From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The name Britain originates from the Common Brittonic term *Pritanī and is one of the oldest known names for Great Britain, an island off the north-western coast of continental Europe. The terms Briton and British, similarly derived, refer to its inhabitants and, to varying extents, the smaller islands in the vicinity. «British Isles» is the only ancient name for these islands to survive in general usage.

Etymology[edit]

«Britain» comes from Latin: Britannia~Brittania, via Old French Bretaigne and Middle English Breteyne, possibly influenced by Old English Bryten(lond), probably also from Latin Brittania, ultimately an adaptation of the Common Brittonic name for the island, *Pritanī.[1][2]

The earliest written reference to the British Isles derives from the works of the Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia; later Greek writers such as Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo who quote Pytheas’ use of variants such as Πρεττανική (Prettanikē), «The Britannic [land, island]», and nēsoi brettaniai, «Britannic islands», with *Pretani being a Celtic word that might mean «the painted ones» or «the tattooed folk», referring to body decoration (see below).[3]

The modern Welsh name for the island is (Ynys) Prydain. This may demonstrate that the original Common Brittonic form had initial P- not B- (which would give **Brydain) and -t- not -tt- (else **Prythain). This may be explained as containing a stem *prit- (Welsh pryd, Old Irish cruith; < Proto-Celtic *kwrit-), meaning «shape, form», combined with an adjectival suffix. This leaves us with *Pritanī.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

History[edit]

Written record[edit]

The first known written use of the word was an ancient Greek transliteration of the original P-Celtic term. It is believed to have appeared within a periplus written in about 325 BC by the geographer and explorer Pytheas of Massalia, but no copies of this work survive. The earliest existing records of the word are quotations of the periplus by later authors, such as those within Diodorus of Sicily’s history (c. 60 BC to 30 BC), Strabo’s Geographica (c. 7 BC to AD 19) and Pliny’s Natural History (AD 77).[10] According to Strabo, Pytheas referred to Britain as Bretannikē, which is treated a feminine noun.[11][12][13][14] Although technically an adjective (the Britannic or British) it may have been a case of noun ellipsis, a common mechanism in ancient Greek. This term along with other relevant ones, subsequently appeared inter alia in the following works:

- Pliny referred to the main island as Britannia, with Britanniae describing the island group.[15][16]

- Catullus also used the plural Britanniae in his Carmina.[17][18]

- Avienius used insula Albionum in his Ora Maritima.[19]

- Orosius used the plural Britanniae to refer to the islands and Britanni to refer to the people thereof.[20]

- Diodorus referred to Great Britain as Prettanikē nēsos and its inhabitants as Prettanoi.[21][22]

- Ptolemy, in his Almagest, used Brettania and Brettanikai nēsoi to refer to the island group and the terms megale Brettania (Great Britain) and mikra Brettania (little Britain) for the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, respectively.[23] However, in his Geography, he referred to both Alwion (Great Britain) and Iwernia (Ireland) as a nēsos Bretanikē, or British island.[24]

- Marcian of Heraclea, in his Periplus maris exteri, described the island group as αί Πρεττανικαί νήσοι (the Prettanic Isles).[25]

- Stephanus of Byzantium used the term Ἀλβίων (Albion) to refer to the island, and Ἀλβιώνιοι (Albionioi) to refer to its people.[26]

- Pseudo-Aristotle used nēsoi Brettanikai, Albion and Ierne to refer to the island group, Great Britain, and Ireland, respectively.[27]

- Procopius, in the 6th century AD, used the terms Brittia and Brettania though he considered them to be different islands, the former being located between the latter and Thule. Moreover, according to him on Brittia lived three different nations, the homonymous Brittones (Britons), the Angiloi (English) and the Phrissones (Frisians).[28][29]

As seen above, the original spelling of the term is disputed. Ancient manuscripts alternated between the use of the P- and the B-, and many linguists believe Pytheas’s original manuscript used P- (Prettania) rather than B-. Although B- is more common in these manuscripts, many modern authors quote the Greek or Latin with a P- and attribute the B- to changes by the Romans in the time of Julius Caesar;[30] the relevant, attested sometimes later, change of the spelling of the word(s) in Greek, as is also sometimes done in modern Greek, from being written with a double tau to being written with a double nu, is likewise also explained by Roman influence, from the aforementioned change in the spelling in Latin.[31] For example, linguist Karl Schmidt states that the «name of the island was originally transmitted as Πρεττανία (with Π instead of Β) … as is confirmed by its etymology».[32]

According to Barry Cunliffe:

- It is quite probable that the description of Britain given by the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus in the first century BC derives wholly or largely from Pytheas. What is of particular interest is that he calls the island «Pretannia» (Greek «Prettanikē»), that is «the island of the Pretani, or Priteni». «Pretani» is a Celtic word that probably means «the painted ones» or «the tattooed folk», referring to body decoration – a reminder of Caesar’s observations of woad-painted barbarians. In all probability the word «Pretani» is an ethnonym (the name by which the people knew themselves), but it remains an outside possibility that it was their continental neighbours who described them thus to the Greek explorers.[33]

Roman period[edit]

Following Julius Caesar’s expeditions to the island in 55 and 54 BC, Brit(t)an(n)ia was predominantly used to refer simply to the island of Great Britain[citation needed]. After the Roman conquest under the Emperor Claudius in AD 43, it came to be used to refer to the Roman province of Britain (later two provinces), which at one stage consisted of part of the island of Great Britain south of Hadrian’s wall.[34]

Medieval[edit]

In Old English or Anglo-Saxon, the Graeco-Latin term referring to Britain entered in the form of Bryttania, as attested by Alfred the Great’s translation of Orosius’ Seven Books of History Against the Pagans.[35]

The Latin name Britannia re-entered the language through the Old French Bretaigne. The use of Britons for the inhabitants of Great Britain is derived from the Old French bretun, the term for the people and language of Brittany, itself derived from Latin and Greek, e.g. the Βρίττωνες of Procopius.[28] It was introduced into Middle English as brutons in the late 13th century.[36]

Modern usage[edit]

There is much conflation of the terms United Kingdom, Great Britain, Britain, and England. In many ways accepted usage allows some of these to overlap, but some common usages are incorrect.

The term Britain is widely used as a common name for the sovereign state of the United Kingdom, or UK for short. The United Kingdom includes three countries on the largest island, which can be called the island of Britain or Great Britain: these are England, Scotland and Wales. However the United Kingdom also includes Northern Ireland on the neighbouring island of Ireland, the remainder of which is not part of the United Kingdom. England is not synonymous with Britain, Great Britain, or United Kingdom.

The classical writer, Ptolemy, referred to the larger island as great Britain (megale Bretannia) and to Ireland as little Britain (mikra Brettania) in his work, Almagest (147–148 AD).[37] In his later work, Geography (c. 150 AD), he gave these islands the names[38] Ἀλουίωνος (Alwiōnos), Ἰουερνίας (Iwernias), and Mona (the Isle of Anglesey), suggesting these may have been native names of the individual islands not known to him at the time of writing Almagest.[39] The name Albion appears to have fallen out of use sometime after the Roman conquest of Great Britain, after which Britain became the more commonplace name for the island called Great Britain.[9]

After the Anglo-Saxon period, Britain was used as a historical term only. Geoffrey of Monmouth in his pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) refers to the

island of Great Britain as Britannia major («Greater Britain»), to distinguish it from Britannia minor («Lesser Britain»), the continental region which approximates to modern Brittany, which had been settled in the fifth and sixth centuries by Celtic migrants from the British Isles.[40] The term Great Britain was first used officially in 1474, in the instrument drawing up the proposal for a marriage between Cecily the daughter of Edward IV of England, and James the son of James III of Scotland, which described it as «this Nobill Isle, callit Gret Britanee». It was used again in 1603, when King James VI and I styled himself «King of Great Britain» on his coinage.[41]

The term Great Britain later served to distinguish the large island of Britain from the French region of Brittany (in French Grande-Bretagne and Bretagne respectively). With the Acts of Union 1707 it became the official name of the new state created by the union of the Kingdom of England (which then included Wales) with the Kingdom of Scotland, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain.[42] In 1801, the name of the country was changed to United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, recognising that Ireland had ceased to be a distinct kingdom and, with the Acts of Union 1800, had become incorporated into the union. After Irish independence in the early 20th century, the name was changed to United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which is still the official name. In contemporary usage therefore, Great Britain, while synonymous with the island of Britain, and capable of being used to refer politically to England, Scotland and Wales in combination, is sometimes used as a loose synonym for the United Kingdom as a whole. For example, the term Team GB and Great Britain were used to refer to the United Kingdom’s Olympic team in 2012 although this included Northern Ireland. The usage ‘GBR’ in this context is determined by the International Olympic Committee (see List of IOC country codes) which accords with the international standard ISO 3166. The internet country code, «.uk» is an anomaly, being the only Country code top-level domain that does not follow ISO 3166.

See also[edit]

- Glossary of names for the British

- Terminology of the British Isles

- Hibernia

- Cruthin

- Prydain

- Pytheas

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Britain». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Chadwick, Hector Munro, Early Scotland: The Picts, the Scots and the Welsh of Southern Scotland, Cambridge University Press, 1949 (2013 reprint), p. 68

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Chadwick 1949, pp. 66–80.

- ^ Maier 1997, p. 230.

- ^ Ó Cróinín 2005, p. 213

- ^ Dunbavin 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Oman, Charles (1910), «England Before the Norman Conquest», in Oman, Charles; Chadwick, William (eds.), A History of England, vol. I, New York; London: GP Putnam’s Sons; Methuen & Co, pp. 15–16,

The corresponding form used by the Brythonic ‘P Celts’ would be Priten … Since therefore he visited the Pretanic and not the Kuertanic Isle, he must have heard its name, when he visited its southern shores, from Brythonic and not from Goidelic inhabitants.

- ^ a b Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- ^ Book I.4.2–4, Book II.3.5, Book III.2.11 and 4.4, Book IV.2.1, Book IV.4.1, Book IV.5.5, Book VII.3.1

- ^ Βρεττανική. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book I. Chapter IV. Section 2 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book IV. Chapter II. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book IV. Chapter IV. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia Book IV. Chapter XLI

Latin text and

English translation

at the Perseus Project. - ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, lemma Britanni II.A at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Gaius Valerius Catullus’ Carmina Poem 29, verse 20,

Latin text and

English translation

at the Perseus Project. See also Latin text and its English translation side by side at Wikisource. - ^ Gaius Valerius Catullus’ Carmina Poem 45, verse 22, Latin text and

English translation

at the Perseus Project. See also Latin text and its English translation side by side at Wikisource. - ^ Avienius’ Ora Maritima, verses 111–112, i.e. eamque late gens Hiernorum colit; propinqua rursus insula Albionum patet.

- ^ Orosius, Histories against the Pagans, VII. 40.4 Latin text at attalus.org.

- ^

Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica Book V. Chapter XXI. Section 1

Greek text at the Perseus Project. - ^ Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica Book V. Chapter XXI. Section 2

Greek text at the Perseus Project. - ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1898). «Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ’, κε’«. In Heiberg, J.L. (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia (PDF). Vol. 1 Syntaxis Mathematica. Leipzig: in aedibus B.G.Teubneri. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1843). «index of book II». In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia (PDF). Vol. 1. Leipzig: sumptibus et typis Caroli Tauchnitii. p. 59.

- ^ Marcianus Heracleensis; Müller, Karl Otfried; et al. (1855). «Periplus Maris Exteri, Liber Prior, Prooemium». In Firmin Didot, Ambrosio (ed.). Geographi Graeci Minores. Vol. 1. Paris. pp. 516–517. Greek text and Latin Translation thereof archived at the Internet Archive.

- ^ Ethnika 69.16, i.e. Stephanus Byzantinus’ Ethnika (kat’epitomen), lemma Ἀλβίων Meineke, Augustus, ed. (1849). Stephani Byzantii Ethnicorvm quae svpersvnt. Vol. 1. Berlin: Impensis G. Reimeri. p. 69.

- ^ Greek «… ἐν τούτῳ γε μὴν νῆσοι μέγιστοι τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι δύο, Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Ἀλβίων καὶ Ἰέρνη, …», transliteration «… en toutoi ge men nesoi megistoi tynchanousin ousai dyo, Brettanikai legomenai, Albion kai Ierne, …», translation «… There are two very large islands in it, called the British Isles, Albion and Ierne; …»; Aristotle (1955). «On the Cosmos». On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos. D. J. Furley (trans.). William Heinemann LTD, Harvard University Press. 393b pp. 360–361 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Procopius (1833). «De Bello Gotthico, IV, 20». In Dindorfius, Guilielmus; Niebuhrius, B.G. (eds.). Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae. Vol. Pars II Volumen II (Impensis Ed. Weberis ed.). Bonnae. pp. 559–580.

- ^ Smith, William, ed. (1854). «BRITANNICAE INSULAE or BRITANNIA». Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, illustrated by numerous engravings on wood. London: Walton and Maberly; John Murray. pp. 559–560. Available online at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Rhys, John (July–October 1891). «Certain National Names of the Aborigines of the British Isles: Sixth Rhind Lecture». The Scottish Review. XVIII: 120–143.

- ^ lemma Βρετανία; Babiniotis, Georgios. Dictionary of Modern Greek. Athens: Lexicology Centre.

- ^ Schmidt 1993, p. 68

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-967945-4.

- ^ Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- ^ Sedgefield, Walter John (1928). An Anglo-Saxon Verse-Book. Manchester University Press. p. 292.

- ^ OED, s.v. «Briton».

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1898). «Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ’,κε’«. In Heiberg, J.L. (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia (PDF). Vol. 1 Syntaxis Mathematica. Leipzig: in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1843). «Book II, Prooemium and chapter β’, paragraph 12». In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia (PDF). Vol. 1. Leipzig: sumptibus et typis Caroli Tauchnitii. pp. 59, 67.

- ^ Freeman, Philip (2001). Ireland and the classical world. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-292-72518-3.

- ^ «Is Great Britain really a ‘small island’?». BBC News. 14 September 2013.

- ^ Jack, Sybil (2004). «‘A Pattern for a King’s Inauguration’: The Coronation of James I in England» (PDF). Parergon. 21 (2): 67–91. doi:10.1353/pgn.2004.0068. S2CID 144654775.

- ^ «After the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, the nation’s official name became ‘Great Britain'», The American Pageant, Volume 1, Cengage Learning (2012)

References[edit]

- Fife, James (1993). «Introduction». In Ball, Martin J; Fife, James (eds.). The Celtic Languages. Routledge Language Family Descriptions. Routledge. pp. 3–25.

- Schmidt, Karl Horst (1993), «Insular Celtic: P and Q Celtic», in Ball, Martin J; Fife, James (eds.), The Celtic Languages, Routledge Language Family Descriptions, Routledge, pp. 64–99

Look up Britain in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Further reading[edit]

- Koch, John T. «New Thoughts on Albion, Iernē, and the Pretanic Isles (Part One).» Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 6 (1986): 1–28. www.jstor.org/stable/20557171.

23 December 2017

Britain is an ancient name. Where does it come from?

What’s in a name?

Place names are more complex than they first appear. They can be geographical expressions which allow people to orient themselves physically and mentally in their surroundings. They can be mental ‘boxes’ that enable people to think about space and what happens within them or between them. Identity is bound up with place names and who is allowed to name what often shows how power is structured and negotiated between people, communities and identities. Creating place names can be collaborative, they can be a form of domination.

The history of the creation and use of the names of Britain, Scotland, Wales, Ireland and England reflect the nuanced meaning of names. This Briefing is part of a series that will explore all these shared and inextricably linked histories, changing terminologies and the still unresolved and politically charged question of what to call all ‘these islands’ together.

The Island of the Painted People?

The earliest recorded place names for the group of islands off the north east European coast are in the works of classical Greek and Roman authors. These islands were on the very far fringes of the known Mediterranean world; where the barbarians’ barbarians lived, a place of mist and mysteries; full of great potential wealth, fantastical creatures and strange peoples. Classical works of geography and history were meant to edify and entertain as much as they were there to inform.

The first report of islands in the far west which can be associated with Britain and Ireland are to be found in Herodotus, the Greek father of history, in the fifth century BCE. Herodotus wrote of islands known as the Cassiterides but of which he had no information beyond their name.1 Herodotus, The Histories, Bk3.115. Cassiterides translates as ‘Tin Islands from the Greek word for tin — kassiteros.

We owe the name of Britain to Pytheas of Massalia, a Greek explorer from present-day Marseille, who travelled to Britain in around 325BCE and recorded the local names of the places he visited. Unfortunately, Pytheas’s writings do not survive but they were widely used as a source by other ancient but desk-bound geographers such as the first-century BCE Greek author Diodorus Siculus who recorded one of the islands names as ‘Pretannike’.2 Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, Bk5.21. Greek Prettanike. In classical Greek and Latin texts, the ‘p’ often turned to a ‘b’ becoming ‘Britannia’.3 Julius Caesar is the earliest recorded writer to use the ‘b’ spelling during his own account of his expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BCE. Caesar, The Gallic Wars, Bk4.20-37; Bk5.2-24. These invasions were important propaganda exercises launched with the intention of further boosting Caesar’s prestige in Rome for subduing peoples on the very far edge of the known world. But the original Greek p-spelling was a rendition of a local Celtic name for either a people living on the island or for the land itself, exactly what is unclear. ‘Pretani’, from which it came from, was a Celtic word that most likely meant ‘the painted people’.4 The Celtic languages on these islands are split into two separate but related families: P-Celtic (Welsh, Cornish and Breton) & Q-Celtic (Irish, Scots Gaelic & Manx). Pretani comes from the P-Celtic line and its longevity can be seen in the modern Welsh word for Britain, Prydain.

Mysterious Albion

‘Albion’ was another name recorded in the classical sources for the island we know as Britain. ‘Albion’ probably predates ‘Pretannia’. Indeed, ‘Albion’ may come from a ‘celticisation’ of a word used for these islands prior to the arrival of Celtic-speaking peoples and most likely derives from the Indo-European root word for hill or hilly, ‘alb-’ ‘albho-‘ for white, probably referring to the white chalk cliffs on Britain’s southern shore.5 Christopher A. Snyder, The Britons (Oxford, 2003), pp. 12-13. Other similarly derived place names include the Alps, Albania, and the Apennines, lending credence to the hill theory though it is not conclusive. Although Albion was often used by classical writers (and others since) as a rhetorical flourish, Britannia won out in general usage probably because after the beginning Roman conquest in 43CE, the province on the island was named ‘Britannia’.

Some examples of classical writers:

• Strabo (1st century BCE): “Brettanike” 6 Strabo, Geography, Bk1.4.3, Bk4.2.1; Bk.4.4.1. Brettanike. Strabo had a very low opinion of Pytheas, calling him an “archfalsifier” (pseudistatos).

• Pliny the Elder (1st century CE): “Britannia insula” 7 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Bk4.102. “Ex adverso huius situs Britannia insula clara Graecis nostrisque monimentis”

• Marcian of Heraclea (4th century CE): “the Prettanic Islands” 8 Marcian of Heraclea, Periplus Maris Exteri, Bk1. Proeemium; Bk1.8, Bk2.Proeemium, Bk2.24, Bk2.27, Bk2.40, Bk2. 41-46. Hai Prettanikai nesoi.

What made Britain ‘Great’?

The word ‘Great’ becoming attached to ‘Britain’ comes from medieval practice and not the classical authors. This became a common practice in the twelfth century to distinguish the island of Britannia maior (Greater Britain) from Britannia minor (Lesser Britain), the other medieval Britain Brittany.9 David N. Dumville, ‘‘Celtic’ visions of England’ in Andrew Galloway (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Culture (Cambridge, 2011), p. 126. Brittany gained its name from the British migrants who moved there in the post-Roman period.

Brutus of Troy and Britain

The twelfth century was a period of great historical introspection with numerous writers reflecting on the past of Britain and its various peoples’ pasts. The most influential contribution to this debate was Geoffrey of Monmouth, one of the most successful mytho-historians, with his History of the Kings of Britain.10 Geoffrey of Monmouth, The history of the kings of Britain: an edition and translation of De Gestis Britonum (Historia Regum Britanniae), M.D. Reeve (ed.) and N. Wright (trans.), (Woodbridge, 2007). Geoffrey of Monmouth distinguished between Britannia Insula or Britannia meaning Britain and Britannia minor, lesser Britain for Brittany, 92.88, 96.235, 97.245 Alongside his famed contribution to what became Arthurian legend, Geoffrey provided a popular origin story for the name ‘Britain’. Geoffrey wrote of a ‘Brutus of Troy’, a grandson of Aeneas, a Trojan hero and ancestor of the Roman people, who came to Albion, slew the giants who lived here and founded a kingdom, which took its name from him, Britain. Although this tale lacked any historical basis, this was the most popularly believed explanation until well into the sixteenth century at least.11 Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins (Oxford, 2013), pp. 8-16.

From Geographical Expression to Political Reality

The accession of James VI of Scotland to the English and Irish thrones in 1603 created the impetus for widespread use of ‘Great Britain’ as both a geographical expression and as a political entity. England and Scotland remained separate kingdoms but James VI and (now) I decided that at least he could combine the two together in his title, so called himself ‘King of Great Britain’.12 James VI & I, ‘By the King. A proclamation concerning the Kings Majesties Stile, of King of Great Britaine, & C. [Westminster 20 October 1604]’ in J.F. Larkin & P.L Hughes (eds.), Stuart Royal Proclamations. Vol. 1, Royal proclamations of King James I, 1603-1625 (Oxford, 1973), no. 45; Jenny Wormald, ‘James VI and I (1566-1625)’, Oxford Dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004). The use of ‘Great Britain’ to refer to the whole island of Britain, was strengthened by the Act of Union (1707), which created a new united ‘Kingdom of Great Britain’.13 Article I of the Act of Union (1707) The ‘Kingdom of Great Britain’ became the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’ after the Act of Union (1801) between ‘Great Britain’ and the ‘Kingdom of Ireland’.14 First Article of the Union with Ireland Act (1800) As with many other states, a term that had enjoyed a largely literary, aspirational and geographic expression, now became a ‘political’ reality. After the Irish Free State’s creation in 1922, the name changed to the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’. This kept the distinction between what was geographically ‘Great Britain’ and ‘Northern Ireland’ but which remained one political union.

The ever-changing meaning of Britain

Britain may be an ancient name but its meaning has changed over time for the inhabitants and newcomers to these islands. This continuous renewal and reinterpretation of the meaning and understanding of the name is a major reason for its survival. The name of Britain has been a resource from which the various peoples have used to make and remake new, diverse and dynamic identities over centuries of lived history. It has survived because it has proved useful. However, this constant reuse of a name has preserved an ancient Celtic dialectal name transliterated by an ancient Greek explorer from the south of France over two millennia ago.

NOTES

-

Herodotus, The Histories, Bk3.115. Cassiterides translates as ‘Tin Islands from the Greek word for tin — kassiteros.

-

Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, Bk5.21. Greek Prettanike.

-

Julius Caesar is the earliest recorded writer to use the ‘b’ spelling during his own account of his expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BCE. Caesar, The Gallic Wars, Bk4.20-37; Bk5.2-24. These invasions were important propaganda exercises launched with the intention of further boosting Caesar’s prestige in Rome for subduing peoples on the very far edge of the known world.

-

The Celtic languages on these islands are split into two separate but related families: P-Celtic (Welsh, Cornish and Breton) & Q-Celtic (Irish, Scots Gaelic & Manx). Pretani comes from the P-Celtic line and its longevity can be seen in the modern Welsh word for Britain, Prydain.

-

Christopher A. Snyder, The Britons (Oxford, 2003), pp. 12-13.

-

Strabo, Geography, Bk1.4.3, Bk4.2.1; Bk.4.4.1. Brettanike. Strabo had a very low opinion of Pytheas, calling him an “archfalsifier” (pseudistatos).

-

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Bk4.102. “Ex adverso huius situs Britannia insula clara Graecis nostrisque monimentis”

-

Marcian of Heraclea, Periplus Maris Exteri, Bk1. Proeemium; Bk1.8, Bk2.Proeemium, Bk2.24, Bk2.27, Bk2.40, Bk2. 41-46. Hai Prettanikai nesoi.

-

David N. Dumville, ‘‘Celtic’ visions of England’ in Andrew Galloway (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Culture (Cambridge, 2011), p. 126.

-

Geoffrey of Monmouth, The history of the kings of Britain: an edition and translation of De Gestis Britonum (Historia Regum Britanniae), M.D. Reeve (ed.) and N. Wright (trans.), (Woodbridge, 2007). Geoffrey of Monmouth distinguished between Britannia Insula or Britannia meaning Britain and Britannia minor, lesser Britain for Brittany, 92.88, 96.235, 97.245

-

Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins (Oxford, 2013), pp. 8-16.

-

James VI & I, ‘By the King. A proclamation concerning the Kings Majesties Stile, of King of Great Britaine, & C. [Westminster 20 October 1604]’ in J.F. Larkin & P.L Hughes (eds.), Stuart Royal Proclamations. Vol. 1, Royal proclamations of King James I, 1603-1625 (Oxford, 1973), no. 45; Jenny Wormald, ‘James VI and I (1566-1625)’, Oxford Dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004).

-

Article I of the Act of Union (1707)

- First Article of the Union with Ireland Act (1800)

Suggested Additional Reading

Linda Colley, Britons: forging the nation (rev. ed. London, 2009).

Linda Colley, Acts of Union and Disunion (London 2014).

Barry Cunliffe, The extraordinary voyage of Pytheas the Greek (London, 2002).

Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins (Oxford, 2013).

Christopher A. Snyder, The Britons (Oxford, 2003).

Please log in to create your comment

Server Costs Fundraiser 2023

Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate to our server cost fundraiser 2023, so that we can produce more history articles, videos and translations. With your support millions of people learn about history entirely for free, every month.

$12119 / $21000

Definition

Listen to this article

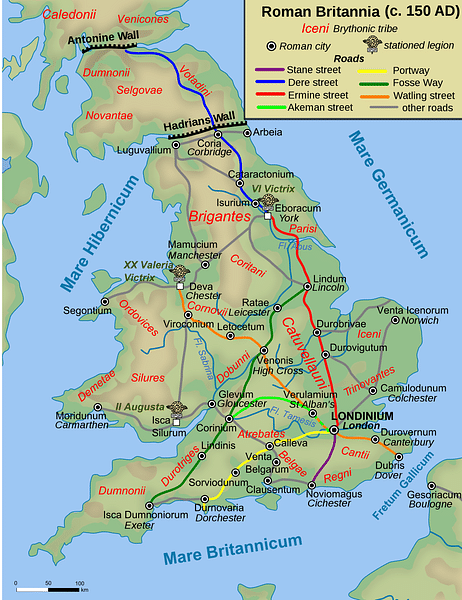

Map of Roman Britain, 150 AD Andrei nacu (Public Domain)

Britain (or more accurately, Great Britain) is the name of the largest of the British Isles, which lie off the northwest coast of continental Europe. The name is probably Celtic and derives from a word meaning ‘white’; this is usually assumed to be a reference to the famous white cliffs of Dover, which any new arrival to the country by sea can hardly miss. The first mention of the island was by the Greek navigator Pytheas, who explored the island’s coastline, c. 325 BCE.

During the early Neolithic Age (c. 4400 BCE – c. 3300 BCE), many long barrows were constructed on the island, many of which can still be seen today. In the late Neolithic (c. 2900 BCE – c. 2200 BCE), large stone circles called henges appeared, the most famous of which is Stonehenge.

Before Roman occupation, the island was inhabited by a diverse number of tribes, collectively known as Britons.

Roman Britain

Before Roman occupation the island was inhabited by a diverse number of tribes that are generally believed to be of Celtic origin, collectively known as Britons. The Romans knew the island as Britannia.

It enters recorded history in the military reports of Julius Caesar, who crossed to the island from Gaul (France) in both 55 and 54 BCE. The Romans invaded the island in 43 CE, on the orders of emperor Claudius, who crossed over to oversee the entry of his general, Aulus Plautius, into Camulodunum (Colchester), the capital of the most warlike tribe, the Catuvellauni. Plautius invaded with four legions and auxiliary troops, an army amounting to some 40,000.

Due to the survival of the Agricola, a biography of his father-in-law written by the historian Tacitus (c. 105 CE), we know much about the first four decades of Roman occupation, but literary evidence is scarce thereafter; fortunately, there is plentiful if occasionally mystifying archaeological evidence. Subsequent Roman emperors made forays into Scotland, although northern Britain was never conquered; they left behind the great fortifications, Hadrian’s Wall (c. 120 CE) and the Antonine Wall (142 -155 CE), much of which can still be visited today. Britain was always heavily fortified and was a base from which Roman governors occasionally made attempts to seize power in the Empire (Clodius Albinus in 196 CE, Constantine in 306 CE).

Hadrian’s Wall Gate phault (CC BY)

At the end of the 4th century CE, the Roman presence in Britain was threatened by «barbarian» forces. The Picts (from present-day Scotland) and the Scoti (from Ireland) were raiding the coast, while the Saxons and the Angles from northern Germany were invading southern and eastern Britain. By 410 CE the Roman army had withdrawn. After struggles with the Britons, the Angles and the Saxons emerged as victors and established themselves as rulers in much of Britain during the Dark Ages (c. 450 — c. 800 CE).

YouTube

Follow us on YouTube!

Did you like this definition?

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

About the Author

Teacher of Classics

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Become a Member

Donate

Recommended Books

-

Written by Oliver, Neil, published by Phoenix (2012)

$17.99

-

Written by Ordnance Survey, published by Ordnance Survey (2016)

$12.72

-

Written by Abram, David R. & Roberts, Alice, published by Thames & Hudson (2022)

$35.76

-

Written by Bishop, M.C., published by Pen and Sword Military (2019)

$29.95

-

Written by Salway, Peter, published by Oxford University Press (2015)

$11.95

Cite This Work

APA Style

Walsh, T. (2011, April 28). Ancient Britain.

World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/britain/

Chicago Style

Walsh, Terry. «Ancient Britain.»

World History Encyclopedia. Last modified April 28, 2011.

https://www.worldhistory.org/britain/.

MLA Style

Walsh, Terry. «Ancient Britain.»

World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 28 Apr 2011. Web. 12 Apr 2023.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Terry Walsh, published on 28 April 2011. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Learn about this topic in these articles:

Assorted References

- major reference

-

In United Kingdom: Ancient Britain

…late in the Mesolithic Period, Britain formed part of the continental landmass and was easily accessible to migrating hunters. The cutting of the land bridge, about 6000–5000 bce, had important effects: migration became more difficult and remained for long impossible to large numbers. Thus Britain developed insular characteristics, absorbing and…

Read More

-

- burial rites

-

In burial mound

The burial chambers in Britain, unlike those of similar structures in the Mediterranean region, were seldom excavated in the soil beneath the barrow but were enclosed within the structure itself.

Read More

-

In history of Europe: Social change

…prevail everywhere, however, and in Britain, for instance, the 3rd millennium saw the construction of massive ceremonial monuments such as Avebury and Stonehenge, before the introduction of individual burial rites at the end of the millennium.

Read More

-

In history of Europe: Prestige and status

In Britain the sequence is even more complicated and shows both a strong indigenous tradition and clear local influences from western Europe. The greatest complication is the disappearance of formal burials in this area in the Late Bronze Age; they did not reappear before the last…

Read More

-

- calligraphy style

-

In calligraphy: The Anglo-Celtic and other national styles (5th to 13th century)

…such as the province of Britain, responded strongly to this opportunity and at the same time were able to conserve important elements of Roman civilization. Ireland, which was never under occupation by the legions, offered during Europe’s darkest age comparative peace and shelter for the development of the richest and…

Read More

-

- coins and coinage

-

In coin: Ancient Britain

The earliest coinage of Britain consisted of small, cast pieces of speculum, a brittle bronze alloy with 20 percent tin. These coins copied the bronze of Massilia (Marseille) of the 2nd century bce and circulated, mainly in southeastern Britain, early in the 1st century…

Read More

-

- football

-

In football

That British folk football did not become appreciably more civilized with the arrival of the Renaissance is suggested by Sir Thomas Elyot’s condemnation in The Governour (1537). He lamented the games “beastely fury, and extreme violence.” Even James I, who defended the legitimacy of traditional English…

Read More

-

- invasion by Germanic tribes

-

In history of Europe: The Germans and Huns

…Jutland Peninsula crossed over to Britain. The Franks and the Alemanni finally established themselves on the far side of the Rhine, the Burgundians extended along the Rhône valley, and the Visigoths took possession of nearly all of Spain. In 476 the Germanic soldiery proclaimed Odoacer, a barbarian general, as king…

Read More

-

- Latin language

-

In Latin language

…20th century suggested that in Britain, for instance, Romanization was more widespread and more profound than hitherto suspected and that well-to-do Britons in the colonized region were thoroughly imbued with Roman values. How far these trickled down to the common people is difficult to tell. Because Latin died out in…

Read More

-

- metallurgy

-

In metallurgy: Iron

…was fairly widespread in Great Britain at the time of the Roman invasion in 55 bce. In Asia iron was also known in ancient times, in China by about 700 bce.

Read More

-

- Neolithic Period

-

In history of Europe: The adoption of farming

In Britain and Ireland, forest clearance as early as 4700 bce may represent the beginnings of agriculture, but there is little evidence for settlements or monuments before 4000 bce, and hunting-and-gathering economies survived in places. The construction of large communal tombs and defended enclosures from 4000…

Read More

-

- Roman Empire control

-

In ancient Rome: The succession

…46) and, more important, annexing Britain. Conquest of Britain began in 43, Claudius himself participating in the campaign; the southeast was soon overrun, a colonia established at Camulodunum (Colchester) and a municipium at Verulamium (St. Albans), while Londinium (London) burgeoned into an important entrepôt. Claudius also promoted Romanization, especially in…

Read More

-

- Roman limes

- In limes

The limites in Great Britain were Hadrian’s Wall, built of stone between the Rivers Tyne and Solway and, farther north, the turf wall of Antoninus Pius between the Rivers Forth and Clyde.

Read More

- In limes

- Roman road system

-

In Roman road system

In Britain the purely strategic roads following the conquest were supplemented by a network radiating from London. In Spain, on the contrary, the topography of the country dictated a system of main roads around the periphery of the peninsula, with secondary roads developed into the central…

Read More

-

- Scotland

-

In Scotland: Roman penetration

…Agricola, the Roman governor of Britain from 77 to 84 ce, was the first Roman general to operate extensively in Scotland. He defeated the native population at Mons Graupius, possibly in Banffshire, probably in 84 ce. In the following year he was recalled, and his policy of containing the hostile…

Read More

-

- Tertiary Period

-

In Europe: Cenozoic igneous provinces

… extrusions and intrusions in northwestern Britain. In Northern Ireland and northwestern Scotland, basaltic lava flows (e.g., in the Giant’s Causeway and the northern part of the isle of Skye) are associated with northwest–southeast-trending basaltic dikes and many plutonic (igneous rock formed deep within the crust) complexes, which are probably the…

Read More

-

- Welsh kingdoms

-

In Wales: The prehistory of Wales

…against the broader background of British prehistory, for the material remains of the period 3500–1000 bce especially funerary monuments, provide regional manifestations of features characteristic of Britain as a whole. The Celtic origins of Britain, probably to be sought in a gradual process within the last millennium bce, are a…

Read More

-

population and demography

- Belgae

- In Belgae

…band of Belgae crossed to Britain. After further Gallic victories (54–51 bc) by Caesar, other settlers took refuge across the Channel, and Belgic culture spread to most of lowland Britain. The three most important Belgic kingdoms, identified by their coinage, were centred at Colchester, St. Albans, and Silchester. The chief…

Read More

- In Belgae

- Iceni

- In Iceni

Britain, a tribe that occupied the territory of present-day Norfolk and Suffolk and, under its queen Boudicca (Boadicea), revolted against Roman rule.

Read More

- In Iceni

religion

- canon law

-

In canon law: Development of canon law in the West

…by the church in the British Isles. The church there was concentrated around heavily populated monasteries, and discipline outside them was maintained by means of a new penitential practice. In place of ancient canons about public penance, the clergy and monks used libri poenitentiales (“penitential books”), which contained detailed catalogs…

Read More

-

- Christianity

-

In Anglicanism: Christianity in England

…began to be practiced in England not later than the early 3rd century. By the 4th century the church was established well enough to send three British bishops—of Londinium (London), Eboracum (York), and Lindum (Lincoln)—to the Council of Arles (in present-day France) in 314. In the 5th century, after the…

Read More

-

- taverns

-

In tavern

The hostelries of Roman England were derived from the cauponae and the tabernae of Rome itself. These were followed by alehouses, which were run by women (alewives) and marked by a broom stuck out above the door. The English inns of the Middle Ages were sanctuaries of wayfaring…

Read More

-

role of

- Agricola

-

In Gnaeus Julius Agricola

…celebrated for his conquests in Britain. His life is set forth by his son-in-law, the historian Tacitus.

Read More

-

- Caesar

-

In Julius Caesar: The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul

…crossed the Channel to raid Britain. In 54 bce he raided Britain again and subdued a serious revolt in northeastern Gaul. In 53 bce he subdued further revolts in Gaul and bridged the Rhine again for a second raid.

Read More

-

- Carausius

-

In Diocletian: Reorganization of the empire of Diocletian

…fought for the empire in Britain against the Frankish and Saxon pirates, revolted and named himself emperor in Britain in 287. Carausius reigned in Britain for nearly 10 years until Constantius I Chlorus succeeded in returning Britain to the empire in 296. Scarcely had troubles in Mauretania and in the…

Read More

-

- Claudius I

-

In Claudius: Emperor and colonizer

Claudius’s decision to invade Britain (43) and his personal appearance at the climax of the expedition, the crossing of the Thames and the capture of Camulodunum (Colchester), were prompted by his need of popularity and glory. But concern with the anti-Roman influence of the Druid priesthood, which he tried…

Read More

-

- Hadrian

-

In Hadrian: Policies as emperor

In northern Britain he initiated the construction of the tremendous frontier wall that bears his name from Wallsend-on-Tyne to Bowness-on-Solway. At Lambaesis, in Algeria, his rigorous inspection of the troops and his severe standards of discipline can be seen in a long inscription preserving an address he…

Read More

-

The United Kingdom, also known as Britain or the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, is a European region with a long and storied history. The first modern humans (Homo sapiens) arrived in the region during the Ice Age (about 35,000 to 10,000 years ago), when the sea levels were lower and Britain was connected to the European mainland. It is these people who built the ancient megalithic monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury.

Between 1,500 and 500 BCE, Celtic tribes migrated from Central Europe and France to Britain and mixed with the indigenous inhabitants, creating a new culture slightly distinct from the Continental Celtic one. This came to be known as the Bronze Age.

The Romans controlled most of present-day England and Wales, and founded a large number of cities that still exist today. London, York, St Albans, Bath, Exeter, Lincoln, Leicester, Worcester, Gloucester, Chichester, Winchester, Colchester, Manchester, Chester, and Lancaster were all Roman towns, as were all the cities with names now ending in -chester, -cester or -caster, which derive from the Latin word castrum, meaning «fortification.”

History of the United Kingdom: The Anglo-Saxons

In the 5 century, the Romans progressively abandoned Britannia, as their Empire was falling apart and legions were needed to protect Rome.

With the Romans vacated, the Celtic tribes started warring with each other again, and one of the local chieftains had the (not so smart) idea to request help from some of the Germanic tribes from the North of present-day Germany and South of Denmark. These were the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, who arrived in the 5th and 6th centuries.

When the fighting ceased, the Germanic tribes did not, as expected by the Celts, return to their homeland. In fact, they felt strong enough to seize the whole of the country for themselves, which they ultimately did, pushing back all the Celtic tribes to Wales and Cornwall, and founding their respective kingdoms of Kent (the Jutes), Essex, Sussex and Wessex (the Saxons), and further northeast, the kingdoms of Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria (the Angles). These 7 kingdoms, which ruled over the United Kingdom from about 500 to 850 AD, were later known as the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy.

History of the United Kingdom: The Vikings

In the latter half of the 9 century, the Norse people from Scandinavia began to invade Europe, with the Swedes putting down roots in Eastern Europe and the Danes creating problems throughout Western Europe, as far as North Africa.

Towards the dawn of the 10 century, the Danes invaded the Northeast of England, from Northumerland to East Anglia, and founded a new kingdom known as the Danelaw. Another group of Danes managed to take Paris, and obtain a grant of land from the King of France in 911. This area became the Duchy of Normandy, and its inhabitants were the Normans (from ‘North Men’ or ‘Norsemen’, another term for ‘Viking’).

History of the United Kingdom: The Normans

During that same period, the Kings of Wessex had resisted, and eventually vanquished the Danes in England in the 10th century. However, the powerful Canute the Great (995-1035), king of the newly unified Denmark and Norway and overlord of Schleswig and Pomerania, led two other invasions on England in 1013 and 1015, and became king of England in 1016, after crushing the Anglo-Saxon King, Edmund II.

During the 11 century, the Norman King Edward the Confessor (1004-1066) nominated William, Duke of Normandy, as his successor, but upon Edward’s death, Harold Godwinson, the powerful Earl of Wessex, crowned himself king. William refused to acknowledge Harold as King and invaded England with 12,000 soldiers in 1066. King Harold was killed at the battle of Hastings and William the Conqueror become William I of England.

The Norman rulers kept their possessions in France, and even extended them to most of Western France (Brittany, Aquitaine…). French became the official language of England, and remained that way until 1362, a short time after the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War with France. English nevertheless remained the language of the populace, and the fusion of English (a mixture of Anglo-Saxon and Norse languages) with French and Latin (used by the clergy) slowly evolved into the modern English we know today.

History of the United Kingdom: 12 and 13 Centuries

The English royals that followed William I had the infamous habit to contend for the throne. William’s son, William II was killed while hunting, although it is widely believed that he was in fact murdered so that William’s second son, Henry, could become king. Henry I’s succession was also fraught with agitation, with his daughter Matilda and her cousin Stephen (grandson of William I) starting a civil war for the throne. Although Stephen eventually won, it was ultimately Matilda’s son that succeeded to the throne, becoming Henry II (1133-1189). It is under Henry II that the University of Oxford was established.

The two children of Henry II—Richard I «Lionhearted» and John Lackland—also battled for the throne. The oldest son, Richard, eventually succeeded to the throne, but because he was rarely in England, and instead off defending his French possessions or fighting the infidels in the Holy Land, his brother John Lackland usurped the throne and started another civil war.

John’s grandson, Edward I «Longshanks» (1239-1307) spent most of his 35-year reign fighting wars, including one against the Scots, led by William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. With the help of these men, the Scots were able to resist, as immortalized in the Hollywood movie Braveheart.

History of the United Kingdom: 14 and 15 Centuries

After a brief rule by Edward Longshanks son, his grandson, Edward III (1312-1377), succeeded to the throne at the age of 15 and reigned for 50 years. His reign was marked by the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1416) and deadly epidemics of bubonic plague («Black Death»), which killed one third of England’s (and Europe’s) population.

Edward III was often off fighting in France, leaving his third son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, to run the government. Later, John’s son, Henry Bolingbroke, would be proclaimed King Henry IV (1367-1413).

Henry V (1387-1422) famously defeated the French at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, but his pious and peace-loving son Henry VI (1421-1471), who inherited the throne at age one, was to have a much more troubled reign. The regent lost most of England’s possessions in France to a 17-year old girl (Joan of Arc) and in 1455 the Wars of the Roses broke out. This civil war opposed the House of Lancaster (the Red Rose, supporters of Henry VI) to the House of York (the White Rose, supporters of Edward IV). The Yorks argued that the crown should have passed to Edward III’ second son, Lionel of Antwerp, rather than to the Lancaster descendant of John of Gaunt.

Edward IV’s son, Edward V, only reigned for one year, before being locked in the Tower of London by his evil uncle, Richard III (1452-1485). In 1485, Henry Tudor (1457-1509), the half-brother of Henry VI, defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field and became Henry VII, founder of the House of Tudor.

Following Henry (Tudor) VII to the throne was perhaps England’s most famous and historically significant ruler, the magnificent Henry VIII (1491-1547).

History of the United Kingdom: 16 Century

In 1533, Henry VIII divorced Catherine of Aragon to remarry Anne Boleyn, causing the Pope to excommunicate him from the church. As a result, Henry proclaimed himself head of the Church of England. He dissolved all the monasteries in the country (1536-1540) and nationalized them, becoming immensely rich in the process.

Henry VIII was the last English king to claim the title of King of France, as he lost his last possession there, the port of Calais (although he tried to recover it, taking Tournai for a few years, the only town in present-day Belgium to have been under English rule).

It was also under Henry VIII that England started exploring the globe and trading outside Europe, although this would only develop to colonial proportions under his daughters, Mary I and especially Elizabeth I.

Upon the death of Henry VIII, his 10-year old son, Edward VI, inherited the throne. Six years later, however, Edward VI died and was succeeded by Henry’s elder half-daughter Mary. Mary I (1516-1558), a staunch Catholic, intended to restore Roman Catholicism to England, executing over 300 religious dissenters in her 5-year reign (which owned her the nickname of Bloody Mary). She married the powerful King Philip II of Spain, who also ruled over the Netherlands, the Spanish Americas and the Philippines (named after him), and was the champion of the Counterreformation. Mary died childless of ovarian cancer in 1558, and her half-sister Elizabeth ascended to the throne.

The great Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) saw the first golden age of England. It was an age of great navigators like Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh, and an age of enlightenment with the philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626), and playwrights such as Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) and William Shakespeare (1564-1616).

Her reign was also marked by conflicts with France and Scotland, and later Spain and Ireland. She never married, and when Mary Stuart tried and failed to take over the throne of England, Elizabeth kept her imprisoned for 19 years before finally signing her act of execution.

Elizabeth died in 1603, and ironically, Mary Stuart’s son, James VI of Scotland, succeeded Elizabeth as King James I of England—thus creating the United Kingdom.

History of the United Kingdom: 17 Century

James I (1566-1625), a Protestant, aimed at improving relations with the Catholic Church. But 2 years after he was crowned, a group of Catholic extremists, led by Guy Fawkes, attempted to place a bomb at the parliament’s state opening, hoping to eliminate all the Protestant aristocracy in one fell swoop. However, the conspirators were betrayed by one of their own just hours before the plan’s enactment. The failure of the Gunpowder Plot, as it is known, is still celebrated throughout Britain on Guy Fawkes’ night (5th November), with fireworks and bonfires burning effigies of the conspirators’ leader.

After this incident, the divide between Catholics and Protestant worsened. James’s successor Charles I (1600-1649) was eager to unify Britain and Ireland. His policies, however, were unpopular among the populace, and his totalitarian handling of the Parliament eventually culminated in the English Civil War (1642-1651).

Charles was beheaded, and the puritan Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) ruled the country as a dictator from 1649 to his death. He was briefly succeeded by his son Richard at the head of the Protectorate, but his political inability prompted the Parliament to restore the monarchy in 1660, calling in Charles I’ exiled son, Charles II (1630-1685).

Charles II, known as the “Merry Monarch,” was much more adept than his father at handling Parliament, although every bit as ruthless with other matters. During his reign, the Whig and Tory parties were created, and the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam became English and was renamed New York, after Charles’ brother, James, Duke of York (and later James II).

Charles II was the patron of the arts and science, helping to found the Royal Society and sponsoring some of England’s proudest architecture. Charles also acquired Bombay and Tangiers through his Portuguese wife, thus laying the foundation for the British Empire.

Although Charles produced countless illegitimate children, his wife couldn’t bear an heir, and when he died in 1685 the throne passed to his Catholic and unpopular brother James.

James II’s unpopularity led to his quick removal from power in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He was succeeded by his Protestant daughter Mary, who was married to his equally Protestant nephew, William of Orange.

The new ruling couple became known as the «Grand Alliance,» and parliament ratified a bill stating that all kings or queens would have to be Protestant from that point forward. After Mary’s death in 1694, and then William’s in 1702, James’s second daughter, Anne, ascended to the throne. In 1707, the Act of Union joined the Scottish and the English Parliaments thus creating the single Kingdom of Great Britain and centralizing political power in London. Anne died heirless in 1714, and a distant German cousin, George of Hanover, was called to rule over the UK.

History of the United Kingdom: 18 Century and the House of Hanover

George II (1683-1760) was also German born. He was a powerful ruler, and the last British monarch to personally lead his troops into battle. The British Empire expanded considerably during his reign; a reign that saw notable changes, including the replacement of the Julian Calendar by the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, and moving the date of the New Year from March 25 to January 1.

George III was the first Hanoverian king to be born in England. He had one of the most troubled and interesting reigns in British history. He ascended to the throne during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) opposing almost all the major Western powers in two teams, chiefly British against French, and ended in a de facto victory for the UK, which acquired New France (Quebec), Florida, and most of French India in the process.

Thirteen years later, the American War of Independence (1776-1782) broke out and in 1782 13 American colonies were finally granted their independence, forming the United States of America. Seven years later, the French Revolution broke out, and Louis XVI was guillotined. George III suffered from a hereditary disease known as porphyria, and his mental health seriously deteriorated from 1788. In 1800, the Act of Union merged the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland.

The United Kingdom during this time also had to face the ambitions of Napoleon, who desired to conquer the whole of Europe. Admiral Nelson’s naval victory at Traflagar in 1805, along with Wellington’s decisive victory at Waterloo, saved the UK and further reinforced its international position. The 19th century would be dominated by the British Empire, spreading on all five continents, from Canada and the Caribbean to Australia and New Zealand, via Africa, India and South-East Asia.

History of the United Kingdom: 19 Century

In 1837, then king William IV died of liver disease and the throne passed to the next in line, his 18-year old niece Victoria (1819-1901), although she did not inherit the Kingdom of Hanover, where the Salic Law forbid women to rule.

Victoria didn’t expect to become queen, and being unmarried and inexperienced in politics she had to rely on her Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne (1779-1848). She finally got married to her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (1819-1861), and both were respectively niece and nephew of the first King of the Belgians, Leopold I (of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha).

Britain asserted its domination on virtually every part of the globe during the 19 century, resulting in a number of wars, including the Opium Wars (1839-42 & 1856-60) with Qing China and the Boer Wars (1880-81 & 1899-1902) with the Dutch-speaking settlers of South Africa. In 1854, the United Kingdom was brought into the Crimean War (1854-56) on the side of the Ottoman Empire and against Russia. One of the best known figures of that war was Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), who fought for the improvement of women’s conditions and pioneered modern nursing.

The latter years of Victoria’s reign were dominated by two influential Prime Ministers, Benjamin Disraeli (1808-1881) and his rival William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898). The former was the favorite of the Queen, while Gladstone, a liberal, was often at odds with both Victoria and Disraeli. However, the strong party support for Gladstone kept him in power for a total of 14 years between 1868 and 1894. He is credited with legalizing trade unions, and advocating for both universal education and suffrage.

Queen Victoria was to have the longest reign of any British monarch (64 years), but also the most glorious, as she ruled over 40% of the globe and a quarter of the world’s population.

History of the United Kingdom: 20 Century (Two World Wars)

Victoria’s numerous children married into many different European Royal families, The alliances between these related monarchs escalated into the Great War –WWI—from 1914-1918. It began when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo, and Austria declared war on Serbia, which in turn was allied to France, Russia and the UK. The First World War left over 9 million dead (including nearly 1 million Britons) throughout Europe, and financially ruined most of the countries involved. The monarchies in Germany, Austria, Russia and the Ottoman Empire all fell, and the map of central and Eastern Europe was completely redesigned.

After World War I, the Labor Party was created in Britain. The General Strike of 1926 and the worsening economy led to radical political changes, including one in which women were finally granted the same universal suffrage as men in 1928.

In 1936, Edward VIII (1894-1972) succeeded to the throne, but abdicated the same year to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice divorced American woman. His brother then unexpectedly became George VI (1895-1952) after the scandal.

Nazi Germany was becoming more menacing as Hitler grew more powerful and aggressive. Finally, Britain and France were forced to declare war on Germany after the invasion of Poland in September 1939, marking the beginning of World War II. The popular and charismatic Winston Churchill (1874-1965) became the war-time Prime Minister in 1940 and his speeches encouraged the British to fight off the attempted German invasion. In one of his most patriotic speeches before the Battle of Britain (1940), Churchill address the British people with «We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.» And indeed, Britain did not surrender.

Following World War II, the United Kingdom was bankrupt and in ruins. The British Empire was dismantled little by little, first granting independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, then to the other Asian, African and Caribbean colonies in the 1950’s and 60’s. Most of these ex-colonies formed the British Commonwealth, now known as the Commonwealth of Nations. 53 states are now members of the Commonwealth, accounting for 1.8 billion people (about 30% of the global population) and about 25% of the world’s land area.

In 1952, the current queen of England, Elizabeth II, ascended to the throne at the age of 26. The 1960s saw the dawn of pop and rock music, with bands like the Beatles, Pink Floyd, and the Rolling Stones rising to prominence, and the Hippie subculture developing.

The 1970’s brought the oil crisis and the collapse of British industry. Conservative Prime minister Margaret Thatcher (b. 1925) was elected in 1979 and served until 1990. Among other accomplishments, she privatized the railways and shut down inefficient factories, but she also increased the gap between the rich and the poor by scaling back social security. Her methods were so harsh that she was nicknamed the “Iron Lady.”

Thatcher was succeeded in her party by the unpopular John Major, but in 1997, the «New Labor» party came back to power with the appointment of Tony Blair (b. 1953). Blair’s liberal policies and unwavering support for neo-conservative US President George W. Bush (especially regarding the invasion of Iraq in 2003) disappointed many Leftists, who really saw in Blair but a Rightist in disguise. Regardless, Blair has impressed many dissenters with his intelligence and remarkable skills as an orator and negotiator.

Today, the English economy relies heavily on services and, like the rest of the world, is in the process of beginning to rebuild after the global economic recession of 2008. The main industries in the country are travel, education, prestigious automobiles and tourism.