|

Japan 日本国 (Japanese) |

|

|---|---|

|

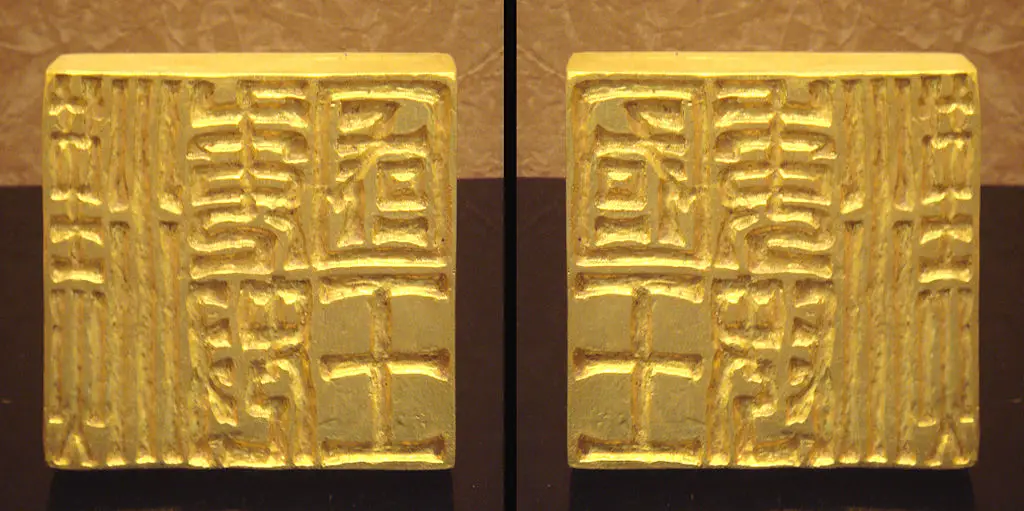

Flag Imperial Seal |

|

| Anthem: 君が代 Kimigayo «His Imperial Majesty’s Reign» |

|

| Government Seal

|

|

Territory controlled by Japan in dark green; territory claimed but not controlled shown in light green |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Tokyo 35°41′N 139°46′E / 35.683°N 139.767°E |

| Official languages | Japanese (de facto) |

| Demonym(s) | Japanese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

|

• Emperor |

Naruhito |

|

• Prime Minister |

Fumio Kishida |

| Legislature | National Diet |

|

• Upper house |

House of Councillors |

|

• Lower house |

House of Representatives |

| Formation | |

|

• Imperial Dynasty established |

February 11, 660 BC |

|

• Meiji Constitution |

November 29, 1890 |

|

• Current constitution |

May 3, 1947 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

377,975 km2 (145,937 sq mi)[1] (62nd) |

|

• Water (%) |

1.4 (2015)[2] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

|

|

• 2020 census |

126,226,568[4] |

|

• Density |

330/km2 (854.7/sq mi) (44th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 19th |

| Currency | Japanese yen (¥) |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (JST) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +81 |

| ISO 3166 code | JP |

| Internet TLD | .jp |

Japan (Japanese: 日本, Nippon or Nihon,[nb 1] and formally 日本国, Nihonkoku)[nb 2] is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north toward the East China Sea, Philippine Sea, and Taiwan in the south. Japan is a part of the Ring of Fire, and spans an archipelago of 14,125 islands, with the five main islands being Hokkaido, Honshu (the «mainland»), Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa. Tokyo is the nation’s capital and largest city, followed by Yokohama, Osaka, Nagoya, Sapporo, Fukuoka, Kobe, and Kyoto.

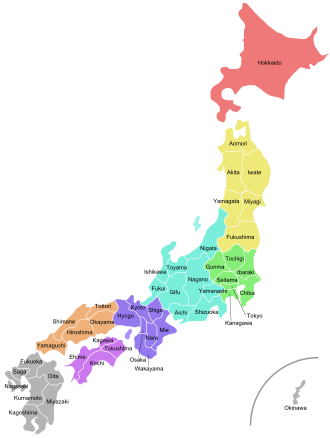

Japan is the eleventh most populous country in the world, as well as one of the most densely populated and urbanized. About three-fourths of the country’s terrain is mountainous, concentrating its population of almost 125 million on narrow coastal plains. Japan is divided into 47 administrative prefectures and eight traditional regions. The Greater Tokyo Area is the most populous metropolitan area in the world, with more than 37.2 million residents.

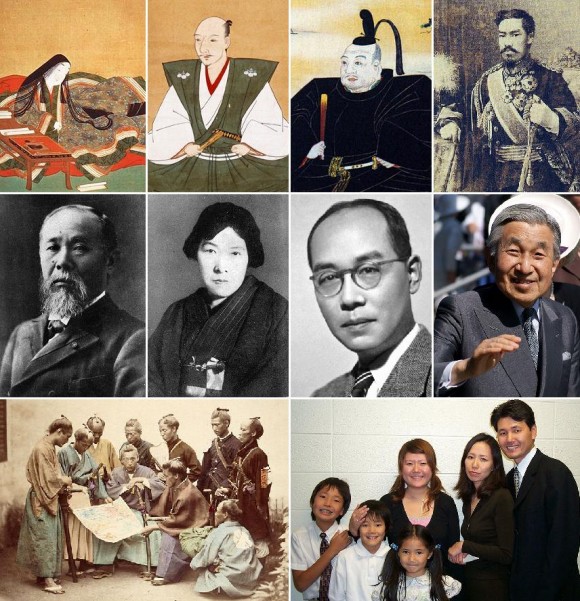

Japan has been inhabited since the Upper Paleolithic period (30,000 BC). Between the 4th and 9th centuries, the kingdoms of Japan became unified under an emperor and the imperial court based in Heian-kyō. Beginning in the 12th century, political power was held by a series of military dictators (shōgun) and feudal lords (daimyō) and enforced by a class of warrior nobility (samurai). After a century-long period of civil war, the country was reunified in 1603 under the Tokugawa shogunate, which enacted an isolationist foreign policy. In 1854, a United States fleet forced Japan to open trade to the West, which led to the end of the shogunate and the restoration of imperial power in 1868. In the Meiji period, the Empire of Japan adopted a Western-modeled constitution and pursued a program of industrialization and modernization. Amidst a rise in militarism and overseas colonization, Japan invaded China in 1937 and entered World War II as an Axis power in 1941. After suffering defeat in the Pacific War and two atomic bombings, Japan surrendered in 1945 and came under a seven-year Allied occupation, during which it adopted a new constitution.

Under the 1947 constitution, Japan has maintained a unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy with a bicameral legislature, the National Diet. Japan is a developed country and a great power. It is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations, G20, OECD, and the Group of Seven. Its economy is the world’s third-largest by nominal GDP and the fourth-largest by PPP, with its per capita income ranking at 36th highest in the world. Although Japan has renounced its right to declare war, the country maintains Self-Defense Forces that rank as one of the world’s strongest militaries. Japan has the world’s highest life expectancy, though it is experiencing a population decline. A global leader in the automotive, robotics and electronics industries, the country has made significant contributions to science and technology. Japan is also considered a cultural superpower as the culture of Japan is well known around the world, including its art, cuisine, film, music, and popular culture, which encompasses prominent manga, anime and video game industries.

Etymology

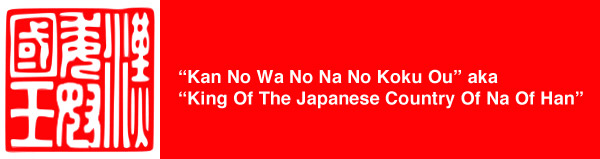

The name for Japan in Japanese is written using the kanji 日本 and is pronounced Nippon or Nihon.[9] Before 日本 was adopted in the early 8th century, the country was known in China as Wa (倭, changed in Japan around 757 to 和) and in Japan by the endonym Yamato.[10] Nippon, the original Sino-Japanese reading of the characters, is favored for official uses, including on banknotes and postage stamps.[9] Nihon is typically used in everyday speech and reflects shifts in Japanese phonology during the Edo period.[10] The characters 日本 mean «sun origin»,[9] which is the source of the popular Western epithet «Land of the Rising Sun».[11]

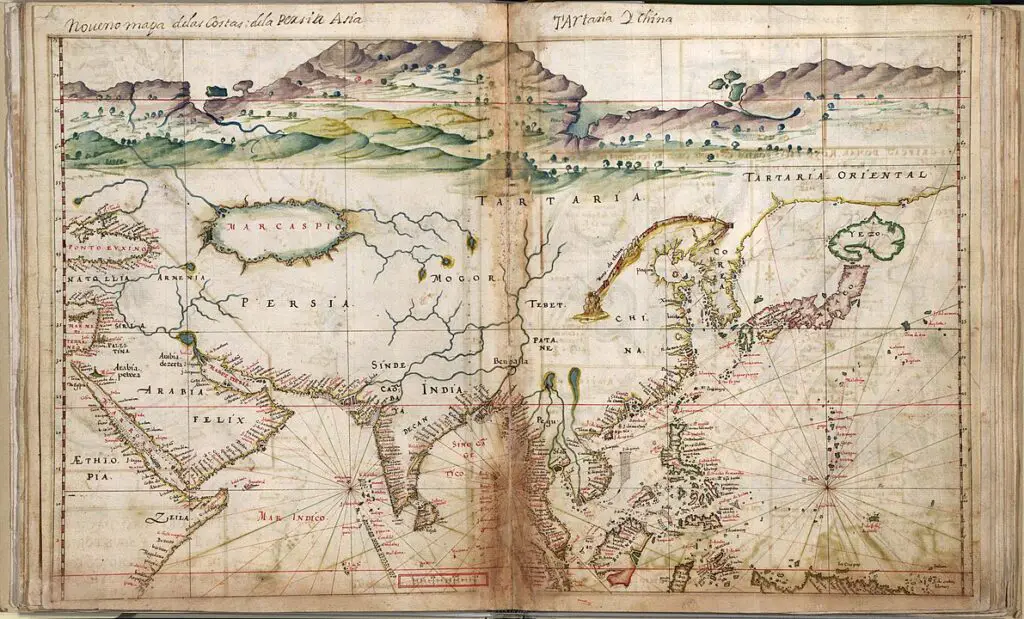

The name «Japan» is based on Chinese pronunciations of 日本 and was introduced to European languages through early trade. In the 13th century, Marco Polo recorded the early Mandarin or Wu Chinese pronunciation of the characters 日本國 as Cipangu.[12] The old Malay name for Japan, Japang or Japun, was borrowed from a southern coastal Chinese dialect and encountered by Portuguese traders in Southeast Asia, who brought the word to Europe in the early 16th century.[13] The first version of the name in English appears in a book published in 1577, which spelled the name as Giapan in a translation of a 1565 Portuguese letter.[14][15]

History

Prehistoric to classical history

A Paleolithic culture from around 30,000 BC constitutes the first known habitation of the islands of Japan.[16] This was followed from around 14,500 BC (the start of the Jōmon period) by a Mesolithic to Neolithic semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer culture characterized by pit dwelling and rudimentary agriculture.[17] Clay vessels from the period are among the oldest surviving examples of pottery.[18] From around 700 BC, the Japonic-speaking Yayoi people began to enter the archipelago from the Korean Peninsula,[19][20][21] intermingling with the Jōmon;[21] the Yayoi period saw the introduction of practices including wet-rice farming,[22] a new style of pottery,[23] and metallurgy from China and Korea.[24] According to legend, Emperor Jimmu (grandson of Amaterasu) founded a kingdom in central Japan in 660 BC, beginning a continuous imperial line.[25]

Japan first appears in written history in the Chinese Book of Han, completed in 111 AD. Buddhism was introduced to Japan from Baekje (a Korean kingdom) in 552, but the development of Japanese Buddhism was primarily influenced by China.[26] Despite early resistance, Buddhism was promoted by the ruling class, including figures like Prince Shōtoku, and gained widespread acceptance beginning in the Asuka period (592–710).[27]

The far-reaching Taika Reforms in 645 nationalized all land in Japan, to be distributed equally among cultivators, and ordered the compilation of a household registry as the basis for a new system of taxation.[28] The Jinshin War of 672, a bloody conflict between Prince Ōama and his nephew Prince Ōtomo, became a major catalyst for further administrative reforms.[29] These reforms culminated with the promulgation of the Taihō Code, which consolidated existing statutes and established the structure of the central and subordinate local governments.[28] These legal reforms created the ritsuryō state, a system of Chinese-style centralized government that remained in place for half a millennium.[29]

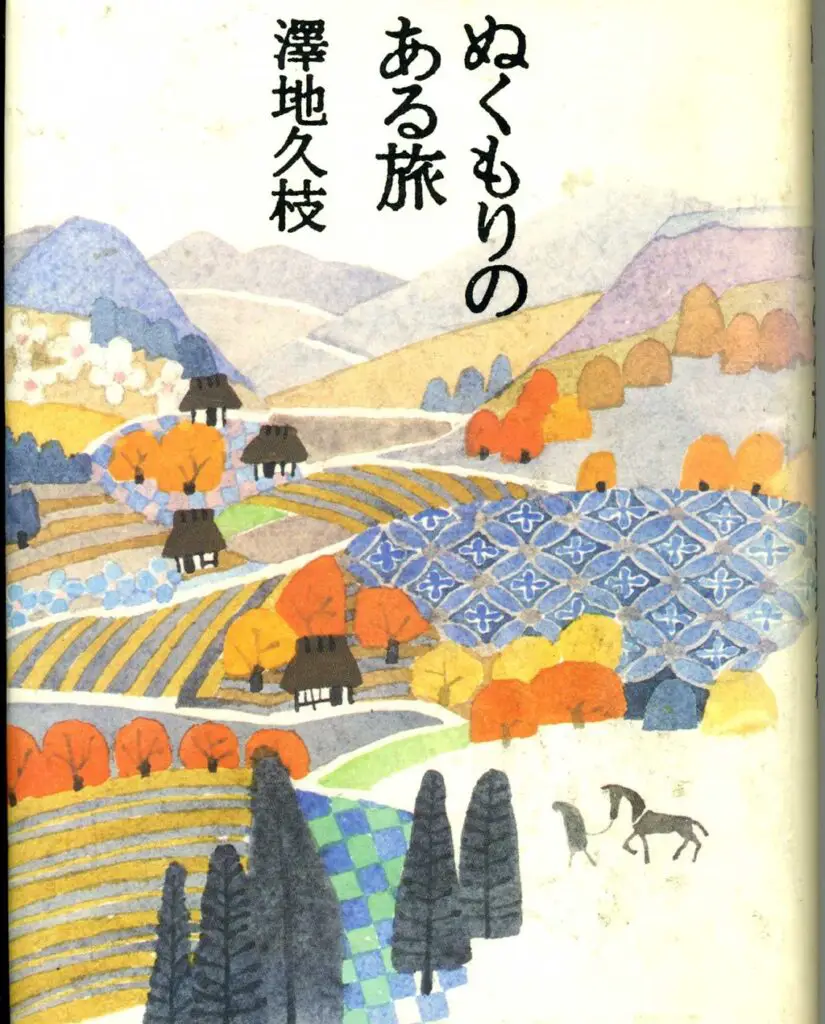

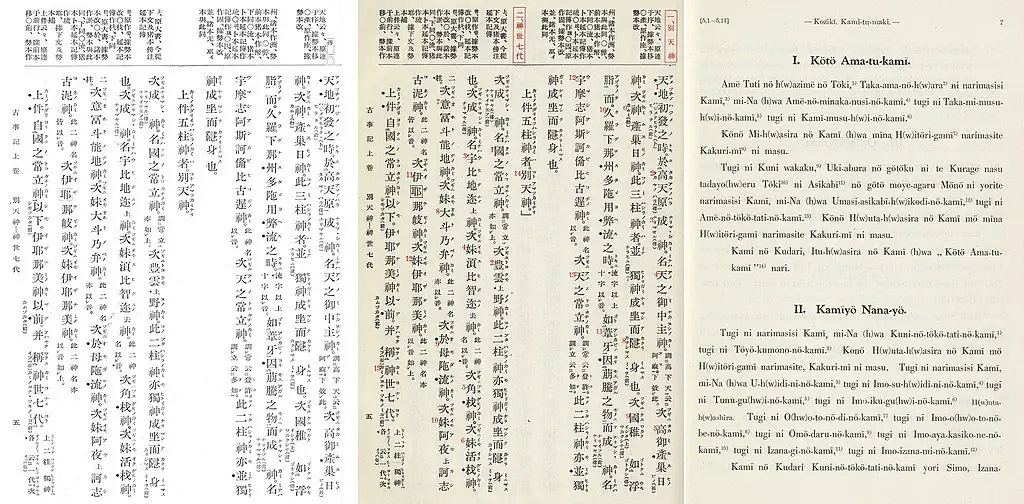

The Nara period (710–784) marked the emergence of a Japanese state centered on the Imperial Court in Heijō-kyō (modern Nara). The period is characterized by the appearance of a nascent literary culture with the completion of the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720), as well as the development of Buddhist-inspired artwork and architecture.[30][31] A smallpox epidemic in 735–737 is believed to have killed as much as one-third of Japan’s population.[31][32] In 784, Emperor Kanmu moved the capital, settling on Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto) in 794.[31] This marked the beginning of the Heian period (794–1185), during which a distinctly indigenous Japanese culture emerged. Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji and the lyrics of Japan’s national anthem «Kimigayo» were written during this time.[33]

Feudal era

Japan’s feudal era was characterized by the emergence and dominance of a ruling class of warriors, the samurai.[34] In 1185, following the defeat of the Taira clan in the Genpei War, samurai Minamoto no Yoritomo established a military government at Kamakura.[35] After Yoritomo’s death, the Hōjō clan came to power as regents for the shōgun.[31] The Zen school of Buddhism was introduced from China in the Kamakura period (1185–1333) and became popular among the samurai class.[36] The Kamakura shogunate repelled Mongol invasions in 1274 and 1281 but was eventually overthrown by Emperor Go-Daigo.[31] Go-Daigo was defeated by Ashikaga Takauji in 1336, beginning the Muromachi period (1336–1573).[37] The succeeding Ashikaga shogunate failed to control the feudal warlords (daimyō) and a civil war began in 1467, opening the century-long Sengoku period («Warring States»).[38]

During the 16th century, Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries reached Japan for the first time, initiating direct commercial and cultural exchange between Japan and the West.[31][39] Oda Nobunaga used European technology and firearms to conquer many other daimyō;[40] his consolidation of power began what was known as the Azuchi–Momoyama period.[41] After the death of Nobunaga in 1582, his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, unified the nation in the early 1590s and launched two unsuccessful invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597.[31]

Tokugawa Ieyasu served as regent for Hideyoshi’s son Toyotomi Hideyori and used his position to gain political and military support.[42] When open war broke out, Ieyasu defeated rival clans in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. He was appointed shōgun by Emperor Go-Yōzei in 1603 and established the Tokugawa shogunate at Edo (modern Tokyo).[43] The shogunate enacted measures including buke shohatto, as a code of conduct to control the autonomous daimyō,[44] and in 1639 the isolationist sakoku («closed country») policy that spanned the two and a half centuries of tenuous political unity known as the Edo period (1603–1868).[43][45] Modern Japan’s economic growth began in this period, resulting in roads and water transportation routes, as well as financial instruments such as futures contracts, banking and insurance of the Osaka rice brokers.[46] The study of Western sciences (rangaku) continued through contact with the Dutch enclave in Nagasaki.[43] The Edo period gave rise to kokugaku («national studies»), the study of Japan by the Japanese.[47]

Modern era

The United States Navy sent Commodore Matthew C. Perry to force the opening of Japan to the outside world. Arriving at Uraga with four «Black Ships» in July 1853, the Perry Expedition resulted in the March 1854 Convention of Kanagawa.[43] Subsequent similar treaties with other Western countries brought economic and political crises.[43] The resignation of the shōgun led to the Boshin War and the establishment of a centralized state nominally unified under the emperor (the Meiji Restoration).[48] Adopting Western political, judicial, and military institutions, the Cabinet organized the Privy Council, introduced the Meiji Constitution (November 29, 1890), and assembled the Imperial Diet.[49] During the Meiji period (1868–1912), the Empire of Japan emerged as the most developed nation in Asia and as an industrialized world power that pursued military conflict to expand its sphere of influence.[50][51][52] After victories in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), Japan gained control of Taiwan, Korea and the southern half of Sakhalin.[53][49] The Japanese population doubled from 35 million in 1873 to 70 million by 1935, with a significant shift to urbanization.[54][55]

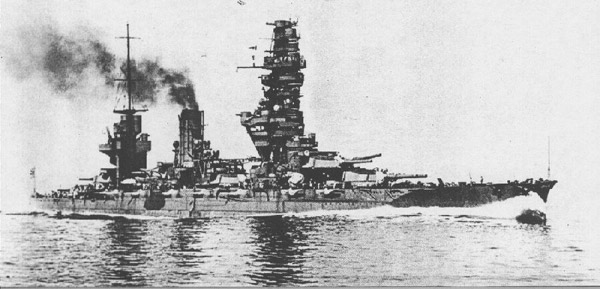

The early 20th century saw a period of Taishō democracy (1912–1926) overshadowed by increasing expansionism and militarization.[56][57] World War I allowed Japan, which joined the side of the victorious Allies, to capture German possessions in the Pacific and in China.[57] The 1920s saw a political shift towards statism, a period of lawlessness following the 1923 Great Tokyo Earthquake, the passing of laws against political dissent, and a series of attempted coups.[55][58][59] This process accelerated during the 1930s, spawning several radical nationalist groups that shared a hostility to liberal democracy and a dedication to expansion in Asia. In 1931, Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria; following international condemnation of the occupation, it resigned from the League of Nations two years later.[60] In 1936, Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany; the 1940 Tripartite Pact made it one of the Axis Powers.[55]

Japan’s imperial ambitions ended on September 2, 1945, with the country’s surrender to the Allies.

The Empire of Japan invaded other parts of China in 1937, precipitating the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).[61] In 1940, the Empire invaded French Indochina, after which the United States placed an oil embargo on Japan.[55][62] On December 7–8, 1941, Japanese forces carried out surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor, as well as on British forces in Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, among others, beginning World War II in the Pacific.[63] Throughout areas occupied by Japan during the war, numerous abuses were committed against local inhabitants, with many forced into sexual slavery.[64] After Allied victories during the next four years, which culminated in the Soviet invasion of Manchuria and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Japan agreed to an unconditional surrender.[65] The war cost Japan its colonies and millions of lives.[55] The Allies (led by the United States) repatriated millions of Japanese settlers from their former colonies and military camps throughout Asia, largely eliminating the Japanese Empire and its influence over the territories it conquered.[66][67] The Allies convened the International Military Tribunal for the Far East to prosecute Japanese leaders for war crimes.[67]

In 1947, Japan adopted a new constitution emphasizing liberal democratic practices.[67] The Allied occupation ended with the Treaty of San Francisco in 1952,[68] and Japan was granted membership in the United Nations in 1956.[67] A period of record growth propelled Japan to become the second-largest economy in the world;[67] this ended in the mid-1990s after the popping of an asset price bubble, beginning the «Lost Decade».[69] On March 11, 2011, Japan suffered one of the largest earthquakes in its recorded history, triggering the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[70] On May 1, 2019, after the historic abdication of Emperor Akihito, his son Naruhito became Emperor, beginning the Reiwa era.[71]

Geography

Japan comprises 14,125 islands extending along the Pacific coast of Asia.[72] It stretches over 3000 km (1900 mi) northeast–southwest from the Sea of Okhotsk to the East China Sea.[73][74] The country’s five main islands, from north to south, are Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and Okinawa.[75] The Ryukyu Islands, which include Okinawa, are a chain to the south of Kyushu. The Nanpō Islands are south and east of the main islands of Japan. Together they are often known as the Japanese archipelago.[76] As of 2019, Japan’s territory is 377,975.24 km2 (145,937.06 sq mi).[1] Japan has the sixth-longest coastline in the world at 29,751 km (18,486 mi). Because of its far-flung outlying islands, Japan has the eighth-largest exclusive economic zone in the world, covering 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi).[77][78]

The Japanese archipelago is 67% forests and 14% agricultural.[79] The primarily rugged and mountainous terrain is restricted for habitation.[80] Thus the habitable zones, mainly in the coastal areas, have very high population densities: Japan is the 40th most densely populated country.[81][82] Honshu has the highest population density at 450 persons/km2 (1200/sq mi) as of 2010, while Hokkaido has the lowest density of 64.5 persons/km2 as of 2016.[83] As of 2014, approximately 0.5% of Japan’s total area is reclaimed land (umetatechi).[84] Lake Biwa is an ancient lake and the country’s largest freshwater lake.[85]

Japan is substantially prone to earthquakes, tsunami and volcanic eruptions because of its location along the Pacific Ring of Fire.[86] It has the 17th highest natural disaster risk as measured in the 2016 World Risk Index.[87] Japan has 111 active volcanoes.[88] Destructive earthquakes, often resulting in tsunami, occur several times each century;[89] the 1923 Tokyo earthquake killed over 140,000 people.[90] More recent major quakes are the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, which triggered a large tsunami.[70]

Climate

The climate of Japan is predominantly temperate but varies greatly from north to south. The northernmost region, Hokkaido, has a humid continental climate with long, cold winters and very warm to cool summers. Precipitation is not heavy, but the islands usually develop deep snowbanks in the winter.[91]

In the Sea of Japan region on Honshu’s west coast, northwest winter winds bring heavy snowfall during winter. In the summer, the region sometimes experiences extremely hot temperatures because of the foehn.[92] The Central Highland has a typical inland humid continental climate, with large temperature differences between summer and winter. The mountains of the Chūgoku and Shikoku regions shelter the Seto Inland Sea from seasonal winds, bringing mild weather year-round.[91]

The Pacific coast features a humid subtropical climate that experiences milder winters with occasional snowfall and hot, humid summers because of the southeast seasonal wind. The Ryukyu and Nanpō Islands have a subtropical climate, with warm winters and hot summers. Precipitation is very heavy, especially during the rainy season.[91] The main rainy season begins in early May in Okinawa, and the rain front gradually moves north. In late summer and early autumn, typhoons often bring heavy rain.[93] According to the Environment Ministry, heavy rainfall and increasing temperatures have caused problems in the agricultural industry and elsewhere.[94] The highest temperature ever measured in Japan, 41.1 °C (106.0 °F), was recorded on July 23, 2018,[95] and repeated on August 17, 2020.[96]

Biodiversity

Japan has nine forest ecoregions which reflect the climate and geography of the islands. They range from subtropical moist broadleaf forests in the Ryūkyū and Bonin Islands, to temperate broadleaf and mixed forests in the mild climate regions of the main islands, to temperate coniferous forests in the cold, winter portions of the northern islands.[97] Japan has over 90,000 species of wildlife as of 2019,[98] including the brown bear, the Japanese macaque, the Japanese raccoon dog, the small Japanese field mouse, and the Japanese giant salamander.[99]

A large network of national parks has been established to protect important areas of flora and fauna as well as 52 Ramsar wetland sites.[100][101] Four sites have been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for their outstanding natural value.[102]

Environment

In the period of rapid economic growth after World War II, environmental policies were downplayed by the government and industrial corporations; as a result, environmental pollution was widespread in the 1950s and 1960s. Responding to rising concerns, the government introduced environmental protection laws in 1970.[103] The oil crisis in 1973 also encouraged the efficient use of energy because of Japan’s lack of natural resources.[104]

Japan ranks 20th in the 2018 Environmental Performance Index, which measures a nation’s commitment to environmental sustainability.[105] Japan is the world’s fifth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide.[94] As the host and signatory of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, Japan is under treaty obligation to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions and to take other steps to curb climate change.[106] In 2020 the government of Japan announced a target of carbon-neutrality by 2050.[107] Environmental issues include urban air pollution (NOx, suspended particulate matter, and toxics), waste management, water eutrophication, nature conservation, climate change, chemical management and international co-operation for conservation.[108]

Government and politics

Japan is a unitary state and constitutional monarchy in which the power of the Emperor is limited to a ceremonial role.[109] Executive power is instead wielded by the Prime Minister of Japan and his Cabinet, whose sovereignty is vested in the Japanese people.[110] Naruhito is the Emperor of Japan, having succeeded his father Akihito upon his accession to the Chrysanthemum Throne in 2019.[109]

Japan’s legislative organ is the National Diet, a bicameral parliament.[109] It consists of a lower House of Representatives with 465 seats, elected by popular vote every four years or when dissolved, and an upper House of Councillors with 245 seats, whose popularly-elected members serve six-year terms.[111] There is universal suffrage for adults over 18 years of age,[112] with a secret ballot for all elected offices.[110] The prime minister as the head of government has the power to appoint and dismiss Ministers of State, and is appointed by the emperor after being designated from among the members of the Diet.[111] Fumio Kishida is Japan’s prime minister; he took office after winning the 2021 Liberal Democratic Party leadership election.[113] The right-wing big tent Liberal Democratic Party has been the dominant party in the country since the 1950s, often called the 1955 System.[114]

Historically influenced by Chinese law, the Japanese legal system developed independently during the Edo period through texts such as Kujikata Osadamegaki.[115] Since the late 19th century, the judicial system has been largely based on the civil law of Europe, notably Germany. In 1896, Japan established a civil code based on the German Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, which remains in effect with post–World War II modifications.[116] The Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947, is the oldest unamended constitution in the world.[117] Statutory law originates in the legislature, and the constitution requires that the emperor promulgate legislation passed by the Diet without giving him the power to oppose legislation. The main body of Japanese statutory law is called the Six Codes.[115] Japan’s court system is divided into four basic tiers: the Supreme Court and three levels of lower courts.[118]

Administrative divisions

Japan is divided into 47 prefectures, each overseen by an elected governor and legislature.[109] In the following table, the prefectures are grouped by region:[119]

|

Prefectures of Japan with colored regions |

Hokkaido 1. Hokkaido |

Tōhoku 2. Aomori 7. Fukushima |

Kantō 8. Ibaraki 14. Kanagawa |

Chūbu 15. Niigata 23. Aichi |

|

Kansai 24. Mie 30. Wakayama |

Chūgoku 31. Tottori 35. Yamaguchi |

Shikoku 36. Tokushima 39. Kōchi |

Kyūshū 40. Fukuoka 47. Okinawa |

Foreign relations

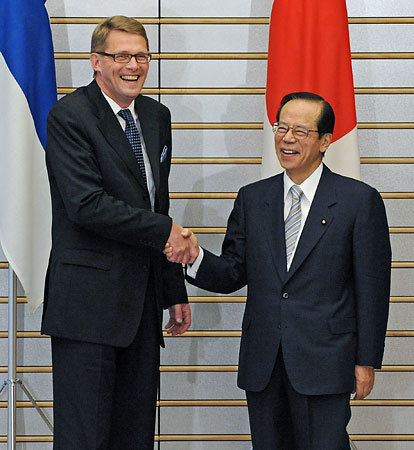

Japan is a member of both the G7 and the G20.

A member state of the United Nations since 1956, Japan is one of the G4 nations seeking reform of the Security Council.[120] Japan is a member of the G7, APEC, and «ASEAN Plus Three», and is a participant in the East Asia Summit.[121] It is the world’s fifth-largest donor of official development assistance, donating US$9.2 billion in 2014.[122] In 2019, Japan had the fourth-largest diplomatic network in the world.[123]

Japan has close economic and military relations with the United States, with which it maintains a security alliance.[124] The United States is a major market for Japanese exports and a major source of Japanese imports, and is committed to defending the country, with military bases in Japan.[124] Japan is also a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (more commonly «the Quad»), a multilateral security dialogue reformed in 2017 aiming to limit Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region, along with the United States, Australia, and India, reflecting existing relations and patterns of cooperation.[125][126]

Japan’s relationship with South Korea had historically been strained because of Japan’s treatment of Koreans during Japanese colonial rule, particularly over the issue of comfort women. In 2015, Japan agreed to settle the comfort women dispute with South Korea by issuing a formal apology and paying money to the surviving comfort women.[127] As of 2019 Japan is a major importer of Korean music (K-pop), television (K-dramas), and other cultural products.[128][129]

Japan is engaged in several territorial disputes with its neighbors. Japan contests Russia’s control of the Southern Kuril Islands, which were occupied by the Soviet Union in 1945.[130] South Korea’s control of the Liancourt Rocks is acknowledged but not accepted as they are claimed by Japan.[131] Japan has strained relations with China and Taiwan over the Senkaku Islands and the status of Okinotorishima.[132]

Military

Japan is the second-highest-ranked Asian country in the 2022 Global Peace Index, after Singapore.[133] It spent 1% of its total GDP on its defence budget in 2020,[134] and maintains the ninth-largest military budget in the world.[135] The country’s military (the Japan Self-Defense Forces) is restricted by Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, which renounces Japan’s right to declare war or use military force in international disputes.[136] The military is governed by the Ministry of Defense, and primarily consists of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force. The deployment of troops to Iraq and Afghanistan marked the first overseas use of Japan’s military since World War II.[137]

The Government of Japan has been making changes to its security policy which include the establishment of the National Security Council, the adoption of the National Security Strategy, and the development of the National Defense Program Guidelines.[138] In May 2014, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe said Japan wanted to shed the passiveness it has maintained since the end of World War II and take more responsibility for regional security.[139] Recent tensions, particularly with North Korea and China, have reignited the debate over the status of the JSDF and its relation to Japanese society.[140][141]

Domestic law enforcement

Domestic security in Japan is provided mainly by the prefectural police departments, under the oversight of the National Police Agency.[142] As the central coordinating body for the Prefectural Police Departments, the National Police Agency is administered by the National Public Safety Commission.[143] The Special Assault Team comprises national-level counter-terrorism tactical units that cooperate with territorial-level Anti-Firearms Squads and Counter-NBC Terrorism Squads.[144] The Japan Coast Guard guards territorial waters surrounding Japan and uses surveillance and control countermeasures against smuggling, marine environmental crime, poaching, piracy, spy ships, unauthorized foreign fishing vessels, and illegal immigration.[145]

The Firearm and Sword Possession Control Law strictly regulates the civilian ownership of guns, swords, and other weaponry.[146][147] According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, among the member states of the UN that report statistics as of 2018, the incidence rates of violent crimes such as murder, abduction, sexual violence, and robbery are very low in Japan.[148][149][150][151]

Economy

Japan has the world’s third-largest economy by nominal GDP, after that of the United States and China; and the fourth-largest economy by PPP. As of 2020, Japan’s labor force is the world’s eighth-largest, and consists of 66.5 million workers.[77] As of 2021, Japan has a low unemployment rate of around 2.8%.[152] Its poverty rate is the second highest among the G7 nations,[153] and exceeds 15.7% of the population.[154] Japan has the highest ratio of public debt to GDP among advanced economies,[155] with national debt estimated at 248% relative to GDP as of 2022.[156] The Japanese yen is the world’s third-largest reserve currency after the US dollar and the euro.[157]

Japan was the world’s fourth-largest exporter and importer in 2021.[158][159] Its exports amounted to 15.6% of its total GDP in 2020.[160] As of 2019, Japan’s main export markets were the United States (19.8 percent) and China (19.1 percent).[111] Its main exports are motor vehicles, iron and steel products, semiconductors, and auto parts.[77] Japan’s main import markets as of 2019 were China (23.5 percent), the United States (11 percent), and Australia (6.3 percent).[111] Japan’s main imports are machinery and equipment, fossil fuels, foodstuffs, chemicals, and raw materials for its industries.[111]

The Japanese variant of capitalism has many distinct features: keiretsu enterprises are influential, and lifetime employment and seniority-based career advancement are common in the Japanese work environment.[161][162] Japan has a large cooperative sector, with three of the world’s ten largest cooperatives, including the largest consumer cooperative and the largest agricultural cooperative as of 2018.[163] It ranks highly for competitiveness and economic freedom. Japan ranked sixth in the Global Competitiveness Report in 2019.[164] It attracted 31.9 million international tourists in 2019,[165] and was ranked eleventh in the world in 2019 for inbound tourism.[166] The 2021 Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report ranked Japan first in the world out of 117 countries.[167] Its international tourism receipts in 2019 amounted to $46.1 billion.[166]

Agriculture and fishery

The Japanese agricultural sector accounts for about 1.2% of the total country’s GDP as of 2018.[111] Only 11.5% of Japan’s land is suitable for cultivation.[168] Because of this lack of arable land, a system of terraces is used to farm in small areas.[169] This results in one of the world’s highest levels of crop yields per unit area, with an agricultural self-sufficiency rate of about 50% as of 2018.[170] Japan’s small agricultural sector is highly subsidized and protected.[171] There has been a growing concern about farming as farmers are aging with a difficult time finding successors.[172]

Japan ranked seventh in the world in tonnage of fish caught and captured 3,167,610 metric tons of fish in 2016, down from an annual average of 4,000,000 tons over the previous decade.[173] Japan maintains one of the world’s largest fishing fleets and accounts for nearly 15% of the global catch,[77] prompting critiques that Japan’s fishing is leading to depletion in fish stocks such as tuna.[174] Japan has sparked controversy by supporting commercial whaling.[175]

Industry and services

Japan has a large industrial capacity and is home to some of the «largest and most technologically advanced producers of motor vehicles, machine tools, steel and nonferrous metals, ships, chemical substances, textiles, and processed foods».[77] Japan’s industrial sector makes up approximately 27.5% of its GDP.[77] The country’s manufacturing output is the third highest in the world as of 2019.[177]

Japan is the third-largest automobile producer in the world as of 2017 and is home to Toyota, the world’s largest automobile company by vehicle production.[176][178] The Japanese shipbuilding industry faces competition from South Korea and China; a 2020 government initiative identified this sector as a target for increasing exports.[179]

Japan’s service sector accounts for about 70% of its total economic output as of 2019.[180] Banking, retail, transportation, and telecommunications are all major industries, with companies such as Toyota, Mitsubishi UFJ, -NTT, ÆON, Softbank, Hitachi, and Itochu listed as among the largest in the world.[181][182]

Science and technology

Japan is a leading nation in scientific research, particularly in the natural sciences and engineering. The country ranks twelfth among the most innovative countries in the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index and 13th in the Global Innovation Index in 2022, up from 15th in 2019.[183][184] Relative to gross domestic product, Japan’s research and development budget is the second highest in the world,[185] with 867,000 researchers sharing a 19-trillion-yen research and development budget as of 2017.[186] The country has produced twenty-two Nobel laureates in either physics, chemistry or medicine,[187] and three Fields medalists.[188]

Japan leads the world in robotics production and use, supplying 55% of the world’s 2017 total.[189] Japan has the second highest number of researchers in science and technology per capita in the world with 14 per 1000 employees.[190]

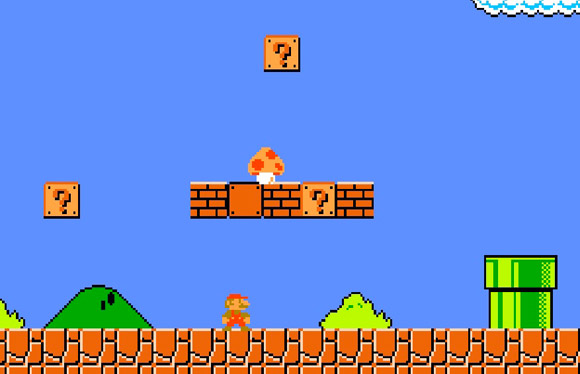

Once considered the strongest in the world, the Japanese consumer electronics industry is in a state of decline as competition arises in countries like South Korea and China.[191] However, video gaming in Japan remains a major industry. In 2014, Japan’s consumer video game market grossed $9.6 billion, with $5.8 billion coming from mobile gaming.[192] By 2015, Japan had become the world’s fourth-largest PC game market, behind only China, the United States, and South Korea.[193]

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency is Japan’s national space agency; it conducts space, planetary, and aviation research, and leads development of rockets and satellites.[194] It is a participant in the International Space Station: the Japanese Experiment Module (Kibō) was added to the station during Space Shuttle assembly flights in 2008.[195] The space probe Akatsuki was launched in 2010 and achieved orbit around Venus in 2015.[196] Japan’s plans in space exploration include building a moon base and landing astronauts by 2030.[197] In 2007, it launched lunar explorer SELENE (Selenological and Engineering Explorer) from Tanegashima Space Center. The largest lunar mission since the Apollo program, its purpose was to gather data on the moon’s origin and evolution. The explorer entered a lunar orbit on October 4, 2007,[198][199] and was deliberately crashed into the Moon on June 11, 2009.[200]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Japan has invested heavily in transportation infrastructure.[201] The country has approximately 1,200,000 kilometers (750,000 miles) of roads made up of 1,000,000 kilometers (620,000 miles) of city, town and village roads, 130,000 kilometers (81,000 miles) of prefectural roads, 54,736 kilometers (34,011 miles) of general national highways and 7641 kilometers (4748 miles) of national expressways as of 2017.[202]

Since privatization in 1987,[203] dozens of Japanese railway companies compete in regional and local passenger transportation markets; major companies include seven JR enterprises, Kintetsu, Seibu Railway and Keio Corporation. The high-speed Shinkansen (bullet trains) that connect major cities are known for their safety and punctuality.[204]

There are 175 airports in Japan as of 2013.[77] The largest domestic airport, Haneda Airport in Tokyo, was Asia’s second-busiest airport in 2019.[205] The Keihin and Hanshin superport hubs are among the largest in the world, at 7.98 and 5.22 million TEU respectively as of 2017.[206]

Energy

As of 2019, 37.1% of energy in Japan was produced from petroleum, 25.1% from coal, 22.4% from natural gas, 3.5% from hydropower and 2.8% from nuclear power, among other sources. Nuclear power was down from 11.2 percent in 2010.[207] By May 2012 all of the country’s nuclear power plants had been taken offline because of ongoing public opposition following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in March 2011, though government officials continued to try to sway public opinion in favor of returning at least some to service.[208] The Sendai Nuclear Power Plant restarted in 2015,[209] and since then several other nuclear power plants have been restarted.[210] Japan lacks significant domestic reserves and has a heavy dependence on imported energy.[211] The country has therefore aimed to diversify its sources and maintain high levels of energy efficiency.[212]

Water supply and sanitation

Responsibility for the water and sanitation sector is shared between the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, in charge of water supply for domestic use; the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, in charge of water resources development as well as sanitation; the Ministry of the Environment, in charge of ambient water quality and environmental preservation; and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, in charge of performance benchmarking of utilities.[213] Access to an improved water source is universal in Japan. About 98% of the population receives piped water supply from public utilities.[214]

Demographics

Japan has a population of 125.4 million, of which 122.8 million are Japanese nationals (2021 estimates).[215] A small population of foreign residents makes up the remainder.[216] In 2019, 92% of the total Japanese population lived in cities.[217] The capital city Tokyo has a population of 13.9 million (2022).[218] It is part of the Greater Tokyo Area, the biggest metropolitan area in the world with 38,140,000 people (2016).[219] Japan is an ethnically and culturally homogeneous society,[220] the Japanese people form 98.1% of the country’s population.[221] Minority ethnic groups in the country include the indigenous Ainu and Ryukyuan people.[222] Zainichi Koreans,[223] Chinese,[224] Filipinos,[225] Brazilians mostly of Japanese descent,[226] and Peruvians mostly of Japanese descent are also among Japan’s small minority groups.[227] Burakumin make up a social minority group.[228]

Japan is the world’s fastest aging country and has the highest proportion of elderly citizens of any country, comprising one-third of its total population;[229] this is the result of a post–World War II baby boom, which was followed by an increase in life expectancy and a decrease in birth rates.[230] Japan has a total fertility rate of 1.4, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1, and is among the world’s lowest;[231] it has a median age of 48.4, the highest in the world.[232] As of 2020, over 28.7 percent of the population is over 65, or one in four out of the Japanese population.[229] As a growing number of younger Japanese are not marrying or remaining childless,[233][234] Japan’s population is expected to drop to around 88 million by 2065.[229]

The changes in demographic structure have created several social issues, particularly a decline in the workforce population and an increase in the cost of social security benefits.[233] The government of Japan projects that there will be almost one elderly person for each person of working age by 2060.[232] Immigration and birth incentives are sometimes suggested as a solution to provide younger workers to support the nation’s aging population.[235][236] On April 1, 2019, Japan’s revised immigration law was enacted, protecting the rights of foreign workers to help reduce labor shortages in certain sectors.[237]

Largest cities or towns in Japan 2015 Census |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Prefecture | Pop. | Rank | Name | Prefecture | Pop. |

| 1 | Tokyo | Tokyo | 9,272,740 | 11 | Hiroshima | Hiroshima | 1,194,034 |

| 2 | Yokohama | Kanagawa | 3,724,844 | 12 | Sendai | Miyagi | 1,082,159 |

| 3 | Osaka | Osaka | 2,691,185 | 13 | Chiba | Chiba | 971,882 |

| 4 | Nagoya | Aichi | 2,295,638 | 14 | Kitakyushu | Fukuoka | 961,286 |

| 5 | Sapporo | Hokkaido | 1,952,356 | 15 | Sakai | Osaka | 839,310 |

| 6 | Fukuoka | Fukuoka | 1,538,681 | 16 | Niigata | Niigata | 810,157 |

| 7 | Kobe | Hyōgo | 1,537,272 | 17 | Hamamatsu | Shizuoka | 797,980 |

| 8 | Kawasaki | Kanagawa | 1,475,213 | 18 | Kumamoto | Kumamoto | 740,822 |

| 9 | Kyoto | Kyoto | 1,475,183 | 19 | Sagamihara | Kanagawa | 720,780 |

| 10 | Saitama | Saitama | 1,263,979 | 20 | Okayama | Okayama | 719,474 |

Religion

Japan’s constitution guarantees full religious freedom.[238] Upper estimates suggest that 84–96 percent of the Japanese population subscribe to Shinto as its indigenous religion.[239] However, these estimates are based on people affiliated with a temple, rather than the number of true believers. Many Japanese people practice both Shinto and Buddhism; they can either identify with both religions or describe themselves as non-religious or spiritual.[240] The level of participation in religious ceremonies as a cultural tradition remains high, especially during festivals and occasions such as the first shrine visit of the New Year.[241] Taoism and Confucianism from China have also influenced Japanese beliefs and customs.[242]

Christianity was first introduced into Japan by Jesuit missions starting in 1549. Today, 1%[243] to 1.5% of the population are Christians.[244] Throughout the latest century, Western customs originally related to Christianity (including Western style weddings, Valentine’s Day and Christmas) have become popular as secular customs among many Japanese.[245]

About 90% of those practicing Islam in Japan are foreign-born migrants as of 2016.[246] As of 2018 there were an estimated 105 mosques and 200,000 Muslims in Japan, 43,000 of which were Japanese nationals.[247] Other minority religions include Hinduism, Judaism, and Baháʼí Faith, as well as the animist beliefs of the Ainu.[248]

Languages

The Japanese language is Japan’s de facto national language and the primary written and spoken language of most people in the country.[249] Japanese writing uses kanji (Chinese characters) and two sets of kana (syllabaries based on cursive script and radicals used by kanji), as well as the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals.[250] English has taken a major role in Japan as a business and international link language. As a result, the prevalence of English in the educational system has increased, with English classes becoming mandatory at all levels of the Japanese school system by 2020.[249] Japanese Sign Language is the primary sign language used in Japan and has gained some official recognition, but its usage has been historically hindered by discriminatory policies and a lack of educational support.[249]

Besides Japanese, the Ryukyuan languages (Amami, Kunigami, Okinawan, Miyako, Yaeyama, Yonaguni), part of the Japonic language family, are spoken in the Ryukyu Islands chain.[251] Few children learn these languages,[252] but local governments have sought to increase awareness of the traditional languages.[253] The Ainu language, which is a language isolate, is moribund, with only a few native speakers remaining as of 2014.[254] Additionally, a number of other languages are taught and used by ethnic minorities, immigrant communities, and a growing number of foreign-language students, such as Korean (including a distinct Zainichi Korean dialect), Chinese and Portuguese.[249]

Education

Since the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education, compulsory education in Japan comprises elementary and junior high school, which together last for nine years.[255] Almost all children continue their education at a three-year senior high school.[256] The two top-ranking universities in Japan are the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University.[257] Starting in April 2016, various schools began the academic year with elementary school and junior high school integrated into one nine-year compulsory schooling program; MEXT plans for this approach to be adopted nationwide.[258]

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) coordinated by the OECD ranks the knowledge and skills of Japanese 15-year-olds as the third best in the world.[259] Japan is one of the top-performing OECD countries in reading literacy, math and sciences with the average student scoring 520 and has one of the world’s highest-educated labor forces among OECD countries.[260][259][261] It spent roughly 3.1% of its total GDP on education as of 2018,[262] below the OECD average of 4.9%.[263] In 2021, the country ranked third for the percentage of 25 to 64-year-olds that have attained tertiary education with 55.6%.[264] Approximately 65% of Japanese aged 25 to 34 have some form of tertiary education qualification, and bachelor’s degrees are held by 34.2% of Japanese aged 25 to 64, the second most in the OECD after South Korea.[264] In 2020, the share of women among tertiary programmes graduates was 51,8%.[264]

Health

Health care in Japan is provided by national and local governments. Payment for personal medical services is offered through a universal health insurance system that provides relative equality of access, with fees set by a government committee. People without insurance through employers can participate in a national health insurance program administered by local governments.[265] Since 1973, all elderly persons have been covered by government-sponsored insurance.[266]

Japan spent 10.74% of its total GDP on healthcare in 2019.[267] In 2020, the overall life expectancy in Japan at birth was 84.62 years (81.64 years for males and 87.74 years for females), the highest in the world;[268] while it had a very low infant mortality rate (2 per 1,000 live births).[269] Since 1981, the principal cause of death in Japan is cancer, which accounted for 27% of the total deaths in 2018—followed by cardiovascular diseases, which led to 15% of the deaths.[270] Japan has one of the world’s highest suicide rates, which is considered a major social issue.[271] Another significant public health issue is smoking among Japanese men.[272] However, Japan has the lowest rate of heart disease in the OECD, and the lowest level of dementia among developed countries.[273]

Culture

Contemporary Japanese culture combines influences from Asia, Europe, and North America.[274] Traditional Japanese arts include crafts such as ceramics, textiles, lacquerware, swords and dolls; performances of bunraku, kabuki, noh, dance, and rakugo; and other practices, the tea ceremony, ikebana, martial arts, calligraphy, origami, onsen, Geisha and games. Japan has a developed system for the protection and promotion of both tangible and intangible Cultural Properties and National Treasures.[275] Twenty-two sites have been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, eighteen of which are of cultural significance.[102] Japan is considered a cultural superpower.[276][277] The culture of Japan has left a lasting impact within global cultural flows, across numerous arts and media industries;[278][279][280] in genres and lifestyles as diverse as abstract art,[281] Christian media,[282] electronic dance music,[283] science fiction,[284] and Westerns.[285]

Art and architecture

The history of Japanese painting exhibits synthesis and competition between native Japanese esthetics and imported ideas.[286] The interaction between Japanese and European art has been significant: for example ukiyo-e prints, which began to be exported in the 19th century in the movement known as Japonism, had a significant influence on the development of modern art in the West, most notably on post-Impressionism.[286]

Japanese architecture is a combination of local and other influences. It has traditionally been typified by wooden or mud plaster structures, elevated slightly off the ground, with tiled or thatched roofs.[287] The Shrines of Ise have been celebrated as the prototype of Japanese architecture.[288] Traditional housing and many temple buildings see the use of tatami mats and sliding doors that break down the distinction between rooms and indoor and outdoor space.[289] Since the 19th century, Japan has incorporated much of Western modern architecture into construction and design.[290] It was not until after World War II that Japanese architects made an impression on the international scene, firstly with the work of architects like Kenzō Tange and then with movements like Metabolism.[291]

Literature and philosophy

The earliest works of Japanese literature include the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki chronicles and the Man’yōshū poetry anthology, all from the 8th century and written in Chinese characters.[292][293] In the early Heian period, the system of phonograms known as kana (hiragana and katakana) was developed.[294] The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter is considered the oldest extant Japanese narrative.[295] An account of court life is given in The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, while The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu is often described as the world’s first novel.[296][297]

During the Edo period, the chōnin («townspeople») overtook the samurai aristocracy as producers and consumers of literature. The popularity of the works of Saikaku, for example, reveals this change in readership and authorship, while Bashō revivified the poetic tradition of the Kokinshū with his haikai (haiku) and wrote the poetic travelogue Oku no Hosomichi.[298] The Meiji era saw the decline of traditional literary forms as Japanese literature integrated Western influences. Natsume Sōseki and Mori Ōgai were significant novelists in the early 20th century, followed by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, Kafū Nagai and, more recently, Haruki Murakami and Kenji Nakagami. Japan has two Nobel Prize-winning authors – Yasunari Kawabata (1968) and Kenzaburō Ōe (1994).[299]

Japanese philosophy has historically been a fusion of both foreign, particularly Chinese and Western, and uniquely Japanese elements. In its literary forms, Japanese philosophy began about fourteen centuries ago. Confucian ideals remain evident in the Japanese concept of society and the self, and in the organization of the government and the structure of society.[300] Buddhism has profoundly impacted Japanese psychology, metaphysics, and esthetics.[301]

Performing arts

Noh performance at a Shinto shrine

Japanese music is eclectic and diverse. Many instruments, such as the koto, were introduced in the 9th and 10th centuries. The popular folk music, with the guitar-like shamisen, dates from the 16th century.[302] Western classical music, introduced in the late 19th century, forms an integral part of Japanese culture.[303] Kumi-daiko (ensemble drumming) was developed in postwar Japan and became very popular in North America.[304] Popular music in post-war Japan has been heavily influenced by American and European trends, which has led to the evolution of J-pop.[305] Karaoke is a significant cultural activity.[306]

The four traditional theaters from Japan are noh, kyōgen, kabuki, and bunraku.[307] Noh is one of the oldest continuous theater traditions in the world.[308]

Holidays

Officially, Japan has 16 national, government-recognized holidays. Public holidays in Japan are regulated by the Public Holiday Law (国民の祝日に関する法律, Kokumin no Shukujitsu ni Kansuru Hōritsu) of 1948.[309] Beginning in 2000, Japan implemented the Happy Monday System, which moved a number of national holidays to Monday in order to obtain a long weekend.[310] The national holidays in Japan are New Year’s Day on January 1, Coming of Age Day on the second Monday of January, National Foundation Day on February 11, The Emperor’s Birthday on February 23, Vernal Equinox Day on March 20 or 21, Shōwa Day on April 29, Constitution Memorial Day on May 3, Greenery Day on May 4, Children’s Day on May 5, Marine Day on the third Monday of July, Mountain Day on August 11, Respect for the Aged Day on the third Monday of September, Autumnal Equinox on September 23 or 24, Health and Sports Day on the second Monday of October, Culture Day on November 3, and Labor Thanksgiving Day on November 23.[311]

Cuisine

Japanese cuisine offers a vast array of regional specialties that use traditional recipes and local ingredients.[312] Seafood and Japanese rice or noodles are traditional staples.[313] Japanese curry, since its introduction to Japan from British India, is so widely consumed that it can be termed a national dish, alongside ramen and sushi.[314][315] Traditional Japanese sweets are known as wagashi.[316] Ingredients such as red bean paste and mochi are used. More modern-day tastes include green tea ice cream.[317]

Popular Japanese beverages include sake, which is a brewed rice beverage that typically contains 14–17% alcohol and is made by multiple fermentation of rice.[318] Beer has been brewed in Japan since the late 17th century.[319] Green tea is produced in Japan and prepared in forms such as matcha, used in the Japanese tea ceremony.[320]

Media

According to the 2015 NHK survey on television viewing in Japan, 79 percent of Japanese watch television daily.[321] Japanese television dramas are viewed both within Japan and internationally;[322] other popular shows are in the genres of variety shows, comedy, and news programs.[323] Many Japanese media franchises such as Dragon Ball, One Piece, and Naruto have gained considerable global popularity and are among the world’s highest-grossing media franchises. Pokémon in particular is estimated to be the highest-grossing media franchise of all time. Japanese newspapers are among the most circulated in the world as of 2016.[324]

Japan has one of the oldest and largest film industries globally.[325] Ishirō Honda’s Godzilla became an international icon of Japan and spawned an entire subgenre of kaiju films, as well as the longest-running film franchise in history.[326][327] Japanese comics, known as manga, developed in the mid-20th century and have become popular worldwide.[328][329] A large number of manga series have become some of the best-selling comics series of all time, rivalling the American comics industry.[330] Japanese animated films and television series, known as anime, were largely influenced by Japanese manga and have become highly popular internationally.[331][332]

Sports

Sumo wrestlers form around the referee during the ring-entering ceremony.

Traditionally, sumo is considered Japan’s national sport.[333] Japanese martial arts such as judo and kendo are taught as part of the compulsory junior high school curriculum.[334] Baseball is the most popular spectator sport in the country.[335] Japan’s top professional league, Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB), was established in 1936.[336] Since the establishment of the Japan Professional Football League (J.League) in 1992, association football gained a wide following.[337] The country co-hosted the 2002 FIFA World Cup with South Korea.[338] Japan has one of the most successful football teams in Asia, winning the Asian Cup four times,[339] and the FIFA Women’s World Cup in 2011.[340] Golf is also popular in Japan.[341]

In motorsport, Japanese automotive manufacturers have been successful in multiple different categories, with titles and victories in series such as Formula One, MotoGP, and the World Rally Championship.[342][343][344] Drivers from Japan have victories at the Indianapolis 500 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans as well as podium finishes in Formula One, in addition to success in domestic championships.[345][346] Super GT is the most popular national racing series in Japan, while Super Formula is the top-level domestic open-wheel series.[347] The country hosts major races such as the Japanese Grand Prix.[348]

Japan hosted the Summer Olympics in Tokyo in 1964 and the Winter Olympics in Sapporo in 1972 and Nagano in 1998.[349] The country hosted the official 2006 Basketball World Championship[350] and will co-host the 2023 Basketball World Championship.[351] Tokyo hosted the 2020 Summer Olympics in 2021, making Tokyo the first Asian city to host the Olympics twice.[352] The country gained the hosting rights for the official Women’s Volleyball World Championship on five occasions, more than any other nation.[353] Japan is the most successful Asian Rugby Union country[354] and hosted the 2019 IRB Rugby World Cup.[355]

See also

- Index of Japan-related articles

- Outline of Japan

Notes

References

- ^ a b 令和元年全国都道府県市区町村別面積調 (10月1日時点) [Reiwa 1 nationwide area survey by prefectures and municipalities (as of October 1)] (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. December 26, 2019. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020.

- ^ «Surface water and surface water change». OECD. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ «Population Estimates by Age (Five-Year Groups) and Sex». Statistics Bureau of Japan. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ «2020 Population Census Preliminary Tabulation». Statistics Bureau of Japan. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d «World Economic Outlook database: April 2023». International Monetary Fund. October 2022.

- ^ Inequality — Income inequality — OECD Data. OECD. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ «Human Development Report 2021/2022» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. September 8, 2022.

- ^ «Official Names of Member States (UNTERM)» (PDF). UN Protocol and Liaison Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Schreiber, Mark (November 26, 2019). «You say ‘Nihon,’ I say ‘Nippon,’ or let’s call the whole thing ‘Japan’?». The Japan Times.

- ^ a b Carr, Michael (March 1992). «Wa Wa Lexicography». International Journal of Lexicography. 5 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1093/ijl/5.1.1 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Piggott, Joan R. (1997). The Emergence of Japanese Kingship. Stanford University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8047-2832-4.

- ^ Hoffman, Michael (July 27, 2008). «Cipangu’s landlocked isles». The Japan Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018.

- ^ Lach, Donald (2010). Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. I. University of Chicago Press. p. 157.

- ^ Mancall, Peter C. (2006). «Of the Ilande of Giapan, 1565». Travel Narratives from the Age of Discovery: an anthology. Oxford University Press. pp. 156–157.

- ^ Batchelor, Robert K. (2014). London: The Selden Map and the Making of a Global City, 1549–1689. University of Chicago Press. pp. 76, 79. ISBN 978-0-226-08079-6.

- ^ Ono, Akira; Sato, Hiroyuki; Tsutsumi, Takashi; Kudo, Yuichiro (2002). «Radiocarbon Dates and Archaeology of the Late Pleistocene in the Japanese Islands». Radiocarbon. 44 (2): 477–494. doi:10.1017/S0033822200031854.

- ^ Habu, Junko (2004). Ancient Jomon of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-77670-7.

- ^ «Jōmon Culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 B.C.)». Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (May 4, 2011). «Finding on Dialects Casts New Light on the Origins of the Japanese People». The New York Times.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2017). «Origins of the Japanese Language». Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.277. ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5.

- ^ a b Watanabe, Yusuke; Naka, Izumi; Khor, Seik-Soon; Sawai, Hiromi; Hitomi, Yuki; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Ohashi, Jun (June 17, 2019). «Analysis of whole Y-chromosome sequences reveals the Japanese population history in the Jomon period». Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 8556. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44473-z. PMC 6572846. PMID 31209235.

- ^ «Road of rice plant». National Science Museum of Japan. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ «Kofun Period (ca. 300–710)». Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ «Yayoi Culture (ca. 300 B.C.–300 A.D.)». Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Hendry, Joy (2012). Understanding Japanese Society. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-136-27918-8.

- ^ Brown, Delmer M.; Hall, John Whitney; Jansen, Marius B.; Shively, Donald H.; Twitchett, Denis (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–149, 275. ISBN 978-0-521-22352-2.

- ^ Beasley, William Gerald (1999). The Japanese Experience: A Short History of Japan. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-22560-2.

- ^ a b Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan: 1334–1615. Stanford University Press. pp. 57, 68. ISBN 978-0-8047-0525-7.

- ^ a b Totman, Conrad (2002). A History of Japan. Blackwell. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (2002). A History of Japan. Blackwell. pp. 64–79. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Henshall, Kenneth (2012). «Of Courtiers and Warriors: Early and Medieval History (710–1600)». A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 24–52. ISBN 978-0-230-36918-4.

- ^ Hays, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and pandemics: their impacts on human history. ABC-CLIO. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-85109-658-9.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (2002). A History of Japan. Blackwell. pp. 79–87, 122–123. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ Leibo, Steven A. (2015). East and Southeast Asia 2015–2016. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 99–104. ISBN 978-1-4758-1875-8.

- ^ Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. p. 616.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (2005). A History of Japan (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 106–112. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ Shirane, Haruo (2012). Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600. Columbia University Press. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-231-15730-8.

- ^ Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan: 1334–1615. Stanford University Press. pp. 42, 217. ISBN 978-0-8047-0525-7.

- ^ Lidin, Olof (2005). Tanegashima. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-203-47957-2.

- ^ Brown, Delmer (May 1948). «The impact of firearms on Japanese warfare, 1543–98». The Far Eastern Quarterly. 7 (3): 236–253. doi:10.2307/2048846. JSTOR 2048846.

- ^ «Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1603)». Dallas Museum of Art. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2011). Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Osprey Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84603-960-7.

- ^ a b c d e Henshall, Kenneth (2012). «The Closed Country: the Tokugawa Period (1600–1868)». A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 53–74. ISBN 978-0-230-36918-4.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (2005). A History of Japan (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ Toby, Ronald P. (1977). «Reopening the Question of Sakoku: Diplomacy in the Legitimation of the Tokugawa Bakufu». Journal of Japanese Studies. 3 (2): 323–363. doi:10.2307/132115. JSTOR 132115.

- ^ Howe, Christopher (1996). The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy. Hurst & Company. pp. 58ff. ISBN 978-1-85065-538-1.

- ^ Ohtsu, M.; Imanari, Tomio (1999). «Japanese National Values and Confucianism». Japanese Economy. 27 (2): 45–59. doi:10.2753/JES1097-203X270245.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (2005). A History of Japan (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 289–296. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ a b Henshall, Kenneth (2012). «Building a Modern Nation: the Meiji Period (1868–1912)». A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 75–107. ISBN 978-0-230-36918-4.

- ^ McCargo, Duncan (2000). Contemporary Japan. Macmillan. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-333-71000-5.

- ^ Baran, Paul (1962). The Political Economy of Growth. Monthly Review Press. p. 160.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (2005). A History of Japan (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 312–314. ISBN 978-1-4051-2359-4.

- ^ Matsusaka, Y. Tak (2009). «The Japanese Empire». In Tsutsui, William M. (ed.). Companion to Japanese History. Blackwell. pp. 224–241. ISBN 978-1-4051-1690-9.

- ^ Hiroshi, Shimizu; Hitoshi, Hirakawa (1999). Japan and Singapore in the world economy: Japan’s economic advance into Singapore, 1870–1965. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-415-19236-1.

- ^ a b c d e Henshall, Kenneth (2012). «The Excesses of Ambition: the Pacific War and its Lead-Up». A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 108–141. ISBN 978-0-230-36918-4.

- ^ Tsuzuki, Chushichi (2011). «Taisho Democracy and the First World War». The Pursuit of Power in Modern Japan 1825–1995. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198205890.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-820589-0.

- ^ a b Ramesh, S (2020). «The Taisho Period (1912–1926): Transition from Democracy to a Military Economy». China’s Economic Rise. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 173–209. ISBN 978-3-030-49811-5.

- ^ Burnett, M. Troy, ed. (2020). Nationalism Today: Extreme Political Movements around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 20.

- ^ Weber, Torsten (2018). Embracing ‘Asia’ in China and Japan. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 268.

- ^ «The Japanese Nation: It has a history of feudalism, nationalism, war and now defeat». LIFE. September 17, 1945. pp. 109–111.

- ^ Paine, S. C. M. (2012). The Wars for Asia, 1911–1949. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–125. ISBN 978-1-139-56087-0.

- ^ Worth, Roland H. Jr. (1995). No Choice But War: the United States Embargo Against Japan and the Eruption of War in the Pacific. McFarland. pp. 56, 86. ISBN 978-0-7864-0141-3.

- ^ Bailey, Beth; Farber, David (2019). «Introduction: December 7/8, 1941». Beyond Pearl Harbor: A Pacific History. University Press of Kansas. pp. 1–8.

- ^ Yōko, Hayashi (1999–2000). «Issues Surrounding the Wartime «Comfort Women»«. Review of Japanese Culture and Society. 11/12 (Special Issue): 54–65. JSTOR 42800182.

- ^ Pape, Robert A. (1993). «Why Japan Surrendered». International Security. 18 (2): 154–201. doi:10.2307/2539100. JSTOR 2539100.

- ^ Watt, Lori (2010). When Empire Comes Home: Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan. Harvard University Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-674-05598-8.

- ^ a b c d e Henshall, Kenneth (2012). «A Phoenix from the Ashes: Postwar Successes and Beyond». A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 142–180. ISBN 978-0-230-36918-4.

- ^ Coleman, Joseph (March 6, 2007). «’52 coup plot bid to rearm Japan: CIA». The Japan Times.

- ^ Saxonhouse, Gary; Stern, Robert (2003). «The bubble and the lost decade». The World Economy. 26 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1111/1467-9701.00522. hdl:2027.42/71597.

- ^ a b Fackler, Martin; Drew, Kevin (March 11, 2011). «Devastation as Tsunami Crashes Into Japan». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2022.

- ^ «Japan’s emperor thanks country, prays for peace before abdication». Nikkei Asian Review. April 30, 2019.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (February 16, 2023). «Japan sees its number of islands double after recount». The Guardian.

- ^ «Water Supply in Japan». Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ^ Iwashita, Akihiro (2011). «An Invitation to Japan’s Borderlands: At the Geopolitical Edge of the Eurasian Continent». Journal of Borderlands Studies. 26 (3): 279–282. doi:10.1080/08865655.2011.686969.

- ^ Kuwahara, Sueo (2012). «The development of small islands in Japan: An historical perspective». Journal of Marine and Island Cultures. 1 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.imic.2012.04.004.

- ^ McCargo, Duncan (2000). Contemporary Japan. Macmillan. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-0-333-71000-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g «World Factbook: Japan». CIA. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Yamada, Yoshihiko (2011). «Japan’s New National Border Strategy and Maritime Security». Journal of Borderlands Studies. 26 (3): 357–367. doi:10.1080/08865655.2011.686972.

- ^ «Natural environment of Japan: Japanese archipelago». Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ Fujimoto, Shouji; Mizuno, Takayuki; Ohnishi, Takaaki; Shimizu, Chihiro; Watanabe, Tsutomu (2017). «Relationship between population density and population movement in inhabitable lands». Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review. 14: 117–130. doi:10.1007/s40844-016-0064-z.

- ^ «List of countries by population density». Statistics Times. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Fujimoto, Shouji; Mizuno, Takayuki; Ohnishi, Takaaki; Shimizu, Chihiro; Watanabe, Tsutomu (2014). «Geographic Dependency of Population Distribution». Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Modeling and Simulation, Plus Econophysics Colloquium. Springer Proceedings in Complexity: 151–162. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20591-5_14. ISBN 978-3-319-20590-8.

- ^ 総務省|住基ネット [Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Resident Registration net]. soumu.go.jp. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ Hua, Yang (2014). «Legal Regulation of Land Reclamation in China’s Coastal Areas». Coastal Management. 42 (1): 59–79. doi:10.1080/08920753.2013.865008.

- ^ Tabata, Ryoichi; Kakioka, Ryo; Tominaga, Koji; Komiya, Takefumi; Watanabe, Katsutoshi (2016). «Phylogeny and historical demography of endemic fishes in Lake Biwa: The ancient lake as a promoter of evolution and diversification of freshwater fishes in western Japan». Ecology and Evolution. 6 (8): 2601–2623. doi:10.1002/ece3.2070. PMC 4798153. PMID 27066244.

- ^ Israel, Brett (March 14, 2011). «Japan’s Explosive Geology Explained». Live Science.

- ^ «World Risk Report 2016». UNU-EHS. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Fujita, Eisuke; Ueda, Hideki; Nakada, Setsuya (July 2020). «A New Japan Volcanological Database». Frontiers in Earth Science. 8: 205. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.00205.

- ^ «Tectonics and Volcanoes of Japan». Oregon State University. Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Hammer, Joshua (May 2011). «The Great Japan Earthquake of 1923». Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ a b c Karan, Pradyumna Prasad; Gilbreath, Dick (2005). Japan in the 21st century. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 18–21, 41. ISBN 978-0-8131-2342-4.

- ^ «Climate of Hokuriku district». Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ «Overview of Japan’s climate». Japan Meteorological Association. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Ito, Masami. «Japan 2030: Tackling climate issues is key to the next decade». The Japan Times. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ «Record High in Japan as Heat Wave Grips the Region». The New York Times. Associated Press. July 23, 2018. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018.

- ^ Ogura, Junko; Regan, Helen (August 18, 2020). «Japan’s heat wave continues, as temperatures equal highest record». CNN.

- ^ «Flora and Fauna: Diversity and regional uniqueness». Embassy of Japan in the USA. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ Sakurai, Ryo (2019). Human Dimensions of Wildlife Management in Japan: From Asia to the World. Springer. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-981-13-6332-0.

- ^ «The Wildlife in Japan» (PDF). Ministry of the Environment. March 2015.

- ^ «National Parks of Japan». Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ^ «Japan». Ramsar. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ a b «Japan – Properties Inscribed on the World Heritage List». UNESCO. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ 日本の大気汚染の歴史 [Historical Air Pollution in Japan] (in Japanese). Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Sekiyama, Takeshi. «Japan’s international cooperation for energy efficiency and conservation in Asian region» (PDF). Energy Conservation Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ «Environmental Performance Index: Japan». Yale University. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ «Japan sees extra emission cuts to 2020 goal – minister». Reuters. June 24, 2009.

- ^ Davidson, Jordan (October 26, 2020). «Japan Targets Carbon Neutrality by 2050». Ecowatch.

- ^ «Environmental Performance Review of Japan» (PDF). OECD. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c d «Japan’s Parliament and other political institutions». European Parliament. June 9, 2020.

- ^ a b «The Constitution of Japan». Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. November 3, 1946. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f «Japan». US Securities and Exchange Commission. August 6, 2020.

- ^ «Japan Youth Can Make Difference with New Voting Rights: UN Envoy». UN Envoy on Youth. July 2016.

- ^ «Fumio Kishida wins race to become Japan’s next prime minister». BBC News. September 29, 2021.

- ^ Crespo, José Antonio (April 1995). «The Liberal Democratic Party in Japan: Conservative Domination». International Political Science Review. 16 (2): 199–209. JSTOR 1601459.

- ^ a b Dean, Meryll (2002). Japanese legal system: text, cases & materials (2nd ed.). Cavendish. pp. 55–58, 131. ISBN 978-1-85941-673-0.

- ^ Kanamori, Shigenari (January 1, 1999). «German influences on Japanese Pre-War Constitution and Civil Code». European Journal of Law and Economics. 7 (1): 93–95. doi:10.1023/A:1008688209052.

- ^ «The Anomalous Life of the Japanese Constitution». Nippon.com. August 15, 2017. Archived from the original on August 11, 2019.

- ^ «The Japanese Judicial System». Office of the Prime Minister of Japan. July 1999.

- ^ «Regions of Japan» (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ «Japan’s Efforts at the United Nations (UN)». Diplomatic Bluebook 2017. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Terada, Takashi (2011). «The United States and East Asian Regionalism». In Borthwick, Mark; Yamamoto, Tadashi (eds.). A Pacific Nation (PDF). ISBN 978-4-88907-133-7.

- ^ «Statistics from the Development Co-operation Report 2015». OECD. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ «Global Diplomacy Index – Country Rank». Lowy Institute. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ a b «US Relations with Japan». US Department of State. January 21, 2020.

- ^ Chanlett-Avery, Emma (2018). Japan, the Indo-Pacific, and the «Quad» (Report). Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

- ^ Smith, Sheila A. (May 27, 2021). «The Quad in the Indo-Pacific: What to Know». Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ «Japan and South Korea agree WW2 ‘comfort women’ deal». BBC News. December 28, 2015.

- ^ Ju, H. (July 2018). «The Korean Wave and Korean Dramas». Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.715. ISBN 9780190228613.

- ^ Min-sik, Yoon (August 14, 2019). «21 years after ‘Japanese invasion,’ Korean pop culture stronger than ever». The Korean Herald.

- ^ «Japanese Territory, Northern Territories». MOFA. April 4, 2014.

- ^ «Japanese Territory, Takeshima». MOFA. July 30, 2014.

- ^ Fox, Senan (September 2016). «The Senkaku Shoto/Diaoyu Islands and Okinotorishima disputes: Ideational and material influences». China Information. 30 (3): 312–333. doi:10.1177/0920203X16665778.

- ^ «Global Peace Index 2022» (PDF). Institute for Economics & Peace. June 2022. pp. 10–11.

- ^ «Military expenditure (% of GDP) — Japan». World Bank.

- ^ Tian, Nan; Fleurant, Aude; Kuimova, Alexandra; Wezeman, Pieter D.; Wezeman, Siemon T. (April 24, 2022). «Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2021» (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- ^ «Japan: Article 9 of the Constitution». Library of Congress. February 2006.

- ^ Teslik, Lee Hudson (April 13, 2006). «Japan and its military». Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ «Japan’s Security Policy». Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. April 6, 2016.

- ^ «Abe offers Japan’s help in maintaining regional security». Japan Herald. May 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014.

- ^ Yoji, Koda (September 18, 2020). «Japan: Dealing with North Korea’s Growing Missile Threat». The Diplomat.

- ^ Gale, Alastair; Tsuneoka, Chieko (July 14, 2020). «China Provocations Hasten Japan’s Military Revival». The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ «Who will conduct the investigation?». Supreme Court of Japan. 2005. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ National Police Agency Police History Compilation Committee, ed. (1977). Japan post-war police history (in Japanese). Japan Police Support Association.

- ^ «Chapter IV. Maintenance of Public Safety and Disaster Countermeasures» (PDF). Japanese National Police Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 23, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ «Japan Coast Guard» (PDF). Japan Coast Guard. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ «Diet tightens laws on knives, guns». The Japan Times. November 29, 2008.

- ^ Fisher, Max (July 23, 2012). «A Land Without Guns: How Japan Has Virtually Eliminated Shooting Deaths». The Atlantic.

- ^ «Victims of intentional homicide, 1990–2018». UNODC. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ «Kidnapping: 2018». UNODC. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ «Sexual violence». UNODC. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ «Robbery: 2018». UNODC. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ «Unemployment, total (% of the total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate): Japan». World Bank. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Komiya, Kantaro; Kihara, Leiha (October 31, 2021). «Japan confronts rising inequality after Abenomics». Reuters.

- ^ Huang, Eustance (July 2, 2020). «Japan’s middle class is ‘disappearing’ as poverty rises, warns economist». CNBC.

- ^ Ímrohoroğlu, Selahattin; Kitao, Sagiri; Yamada, Tomoaki (February 2016). «Achieving fiscal balance in Japan». International Economic Review. 57 (1): 117–154. JSTOR 44075341.

- ^ «Monetary Tightening Poses Medium-Term Risks to Japan’s Debt Dynamics». Fitch Ratings. May 6, 2022.

- ^ «Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserve». IMF. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ «List of importing markets for the product exported by Japan in 2021». International Trade Centre. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ «List of supplying markets for the product imported by Japan in 2021». International Trade Centre. Retrieved August 10, 2022.