What is the history and origin of a word?

The study of the history and origin of words is called ”etymology.

What is origin of words called?

Etymology is the study of the origins of words. …

What is the oldest word?

According to a 2009 study by researchers at Reading University, the oldest words in the English language include “I“, “we“, “who“, “two” and “three“, all of which date back tens of thousands of years.

What is the most used word in the world?

‘The’ is the most used word in the English-speaking world because it’s an essential part of grammar and communication.

What is the world’s worst word?

‘Moist’ – a word apparently despised the world over – is about to be named the worst word in the English language. The word has emerged as a clear frontrunner in a global survey conducted by Oxford Dictionaries.

What is the least popular word?

Fewer than 3% of participants marked they knew the 20 English words below.

- genipap.

- futhorc.

- witenagemot.

- gossypol.

- chaulmoogra.

- brummagem.

- alsike.

- chersonese.

What word is used most in English?

‘The’ tops the league tables of most frequently used words in English, accounting for 5% of every 100 words used.

What are the three most powerful words?

Do you know the three most power words? According to Derek Prince, they are, ‘I forgive you. ‘ Read this book and discover how to apply them to your life! The Bible clearly points out, that as long as you resist forgiving others, you allow the enemy legal access into your life.

What was the most used word in 2020?

Covid

What are the most beautiful words in the world?

The Top 10 Most Beautiful English Words

- 3 Pluviophile (n.)

- 4 Clinomania (n.)

- 5 Idyllic (adj.)

- 6 Aurora (n.)

- 7 Solitude (n.)

- 8 Supine (adj.)

- 9 Petrichor (n.) The pleasant, earthy smell after rain.

- 10 Serendipity (n.) The chance occurrence of events in a beneficial way.

What is a unique word?

To explain this very simply, a unique word is one that’s unusual or different in some way. It might have a complicated history or interesting connections to another language. But, primarily what makes an English word interesting is its unusual spelling, pronunciation or meaning.

What is the happiest word?

The happiest word: Laughter.

What is the most beautiful French word?

Here are the most beautiful French words

- Argent – silver. Argent is used in English too to refer to something silver and shiny.

- Atout – asset. Masculine, noun.

- Arabesque – in Arabic fashion or style. Feminine, noun.

- Bijoux – jewelry. Masculine, noun.

- Bisous – kisses. Masculine, noun.

- Bonbon – candy.

- Brindille – twig.

- Câlin – hug.

What is the most French word?

The longest French word has 27 letters and is “intergouvernementalisations”. However, the word isn’t really popular so most French people consider “anticonstitutionnellement” as being the longest known word.

What is a pretty French word?

Gorgeous French Words That Mean Beautiful Just like in the English language, there are many ways to say “beautiful” in French. attrayant (masculine adjective) – attractive. belle (feminine adjective) – beautiful. charmante (feminine adjective) – charming or lovely. éblouissante (feminine adjective) – dazzling.

What are the 1000 most common words in French?

This is a list of the 1,000 most commonly spoken French words….1000 Most Common French Words.

| Number | French | in English |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | comme | as |

| 2 | je | I |

| 3 | son | his |

| 4 | que | that |

How do you say 1000 in French?

When talking about “one hundred” or “one thousand” in French, we don’t say the “one”, we only say “cent” and “mille”. However when talking about “one million”, “one billion” we do say the one: “un million, un milliard”.

What are the 1000 most common words in Spanish?

This is a list of the 1,000 most commonly spoken Spanish words….1000 Most Common Spanish Words.

| Number | Spanish | in English |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | como | as |

| 2 | I | I |

| 3 | su | his |

| 4 | que | that |

What are the 100 most used Spanish words?

The 100 Most Common Words in Spoken Spanish

| Rank | Word in Spanish | Meaning in English |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | que | that |

| 2 | de | of, from |

| 3 | no | no |

| 4 | a | to |

Does Como mean what?

Cómo means how. “

What are common words in Spanish?

Basic Spanish Words

- Hola = Hello.

- Adiós = Goodbye.

- Por favor = Please.

- Gracias = Thank you.

- Lo siento = Sorry.

- Salud = Bless you (after someone sneezes)

- Sí = Yes.

- No = No.

Is callate a bad word?

Cállate may not be very polite, but it’s not rude. An equivalent to “shut up” could be the expression Cállate la boca.

What are the most popular slang words?

Below are some common teen slang words you might hear:

- Dope – Cool or awesome.

- GOAT – “Greatest of All Time”

- Gucci – Good, cool, or going well.

- Lit – Amazing, cool, or exciting.

- OMG – An abbreviation for “Oh my gosh” or “Oh my God”

- Salty – Bitter, angry, agitated.

- Sic/Sick – Cool or sweet.

Can I learn Spanish in 3 months?

If you have just started learning Spanish, it is understandable that you would want to become fluent in Spanish quickly. It is possible to achieve this goal in three months, provided you do the work and stay consistent throughout the process of learning Spanish.

What’s the best country to learn Spanish?

8 Best Places for Spanish Study Abroad Programs

- Barcelona, Spain. Immerse yourself in Catalonian culture when you study Spanish in Barcelona.

- Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Galápagos Islands, Ecuador.

- Granada, Spain.

- Madrid, Spain.

- Quito, Ecuador.

- Salamanca, Spain.

- Santiago, Chile.

What is the trick to learning Spanish?

Five Simple Tricks to Learn Spanish Quickly

- Never pay for a group lesson in your life ever again.

- Repetitively test yourself on commonly used words until they come to you naturally.

- Have a good old chinwag in Spanish with native speakers.

- Train your ear by listening to videos and films in Spanish.

Where do new words come from? How do you figure out their histories?

An etymology is the history of a linguistic form, such as a word; the same term is also used for the study

of word histories. A dictionary etymology tells us what is known of an English word before it became the word entered

in that dictionary. If the word was created in English, the etymology shows, to whatever extent is not already

obvious from the shape of the word, what materials were used to form it. If the word was borrowed into English,

the etymology traces the borrowing process backward from the point at which the word entered English to the

earliest records of the ancestral language. Where it is relevant, an etymology notes words from other languages that

are related («akin») to the word in the dictionary entry, but that are not in the direct line of borrowing.

How New Words are Formed

An etymologist, a specialist in the study of etymology, must know a good deal about the history of English

and also about the relationships of sound and meaning and their changes over time that underline the reconstruction

of the Indo-European language family. Knowledge is also needed of the various processes by which words are created

within Modern English; the most important processes are listed below.

Borrowing

A majority of the words used in English today are of foreign origin. English still derives much of its vocabulary

from Latin and Greek, but we have also borrowed words from nearly all of the languages in Europe. In the modern

period of linguistic acquisitiveness, English has found vocabulary opportunities even farther afield. From the

period of the Renaissance voyages through the days when the sun never set upon the British Empire and up to

the present, a steady stream of new words has flowed into the language to match the new objects and

experiences English speakers have encountered all over the globe. Over 120 languages are on record as sources

of present-day English vocabulary.

Shortening or Clipping

Clipping (or truncation) is a process whereby an appreciable chunk of an existing word is omitted,

leaving what is sometimes called a stump word. When it is the end of a word that is lopped off, the process

is called back-clipping: thus examination was docked to create exam and gymnasium

was shortened to form gym. Less common in English are fore-clippings, in which the beginning of a

word is dropped: thus phone from telephone. Very occasionally, we see a sort of fore-and-aft

clipping, such as flu, from influenza.

Functional Shift

A functional shift is the process by which an existing word or form comes to be used with another

grammatical function (often a different part of speech); an example of a functional shift would be the development

of the noun commute from the verb commute.

Back-formation

Back-formation occurs when a real or supposed affix (that is, a prefix or suffix) is removed from a word to

create a new one. For example, the original name for a type of fruit was cherise, but some thought that word

sounded plural, so they began to use what they believed to be a singular form, cherry, and a new word was

born. The creation of the the verb enthuse from the noun enthusiasm is also an example of a

back-formation.

Blends

A blend is a word made by combining other words or parts of words in such a way that they overlap (as

motel from motor plus hotel) or one is infixed into the other (as chortle from

snort plus chuckle — the -ort- of the first being surrounded by the ch-…-le

of the second). The term blend is also sometimes used to describe words like brunch, from

breakfast plus lunch, in which pieces of the word are joined but there is no actual overlap. The

essential feature of a blend in either case is that there be no point at which you can break the word with everything

to the left of the breaking being a morpheme (a separately meaningful, conventionally combinable element) and

everything to the right being a morpheme, and with the meaning of the blend-word being a function of the meaning of

these morphemes. Thus, birdcage and psychohistory are not blends, but are instead compounds.

Acronymic Formations

An acronym is a word formed from the initial letters of a phrase. Some acronymic terms still clearly show their

alphabetic origins (consider FBI), but others are pronounced like words instead of as a succession of

letter names: thus NASA and NATO are pronounced as two syllable words. If the form is written

lowercase, there is no longer any formal clue that the word began life as an acronym: thus radar (‘radio

detecting and ranging’). Sometimes a form wavers between the two treatments: CAT scan pronounced either like

cat or C-A-T.

NOTE: No origin is more pleasing to the general reader than an acronymic one. Although acronymic etymologies are

perennially popular, many of them are based more in creative fancy than in fact. For an example of such an alleged

acronymic etymology, see the article on posh.

Transfer of Personal or Place Names

Over time, names of people, places, or things may become generalized vocabulary words. Thus did forsythia

develop from the name of botanist William Forsyth, silhouette from the name of Étienne de Silhouette, a

parsimonious French controller general of finances, and denim from serge de Nîmes (a fabric made

in Nîmes, France).

Imitation of Sounds

Words can also be created by onomatopoeia, the naming of things by a more or less exact reproduction of the

sound associated with it. Words such as buzz, hiss, guffaw, whiz, and

pop) are of imitative origin.

Folk Etymology

Folk etymology, also known as popular etymology, is the process whereby a word is altered so as to

resemble at least partially a more familiar word or words. Sometimes the process seems intended to «make sense of» a

borrowed foreign word using native resources: for example, the Late Latin febrigugia (a plant with medicinal

properties, etymologically ‘fever expeller’) was modified into English as feverfew.

Combining Word Elements

Also available to one who feels the need for a new word to name a new thing or express a new idea is the very

considerable store of prefixes, suffixes, and combining forms that already exist in English. Some of these are native

and others are borrowed from French, but the largest number have been taken directly from Latin or Greek, and they

have been combined in may different ways often without any special regard for matching two elements from the same

original language. The combination of these word elements has produced many scientific and technical terms of Modern

English.

Literary and Creative Coinages

Once in a while, a word is created spontaneously out of the creative play of sheer imagination. Words such as

boondoggle and googol are examples of such creative coinages, but most such inventive brand-new

words do not gain sufficiently widespread use to gain dictionary entry unless their coiner is well known enough so

his or her writings are read, quoted, and imitated. British author Lewis Carroll was renowned for coinages such

as jabberwocky, galumph, and runcible, but most such new words are destined to pass in

and out of existence with very little notice from most users of English.

An etymologist tracing the history of a dictionary entry must review the etymologies at existing main entries and

prepare such etymologies as are required for the main entries being added to the new edition. In the course of the

former activity, adjustments must sometimes be made either to incorporate a useful piece of information that has

been previously overlooked or to review the account of the word’s origin in light of new evidence. Such evidence

may be unearthed by the etymologist or may be the product of published research by other scholars. In writing new

etymologies, the etymologist must, of course, be alive to the possible languages from which a new term may have

been created or borrowed, and must be prepared to research and analyze a wide range of documented evidence and

published sources in tracing a word’s history. The etymologist must sift theories, often-conflicting theories of

greater or lesser likelihood, and try to evaluate the evidence conservatively but fairly to arrive at the soundest

possible etymology that the available information permits.

When all attempts to provide a satisfactory etymology have failed, an etymologist may have to declare that a word’s

origin is unknown. The label «origin unknown» in an etymology seldom means that the etymologist is unaware of various

speculations about the origin of a term, but instead usually means that no single theory conceived by the etymologist

or proposed by others is well enough backed by evidence to include in a serious work of reference, even when qualified

by «probably» or «perhaps.»

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

The etymology of a word refers to its origin and historical development: that is, its earliest known use, its transmission from one language to another, and its changes in form and meaning. Etymology is also the term for the branch of linguistics that studies word histories.

What’s the Difference Between a Definition and an Etymology?

A definition tells us what a word means and how it’s used in our own time. An etymology tells us where a word came from (often, but not always, from another language) and what it used to mean.

For example, according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, the definition of the word disaster is «an occurrence causing widespread destruction and distress; a catastrophe» or «a grave misfortune.» But the etymology of the word disaster takes us back to a time when people commonly blamed great misfortunes on the influence of the stars.

Disaster first appeared in English in the late 16th century, just in time for Shakespeare to use the word in the play King Lear. It arrived by way of the Old Italian word disastro, which meant «unfavorable to one’s stars.»

This older, astrological sense of disaster becomes easier to understand when we study its Latin root word, astrum, which also appears in our modern «star» word astronomy. With the negative Latin prefix dis- («apart») added to astrum («star»), the word (in Latin, Old Italian, and Middle French) conveyed the idea that a catastrophe could be traced to the «evil influence of a star or planet» (a definition that the dictionary tells us is now «obsolete»).

Is the Etymology of a Word Its True Definition?

Not at all, though people sometimes try to make this argument. The word etymology is derived from the Greek word etymon, which means «the true sense of a word.» But in fact the original meaning of a word is often different from its contemporary definition.

The meanings of many words have changed over time, and older senses of a word may grow uncommon or disappear entirely from everyday use. Disaster, for instance, no longer means the «evil influence of a star or planet,» just as consider no longer means «to observe the stars.»

Let’s look at another example. Our English word salary is defined by The American Heritage Dictionary as «fixed compensation for services, paid to a person on a regular basis.» Its etymology can be traced back 2,000 years to sal, the Latin word for salt. So what’s the connection between salt and salary?

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder tells us that «in Rome, a soldier was paid in salt,» which back then was widely used as a food preservative. Eventually, this salarium came to signify a stipend paid in any form, usually money. Even today the expression «worth your salt» indicates that you’re working hard and earning your salary. However, this doesn’t mean that salt is the true definition of salary.

Where Do Words Come From?

New words have entered (and continue to enter) the English language in many different ways. Here are some of the most common methods.

- Borrowing

The majority of the words used in modern English have been borrowed from other languages. Although most of our vocabulary comes from Latin and Greek (often by way of other European languages), English has borrowed words from more than 300 different languages around the world. Here are just a few examples:

futon (from the Japanese word for «bedclothes, bedding») - hamster (Middle High German hamastra)

- kangaroo (Aboriginal language of Guugu Yimidhirr, gangurru , referring to a species of kangaroo)

- kink (Dutch, «twist in a rope»)

- moccasin (Native American Indian, Virginia Algonquian, akin to Powhatan mäkäsn and Ojibwa makisin)

- molasses (Portuguese melaços, from Late Latin mellceum, from Latin mel, «honey»)

- muscle (Latin musculus, «mouse»)

- slogan (alteration of Scots slogorne, «battle cry»)

- smorgasbord (Swedish, literally «bread and butter table»)

- whiskey (Old Irish uisce, «water,» and bethad, «of life»)

- Clipping or Shortening

Some new words are simply shortened forms of existing words, for instance indie from independent; exam from examination; flu from influenza, and fax from facsimile. - Compounding

A new word may also be created by combining two or more existing words: fire engine, for example, and babysitter. - Blends

A blend, also called a portmanteau word, is a word formed by merging the sounds and meanings of two or more other words. Examples include moped, from mo(tor) + ped(al), and brunch, from br(eakfast) + (l)unch. - Conversion or Functional Shift

New words are often formed by changing an existing word from one part of speech to another. For example, innovations in technology have encouraged the transformation of the nouns network, Google, and microwave into verbs. - Transfer of Proper Nouns

Sometimes the names of people, places, and things become generalized vocabulary words. For instance, the noun maverick was derived from the name of an American cattleman, Samuel Augustus Maverick. The saxophone was named after Sax, the surname of a 19th-century Belgian family that made musical instruments. - Neologisms or Creative Coinages

Now and then, new products or processes inspire the creation of entirely new words. Such neologisms are usually short lived, never even making it into a dictionary. Nevertheless, some have endured, for example quark (coined by novelist James Joyce), galumph (Lewis Carroll), aspirin (originally a trademark), grok (Robert A. Heinlein). - Imitation of Sounds

Words are also created by onomatopoeia, naming things by imitating the sounds that are associated with them: boo, bow-wow, tinkle, click.

Why Should We Care About Word Histories?

If a word’s etymology is not the same as its definition, why should we care at all about word histories? Well, for one thing, understanding how words have developed can teach us a great deal about our cultural history. In addition, studying the histories of familiar words can help us deduce the meanings of unfamiliar words, thereby enriching our vocabularies. Finally, word stories are often both entertaining and thought provoking. In short, as any youngster can tell you, words are fun.

Библиографическое описание:

Жумакулова, Ш. К. The etymology concept in linguistics / Ш. К. Жумакулова. — Текст : непосредственный // Молодой ученый. — 2020. — № 51 (341). — С. 56-57. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/341/76828/ (дата обращения: 14.04.2023).

This article discusses the etymology of linguistics. Along with the department of etymology, special attention is paid to the concept of etymology, the history of the origin of words, their original meaning and significance.

Keywords:

etymology, etymon, etymological analysis, diachronic, synchronous.

In linguistics etymology is the study of the origin of a word and is based on the laws of historical changes in word structure and its meanings, sound changes, and morphological changes in words.

Etymology is one of the oldest branches of linguistics and deals with the history of the origin of words, as well as the meanings of words learned from artificial, compound and foreign languages. Etymology takes into account both aspects of a word, its form and meaning. Etymology is the study of the origin of words. The word is a combination of the Greek etymology, etymon — «truth» and logos — «word». [3]

According to encyclopedic dictionaries, etymology originated in ancient Greece in Plato’s Cratilus, where the term «etymology» was coined in connection with the Stoics. [2]

According to Karpenko, V. A. Zvegintsev defined the history of the science of etymology, returning to Plato’s Cratilus, arguing that the «natural» or conditional nature of words and the dispute over their observance were primarily true, i.e. the point of view that reflects the essence of what they mean, the Stoics put forward a new task before the ancient linguistics — the discovery of the true essence or nature of words. Thus, etymology implied that a new linguistic discipline, or the science of the true meaning of a word, was encouraged for its birth. [4]

Etymology is a very ancient branch of linguistics, and BC philosophers and philologists also studied the early history of the origin of words. The term «etymology» is probably associated with the names of the ancient Roman scholars Chrysippus and Varron. The true and original meanings and forms of words are determined by comparing them with words in other languages and dialects that have the same root as the history of the language. [1] It explores the previous meanings and forms of words.

According to I. A. Buduen de Courtenay, etymology is defined as a science that deals with historical relations in terms of the structure of words and their essential parts. The scholar argues that the application of the concept of chronological sequence to individual parts of the grammar of any language should take into account the history of the language when comparing the state of a single material in different periods.

O. N. Trubachev explains that the etymology of almost every word is related to comparative grammar, and that this relationship is almost always complex and multifaceted, as etymology is a set of actions based on a set of data derived from comparative grammar. The etymology is provided by comparative grammar, and it can still add clarity and add much. Each etymology works with comparative phonetics, morphology, and word formation facts.

A. S. Karimov calls etymology the «biography» of words, the study of the history of their origin. [5] The true and original meanings and forms of words are determined by comparing them with words in other languages and dialects that have the same root. In this case, the previous meanings and forms of words are studied in depth.

The term «etymology» is used in linguistics in two senses: lexicology, the study of the history of the origin of words in a particular language, and the first meaning and form of the word.

It is easy to identify the origin of new words, but it is much harder to know when an old word appeared and from which language or dialect it was derived. In determining the origin of a word, the word is compared with the sound structure and meaning of words in related languages.

The subject of etymology as a branch of linguistics is the study of the sources and processes of formation of the vocabulary of a language, including the earliest stages of its existence. [2] Over time, the words of a language change according to certain historical patterns, which obscures the original form of the word. The etymologist must create this form, relying on the materials of the relevant languages, and explain how the word came to be in the modern form.

Historical changes in words often distort the original form and meaning of the word, and the character of the word undermines the underlying motivation, that is, it determines the difficulty of reconstructing the relationship between the original form and the meaning of the word.

The purpose of the etymological analysis of a word is to determine when, in what language, on the basis of which word formation model, on the basis of which linguistic material, in what form and in what sense the word appeared, as well as on its initial form and meaning determines what historical changes have defined the present form and meaning. Reconstruction of the original form and meaning of the word is actually the subject of etymological analysis.

Etymological analysis allows the speaker to restore the meaning of a word that was previously unknown to him, reveals its origin, allows to restore the origin of words in a foreign language. History from any moment of life helps maintain the account. The history of language as a scientific history is the study of the history of social thought without a general basis for the history of discipline, material and spiritual culture, and, above all, the imagination.

Linguist V. I. Abaev described the main functions of scientific etymological analysis as follows:

− to compare the basic, non-derivative words of a given language with the words of these opposite languages and to study the history of the form and meaning of the word according to the main language;

− to designate for Latin words within a given language and their components (roots, stems, affixes) in the language parts;

− to determine the source of borrowing for borrowed words.

The etymology of linguistics is very complex and requires a lot of time and patience. Historically, we have to admit that there is a connection between words and things from a diachronic point of view. But their history is so deep that the ability to identify all of them is practically impossible. The main reason for this conclusion is that just as everything in the world is changing and evolving, as well as words. With this in mind, it is concluded that there is no connection between words and things, given the current state of language development, that is, from a synchronic point of view.

As can be seen from the above, etymology is closely related to areas of linguistics such as lexicology. But for an etymologist to be successful, he must have in-depth knowledge in almost all areas of linguistics. He must compare the data of different languages, both modern and ancient, with his own methods in comparative historical linguistics.

References:

- Abduazizov A. A. Tilshunoslik nazariyasiga kirish. — Sharq, Toshkent — 2010. — 81p.

- Варбот Ж. Ж. Этимология. Большая российская энциклопедия. Том 35. Москва, 2017. — 489–490с.

- Irisqulov M. T. Tilshunoslikka kirish. Yangi asr avlodi., 2009. — 96–101p.

- Карпенко У. А. Трансляция смысла и трансформация значений первокорня: монография. — Киев: Освита Украины, 2013. — 496 с.

- Karimov S. A. Tilshunoslik nazariyasi. Samarqand — 2012. — 21p.

Основные термины (генерируются автоматически): инструмент, ГОСТ, информация, режущий инструмент, система кодирования, автоматизированное производство, вспомогательный инструмент, инструментальный блок, код, маркировка.

Etymology is the study of the history of words, their origin, and how their forms and meanings change over time. For languages that have a long written history, etymologists use texts to understand how words were used during earlier periods and when they entered a given language. Etymologists also use comparative linguistics to reconstruct information about languages when no direct information is available.

Where do new words come from?

New words come into being in a language through three basic mechanisms: borrowings, word formation and sound symbolism.

Borrowing

Borrowing means words are taken from other languages. Words borrowed this way are called loanwords. It is extremely common: over half of all English words have been borrowed from French and Latin, and loanwords from Chinese are important parts of Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese.

Loanwords are usually adapted to fit the phonology and spelling of the language they are borrowed into. English words in Japanese are often barely recognizable. For example, バレーボール (borēboru) comes from English and means «volleyball», but v and l have been replaced by b and r because these sounds do not exist in Japanese, and a vowel has been added at the end because Japanese words cannot end in any consonant but n. These changes were not deliberate: borēboru is what happens naturally when Japanese speakers say volleyball according to the pronunciation rules of their language.

A loanword can have a different meaning than it had in the original language: the Russian word портфель portfel′ (“briefcase”) comes from the French portefeuille, which means “wallet”. Pseudo-anglicisms are common in many languages: Handy means “mobile phone” in German, which is only indirectly related to the meaning of “handy” in English.

Words can also be reborrowed: that is a word can go back and forth between languages. For example, the French word cinéma was taken from the Greek word κίνημα kínima, which means “movement”, later Greek reborrowed the same word from French and respelled it σινεμά sinemá.

Word formation

Languages have lots of ways of creating new words. One of them is derivation, that is creating a new word on the basis of an existing word, other types include compound words, which are formed by putting words together.

Other ways include acronyms (“radar” comes from “radio detection and ranging”), clipping (“ad” from “advertisement”) and portmanteaus (“brunch” = “breakfast” + “lunch”)

Read more about word formation in Morphology.

Sound symbolism

Some words such as “click” are examples of onomatopoeia.

How do words evolve?

Everything about languages evolves: pronunciation, grammar and words. New words appear, old words disappear and existing words change.

Knowing the history of words is relatively easy when old written documents exist, but when they don’t, the comparative method allows linguist to reconstruct ancient languages by comparing their descendants. One key feature of language evolution is regular sound change: changes in pronunciation don’t affect random words, but the entire language. As an example, the ancestor of modern Slavic languages had a G sound. It was maintained in most languages, but in some of them, such as Czech and Slovak, it gradually changed to H: the word for “mountain” is gora in Russian and Slovene, but hora in Czech and Slovak. Sound changes are not always this easy, because sometimes sounds are modified only in particular contexts (at the end of a word, before a vowel, etc.), but this is the general principle that linguists use to compare languages and reconstruct their ancestors.

Thousands of years of evolution can change words so much that they are unrecognizable: the Proto-Indo-European *ḱm̥tóm (the symbol * is used by linguists to indicate that a word is reconstructed and has never been found in a text), which means “hundred”, turned into such different words as šimtas in Lithuanian, sto in Slavic languages, cent in French, صد sad in Persian and εκατό ekató in Greek.

Reconstructing languages is made more difficult by borrowings and by the fact that the meanings of words change: “decimate” now means “destroy almost completely”, but originally meant “kill one in ten”, and the French word travail (“work”) comes from the Latin tripalium (an instrument of torture).

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

Best Answer

Copy

Etymology

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the study of the history of words called?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

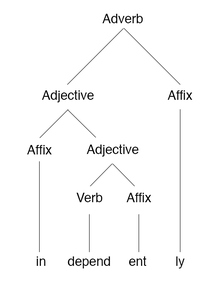

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)