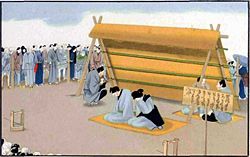

Man and woman undergoing public exposure for adultery in Japan from Sketches of Japanese Manners and Customs, by J. M. W. Silver, published in 1867

Punishment is the practice of imposing something unpleasant on a person as a response to some unwanted or immoral behavior or disobedience that they have displayed. Punishment has evolved with society; starting out as a simple system of revenge by the individual, family, or tribe, it soon grew as an institution protected by governments, into a large penal and justice system. The methods of punishment have also evolved. The harshest—the death penalty—which used to involve deliberate pain and prolonged, public suffering, involving stoning, burning at the stake, hanging, drawing and quartering, and so forth evolved into attempts to be more humane, establishing the use of the electric chair and lethal injection. In many cases, physical punishment has given way to socieconomic methods, such as fines or imprisonment.

The trend in criminal punishment has been away from revenge and retribution, to a more practical, utilitarian concern for deterrence and rehabilitation. As a deterrent, punishment serves to show people norms of what is right and wrong in society. It effectively upholds the morals, values, and ethics that are important to a particular society and attempts to dissuade people from violating those important standards of society. In this sense, the goal of punishment is to deter people from engaging in activities deemed as wrong by law and the population, and to act to reform those who do violate the law.

The rise of the protection of the punished created new social movements, and evoked prison and penitentiary reform. This has also led to more rights for the punished, as the idea of punishment as retribution or revenge has large been superseded by the functions of protecting society and reforming the perpetrator.

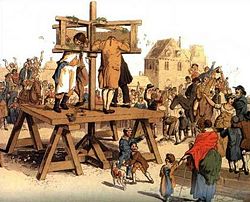

William Pyne: The Costume of Great Britain (1805) — The Pillory

Definitions

Punishment may be defined as «an authorized imposition of deprivations — of freedom or privacy or other goods to which the person otherwise has a right, or the imposition of special burdens — because the person has been found guilty of some criminal violation, typically (though not invariably) involving harm to the innocent.»[1] Thus, punishment may involve removal of something valued or the infliction of something unpleasant or painful on the person being punished. This definition purposely separates the act of punishment from its justification and purpose.

The word «punishment» is the abstract substantiation of the verb to punish, which is recorded in English since 1340, deriving from Old French puniss-, an extended form of the stem of punir «to punish,» from Latin punire «inflict a penalty on, cause pain for some offense,» earlier poenire, from poena «penalty, punishment.»[2]

The most common applications are in legal and similarly regulated contexts, being the infliction of some kind of pain or loss upon a person for a misdeed, namely for transgressing a law or command (including prohibitions) given by some authority (such as an educator, employer, or supervisor, public or private official). Punishment of children by parents in the home as a disciplinary measure is also a common application.

In terms of socialization, punishment is seen in the context of broken laws and taboos. Sociologists such as Emile Durkheim have suggested that without punishment, society would devolve into a state of lawlessness, anomie. The very function of the penal system is to inspire law-abiding citizens, not lawlessness. In this way, punishment reinforces the standards of acceptable behavior for socialized people.[3]

History

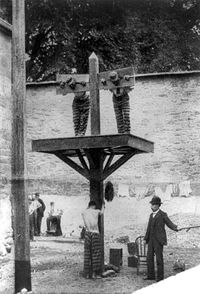

Two prisoners in pillory with another tied to whipping post below and man with whip in prison in Delaware

The progress of civilization has resulted in a vast change in both the theory and in the method of punishment. In primitive society punishment was left to the individuals wronged, or their families, and was vindictive or retributive: in quantity and quality it would bear no special relation to the character or gravity of the offense. Gradually there arose the idea of proportionate punishment, of which the characteristic type is the lex talionis—»an eye for an eye.»

The second stage was punishment by individuals under the control of the state, or community. In the third stage, with the growth of law, the state took over the punitive function and provided itself with the machinery of justice for the maintenance of public order.[4] Henceforward crimes were against the state, and the exaction of punishment by the wronged individual (such as lynching) became illegal. Even at this stage the vindictive or retributive character of punishment remained, but gradually, and especially after the humanist thinkers Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, new theories begin to emerge.

Two chief trains of thought have combined in the condemnation of primitive theory and practice. On the one hand the retributive principle itself has been very largely superseded by the protective and the reformative approach. On the other, punishments involving bodily pain have become objectionable to the general sensibility of society. Consequently, corporal and capital punishment occupy a far less prominent position in societies. It began to be recognized also that stereotyped punishments, such as ones that belong to penal codes, fail to take due account of the particular condition of an offense and the character and circumstances of the offender. A fixed fine, for example, operates very unequally on rich and poor.

Modern theories date from the eighteenth century, when the humanitarian movement began to teach the dignity of the individual and to emphasize rationality and responsibility. The result was the reduction of punishment both in quantity and in severity, the improvement of the prison system, and the first attempts to study the psychology of crime and to distinguish between classes of criminals with a view to their improvement.[5]

These latter problems are the province of criminal anthropology and criminal sociology, sciences so called because they view crime as the outcome of anthropological or social conditions. The law breaker is himself a product of social evolution and cannot be regarded as solely responsible for his disposition to transgress. Habitual crime is thus to be treated as a disease. Punishment, therefore, cab be justified only in so far as it either protects society by removing temporarily or permanently one who has injured it or acting as a deterrent, or when it aims at the moral regeneration of the criminal. Thus the retributive theory of punishment with its criterion of justice as an end in itself gave place to a theory which regards punishment solely as a means to an end, utilitarian or moral, depending on whether the common advantage or the good of the criminal is sought.[6]

Types of punishments

A leather cat o’ nine tails

There are different types of punishments for different crimes. Age also plays a determinant on the type of punishment that will be used. For many instances, punishment is dependent upon context.

Criminal punishment

Convicted criminals are punished according to the judgment of the court. Penalties may be physical or socieconomic in nature.

Physical punishment is usually an action that hurts a person’s physical body; it can include whipping or caning, marking or branding, mutilation, capital punishment, imprisonment, deprivation of physical drives, and public humiliation.

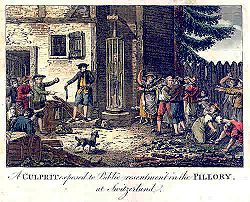

A culprit exposed to public resentment in the pillory at Switzerland by Thomas Bankes (ca. 1788-1790)

Socioeconomic punishment affects a person economically, occupationally, or financially, but not physically. It includes fines, confiscation, demotion, suspension, or expulsion, loss of civic rights, and required hours of community service. Socioeconomic punishment relies on the assumption that the person’s integration into society is valued; as someone who is well-socialized will be severely penalized and socially embarrassed by this particular action.

Especially if a precise punishment is imposed by regulations or specified in a formal sentence, often one or more official witnesses are prescribed, or somehow specified (such as from the faculty in a school or military officers) to see to the correct execution. A party grieved by the punished may be allowed the satisfaction of witnessing the humbled state of exposure and agony. The presence of peers, such as classmates, or an even more public venue such as a pillory on a square—in modern times even press coverage—may serve two purposes: increasing the humiliation of the punished and serving as an example to the audience.

Punishment for children

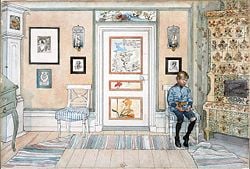

In the Punishment Corner by Carl Larsson (1853-1919)

Children’s punishments usually differ from punishments for adults. This is mainly because children are young and immature; therefore have not had the experiences that adults have had, and are thought to be less-knowledgeable about legal issues and law. Children who commit crimes are, therefore, sent to juvenile detention centers rather than adult prisons.

Punishments can be imposed by educators, which include expulsion from school, suspension from the school, detention after school for additional study, or loss of certain school privileges or freedoms. Corporal punishment, while common in most cultures in the past, has become unacceptable in many modern societies. Parents may punish a child through different ways, including spankings, custodial sentences (such as chores), a «time-out» which restricts a child from doing what he or she wants to do, grounding, and removal of privileges or choices. In parenting, additional factors that increase the effectiveness of punishment include a verbal explanation of the reason for the punishment and a good relationship between the parent and the child.[7]

Reasons

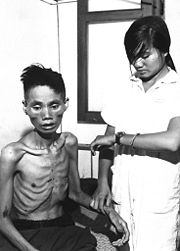

Defector from the Viet Cong who was sent to a prison camp and deliberately starved.

There are many possible reasons that might be given to justify or explain why someone ought to be punished; here follows a broad outline of typical, possibly contradictory justifications.

Deterrence

Deterrence means dissuading someone from future wrongdoing, by making the punishment severe enough that the benefit gained from the offense is outweighed by the cost (and probability) of the punishment.

Deterrence is a common reason given for why someone should be punished. It is believed that punishment, especially when made known to—or witnessed by—the punished person’s peers, can deter them from committing similar offenses, and thus serves a greater preventative good. However, it may be argued that using punishment as a deterrent has the fundamental flaw that human nature tends to ignore the possibility of punishment until they are caught, and actually can be attracted even more to the ‘forbidden fruit’, or even for various reasons glorify the punished, such as admiring a fellow for ‘taking it like a man’. Furthermore, especially with children, feelings of bitterness and resentment can be aroused towards the punisher (parent) who threaten a child with punishment.

Punishment may also be used as part of the treatment for individuals with certain mental or developmental disorders, such as autism, to deter or at least reduce the occurrence of behaviors that can be injurious (such as head banging or self-mutilation), dangerous (such as biting others), or socially stigmatizing (such as stereotypical repetition of phrases or noises). In this case, each time the undesired behavior occurs, punishment is applied to reduce future instances. Generally the use of punishment in these situations is considered ethically acceptable if the corrected behavior is a significant threat to the individual and/or to others.

Education

Punishment demonstrates to the population which social norms are acceptable and which is not. People learn, through watching, reading about, and listening to different situations where people have broken the law and received a punishment, what they are able to do in society. Punishment teaches people what rights they have in their society and what behaviors are acceptable, and which actions will bring them punishment. This kind of education is important for socialization, as it helps people become functional members of the society in which they reside.

Honoring values

Punishment can be seen to honor the values codified in law. In this view, the value of human life is seen to be honored by the punishment of a murderer. Proponents of capital punishment have been known to base their position on this concept. Retributive justice is, in this view, a moral mandate that societies must guarantee and act upon. If wrongdoing goes unpunished, individual citizens may become demoralized, ultimately undermining the moral fabric of the society.

Incapacitation

Imprisonment has the effect of confining prisoners, physically preventing them from committing crimes against those outside, thus protecting the community. The most dangerous criminals may be sentenced to life imprisonment, or even to irreparable alternatives — the death penalty, or castration of sexual offenders — for this reason of the common good.

Rehabilitation

Punishment may be designed to reform and rehabilitate the wrongdoer so that they will not commit the offense again. This is distinguished from deterrence, in that the goal here is to change the offender’s attitude to what they have done, and make them come to accept that their behavior was wrong.

Restoration

For minor offenses, punishment may take the form of the offender «righting the wrong.» For example, a vandal might be made to clean up the mess he made. In more serious cases, punishment in the form of fines and compensation payments may also be considered a sort of «restoration.» Some libertarians argue that full restoration or restitution on an individualistic basis is all that is ever just, and that this is compatible with both retributive justice and a utilitarian degree of deterrence.[8]

Revenge and retribution

Retribution is the practice of «getting even» with a wrongdoer — the suffering of the wrongdoer is seen as good in itself, even if it has no other benefits. One reason for societies to include this judicial element is to diminish the perceived need for street justice, blood revenge and vigilantism. However, some argue that this does not remove such acts of street justice and blood revenge from society, but that the responsibility for carrying them out is merely transferred to the state.

Retribution sets an important standard on punishment — the transgressor must get what he deserves, but no more. Therefore, a thief put to death is not retribution; a murderer put to death is. An important reason for punishment is not only deterrence, but also satisfying the unresolved resentment of victims and their families. One great difficulty of this approach is that of judging exactly what it is that the transgressor «deserves.» For instance, it may be retribution to put a thief to death if he steals a family’s only means of livelihood; conversely, mitigating circumstances may lead to the conclusion that the execution of a murderer is not retribution.

A specific way to elaborate this concept in the very punishment is the mirror punishment (the more literal applications of «an eye for an eye»), a penal form of ‘poetic justice’ which reflects the nature or means of the crime in the means of (mainly corporal) punishment.[9]

Religious views on punishment

Punishment may be applied on moral, especially religious, grounds as in penance (which is voluntary) or imposed in a theocracy with a religious police (as in a strict Islamic state like Iran or under the Taliban). In a theistic tradition, a government issuing punishments is working with God to uphold religious law. Punishment is also meant to allow the criminal to forgive himself/herself. When people are able to forgive themselves for a crime, God can forgive them as well. In religions that include karma in justice, such as those in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, punishment is seen as a balance to the evil committed, and to define good and evil for the people to follow. When evil is punished, it inspires people to be good, and reduces the amount of evil karma for future generations.[10]

Many religions have teachings and philosophies dealing with punishment. In Confucianism it is stated that «Heaven, in its wish to regulate the people, allows us for a day to make use of punishments» (Book of History 5.27.4, Marquis of Lu on Punishments). Hinduism regards punishment as an essential part of government of the people: «Punishment alone governs all created beings, punishment alone protects them, punishment watches over them while they sleep; the wise declare punishment to be the law. If punishment is properly inflicted after due consideration, it makes all people happy; but inflicted without consideration, it destroys everything» (Laws of Manu 7.18-20) and «A thief shall, running, approach the king, with flying hair, confessing that theft, saying, ‘Thus I have done, punish me.’ Whether he is punished or pardoned [after confessing], the thief is freed from the guilt of theft; but the king, if he punishes not, takes upon himself the guilt of the thief» (Laws of Manu 8.314, 316).

The guidelines for the Abrahamic religions come mainly from the Ten Commandments and the detailed descriptions in the Old Testament of penalties to be exacted for those violating rules. It is also noted that «He who renders true judgments is a co-worker with God» (Exodus 18.13).

However, Judaism handles punishment and misdeeds differently from other religions. If a wrongdoer commits a misdeed and apologizes to the person he or she offended, that person is required to forgive him or her. Similarly, God may forgive following apology for wrongdoing. Thus, Yom Kippur is the Jewish Day of Atonement, on which those of the Jewish faith abstain from eating or drinking to ask for God’s forgiveness for their transgressions of the previous year.

Christianity warns that people face punishment in the afterlife if they do not live in the way that Jesus, who sacrificed his life in payment for our sins, taught is the proper way of life. Earthly punishment, however, is still considered necessary to maintain order within society and to rehabilitate those who stray. The repentant criminal, by willingly accepting his punishment, is forgiven by God and inherits future blessings.

Islam takes a similar view, in that performing misdeeds will result in punishment in the afterlife. It is noted, however, that «Every person who is tempted to go astray does not deserve punishment» (Nahjul Balagha, Saying 14).

Future of Punishment

In the past, punishment was an action solely between the offender and the victim, but now a host of laws protecting both the victim and offender are involved. The justice system, including a judge, jury, lawyers, medical staff, professional experts called to testify, and witnesses all play a role in the imposition of punishments.

With increasing prison reform, concern for the rights of prisoners, and the shift from physical force against offenders, punishment has changed and continues to change. Punishments once deemed humane are no longer acceptable, and advances in psychiatry have led to many criminal offenders being termed as mentally ill, and therefore not in control of their actions. This raise the issue of responsible some criminals are for their own actions and whether they are fit to be punished.[11]

Notes

- ↑ Adam Bedau, 2005. «Punishment» Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ «punish» Online Etymology Dictionary Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ Emile Durkheim (1895) On the Normality of Crime.

- ↑ Otto Kircheimer, and George Rusche. 2003. Punishment and Social Structure. (Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0765809216)

- ↑ Markus Dubber, The Right to be Punished: Autonomy and Its Demise in Modern Penal Thought. Law and History Review. (University of Illinois, 1998). Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ David Garland. Punishment and Modern Society. (University of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0226283821)

- ↑ W. Huitt, and J. Hummel. 1997. An Introduction to Operant (Instrumental) Conditioning. Valdosta State University Press. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ C. J. Lester, 2005. A Plague on Both Your Statist Houses: Why Libertarian Restitution Beats State Retribution and State Leniency Libertarian Alliance 2005. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ H. J. McCloskey. 1962. The Complexity of the Concepts of Punishment Philosophy. University of Melbourne. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ World Scriptures.www.euro-tongil.org. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ↑ Issac Ehrlich, 1996. Crime, Punishment, and the Market for Offenses Journal of Economic Perspectives. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Garland, David. 1993. Punishment and Modern Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226283821.

- Gottschalk, Marie. 2006. The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521682916.

- Kircheimer, Otto, and George Rusche. 2003. Punishment and Social Structure. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0765809216.

- Lyons, Lewis. 2003. The History of Punishment. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1592280285.

- Western, Bruce. 2006. Punishment and Inequality in America. Russel Sage Foundation Publications. ISBN 978-0871548948.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved December 2, 2022.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- Legal Punishment

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Punishment history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Punishment»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Punishment, commonly, is the imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon a group or individual, meted out by an authority[1][2][3][4]—in contexts ranging from child discipline to criminal law—as a response and deterrent to a particular action or behavior that is deemed undesirable or unacceptable.[5] It is, however, possible to distinguish between various different understandings of what punishment is.[6]

The reasoning for punishment may be to condition a child to avoid self-endangerment, to impose social conformity (in particular, in the contexts of compulsory education or military discipline[7]), to defend norms, to protect against future harms (in particular, those from violent crime), and to maintain the law—and respect for rule of law—under which the social group is governed.[8][9][10][11][12] Punishment may be self-inflicted as with self-flagellation and mortification of the flesh in the religious setting, but is most often a form of social coercion.

The unpleasant imposition may include a fine,[13] penalty, or confinement, or be the removal or denial of something pleasant or desirable. The individual may be a person, or even an animal. The authority may be either a group or a single person, and punishment may be carried out formally under a system of law or informally in other kinds of social settings such as within a family.[9] Negative consequences that are not authorized or that are administered without a breach of rules are not considered to be punishment as defined here.[11] The study and practice of the punishment of crimes, particularly as it applies to imprisonment, is called penology, or, often in modern texts, corrections; in this context, the punishment process is euphemistically called «correctional process».[14] Research into punishment often includes similar research into prevention.

Justifications for punishment include retribution,[15] deterrence, rehabilitation, and incapacitation. The last could include such measures as isolation, in order to prevent the wrongdoer’s having contact with potential victims, or the removal of a hand in order to make theft more difficult.[16]

If only some of the conditions included in the definition of punishment are present, descriptions other than «punishment» may be considered more accurate. Inflicting something negative, or unpleasant, on a person or animal, without authority or not on the basis of a breach of rules is typically considered only revenge or spite rather than punishment.[11] In addition, the word «punishment» is used as a metaphor, as when a boxer experiences «punishment» during a fight. In other situations, breaking a rule may be rewarded, and so receiving such a reward naturally does not constitute punishment. Finally the condition of breaking (or breaching) the rules must be satisfied for consequences to be considered punishment.[11]

Punishments differ in their degree of severity, and may include sanctions such as reprimands, deprivations of privileges or liberty, fines, incarcerations, ostracism, the infliction of pain,[17] amputation and the death penalty.

Corporal punishment refers to punishments in which physical pain is intended to be inflicted upon the transgressor.

Punishments may be judged as fair or unfair[18] in terms of their degree of reciprocity and proportionality[10] to the offense.

Punishment can be an integral part of socialization, and punishing unwanted behavior is often part of a system of pedagogy or behavioral modification which also includes rewards.[19]

Definitions[edit]

Hester Prynne at the Stocks—an engraved illustration from an 1878 edition of The Scarlet Letter

Punishment of an offender in Hungary, 1793

There are a large number of different understandings of what punishment is.[6]

In philosophy[edit]

Various philosophers have presented definitions of punishment.[8][9][10][11][12] Conditions commonly considered necessary properly to describe an action as punishment are that

- it is imposed by an authority (single or multiple),

- it involves some loss to the supposed offender,

- it is in response to an offense and

- the human (or other animal) to whom the loss is imposed should be deemed at least somewhat responsible for the offense.

In psychology[edit]

Introduced by B.F. Skinner, punishment has a more restrictive and technical definition. Along with reinforcement it belongs under the operant conditioning category. Operant conditioning refers to learning with either punishment (often confused as negative reinforcement) or a reward that serves as a positive reinforcement of the lesson to be learned.[20] In psychology, punishment is the reduction of a behavior via application of an unpleasant stimulus («positive punishment») or removal of a pleasant stimulus («negative punishment»). Extra chores or spanking are examples of positive punishment, while removing an offending student’s recess or play privileges are examples of negative punishment. The definition requires that punishment is only determined after the fact by the reduction in behavior; if the offending behavior of the subject does not decrease, it is not considered punishment. There is some conflation of punishment and aversives, though an aversion that does not decrease behavior is not considered punishment in psychology.[21][22] Additionally, «aversive stimulus» is a label behaviorists generally apply to negative reinforcers (as in avoidance learning), rather than the punishers.

In socio-biology[edit]

Punishment is sometimes called retaliatory or moralistic aggression;[23] it has been observed in all[clarification needed] species of social animals, leading evolutionary biologists to conclude that it is an evolutionarily stable strategy, selected because it favors cooperative behavior.[24][25]

Examples against sociobiological use[edit]

One criticism of the claim of all social animals being evolutionarily hardwired for punishment comes from studies of animals, such as the octopuses near Capri, Italy that suddenly formed communal cultures from having, until then lived solitary lives. During a period of heavy fishing and tourism that encroached on their territory, they started to live in groups, learning from each other, especially hunting techniques. Small, younger octopuses could be near the fully grown octopuses without being eaten by them, even though they, like other Octopus vulgaris, were cannibals until just before the group formation.[citation needed] The authors stress that this behavior change happened too fast to be a genetic characteristic in the octopuses, and that there were certainly no mammals or other «naturally» social animals punishing octopuses for cannibalism involved. The authors also note that the octopuses adopted observational learning without any evolutionary history of specialized adaptation for it.[26][27]

There are also arguments against the notion of punishment requiring intelligence, based on studies of punishment in very small-brained animals such as insects. There is proof of honey bee workers with mutations that makes them fertile laying eggs only when other honey bees are not observing them, and that the few that are caught in the act are killed.[citation needed] This is corroborated by computer simulations proving that a few simple reactions well within mainstream views of the extremely limited intelligence of insects are sufficient to emulate the «political» behavior observed in great apes. The authors argue that this falsifies the claim that punishment evolved as a strategy to deal with individuals capable of knowing what they are doing.[28]

In the case of more complex brains, the notion of evolution selecting for specific punishment of intentionally chosen breaches of rules and/or wrongdoers capable of intentional choices (for example, punishing humans for murder while not punishing lethal viruses) is subject to criticism from coevolution issues. That punishment of individuals with certain characteristics (including but, in principle, not restricted to mental abilities) selects against those characteristics, making evolution of any mental abilities considered to be the basis for penal responsibility impossible in populations subject to such selective punishment. Certain scientists argue that this disproves the notion of humans having a biological feeling of intentional transgressions deserving to be punished.[29][30][31]

Scope of application[edit]

Punishments are applied for various purposes, most generally, to encourage and enforce proper behavior as defined by society or family. Criminals are punished judicially, by fines, corporal punishment or custodial sentences such as prison; detainees risk further punishments for breaches of internal rules.[32] Children, pupils and other trainees may be punished by their educators or instructors (mainly parents, guardians, or teachers, tutors and coaches)—see Child discipline.

Slaves, domestic and other servants are subject to punishment by their masters. Employees can still be subject to a contractual form of fine or demotion. Most hierarchical organizations, such as military and police forces, or even churches, still apply quite rigid internal discipline, even with a judicial system of their own (court martial, canonical courts).

Punishment may also be applied on moral, especially religious, grounds, as in penance (which is voluntary) or imposed in a theocracy with a religious police (as in a strict Islamic state like Iran or under the Taliban) or (though not a true theocracy) by Inquisition.

Hell as punishment[edit]

Belief that an individual’s ultimate punishment is being sent by God, the highest authority, to an existence in Hell, a place believed to exist in the after-life, typically corresponds to sins committed during their life. Sometimes these distinctions are specific, with damned souls suffering for each sin committed (see for example Plato’s myth of Er or Dante’s The Divine Comedy), but sometimes they are general, with condemned sinners relegated to one or more chamber of Hell or to a level of suffering.

History and rationale[edit]

Seriousness of a crime; Punishment that fits the crime[edit]

A principle often mentioned with respect to the degree of punishment to be meted out is that the punishment should match the crime.[33][34][35]

One standard for measurement is the degree to which a crime affects others or society. Measurements of the degree of seriousness of a crime have been developed.[36]

A felony is generally considered to be a crime of «high seriousness», while a misdemeanor is not.

Possible reasons for punishment[edit]

There are many possible reasons that might be given to justify or explain why someone ought to be punished; here follows a broad outline of typical, possibly conflicting, justifications.

Deterrence[edit]

Two reasons given to justify punishment[16] is that it is a measure to prevent people from committing an offence — deterring previous offenders from re-offending, and preventing those who may be contemplating an offence they have not committed from actually committing it. This punishment is intended to be sufficient that people would choose not to commit the crime rather than experience the punishment. The aim is to deter everyone in the community from committing offences.

Some criminologists state that the number of people convicted for crime does not decrease as a result of more severe punishment and conclude that deterrence is ineffective.[37] Other criminologists object to said conclusion, citing that while most people do not know the exact severity of punishment such as whether the sentence for murder is 40 years or life, most people still know the rough outlines such as the punishments for armed robbery or forcible rape being more severe than the punishments for driving too fast or misparking a car. These criminologists therefore argue that lack of deterring effect of increasing the sentences for already severely punished crimes say nothing about the significance of the existence of punishment as a deterring factor.[38][39]

Some criminologists argue that increasing the sentences for crimes can cause criminal investigators to give higher priority to said crimes so that a higher percentage of those committing them are convicted for them, causing statistics to give a false appearance of such crimes increasing. These criminologists argue that the use of statistics to gauge the efficiency of crime fighting methods are a danger of creating a reward hack that makes the least efficient criminal justice systems appear to be best at fighting crime, and that the appearance of deterrence being ineffective may be an example of this.[40][41][42]

Rehabilitation[edit]

Some punishment includes work to reform and rehabilitate the culprit so that they will not commit the offence again.[16] This is distinguished from deterrence, in that the goal here is to change the offender’s attitude to what they have done, and make them come to see that their behavior was wrong.

Incapacitation[edit]

Incapacitation as a justification of punishment[16] refers to the offender’s ability to commit further offences being removed. Imprisonment separates offenders from the community, for example, Australia was a dumping ground for early British criminals. This was their way of removing or reducing the offenders ability to carry out certain crimes. The death penalty does this in a permanent (and irrevocable) way. In some societies, people who stole have been punished by having their hands amputated.

Retribution[edit]

Criminal activities typically give a benefit to the offender and a loss to the victim.[43][44][45][46] Punishment has been justified as a measure of retributive justice,[16][47][48][49] in which the goal is to try to rebalance any unjust advantage gained by ensuring that the offender also suffers a loss. Sometimes viewed as a way of «getting even» with a wrongdoer—the suffering of the wrongdoer is seen as a desired goal in itself, even if it has no restorative benefits for the victim. One reason societies have administered punishments is to diminish the perceived need for retaliatory «street justice», blood feud, and vigilantism.

Restoration[edit]

Especially applied to minor offenses, punishment may take the form of the offender «righting the wrong», or making restitution to the victim. Community service or compensation orders are examples of this sort of penalty.[50] In models of restorative justice, victims take an active role in a process with their offenders who are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions, «to repair the harm they’ve done—by apologizing, returning stolen money, or community service.»[51] The restorative justice approach aims to help the offender want to avoid future offences.

Education and denunciation[edit]

Punishment can be explained by positive prevention theory to use the criminal justice system to teach people what are the social norms for what is correct, and acts as a reinforcement.

Punishment can serve as a means for society to publicly express denunciation of an action as being criminal. Besides educating people regarding what is not acceptable behavior, it serves the dual function of preventing vigilante justice by acknowledging public anger, while concurrently deterring future criminal activity by stigmatizing the offender.

This is sometimes called the «Expressive Theory» of denunciation.[52]

The pillory was a method for carrying out public denunciation.[citation needed]

Some critics of the education and denunciation model cite evolutionary problems with the notion that a feeling for punishment as a social signal system evolved if punishment was not effective. The critics argue that some individuals spending time and energy and taking risks in punishing others, and the possible loss of the punished group members, would have been selected against if punishment served no function other than signals that could evolve to work by less risky means.[53][54][page needed]

Unified theory[edit]

A unified theory of punishment brings together multiple penal purposes—such as retribution, deterrence and rehabilitation—in a single, coherent framework. Instead of punishment requiring we choose between them, unified theorists argue that they work together as part of some wider goal such as the protection of rights.[55]

Criticism[edit]

Some people think that punishment as a whole is unhelpful and even harmful to the people that it is used against.[56][57] Detractors argue that punishment is simply wrong, of the same design as «two wrongs make a right». Critics argue that punishment is simply revenge. Professor Deirdre Golash, author of The Case against Punishment: Retribution, Crime Prevention, and the Law, says:

We ought not to impose such harm on anyone unless we have a very good reason for doing so. This remark may seem trivially true, but the history of humankind is littered with examples of the deliberate infliction of harm by well-intentioned persons in the vain pursuit of ends which that harm did not further, or in the successful pursuit of questionable ends. These benefactors of humanity sacrificed their fellows to appease mythical gods and tortured them to save their souls from a mythical hell, broke and bound the feet of children to promote their eventual marriageability, beat slow schoolchildren to promote learning and respect for teachers, subjected the sick to leeches to rid them of excess blood, and put suspects to the rack and the thumbscrew in the service of truth. They schooled themselves to feel no pity—to renounce human compassion in the service of a higher end. The deliberate doing of harm in the mistaken belief that it promotes some greater good is the essence of tragedy. We would do well to ask whether the goods we seek in harming offenders are worthwhile, and whether the means we choose will indeed secure them.[58]

Golash also writes about imprisonment:

Imprisonment means, at minimum, the loss of liberty and autonomy, as well as many material comforts, personal security, and access to heterosexual relations. These deprivations, according to Gresham Sykes (who first identified them) “together dealt ‘a profound hurt’ that went to ‘the very foundations of the prisoner’s being.

But these are only the minimum harms, suffered by the least vulnerable inmates in the best-run prisons. Most prisons are run badly, and in some, conditions are more squalid than in the worst of slums. In the District of Columbia jail, for example, inmates must wash their clothes and sheets in cell toilets because the laundry machines are broken. Vermin and insects infest the building, in which air vents are clogged with decades’ accumulation of dust and grime. But even inmates in prisons where conditions are sanitary must still face the numbing boredom and emptiness of prison life—a vast desert of wasted days in which little in the way of meaningful activity is possible.[58]

Destructiveness to thinking and betterment[edit]

There are critics of punishment who argue that punishment aimed at intentional actions forces people to suppress their ability to act on intent. Advocates of this viewpoint argue that such suppression of intention causes the harmful behaviors to remain, making punishment counterproductive. These people suggest that the ability to make intentional choices should instead be treasured as a source of possibilities of betterment, citing that complex cognition would have been an evolutionarily useless waste of energy if it led to justifications of fixed actions and no change as simple inability to understand arguments would have been the most thrifty protection from being misled by them if arguments were for social manipulation, and reject condemnation of people who intentionally did bad things.[59] Punishment can be effective in stopping undesirable employee behaviors such as tardiness, absenteeism or substandard work performance. However, punishment does not necessarily cause an employee to demonstrate a desirable behavior.[60]

See also[edit]

- Capital punishment

- Capital and corporal punishment in Judaism

- List of capital crimes in the Torah

- List of methods of capital punishment

- List of people burned as heretics

- List of people executed for witchcraft

- Religion and capital punishment

- Coercion

- Corporal punishment

- Devaluation

- Discipline (BDSM)

- Hudud

- Intimidation

- Nulla poena sine lege

- Preventive state

- Suffering

- Telishment

Citations[edit]

- ^ Edwards, Jonathan (1824). «The salvation of all men strictly examined: and the endless punishment of those who die impenitent : argued and defended against the objections and reasonings of the late Rev. Doctor Chauncy, of Boston ; in his book entitled «The Salvation of all Men,» &c». C. Ewer and T. Bedlington, 1824: 157.

- ^ Bingham, Joseph (1712). «Volume 1 of A Scholastical History Of The Practice of the Church In Reference to the Administration of Baptism By Laymen». A Scholastical History of the Practice of the Church in Reference to the Administration of Baptism by Laymen. Knaplock, 1712. 1: 25.

- ^ Grotius, Hugo (1715). «H. Grotius of the Rights of War and Peace: In Three Volumes: in which are Explain’d the Laws and Claims of Nature and Nations, and the Principal Points that Relate Either to Publick Government, Or the Conduct of Private Life: Together with the Author’s Own Notes: Done Into English…, Volume 2». H. Grotius of the Rights of War and Peace: In Three Volumes: In Which Are Explain’d the Laws and Claims of Nature and Nations, and the Principal Points That Relate Either to Publick Government, or the Conduct of Private Life: Together with the Author’s Own Notes: Done into English by Several Hands: With the Addition of the Author’s Life by the Translators: Dedicated to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Hugo Grotius. D. Brown…, T. Ward…, and W. Meares, 1715. 2: 524.

- ^ Casper, Johann Ludwig (1864). «A Handbook of the practice of forensic medicine v. 3 1864». A Handbook of the Practice of Forensic Medicine. New Sydenham Society. 3: 2.

- ^ Lee Hansen, Marcus (1918). «Old Fort Snelling, 1819-1858». Mid-America Series. State Historical Society of Iowa, 1918: 124.

- ^ a b Gade, Christian B. N. (2020). «Is restorative justice punishment?». Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 38 (3): 127–155. doi:10.1002/crq.21293.

- ^ Navy Department, United States (1940). «Compilation of Court-martial Orders, 1916-1937, 1940-41». Compilation of Court-martial Orders, 1916-1937, 1940-41: 648.

- ^ a b

Hugo, Adam Bedau (February 19, 2010). «Punishment, Crime and the State». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2010-08-04.The search for a precise definition of punishment that exercised some philosophers (for discussion and references see Scheid 1980) is likely to prove futile: but we can say that legal punishment involves the imposition of something that is intended to be burdensome or painful, on a supposed offender for a supposed crime, by a person or body who claims the authority to do so.

- ^ a b c and violates the law or rules by which the group is governed.

McAnany, Patrick D. (August 2010). «Punishment». Online. Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2010-08-04.Punishment describes the imposition by some authority of a deprivation—usually painful—on a person who has violated a law, rule, or other norm. When the violation is of the criminal law of society there is a formal process of accusation and proof followed by imposition of a sentence by a designated official, usually a judge. Informally, any organized group—most typically the family, in rearing children—may punish perceived wrongdoers.

- ^ a b c

Hugo, Adam Bedau (February 19, 2010). «Theory of Punishment». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2010-08-04.Punishment under law… is the authorized imposition of deprivations—of freedom or privacy or other goods to which the person otherwise has a right, or the imposition of special burdens—because the person has been found guilty of some criminal violation, typically (though not invariably) involving harm to the innocent. (The classical formulation, conspicuous in Hobbes, for example, defines punishment by reference to imposing pain rather than to deprivations.) This definition, although imperfect because of its brevity, does allow us to bring out several essential points.

- ^ a b c d e

Peters, Richard Stanley (1966). «Ethics and Education». British Journal of Educational Studies. 20 (3): 267–68. JSTOR 3120772.Punishment… involves the intentional infliction of pain or of something unpleasant on someone who has committed a breach of rules… by someone who is in authority, who has a right to act in this way. Otherwise, it would be impossible to distinguish ‘punishment’ from ‘revenge’. People in authority can, of course, inflict pain on people at whim. But this would be called ‘spite’ unless it were inflicted as a consequence of a breach of rules on the part of the sufferer. Similarly a person in authority might give a person £5 as a consequence of his breaking a rule. But unless this were regarded as painful or at least unpleasant for the recipient it could not be counted as a case of ‘punishment’. In other words at least three criteria of (i) intentional infliction of pain (ii) by someone in authority (iii) on a person as a consequence of a breach of rules on his part, must be satisfied if we are to call something a case of ‘punishment’. There are, as is usual in such cases, examples that can be produced which do not satisfy all criteria. For instance there is a colloquialism which is used about boxers taking a lot of punishment from their opponents, in which only the first condition is present. But this is a metaphorical use which is peripheral to the central use of the term.

In so far as the different ‘theories’ of punishment are answers to questions about the meaning of ‘punishment’, only the retributive theory is a possible one. There is no conceptual connection between ‘punishment’ and notions like those of ‘deterrence’, ‘prevention’ and ‘reform’. For people can be punished without being prevented from repeating the offence, and without being made any better. It is also a further question whether they themselves or anyone else is deterred from committing the offence by punishment. But ‘punishment’ must involve ‘retribution’, for ‘retribution’ implies doing something to someone in return for what he has done…. Punishment, therefore, must be retributive—by definition.

- ^ a b

Kleining, John (October 1972). «R.S. Peters on Punishment». British Journal of Educational Studies. 20 (3): 259–69. doi:10.1080/00071005.1972.9973352. JSTOR 3120772.Unpleasantness inflicted without authority is revenge, and if whimsical, is spite…. There is no conceptual connection between punishment, or deterrence, or reform, for people can be punished without being prevented from repeating the offence, and without being made better. And it is also a further question whether they themselves, or anyone else is deterred from committing the offence by punishment.

- ^ Amis, S. (1773). «Association for the Prosecution of Felons (WEST BROMWICH)». The British Library: 5.

- ^ Mary Stohr; Anthony Walsh; Craig Hemmens (2008). Corrections: A Text/Reader. Sage. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4129-3773-3.

- ^ Congress. House. Subcommittee on Capital Markets, Insurance, United States. Committee on Financial Services. and Government Sponsored Enterprises (2003). H.R. 2179, the Securities Fraud Deterrence and Investor Restitution Act of 2003 Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, Insurance, and Government Sponsored Enterprises of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Eighth Congress, First Session, June 5, 2003. Purdue University: Committee on Financial Services. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-16-070942-5.

- ^ a b c d e McAnany, Patrick D. (August 2010). «Justification for punishment (Punishment)». Online. Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

Because punishment is both painful and guilt producing, its application calls for a justification. In Western culture, four basic justifications have been given: retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and incapacitation. The history of formal punitive systems is one of a gradual transition from familial and tribal authority to the authority of organized society. Although parents today retain much basic authority to discipline their children, physical beatings and other severe deprivations—once widely tolerated—may now be called child abuse

- ^ M., A, Frankenhaeuser, Rissler (1970). «Effects of punishment on catecholamine release and efficiency of performance». Psychopharmacologia. 17 (5): 378–390. doi:10.1007/BF00403809. PMID 5522998. S2CID 9187358.

- ^ C., Mungan, Murat (2019). «Salience and the severity versus the certainty of punishment». International Review of Law and Economics. 57: 95–100. doi:10.1016/j.irle.2019.01.002. S2CID 147798726.

- ^ Diana Kendall (2009). Sociology in Our Times: The Essentials (7th revised ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-59862-6.

- ^ W, J.C, Furman, Masters (1980). «Affective consequences of social reinforcement, punishment, and neutral behavior». Developmental Psychology. 16 (2): 100–104. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.16.2.100.

- ^ I, Lorge (1933). «The effect of the initial chances for right responses upon the efficacy of intensified reward and of intensified punishment». Journal of Experimental Psychology. 16 (3): 362–373. doi:10.1037/h0070228.

- ^ Church, R.M. (1963). «The varied effects of punishment on behavior». Psychological Review. 70 (5): 369–402. doi:10.1037/h0046499. PMID 14049776.

- ^ T.H., G.A., Clutton-brock, Parker (1995). «Punishment in animal societies». Nature. 373 (6511): 209–216. Bibcode:1995Natur.373..209C. doi:10.1038/373209a0. PMID 7816134. S2CID 21638607.

- ^ Mary Stohr; Anthony Walsh; Craig Hemmens (2008). Corrections: A Text/Reader. Sage. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4129-3773-3.

- ^ Fehr, Gätcher, Ernst, Simon (10 January 2002). «Altruistic punishment in humans». Nature. 415 (6868): 137–140. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..137F. doi:10.1038/415137a. PMID 11805825. S2CID 4310962.

- ^ «Observational Learning in Octopus vulgaris.» Graziano Fiorito, Pietro Scotto. 1992.

- ^ Aliens of the deep sea, documentary. 2011.

- ^ How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence, Rolf Pfeifer, Josh Bongard, foreword by Rodney Brooks. 2006

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche (1886). Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future

- ^ Allen, Elizabeth, et al. (1975). «Against ‘Sociobiology'». [letter] New York Review of Books 22 (Nov. 13).

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1979). Twelve misunderstandings of kin selection

- ^ Lyman Julius Nash, Wisconsin (1919). «Wisconsin Statutes». Legislative Reference Bureau, 1919. 1: 2807–2808.

- ^ Doing Justice – The Choice of Punishments, A Vonhirsch, 1976, p. 220

- ^

Criminology, Larry J. Siegel - ^

”An Economic Analysis of the Criminal Law as Preference-Shaping Policy”, Duke Law Journal, Feb 1990, Vol. 1, Kenneth Dau-Schmidt - ^ Lynch, James P.; Danner, Mona J.E. (1993). «Offense Seriousness Scaling: An Alternative to Scenario Methods». Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 9 (3): 309–22. doi:10.1007/BF01064464. S2CID 144528020.

- ^ reference | J. Mitchell Miller | 2009 | 21st Century Criminology: A Reference Handbook

- ^ reference | Gennaro F. Vito, Jeffrey R. Maahs | 2015 | Criminology

- ^ reference | Frank E. Hagan | 2010 | Introduction to Criminology: Theories, Methods, and Criminal Behavior

- ^ reference | Anthony Walsh, Craig Hemmens | 2008 | Introduction to Criminology: A Text/Reader

- ^ Ronald L. Akers (2013). Criminological Theories: Introduction and Evaluation

- ^ «What’s the Best Way to Discipline My Child?».

- ^ Sir William Draper, Junius (1772). «Lettres». Letters of Junius: 303–305.

- ^ D, Wittman (1974). «Punishment as retribution». Theory and Decision. 4 (3–4): 209–237. doi:10.1007/BF00136647. S2CID 153961464.

- ^ Blackwood, William (1830). «The Southern Review. Vol. V. February and May, 1830». The Southern Review. Michigan State University: William Blackwood. 5: 871.

- ^ Raworth, John (1644). Buchanan, David (ed.). «The Historie of the Reformation of the Church of Scotland Containing Five Books, Together with Some Treatises Conducing to the History»: 358.

- ^ Falls, Margaret (April 1987). «Retribution, Reciprocity, and Respect for Persons». Law and Philosophy. 6 (1): 25–51. doi:10.1007/BF00142639. JSTOR 3504678. S2CID 144282576.

- ^ K. M., Carlsmith (2006). «The roles of retribution and utility in determining punishment». Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 42 (4): 437–451. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.007.

- ^ Popping, S. (1710). True Passive Obedience Restor’d in 1710. In a Dialogue Between a Country-man and a True Patriot. The British Library: S. Popping. p. 8.

- ^ «restitution». La-articles.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ «A New Kind of Criminal Justice», Parade, October 25, 2009, p. 6.

- ^ «Theory, Sources, and Limitations of Criminal Law». Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ J. Robert Lilly, Francis T. Cullen, Richard A. Ball (2014). Criminological Theory: Context and Consequences

- ^ Tim Newburn 2017 Criminology

- ^ «Thom Brooks on Unified Theory of Punishment». Retrieved 2014-09-03.

- ^ G.T, Gwinn (1949). «The effects of punishment on acts motivated by fear». Journal of Experimental Psychology. 39 (2): 260–69. doi:10.1037/h0062431. PMID 18125723.

- ^ Edgeworth, Edgeworth, Maria, Richard Lovell (1825). Works of Maria Edgeworth: Practical education. 1825. the University of California: S. H. Parker. p. 149.

- ^ a b «The Case against Punishment: Retribution, Crime Prevention, and the Law — 2004, Page III by Deirdre Golash».[dead link]

- ^ Mind, Brain and Education, Kurt Fischer, Christina Hinton

- ^ Milbourn, Gene Jr. (November 1996). «Punishment in the workplace creates undesirable side effects». Retrieved November 21, 2018.

References[edit]

- «Punishment» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 653.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Punishment

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Legal Punishment

- Etymology Online

- Brooks, Thom (2012). Punishment. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-85051-3.

- Gade, Christian (2020). «Is restorative justice punishment?». Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 38 (3): 127–155. doi:10.1002/crq.21293.

- Lippke, Richard (2001). «Criminal Offenders and Right Forfeiture». Journal of Social Philosophy. 32 (1): 78–89. doi:10.1111/0047-2786.00080.

- Mack, Eric (2008). «Retribution for Crime». In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 429–431. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n263. ISBN 978-1412965804. OCLC 750831024.

- Zaibert, Leo (2006). Punishment and retribution. Hants, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754623892.

External links[edit]

Look up punishment in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Punishment». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «The Moral Permissibility of Punishment». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

For the most history

punishment has been both painful and public in order to act as

deterrent to others. Physical punishments and public humiliations

were social events and carried out in most accessible parts of towns,

often on market days when the greater part of the population were

present. Justice had to be seen to be done.

One of the most bizarre

methods of execution was inflicted in ancient Rome on people found

guilty of murdering their fathers. Their punishment was to be put in

a sack with a rooster, a viper, and a dog, then drowned along with

three animals. In ancient Greece the custom of allowing a condemned

man to end his own life by poison was extended only to full citizens.

The philosopher Socrates died in this way. Condemned slaves were

beaten to death instead. Stoning was the ancient method of punishment

for adultery among other crimes.

In Turkey if a butcher was found guilty of selling bad meat, he was

tied to a post with a piece of stinking meat fixed under his nose, or

a baker having sold short weight bread could be nailed to his door by

his ear.

One of the most common

punishments for petty offences was the pillory, which stood in the

main square of towns. The offender was locked by hands and head into

the device and made to stand sometimes for days, while crowds jeered

and pelted the offender with rotten vegetables or worse.

In medieval Europe some

methods of execution were deliberately drawn out to inflict maximum

suffering. Felons were tired to a heavy wheel and rolled around the

streets until they were crushed to death. Others were strangled, very

slowly. One of the most terrible punishments was hanging and

quartering. The victim was hanged, beheaded and the body cit into

four pieces. It remained a legal method of punishment in Britain

until 1814. Beheading was normally reserved for those of high rank.

In England a bock and axe was the common method but this was

different from France and Germany where the victim kneeled and the

head was taken off with a swing of the sword.

Death Penalty

The death penalty is the

subject of wide speculation. Many writers have paid attention to such

a theme. For example, in Dostoyevsky’s book Crime

and Punishment the

theory of Raskolnikov allows one to murder people. Is it right to

kill a person, even a terrible and unpleasant, one to make others

happy? Is it right to decide another’s fate in place of God? This

question has been always discussed. I don’t support murders.

Nevertheless, it’s just my point of view and judging from it, I

believe that criminals must be punished.

Crimes are committed every

day. They can be minor or very serious, even monstrous. Imagine a

maniac, for example, a sex fiend, who is guilty of having murdered

several tens of victims. He is usually sent to a prison or to a

mental hospital to spend some years there. It happens in many

countries. A maniac «vindicates» himself in a jail or in a

clinic, spends several years, and then gets freedom. I don’t think

that some years in a mental hospital or in prison can correct the

condition of a maniac. When he is free, he will kill or hurt people

again. Being cruel and ruthless, he wills his own way through his

crowd of victims.

Sometimes criminals are

sentenced to life imprisonment. It’s not enough for a person who

tortured tens of bodies by cutting off their extremities or putting

out somebody’s eyes, for example. Of course, many people think that

the death sentence is not the best way of punishing criminals. They

say that execution is the same as “an eye for an eye”; that if s

a sin to kill any man. However, they forget how many innocent victims

the maniac has butchered.

I think that only people who

committed grave or serious crimes with perversions must be executed.

The others should remain alive. I object that they are sentenced to

be killed by firing squad, by hanging, by using the guillotine or the

gas chamber.

I think that the most

acceptable way of executing is electrocution or using fast acting

poison. No doubt, to discuss the methods of putting someone to death

is awful. Some people think that it’s easier to discuss the problem

instead of solving it. I don’t think so. I vote for the use of the

death penalty, but not for teenagers and women. Maybe I think so

because of the recent events of acts of terrorism, when we saw so

many innocent people die.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical:

Approaches ·

Group therapy ·

Techniques ·

Types of problem ·

Areas of specialism ·

Taxonomies ·

Therapeutic issues ·

Modes of delivery ·

Model translation project ·

Personal experiences ·

This article is in need of attention from a psychologist/academic expert on the subject.

Please help recruit one, or improve this page yourself if you are qualified.

This banner appears on articles that are weak and whose contents should be approached with academic caution.

Punishment is the practice of imposing something unpleasant or aversive on a person or animal in response to an unwanted, disobedient or morally wrong behavior. This is often done in the hope that it will facilitate learning.

Etymology

The word is the abstract substantivation of the verb to punish, which is recorded in English since 1340, deriving from Old French puniss-, an extended form of the stem of punir «to punish,» from Latin punire «inflict a penalty on, cause pain for some offense,» earlier poenire, from poena «penalty, punishment».

Colloquial use of to punish for «to inflict heavy damage or loss» is first recorded in 1801, originally in boxing; for punishing as «hard-hitting» is from 1811.

Definitions

In common usage, the word «punishment» might be described as «an authorized imposition of deprivations — of freedom or privacy or other goods to which the person otherwise has a right, or the imposition of special burdens — because the person has been found guilty of some criminal violation, typically (though not invariably) involving harm to the innocent.» (according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

The most common applications are in legal and similarly ‘regulated’ contexts, being the infliction of some kind of pain or loss upon a person for a misdeed, i.e. for transgressing a law or command (including prohibitions) given by some authority (such as an educator, employer or supervisor, public or private official).

In psychology

- Main article: Punishment (psychology)

In the field of psychology punishment has a more restrictive and technical definition. In this field, punishment is the reduction of a behavior via a stimulus which is applied («positive punishment») or removed («negative punishment»). Making an offending student lose recess or play privileges are examples of negative punishment, while extra chores or spanking are examples of positive punishment. The definition requires that punishment is only determined after the fact by the reduction in behavior; if the offending behavior of the subject does not decrease then it is not considered punishment. There is some conflation of punishment and aversives, though an aversive that does not decrease behavior is not considered punishment.

Scope of application

Punishments are applied for various purposes, most generally, to encourage and enforce proper behavior as defined by society or family. Criminals are punished judicially, by fines, corporal punishment or custodial sentences such as prison; detainees risk further punishments for breaches of internal rules. Children, pupils and other trainees may be punished by their educators or instructors (mainly parents, guardians, or teachers, tutors and coaches).

Slaves, domestic and other servants used to be punishable by their masters. Employees can still be subject to a contractual form of fine or demotion. Most hierarchical organizations, such as military and police forces, or even churches, still apply quite rigid internal discipline, even with a judicial system of their own (court martial, canonical courts).

Punishment may also be applied on moral, especially religious, grounds, as in penance (which is voluntary) or imposed in a theocracy with a religious police (as in a strict Islamic state like Iran or under the Taliban) or (though not a true theocracy) by Inquisition.

History and rationale

The progress of civilization has resulted in a vast change alike in the theory and in the method of punishment. In primitive society punishment was left to the individuals wronged or their families, and was vindictive or retributive: in quantity and quality it would bear no special relation to the character or gravity of the offence.

Gradually there would arise the idea of proportionate punishment, of which the characteristic type is an eye for an eye. The second stage was punishment by individuals under the control of the state, or community; in the third stage, with the growth of law, the state took over the primitive function and provided itself with the machinery of justice for the maintenance of public order. Henceforward crimes are against the state, and the exaction of punishment by the wronged individual is illegal (compare Lynch Law). Even at this stage the vindictive or retributive character of punishment remains, but gradually, and specially after the humanist movement under thinkers like Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, new theories begin to emerge. Two chief trains of thought have combined in the condemnation of primitive theory and practice. On the one hand the retributive principle itself has been very largely superseded by the protective and the reformative; on the other punishments involving bodily pain have become objectionable to the general sense of society. Consequently corporal and even capital punishment occupy a far less prominent position, and tend everywhere to disappear. It began to be recognized also that stereotyped punishments, such as belong to penal codes, fail to take due account of the particular condition of an offence and the character and circumstances of the offender. A fixed fine, for example, operates very unequally on rich and poor.

Modern theories date from the 18th century, when the humanitarian movement began to teach the dignity of the individual and to emphasize his rationality and responsibility. The result was the reduction of punishment both in quantity and in severity, the improvement of the prison system, and the first attempts to study the psychology of crime and to distinguish between classes of criminals with a view to their improvement (see criminology, crime, juvenile delinquency).

These latter problems are the province of criminal anthropology and criminal sociology, sciences so called because they view crime as the outcome of anthropological viz. social conditions. The law breaker is himself a product of social evolution and cannot be regarded as solely responsible for his disposition to transgress. Habitual crime is thus to be treated as a disease. Punishment can, therefore, be justified only insofar as it either protects society by removing temporarily or permanently one who has injured it, or acting as a deterrent, or aims at the moral regeneration of the criminal. Thus the retributive theory of punishment with its criterion of justice as an end in itself gives place to a theory which regards punishment solely as a means to an end, utilitarian or moral, according as the common advantage or the good of the criminal is sought.

Michel Foucault describes in detail the evolution of punishment from hanging, drawing and quartering of medieval times to the modern systems of fines and prisons. He sees a trend in criminal punishment from vengeance by the King to a more practical, utilitarian concern for deterrence and rehabilitation.

A particularly harsh punishment is sometimes said to be draconian, after Draco, the lawgiver of the classical polis of Athens. But as the adjective Spartan still testifies, its wholly militarized rival Sparta was the harshest a state of law can be on its own citizens, e.g. crypteia (including flogging for being caught when stealing as ordered).

In operant conditioning, punishment is the presentation of a stimulus contingent on a response which results in a decrease in response strength (as evidenced by a decrease in the frequency of response). The effectiveness of punishment in suppressing the response depends on many factors, including the intensity of the stimulus and the consistency with which the stimulus is presented when the response occurs. In parenting, additional factors that increase the effectiveness of punishment include a verbal explanation of the reason for the punishment and a good relationship between the parent and the child.

Types of punishments

Punishment can be divided into Positive punishment (the application of an aversive stimulus, such as pain) and Negative punishment (the removal or denial of a desired object, condition, or aversive stimulus).

Criminal punishment

- Socio-economical punishments:

-

- fines or loss of income

- confiscation

- demotion, suspension or expulsion (especially in a strict hierarchy, such as military or clergy)

- restriction or loss of civic and other rights

- community service

- Custodial sentences include imprisonment and other forms of forced detention (e.g., involuntary institutional psychiatry) and hard labor are in fact also physical punishments, even if no actual beatings are in force internally; note that behavioral psychologists do not consider prison a sound punishment because most criminals are repeat offenders, thus, their behavior has not changed. If the behavior does not change then any stimulus that was presented is not punishment just aversive.

- Public humiliation often combines social elements with corporal punishment, and indeed often punishments from two or more categories are combined (especially when these are meant reinforce each-other’s effect) as in the logic of penal harm. In the past, people in some parts of the Western world were punished by being put in the stocks, or by being ducked in water.

- Corporal punishment. Legality of these types of punishment varies from country to country. However it can be defined more widely:

-

- Whipping or caning with various implements and on various body parts

- Marking via branding or mutilations such as amputation of a finger or arm.

- Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, the most extreme form of punishment, sometimes used in countries where beating is seen as inhumane. See use of death penalty worldwide. Methods of capital punishment include crucifixion, hanging, the firing squad, burning at the stake, lethal injection, gas chambers, beheading «by guillotine or axe», and starvation, among others.

For children

Examples of punishments imposed by educators (parents, guardians or teachers etc.; traditions differ greatly in time, place and cultural sphere; some are considered illegal abuse in certain countries) include:

- Corporal punishment:

- Mainly spanking in various modes (banned in some countries, in others even prescribed by law);

- Washing out mouth with soap

- Mild forms of custodial punishments:

- time-outs such as corner-time.

- detention, often combined with tasks like studying, extra homework etc.

- grounding in general or specific refusal of permission to participate in some fun activity or to see a friend (usually seen as a bad influence)

- Temporary (or permanent) removal of privileges, rights, or choices, such as lack of desserts or toys

- Compulsory activity such as extra chores

Non-corporal forms of punishments for children have come under criticism in recent times. Arguments against non-violent modification of behavior include the issue of ethics, and whether one’s will should be forced on children. Positive parenting and Taking Children Seriously are non-punitive alternatives to modifying behavior.

Other

Many religious organizations apply semi-voluntary accepted punishments such as penance.

Possible reasons for punishment

There are many possible reasons that might be given to justify or explain why someone ought to be punished; here follows a broad outline of typical, possibly contradictory justifications.

Rehabilitation

- Main article: Rehabilitation (penology)

Some punishment includes work to reform and rehabilitate the wrongdoer so that they will not commit the offense again. This is distinguished from deterrence, in that the goal here is to change the offender’s attitude to what they have done, and make them come to see that their behaviour was wrong.

Incapacitation

Incapacitation is a justification of punishment that refers to when the offender’s ability to commit further offences is removed. This is a forward-looking justification of punishment that views the future reductions in re-offending as sufficient justification for the punishment. This can occur in one of two ways; the offender’s ability to commit crime can be physically removed, or the offender can be geographically removed.

The offender’s ability to commit crime can be physically removed in several ways. This can include cutting the hands off a thief, as well as other crude punishments. The castration of offenders is another punishment that can be justified by incapacitation, furthered by recent media coverage in Britain of the proposed chemical castration of sexual offenders. Incapacitation, in this sense, can include any number of punishments including taking away the driving license off a dangerous driver but can also include capital punishment.

Despite this, incapacitation is predominately thought of as incarceration. Imprisonment has the effect of confining prisoners, physically preventing them from committing crimes against those outside, i.e. protecting the community. Before the widespread use of imprisonment, banishment was used as a form of incapacitation. Nowadays courts have a flexible array of sentence options available to them that can restrict offender’s movements, and subsequently their ability to commit crime. Football hooligans can, for example, be required to attend centres during football matches.

Selective incapacitation is a modified form of incapacitation that rationalises the practice of giving only dangerous and persistent offenders long, and in some case indefinite, prison sentences. The approach adopts a utilitarian viewpoint that regards the protection, and subsequent happiness, of the majority as justification of giving excessive and indefinite prison sentences. There is, however, strong moral opposition to this concept.

Restoration

- Main article: Restorative Justice

For minor offences, punishment may take the form of the offender «righting the wrong»; for example, a vandal might be made to clean up the mess he has made.

In more serious cases, punishment in the form of fines and compensation payments may also be considered a sort of «restoration».

Some libertarians argue that full restoration or restitution on an individualistic basis is all that is ever just, and that this is compatible with both retributivism and a utilitarian degree of deterrence.[1]

Retribution

- Main article: Retributive justice