grep 'potato:' file.txt | sed 's/^.*: //'

grep looks for any line that contains the string potato:, then, for each of these lines, sed replaces (s/// — substitute) any character (.*) from the beginning of the line (^) until the last occurrence of the sequence : (colon followed by space) with the empty string (s/...// — substitute the first part with the second part, which is empty).

or

grep 'potato:' file.txt | cut -d -f2

For each line that contains potato:, cut will split the line into multiple fields delimited by space (-d — d = delimiter, = escaped space character, something like -d" " would have also worked) and print the second field of each such line (-f2).

or

grep 'potato:' file.txt | awk '{print $2}'

For each line that contains potato:, awk will print the second field (print $2) which is delimited by default by spaces.

or

grep 'potato:' file.txt | perl -e 'for(<>){s/^.*: //;print}'

All lines that contain potato: are sent to an inline (-e) Perl script that takes all lines from stdin, then, for each of these lines, does the same substitution as in the first example above, then prints it.

or

awk '{if(/potato:/) print $2}' < file.txt

The file is sent via stdin (< file.txt sends the contents of the file via stdin to the command on the left) to an awk script that, for each line that contains potato: (if(/potato:/) returns true if the regular expression /potato:/ matches the current line), prints the second field, as described above.

or

perl -e 'for(<>){/potato:/ && s/^.*: // && print}' < file.txt

The file is sent via stdin (< file.txt, see above) to a Perl script that works similarly to the one above, but this time it also makes sure each line contains the string potato: (/potato:/ is a regular expression that matches if the current line contains potato:, and, if it does (&&), then proceeds to apply the regular expression described above and prints the result).

Better with sed:

sed -n 's/^[one]: //p' < example.txt

With GNU grep with support for recent PCRE, you can also do:

grep -Po '^[one]: K.*' < example.txt

Or

grep -xPo '[one]: K.*' < example.txt

In any case, note that in most shells, [...] are glob operators. In grep [myword], [myword] is expanded to the list of files that match that, that is any file in the current directory whose name is m, y, w, o, r or d (and if there’s none, depending on the shell, the pattern is passed as-is to grep, or you get an error). So they must be quoted for the shell (with single quotes for instance as in the solutions here). For instance, if there’s a file called r in the current directory, and one called d, grep [myword] would become grep d r in all shells but fish.

[...] is also a special operator in regular expressions (very similar to the [...] glob operator), grep '[myword]' would match on lines that contain m, y, w, o, r or d. So you need to escape the opening [ for grep (for regular expressions) as well. That can be done with grep '[myword]' or grep '[[]myword]'.

^ is another regular expression operator that means: match at the beginning of the line only. So grep '^[myword]: ' matches on lines that start with [myword]:.

While grep is just meant to print matching lines (is not otherwise a stream editor like sed is), GNU grep added the non-standard -o option for it to print the matching portion(s) of the line (if non-empty). It also added the -P options to use perl compatible regular expressions (in PCRE) instead of basic ones without -P.

In recent PCREs, K is an operator that resets the start of the matching portion. So in grep -Po '^[one]: K.*', we do print the matching portion because of -o, but because of K, that matching portion becomes the sequence of characters (.*) that is found after [one]:.

There are various ways to print next word after pattern match or previous word before pattern match in Linux but in this article we will focus on grep and awk command along with other regex.

We will cover below topics in this article

- Print next word after pattern match

- Print last word before pattern match

- Print everything in line after pattern match

- Print content between two matched pattern

With grep we can use lookahead to lookbehind.

With positive lookahead q(?=u) matches q that is followed by a u, without making the u part of the match.

The construct for positive lookbehind is (?<=text) a pair of parentheses, with the opening parenthesis followed by a question mark, “less than” symbol, and an equals sign.

1. Print next word after pattern match using grep

1.1 Using lookbehind

Let’s look at some examples to print next word after pattern match. In the below example I print next word after pattern match i.e. field3

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP '(?<=field3 )[^ ]*'

field4

Similarly to print next word after pattern match of field2

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP '(?<=field2 )w+'

field3

ALSO READ: Solved «error: Failed dependencies:» Install/Remove rpm with dependencies Linux

1.2 Using perl extended pattern

Now we will use perl extended pattern to print next word after pattern match.

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP 'field3 Kw+'

field4

Here K means keep the stuff left of the K, don’t include it in $&

and w means match a «word» character

Some more examples:

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP 'field1 Kw+' field2 # echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP 'field2 Kw+' field3

2. Print next word after pattern match

2.1 Using awk

We showed various examples to print next word after pattern match using grep, now we will do the same with awk

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | awk '{if(/field2/) print $4 " " $2}' field4 field2 # echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | awk '{if(/field2/) print $4}' field4

Some more examples:

If first field is field1 then print $2

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | awk '$1 == "field1" {print $2}' field2 # echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | awk '$2 == "field2" {print $3}' field3

3. Print everything in line after pattern match

Now with lookbehind I showed examples to print next word after pattern match but to print everything in line after pattern match

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP '(?<=field2 ).*'

field3 field4

Some more example with little tweak

# echo "field1 field2 : field3 field4" | grep -oP '(?<=field2s: )[^ ]*'

field3

Here we use s to match whitespace character

ALSO READ: 4 practical examples with bash increment variable

4. Print content between two matched pattern

Now we can use both lookahead and lookbehind to print content between two matched pattern. Here I wish to print text between field1 and field3

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP '(?<=field1 )w+(?= field3)'

field2

We can do the same using perl extended patterns

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP 'field1 Kw+(?= field3)'

field2

5. Print last word before pattern match using grep with lookahead

Similar to lookbehind we can use lookahead to print last word before pattern match using grep

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP 'w+(?= field3)'

field2

6. Print everything in line before pattern match

To print everything in line before pattern match in Linux we can use lookahead with below regex

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -oP '.*(?= field3)'

field1 field2

7. Print everything in line after pattern match

Now you can also use lookbehind or other regex to print everything in line after pattern match

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -o "field2.*"

field2 field3 field4

To print everything on line before match

# echo "field1 field2 field3 field4" | grep -o ".*field2"

field1 field2

Lastly I hope the examples from this article to grep and print next word after pattern match on Linux was helpful. So, let me know your suggestions and feedback using the comment section.

ALSO READ: How to count occurrences of word in file using shell script in Linux

Didn’t find what you were looking for? Perform a quick search across GoLinuxCloud

Grep, or Global Regular Expression Print, is an extremely useful Linux command for finding matching patterns. It can look through files and directories, and read input from commands as well. It searches with regex, or regular expressions and prints lines from a file that matches the given pattern.

In this post, we’ll be looking at how to use the Grep command in Linux. The commands discussed here have been tested on Ubuntu 20.04. The same Grep commands also work for Debian, Mint, Fedora, and CentOS.

Installing grep command

Most Linux distributions including Ubuntu 20.04 LTS come with grep installed. In case your system does not have Grep installed, you can install it using the below command in Terminal:

$ Sudo apt-get install grep

Grep command syntax

The basic syntax of the Grep command is as follows:

$ grep [options] PATTERN [FILE...]

Finding a word in a file

With Grep, you can search any word in a specific file. The syntax would be:

$ grep <word> <filename>

For instance, the below command will look for the word “Donuts” in the file “Donuts.txt”.

$ grep Donuts Donuts.txt

Finding a word in multiple files

You can also search for a specific word in multiple files.

$ grep <word> <filename1> < filename2>

For instance, the below command will look for the word “Donuts” in both “Donuts.txt” and “cakes.txt”.

$ grep Donuts Donuts.txt cakes.txt

Ignoring case

Grep performs case-sensitive searches by default, this means that it treats “Donut” and “donuts” differently. If we again run the above command with “donuts”, you will see no output this time.

$ grep donuts Donuts.txt

To ignore the case, you will need to add “-i” to your command like this:

$ grep –i <word> <filename>

Finding a file by extension in a directory

You can also find a file in a specific directory by its extension. Use the following syntax to do so:

$ ls ~/<directory> | grep .<file type>

For instance, to find all “.jpeg” files in the “Downloads” folder, the command would be:

$ ls ~/Downloads | grep .jpeg

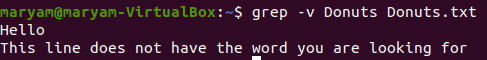

Printing lines that do not match a pattern

With Grep, you can also print the lines that don’t match your pattern by adding “-v” to your command. Use the following syntax to do so:

$ grep -v <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print all the lines except the one which contains the word “Donuts” in it.

Printing only the matching word

By default, grep prints the whole line that contains the pattern. To print just the matching word, add “-o” to your command.

$ grep -o <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print only the word “Donuts” instead of printing the entire line from the file “Donuts.txt”.

Printing line number of matching pattern and line

By default, grep prints the entire line that contains the pattern. To print both the line number and line that contains the matching word, add “-n” to your command.

$ grep -n <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print both the line number and the line that contains the word “Donuts”.

$ grep -n Donuts Donuts.txt

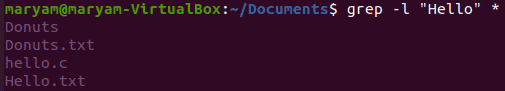

Printing file names that match a pattern

To print all the files in your current directory that match your pattern, use the following syntax:

$ grep -l “<word>” *

For instance, the following command will print all the files that contain the word “Hello”:

$ grep -l “Hello” *

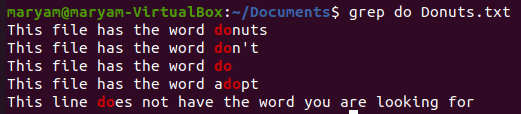

Printing the whole matching word

By default, grep prints all the words that match your pattern, even if they are part of a word. Look at the image below.

We searched for the string “do” and can see all the lines that contain “do”. To match the exact word, add “-w” to your command.

$ grep –w <word> <filename>

For instance, to search the exact word “do” in the Donuts.txt file, the command would be:

$ grep -w do Donuts.txt

As you can see, it now only prints the line that contains the exact word “do”.

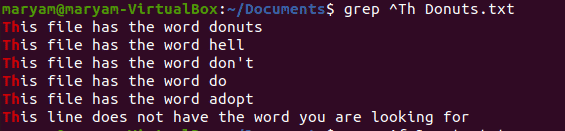

Matching lines that start with a particular word

To print lines that start with a particular word, add “^” to your command.

$ grep ^<word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print all the lines that start with “Th”.

$ grep ^Th Donuts.txt

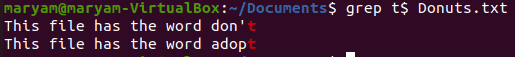

Matching lines that end with a pattern

To print lines that end with a particular pattern, add “$” to your command.

$ grep <word>$ <filename>

For instance, the following command will print all the lines that end with “t”.

$ grep t$ Donuts.txt

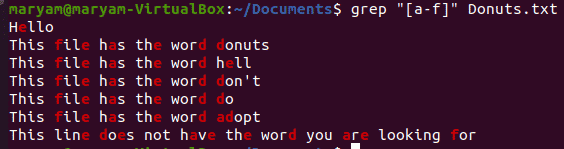

Matching lines that contain certain letters

If you want to look for lines that have one or multiple letters in them, use the following syntax:

$ grep “[<letters>]” <filename>

For instance, the following command print all the lines that contain any letter from “a” to “f”.

$ grep “[a-f]” Donuts.txt

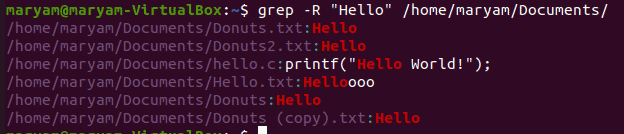

Recursive Search

To look up all the files in a directory and sub-directory for a particular pattern or word, use:

$ grep -R <word> <path>

For instance, the following command will list all the files that contain the word “Hello” in the Documents directory. In the below output, you can see the file paths along with the matching words.

$ grep -R “Hello” /home/maryam/Documents

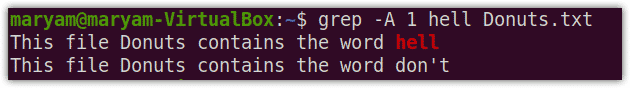

Printing specific lines before/after the matched words

By default, Grep prints only the line that matched the specific pattern. With -A option in Grep, you can also include some lines before or after the matched words.

Printing lines after the match

To print the lines that contain the matched words including N number of lines after the matches:

$ grep -A <N> <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print the line containing the word “hell” along with 1 line after it.

$ grep -A 1 hell Donuts.txt

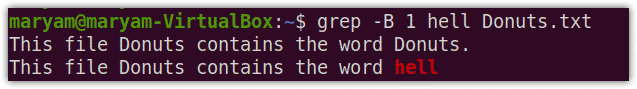

Printing lines before the match

To print the lines that contain the matched words including N number of lines before the matches:

$ grep -B <N> <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print the line containing the word “hell” along with 1 line before it.

$ grep -B 1 hell Donuts.txt

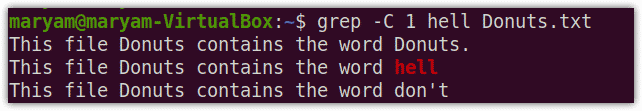

Printing lines before and after the match

To print the lines that contain the matched words including N number of lines before and after the matches:

$ grep -C <N> <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command will print the line containing the word “hell” along with 1 line before and after it.

$ grep -C 1 hell Donuts.txt

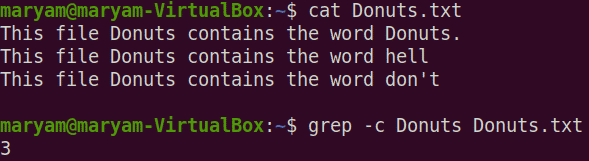

Counting the number of matches

Using the -c option with grep, you can count the lines that match a specific pattern. Remember, it will only match the number of lines not the number of matched words.

$ grep -c <word> <filename>

For instance, the following command prints the count of lines that contains the word “Donuts”.

$ grep -c Donuts Donuts.txt

Note that our file “Donuts.txt” contains 4 “Donuts”, but -c has only printed the count as 3. It happens because it counts the number of lines instead of the number of matches.

For more information regarding grep, use the below command:

$ grep --help

or visit the man page using the below command:

$ man grep

This will take you to the Grep manual page.

That is all there is to it! In this post, we have explained the basic syntax and usage of the grep command in Linux. We also went through some command-line options to expand its usefulness. If you know some other uses of the Grep command in Linux that we have missed, we would love to know about them in the comments below.

Explore this related article to find out how you can find files and directories in Linux.

Karim Buzdar holds a degree in telecommunication engineering and holds several sysadmin certifications including CCNA RS, SCP, and ACE. As an IT engineer and technical author, he writes for various websites.

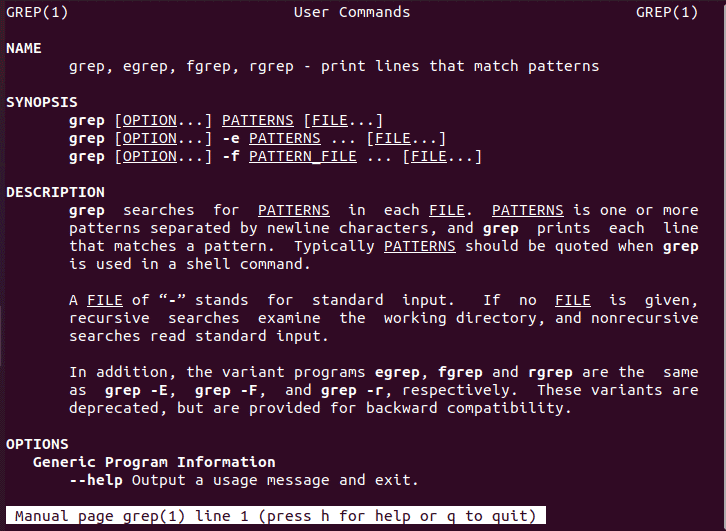

grep — Man Page

print lines that match patterns

Examples (TL;DR)

- Search for a pattern within a file:

grep "search_pattern" path/to/file - Search for an exact string (disables regular expressions):

grep --fixed-strings "exact_string" path/to/file - Search for a pattern in all files recursively in a directory, showing line numbers of matches, ignoring binary files:

grep --recursive --line-number --binary-files=without-match "search_pattern" path/to/directory - Use extended regular expressions (supports

?,+,{},()and|), in case-insensitive mode:grep --extended-regexp --ignore-case "search_pattern" path/to/file - Print 3 lines of context around, before, or after each match:

grep --context|before-context|after-context=3 "search_pattern" path/to/file - Print file name and line number for each match with color output:

grep --with-filename --line-number --color=always "search_pattern" path/to/file - Search for lines matching a pattern, printing only the matched text:

grep --only-matching "search_pattern" path/to/file - Search

stdinfor lines that do not match a pattern:cat path/to/file | grep --invert-match "search_pattern"

tldr.sh

Synopsis

grep [OPTION...] PATTERNS [FILE...]

grep [OPTION...] -e PATTERNS ... [FILE...]

grep [OPTION...] -f PATTERN_FILE ... [FILE...]

Description

grep searches for PATTERNS in each FILE. PATTERNS is one or more patterns separated by newline characters, and grep prints each line that matches a pattern. Typically PATTERNS should be quoted when grep is used in a shell command.

A FILE of “—” stands for standard input. If no FILE is given, recursive searches examine the working directory, and nonrecursive searches read standard input.

Options

Generic Program Information

- —help

-

Output a usage message and exit.

- -V, —version

-

Output the version number of grep and exit.

Pattern Syntax

- -E, —extended-regexp

-

Interpret PATTERNS as extended regular expressions (EREs, see below).

- -F, —fixed-strings

-

Interpret PATTERNS as fixed strings, not regular expressions.

- -G, —basic-regexp

-

Interpret PATTERNS as basic regular expressions (BREs, see below). This is the default.

- -P, —perl-regexp

-

Interpret PATTERNS as Perl-compatible regular expressions (PCREs). This option is experimental when combined with the -z (—null-data) option, and grep -P may warn of unimplemented features.

Matching Control

- -e PATTERNS, —regexp=PATTERNS

-

Use PATTERNS as the patterns. If this option is used multiple times or is combined with the -f (—file) option, search for all patterns given. This option can be used to protect a pattern beginning with “-”.

- -f FILE, —file=FILE

-

Obtain patterns from FILE, one per line. If this option is used multiple times or is combined with the -e (—regexp) option, search for all patterns given. The empty file contains zero patterns, and therefore matches nothing.

- -i, —ignore-case

-

Ignore case distinctions in patterns and input data, so that characters that differ only in case match each other.

- —no-ignore-case

-

Do not ignore case distinctions in patterns and input data. This is the default. This option is useful for passing to shell scripts that already use -i, to cancel its effects because the two options override each other.

- -v, —invert-match

-

Invert the sense of matching, to select non-matching lines.

- -w, —word-regexp

-

Select only those lines containing matches that form whole words. The test is that the matching substring must either be at the beginning of the line, or preceded by a non-word constituent character. Similarly, it must be either at the end of the line or followed by a non-word constituent character. Word-constituent characters are letters, digits, and the underscore. This option has no effect if -x is also specified.

- -x, —line-regexp

-

Select only those matches that exactly match the whole line. For a regular expression pattern, this is like parenthesizing the pattern and then surrounding it with ^ and $.

General Output Control

- -c, —count

-

Suppress normal output; instead print a count of matching lines for each input file. With the -v, —invert-match option (see above), count non-matching lines.

- —color[=WHEN], —colour[=WHEN]

-

Surround the matched (non-empty) strings, matching lines, context lines, file names, line numbers, byte offsets, and separators (for fields and groups of context lines) with escape sequences to display them in color on the terminal. The colors are defined by the environment variable GREP_COLORS. WHEN is never, always, or auto.

- -L, —files-without-match

-

Suppress normal output; instead print the name of each input file from which no output would normally have been printed.

- -l, —files-with-matches

-

Suppress normal output; instead print the name of each input file from which output would normally have been printed. Scanning each input file stops upon first match.

- -m NUM, —max-count=NUM

-

Stop reading a file after NUM matching lines. If NUM is zero, grep stops right away without reading input. A NUM of -1 is treated as infinity and grep does not stop; this is the default. If the input is standard input from a regular file, and NUM matching lines are output, grep ensures that the standard input is positioned to just after the last matching line before exiting, regardless of the presence of trailing context lines. This enables a calling process to resume a search. When grep stops after NUM matching lines, it outputs any trailing context lines. When the -c or —count option is also used, grep does not output a count greater than NUM. When the -v or —invert-match option is also used, grep stops after outputting NUM non-matching lines.

- -o, —only-matching

-

Print only the matched (non-empty) parts of a matching line, with each such part on a separate output line.

- -q, —quiet, —silent

-

Quiet; do not write anything to standard output. Exit immediately with zero status if any match is found, even if an error was detected. Also see the -s or —no-messages option.

- -s, —no-messages

-

Suppress error messages about nonexistent or unreadable files.

Output Line Prefix Control

- -b, —byte-offset

-

Print the 0-based byte offset within the input file before each line of output. If -o (—only-matching) is specified, print the offset of the matching part itself.

- -H, —with-filename

-

Print the file name for each match. This is the default when there is more than one file to search. This is a GNU extension.

- -h, —no-filename

-

Suppress the prefixing of file names on output. This is the default when there is only one file (or only standard input) to search.

- —label=LABEL

-

Display input actually coming from standard input as input coming from file LABEL. This can be useful for commands that transform a file’s contents before searching, e.g., gzip -cd foo.gz | grep —label=foo -H ‘some pattern’. See also the -H option.

- -n, —line-number

-

Prefix each line of output with the 1-based line number within its input file.

- -T, —initial-tab

-

Make sure that the first character of actual line content lies on a tab stop, so that the alignment of tabs looks normal. This is useful with options that prefix their output to the actual content: -H,-n, and -b. In order to improve the probability that lines from a single file will all start at the same column, this also causes the line number and byte offset (if present) to be printed in a minimum size field width.

- -Z, —null

-

Output a zero byte (the ASCII NUL character) instead of the character that normally follows a file name. For example, grep -lZ outputs a zero byte after each file name instead of the usual newline. This option makes the output unambiguous, even in the presence of file names containing unusual characters like newlines. This option can be used with commands like find -print0, perl -0, sort -z, and xargs -0 to process arbitrary file names, even those that contain newline characters.

Context Line Control

- -A NUM, —after-context=NUM

-

Print NUM lines of trailing context after matching lines. Places a line containing a group separator (—) between contiguous groups of matches. With the -o or —only-matching option, this has no effect and a warning is given.

- -B NUM, —before-context=NUM

-

Print NUM lines of leading context before matching lines. Places a line containing a group separator (—) between contiguous groups of matches. With the -o or —only-matching option, this has no effect and a warning is given.

- -C NUM, -NUM, —context=NUM

-

Print NUM lines of output context. Places a line containing a group separator (—) between contiguous groups of matches. With the -o or —only-matching option, this has no effect and a warning is given.

- —group-separator=SEP

-

When -A, -B, or -C are in use, print SEP instead of — between groups of lines.

- —no-group-separator

-

When -A, -B, or -C are in use, do not print a separator between groups of lines.

File and Directory Selection

- -a, —text

-

Process a binary file as if it were text; this is equivalent to the —binary-files=text option.

- —binary-files=TYPE

-

If a file’s data or metadata indicate that the file contains binary data, assume that the file is of type TYPE. Non-text bytes indicate binary data; these are either output bytes that are improperly encoded for the current locale, or null input bytes when the -z option is not given.

By default, TYPE is binary, and grep suppresses output after null input binary data is discovered, and suppresses output lines that contain improperly encoded data. When some output is suppressed, grep follows any output with a message to standard error saying that a binary file matches.

If TYPE is without-match, when grep discovers null input binary data it assumes that the rest of the file does not match; this is equivalent to the -I option.

If TYPE is text, grep processes a binary file as if it were text; this is equivalent to the -a option.

When type is binary, grep may treat non-text bytes as line terminators even without the -z option. This means choosing binary versus text can affect whether a pattern matches a file. For example, when type is binary the pattern q$ might match q immediately followed by a null byte, even though this is not matched when type is text. Conversely, when type is binary the pattern . (period) might not match a null byte.

Warning: The -a option might output binary garbage, which can have nasty side effects if the output is a terminal and if the terminal driver interprets some of it as commands. On the other hand, when reading files whose text encodings are unknown, it can be helpful to use -a or to set LC_ALL=’C’ in the environment, in order to find more matches even if the matches are unsafe for direct display.

- -D ACTION, —devices=ACTION

-

If an input file is a device, FIFO or socket, use ACTION to process it. By default, ACTION is read, which means that devices are read just as if they were ordinary files. If ACTION is skip, devices are silently skipped.

- -d ACTION, —directories=ACTION

-

If an input file is a directory, use ACTION to process it. By default, ACTION is read, i.e., read directories just as if they were ordinary files. If ACTION is skip, silently skip directories. If ACTION is recurse, read all files under each directory, recursively, following symbolic links only if they are on the command line. This is equivalent to the -r option.

- —exclude=GLOB

-

Skip any command-line file with a name suffix that matches the pattern GLOB, using wildcard matching; a name suffix is either the whole name, or a trailing part that starts with a non-slash character immediately after a slash (/) in the name. When searching recursively, skip any subfile whose base name matches GLOB; the base name is the part after the last slash. A pattern can use *, ?, and […] as wildcards, and to quote a wildcard or backslash character literally.

- —exclude-from=FILE

-

Skip files whose base name matches any of the file-name globs read from FILE (using wildcard matching as described under —exclude).

- —exclude-dir=GLOB

-

Skip any command-line directory with a name suffix that matches the pattern GLOB. When searching recursively, skip any subdirectory whose base name matches GLOB. Ignore any redundant trailing slashes in GLOB.

- -I

-

Process a binary file as if it did not contain matching data; this is equivalent to the —binary-files=without-match option.

- —include=GLOB

-

Search only files whose base name matches GLOB (using wildcard matching as described under —exclude). If contradictory —include and —exclude options are given, the last matching one wins. If no —include or —exclude options match, a file is included unless the first such option is —include.

- -r, —recursive

-

Read all files under each directory, recursively, following symbolic links only if they are on the command line. Note that if no file operand is given, grep searches the working directory. This is equivalent to the -d recurse option.

- -R, —dereference-recursive

-

Read all files under each directory, recursively. Follow all symbolic links, unlike -r.

Other Options

- —line-buffered

-

Use line buffering on output. This can cause a performance penalty.

- -U, —binary

-

Treat the file(s) as binary. By default, under MS-DOS and MS-Windows, grep guesses whether a file is text or binary as described for the —binary-files option. If grep decides the file is a text file, it strips the CR characters from the original file contents (to make regular expressions with ^ and $ work correctly). Specifying -U overrules this guesswork, causing all files to be read and passed to the matching mechanism verbatim; if the file is a text file with CR/LF pairs at the end of each line, this will cause some regular expressions to fail. This option has no effect on platforms other than MS-DOS and MS-Windows.

- -z, —null-data

-

Treat input and output data as sequences of lines, each terminated by a zero byte (the ASCII NUL character) instead of a newline. Like the -Z or —null option, this option can be used with commands like sort -z to process arbitrary file names.

Regular Expressions

A regular expression is a pattern that describes a set of strings. Regular expressions are constructed analogously to arithmetic expressions, by using various operators to combine smaller expressions.

grep understands three different versions of regular expression syntax: “basic” (BRE), “extended” (ERE) and “perl” (PCRE). In GNU grep there is no difference in available functionality between basic and extended syntax. In other implementations, basic regular expressions are less powerful. The following description applies to extended regular expressions; differences for basic regular expressions are summarized afterwards. Perl-compatible regular expressions give additional functionality, and are documented in pcre2syntax(3) and pcre2pattern(3), but work only if PCRE support is enabled.

The fundamental building blocks are the regular expressions that match a single character. Most characters, including all letters and digits, are regular expressions that match themselves. Any meta-character with special meaning may be quoted by preceding it with a backslash.

The period . matches any single character. It is unspecified whether it matches an encoding error.

Character Classes and Bracket Expressions

A bracket expression is a list of characters enclosed by [ and ]. It matches any single character in that list. If the first character of the list is the caret ^ then it matches any character not in the list; it is unspecified whether it matches an encoding error. For example, the regular expression [0123456789] matches any single digit.

Within a bracket expression, a range expression consists of two characters separated by a hyphen. It matches any single character that sorts between the two characters, inclusive, using the locale’s collating sequence and character set. For example, in the default C locale, [a-d] is equivalent to [abcd]. Many locales sort characters in dictionary order, and in these locales [a-d] is typically not equivalent to [abcd]; it might be equivalent to [aBbCcDd], for example. To obtain the traditional interpretation of bracket expressions, you can use the C locale by setting the LC_ALL environment variable to the value C.

Finally, certain named classes of characters are predefined within bracket expressions, as follows. Their names are self explanatory, and they are [:alnum:], [:alpha:], [:blank:], [:cntrl:], [:digit:], [:graph:], [:lower:], [:print:], [:punct:], [:space:], [:upper:], and [:xdigit:]. For example, [[:alnum:]] means the character class of numbers and letters in the current locale. In the C locale and ASCII character set encoding, this is the same as [0-9A-Za-z]. (Note that the brackets in these class names are part of the symbolic names, and must be included in addition to the brackets delimiting the bracket expression.) Most meta-characters lose their special meaning inside bracket expressions. To include a literal ] place it first in the list. Similarly, to include a literal ^ place it anywhere but first. Finally, to include a literal — place it last.

Anchoring

The caret ^ and the dollar sign $ are meta-characters that respectively match the empty string at the beginning and end of a line.

The Backslash Character and Special Expressions

The symbols < and > respectively match the empty string at the beginning and end of a word. The symbol b matches the empty string at the edge of a word, and B matches the empty string provided it’s not at the edge of a word. The symbol w is a synonym for [_[:alnum:]] and W is a synonym for [^_[:alnum:]].

Repetition

A regular expression may be followed by one of several repetition operators:

- ?

-

The preceding item is optional and matched at most once.

- *

-

The preceding item will be matched zero or more times.

- +

-

The preceding item will be matched one or more times.

- {n}

-

The preceding item is matched exactly n times.

- {n,}

-

The preceding item is matched n or more times.

- {,m}

-

The preceding item is matched at most m times. This is a GNU extension.

- {n,m}

-

The preceding item is matched at least n times, but not more than m times.

Concatenation

Two regular expressions may be concatenated; the resulting regular expression matches any string formed by concatenating two substrings that respectively match the concatenated expressions.

Alternation

Two regular expressions may be joined by the infix operator |; the resulting regular expression matches any string matching either alternate expression.

Precedence

Repetition takes precedence over concatenation, which in turn takes precedence over alternation. A whole expression may be enclosed in parentheses to override these precedence rules and form a subexpression.

Back-references and Subexpressions

The back-reference n, where n is a single digit, matches the substring previously matched by the nth parenthesized subexpression of the regular expression.

Basic vs Extended Regular Expressions

In basic regular expressions the meta-characters ?, +, {, |, (, and ) lose their special meaning; instead use the backslashed versions ?, +, {, |, (, and ).

Exit Status

Normally the exit status is 0 if a line is selected, 1 if no lines were selected, and 2 if an error occurred. However, if the -q or —quiet or —silent is used and a line is selected, the exit status is 0 even if an error occurred.

Environment

The behavior of grep is affected by the following environment variables.

The locale for category LC_foo is specified by examining the three environment variables LC_ALL, LC_foo, LANG, in that order. The first of these variables that is set specifies the locale. For example, if LC_ALL is not set, but LC_MESSAGES is set to pt_BR, then the Brazilian Portuguese locale is used for the LC_MESSAGES category. The C locale is used if none of these environment variables are set, if the locale catalog is not installed, or if grep was not compiled with national language support (NLS). The shell command locale -a lists locales that are currently available.

- GREP_COLORS

-

Controls how the —color option highlights output. Its value is a colon-separated list of capabilities that defaults to ms=01;31:mc=01;31:sl=:cx=:fn=35:ln=32:bn=32:se=36 with the rv and ne boolean capabilities omitted (i.e., false). Supported capabilities are as follows.

- sl=

-

SGR substring for whole selected lines (i.e., matching lines when the -v command-line option is omitted, or non-matching lines when -v is specified). If however the boolean rv capability and the -v command-line option are both specified, it applies to context matching lines instead. The default is empty (i.e., the terminal’s default color pair).

- cx=

-

SGR substring for whole context lines (i.e., non-matching lines when the -v command-line option is omitted, or matching lines when -v is specified). If however the boolean rv capability and the -v command-line option are both specified, it applies to selected non-matching lines instead. The default is empty (i.e., the terminal’s default color pair).

- rv

-

Boolean value that reverses (swaps) the meanings of the sl= and cx= capabilities when the -v command-line option is specified. The default is false (i.e., the capability is omitted).

- mt=01;31

-

SGR substring for matching non-empty text in any matching line (i.e., a selected line when the -v command-line option is omitted, or a context line when -v is specified). Setting this is equivalent to setting both ms= and mc= at once to the same value. The default is a bold red text foreground over the current line background.

- ms=01;31

-

SGR substring for matching non-empty text in a selected line. (This is only used when the -v command-line option is omitted.) The effect of the sl= (or cx= if rv) capability remains active when this kicks in. The default is a bold red text foreground over the current line background.

- mc=01;31

-

SGR substring for matching non-empty text in a context line. (This is only used when the -v command-line option is specified.) The effect of the cx= (or sl= if rv) capability remains active when this kicks in. The default is a bold red text foreground over the current line background.

- fn=35

-

SGR substring for file names prefixing any content line. The default is a magenta text foreground over the terminal’s default background.

- ln=32

-

SGR substring for line numbers prefixing any content line. The default is a green text foreground over the terminal’s default background.

- bn=32

-

SGR substring for byte offsets prefixing any content line. The default is a green text foreground over the terminal’s default background.

- se=36

-

SGR substring for separators that are inserted between selected line fields (:), between context line fields, (—), and between groups of adjacent lines when nonzero context is specified (—). The default is a cyan text foreground over the terminal’s default background.

- ne

-

Boolean value that prevents clearing to the end of line using Erase in Line (EL) to Right (33[K) each time a colorized item ends. This is needed on terminals on which EL is not supported. It is otherwise useful on terminals for which the back_color_erase (bce) boolean terminfo capability does not apply, when the chosen highlight colors do not affect the background, or when EL is too slow or causes too much flicker. The default is false (i.e., the capability is omitted).

Note that boolean capabilities have no =… part. They are omitted (i.e., false) by default and become true when specified.

See the Select Graphic Rendition (SGR) section in the documentation of the text terminal that is used for permitted values and their meaning as character attributes. These substring values are integers in decimal representation and can be concatenated with semicolons. grep takes care of assembling the result into a complete SGR sequence (33[…m). Common values to concatenate include 1 for bold, 4 for underline, 5 for blink, 7 for inverse, 39 for default foreground color, 30 to 37 for foreground colors, 90 to 97 for 16-color mode foreground colors, 38;5;0 to 38;5;255 for 88-color and 256-color modes foreground colors, 49 for default background color, 40 to 47 for background colors, 100 to 107 for 16-color mode background colors, and 48;5;0 to 48;5;255 for 88-color and 256-color modes background colors.

- LC_ALL, LC_COLLATE, LANG

-

These variables specify the locale for the LC_COLLATE category, which determines the collating sequence used to interpret range expressions like [a-z].

- LC_ALL, LC_CTYPE, LANG

-

These variables specify the locale for the LC_CTYPE category, which determines the type of characters, e.g., which characters are whitespace. This category also determines the character encoding, that is, whether text is encoded in UTF-8, ASCII, or some other encoding. In the C or POSIX locale, all characters are encoded as a single byte and every byte is a valid character.

- LC_ALL, LC_MESSAGES, LANG

-

These variables specify the locale for the LC_MESSAGES category, which determines the language that grep uses for messages. The default C locale uses American English messages.

- POSIXLY_CORRECT

-

If set, grep behaves as POSIX requires; otherwise, grep behaves more like other GNU programs. POSIX requires that options that follow file names must be treated as file names; by default, such options are permuted to the front of the operand list and are treated as options. Also, POSIX requires that unrecognized options be diagnosed as “illegal”, but since they are not really against the law the default is to diagnose them as “invalid”. POSIXLY_CORRECT also disables _N_GNU_nonoption_argv_flags_, described below.

- _N_GNU_nonoption_argv_flags_

-

(Here N is grep‘s numeric process ID.) If the ith character of this environment variable’s value is 1, do not consider the ith operand of grep to be an option, even if it appears to be one. A shell can put this variable in the environment for each command it runs, specifying which operands are the results of file name wildcard expansion and therefore should not be treated as options. This behavior is available only with the GNU C library, and only when POSIXLY_CORRECT is not set.

Notes

This man page is maintained only fitfully; the full documentation is often more up-to-date.

Copyright

Copyright 1998-2000, 2002, 2005-2023 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

Bugs

Reporting Bugs

Email bug reports to the bug-reporting address ⟨bug-grep@gnu.org⟩. An email archive ⟨https://lists.gnu.org/mailman/listinfo/bug-grep⟩ and a bug tracker ⟨https://debbugs.gnu.org/cgi/pkgreport.cgi?package=grep⟩ are available.

Known Bugs

Large repetition counts in the {n,m} construct may cause grep to use lots of memory. In addition, certain other obscure regular expressions require exponential time and space, and may cause grep to run out of memory.

Back-references are very slow, and may require exponential time.

Example

The following example outputs the location and contents of any line containing “f” and ending in “.c”, within all files in the current directory whose names contain “g” and end in “.h”. The -n option outputs line numbers, the — argument treats expansions of “*g*.h” starting with “-” as file names not options, and the empty file /dev/null causes file names to be output even if only one file name happens to be of the form “*g*.h”.

$ grep -n -- 'f.*.c$' *g*.h /dev/null argmatch.h:1:/* definitions and prototypes for argmatch.c

The only line that matches is line 1 of argmatch.h. Note that the regular expression syntax used in the pattern differs from the globbing syntax that the shell uses to match file names.

See Also

Regular Manual Pages

awk(1), cmp(1), diff(1), find(1), perl(1), sed(1), sort(1), xargs(1), read(2), pcre2(3), pcre2syntax(3), pcre2pattern(3), terminfo(5), glob(7), regex(7)

Full Documentation

A complete manual ⟨https://www.gnu.org/software/grep/manual/⟩ is available. If the info and grep programs are properly installed at your site, the command

info grep

should give you access to the complete manual.

Referenced By

ag(1), bournal(1), bridge(8), bz3grep(1), bzgrep(1), cdist-type__pacman_conf(7), cdist-type__pacman_conf_integrate(7), flowdumper(1), fmidi-grep(1), fortune(6), fpart(1), getbuildlog(1), global(1), grepmail(1), guestfish(1), guestfs(3), ip(8), ksh93(1), lbzgrep(1), libinn_uwildmat(3), libxo(3), look(1), maildrop(1), maildropex(7), makeindex(1), makemime(1), mate-search-tool(1), mawk(1), mksh(1), mle(1), nawk(1), oksh(1), pass(1), patool(1), pdfgrep(1), pdsh(1), perlfunc(1), pick(1), pmrep(1), procmail(1), procmailex(5), procmailrc(5), procmailsc(5), pwqfilter(1), quilt(1), ragrep(1), reformime(1), regex(3), regex(7), ronn(1), ronn-format(7), sed(1), sudoers(5), tc(8), trace-cmd-record(1), trace-cmd-set(1), ugrep(1), xzgrep(1), zgrep(1), zstdgrep(1).

2019-12-29 GNU grep 3.9