-

The

notion of ‘grammatical meaning’.

The word

combines in its semantic structure two meanings – lexical and

grammatical. Lexical meaning

is the individual meaning of the word (e.g. table).

Grammatical meaning

is the meaning of the whole class or a subclass. For example, the

class of nouns has the grammatical meaning of thingness.

If we take a noun (table)

we may say that it possesses its individual lexical meaning (it

corresponds to a definite piece of furniture) and the grammatical

meaning of thingness

(this is the meaning of the whole class). Besides, the noun ‘table’

has the grammatical meaning of a subclass – countableness.

Any verb combines its individual lexical meaning with the grammatical

meaning of verbiality – the ability to denote actions or states. An

adjective combines its individual lexical meaning with the

grammatical meaning of the whole class of adjectives –

qualitativeness – the ability to denote qualities. Adverbs possess

the grammatical meaning of adverbiality – the ability to denote

quality of qualities.

There are some classes of

words that are devoid of any lexical meaning and possess the

grammatical meaning only. This can be explained by the fact that they

have no referents in the objective reality. All function words belong

to this group – articles, particles, prepositions, etc.

-

Types

of grammatical meaning.

The

grammatical meaning may be explicit and implicit. The implicit

grammatical meaning is not expressed

formally (e.g. the word table does

not contain any hints in its form as to it being inanimate). The

explicit grammatical

meaning is always marked morphologically – it has its marker. In

the word cats the

grammatical meaning of plurality is shown in the form of the noun;

cat’s –

here the grammatical meaning of possessiveness is shown by the form

‘s; is

asked – shows the explicit

grammatical meaning of passiveness.

The

implicit grammatical meaning may be of two types – general and

dependent. The general

grammatical meaning is the meaning of the whole word-class, of a part

of speech (e.g. nouns – the general grammatical meaning of

thingness). The dependent

grammatical meaning is the meaning of a subclass within the same part

of speech. For instance, any verb possesses the dependent grammatical

meaning of transitivity/intransitivity,

terminativeness/non-terminativeness, stativeness/non-stativeness;

nouns have the dependent grammatical meaning of

contableness/uncountableness and animateness/inanimateness. The most

important thing about the dependent grammatical meaning is that it

influences the realization of grammatical categories restricting them

to a subclass. Thus the dependent grammatical meaning of

countableness/uncountableness influences the realization of the

grammatical category of number as the number category is realized

only within the subclass of countable nouns, the grammatical meaning

of animateness/inanimateness influences the realization of the

grammatical category of case, teminativeness/non-terminativeness —

the category of tense, transitivity/intransitivity – the category

of voice.

GRAMMATICAL

MEANING

IMPLICIT

GENERAL

DEPENDENT

-

Grammatical

categories.

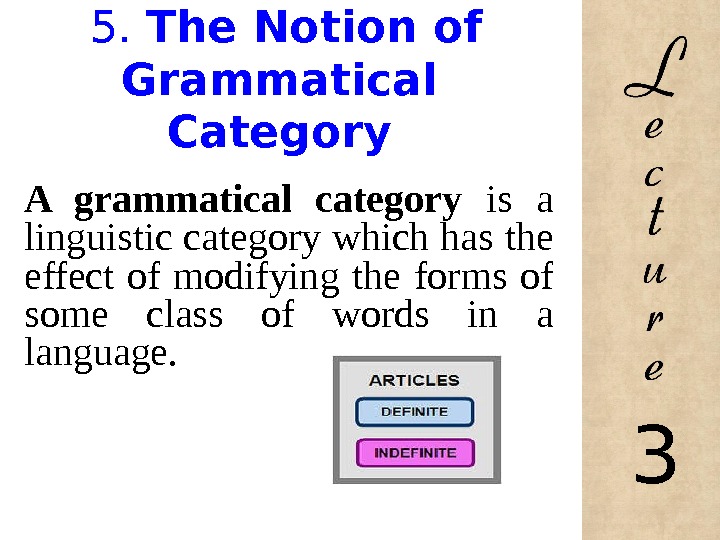

Grammatical categories are

made up by the unity of identical grammatical meanings that have the

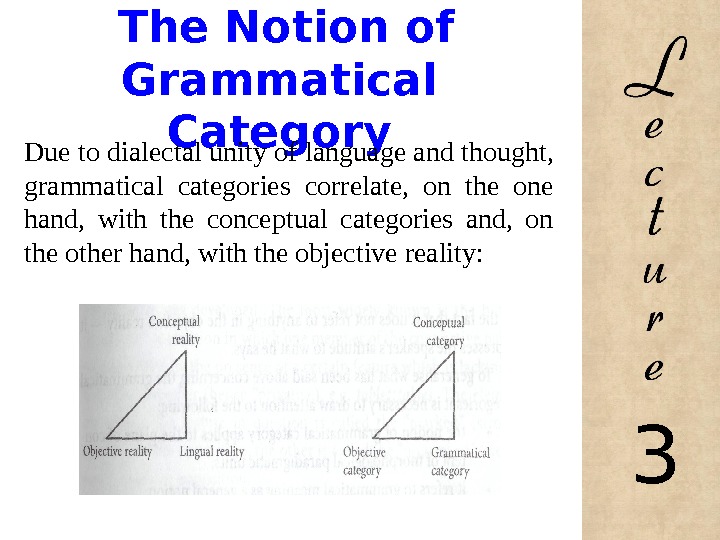

same form (e.g. singular::plural). Due to dialectal unity of language

and thought, grammatical categories correlate, on the one hand, with

the conceptual categories and, on the other hand, with the objective

reality. It may be shown with the help of a triangle model:

Conceptual

reality Conceptual category

Objective

reality Lingual reality Objective category Grammatical

category

It

follows that we may define grammatical categories as references of

the corresponding objective categories. For example, the objective

category of time

finds its representation in the grammatical category of tense,

the objective category of quantity finds

its representation in the grammatical category of number.

Those grammatical categories that have references in the objective

reality are called referential

grammatical categories. However, not

all of the grammatical categories have references in the objective

reality, just a few of them do not correspond to anything in the

objective reality. Such categories correlate only with conceptual

matters:

correlate

Lingual

correlate

They

are called significational categories.

To this type belong the categories of mood

and degree.

Speaking about the grammatical category of mood we can say that it

has modality

as its conceptual correlate. It can be explained by the fact that it

does not refer to anything in the objective reality – it expresses

the speaker’s attitude to what he says.

-

The

notion of opposition.

Any

grammatical category must be represented by at least two grammatical

forms (e.g. the grammatical category of number – singular and

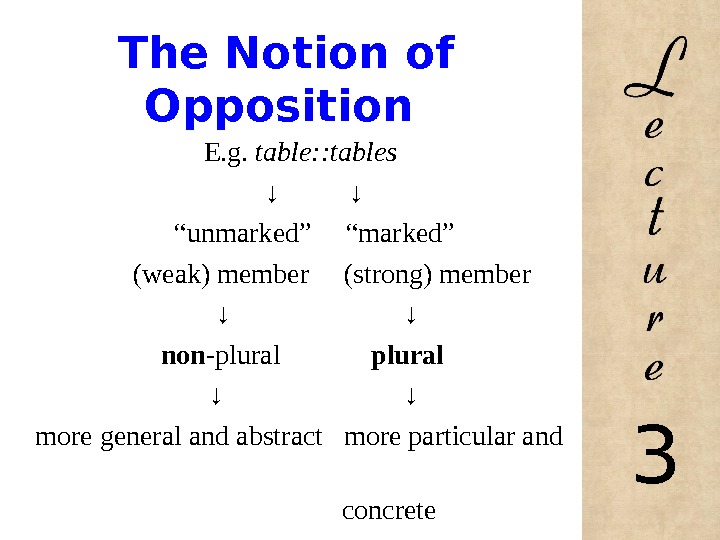

plural forms). The relation between two grammatical forms differing

in meaning and external signs is called opposition

– book::books

(unmarked member/marked member). All grammatical categories find

their realization through oppositions, e.g. the grammatical category

of number is realized through the opposition singular::plural.

Taking

all the above mentioned into consideration, we may define the

grammatical category as the opposition between two mutually exclusive

form-classes (a form-class is a set of words with the same explicit

grammatical meaning).

Means

of realization of grammatical

categories may be synthetic (near –

nearer) and analytic (beautiful

– more beautiful).

-

Transposition

and neutralization of morphological forms.

In the process of

communication grammatical categories may undergo the processes of

transposition and neutralization.

Transposition

is the use of a linguistic unit in an

unusual environment or in the function that is not characteristic of

it (He is a lion).

In the sentence He is coming tomorrow

the paradigmatic meaning of the

continuous form is reduced and a new meaning appears – that of a

future action. Transposition always results in the neutralization of

a paradigmatic meaning. Neutralization

is the reduction of the opposition to one of its members : custom ::

customs – x :: customs; x :: spectacles.

LECTURE 4: THE PARTS OF

SPEECH PROBLEM. WORD CLASSES

The parts of speech are

classes of words, all the members of these classes having certain

characteristics in common which distinguish them from the members of

other classes. The problem of word classification into parts of

speech still remains one of the most controversial problems in modern

linguistics. The attitude of grammarians with regard to parts of

speech and the basis of their classification varied a good deal at

different times. Only in English grammarians have been vacillating

between 3 and 13 parts of speech. There are four approaches to the

problem:

-

Classical

(logical-inflectional) -

Functional

-

Distributional

-

Complex

The

classical

parts of speech theory goes back to ancient times. It is based on

Latin grammar. According to the Latin classification of the parts of

speech all words were divided dichotomically into declinable

and indeclinable

parts of speech. This system was

reproduced in the earliest English grammars. The first of these

groups, declinable words, included nouns, pronouns, verbs and

participles, the second – indeclinable words – adverbs,

prepositions, conjunctions and interjections. The

logical-inflectional classification is quite successful for Latin or

other languages with developed morphology and synthetic paradigms but

it cannot be applied to the English language because the principle of

declinability/indeclinability is not relevant for analytical

languages.

A

new approach to the problem was introduced in the XIX century by

Henry Sweet. He took into account the peculiarities of the English

language. This approach may be defined as functional.

He resorted to the functional features of words and singled out

nominative units and particles. To nominative

parts of speech belonged noun-words

(noun, noun-pronoun, noun-numeral, infinitive, gerund),

adjective-words

(adjective, adjective-pronoun, adjective-numeral, participles), verb

(finite verb, verbals – gerund, infinitive, participles), while

adverb, preposition,

conjunction

and interjection

belonged to the group of particles.

However, though the criterion for classification was functional,

Henry Sweet failed to break the tradition and classified words into

those having morphological forms and lacking morphological forms, in

other words, declinable and indeclinable.

A

distributional approach

to the parts to the parts of speech

classification can be illustrated by the classification introduced by

Charles Fries. He wanted to avoid the traditional terminology and

establish a classification of words based on distributive analysis,

that is, the ability of words to combine with other words of

different types. At the same time, the lexical meaning of words was

not taken into account. According to Charles Fries, the words in

such sentences as 1. Woggles ugged diggles; 2. Uggs woggled diggs;

and 3. Woggs diggled uggles are quite evident structural signals,

their position and combinability are enough to classify them into

three word-classes. In this way, he introduced four major classes

of words and 15 form-classes.

Let us see how it worked. Three test frames

formed the basis for his analysis:

Frame

A — The concert was good (always);

Frame

B — The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly);

Frame

C – The team went there.

It

turned out that his four classes of words were practically the same

as traditional nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. What is really

valuable in Charles Fries’ classification is his investigation of

15 groups of function words (form-classes) because he was the first

linguist to pay attention to some of their peculiarities.

All

the classifications mentioned above appear to be one-sided because

parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of only one aspect of

the word: either its meaning or its form, or its function.

In

modern linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated according to

three criteria: semantic, formal and functional. This approach may be

defined as complex.

The semantic

criterion presupposes the grammatical meaning of the whole class of

words (general grammatical meaning). The formal

criterion reveals paradigmatic

properties: relevant grammatical categories, the form of the words,

their specific inflectional and derivational features. The functional

criterion concerns the syntactic

function of words in the sentence and their combinability. Thus, when

characterizing any part of speech we are to describe: a) its

semantics; b) its morphological features; c) its syntactic

peculiarities.

The

linguistic evidence drawn from our grammatical study makes it

possible to divide all the words of the language into:

-

those

denoting things, objects, notions, qualities, etc. – words with

the corresponding references in the objective reality – notional

words; -

those

having no references of their own in the objective reality; most of

them are used only as grammatical means to form up and frame

utterances – function words,

or grammatical words.

It is

commonly recognized that the notional parts of speech are nouns,

pronouns, numerals, verbs, adjectives, adverbs; the functional parts

of speech are articles, particles, prepositions, conjunctions and

modal words.

The

division of language units into notion and function words reveals the

interrelation of lexical and grammatical types of meaning. In

notional words the lexical meaning is predominant. In function words

the grammatical meaning dominates over the lexical one. However, in

actual speech the border line between notional and function words is

not always clear cut. Some notional words develop the meanings

peculiar to function words — e.g. seminotional words – to

turn, to get, etc.

Notional

words constitute the bulk of the existing word stock while function

words constitute a smaller group of words. Although the number of

function words is limited (there are only about 50 of them in Modern

English), they are the most frequently used units.

Generally

speaking, the problem of words’ classification into parts of speech

is far from being solved. Some words cannot find their proper place.

The most striking example here is the class of adverbs. Some language

analysts call it a ragbag, a dustbin

(Frank Palmer), Russian academician V.V.Vinogradov defined the class

of adverbs in the Russian language as мусорная

куча. It can be explained by the

fact that to the class of adverbs belong those words that cannot find

their place anywhere else. At the same time, there are no grounds for

grouping them together either. Compare: perfectly

(She speaks English perfectly)

and again

(He is here again).

Examples are numerous (all temporals). There are some words that do

not belong anywhere — e.g. after all.

Speaking about after all

it should be mentioned that this unit is quite often used by native

speakers, and practically never by our students. Some more striking

examples: anyway, actually, in fact.

The problem is that if these words belong nowhere, there is no place

for them in the system of words, then how can we use them correctly?

What makes things worse is the fact that these words are devoid of

nominative power, and they have no direct equivalents in the

Ukrainian or Russian languages. Meanwhile, native speakers use these

words subconsciously, without realizing how they work.

LECTURE

5: THE NOUN

1.General

characteristics.

The noun is

the central lexical unit of language. It is the main nominative unit

of speech. As any other part of speech, the noun can be characterised

by three criteria: semantic

(the meaning), morphological

(the form and grammatical catrgories) and syntactical

(functions, distribution).

Semantic

features of the noun. The noun possesses the grammatical meaning of

thingness, substantiality. According to different principles of

classification nouns fall into several subclasses:

-

According

to the type of nomination they may be proper

and common; -

According

to the form of existence they may be animate

and inanimate.

Animate nouns in their turn fall into human

and non-human. -

According

to their quantitative structure nouns can be countable

and uncountable.

This set of

subclasses cannot be put together into one table because of the

different principles of classification.

Morphological

features of the noun. In accordance

with the morphological structure of the stems all nouns can be

classified into: simple,

derived (

stem + affix, affix + stem – thingness);

compound (

stem+ stem – armchair

) and composite

( the Hague ). The noun has morphological categories of number and

case. Some scholars admit the existence of the category of gender.

Syntactic

features of the noun. The noun can be

used un the sentence in all syntactic

functions

but predicate. Speaking about noun combinability,

we can say that it can go into right-hand and left-hand connections

with practically all parts of speech. That is why practically all

parts of speech but the verb can act as noun determiners.

However, the most common noun determiners are considered to be

articles, pronouns, numerals, adjectives and nouns themselves in the

common and genitive case.

2.

The category of number

The grammatical category of

number is the linguistic representation of the objective category of

quantity. The number category is realized through the opposition of

two form-classes: the plural form :: the singular form. The category

of number in English is restricted in its realization because of the

dependent implicit grammatical meaning of

countableness/uncountableness. The number category is realized only

within subclass of countable nouns.

The

grammatical meaning of number may not coincide with the notional

quantity: the noun in the singular does not necessarily denote one

object while the plural form may be used to denote one object

consisting of several parts. The singular form may denote:

-

oneness

(individual separate object – a cat); -

generalization

(the meaning of the whole class – The

cat is a domestic animal); -

indiscreteness

(нерасчлененность or

uncountableness — money, milk).

The plural

form may denote:

-

the

existence of several objects (cats); -

the

inner discreteness (внутренняя

расчлененность, pluralia

tantum, jeans).

To sum it

up, all nouns may be subdivided into three groups:

-

The

nouns in which the opposition of explicit

discreteness/indiscreteness is expressed : cat::cats; -

The

nouns in which this opposition is not expressed explicitly but is

revealed by syntactical and lexical correlation in the context.

There are two groups here:

-

Singularia

tantum. It covers different groups of nouns: proper names, abstract

nouns, material nouns, collective nouns; -

Pluralia

tantum. It covers the names of objects consisting of several parts

(jeans), names of sciences (mathematics), names of diseases, games,

etc.

-

The

nouns with homogenous number forms. The number opposition here is

not expressed formally but is revealed only lexically and

syntactically in the context: e.g. Look!

A sheep is eating grass. Look! The sheep are eating grass.

3. The

category of case.

Case

expresses the relation of a word to another word in the word-group or

sentence (my sister’s coat). The category of case correlates with

the objective category of possession. The case category in English is

realized through the opposition: The Common Case :: The Possessive

Case (sister :: sister’s). However, in modern linguistics the term

“genitive case” is used instead of the “possessive case”

because the meanings rendered by the “`s” sign are not only those

of possession. The scope of meanings rendered by the Genitive Case is

the following :

-

Possessive

Genitive : Mary’s father – Mary has a father, -

Subjective

Genitive: The doctor’s arrival – The doctor has arrived, -

Objective

Genitive : The man’s release – The man was released, -

Adverbial

Genitive : Two hour’s work – X worked for two hours, -

Equation

Genitive : a mile’s distance – the distance is a mile, -

Genitive

of destination: children’s books – books for children, -

M

ixed

Group: yesterday’s paper

school cannot be reduced to one nucleus

John’s

word

To avoid

confusion with the plural, the marker of the genitive case is

represented in written form with an apostrophe. This fact makes

possible disengagement of –`s form from the noun to which it

properly belongs. E.g.: The

man I saw yesterday’s son,

where -`s is appended to the whole group (the so-called group

genitive). It may

even follow a word which normally does not possess such a formant, as

in somebody else’s

book.

There is no

universal point of view as to the case system in English. Different

scholars stick to a different number of cases.

-

There

are two cases. The Common one and The Genitive; -

There

are no cases at all, the form `s is optional because the same

relations may be expressed by the ‘of-phrase’: the

doctor’s arrival – the arrival of the doctor; -

There

are three cases: the Nominative, the Genitive, the Objective due to

the existence of objective pronouns me,

him, whom; -

Case

Grammar. Ch.Fillmore introduced syntactic-semantic classification of

cases. They show relations in the so-called deep structure of the

sentence. According to him, verbs may stand to different relations

to nouns. There are 6 cases:

-

Agentive

Case (A) John

opened the door; -

Instrumental

case (I) The key

opened the door;

John used the key to open the door; -

Dative

Case (D) John

believed that he would win (the case of the animate being affected

by the state of action identified by the verb); -

Factitive

Case (F) The key

was damaged ( the result of the action or state identified by the

verb); -

Locative

Case (L) Chicago is

windy; -

Objective

case (O) John stole

the book.

4. The

Problem of Gender in English

Gender

plays a relatively minor part in the grammar of English by comparison

with its role in many other languages. There is no gender concord,

and the reference of the pronouns he,

she, it is very

largely determined by what is sometimes referred to as ‘natural’

gender for English, it depends upon the classification of persons and

objects as male, female or inanimate. Thus, the recognition of gender

as a grammatical category is logically independent of any particular

semantic association.

According

to some language analysts (B.Ilyish, F.Palmer, and E.Morokhovskaya),

nouns have no category of gender in Modern English. Prof.Ilyish

states that not a single word in Modern English shows any

peculiarities in its morphology due to its denoting male or female

being. Thus, the words husband

and wife

do not show any

difference in their forms due to peculiarities of their lexical

meaning. The difference between such nouns as actor

and actress

is a purely lexical one. In other words, the category of sex should

not be confused with the category of sex, because sex is an objective

biological category.

It correlates with gender only when sex differences of living beings

are manifested in the language grammatically (e.g. tiger

– tigress).

Still, other scholars (M.Blokh, John Lyons) admit the existence of

the category of gender. Prof.Blokh states that the existence of the

category of gender in Modern English can be proved by the correlation

of nouns with personal pronouns of the third person (he,

she, it).

Accordingly, there are three genders in English: the neuter

(non-person) gender, the masculine gender, the feminine gender.

LECTURE

6: THE VERB.

1.General characteristics

Grammatically

the verb is the most complex part of speech. First of all it performs

the central role in realizing predication —

connection between situation in the utterance and reality. That is

why the verb is of primary informative significance in an utterance.

Besides, the verb possesses quite a lot of grammatical categories.

Furthermore, within the class of verb various subclass divisions

based on different principles of classification can befound.

Semantic

features of the verb. The verb possesses the grammatical meaning of

verbiality — the

ability to denote a process developing in time. This meaning is

inherent not only in the verbs denoting processes, but also in those

denoting states, forms of existence, evaluations, etc.

Morphological

features of the verb. The verb possesses the following grammatical

categories: tense, aspect, voice, mood, person, number, finitude and

phase. The common categories for finite and non-finite forms are

voice, aspect, phase and finitude. The grammatical categories of the

English verb find their expression in synthetical and analytical

forms. The formative elements expressing these categories are

grammatical affixes, inner inflexion and

function words.

Some categories have only synthetical forms (person,

number), others

— only analytical (voice).

There are also categories expressed by both synthetical and

analytical forms (mood, tense, aspect).

Syntactic features. The

most universal syntactic feature of verbs is their ability to be

modified by adverbs. The second important syntactic criterion is the

ability of the verb to perform the syntactic function of the

predicate. However, this criterion is not absolute because only

finite forms can perform this function while non-finite forms can be

used in any function but predicate. And finally, any verb in the form

of the infinitive can be combined with a modal verb.

2.

Classifications of English verbs

According to different

principles of classification, classifications can be morphological,

lexical-morphological, syntactical and functional.

A.

Morphological classifications..

I.

According to their stem-types all verbs fall into: simple (to

go), sound-replacive

(food —

to feed, blood —

to bleed), stress-replacive

(import

— to im port,

transport —

to transport, expanded

(with the help of suffixes and prefixes): cultivate,

justify, overcome, composite

(correspond to composite nouns): to

blackmail), phrasal:

to have a smoke, to give a smile

(they always have an ordinary verb as

an equivalent). 2.According

to the way of forming past tenses and Participle

II verbs can be regular

and irregular.

B.

Lexical-morphological classification is

based on the implicit grammatical meanings of the verb. According to

the implicit grammatical meaning of transitivity/intransitivity verbs

fall into transitive

and intransitive.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of

stativeness/non-stativeness verbs fall into stative

and dynamic.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of

terminativeness/non-terminativeness verbs fall into terminative

and durative.

This classification is closely connected with the categories of

Aspect and Phase.

C.

Syntactic

classifications. According to the nature of predication (primary and

secondary) all verbs fall into finite

and non-finite.

According to syntagmatic properties (valency) verbs can be of

obligatory

and optional valency,

and thus they may have some directionality or be devoid of any

directionality. In this way, verbs fall into the verbs of directed

(to see, to take, etc.)

and non-directed

action (to arrive, to drizzle, etc.):

Syntagmatic

classification of English verbs

(according

to prof.G.Pocheptsov)

Vobj. She shook her head

Vaddr. He phoned me

– V10 Vobj.-addr. She gave me

her pen

V11

– V15 Vadv. She behaved well

V1

V2 – V24 V16 – V24 Vobj.-adv. He put his hat

on the table

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

Updated on February 12, 2020

Grammatical meaning is the meaning conveyed in a sentence by word order and other grammatical signals. Also called structural meaning. Linguists distinguish grammatical meaning from lexical meaning (or denotation)—that is, the dictionary meaning of an individual word. Walter Hirtle notes that «a word expressing the same idea can fulfill different syntactic functions. The grammatical difference between the throw in to throw a ball and that in a good throw has long been attributed to a difference of meaning not of the lexical type described in dictionaries, but of the more abstract, formal type described in grammars» (Making Sense out of Meaning, 2013).

Grammatical Meaning and Structure

- «Words grouped together randomly have little meaning on their own, unless it occurs accidentally. For example, each of the following words has lexical meaning at the word level, as is shown in a dictionary, but they convey no grammatical meaning as a group:

a. [without grammatical meaning]

Lights the leap him before the down hill purple.

However when a special order is given to these words, grammatical meaning is created because of the relationships they have to one another.

a. [with grammatical meaning]

«The purple lights leap down the hill before him.» (Bernard O’Dwyer, Modern English Structures: Form, Function and Position. Broadview Press, 2006)

Number and Tense

- «Different forms of the same lexeme will generally, though not necessarily, differ in meaning: they will share the same lexical meaning (or meanings) but differ in respect of their grammatical meaning, in that one is the singular form (of a noun of a particular subclass) and the other is the plural form (of a noun of a particular subclass); and the difference between singular and plural forms, or—to take another example—the difference between the past, present and future forms of verbs, is semantically relevant: it affects sentence-meaning. The meaning of a sentence . . . is determined partly by the meaning of the words (i.e., lexemes) of which it is composed and partly by its grammatical meaning.» (John Lyons, Linguistic Semantics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 1996)

Word Class and Grammatical Meaning

- «Note . . . how word class can make a difference to meaning. Consider the following:

He brushed his muddy shoes. [verb]

He gave his muddy shoes a brush. [noun]

Changing from the construction with a verb to one with a noun involves more than just a change of word class in these sentences. There is also a modification of meaning. The verb emphasizes the activity and there is a greater implication that the shoes will end up clean, but the noun suggests that the activity was much shorter, more cursory and performed with little interest, so the shoes were not cleaned properly.

- «Now compare the following:

Next summer I am going to Spain for my holidays. [adverb]

Next summer will be wonderful. [noun]

According to traditional grammar, next summer in the first sentence is an adverbial phrase, while in the second it is a noun phrase. Once again, the change of grammatical category also entails some change of meaning. The adverbial phrase is an adjunct, a component bolted on to the rest of the sentence, and merely provides the temporal context for the whole utterance. On the other hand, use of the phrase as a noun in subject position renders it less circumstantial and less abstract; it is now the theme of the utterance and a more sharply delimited period in time.» (Brian Mott, Introductory Semantics and Pragmatics for Spanish Learners of English. Edicions Universitat Barcelona, 2009)

- Размер: 2.6 Mегабайта

- Количество слайдов: 89

ixed

ixed