A book is a medium for recording information in the form of writing or images, typically composed of many pages (made of papyrus, parchment, vellum, or paper) bound together and protected by a cover.[1] The technical term for this physical arrangement is codex (plural, codices). In the history of hand-held physical supports for extended written compositions or records, the codex replaces its predecessor, the scroll. A single sheet in a codex is a leaf and each side of a leaf is a page.

As an intellectual object, a book is prototypically a composition of such great length that it takes a considerable investment of time to compose and still considered as an investment of time to read. In a restricted sense, a book is a self-sufficient section or part of a longer composition, a usage reflecting that, in antiquity, long works had to be written on several scrolls and each scroll had to be identified by the book it contained. Each part of Aristotle’s Physics is called a book. In an unrestricted sense, a book is the compositional whole of which such sections, whether called books or chapters or parts, are parts.

The intellectual content in a physical book need not be a composition, nor even be called a book. Books can consist only of drawings, engravings or photographs, crossword puzzles or cut-out dolls. In a physical book, the pages can be left blank or can feature an abstract set of lines to support entries, such as in an account book, appointment book, autograph book, notebook, diary or sketchbook. Some physical books are made with pages thick and sturdy enough to support other physical objects, like a scrapbook or photograph album. Books may be distributed in electronic form as ebooks and other formats.

Although in ordinary academic parlance a monograph is understood to be a specialist academic work, rather than a reference work on a scholarly subject, in library and information science monograph denotes more broadly any non-serial publication complete in one volume (book) or a finite number of volumes (even a novel like Proust’s seven-volume In Search of Lost Time), in contrast to serial publications like a magazine, journal or newspaper. An avid reader or collector of books is a bibliophile or, colloquially, «bookworm». Books are traded at both regular stores and specialized bookstores, and people can read borrowed books, often for free, at libraries. Google has estimated that by 2010, approximately 130,000,000 titles had been published.[2]

In some wealthier nations, the sale of printed books has decreased because of the increased usage of ebooks.[3] Although in most countries printed books continue to outsell their digital counterparts due to many people still preferring to read in a traditional way.[4][5][6][7] The 21st century has also seen a rapid rise in the popularity of audiobooks, which are recordings of books being read aloud.[8]

Etymology

The word book comes from Old English bōc, which in turn comes from the Germanic root *bōk-, cognate to ‘beech’.[9] In Slavic languages like Russian, Bulgarian, Macedonian буква bukva—’letter’ is cognate with ‘beech’. In Russian, Serbian and Macedonian, the word букварь (bukvar’) or буквар (bukvar) refers to a primary school textbook that helps young children master the techniques of reading and writing. It is thus conjectured that the earliest Indo-European writings may have been carved on beech wood.[10] The Latin word codex, meaning a book in the modern sense (bound and with separate leaves), originally meant ‘block of wood’.[11]

History

Antiquity

Fragments of the Instructions of Shuruppak: «Shurrupak gave instructions to his son: Do not buy an ass which brays too much. Do not commit rape upon a man’s daughter, do not announce it to the courtyard. Do not answer back against your father, do not raise a ‘heavy eye.'». From Adab, c. 2600–2500 BCE[12]

When writing systems were created in ancient civilizations, a variety of objects, such as stone, clay, tree bark, metal sheets, and bones, were used for writing; these are studied in epigraphy.

Tablet

A tablet is a physically robust writing medium, suitable for casual transport and writing. Clay tablets were flattened and mostly dry pieces of clay that could be easily carried, and impressed with a stylus. They were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age. Wax tablets were pieces of wood covered in a coating of wax thick enough to record the impressions of a stylus. They were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank.

The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor of modern bound (codex) books.[13] The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.[14]

Scroll

Scrolls can be made from papyrus, a thick paper-like material made by weaving the stems of the papyrus plant, then pounding the woven sheet with a hammer-like tool until it is flattened. Papyrus was used for writing in Ancient Egypt, perhaps as early as the First Dynasty, although the first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC).[15] Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a scroll. Tree bark such as lime and other materials were also used.[16]

According to Herodotus (History 5:58), the Phoenicians brought writing and papyrus to Greece around the 10th or 9th century BC. The Greek word for papyrus as writing material (biblion) and book (biblos) come from the Phoenician port town Byblos, through which papyrus was exported to Greece.[17] From Greek we also derive the word tome (Greek: τόμος), which originally meant a slice or piece and from there began to denote «a roll of papyrus». Tomus was used by the Latins with exactly the same meaning as volumen (see also below the explanation by Isidore of Seville).

Whether made from papyrus, parchment, or paper, scrolls were the dominant form of book in the Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese, Hebrew, and Macedonian cultures. The Romans and Etruscans also made ‘books’ out of folded linen called in Latin Libri lintei, the only extant example of which is the Etruscan Liber Linteus. The more modern codex book format form took over the Roman world by late antiquity, but the scroll format persisted much longer in Asia.

Codex

A Chinese bamboo book meets the modern definition of Codex.

Isidore of Seville (died 636) explained the then-current relation between a codex, book, and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13): «A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches». Modern usage differs.

A codex (in modern usage) is the first information repository that modern people would recognize as a «book»: leaves of uniform size bound in some manner along one edge, and typically held between two covers made of some more robust material. The first written mention of the codex as a form of book is from Martial, in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV at the end of the first century, where he praises its compactness. However, the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use.[18] This change happened gradually during the 3rd and 4th centuries, and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book are several: the format is more economical, as both sides of the writing material can be used; and it is portable, searchable, and easy to conceal. A book is much easier to read, to find a page that you want, and to flip through. A scroll is more awkward to use. The Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan and Judaic texts written on scrolls. In addition, some metal books were made, that required smaller pages of metal, instead of an impossibly long, unbending scroll of metal. A book can also be easily stored in more compact places, or side by side in a tight library or shelf space.

Manuscripts

The fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD saw the decline of the culture of ancient Rome. Papyrus became difficult to obtain due to lack of contact with Egypt, and parchment, which had been used for centuries, became the main writing material. Parchment is a material made from processed animal skin and used—mainly in the past—for writing on.

Parchment is most commonly made of calfskin, sheepskin, or goatskin. It was historically used for writing documents, notes, or the pages of a book. Parchment is limed, scraped and dried under tension. It is not tanned, and is thus different from leather. This makes it more suitable for writing on, but leaves it very reactive to changes in relative humidity and makes it revert to rawhide if overly wet.

Monasteries carried on the Latin writing tradition in the Western Roman Empire. Cassiodorus, in the monastery of Vivarium (established around 540), stressed the importance of copying texts.[19] St. Benedict of Nursia, in his Rule of Saint Benedict (completed around the middle of the 6th century) later also promoted reading.[20] The Rule of Saint Benedict (Ch. XLVIII), which set aside certain times for reading, greatly influenced the monastic culture of the Middle Ages and is one of the reasons why the clergy were the predominant readers of books. The tradition and style of the Roman Empire still dominated, but slowly the peculiar medieval book culture emerged.

The Codex Amiatinus anachronistically depicts the Biblical Ezra with the kind of books used in the 8th century AD.

Before the invention and adoption of the printing press, almost all books were copied by hand, which made books expensive and comparatively rare. Smaller monasteries usually had only a few dozen books, medium-sized perhaps a few hundred. By the 9th century, larger collections held around 500 volumes and even at the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of the Sorbonne held only around 2,000 volumes.[21]

The scriptorium of the monastery was usually located over the chapter house. Artificial light was forbidden for fear it may damage the manuscripts. There were five types of scribes:

- Calligraphers, who dealt in fine book production

- Copyists, who dealt with basic production and correspondence

- Correctors, who collated and compared a finished book with the manuscript from which it had been produced

- Illuminators, who painted illustrations

- Rubricators, who painted in the red letters

Burgundian author and scribe Jean Miélot, from his Miracles de Notre Dame, 15th century

The bookmaking process was long and laborious. The parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after which the text was written by the scribe, who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Finally, the book was bound by the bookbinder.[22]

Different types of ink were known in antiquity, usually prepared from soot and gum, and later also from gall nuts and iron vitriol. This gave writing a brownish black color, but black or brown were not the only colors used. There are texts written in red or even gold, and different colors were used for illumination. For very luxurious manuscripts the whole parchment was colored purple, and the text was written on it with gold or silver (for example, Codex Argenteus).[23]

Irish monks introduced spacing between words in the 7th century. This facilitated reading, as these monks tended to be less familiar with Latin. However, the use of spaces between words did not become commonplace before the 12th century. It has been argued that the use of spacing between words shows the transition from semi-vocalized reading into silent reading.[24]

The first books used parchment or vellum (calfskin) for the pages. The book covers were made of wood and covered with leather. Because dried parchment tends to assume the form it had before processing, the books were fitted with clasps or straps. During the later Middle Ages, when public libraries appeared, up to the 18th century, books were often chained to a bookshelf or a desk to prevent theft. These chained books are called libri catenati.

At first, books were copied mostly in monasteries, one at a time. With the rise of universities in the 13th century, the Manuscript culture of the time led to an increase in the demand for books, and a new system for copying books appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the speed of book production was considerably increased. The system was maintained by secular stationers guilds, which produced both religious and non-religious material.[25]

Judaism has kept the art of the scribe alive up to the present. According to Jewish tradition, the Torah scroll placed in a synagogue must be written by hand on parchment and a printed book would not do, though the congregation may use printed prayer books and printed copies of the Scriptures are used for study outside the synagogue. A sofer «scribe» is a highly respected member of any observant Jewish community.

Middle East

People of various religious (Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, Muslims) and ethnic backgrounds (Syriac, Coptic, Persian, Arab etc.) in the Middle East also produced and bound books in the Islamic Golden Age (mid 8th century to 1258), developing advanced techniques in Islamic calligraphy, miniatures and bookbinding. A number of cities in the medieval Islamic world had book production centers and book markets. Yaqubi (died 897) says that in his time Baghdad had over a hundred booksellers.[26] Book shops were often situated around the town’s principal mosque[27] as in Marrakesh, Morocco, that has a street named Kutubiyyin or book sellers in English and the famous Koutoubia Mosque is named so because of its location in this street.

The medieval Muslim world also used a method of reproducing reliable copies of a book in large quantities known as check reading, in contrast to the traditional method of a single scribe producing only a single copy of a single manuscript. In the check reading method, only «authors could authorize copies, and this was done in public sessions in which the copyist read the copy aloud in the presence of the author, who then certified it as accurate.»[28] With this check-reading system, «an author might produce a dozen or more copies from a single reading,» and with two or more readings, «more than one hundred copies of a single book could easily be produced.»[29] By using as writing material the relatively cheap paper instead of parchment or papyrus the Muslims, in the words of Pedersen «accomplished a feat of crucial significance not only to the history of the Islamic book, but also to the whole world of books».[30]

Wood block printing

Bagh print, a traditional woodblock printing technique that originated in Bagh, Madhya Pradesh, India

In woodblock printing, a relief image of an entire page was carved into blocks of wood, inked, and used to print copies of that page. This method originated in China, in the Han dynasty (before 220 AD), as a method of printing on textiles and later paper, and was widely used throughout East Asia. The oldest dated book printed by this method is The Diamond Sutra (868 AD). The method (called woodcut when used in art) arrived in Europe in the early 14th century. Books (known as block-books), as well as playing-cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by this method. Creating an entire book was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page; and the wood blocks tended to crack, if stored for long. The monks or people who wrote them were paid highly.

Movable type and incunabula

Selected Teachings of Buddhist Sages and Son Masters, the earliest known book printed with movable metal type, printed in Korea, in 1377, Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Chinese inventor Bi Sheng made movable type of earthenware c. 1045, but there are no known surviving examples of his printing. Around 1450, in what is commonly regarded as an independent invention, Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce and more widely available.

A 15th-century Incunable. Notice the blind-tooled cover, corner bosses and clasps.

Early printed books, single sheets and images which were created before 1501 in Europe are known as incunables or incunabula. «A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in AD 330.»[31]

19th century to 21st centuries

Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 19th century. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour,[32] but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour.[citation needed] Monotype and linotype typesetting machines were introduced in the late 19th century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once. There have been numerous improvements in the printing press. As well, the conditions for freedom of the press have been improved through the gradual relaxation of restrictive censorship laws. See also intellectual property, public domain, copyright. In mid-20th century, European book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year.

Throughout the 20th century, libraries have faced an ever-increasing rate of publishing, sometimes called an information explosion. The advent of electronic publishing and the internet means that much new information is not printed in paper books, but is made available online through a digital library, on CD-ROM, in the form of ebooks or other online media. An on-line book is an ebook that is available online through the internet. Though many books are produced digitally, most digital versions are not available to the public, and there is no decline in the rate of paper publishing.[33] There is an effort, however, to convert books that are in the public domain into a digital medium for unlimited redistribution and infinite availability. This effort is spearheaded by Project Gutenberg combined with Distributed Proofreaders. There have also been new developments in the process of publishing books. Technologies such as POD or «print on demand», which make it possible to print as few as one book at a time, have made self-publishing (and vanity publishing) much easier and more affordable. On-demand publishing has allowed publishers, by avoiding the high costs of warehousing, to keep low-selling books in print rather than declaring them out of print.

Indian manuscripts

Goddess Saraswati image dated 132 AD excavated from Kankali tila depicts her holding a manuscript in her left hand represented as a bound and tied palm leaf or birch bark manuscript. In India a bounded manuscript made of birch bark or palm leaf existed side by side since antiquity.[34] The text in palm leaf manuscripts was inscribed with a knife pen on rectangular cut and cured palm leaf sheets; colouring was then applied to the surface and wiped off, leaving the ink in the incised grooves. Each sheet typically had a hole through which a string could pass, and with these the sheets were tied together with a string to bind like a book.

Mesoamerican codices

The codices of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America) had the same form as the European codex, but were instead made with long folded strips of either fig bark (amatl) or plant fibers, often with a layer of whitewash applied before writing. New World codices were written as late as the 16th century (see Maya codices and Aztec codices). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded concertina-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local amatl paper.

Modern manufacturing

The spine of the book is an important aspect in book design, especially in the cover design. When the books are stacked up or stored in a shelf, the details on the spine is the only visible surface that contains the information about the book. In stores, it is the details on the spine that attract a buyer’s attention first.

The methods used for the printing and binding of books continued fundamentally unchanged from the 15th century into the early 20th century. While there was more mechanization, a book printer in 1900 had much in common with Gutenberg. Gutenberg’s invention was the use of movable metal types, assembled into words, lines, and pages and then printed by letterpress to create multiple copies. Modern paper books are printed on papers designed specifically for printed books. Traditionally, book papers are off-white or low-white papers (easier to read), are opaque to minimize the show-through of text from one side of the page to the other and are (usually) made to tighter caliper or thickness specifications, particularly for case-bound books. Different paper qualities are used depending on the type of book: Machine finished coated papers, woodfree uncoated papers, coated fine papers and special fine papers are common paper grades.

Today, the majority of books are printed by offset lithography.[35] When a book is printed, the pages are laid out on the plate so that after the printed sheet is folded the pages will be in the correct sequence. Books tend to be manufactured nowadays in a few standard sizes. The sizes of books are usually specified as «trim size»: the size of the page after the sheet has been folded and trimmed. The standard sizes result from sheet sizes (therefore machine sizes) which became popular 200 or 300 years ago, and have come to dominate the industry. British conventions in this regard prevail throughout the English-speaking world, except for the US. The European book manufacturing industry works to a completely different set of standards.

Processes

Layout

Modern bound books are organized according to a particular format called the book’s layout. Although there is great variation in layout, modern books tend to adhere to a set of rules with regard to what the parts of the layout are and what their content usually includes. A basic layout will include a front cover, a back cover and the book’s content which is called its body copy or content pages. The front cover often bears the book’s title (and subtitle, if any) and the name of its author or editor(s). The inside front cover page is usually left blank in both hardcover and paperback books. The next section, if present, is the book’s front matter, which includes all textual material after the front cover but not part of the book’s content such as a foreword, a dedication, a table of contents and publisher data such as the book’s edition or printing number and place of publication. Between the body copy and the back cover goes the end matter which would include any indices, sets of tables, diagrams, glossaries or lists of cited works (though an edited book with several authors usually places cited works at the end of each authored chapter). The inside back cover page, like that inside the front cover, is usually blank. The back cover is the usual place for the book’s ISBN and maybe a photograph of the author(s)/ editor(s), perhaps with a short introduction to them. Also here often appear plot summaries, barcodes and excerpted reviews of the book.[36]

The body of the books is usually divided into parts, chapters, sections and sometimes subsections that are composed of at least a paragraph or more.

Printing

Some books, particularly those with shorter runs (i.e. with fewer copies) will be printed on sheet-fed offset presses, but most books are now printed on web presses, which are fed by a continuous roll of paper, and can consequently print more copies in a shorter time. As the production line circulates, a complete «book» is collected together in one stack of pages, and another machine carries out the folding, pleating, and stitching of the pages into bundles of signatures (sections of pages) ready to go into the gathering line. Note that the pages of a book are printed two at a time, not as one complete book. Excess numbers are printed to make up for any spoilage due to make-readies or test pages to assure final print quality.

A make-ready is the preparatory work carried out by the pressmen to get the printing press up to the required quality of impression. Included in make-ready is the time taken to mount the plate onto the machine, clean up any mess from the previous job, and get the press up to speed. As soon as the pressman decides that the printing is correct, all the make-ready sheets will be discarded, and the press will start making books. Similar make readies take place in the folding and binding areas, each involving spoilage of paper.

Binding

After the signatures are folded and gathered, they move into the bindery. In the middle of last century there were still many trade binders—stand-alone binding companies which did no printing, specializing in binding alone. At that time, because of the dominance of letterpress printing, typesetting and printing took place in one location, and binding in a different factory. When type was all metal, a typical book’s worth of type would be bulky, fragile and heavy. The less it was moved in this condition the better: so printing would be carried out in the same location as the typesetting. Printed sheets on the other hand could easily be moved. Now, because of increasing computerization of preparing a book for the printer, the typesetting part of the job has flowed upstream, where it is done either by separately contracting companies working for the publisher, by the publishers themselves, or even by the authors. Mergers in the book manufacturing industry mean that it is now unusual to find a bindery which is not also involved in book printing (and vice versa).

If the book is a hardback its path through the bindery will involve more points of activity than if it is a paperback. Unsewn binding is now increasingly common. The signatures of a book can also be held together by «Smyth sewing» using needles, «McCain sewing», using drilled holes often used in schoolbook binding, or «notch binding», where gashes about an inch long are made at intervals through the fold in the spine of each signature. The rest of the binding process is similar in all instances. Sewn and notch bound books can be bound as either hardbacks or paperbacks.

Finishing

«Making cases» happens off-line and prior to the book’s arrival at the binding line. In the most basic case-making, two pieces of cardboard are placed onto a glued piece of cloth with a space between them into which is glued a thinner board cut to the width of the spine of the book. The overlapping edges of the cloth (about 5/8″ all round) are folded over the boards, and pressed down to adhere. After case-making the stack of cases will go to the foil stamping area for adding decorations and type.

Digital printing

Recent developments in book manufacturing include the development of digital printing. Book pages are printed, in much the same way as an office copier works, using toner rather than ink. Each book is printed in one pass, not as separate signatures. Digital printing has permitted the manufacture of much smaller quantities than offset, in part because of the absence of make readies and of spoilage. One might think of a web press as printing quantities over 2000, quantities from 250 to 2000 being printed on sheet-fed presses, and digital presses doing quantities below 250.[citation needed] These numbers are of course only approximate and will vary from supplier to supplier, and from book to book depending on its characteristics. Digital printing has opened up the possibility of print-on-demand, where no books are printed until after an order is received from a customer.

Ebook

In the 2000s, due to the rise in availability of affordable handheld computing devices, the opportunity to share texts through electronic means became an appealing option for media publishers.[37] Thus, the «ebook» was made. The term ebook is a contraction of «electronic book»; which refers to a book-length publication in digital form.[38] An ebook is usually made available through the internet, but also on CD-ROM and other forms. Ebooks may be read either via a computing device with an LED display such as a traditional computer, a smartphone, or a tablet computer; or by means of a portable e-ink display device known as an ebook reader, such as the Sony Reader, Barnes & Noble Nook, Kobo eReader, or the Amazon Kindle. Ebook readers attempt to mimic the experience of reading a print book by using the e-ink technology, since the displays on ebook readers are much less reflective.

Audiobooks

Audiobooks, or recordings of people reading books aloud, were first created in 1932 in the United States. The first audiobooks were created by the American Foundation for the Blind on vinyl records, where each side could hold 15 minutes of recording. The first recorded pieces were some of William Shakespeare’s plays, the Constitution of the United States, and the novel As the Earth Turns by Gladys Hasty Carroll. Gradually over the course of the 20th century and with the dawn of cassette tapes and compact discs, audiobooks began to be sold by booksellers who often had dedicated sections. Publishers of books additionally created divisions within their companies dedicated to audiobooks. By the turn of the millennium, audiobooks were digitally distributed on devices designed around audiobooks, and audiobooks began to receive different narrators for different parts. Some companies, such as the Amazon subsidiary Audible, are tailored to work exclusively in audiobooks, and while their effectiveness is subject to wide debate, sales of audiobooks continue to skyrocket in the present day.[39][8]

Design

Book design is the art of incorporating the content, style, format, design, and sequence of the various components of a book into a coherent whole. In the words of Jan Tschichold, book design «though largely forgotten today, methods and rules upon which it is impossible to improve have been developed over centuries. To produce perfect books these rules have to be brought back to life and applied.» Richard Hendel describes book design as «an arcane subject» and refers to the need for a context to understand what that means. Many different creators can contribute to book design, including graphic designers, artists and editors.

Sizes

Actual-size facsimile of the Codex Gigas, also known as the ‘Devil’s Bible’ (from the illustration at right)

A page from the world’s largest book. Each page is three and a half feet wide, five feet tall and a little over five inches thick.

The size of a modern book is based on the printing area of a common flatbed press. The pages of type were arranged and clamped in a frame, so that when printed on a sheet of paper the full size of the press, the pages would be right side up and in order when the sheet was folded, and the folded edges trimmed.

The most common book sizes are:

- Quarto (4to): the sheet of paper is folded twice, forming four leaves (eight pages) approximately 11–13 inches (c. 30 cm) tall

- Octavo (8vo): the most common size for current hardcover books. The sheet is folded three times into eight leaves (16 pages) up to 9+3⁄4 inches (c. 23 cm) tall.

- DuoDecimo (12mo): a size between 8vo and 16mo, up to 7+3⁄4 inches (c. 18 cm) tall

- Sextodecimo (16mo): the sheet is folded four times, forming 16 leaves (32 pages) up to 6+3⁄4 inches (c. 15 cm) tall

Sizes smaller than 16mo are:

- 24mo: up to 5+3⁄4 inches (c. 13 cm) tall.

- 32mo: up to 5 inches (c. 12 cm) tall.

- 48mo: up to 4 inches (c. 10 cm) tall.

- 64mo: up to 3 inches (c. 8 cm) tall.

Small books can be called booklets.

Sizes larger than quarto are:

- Folio: up to 15 inches (c. 38 cm) tall.

- Elephant Folio: up to 23 inches (c. 58 cm) tall.

- Atlas Folio: up to 25 inches (c. 63 cm) tall.

- Double Elephant Folio: up to 50 inches (c. 127 cm) tall.

The largest extant medieval manuscript in the world is Codex Gigas 92 × 50 × 22 cm. The world’s largest book is made of stone and is in Kuthodaw Pagoda (Burma).

Types

By content

A common separation by content are fiction and non-fiction books. This simple separation can be found in most collections, libraries, and bookstores. There are other types such as books of sheet music.

Fiction

Many of the books published today are «fiction», meaning that they contain invented material, and are creative literature. Other literary forms such as poetry are included in the broad category. Most fiction is additionally categorized by literary form and genre.

The novel is the most common form of fiction book. Novels are stories that typically feature a plot, setting, themes and characters. Stories and narrative are not restricted to any topic; a novel can be whimsical, serious or controversial. The novel has had a tremendous impact on entertainment and publishing markets.[40] A novella is a term sometimes used for fiction prose typically between 17,500 and 40,000 words, and a novelette between 7,500 and 17,500. A short story may be any length up to 10,000 words, but these word lengths vary.

Comic books or graphic novels are books in which the story is illustrated. The characters and narrators use speech or thought bubbles to express verbal language.

Non-fiction

Non-fiction books are in principle based on fact, on subjects such as history, politics, social and cultural issues, as well as autobiographies and memoirs. Nearly all academic literature is non-fiction. A reference book is a general type of non-fiction book which provides information as opposed to telling a story, essay, commentary, or otherwise supporting a point of view.

An almanac is a very general reference book, usually one-volume, with lists of data and information on many topics. An encyclopedia is a book or set of books designed to have more in-depth articles on many topics. A book listing words, their etymology, meanings, and other information is called a dictionary. A book which is a collection of maps is an atlas. A more specific reference book with tables or lists of data and information about a certain topic, often intended for professional use, is often called a handbook. Books which try to list references and abstracts in a certain broad area may be called an index, such as Engineering Index, or abstracts such as chemical abstracts and biological abstracts.

Books with technical information on how to do something or how to use some equipment are called instruction manuals. Other popular how-to books include cookbooks and home improvement books.

Students typically store and carry textbooks and schoolbooks for study purposes.

Unpublished

Many types of book are private, often filled in by the owner, for a variety of personal records. Elementary school pupils often use workbooks, which are published with spaces or blanks to be filled by them for study or homework. In US higher education, it is common for a student to take an exam using a blue book.

There is a large set of books that are made only to write private ideas, notes, and accounts. These books are rarely published and are typically destroyed or remain private. Notebooks are blank papers to be written in by the user. Students and writers commonly use them for taking notes. Scientists and other researchers use lab notebooks to record their notes. They often feature spiral coil bindings at the edge so that pages may easily be torn out.

Address books, phone books, and calendar/appointment books are commonly used on a daily basis for recording appointments, meetings and personal contact information. Books for recording periodic entries by the user, such as daily information about a journey, are called logbooks or logs. A similar book for writing the owner’s daily private personal events, information, and ideas is called a diary or personal journal. Businesses use accounting books such as journals and ledgers to record financial data in a practice called bookkeeping (now usually held on computers rather than in hand-written form).

Other

There are several other types of books which are not commonly found under this system. Albums are books for holding a group of items belonging to a particular theme, such as a set of photographs, card collections, and memorabilia. One common example is stamp albums, which are used by many hobbyists to protect and organize their collections of postage stamps. Such albums are often made using removable plastic pages held inside in a ringed binder or other similar holder. Picture books are books for children with pictures on every page and less text (or even no text).

Hymnals are books with collections of musical hymns that can typically be found in churches. Prayerbooks or missals are books that contain written prayers and are commonly carried by monks, nuns, and other devoted followers or clergy. Lap books are a learning tool created by students.

Decodable readers and leveling

A leveled book collection is a set of books organized in levels of difficulty from the easy books appropriate for an emergent reader to longer more complex books adequate for advanced readers. Decodable readers or books are a specialized type of leveled books that use decodable text only including controlled lists of words, sentences and stories consistent with the letters and phonics that have been taught to the emergent reader. New sounds and letters are added to higher level decodable books, as the level of instruction progresses, allowing for higher levels of accuracy, comprehension and fluency.

By physical format

Hardcover books have a stiff binding. Paperback books have cheaper, flexible covers which tend to be less durable. An alternative to paperback is the glossy cover, otherwise known as a dust cover, found on magazines, and comic books. Spiral-bound books are bound by spirals made of metal or plastic. Examples of spiral-bound books include teachers’ manuals and puzzle books (crosswords, sudoku).

Publishing is a process for producing pre-printed books, magazines, and newspapers for the reader/user to buy.

Publishers may produce low-cost, pre-publication copies known as galleys or ‘bound proofs’ for promotional purposes, such as generating reviews in advance of publication. Galleys are usually made as cheaply as possible, since they are not intended for sale.

Dummy books

Cigarette smuggling with a book

Dummy books (or faux books) are books that are designed to imitate a real book by appearance to deceive people, some books may be whole with empty pages, others may be hollow or in other cases, there may be a whole panel carved with spines which are then painted to look like books, titles of some books may also be fictitious.

There are many reasons to have dummy books on display such as; to allude visitors of the vast wealth of information in their possession and to inflate the owner’s appearance of wealth, to conceal something,[41] for shop displays or for decorative purposes.

In early 19th century at Gwrych Castle, North Wales, Lloyd Hesketh Bamford-Hesketh was known for his vast collection of books at his library, however, at the later part of that same century, the public became aware that parts of his library was a fabrication, dummy books were built and then locked behind glass doors to stop people from trying to access them, from this a proverb was born, «Like Hesky’s library, all outside».[42][43]

Libraries

Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books, (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) first appeared in classical Greece. In the ancient world, the maintaining of a library was usually (but not exclusively) the privilege of a wealthy individual. These libraries could have been either private or public, i.e. for people who were interested in using them. The difference from a modern public library lies in that they were usually not funded from public sources. It is estimated that in the city of Rome at the end of the 3rd century there were around 30 public libraries. Public libraries also existed in other cities of the ancient Mediterranean region (for example, Library of Alexandria).[44] Later, in the Middle Ages, monasteries and universities also had libraries that could be accessible to the general public. Typically not the whole collection was available to the public; the books could not be borrowed and often were chained to reading stands to prevent theft.

The beginning of the modern public library begins around 15th century when individuals started to donate books to towns.[45] The growth of a public library system in the United States started in the late 19th century and was much helped by donations from Andrew Carnegie. This reflected classes in a society: the poor or the middle class had to access most books through a public library or by other means, while the rich could afford to have a private library built in their homes. In the United States the Boston Public Library 1852 Report of the Trustees established the justification for the public library as a tax-supported institution intended to extend educational opportunity and provide for general culture.[46]

The advent of paperback books in the 20th century led to an explosion of popular publishing. Paperback books made owning books affordable for many people. Paperback books often included works from genres that had previously been published mostly in pulp magazines. As a result of the low cost of such books and the spread of bookstores filled with them (in addition to the creation of a smaller market of extremely cheap used paperbacks), owning a private library ceased to be a status symbol for the rich.

The development of libraries has prompted innovations to help store and organize books on shelves. In library and booksellers’ catalogues, it is common to include an abbreviation such as «Crown 8vo» to indicate the paper size from which the book is made. When rows of books are lined on a book holder, bookends are sometimes needed to keep them from slanting.

Identification and classification

During the 20th century, librarians were concerned about keeping track of the many books being added yearly to the Gutenberg Galaxy. Through a global society called the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), they devised a series of tools including the International Standard Bibliographic Description (ISBD). Each book is specified by an International Standard Book Number, or ISBN, which is unique to every edition of every book produced by participating publishers, worldwide. It is managed by the ISBN Society. An ISBN has four parts: the first part is the country code, the second the publisher code, and the third the title code. The last part is a check digit, and can take values from 0–9 and X (10). The EAN Barcodes numbers for books are derived from the ISBN by prefixing 978, for Bookland, and calculating a new check digit.

Commercial publishers in industrialized countries generally assign ISBNs to their books, so buyers may presume that the ISBN is part of a total international system, with no exceptions. However, many government publishers, in industrial as well as developing countries, do not participate fully in the ISBN system, and publish books which do not have ISBNs. A large or public collection requires a catalogue. Codes called «call numbers» relate the books to the catalogue, and determine their locations on the shelves. Call numbers are based on a Library classification system. The call number is placed on the spine of the book, normally a short distance before the bottom, and inside. Institutional or national standards, such as ANSI/NISO Z39.41 – 1997, establish the correct way to place information (such as the title, or the name of the author) on book spines, and on «shelvable» book-like objects, such as containers for DVDs, video tapes and software.

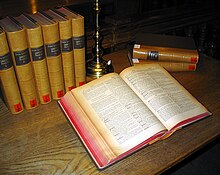

Books on library shelves and call numbers visible on the spines

One of the earliest and most widely known systems of cataloguing books is the Dewey Decimal System. Another widely known system is the Library of Congress Classification system. Both systems are biased towards subjects which were well represented in US libraries when they were developed, and hence have problems handling new subjects, such as computing, or subjects relating to other cultures.[47] Information about books and authors can be stored in databases like online general-interest book databases. Metadata, which means «data about data» is information about a book. Metadata about a book may include its title, ISBN or other classification number (see above), the names of contributors (author, editor, illustrator) and publisher, its date and size, the language of the text, its subject matter, etc.

Classification systems

- Bliss bibliographic classification (BC)

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Colon Classification

- Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)

- Harvard-Yenching Classification

- Library of Congress Classification (LCC)

- New Classification Scheme for Chinese Libraries

- Universal Decimal Classification (UDC)

Uses

Aside from the primary purpose of reading them, books are also used for other ends:

- A book can be an artistic artifact, a piece of art; this is sometimes known as an artists’ book.

- A book may be evaluated by a reader or professional writer to create a book review.

- A book may be read by a group of people to use as a spark for social or academic discussion, as in a book club.

- A book may be studied by students as the subject of a writing and analysis exercise in the form of a book report.

- Books are sometimes used for their exterior appearance to decorate a room, such as a study.

Marketing

Once the book is published, it is put on the market by distributors and bookstores. Meanwhile, its promotion comes from various media reports. Book marketing is governed by the law in many states.

Secondary spread

In recent years, the book had a second life in the form of reading aloud. This is called public readings of published works, with the assistance of professional readers (often known actors) and in close collaboration with writers, publishers, booksellers, librarians, leaders of the literary world and artists.

Many individual or collective practices exist to increase the number of readers of a book. Among them:

- abandonment of books in public places, coupled or not with the use of the Internet, known as the bookcrossing;

- provision of free books in third places, like bars or cafes;

- itinerant or temporary libraries;

- free public libraries in the area.

Industry evolution

This form of the book chain has hardly changed since the eighteenth century, and has not always been this way. Thus, the author has asserted gradually with time, and the copyright dates only from the nineteenth century. For many centuries, especially before the invention of printing, each freely copied out books that passed through his hands, adding if desired his own comments. Similarly, bookseller and publisher jobs have emerged with the invention of printing, which made the book an industrial product, requiring structures of production and marketing.

The invention of the Internet, e-readers, tablets, and projects like Wikipedia and Gutenberg, are likely to change the book industry for years to come.

Paper and conservation

Paper was first made in China as early as 200 BC, and reached Europe through Muslim territories. At first made of rags, the Industrial Revolution changed paper-making practices, allowing for paper to be made out of wood pulp. Papermaking in Europe began in the 11th century, although vellum was also common there as page material up until the beginning of the 16th century, vellum being the more expensive and durable option. Printers or publishers would often issue the same publication on both materials, to cater to more than one market.

Paper made from wood pulp became popular in the early 20th century, because it was cheaper than linen or abaca cloth-based papers. Pulp-based paper made books less expensive to the general public. This paved the way for huge leaps in the rate of literacy in industrialised nations, and enabled the spread of information during the Second Industrial Revolution.

Pulp paper, however, contains acid which eventually destroys the paper from within. Earlier techniques for making paper used limestone rollers, which neutralized the acid in the pulp. Books printed between 1850 and 1950 are primarily at risk; more recent books are often printed on acid-free or alkaline paper. Libraries today have to consider mass deacidification of their older collections in order to prevent decay.

Stability of the climate is critical to the long-term preservation of paper and book material.[48] Good air circulation is important to keep fluctuation in climate stable. The HVAC system should be up to date and functioning efficiently. Light is detrimental to collections. Therefore, care should be given to the collections by implementing light control. General housekeeping issues can be addressed, including pest control. In addition to these helpful solutions, a library must also make an effort to be prepared if a disaster occurs, one that they cannot control. Time and effort should be given to create a concise and effective disaster plan to counteract any damage incurred through «acts of God», therefore an emergency management plan should be in place.

See also

- Outline of books

- Alphabet book

- Artist’s book

- Audiobook

- Bibliodiversity

- Book burning

- Booksellers

- Lists of books

- Miniature book

- Open access book

- Society for the History of Authorship, Reading and Publishing (SHARP)

Citations

- ^ Feather, John; Sturges, Paul (2003). International Encyclopedia of Information and Library Science (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 0-415-25901-0. OCLC 50480180. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (August 5, 2010). «Google: There Are Exactly 129,864,880 Books in the World». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ Curtis, George (2011). The Law of Cybercrimes and Their Investigations. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-4398-5832-5. OCLC 908077615.

- ^ Ang, Carmen (October 15, 2021). «Print Has Prevailed: The Staying Power of Physical Books». Visual Capitalist. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ Richter, Felix (April 21, 2022). «E-Books Still No Match for Printed Books». Statista. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ Handley, Lucy (September 19, 2019). «Physical books still outsell e-books – and here’s why». CNBC. Archived from the original on January 2, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Kate (March 10, 2023). «Gen Zers are bookworms but say they’re shunning e-books because of eye strain, digital detoxing, and their love for libraries». Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Bussel, Rachel Kramer (December 31, 2021). «2021 Book Trends Show The Power Of BookTok And Rise Of Audiobooks». Forbes. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ «book | Etymology, origin and meaning of book». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ «Northvegr – Holy Language Lexicon». November 3, 2008. Archived from the original on November 3, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ «codex». Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Biggs, Robert D. (1974). Inscriptions from Tell Abū Ṣalābīkh (PDF). Oriental Institute Publications. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-62202-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Avrin 2010, pp. 173.

- ^ Bischoff, Bernhard (1990). Latin palaeography antiquity and the Middle Ages. Dáibhí ó Cróinin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-36473-7. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ Avrin 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Dard Hunter. Papermaking: History and Technique of an Ancient Craft New ed. Dover Publications 1978, p. 12.

- ^ Avrin 2010, pp. 144–145.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Edd. Frances Young, Lewis Ayres, Andrew Louth, Ron White. Cambridge University Press 2004, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Avrin 2010, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Theodore Maynard. Saint Benedict and His Monks. Staples Press Ltd 1956, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Joachim, Martin D. (2003). Historical Aspects of Cataloging and Classification. New York: Haworth Information Press. p. 452. ISBN 9780789019813. OCLC 683191430. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ Diehl, Edith (1980). Bookbinding : its background and technique. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 14–16. ISBN 0-486-24020-7. OCLC 7027090.

- ^ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin Palaeography, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Paul Saenger. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press 1997.

- ^ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin Palaeography, pp. 42–43.

- ^ W. Durant, «The Age of Faith», New York 1950, p. 236

- ^ S.E. Al-Djazairi «The Golden Age of Islamic Civilization», Manchester 1996, p. 200

- ^ Edmund Burke (June 2009). «Islam at the Center: Technological Complexes and the Roots of Modernity». Journal of World History. 20 (2): 165–86 [43]. doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0045. S2CID 143484233.

- ^ Edmund Burke (June 2009). «Islam at the Center: Technological Complexes and the Roots of Modernity». Journal of World History. 20 (2): 165–186 [44]. doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0045. S2CID 143484233.

- ^ Johs. Pedersen, «The Arabic Book», Princeton University Press, 1984, p. 59

- ^ Clapham, Michael, «Printing» in A History of Technology, Vol 2. From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, edd. Charles Singer et al. (Oxford 1957), p. 377. Cited from Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge University, 1980).

- ^ Bruckner, D. J. R. (November 20, 1995). «How the Earlier Media Achieved Critical Mass: Printing Press;Yelling ‘Stop the Presses!’ Didn’t Happen Overnight». The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ^ «Bowker Reports Traditional U.S. Book Production Flat in 2009». Archived from the original on January 28, 2012.

- ^ Kelting, M. Whitney (2001). Singing to the Jinas: Jain Laywomen, Mandal Singing, and the Negotiations of Jain Devotion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803211-3. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Vermeer, Leslie (2016). The Complete Canadian Book Editor. Brush Education. ISBN 978-1-55059-677-9. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Gary B. Shelly; Joy L. Starks (2011). Microsoft Publisher 2010: Comprehensive. Cengage Learning. p. 559. ISBN 978-1-133-17147-8. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Rainie, Lee; Zickuhr, Kathryn; Purcell, Kristen; Madden, Mary; Brenner, Joanna (April 4, 2012). «The rise of e-reading». Pew Internet Libraries. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ «What is an e-book». Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ «A short history of the audiobook, 20 years after the first portable digital audio device». PBS NewsHour. November 22, 2017. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Edwin Mcdowell (October 30, 1989). «The Media Business; Publishers Worry After Fiction Sales Weaken». The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ Golder, Joseph (October 28, 2021). «Man Finds Secret Passage Hidden Behind Bookshelf in His 500-Year-Old Home’s Library». Newsweek.com. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Apperson, George Latimer (May 10, 2006). Dictionary of Proverbs. Wordsworth Editions. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-84022-311-8. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Sparke, Archibald (March 4, 1922). «Pseudo-titles for «Dummy» books». Notes and Queries. s12-X (203): 174. doi:10.1093/nq/s12-x.203.174a. ISSN 1471-6941. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ Miriam A. Drake, Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science (Marcel Dekker, 2003), «Public Libraries, History».

- ^ Miriam A. Drake, Encyclopedia of Library, «Public Libraries, History».

- ^ McCook, Kathleen de la Peña (2011), Introduction to Public Librarianship, 2nd ed., p. 23 New York, Neal-Schuman.

- ^ Hoffman, Gretchen L. (August 5, 2019). Organizing Library Collections: Theory and Practice. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-5381-0852-9. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ Patkus, Beth (2003). «Assessing Preservation Needs, A Self-Survey Guide». Andover: Northeast Document Conservation Center.

Bibliography

- «Book», in International Encyclopedia of Information and Library Science («IEILS»), Editors: John Feather, Paul Sturges, 2003, Routledge, ISBN 978-1134513215

- Avrin, Leila (2010). Scribes, Script, and Books : The Book Arts from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Chicago: American Library Association. ISBN 978-0-8389-1038-2. OCLC 489670041.

Further reading

- Tim Parks (August 2017), «The Books We Don’t Understand», The New York Review of Books

External links

- Information on Old Books, Smithsonian Libraries

- «Manuscripts, Books, and Maps: The Printing Press and a Changing World»

Recent Examples on the Web

The yogi was an effortlessly beautiful fortysomething woman who appeared on the covers of books and magazines and headlined her own yoga retreats.

—

No longer a niche game, it’s been played by more than 50 million people to date, according to Wizards of the Coast, the Hasbro division that owns D&D. The game has also moved beyond the tabletop to other mediums, including television, books and movies.

—

Aside from handing out 15 awards to TV shows, movies, musicians, books and journalists who reflected fair, accurate and inclusive representations of LGBTQ people and issues, the event also handed out three special honors to Bad Bunny, Christina Aguilera and Jeremy Pope.

—

Its 745 glossy pages of text are adorned with scores of images—portraits, photographs, maps and frontispieces, each illustrating the myriad books, authors, artists, architects and historical events discussed in its 32 chapters.

—

The Guardian | March 25, 2023 | 5,574 words In this excerpt from her book, Wavewalker: Breaking Free, Suzanne Heywood recounts the misery of her unconventional childhood.

—

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

—

Next up, books and fashion.

—

Appraisers will be available to appraise cast iron toys, coins, pottery, china, collectables, furniture, guns, military items, antique weapons, dolls, teddy bears, engravings, art, jewelry, string instruments, books and more.

—

In addition to paying for the cruise itself, travelers can add things like a cabin upgrade or pre-book onboard amenities and shore excursions through the system.

—

Here’s the good: Officials said decades of relationship-building have allowed them to re-book critical revenue-driving conventions as early as 2022.

—

Beamed directly to the book, and beamed (via an intra-book search) to the piece of information.

—

Entertainment Tonight shared the details of a multi-book deal worth at least $35 million.

—

Of course, there will be perks for Mercedes owners—they’ll be able to pre-book charging appointments and be prioritized by the network.

—

Multi-book reviews warrant much more space for overview and discussion.

—

Global users can now pre-book rides for every leg of their journey, each of which earns 10% back in Uber Cash to spend on future travels or food delivery orders.

—

Hoping to replicate the success of Halo and its accompanying novels, Microsoft signed a multi-book deal with Tor, one of the most prominent science fiction and fantasy imprints, and brought on award-winning author Greg Rucka to helm the project.

—

Go book yourself a massage—your back will need it.

—

Shortly after the producers booked the show for a late 2020 run at the National Theater in Washington, D.C., the pandemic hit and the run was canceled.

—

My husband booked it during the pandemic, in April 2021.

—

Don your favorite traction devices atop the canyon to crunch through seasonal ice and book a backcountry permit for late fall, winter, or early spring.

—

She was taken to a hospital and then booked in the Fairfax County jail on Thursday.

—

Opt to stay at one of the many beachfront resorts, like the Marriott Hilton Head Resort & Spa or the Omni Hilton Head Oceanfront Resort, or book a stay at a beloved boutique hotel, like The Inn & Club at Harbour Town. 2.

—

To set up your registry, simply sign up through Bloomingdale’s website or book an appointment with a registry consultant.

—

Find the perfect place, book a hotel and come up with an itinerary with your teen’s interests in mind.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘book.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

454

Previews

8

Favorites

Purchase options

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

14 day loan required to access EPUB and PDF files.

IN COLLECTIONS

Books to Borrow

Books for People with Print Disabilities

Internet Archive Books

American Libraries

Uploaded by

KellyCritch

on November 11, 2009

The history of the book is the story of a suite of technological innovations that improved the quality of text conservation, the access to information, portability, and the cost of production. This history is strongly linked to political and economical contingencies and the history of ideas and religions.

Origins and antiquity

Writing is a system of linguistic symbols which permit one to transmit and conserve information. Writing appears to have developed between the 7th millennium BC and the 4th millennium BC, first in the form of early mnemonic symbols which became a system of ideograms or pictographs through simplification. The oldest known forms of writing were thus primarily logographic in nature. Later syllabic and alphabetic (or segmental) writing emerged.

Silk, in China, was also a base for writing. Writing was done with brushes. Many other materials were used as bases: bone, bronze, pottery, shell, etc. In India, for example, dried palm tree leaves were used; in Mesoamerica another type of plant,Amate . Any material which will hold and transmit text is a candidate for books. Given this, the human body could be seen as a book, with tattooing, and if we consider that human memory develops and transforms with the appearance of writing, it is perhaps not absurd to consider that this ability makes humans into living books (this idea is illustrated by Ray Bradbury in «The Illustrated Man», Peter Greenaway in «The Pillow Book»).

The book is also linked to the desire of humans to create lasting records. Stones could be the most ancient form of writing, but wood would be the first medium to take the guise of a book. The words «biblos» and «liber» first meant «fibre inside of a tree». In Chinese, the character that means book is an image of a tablet of bamboo. Wooden tablets (Rongorongo) were also made on Easter Island.

Clay tablets

Clay tablets were used in Mesopotamia in the third millennium BC. The calamus, an instrument in the form of a triangle, was used to make characters in moist clay. The tablets were fired to dry them out. At Nineveh, 22,000 tablets were found, dating from the seventh century BC; this was the archive and library of the kings of Assyria, who had workshops of copyists and conservationists at their disposal. This presupposes a degree of organization with respect to books, consideration given to conservation, classification, etc.

Wax tablets

Romans used wax-coated wooden tablets («pugillares») upon which they could write and erase by using a stylus. One end of the stylus was pointed, and the other was spherical. Usually these tablets were used for everyday purposes (accounting, notes) and for teaching writing to children, according to the methods discussed by Quintilian in his «Institutio Oratoria» X Chapter 3. Several of these tablets could be assembled in a form similar to a codex. Also the etymology of the word codex (block of wood) suggest that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets. [Bernhard Bischoff. «Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages», Cambridge University Press 2003 [reprint] , p. 11.]

Papyrus

After extracting the marrow from the stems, a series of steps (humidification, pressing, drying, gluing, and cutting), produced media of variable quality, the best being used for sacred writing. In Ancient Egypt, papyrus was used for writing maybe as early as from First Dynasty, but first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC). [Leila Avrin. «Scribes, Script and Books. The Book Arts from Antiquity to the Renaissance». American Library Association / The British Library 1991, p. 83.] A calamus, the stem of a reed sharpened to a point, or bird feathers were used for writing. The script of Egyptian scribes was called hieratic, or sacredotal writing; it is not hieroglyphic, but a simplified form more adapted to manuscript writing (hieroglyphs usually being engraved or painted).

Papyrus books were in the form of a scroll of several sheets pasted together, for a total length of up to 10 meters or even more. Some books, such as the history of the reign of Ramses III, were over 40 meters long. Books rolled out horizontally; the text occupied one side, and was divided into columns. The title was indicated by a label attached to the cylinder containing the book. Many papyrus texts come from tombs, where prayers and sacred texts were deposited (such as the Book of the Dead, from the early 2nd millennium BC).

These examples demonstrate that the development of the book, in its material makeup and external appearance, depended on a content dictated by political (the histories of pharaohs) and religious (belief in an afterlife) values. The particular influence afforded to writing and word perhaps motivated research into ways of conserving texts.

Parchment

Parchment progressively replaced papyrus. Legend attributes its invention to Eumenes II, the king of Pergamon, from which comes the name «pergamineum,» which became «parchment.» Its production began around the third century BC. Made using the skins of animals (sheep, cattle, donkey, antelope, etc.), parchment proved easier to conserve over time; it was more solid, and allowed one to erase text. It was a very expensive medium because of the rarity of material and the time required to produce a document. Vellum is the finest quality of parchment.

Greece and Rome

The scroll of papyrus is called «volumen» in Latin, a word which signifies «circular movement,» «roll,» «spiral,» «whirlpool,» «revolution» and finally «a roll of writing paper, a rolled manuscript, or a book.»

In the 7th century Isidore of Seville explains the relation between codex, book and scroll in his «Etymologiae» (VI.13) as this:

Description

The scroll is rolled around two vertical wooden axes. This design allows only sequential usage; one is obliged to read the text in the order in which it is written, and it is impossible to place a marker in order to directly access a precise point in the text. It is comparable to modern video cassettes. Moreover, the reader must use both hands to hold on to the vertical wooden rolls and therefore cannot read and write at the same time. The only volumen in common usage today is the Jewish Torah.

Book Culture

The authors of Antiquity had no rights concerning their published works; there were neither authors’ nor publishing rights. Anyone could have a text recopied, and even alter its contents. Scribes earned money and authors earned mostly glory, unless a patron provided cash; a book made its author immortal. This followed the traditional conception of the culture: an author stuck to several models, which he imitated and attempted to improve. The status of the author was not regarded as absolutely personal.

From a political and religious point of view, books were censored very early: the works of Protagoras were burned because he was a proponent of agnosticism and argued that one could know whether or not the gods existed. Generally, cultural conflicts led to important periods of book destruction: in 303, the emperor Diocletian ordered the burning of Christian texts. Christians later burned libraries, and especially heretical or non-canonical Christian texts. These practices are found throughout human history. One sees what is at stake in these battles over the book: the effort to remove all traces of adversarial ideas and thereby to deprive posterity these works. One violently strikes out at an author when one attacks his or her works; it is a form of violence perhaps more effective than physical attack.

But there also exists a less visible but nonetheless effective form of censorship when books are reserved for the elite; the book was not originally a media for expressive liberty. It may serve to confirm the values of a political system, as during the reign of the emperor Augustus, who skillfully surrounded himself with great authors. This is a good ancient example of the control of the media by a political power.

Proliferation and conservation of books in Greece

Little information concerning books in Ancient Greece survives. Several vases (Sixth century BC and fifth century BC) bear images of volumina. There was undoubtedly no extensive trade in books, but there existed several sites devoted to the sale of books.

The spread of books, and attention to their cataloging and conservation, as well as literary criticism developed during the Hellenistic period with the creation of large libraries in response to the desire for knowledge exemplified by Aristotle. These libraries were undoubtedly also built as demonstrations of political prestige:

*The Library of Alexandria, a library created by Ptolemy Soter and set up by Demetrios of Phaleron. It contained 500,900 volumes (in the «Museion» section) and 40,000 at the Serapis temple («Serapeion»). All books in the luggage of visitors to Egypt were inspected, and could be held for copying. The Museion was partially destroyed in 47 BC.

*The Library at Pergamon, founded by Attalus I; it contained 200,000 volumes which were moved to the Serapeion by Mark Antony and Cleopatra, after the destruction of the Museion. The Serapeion was partially destroyed in 391, and the last books disappeared in 641 CE following the Arab conquest.

*The Library at Athens, the «Ptolemaion», which gained importance following the destruction of the Library at Alexandria ; the library of Pantainos, around 100 CE; the library of Hadrian, in 132 CE.

*The Library at Rhodes, a library that rivaled the Library of Alexandria.

*The Library at Antioch, a public library of which Euphorion of Chalcis was the director near the end of the third century.

The libraries had copyist workshops, and the general organisation of books allowed for the following:

*Conservation of an example of each text

*Translation (the Septuagint Bible, for example)

*Literary criticisms in order to establish reference texts for the copy (example : «The Iliad» and «The Odyssey»)

*A catalog of books

*The copy itself, which allowed books to be disseminated

Book production in Rome

Book production developed in Rome in the first century BC with Latin literature that had been influenced by the Greek.

This diffusion primarily concerned circles of literary individuals. Atticus was the editor of his friend Cicero. However, the book business progressively extended itself through the Roman Empire; for example, there were bookstores in Lyon. The spread of the book was aided by the extension of the Empire, which implied the imposition of the Latin tongue on a great number of people (in Spain, Africa, etc.).

Libraries were private or created at the behest of an individual. Julius Caesar, for example, wanted to establish one in Rome, proving that libraries were signs of political prestige.

In the year 377, there were 28 libraries in Rome, and it is known that there were many smaller libraries in other cities. Despite the great distribution of books, scientists do not have a complete picture as to the literary scene in antiquity as thousands of books have been lost through time.

Middle Ages

By the end of antiquity, between the second century and fourth century, the codex had replaced the scroll. The book was no longer a continuous roll, but a collection of sheets attached at the back. It became possible to access a precise point in the text directly. The codex is equally easy to rest on a table, which permits the reader to take notes while he or she is reading. The codex form improved with the separation of words, capital letters, and punctuation, which permitted silent reading. Tables of contents and indices facilitated direct access to information. This form was so effective that it is still the standard book form, over 1500 years after its appearance.

Paper would progressively replace parchment. Cheaper to produce, it allowed a greater diffusion of books.

Books in monasteries

A number of Christian books were destroyed at the order of Diocletian in 304 CE. During the turbulent periods of the invasions, it was the monasteries that conserved religious texts and certain works of Antiquity for the West. But there would also be important copying centers in Byzantium.

The role of monasteries in the conservation of books is not without some ambiguity:

*Reading was an important activity in the lives of monks, which can be divided into prayer, intellectual work, and manual labor (in the Benedictine order, for example). It was therefore necessary to make copies of certain works. There therefore existed «scriptoria» (the plural of «scriptorium») in many monasteries, where manuscripts where monks copied and decorated manuscripts that had been preserved.

*However, the conservation of books was not exclusively in order to preserve ancient culture; it was especially relevant to understanding religious texts with the aid of ancient knowledge. Some works were never recopied, having been judged too dangerous for the monks. Morever, in need of blank media, the monks scraped off manuscripts, thereby destroying ancient works. The transmission of knowledge was centered primarily on sacred texts. prum nerj.

Copying and conserving books

Despite this ambiguity, monasteries in the West and the Eastern Empire permitted the conservation of a certain number of secular texts, and several libraries were created: for example, Cassiodorus (‘Vivarum’ in Calabro, around 550), or Constantine I in Constantinople. There were several libraries, but the survival of books often depended on political battles and ideologies, which sometimes entailed massive destruction of books or difficulties in production (for example, the distribution of books during the Iconoclasm between 730 and 842).

The «scriptorium»

The scriptorium was the workroom of monk copyists; here, books were copied, decorated, rebound, and conserved. The armarius directed the work and played the role of librarian.

The role of the copyist was multifaceted: for example, thanks to their work, texts circulated from one monastery to another. Copies also allowed monks to learn texts and to perfect their religious education. The relationship with the book thus defined itself according to an intellectual relationship with God. But if these copies were sometimes made for the monks themselves, there were also copies made on demand.

The task of copying itself had several phases: the preparation of the manuscript in the form of notebooks once the work was complete, the presentation of pages, the copying itself, revision, correction of errors, decoration, and binding. The book therefore required a variety of competencies, which often made a manuscript a collective effort.

Transformation from the literary edition in the twelfth century