Backpacker – slang term for nerdy rappers or can be even used to categorise a type of hip hop where rappers use complex rhyme schemes, large syllable words and tend to have politically inflected lyrics.

Beats – the musical (usually electronic) accompaniment to rapping.

Biting – term used to describe inauthentic actions of rappers and DJs. It is essentially plagiarising, ripping off another person’s style, moves or intellectual material and results in a great loss of respect from other hip hoppers.

Boom Bap – a style of hip hop music signified by a hard bass drum and snapping snare and usually refers to ‘old skool’ tracks.

Breaks or breakbeat – sample of a syncopated drum beat usually lifted as an excerpt from a record.

Crew – an assemblage of people in a rap group.

Cypher – rap equivalent of a ‘jamming session’ in which informal gathering of rappers take it in turns to rap. Can either be a cappella, accompanied to music or with a beatboxer. Lyrics can either be freestyled or pre-written verses.

Dubstep – form of electronic dance music that originated in South London in the late 1990s. It is characterised by heavy bass lines and sub-bass frequencies.

Drum ‘n’ Bass – type of electronic music that emerged in the UK during the 1990s. The genre has 160-180 beats per minute and heavy bass lines.

Flow – refers to the rhythm of the rhyme and how closely rappers keep in time to the music, as well their intonation.

Freestyle – rapping spontaneous and unwritten lyrics.

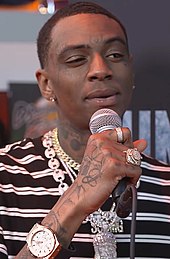

Gangsta – a type of rapper who is usually distinguishable by their clothes and style. They typically wear ‘bling’ (gaudy jewellery) and generally produce lyrics espousing violence, machismo and misogyny.

Garage – genre of electronic music based on Chicago house music but developed in UK in early 1990s. It comprises of a syncopated rhythm and features MCs rapping. It has largely been subsumed into other UK genres such as dubstep, grime and drum ‘n’ bass.

Grime – is essentially a cross between hip hop and speed garage and developed in East London during the 2000s. It is characterised by a fast tempo of 140 beats per minute and features MCs rapping.

Hip Hop – is a cultural phenomenon made up of four distinct elements – rapping, DJing, breakdancing and graffiti. In terms of music, it comprises the rapping and DJ components.

Hip Hop Head – someone who identifies as being a hip hop fan. This includes artists, DJs and other stakeholders.

Hip Hop Nation – collective term for the global hip hop community, encompassing all the local scenes in countries across the world.

Jungle – genre of music that gained popularity in Britain during the 1990s. It is characterised by chopped up electronic breaks and heavy basslines and sometimes features ragga vocals. It is often considered the pre-cursor to drum ‘n’ bass.

MC/emcee – alternative terms for ‘rapper’.[1] MC is an abbreviation of ‘Master of Ceremonies’, though some people now say it stands for ‘mic controller’ (the one with the microphone).

Old Skool – contested term but in general refers to hip hop made between the period of the 1970s to 1980s.

Open Mic – public event in which music and a mic (microphone) are provided for any artists to perform in front of others.

Rap Battle – a competition usually between two rappers who fight against each other using lyrics.

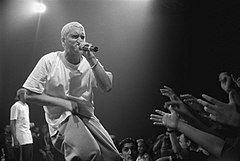

Rapper – a person who expresses himself through rhythmic spoken word lyrics.

Rapping – a form of vocal delivery in which rhyming lyrics are spoken or ‘rapped’ in time with a continuous back beat.

Rhyme Schemes – the pattern of the rhyme between lines of a song (the same as poetry).

Wordplay – how a rapper creatively uses lyrics within a song. For example, incorporating words with double meanings and puns for humour or including punch lines.

[1] In grime and jungle music the terms are not used interchangeably as in hip hop, only ‘MC’ is used.

«Rap music» redirects here. For the form of vocal delivery associated with hip hop music, see rapping. For the Killer Mike album, see R.A.P. Music.

| Hip hop | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Early 1970s, The Bronx, New York City, U.S.[2] |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Derivative forms |

|

| Subgenres | |

(complete list) |

|

| Fusion genres | |

Regional fusion genres

|

|

| Regional scenes | |

|

Regional scenes African

Asian

Middle Eastern

European

North American

Oceanic

South American

|

|

| Local scenes | |

|

Local scenes

|

|

| Other topics | |

|

|

Hip hop music or hip-hop music, also known as rap music and formerly known as disco rap,[5][6] is a genre of popular music that originated in the Bronx[7][8][9][10] borough of New York City in the early 1970s. It consists of stylized rhythmic music (usually built around drum beats) that commonly accompanies rapping, a rhythmic and rhyming speech that is chanted.[11] It developed as part of hip hop culture, a subculture defined by four key stylistic elements: MCing/rapping, DJing/scratching with turntables, break dancing, and graffiti writing.[12][13][14] Other elements include sampling beats or bass lines from records (or synthesized beats and sounds), and rhythmic beatboxing. While often used to refer solely to rapping, «hip hop» more properly denotes the practice of the entire subculture.[15][16] The term hip hop music is sometimes used synonymously with the term rap music,[11][17] though rapping is not a required component of hip hop music; the genre may also incorporate other elements of hip hop culture, including DJing, turntablism, scratching, beatboxing, and instrumental tracks.[18][19]

Hip hop as both a musical genre and a culture was formed during the 1970s when block parties became increasingly popular in New York City, particularly among African American youth residing in the Bronx.[20] At block parties, DJs played percussive breaks of popular songs using two turntables and a DJ mixer to be able to play breaks from two copies of the same record, alternating from one to the other and extending the «break».[21] Hip hop’s early evolution occurred as sampling technology and drum machines became widely available and affordable. Turntablist techniques such as scratching and beatmatching developed along with the breaks. Rapping developed as a vocal style in which the artist speaks or chants along rhythmically with an instrumental or synthesized beat.

Hip hop music was not officially recorded for play on radio or television until 1979, largely due to poverty during the genre’s birth and lack of acceptance outside ghetto neighborhoods.[22] Old school hip hop was the first mainstream wave of the genre, marked by its disco influence and party-oriented lyrics. The 1980s marked the diversification of hip hop as the genre developed more complex styles and spread around the world. New school hip hop was the genre’s second wave, marked by its electro sound, and led into golden age hip hop, an innovative period between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s that also developed hip hop’s own album era. The gangsta rap subgenre, focused on the violent lifestyles and impoverished conditions of inner-city African American youth, gained popularity at this time. West Coast hip hop was dominated by G-funk in the early-mid 1990s, while East Coast hip hop was dominated by jazz rap, alternative hip hop, and hardcore hip hop. Hip hop continued to diversify at this time with other regional styles emerging, such as Southern rap and Atlanta hip hop. Hip hop became a best-selling genre in the mid-1990s and the top-selling music genre by 1999.

The popularity of hip hop music continued through the late 1990s to early-2000s «bling era» with hip hop influences increasingly finding their way into other genres of popular music, such as neo soul, nu metal, and R&B. The United States also saw the success of regional styles such as crunk, a Southern genre that emphasized the beats and music more than the lyrics, and alternative hip hop began to secure a place in the mainstream, due in part to the crossover success of its artists. During the late 2000s and early 2010s «blog era», rappers were able to build up a following through online methods of music distribution, such as social media and blogs, and mainstream hip hop took on a more melodic, sensitive direction following the commercial decline of gangsta rap. The trap and mumble rap subgenres have become the most popular form of hip hop during the mid-late 2010s and early 2020s. In 2017, rock music was usurped by hip hop as the most popular genre in the United States.[23][24][25]

Etymology

The words «hip» and «hop» have a long history behind the two words being used together. In the 1950s, older folks referred to teen house parties as «hippity hops».[26] The creation of the term hip hop is often credited to Keef Cowboy, rapper with Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.[27] However, Lovebug Starski, Keef Cowboy, and DJ Hollywood used the term when the music was still known as disco rap.[28] It is believed that Cowboy created the term while teasing a friend who had just joined the U.S. Army, by scat singing the words «hip/hop/hip/hop» in a way that mimicked the rhythmic cadence of soldiers marching.[27] Cowboy later worked the «hip hop» cadence into a part of his stage performance. For example, he would say something along the lines of «I said a hip-hop, a hibbit, hibby-dibby, hip-hip-hop and you don’t stop.»[26] which was quickly used by other artists such as The Sugarhill Gang in «Rapper’s Delight».[27] Universal Zulu Nation founder Afrika Bambaataa, also known as «the Godfather», is credited with first using the term to describe the subculture in which the music belonged; although it is also suggested that it was a derogatory term to describe the type of music.[29] The term was first used in print to refer to the music by reporter Robert Flipping, Jr. in a February 1979 article in the New Pittsburgh Courier,[30][31] and to refer to the culture in a January 1982 interview of Afrika Bambaataa by Michael Holman in the East Village Eye.[32] The term gained further currency in September of that year in another Bambaataa interview in The Village Voice,[33] by Steven Hager, later author of a 1984 history of hip hop.[34]

There are disagreements about whether or not the terms «hip hop» and «rap» can be used interchangeably, even amongst its most knowledgeable proponents.[6] The most common view is that hip-hop is a cultural movement that emerged in the South Bronx in New York City during the 1970s, with MCing (or rapping) being one of the primary four elements.[6] Hip hop’s other three essential elements are graffiti art (or aerosol art), break dancing, and DJing. Rap music has become by far the most celebrated expression of hip hop culture, due to being the easiest to market to a mass audience.[6]

Precursors

Musical genres from which hip hop developed include funk, blues, jazz and rhythm and blues recordings from the 60s, 50s, and earlier, including several records by Bo Diddley.[citation needed]

Muhammad Ali’s 1963 spoken-word album I Am the Greatest is regarded by some writers as an early example of hip hop.[35][36][better source needed] Pigmeat Markham’s 1968 single «Here Comes the Judge» is one of several songs said to be the earliest hip hop record.[37] Leading up to hip hop, there were spoken-word artists such as the Last Poets who released their debut album in 1970, and Gil Scott-Heron, who gained a wide audience with his 1971 track «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised». These artists combined spoken word and music to create a kind of «proto-rap» vibe.[38]

1973–1979: Early years

Origins

Hip hop as music and culture formed during the 1970s in New York City from the multicultural exchange between African Americans and children of immigrants from countries in the Caribbean, most notably Jamaica.[39] Hip hop music in its infancy has been described as an outlet and a voice for the disenfranchised youth of marginalized backgrounds and low-income areas, as the hip hop culture reflected the social, economic and political realities of their lives.[40][41] Many of the people who helped establish hip hop culture, including DJ Kool Herc, DJ Disco Wiz, Grandmaster Flash, and Afrika Bambaataa were of Latin American or Caribbean origin.

It is hard to pinpoint the exact musical influences that most affected the sound and culture of early hip hop because of the multicultural nature of New York City. Hip hop’s early pioneers were influenced by a mix of cultures due to the diversity of New York City.[42] New York City experienced a heavy Jamaican hip hop influence during the 1990s. This influence was brought on by cultural shifts particularly because of the heightened immigration of Jamaicans to New York City and the American-born Jamaican youth who were coming of age during the 1990s.

DJ Kool Herc, of Jamaican background, is recognized as one of the earliest hip hop DJs and artists. Some credit him with officially originating hip hop music through his 1973 «Back to School Jam».[43]

In the 1970s, block parties were increasingly popular in New York City, particularly among African American, Caribbean and Latino youth residing in the Bronx. Block parties incorporated DJs, who played popular genres of music, especially funk and soul music. Due to the positive reception, DJs began isolating the percussive breaks of popular songs. This technique was common in Jamaican dub music,[44] and was largely introduced into New York by immigrants from the Caribbean, including DJ Kool Herc, one of the pioneers of hip hop.[45][46] To be clear, Herc has repeatedly denied there being any direct connections between Jamaican musical traditions and early hip hop, stating that his own biggest influence was James Brown, from whom he says rap originated.[47] Even before moving to the U.S., Herc says his biggest influences came from American music:

I was listening to American music in Jamaica and my favorite artist was James Brown. That’s who inspired me. A lot of the records I played were by James Brown.[48]

Herc also says that he was not influenced by Jamaican sound system parties, as he was too young to experience them when he was in Jamaica.[49]

Because the percussive breaks in funk, soul and disco records were generally short, Herc and other DJs began using two turntables to extend the breaks. On August 11, 1973, DJ Kool Herc was the DJ at his sister’s back-to-school party. He extended the beat of a record by using two record players, isolating the percussion «breaks» by using a mixer to switch between the two records. Herc’s experiments with making music with record players became what we now know as breaking or «scratching».[50]

A second key musical element in hip hop music is emceeing (also called MCing or rapping). Emceeing is the rhythmic spoken delivery of rhymes and wordplay, delivered at first without accompaniment and later done over a beat. This spoken style was influenced by the African American style of «capping», a performance where men tried to outdo each other in originality of their language and tried to gain the favor of the listeners.[51] The basic elements of hip hop—boasting raps, rival «posses» (groups), uptown «throw-downs», and political and social commentary—were all long present in African American music. MCing and rapping performers moved back and forth between the predominance of songs packed with a mix of boasting, ‘slackness’ and sexual innuendo and a more topical, political, socially conscious style. The role of the MC originally was as a Master of Ceremonies for a DJ dance event. The MC would introduce the DJ and try to pump up the audience. The MC spoke between the DJ’s songs, urging everyone to get up and dance. MCs would also tell jokes and use their energetic language and enthusiasm to rev up the crowd. Eventually, this introducing role developed into longer sessions of spoken, rhythmic wordplay, and rhyming, which became rapping.

By 1979 hip hop music had become a mainstream genre. It spread across the world in the 1990s with controversial «gangsta» rap.[52] Herc also developed upon break-beat deejaying,[53] where the breaks of funk songs—the part most suited to dance, usually percussion-based—were isolated and repeated for the purpose of all-night dance parties. This form of music playback, using hard funk and rock, formed the basis of hip hop music. Campbell’s announcements and exhortations to dancers would lead to the syncopated, rhymed spoken accompaniment now known as rapping. He dubbed his dancers «break-boys» and «break-girls», or simply b-boys and b-girls. According to Herc, «breaking» was also street slang for «getting excited» and «acting energetically».[54]

DJs such as Grand Wizzard Theodore, Grandmaster Flash, and Jazzy Jay refined and developed the use of breakbeats, including cutting and scratching.[56] As turntable manipulation continued to evolve a new technique that came from it was needle dropping. Needle dropping was created by Grandmaster Flash, it is prolonged short drum breaks by playing two copies of a record simultaneously and moving the needle on one turntable back to the start of the break while the other played.[57] The approach used by Herc was soon widely copied, and by the late 1970s, DJs were releasing 12-inch records where they would rap to the beat. Popular tunes included Kurtis Blow’s «The Breaks» and the Sugarhill Gang’s «Rapper’s Delight».[58] Herc and other DJs would connect their equipment to power lines and perform at venues such as public basketball courts and at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, Bronx, New York, now officially a historic building.[59] The equipment consisted of numerous speakers, turntables, and one or more microphones.[60] By using this technique, DJs could create a variety of music, but according to Rap Attack by David Toop «At its worst the technique could turn the night into one endless and inevitably boring song».[61] KC the Prince of Soul, a rapper-lyricist with Pete DJ Jones, is often credited with being the first rap lyricist to call himself an «MC».[62]

Street gangs were prevalent in the poverty of the South Bronx, and much of the graffiti, rapping, and b-boying at these parties were all artistic variations on the competition and one-upmanship of street gangs. Sensing that gang members’ often violent urges could be turned into creative ones, Afrika Bambaataa founded the Zulu Nation, a loose confederation of street-dance crews, graffiti artists, and rap musicians. By the late 1970s, the culture had gained media attention, with Billboard magazine printing an article titled «B Beats Bombarding Bronx», commenting on the local phenomenon and mentioning influential figures such as Kool Herc.[63] The New York City blackout of 1977 saw widespread looting, arson, and other citywide disorders especially in the Bronx[64] where a number of looters stole DJ equipment from electronics stores. As a result, the hip hop genre, barely known outside of the Bronx at the time, grew at an astounding rate from 1977 onward.[65]

DJ Kool Herc’s house parties gained popularity and later moved to outdoor venues to accommodate more people. Hosted in parks, these outdoor parties became a means of expression and an outlet for teenagers, where «instead of getting into trouble on the streets, teens now had a place to expend their pent-up energy.»[66] Tony Tone, a member of the Cold Crush Brothers, stated that «hip hop saved a lot of lives».[66] For inner-city youth, participating in hip hop culture became a way of dealing with the hardships of life as minorities within America, and an outlet to deal with the risk of violence and the rise of gang culture. MC Kid Lucky mentions that «people used to break-dance against each other instead of fighting».[67][68] Inspired by DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa created a street organization called Universal Zulu Nation, centered around hip hop, as a means to draw teenagers out of gang life, drugs and violence.[66]

The lyrical content of many early rap groups focused on social issues, most notably in the seminal track «The Message» by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, which discussed the realities of life in the housing projects.[69] «Young black Americans coming out of the civil rights movement have used hip hop culture in the 1980s and 1990s to show the limitations of the Hip Hop Movement.»[70] Hip hop gave young African Americans a voice to let their issues be heard; «Like rock-and-roll, hip hop is vigorously opposed by conservatives because it romanticises violence, law-breaking, and gangs».[70] It also gave people a chance for financial gain by «reducing the rest of the world to consumers of its social concerns.»[70]

In late 1979, Debbie Harry of Blondie took Nile Rodgers of Chic to such an event, as the main backing track used was the break from Chic’s «Good Times».[58] The new style influenced Harry, and Blondie’s later hit single from 1981 «Rapture» became the first single containing hip hop elements to hit number one on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100—the song itself is usually considered new wave and fuses heavy pop music elements, but there is an extended rap by Harry near the end.

Boxer Muhammad Ali, as an influential African American celebrity, was widely covered in the media. Ali influenced several elements of hip hop music. Both in the boxing ring and in media interviews, Ali became known in the 1960s for being «rhyming trickster». Ali used a «funky delivery» for his comments, which included «boasts, comical trash talk, [and] the endless quotabl[e]» lines.[71] According to Rolling Stone, his «freestyle skills» (a reference to a type of vocal improvisation in which lyrics are recited with no particular subject or structure) and his «rhymes, flow, and braggadocio» would «one day become typical of old school MCs» like Run–D.M.C. and LL Cool J,[72] the latter citing Ali as an influence.[71] Hip hop music in its infancy has been described as an outlet and a «voice» for the disenfranchised youth of low-income and marginalized economic areas,[40] as the hip hop culture reflected the social, economic and political realities of their lives.[41]

Technology

Two hip hop DJs creating new music by mixing tracks from multiple record players. Pictured are DJ Hypnotize (left) and Baby Cee (right).

Hip hop’s early evolution occurred around the time that sampling technology and drum-machines became widely available to the general public at a cost that was affordable to the average consumer—not just professional studios. Drum-machines and samplers were combined in machines that came to be known as MPC’s or ‘Music Production Centers’, early examples of which would include the Linn 9000. The first sampler that was broadly adopted to create this new kind of music was the Mellotron used in combination with the TR-808 drum machine. Mellotrons and Linn’s were succeeded by the AKAI, in the late 1980s.[73]

Turntablist techniques – such as rhythmic «scratching» (pushing a record back and forth while the needle is in the groove to create new sounds and sound effects, an approach attributed to Grand Wizzard Theodore[74][75]), beat mixing and/or beatmatching, and beat juggling – eventually developed along with the percussion breaks, creating a musical accompaniment or base that could be rapped over in a manner similar to signifying.

Introduction of rapping

Rapping, also referred to as MCing or emceeing, is a vocal style in which the artist speaks lyrically and rhythmically, in rhyme and verse, generally to an instrumental or synthesized beat. Beats, almost always in 4/4 time signature, can be created by sampling and/or sequencing portions of other songs by a producer. They also incorporate synthesizers, drum machines, and live bands. Rappers may write, memorize, or improvise their lyrics and perform their works a cappella or to a beat. Hip hop music predates the introduction of rapping into hip hop culture, and rap vocals are absent from many hip hop tracks, such as «Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop)» by Man Parrish; «Chinese Arithmetic» by Eric B. & Rakim; «Al-Naafiysh (The Soul)» and «We’re Rocking the Planet» by Hashim; and «Destination Earth» by Newcleus. However, the majority of the genre has been accompanied by rap vocals, such as the Sci-fi influenced electro hip hop group Warp 9.[76] Female rappers appeared on the scene in the late 1970s and early 80s, including Bronx artist MC Sha-Rock, member of the Funky Four Plus One, credited with being the first female MC[77] and the Sequence, a hip hop trio signed to Sugar Hill Records, the first all female group to release a rap record, Funk You Up.[citation needed]

The roots of rapping are found in African American music and bear similarities to traditional African music, particularly that of the griots[78] of West African culture.[79] The African American traditions of signifyin’, the dozens, and jazz poetry all influence hip hop music, as well as the call and response patterns of African and African American religious ceremonies. Early popular radio disc jockeys of the Black-appeal radio period broke into broadcast announcing by using these techniques under the jive talk of the post WWII swing era in the late 1940s and the 1950s.[80] DJ Nat D. was the M.C. at one of the most pitiless places for any aspiring musician trying to break into show business, Amateur Night at the Palace theatre on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee. There he was master of ceremonies from 1935 until 1947 along with his sideman, D.J.Rufus Thomas. It was there he perfected the dozens, signifyin’ and the personality jock jive patter that would become his schtick when he became the first black radio announcer on the air south of the Mason–Dixon line.[81] Jive popularized black appeal radio, it was the language of the black youth, the double entendres and slightly obscene wordplay was a godsend to radio, re-invigorating ratings at flagging outlets that were losing audience share and flipping to the new format of R&B with black announcers. The 10% of African Americans who heard his broadcasts found that the music he promoted on radio in 1949 was also in the jukeboxes up north in the cities. They were also finding other D.J’s like Chicago’s Al Benson on WJJD, Austin’s Doctor Hep Cat on KVET and Atlanta’s Jockey Jack on WERD speaking the same rhyming, cadence laden rap style.[82] Once the white owned stations realized the new upstarts were grabbing their black market share and that Big Band and swing jazz was no longer ‘hip’, some white D.J’s emulated the southern ‘mushmouth’ and jive talk, letting their audience think they too were African American, playing the blues and Be-Bop.[83] John R Richbourg had a southern drawl that listeners to Nashville’s WLAC[84] nighttime R&B programming were never informed belonged not to a black D.J., as were other white D.J’s at the station. Dr. Hep Cat’s rhymes were published in a dictionary of jive talk, The Jives of Dr. Hepcat, in 1953. Jockey jack is the infamous Jack the Rapper of Family Affair fame, after his radio convention that was a must attend for every rap artist in the 1980s and 1990s[85] These jive talking rappers of the 1950s black appeal radio format were the source and inspiration of Soul singer James Brown, and musical ‘comedy’ acts such as Rudy Ray Moore, Pigmeat Markham and Blowfly that are often considered «godfathers» of hip hop music.[86] Within New York City, performances of spoken-word poetry and music by artists such as the Last Poets, Gil Scott-Heron[87] and Jalal Mansur Nuriddin had a significant impact on the post-civil rights era culture of the 1960s and ‘1970s, and thus the social environment in which hip hop music was created.

Jamaican origins of outdoor sound systems

AM radio at many stations were limited by the ‘broadcast Day’ as special licenses were required to transmit at night. Those that had such licenses were heard far out to sea and in the Caribbean, where Jocko Henderson and Jockey Jack were American DJs who were listened to at night from broadcast transmitters located in Miami, Florida. Jocko came to have an outsized influence on Jamaican Emcees during the ’50s as the R&B music played on the Miami stations was different from that played on JBC, which re-broadcast BBC and local music styles. In Jamaica, DJs would set up large roadside sound systems in towns and villages, playing music for informal gatherings, mostly folks who wandered down from country hills looking for excitement at the end of the week. There the DJs would allow ‘Toasts’ by an Emcee, which copied the style of the American DJs listened to on AM transistor radios. It was by this method that Jive talk, rapping and rhyming was transposed to the island and locally the style was transformed by ‘Jamaican lyricism’, or the local patois.

Hip hop as music and culture formed during the 1970s in New York City from the multicultural exchange between African American youth from the United States and young immigrants and children of immigrants from countries in the Caribbean.[39] Some were influenced by the vocal style of the earliest African American radio MCs (including Jocko Henderson’s Rocket Ship Show of the 1950s, which rhymed and was influenced by scat singing), which could be heard over the radio in Jamaica.

The first records by Jamaican DJs, including Sir Lord Comic (The Great Wuga Wuga, 1967) came as part of the local dance hall culture, which featured ‘specials,’ unique mixes or ‘versions’ pressed on soft discs or acetate discs, and rappers (called DJs) such as King Stitt, Count Machuki, U-Roy, I-Roy, Big Youth and many others. Recordings of talk-over, which is a different style from the dancehall’s DJ style, were also made by Jamaican artists such as Prince Buster and Lee «Scratch» Perry (Judge Dread) as early as 1967, somehow rooted in the ‘talking blues’ tradition. The first full-length Jamaican DJ record was a duet on a Rastafarian topic by Kingston ghetto dwellers U-Roy and Peter Tosh named Righteous Ruler (produced by Lee «Scratch» Perry in 1969). The first DJ hit record was Fire Corner by Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system DJ, King Stitt that same year; 1970 saw a multitude of DJ hit records in the wake of U-Roy’s early, massive hits, most famously Wake the Town and many others. As the tradition of remix (which also started in Jamaica where it was called ‘version’ and ‘dub’) developed, established young Jamaican DJ/rappers from that period, who had already been working for sound systems for years, were suddenly recorded and had many local hit records, widely contributing to the reggae craze triggered by Bob Marley’s impact in the 1970s. The main Jamaican DJs of the early 1970s were King Stitt, Samuel the First, Count Machuki, Johnny Lover (who ‘versioned’ songs by Bob Marley and the Wailers as early as 1971), Dave Barker, Scotty, Lloyd Young, Charlie Ace and others, as well as soon-to-be reggae stars U-Roy, Dennis Alcapone, I-Roy, Prince Jazzbo, Prince Far I, Big Youth and Dillinger. Dillinger scored the first international rap hit record with Cocaine in my Brain in 1976 (based on the Do It Any Way You Wanna Do rhythm by the People’s Choice as re-recorded by Sly and Robbie), where he even used a New York accent, consciously aiming at the new NYC rap market. The Jamaican DJ dance music was deeply rooted in the sound system tradition that made music available to poor people in a very poor country where live music was only played in clubs and hotels patronized by the middle and upper classes. By 1973 Jamaican sound system enthusiast DJ Kool Herc moved to the Bronx, taking with him Jamaica’s sound system culture, and teamed up with another Jamaican, Coke La Rock, at the mike. Although other influences, most notably musical sequencer Grandmaster Flowers of Brooklyn and Grandwizard Theodore of the Bronx contributed to the birth of hip hop in New York, and although it was downplayed in most US books about hip hop, the main root of this sound system culture was Jamaican. The roots of rap in Jamaica are explained in detail in Bruno Blum’s book, ‘Le Rap’.[88]

DJ Kool Herc and Coke La Rock provided an influence on the vocal style of rapping by delivering simple poetry verses over funk music breaks, after party-goers showed little interest in their previous attempts to integrate reggae-infused toasting into musical sets.[44][89] DJs and MCs would often add call and response chants, often consisting of a basic chorus, to allow the performer to gather his thoughts (e.g. «one, two, three, y’all, to the beat»). Later, the MCs grew more varied in their vocal and rhythmic delivery, incorporating brief rhymes, often with a sexual or scatological theme, in an effort to differentiate themselves and to entertain the audience. These early raps incorporated the dozens, a product of African American culture. Kool Herc & the Herculoids were the first hip hop group to gain recognition in New York,[89] but the number of MC teams increased over time.

Often these were collaborations between former gangs, such as Afrikaa Bambaataa’s Universal Zulu Nation—now an international organization. Melle Mel, a rapper with the Furious Five is often credited with being the first rap lyricist to call himself an «MC».[90] During the early 1970s B-boying arose during block parties, as b-boys and b-girls got in front of the audience to dance in a distinctive and frenetic style. The style was documented for release to a worldwide audience for the first time in documentaries and movies such as Style Wars, Wild Style, and Beat Street. The term «B-boy» was coined by DJ Kool Herc to describe the people who would wait for the break section of the song, showing off athleticism, spinning on the stage to ‘break-dance’ in the distinctive, frenetic style.[91]

Although there were some early MCs that recorded solo projects of note, such as DJ Hollywood, Kurtis Blow, and Spoonie Gee, the frequency of solo artists did not increase until later with the rise of soloists with stage presence and drama, such as LL Cool J. Most early hip hop was dominated by groups where collaboration between the members was integral to the show.[92] An example would be the early hip hop group Funky Four Plus One, who performed in such a manner on Saturday Night Live in 1981.[93]

1979–1983: Old school hip hop

Transition to recording

The earliest hip hop music was performed live, at house parties and block party events, and it was not recorded. Prior to 1979, recorded hip hop music consisted mainly of PA system soundboard recordings of live party shows and early hip hop mixtapes by DJs. Puerto Rican DJ Disco Wiz is credited as the first hip hop DJ to create a «mixed plate,» or mixed dub recording, when, in 1977, he combined sound bites, special effects and paused beats to technically produce a sound recording.[94] The first hip hop record is widely regarded to be the Sugarhill Gang’s «Rapper’s Delight», from 1979. It was the first hip hop record to gain widespread popularity in the mainstream and was where hip hop music got its name from (from the opening bar).[95] However, much controversy surrounds this assertion as some regard the March 1979 single «King Tim III (Personality Jock)» by the Fatback Band, as a rap record.[96] There are various other claimants for the title of first hip hop record.

By the early 1980s, all the major elements and techniques of the hip hop genre were in place, and by 1982, the electronic (electro) sound had become the trend on the street and in dance clubs. New York City radio station WKTU featured Warp 9’s «Nunk,» in a commercial to promote the station’s signature sound of emerging hip hop[97] Though not yet mainstream, hip hop had begun to permeate the music scene outside of New York City; it could be found in cities as diverse as Los Angeles, Atlanta, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Dallas, Kansas City, San Antonio, Miami, Seattle, St. Louis, New Orleans, Houston, and Toronto. Indeed, «Funk You Up» (1979), the first hip hop record released by a female group, and the second single released by Sugar Hill Records, was performed by the Sequence, a group from Columbia, South Carolina which featured Angie Stone.[98] Despite the genre’s growing popularity, Philadelphia was, for many years, the only city whose contributions could be compared to New York City’s. Hip hop music became popular in Philadelphia in the late 1970s. The first released record was titled «Rhythm Talk», by Jocko Henderson.

The New York Times had dubbed Philadelphia the «Graffiti Capital of the World» in 1971. Philadelphia native DJ Lady B recorded «To the Beat Y’All» in 1979, and became the first female solo hip hop artist to record music.[99] Schoolly D, starting in 1984 and also from Philadelphia, began creating a style that would later be known as gangsta rap.

Influence of disco

Hip hop music was influenced by disco music, as disco also emphasized the key role of the DJ in creating tracks and mixes for dancers, and old school hip hop often used disco tracks as beats. At the same time however, hip hop music was also a backlash against certain subgenres of late 1970s disco. While the early disco was African American and Italian-American-created underground music developed by DJs and producers for the dance club subculture, by the late 1970s, disco airwaves were dominated by mainstream, expensively recorded music industry-produced disco songs. According to Kurtis Blow, the early days of hip hop were characterized by divisions between fans and detractors of disco music. Hip hop had largely emerged as «a direct response to the watered down, Europeanised, disco music that permeated the airwaves».[100][101] The earliest hip hop was mainly based on hard funk loops sourced from vintage funk records. By 1979, disco instrumental loops/tracks had become the basis of much hip hop music. This genre was called «disco rap». Ironically, the rise of hip hop music also played a role in the eventual decline in disco’s popularity.

The disco sound had a strong influence on early hip hop music. Most of the early rap/hip-hop songs were created by isolating existing disco bass-guitar bass lines and dubbing over them with MC rhymes. the Sugarhill Gang used Chic’s «Good Times» as the foundation for their 1979 hit «Rapper’s Delight», generally considered to be the song that first popularized rap music in the United States and around the world. In 1982, Afrika Bambaataa released the single «Planet Rock», which incorporated electronica elements from Kraftwerk’s «Trans-Europe Express» and «Numbers» as well as YMO’s «Riot in Lagos». The Planet Rock sound also spawned a hip-hop electronic dance trend, electro music, which included songs such as Planet Patrol’s «Play at Your Own Risk» (1982), C Bank’s «One More Shot» (1982), Cerrone’s «Club Underworld» (1984), Shannon’s «Let the Music Play» (1983), Freeez’s «I.O.U.» (1983), Midnight Star’s «Freak-a-Zoid» (1983), Chaka Khan’s «I Feel For You» (1984).

DJ Pete Jones, Eddie Cheeba, DJ Hollywood, and Love Bug Starski were disco-influenced hip hop DJs. Their styles differed from other hip hop musicians who focused on rapid-fire rhymes and more complex rhythmic schemes. Afrika Bambaataa, Paul Winley, Grandmaster Flash, and Bobby Robinson were all members of third s latter group. In Washington, D.C. go-go emerged as a reaction against disco and eventually incorporated characteristics of hip hop during the early 1980s. The DJ-based genre of electronic music behaved similarly, eventually evolving into underground styles known as house music in Chicago and techno in Detroit.

Diversification of styles

The 1980s marked the diversification of hip hop as the genre developed more complex styles.[102] New York City became a veritable laboratory for the creation of new hip hop sounds. Early examples of the diversification process can be heard in tracks such as Grandmaster Flash’s «The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel» (1981), a single consisting entirely of sampled tracks[103] as well as Afrika Bambaataa’s «Planet Rock» (1982), and Warp 9’s «Nunk,» (1982)[104] which signified the fusion of hip hop music with electro. In addition, Rammellzee & K-Rob’s «Beat Bop» (1983) was a ‘slow jam’ which had a dub influence with its use of reverb and echo as texture and playful sound effects. «Light Years Away,» by Warp 9 (1983), (produced and written by Lotti Golden and Richard Scher) described as a «cornerstone of early 80s beatbox afrofuturism,» by the UK paper, The Guardian,[76] introduced social commentary from a sci-fi perspective. In the 1970s, hip hop music typically used samples from funk and later, from disco. The mid-1980s marked a paradigm shift in the development of hip hop, with the introduction of samples from rock music, as demonstrated in the albums King of Rock and Licensed to Ill. Hip hop prior to this shift is characterized as old school hip hop.

The Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer, a staple sound of hip hop

In 1980, the Roland Corporation launched the TR-808 Rhythm Composer. It was one of the earliest programmable drum machines, with which users could create their own rhythms rather than having to use preset patterns. Though it was a commercial failure, over the course of the decade the 808 attracted a cult following among underground musicians for its affordability on the used market,[105] ease of use,[106] and idiosyncratic sounds, particularly its deep, «booming» bass drum.[107] It became a cornerstone of the emerging electronic, dance, and hip hop genres, popularized by early hits such as Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force’s «Planet Rock».[108] The 808 was eventually used on more hit records than any other drum machine;[109] its popularity with hip hop in particular has made it one of the most influential inventions in popular music, comparable to the Fender Stratocaster’s influence on rock.[110][111]

Over time sampling technology became more advanced. However, earlier producers such as Marley Marl used drum machines to construct their beats from small excerpts of other beats in synchronisation, in his case, triggering three Korg sampling-delay units through a Roland 808. Later, samplers such as the E-mu SP-1200 allowed not only more memory but more flexibility for creative production. This allowed the filtration and layering different hits, and with a possibility of re-sequencing them into a single piece. With the emergence of a new generation of samplers such as the AKAI S900 in the late 1980s, producers did not have to create complex, time-consuming tape loops. Public Enemy’s first album was created with the help of large tape loops. The process of looping a break into a breakbeat now became more commonly done with a sampler, now doing the job which so far had been done manually by the DJs using turntables. In 1989, DJ Mark James, under the moniker «45 King», released «The 900 Number», a breakbeat track created by synchronizing samplers and vinyl records.[92]

The lyrical content and other instrumental accompaniment of hip hop developed as well. The early lyrical styles in the 1970, which tended to be boasts and clichéd chants, were replaced with metaphorical lyrics exploring a wider range of subjects. As well, the lyrics were performed over more complex, multi-layered instrumental accompaniment. Artists such as Melle Mel, Rakim, Chuck D, KRS-One and Warp 9 revolutionized hip hop by transforming it into a more mature art form, with sophisticated arrangements, often featuring «gorgeous textures and multiple layers»[112] The influential single «The Message» (1982) by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five is widely considered to be the pioneering force for conscious rap.

Independent record labels like Tommy Boy, Prism Records and Profile Records became successful in the early 1980s, releasing records at a furious pace in response to the demand generated by local radio stations and club DJs. Early 1980s electro music and rap were catalysts that sparked the hip hop movement, led by artists such as Cybotron, Hashim, Afrika Bambaataa, Planet Patrol, Newcleus and Warp 9. In the New York City recording scene, artists collaborated with producer/writers such as Arthur Baker, John Robie, Lotti Golden and Richard Scher, exchanging ideas that contributed to the development of hip hop.[113] Some rappers eventually became mainstream pop performers. Kurtis Blow’s appearance in a Sprite soda pop commercial[114] marked the first hip hop musician to do a commercial for a major product. The 1981 songs «Rapture» by Blondie and «Christmas Wrapping» by the new wave band the Waitresses were among the first pop songs to use rap. In 1982, Afrika Bambaataa introduced hip hop to an international audience with «Planet Rock.»

Prior to the 1980s, hip hop music was largely confined within the context of the United States. However, during the 1980s, it began its spread and became a part of the music scene in dozens of countries. Greg Wilson was the first DJ to introduce electro hip hop to UK club audiences in the early 1980s, opting for the dub or instrumental versions of Nunk by Warp 9, Extra T’s «ET Boogie,» Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) by Man Parrish, Planet Rock and Dirty Talk.[115]

In the early part of the decade, B-boying became the first aspect of hip hop culture to reach Japan, Australia and South Africa. In South Africa, the breakdance crew Black Noise established the practice before beginning to rap later in the decade. Musician and presenter Sidney became France’s first black TV presenter with his show H.I.P. H.O.P.[116] which screened on TF1 during 1984, a first for the genre worldwide. Sidney is considered the father of French hip hop. Radio Nova helped launch other French hip hop stars including Dee Nasty, whose 1984 album Paname City Rappin’ along with compilations Rapattitude 1 and 2 contributed to a general awareness of hip hop in France.

Hip hop has always kept a very close relationship with the Latino community in New York. DJ Disco Wiz and the Rock Steady Crew were among early innovators from Puerto Rico, combining English and Spanish in their lyrics. the Mean Machine recorded their first song under the label «Disco Dreams» in 1981, while Kid Frost from Los Angeles began his career in 1982. Cypress Hill was formed in 1988 in the suburb of South Gate outside Los Angeles when Senen Reyes (born in Havana) and his younger brother Ulpiano Sergio (Mellow Man Ace) moved from Cuba to South Gate with his family in 1971. They teamed up with DVX from Queens (New York), Lawrence Muggerud (DJ Muggs) and Louis Freese (B-Real), a Mexican/Cuban-American native of Los Angeles. After the departure of «Ace» to begin his solo career, the group adopted the name of Cypress Hill named after a street running through a neighborhood nearby in South Los Angeles.

Japanese hip hop is said to have begun when Hiroshi Fujiwara returned to Japan and started playing hip hop records in the early 1980s.[117] Japanese hip hop generally tends to be most directly influenced by old school hip hop, taking the era’s catchy beats, dance culture, and overall fun and carefree nature and incorporating it into their music. Hip hop became one of the most commercially viable mainstream music genres in Japan, and the line between it and pop music is frequently blurred.

1983–1986: New school hip hop

The new school of hip hop was the second wave of hip hop music, originating in 1983–84 with the early records of Run-D.M.C. and LL Cool J. As with the hip hop preceding it (which subsequently became known as old school hip hop), the new school came predominantly from New York City. The new school was initially characterized in form by drum machine-led minimalism, with influences from rock music, a hip hop «metal music for the 80s–a hard-edge ugly/beauty trance as desperate and stimulating as New York itself.»[118] It was notable for taunts and boasts about rapping, and socio-political commentary, both delivered in an aggressive, self-assertive style. In image as in song its artists projected a tough, cool, street b-boy attitude.

These elements contrasted sharply with much of the previous funk- and disco-influenced hip hop groups, whose music was often characterized by novelty hits, live bands, synthesizers, and «party rhymes» (not all artists prior to 1983–84 had these styles). New school artists made shorter songs that could more easily gain radio play, and they produced more cohesive LP albums than their old school counterparts. By 1986, their releases began to establish the hip-hop album as a fixture of mainstream music. Hip hop music became commercially successful, as exemplified by the Beastie Boys’ 1986 album Licensed to Ill, which was the first rap album to hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts.[119]

1986–1997: Golden age hip hop

Hip hop’s «golden age» (or «golden era») is a name given to a period in mainstream hip hop, produced between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s,[120][121][122] which is characterized by its diversity, quality, innovation and influence.[123][124] There were strong themes of Afrocentrism and political militancy in golden age hip hop lyrics. The music was experimental and the sampling drew on eclectic sources.[125] There was often a strong jazz influence in the music. The artists and groups most often associated with this phase are Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions, Eric B. & Rakim, De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Gang Starr, Big Daddy Kane and the Jungle Brothers.[126]

The golden age is noted for its innovation – a time «when it seemed that every new single reinvented the genre»[127] according to Rolling Stone. Referring to «hip-hop in its golden age»,[128] Spin‘s editor-in-chief Sia Michel says, «there were so many important, groundbreaking albums coming out right about that time»,[128]

and MTV’s Sway Calloway adds: «The thing that made that era so great is that nothing was contrived. Everything was still being discovered and everything was still innovative and new».[129] Writer William Jelani Cobb says «what made the era they inaugurated worthy of the term golden was the sheer number of stylistic innovations that came into existence… in these golden years, a critical mass of mic prodigies were literally creating themselves and their art form at the same time».[130]

The golden age spans «from approximately 1986 to 1997», according to Carl Stoffers of New York Daily News.[120] In their article «In Search of the Golden Age Hip-Hop Sound», music theorists Ben Duinker and Denis Martin of Empirical Musicology Review use «the 11 years between and including 1986 and 1996 as chronological boundaries» to define the golden age, beginning with the releases of Run-DMC’s Raising Hell and the Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill, and ending with the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G.[122] The Boombox writer Todd «Stereo» Williams also cites the May 1986 release of Raising Hell (which sold more than three million copies) as the start of the period and notes that over the next year other important albums were released to success, including Licensed to Ill, Boogie Down Productions’ Criminal Minded (1987), Public Enemy’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show (1987), and Eric B. & Rakim’s Paid in Full (1987). Williams views this development as the beginning of hip hop’s own «album era» from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, during which hip hop albums earned an unprecedented critical recognition and «would be the measuring stick by which most of the genre’s greats would be judged».[131]

Gangsta rap and West Coast hip hop

Many black rappers—including Ice-T and Sister Souljah—contend that they are being unfairly singled out because their music reflects deep changes in society not being addressed anywhere else in the public forum. The white politicians, the artists complain, neither understand the music nor desire to hear what’s going on in the devastated communities that gave birth to the art form.

— Chuck Philips, Los Angeles Times, 1992[132]

Gangsta rap is a subgenre of hip hop that reflects the violent lifestyles of inner-city American black youths.[133] Gangsta is a non-rhotic pronunciation of the word gangster. The genre was pioneered in the mid-1980s by rappers such as Schoolly D and Ice-T, and was popularized in the later part of the 1980s by groups like N.W.A. In 1985 Schoolly D released «P.S.K. What Does It Mean?», which is often regarded as the first gangsta rap song, which was followed by Ice-T’s «6 in the Mornin'» in 1986. After the national attention and controversy that Ice-T and N.W.A created in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as well as the mainstreaming of G-funk in the mid-1990s, gangsta rap became the most commercially-lucrative subgenre of hip hop. Some gangsta rappers were known for mixing the political and social commentary of political rap with the criminal elements and crime stories found in gangsta rap.[134]

N.W.A is the group most frequently associated with the founding of gangsta rap. Their lyrics were more violent, openly confrontational, and shocking than those of established rap acts, featuring incessant profanity and, controversially, use of the word «nigga». These lyrics were placed over rough, rock guitar-driven beats, contributing to the music’s hard-edged feel. The first blockbuster gangsta rap album was N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton, released in 1988. Straight Outta Compton would establish West Coast hip hop as a vital genre, and establish Los Angeles as a legitimate rival to hip hop’s long-time capital, New York City. Straight Outta Compton sparked the first major controversy regarding hip hop lyrics when their song «Fuck tha Police» earned a letter from FBI Assistant Director, Milt Ahlerich, strongly expressing law enforcement’s resentment of the song.[135][136]

Controversy surrounded Ice-T’s album Body Count, in particular over its song «Cop Killer». The song was intended to speak from the viewpoint of a criminal getting revenge on racist, brutal cops. Ice-T’s rock song infuriated government officials, the National Rifle Association of America and various police advocacy groups.[137][138] Consequently, Time Warner Music refused to release Ice-T’s upcoming album Home Invasion because of the controversy surrounding «Cop Killer».[139] Ice-T suggested that the furor over the song was an overreaction, telling journalist Chuck Philips «…they’ve done movies about nurse killers and teacher killers and student killers. [Actor] Arnold Schwarzenegger blew away dozens of cops as the Terminator. But I don’t hear anybody complaining about that.» In the same interview, Ice-T suggested to Philips that the misunderstanding of Cop Killer and the attempts to censor it had racial overtones: «The Supreme Court says it’s OK for a white man to burn a cross in public. But nobody wants a black man to write a record about a cop killer.»[137]

The subject matter inherent in gangsta rap more generally has caused controversy. The White House administrations of both George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton criticized the genre.[132] «The reason why rap is under attack is because it exposes all the contradictions of American culture …What started out as an underground art form has become a vehicle to expose a lot of critical issues that are not usually discussed in American politics. The problem here is that the White House and wanna-bes like Bill Clinton represent a political system that never intends to deal with inner city urban chaos,» Sister Souljah told The Times.[132] Due to the influence of Ice-T and N.W.A, gangsta rap is often viewed as a primarily West Coast phenomenon, despite the contributions of East Coast acts like Schoolly D and Boogie Down Productions in shaping the genre.

Mainstream breakthrough

In 1990, Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet was a significant success with music critics and consumers.[140] The album played a key role in hip hop’s mainstream emergence in 1990, dubbed by Billboard editor Paul Grein as «the year that rap exploded».[140] In a 1990 article on its commercial breakthrough, Janice C. Thompson of Time wrote that hip hop «has grown into the most exciting development in American pop music in more than a decade.»[141] Thompson noted the impact of Public Enemy’s 1989 single «Fight the Power», rapper Tone Lōc’s single Wild Thing being the best-selling single of 1989, and that at the time of her article, nearly a third of the songs on the Billboard Hot 100 were hip hop songs.[141] In a similar 1990 article, Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times put hip hop music’s commercial emergence into perspective:

It was 10 years ago that the Sugarhill Gang’s «Rapper’s Delight» became the first rap single to enter the national Top 20. Who ever figured then that the music would even be around in 1990, much less produce attractions that would command as much pop attention as Public Enemy and N.W.A? «Rapper’s Delight» was a novelty record that was considered by much of the pop community simply as a lightweight offshoot of disco—and that image stuck for years. Occasional records—including Grandmaster Flash’s «The Message» in 1982 and Run-DMC’s «It’s Like That» in 1984—won critical approval, but rap, mostly, was dismissed as a passing fancy—too repetitious, too one dimensional. Yet rap didn’t go away, and an explosion of energy and imagination in the late 1980s leaves rap today as arguably the most vital new street-oriented sound in pop since the birth of rock in the 1950s.[142]

Rap is the rock ‘n’ roll of the day. Rock ‘n’ roll was about attitude, rebellion, a big beat, sex and, sometimes, social comment. If that’s what you’re looking for now, you’re going to find it here.

— Bill Adler, Time, 1990[141]

MC Hammer hit mainstream success with the multi platinum album Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ‘Em. The record reached No. 1 and the first single, «U Can’t Touch This» charted on the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100. MC Hammer became one of the most successful rappers of the early nineties and one of the first household names in the genre. The album raised rap music to a new level of popularity. It was the first hip-hop album certified diamond by the RIAA for sales of over ten million.[143] It remains one of the genre’s all-time best-selling albums.[144] To date, the album has sold as many as 18 million units.[145][146][147][148] Released in 1990, «Ice Ice Baby» by Vanilla Ice was the first hip hop single to top the Billboard charts in the U.S. It also reached number one in the UK, Australia among others and has been credited for helping diversify hip hop by introducing it to a mainstream audience.[149] In 1992, Dr. Dre released The Chronic. As well as helping to establish West Coast gangsta rap as more commercially viable than East Coast hip hop,[150] this album founded a style called G Funk, which soon came to dominate West Coast hip hop. The style was further developed and popularized by Snoop Dogg’s 1993 album Doggystyle. However, hip hop was still met with resistance from black radio, including urban contemporary radio stations. Russell Simmons said in 1990, «Black radio [stations] hated rap from the start and there’s still a lot of resistance to it».[142]

Despite the lack of support from some black radio stations, hip hop became a best-selling music genre in the mid-1990s and the top selling music genre by 1999 with 81 million CDs sold.[151][152][153] By the late 1990s hip hop was artistically dominated by the Wu-Tang Clan, Diddy and the Fugees.[150] The Beastie Boys continued their success throughout the decade crossing color lines and gaining respect from many different artists. Record labels based out of Atlanta, St. Louis, and New Orleans also gained fame for their local scenes. The midwest rap scene was known for fast vocal styles from artists such as Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, Tech N9ne, and Twista. By the end of the decade, hip hop was an integral part of popular music, and many American pop songs had hip hop components.

Hip hop has been described as a «mainstream subculture». The main reasons why hip hop culture secured its subcultural authority despite becoming a part of the mass media and mainstream industries can be summarized as follows. First, hip hop artists promoted symbolic and conspicuous consumption in their music from a very early stage. Second, the continuing display of resistance in hip-hop has continuously attracted new generations of rebellious fans. Third, owing to the subcultural ideal of rising from the underground, the hip hop scene has remained committed to its urban roots. Fourth, the concept of battle rap has prevented hip-hop music from excessive cultural dilution. Finally, the solidarity within the African American community has shielded the subculture from erosion through mainstream commercialization.[154]

East vs. West rivalry

The East Coast–West Coast hip hop rivalry was a feud from 1991 to 1997 between artists and fans of the East Coast hip hop and West Coast hip hop scenes in the United States, especially from 1994 to 1997. Focal points of the feud were East Coast-based rapper the Notorious B.I.G. (and his New York-based label, Bad Boy Records) and West Coast-based rapper Tupac Shakur (and his Los Angeles-based label, Death Row Records). This rivalry started before the rappers themselves hit the scene. Because New York is the birthplace of hip-hop, artists from the West Coast felt as if they were not receiving the same media coverage and public attention as the East Coast.[155] As time went on both rappers began to grow in fame and as they both became more known the tensions continued to arise. Eventually both artists were fatally shot following drive-by shootings by unknown assailants in 1997 and 1996, respectively.

East Coast hip hop

In the early 1990s East Coast hip hop was dominated by the Native Tongues posse, which was loosely composed of De La Soul with producer Prince Paul, A Tribe Called Quest, the Jungle Brothers, as well as their loose affiliates 3rd Bass, Main Source, and the less successful Black Sheep and KMD. Although originally a «daisy age» conception stressing the positive aspects of life, darker material (such as De La Soul’s thought-provoking «Millie Pulled a Pistol on Santa») soon crept in. Artists such as Masta Ace (particularly for SlaughtaHouse), Brand Nubian, Public Enemy, Organized Konfusion, and Tragedy Khadafi had a more overtly-militant pose, both in sound and manner. In 1993, the Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) revitalized the New York hip hop scene by pioneering an East Coast hardcore rap equivalent in intensity to what was being produced on the West Coast.[156] According to Allmusic, the production on two Mobb Deep albums, The Infamous (1995) and Hell on Earth (1996), are «indebted» to RZA’s early production with the Wu-Tang Clan.[157][158]

The success of albums such as Nas’s Illmatic and Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die in 1994 cemented the status of the East Coast during a time of West Coast dominance. In a March 2002 issue of The Source Magazine, Nas referred to 1994 as «a renaissance of New York [City] Hip-Hop.»[159] The productions of RZA, particularly for the Wu-Tang Clan, became influential with artists such as Mobb Deep due to the combination of somewhat detached instrumental loops, highly compressed and processed drums, and gangsta lyrical content. Wu-Tang solo albums such as Raekwon the Chef’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx, Ghostface Killah’s Ironman, and GZA’s Liquid Swords are now viewed as classics along with Wu-Tang «core» material. The clan’s base extended into further groups called «Wu-affiliates». Producers such as DJ Premier (primarily for Gang Starr but also for other affiliated artists, such as Jeru the Damaja), Pete Rock (with CL Smooth, and supplying beats for many others), Buckwild, Large Professor, Diamond D, and Q-Tip supplied beats for numerous MCs at the time, regardless of location. Albums such as Nas’s Illmatic, O.C.’s Word…Life (1994), and Jay-Z’s Reasonable Doubt (1996) are made up of beats from this pool of producers.

The rivalry between the East Coast and the West Coast rappers eventually turned personal.[160] Later in the decade the business acumen of the Bad Boy Records tested itself against Jay-Z and his Roc-A-Fella Records and, on the West Coast, Death Row Records. The mid to late 1990s saw a generation of rappers such as the members of D.I.T.C. such as the late Big L and Big Pun. On the East Coast, although the «big business» end of the market dominated matters commercially the late 1990s to early 2000s saw a number of relatively successful East Coast indie labels such as Rawkus Records (with whom Mos Def and Talib Kweli garnered success) and later Def Jux. The history of the two labels is intertwined, the latter having been started by EL-P of Company Flow in reaction to the former, and offered an outlet for more underground artists such as Mike Ladd, Aesop Rock, Mr Lif, RJD2, Cage and Cannibal Ox. Other acts such as the Hispanic Arsonists and slam poet turned MC Saul Williams met with differing degrees of success.

West Coast hip hop

After N.W.A. broke up, former member Dr. Dre released The Chronic in 1992, which peaked at No. 1 on the R&B/hip hop chart,[161] No. 3 on the pop chart, and spawned a No. 2 pop single with «Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang». The Chronic took West Coast rap in a new direction,[162] influenced strongly by P funk artists, melding smooth and easy funk beats with slowly-drawled lyrics. This came to be known as G-funk and dominated mainstream hip hop in the early-mid 1990s through a roster of artists on Suge Knight’s Death Row Records, including Tupac Shakur, whose double disc album All Eyez on Me was a big hit with hit songs «Ambitionz az a Ridah» and «2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted»;[citation needed] and Snoop Doggy Dogg, whose Doggystyle included the top ten hits «What’s My Name?» and «Gin and Juice».[163] As the Los Angeles-based Death Row built an empire around Dre, Snoop, and Tupac, it also entered into a rivalry with New York City’s Bad Boy Records, led by Puff Daddy and the Notorious B.I.G.

Detached from this scene were other artists such as Freestyle Fellowship and the Pharcyde, as well as more underground artists such as the Solesides collective (DJ Shadow and Blackalicious amongst others), Jurassic 5, Ugly Duckling, People Under the Stairs, Tha Alkaholiks, and earlier Souls of Mischief, who represented a return to hip hop’s roots of sampling and well-planned rhyme schemes.

Further diversification

In the 1990s, hip hop began to diversify with other regional styles emerging on the national scene. Southern rap became popular in the early 1990s.[164] The first Southern rappers to gain national attention were the Geto Boys out of Houston, Texas.[165] Southern rap’s roots can be traced to the success of Geto Boy’s Grip It! On That Other Level in 1989, the Rick Rubin produced The Geto Boys in 1990, and We Can’t Be Stopped in 1991.[166] The Houston area also produced other artists that pioneered the early southern rap sound such as UGK and the solo career of Scarface.

Atlanta hip hop artists were key in further expanding rap music and bringing southern hip hop into the mainstream. Releases such as Arrested Development’s 3 Years, 5 Months and 2 Days in the Life Of… in 1992, Goodie Mob’s Soul Food in 1995 and OutKast’s ATLiens in 1996 were all critically acclaimed. Other distinctive regional sounds from St. Louis, Chicago, Washington D.C., Detroit and others began to gain popularity.

What once was rap now is hip hop, an endlessly various mass phenomenon that continues to polarize older rock and rollers, although it’s finally convinced some gatekeeping generalists that it may be of enduring artistic value—a discovery to which they were beaten by millions of young consumers black and white.

— Christgau’s Consumer Guide: Albums of the ’90s (2000)[167]

During the golden age, elements of hip hop continued to be assimilated into other genres of popular music. The first waves of rap rock, rapcore, and rap metal — respective fusions of hip hop and rock, hardcore punk, and heavy metal[168] — became popular among mainstream audiences at this time; Run-DMC, the Beastie Boys, and Rage Against the Machine were among the most well-known bands in these fields. In Hawaii, bands such as Sudden Rush combined hip hop elements with the local language and political issues to form a style called na mele paleoleo.[169]

Digable Planets’ 1993 release Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space) was an influential jazz rap record sampling the likes of Don Cherry, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey, Herbie Mann, Herbie Hancock, Grant Green, and Rahsaan Roland Kirk. It spawned the hit single «Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)» which reached No. 16 on the Billboard Hot 100.[170]

1997–2006: Bling era

Commercialization and new directions

During the late 1990s, in the wake of the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G., a new commercial sound emerged in the hip hop scene, sometimes referred to as the «bling era»[171] (derived from Lil Wayne’s «Bling Bling»),[172] «jiggy era»[173][174] (derived from Will Smith’s «Gettin’ Jiggy wit It»), or «shiny suit era» (derived by metallic suits worn by some rappers in music videos at the time, such as in «Mo Money Mo Problems» by the Notorious B.I.G., Puff Daddy, and Mase).[175] Before the late 1990s, gangsta rap, while a huge-selling genre, had been regarded as well outside of the pop mainstream, committed to representing the experience of the inner-city and not «selling out» to the pop charts. However, the rise of Sean «Puff Daddy» Combs’s Bad Boy Records, propelled by the massive crossover success of Combs’s 1997 ensemble album No Way Out, signaled a major stylistic change in gangsta rap (and mainstream hip hop in general), as it would become even more commercially successful and popularly accepted. Silky R&B-styled hooks and production, more materialist subject matter, and samples of hit soul and pop songs from the 1970s and 1980s were the staples of this sound, which was showcased by producers such as Combs, Timbaland, the Trackmasters, the Neptunes, and Scott Storch. Also achieving similar levels of success at this time were Master P and his No Limit label in New Orleans; Master P built up a roster of artists (the No Limit posse) based out of New Orleans, and incorporated G funk and Miami bass influences in his music. The New Orleans upstart Cash Money label was also gaining popularity during this time,[176] with emerging artists such as Birdman, Lil Wayne, B.G, and Juvenile.

Many of the rappers who achieved mainstream success at this time, such as Nelly, Puff Daddy, Jay-Z, the later career of Fat Joe and his Terror Squad, Mase, Ja Rule, Fabolous, and Cam’ron, had a pop-oriented style, while others such as Big Pun, Fat Joe (in his earlier career), DMX, Eminem, 50 Cent and his G-Unit, and the Game enjoyed commercial success at this time with a grittier style. Although white rappers like the Beastie Boys, House of Pain, and 3rd Bass previously had some popular success or critical acceptance from the hip hop community, Eminem’s success, beginning in 1999 with the platinum The Slim Shady LP,[177] surprised many. Hip hop influences also found their way increasingly into mainstream pop during this period, particularly in genres such as R&B (e.g. R. Kelly, Akon, TLC, Destiny’s Child, Beyonce, Ashanti, Aaliyah, Usher), neo soul (e.g. Lauryn Hill, Erykah Badu, Jill Scott), and nu metal (e.g. Korn, Limp Bizkit).

Dr. Dre remained an important figure in this era, making his comeback in 1999 with the album 2001. In 2000, he produced The Marshall Mathers LP by Eminem, and also produced 50 Cent’s 2003 album Get Rich or Die Tryin’, which debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 charts.[178] Jay-Z represented the cultural triumph of hip hop in this era. As his career progressed, he went from performing artist to entrepreneur, label president, head of a clothing line, club owner, and market consultant—along the way breaking Elvis Presley’s record for most number one albums on the Billboard magazine charts by a solo artist.

Rise of alternative hip hop

Alternative hip hop, which was introduced in the 1980s and then declined, resurged in the early-mid 2000s with the rejuvenated interest in indie music by the general public. The genre began to attain a place in the mainstream, due in part to the crossover success of artists such as OutKast, Kanye West, and Gnarls Barkley.[179] OutKast’s 2003 album Speakerboxxx/The Love Below received high acclaim from music critics, and appealed to a wide range of listeners, being that it spanned numerous musical genres – including rap, rock, R&B, punk, jazz, indie, country, pop, electronica, and gospel. The album also spawned two number-one hit singles, and has been certified diamond by selling 11 times platinum by the RIAA for shipping more than 11 million units,[180] becoming one of the best selling hip-hop albums of all time. It also won a Grammy Award for Album of the Year at the 46th Annual Grammy Awards, being only the second rap album to do so. Previously, alternative hip hop acts had attained much critical acclaim, but received relatively little exposure through radio and other media outlets; during this time, alternative hip hop artists such as MF Doom,[181] the Roots, Dilated Peoples, Gnarls Barkley, Mos Def, and Aesop Rock[182][183] began to achieve significant recognition.

Glitch hop and wonky music

Glitch hop and wonky music evolved following the rise of trip hop, dubstep and intelligent dance music (IDM). Both glitch hop and wonky music frequently reflect the experimental nature of IDM and the heavy bass featured in dubstep songs. While trip hop has been described as being a distinct British upper-middle class take on hip-hop, glitch-hop and wonky music have much more stylistic diversity. Both genres are melting pots of influence. Glitch hop contains echoes of 1980s pop music, Indian ragas, eclectic jazz and West Coast rap. Los Angeles, London, Glasgow and a number of other cities have become hot spots for these scenes, and underground scenes have developed across the world in smaller communities. Both genres often pay homage to older and more well established electronic music artists such as Radiohead, Aphex Twin and Boards of Canada as well as independent hip hop producers like J Dilla and Madlib.

Glitch hop is a fusion genre of hip hop and glitch music that originated in the early to mid-2000s in the United States and Europe. Musically, it is based on irregular, chaotic breakbeats, glitchy basslines and other typical sound effects used in glitch music, like skips. Glitch hop artists include Prefuse 73, Dabrye and Flying Lotus.[184] Wonky is a subgenre of hip hop that originated around 2008, but most notably in the United States and United Kingdom, and among international artists of the Hyperdub music label, under the influence of glitch hop and dubstep. Wonky music is of the same glitchy style as glitch hop, but it was specifically noted for its melodies, rich with «mid-range unstable synths». Scotland has become one of the most prominent wonky scenes, with artists like Hudson Mohawke and Rustie.

Glitch hop and wonky are popular among a relatively smaller audience interested in alternative hip hop and electronic music (especially dubstep); neither glitch hop nor wonky have achieved mainstream popularity. However, artists like Flying Lotus, the Glitch Mob and Hudson Mohawke have seen success in other avenues. Flying Lotus’s music has earned multiple positive reviews on the independent music review site Pitchfork.com as well as a prominent (yet uncredited) spot during Adult Swim commercial breaks.[185][186] Hudson Mohawke is one of few glitch hop artists to play at major music festivals such as Sasquatch! Music Festival.

Crunk music

Producer Lil Jon is one of crunk’s most prominent figures.

Crunk is a regional hip hop genre that originated in Tennessee in the southern United States in the 1990s, influenced by Miami bass.[187] One of the pioneers of crunk, Lil Jon, said that it was a fusion of hip hop, electro, and electronic dance music. The style was pioneered and commercialized by artists from Memphis, Tennessee and Atlanta, Georgia, gaining considerable popularity in the mid-2000s via Lil Jon and the Ying Yang Twins.[188] Looped, stripped-down drum machine rhythms are usually used. The Roland TR-808 and 909 are among the most popular. The drum machine loops are usually accompanied by simple, repeated synthesizer melodies and heavy bass «stabs». The tempo of the music is somewhat slower than hip-hop, around the speed of reggaeton. The focal point of crunk is more often the beats and instrumental music rather than the lyrics. Crunk rappers, however, often shout and scream their lyrics, creating an aggressive, almost heavy, style of hip-hop. While other subgenres of hip-hop address sociopolitical or personal concerns, crunk is almost exclusively «party music», favoring call and response hip-hop slogans in lieu of more substantive approaches.[189] Crunk helped southern hip hop gain mainstream prominence during this period, as the classic East and West Coast styles of the 1990s gradually lost dominance.[190]

2006–2014: Blog era

Snap music and influence of the Internet

Snap rap (also known as ringtone rap) is a subgenre of crunk that emerged from Atlanta, Georgia in the late 1990s.[191] The genre gained mainstream popularity in the mid-late 2000s, and artists from other Southern states such as Tennessee also began to emerge performing in this style. Tracks commonly consist of a Roland TR-808 bass drum, hi-hat, bass, finger snapping, a main groove, and a simplistic vocal hook. Hit snap songs include «Lean wit It, Rock wit It» by Dem Franchize Boyz, «Laffy Taffy» by D4L, «It’s Goin’ Down» by Yung Joc, and «Crank That (Soulja Boy)» by Soulja Boy Tell ‘Em. In retrospect, Soulja Boy has been credited with setting trends in hip hop, such as self-publishing his songs through the Internet (which helped them go viral) and paving the way for a new wave of younger artists.[192][193]

Decline in sales

While hip hop music sales dropped a great deal in the mid-late 2000s, rappers like Flo Rida were successful online and with singles, despite low album sales.