This article is about the Greek term logos in philosophy, etc. For the term specifically in Christianity, see Logos (Christianity). For the graphic mark, emblem, or symbol used for identification derived from this Greek term[1], see Logo.

Logos (, ; Ancient Greek: λόγος, romanized: lógos, lit. ‘word, discourse, or reason’) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Aristotle first systemised the usage of the word, making it one of the three principles of rhetoric. This specific use identifies the word closely to the structure and content of text itself. This specific usage has then been developed through the history of western philosophy and rhetoric.

The word has also been used in different senses along with rhema. Both Plato and Aristotle used the term logos along with rhema to refer to sentences and propositions. It is primarily in this sense the term is also found in religion.

Background[edit]

Ancient Greek: λόγος, romanized: lógos, lit. ‘word, discourse, or reason’ is related to Ancient Greek: λέγω, romanized: légō, lit. ‘I say’ which is cognate with Latin: Legus, lit. ‘law’. The word derives from a Proto-Indo-European root, *leǵ-, which can have the meanings «I put in order, arrange, gather, choose, count, reckon, discern, say, speak». In modern usage, it typically connotes the verbs «account», «measure», «reason» or «discourse».[2][3]. It is occasionally used in other contexts, such as for «ratio» in mathematics.[4]

The Purdue Online Writing Lab clarifies that logos is the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning.[5] In the context of Aristotle’s Rhetoric, logos is one of the three principles of rhetoric and in that specific use it more closely refers to the structure and content of the text itself.[6]

Origins of the term[edit]

Logos became a technical term in Western philosophy beginning with Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC), who used the term for a principle of order and knowledge.[7] Ancient Greek philosophers used the term in different ways. The sophists used the term to mean discourse. Aristotle applied the term to refer to «reasoned discourse»[8] or «the argument» in the field of rhetoric, and considered it one of the three modes of persuasion alongside ethos and pathos.[9] Pyrrhonist philosophers used the term to refer to dogmatic accounts of non-evident matters. The Stoics spoke of the logos spermatikos (the generative principle of the Universe) which foreshadows related concepts in Neoplatonism.[10]

Within Hellenistic Judaism, Philo (c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD) integrated the term into Jewish philosophy.[11]

Philo distinguished between logos prophorikos («the uttered word») and the logos endiathetos («the word remaining within»).[12]

The Gospel of John identifies the Christian Logos, through which all things are made, as divine (theos),[13] and further identifies Jesus Christ as the incarnate Logos. Early translators of the Greek New Testament, such as Jerome (in the 4th century AD), were frustrated by the inadequacy of any single Latin word to convey the meaning of the word logos as used to describe Jesus Christ in the Gospel of John. The Vulgate Bible usage of in principio erat verbum was thus constrained to use the (perhaps inadequate) noun verbum for «word»; later Romance language translations had the advantage of nouns such as le Verbe in French. Reformation translators took another approach. Martin Luther rejected Zeitwort (verb) in favor of Wort (word), for instance, although later commentators repeatedly turned to a more dynamic use involving the living word as used by Jerome and Augustine.[14] The term is also used in Sufism, and the analytical psychology of Carl Jung.

Despite the conventional translation as «word», logos is not used for a word in the grammatical sense—for that, the term lexis (λέξις, léxis) was used.[15] However, both logos and lexis derive from the same verb légō (λέγω), meaning «(I) count, tell, say, speak».[2][15][16]

Ancient Greek philosophy[edit]

Heraclitus[edit]

The writing of Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC) was the first place where the word logos was given special attention in ancient Greek philosophy,[17] although Heraclitus seems to use the word with a meaning not significantly different from the way in which it was used in ordinary Greek of his time.[18] For Heraclitus, logos provided the link between rational discourse and the world’s rational structure.[19]

This logos holds always but humans always prove unable to ever understand it, both before hearing it and when they have first heard it. For though all things come to be in accordance with this logos, humans are like the inexperienced when they experience such words and deeds as I set out, distinguishing each in accordance with its nature and saying how it is. But other people fail to notice what they do when awake, just as they forget what they do while asleep.

For this reason it is necessary to follow what is common. But although the logos is common, most people live as if they had their own private understanding.

— Diels–Kranz, 22B2

Listening not to me but to the logos it is wise to agree that all things are one.

— Diels–Kranz, 22B50[20]

What logos means here is not certain; it may mean «reason» or «explanation» in the sense of an objective cosmic law, or it may signify nothing more than «saying» or «wisdom».[21] Yet, an independent existence of a universal logos was clearly suggested by Heraclitus.[22]

Aristotle’s rhetorical logos[edit]

Following one of the other meanings of the word, Aristotle gave logos a different technical definition in the Rhetoric, using it as meaning argument from reason, one of the three modes of persuasion. The other two modes are pathos (πᾰ́θος, páthos), which refers to persuasion by means of emotional appeal, «putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind»;[23] and ethos (ἦθος, êthos), persuasion through convincing listeners of one’s «moral character».[23] According to Aristotle, logos relates to «the speech itself, in so far as it proves or seems to prove».[23][24] In the words of Paul Rahe:

For Aristotle, logos is something more refined than the capacity to make private feelings public: it enables the human being to perform as no other animal can; it makes it possible for him to perceive and make clear to others through reasoned discourse the difference between what is advantageous and what is harmful, between what is just and what is unjust, and between what is good and what is evil.[8]

Logos, pathos, and ethos can all be appropriate at different times.[25] Arguments from reason (logical arguments) have some advantages, namely that data are (ostensibly) difficult to manipulate, so it is harder to argue against such an argument; and such arguments make the speaker look prepared and knowledgeable to the audience, enhancing ethos.[citation needed] On the other hand, trust in the speaker—built through ethos—enhances the appeal of arguments from reason.[26]

Robert Wardy suggests that what Aristotle rejects in supporting the use of logos «is not emotional appeal per se, but rather emotional appeals that have no ‘bearing on the issue’, in that the pathē [πᾰ́θη, páthē] they stimulate lack, or at any rate are not shown to possess, any intrinsic connection with the point at issue—as if an advocate were to try to whip an antisemitic audience into a fury because the accused is Jewish; or as if another in drumming up support for a politician were to exploit his listeners’s reverential feelings for the politician’s ancestors».[27]

Aristotle comments on the three modes by stating:

Of the modes of persuasion furnished by the spoken word there are three kinds.

The first kind depends on the personal character of the speaker;

the second on putting the audience into a certain frame of mind;

the third on the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself.

Stoics[edit]

Stoic philosophy began with Zeno of Citium c. 300 BC, in which the logos was the active reason pervading and animating the Universe. It was conceived as material and is usually identified with God or Nature. The Stoics also referred to the seminal logos («logos spermatikos«), or the law of generation in the Universe, which was the principle of the active reason working in inanimate matter. Humans, too, each possess a portion of the divine logos.[29]

The Stoics took all activity to imply a logos or spiritual principle. As the operative principle of the world, the logos was anima mundi to them, a concept which later influenced Philo of Alexandria, although he derived the contents of the term from Plato.[30] In his Introduction to the 1964 edition of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, the Anglican priest Maxwell Staniforth wrote that «Logos … had long been one of the leading terms of Stoicism, chosen originally for the purpose of explaining how deity came into relation with the universe».[31]

Isocrates’ logos[edit]

Public discourse on ancient Greek rhetoric has historically emphasized Aristotle’s appeals to logos, pathos, and ethos, while less attention has been directed to Isocrates’ teachings about philosophy and logos,[32] and their partnership in generating an ethical, mindful polis. Isocrates does not provide a single definition of logos in his work, but Isocratean logos characteristically focuses on speech, reason, and civic discourse.[32] He was concerned with establishing the «common good» of Athenian citizens, which he believed could be achieved through the pursuit of philosophy and the application of logos.[32]

In Hellenistic Judaism[edit]

Philo of Alexandria[edit]

Philo (c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD), a Hellenized Jew, used the term logos to mean an intermediary divine being or demiurge.[11] Philo followed the Platonic distinction between imperfect matter and perfect Form, and therefore intermediary beings were necessary to bridge the enormous gap between God and the material world.[33] The logos was the highest of these intermediary beings, and was called by Philo «the first-born of God».[33]

Philo also wrote that «the Logos of the living God is the bond of everything, holding all things together and binding all the parts, and prevents them from being dissolved and separated».[34]

Plato’s Theory of Forms was located within the logos, but the logos also acted on behalf of God in the physical world.[33] In particular, the Angel of the Lord in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) was identified with the logos by Philo, who also said that the logos was God’s instrument in the creation of the Universe.[33]

Targums[edit]

The concept of logos also appears in the Targums (Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible dating to the first centuries AD), where the term memra (Aramaic for «word») is often used instead of ‘the Lord’, especially when referring to a manifestation of God that could be construed as anthropomorphic.[35]

Christianity[edit]

In Christology, the Logos (Koinē Greek: Λόγος, lit. ‘word, discourse, or reason’)[3] is a name or title of Jesus Christ, seen as the pre-existent second person of the Trinity. The concept derives from John 1:1, which in the Douay–Rheims, King James, New International, and other versions of the Bible, reads:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.[36][37][38]

Gnosticism[edit]

According to the Gnostic scriptures recorded in the Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit, the Logos is an emanation of the great spirit that is merged with the spiritual Adam called Adamas.[39][better source needed]

Neoplatonism[edit]

Neoplatonist philosophers such as Plotinus (c. 204/5 – 270 AD) used logos in ways that drew on Plato and the Stoics,[40] but the term logos was interpreted in different ways throughout Neoplatonism, and similarities to Philo’s concept of logos appear to be accidental.[41] The logos was a key element in the meditations of Plotinus[42] regarded as the first neoplatonist. Plotinus referred back to Heraclitus and as far back as Thales[43] in interpreting logos as the principle of meditation, existing as the interrelationship between the hypostases—the soul, the intellect (nous), and the One.[44]

Plotinus used a trinity concept that consisted of «The One», the «Spirit», and «Soul». The comparison with the Christian Trinity is inescapable, but for Plotinus these were not equal and «The One» was at the highest level, with the «Soul» at the lowest.[45] For Plotinus, the relationship between the three elements of his trinity is conducted by the outpouring of logos from the higher principle, and eros (loving) upward from the lower principle.[46] Plotinus relied heavily on the concept of logos, but no explicit references to Christian thought can be found in his works, although there are significant traces of them in his doctrine.[citation needed] Plotinus specifically avoided using the term logos to refer to the second person of his trinity.[47] However, Plotinus influenced Gaius Marius Victorinus, who then influenced Augustine of Hippo.[48] Centuries later, Carl Jung acknowledged the influence of Plotinus in his writings.[49]

Victorinus differentiated between the logos interior to God and the logos related to the world by creation and salvation.[50]

Augustine of Hippo, often seen as the father of medieval philosophy, was also greatly influenced by Plato and is famous for his re-interpretation of Aristotle and Plato in the light of early Christian thought.[51] A young Augustine experimented with, but failed to achieve ecstasy using the meditations of Plotinus.[52] In his Confessions, Augustine described logos as the Divine Eternal Word,[53] by which he, in part, was able to motivate the early Christian thought throughout the Hellenized world (of which the Latin speaking West was a part)[54] Augustine’s logos had taken body in Christ, the man in whom the logos (i.e. veritas or sapientia) was present as in no other man.[55]

Islam[edit]

The concept of the logos also exists in Islam, where it was definitively articulated primarily in the writings of the classical Sunni mystics and Islamic philosophers, as well as by certain Shi’a thinkers, during the Islamic Golden Age.[56][57] In Sunni Islam, the concept of the logos has been given many different names by the denomination’s metaphysicians, mystics, and philosophers, including ʿaql («Intellect»), al-insān al-kāmil («Universal Man»), kalimat Allāh («Word of God»), haqīqa muḥammadiyya («The Muhammadan Reality»), and nūr muḥammadī («The Muhammadan Light»).

ʿAql[edit]

One of the names given to a concept very much like the Christian Logos by the classical Muslim metaphysicians is ʿaql, which is the «Arabic equivalent to the Greek νοῦς (intellect).»[57] In the writings of the Islamic neoplatonist philosophers, such as al-Farabi (c. 872 – c. 950 AD) and Avicenna (d. 1037),[57] the idea of the ʿaql was presented in a manner that both resembled «the late Greek doctrine» and, likewise, «corresponded in many respects to the Logos Christology.»[57]

The concept of logos in Sufism is used to relate the «Uncreated» (God) to the «Created» (humanity). In Sufism, for the Deist, no contact between man and God can be possible without the logos. The logos is everywhere and always the same, but its personification is «unique» within each region. Jesus and Muhammad are seen as the personifications of the logos, and this is what enables them to speak in such absolute terms.[58][59]

One of the boldest and most radical attempts to reformulate the neoplatonic concepts into Sufism arose with the philosopher Ibn Arabi, who traveled widely in Spain and North Africa. His concepts were expressed in two major works The Ringstones of Wisdom (Fusus al-Hikam) and The Meccan Illuminations (Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya). To Ibn Arabi, every prophet corresponds to a reality which he called a logos (Kalimah), as an aspect of the unique divine being. In his view the divine being would have for ever remained hidden, had it not been for the prophets, with logos providing the link between man and divinity.[60]

Ibn Arabi seems to have adopted his version of the logos concept from neoplatonic and Christian sources,[61] although (writing in Arabic rather than Greek) he used more than twenty different terms when discussing it.[62] For Ibn Arabi, the logos or «Universal Man» was a mediating link between individual human beings and the divine essence.[63]

Other Sufi writers also show the influence of the neoplatonic logos.[64] In the 15th century Abd al-Karīm al-Jīlī introduced the Doctrine of Logos and the Perfect Man. For al-Jīlī, the «perfect man» (associated with the logos or the Prophet) has the power to assume different forms at different times and to appear in different guises.[65]

In Ottoman Sufism, Şeyh Gâlib (d. 1799) articulates Sühan (logos—Kalima) in his Hüsn ü Aşk (Beauty and Love) in parallel to Ibn Arabi’s Kalima. In the romance, Sühan appears as an embodiment of Kalima as a reference to the Word of God, the Perfect Man, and the Reality of Muhammad.[66][relevant?]

Jung’s analytical psychology[edit]

Carl Jung contrasted the critical and rational faculties of logos with the emotional, non-reason oriented and mythical elements of eros.[67] In Jung’s approach, logos vs eros can be represented as «science vs mysticism», or «reason vs imagination» or «conscious activity vs the unconscious».[68]

For Jung, logos represented the masculine principle of rationality, in contrast to its feminine counterpart, eros:

Woman’s psychology is founded on the principle of Eros, the great binder and loosener, whereas from ancient times the ruling principle ascribed to man is Logos. The concept of Eros could be expressed in modern terms as psychic relatedness, and that of Logos as objective interest.[69]

Jung attempted to equate logos and eros, his intuitive conceptions of masculine and feminine consciousness, with the alchemical Sol and Luna. Jung commented that in a man the lunar anima and in a woman the solar animus has the greatest influence on consciousness.[70] Jung often proceeded to analyze situations in terms of «paired opposites», e.g. by using the analogy with the eastern yin and yang[71] and was also influenced by the neoplatonists.[72]

In his book Mysterium Coniunctionis Jung made some important final remarks about anima and animus:

In so far as the spirit is also a kind of «window on eternity»… it conveys to the soul a certain influx divinus… and the knowledge of a higher system of the world, wherein consists precisely its supposed animation of the soul.

And in this book Jung again emphasized that the animus compensates eros, while the anima compensates logos.[73]

Rhetoric[edit]

Author and professor Jeanne Fahnestock describes logos as a «premise». She states that, to find the reason behind a rhetor’s backing of a certain position or stance, one must acknowledge the different «premises» that the rhetor applies via his or her chosen diction.[74] The rhetor’s success, she argues, will come down to «certain objects of agreement…between arguer and audience». «Logos is logical appeal, and the term logic is derived from it. It is normally used to describe facts and figures that support the speaker’s topic.»[75] Furthermore, logos is credited with appealing to the audience’s sense of logic, with the definition of «logic» being concerned with the thing as it is known.[75]

Furthermore, one can appeal to this sense of logic in two ways. The first is through inductive reasoning, providing the audience with relevant examples and using them to point back to the overall statement.[76] The second is through deductive enthymeme, providing the audience with general scenarios and then indicating commonalities among them.[76]

Rhema[edit]

The word logos has been used in different senses along with rhema. Both Plato and Aristotle used the term logos along with rhema to refer to sentences and propositions.[77][78]

The Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek uses the terms rhema and logos as equivalents and uses both for the Hebrew word dabar, as the Word of God.[79][80][81]

Some modern usage in Christian theology distinguishes rhema from logos (which here refers to the written scriptures) while rhema refers to the revelation received by the reader from the Holy Spirit when the Word (logos) is read,[82][83][84][85] although this distinction has been criticized.[86][87]

See also[edit]

- -logy

- Dabar

- Dharma

- Epeolatry

- Imiaslavie

- Logic

- Logocracy

- Logos (Christianity)

- Logotherapy

- Nous

- Om

- Parmenides

- Ṛta

- Shabda

- Sophia (wisdom)

References[edit]

- ^ «logo-«. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon: logos, 1889.

- ^ a b Entry λόγος at LSJ online.

- ^ J. L. Heiberg, Euclid, Elements,

- ^ «Using Rhetorical Strategies for Persuasion». Owl.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ «Aristotle’s Rhetorical Situation // Purdue Writing Lab». Owl.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed): Heraclitus, (1999).

- ^ a b Paul Anthony Rahe, Republics Ancient and Modern: The Ancien Régime in Classical Greece, University of North Carolina Press (1994), ISBN 080784473X, p. 21.

- ^ Rapp, Christof, «Aristotle’s Rhetoric», The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 459. ISBN 978-0802836342.

- ^ a b Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed): Philo Judaeus, (1999).

- ^ Adam Kamesar (2004). «The Logos Endiathetos and the Logos Prophorikos in Allegorical Interpretation: Philo and the D-Scholia to the Iliad» (PDF). Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (GRBS). 44: 163–181. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-07.

- ^ May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ^ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 460. ISBN 978-0802836342.

- ^ a b Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon: lexis, 1889.

- ^ Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon: legō, 1889.

- ^ F. E. Peters, Greek Philosophical Terms, New York University Press, 1967.

- ^ W. K. C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, 1962, pp. 419ff.

- ^ The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Translations from Richard D. McKirahan, Philosophy before Socrates, Hackett, (1994).

- ^ Handboek geschiedenis van de wijsbegeerte 1, Article by Jaap Mansveld & Keimpe Algra, p. 41

- ^ W. K. C. Guthrie, The Greek Philosophers: From Thales to Aristotle, Methuen, 1967, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Aristotle, Rhetoric, in Patricia P. Matsen, Philip B. Rollinson, and Marion Sousa, Readings from Classical Rhetoric, SIU Press {1990), ISBN 0809315920, p. 120.

- ^ In the translation by W. Rhys Roberts, this reads «the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself».

- ^ Eugene Garver, Aristotle’s Rhetoric: An art of character, University of Chicago Press (1994), ISBN 0226284247, p. 114.

- ^ Garver, p. 192.

- ^ Robert Wardy, «Mighty Is the Truth and It Shall Prevail?», in Essays on Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Amélie Rorty (ed), University of California Press (1996), ISBN 0520202287, p. 64.

- ^ Translated by W. Rhys Roberts, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.mb.txt (Part 2, paragraph 3)

- ^ Tripolitis, A., Religions of the Hellenistic-Roman Age, pp. 37–38. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- ^ Studies in European Philosophy, by James Lindsay (2006), ISBN 1406701734, p. 53

- ^ Marcus Aurelius (1964). Meditations. London: Penguin Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0140441406.

- ^ a b c David M. Timmerman and Edward Schiappa, Classical Greek Rhetorical Theory and the Disciplining of Discourse (London: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010): 43–66

- ^ a b c d Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Volume 1, Continuum, (2003), pp. 458–462.

- ^ Philo, De Profugis, cited in Gerald Friedlander, Hellenism and Christianity, P. Vallentine, 1912, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Kohler, Kauffman (1901–1906). «Memra (= «Ma’amar» or «Dibbur,» «Logos»)». In Singer, Isidore; Funk, Isaac K.; Vizetelly, Frank H. (eds.). Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 464–465.

- ^ John 1:1

- ^ John 1:1

- ^ John 1:1

- ^ Alexander Böhlig; Frederik Wisse (1975). Nag Hammadi Codices III, 2 and IV, 2 — The Gospel of the Egyptians (the Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit) — Volumes 2-3. Brill. Retrieved 2022-09-23.

- ^ Michael F. Wagner, Neoplatonism and Nature: Studies in Plotinus’ Enneads, Volume 8 of Studies in Neoplatonism, SUNY Press (2002), ISBN 0791452719, pp. 116–117.

- ^ John M. Rist, Plotinus: The road to reality, Cambridge University Press (1967), ISBN 0521060850, pp. 84–101.

- ^ «Between Physics and Nous: Logos as Principle of Meditation in Plotinus», The Journal of Neoplatonic Studies, Volumes 7–8, (1999), p. 3

- ^ Handboek Geschiedenis van de Wijsbegeerte I, Article by Carlos Steel

- ^ The Journal of Neoplatonic Studies, Volumes 7–8, Institute of Global Cultural Studies, Binghamton University (1999), p. 16

- ^ Ancient philosophy by Anthony Kenny (2007). ISBN 0198752725 p. 311

- ^ The Enneads by Plotinus, Stephen MacKenna, John M. Dillon (1991) ISBN 014044520X p. xcii [1]

- ^ Neoplatonism in Relation to Christianity by Charles Elsee (2009) ISBN 1116926296 pp. 89–90 [2]

- ^ The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology edited by Alan Richardson, John Bowden (1983) ISBN 0664227481 p. 448 [3]

- ^ Jung and aesthetic experience by Donald H. Mayo, (1995) ISBN 0820427241 p. 69

- ^ Theological treatises on the Trinity, by Marius Victorinus, Mary T. Clark, p. 25

- ^ Neoplatonism and Christian thought (Volume 2), By Dominic J. O’Meara, p. 39

- ^ Hans Urs von Balthasar, Christian meditation Ignatius Press ISBN 0898702356 p. 8

- ^ Confessions, Augustine, p. 130

- ^ Handboek Geschiedenis van de Wijsbegeerte I, Article by Douwe Runia

- ^ De immortalitate animae of Augustine: text, translation and commentary, By Saint Augustine (Bishop of Hippo.), C. W. Wolfskeel, introduction

- ^ Gardet, L., «Kalām», in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ a b c d Boer, Tj. de and Rahman, F., «ʿAḳl», in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ Sufism: love & wisdom by Jean-Louis Michon, Roger Gaetani (2006) ISBN 0941532755 p. 242 [4]

- ^ Sufi essays by Seyyed Hossein Nasr 1973 ISBN 0873952332 p. 148]

- ^ Biographical encyclopaedia of Sufis by N. Hanif (2002). ISBN 8176252662 p. 39 [5]

- ^ Charles A. Frazee, «Ibn al-‘Arabī and Spanish Mysticism of the Sixteenth Century», Numen 14 (3), Nov 1967, pp. 229–240.

- ^ Little, John T. (January 1987). «Al-Ins?N Al-K?Mil: The Perfect Man According to Ibn Al-‘Arab?». The Muslim World. 77 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1987.tb02785.x.

Ibn al-‘Arabi uses no less than twenty-two different terms to describe the various aspects under which this single Logos may be viewed.

- ^ Dobie, Robert J. (2009). Logos and Revelation: Ibn ‘Arabi, Meister Eckhart, and Mystical Hermeneutics. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0813216775.

For Ibn Arabi, the Logos or «Universal Man» was a mediating link between individual human beings and the divine essence.

- ^ Edward Henry Whinfield, Masnavi I Ma’navi: The spiritual couplets of Maulána Jalálu-‘d-Dín Muhammad Rúmí, Routledge (2001) [1898], ISBN 0415245311, p. xxv.

- ^ Biographical encyclopaedia of Sufis N. Hanif (2002). ISBN 8176252662 p. 98 [6]

- ^ Betül Avcı, «Character of Sühan in Şeyh Gâlib’s Romance, Hüsn ü Aşk (Beauty and Love)» Archivum Ottomanicum, 32 (2015).

- ^ C.G. Jung and the psychology of symbolic forms by Petteri Pietikäinen (2001) ISBN 9514108574 p. 22

- ^ Mythos and logos in the thought of Carl Jung by Walter A. Shelburne (1988) ISBN 0887066933 p. 4 [7]

- ^ Carl Jung, Aspects of the Feminine, Princeton University Press (1982), p. 65, ISBN 0710095228.

- ^ Jung, Carl Gustav (August 27, 1989). Aspects of the Masculine. Ark Paperbacks. ISBN 9780744800920 – via Google Books.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung: critical assessments by Renos K. Papadopoulos (1992) ISBN 0415048303 p. 19

- ^ See the neoplatonic section above.

- ^ The handbook of Jungian psychology: theory, practice and applications by Renos K. Papadopoulos (2006) ISBN 1583911472 p. 118 [8]

- ^ Fahnestock, Jeanne. «The Appeals: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos».

- ^ a b «Aristotle’s Modes of Persuasion in Rhetoric: Ethos, Pathos and Logos». mountainman.com.au.

- ^ a b «Ethos, Pathos, and Logos». Archived from the original on 2013-01-16. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- ^ General linguistics by Francis P. Dinneen (1995). ISBN 0878402780 p. 118 [9]

- ^ The history of linguistics in Europe from Plato to 1600 by Vivien Law (2003) ISBN 0521565324 p. 29 [10]

- ^ Theological dictionary of the New Testament, Volume 1 by Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, Geoffrey William Bromiley (1985). ISBN 0802824048 p. 508 [11]

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q–Z by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1995). ISBN 0802837840 p. 1102 [12]

- ^ Old Testament Theology by Horst Dietrich Preuss, Leo G. Perdue (1996). ISBN 0664218431 p. 81 [13]

- ^ What Every Christian Ought to Know. Adrian Rogers (2005). ISBN 0805426922 p. 162 [14]

- ^ The Identified Life of Christ. Joe Norvell (2006) ISBN 1597812943 p. [15]

- ^ Boggs, Brenda (2008). Holy Spirit, Teach Me. Xulon Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1604774252.

- ^ Law, Terry (2006). The Fight of Every Believer: Conquering the Thought Attacks That War Against Your Mind. Harrison House. p. 45. ISBN 978-1577945802.

- ^ James T. Draper and Kenneth Keathley, Biblical Authority, Broadman & Holman (2001), ISBN 0805424539, p. 113.

- ^ John F. MacArthur, Charismatic Chaos, Zondervan (1993), ISBN 0310575729, pp. 45–46.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Logos.

- The Apologist’s Bible Commentary Archived 2015-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Logos definition and example Archived 2016-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- «Logos» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 919–921.

What is the definition of logos? The Lexham Bible Dictionary defines logos (λόγος) as “a concept word in the Bible symbolic of the nature and function of Jesus Christ. It is also used to refer to the revelation of God in the world.” Logos is a noun that occurs 330 times in the Greek New Testament. Of course, the word doesn’t always—in fact, it usually doesn’t—carry symbolic meaning. Its most basic and common meaning is simply “word,” “speech,” “utterance,” or “message.”

The most famous way the Bible uses logos is in reference to Jesus as the Word, such as in John 1:1:

In the beginning was the Word (logos), and the Word (logos) was with God, and the Word (logos) was God. (John 1:1)

Logos can also be used to refer to the Bible or some portion of the Bible as the Word of God (e.g., Matt 15:6; Luke 5:1; 8:21; 11:28; John 10:35–36; Acts 6:2, 7; Heb 13:7). It often has the preeminent word or message from God in view—namely, the gospel, as in 1 Thessalonians 1:4–6:

For we know, brothers loved by God, that he has chosen you, because our gospel came to you not only in word (logos), but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction. You know what kind of men we proved to be among you for your sake.

And you became imitators of us and of the Lord, for you received the word (logos) in much affliction, with the joy of the Holy Spirit.

Interestingly, the word logos is “arguably the most debated and most discussed word in the Greek New Testament,” writes Douglas Estes in his entry on this word in the Lexham Bible Dictionary (a free resource from Lexham Press).

Learn why it’s so debated, more details about the meaning of logos, and everything else you’ve ever wondered about the word—or skip to the topics that interest you.

- An in-depth look at the meaning of logos

- Where is logos used in the Bible?

- The significance of Jesus as the Logos

- The historical background of the concept of logos

- Resources to help you study Jesus as the Logos

- The Greek background of Logos: etymology and origins

- The reception of the concept of logos in early Church history

- Logos in culture

- 15 New Testament passages that use the word logos

- How to search for Old Testament verses that use logos in the Bible

An in-depth look at the meaning of logos

This section is adapted from Douglas Estes’ entry on logos in Lexham Bible Dictionary (LBD).

***

The Greek word logos simply means “word.” However, along with this most basic definition comes a host of quasi-technical and technical uses of the word logos in the Bible, as well as in ancient Greek literature. Its most famous usage is John 1:1:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

The standard rendering of logos in English is “word.” This holds true in English regardless of whether logos is used in a mundane or technical sense. Over the centuries, and in various languages, other suggestions have been made—such as the recent idea of rendering logos as “message” in English—but none have stuck with any permanency.

There are three primary uses for the word logos in the New Testament:

- Logos in its standard meaning designates a word, speech, or the act of speaking (Acts 7:22).

- Logos in its special meaning refers to the special revelation of God to people (Mark 7:13).

- Logos in its unique meaning personifies the revelation of God as Jesus the Messiah (John 1:14).

Since the writers of the New Testament used logos more than 300 times, mostly with the standard meaning, even this range of meaning is quite large. For example, its standard usage can mean:

- An accounting (Matt 12:36)

- A reason (Acts 10:29)

- An appearance or aural display (Col2:23)

- A preaching (1 Tim 5:17)

- A word (1 Cor 1:5)

The wide semantic range of logos lends itself well to theological and philosophical discourse.1

See how the Logos Bible app can help you research the meaning of other words in the Bible—in seconds.

Where is logos used in the Bible?

Logos in the Gospel of John

The leading use of logos in its unique sense occurs in the opening chapter of John’s Gospel. This chapter introduces the idea that Jesus is the Word: the Word that existed prior to creation, the Word that exists in connection to God, the Word that is God, and the Word that became human, cohabited with people, and possessed a glory that can only be described as the glory of God (John 1:1, 14).

As the Gospel of John never uses logos in this unique, technical manner again after the first chapter, and never explicitly says that the logos is Jesus, many have speculated that the Word-prologue predates the Gospel in the form of an earlier hymn or liturgy.2 However, there is little evidence for this, and attempts to recreate the hymn are highly speculative.3 While there is a multitude of theories for why the Gospel writer selected the logos concept-word, the clear emphasis of the opening of the Gospel and entrance of the Word into the world is cosmological, reflecting the opening of Genesis 1.4

Logos in the remainder of the New Testament

There are two other unique, personified uses of logos in the New Testament, both of which are found in the Johannine literature.

- In 1 John 1:1, Jesus is referred to as the “Word of life”; both “word” and “life” are significant to John, as this opening to the first letter is related in some way to the opening of the Gospel.

- In Revelation 19:13, the returning Messiah is called the “Word of God,” as a reference to his person and work as both the revealed and the revealer.

All of the remaining uses of logos in the New Testament are mostly standard uses, with a small number of special uses mixed in—for example, Acts 4:31, where logos refers to the gospel message:

When they had prayed, the place in which they were gathered together was shaken, and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and continued to speak the word (logos) of God with boldness.

Logos in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (LXX, or Septuagint, the translation of the Old Testament into Greek) use of logos closely matches both standard and special New Testament uses. As with the New Testament, most uses of logos in the Old Testament fit within the standard semantic range of “word” as speech, utterance, or word. The LXX does make regular use of logos to specify the “word of the Lord” (e.g., Isaiah 1:10, where the LXX translates דְבַר־יְהוָ֖ה davar yahweh), relating to the special proclamation of God in the world.

When used this way, logos does not mean the literal words or speech or message of God; instead, it refers to the “dynamic, active communication” of God’s purpose and plan to his people in light of his creative activity.5 The key difference between the Testaments is that there is no personification of logos in the Old Testament indicative of the Messiah. In Proverbs 8, the Old Testament personifies Wisdom (more on this below), leading some to believe this is a precursor to the unique, technical use of logos occurring in the Johannine sections of the New Testament.

***

See how the Logos Bible app makes researching Greek and Hebrew words in the Bible a cinch.

The significance of Jesus as the Logos

Much of what John says about the Logos can be found in Jewish literature about “divine Wisdom.”6

This means texts where Wisdom is “personified” probably circulated well before John wrote,7 so readers would have had some understanding of the idea behind Jesus as the Logos.

Hear from Ben Witherington III in his course The Wisdom of John on the role of the prologue in John’s Gospel (John 1:1), the profound truth that Jesus is the Logos who is both divine and human, and what it means that Jesus is the “Wisdom of God” personified:

This is why John uses logos to describe God’s revelation of himself. D. A. Carson writes in his commentary on John that God’s “Word” (logos) in the Old Testament “is his powerful self-expression in creation, revelation, and salvation, and the personification of that ‘Word’ makes it suitable for [him] to apply it as a title to God’s ultimate self-disclosure, the person of his own Son.”8

Jesus is Wisdom personified.

John intends for the whole of his Gospel to be read through the lens of John 1:1, writes C. K. Barrett: “The deeds and words of Jesus are the deeds and words of God; if this be not true, the book is blasphemous.”9

Resources to help you study Jesus as the Logos

The Gospel According to John (Pillar New Testament Commentary | PNTC)

Regular price: $33.99

Add to cart

The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction With Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text

Regular price: $27.99

Add to cart

The Gospel of John: A Commentary (2 vols.)

Regular price: $69.99

Add to cart

The Lexham English Septuagint, 2nd ed. (LES)

Regular price: $34.99

Add to cart

Classic Surveys on Greek Philosophy (5 vols.)

Regular price: $36.99

Add to cart

Addresses on the Gospel of John

Regular price: $8.99

Add to cart

List of Septuagint Words Sharing Common Elements

Regular price: $15.99

Add to cart

The Greek background of logos: etymology and origins

According to Brian K. Gamel in his entry in LBD on the Greek background of logos, the word acquired “special significance for ancient Greek philosophical concepts of language and the faculty of human thinking.” He says:

The word λόγος (logos) evolved from a primarily mathematical term to one identified with speech and rationality. At a basic level, logos means “to pick up, collect, count up, give account [in a bookkeeping sense]”—the act of bringing concrete items into relation with one another. Mathematicians used it to describe ratios, mathematical descriptions of two measurements in relationship to each other.10

Logos eventually came to communicate the idea of “giving an account” in the sense of explaining a story. Having been identified with language, logos came to mean all that language involves—both the act of sharing information and the thought that produces language. By the time Latin gained prominence, the Greek term logos was translated with the term oratio, referring to speech or the way inward thoughts are expressed, and ratio, referring to inward thinking itself.11

This wide range of meanings for logos made it a difficult term to translate and comprehend. In the sixth to fourth centuries BC, Greek philosophers made efforts to limit its meaning to rationality and speech. Modern translators must consider the context in which logos appears since its meaning varies widely depending on the author and the time of writing.12

Historical background of the concept of logos

This section on the historical background of the concept of logos is from Douglas Estes’ entry on logos in the Lexham Bible Dictionary.

***

Many theories have been proposed attempting to explain why the Gospel of John introduces Jesus as the Word.

Old Testament word

This theory proposes that the logos in John simply referred to the Old Testament word for word (דָּבָר, davar) as it related to the revelatory activity of God (the “word of the Lord,” 2 Sam 7:4), and then personified over time from the “word of God” (revelation) to the “Word of God.”13

This theory is the closest literary parallel and thought milieu to the New Testament. As a result, it has gained a wide range of general acceptance. The lack of evidence showing such a substantial shift in meaning is this theory’s major weakness.

Old Testament wisdom

In the centuries before the writing of the New Testament, the Jewish concept of Wisdom, or Sophia (σοφία, sophia), was personified as a literary motif in several texts (Proverbs, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch), prompting arguments that “Sophia” is the root idea for Logos.14

Paul appears to make a weak allusion to these two ideas also (1 Cor 1:24). This theory may be supported by the presence of a divine, personified hypostasis for God in Jewish contexts. The concept of Sophia shares some similarities with “Word.” However, Sophia may simply be a literary motif. Furthermore, it is unclear why the writer of the Gospel of John wouldn’t have simply used sophia instead of logos.

Jewish-Hellenistic popular philosophy

Philo (20 BC–AD 50), a Hellenistic Jew from Alexandria, wrote many books combining Hebrew and Greek theology and philosophy; he used logos in many different ways to refer to diverse aspects of God and his activity in the world.15

This theory is supported by the fact that Philo is a near-contemporary of John. Furthermore, the use of the language has several striking similarities.

However, this theory has three major weaknesses:

- Philo never appears to personify logos in the same way John does (perhaps due to his strict monotheism).

- Philo’s philosophical system is complex and frequently at odds with the Bible’s worldview.

- Philo was not influential in his lifetime.

John’s theology

One theory for the origin of the logos concept in the Gospel of John comes through the evolution of christological thought apparent in Johannine context: after working through the creation of the letters and the text of the Fourth Gospel, wherein the focus is repeatedly on the Christ as the revelation of God, the fourth evangelist may have written the prologue as the fruition and capstone of all of his thoughts on the person and work of Jesus.16

As this theory takes the thought process of the evangelist seriously, it is elegant and plausible. However, it does not actually answer the question regarding the origin of the concept, as the evangelist must have had some original semantic range for logos.

Greek philosophy

For Heraclitus and later Stoic philosophers, logos was a symbol of divine reason; it is possible that John borrowed this concept from the Hellenistic milieu in which he wrote.17

While few individuals support this theory today, early Church fathers such as Irenaeus and Augustine indirectly favored it. This theory may be plausible, as Greek philosophy did have a pervasive influence and was accepted by many in the early Church. However, there is no direct evidence that the writer of the Fourth Gospel knew or cared about Greek philosophy.

The Torah

In order to place the Gospel of John squarely in Jewish context, this theory proposes that logos is best understood as the incarnated Torah.18

The theory is based on some parallels between “word” and “law” (νόμος, nomos) in the LXX (Psa 119:15); thus, one could translate John 1:1 as Jacobus Schoneveld did: “In the beginning was the Torah, and the Torah was toward God, and Godlike was the Torah.” This theory’s major strength is that it encourages a Jewish context for reading John. Furthermore, some parallels between “word” and “law” are possible. However, as there is very limited evidence for such a personified reading, this theory has received only limited acceptance.

[…]

No accepted consensus regarding the origin of the logos concept-word exists. This much appears probable: the writer of the Gospel of John knew Greek, and thus must have encountered, to some degree, at least a rudimentary Hellenistic philosophical understanding of the use of logos; however, being first a Jew, not a Greek, the author was more concerned about Old Testament thought patterns and contemporary Jewish language customs. Thus, it seems likely that, in the proclamation of the Gospel over time, these strains bore christological fruit for the evangelist, culminating in the unique “Word” concept presented in John 1.

The reception of the concept of logos in early Church history

The logos concept was a foundational idea for theological development from the start of the early Church. Perhaps the earliest Christian document after the New Testament is 1 Clement (ca. AD 95–97), in which the author inserts logos in its special usage of God’s revelation (1 Clement 13.3). First Clement may also contain the first existing unique, technical usage of logos as Jesus outside of the New Testament (if 1 Clement 27.4 is read as an allusion to Colossians 1:16; if not, it is still a very close parallel to John 1:1 and Genesis 1:1). A similar allusion to the logos as God’s revelation/Bible (New Testament) occurs in the Letter of Barnabas 6:1719 (ca. AD 100) and Polycarp 7.220 (ca. AD 120).

The first and clearest reference to logos as Christ comes in the letters of Ignatius, a bishop of Antioch, who was martyred ca. AD 110 (To the Magnesians 8.221). By the middle of the second century, the logos concept began to appear in conventional (Letter to Diognetus 12.922), apologetic (Justin Martyr, Irenaeus) and theological (Irenaeus) uses. At the start of the third century, Origen’s23 focus on the logos as to the nature of Christ signaled the intense interest that Christian theology would put on the word in the future.

Logos in culture

The logos concept continues to influence Western culture; it is foundational to Christian belief. The Greek idea of logos (with variant connotations) was also a major influence in Heraclitus (ca. 540–480 BC), Isocrates (436–338 BC), Aristotle (384–322 BC), and the Stoics, even becoming part of ancient popular culture (Philo). The concept has continued to influence Western culture since that time, partly due to the philosophical tradition of the logos that resumed post-Fourth Gospel with Neo-Platonism and with various strains of Gnosticism. Propelled through the centuries in its comparison/contrast to Christian theology, the logos continued into modern philosophical discussion with diverse thinkers including Hegel (1770–1831), Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), Carl Jung (1875–1961), and Jacques Derrida (1930–2004).

Without the theology of the Gospel of John, it seems unlikely that logos would have remained popular into late medieval or modern thought. Logos is one of the very few Greek words of the New Testament to be transliterated into English and put into everyday Christian usage.

***

15 New Testament passages that use the word logos

Mark 13:31

Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words (logos) will not pass away.

Luke 6:47–48

Everyone who comes to me and hears my words (logos) and does them, I will show you what he is like: he is like a man building a house, who dug deep and laid the foundation on the rock. And when a flood arose, the stream broke against that house and could not shake it, because it had been well built.

John 1:1

In the beginning was the Word (logos), and the Word (logos) was with God, and the Word (logos) was God.

John 1:14

And the Word (logos) became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.

Galatians 6:6

Let the one who is taught the word (logos) share all good things with the one who teaches.

Acts 4:4

But many of those who had heard the word (logos) believed, and the number of the men came to about five thousand.

Romans 9:9 (NASB)

For this is the word (logos) of promise: “AT THIS TIME I WILL COME, AND SARAH SHALL HAVE A SON.”

1 Corinthians 1:18

For the word (logos) of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.

Philippians 2:14–16

Do all things without grumbling or disputing, that you may be blameless and innocent, children of God without blemish in the midst of a crooked and twisted generation, among whom you shine as lights in the world, holding fast to the word (logos) of life, so that in the day of Christ I may be proud that I did not run in vain or labor in vain.

Colossians 1:24–25

Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church, of which I became a minister according to the stewardship from God that was given to me for you, to make the word (logos) of God fully known.

2 Timothy 2:15

Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word (logos) of truth.

Hebrews 4:12

For the word (logos) of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart.

James 1:18

Of his own will he brought us forth by the word (logos) of truth, that we should be a kind of firstfruits of his creatures.

1 John 1:1

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word (logos) of life . . .

Revelation 1:1–2

The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants the things that must soon take place. He made it known by sending his angel to his servant John, who bore witness to the word (logos) of God and to the testimony of Jesus Christ, even to all that he saw.

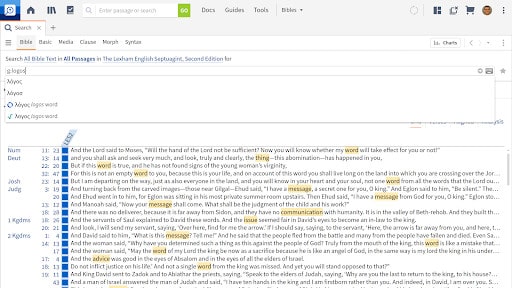

How to search for Old Testament passages that use logos in the Bible

There are more than 300 uses of logos in the New Testament alone, but the Septuagint (LXX)—the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures—uses logos hundreds of times too. Bible software like the Logos Bible app makes it easy to find every other use of logos in the Bible.24

Here’s how. The three easy steps below show how to find verses in the Old Testament that use logos with the Logos Bible app:

- Open a new Bible Search by clicking the magnifying glass search tool icon in the top left-hand corner of the application.

- Select your preferred version of the Septuagint (the Lexham English Septuagint was revised in 2020 and is a great choice, included in Logos Starter packages and above). See how.

- In the search box, enter g:logos (this lets you search using the Greek transliteration) and choose from the options that appear (the top option is the one we’re looking for).

You’ll find over 200 results in this search, each of which offers additional insight into the biblical usage of logos.

See how else Logos can help deepen your Bible study.

- Phillips, Peter M. The Prologue of the Fourth Gospel: A Sequential Reading. Library of New Testament Studies (London: T&T Clark, 2006),106.

- Rudolf Schnackenburg, The Gospel according to St John. 3 vols., Herder’s Theological Commentary on the New Testament (New York: Herder and Herder, 1968–82), 1.224–32; Jeremias, Jesus, 100.

- Craig S. Keener, Gospel of John: A Commentary, (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), 333–37.

- Estes, The Temporal Mechanics of the Fourth Gospel (Brill Academic Publishers, 2008), 107–13.

- Need, Stephen W. “Re-Reading the Prologue: Incarnation and Creation in John 1:1–18.” Theology 106 (2003): 399.

- Harris, Prologue, 43; Dodd, “Background,” 335; May, “Logos,” 438–47; O’Neill, “Prologue,” 49; Brown, John 1:520, 523; Weder, “Raum”; cf. Tobin, “Prologue.” See especially the list in Dodd, Interpretation, 274–75.

- Keener, Gospel of John, 353.

- D. A. Carson, The Gospel According to John (Pillar New Testament Commentary), 112–119.

- C. K. Barrett, The Gospel according to St John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text (SPCK, 21978).

- Brann, Eva. The Logos of Heraclitus (Philadelphia: Paul Dry, 2011), 10–11.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (London: George Bell, 1891) and Stephen Ullmann, Semantics (Oxford: Blackwell, 1962), 173.

- Edward Schiappa, Protagoras and Logos: A Study in Greek Philosophy and Rhetoric. 2nd ed. (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003), 91–92, 110.

- Carson, The Gospel According to John, 112–119.

- Scott, Martin. Sophia and the Johannine Jesus. Journal for the Study of the New Testament: Supplement Series 71 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press), 1992.

- Thomas H. Tobin, “The Prologue of John and Hellenistic Jewish Speculation.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52 (1990): 252–69.

- Ed. L. Miller, “The Johannine Origins of the Johannine Logos.” Journal of Biblical Literature 112:3 (1993): 445–57.

- Hook, Norman. “A Spirit Christology.” Theology 75 (1972): 227.

- Reed, David A. “How Semitic was John?: Rethinking the Hellenistic Background to John 1:1.” Anglican Theological Review 85:4 (2003): 709–26.

- So why, then, does he mention the “milk and honey”? Because the infant is first nourished with honey, and then with milk. So in a similar manner we too, being nourished by faith in the promise and by the word, will live and rule over the earth

- Therefore let us leave behind the worthless speculation of the crowd and their false teachings, and let us return to the word delivered to us from the beginning; let us be self-controlled with respect to prayer and persevere in fasting, earnestly asking the all-seeing God “to lead us not into temptation,” because, as the Lord said, “the spirit is indeed willing, but the flesh is weak.”

- The most godly prophets lived in accordance with Christ Jesus. This is why they were persecuted, being inspired as they were by his grace in order that those who are disobedient

- Furthermore, salvation is made known, and apostles are instructed, and the Passover of the Lord goes forward, and the congregations are gathered together, and all things are arranged in order, and the Word rejoices as he teaches the saints, the Word through whom the Father is glorified. To him be glory forever. Amen.

- Origen (Ὠριγένης, Ōrigenēs). Also known as Origen of Alexandria. A prolific and influential church father who lived ca. AD 185–254. Known for his allegorical approach to interpreting Scripture.

- Though the Old Testament was written in Hebrew, 70–72 Jewish scholars translated it into Greek in the third century BC. Therefore, we can learn a lot about logos by examining this work.

English[edit]

Etymology 1[edit]

From Ancient Greek λόγος (lógos, “speech, oration, discourse, quote, story, study, ratio, word, calculation, reason”).

Pronunciation[edit]

- (UK) IPA(key): /ˈlɒɡɒs/

- (US) IPA(key): /ˈloʊɡoʊs/, /ˈloʊɡɑs/

Noun[edit]

logos (plural logoi)

- (rhetoric) A form of rhetoric in which the writer or speaker uses logic as the main argument.

- Alternative letter-case form of Logos

Coordinate terms[edit]

- (form of rhetoric): ethos, pathos

Translations[edit]

Translations to be checked

- French: (please verify) logos (fr) m

Etymology 2[edit]

Noun[edit]

logos

- plural of logo

Anagrams[edit]

- slogo

Cornish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Proto-Brythonic *llugod, plural of *llug, from Proto-Celtic *lukūts.

Noun[edit]

logos f (singulative logosen or logojen)

- mice

Derived terms[edit]

- (Revived Late Cornish) logos broas

Czech[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Derived from Ancient Greek λόγος (lógos).

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): [ˈloɡos]

Noun[edit]

logos m

- Logos

[edit]

- analogický

- analogie

- antologie

- dialekt

- dialektální

- dialektický

- dialektik

- dialektika

- dialektismus

- dialektolog

- dialektologický

- dialektologie

- dialog

- dyslektický

- dyslektik

- dyslexie

- eklekticismus

- eklektický

- eklektik

- eklektismus

- epilog

- idiolekt

- lexém

- lexikalizace

- lexikalizovat

- lexikální

- lexikograf

- lexikografický

- lexikografie

- lexikolog

- lexikologický

- lexikologie

- lexikon

- -log

- logický

- -logie

- logik

- logika

- logo-

- logoped

- logopedický

- logopedie

- monolog

- nekrolog

- paralogismus

- prolog

- sociolekt

- sylogismus

- sylogistický

Further reading[edit]

- logos in Příruční slovník jazyka českého, 1935–1957

- logos in Slovník spisovného jazyka českého, 1960–1971, 1989

Esperanto[edit]

Verb[edit]

logos

- future of logi

French[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

Noun[edit]

logos m

- plural of logo

Italian[edit]

Noun[edit]

logos m (invariable)

- logos

Anagrams[edit]

- sgolo, sgolò, slogo, slogò, solgo

Latin[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Ancient Greek λόγος (lógos).

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Classical) IPA(key): /ˈlo.ɡos/, [ˈɫ̪ɔɡɔs̠]

- (Ecclesiastical) IPA(key): /ˈlo.ɡos/, [ˈlɔːɡos]

Noun[edit]

logos m (genitive logī); second declension

- a word

- (in the plural) idle talk, empty chatter

- a witticism, bon mot

- reason

- Synonym: ratiō

Declension[edit]

Second-declension noun (Greek-type).

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | logos | logī |

| Genitive | logī | logōrum |

| Dative | logō | logīs |

| Accusative | logon | logōs |

| Ablative | logō | logīs |

| Vocative | loge | logī |

References[edit]

- “logos”, in Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short (1879) A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- “logos”, in Charlton T. Lewis (1891) An Elementary Latin Dictionary, New York: Harper & Brothers

- logos in Gaffiot, Félix (1934) Dictionnaire illustré latin-français, Hachette

Latvian[edit]

Noun[edit]

logos m

- locative plural form of logs

Portuguese[edit]

Noun[edit]

logos

- plural of logo

Romanian[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Learned borrowing from Ancient Greek λόγος (lógos).

Noun[edit]

logos n (plural logosuri)

- logos

Declension[edit]

Serbo-Croatian[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Ancient Greek λόγος (lógos).

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /lôːɡos/

- Hyphenation: lo‧gos

Noun[edit]

lȏgos m (Cyrillic spelling ло̑гос)

- (philosophy, religion) logos

Declension[edit]

Declension of logos

| singular | |

|---|---|

| nominative | lȏgos |

| genitive | lȏgosa |

| dative | lȏgosu |

| accusative | lȏgos |

| vocative | lȏgose |

| locative | lȏgosu |

| instrumental | lȏgosom |

Spanish[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈloɡos/ [ˈlo.ɣ̞os]

- Rhymes: -oɡos

- Syllabification: lo‧gos

Noun[edit]

logos m pl

- plural of logo

Swedish[edit]

Noun[edit]

logos

- indefinite genitive singular of logo.

Anagrams[edit]

- slogo

West Makian[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Said by Voorhoeve to be of Austronesian origin.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈl̪o.ɡos̪/

Noun[edit]

logos

- coral (of a reef)

References[edit]

- Clemens Voorhoeve (1982) The Makian languages and their neighbours[1], Pacific linguistics

Word «logos» in Greek spelling

Logos (λόγος) is a Greek word that means «word,» «speech,» «reason» or «account». It became a technical term in philosophy beginning with Heraclitus (ca. 535–475 BC), who used the term for a principle of order and knowledge.[1] H. P. Blavatsky defined it as, «The manifested deity with every nation and people; the outward expression, or the effect of the cause which is ever concealed.»[2] In her writings, the concealed cause of the logos is frequently referred to as the «unmanifested logos,» and there are also references to a semi-manifested logos.

Contents

- 1 General description

- 2 First Logos

- 3 Second Logos

- 3.1 Origin of the Dhyāni-Buddhas

- 4 Third Logos

- 4.1 First manifested Logos

- 4.2 Divine Thought

- 5 Female Logos

- 6 The Army of the Voice

- 7 Ancient Greek philosophy

- 8 Christianity

- 9 Online resources

- 9.1 Articles

- 10 Notes

General description

H. P. Blavatsky talks about three Logoi: «the unmanifested ‘Father,’ the semi-manifested ‘Mother’ and the Universe, which is the third Logos of our philosophy or Brahmâ.»[3] These three Logoi can be seen as «the personified symbols of the three spiritual stages of Evolution.»[4] Yet all the three Logoi are one.[5]

There is no differentiation with the First Logos; differentiation only begins in latent World-Thought, with the Second Logos, and receives its full expression, i. e., becomes the «Word» made flesh—with the Third.[6]

The point within the circle which has neither limit nor boundaries, nor can it have any name or attribute. This first unmanifested Logos is simultaneous with the line drawn across the diameter of the Circle. The first line or diameter is the Mother-Father; from it proceeds the Second Logos, which contains in itself the Third Manifested Word.[7]

There seems to be great confusion and misunderstanding concerning the First and Second Logos. The first is the already present yet still unmanifested potentiality in the bosom of Father-Mother; the Second is the abstract collectivity of creators called “Demiurgi” by the Greeks or the Builders of the Universe. The third logos is the ultimate differentiation of the Second and the individualization of Cosmic Forces, of which Fohat is the chief; for Fohat is the synthesis of the Seven Creative Rays or Dhyan Chohans which proceed from the third Logos.[8]

First Logos

The First Logos is unmanifested, and it is the first stage in the process of reawakening of the cosmos from the rest in pralaya. It is the Pre-Cosmic Ideation that radiates from (or in) the Absolute. This Logos is frequently depicted as a white «potential» point in a black circle.[9]

When the first Logos radiates through primordial and undifferentiated matter there is as yet no action in Chaos. “The last vibration of the Seventh Eternity” is the first which announces the Dawn, and is a synonym for the First or unmanifested Logos. There is no Time at this stage. There is neither Space nor Time when beginning is made; but it is all in Space and Time, once that differentiation sets in.[10]

Associated to the unmanifested Logos is the idea of a «ray» that flashes out from it, and begins the differentiation in matter:

The Ray [is] periodical. Having flashed out from this central point and thrilled through the Germ, the Ray is withdrawn again within this point and the Germ develops into the Second Logos, the triangle within the Mundane Egg.[11]

Second Logos

The concept of the Second Logos is somewhat problematic. It is frequently seen as a bridge between the unmanifested and the manifested Logoi, «the Second Logos partaking of both the essences or natures of the first and the last.[12] Because of this, this Logos is sometimes said to be semi-manifested: «the three Logoi [are] the unmanifested “Father,” the semi-manifested “Mother” and the Universe, which is the third Logos of our philosophy or Brahmâ».

Because of its dual nature, the second Logos is sometimes spoken of as unmanifested, and in other occasions as being manifested. Besides, sometimes Blavatsky talks of only two Logoi: the unmanifested and the manifested, assimilating the semi-manifested Logos to these two. In these instances, when she speaks of the «second Logos» she is referring to the manifested one, that is, the Third Logos in the three-fold classification.

The word «mother» is not always associated to the second Logos. Most frequently we find that of Father-Mother:

At the time of the primordial radiation, or when the Second Logos emanates, it is Father-Mother potentially, but when the Third or manifested Logos appears, it becomes the Virgin-Mother.[13]

The ray that comes from the first Logos begins the process of differentiation in the pre-cosmic substance, and this produces the Second Logos. If we consider the first Logos as a potential point, the second is seen as the first real (or maybe, dimensional) point:

The first stage is the appearance of the potential point in the circle—the unmanifested Logos. The second stage is the shooting forth of the Ray from the potential white point, producing the first point, which is called, in the Zohar, Kether or Sephira. The third stage is the production from Kether of Chochmah, and Binah, thus constituting the first triangle, which is the Third or manifested Logos.[14]

In fact, the «point» of the second Logos is in the «mundane egg», and is said to be an abstract triangle :

The Point in the Circle is the Unmanifested Logos, the Manifested Logos is the Triangle. . . . It is this ideal or abstract triangle which is the Point in the Mundane Egg, which, after gestation, and in the third remove, will start from the Egg to form the Triangle. This is Brahmâ-Vâch-Virâj in the Hindu Philosophy and Kether-Chochmah-Binah in the Zohar.[15]

The point in the Circle is the Unmanifested Logos, corresponding to Absolute Life and Absolute Sound. The first geometrical figure after the Circle or the Spheroid is the Triangle. It corresponds to Motion, Color and Sound. Thus the Point in the Triangle represents the Second Logos, “Father-Mother,” or the White Ray which is no color, since it contains potentially all colors. It is shown radiating from the Unmanifested Logos, or the Unspoken Word. Around the first Triangle is formed on the plane of Primordial Substance in this order (reversed as to our plane).[16]

Origin of the Dhyāni-Buddhas

The second Logos in the «Arupa world» is said to emanate the Dhyāni-Buddhas:

This is the second logos of creation, from whom emanate the seven (in the exoteric blind the five) Dhyani Buddhas, called the Anupadaka, “the parentless.” These Buddhas are the primeval monads from the world of incorporeal being, the Arupa world, wherein the Intelligences (on that plane only) have neither shape nor name, in the exoteric system, but have their distinct seven names in esoteric philosophy.[17]

However, they seem to be emanated from the unmanifested aspect of this Logos:

The former [Dhyāni-Buddhas] only are called Anupadaka, parentless, because they radiated directly from that which is neither Father nor Mother but the unmanifested Logos.[18]

«That which is neither Father nor Mother» is probably refers to this Logos in its character of «Father-Mother».

Third Logos

This is the manifested Logos, called The Secret Doctrine the “luminous sons of manvantaric dawn”.[19] Mme. Blavatsky wrote:

When the hour strikes for the Third Logos to appear, then from the latent potentiality there radiates a lower field of differentiated consciousness, which is Mahat, or the entire collectivity of those Dhyan-Chohans of sentient life of which Fohat is the representative on the objective plane and the Manasaputras on the subjective.[20]

Then, at the first radiation of dawn, the “Spirit of God” (after the First and Second Logos were radiated), the Third Logos, or Narayan, began to move on the face of the Great Waters of the “Deep.”[21]

Some synonyms in other traditions are Mahat (Hinduism), Adam Kadmon (Kabbalah),[22] Protogonos (Greek/Orphic)[23], Brahmā (Hinduism), among others.

First manifested Logos

In some passages Mme. Blavatsky speaks of a manifested «First Logos». For example, she says:

The first is the Mother Goddess [ Mūlaprakṛti ], the reflection of the subjective root [ Parabrahman ], on the first plane of Substance. Then follows, issuing from, or rather residing in, this Mother Goddess, the unmanifested Logos, he who is both her Son and Husband at once, called the “concealed Father.” From these proceeds the first-manifested Logos, or Spirit, and the Son from whose substance emanate the Seven Logoi, whose synthesis, viewed as one collective Force, becomes the Architect of the Visible Universe.[24]

The First Manifested Logos is the Potentia, the unrevealed Cause; the Second, the still latent thought; the Third, the Demiurgus, the active Will evolving from its universal Self the active effect, which, in its turn, becomes the cause on a lower plane.[25]

The Ah-hi are the primordial seven rays, or Logoi, emanated from the first Logos, triple, yet one in its essence.[26]

This First Logos, «triple» in essence, cannot be the First unmanifested Logos which admits not plurality:

Moreover, in Occult metaphysics there are, properly speaking, two “ONES”—the One on the unreachable plane of Absoluteness and Infinity, on which no speculation is possible, and the Second “One” on the plane of Emanations. The former can neither emanate nor be divided, as it is eternal, absolute, and immutable. The Second, being, so to speak, the reflection of the first One (for it is the Logos, or Eswara, in the Universe of Illusion), can do all this. It emanates from itself . . . the seven Rays or Dhyan Chohans.[27]

Âkâsa [is] the Universal Space in which lies inherent the eternal Ideation of the Universe in its ever-changing aspects on the planes of matter and objectivity, and from which radiates the First Logos, or expressed thought.[28]

It is possible that the manifested Logos also undergoes the stages of first, second and third, on the manifested plane.

Divine Thought

«Divine Thought» is a phrase frequently used by Mme. Blavatsky, for the «Cosmic Ideation»,[29] and considered it as «the Logos, or the male aspect of the Anima Mundi, Alaya».[30] In it «lies concealed the plan of every future Cosmogony and Theogony».[31] The Upadhi of Divine Thought is Akasha, the Primordial Substance.[32]

Talking about the lotus as a symbol, Mme. Blavatsky wrote:

The underlying idea in this symbol is very beautiful, and it shows, furthermore, its identical parentage in all the religious systems. Whether in the lotus or water-lily shape it signifies one and the same philosophical idea—namely, the emanation of the objective from the subjective, divine Ideation passing from the abstract into the concrete or visible form. For, as soon as DARKNESS—or rather that which is “darkness” for ignorance—has disappeared in its own realm of eternal Light, leaving behind itself only its divine manifested Ideation, the creative Logoi have their understanding opened, and they see in the ideal world (hitherto concealed in the divine thought) the archetypal forms of all, and proceed to copy and build or fashion upon these models forms evanescent and transcendent.

At this stage of action, the Demiurge is not yet the Architect. Born in the twilight of action, he has yet to first perceive the plan, to realise the ideal forms which lie buried in the bosom of Eternal Ideation, as the future lotus-leaves, the immaculate petals, are concealed within the seed of that plant.[33]

The Cosmos is fashioned by the Builders, following the plan traced out for them in the Divine Thought.[34] This thought impregnates matter,[35] and can be perceived «by the numberless manifestations of Cosmic Substance in which the former is sensed spiritually by those who can do so».[36]

It is important to keep in mind that the phrase «Divine Thought» neither implies the idea of a Divine thinker[37] nor of a process of thinking:

It is hardly necessary to remind the reader once more that the term “Divine Thought,” like that of “Universal Mind,” must not be regarded as even vaguely shadowing forth an intellectual process akin to that exhibited by man.[38]

Female Logos

Mme. Blavatsky stated that female deities such as Vāc, Isis, Mout, Shekinah (Sephira), Kwan-Yin, etc. represent the female aspect of the creator:

They are all the symbols and personifications of Chaos, the “Great Deep” or the Primordial Waters of Space, the impenetrable veil between the incognisable and the Logos of Creation. “Connecting himself through his mind with Vach, Brahma (the Logos) created the primordial waters.” In the Kathaka Upanishad it is stated still more clearly: “Prajapati was this Universe. Vach was a second to him. He associated with her . . . she produced these creatures and again re-entered Prajapati.”* (* This connects Vâch and Sephira with the goddess Kwan-Yin, the «merciful mother», the divine VOICE of the soul even in Exoteric Buddhism; and with the female aspect of Kwan-Shai-yin, the Logos, the verbum of Creation, and at the same time with the voice that speaks audibly to the Initiate, according to Esoteric Buddhism. Bath Kol, the filia Vocis, the daughter of the divine voice of the Hebrews, responding from the mercy seat within the veil of the temple is—a result).[39]

Kwan-Yin, [is] the “Divine Voice” literally. This “Voice” is a synonym of the Verbum or the Word: “Speech,” as the expression of thought. Thus may be traced the connection with, and even the origin of the Hebrew Bath-Kol, the “daughter of the Divine Voice,” or Verbum, or the male and female Logos, the “Heavenly Man” or Adam Kadmon, who is at the same time Sephira. The latter was surely anticipated by the Hindu Vâch, the goddess of Speech, or of the Word. For Vâch—the daughter and the female portion, as is stated, of Brahmâ, one “generated by the gods”—is, in company with Kwan-Yin, with Isis (also the daughter, wife and sister of Osiris) and other goddesses, the female Logos, so to speak, the goddess of the active forces in Nature, the Word, Voice or Sound, and Speech. If Kwan-Yin is the “melodious Voice,” so is Vâch; “the melodious cow who milked forth sustenance and water” (the female principle)—“who yields us nourishment and sustenance,” as Mother-Nature. She is associated in the work of creation with the Prajâpati. She is male and female ad libitum [«as you desire»], as Eve is with Adam. And she is a form of Aditi—the principle higher than Ether—in Akâsa, the synthesis of all the forces in Nature; thus Vâch and Kwan-Yin are both the magic potency of Occult sound in Nature and Ether—which “Voice” calls forth Sien-Tchan, the illusive form of the Universe out of Chaos and the Seven Elements.[40]

The female logoi are many times regarded as triple: the mother, wife, and daughter of the male Logos.[41] This has to be interpreted in a cosmic sense, where «mother, wife and daughter» are different stages of differentiation of the primordial matter in which develops the Logos:

There is certainly a cosmic, not a physiological meaning attached to the Indian allegory, since Vâch is a permutation of Aditi and Mulaprakriti (Chaos), and Brahmâ a permutation of Naràyana, the Spirit of God entering into, and fructifying nature; therefore, there is nothing phallic in the conception at all.[42]

The Army of the Voice

In Stanza IV.4 there is a mention to «the Army of the Voice». Mme. Blavatsky wrote:

This Sloka gives again a brief analysis of the Hierarchies of the Dhyan Chohans, called Devas (gods) in India, or the conscious intelligent powers in Nature. To this Hierarchy correspond the actual types into which humanity may be divided; for humanity, as a whole, is in reality a materialized though as yet imperfect expression thereof. The “army of the Voice” is a term closely connected with the mystery of Sound and Speech, as an effect and corollary of the cause—Divine Thought.[43]