social reform through the pursuit of justice for all human beings.

Indigenous and folk

Chickasaw Native cultural/religious dancing

Peyotists with their ceremonial tools

Indigenous religions or folk religions refers to a broad category of traditional religions that can be characterised by shamanism, animism and ancestor worship, where traditional means «indigenous, that which is aboriginal or foundational, handed down from generation to generation…».[156] These are religions that are closely associated with a particular group of people, ethnicity or tribe; they often have no formal creeds or sacred texts.[157] Some faiths are syncretic, fusing diverse religious beliefs and practices.[158]

- Australian Aboriginal religions.

- Folk religions of the Americas: Native American religions

Folk religions are often omitted as a category in surveys even in countries where they are widely practiced, e.g. in China.[157]

Traditional African

African traditional religion encompasses the traditional religious beliefs of people in Africa. In West Africa, these religions include the Akan religion, Dahomey (Fon) mythology, Efik mythology, Odinani, Serer religion (A ƭat Roog), and Yoruba religion, while Bushongo mythology, Mbuti (Pygmy) mythology, Lugbara mythology, Dinka religion, and Lotuko mythology come from central Africa. Southern African traditions include Akamba mythology, Masai mythology, Malagasy mythology, San religion, Lozi mythology, Tumbuka mythology, and Zulu mythology. Bantu mythology is found throughout central, southeast, and southern Africa. In north Africa, these traditions include Berber and ancient Egyptian.

There are also notable African diasporic religions practiced in the Americas, such as Santeria, Candomble, Vodun, Lucumi, Umbanda, and Macumba.

Iranian

Iranian religions are ancient religions whose roots predate the Islamization of Greater Iran. Nowadays these religions are practiced only by minorities.

Zoroastrianism is based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster in the 6th century BCE. Zoroastrians worship the creator Ahura Mazda. In Zoroastrianism, good and evil have distinct sources, with evil trying to destroy the creation of Mazda, and good trying to sustain it.

Kurdish religions include the traditional beliefs of the Yazidi,[159][160] Alevi, and Ahl-e Haqq. Sometimes these are labeled Yazdânism.

New religious movements

- The Baháʼí Faith teaches the unity of all religious philosophies.[135]

- Cao Đài is a syncretistic, monotheistic religion, established in Vietnam in 1926.[161]

- Eckankar is a pantheistic religion with the purpose of making God an everyday reality in one’s life.[162]

- Epicureanism is a Hellenistic philosophy that is considered by many of its practitioners as a type of (sometimes non-theistic) religious identity. It has its own scriptures, a monthly «feast of reason» on the Twentieth, and considers friendship to be holy.

- Hindu reform movements, such as Ayyavazhi, Swaminarayan Faith and Ananda Marga, are examples of new religious movements within Indian religions.

- Japanese new religions (shinshukyo) is a general category for a wide variety of religious movements founded in Japan since the 19th century. These movements share almost nothing in common except the place of their founding. The largest religious movements centered in Japan include Soka Gakkai, Tenrikyo, and Seicho-No-Ie among hundreds of smaller groups.[163]

- Jehovah’s Witnesses, a non-trinitarian Christian Reformist movement sometimes described as millenarian.[164]

- Neo-Druidism is a religion promoting harmony with nature,[165] named after but not necessarily connected to the Iron Age druids.[166]

- Modern pagan movements attempting to reconstruct or revive ancient pagan practices, such as Heathenry, Hellenism, and Kemeticism[167]

- Noahidism is a monotheistic ideology based on the Seven Laws of Noah,[168] and on their traditional interpretations within Rabbinic Judaism.

- Some forms of parody religion or fiction-based religion[169] like Jediism, Pastafarianism, Dudeism, «Tolkien religion»,[169] and others often develop their own writings, traditions, and cultural expressions, and end up behaving like traditional religions.

- Satanism is a broad category of religions that, for example, worship Satan as a deity (Theistic Satanism) or use Satan as a symbol of carnality and earthly values (LaVeyan Satanism and The Satanic Temple).[170]

- Scientology[171] is a religious movement that teaches that people are immortal beings who have forgotten their true nature. Its method of spiritual rehabilitation is a type of counseling known as auditing, in which practitioners aim to consciously re-experience and understand painful or traumatic events and decisions in their past in order to free themselves of their limiting effects.

- UFO Religions in which extraterrestrial entities are an element of belief, such as Raëlism, Aetherius Society, and Marshall Vian Summers’s New Message from God

- Unitarian Universalism is a religion characterized by support for a free and responsible search for truth and meaning, and has no accepted creed or theology.[172]

- Wicca is a neo-pagan religion first popularised in 1954 by British civil servant Gerald Gardner, involving the worship of a God and Goddess.[173]

Law

The study of law and religion is a relatively new field, with several thousand scholars involved in law schools, and academic departments including political science, religion, and history since 1980.[174] Scholars in the field are not only focused on strictly legal issues about religious freedom or non-establishment, but also study religions as they are qualified through judicial discourses or legal understanding of religious phenomena. Exponents look at canon law, natural law, and state law, often in a comparative perspective.[175][176] Specialists have explored themes in Western history regarding Christianity and justice and mercy, rule and equity, and discipline and love.[177] Common topics of interest include marriage and the family[178] and human rights.[179] Outside of Christianity, scholars have looked at law and religion links in the Muslim Middle East[180] and pagan Rome.[181]

Studies have focused on secularization.[182][183] In particular, the issue of wearing religious symbols in public, such as headscarves that are banned in French schools, have received scholarly attention in the context of human rights and feminism.[184]

Science

Science acknowledges reason and empirical evidence; and religions include revelation, faith and sacredness whilst also acknowledging philosophical and metaphysical explanations with regard to the study of the universe. Both science and religion are not monolithic, timeless, or static because both are complex social and cultural endeavors that have changed through time across languages and cultures.[185]

The concepts of science and religion are a recent invention: the term religion emerged in the 17th century in the midst of colonization and globalization and the Protestant Reformation.[3][21] The term science emerged in the 19th century out of natural philosophy in the midst of attempts to narrowly define those who studied nature (natural science),[21][186][187] and the phrase religion and science emerged in the 19th century due to the reification of both concepts.[21] It was in the 19th century that the terms Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, and Confucianism first emerged.[21] In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin roots of both science (scientia) and religion (religio) were understood as inner qualities of the individual or virtues, never as doctrines, practices, or actual sources of knowledge.[21]

In general the scientific method gains knowledge by testing hypotheses to develop theories through elucidation of facts or evaluation by experiments and thus only answers cosmological questions about the universe that can be observed and measured. It develops theories of the world which best fit physically observed evidence. All scientific knowledge is subject to later refinement, or even rejection, in the face of additional evidence. Scientific theories that have an overwhelming preponderance of favorable evidence are often treated as de facto verities in general parlance, such as the theories of general relativity and natural selection to explain respectively the mechanisms of gravity and evolution.

Religion does not have a method per se partly because religions emerge through time from diverse cultures and it is an attempt to find meaning in the world, and to explain humanity’s place in it and relationship to it and to any posited entities. In terms of Christian theology and ultimate truths, people rely on reason, experience, scripture, and tradition to test and gauge what they experience and what they should believe. Furthermore, religious models, understanding, and metaphors are also revisable, as are scientific models.[188]

Regarding religion and science, Albert Einstein states (1940): «For science can only ascertain what is, but not what should be, and outside of its domain value judgments of all kinds remain necessary.[189] Religion, on the other hand, deals only with evaluations of human thought and action; it cannot justifiably speak of facts and relationships between facts[189]…Now, even though the realms of religion and science in themselves are clearly marked off from each other, nevertheless there exist between the two strong reciprocal relationships and dependencies. Though religion may be that which determine the goals, it has, nevertheless, learned from science, in the broadest sense, what means will contribute to the attainment of the goals it has set up.»[190]

Morality

Many religions have value frameworks regarding personal behavior meant to guide adherents in determining between right and wrong. These include the Triple Jems of Jainism, Judaism’s Halacha, Islam’s Sharia, Catholicism’s Canon Law, Buddhism’s Eightfold Path, and Zoroastrianism’s good thoughts, good words, and good deeds concept, among others.[191]

Religion and morality are not synonymous. While it is «an almost automatic assumption,»[192] in Christianity, morality can have a secular basis.

The study of religion and morality can be contentious due to ethnocentric views on morality, failure to distinguish between in group and out group altruism, and inconsistent definitions of religiosity.

Politics

Impact

Religion has had a significant impact on the political system in many countries.[193] Notably, most Muslim-majority countries adopt various aspects of sharia, the Islamic law.[194] Some countries even define themselves in religious terms, such as The Islamic Republic of Iran. The sharia thus affects up to 23% of the global population, or 1.57 billion people who are Muslims. However, religion also affects political decisions in many western countries. For instance, in the United States, 51% of voters would be less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who did not believe in God, and only 6% more likely.[195] Christians make up 92% of members of the US Congress, compared with 71% of the general public (as of 2014). At the same time, while 23% of U.S. adults are religiously unaffiliated, only one member of Congress (Kyrsten Sinema, D-Arizona), or 0.2% of that body, claims no religious affiliation.[196] In most European countries, however, religion has a much smaller influence on politics[197] although it used to be much more important. For instance, same-sex marriage and abortion were illegal in many European countries until recently, following Christian (usually Catholic) doctrine. Several European leaders are atheists (e.g. France’s former president Francois Hollande or Greece’s prime minister Alexis Tsipras). In Asia, the role of religion differs widely between countries. For instance, India is still one of the most religious countries and religion still has a strong impact on politics, given that Hindu nationalists have been targeting minorities like the Muslims and the Christians, who historically[when?] belonged to the lower castes.[198] By contrast, countries such as China or Japan are largely secular and thus religion has a much smaller impact on politics.

Secularism

Secularization is the transformation of the politics of a society from close identification with a particular religion’s values and institutions toward nonreligious values and secular institutions. The purpose of this is frequently modernization or protection of the populations religious diversity.

Economics

Average income correlates negatively with (self-defined) religiosity.[116]

One study has found there is a negative correlation between self-defined religiosity and the wealth of nations.[199] In other words, the richer a nation is, the less likely its inhabitants to call themselves religious, whatever this word means to them (Many people identify themselves as part of a religion (not irreligion) but do not self-identify as religious).[199]

Sociologist and political economist Max Weber has argued that Protestant Christian countries are wealthier because of their Protestant work ethic.[200] According to a study from 2015, Christians hold the largest amount of wealth (55% of the total world wealth), followed by Muslims (5.8%), Hindus (3.3%) and Jews (1.1%). According to the same study it was found that adherents under the classification Irreligion or other religions hold about 34.8% of the total global wealth (while making up only about 20% of the world population, see section on classification).[201]

Health

Mayo Clinic researchers examined the association between religious involvement and spirituality, and physical health, mental health, health-related quality of life, and other health outcomes.[202] The authors reported that: «Most studies have shown that religious involvement and spirituality are associated with better health outcomes, including greater longevity, coping skills, and health-related quality of life (even during terminal illness) and less anxiety, depression, and suicide.»[203]

The authors of a subsequent study concluded that the influence of religion on health is largely beneficial, based on a review of related literature.[204] According to academic James W. Jones, several studies have discovered «positive correlations between religious belief and practice and mental and physical health and longevity.»[205]

An analysis of data from the 1998 US General Social Survey, whilst broadly confirming that religious activity was associated with better health and well-being, also suggested that the role of different dimensions of spirituality/religiosity in health is rather more complicated. The results suggested «that it may not be appropriate to generalize findings about the relationship between spirituality/religiosity and health from one form of spirituality/religiosity to another, across denominations, or to assume effects are uniform for men and women.[206]

Violence

Critics like Hector Avalos[207] Regina Schwartz,[208] Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins have argued that religions are inherently violent and harmful to society by using violence to promote their goals, in ways that are endorsed and exploited by their leaders.[209][page needed][210][page needed]

Anthropologist Jack David Eller asserts that religion is not inherently violent, arguing «religion and violence are clearly compatible, but they are not identical.» He asserts that «violence is neither essential to nor exclusive to religion» and that «virtually every form of religious violence has its nonreligious corollary.»[211][212]

Animal sacrifice

Some (but not all) religions practise animal sacrifice, the ritual killing and offering of an animal to appease or maintain favour with a deity. It has been banned in India.[213]

Superstition

Greek and Roman pagans, who saw their relations with the gods in political and social terms, scorned the man who constantly trembled with fear at the thought of the gods (deisidaimonia), as a slave might fear a cruel and capricious master. The Romans called such fear of the gods superstitio.[214] Ancient Greek historian Polybius described superstition in ancient Rome as an instrumentum regni, an instrument of maintaining the cohesion of the Empire.[215]

Superstition has been described as the non-rational establishment of cause and effect.[216] Religion is more complex and is often composed of social institutions and has a moral aspect. Some religions may include superstitions or make use of magical thinking. Adherents of one religion sometimes think of other religions as superstition.[217][218] Some atheists, deists, and skeptics regard religious belief as superstition.

The Roman Catholic Church considers superstition to be sinful in the sense that it denotes a lack of trust in the divine providence of God and, as such, is a violation of the first of the Ten Commandments. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that superstition «in some sense represents a perverse excess of religion» (para. #2110). «Superstition,» it says, «is a deviation of religious feeling and of the practices this feeling imposes. It can even affect the worship we offer the true God, e.g., when one attributes an importance in some way magical to certain practices otherwise lawful or necessary. To attribute the efficacy of prayers or of sacramental signs to their mere external performance, apart from the interior dispositions that they demand is to fall into superstition. Cf. Matthew 23:16–22» (para. #2111)

Agnosticism and atheism

The terms atheist (lack of belief in any gods) and agnostic (belief in the unknowability of the existence of gods), though specifically contrary to theistic (e.g. Christian, Jewish, and Muslim) religious teachings, do not by definition mean the opposite of religious. There are religions (including Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism), in fact, that classify some of their followers as agnostic, atheistic, or nontheistic. The true opposite of religious is the word irreligious. Irreligion describes an absence of any religion; antireligion describes an active opposition or aversion toward religions in general.

Interfaith cooperation

Because religion continues to be recognized in Western thought as a universal impulse,[219] many religious practitioners[who?][220] have aimed to band together in interfaith dialogue, cooperation, and religious peacebuilding. The first major dialogue was the Parliament of the World’s Religions at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, which affirmed universal values and recognition of the diversity of practices among different cultures.[221] The 20th century has been especially fruitful in use of interfaith dialogue as a means of solving ethnic, political, or even religious conflict, with Christian–Jewish reconciliation representing a complete reverse in the attitudes of many Christian communities towards Jews.[222]

Recent interfaith initiatives include A Common Word, launched in 2007 and focused on bringing Muslim and Christian leaders together,[223] the «C1 World Dialogue»,[224] the Common Ground initiative between Islam and Buddhism,[225] and a United Nations sponsored «World Interfaith Harmony Week».[226][227]

Culture

Culture and religion have usually been seen as closely related.[42] Paul Tillich looked at religion as the soul of culture and culture as the form or framework of religion.[228] In his own words:

Religion as ultimate concern is the meaning-giving substance of culture, and culture is the totality of forms in which the basic concern of religion expresses itself. In abbreviation: religion is the substance of culture, culture is the form of religion. Such a consideration definitely prevents the establishment of a dualism of religion and culture. Every religious act, not only in organized religion, but also in the most intimate movement of the soul, is culturally formed.[229]

Ernst Troeltsch, similarly, looked at culture as the soil of religion and thought that, therefore, transplanting a religion from its original culture to a foreign culture would actually kill it in the same manner that transplanting a plant from its natural soil to an alien soil would kill it.[230] However, there have been many attempts in the modern pluralistic situation to distinguish culture from religion.[231] Domenic Marbaniang has argued that elements grounded on beliefs of a metaphysical nature (religious) are distinct from elements grounded on nature and the natural (cultural). For instance, language (with its grammar) is a cultural element while sacralization of language in which a particular religious scripture is written is more often a religious practice. The same applies to music and the arts.[232]

Criticism

Criticism of religion is criticism of the ideas, the truth, or the practice of religion, including its political and social implications.[233]

See also

- Cosmogony

- Index of religion-related articles

- Life stance

- List of foods with religious symbolism

- List of religion-related awards

- List of religious texts

- Matriarchal religion

- Nontheistic religions

- Outline of religion

- Parody religions

- Ethics in religion

- Philosophy of religion

- Priest

- Religion and happiness

- Religion and peacebuilding

- Religions by country

- Religious conversion

- Religious discrimination

- Social conditioning

- Socialization

- Temple

- Theocracy

- Theology of religions

- Timeline of religion

- Why is there something rather than nothing?

- The State Museum of the History of Religion

Notes

- ^ That is how, according to Durkheim, Buddhism is a religion. «In default of gods, Buddhism admits the existence of sacred things, namely, the four noble truths and the practices derived from them» Durkheim 1915

- ^ Hinduism is variously defined as a religion, set of religious beliefs and practices, religious tradition etc. For a discussion on the topic, see: «Establishing the boundaries» in Gavin Flood (2003), pp. 1–17. René Guénon in his Introduction to the Study of the Hindu doctrines (1921 ed.), Sophia Perennis, ISBN 0-900588-74-8, proposes a definition of the term religion and a discussion of its relevance (or lack of) to Hindu doctrines (part II, chapter 4, p. 58).

References

- ^ «Religion – Definition of Religion by Merriam-Webster». Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). «Myth 1: All Societies Have Religions». 50 Great Myths of Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-0-470-67350-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15416-0.

- ^ a b James 1902, p. 31.

- ^ a b Durkheim 1915.

- ^ a b Tillich, P. (1957) Dynamics of faith. Harper Perennial; (p. 1).

- ^ a b Vergote, A. (1996) Religion, Belief and Unbelief. A Psychological Study, Leuven University Press. (p. 16)

- ^ a b Swindal, James (April 2010). «Faith and Reason». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ African Studies Association; University of Michigan (2005). History in Africa. Vol. 32. p. 119.

- ^ «The Global Religious Landscape». 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «Religiously Unaffiliated». The Global Religious Landscape. Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

The religiously unaffiliated include atheists, agnostics and people who do not identify with any particular religion in surveys. However, many of the religiously unaffiliated have some religious beliefs.

- ^ Eileen Barker, 1999, «New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance», New Religious Movements: challenge and response, Bryan Wilson and Jamie Cresswell editors, Routledge ISBN 0-415-20050-4

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil (2006). «3 — Atheism: Contemporary Numbers and Patterns». In Martin, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. pp. 47–66. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521842700.004. ISBN 9781139001182.

- ^ James, Paul (2018). «What Does It Mean Ontologically to Be Religious?». In Stephen Ames; Ian Barns; John Hinkson; Paul James; Gordon Preece; Geoff Sharp (eds.). Religion in a Secular Age: The Struggle for Meaning in an Abstracted World. Arena Publications. pp. 56–100. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «religion». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ «Religion» Oxford English Dictionary https://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/161944 Archived 3 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ In The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light. Toronto. Thomas Allen, 2004. ISBN 0-88762-145-7

- ^ In The Power of Myth, with Bill Moyers, ed. Betty Sue Flowers, New York, Anchor Books, 1991. ISBN 0-385-41886-8

- ^ a b Huizinga, Johan (1924). The Waning of the Middle Ages. Penguin Books. p. 86.

- ^ «Religio». Latin Word Study Tool. Tufts University. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18448-7.

- ^ a b Roberts, Jon (2011). «10. Science and Religion». In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ^ a b c d e Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). «Myth 1: All Societies Have Religions». 50 Great Myths about Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-0-470-67350-8.

- ^ a b Barton, Carlin; Boyarin, Daniel (2016). «1. ‘Religio’ without «Religion»«. Imagine No Religion : How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient Realities. Fordham University Press. pp. 15–38. ISBN 978-0-8232-7120-7.

- ^ Reus-Smit, Christian (April 2011). «Struggles for Individual Rights and the Expansion of the International System». International Organization. 65 (2): 207–242. doi:10.1017/S0020818311000038. ISSN 1531-5088. S2CID 145668420.

- ^ Caesar, Julius (2007). «Civil Wars – Book 1». The Works of Julius Caesar: Parallel English and Latin. Translated by McDevitte, W.A.; Bohn, W.S. Forgotten Books. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-1-60506-355-3.

Sic terror oblatus a ducibus, crudelitas in supplicio, nova religio iurisiurandi spem praesentis deditionis sustulit mentesque militum convertit et rem ad pristinam belli rationem redegit.» – (Latin); «Thus the terror raised by the generals, the cruelty and punishments, the new obligation of an oath, removed all hopes of surrender for the present, changed the soldiers’ minds, and reduced matters to the former state of war.»- (English)

- ^ Pliny the Elder. «Elephants; Their Capacity». The Natural History, Book VIII. Tufts University. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

maximum est elephans proximumque humanis sensibus, quippe intellectus illis sermonis patrii et imperiorum obedientia, officiorum quae didicere memoria, amoris et gloriae voluptas, immo vero, quae etiam in homine rara, probitas, prudentia, aequitas, religio quoque siderum solisque ac lunae veneratio.» «The elephant is the largest of them all, and in intelligence approaches the nearest to man. It understands the language of its country, it obeys commands, and it remembers all the duties which it has been taught. It is sensible alike of the pleasures of love and glory, and, to a degree that is rare among men even, possesses notions of honesty, prudence, and equity; it has a religious respect also for the stars, and a veneration for the sun and the moon.»

- ^ Cicero, De natura deorum Book II, Section 8.

- ^ Barton, Carlin; Boyarin, Daniel (2016). «8. Imagine No ‘Threskeia’: The Task of the Untranslator». Imagine No Religion : How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient Realities. Fordham University Press. pp. 123–134. ISBN 978-0-8232-7120-7.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (1990). ‘Religion’ and the Religions in the English Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89293-3.

- ^ a b Dubuisson, Daniel (2007). The Western Construction of Religion: Myths, Knowledge, and Ideology. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8756-7.

- ^ a b c Fitzgerald, Timothy (2007). Discourse on Civility and Barbarity. Oxford University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-19-530009-3.

- ^ Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (1963). The Meaning and End of Religion. New York: MacMillan. pp. 125–126.

- ^ Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-300-15416-0.

Although the Greeks, Romans, Mesopotamians, and many other peoples have long histories, the stories of their respective religions are of recent pedigree. The formation of ancient religions as objects of study coincided with the formation of religion itself as a concept of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (1990). ‘Religion’ and the Religions in the English Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-89293-3.

That there exist in the world such entities as ‘the religions’ is an uncontroversial claim…However, it was not always so. The concepts ‘religion’ and ‘the religions’, as we presently understand them, emerged quite late in Western thought, during the Enlightenment. Between them, these two notions provided a new framework for classifying particular aspects of human life.

- ^ Nongbri, Brent (2013). «2. Lost in Translation: Inserting «Religion» into Ancient Texts». Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15416-0.

- ^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). 50 Great Myths about Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-470-67350-8.

Many languages do not even have a word equivalent to our word ‘religion’; nor is such a word found in either the Bible or the Qur’an.

- ^ Hershel Edelheit, Abraham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary Archived 24 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, p. 3, citing Solomon Zeitlin, The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion? (Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936).

- ^ Whiteford, Linda M.; Trotter II, Robert T. (2008). Ethics for Anthropological Research and Practice. Waveland Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4786-1059-5. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ a b Burns, Joshua Ezra (22 June 2015). «3. Jewish ideologies of Peace and Peacemaking». In Omar, Irfan; Duffey, Michael (eds.). Peacemaking and the Challenge of Violence in World Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-1-118-95342-6.

- ^ Boyarin, Daniel (2019). Judaism: The Genealogy of a Modern Notion. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-7161-4.

- ^ a b «14.1A: The Nature of Religion». Social Sci LibreTexts. 15 August 2018. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Kuroda, Toshio (1996). Translated by Jacqueline I. Stone. «The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law» (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies: 23.3–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ Neil McMullin. Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1984.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. University of Chicago Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-226-18448-7.

The first recorded use of «Boudhism» was 1801, followed by «Hindooism» (1829), «Taouism» (1838), and «Confucianism» (1862) (see figure 6). By the middle of the nineteenth century these terms had secured their place in the English lexicon, and the putative objects to which they referred became permanent features of our understanding of the world.

- ^ a b Josephson, Jason Ananda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. University of Chicago Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-226-41234-4.

The early nineteenth century saw the emergence of much of this terminology, including the formation of the terms Boudhism (1801), Hindooism (1829), Taouism (1839), Zoroastri-anism (1854), and Confucianism (1862). This construction of «religions» was not merely the production of European translation terms, but the reification of systems of thought in a way strikingly divorced from their original cultural milieu. The original discovery of religions in different cultures was rooted in the assumption that each people had its own divine «revelation,» or at least its own parallel to Christianity. In the same period, however, European and American explorers often suggested that specific African or Native American tribes lacked religion altogether. Instead these groups were reputed to have only superstitions and as such they were seen as less than human.

- ^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). 50 Great Myths about Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-470-67350-8.

The phrase «World Religions» came into use when the first Parliament of the World’s Religions was held in Chicago in 1893. Representation at the Parliament was not comprehensive. Naturally, Christians dominated the meeting, and Jews were represented. Muslims were represented by a single American Muslim. The enormously diverse traditions of India were represented by a single teacher, while three teachers represented the arguably more homogenous strains of Buddhist thought. The indigenous religions of the Americas and Africa were not represented. Nevertheless, since the convening of the Parliament, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism have been commonly identified as World Religions. They are sometimes called the «Big Seven» in Religious Studies textbooks, and many generalizations about religion have been derived from them.

- ^ Rhodes, John (January 1991). «An American Tradition: The Religious Persecution of Native Americans». Montana Law Review. 52 (1): 13–72.

In their traditional languages, Native Americans have no word for religion. This absence is very revealing.

- ^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). 50 Great Myths about Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-470-67350-8.

Before the British colonized India, for example, the people there had no concept «religion» and no concept «Hinduism.» There was no word «Hindu» in classical India, and no one spoke of «Hinduism» until the 1800s. Until the introduction of that term, Indians identified themselves by any number of criteria—family, trade or profession, or social level, and perhaps the scriptures they followed or the particular deity or deities upon whose care they relied in various contexts or to whom they were devoted. But these diverse identities were united, each an integral part of life; no part existed in a separate sphere identified as «religious.» Nor were the diverse traditions lumped together under the term «Hinduism» unified by sharing such common features of religion as a single founder, creed, theology, or institutional organization.

- ^ Pennington, Brian K. (2005), Was Hinduism Invented?: Britons, Indians, and the Colonial Construction of Religion, Oxford University Press, pp. 111–118, ISBN 978-0-19-803729-3, archived from the original on 17 December 2019, retrieved 5 August 2018

- ^ Lloyd Ridgeon (2003). Major World Religions: From Their Origins to the Present. Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-134-42935-6.

It is often said that Hinduism is very ancient, and in a sense this is true … . It was formed by adding the English suffix -ism, of Greek origin, to the word Hindu, of Persian origin; it was about the same time that the word Hindu, without the suffix -ism, came to be used mainly as a religious term. … The name Hindu was first a geographical name, not a religious one, and it originated in the languages of Iran, not of India. … They referred to the non-Muslim majority, together with their culture, as ‘Hindu’. … Since the people called Hindu differed from Muslims most notably in religion, the word came to have religious implications, and to denote a group of people who were identifiable by their Hindu religion. … However, it is a religious term that the word Hindu is now used in English, and Hinduism is the name of a religion, although, as we have seen, we should beware of any false impression of uniformity that this might give us.

- ^ Josephson, Jason Ananda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1, 11–12. ISBN 978-0-226-41234-4.

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil; Galen, Luke; Pasquale, Frank (2016). «2. Secularity around the World». The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies. Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-19-992494-3.

It was only in response to Western cultural contact in the late nineteenth century that a Japanese word for religion (shukyo) came into use. It tends to be associated with foreign, founded, or formally organized traditions, particularly Christianity and other monotheisms, but also Buddhism and new religious sects.

- ^ Max Müller, Natural Religion, p. 33, 1889

- ^ «Lewis & Short, A Latin Dictionary«. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Max Müller. Introduction to the science of religion Archived 11 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. p. 28.

- ^ Vgl. Johann Figl: Handbuch Religionswissenschaft: Religionen und ihre zentralen Themen. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, ISBN 3-7022-2508-0, S. 65.

- ^ Julia Haslinger: Die Evolution der Religionen und der Religiosität, s. Literatur Religionsgeschichte, S. 3–4, 8.

- ^ Johann Figl: Handbuch Religionswissenschaft: Religionen und ihre zentralen Themen. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, ISBN 3-7022-2508-0, S. 67.