As you learn German, have you ever noticed how the German language doesn’t have a one-word equivalent for “a,” or “the?”

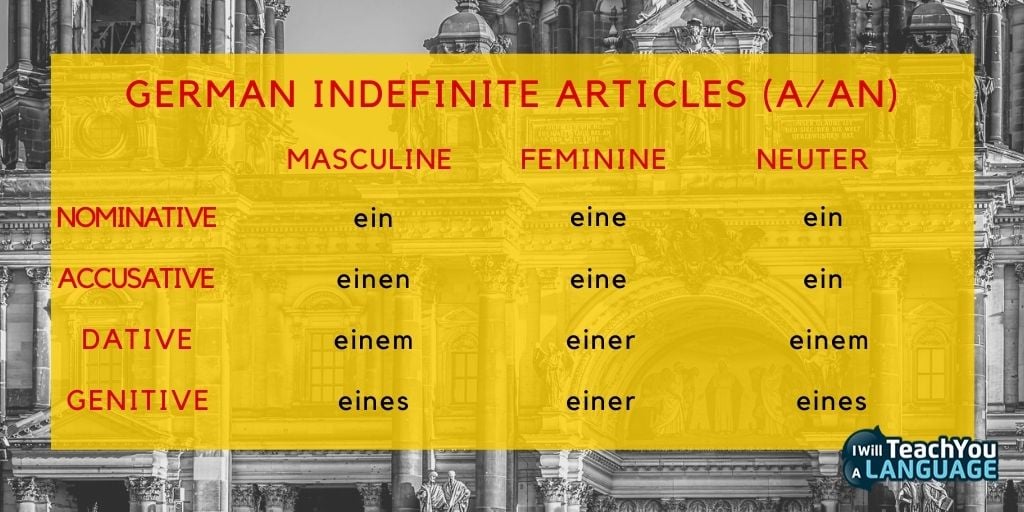

Maybe you’ve noticed a variety of possibilities to translate “a” such as ein, eine, einer, einen, or einem. It gets even more complicated when translating “the.” When do you use der, die, das, den, or dem?

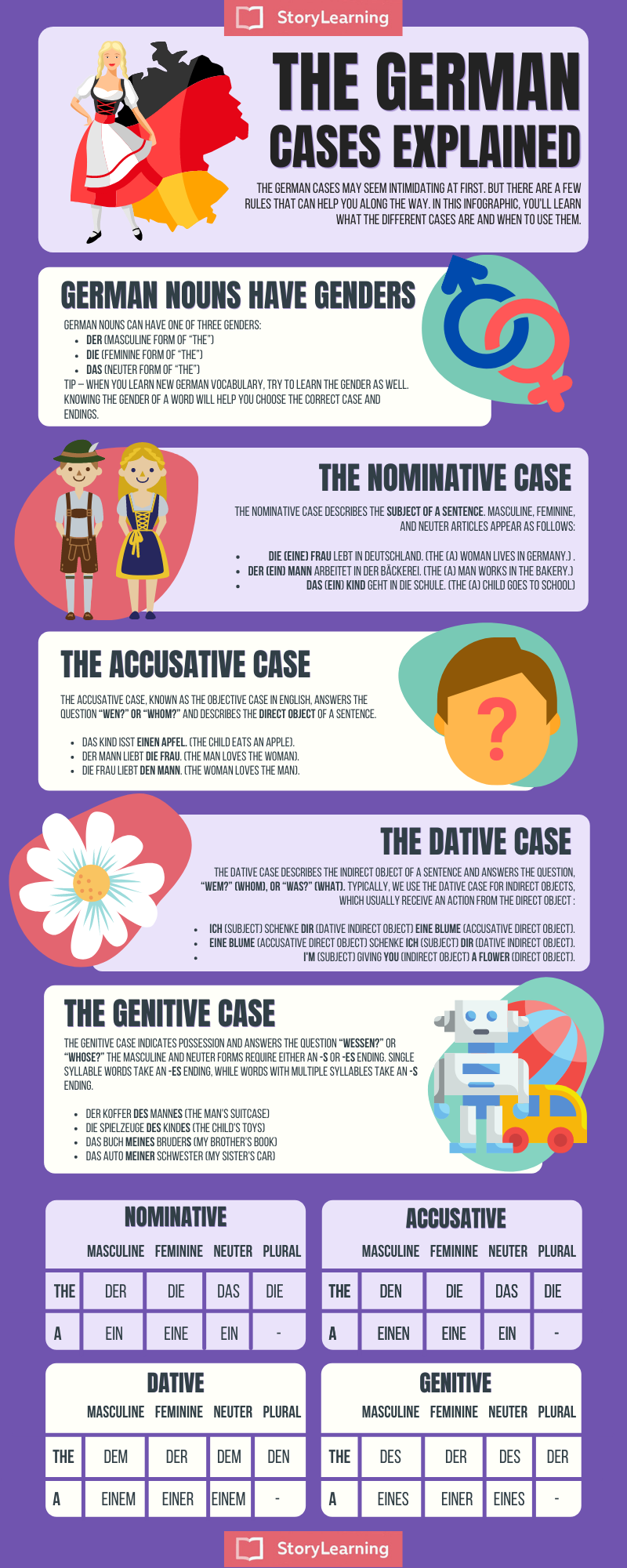

The German cases may seem intimidating at first. But there are a few rules that can help you along the way.

In this article you’ll learn what the different cases are and when to use them. By the end of this post, you’ll have a clear understanding of the German case system.

By the way, if you want to learn German fast and have fun while doing it, my top recommendation is German Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With German Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn German cases and other tricky grammar naturally through stories. It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

In the meantime, back to the subject at hand…

So let’s dive into everything you’ll ever need to know to understand the cases in German.

Check out the infographic below for a quick overview of what we’ll cover.

1. German Nouns Have Genders

The first thing to know about German nouns is that they have genders. For native English speakers, this is an entirely new concept.

For example:

- the dog: der Hund

- the cat: die Katze

- the horse: das Pferd

As you can see, German nouns can have one of three genders:

- der (masculine form of “the”)

- die (feminine form of “the”)

- das (neuter form of “the”)

Tip – when you learn new German vocabulary, try to learn the gender as well. Knowing the gender of a word will help you choose the correct case and endings.

In addition to having a gender, a noun’s article changes depending on if it’s a subject, object, direct object, or indirect object. The four German cases are nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive.

- The nominative case is used for sentence subjects. The subject is the person or thing that does the action. For example, in the sentence, “the girl kicks the ball”, “the girl” is the subject.

- The accusative case is for direct objects. The direct object is the person or thing that receives the action. So in “the girl kicks the ball”, “the ball” is the direct object.

- The dative case is for indirect objects. The indirect object is the person or thing who “gets” the direct object. So in the sentence “The girl kicks the ball to the boy”, “the boy” is the indirect object.

- The genitive case is used to express possession. In English, we show possession with an apostrophe + s “the girl’s ball”.

Let’s look at each case in more detail.

2. The Nominative Case (Der Nominativ)

The nominative case answers the question, “wer?” or “who?”

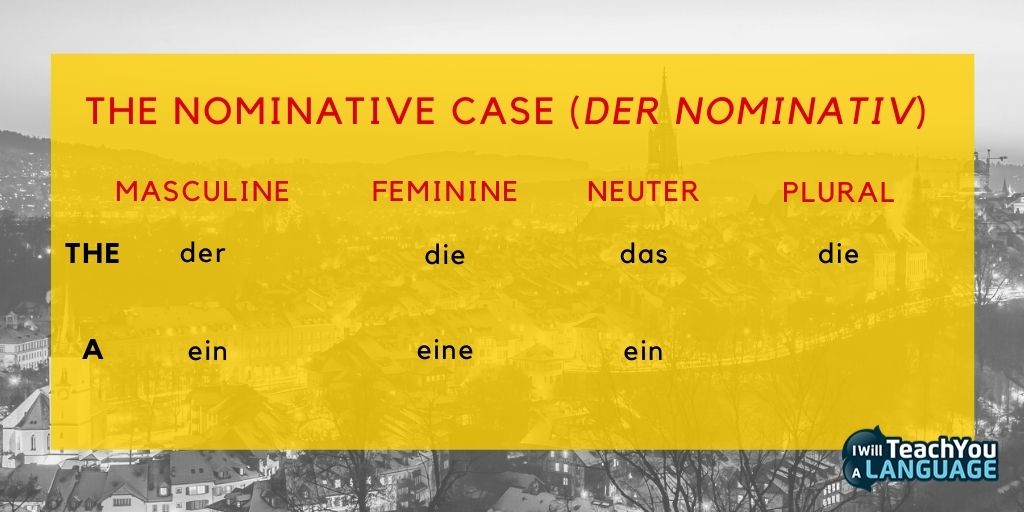

In both German and English, the nominative case describes the subject of a sentence. Masculine, feminine, and neuter articles appear as follows:

You can see the nominative in context in these examples:

- Die (Eine) Frau lebt in Deutschland. (The (a) woman lives in Germany.) In this example, Die Frau, or the woman, is the subject of the sentence.

- Der (Ein) Mann arbeitet in der Bäckerei. (The (a) man works in the bakery.) The man is the subject of this sentence and takes the nominative case.

- Das (Ein) Kind geht in die Schule. (The (a) child goes to school.) The subject, the child, takes the nominative case.

3. The Accusative Case (Der Akkusativ)

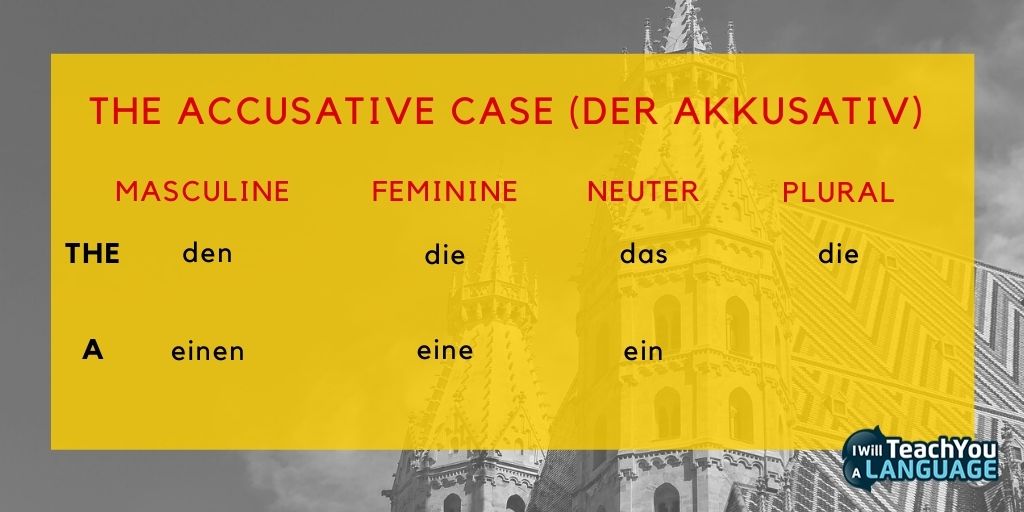

The accusative case, known as the objective case in English, answers the question “wen?” or “whom?” and describes the direct object of a sentence.

Let’s see how the masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns change in the accusative case.

As you probably noticed, only the masculine articles change in the accusative case. Let’s look at a few simple examples:

- Das Kind isst einen Apfel. (The child eats an apple). In this sentence, einen Apfel is the direct object in the accusative case. Das Kind is the subject and takes the nominative case.

- Der Mann liebt die Frau. (The man loves the woman). Here, die Frau is the direct object in the accusative case. Der Mann is the subject in the nominative case.

- Die Frau liebt den Mann. (The woman loves the man). Den Mann is the direct object in this sentence and takes the accusative case. Die Frau is the subject and takes the nominative case.

There are also a few prepositions that always take the accusative case:

- durch (through)

- bis (until)

- für (for)

- ohne (without)

- entlang (along)

- gegen (against)

- um (around)

A Quick Note On Word Order

In English, we use word order to clarify which nouns are subjects, objects, and indirect objects. But German allows for more freedom of word placement, as long as we use the correct case.

Following are a few examples of the accusative case:

- Der Mann streichelt den Hund. (The man pets the dog.)

- Er streichelt ihn. (He pets him, the dog.)

- Den Hund streichelt der Mann. (The man pets the dog.)

- Streichelt der Mann den Hund? (Is the man petting the dog?)

- Streichelt den Hund der Mann? (Is the man petting the dog?)

As you can see, the meaning of the sentence is derived from the case, rather than the word order. This concept is somewhat different in English, so it can take some practice to get used to.

4. The Dative Case (Der Dativ)

The dative case describes the indirect object of a sentence in German and English and answers the question, “wem?” (whom), or “was?” (what).

The dative case is slightly more complicated than the accusative. Take a look at the dative article forms to see if you can spot the differences:

Typically, we use the dative case for indirect objects, which usually receive an action from the direct object (in the accusative case). As with the other cases, word order is flexible, as long as you use the correct case. For example:

- Ich (subject) schenke dir (dative indirect object) eine Blume (accusative direct object).

- Eine Blume (accusative direct object) schenke ich (subject) dir (dative indirect object).

- I’m (subject) giving you (indirect object) a flower (direct object).

Several prepositions take the dative case:

- aus (out)

- auβer (besides)

- bei (next to)

- mit (with)

- nach (after)

- seit (since)

- von (from)

- zu (to)

- gegenüber (opposite)

And some German verbs always take the dative case. These verbs are:

- antworten (to answer)

- danken (to thank)

- glauben (to believe)

- helfen (to help)

- gehören (belong to)

- gefallen (to like)

5. The Genitive Case (Der Genitiv)

The genitive case indicates possession and answers the question “wessen?” or “whose?” You’ll see the genitive case most often in written German. In spoken German, you’ll hear von (from)and the dative case instead of the genitive case.

For example:

- Das Haus meines Vaters (My father’s house). The genitive case is common in written German.

- Das Haus von meinem Vater (My father’s house). The dative case often replaces the genitive case in spoken German.

Below are the definite and indefinite article changes for the genitive case.

The masculine and neuter forms require either an -s or -es ending. Single syllable words take an -es ending, while words with multiple syllables take an -s ending. Here are a few examples.

- Der Koffer des Mannes (The man’s suitcase)

- Die Spielzeuge des Kindes (The child’s toys)

- Das Buch meines Bruders (My brother’s book)

- Das Auto meiner Schwester (My sister’s car)

Just as the dative case, certain prepositions always take the genitive case:

- anstatt (instead of)

- außerhalb (outside of)

- innerhalb (inside of)

- trotz (despite)

- während (during)

- wegen (because of)

But in spoken German, Germans sometimes use the dative case with these genitive prepositions.

Overview Of The German Cases

It’s easier to choose the correct case when you’re familiar with the changes of the definite (der, die, das) and indefinite articles (ein, eine, ein). I’ve created these charts to remind you of the different changes you’ve seen so far.

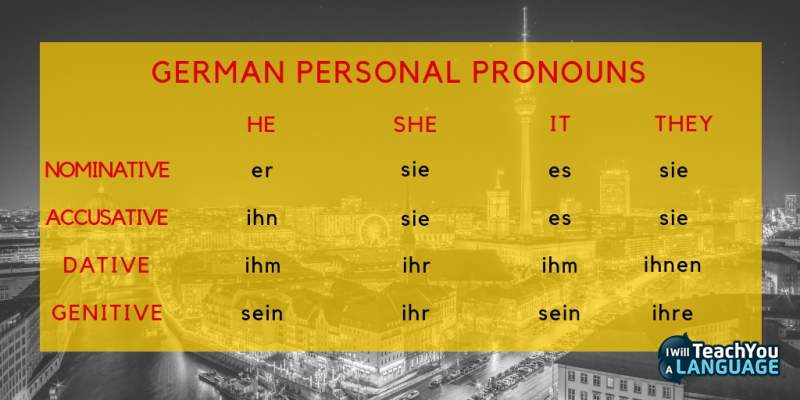

Just as the definite and indefinite articles change, so do personal pronouns. However, this is also the same in English, as “I” changes to “me” or “my”. For example:

- Ich bin genervt (I am annoyed)

- Das nervt mich (That annoys me)

The following chart makes it simple to decline German pronouns in all four cases.

Once you become familiar with the articles and noun endings of different cases, you’ll be able to clearly identify the subject, object, and direct object of a sentence.

The flexibility of the German language allows you to change the word order in sentences without changing the meaning.

German Cases Explained: The Not So Strange Case Of The German Cases

A few final tips will make it easy to remember all the German case rules. Ask yourself the following questions to figure out which case to use:

- What gender does the noun have? Is it masculine, feminine, or neuter?

- Is the noun part of a prepositional phrase? If so, is the preposition accusative, dative, or genitive? If not, examine the function of the noun. Which noun is the subject, object, direct object, and indirect object?

- Which article corresponds to the case in question? If you’re not sure in the beginning, use a case table like the ones in this post to choose the correct article form.

You don’t need to memorise all the different article forms for each case or each specific preposition in the beginning.

Begin with the basics and gradually build up your understanding through practice and exposure. And make sure you’re listening to or reading lots of German to expose yourself to the different cases in context.

Every German language learner has difficulty with the cases at first.

But, with practice, you’ll find it becomes second nature in no time at all.

Master German Grammar The Natural Way

If you like the idea of reading lots of German material to master the grammar, then German Grammar Hero is for you.

In this programme, instead of pouring over verb tables and memorising grammar rules, you read and immerse yourself in a compelling story.

The grammar emerges naturally as you read, instead of the traditional school method where you learn the rules out of context and struggle to use them in real life.

That way you can actually speak German with accuracy and confidence, rather than translating in your head from English every time you open your mouth.

Grammar Hero is perfect for low intermediate to intermediate learners. If that’s you then click here to find out more and become a grammar hero!

Over to you – has this post helped you to better understand how to learn and use the German cases? Which other aspects of German grammar do you find tricky? Let’s continue the conversation below in the comments.

The first question you might have about learning German is how to pronounce the German articles “the”, “a” and “an”. In German, however, the choices are a little more complex. Instead of two options, you have 11: der, die, das, den, dem, des, ein, eine, einen, einem, and eines. In spite of this, you should not be intimidated by these articles. There are many guidelines that can assist you in making the right choice.

German articles are used in a similar manner to English articles, a and the. In spite of this, they are declined differently depending on the number, gender, and case of their nouns. Based on the number, the case, and the gender of the noun, the inflected form is determined. As with adjectives and pronouns, German articles have the same plural forms for all three genders.

It is important to recognize that German articles and pronouns in the genitive and dative cases clearly indicate ownership and giving without the use of additional words (in fact, this is their function), which can cause English-speaking learners to have difficulty understanding German sentences. For the dative case, the gender matches that of the receiver (not that of the object) and for the genitive case, the gender matches that of the owner.

A genitive form of another pronoun may be used in place of the regular possessive pronouns in some circumstances (e.g. relative clauses). The equivalent English expressions would be, “The king whose army Napoleon had defeated” or “The Himalayas, the highest parts of which have not yet been explored”. As far as number and gender are concerned, they are in agreement with the possessor. In contrast to other pronouns, they do not have any strength. There will be a strong ending to any adjective following them in the phrase.

As with most other aspects of the German language, there are several systematic approaches to learning the different articles. Here is your chance to discover them!

Articles: What Do They Mean?

In other words, articles are words such as “a,” “an,” and “the.” They are used to introduce nouns, which can be people, places, or objects. In English, articles are simple. In contrast, there are over a dozen article options available in German.

Article Declension: How To Choose The Right One

Fortunately, German articles can provide a great deal of additional information. In addition, there are a number of effective methods for remembering which one to use and at what time.

An article in German, for example, can provide additional information about the noun:

- Number – In German, articles indicate whether a noun is singular or plural.

- Gender – An article in German indicates the gender of the noun it precedes.

- Case – Additionally, you can determine which words are the subject, direct object, and indirect object. You will be able to change the word order without changing the meaning if you use the correct articles! We do not have this luxury in English. To make sense, we must follow a specific sentence structure.

This guide will teach you how to correctly use German articles and improve your fluency.

The Difference Between Definite And Indefinite Articles In German

Articles can be categorized into two general categories:

- Definite Articles – English uses the word “the” to refer to a specific person, idea, or object. There are three main definite articles in German: der, die, and das.

- Indefinite Articles – By using the words “a” and “an,” we can refer to more generic individuals, places, or objects. In German, there is no difference between the words ein and eine.

It is often considered one of the most challenging aspects of learning German to use the correct definite and indefinite articles.

The only thing you really need is patience and practice. It is also important to be willing to learn new things.

The German Definite Articles

In German, definite articles differ based on gender, case, and number. Later on, we will explore how to determine the gender of nouns and assign the proper articles.

Let us now examine the following options:

As you can see above, there are three primary definite articles: der, die, and das. It is also possible to use the word “die” in the plural form. A definite article has three cases in addition to its gender: nominative, accusative, and dative. Learn more about the German Case System if you have not already done so.

Here are some simple examples of definite articles in sentences:

Example In German: Der Mann heibt Heinrich.

Translation In English: The man is named Heinrich.

Example In German: Die Frau liest mir das Buch.

Translation In English: The woman reads the book to me.

Example In German: Das Kind gibt dem Lehrer den Apfel.

Translation In English: The child gives the teacher the apple.

We will now examine what happens to adjectives that are used between definite articles and their nouns.

Definite Article Adjective Endings

Additionally, if you wish to add an adjective between the definite article and a noun, you must add an appropriate German ending.

According to the table above, in the nominative and accusative cases, the adjective ending is always ‘e’ for feminine and neuter nouns.

For adjectives following definite articles, the plural ending is ‘en’. The nominative case of masculine words has an ‘e’ ending. In the accusative and dative cases, the ending is ‘en’.

To demonstrate how adjective endings work, we will add some adjectives to the previous example sentences:

Example In German: Der kleine Mann heibt Heinrich.

Translation In English: The small man is named Heinrich.

Example In German: Die nette Frau liest mir das Buch.

Translation In English: The nice woman reads the book to me.

Example In German: Das kleine Kind gibt dem neuen Lehrer den frischen Apfel.

Translation In English: The young child gives the new teacher the fresh apple.

The first example uses the masculine pronoun der Mann. In addition, the subject uses the nominative form with an e-ending. The next example uses die Frau, which is a feminine noun in the nominative case, hence the ‘e’ ending.

Similarly, das Kind is a neuter noun in the nominative case. It also takes an ‘e’ ending. An indirect object receiving an object is dem Lehrer, which takes the dative case and an en ending. It is the direct object, den Apfel, that takes the accusative case and an en ending.

The German Indefinite Articles

In the same way, indefinite German articles vary according to gender and case.

Let us put those indefinite articles into sentences as follows:

Example In German: Ich sehe einen Mann.

Translation In English: I see a man.

Example In German: Wir treffen eine Frau.

Translation In English: We are meeting a woman.

Example In German: Er hat ein Kind.

Translation In English: He has a child.

In all of the examples above, the accusative case is used. Nouns, however, take the form that corresponds to their gender.

Indefinite Article Adjective Endings

As with definite articles, if you want to use an adjective after an article and before a noun, it will require an ending.

In the nominative and accusative cases, the feminine and neuter forms remain unchanged, but only in the dative case do they change. However, masculine articles are the most likely to change.

Example In German: Ich sehe einen alten Mann.

Translation In English: I see an old man.

Example In German: Wir treffen eine reiche Frau in einem hohen Schloss.

Translation In English: We are meeting a rich woman in a tall castle.

Example In German: Er hat ein zweites Kind mit einer anderen Frau.

Translation In English: He has a second child with another woman.

The first sentence uses the accusative case for einen Mann. The adjective alt (old) has an en ending. In addition, eine Frau, also in the accusative case, requires an ‘e’ ending for its adjective reich (rich). Lastly, both the second and third examples end with dative prepositional phrases.

What Is Most Hardest Languages To Learn For English Speakers?

German Articles Have Genders

There are three genders for German nouns: masculine, feminine, and neuter and the appropriate article is required for each.

However, how can you determine which words belong to which gender? Some noun genders must be memorized, while others can be identified by various combinations of letters.

In the first place, some German nouns have a biological basis for their gender.

Second, most occupational names are available in both masculine and feminine forms, depending on the individual’s gender. Other German nouns, on the other hand, follow grammatical gender patterns.

It is important to note that in English, objects are referred to as “it.” But in German, you use a pronoun that corresponds to the noun’s gender, er, sie, or es.

German Articles: How To Determine Their Gender

While not all German nouns follow a gender rule, certain letter combinations and other guidelines can assist you in selecting the correct gender 9 out of 10 times.

- In German, over 65% of one-syllable words have a masculine gender.

- Second, some suffixes, such as ant, er, and or, are almost always masculine.

- In addition, endings such as heit, keit, and ung are feminine.

- Last but not least, neuter endings include chen, lein, um, and o.

As a result, when you learn new German words, you should also learn their gender. In addition, you will need the gender in order to add the correct endings to several other words within a sentence. The gender of a noun can often be determined by specific clues.

In order to determine whether we need to use der, die, or das, let’s examine these hints in more detail.

Why Is German So Hard To Learn For English And Spanish Speakers?

The Article Der And Masculine Nouns

Firstly, the following suffixes tend to indicate masculine gender (right):

- (mathbf{color{red}{ant:longrightarrow}}) Diamant (diamond), Elefant (elephant), Praktikant (intern)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ent:longrightarrow}}) Student (student), Patient (patient), Assistent (assistant), Dozent (professor)

- (mathbf{color{red}{er:longrightarrow}}) Fahrer (driver), Maler (painter), Spieler (player)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ich:longrightarrow}}) Teppich (carpet), Rettich (radish)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ismus:longrightarrow}}) Kapitalismus (capitalism), Tourismus (tourism), Alkoholismus (alcoholism)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ist:longrightarrow}}) Kapitalist (capitalist), Tourist (tourist), Kommunist (communist)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ling:longrightarrow}}) Zwilling (twin), Frühling (spring)

- (mathbf{color{red}{or:longrightarrow}}) Autor (author), Diktator (dictator),

There are also the following masculine nouns:

- (mathbf{color{red}{Seasons:longrightarrow}}) der Sommer (the summer), der Herbst (the fall), der Winter (the winter)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Months:longrightarrow}}) der Januar (January), der Februar (February), der März (March)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Days:longrightarrow}}) der Montag (Monday), der Dienstag (Tuesday), der Mittwoch (Wednesday)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Map and compass directions:longrightarrow}}) der Norden (north), der Suden (south), der Westen (west), der Osten (east)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Cars and trains:longrightarrow}}) der BMW, der Volkswagen, der Mercedes

- (mathbf{color{red}{Many currencies:longrightarrow}}) der Euro, der Dollar, der Cent

- (mathbf{color{red}{Most mountains or lakes:longrightarrow}}) der Mount Everest, der Mississippi, der Montblanc

By familiarizing yourself with the categories and typical endings of words that tend to have a particular noun gender, you will be able to manage the learning process much more effectively. It is also important to note that German occupations can take either a masculine or feminine form. It is usually followed by er or or in the masculine form.

Is Italian Hard To Learn For English And Spanish Speakers?- The Real Facts

The Article Die And Feminine Nouns

Second, below are the tell-tale suffixes of feminine nouns (die):

- (mathbf{color{red}{e:longrightarrow}}) Blume (flower), Summe (sum), Katze (cat)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ei:longrightarrow}}) Polizei (police), Datei (data), Konditorei (confectionary)

- (mathbf{color{red}{heit:longrightarrow}}) Freiheit (freedom), Gesundheit (health), Sicherheit (security)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ie:longrightarrow}}) Garantie (guarantee), Fantasie (fantasy), Ökonomie (economy)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ik:longrightarrow}}) Grammatik (grammar), Mathematik (math), Musik (music)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ion:longrightarrow}}) Nation (nation), Funktion (function), Produktion (production)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ität:longrightarrow}}) Nationalität (nationality), Autorität (authority), Spontaneität (sponteneity)

- (mathbf{color{red}{keit:longrightarrow}}) Aufmerksamkeit (attention), Schwierigkeit (difficulty)

- (mathbf{color{red}{schaft:longrightarrow}}) Freundschaft (friendship), Landschaft (landscape), Gemeinschaft (community)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ung:longrightarrow}}) Erfahrung (experience), Empfehlung (recommendation), Zeitung (newspaper)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ur:longrightarrow}}) Natur (nature), Kultur (culture), Agentur (agency)

There are also the following feminine nouns:

- (mathbf{color{red}{Names of flowers:longrightarrow}}) die Rose (rose), die Tulpe (tulip)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Names of trees:longrightarrow}}) die Kiefer (pine), die Buche (beech), die Eiche (oak)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Most fruits:longrightarrow}}) die Birne (pear), die Zitrone (lemon), die Melone (melon)

- (mathbf{color{red}{Cardinal numbers:longrightarrow}}) die Eins (one), die Zwei (two), die Drei (three)

The ending-in is also added to feminine occupations.

Among the examples are die Lehrerin (the female teacher), die Professorin (the female professor), die Fotografin (the female photographer), and die Kellnerin (the female waitress).

Is French Easy Or Hard To Learn? The Reality And Analysis for Beginners

The Article Das And Neuter Nouns

Finally, the endings below indicate nouns that are neuter (das).

- (mathbf{color{red}{chen:longrightarrow}}) Mädchen (girl), Häuschen (little house),

- (mathbf{color{red}{lein:longrightarrow}}) Häuslein (little house), Mäuslein (little mouse), Fräulein (young woman)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ma:longrightarrow}}) Thema (topic), Drama (drama), Schema (diagram)

- (mathbf{color{red}{ment:longrightarrow}}) Moment (moment), Dokument (document), Experiment (experiment)

- (mathbf{color{red}{nis:longrightarrow}}) Geheimnis (secret), Gefängnis (jail), Kenntnis (knowledge)

- (mathbf{color{red}{tel:longrightarrow}}) Hotel (hotel), Viertel (quarter)

- (mathbf{color{red}{tum:longrightarrow}}) Eigentum (property), Königtum (kingdom), Christentum (Christianity)

- (mathbf{color{red}{um:longrightarrow}}) Aquarium (aquarium), Museum (museum)

The rules are not absolute, however, and there are exceptions.

like- die Firma (company), der Reichtum (wealth), der Irrtum (mistake), der Zement (cement)

Compound Noun Genders

A number of German words combine multiple nouns into a single word.

- (mathbf{color{red}{die Baustelle:longrightarrow}}) construction site

- (mathbf{color{red}{der Fahrplan:longrightarrow}}) the timetable

- (mathbf{color{red}{das Kinderbuch:longrightarrow}}) children’s book

The gender of a compound noun is usually determined by the last word of the compound noun. However, there are some exceptions to this rule, as is usual.

- (mathbf{color{red}{der Teil (part):longrightarrow}}) Some compound nouns taking Part include das Gegenteil (opposite), das Einzelteil (individual part), das Abteil (compartment), das Oberteil (top piece), das Ersatzteil (replacement part), das Urteil (verdict).

- (mathbf{color{red}{der Mut (courage):longrightarrow}}) Several compound nouns containing the word Mut contain feminine articles, for example, die Armut (poverty), die Wehmut (sorrow), die Demut (humility), die Anmut (grace), die Grossmut (generosity), and die Langmut (patience).

In addition, there are many other exceptions to the noun gender rules. However, following the guidelines when in doubt will work approximately 80% of the time.

40+ Mexican Slang Words Or Phrases And Expressions For Travel, Life, And Homie

Plural German Articles

I would like to take a moment to explain how plural articles work in German. The article die is always used in the nominative and accusative cases of plural nouns.

- (mathbf{color{red}{das Mädchen -the girl:longrightarrow}}) die Mädchen (the girls)

- (mathbf{color{red}{der Junge -the boy:longrightarrow}}) die Jungs/Jungen (the boys)

- (mathbf{color{red}{der Mann -the man:longrightarrow}}) die Männer (the men)

But in the dative plural case, die changes to den.

Example In German: Ich gab den Mädchen Hausaufgaben.

Translation In English: I gave the girls homework.

Example In German: Wir waren überrascht, von den Jungs zu hören.

Translation In English: We were surprised to hear from the boys.

A definite article’s plural ending is ‘en’ in the nominative, accusative, and dative cases when declining adjectives.

Example In German: die amerikanischen Mädchen.

Translation In English: the American girls.

Example In German: Ich gab den faulen Mädchen Hausaufgaben.

Translation In English: I gave the lazy girls homework.

It is also important to know whether a noun is plural or singular when learning the genders of German words.

The noun Mädchen (girl) is the same in the singular and plural forms. In this case, the only way to determine the meaning of the sentence is to examine the articles.

Articles In German Are Affected By The Case

If you wish to choose the appropriate article declension, you will need to know the number, case, and gender of the article. As a result, you have already learned how number and gender affect articles. However, what about the cases?

Let’s examine German articles from a slightly different perspective to see how they vary according to the context.

Counting Turkish Numbers – 1 To 1,000,000,000 With Examples

The Nominative Case

The nominative case is used for the subject of a sentence. There is no difference between the feminine and plural articles.

An example would be:

Example In German: Der/Ein Student lernt schnell.

Translation In English: The/A student learns fast.

Example In German: Die/Eine Blume ist rot.

Translation In English: The/A flower is red.

Example In German: Das/Ein Thema ist langweilig.

Translation In English: The/A topic is boring.)

In all of the above sentence subjects, definite and indefinite articles are used in the nominative case.

The Accusative Case

In addition, direct objects of sentences should be referred to as accusative case articles. The direct object of a sentence is the word that receives the action of the verb.

Accusative Case Articles

The nominative, accusative, and plural forms of neuter and feminine nouns include the same articles. Only the masculine form has changed so far: der becomes den and ein becomes eins.

Example In German: Ich (nominative) kaufe den/einen Tisch (accusative).

Translation In English: I buy the/a table.

Example In German: Ein Fahrer (nominative) liefert die/eine Zeitung (accusative).

Translation In English: A driver delivers the/a newspaper.

Example In German: Meine Mutter (nominative) liest das/ein Buch (accusative).

Translation In English: My mother reads the/a book.)

Poder Conjugation: Present, Past, Future, Imperfect & Conditional Tenses in Spanish

The Dative Case In German

Thirdly, the dative case undergoes the most drastic changes. For indirect objects of a sentence, use the dative. The indirect object is usually the person or thing that is affected by the direct object.

The masculine and neuter articles are the same in the dative case, making them easier to remember. As a result, the feminine articles change into what appears to be the masculine nominative.

Example In German: Der Mann (nominative masculine) gibt den Anzug (accusative masculine) der Reinigung (dative feminine).

Translation In English: The man gives the suit to the dry cleaner.

Example In German: Die Professorin (nominative feminine) gibt dem Student (dative masculine) das Buch (accusative neuter).

Translation In English: The professor gives the student the book.

It is now time for the exciting part. As long as you use the correct articles to indicate the direct and indirect objects, you are permitted to mix up the word order in German.

Example In German: Der Mann (nominative masculine) gibt der Reinigung (dative feminine) den Anzug (accusative masculine).

Translation In English: The man gives the suit to the dry cleaner.

Example In German: Die Professorin (nominative feminine) gibt das Buch (accusative neuter) dem Student (dative masculine).

Translation In English: The professor gives the student the book.

You can place the direct and indirect objects in either position in the sentence, despite the fact that the subject is typically placed in the first position.

How To Use Conjugation Of Preferir Verb (Present, Past & Future Tense) In Spanish?

Possessive Articles

In English, we indicate possession by adding an ‘s to a name or a person’s name. In order to indicate that something belongs to someone in German, you will need possessive articles. For masculine and neuter forms, you will also need an ‘s’ or an ‘es’ ending.

Just as in the dative case, the masculine and neuter forms are identical.

Examples include:

Example In German: das Fahrrad des Mannes.

Translation In English: The man’s bicycle

Example In German: die Jacke der Frau.

Translation In English: The woman’s jacket

Example In German: das Geheimnis des Hotels.

Translation In English: The hotel’s secret.

One-syllable words ending in ‘es’ and multiple-syllable words ending in ‘s’ are usually masculine and neuter.

Here are a few tips to help you learn German articles more efficiently:

- The first step is to learn nouns and their genders together.

- The neuter, feminine, and plural articles remain the same in both the nominative and accusative cases.

- Furthermore, both masculine and neuter articles, as well as definite and indefinite articles, are used in the dative and possessive cases.

- Last but not least, the feminine indefinite articles are the same in the dative and possessive cases.

- Even though learning German articles requires some memorization of charts, the similarities are easily discernible.

By creating connections between the articles and their uses, you will be able to select the correct articles with ease.

Articles of Confederation: Timeline, Strengths, Weaknesses & More

FAQs

What are the 3 main German articles?

In German we have three main articles (gender of nouns): der (masculine), die (feminine), and das (neuter).

How do you identify articles in German?

Nouns are words that name thing, places, ideas, processes, or living creatures, and in German, they’re always written with a capital letter. As in English, German nouns are often preceded by the definite (the) or indefinite article (a/an) or another determiner (e.g. some/any), as well as an adjective or two.

Is there a rule for articles in German?

In the German language, there are three definite articles for nouns in singular: der for masculine nouns, die for feminine nouns, and das for neutral nouns. German native speakers know mostly intuitively what the article of each noun is. However, non-native speakers need to memorize the articles.

How can I practice German articles?

The best way to practice is to listen to them used correctly and then try to use them yourself. Listening to native audio is a great way to practice. If you’re a beginner try listening to a German radio station, video, or podcast and pick out all the nouns you know, making note of which article they’re used with.

Conclusion

Now that you have mastered German articles, it is time to put them to use! When it comes to article declension, practice makes perfect.

For a better understanding of German articles, consider watching German movies or TV series with subtitles.

Furthermore, reading in German is a fantastic way to become more comfortable with the articles and the language in general.

With this knowledge, you will be able to speak German with greater confidence and accuracy.

The Definite Article

Forms – Formen

Each of these definite articles translate into English as “the”.

| Cases | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | der | das | die | die |

| Accusative | den | das | die | die |

| Dative | dem | dem | der | den + n |

| Genitive | des + s | des + s | der | der |

Usage – Gebrauch

The German definite article, in short, replaces the word “the” in English, with just a few exceptions. Formally, it is used for

- something which already has been mentioned or is already known. Readers or listeners know what someone is writing or speaking about. For example, “Ich habe eine Tasse. Aus der Tasse kann ich trinken.”

- something that there is only one of (nouns of rivers, mountains, stars, planets): die Alpen, die Donau

- the superlative: das ist der höchste Berg der Region)

- generalizations (X is a kind of….): Die Rose ist eine Blume.

- certain countries and regions: die Schweiz, die Türkei, die USA (plural), das Elsass, die Steiermark

- abstract concepts, such as das Glück and das Leben — this use differs from English.

Der-Words

Related to the definite article are “der-words”, which decline like the definite article. Here is a list of der-words:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| jen- | that, those |

| solch- | such (a) |

| manch- | many, some |

| jed- | each, every |

| all- | all |

| dies- | this, these |

| welch- | which |

Usage is very similar to usage in English. One thing to keep in mind is that, unlike in English, jener (that) is mostly used to contrast with another noun, dieser, and rarely by itself.

Der-words are declined like the definite article. Here is their declension:

| Cases | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -er | -es | -e | -e |

| Accusative | -en | -es | -e | -e |

| Dative | -em | -em | -er | -en + n |

| Genitive | -es + s | -es + s | -er | -er |

Indefinite Articles

Indefinite Articles translate into English as “a” or “an” and therefore there is no plural. Like in English you use the plural noun without any article.

Forms – Formen

As there is no indefinite article in the plural, kein is used to illustrate plural declension. Make special note region in bold, Oklahoma, where the indefinite article lacks a primary case ending. This is important when declining adjectives.

| Cases | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ein | ein | eine | keine |

| Accusative | einen | ein | eine | keine |

| Dative | einem | einem | einer | keinen +n |

| Genitive | eines +s | eines +s | einer | keiner |

Er schnitt eine Zwiebel. – He chopped an onion.

Er schnitt Zwiebeln. – He chopped onions.

Er schnitt keine Zwiebeln – He chopped no onions

Usage

The indefinite Article is used to introduce new persons or objects or to talk about things which are not precisely identified.

Ein-words

All possessive pronouns, as well as the word, kein, are declined like the indefinite article. These are known as ein-words.

| German | English |

|---|---|

| kein- | no, none |

| Singular | |

| mein- | my |

| dein- | your (sing, informal) |

| sein- | his |

| sein- | its |

| ihr- | her |

| Plural | |

| unser- | our |

| euer- | your (plural, informal) |

| ihr-, Ihr- | their, your (singular and plural, formal) |

Here is their declension:

| Cases | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | – | – | -e | -e |

| Accusative | -en | – | -e | -e |

| Dative | -em | -em | -er | -en +n |

| Genitive | -es +s | -es +s | -er | -er |

The charts and images used on this website are copyright protected.

Sharing or using these images in public or commercially is prohibited.

Contact me for commercial use (e.g. teaching).

(If you would like to share, share this webpage).

German Noun Gender: Your Essential Guide

If you’re like many of my students, you’ve been using Duolingo, watching YouTube, or learning German through various online tools. You picked up on those little words der, die, das that always come in front of nouns — der Mann, die Frau, das Kind, etc.

But why the difference? Why not just pick one — like our English ‘the’ — and use that?

The answer: all German nouns have gender. Everything from bee to bird to table and chair is either a masculine, feminine, or neuter noun.

Going from English as a genderless language to German as a language with three genders is no easy task! It’s a stretch for our brains to think in this new, ‘gendered noun’ way.

Now the big question. How do you know what gender the noun is? Isn’t that going to be complicated?

Well, what if I tell you that there are actually tips and tricks to help you accurately predict the gender of any noun a good 80% of the time?

You’ve come to the right place. Below is my guide to navigate German noun gender.

I’ll show you:

- What you actually need to know to learn noun genders

- How this works for both English and German

- Tips, tricks and resources

- Digging deeper with more intermediate exceptions, rules, and more.

What You Need To Know

Even though it might feel a little painful or pointless at first, trust me — you need to learn German genders properly and well if you truly want to speak German.

Every noun is either masculine, feminine, or neuter. I’m going to walk you through how you can more easily figure out a noun’s gender based on … ready for this? … how the word is spelled.

That’s right! The gender of almost any German noun is determined by its form — especially suffixes, which are little endings such as -at, -ion, -ung, -ig, -um, and more.

Learn the gender of various forms as opposed to getting hung up on individual nouns and you’ll master German gender in a fraction of the time.

HEADS UP: Forming German plurals is also a bit trickier and also is very connected to the form of the singular noun (click for more).

What is Noun Gender?

English uses gendered pronouns — he, she, it, her, him, his, hers, etc. But that’s about it. Not an important aspect of English.

Noun gender, though, is a core part of the German language.

When we talk about noun gender, what do we really mean?

Imagine a multi-tiered cake. The cake is the main part, right? The frosting holds it all together.

With language, the main part is whatever idea you are communicating. Imagine that’s a cake.

Something like noun gender is the ‘grammar frosting’ — it helps hold the ideas together.

German lays the grammar on thick (we scraped our English-language cake pretty bare many centuries ago), but it’s still just glue holding the main ideas together.

For example, I don’t think any German would actually suggest that the qualities of a fork (die Gabel) are feminine, but that of a spoon (der Löffel) are masculine, and that of a knife (das Messer) are neuter.

A language (e.g. English!) can function just fine without so much ‘grammar frosting’, but some might argue that noun gender — in all its intricacies — adds a depth of grammatical character.

In any case, that’s what we’ll tell ourselves to make us feel better as we delve into German noun gender. :p

Heads Up: The intricacies of German don’t end there! German also uses a case system that is crucially important (and very different from how English works).

How Noun Gender Works

He is a tall man. She really loves him.

In English, we substitute gendered pronouns when talking about people (male & female) and then ‘it’ when talking about everything else, as in: How was her vacation? It was really nice.

Other than that, English doesn’t have noun gender.

However, German not only uses gendered pronouns for people (like English does), but also for objects — because, remember, ALL nouns (including all objects!) are gendered nouns in German:

Tisch (table): Er ist nagel-neu. Magst du ihn?

(‘He’ [It] is brand-new. Do you like ‘him’ [it]?)

Blume (flower): Sie ist eine Tulpe. Ich finde sie schön.

(‘She’ [It] is a tulip. I think ‘she’s’ [it’s] pretty).

Haar (hair): Ihr Haar ist braun. Ich finde es lang und üppig!

(Her hair is brown. I think it’s long and lush!)

BUT the concept of noun gender in German has wider application!

For example, check out this sentence –everything bolded is related to the gender of the nouns.

Die hübsche Frau gibt dem armen Mann das rote Päckchen mit lauter Geldstücken.

(The pretty woman gives the poor man the little red package full of coins.)

Heads Up: Everything bolded is called a declension. Learn more about this central (and tricky) concept.

So, all German nouns have 1 of 3 genders and the gender of each noun impacts multiple words in a given sentence. As you can see, German noun gender is important!

When learning a noun in German, it’s crucial to attach the noun to its gender. Don’t learn just Tisch, Blume, Haar. Memorize these new words as der Tisch, die Blume, das Haar. For more detailed Study Tips, read below!

Fortunately, whenever we’re dealing with a plural noun, we no longer have to worry about gender. Regardless how you say ‘the’ for the singular noun, ‘the’ just becomes die for all the plural versions (die Hunde, die Katzen, die Pferde).

However, there are 5 different ways to form plurals in German (not counting oddballs) so you’ll want to become well-versed in that, too. Read more on noun plurals here.

Learn German Noun Gender Smarter, Not Harder

As you’re just getting started with German, it’s a good idea to memorize the gender for each isolated noun.

BUT. The average native speaker (of any language) uses upwards of 20,000 — many of which are nouns. Memorizing the gender each and every noun would be mighty-hard to do.

Luckily, we have a few tricks up our sleeves!

Nouns can be lumped together according to:

- Noun Groups (specific topic groups associated with particular genders)

e.g. all months of the year are masculine - Noun Forms (specific spelling patterns associated with particular genders)

e.g. all nouns ending in -ung are feminine

Read below in the ‘Digging Deeper’ section for many examples (and exceptions) to these noun group & noun form rules!

Digging Deeper

In this section, we’ll explore various noun groups & noun forms associated with one gender over the others. We’ll also talk about ‘outliers’ nouns such as these:

- nouns that defy the typical rules for groups, forms, and compounds

- foreign-word nouns for which gender hasn’t (yet) been firmly established

- nouns with varying gender based on the context and/or region

- nouns with double (or triple!) genders, with then different definitions

- English loan-words

Noun Groups

You’re busy and sometimes German feels like a big bite that you’ve somehow got to chew.

So, how can you learn German genders smarter, not harder?

One answer: by learning the gender of various topics!

There are many topics — weather, numbers, minerals — that are closely associated with just one of the three genders, with limited exceptions.

Below, we’ll look at which topics you can quickly learn to associate with which gender (including examples & common exceptions).

Masculine Groups

The following topics are filled with largely masculine nouns.

It’s much faster to memorize which categories (e.g. days of the week) are masculine — even noting the handful of exceptions — then to keep memorizing the gender of each individual noun you come across.

Learning the following subjects with masculine nouns builds a big-picture framework that you can attach individual words to (and remember them better!).

In other words, learning these categories of masculine nouns provides you with helpful context.

Listed are the masculine noun subject areas and exceptions (click for examples):

der Bock (billy goat), der Hahn (rooster), der Stier (bull), der Eber (boar)

der BMW, der Skoda, der Ford, der Ferrari, der Audi, der VW, der Mercedes

der Dollar, der Euro, der Cent, der Schilling, der Pfennig, der Franken

Common exceptions:

die Mark (former German currency), das Pfund (British pound), die Krone (Danish currency)

der Sonntag (Sunday), der Januar (January), der Winter, der Monat (month), der Abend (evening)

Common exceptions:

das Jahr (year), die Nacht (night), die Woche (week)

der Norden (north), der Osten (east), der Suden (south), der Westen (west)

der Gin, der Schnaps, der Wein (wine), der Kakao (cocoa), der Saft (juice)

Common exception:

das Bier (beer)

der Mann (man), der Vater (father), der Arzt (doctor), der Italiener (italian man)

Examples:

der Mount Everest, der Montblanc, der Himalaja, der Taunus, der Balkan

Common exceptions:

die Eifel, die Haardt, die Rhön, die Sierra Nevada, and mountains / mountain ranges that are actually compound nouns (compound nouns take the gender of the final noun): das Erzgebirge, das Matterhorn, die Zugspitze

der Ganges, der Mississippi, der Nil, der Delaware, der Jordan, der Kongo

Common exceptions:

non-German rivers ending in -a or -e, e.g.: die Seine, die Themse (Thames), die Wolga

der Mond (moon), der Stern (star), der Merkur (Mercury), der Mars, der Jupiter, der Saturn, der Uranus, der Pluto

Common Exceptions:

die Sonne (sun), die Venus, die Erde (Earth)

der Diamant, der Granit, der Lehm (clay), der Quarz, der Ton (cement)

Common exceptions:

das Erz (ore), die Kohle (coal), die Kreide (chalk), das Mineral (mineral)

der Taifun (typhoon), der Wind, der Frost, der Nebel (fog)

Common exceptions:

die Sonne (sun), die Wolke (cloud), die Brise (breeze), das Eis (ice), das Gewitter (thunderstorm), die Graupel (hail), das Wetter (weather), die Witterung (atmospheric conditions)

Feminine Groups

There are many masculine and neuter noun topics. There are notably fewer feminine noun categories (even easier to memorize!).

Extra Bonus: various means of transportation (ships, motorbikes, etc.) can also be referred to as feminine in English (“Check out my new boat! She’s a real beauty!”), which is one of the rare instances in English that we might use gendered pronouns for anything other than people. So, make the most of that connection!

Listed are the feminine noun subject areas and exceptions (click for examples):

die Boeing, die Cessna, die BMW, die Honda, die “Bismarck”, die “Bremen”

Common exceptions:

Means of transportation that maintain the gender of the base word, e.g.: der Airbus, der Storch, der “Albatros”, das “Möwchen”

Also general means of transportation: der Zug (train) [but die Bahn (railway/train)!], der Wagen / das Auto (car), das Schiff/Boot (ship/boot), das Fahrrad (bike), das Motorrad (motorcycle)

die Gans (goose), die Kuh (cow), die Sau (sow), die Henne (hen)

die Frau (woman), die Mutter (mother), die Ärztin (doctor), die Italienerin

Notable exceptions:

das Weib (woman, derogatory), das Fräulein (young woman, miss), das Mädchen (girl)

Note on female persons:

Professions (e.g. der Arzt, doctor) and other persons (e.g. der Bettler, beggar; der Fahrer, driver) are most often transformed into the female version by adding and -in: die Ärztin, die Bettlerin, die Fahrerin). Read more below in the section on feminine noun forms.

die Eins (1), die Zwei (2), die Sechzehn (16), die Million, die Milliarde (billion)

Common exceptions:

Quantity expressions such as das Dutzend, das Hundert, das Tausend

die Donau, die Elbe, die Havel, die Mosel, die Oder, die Weser

Some exceptions:

der Inn, der Lech, der Main, der Neckar, der Rhein

die Eiche (oak), die Pflaume (plum), die Tulpe (tulip),

Exceptions: der Ahorn (maple), der Apfel (apple), der Löwenzahn (dandelion)

Neuter Groups

Like the masculine noun topics, there are many neuter noun categories.

Still, if you’re feeling overwhelmed, remember to 1) just take it all slowly and gradually and 2) cheer yourself with the truth that this way is still infinitely better when you were memorizing what seemed like purely random gender for each individual noun! Now you have a system!

Listed are the neuter noun subject areas and exceptions (click for examples):

das “A”, das “B”, das “Fis” (F-sharp), das “Des” (D-flat)

das Afrika, das London, das Frankreich (France), das Bayern (Bavaria)

Common exceptions:

die Arktis (Artic), die Antarktis (Antarctica), die Schweiz (Switzerland) and other provinces or countries, including those that end in -a, -e, -ei, and -ie (e.g. die Türkei) that are gendered feminine with the exception of Afrika and China, which are still neuter; some countries are masculine: der Iran, der Jemen, der Kongo, der Libanon, der Sudan.

das Singen (singing), das Blau (blue), das Spanisch, das Meeting, das Nein (no)

das Marriott, das “Hard-Rock”, das Hilton, das “Grand Rex”

das Gold, das Kobalt (cobalt), das Blei (lead), das Eisen (iron), das Kupfer (copper)

Common exceptions:

die Bronze (bronze), der Phospor (phosphorus), der Schwefel (sulfur), der Stahl (steel), also metals or chemical elements that are compounds such as der Sauerstoff (oxygen)

das Atom, das Elektron, das Volt, das Watt

Common exceptions:

Liter and Meter having varying gender. (Read more in the Noun Outliers section.)

das Baby, das Kind (child), das Ferkel (piglet), das Fohlen (foal), das Lamm (lamb)

Tip: In many, but not all, instances, the exceptions to the noun group rules can be explained by understanding that the noun form rules (keep reading below!) most often trump the noun group rules.

Noun Forms

In addition to noun groups, we can categorize German noun gender according to spelling patterns (generally ‘suffixes’ added on to the end of words).

It’s very useful to learn both noun groups and noun forms, but note that, when in conflict, the following noun form rules overrule noun group rules!

You may find some other words that seem to break the rules for noun forms, but, really, are shortened words that take the gender of the full form, for example:

der Akku (Akkumulator) battery [-or is a masc. ending]

das Labor (Laboratorium) laboratory [-um is a neut. ending]

die Uni (Universität) university [-tät is a fem. ending]

Masculine Forms

The following are masculine noun suffixes and other forms associated with masculine noun gender (click for examples and exceptions):

Examples: der Konsonant (consonant), der Kontrast (contrast), der Teppich (rug, carpet), der Käfig (cage), der Schwächling (weakling), der Faktor (factor), der Zirkus (circus)

der Betrieb (operation, company, plant), der Biss (bite, from bissen), der Fall (case, instance; drop, from fallen), der Gang (gear; aisle)

Common exceptions:

das Grab (grave), das Leid (harm, sorrow), das Maß (measurement), das Schloss (castle), das Verbot (ban, prohibition)

der Hafen (harbor), der Flügel (wing), der Schatten (shade), der Fehler (mistake) and all nouns referring to people (most are from verbs), e.g. der Bäcker (baker, from backen), der Fahrer (driver, from fahren), but also der Onkel (uncle), der Vater (father), etc.

Some common exceptions

all gerunds such as das Essen (the food, eating) or das Fahren (driving); die Butter (butter), die Regel (rule), die Wurzel (root), die Geisel (hostage), das Fieber (fever), das Segel (sail), das Zeichen (sign, symbol)

NOTE: there are no -en nouns that are feminine!

Feminine Forms:

Here are feminine noun suffixes and other forms associated with feminine noun gender (click for examples and common exceptions):

-a, -anz, -enz, -ei, -ie, -heit, -keit, -ik, -sion, -tion, -sis, -tät, -ung, -ur, schaft

die Pizza, die Dissonanz (dissonance), die Frequenz (frequency), die Konditorei (pastry shop), die Demokratie (democracy), die Dummheit (stupidity), die Möglichkeit (possibility), die Musik (music), die Explosion, die Revolution, die Basis, die Realität (reality), die Prüfung (exam), die Prozedur (procedure), die Freundschaft (friendship)

Common exceptions:

das Sofa, das Genie (genius) ,der Atlantik, der Katholik, das Mosaik, der Pazifik, das Abitur (university-entrance diploma), das Purpur (purple)

die Studentin (female student), die Kauffrau (businesswoman)

die Blume (flower), die Lampe (lamp), die Katze (cat), die Decke (blanket; ceiling) die Collage, die Marionette

Some common exceptions: der Käse (cheese), das Auge (eye), das Ende (end), das Interesse (interest), most nouns that end with -e but begin with Ge- (e.g. das Genie)

die Ankunft (arrival), die Fahrt (drive), die Macht (power), die Aussicht (view)

Some common exceptions

der Dienst (service), der Durst (thirst), das Gift (poison)

Neuter Forms:

Finally, here is the (longest of the 3!) list of suffixes and other forms connected with neuter noun gender (click for examples and common exceptions):

das Mädchen (girl), das Fräulein (young woman, miss), das Dickicht (thicket), das Ventil (valve), das Dynamit (dynamite), das Schema (schematic), das Experiment, das Viertel (quarter), das Christentum (christianity), das Museum, das Individuum (individual)

Common exceptions:

der Profit, der Granit, die Firma (company), der Zement (cement), der Reichtum (wealth), der Irrtum (error)

das Gesetz (law), das Gespräch (conversation), das Gebäude (building)

Common exceptions:

der Gedanke (thought), der Geschmack (taste), and approx. 20 other masculine and feminine nouns that start with Ge- not counting any Ge- nouns referring to male or female persons (e.g. der Genosse / die Genossin — comrade)

das Bedürfnis (need), das Ereignis (event), das Schicksal (fate)

Note

The remaining 30% of -nis and -sal nouns are feminine and many originate from adjectives or indicate states of mind: die Bitternis (bitterness), die Finsternis (darkness), die Besorgnis (anxiety), die Betrübnis (sadness). Other: die Erkenntnis (perception), die Erlaubnis (permission), die Kenntnis (knowledge, cognition, skills), die Mühsal (hardship)

-al, -an, -ar, -är, -at, -ent, -ett, -ier, -iv-, -o, -on (foreign loan words for objects)

IF the suffixes -al, -an, -ar, -är, -at, -ent, -ett, -ier, -iv-, -o, -on are used to refer to male persons, they take the masculine: der Student, der Militär (military man), der Kanadier (male Canadian).

Otherwise, these suffixes are generally neuter: das Lineal (ruler), das Organ, das Formular, das Militär (military), das Sekretariat (secretary), das Talent, das Etikett (label, tag), das Papier (paper), das Adjecktiv (adjective), das Büro (office), das Mikrophon

TIP: if you memorize just the masculine and feminine forms, you can know by default that whatever else you come across is either definitely a neuter noun or some sort of wacky outlier.

Noun Compounds

Usually, the final word in a compound noun determines the gender, as in:

der Fahrplan (timetable)

die Bushaltestelle (bus stop)

Note that the gender of acronyms is similarly determined by the base word:

die CDU (die Christlich-Demokratische Union)

However, there are notable exceptions!

- Many compounds of der Mut (courage) are feminine: die Anmut (gracefulness), die Armut (poverty), die Demut (humility), die Großmut (generosity), die Langmut (patience), die Sanftmut (gentleness), die Schwermut/Wehmut (melancholy)

- Some compounds of der Teil are neuter (most usually in reference to mechanical parts): das Abteil (compartment), das Gegenteil (opposite), das Ersatzteil (replacement part), das Einzelteil (separate part), das Oberteil (upper part), das Urteil (verdict); however, der Vorteil (advantage) and Nachteil (disadvantage).

- And there are still others, such as the common das Wort (word), but die Antwort (answer) and die Woche (week), but der Mittwoch (Wednesday)

Other Noun Outliers

We have already seen many oddball nouns that don’t abide by the typical noun group or even noun form rules.

But there are even more outliers!

- Foreign words sometimes still have their noun gender up for grabs.

- The gender changes for some other nouns (often, but not always, also foreign in origin) based on region (e.g. Germany vs. Southern Germany, Austria or Switzerland) or if the word is being used colloquially or in technical jargon.

- There are also some nouns that have two different genders AND different meanings of the noun associated with that change — for example, der Golf and das Golf. Can you guess the definitions? Keep reading to see if you’re right!

In fact, there is even one word that can take each of the three genders: BAND

- der Band (book volume)

- die Band (music band)

- das Band (ribbon; fetter)

- Finally, there are so many English loan words that we need to deal with those gender patterns separately. Heads up: loan words generally try to comply with standard German noun form (not group) rules.

Keep reading! You’re well on your way to a very thorough understanding of German noun gender including all these special cases!

Nouns with ambiguous gender

der/das Break

der/das Deal

der/das Ketchup

der/die/das Joghurt

der/die Parka

der/das Radar

der/das Soda

Nouns with varying gender

| Filter | der (techn. das) |

| Foto | das (Sw. die) |

| Keks | der (Au. das) |

| Kompromiss | der (Au. das) |

| Liter & Meter | das (coll., and Sw. der) |

| Match | das (Au./Sw. der) |

| Meteor | der (astronom. das) |

| Mündel | das (legal: der) |

| Radio | das (S.G. der) |

| Taxi | das (Sw. der) |

| Teil | der (das in set phrases) |

| Virus | der (medic. das) |

Nouns with double genders

| der Bund (union; waistband) | das Bund (bundle, bunch) |

| der Gefallen (favor) | das Gefallen (pleasure) |

| der Golf (gulf) | das Golf (golf) |

| der Kiefer (jaw) | die Kiefer (pine) |

| der Laster (lorry, semi-truck) | das Laster (vice) |

| der Leiter (leader) | die Leiter (ladder) |

| der Pack (package) | das Pack (mob, rabble) |

| der Schild (shield) | das Schild (sign, plate) |

| der See (lake) | die See (sea) |

| die Steuer (tax) | das Steuer (steering-wheel) |

| der Tau (dew) | das Tau (rope) |

| der Verdienst (earnings) | das Verdienst (merit, achievement) |

English Loan Words

When applicable, English loan words will take whatever gender is associated with the same suffix (or whatever suffix is pronounced the same way, even if spelled differently):

der Computer (-er is generally a masculine ending)

der Rotor (-or is a masculine ending)

die City, die Party, die Lobby, die Story (-ie is a feminine ending; pronounced the same!)

das Ticket, das Pamphlet (-ett is a neuter ending)

das Advertisement, das Treatment (-ment is a neuter ending)

Otherwise, an English loan word might take the gender of the nearest German equivalent word:

der Airbag (der Sack)

die Box (die Büchse)

der Lift (der Aufzug)

das Baby (das Kind)

der Shop (der Laden)

das Handy (das Telefon)

If there are no other indications, monosyllabic loan words (and non-loan words, too, actually) are generally masculine:

der Hit, der Look, der Rock, der Talk, der Lunch, der Spot, der Trend

However, of course, here are some common exceptions: die Bar, die Couch, das Steak, das Team

Note: Loan words that are phrasal verbs or -ing forms are usually neuter: das Handout, das Teach-in, das Check-up, das Meeting, das Blow-up

Main Takeaways

- There are 3 noun genders in German: masculine, feminine, and neuter. English does not have a comparable system, so noun gender is difficult for a lot of native English speakers learning German.

- German noun gender is determined generally based on the gender of the person (e.g. der Mann) OR because its form (usually a suffix, e.g. -ung is feminine) OR because it belongs to a noun group associated with a particular gender (e.g. metals are usually neuter).

- There are a lot of exceptions to all the rules (they are often logical if you come at them from a different angle, though); however, the noun group and forms rules will guide you true a good 80% of the time, which is still loads better than when you thought German noun gender was completely without rhyme or reason!

- If you really want to crack the German noun gender code, continue memorizing the gender associated with each individual noun, BUT make the connection to noun group / form whenever possible (80% of the time, right?) so that you’re simultaneously practicing the rules. As many as there are, it’s still easier to memorize a few dozen rules and their top exceptions then to memorize thousands of isolated words without the connection to the rules (which is what you were doing before reading this guide to German noun gender!).

German Noun Gender Study Tips

Create your own dictionary.

When you learn a new noun that you find relevant to your life, write it into a mini notebook that’s been split into sections for nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, and phrases.

Use flashcards.

Write the German word (without gender) on one side, the gender abbreviation (M = masculine, F = feminine, and N = neuter) and translation (as necessary; avoid whenever possible) on the other.

Color-code for gender.

Pick three contrasting colors for the masculine, feminine, and neuter. I use red, blue, and green, respectively. In your dictionary, write new nouns in the color of the gender of that noun. For example, write ‘Hund’ (dog) in red, ‘Katze’ (cat) in blue, ‘Pferd’ (horse) in green.

As an alternate idea for your flashcards, write the word color-coded like the examples above and just the translation (or better yet, draw a picture!) on the reverse side.

Memorize a smattering of words in each noun group.

Example: envision RED (<– for masculine nouns) mountains while you recite some mountain names, der Himalaja, der Taunus, der Mount Everest

Example: envision BLUE (<– for feminine nouns) numbers while you recite die Eins, die Zwei, die Drei, etc.

Example: envision GREEN (<– for neuter nouns) alphabet letters while you recite das A, das B, das C, etc.

You don’t even have to memorize actual vocabulary to make this a useful visualization exercise. You can just imagine the different noun groups (rivers, hotels, transportation, etc.) and see those items as the corresponding gender color. So, for example, imagine walking down a street seeing hotels, cafes, restaurants and movie theaters that are all green because that noun group is neuter.

Memorize single-word examples for noun forms.

For each suffix or other noun form, memorize one word (useful to you or for some other reason easier to recall) that represents that noun form. Then, when you come across another word with the same form, it will be easier for you to know which gender to pair with it.

For example, if you memorize das Resultat (result), it’s easier to know that the gender of Konsulat (consulate) is also neuter.

Think in pictures!

Several examples are already listed above for using pictures as much as possible. Not only do colors ‘stick’ in the memory better, but if you can train yourself to think in pictures (e.g. pairing the new German noun to an image of that person / object in your mind) vs. translating into English, you will be well on your way to true fluency.

Example: when you learn der Tisch, see a RED table in your mind. Even when you learn an abstract noun such as die Freiheit (freedom), you can still think in images — imagine you’ve been freed from prison. You’re just outside the gates (wearing all BLUE, of course), you raise your arms in joyous victory and shout Freiheit!

Thinking in images — whether a still shot or a short movie clip — allows you to attach the German word directly to the concept, bypassing English altogether. By training yourself this way, you will nurture a ‘German brain’ which you’ll be able to switch over to from your ‘English brain’ with the ease of turning a light on or off. As your language capabilities get more and more advanced, you won’t be slowed down by tediously translating in your head before you can produce the desired German. Trust me on this one!

Wacky mnemonic devices usually work best!

When memorizing noun groups or noun forms according to gender, pick practical (to you!) examples BUT string them all together with wacky, vivid imagery.

For example, you want to memorize all the feminine noun forms. First, you make this list:

Pizza, Eleganz, Krankheit, Seife, Übelkeit, Bücherei, Frequenz, Panik, Hand (a common word that is an exception to the rule — we’d expect ‘Hand’ to be masculine [or maybe neuter] because it’s monosyllabic), Chirurgie, Schlacht, Explosion, Strömung, Elektrizität, Nabelschnur, Skepsis, Halluzination

Then, you create a wild story that you can use to tie the words together (using BLUE as much as possible, too, to represent how these words are all feminine).

Imagine a Pizza with BLUE pepperonis, which you put on your head like a hat. You waltz down the hall with Eleganz, dressed from head-to-toe in outlandish BLUE silks. But you have a shriveling Krankheit (sickness) that makes you shrink and shrivel like a prune (not so much Eleganz anymore!). As you stumble and stagger, suddenly you step on a bar of BLUE Seife (soap) that takes you down the hall on such a wild ride that you start to feel Übelheit (nausea) and start to throw up BLUE books that fly up onto the shelves — you´re in the middle of a Bücherei (bookstore) that you’re creating! The walls with the shelves full of books start pulsing and expanding with ever-increasing Frequenz, pushing in on you so that you start to feel great Panik. You look above to see a BLUE Hand materialize that is going to perform Chirurgie (surgery) on the pulsating walls of your Bücherei. But it becomes an absolute Schlacht (massacre) with BLUE pages flying every which way while the Frequenz of the pulsating bookshelf-walls builds in intensity until BOOM! There is an Explosion! You see a bright BLUE Strömung (stream; current) of Elektrizität shoot up into the sky. You look down to see that the BLUE Strömung of Elektrizität is connected to you like a Nabelschnur (umbilical cord)! You feel a lot of Skepsis over that … You say to yourself, this must be a Halluzination!

Like other old IE languages

both PG and the OG languages had a synthetic grammatical structure,

which means that the relationships between the parts of the sentence

were shown by the forms of the words rather than by their position or

by auxiliary words. In later history all the Germanic languages

developed analytical forms and ways of word connection.

In the early periods of

history the grammatical forms were built in the synthetic way: by

means of inflections, sound interchanges and suppletion.

The

suppletive

/sə’pli:tiv/

way of form-building was inherited from ancient IE, it was restricted

to a few personal pronouns, adjectives and verbs.

Compare the following forms of

pronouns in Germanic and non-Germanic languages:

|

L |

Fr |

R |

Gt |

ОIcel |

OE |

NE |

|

ego mei mihi |

je mon me, |

я |

ik |

ek |

ic |

I |

|

меня |

meina |

min |

min |

my, mine |

||

|

мне |

mis |

mer |

me |

me |

The

principal means of form-building were inflections. The inflections

found in OG written records correspond to the inflections used in

non-Germanic languages, having descended from the same original IE

prototypes. Most of them, however, were simpler and shorter, as they

had been shortened and weakened in PG.

The wide use of sound

interchanges has always been a characteristic feature of the Germanic

group. This form-building (and word-building) device was inherited

from IE and became very productive in Germanic. In various forms of

the word and in words derived from one and the same root, the

root-morpheme appeared as a set of variants. The consonants were

relatively stable, the vowels were variable (Consonant interchanges

were also possible but rare. They appeared in PG due to voicing of

fricatives under Verner’s Law but were soon levelled out).

Table 6 shows the variability

of the root *ber- in different grammatical forms and words.

Table 6

Variants of the Root *bef-

|

Old Germanic languages |

Modern Germanic languages |

|||||

|

Gt |

О Icel |

OE |

Sw |

G |

NE |

|

|

forms of the verb bear |

bairan bar berum baurans |

bera bar barum borinn |

beran b r b ron boren birp |

bära bar buro buren |

gebären gebar — geboren |

bear

bore (pl) born bears |

|

other words from the same |

barn baur |

barn burðr byrð |

bearn ʒbyrd |

barn |

Geburt |

barn ‘child’) birth |

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #