From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers’ or writers’ composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domains such as phonology, morphology, and syntax, often complemented by phonetics, semantics, and pragmatics. There are currently two different approaches to the study of grammar: traditional grammar and theoretical grammar.

Fluent speakers of a language variety or lect have effectively internalized these constraints,[1] the vast majority of which – at least in the case of one’s native language(s) – are acquired not by conscious study or instruction but by hearing other speakers. Much of this internalization occurs during early childhood; learning a language later in life usually involves more explicit instruction.[2] In this view, grammar is understood as the cognitive information underlying a specific instance of language production.

The term «grammar» can also describe the linguistic behavior of groups of speakers and writers rather than individuals. Differences in scales are important to this sense of the word: for example, the term «English grammar» could refer to the whole of English grammar (that is, to the grammar of all the speakers of the language), in which case the term encompasses a great deal of variation.[3] At a smaller scale, it may refer only to what is shared among the grammars of all or most English speakers (such as subject–verb–object word order in simple declarative sentences). At the smallest scale, this sense of «grammar» can describe the conventions of just one relatively well-defined form of English (such as standard English for a region).

A description, study, or analysis of such rules may also be referred to as grammar. A reference book describing the grammar of a language is called a «reference grammar» or simply «a grammar» (see History of English grammars). A fully explicit grammar, which exhaustively describes the grammatical constructions of a particular speech variety, is called descriptive grammar. This kind of linguistic description contrasts with linguistic prescription, an attempt to actively discourage or suppress some grammatical constructions while codifying and promoting others, either in an absolute sense or about a standard variety. For example, some prescriptivists maintain that sentences in English should not end with prepositions, a prohibition that has been traced to John Dryden (13 April 1668 – January 1688) whose unexplained objection to the practice perhaps led other English speakers to avoid the construction and discourage its use.[4][5] Yet preposition stranding has a long history in Germanic languages like English, where it is so widespread as to be a standard usage.

Outside linguistics, the term grammar is often used in a rather different sense. It may be used more broadly to include conventions of spelling and punctuation, which linguists would not typically consider as part of grammar but rather as part of orthography, the conventions used for writing a language. It may also be used more narrowly to refer to a set of prescriptive norms only, excluding those aspects of a language’s grammar which are not subject to variation or debate on their normative acceptability. Jeremy Butterfield claimed that, for non-linguists, «Grammar is often a generic way of referring to any aspect of English that people object to.»[6]

Etymology[edit]

The word grammar is derived from Greek γραμματικὴ τέχνη (grammatikḕ téchnē), which means «art of letters», from γράμμα (grámma), «letter», itself from γράφειν (gráphein), «to draw, to write».[7] The same Greek root also appears in the words graphics, grapheme, and photograph.

History[edit]

The first systematic grammar of Sanskrit, originated in Iron Age India, with Yaska (6th century BC), Pāṇini (6th–5th century BC[8]) and his commentators Pingala (c. 200 BC), Katyayana, and Patanjali (2nd century BC). Tolkāppiyam, the earliest Tamil grammar, is mostly dated to before the 5th century AD. The Babylonians also made some early attempts at language description.[9]

Grammar appeared as a discipline in Hellenism from the 3rd century BC forward with authors such as Rhyanus and Aristarchus of Samothrace. The oldest known grammar handbook is the Art of Grammar (Τέχνη Γραμματική), a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively, written by the ancient Greek scholar Dionysius Thrax (c. 170–c. 90 BC), a student of Aristarchus of Samothrace who founded a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax’s grammar book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century AD. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today.[10] Latin grammar developed by following Greek models from the 1st century BC, due to the work of authors such as Orbilius Pupillus, Remmius Palaemon, Marcus Valerius Probus, Verrius Flaccus, and Aemilius Asper.

The grammar of Irish originated in the 7th century with the Auraicept na n-Éces. Arabic grammar emerged with Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali in the 7th century. The first treatises on Hebrew grammar appeared in the High Middle Ages, in the context of Mishnah (exegesis of the Hebrew Bible). The Karaite tradition originated in Abbasid Baghdad. The Diqduq (10th century) is one of the earliest grammatical commentaries on the Hebrew Bible.[11] Ibn Barun in the 12th century, compares the Hebrew language with Arabic in the Islamic grammatical tradition.[12]

Belonging to the trivium of the seven liberal arts, grammar was taught as a core discipline throughout the Middle Ages, following the influence of authors from Late Antiquity, such as Priscian. Treatment of vernaculars began gradually during the High Middle Ages, with isolated works such as the First Grammatical Treatise, but became influential only in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In 1486, Antonio de Nebrija published Las introduciones Latinas contrapuesto el romance al Latin, and the first Spanish grammar, Gramática de la lengua castellana, in 1492. During the 16th-century Italian Renaissance, the Questione della lingua was the discussion on the status and ideal form of the Italian language, initiated by Dante’s de vulgari eloquentia (Pietro Bembo, Prose della volgar lingua Venice 1525). The first grammar of Slovene was written in 1583 by Adam Bohorič.

Grammars of some languages began to be compiled for the purposes of evangelism and Bible translation from the 16th century onward, such as Grammatica o Arte de la Lengua General de Los Indios de Los Reynos del Perú (1560), a Quechua grammar by Fray Domingo de Santo Tomás.

From the latter part of the 18th century, grammar came to be understood as a subfield of the emerging discipline of modern linguistics. The Deutsche Grammatik of the Jacob Grimm was first published in the 1810s. The Comparative Grammar of Franz Bopp, the starting point of modern comparative linguistics, came out in 1833.

Theoretical frameworks[edit]

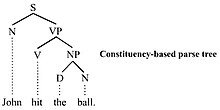

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object. This is in contrast to structural and functional grammar which consider the subject and object as equal constituents.[13][14]

Frameworks of grammar which seek to give a precise scientific theory of the syntactic rules of grammar and their function have been developed in theoretical linguistics.

- Dependency grammar: dependency relation (Lucien Tesnière 1959)

- Link grammar

- Functional grammar (structural–functional analysis):

- Danish Functionalism

- Functional Discourse Grammar

- Role and reference grammar

- Systemic functional grammar

- Montague grammar

Other frameworks are based on an innate «universal grammar», an idea developed by Noam Chomsky. In such models, the object is placed into the verb phrase. The most prominent biologically-oriented theories are:

- Cognitive grammar / Cognitive linguistics

- Construction grammar

- Fluid Construction Grammar

- Word grammar

- Construction grammar

- Generative grammar:

- Transformational grammar (1960s)

- Generative semantics (1970s) and Semantic Syntax (1990s)

- Phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar (1985)

- Principles and parameters grammar (Government and binding theory) (1980s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Lexical functional grammar

- Categorial grammar (lambda calculus)

- Minimalist program-based grammar (1993)

- Stochastic grammar: probabilistic

- Operator grammar

Parse trees are commonly used by such frameworks to depict their rules. There are various alternative schemes for some grammar:

- Affix grammar over a finite lattice

- Backus–Naur form

- Constraint grammar

- Lambda calculus

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- X-bar theory

Development of grammar[edit]

Grammars evolve through usage. Historically, with the advent of written representations, formal rules about language usage tend to appear also, although such rules tend to describe writing conventions more accurately than conventions of speech.[15] Formal grammars are codifications of usage which are developed by repeated documentation and observation over time. As rules are established and developed, the prescriptive concept of grammatical correctness can arise. This often produces a discrepancy between contemporary usage and that which has been accepted, over time, as being standard or «correct». Linguists tend to view prescriptive grammar as having little justification beyond their authors’ aesthetic tastes, although style guides may give useful advice about standard language employment based on descriptions of usage in contemporary writings of the same language. Linguistic prescriptions also form part of the explanation for variation in speech, particularly variation in the speech of an individual speaker (for example, why some speakers say «I didn’t do nothing», some say «I didn’t do anything», and some say one or the other depending on social context).

The formal study of grammar is an important part of children’s schooling from a young age through advanced learning, though the rules taught in schools are not a «grammar» in the sense that most linguists use, particularly as they are prescriptive in intent rather than descriptive.

Constructed languages (also called planned languages or conlangs) are more common in the modern-day, although still extremely uncommon compared to natural languages. Many have been designed to aid human communication (for example, naturalistic Interlingua, schematic Esperanto, and the highly logic-compatible artificial language Lojban). Each of these languages has its own grammar.

Syntax refers to the linguistic structure above the word level (for example, how sentences are formed) – though without taking into account intonation, which is the domain of phonology. Morphology, by contrast, refers to the structure at and below the word level (for example, how compound words are formed), but above the level of individual sounds, which, like intonation, are in the domain of phonology.[16] However, no clear line can be drawn between syntax and morphology. Analytic languages use syntax to convey information that is encoded by inflection in synthetic languages. In other words, word order is not significant, and morphology is highly significant in a purely synthetic language, whereas morphology is not significant and syntax is highly significant in an analytic language. For example, Chinese and Afrikaans are highly analytic, thus meaning is very context-dependent. (Both have some inflections, and both have had more in the past; thus, they are becoming even less synthetic and more «purely» analytic over time.) Latin, which is highly synthetic, uses affixes and inflections to convey the same information that Chinese does with syntax. Because Latin words are quite (though not totally) self-contained, an intelligible Latin sentence can be made from elements that are arranged almost arbitrarily. Latin has a complex affixation and simple syntax, whereas Chinese has the opposite.

Education[edit]

Prescriptive grammar is taught in primary and secondary school. The term «grammar school» historically referred to a school (attached to a cathedral or monastery) that teaches Latin grammar to future priests and monks. It originally referred to a school that taught students how to read, scan, interpret, and declaim Greek and Latin poets (including Homer, Virgil, Euripides, and others). These should not be mistaken for the related, albeit distinct, modern British grammar schools.

A standard language is a dialect that is promoted above other dialects in writing, education, and, broadly speaking, in the public sphere; it contrasts with vernacular dialects, which may be the objects of study in academic, descriptive linguistics but which are rarely taught prescriptively. The standardized «first language» taught in primary education may be subject to political controversy because it may sometimes establish a standard defining nationality or ethnicity.

Recently, efforts have begun to update grammar instruction in primary and secondary education. The main focus has been to prevent the use of outdated prescriptive rules in favor of setting norms based on earlier descriptive research and to change perceptions about the relative «correctness» of prescribed standard forms in comparison to non-standard dialects. A series of metastudies have found that the explicit teaching of grammatical parts of speech and syntax has little or no effect on the improvement of student writing quality in elementary school, middle school of high school; other methods of writing instruction had far greater positive effect, including strategy instruction, collaborative writing, summary writing, process instruction, sentence combining and inquiry projects.[17][18][19]

The preeminence of Parisian French has reigned largely unchallenged throughout the history of modern French literature. Standard Italian is based on the speech of Florence rather than the capital because of its influence on early literature. Likewise, standard Spanish is not based on the speech of Madrid but on that of educated speakers from more northern areas such as Castile and León (see Gramática de la lengua castellana). In Argentina and Uruguay the Spanish standard is based on the local dialects of Buenos Aires and Montevideo (Rioplatense Spanish). Portuguese has, for now, two official standards, respectively Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese.

The Serbian variant of Serbo-Croatian is likewise divided; Serbia and the Republika Srpska of Bosnia and Herzegovina use their own distinct normative subvarieties, with differences in yat reflexes. The existence and codification of a distinct Montenegrin standard is a matter of controversy, some treat Montenegrin as a separate standard lect, and some think that it should be considered another form of Serbian.

Norwegian has two standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk, the choice between which is subject to controversy: Each Norwegian municipality can either declare one as its official language or it can remain «language neutral». Nynorsk is backed by 27 percent of municipalities. The main language used in primary schools, chosen by referendum within the local school district, normally follows the official language of its municipality. Standard German emerged from the standardized chancellery use of High German in the 16th and 17th centuries. Until about 1800, it was almost exclusively a written language, but now it is so widely spoken that most of the former German dialects are nearly extinct.

Standard Chinese has official status as the standard spoken form of the Chinese language in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Republic of China (ROC), and the Republic of Singapore. Pronunciation of Standard Chinese is based on the local accent of Mandarin Chinese from Luanping, Chengde in Hebei Province near Beijing, while grammar and syntax are based on modern vernacular written Chinese.

Modern Standard Arabic is directly based on Classical Arabic, the language of the Qur’an. The Hindustani language has two standards, Hindi and Urdu.

In the United States, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar designated 4 March as National Grammar Day in 2008.[20]

See also[edit]

- Ambiguous grammar

- Constraint-based grammar

- Grammeme

- Harmonic Grammar

- Higher order grammar (HOG)

- Linguistic error

- Linguistic typology

- Paragrammatism

- Speech error (slip of the tongue)

- Usage (language)

- Usus

Notes[edit]

- ^ Traditionally, the mental information used to produce and process linguistic utterances is referred to as «rules». However, other frameworks employ different terminology, with theoretical implications. Optimality theory, for example, talks in terms of «constraints», while construction grammar, cognitive grammar, and other «usage-based» theories make reference to patterns, constructions, and «schemata»

- ^ O’Grady, William; Dobrovolsky, Michael; Katamba, Francis (1996). Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 4–7, 464–539. ISBN 978-0-582-24691-1. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Holmes, Janet (2001). An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (second ed.). Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 73–94. ISBN 978-0-582-32861-7. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.; for more discussion of sets of grammars as populations, see: Croft, William (2000). Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach. Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 13–20. ISBN 978-0-582-35677-1. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 2002, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, p. 627f.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (23 September 2007). «The Power of Prepositions». On Writing. Cairo: Criminal Brief. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Jeremy Butterfield, (2008). Damp Squid: The English Language Laid Bare, Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-957409-4. p. 142.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «Grammar». Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī («Eight Chapters»), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the 6th to 5th century BCE by the Indian grammarian Panini.

- ^ McGregor, William B. (2015). Linguistics: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-567-58352-9.

- ^ Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-300-09721-4. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ G. Khan, J. B. Noah, The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought (2000)

- ^ Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn’s Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (1964)

- ^ Schäfer, Roland (2016). Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen (2nd ed.). Berlin: Language Science Press. ISBN 978-1-537504-95-7. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Butler, Christopher S. (2003). Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1 (PDF). John Benjamins. pp. 121–124. ISBN 9781588113580. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Carter, Ronald; McCarthy, Michael (2017). «Spoken Grammar: Where are We and Where are We Going?». Applied Linguistics. 38: 1–20. doi:10.1093/applin/amu080.

- ^ Gussenhoven, Carlos; Jacobs, Haike (2005). Understanding Phonology (second ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-80735-4. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York.Washington, DC:Alliance for Excellent Education.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

- ^ Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 879–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029185

- ^ «National Grammar Day». Quick and Dirty Tips. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

References[edit]

- Rundle, Bede. Grammar in Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-19-824612-9.

External links[edit]

Look up grammar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Grammar from the Oxford English Dictionary

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). «Grammar» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grammar.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Grammar.

| Linguistics | |

| Comparative linguistics | |

| Computational linguistics | |

| Dialectology | |

| Etymology | |

| Historical linguistics | |

| Morphology | |

| Phonetics | |

| Phonology | |

| Psycholinguistics | |

| Semantics | |

| Synchronic linguistics | |

| Syntax | |

| Psycholinguistics | |

| Sociolinguistics | |

Grammar is the set of rules that allow a speaker to form an intelligible communication. In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers’ or writers’ composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domains such as phonology, morphology, and syntax, often complemented by phonetics, semantics, and pragmatics. There are currently two different approaches to the study of grammar: traditional grammar and theoretical grammar.

Etymology

The word grammar is derived from Greek γραμματικὴ τέχνη (grammatikḕ téchnē), which means «art of letters,» from γράμμα (grámma), «letter», itself from γράφειν (gráphein), «to draw, to write.»[1] The same Greek root also appears in the words graphics, grapheme, and photograph.

Definition

Grammar can refer to a range of concepts. For example, the term «English grammar» could refer to the whole of English grammar (that is, to the grammar of all the speakers of the language), in which case the term encompasses a great deal of variation.[2][3] At a smaller scale, it may refer only to what is shared among the grammars of all or most English speakers (such as subject–verb–object word order in simple declarative sentences). At the smallest scale, this sense of «grammar» can describe the conventions of just one relatively well-defined form of English (such as standard English for a region). The term «grammar» can also describe the linguistic behavior of groups of speakers and writers rather than individuals.

A description, study, or analysis of such rules may also be referred to as grammar. A reference book describing the grammar of a language is called a «reference grammar» or simply «a grammar» (see History of English grammars). A fully explicit grammar, which exhaustively describes the grammatical constructions of a particular speech variety, is called descriptive grammar. This kind of linguistic description contrasts with linguistic prescription, an attempt to actively discourage or suppress some grammatical constructions while codifying and promoting others, either in an absolute sense or about a standard variety.

One example is prescriptivists who maintain that sentences in English should not end with prepositions, a prohibition that has been traced to John Dryden (April 13 1668 – January 1688) whose unexplained objection to the practice perhaps led other English speakers to avoid the construction and discourage its use.[4][5] Yet preposition stranding has a long history in Germanic languages like English, where it is so widespread as to be a standard usage.

Fluent speakers of a language variety or lect have effectively internalized these constraints,[6] the vast majority of which – at least in the case of one’s native language(s) – are acquired not by conscious study or instruction but by hearing and mimicking other speakers. Much of this internalization occurs during early childhood. Learning a language later in life usually involves more explicit instruction.[7] On this view, grammar is understood as the cognitive information underlying a specific instance of language production.

Outside linguistics, the term grammar is often used in a rather different sense. It may be used more broadly to include conventions of spelling and punctuation, which linguists would not typically consider as part of grammar but rather as part of orthography, the conventions used for writing a language. It may also be used more narrowly to refer to a set of prescriptive norms only, excluding those aspects of a language’s grammar which are not subject to variation or debate on their normative acceptability. Jeremy Butterfield claimed that, for non-linguists, «Grammar is often a generic way of referring to any aspect of English that people object to.»[8]

History

The first systematic grammar of Sanskrit, originated in Iron Age India, with Yaska (sixth century B.C.E.), Pāṇini (sixth–fifth century B.C.E.[9]) and his commentators Pingala (c. 200 B.C.E.), Katyayana, and Patanjali (second century B.C.E.Tolkāppiyam, the earliest Tamil grammar, is mostly dated to before the fifth century C.E. The Babylonians also made some early attempts at language description.[10]

Grammar appeared as a discipline in Hellenism from the third century B.C.E. forward with authors such as Rhyanus and Aristarchus of Samothrace. The oldest known grammar handbook is the Art of Grammar (Τέχνη Γραμματική), a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively, written by the ancient Greek scholar Dionysius Thrax (c. 170–c. 90 B.C.E.), a student of Aristarchus of Samothrace who founded a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax’s grammar book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century C.E. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today.[11] Latin grammar developed by following Greek models from the first century B.C.E., due to the work of authors such as Orbilius Pupillus, Remmius Palaemon, Marcus Valerius Probus, Verrius Flaccus, and Aemilius Asper.

The grammar of Irish originated in the seventh century with the Auraicept na n-Éces. Arabic grammar emerged with Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali in the seventh century. The first treatises on Hebrew grammar appeared in the High Middle Ages, in the context of Mishnah (exegesis of the Hebrew Bible). The Karaite tradition originated in Abbasid Baghdad. The Diqduq (tenth century) is one of the earliest grammatical commentaries on the Hebrew Bible.[12] Ibn Barun in the twelfth century compares the Hebrew language with Arabic in the Islamic grammatical tradition.[13]

Belonging to the trivium of the seven liberal arts, grammar was taught as a core discipline throughout the Middle Ages, following the influence of authors from Late Antiquity, such as Priscian. Treatment of vernaculars began gradually during the High Middle Ages, with isolated works such as the First Grammatical Treatise, but became influential only in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In 1486, Antonio de Nebrija published Las introduciones Latinas contrapuesto el romance al Latin, and the first Spanish grammar, Gramática de la lengua castellana, in 1492. During the sixteenth-century Italian Renaissance, the Questione della lingua was the discussion on the status and ideal form of the Italian language, initiated by Dante’s de vulgari eloquentia (Pietro Bembo, Prose della volgar lingua Venice 1525). The first grammar of Slovene was written in 1583 by Adam Bohorič.

Grammars of some languages began to be compiled for the purposes of evangelism and Bible translation from the sixteenth century onward, such as Grammatica o Arte de la Lengua General de Los Indios de Los Reynos del Perú (1560), a Quechua grammar by Fray Domingo de Santo Tomás.

From the latter part of the eighteenth century, grammar came to be understood as a subfield of the emerging discipline of modern linguistics. The Deutsche Grammatik of Jacob Grimm was first published in the 1810s. The Comparative Grammar of Franz Bopp, the starting point of modern comparative linguistics, came out in 1833.

Theoretical frameworks

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object. This is in contrast to structural and functional grammar which consider the subject and object as equal constituents.[14][15]

Frameworks of grammar which seek to give a precise scientific theory of the syntactic rules of grammar and their function have been developed in theoretical linguistics.

- Dependency grammar: dependency relation (Lucien Tesnière 1959)

- Link grammar

- Functional grammar (structural–functional analysis):

- Danish Functionalism

- Functional Discourse Grammar

- Role and reference grammar

- Systemic functional grammar

- Montague grammar

Other frameworks are based on an innate «universal grammar», an idea developed by Noam Chomsky. In such models, the object is placed into the verb phrase. The most prominent biologically-oriented theories are:

- Cognitive grammar / Cognitive linguistics

- Construction grammar

- Fluid Construction Grammar

- Word grammar

- Construction grammar

- Generative grammar:

- Transformational grammar (1960s)

- Generative semantics (1970s) and Semantic Syntax (1990s)

- Generalized phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar (1985)

- Principles and parameters grammar (Government and binding theory) (1980s)

- Lexical functional grammar

- Categorial grammar (lambda calculus)

- Minimalist program-based grammar (1993)

- Stochastic grammar: probabilistic

- Operator grammar

Parse trees are commonly used by such frameworks to depict their rules. There are various alternative schemes for some grammar:

- Affix grammar over a finite lattice

- Backus–Naur form

- Constraint grammar

- Lambda calculus

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- X-bar theory

Development of grammar

Grammars change through usage. Historically, with the advent of written representations, formal rules about language usage also generally appear. Such rules describe writing conventions more accurately than conventions of speech.[16] Formal grammars are codifications of usage which are developed by repeated documentation and observation over time. As rules are established and developed, the prescriptive concept of grammatical correctness can arise. This often produces a discrepancy between contemporary usage and that which has been accepted, over time, as standard or «correct.» Linguists view prescriptive grammar as having little justification beyond their authors’ aesthetic tastes, although style guides may give useful advice about standard language employment based on descriptions of usage in contemporary writings. Linguistic prescriptions also form part of the explanation for variation in speech, particularly variation in the speech of an individual speaker (for example, why some speakers say «I didn’t do nothing,» some say «I didn’t do anything,» and some say one or the other depending on social context).

The formal study of grammar is an important part of schooling from a young age through advanced learning, though the rules taught in schools are not a «grammar» in the sense that most linguists use the term, as they are prescriptive in intent rather than descriptive.

Constructed languages (also called planned languages or conlangs) are more common in the modern-day, although still extremely uncommon compared to natural languages. Many have been designed to aid human communication (for example, naturalistic Interlingua, schematic Esperanto, and the highly logic-compatible artificial language Lojban). Each of these languages has its own grammar.

Syntax refers to the linguistic structure above the word level (for example, how sentences are formed) – though without taking into account intonation, which is the domain of phonology. Morphology, by contrast, refers to the structure at and below the word level (for example, how compound words are formed), but above the level of individual sounds, which, like intonation, are in the domain of phonology.[17] However, no clear line can be drawn between syntax and morphology. Analytic languages use syntax to convey information that is encoded by inflection in synthetic languages. Word order is not significant, and morphology is highly significant in a purely synthetic language, whereas morphology is not significant and syntax is highly significant in an analytic language. Chinese and Afrikaans are examples of highly analytic languages. Meaning is very context-dependent. (Both have some inflections, and both have had more in the past. They are becoming even less synthetic and more «purely» analytic over time.) Latin, which is highly synthetic, uses affixes and inflections to convey the same information that Chinese does with syntax. Because Latin words are quite (though not totally) self-contained, an intelligible Latin sentence can be made from elements that are arranged almost arbitrarily. Latin has a complex affixation and simple syntax, whereas in Chinese it is reversed.

Education

Prescriptive grammar is taught in primary and secondary school. The term «grammar school» historically referred to a school (attached to a cathedral or monastery) that teaches Latin grammar to future priests and monks. It originally referred to a school that taught students how to read, scan, interpret, and declaim Greek and Latin poets (including Homer, Virgil, and Euripides among others). These are related, but distinct, from modern British grammar schools.

A standard language is a dialect that is promoted above other dialects in writing, education, and, broadly speaking, in the public sphere. It contrasts with vernacular dialects, which may be the objects of study in academic, descriptive linguistics but which are rarely taught prescriptively. The standardized «first language» taught in primary education may be subject to political controversy because it may sometimes establish a standard defining nationality or ethnicity.

Recently, efforts have begun to update grammar instruction in primary and secondary education. The main focus has been to prevent the use of outdated prescriptive rules in favor of setting norms based on earlier descriptive research and to change perceptions about the relative «correctness» of prescribed standard forms in comparison to non-standard dialects. A series of metastudies have found that the explicit teaching of grammatical parts of speech and syntax has little or no effect on the improvement of student writing quality in elementary school, middle school or high school. Other methods of writing instruction had far greater positive effect, including strategy instruction, collaborative writing, summary writing, process instruction, sentence combining and inquiry projects.[18][19][20]

The preeminence of Parisian French has reigned largely unchallenged throughout the history of modern French literature. Standard Italian is based on the speech of Florence rather than the capital because of its influence on early literature. Likewise, standard Spanish is not based on the speech of Madrid but on that of educated speakers from more northern areas such as Castile and León (see Gramática de la lengua castellana). In Argentina and Uruguay standard Spanish is based on the local dialects of Buenos Aires and Montevideo (Rioplatense Spanish). Portuguese has, for now, two official standards, respectively Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese.

The Serbian variant of Serbo-Croatian is likewise divided; Serbia and the Republika Srpska of Bosnia and Herzegovina use their own distinct normative subvarieties, with differences in yat (the 32nd letter of the old Cyrillic alphabet) reflexes. The existence and codification of a distinct Montenegrin standard is a matter of controversy. Some treat Montenegrin as a separate standard lect, and some think that it should be considered another form of Serbian.

Norwegian has two standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk, the choice between the two is subject to controversy: Each Norwegian municipality can either declare one as its official language or it can remain «language neutral.» Nynorsk is backed by 27 percent of municipalities. The main language used in primary schools, chosen by referendum within the local school district, normally follows the official language of its municipality. Standard German emerged from the standardized chancellery use of High German in the 16th and 17th centuries. Until about 1800, it was almost exclusively a written language, but now it is so widely spoken that most of the former German dialects are nearly extinct.

Standard Chinese has official status as the standard spoken form of the Chinese language in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Republic of China (ROC), and the Republic of Singapore. Pronunciation of Standard Chinese is based on the local accent of Mandarin Chinese from Luanping, Chengde in Hebei Province near Beijing, while grammar and syntax are based on modern vernacular written Chinese.

Modern Standard Arabic is directly based on Classical Arabic, the language of the Qur’an. The Hindustani language has two standards, Hindi and Urdu.

In the United States, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar designated March 4 as National Grammar Day in 2008.[21]

Notes

- ↑ Douglas Harper, «Grammar,» Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ Janet Holmes, An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, 2001, ISBN 978-0582328617), 73-94. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ For more discussion of sets of grammars as populations, see: William Croft,Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach (Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, 2000, ISBN 978-0582356771), 13–20. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0521431460), 627f.

- ↑ Leigh Lundin, «The Power of Prepositions,» «On Writing,» Criminal Brief (2007): 216. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ Traditionally, the mental information used to produce and process linguistic utterances is referred to as «rules.» However, other frameworks employ different terminology, which has theoretical implications. Optimality theory, for example, uses the term «constraints,» while construction grammar, cognitive grammar, and other «usage-based» theories make reference to patterns, constructions, and «schemata.»

- ↑ William O’Grady, Michael Dobrovolsky and Francis Katamba, Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction (Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, 1996, ISBN 978-0582246911), 4–7, 464–539. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ Jeremy Butterfield, Damp Squid: The English Language Laid Bare (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0199574094), 142.

- ↑ «Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini,» Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013: Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī («Eight Chapters»), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the sixth to fifth century B.C.E. by the Indian grammarian Panini. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ William B. McGregor, Linguistics: An Introduction, 2nd. ed. (London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015, ISBN 978-0567583529), 15–16.

- ↑ Lionel Casson, Libraries in the Ancient World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0300097214), 45. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ G. Khan and J. B. Noah, The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought (Leiden, N.L.: Brill, 2000, ISBN 978-9004119338).

- ↑ Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn’s Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (Philadelphia, PA: Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1964).

- ↑ Roland Schäfer, Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen 2nd ed. (Berlin, DE: Language Science Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1537504957). Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ Christopher S. Butler, Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1 (Amsterdam, N. L.: John Benjamins, 2003, ISBN 978-1588113580), 121–124. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ Ronald Carter and Michael McCarthy, «Spoken Grammar: Where are We and Where are We Going?» Applied Linguistics (38) (2017): 1–20.

- ↑ Carlos Gussenhoven and Haike Jacobs, Understanding Phonology 2nd. ed. (London, U.K.: Hodder Arnold, 2005, ISBN 978-0340807354). Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ S. Graham and D. Perin, «Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York,» Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education, 2007.

- ↑ S. Graham and D. Perin, «A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students,» Journal of Educational Psychology 99(3) (2007): 445–476.

- ↑ S. Graham, D. McKeown, S. Kiuhara, and K.R. Harris, «A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades,» Journal of Educational Psychology 104(4) (2012): 879–896.

- ↑ «National Grammar Day,» Quick and Dirty Tips. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Butterfield, Jeremy. Damp Squid: The English Language Laid Bare. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0199574094

- Butler, Christopher S. Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1. Amsterdam, N.L.: John Benjamins, 2003. ISBN 978-1588113580

- Casson, Lionel. Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0300097214

- Croft, William. Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach. Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, 2000. ISBN 978-0582356771

- Gussenhoven, Carlos, and Haike Jacobs. Understanding Phonology 2nd. ed. London, U.K.: Hodder Arnold, 2005. ISBN 978-0340807354

- Holmes, Janet. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, 2001. ISBN 978-0582328617

- Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K. Pullum. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0521431460

- Khan, G., and J. B. Noah. The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought. Leiden, N.L.: Brill, 2000. ISBN 978-9004119338

- McGregor, William B. Linguistics: An Introduction, 2nd. ed. London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. ISBN 978-0567583529

- O’Grady, William, Michael Dobrovolsky, and Francis Katamba. Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, 1996. ISBN 978-0582246911

- Rundle, Bede. Grammar in Philosophy. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press, 1979. ISBN 0198246129

- Schäfer, Roland. Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen 2nd ed. Berlin, DE: Language Science Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1537504957

- Wechter, Pinchas. Ibn Barūn’s Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography. Philadelphia, PA: Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1964.

External links

Link retrieved February 18, 2023.

- Grammar from the Oxford English Dictionary

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Grammar history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Grammar»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- grammary (archaic)

- grammer (obsolete)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English gramer, gramarye, gramery, from Old French gramaire (“classical learning”), from the unattested *grammāria, an alteration of Latin grammatica, from Ancient Greek γραμματική (grammatikḗ, “skilled in writing”), from γράμμα (grámma, “line of writing”), from γράφω (gráphō, “write”), from Proto-Indo-European *gerbʰ- (“to carve, scratch”). Displaced native Old English stæfcræft.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ˈɡɹæ.mə(ɹ)/

- (General American) enPR: gră’mər, IPA(key): /ˈɡɹæ.mɚ/

- Rhymes: -æmə(ɹ)

- Hyphenation: gram‧mar

Noun[edit]

grammar (countable and uncountable, plural grammars)

- A system of rules and principles for speaking and writing a language.

- (uncountable, linguistics) The study of the internal structure of words (morphology) and the use of words in the construction of phrases and sentences (syntax).

- A book describing the rules of grammar of a language.

- (computing theory) A formal system specifying the syntax of a language.

- 2006, Patrick Blackburn · Johan Bos · Kristina Striegnitz, Learn Prolog Now!, §8.2

- Because real lexicons are big and complex, from a software engineering perspective it is best to write simple grammars that have a simple, well-defined way, of pulling out the information they need from vast lexicons. That is, grammars should be thought of as separate entities which can access the information contained in lexicons. We can then use specialised mechanisms for efficiently storing the lexicon and retrieving data from it.

- 2006, Patrick Blackburn · Johan Bos · Kristina Striegnitz, Learn Prolog Now!, §8.2

- Actual or presumed prescriptive notions about the correct use of a language.

- (computing theory) A formal system defining a formal language

- The basic rules or principles of a field of knowledge or a particular skill.

- 2011, Javier Solana and Daniel Innerarity, Project Syndicate, The New Grammar of Power:

- We must learn a new grammar of power in a world that is made up more of the common good – or the common bad – than of self-interest or national interest.

- 2011, Javier Solana and Daniel Innerarity, Project Syndicate, The New Grammar of Power:

- (Britain, archaic) A book describing these rules or principles; a textbook.

-

a grammar of geography

-

- (UK) A grammar school.

-

2012 January 11, Graeme Paton, “A green light for more grammars?”, in The Daily Telegraph:

-

Synonyms[edit]

- (study & field of study in medieval Latin contexts): glomery

- (linguistics): morpho-syntax (from the relationship between morphology and syntax)

Hyponyms[edit]

- context-sensitive grammar

- finite-state grammar

- Turing-complete grammar

- normative grammar

Derived terms[edit]

- case grammar

- categorial grammar

- compositional grammar

- context-free grammar

- dependence grammar

- dependency grammar

- formal grammar

- generative grammar

- grammar checker

- grammar cop

- grammar nazi

- grammar Nazi

- grammar police

- grammar school

- grammarian

- grammarless

- grammarlike

- Montague grammar

- natural grammar

- transformational grammar

- universal grammar

[edit]

- glamour

- gramarye

Translations[edit]

rules for speaking and writing a language

- Afrikaans: grammatika (af)

- Albanian: gramatikë (sq) f

- Amharic: ሰዋሰው (säwasäw)

- Arabic: قَوَاعِد (ar) pl (qawāʕid), نَحْو m (naḥw)

- Hijazi Arabic: قَواعِد f pl (qawāʿid)

- Aragonese: gramatica f

- Armenian: քերականություն (hy) (kʿerakanutʿyun)

- Assamese: ব্যাকৰণ (byakoron)

- Asturian: gramática f

- Azerbaijani: qrammatika (az)

- Bashkir: грамматика (grammatika)

- Basque: gramatika (eu)

- Belarusian: грама́тыка f (hramátyka)

- Bengali: ব্যাকরণ (bn) (bêkoron)

- Bikol Central: balanghayan

- Breton: yezhadur (br)

- Bulgarian: грама́тика (bg) f (gramátika)

- Burmese: သဒ္ဒါ (my) (sadda)

- Catalan: gramàtica (ca) f

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 文法 (man4 faat3), 語法/语法 (jyu5 faat3)

- Dungan: йүфа (yüfa)

- Hakka: 語法/语法 (ngî-fap)

- Mandarin: 語法/语法 (zh) (yǔfǎ), 文法 (zh) (wénfǎ)

- Min Dong: 語法/语法 (ngṳ̄-huák)

- Min Nan: 文法 (zh-min-nan) (bûn-hoat), 語法/语法 (zh-min-nan) (gír-hoat, gú-hoat, gí-hoat)

- Wu: 語法/语法 (nyy faq)

- Chuvash: грамматика (grammat̬ik̬a)

- Czech: mluvnice (cs) f, gramatika (cs) f

- Danish: grammatik (da) c

- Dutch: spraakkunst (nl) f, grammatica (nl) f

- Esperanto: gramatiko

- Estonian: grammatika, keeleõpetus

- Faroese: mállæra f

- Finnish: kielioppi (fi)

- French: grammaire (fr) f

- Galician: gramática f

- Georgian: გრამატიკა (gramaṭiḳa)

- German: Grammatik (de) f, Sprachlehre (de) f

- Greek: γραμματική (el) f (grammatikí)

- Ancient: γραμματική f (grammatikḗ)

- Greenlandic: oqaasilerissutit

- Gujarati: વ્યાકરણ (gu) m (vyākraṇ)

- Hausa: nahawu (ha)

- Hebrew: דִּקְדּוּק m (dikdúk)

- Hindi: व्याकरण (hi) m (vyākraṇ), ब्याकरण m (byākraṇ)

- Fiji Hindi: vyakaran

- Hungarian: nyelvtan (hu)

- Icelandic: málfræði (is) f

- Ilocano: alagadan

- Indonesian: tata bahasa (id)

- Interlingua: grammatica (ia)

- Irish: gramadach f

- Italian: grammatica (it) f

- Japanese: 文法 (ja) (ぶんぽう, bunpō)

- Kannada: ವ್ಯಾಕರಣ (kn) (vyākaraṇa)

- Kazakh: грамматика (grammatika)

- Khmer: វេយ្យាករណ៍ (km) (vɨyyiəkɑɑ)

- Korean: 문법(文法) (ko) (munbeop)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: ڕێزمان (ckb) (rêzman)

- Northern Kurdish: rêziman (ku)

- Kyrgyz: грамматика (ky) (grammatika)

- Ladino: gramatika

- Lao: ໄວຍະກອນ (lo) (wai nya kǭn)

- Latvian: gramatika f

- Lithuanian: gramatika (lt) f

- Luxembourgish: Grammaire f, Grammatik f

- Macedonian: граматика f (gramatika)

- Malay: tatabahasa (ms), parmasastera

- Malayalam: വ്യാകരണം (ml) (vyākaraṇaṃ)

- Maltese: grammatika f

- Manx: grammeydys

- Maori: tikanga wetereo, wetereo

- Marathi: व्याकरण n (vyākraṇ)

- Mirandese: gramática f

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: хэл зүй (mn) (xel züj), дүрэм (mn) (dürem)

- Nepali: व्याकरण (ne) (vyākaraṇ)

- Newar: व्याकरण (wyākaraṇa)

- Norman: grammaithe f

- Northern Sami: giellaoahppa

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: grammatikk (no) m

- Nynorsk: grammatikk m

- Occitan: gramatica (oc) f

- Old English: stæfcræft m

- Ossetian: грамматикӕ (grammatikæ)

- Pashto: ګرامر m (gerāmar), صرف و نحو (ps) f (sarf o nahwa), پښويه (ps) f (px̌oya), ژبدود m (žǝbdod), ګړپوهنه f (gǝṛрohǝna)

- Persian: دستور زبان (fa) (dastur-e zabân), گرامر (fa) (gerâmer)

- Polish: gramatyka (pl) f

- Portuguese: gramática (pt) f

- Punjabi: ਵਿਆਕਰਨ (viākaran)

- Quechua: simi kamachiy

- Romanian: gramatică (ro) f

- Russian: грамма́тика (ru) f (grammátika)

- Rusyn: ґрама́тіка f (gramátika)

- Rwanda-Rundi: ikibonezamvugo (Rwanda)

- Samogitian: gramatėka f

- Sanskrit: व्याकरण (sa) n (vyākaraṇa)

- Scottish Gaelic: gràmar m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: грама̀тика f, сло́вница f

- Roman: gramàtika (sh) f, slóvnica (sh) f

- Sinhalese: ව්යාකරණ (wyākaraṇa)

- Slovak: gramatika (sk) f

- Slovene: slovnica (sl)

- Spanish: gramática (es) f

- Swahili: sarufi (sw)

- Swedish: grammatik (sv) c

- Tagalog: balarila

- Tajik: дастури забон (tg) (dasturi zabon), грамматика (tg) (grammatika)

- Tamil: இலக்கணம் (ta) (ilakkaṇam)

- Tatar: грамматика (tt) (grammatika)

- Telugu: నామవాచకం (te) (nāmavācakaṁ)

- Thai: ไวยากรณ์ (th) (wai-yaa-gɔɔn)

- Tibetan: བརྡ་སྤྲོད་ཀྱི་གཞུང (brda sprod kyi gzhung), སུམ་རྟགས (sum rtags)

- Turkish: dil bilgisi (tr), gramer (tr)

- Turkmen: grammatika (tk)

- Ukrainian: грама́тика f (hramátyka)

- Urdu: ویاکرن m (vyākaraṇ), قواعدِ زبان (qawā’id-e zabān)

- Uyghur: گرامماتىكا (grammatika)

- Uzbek: grammatika (uz)

- Vietnamese: ngữ pháp (vi) (語法 (vi))

- Volapük: gramat (vo)

- Welsh: gramadeg (cy)

- Yiddish: גראַמאַטיק (yi) f (gramatik)

- Zealandic: grammaotica

- Zhuang: yijfaz

study of internal structure and use of words

- Albanian: gramatikë (sq) f

- Arabic: عِلْم قَوَاعِد m (ʕilm qawāʕid)

- Belarusian: грама́тыка f (hramátyka)

- Bulgarian: грама́тика (bg) f (gramátika)

- Catalan: gramàtica (ca)

- Finnish: kielioppi (fi)

- French: grammaire (fr) f

- Galician: gramática f

- German: Grammatik (de) f, Grammatiktheorie (de) f, Sprachlehre (de) f, Sprachkunst (de) f

- Greek: γραμματική (el) f (grammatikí)

- Ancient: γραμματική f (grammatikḗ)

- Interlingua: grammatica (ia)

- Italian: grammatica (it) f

- Japanese: 文法 (ja) (ぶんぽう, bunpō)

- Korean: * Korean: 문법(文法) (ko) (munbeop), 문법학(文法學) (munbeophak)

- Latin: grammatica (la) f, grammatice f, litteratio f, litteratoria f

- Latvian: gramatika f

- Macedonian: граматика f (gramatika)

- Maori: wetereo

- Norman: grammaithe f

- Persian: دستور زبان (fa) (dastur-e zabân), گرامر (fa) (gerâmer)

- Polish: gramatyka (pl) f

- Portuguese: gramática (pt) f

- Russian: грамма́тика (ru) f (grammátika)

- Scottish Gaelic: gràmar m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: грама̀тика f

- Roman: gramàtika (sh) f

- Slovene: slovnica (sl)

- Spanish: gramática (es) f

- Swedish: grammatik (sv) c

- Tajik: дастури забон (tg) (dasturi zabon), грамматика (tg) (grammatika)

- Turkish: dil bilgisi (tr), gramer (tr)

book describing grammar

- Arabic: قَوَاعِد (ar) pl (qawāʕid)

- Bulgarian: уче́бник по грама́тика m (učébnik po gramátika)

- Catalan: gramàtica (ca)

- Dutch: spraakkunstboek n

- Estonian: grammatika

- Faroese: mállæra f

- Finnish: kielioppikirja

- French: grammaire (fr) f

- Galician: gramática f

- German: Grammatik (de) f, Sprachlehre (de) f

- Greek: γραμματική (el) f (grammatikí)

- Icelandic: málfræði (is) f, málfræðibók f

- Interlingua: grammatica (ia)

- Italian: grammatica (it) f

- Japanese: 文法書 (ぶんぽうしょ, bunpōsho)

- Korean: 문법책(文法冊) (ko) (munbeopchaek)

- Latvian: gramatika f

- Macedonian: граматика f (gramatika)

- Manx: lioar ghrammeydys f

- Maori: pukapuka wetereo

- Norman: grammaithe f

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: grammatikk (no) m

- Nynorsk: grammatikk m

- Occitan: gramatica (oc) f

- Portuguese: gramática (pt) f

- Russian: уче́бник по грамма́тике m (učébnik po grammátike), грамма́тика (ru) f (grammátika)

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: грама̀тика f, сло́вница f

- Roman: gramàtika (sh) f, slóvnica (sh) f

- Slovene: slovnica (sl)

- Spanish: gramática (es) f

- Swedish: grammatik (sv) c, grammatikbok c, språklära c

- Turkish: dil bilgisi kitabı, gramer kitabı

- Ukrainian: грама́тика f (hramátyka)

Verb[edit]

grammar (third-person singular simple present grammars, present participle grammaring, simple past and past participle grammared)

- (obsolete, intransitive) To discourse according to the rules of grammar; to use grammar.

-

c. 1619–1623, John Ford, “The Lavves of Candy”, in Comedies and Tragedies […], London: […] Humphrey Robinson, […], and for Humphrey Moseley […], published 1647, →OCLC, (please specify the act number in uppercase Roman numerals, and the scene number in lowercase Roman numerals):

-

She is in her Moods, and her Tenses: / I’ll Grammar with you, / And make a trial how I can decline you

-

-

See also[edit]

grammar on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

- Appendix:Glossary of grammar

- Category:Grammar

Further reading[edit]

- grammar at The Septic’s Companion: A British Slang Dictionary

Manx[edit]

Noun[edit]

grammar m (genitive singular [please provide], plural [please provide])

- grammar

Synonyms[edit]

- grammeydys

[edit]

- grammeydagh

- neughrammeydoil

Mutation[edit]

| Manx mutation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Radical | Lenition | Eclipsis |

| grammar | ghrammar | ngrammar |

| Note: Some of these forms may be hypothetical. Not every possible mutated form of every word actually occurs. |

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Grammar history and structure, an encyclopedic synthetic article that describes the importance of grammar for the usage and the literature of a language.

The minimum grammar is no grammar at all.

Giuseppe Peano

Grammar, branch of linguistics dealing with the form and structure of words (morphology), and their interrelation in sentences (syntax). The study of grammar reveals how language works.

“Grammar” is a term devised by the Greeks, in whose language it literally means “that which pertains to writing.” The modern tendency, however, is to regard grammar as the study of speech rather than of writing, or at least of both. The Romans had a saying Verba volant, scripta manent (What is spoken flies away, what is written endures), which perhaps serves to illustrate the point of view of the Greeks, as well as of grammarians generally. The written word, remaining as a permanent record, is worthy of greater consideration than the fleeting spoken word.

Mario Pei

Kinds of Grammar

Most people first encounter grammar in connection with the study of their own or of a second language in school. This kind of grammar is called normative, or prescriptive, because it defines the role of the various parts of speech and purports to tell what is the norm, or rule, of “correct” usage. Prescriptive grammars state how words and sentences are to be put together in a language so that the speaker will be perceived as having good grammar. When people are said to have good or bad grammar, the inference is that they obey or ignore the rules of accepted usage associated with the language they speak.

Language-specific prescriptive grammar is only one way to look at word and sentence formation in language.

Other grammarians are primarily interested in the changes in word and sentence construction in a language over the years – for example, how Old English, Middle English, and Modern English differ from one another; this approach is known as historical grammar. Some grammarians seek to establish the differences or similarities in words and word order in various languages. Thus, specialists in comparative grammar study sound and meaning correspondences among languages to determine their relationship to one another. By looking at similar forms in related languages, grammarians can discover how different languages may have influenced one another. Still other grammarians investigate how words and word order are used in social contexts to get messages across; this is called functional grammar.

Some grammarians are more concerned, however, with determining how the meaningful arrangement of the basic word-building units (morphemes) and sentence-building units (constituents) can best be described. This approach is called descriptive grammar. Descriptive grammars contain actual speech forms recorded from native speakers of a particular language and represented by means of written symbols. Descriptive grammars indicate what languages – often those never before written down or otherwise recorded – are like structurally.

These approaches to grammar (prescriptive, historical, comparative, functional, and descriptive) focus on word building and word order; they are concerned only with those aspects of language that have structure. These types of grammar constitute a part of linguistics that is distinct from phonology (the linguistic study of sound) and semantics (the linguistic study of meaning or content). Grammar to the prescriptivist, historian, comparativist, functionalist, and descriptivist is then the organizational part of language – how speech is put together, how words and sentences are formed, and how messages are communicated.

Specialists called transformational-generative grammarians, such as the American linguistic scholar Noam Chomsky, approach grammar quite differently – as a theory of language. By language, these scholars mean the knowledge human beings have that allows them to acquire any language. Such a grammar is a kind of universal grammar, an analysis of the principles underlying all the various human grammars.

History of Grammatical Study

The study of grammar began with the ancient Greeks, who engaged in philosophical speculation about languages and described language structure. This grammatical tradition was passed on to the Romans, who translated the Greek names for the parts of speech and grammatical endings into Latin; many of these terms (nominative, accusative, dative) are still found in modern grammars. But the Greeks and Romans were unable to determine how languages are related. This problem spurred the development of comparative grammar, which became the dominant approach to linguistic science in the 19th century.

Early grammatical study appears to have gone hand in hand with efforts to understand archaic writings. Thus, grammar was originally tied to societies with long-standing written traditions. The earliest extant grammar is that of the Sanskrit language of India, compiled by the Indian grammarian Panini (flourished about 400 BC). This sophisticated analysis showed how words are formed and what parts of words carry meaning. Ultimately, the grammars of Panini and other Hindu scholars helped in the interpretation of Hindu religious literature written in Sanskrit. The Arabs are believed to have begun the grammatical study of their language before medieval times. In the 10th century the Jews completed a Hebrew lexicon; they also produced a study of the language of the Old Testament.

The Greek grammarian Dionysius Thrax wrote the Art of Grammar, upon which many later Greek, Latin, and other European grammars were based. With the spread of Christianity and the translation of the Scriptures into the languages of the new Christians, written literatures began to develop among previously nonliterate peoples. By the Middle Ages, European scholars generally knew, in addition to their own languages and Latin, the languages of their nearest neighbors. This access to several languages set scholars to thinking about how languages might be compared. The revival of classical learning in the Renaissance laid the foundation, however, for a misguided attempt by grammarians to fit all languages into the structure of Greek and Latin.

More positively, medieval Christianity and Renaissance learning led to 16th- and 17th-century surveys of all the then-known languages in an attempt to determine which language might be the oldest. On the basis of the Bible, Hebrew was frequently so designated. Other languages – Dutch, for example – were also chosen because of accidental circumstances rather than linguistic facts. In the 18th century less haphazard comparisons began to be made, culminating in the assumption by the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz that most languages of Europe, Asia, and Egypt came from the same original language – a language referred to as Indo-European.

In the 19th century scholars developed systematic analyses of parts of speech, mostly built on the earlier analyses of Sanskrit. The early Sanskrit grammar of Panini was a valuable guide in the compilation of grammars of the languages of Europe, Egypt, and Asia. This writing of grammars of related languages, using Panini’s work as a guide, is known as Indo-European grammar, a method of comparing and relating the forms of speech in numerous languages.

The Renaissance approach to grammar, which based the description of all languages on the model of Greek and Latin, died slowly, however. Not until the early 20th century did grammarians began to describe languages on their own terms. Noteworthy in this regard are the Handbook of American Indian Languages (1911), the work of the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas and his colleagues; and the studies by the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen, A Modern English Grammar (pub. in four parts, 1909-31), and The Philosophy of Grammar (1924). Boas’s work formed the basis of various types of American descriptive grammar study. Jespersen’s work was the precursor of such current approaches to linguistic theory as transformational generative grammar.

Boas challenged the application of conventional methods of language study to those non-Indo-European languages with no written records, such as the ones spoken by Native North Americans. He saw grammar as a description of how human speech in a language is organized. A descriptive grammar should describe the relationships of speech elements in words and sentences. Given impetus by the fresh perspective of Boas, the approach to grammar known as descriptive linguistics became dominant in the U.S. during the first half of the 20th century.

Jespersen, like Boas, thought grammar should be studied by examining living speech rather than by analyzing written documents, but he wanted to ascertain what principles are common to the grammars of all languages, both at the present time (the so-called synchronic approach) and throughout history (the diachronic approach). Descriptive linguists developed precise and rigorous methods to describe the formal structural units in the spoken aspect of any language. The approach to grammar that developed with this view is known as structural.

A structural grammar should describe what the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure referred to by the French word langue – denoting the system underlying a particular language – that is, what members of a speech community speak and hear that will pass as acceptable grammar to other speakers and hearers of that language. Actual speech forms (referred to by the structuralists by the French word parole) represent instances of langue but, in themselves, are not what a grammar should describe. The structuralist approach to grammar conceives of a particular language such as French, Swahili, Chinese, or Arabic as a system of elements at various levels – sound, word, sentence, meaning- that interrelate. A structuralist grammar therefore describes what relationships underlie all instances of speech in a particular language; a descriptive grammar describes the elements of transcribed (recorded, spoken) speech.

By the mid-20th century, Chomsky, who had studied structural linguistics, was seeking a way to analyze the syntax of English in a structural grammar. This effort led him to see grammar as a theory of language structure rather than a description of actual sentences. His idea of grammar is that it is a device for producing the structure, not of langue (that is, not of a particular language), but of competence – the ability to produce and understand sentences in any and all languages. His universalist theories are related to the ideas of those 18th- and early 19th-century grammarians who urged that grammar be considered a part of logic – the key to analyzing thought. Universal grammarians such as the British philosopher John Stuart Mill, writing as late as 1867, believed rules of grammar to be language forms that correspond to universal thought forms.

To find out more about this topic you can also read the following articles:

Why is grammar so important?

In defence of grammar

The essence of Grammar

Language and grammar

English grammar summaries

Carl William Brown

Surrealist, humorous, nihilistic and romantic character. In tristitia hilaris, in hilaritate tristis.