The words

of language, depending on various formal and semantic features,

are divided into grammatically relevant sets or classes. The

traditional grammatical classes of words are called «parts

of speech». Since the

word is distinguished not only by grammatical, but also by

semantico-lexemic properties, some scholars refer to parts of speech

as «lexico-grammatical»

series of words, or as «lexico-grammatical categories.

It

should be noted that the term «part of speech» is purely

traditional and

conventional, it cannot be taken as in any way defining or

explanatory. This name was introduced in the grammatical

teaching of Ancient Greece, where the concept of the sentence was not

yet explicitly identified

in distinction to the general idea of speech, and where,

consequently, no

strict differentiation was drawn between the word as a vocabulary

unit and the word as a functional element of the sentence.

In

modern linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of

the three

criteria:

«semantic»,

«formal», and «functional».

The

semantic

criterion

presupposes the evaluation of the generalized meaning, which

is characteristic of all the subsets of words constituting a given

part of speech. This meaning is understood as the «categorial

meaning of

the part of speech».

The

formal criterion

provides for the exposition of the

specific inflexional and derivational (word-building) features of

allthe

lexemic subsets of a part of speech.

The

functional criterion

concerns the

syntactic role of words in the sentence typical of a part of speech.

The said

three factors of categorial characterization of words are

conventionally

referred to as, respectively, «meaning», «form»,

and «function».

In accord

with the described criteria, words on the upper level of

classification

are divided into notional

and functional,

which reflects their division

in the earlier grammatical tradition into changeable and

unchangeable.

To the

notional

parts of speech

of the English language belong the noun, the adjective, the numeral,

the pronoun, the verb, the adverb.

Contrasted against the

notional parts of speech are words of incomplete nominative

meaning and non-self-dependent, mediatory functions in the sentence.

These are functional parts of speech.

To

the basic functional

series of words

in English belong the article, the

preposition, the conjunction, the particle, the modal word, the

interjection.

Each part of speech after its

identification is further subdivided into subseries in accord with

various particular semantico-functional and formal features of the

constituent words. This subdivision is sometimes called

«subcategorization» of parts of speech.

Thus, nouns

are subcategorized into proper and common, animate and

inanimate, countable and uncountable, concrete and abstract,

etc.

Verbs

are subcategorized into fully predicative and partially predicative,

transitive and intransitive, actional and statal, purely nominative

and evaluative, etc.

Adjectives

are subcategorized into qualitative and relative, of constant

feature and temporary feature (the latter are referred to as

«statives» and identified by some scholars as a separate

part of speech under the heading of «category of state»),

factual and evaluative, etc.

The adverb,

the numeral, the pronoun are also subject to the corresponding

subcategorizations.

We have

drawn a general outline of the division of the lexicon into part

of speech classes developed by modern linguists on the lines of

traditional

morphology.

Alongside

the three-criteria principle of dividing the words into grammatical

(lexico-grammatical) classes, modern linguistics has developed

another, narrower principle

of word-class identification based on syntactic featuring of words

only.

The fact is

that the three-criteria principle faces a special difficulty in

determining the part of speech status of such lexemes as have

morphological characteristics of notional words, but are

essentially distinguished from notional words by their playing

the role of grammatical mediators in phrases and sentences. Here

belong, for instance, modal verbs

together with their equivalents — suppletive fillers, auxiliary

verbs, aspective

verbs, intensifying adverbs, determiner pronouns. This difficulty,

consisting in the intersection of heterogeneous properties in the

established

word-classes, can evidently be overcome by recognizing only one

criterion of the three as decisive.

Comparing

the syntactico-distributional classification of words with the

traditional part of speech division of words, one cannot but see the

similarity of the general schemes of the two: the opposition of

notional and

functional words, the four absolutely cardinal classes of notional

words (since numerals and pronouns have no positional functions of

their

own and serve as pro-nounal and pro-adjectival elements), the

interpretation of functional words as syntactic mediators and

their formal representation

by the list.

However,

under these unquestionable traits of similarity are distinctly

revealed

essential features of difference, the proper evaluation of which

allows us to make some important generalizations about the structure

of the

lexemic system of language.

As

a result of the undertaken analysis

we have obtained a foundation

for dividing the whole of the lexicon at the upper level of

classification

into three unequal parts.

The

first part of the lexicon forming an open set includes an

indefinitely large number of notional words which have a

complete nominative

function. In accord with the said function, these words can be re

ferred to as «names»: nouns as substance names, verbs as

process names, adjectives

as primary property names and adverbs as secondary property

names. The whole notional set is represented by the four-stage

derivational

paradigm of nomination.

The

second part of the lexicon forming a closed set includes substitutes

of names (pro-names). Here belong pronouns, and also broad-meaning

notional words which constitute various marginal subsets.

The

third part of the lexicon also forming a closed set includes

specifiers

of names. These are function-categorial words of various

servo-status.

Substitutes

of names (pro-names) and specifiers of names, while standing

with the names in nominative correlation as elements of the lexicon,

at

the same time serve as connecting links between the names within the

lexicon

and their actual uses in the sentences of living speech.

ЛИТЕРАТУРА:

-

Блох, М.Я.

Теоретическая грамматика английского

языка : Учеб. / М.Я. Блох. – 5–е изд.,

стер. – М. : Высш. шк., 2006. – 423 с. -

Блох, М.Я.

Теоретические основы грамматики :

учеб. / М.Я. Блох. – 3–е изд., испр. –

М. : Высш. шк., 2002. – 160 с. -

Blokh,

M.Y. A course in theoretical English grammar / M.Y. Blokh. –

M., 1983.

6

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

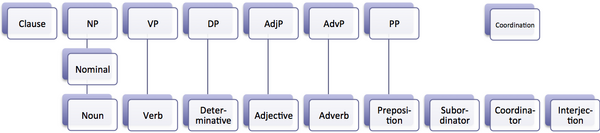

In English grammar, a word class is a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially their inflections and distribution. The term «word class» is similar to the more traditional term, part of speech. It is also variously called grammatical category, lexical category, and syntactic category (although these terms are not wholly or universally synonymous).

The two major families of word classes are lexical (or open or form) classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) and function (or closed or structure) classes (determiners, particles, prepositions, and others).

Examples and Observations

- «When linguists began to look closely at English grammatical structure in the 1940s and 1950s, they encountered so many problems of identification and definition that the term part of speech soon fell out of favor, word class being introduced instead. Word classes are equivalent to parts of speech, but defined according to strict linguistic criteria.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- «There is no single correct way of analyzing words into word classes…Grammarians disagree about the boundaries between the word classes (see gradience), and it is not always clear whether to lump subcategories together or to split them. For example, in some grammars…pronouns are classed as nouns, whereas in other frameworks…they are treated as a separate word class.» (Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker, Edmund Weiner, The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2014)

Form Classes and Structure Classes

«[The] distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning determines the first division in our classification: form-class words and structure-class words. In general, the form classes provide the primary lexical content; the structure classes explain the grammatical or structural relationship. Think of the form-class words as the bricks of the language and the structure words as the mortar that holds them together.»

The form classes also known as content words or open classes include:

- Nouns

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

The structure classes, also known as function words or closed classes, include:

- Determiners

- Pronouns

- Auxiliaries

- Conjunctions

- Qualifiers

- Interrogatives

- Prepositions

- Expletives

- Particles

«Probably the most striking difference between the form classes and the structure classes is characterized by their numbers. Of the half million or more words in our language, the structure words—with some notable exceptions—can be counted in the hundreds. The form classes, however, are large, open classes; new nouns and verbs and adjectives and adverbs regularly enter the language as new technology and new ideas require them.» (Martha Kolln and Robert Funk, Understanding English Grammar. Allyn and Bacon, 1998)

One Word, Multiple Classes

«Items may belong to more than one class. In most instances, we can only assign a word to a word class when we encounter it in context. Looks is a verb in ‘It looks good,’ but a noun in ‘She has good looks‘; that is a conjunction in ‘I know that they are abroad,’ but a pronoun in ‘I know that‘ and a determiner in ‘I know that man’; one is a generic pronoun in ‘One must be careful not to offend them,’ but a numeral in ‘Give me one good reason.'» (Sidney Greenbaum, Oxford English Grammar. Oxford University Press, 1996)

Suffixes as Signals

«We recognize the class of a word by its use in context. Some words have suffixes (endings added to words to form new words) that help to signal the class they belong to. These suffixes are not necessarily sufficient in themselves to identify the class of a word. For example, -ly is a typical suffix for adverbs (slowly, proudly), but we also find this suffix in adjectives: cowardly, homely, manly. And we can sometimes convert words from one class to another even though they have suffixes that are typical of their original class: an engineer, to engineer; a negative response, a negative.» (Sidney Greenbaum and Gerald Nelson, An Introduction to English Grammar, 3rd ed. Pearson, 2009)

A Matter of Degree

«[N]ot all the members of a class will necessarily have all the identifying properties. Membership in a particular class is really a matter of degree. In this regard, grammar is not so different from the real world. There are prototypical sports like ‘football’ and not so sporty sports like ‘darts.’ There are exemplary mammals like ‘dogs’ and freakish ones like the ‘platypus.’ Similarly, there are good examples of verbs like watch and lousy examples like beware; exemplary nouns like chair that display all the features of a typical noun and some not so good ones like Kenny.» (Kersti Börjars and Kate Burridge, Introducing English Grammar, 2nd ed. Hodder, 2010)

Select your language

Suggested languages for you:

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmelden

Words don’t only mean something; they also do something. In the English language, words are grouped into word classes based on their function, i.e. what they do in a phrase or sentence. In total, there are nine word classes in English.

Word class meaning and example

All words can be categorised into classes within a language based on their function and purpose.

An example of various word classes is ‘The cat ate a cupcake quickly.’

-

The = a determiner

-

cat = a noun

-

ate = a verb

-

a = determiner

-

cupcake = noun

-

quickly = an adverb

Word class function

The function of a word class, also known as a part of speech, is to classify words according to their grammatical properties and the roles they play in sentences. By assigning words to different word classes, we can understand how they should be used in context and how they relate to other words in a sentence.

Each word class has its own unique set of characteristics and rules for usage, and understanding the function of word classes is essential for effective communication in English. Knowing our word classes allows us to create clear and grammatically correct sentences that convey our intended meaning.

Word classes in English

In English, there are four main word classes; nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. These are considered lexical words, and they provide the main meaning of a phrase or sentence.

The other five word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are considered functional words, and they provide structural and relational information in a sentence or phrase.

Don’t worry if it sounds a bit confusing right now. Read ahead and you’ll be a master of the different types of word classes in no time!

| All word classes | Definition | Examples of word classification |

| Noun | A word that represents a person, place, thing, or idea. | cat, house, plant |

| Pronoun | A word that is used in place of a noun to avoid repetition. | he, she, they, it |

| Verb | A word that expresses action, occurrence, or state of being. | run, sing, grow |

| Adjective | A word that describes or modifies a noun or pronoun. | blue, tall, happy |

| Adverb | A word that describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or other adverb. | quickly, very |

| Preposition | A word that shows the relationship between a noun or pronoun and other words in a sentence. | in, on, at |

| Conjunction | A word that connects words, phrases, or clauses. | and, or, but |

| Interjection | A word that expresses strong emotions or feelings. | wow, oh, ouch |

| Determiners | A word that clarifies information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun | Articles like ‘the’ and ‘an’, and quantifiers like ‘some’ and ‘all’. |

The four main word classes

In the English language, there are four main word classes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Let’s look at all the word classes in detail.

Nouns

Nouns are the words we use to describe people, places, objects, feelings, concepts, etc. Usually, nouns are tangible (touchable) things, such as a table, a person, or a building.

However, we also have abstract nouns, which are things we can feel and describe but can’t necessarily see or touch, such as love, honour, or excitement. Proper nouns are the names we give to specific and official people, places, or things, such as England, Claire, or Hoover.

Cat

House

School

Britain

Harry

Book

Hatred

‘My sister went to school.‘

Verbs

Verbs are words that show action, event, feeling, or state of being. This can be a physical action or event, or it can be a feeling that is experienced.

Lexical verbs are considered one of the four main word classes, and auxiliary verbs are not. Lexical verbs are the main verb in a sentence that shows action, event, feeling, or state of being, such as walk, ran, felt, and want, whereas an auxiliary verb helps the main verb and expresses grammatical meaning, such as has, is, and do.

Run

Walk

Swim

Curse

Wish

Help

Leave

‘She wished for a sunny day.’

Adjectives

Adjectives are words used to modify nouns, usually by describing them. Adjectives describe an attribute, quality, or state of being of the noun.

Long

Short

Friendly

Broken

Loud

Embarrassed

Dull

Boring

‘The friendly woman wore a beautiful dress.’

Adverbs

Adverbs are words that work alongside verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. They provide further descriptions of how, where, when, and how often something is done.

Quickly

Softly

Very

More

Too

Loudly

‘The music was too loud.’

All of the above examples are lexical word classes and carry most of the meaning in a sentence. They make up the majority of the words in the English language.

The other five word classes

The other five remaining word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These words are considered functional words and are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

For example, prepositions can be used to explain where one object is in relation to another.

Prepositions

Prepositions are used to show the relationship between words in terms of place, time, direction, and agency.

In

At

On

Towards

To

Through

Into

By

With

‘They went through the tunnel.’

Pronouns

Pronouns take the place of a noun or a noun phrase in a sentence. They often refer to a noun that has already been mentioned and are commonly used to avoid repetition.

Chloe (noun) → she (pronoun)

Chloe’s dog → her dog (possessive pronoun)

There are several different types of pronouns; let’s look at some examples of each.

- He, she, it, they — personal pronouns

- His, hers, its, theirs, mine, ours — possessive pronouns

- Himself, herself, myself, ourselves, themselves — reflexive pronouns

- This, that, those, these — demonstrative pronouns

- Anyone, somebody, everyone, anything, something — Indefinite pronouns

- Which, what, that, who, who — Relative pronouns

‘She sat on the chair which was broken.’

Determiners

Determiners work alongside nouns to clarify information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun. It ‘determines’ exactly what is being referred to. Much like pronouns, there are also several different types of determiners.

- The, a, an — articles

- This, that, those — you might recognise these for demonstrative pronouns are also determiners

- One, two, three etc. — cardinal numbers

- First, second, third etc. — ordinal numbers

- Some, most, all — quantifiers

- Other, another — difference words

‘The first restaurant is better than the other.’

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses together within a sentence. There are three main types of conjunctions;

-

Coordinating conjunctions — these link independent clauses together.

-

Subordinating conjunctions — these link dependent clauses to independent clauses.

- Correlative conjunctions — words that work in pairs to join two parts of a sentence of equal importance.

For, and, nor, but, or, yet, so — coordinating conjunctions

After, as, because, when, while, before, if, even though — subordinating conjunctions

Either/or, neither/nor, both/and — correlative conjunctions

‘If it rains, I’m not going out.’

Interjections

Interjections are exclamatory words used to express an emotion or a reaction. They often stand alone from the rest of the sentence and are accompanied by an exclamation mark.

Oh

Oops!

Phew!

Ahh!

‘Oh, what a surprise!’

Word class: lexical classes and function classes

A helpful way to understand lexical word classes is to see them as the building blocks of sentences. If the lexical word classes are the blocks themselves, then the function word classes are the cement holding the words together and giving structure to the sentence.

In this diagram, the lexical classes are in blue and the function classes are in yellow. We can see that the words in blue provide the key information, and the words in yellow bring this information together in a structured way.

Word class examples

Sometimes it can be tricky to know exactly which word class a word belongs to. Some words can function as more than one word class depending on how they are used in a sentence. For this reason, we must look at words in context, i.e. how a word works within the sentence. Take a look at the following examples of word classes to see the importance of word class categorisation.

The dog will bark if you open the door.

The tree bark was dark and rugged.

Here we can see that the same word (bark) has a different meaning and different word class in each sentence. In the first example, ‘bark’ is used as a verb, and in the second as a noun (an object in this case).

I left my sunglasses on the beach.

The horse stood on Sarah’s left foot.

In the first sentence, the word ‘left’ is used as a verb (an action), and in the second, it is used to modify the noun (foot). In this case, it is an adjective.

I run every day

I went for a run

In this example, ‘run’ can be a verb or a noun.

Word Class — Key takeaways

-

We group words into word classes based on the function they perform in a sentence.

-

The four main word classes are nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs. These are lexical classes that give meaning to a sentence.

-

The other five word classes are prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are function classes that are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

-

It is important to look at the context of a sentence in order to work out which word class a word belongs to.

Frequently Asked Questions about Word Class

A word class is a group of words that have similar properties and play a similar role in a sentence.

Some examples of how some words can function as more than one word class include the way ‘run’ can be a verb (‘I run every day’) or a noun (‘I went for a run’). Similarly, ‘well’ can be an adverb (‘He plays the guitar well’) or an adjective (‘She’s feeling well today’).

The nine word classes are; Nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, interjections.

Categorising words into word classes helps us to understand the function the word is playing within a sentence.

Parts of speech is another term for word classes.

The different groups of word classes include lexical classes that act as the building blocks of a sentence e.g. nouns. The other word classes are function classes that act as the ‘glue’ and give grammatical information in a sentence e.g. prepositions.

The word classes for all, that, and the is:

‘All’ = determiner (quantifier)

‘That’ = pronoun and/or determiner (demonstrative pronoun)

‘The’ = determiner (article)

Final Word Class Quiz

Word Class Quiz — Teste dein Wissen

Question

A word can only belong to one type of noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is false. A word can belong to multiple categories of nouns and this may change according to the context of the word.

Show question

Question

Name the two principal categories of nouns.

Show answer

Answer

The two principal types of nouns are ‘common nouns’ and ‘proper nouns’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following is an example of a proper noun?

Show answer

Question

Name the 6 types of common nouns discussed in the text.

Show answer

Answer

Concrete nouns, abstract nouns, countable nouns, uncountable nouns, collective nouns, and compound nouns.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a concrete noun and an abstract noun?

Show answer

Answer

A concrete noun is a thing that physically exists. We can usually touch this thing and measure its proportions. An abstract noun, however, does not physically exist. It is a concept, idea, or feeling that only exists within the mind.

Show question

Question

Pick out the concrete noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

Pick out the abstract noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the difference between a countable and an uncountable noun? Can you think of an example for each?

Show answer

Answer

A countable noun is a thing that can be ‘counted’, i.e. it can exist in the plural. Some examples include ‘bottle’, ‘dog’ and ‘boy’. These are often concrete nouns.

An uncountable noun is something that can not be counted, so you often cannot place a number in front of it. Examples include ‘love’, ‘joy’, and ‘milk’.

Show question

Question

Pick out the collective noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the collective noun for a group of sheep?

Show answer

Answer

The collective noun is a ‘flock’, as in ‘flock of sheep’.

Show question

Question

The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is true. The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun as it is made up of two separate words ‘green’ and ‘house’. These come together to form a new word.

Show question

Question

What are the adjectives in this sentence?: ‘The little boy climbed up the big, green tree’

Show answer

Answer

The adjectives are ‘little’ and ‘big’, and ‘green’ as they describe features about the nouns.

Show question

Question

Place the adjectives in this sentence into the correct order: the wooden blue big ship sailed across the Indian vast scary ocean.

Show answer

Answer

The big, blue, wooden ship sailed across the vast, scary, Indian ocean.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 different positions in which an adjective can be placed?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective can be placed before a noun (pre-modification), after a noun (post-modification), or following a verb as a complement.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘The unicorn is angry’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘angry’ post-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘It is a scary unicorn’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘scary’ pre-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘purple’ and ‘shiny’?

Show answer

Answer

‘Purple’ and ‘Shiny’ are qualitative adjectives as they describe a quality or feature of a noun

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’?

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’ are evaluative adjectives as they give a subjective opinion on the noun.

Show question

Question

Which of the following adjectives is an absolute adjective?

Show answer

Question

Which of these adjectives is a classifying adjective?

Show answer

Question

Convert the noun ‘quick’ to its comparative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘quick’ is ‘quicker’.

Show question

Question

Convert the noun ‘slow’ to its superlative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘slow’ is ‘slowest’.

Show question

Question

What is an adjective phrase?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective phrase is a group of words that is ‘built’ around the adjective (it takes centre stage in the sentence). For example, in the phrase ‘the dog is big’ the word ‘big’ is the most important information.

Show question

Question

Give 2 examples of suffixes that are typical of adjectives.

Show answer

Answer

Suffixes typical of adjectives include -able, -ible, -ful, -y, -less, -ous, -some, -ive, -ish, -al.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a main verb and an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

A main verb is a verb that can stand on its own and carries most of the meaning in a verb phrase. For example, ‘run’, ‘find’. Auxiliary verbs cannot stand alone, instead, they work alongside a main verb and ‘help’ the verb to express more grammatical information e.g. tense, mood, possibility.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a primary auxiliary verb and a modal auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

Primary auxiliary verbs consist of the various forms of ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’ e.g. ‘had’, ‘was’, ‘done’. They help to express a verb’s tense, voice, or mood. Modal auxiliary verbs show possibility, ability, permission, or obligation. There are 9 auxiliary verbs including ‘could’, ‘will’, might’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are primary auxiliary verbs?

-

Is

-

Play

-

Have

-

Run

-

Does

-

Could

Show answer

Answer

The primary auxiliary verbs in this list are ‘is’, ‘have’, and ‘does’. They are all forms of the main primary auxiliary verbs ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’. ‘Play’ and ‘run’ are main verbs and ‘could’ is a modal auxiliary verb.

Show question

Question

Name 6 out of the 9 modal auxiliary verbs.

Show answer

Answer

Answers include: Could, would, should, may, might, can, will, must, shall

Show question

Question

‘The fairies were asleep’. In this sentence, is the verb ‘were’ a linking verb or an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

The word ‘were’ is used as a linking verb as it stands alone in the sentence. It is used to link the subject (fairies) and the adjective (asleep).

Show question

Question

What is the difference between dynamic verbs and stative verbs?

Show answer

Answer

A dynamic verb describes an action or process done by a noun or subject. They are thought of as ‘action verbs’ e.g. ‘kick’, ‘run’, ‘eat’. Stative verbs describe the state of being of a person or thing. These are states that are not necessarily physical action e.g. ‘know’, ‘love’, ‘suppose’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are dynamic verbs and which are stative verbs?

-

Drink

-

Prefer

-

Talk

-

Seem

-

Understand

-

Write

Show answer

Answer

The dynamic verbs are ‘drink’, ‘talk’, and ‘write’ as they all describe an action. The stative verbs are ‘prefer’, ‘seem’, and ‘understand’ as they all describe a state of being.

Show question

Question

What is an imperative verb?

Show answer

Answer

Imperative verbs are verbs used to give orders, give instructions, make a request or give warning. They tell someone to do something. For example, ‘clean your room!’.

Show question

Question

Inflections give information about tense, person, number, mood, or voice. True or false?

Show answer

Question

What information does the inflection ‘-ing’ give for a verb?

Show answer

Answer

The inflection ‘-ing’ is often used to show that an action or state is continuous and ongoing.

Show question

Question

How do you know if a verb is irregular?

Show answer

Answer

An irregular verb does not take the regular inflections, instead the whole word is spelt a different way. For example, begin becomes ‘began’ or ‘begun’. We can’t add the regular past tense inflection -ed as this would become ‘beginned’ which doesn’t make sense.

Show question

Question

Suffixes can never signal what word class a word belongs to. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. Suffixes can signal what word class a word belongs to. For example, ‘-ify’ is a common suffix for verbs (‘identity’, ‘simplify’)

Show question

Question

A verb phrase is built around a noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. A verb phrase is a group of words that has a main verb along with any other auxiliary verbs that ‘help’ the main verb. For example, ‘could eat’ is a verb phrase as it contains a main verb (‘could’) and an auxiliary verb (‘could’).

Show question

Question

Which of the following are multi-word verbs?

-

Shake

-

Rely on

-

Dancing

-

Look up to

Show answer

Answer

The verbs ‘rely on’ and ‘look up to’ are multi-word verbs as they consist of a verb that has one or more prepositions or particles linked to it.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a transition verb and an intransitive verb?

Show answer

Answer

Transitive verbs are verbs that require an object in order to make sense. For example, the word ‘bring’ requires an object that is brought (‘I bring news’). Intransitive verbs do not require an object to complete the meaning of the sentence e.g. ‘exist’ (‘I exist’).

Show question

Answer

An adverb is a word that gives more information about a verb, adjective, another adverb, or a full clause.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 ways we can use adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

We can use adverbs to modify a word (modifying adverbs), to intensify a word (intensifying adverbs), or to connect two clauses (connecting adverbs).

Show question

Question

What are modifying adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

Modifying adverbs are words that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They add further information about the word.

Show question

Question

‘Additionally’, ‘likewise’, and ‘consequently’ are examples of connecting adverbs. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

True! Connecting adverbs are words used to connect two independent clauses.

Show question

Question

What are intensifying adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

Intensifying adverbs are words used to strengthen the meaning of an adjective, another adverb, or a verb. In other words, they ‘intensify’ another word.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are intensifying adverbs?

-

Calmly

-

Incredibly

-

Enough

-

Greatly

Show answer

Answer

The intensifying adverbs are ‘incredibly’ and ‘greatly’. These strengthen the meaning of a word.

Show question

Question

Name the main types of adverbs

Show answer

Answer

The main adverbs are; adverbs of place, adverbs of time, adverbs of manner, adverbs of frequency, adverbs of degree, adverbs of probability, and adverbs of purpose.

Show question

Question

What are adverbs of time?

Show answer

Answer

Adverbs of time are the ‘when?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘when is the action done?’ e.g. ‘I’ll do it tomorrow’

Show question

Question

Which of the following are adverbs of frequency?

-

Usually

-

Patiently

-

Occasionally

-

Nowhere

Show answer

Answer

The adverbs of frequency are ‘usually’ and ‘occasionally’. They are the ‘how often?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘how often is the action done?’.

Show question

Question

What are adverbs of place?

Show answer

Answer

Adverbs of place are the ‘where?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘where is the action done?’. For example, ‘outside’ or ‘elsewhere’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are adverbs of manner?

-

Never

-

Carelessly

-

Kindly

-

Inside

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘carelessly’ and ‘kindly’ are adverbs of manner. They are the ‘how?’ adverbs that answer the question ‘how is the action done?’.

Show question

Discover the right content for your subjects

No need to cheat if you have everything you need to succeed! Packed into one app!

Study Plan

Be perfectly prepared on time with an individual plan.

Quizzes

Test your knowledge with gamified quizzes.

Flashcards

Create and find flashcards in record time.

Notes

Create beautiful notes faster than ever before.

Study Sets

Have all your study materials in one place.

Documents

Upload unlimited documents and save them online.

Study Analytics

Identify your study strength and weaknesses.

Weekly Goals

Set individual study goals and earn points reaching them.

Smart Reminders

Stop procrastinating with our study reminders.

Rewards

Earn points, unlock badges and level up while studying.

Magic Marker

Create flashcards in notes completely automatically.

Smart Formatting

Create the most beautiful study materials using our templates.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We’ll assume you’re ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

Privacy & Cookies Policy

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

3) Lexical and Grammatical Word Classes

Compound Words

We know, that lexical morphemes carry the main meaning (or significance) of the word it belongs to. The morpheme ‘ready’ in ‘readiness’ carries the meaning of the word, as does ‘bound’ in ‘unbound’, or ‘cran’ in ‘cranberry’. These morphemes, because they carry the lexical meaning, are lexical morphemes.

Grammatical morphemes can become attached to lexical morphemes. The ‘ing’ in ‘singing’ carries no lexical meaning, but it does provide a grammatical context for the lexical morpheme. It tells us that the ‘sing’ is ‘ing’ (as in ‘on-going’). In the same way, the morpheme ‘ely’ in ‘timely’ carries no meaning, but it does turn the noun ‘time’ into a word more frequently used as an adverb. Time the thing becomes the description of an action – as in ‘his intervention was timely’.

Of course, as with so many things in life, these definitions are by no means uncomplicated. For example, if we were to consider the lexical meaning of the words ‘stand’ and ‘under’, then they would be distinctive and straightforward. ‘Stand’, means to be upright, and ‘under’ means to be beneath something. However, when we put these two lexical morphemes together (although technically ‘under’ is actually a preposition), we get the word ‘understand’ which has an entirely different lexical meaning.

The combining of morphemes in order to create a new lexis is known as compounding, and words which are formed by the combination of such morphemes are known as compound words. Compound words do not necessarily have to be the consequence of combining lexical morphemes alone. Certainly, the lexical morphemes ‘earth’ and ‘quake’ combined create ‘earthquake’, but the combination of grammatical morpheme ‘to’ and the lexical morpheme ‘day’ creates ‘today’.

Here is a list of compound words. See if you can identify the lexical and grammatical morphemes:

|

lifetime |

elsewhere |

upside |

grandmother |

|

cannot |

backbone |

fireworks |

passport |

|

together |

become |

became |

sunflower |

|

crosswalk |

basketball |

scapegoat |

superstructure |

|

moonlight |

football |

railroad |

rattlesnake |

|

anybody |

weatherman |

throwback |

skateboard |

|

meantime |

earthquake |

everything |

peppermint |

|

sometimes |

also |

backward |

schoolhouse |

|

butterflies |

upstream |

nowhere |

bypass |

|

fireflies |

because |

somewhere |

spearmint |

|

something |

another |

somewhat |

airport |

|

anyone |

today |

himself |

grasshopper |

|

inside |

themselves |

playthings |

footprints |

|

therefore |

uplift |

without |

homemade |

Whether these compound words are composed of grammatical or lexical morphemes, the compound itself is almost always lexical. ‘Therefore’ is composed of two morphemes which in some ways can both be considered grammatical, but the compound carries a lexical meaning of ‘as a consequence of’.

Word Classes

It is useful to be able to distinguish between lexical and grammatical morphemes, because by doing so we are able to understand that words are constructed using specific mechanisms. Understanding those mechanisms means that we understand more clearly not only how we use words today, but how new words are formed.

If this is true of the morphemes in relation to the construction of words, then is is true also of words in relation to the construction of sentences. This is our next topic: the categorisations of words.

Words are divided into various classes (or ‘parts of speech’), each of which has a specific function in relation to creating meaning within sentences. The first and easiest distinction is that between open-class words (or lexical words) and closed-class words (or grammatical words).

Open-class words, or Lexical words

Open-class words, as Leslie Jeffries writes, are “those which contain the main semantic information in a text, and they fall into the four main lexical word classes: noun, verb, adjective and adverb” (Jeffries, 2006, p. 83). Stott and Chapman, in their book Grammar and Writing (2001) define these classes as:

- Verb: A word or phrase which expresses the action, process or state in the clause (e.g. I’m eating my favourite meal right now; I will go to that football match; I went quietly)

- Adverb: Single words that modify verbs by adding to their meaning (e.g. The choir sang sweetly). Words or phrases that modify or give extra definition to the verb in terms of place, manner and time (e.g. I’m eating my favourite meal right now; I’m eating my favourite meal in my favourite restaurant), are often referred to as adverbial.

- Noun: Words that names persons / places / things or abstractions (e.g. Edward, Tanzania, guitar, happiness). In earlier centuries all nouns in the English language were given a capital letter. In German, they still do the same. In English now, only proper nouns are given capital letters.

- Adjective: Words that modify nouns by adding to their meanings (e.g. That was a long film). Most adjectives have comparative (I’m glad it wasn’t any longer) and Superlative forms (It was the longest film I’ve ever seen).

They classes are referred to as open-class because “they are open-ended and can be added to readily” (Jeffries, 2006, p. 83), but they are also often referred to as lexical words because they carry a lexicial meaning (sometimes they are even referred to as semantic words, for the same reason). Sara Thorne goes on to say:

New words can be added to nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs as they become necessary, developing language to match changes in the society around us. The computer age, for example, has introduced new words like hardware, software, CD-Rom and spreadsheet; the 1980s introduced words like Rambo, kissogram and wimp; the 1990s introduced words like babelicious, alcopop and e-verdict; and the twenty-first century words like bling, chav, sudoko, bluetooth, chuggers (‘charity muggers’), mediatrics (‘media dramatics’ i.e. a story created from nothing), and doorstepping (journalists catching celebrities on their doorsteps to question them about incidents they would prefer not to discuss). Open-class words are often called lexical words and have a clearly definable meaning. (Thorne, 2008. p. 4)

Closed-class words, or Grammatical words

If open-class words tend to change frequently, then closed-class words tend not to change very often. Closed-class or grammatical words (sometimes referred to as function words) have less meaning than open-class or lexical words, but do useful jobs in language. They are the ‘little words’ that act as the glue, or connectors, inside a sentence. Without them, lexical words might still carry meaning but they do not make as much sense.

Grammatical words include articles, prepositions, conjunctions and pronouns.

- Articles: There are only two articles in English: the definite article, the, and the indefinite article a(n) (Jeffries, 2006. p. 96).

- Prepositions: Define the relationships that exist between elements. This includes relationships of place (at, on, by, opposite), of direction (towards, past, out, of, to, through), of time (at, before, in, on), of comparison (as, like), of source (from, out of), and of purpose (for) (Thorne, 2008. p. 20). Prepositions are by no means uncomplicated – you will have noticed from this list that the word ‘at’ can function as both a preposition of place and of time, depending on its contexts.

- Conjuntions: The function of conjunctions is to link together elements of sentences and phrases. They come in two forms. Co-ordinating conjunctions are words that join two clauses in a sentence, where each clause is of equal importance (i.e., ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘either’, ‘or’, ‘neither’, ‘nor’). Subordinating conjunctions are words that link sentences where one half is a consequence of the other (‘although’, ‘as’, ‘because’, ‘if’, ‘since’, ‘that’, ‘though’, ‘until’, ‘where’, ‘when’, ‘while’, etc.).

- Pronouns: Pronouns come in two forms. Firstly, the pronoun itself, where words are “used instead of a noun or noun phrase (e.g. it, he, who, theirs)”. Secondly, there is the personal pronoun, in which “[w]ords identify speakers, addressees and others (I, you, she, it, we, they)” (Stott and Shapman, 2001).

What is the significance of word classes?

Note: I am indebted to Dr. Geoffrey Finch for his help with much of this next section, to which I have added some additional notes and material. This means that some parts of this section have doubtless either already appeared in one of Dr. Finch’s book, or will imminently do so – but without the details I have been unable to reference them properly. See here for published works, and buy them all — ‘cos they’re great.

Word classes are important in the acquisition of language because they enable us to construct sentences with a maximum of economy. Knowing that only a verb can complete the following sentence:

|

loved |

||

|

The boy |

………….. |

the dog |

|

hit |

or an adverb the one below,

|

badly |

|

|

The boy wrote the essay very |

……….. |

|

easily |

means that we don’t have to try out every word in our mental lexicon to see whether it will fit or not.

So classifications of words and grammar enable us to communicate much more efficiently. Not only this, such systems enable us to communicate with much more variety. Humans simply could not memorise a lexicon which contained a different word for every thing they wanted to express. This means that there are only two options – either make do with a limited range of expression, or develop a system which allows for individual words to mean more than one thing. Word classes are part of that very system – as we shall discover more of in a moment.

Bauer, Holmes and Warren (2006) argue that word class systems are like the assembly instructions for language:

Kit-sets for furniture (and other construction toys for older children) generally come with a parts list and a set of instructions. If the parts list of a language is the set of words used by that language, then the grammar is the instruction set. If your build-it-yourself bookcase arrives with a parts list and no instructions, then the construction of a well-formed piece of furniture may be more difficult, if not impossible. If we have a set of words but no grammar then the construction of well-formed sentences is similarly compromised.

The language instruction set is useful not only in constructing sentences, but also in deconstructing them, in understanding what someone is saying to us. And understanding what someone is saying is not just understanding the words they use. Compare, for instance, Tama would like to speak to you and you would like to speak to Tama. These sentences share the same words, and the result of the situation expressed might be the same (i.e. the people referred to as you and Tama get together to talk), but our understanding of these sentences involves not just knowing what each word means but also recognizing how the words, as components of sentences, are combined. After all, Max loves Alice does not mean Alice loves Max. Success in communicating the message depends on speakers and listeners working with the same instruction set. It is this type of shared knowledge which constitutes part at least of what we call grammar. (Bauer, Holmes and Warren, 2006. p. 104)

Problems with classifications

The criteria by which linguists assign words to particular classes, however, are less certain. Most people if asked to say what a verb or a noun are rely on what is called ‘notional’ criteria. These are broadly semantic in origin. They include referring to a verb as a ‘doing word’, i.e. a word that denotes an action of some sort (go, destroy, eat), and a noun as a ‘naming word’, i.e. one that denotes an entity or thing (car, cat, hill). Similarly, adjectives are said to denote states or qualities (ill, happy, rich), and adverbs, the manner in which something is done (badly, slowly, well).

As a rule of thumb this works reasonably well, but it’s not subtle enough to capture the way in which word classification essentially works. Not all verbs are ‘doing’ words. The verbs ‘to be’, and ‘to have’ clearly aren’t. And neither are all nouns necessarily ‘things’. Nouns such as ‘advice’, and ‘consequence’ are difficult to conceive as entities. We’re forced to call them ‘abstract’ nouns, a recognition that in some way they are not typical. Indeed, notional criteria only work for prototypical class members, but there are many others for which such criteria are not adequate. The word ‘assassination’, for example, seems like a verb since it describes a process or action, but it is in fact a noun.

The Lawlessness of English

The English language is flexible. It has, over the centuries developed from a corruption of Latin — the twisting and changing of ‘proper’ Latin with local jargon and slang. “From at least the time of Shakespeare”, Measham says, “the English language has not been overly hampered by rules” (Measham, 1965. P. 83).

To use an example from Measham — look at these three sentences:

- Gardening is a good way of getting blisters.

- I was gardening at the time the wall fell down.

- I had on my gardening boots.

The word ‘gardening’ appears three times. But does it serve the same function each time?

- Gardening is a good way of getting blisters

here ‘gardening’ functions as a noun.

- I was gardening at the time the wall fell down

here ‘gardening’ functions as a verb: it describes an action.

- I had on my gardening boots

here ‘gardening’ functions as an adjective.

Of course, for native English speakers the meaning of these sentences might appear plain, despite the fact that the same word operates in very different functions.

So how can we classify words at all?

The only secure way to assign words into word classes is on the basis of how they behave in the language. If a word behaves in a way characteristic of a noun, or a verb, then it’s safe to call it one. This, of course, means recognising that words can belong to more than one class. It also means recognising that words may be more or less noun-like or verb-like in behaviour.

Word classes are similar to family groupings in that some members are more recognisably part of their class than others. Basic to word behaviour are two sets of criteria, namely, the morphological, and the syntactic. Morphological criteria, as we have seen, are concerned with the structure of words. Important here are such processes as inflection. Most verbs will inflect to show tense (show + ed), most nouns to indicate plurality (bat + s), and many adjectives to show the comparative and superlative (fat > fatter > fattest). But there is no one criterion which all words in a particular class will obey. As a consequence, linguists also use syntactic criteria, in particular, the distribution of a word in an individual string. This is the topic we will be considering in my next post: Whereabouts a word can occur in a phrase or sentence is an important indication of its class.