What Greek word means to study?

meleti

Is Takis a Greek name?

Takis is a Greek form of the English Demetrius. Takis is an unusual baby name for boys.

What does Takis stand for?

The Amazing Karpen Island Skipper

What does Mitsuha mean?

three leaves

Did Mitsuha really die?

Taki and Mitsuha Forget Because Mitsuha never died, she and Taki now exist in present day. But because Taki gave Mitsuha back her red yarn, they forget one another.

Does Mitsuha die in your name?

Mitsuha, Teshi and Sayaka die too. The school is left unharmed and so is the shrine. This is how it ends for Mitsuha in Timeline 1. She dies.

Does Taki marry Mitsuha?

Due to their connection with the red string of fate, Taki and Mitsuha are fated lovers who were destined to eventually meet, despite time, circumstances, or place. According to the Tenki no Ko light novel, Taki and Mitsuha are married by the time of 2024.

Is Mitsuha older than Taki?

( Yes ) Mitsuha is 3 years older than Taki. And they were swapping their spirits frequently, beyond DISTANCE and TIME. (between 17years old Mitsuha and 17years old Taki) , That’s why they believed thy are the same age of 17.

Who did Mitsuha marry?

‘Kimi no Na wa Another Side: Earthbound’ is a light novel confirming the couple marrying in 2024, two years after Taki & Mitsuha reunited in the red Suga Shrine staircase! The 2016 light novel side story may or may not be considered canon (it depends on the readers after all).

Why did Mitsuha cut her hair?

in your name, mitsuha cuts her hair as a response to being “rejected” or “forgotten” by Taki. it could be a way of saying that she’ll move on or that she’s heart broken. also in avatar the last Airbender zuko cuts his hair after defecting from the fire nation when he goes into exile.

Why do they cry in your name?

At the end of the movie, however, Taki and Mitsuha do end up finding each other. Their memories are returned and, as they embrace, they cry. It’s not from finally finding each other or realizing they can be with the person they love, it’s an emotional release.

Does Tessie like Mitsuha?

During the main story, it’s pretty obvious that Tessie had a crush on Mitsuha. However, it is later shown during the alternate timeline that Taki and Mitsuha created that he and Sayaka are engaged. Tessie is not shown anywhere during the 2016 main story.

Will there be a your name 2?

While they keep their word, but to the delight of fans of the film, it can be reported that in 2021 the premiere of the anime remake is planned, where the events will take place in the United States.

Is Weathering with you a sad anime?

Weathering With You is definitely more heartfelt than heartbreaking, although there are several tear-jerking moments throughout the film. The penultimate spot, however, goes to the moment when Hina is taken by the sky as a sacrifice to normalize the weather, and Hodoka wakes up to find her missing.

Is your name based on a true story?

While the town of Itomori, one of the film’s settings, is fictional, the film drew inspirations from real-life locations that provided a backdrop for the town. Such locations include the city of Hida in Gifu Prefecture and its library, Hida City Library.

Did they remember each other at the end of your name?

taki and mitsuha will remember the memories of each other after they say their names in the ending scene because when taki was looking for mitsuha in 2016, he went to the place near itomori 3 years after the comet him and read the names of the people who died in the incident, he finds mitsuha in the book and gradually …

Does your name have a sad ending?

To anwser your question simply, yes, they did, the red string of fate which is very important throughout the film pretty much guarantees that they will end up together and get married.

Did Taki and Mitsuha meet?

Mitsuha decided to go to Tokyo to meet Taki. Mitsuha met young Taki on a train, but he didn’t know who she is. Mitsuha went back to Itomori and asked her grandmother to cut her hair. Mitsuha and Taki met, switched back and had a brief conversation.

Why is Kimi no Na wa sad?

Movies like Kimi no Na wa or series like CLANNAD do that to you because they have unrealistic scenarios portayed in a mundane fashion. That mundane presentation triggers this sad, longing feeling.

Table of Contents

- Do Greek words have multiple meanings?

- What does drama mean in Greek?

- What is the Greek name for actor?

- What do you call a Greek play?

- What does hypocrite mean in Greek?

- What words are connected to hypocritical?

- What is the opposite word of hypocrite?

- What is another word for sanctimonious?

- What is the difference between self righteous and sanctimonious?

- What sanctimonious means?

- How do you deal with sanctimonious people?

- What is sanctimonious attitude?

- Who is phlegmatic person?

- Does sanguine mean happy?

- Who is a melancholic person?

- What are the 4 personality types?

- Are Melancholics intelligent?

meleti

Do Greek words have multiple meanings?

Could you please tell me if Koine Greek or just Greek language has a range of meanings for each words, like we have in Arabic language and Hebrew language? Answer: Every language or form of human speech has a range of meanings and usage for its words. Word meanings arise from how the words are commonly used.

What does drama mean in Greek?

The term “drama” comes from a Greek word meaning “action” (Classical Greek: δρᾶμα, drama), which is derived from “I do” (Classical Greek: δράω, drao). The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy.

What is the Greek name for actor?

hypocrite

What do you call a Greek play?

A Greek chorus, or simply chorus (Greek: χορός, translit. chorós), in the context of Ancient Greek tragedy, comedy, satyr plays, and modern works inspired by them, is a homogeneous, non-individualised group of performers, who comment with a collective voice on the dramatic action.

What does hypocrite mean in Greek?

The word hypocrite comes from the Greek word hypokrites — “an actor” or “a stage player.” It literally translates as “an interpreter from underneath” which reflects that ancient Greek actors wore masks and the actor spoke from underneath that mask.

What words are connected to hypocritical?

other words for hypocritical

- deceptive.

- duplicitous.

- insincere.

- sanctimonious.

- self-righteous.

- unnatural.

- affected.

- artificial.

What is the opposite word of hypocrite?

hypocrite. Antonyms: saint, believer, christian, simpleton, dupe, bigot, fanatic, lover of truth. Synonyms: feigner, pretender, dissembler, imposter, cheat, deceitful person.

What is another word for sanctimonious?

In this page you can discover 30 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for sanctimonious, like: self-righteous, condescending, pharisaic, holier-than-thou, pecksniffian, preachy, pietistic, holy, modest, sycophantic and hypocritical.

What is the difference between self righteous and sanctimonious?

As adjectives the difference between sanctimonious and righteous. is that sanctimonious is making a show of being morally better than others, especially hypocritically pious while righteous is free from sin or guilt.

What sanctimonious means?

1 : hypocritically pious or devout a sanctimonious moralist the king’s sanctimonious rebuke— G. B. Shaw. 2 obsolete : possessing sanctity : holy.

How do you deal with sanctimonious people?

Self-righteous people thrive on attention, it’s why they start things or unnecessarily continue things. When confronted by them, don’t give them what they want. You may agree with them, disagree with them, kind of sympathize with them- just don’t show it or say anything. Let your silence and inaction speak for itself.

What is sanctimonious attitude?

Self-righteousness, also called sanctimoniousness, sententiousness and holier-than-thou attitudes is a feeling or display of (usually smug) moral superiority derived from a sense that one’s beliefs, actions, or affiliations are of greater virtue than those of the average person.

Who is phlegmatic person?

The Phlegmatic is the most stable temperament. They are calm, easygoing people who are not plagued with the emotional outbursts, exaggerated feelings, anger, bitterness or unforgiveness as are other temperaments. They are observers who do not get involved nor expend much energy.

Does sanguine mean happy?

sanguine adjective (CHEERFUL) (of someone or someone’s character) positive and hoping for good things: They are less sanguine about the prospects for peace.

Who is a melancholic person?

Melancholic individuals tend to be analytical and detail-oriented, and they are deep thinkers and feelers. They are introverted and try to avoid being singled out in a crowd. A melancholic personality leads to self-reliant individuals who are thoughtful, reserved, and often anxious.

What are the 4 personality types?

A study published in Nature Human Behaviour reveals that there are four personality types — average, reserved, role-model and self-centered — and these findings might change the thinking about personality in general.

Are Melancholics intelligent?

There are so many benefits that come with being melancholic. First, melancholics are analytical, which helps them in living their daily lives. Also, they are very intellectual and brilliant at carrying out tasks.

Go to Introduction || Go to Scriptures

|| Greek Word Studies ||

18 ||

25 ||

26 ||

27 ||

32 ||

37 ||

40 ||

71 ||

93 ||

86 ||

129 ||

165 ||

166 ||

203 ||

225 ||

227 ||

228 ||

230 ||

350 ||

386 ||

435 ||

444 ||

450 ||

458 ||

536 ||

543 ||

544 ||

545 ||

599 ||

601 ||

602 ||

622 ||

652 ||

769 ||

770 ||

907 ||

908 ||

909 ||

932 ||

1067 ||

1074 ||

1228 ||

1242 ||

1342 ||

1343 ||

1344 ||

1453 ||

1588 ||

1656 ||

1680 ||

1785 ||

1849 ||

2222 ||

2288 ||

2347 ||

2378 ||

2518 ||

2632 ||

2837 ||

2889 ||

2919 ||

2920 ||

2923 ||

2936 ||

2937 ||

3056 ||

3338 ||

3340 ||

3341 ||

3376 ||

3466 ||

3498 ||

3551 ||

3554 ||

3561 ||

3677 ||

3686 ||

3701 ||

3705 ||

3709 ||

3798 ||

3904 ||

3952 ||

3957 ||

3962 ||

4059 ||

4061 ||

4100 ||

4102 ||

4103 ||

4151 ||

4152 ||

4202 ||

4203 ||

4204 ||

4205 ||

4309 ||

4335 ||

4336 ||

4404 || 4405 ||

4487 ||

4521 ||

4559 ||

4561 ||

4567 ||

4582 ||

4592 ||

4594 ||

4622 ||

4678 ||

4680 ||

4716 ||

4717 ||

4982 ||

4991 || 4992 ||

5083 ||

5218 ||

5219 ||

5258 ||

5485 ||

5590 ||

#2. GREEK WORD STUDIES

ἐξουσία ‘exousia’ meaning ‘authority’ Strong’s 1849

This bible study uses a Greek Unicode font and is printable.

Hebrew Word Studies Index || Search this website ||

Greek Word Studies Index || Greek Word Definitions Index

- GREEK NEW TESTAMENT

- Introduction 2.1

- #2.1 Scriptures for ἐξουσία ‘exousia’ meaning ‘authority’ Strong’s 1849

Introduction 2.1

This is a word study about the meaning of the Greek word ἐξουσία, ‘exousia’ (Strong’s 1849) meaning ‘authority’.

Other meanings can include power, control, or right.

It gives every verse where the word ‘exousia’ appears in the New Testament. To obtain a true understanding of this word these scriptures

need to be meditated on and notes made of their meaning in different contexts. This requires putting scriptures together where they seem to have a similar meaning,

and then meditating even more. The truth will be revealed by the Holy Spirit, who has been given to guide us into all truth (John 16:13). Wherever this word

exousia appears in the Greek, the translation of it is highlighted with yellow.

In Greek the suffixes and some prepositions are not added to the basic word to enhance the meaning, except for case endings, so the associated

suffix or preposition has not been included in highlighted text. Every blessing be to those who seek the truth of God’s word.

#2.1 Scriptures for ἐξουσία ‘exousia’ meaning ‘authority’ Strong’s 1849

Matthew 7:29 For he taught them as having authority, and not as the scribes.

8:9 For I am a man under authority, having soldiers under me: and I say to this man, Go, and he goes; and to another, Come, and he comes; and to my servant, Do this, and he does it.

9:6 But that you may know that the Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins, (then he says to the sick of the palsy,) Arise, take up your bed, and go to your house.

9:8 But when the multitudes saw it, they marveled, and glorified God, who had given such authority to men.

10:1 And when he had called to him his twelve disciples, he gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to heal all manner of sickness and all manner of disease.

21:23 And when he came into the temple, the chief priests and the elders of the people came to him as he was teaching, and said, By what authority do you do these things? And who gave you this authority?

21:24 And Jesus answered and said to them, I also will ask you one thing, which if you tell me, I in like manner will tell you by what authority I do these things.

21:27 And they answered Jesus, and said, We cannot tell. And he said to them, Neither tell I you by what authority I do these things.

28:18 And Jesus came and spoke to them, saying, All authority is given to me in heaven and on earth.

Mark 1:22 And they were astonished at his doctrine: for he taught them as one who had authority, and not as the scribes.

1:27 And they were all amazed, so that they questioned among themselves, saying, What thing is this? What new doctrine is this? For with authority he commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him.

2:10 But that you may know that the Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins, (he says to the sick of the palsy,)

3:15 And to have authority to heal sicknesses, and to cast out demons:

6:7 And he called to him the twelve, and began to send them out by two and two; and gave them authority over unclean spirits;

11:28 And they say to him, By what authority do you do these things? And who gave you this authority to do these things?

11:29 And Jesus answered and said to them, I will also ask of you one question, and answer me, and I will tell you by what authority I do these things.

11:33 And they answered and said to Jesus, We cannot tell. And Jesus answering says to them, Neither do I tell you by what authority I do these things.

13:34 For the Son of man is as a man taking a far journey, who left his house, and gave authority to his servants, and to every man his work, and commanded the porter to watch.

Luke 4:6 And the Devil said to him, All this authority will I give you, and the glory of them: for that is delivered to me; and to whomever I will I give it.

4:32 And they were astonished at his doctrine: for his word was with authority.

4:36 And they were all amazed, and spoke among themselves, saying, What a word is this! For with authority and power he commands the unclean spirits, and they come out.

5:24 But that you may know that the Son of man has authority upon earth to forgive sins, (he said to the sick of the palsy,) I say to you, Arise, and take up your couch, and go into your house.

7:8 For I also am a man set under authority, having under me soldiers, and I say to one, Go, and he goes; and to another, Come, and he comes; and to my servant, Do this, and he does it.

9:1 Then he called his twelve disciples together, and gave them power and authority over all demons, and to cure diseases.

10:19 Behold, I give to you authority to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you.

12:5 But I will forewarn you whom you shall fear: Fear him, who after he has killed has authority to cast into Gehenna; yes, I say to you, Fear him.

12:11 And when they bring you into the synagogues, and to magistrates, and authorities, take you no thought how or what thing you shall answer, or what you shall say:

19:17 And he said to him, Well, you good servant: because you have been faithful in a very little, you have authority over ten cities.

20:2 And they spoke to him, saying, Tell us, by what authority do you these things? Or who is he who gave you this authority?

20:8 And Jesus said to them, Nor do I tell you by what authority I do these things.

20:20 And they watched him, and sent forth spies, pretending themselves to be righteous, that they might take hold of his words, that so they might deliver him to the power and authority of the governor.

23:7 And as soon as he knew that he belonged to Herod’s jurisdiction, he sent him to Herod, who himself also was at Jerusalem at that time.

John 1:12 But as many as received him, to them he gave authority to become the sons of God, even to those who believe in his name:

5:27 And has given him authority to execute judgment also, because he is the Son of man.

10:18 No man takes it from me, but I lay it down of myself. I have authority to lay it down, and I have authority to take it again. This commandment I have received of my Father.

17:2 As you have given him authority over all flesh, that he should give eternal life to as many as you have given him.

19:10 Then says Pilate to him, Do you not speak to me? Do you not know that I have authority to crucify you, and have authority to release you?

19:11 Jesus answered, You could have no authority at all against me, except it were given you from above: therefore he who delivered me to you has the greater sin.

Acts 1:7 And he said to them, It is not for you to know the times or the seasons, which the Father has put in his own authority.

5:4 While it remained, was it not your own? And after it was sold, was it not in your own authority? Why have you conceived this thing in your heart? You have not lied to men, but to God.

8:19 Saying, Give me also this authority, that on whomever I lay hands, he may receive the Holy Spirit.

9:14 And here he has authority from the chief priests to bind all who call on your name.

26:10 Which thing I also did in Jerusalem: and many of the saints did I shut up in prison, having received authority from the chief priests; and when they were put to death, I gave my voice against them.

26:12 Upon which as I went to Damascus with authority and commission from the chief priests,

26:18 To open their eyes, and to turn them from darkness to light, and from the authority of Satan to God, that they may receive forgiveness of sins, and inheritance among those who are sanctified by faith that is in me.

Romans 9:21 Does the potter not have authority over the clay, of the same lump to make one vessel to honor, and another to dishonor?

13:1 Let every soul be subject to the higher authorities; for there is no authority except from God; and those who are authorities have been appointed by God.

13:2 Whoever therefore resists the authority, resists the ordinance of God: and those who resist shall receive to themselves condemnation.

13:3 For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Will you then not be afraid of the authority? Do that which is good, and you shall have praise of the same:

1 Corinthians 7:37 Nevertheless he who stands steadfast in his heart, having no necessity, but has authority over his own will, and has so decreed in his heart that he will keep his virgin, does well.

8:9 But take heed lest by any means this authority of yours becomes a stumbling-block to those who are weak.

9:4 Do we not have authority to eat and to drink?

9:5 Do we not have authority to lead about a sister, a wife, as well as other apostles, and as the brothers of the Lord, and Kephas?

9:6 Or I only and Barnabas, do we not have authority to forbear working?

9:12 If others are partakers of this authority over you, are not we rather? Nevertheless we have not used this authority; but suffer all things, lest we should hinder the gospel of Christ.

9:18 What is my reward then? That, when I preach the gospel, I may make the gospel of Christ without charge, that I do not abuse my authority in the gospel.

11:10 For this cause ought the woman to have authority on her head because of the angels.

15:24 Then comes the end, when he shall have delivered up the kingdom to God, even the Father; when he shall have put down all rule and all authority and power.

2 Corinthians 10:8 For though I should boast somewhat more of our authority, which the Lord has given us for edification, and not for your destruction, I should not be ashamed:

13:10 Therefore I write these things being absent, lest being present I should use sharpness, according to the authority which the Lord has given me to edification, and not to destruction.

Ephesians 1:21 Far above all principality, and authority, and power, and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this age, but also in that which is to come:

2:2 In which in time past you walked according to the age of this world, according to the prince of the authority of the air, the spirit that now works in the children of disobedience:

3:10 To the intent that now to the principalities and authorities in heavenly places might be known by the church the manifold wisdom of God,

6:12 For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against authorities, against the rulers of the darkness of this age, against spiritual wickedness in heavenly places.

Colossians 1:13 Who has delivered us from the authority of darkness, and has translated us into the kingdom of his dear Son:

1:16 For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are on earth, visible and invisible, whether there are thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or authorities: all things were created by him, and for him:

2:10 And you are complete in him, who is the head of all principality and authority:

2:15 And having plundered principalities and authorities, he made a show of them openly, triumphing over them in it.

2 Thessalonians 3:9 Not because we do not have authority, but to make ourselves an example to you to follow us.

Titus 3:1 Put them in mind to be subject to principalities and authorities, to obey magistrates, to be ready to every good work,

Hebrews 13:10 We have an altar, of which they have no authority to eat who serve the tabernacle.

1 Peter 3:22 Who is gone into heaven, and is on the right hand of God; angels and authorities and powers being made subject to him.

Jude 1:25 To the only wise God our Saviour, be glory and majesty, dominion and authority, both now and for all the ages. Amen.

Revelation 2:26 And he who overcomes, and keeps my works to the end, to him will I give authority over the nations:

6:8 And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hades followed with him. And authority was given to them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.

9:3 And there came out of the smoke locusts upon the earth: and to them was given authority, as the scorpions of the earth have authority.

9:10 And they had tails like scorpions, and there were stings in their tails: and their authority was to hurt men five months.

9:19 For their authority is in their mouth, and in their tails: for their tails were like serpents, and had heads, and with them they do hurt.

11:6 These have authority to shut heaven, that it does not rain in the days of their prophecy: and have authority over waters to turn them to blood, and to strike the earth with all plagues, as often as they will.

12:10 And I heard a loud voice saying in heaven, Now has come salvation, and strength, and the kingdom of our God, and the authority of his Christ: for the accuser of our brothers is cast down, who accused them before our God day and night.

13:2 And the beast which I saw was like a leopard, and his feet were as the feet of a bear, and his mouth as the mouth of a lion: and the dragon gave him his power, and his seat, and great authority.

13:4 And they worshipped the dragon who gave authority to the beast: and they worshipped the beast, saying, Who is like to the beast? Who is able to make war with him?

13:5 And there was given to him a mouth speaking great things and blasphemies; and authority was given to him to continue forty two months.

13:7 And it was given to him to make war with the saints, and to overcome them: and authority was given him over all kindred, and tongues, and nations.

13:12 And he exercises all the authority of the first beast before him, and causes the earth and those who dwell in it to worship the first beast, whose deadly wound was healed.

14:18 And another angel came out from the altar, which had authority over fire; and cried with a loud cry to him who had the sharp sickle, saying, Thrust in your sharp sickle, and gather the clusters of the vine of the earth; for her grapes are fully ripe.

16:9 And men were scorched with great heat, and blasphemed the name of God, who has authority over these plagues: and they did not repent to give him glory.

17:12 And the ten horns which you saw are ten kings, who have received no kingdom as yet; but receive authority as kings one hour with the beast.

17:13 These have one mind, and shall give their authority and strength to the beast.

18:1 And after these things I saw another angel come down from heaven, having great authority; and the earth was lightened with his glory.

20:6 Blessed and holy is he who has part in the first resurrection: on such the second death has no authority, but they shall be priests of God and of Christ, and shall reign with him a thousand years.

22:14 Blessed are those who do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city.

If you have benefited from reading this study, then please tell your friends about this website.

If you have a website of your own, then please consider linking to this website. See the Website Links page.

Please Please copy and paste this word study link into Facebook and Twitter to all your friends who are interested in Greek Word Studies on authority and give it a Google +.

Home Page || Hebrew Word Studies Index ||

Greek Word Studies Index || Greek Word Definitions Index || Bible Studies Index

Top

(Major Revision ~ 06/20/2016)

James Strong

Strong’s Concordance and Dictionary

One thing that many believers do concerning the handling of Greek words is use Strong’s Concordance’s Dictionary to translate Greek words – this is not only a fundamental error, but can lead to devastating conclusions regarding the misunderstanding of many Greek words.

Language Roots

This is because Strong’s dictionary is not specific to any particular word within any particular passage, it is generic based only upon Greek roots, and cannot be used in word studies of any Greek words found in the Greek New Testament.

It is in understanding that the Koiné (“common”) Greek language uses many cognates (see Footnote #1) which in spite of utilizing the same root words, derive diverse meanings based upon the grammar; especially verbs concerning their tense, voice, and mood.

All languages combine words to express diverse meaning, wherein the Greek language abounds in this practice. This is what makes the effort to record a concordance of every book in the Bible so difficult.

As stated in the preface to Strong’s concordance and dictionary, his dictionary is a root dictionary wherein many words are not actually spelled as listed in their root meaning when you look them up in a Greek New Testament.

This difficulty is noted when utilizing an interlinear where the English words are recorded beneath the Greek text, giving the reader the opportunity to see the exact spelling of any specific word used, which a majority of the time is different than found in Strong’s root dictionary. (Please see Endnote #2)

I have used the word root to make the point obvious that this Greek dictionary was never meant to be a specific dictionary concerning precise words and their exact meaning, which is determined within the passage wherein the parsing of the exact word and is noted because of the diverse spelling concerning such tools as prefix and suffix, and the grammatical breakdown of the verbs into their delineation, as well as the case forms, of which there are five; nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, or dative.

If a concordance was assembled, which listed all the variances of all the words to their exact meaning within just the Greek New Testament, it would be hundreds of thousands of pages long because of the diversity of words from their original root meaning to the specific meaning of that word with in a specific passage.

Therefore, a manageable concordance could only be based upon the root words, but as James Strong says himself in his preface, his dictionary was never meant for Word study.

Word study by its very nature must break down passages according to their delineation which is specific to that passage alone, meaning that a concordance would have to list many individual passages, since a majority of words are changed in their spelling from one passage to the next.

The deviations may be slight in most cases, but the ramifications can be enormous.

Example ~ Judgment

Because of the diversity of combining words and the slightly different spellings wherein there may be over a half a dozen different Greek words, such as the word “judge,” which is translated into only one English word, but has a range of meaning from judging unto condemnation, which is condemned in the Bible and only allowed for the creator God to do, as compared to discernment like when Paul chides the Corinthians for not being able to exercise proper biblical judgment.

How often do we hear Christians misquote Scriptures concerning judging, advising others to NOT judge them, even as they openly sin, which is the opposite that is taught in God’s Word?

For example, the first chapter of Romans is inaccurately used to tell Christians not to judge, when the immediate biblical context is speaking about unbelievers judging others, not believers.

There are more warnings to exercise proper biblical judgment by far than warnings not to judge.

In many passages the subject cautions against judging regarding the manner or mindset of judging, or the spiritual state of the individual making the observation. We are NOT told to NOT point out a “speck in our brothers eye,” but to make sure that we deal with the beam in our own eye first.

Discernment is a requirement for human existence, but even more so for a born-again believer. It’s not merely knowing the difference between good and evil, it is also avoiding the rationalization that moves us from good to evil via shades of grey. Many times the enemy of the good is not evil, but second best, when it takes pre-eminence over what is best.

The Reason for a Lack of Discernment

Yet, because we have ONLY one English word for “judge,” as compared to the half a dozen in the Greek New Testament, the word “judgement” as used in the English translations is misused and misunderstood; and now we have a whole generation of believers that misunderstand God’s command for us to discern the world around us to the extent that now believers live milquetoast lives because of their inability to exercise godly judgment as seen in Hebrews 5:11-14, where the writer of the book of Hebrews connects the fact that believers cannot indulge in the meat of the word of God because they refused to exercise proper biblical judgment over good and evil, and therefore can only stand the milk of the word.

King James Translation (KJV)

“Of whom we have many things to say, and hard to be uttered, seeing ye are dull of hearing. For when for the time ye ought to be teachers, ye have need that one teach you again which be the first principles of the oracles of God; and are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat. For every one that useth milk is unskilful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil.” (Hebrews 5:11-14 ~ KJV)

Literal Translation of the Holy Bible (LITV)

“Concerning whom we have much discourse, and hard to interpret, or to speak, since you have come to be dull in the hearings. For indeed because of the time you are due to be teachers, yet you need to have someone to teach you again the rudiments of the beginning of the Words of God, and you came to be having need of milk, and not of solid food; for everyone partaking of milk is without experience in the Word of Righteousness, for he is an infant. But solid food is for those full grown, having exercised the faculties through habit, for distinction of both good and bad.” (Hebrews 5:11-14 ~ Literal Translation of the Holy Bible [LITV], By: Jay P. Green, Sr., who only uses Textus Receptus or Majority Text.)

Lexham English Bible (LEB)

Advanced Teaching Hindered by Immaturity

“Concerning this [a] we have much to say and it is difficult to explain [b], since you have become sluggish in hearing. For indeed, although you [c] ought to be teachers by this time [d], you have need of someone to teach you again the beginning elements of the oracles of God, and you have need of [e] milk, not [f] solid food. For everyone who partakes of milk is unacquainted with the message of righteousness, because he is an infant. But solid food is for the mature, who because of practice have trained their faculties for the distinguishing of both good and evil.” (Hebrews 5:11-14 ~ Lexham English Bible [LEB], By: Logos Bible Software)

Footnotes:

a: Hebrews 5:11 Literally “which”

b: Hebrews 5:11 Literally “great for us the message and hard to explain to say”

c: Hebrews 5:12 Here “although” is supplied as a component of the participle (“ought”) which is understood as concessive”

d: Hebrews 5:12 Literally “because of the time”

e: Hebrews 5:12 Literally “you are having need of”

f: Hebrews 5:12 Some manuscripts have “and not”

This great misunderstanding has created more false doctrine in churches because we have used root dictionaries to define words within a passage, which do not give us the exact meaning of God’s will concerning that word as seen in Greek or Hebrew word studies.

Ministers Using Strong’s Dictionary

I cannot tell you of how many times I have heard ministers using definitions of Greek words from Strong’s dictionary, and doing so incorrectly as opposed to actually doing the hard work of parsing the Greek and learning how to do so correctly.

Strong’s is never meant to be preached from. It is meant to locate passages in the Bible if you know only one word in that passage, but even many of the current hybrid Strong’s Greek dictionaries still display the same problem with presenting only root words.

Ministers should be using only Greek New Testaments, or excellent Word Studies that go into great depth, and even Vines doesn’t hold up to this standard many times.

Strong’s contribution, which utilized over a 100 contributors is a fantastic tool in locating passages, especially understanding when it was created over 100 years ago before the use of computers.

And the dictionaries in the back are only meant to be a general guide, which he notes in the preface, that no one ever reads; explaining that it is a root dictionary.

James Strong was NOT a Linguist that understood Biblical Languages

Though James Strong was a professor, he was NOT a professor in Greek or Hebrew, and was not fluent in these languages, he received nothing but a summary introduction education in these languages. And his credentials as a Doctorate of theology are only honorary; even though he became a professor of Biblical Literature and Exegetical Theology at Troy University and Drew theological seminary in New York.

It appears that his highest earned degree was a Masters (Not in biblical languages, but generic in theology), wherein he was the valedictorian of his graduating class. He was given (Not earned) three honors doctorates (Dr. of Divinity, Dr. of sacred theology, and Dr. of laws) degrees (not based upon academia, studies; meaning they were NOT earned), because of his reputation as a professor and his writings; none concerning biblical language.

SIDENOTE:

There are a lot of ministers that place Dr. before their name when they have been given Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) degrees, not earned degrees; meaning they are fake!

Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) degrees in England are earned degrees, which is an advanced doctorate degree rarely given. In America, this is an honorary degree given usually by a religious organization or institution, but is not an earned degree. Individuals who put Dr. in front of their name are committing a fraud in that people will believe that they earned a doctorate degree, when they have not, it was merely GIVEN to them.

When a church, denomination, or religious organization makes a minister a Bishop they will commonly give them a Doctorate of Divinity (This is starting to be seen in many churches, where they love to address their pastor as doctor… . Where many honorary degrees abound, as well as the use of the term “Bishop,” used for pastors; all done as opposed to Matthew 23:1-12.) in recognition of their position, but never earned. How we love titles.

No record exists that James Strong majored in biblical languages, or received a degree in this specialized training concerning linguistics for either Hebrew or Greek.

PERSONAL NOTE:

I made the mistake of utilizing Strong’s for many years while preaching. It is this kind of mistake that leads to the teaching that man is instrumental in his own salvation when dealing with Scripture such as Philippians 2:12, which states:

“Wherefore, my beloved, as ye have always obeyed, not as in my presence only, but now much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling.” (KJV)

Without understanding the original Greek language I along with many others believed that I had to add to my salvation in some capacity, to “work it out.”

Yet now that I understand the Greek, I understand the difference between the English phrasing of this word in the Greek. In the Greek it means to come to understand what has been done, it would be synonymous to a teacher working out the formula of a math problem, doing the work himself, then telling the child to work out how he did it, and how he came to his conclusion on their own.

The purpose would be to understand the price that was paid for the conclusion. This is why the passage states that concerning our salvation we should do so with “fear and trembling.” Understanding that to purchase our salvation it cost the most expensive fee in all of existence, the blood of a sinless peer being, the blood of God’s Son, God Himself Jesus Christ to pay the price for our sins.

We did nothing whatsoever to deserve salvation, we are not even saved by faith. We are saved by grace, yet faith is a necessary vehicle to access that grace, if you don’t receive it it’s because you don’t believe it, yet faith is not a condition of receiving, it is the method of receiving.

Salvation is based solely on the work of Jesus Christ on the cross 2000 years ago, it is this that Paul tells us to work out and understand so that we comprehend the seriousness of sin. Sin is so devastating that the only thing that could balance the scales is complete righteousness, the complete righteousness of Jesus Christ taking our place in pain for our sins, this always brings me to a place of fear in understanding the devastation of sin and a complete and utter respect of how far God was willing to go to pay for that sin.

I did not learn this lesson until I light understood the Greek grammar of these words.

If anything makes this ministry different than others, it is because I am obsessed with the Greek grammar of the word of God, the very language that God chose to convey this most precious message to mankind, the gospel of Jesus Christ, wherein God’s only begotten son, the incarnate deity and God who came down to pay for our sins. Generically, the sixth thing that Jesus said from the cross, generically is interpreted, “it is finished.” Yet specifically the Greek means “paid in full,” or recompense and full. Many would ask the difference in these two understandings.

I’ve heard many people that are not believers say that Jesus was a good teacher, and with this mindset could say that when he said it is finished he was referring to his teaching. Or perhaps he was referring to giving up his life.

Jesus teaching is important but it is not the primary reason for his incarnation, because without his death his teaching would do us no good, we might become more moral people but we would still go to hell.

When Jesus said paid in full he was referring to the gospel, the good news as defined in 1st Corinthians 15:1-4, which states:

“Moreover, brethren, I declare unto you the gospel which I preached unto you, which also ye have received, and wherein ye stand; By which also ye are saved, if ye keep in memory what I preached unto you, unless ye have believed in vain. For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures; And that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures” (KJV)

The Gospel is not the teachings of Jesus.

The Gospel is the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ who did so to purchase our salvation by paying for our sins, bracketed between the comment “according to the Scriptures,” indicating that these three components of the gospel our primary and taught throughout the old and New Testament. It is understanding the Greek, that over two decades ago I came to understand, Jesus, more than for gave me, He “paid my sins in full.”

There is nothing that I can add to my own salvation he did 100% of it, it is simply my pleasure to accept it by believing it, and thus live a life of faith and trust in him, never taking for granted the power of sin, understanding how much he paid to purchase me because of it.

This is what knowing the Greek grammar means to an individual who wishes to teach God’s word, not generically regurgitating what a root dictionary states.

Taken original Greek Preface, Written by Strong himself

Strong’s Preface to the Dictionary

Hebrew Preface:

“This work, although prepared as a companion to the exhaustive concordance, to which it is specifically adapted, is here paged and printed so that it can be bound separately, in the belief that a brief and simple dictionary of the biblical Hebrew and Chaldee will be useful to students and others, who do not care at all times to consult a more precise and elaborate lexicon; and it will be particularly serviceable to many who are unable to turn conveniently and rapidly, amid the perplexities and details of foreign characters with which the pages of Genesis and Fϋrst bristol, to the fundamental and essential points of information that they are seeking. Even scholars will find here, not only all of a strictly verbal character which they most frequently want in ordinary consultation of a lexicon, but numerous original suggestions, relations, and distinction, commonly made and clearly put, which are not unworthy of their attention, especially in the affinities of roots and the classification of meanings… The design of the volume, being purely lexical, does not include grammatical, archaeological, or exegetical details, which would have swelled its size and encumbered its plan.

Taken original Greek Preface, Written by Strong himself:

“This work is entirely similar an origin, method, and design, to the authors Hebrew dictionary, and may be employed separately, for a corresponding purpose and with a like result, namely, to be serviceable to many who have not the wish or the ability to use a more capricious lexicon of the Greek New Testament. In this case also even scholars will find many suggestions and explanations not unworthy of their attention”

As has been stated in his defense, James Strong never contributed original research. The term original research has to do with defining words terms and insights as compared to restating passages as is done in a concordance. A concordance is a guide that list individual words to be found in the Bible, by its very nature it is not an original research work, utilizing rules of literature or science in defining or presenting hypothesis or conclusions. What the writers did was categorize English words in the English translation of the Old and New Testaments alphabetically as a guide to their location within these volumes – their purpose was never to define words, or prescribed two or teach doctrine or theology, a concordance is a book of lists.

Strong’s Concordance is a fantastic tool. But it must be used as it was meant, as a concordance, not a Greek word study

So Who Do We Use for Greek Word Study Guides

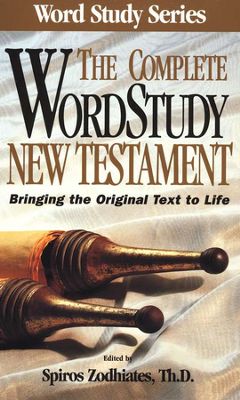

One of the best layman Greek Word Studies, meaning that the author defines the words without explaining the delineation of the verb, such as: the tense, mood, voice, gender, and number; or the case of the noun or other grammatical nuances; is found in The Complete Word Study New Testament along with the other dictionaries and parallel Bibles within this series.

Better Yet

However, as good as utilizing Greek word studies can be, this still only displays a partial understanding of any specific word without going into the details of the grammar itself.

The next step in gaining greater understanding of Greek words wherein the student of the Bible digs even deeper into the language is in regards to parsing the delineations as stated above (The verb, such as: the tense, mood, voice, gender, and number; or the case of the noun or other grammatical nuances;). This is the level that the teacher of God’s word should be at in order to thoroughly equip (“All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: That the man of God may be perfect, throughly furnished unto all good works.” (2 Timothy 3:16-17 ~ KJV), the saints of God regarding the whole counsel of God concerning His Word (“For I have not shunned to declare unto you all the counsel of God. Take heed therefore unto yourselves, and to all the flock, over the which the Holy Ghost hath made you overseers, to feed the church of God, which he hath purchased with his own blood.” Acts 20:27-28 ~ KJV). In order to attempt this please email me and I will suggest further tools for greater examination at this level. The final step in attempting to master the Greek New Testament language and grammar is to become completely fluent in the written and spoken word of classical and Koiné Greek language

The Complete Word Study New Testament

The excellent Greek translation work done by Spiros Zodhiates TH. D; is by far a great tool for the biblical layman.

Spiros earned his doctorate degree (achieved) in University after many years of study in the Greek language.

He is fluent in writing and speaking in Classical and Koiné Greek, and also has spoken Greek all his life as a native of Greece.

He translates words based upon the specific Scripture, where the differences of how a word is translated is based upon the grammar of the verbs in that particular usage in the context wherein each usage of the word can be completely diverse from another.

This can be verified by a Greek New Testament Bible (I reference only the Textus Receptus Greek New Testament – See Endnote #3).

This is why the diligent student of Greek never utilizes Strong’s Concordance’s Dictionary for translation work because it only utilizes generic – root words without their specific meaning as found only in the text is used.

Strong’s was never meant to be an exhaustive Greek Dictionary, it was designed to give a general reference to the meaning of words utilized within his concordance, whose main purpose is to locate words in the Bible using an identification system which is common in most Greek translation work.

(739)

“Textus Receptus wiki” website regarding Strong’s Concordance:

Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, generally known as Strong’s Concordance, is a concordance of the King James Bible (KJV) that was constructed under the direction of Dr. James Strong (1822–1894) and first published in 1890. Dr. Strong was Professor of exegetical theology at Drew Theological Seminary at the time. It is an exhaustive cross-reference of every word in the KJV back to the word in the original text.

Unlike other Biblical reference books, the purpose of Strong’s Concordance is not to provide content or commentary about the Bible, but to provide an index to the Bible. This allows the reader to find words where they appear in the Bible. This index allows a student of the Bible to re-find a phrase or passage previously studied or to compare how the same topic is discussed in different parts of the Bible.

Strong’s Concordance includes:

The 8674 Hebrew root words used in the Old Testament. (Example: 582)

The 5624 Greek root words used in the New Testament. (Example: 3056)

James Strong did not construct Strong’s Concordance by himself; it was constructed with the effort of more than a hundred colleagues. It has become the most widely used concordance for the King James Bible.

Each original-language word is given an entry number in the dictionary of those original language words listed in the back of the concordance. These have become known as the “Strong’s numbers”. The main concordance lists each word that appears in the KJV Bible in alphabetical order with each verse in which it appears listed in order of its appearance in the Bible, with a snippet of the surrounding text (including the word in italics). Appearing to the right of scripture reference is the Strong’s number. This allows the user of the concordance to look up the meaning of the original language word in the associated dictionary in the back, thereby showing how the original language word was translated into the English word in the KJV Bible.

New editions of Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible are still in print (in 2007). Additionally, other authors have used Strong’s numbers in concordances of other Bible translations, such as the New International Version and American Standard Version. These are often also referred to as Strong’s Concordances.

Although the Greek words in Strong’s Concordance are numbered 1–5624, the numbers 2717 and 3203–3302 are unassigned due to “changes in the enumeration while in progress”. Not every distinct word is assigned a number, but only the root words. For example, αγαπησεις is assigned the same number as αγαπατε — both are listed as 25 “αγαπαω”.

Strong’s Concordance is not a translation of the Bible nor is it intended as a translation tool. The use of Strong’s numbers is not a substitute for professional translation of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into English by those with formal training in ancient languages and the literature of the cultures in which the Bible was written.

Since Strong’s Concordance identifies the original words in Hebrew and Greek, Strong’s Numbers are sometimes misinterpreted by those without adequate training to change the Bible from its accurate meaning simply by taking the words out of cultural context.

The use of Strong’s numbers does not consider figures of speech, metaphors, idioms, common phrases, cultural references, references to historical events, or alternate meanings used by those of the time period to express their thoughts in their own language at the time.

As such, professionals and amateurs alike must consult a number of contextual tools to reconstruct these cultural backgrounds.

Many scholarly Greek and Hebrew Lexicons (e.g., Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew Lexicon, Thayer’s Greek Dictionary, and Vine’s Bible Dictionary) also use Strong’s numbers for cross-referencing, encouraging hermeneutical approaches to study.

(http://textus-receptus.com/wiki/Strong’s_Concordance)

Brent

Endnote:

1. Cognates

“In linguistics, cognates are words that have a common etymological origin.[1] In etymology, the cognate category excludes doublets and loan words.[citation needed] The word cognate derives from the Latin noun cognatus, which means “blood relative”.[2]

Cognates do not need to have the same meaning, which may have changed as the languages developed separately. For example, consider English starve and Dutch sterven or Germansterben (“to die”); these three words all derive from the same Proto-Germanic root, *sterbaną (“die”). English dish and German Tisch (“table”), with their flat surfaces, both come from Latindiscus, but it would be a mistake to identify their later meanings as the same. Discus is from Greek δίσκος (from the verb δικεῖν “to throw”). A later and separate English reflex of discus, probably through medieval Latin desca, is desk (see OED s.v. desk).

Cognates also do not need to have obviously similar forms, e.g. English father, French père, and Armenian հայր (hayr) all descend directly from Proto-Indo-European *ph₂tḗr.

- Crystal, David, ed. (2011). “cognate”. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (6th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4443-5675-5. OCLC 899159900. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

Jump up^”cognate”, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed.: “Latin cognātus: co-, co- +gnātus, born, past participle of nāscī, to be born.” Other definitions of the English word include “[r]elated by blood; having a common ancestor” and “[r]elated or analogous in nature, character, or function”.Crystal, David, ed. (2011). “cognate”. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (6th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4443-5675-5. OCLC 899159900. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Jump up^”cognate”, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed.: “Latin cognātus: co-, co- +gnātus, born, past participle of nāscī, to be born.” Other definitions of the English word include “[r]elated by blood; having a common ancestor” and “[r]elated or analogous in nature, character, or function“.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognate

(From Brent: To the purist in linguistics who would suggest that quoting Wikipedia is unprofessional, perhaps. But when what is stated is correct, Wikipedia can present definitions much more concise and accurately than textbooks or journals with simple words that are much easier for us layman to understand. Remember Einstein’s words: “Everything should be as simple as it can be, but not simpler” – Albert Einstein “A Scientist’s Defense of Art and Knowledge – of Lightness, Completeness and Accuracy.”)

2. Strong’s Concordance & Dictionary – Root Words

“Although the Greek words in Strong’s Concordance are numbered 1–5624 editions of Strong’s, the numbers 2717 and 3203–3302 are unassigned due to “changes in the enumeration while in progress”. Not every distinct word is assigned a number, but only the root words. For example, αγαπησεις is assigned the same number as αγαπατε – both are listed as Greek word #25 in Strong’s “αγαπαω”.

Strong’s Concordance is not a translation of the Bible nor is it intended as a translation tool. The use of Strong’s numbers is not a substitute for professional translation of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into English by those with formal training in ancient languages and the literature of the cultures in which the Bible was written.

Since Strong’s Concordance identifies the original words in Hebrew and Greek, Strong’s numbers are sometimes misinterpreted by those without adequate training to change the Bible from its accurate meaning simply by taking the words out of cultural context. The use of Strong’s numbers does not consider figures of speech, metaphors, idioms, common phrases, cultural references, references to historical events, or alternate meanings used by those of the time period to express their thoughts in their own language at the time. As such, professionals and amateurs alike must consult a number of contextual tools to reconstruct these cultural backgrounds. Many scholarly Greek and Hebrew Lexicons (e.g., Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew Lexicon, Thayer’s Greek Dictionary, and Vine’s Bible Dictionary) also use Strong’s numbers for cross-referencing, encouraging hermeneutical approaches to study.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strong%27s_Concordance

3. Textus Receptus – clickable Links

I only use the Textus Receptus (Theopedia.com) for Greek word study meanings, there are too many thousands of deviations in the newer (Alexandrian type text) translations which do harm to the original meaning. The Textus Receptus, utilized for the King James Translation has known English translation errors that are understood, corrected, and do no fundamental damage to any doctrine, unlike the newer translations.

The New King James is not based upon the Textus Receptus (Wikipedia.com). Read the introduction to the New King James Bible, it is written in the spirit of the King James Bible (Textus Receptus), but it is based upon Alexandrian codices, which many translators, including myself feel are corrupted when it is compared with the Textus Receptus (Chick.com), [See Footnote #4 below].

Textual Criticism is a complicated subject, where there are individuals which abuse forms of translation styles and formats, commonly referred to as Higher Criticism (newworldencyclopedia.org), which was created 200 years ago. I am a follower of the teachers of the last few hundred years regarding Lower Criticism, which has been the standard of literature research and biblical criticism for the last 2000 years, beginning in the early writings of the second century and utilized in Antioch as the first Christian center of education regarding the gospel, under the leading of Lucian of Antioch (Britannica.com) [though vilified and belittled by the followers of Higher Criticism], who utilized those texts which were later made up the Textus Receptus. For over 1300 years these documents had been used until they were codified in the authorized text.

Higher Criticism teaches that many of the books of the Bible were NOT written by the stated authors, and are not credible as an errant, such as the Deutero-Isaiah theory, or the Documentary Hypothesis of the Pentateuch, also known as the JEDP Theory. Almost all of the newer critics that follow Higher Criticism (GotQuestions.com) do not believe in the complete inerrancy of the Bible, nor many believe in the inspiration of the holy writ as well.

On the other side of the issue are those who referred to themselves as King James only purist who even go so far as to state that the English translation of the Textus Receptus, the King James is the only inspired word of God. They go so far as to even indicate that the Textus Receptus and other original Greek language New Testaments are corrupted, while the translated into English version of the King James is pure and without any translational errors, which is quite ridiculous in itself.

There are many of us that believe that the Textus Receptus may be the best Koiné Greek copies that we have, yet also value the other Byzantine texts as well, referred to as the Majority Text.

Textual Criticism, in the form of Higher Criticism is taught by almost all Christian schools of higher education, to their own shame.

4. Textual Criticism

A. Lower Criticism

I thought the following short response by Chase was good

How We Got the Bible: The Text of the New Testament

In chapter 8 of the book, Lightfoot [Biblical scholar and theologian R. H. Lightfoot (1883–1953), input by Brent] discusses textual criticism. What it is, a few of its basic rules, and the types of mistakes made by ancient scribes.

There are two types of textual criticism. Higher criticism, which studies authorship, dating, and historical value of Biblical documents, and lower criticism, which studies “the available evidence to recover the exact words of the author’s original composition.” Lower criticism is the focus of this chapter.

Lighfoot then describes the two types of scribal errors:

1. Unintentional errors: Mistaking one word for another or confusing words of similar sound, the omission of a word because it appears at a corresponding point several lines above or below in the manuscript, or explanatory notes in the margin of the manuscript somehow ending up as part of the main text are some examples.

2. Intentional errors: Lightfoot writes, “We ought not think these insertions were made by dishonest scribes who simply wanted to tamper with the text.” The majority of the time, these additions were attempts by the scribes to “correct” the text or bring about a better understanding of it.

Three basic rules of lower criticism are as follows:

1. Most of the time the more difficult reading is to be preferred. This is because scribes usually sought to simplify the text when copying.

2. The quality of witnesses is more important the the quantity. For example, if thousands of manuscripts support a certain reading, but they are of late date and contradict the early unicals, than this reading should not be accepted.

3. When studying parallel texts such as the Gospels, different readings are to be preferred. The Gospels all present Jesus as the Son of God, however, each individual author had descriptions of him and his sayings which used different words. These differences were usually, intentionally or unintentionally, harmonized by scribes.

Lightfoot ends this chapter by stating, “Because textual criticism is a sound science, our text is secure and the textual foundation of our faith remains unshakable.”

Stand firm in Christ, Chase

http://truthbomb.blogspot.com/2014/01/how-we-got-bible-text-of-new-testament.html

The following is a pro-stance on Higher Criticism

B. Rules of Higher Textual Criticism

When the manuscripts differ, how do scholars decide which words are the original ones? There is more to it than simply choosing the readings of the oldest available manuscripts. Here are three historically important sets of rules published by some influential scholars of textual criticism: Bengel, Griesbach, and Hort.

Critical Rules of Johann Albrecht Bengel

In his essay Prodromus Novi Testamenti recte cauteque ordinandi [Forerunner of a New Testament to be settled rightly and carefully], (Denkendorf, 1725), Johann Albrecht Bengel, a Lutheran schoolmaster, published a prospectus for an edition of the Greek Testament which he had already begun to prepare (published in 1734).

In it he outlines his text-critical principles, which included a novel classification of manuscripts into two primitive groups: the Asiatic and the African. The first group he supposed to be of Byzantine origin, and to it belonged the majority of modern manuscripts and the Syriac version; the second, of Egyptian provenance, was represented by Codex Alexandrinus and the manuscripts of the early Latin and Coptic versions. In this work Bengel also set forth a very influential rule of criticism: a preference for harder readings. This rule he expressed in four pregnant words:

proclivi scriptioni praestat ardua. “before the easy reading, stands the difficult.”

The “Monita” of Bengel

In Bengel’s Preface to his Gnomon Novi Testamenti (Tubingen, 1742) he includes an enumerated list of 27 “suggestions” (Monita) which may be taken as a summary of his critical principles. The following extract of these is taken from pages 13 through 17 of Fausset’s translation:

1. By far the more numerous portions of the Sacred Text (thanks be to God) labour under no variety of reading deserving notice.

- These portions contain the whole scheme of salvation, and establish every particular of it by every test of truth.

- Every various reading ought and may be referred to these portions, and decided by them as by a normal standard.

- The text and various readings of the New Testament are found in manuscripts and in books printed from manuscripts, whether Greek, Latin, Graeco-Latin, Syriac, etc., Latinizing Greek, or other languages, the clear quotations of Irenaeus, etc., according as Divine Providence dispenses its bounty to each generation. We include all these under the title of Codices, which has sometimes as comprehensive a signification.

- These codices, however, have been diffused through churches of all ages and countries, and approach so near to the original autographs, that, when taken together, in all the multitude of their varieties, they exhibit the genuine text.

- No conjecture is ever on any consideration to be listened to. It is safer to bracket any portion of the text, which may haply to appear to labour under inextricable difficulties.

- All the codices taken together, should form the normal standard, by which to decide in the case of each taken seperately.

- The Greek codices, which posses an antiquity so high, that it surpasses even the very variety of reading, are very few in number: the rest are very numerous.

- Although versions and fathers are of little authority where they differ from the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, yet, where the Greek mauscripts of the New Testament differ from each other, those have the greatest authority, with which versions and fathers agree.

- The text of the Latin Vulgate, where it is supported by the consent of the Latin fathers, or even of other competent witnesses, deserves the utmost consideration, on account of its singular antiquity.

- The number of witnesses who support each reading of every passage ought to be carefully examined: and to that end, in so doing, we should separate those codices which contain only the Gospels, from those which contain the Acts and the Epistles, with or without the Apocalypse, or those which contain that book alone; those which are entire, from those which have been mutilated; those which have been collated for the Stephanic edition, from those which have been collated for the Complutensian, or the Elzevirian, or any obscure edition; those which are known to have been carefully collated, as, for intance, the Alexandrine, from those which are not known to have been carefully collated, or which are known to have been carelessly collated, as for instance the Vatican manuscript, which otherwise would be almost without an equal.

- And so, in fine, more witnesses are to be preferred to fewer; and, which is more important, witnesses who differ in country, age, and language, are to be preferred to those who are closely connected with each other; and, which is most important of all, ancient witnesses are to be preferred to modern ones. For, since the original autographs (and they were written in Greek) can alone claim to be the well-spring, the amount of authority due to codices drawn from primitive sources, Latin, Greek, etc., depends upon their nearness to that fountain-head.

- A Reading, which does not allure by too great facility, but shines with its own native dignity of truth, is always to be preferred to those which may fairly be supposed to owe their origin to either the carelessness or the injudicious care of copyists.

- Thus, a corrupted text is often betrayed by alliteration, parallelism, or the convenience of an Ecclesiastical Lection, especially at the begining or conclusion of it; from the occurence of the same words, we are led to suspect an omission; from too great facility, a gloss. Where the passage labours under a manifold variety of readings, the middle reading is the best.

- There are, therefore, five principal criteria, by which to determine a disputed text. The antiquity of the witnesses, the diversity of their extraction, and their multitude; the apparent origin of the corrupt reading, and the native colour of the genuine one.

- When these criteria all concur, no doubt can exist, except in the mind of a sceptic.

- When, however, it happens that some of these criteria may be adduced in favour of one reading, and some in favour of another, the critic may be drawn sometimes in this, sometimes in that direction; or, even should he decide, others may be less ready to submit to his decision. When one man excels another in powers of vision, whether bodily or mental, discussion is vain. In such a case, one man can neither obtrude on another his own conviction, nor destroy the conviction of another; unless, indeed, the original autograph Scriptures should ever come to light.”

Following this are ten more paragraphs, numbered 18 through 27, which do not pertain to the evaluation of various readings, but instead contain sundry remarks relative to the design and use of his critical edition. The seventeen given above may therefore be taken as Bengel’s formally stated canons of criticism.

Griesbach’s Fifteen Rules

In the Introduction to his second edition of the Greek New Testament (Halle, 1796) Griesbach set forth the following list of critical rules, by which the intrinsic probabilities may be weighed for various readings of the manuscripts. Rules for the prior evaluation of documentary evidence, such as the ones formulated by Bengel, are implicit in Griesbach’s theory of the manuscript tradition, and so they are not taken up here. What follows is a translation of Griesbach’s Latin as it was reprinted by Alford in the Introduction of his Greek Testament (London, 1849. Moody reprint, page 81).

- The shorter reading, if not wholly lacking the support of old and weighty witnesses, is to be preferred over the more verbose. For scribes were much more prone to add than to omit. They hardly ever leave out anything on purpose, but they added much. It is true indeed that some things fell out by accident; but likewise not a few things, allowed in by the scribes through errors of the eye, ear, memory, imagination, and judgment, have been added to the text. The shorter reading, even if by the support of the witnesses it may be second best, is especially preferable– (a) if at the same time it is harder, more obscure, ambiguous, involves an ellipsis, reflects Hebrew idiom, or is ungrammatical; (b) if the same thing is read expressed with different phrases in different manuscripts; (c) if the order of words is inconsistent and unstable; (d) at the beginning of a section; (e) if the fuller reading gives the impression of incorporating a definition or interpretation, or verbally conforms to parallel passages, or seems to have come in from lectionaries.

But on the contrary we should set the fuller reading before the shorter (unless the latter is seen in many notable witnesses) — (a) if a “similarity of ending” might have provided an opportunity for an omission; (b) if that which was omitted could to the scribe have seemed obscure, harsh, superfluous, unusual, paradoxical, offensive to pious ears, erroneous, or opposed to parallel passages; (c) if that which is absent could be absent without harm to the sense or structure of the words, as for example prepositions which may be called incidental, especially brief ones, and so forth, the lack of which would not easily be noticed by a scribe in reading again what he had written; (d) if the shorter reading is by nature less characteristic of the style or outlook of the author; (e) if it wholly lacks sense; (f) if it is probable that it has crept in from parallel passages or from the lectionaries.

- The more difficult and more obscure reading is preferable to that in which everything is so plain and free of problems that every scribe is easily able to understand it. Because of their obscurity and difficulty chiefly unlearned scribes were vexed by those readings– (a) the sense of which cannot be easily perceived without a thorough acquaintance with Greek idiom, Hebraisms, history, archeology, and so forth; (b) in which the thought is obstructed by various kinds of difficulties entering in, e.g., by reason of the diction, or the connection of the dependent members of a discourse being loose, or the sinews of an argument, being far extended from the beginning to the conclusion of its thesis, seeming to be cut.

- The harsher reading is preferable to that which instead flows pleasantly and smoothly in style. A harsher reading is one that involves an ellipsis, reflects Hebrew idiom, is ungrammatical, repugnant to customary Greek usage, or offensive to the ears.

- The more unusual reading is preferable to that which constitutes nothing unusual. Therefore rare words, or those at least in meaning, rare usages, phrases and verbal constuctions less in use than the trite ones, should be preferred over the more common. Surely the scribes seized eagerly on the more customary instead of the more exquisite, and for the latter they were accustomed to substitute definitions and explanations (especially if such were already provided in the margin or in parallel passages).

- Expressions less emphatic, unless the context and goal of the author demand emphasis, approach closer to the genuine text than discrepant readings in which there is, or appears to be, a greater vigor. For polished scribes, like commentators, love and seek out emphases.

- The reading that, in comparison with others, produces a sense fitted to the support of piety (especially monastic) is suspect.

- Preferable to others is the reading for which the meaning is apparently quite false, but which in fact, after thorough examination, is discovered to be true.

- Among many readings in one place, that reading is rightly considered suspect that manifestly gives the dogmas of the orthodox better than the others. When even today many unreasonable books, I would not say all, are scratched out by monks and other men devoted to the Catholic party, it is not credible that any convenient readings of the manuscripts from which everyone copied would be neglected which seemed either to confirm splendidly some Catholic dogma or forcefully to destroy a heresy. For we know that nearly all readings, even those manifestly false, were defended on the condition that they were agreeable to the orthodox, and then from the beginning of the third century these were tenaciously protected and diligently propagated, while other readings in the same place, which gave no protection to ecclesiastical dogmas, were rashly attributed to treacherous heretics.

- With scribes there may be a tendency to repeat words and sentences in different places having identical terminations, either repeating what they had lately written or anticipating what was soon to be written, the eyes running ahead of the pen. Readings arising from such easily explained tricks of symmetry are of no value.

- Others to be led into error by similar enticements are those scribes who, before they begin to write a sentence had already read the whole, or who while writing look with a flitting eye into the original set before them, and often wrongly take a syllable or word from the preceding or following writing, thus producing new readings. If it happens that two neighbouring words begin with the same syllable or letter, an occurance by no means rare, then it may be that the first is simply ommitted or the second is accidentally passed over, of which the former is especially likely. One can scarcely avoid mental errors such as these, any little book of few words to be copied giving trouble, unless one applies the whole mind to the business; but few scribes seem to have done it. Readings therefore which have flowed from this source of errors, even though ancient and so afterwards spread among very many manuscripts, are rightly rejected, especially if manuscripts otherwise related are found to be pure of these contagious blemishes.

- Among many in the same place, that reading is preferable which falls midway between the others, that is, the one which in a manner of speaking holds together the threads so that, if this one is admitted as the primitive one, it easily appears on what account, or rather, by what descent of errors, all the other readings have sprung forth from it.

- Readings may be rejected which appear to incorporate a definition or an interpretation, alterations of which kind the discriminating critical sense will detect with no trouble

- Readings brought into the text from commentaries of the Fathers or ancient marginal annotations are to be rejected, when the great majority of critics explain them thus. (“He proceeds at some length to caution against the promiscuous assumption of such corruptions in the earlier codices and versions from such sources.” – Alford)

- We reject readings appearing first in lectionaries, which were added most often to the beginning of the portions to be read in the church service, or sometimes at the end or even in the middle for the sake of contextual clarity, and which were to be added in a public reading of the series, [the portions of which were] so divided or transposed that, separated from that which preceeds or follows, there seemed hardly enough for them to be rightly understood. (“Similar cautions are here added against assuming this too promiscuously.” – Alford)