From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A six-word story regarding a pair of baby shoes is considered an extreme example of flash fiction.

«For sale: baby shoes, never worn.» is a six-word story, popularly attributed to Ernest Hemingway, although the link to him is unlikely.[1][2] It is an example of flash fiction.

Setting[edit]

The claim of Hemingway’s authorship originates in an unsubstantiated anecdote about a wager among him and other writers. In a 1991 letter to Canadian humorist John Robert Colombo, science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke recounts: «He’s [Hemingway] supposed to have won a $10 bet (no small sum in the ’20s) from his fellow writers. They paid up without a word. … Here it is. I still can’t think of it without crying— FOR SALE. BABY SHOES. NEVER WORN.»[1]

History[edit]

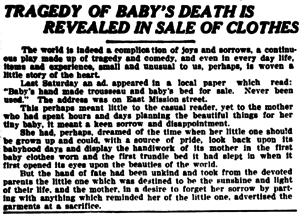

This May 16, 1910 article from The Spokane Press recounts an earlier advertisement that struck the author as particularly tragic.

Versions of the story date back to as early as 1906.[1] The May 16, 1910, edition of The Spokane Press had an article titled «Tragedy of Baby’s Death is Revealed in Sale of Clothes.»[3][1]

In 1917, William R. Kane published a piece in a periodical called The Editor where he outlined the basic idea of a grief-stricken woman who had lost her baby and even suggested the title of Little Shoes, Never Worn.[2] In his version of the story, the shoes are being given away rather than sold. He suggests that this would provide some measure of solace for the owner, as it would mean that another baby would at least benefit directly.[4]

By 1921, the story was already being parodied: the July issue of Judge that year published a version that used a baby carriage instead of shoes; there, however, the narrator described contacting the seller to offer condolences, only to be told that the sale was due to the birth of twins rather than of a single child.[1]

The earliest known connection to Hemingway was in 1991, thirty years after the author’s death.[1] This attribution was in a book by Peter Miller called Get Published! Get Produced!: A Literary Agent’s Tips on How to Sell Your Writing. He said he was told the story by a «well-established newspaper syndicator» in 1974.[5] In 1992, John Robert Colombo printed a letter from Arthur C. Clarke that repeated the story, complete with Hemingway having won $10 each from fellow writers.[1]

This connection to Hemingway was reinforced by a one-man play called Papa by John deGroot, which debuted in 1996. Set during a Life magazine photo session in 1959, deGroot has the character utter the phrase as a means of illustrating Hemingway’s brevity.[1] In Playbill, deGroot defended his portrayal of Hemingway by saying, «Everything in the play is based on events as described by Ernest Hemingway, or those who knew him well. Whether or not these things actually happened is something we’ll never know truly. But Hemingway and many others claimed they did.»[6]

Legacy[edit]

Telling a story in very few words was dubbed flash fiction in 1992. The six-word limit in particular has spawned the concept of Six-Word Memoirs,[7] including a collection published in book form in 2008 by Smith Magazine, and two sequels published in 2009.

See also[edit]

- Iceberg theory

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Garson O’Toole (January 28, 2013). «For Sale, Baby Shoes, Never Worn». quoteinvestigator.com. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ a b Haglund, David (Jan 31, 2013). «Did Hemingway Really Write His Famous Six-Word Story?». Slate. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ «Tragedy of Baby’s Death is Revealed in Sale of Clothes». The Spokane Press. May 16, 1910. p. 6. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Kane, William R. (February 24, 1917). «untitled». The Editor: The Journal of Information for Literary Workers, Volume 45, number 4. pp. 175–176. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Miller, Peter (Mar 1, 1991). Get Published! Get Produced!: A Literary Agent’s Tips on How to Sell Your Writing. SP Books. p. 27. ISBN 9781561710072.

- ^ Mikkelson, David; Mikkelson, Barbara (29 October 2008). «Baby Shoes». Snopes.com. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ «Six-Word Memoirs Can Say It All». CBS News. February 26, 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

Eanest Hemingway wrote a story in six words. It’s famous ultra-short fiction.

For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

UPDATE Feb 2013: Attribution to Hemingway is possibly apocryphal. Analysis still stands though.

In terms of what I wrote in How to Write Twitter Stories this well-read story has all those five stages, but in only six words.

- setting

- disruption

- recognition

- response

- resolution

But then Hemingway is famous for implying what’s going on rather than directly telling the reader why something happened. His genius lies in getting the reader to do a lot of work.

The biggest part of the whole story isn’t even mentioned. You don’t even find out about it until you have actually finished reading. When a reader reflects on what has just been read. At this moment the reader’s pattern recognition habits connect the dots, and it all goes ‘click’.

One could mechanically outline the story like this analysis:

- (setting) We are expecting a baby, so we prepare for a baby. Buy shoes, etc.

- (disruption) We lost a baby.

- (recognition) We grieve.

- (response) We decide to clear up and sell our preparations, and move on.

- (resolution)(return) We place an advert to sell the baby’s shoes.

For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

There is a lot the reader has to fill in from the five-point outline above in those six words. But first, before that, the reader has to first recognise and understand the formal requirements of a classified advert for a classified section of a newspaper, or what might be pinned to a noticeboard somewhere.

‘For sale:’ does all of that. It also sets up an expectation that the advertiser will try and describe the goods for sale to their best advantage. Also, people unused to advertising forms will have trouble seeing any story at all.

In the outline above the element ‘For sale’ is the fifth stage of resolution or return (though things are not exactly they were before). But it also doubles up, quite brilliantly, as the first stage of the story; the setting (by way of expectations bound up in buying for and putting up for sale).

The doubling up means it’s one of those two-faced elements I mentioned in How to Write Twitter Stories. Here it also triples up by delineating the format or genre, a short story masquerading as an advert. (Elements do not just carry narrative stages.) The opening few words of a twitter story will often do that, though it’s not always necessary.

For example @tweetthemeat‘s stories are always some gut-churning tale so there’s little need to tell it’s readership that what’s coming is a horror story.

So, this first element does at least three or four different things, even if the reader hasn’t recognised them yet.

For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

Basically everything spins around on that one word ‘baby’. It’s a story about a baby. Babies have mothers, fathers, grandmothers, and complicated social systems for organising marriages and mothers-in-law. People make lots of decisions once a baby is expected, and they do a lot too. The word ‘baby’ lets the reader make a lot of safe assumptions, once they get the key.

This ‘baby shoes’ is the middle of the story as written but is actually a part of the setting (1) and the resolution (5). This element also let’s you know, possibly, who is writing, just as ‘for sale’ says what they did. Once you know this you will most likely make those safe assumptions of how they recognise, respond, and resolve the situation. But you can’t do that until you know what the disruption (2) is.

(I say ‘you’ but I mean the reader. Somehow, you know what I mean.)

Hemingway’s choice of shoes rather than bonnet or nappies (diapers) is a very important part of the element. Shoes indicate are certain willingness to invest, particularly for fast growing baby feet. Expectations are high, and so, perhaps, the need to recoup that loss, whereas a new bonnet might just be handed on.

For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

And here the last element ‘never worn’ provides the key which allows the reader to connect the dots and fill in all the missing stages that the word ‘baby’ indicates, and to put them in order, creating the story in the reader’s ken.

The baby lost is the disruption to the setting, the expectations. But it is not mentioned directly. Neither is the response, one assumes, of grief.

(Perhaps the baby is fine and the shoes merely forgotten about until they were outgrown, but, if so, that’s not a story, and is not the immediate reaction of a human who is used to telling and hearing stories. People go for a story everytime.)

Immediately on reading these last two words, in the element carrying resolution (5), and almost in place of that unmentioned pain, we grieve. We see that expectations were not met; a baby was lost. We, as readers, recognize everything about that situation, and this is the strength of the story. That empathy is not a fiction, we feel it, suddenly and terribly. We feel sad for the lost baby.

As readers it affect us so strongly, in part, because the recognition (stage 3 in the outline of the story) is combined with our own recognition of the entire story, thus reinforcing it, tellingly. At this point we enter the story ourselves, as potential buyers the advert seeks to entice. Emotion suspends our disbelief.

And then we too may respond, but not in relief.

“Oh, but I don’t think I could buy…”

And thus elements of the story become a part of us, just as the story structure has been a part of our habits since we were babies ourselves.

For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

Hemingway’s story directly inspired the twitter story of mine that @thaumatrope published. (Had to use a few more words though. Very annoying.)

For sale. Spacesuit, dry cleaned inside. Used once.

.

Tagged: Hemingway, twitter fiction

Вы точно читали эту историю в интернете. Обычно она звучит примерно так:

«Однажды Эрнест Хемингуэй поспорил, что сможет написать самый короткий рассказ, способный растрогать любого. Он выиграл спор, написав рассказ из шести слов: «Продаются детские ботиночки. Неношеные» (в оригинале – «For sale: baby shoes, never worn»).

В различных версиях к этой истории добавляются детали: Хемингуэй спорил с другими писателями, написал рассказ на салфетке и выиграл с каждого участника спора по $10.

Исследование сайта Quote Investigator (проверяет популярные цитаты на подлинность) доказывает, что Хемингуэй никогда не публиковал подобную историю. И только спустя 30 лет после его смерти сложился миф, что он Хемингуэй – автор «самого грустного рассказа».

Это главный миф о писателе, а рассказ давно стал шаблоном для шутки. Как так вышло, что история приписывается именно Хемингуэю?

История про неношеные ботинки не оригинальна – и десятки раз появлялась в объявлениях и в советах для писателей

Хемингуэю было 10 лет, когда история о неношеных ботиночках впервые появилась в газете. В 1910 году в издании вашингтонском издании The Spokane выходит заметка автора, который пишет, что его поразило объявление в местной газете: «Продается детское приданое ручной работы и детская кровать. Никогда не использовалась». Но автор сомневается в правдивости и считает, что объявление специально давит на жалость.

В 1917 году автор Уильям Кейн пишет в журнал «Редактор» советы писателям, как рассказать историю женщины, которая переживает смерть ребенка. Кейн предлагает авторам «идеальное название» – «Маленькие туфельки, которые никогда не носили». Кейн считает, что лучший выход для женщины – отдать туфельки другому ребенку: «Возвращение женщины к нормальной жизни может символизироваться раздачей пары туфель, над которыми она часто плакала, нуждающемуся ребенку другой матери».

В 1921-м история уже пародируется в газетном анекдоте. Мужчина звонит посочувствовать семье, которая опубликовала объявление: «Продается детская коляска. Неиспользованная». Но оказалось, что у семьи родилась двойня.

К тому моменту, история о неношеных детских вещах еще несколько раз упоминается в размышлениях американских драматургов – они пишут, что эта история – идеал короткого и запоминающегося рассказа.

Откуда появился миф, что Хемингуэй – автор рассказа? Все пути ведут к байке литературного агента

Впервые о «коротком рассказе Хемингуэя» написал литературный агент Питер Миллер в 1991 году. Все детали на месте: спор писателей на 10 долларов и гениальный ответ Хемингуэя на салфетке. Миллер говорит, что услышал историю в 1974 году от «хорошо зарекомендовавшего» работника газеты.

В 2006 году Миллер повторил историю с Хемингуэем уже в новой книге. Но одна деталь изменилась – спор писателей начался в другом ресторане. Миллер при этом не приводит никаких доказательств и просто развивает мысль, что в рассказе кроется вся гениальность Хемингуэя – в умении за несколько слов поразить читателя.

В 1997-м байка Миллера появляется в газете New York Times, а еще через год – в эссе писателя-фантаста Артура Кларка, который пишет, что Хемингуэй – автор самого короткого и душераздирающего рассказа в истории литературы.

В нулевых-десятых годах «история Хемингуэя» распространяется в интернете как интересный и необычный факт литературы. Исследователи творчества писателя и журналисты сразу разбивают правдивость байки.

Например, журнал The Times в 2019 году проводил расследование и подтвердил миф – нет никаких явных доказательств, что Хемингуэй участвовал в споре (где хоть еще один его участник?) и сочинял тот самый рассказ.

A piercingly dark piece of writing, taking the heart of a Dickens or Dostoevsky novel and carving away all the rest, Ernest Hemingway’s six-word story—fabled forerunner of flash- and twitter-fiction—is shorter than many a story’s title:

For sale, Baby shoes, Never worn.

The extreme terseness in this elliptical tragedy has made it a favorite example of writing teachers over the past several decades, a display of the power of literary compression in which, writes a querent to the site Quote Investigator, “the reader must cooperate in the construction of the larger narrative that is obliquely limned by these words.” Supposedly composed sometime in the ’20s at The Algonquin (or perhaps Luchow’s, depending on whom you ask), the six-word story, it’s said, came from a ten-dollar bet Hemingway made at a lunch with some other writers that he could write a novel in six words. After penning the famous line on a napkin, he passed it around the table, and collected his winnings. That’s the popular lore, anyway. But the truth is much less colorful.

In fact, it seems that versions of the six-word story appeared long before Hemingway even began to write, at least as early as 1906, when he was only 7, in a newspaper classified section called “Terse Tales of the Town,” which published an item that read, “For sale, baby carriage, never been used. Apply at this office.” Another, very similar, version appeared in 1910, then another, suggested as the title for a story about “a wife who has lost her baby,” in a 1917 essay by William R. Kane, who thought up “Little Shoes, Never Worn.” Then again in 1920, writes David Haglund in Slate, the supposed Hemingway line appears in a “1921 newspaper column by Roy K. Moulton, who ‘printed a brief note that he attributed to someone named Jerry,’”:

There was an ad in the Brooklyn “Home Talk” which read, “Baby carriage for sale, never used.” Would that make a wonderful plot for the movies?

Many more examples of the narrative device abound, including a 1927 comic strip describing a seven-word version—“For Sale, A Baby Carriage; Never Used!”—as “the greatest short story in the world.” The more that Haglund and Quote Investigator’s Garson O’Toole looked into the matter, the harder they found it to “believe that Hemingway had anything to do with the tale.”

It is possible Hemingway, wittingly or not, stole the story from the classifieds or elsewhere. He was a newspaperman after all, perhaps guaranteed to have come into contact with some version of it. But there’s no evidence that he wrote or talked about the six-word story, or that the lunch bet at The Algonquin ever took place. Instead, it appears that a literary agent, Peter Miller, made up the story whole cloth in 1974 and later published it in his 1991 book, Get Published! Get Produced!: A Literary Agent’s Tips on How to Sell Your Writing.

The legend of the bet and the six-word story grew: Arthur C. Clarke repeated it in a 1998 Reader’s Digest essay, and Miller mentioned it again in a 2006 book. Meanwhile, suspicions arose, and the final debunking occurred in a 2012 scholarly article in The Journal of Popular Culture by Frederick A. Wright, who concluded that no evidence links the six-word story to Hemingway.

So should we blame Miller for ostensibly creating an urban legend, or thank him for giving competitive minimalists something to beat, and inspiring the entire genre of the “six-word memoir”? That depends, I suppose, on what you think of competitive minimalists and six-word memoirs. Perhaps the moral of the story, fitting in the Twitter age, is that the great man theory of authorship so often gets it wrong; the most memorable stories and ideas can arise spontaneously, anonymously, from anywhere.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934

Ernest Hemingway’s Very First Published Stories, Free as an eBook

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Download 55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“For sale, Baby shoes, Never Worn.”

The legends surrounding Ernest Hemingway can be as interesting as the plots of his novels. The author was famous for his personal life, but some of “Papa’s” adventures verge into apocrypha.

The above “story” is so short that it could fit into a title yet it resonates with depth and tragedy. This particular quote, supposedly originating in the 1920s, served as confirmation of Hemingway’s extraordinary talent and wit. It has also influenced numerous attempts to create a story in the six words frame, so-called flash or sudden fiction, giving only a glimpse of a story but in that glimpse delivering so much more.

This particular story was believed to be written on a napkin in Luchow’s restaurant in Manhattan, while another version of the story claims that it was composed in the Algonquin Hotel, where a circle of New York intellectuals (known as the Algonquin Round Table) enjoyed discussions–and drinking–during lunch time. This is only the first of the discrepancies that surround this legend, for no one can say with certainty where it happened, or when, and witnesses are elusive.

Ernest Hemingway

Allegedly, the story was a result of a $10 bet among Hemingway and several writers at a lunch spiced with wordplay. Hemingway asked each of his colleagues to place a $10 wager, and in return, he would match it. His task was to create this shortest of stories. The only problem is, Hemingway probably never wrote it.

Or if he did, the story wasn’t entirely his invention. Similar “ads” have been recorded as early as 1906. According to the Quote Investigator, an earlier version of this minimal sentence was “For Sale, Baby Carriage, Never Used,” published in a newspaper section called Terse Tales of the Town.

Whether this was a bad joke or someone’s sad memory, we will never know. There are also two other versions written years before the supposed Hemingway bet was placed. One of them was an essay by William R. Kane, about a certain “wife who has lost her baby.” It was published in 1917, by the title “Little Shoes, Never Worn.”

The “carriage” version was repeated in 1921, appearing in a column written by Roy K. Moulton, which held an ad attributed to an anonymous real-life character simply called Jerry:

There was an ad in the Brooklyn “Home Talk” which read, “Baby carriage for sale, never used.” Would that make a wonderful plot for the movies?

A six-word “novel” regarding a pair of baby shoes is considered an extreme example of flash fiction. Author: JD Hancock CC BY 2.0

Let’s just assume that Ernest Hemingway was aware of these earlier versions and decided to cheat his way into winning a bet. After all, he very well acquainted with the world of reporters, journalists, and feuilleton writers. He could have known about the six-word punchline long before and could have used his wit to collect the wager and establish himself winner among potential rivals.

But, truth be told, there is no evidence that such a bet actually ever took place, nor that Hemingway ever used this intelligent quote to soften the hearts of sardonic writers.

Hemingway in uniform in Milan, 1918. He drove ambulances for two months until wounded.

The story can be traced to a book published in 1991, titled Get Published! Get Produced! A Literary Agent’s Tips on How to Sell Your Writing. The book was written by a literary agent, Peter Miller, who mentions the anecdote about the bet placed in Luchow’s, as he heard it from an older newspaper account:

Apparently, Ernest Hemingway was lunching at Luchow’s with a number of writers and claimed that he could write a short story that was only six words long. Of course, the other writers balked. Hemingway told each of them to put ten dollars in the middle of the table; if he was wrong, he said, he’d match it. If he was right, he would keep the entire pot. He quickly wrote six words down on a napkin and passed it around; Papa won the bet. The words were “FOR SALE, BABY SHOES, NEVER WORN.” A beginning, a middle and an end!

There have been several more accounts over the years that attributed the quote to Hemingway, including an article by Arthur C. Clarke in a 1998 Reader’s Digest essay. Miller mentioned it again in a 2006 book, cementing it as Hemingway’s brainchild.

Read another story from us: After his father committed suicide, Ernest Hemingway wrote: “I’ll probably go the same way”

It was not until 2012 that a true academic investigation took place in order to solve the mystery of the never worn shoes. The Journal of Popular Culture published an article written by Frederick A. Wright that examined the origins of this story and debunked it as false.

Many were probably disappointed to hear that the Nobel Prize-winning author wasn’t the man behind the heart-breaking story that he allegedly claimed was his best work. Nevertheless, the truth reveals something else―this false authorship only helped the story reach and inspire numerous people. These six words found their way into readers’ lives, and in the end, it doesn’t matter who wrote them. What matters is the impact it left on the way we perceive literature, as a compression of feelings that communicate directly with the human soul.