From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Word play or wordplay[1] (also: play-on-words) is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, phonetic mix-ups such as spoonerisms, obscure words and meanings, clever rhetorical excursions, oddly formed sentences, double entendres, and telling character names (such as in the play The Importance of Being Earnest, Ernest being a given name that sounds exactly like the adjective earnest).

Word play is quite common in oral cultures as a method of reinforcing meaning. Examples of text-based (orthographic) word play are found in languages with or without alphabet-based scripts, such as homophonic puns in Mandarin Chinese.

Techniques[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

Some techniques often used in word play include interpreting idioms literally and creating contradictions and redundancies, as in Tom Swifties:

- «Hurry up and get to the back of the ship,» Tom said sternly.

Linguistic fossils and set phrases are often manipulated for word play, as in Wellerisms:

- «We’ll have to rehearse that,» said the undertaker as the coffin fell out of the car.

Another use of fossils is in using antonyms of unpaired words – «I was well-coiffed and sheveled,» (back-formation from «disheveled»).

Examples[edit]

This business’s sign is written in both English and Hebrew. The large character is used to make the ’N’ in Emanuel and the ‘מ’ in עמנואל. This is an example of orthographic word play.

Most writers engage in word play to some extent, but certain writers are particularly committed to, or adept at, word play as a major feature of their work . Shakespeare’s «quibbles» have made him a noted punster. Similarly, P.G. Wodehouse was hailed by The Times as a «comic genius recognized in his lifetime as a classic and an old master of farce» for his own acclaimed wordplay.[citation needed] James Joyce, author of Ulysses, is another noted word-player. For example, in his Finnegans Wake Joyce’s phrase «they were yung and easily freudened» clearly implies the more conventional «they were young and easily frightened»; however, the former also makes an apt pun on the names of two famous psychoanalysts, Jung and Freud.

An epitaph, probably unassigned to any grave, demonstrates use in rhyme.

- Here lie the bones of one ‘Bun’

- He was killed with a gun.

- His name was not ‘Bun’ but ‘Wood’

- But ‘Wood’ would not rhyme with gun

- But ‘Bun’ would.

Crossword puzzles often employ wordplay to challenge solvers. Cryptic crosswords especially are based on elaborate systems of wordplay.

An example of modern word play can be found on line 103 of Childish Gambino’s «III. Life: The Biggest Troll».

H2O plus my D, that’s my hood, I’m living in it

Rapper Milo uses a play on words in his verse on «True Nen»[2]

- Keep any heat by the fine China dinner set

- Your man’s caught the chill and it ain’t even winter yet

A farmer says, «I got soaked for nothing, stood out there in the rain bang in the middle of my land, a complete waste of time. I’ll like to kill the swine who said you can win the Nobel Prize for being out standing in your field!».

Eminem is known for the extensive wordplay in the lyrics of his music.

The Mario Party series is known for its mini-game titles that usually are puns and various plays on words; for example: «Shock, Drop, and Roll», «Gimme a Brake», and «Right Oar Left». These mini-game titles are also different depending on regional differences and take into account that specific region’s culture.

[edit]

Word play can enter common usage as neologisms.

Word play is closely related to word games; that is, games in which the point is manipulating words. See also language game for a linguist’s variation.

Word play can cause problems for translators: e.g. in the book Winnie-the-Pooh a character mistakes the word «issue» for the noise of a sneeze, a resemblance which disappears when the word «issue» is translated into another language.

See also[edit]

- Etymology

- False etymology

- Figure of speech

- List of forms of word play

- List of taxa named by anagrams

- Metaphor

- Phono-semantic matching

- Simile

- Pun

References[edit]

- ^ «wordplay: definition of wordplay in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)». Askoxford.com. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.[dead link]

- ^ Scallops hotel – True Nen, retrieved 3 December 2021

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Word play.

- A categorized taxonomy of word play composed of record-holding words

Did you hear about the blind carpenter who picked up his hammer and saw?

Вы слышали о слепом плотнике, который поднял свой молоток и прозрел (saw = увидел = пила)?

= Вы слышали о слепом плотнике, который поднял свой молоток и пилу?

Did you hear about the deaf shepherd who gathered his flock and heard (herd)?

Вы слышали о глухом пастухе, который собрал своё стадо и стал слышать?

(herd = стадо, гурт — произносится одинаково с heard = услышал)

= Вы слышали о глухом пастухе, который собрал своё стадо (и гурт)?

Q:

What letter of the alphabet is an insect?

Какая буква алфавита является насекомым?

A:

B. (bee = пчела)

Q:

What letter is a part of the head?

Какая буква является частью головы?

A:

I. (eye = глаз)

Q:

What letter is a drink?

Какая буква является напитком?

A:

T. (tea = чай)

Q:

What letter is a body of water?

Какая буква является водоёмом?

A:

C. (sea = море)

Q:

What letter is a vegetable?

Какая буква является овощем?

A:

P. (pea = горох)

A: Hey, man! Please call me a taxi.

Эй, человек! Пожалуйста, вызовите мне такси

(call = вызывать = называть)

= Эй, человек! Назовите меня «такси»

B: Yes, sir. You are a taxi.

Слушаюсь, сэр. Вы такси

My friend said he knew a man with a wooden leg named Smith.

So I asked him, «What was the name of his other leg?»

Мой друг сказал, что знал человека с деревянной ногой по имени Смит.

Тогда я спросил: «А как звали его другую ногу?»

Why is this funny?

Почему это смешно?

It’s funny because of the confusion between these two phrases;

«a man with a wooden leg» and «a wooden leg named Smith.»

Это смешно, потому что неясно, как понять:

«a man with a wooden leg» = человек с деревянной ногой или

«a wooden leg named Smith.» = деревянная нога по имени Смит

Listen to the joke again.

Прослушайте шутку ещё раз.

Добавить комментарий

Поделиться:

Word play is verbal wit: the manipulation of language (in particular, the sounds and meanings of words) with the intent to amuse. Also known as logology and verbal play.

Most young children take great pleasure in word play, which T. Grainger and K. Goouch characterize as a «subversive activity . . . through which children experience the emotional charge and power of their own words to overturn the status quo and to explore boundaries («Young Children and Playful Language» in Teaching Young Children, 1999)

Examples and Observations of Word Play

- Antanaclasis

«Your argument is sound, nothing but sound.» — playing on the dual meaning of «sound» as a noun signifying something audible and as an adjective meaning «logical» or «well-reasoned.»

(Benjamin Franklin) - Double Entendre

«I used to be Snow White, but I drifted.» — playing on «drift» being a verb of motion as well as a noun denoting a snowbank.

(Mae West) - Malaphor

«Senator McCain suggests that somehow, you know, I’m green behind the ears.» — mixing two metaphors: «wet behind the ears» and «green,» both of which signify inexperience.

(Senator Barack Obama, Oct. 2008) - Malapropism

«Why not? Play captains against each other, create a little dysentery in the ranks.» — using «dysentery» instead of the similar-sounding «dissent» to comic effect.

(Christopher Moltisanti in The Sopranos) - Paronomasia and Puns

«Hanging is too good for a man who makes puns; he should be drawn and quoted.» — riffing on the similarity of «quoted» to «quartered» as in «drawn and quartered.»

(Fred Allen) - «Champagne for my real friends and real pain for my sham friends.»

(credited to Tom Waits) - «Once you are dead you are dead. That last day idea. Knocking them all up out of their graves. Come forth, Lazarus! And he came fifth and lost the job.»

(James Joyce, Ulysses, 1922) - «I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun

My last thread, I shall perish on the shore;

But swear by Thyself, that at my death Thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore;

And having done that, Thou hast done;

I fear no more.»

(John Donne, «A Hymn to God the Father») - Sniglet

pupkus, the moist residue left on a window after a dog presses its nose to it. — a made-up word that sounds like «pup kiss,» since no actual word for this exists. - Syllepsis

«When I address Fred I never have to raise either my voice or my hopes.» — a figure of speech in which a single word is applied to two others in two different senses (here, raising one’s voice and raising one’s hopes).

(E.B. White, «Dog Training») - Tongue Twisters

«Chester chooses chestnuts, cheddar cheese with chewy chives. He chews them and he chooses them. He chooses them and he chews them. . . . those chestnuts, cheddar cheese and chives in cheery, charming chunks.» — repetition of the «ch» sound.

(Singing in the Rain, 1952)

Language Use as a Form of Play

«Jokes and witty remarks (including puns and figurative language) are obvious instances of word-play in which most of us routinely engage. But it is also possible to regard a large part of all language use as a form of play. Much of the time speech and writing are not primarily concerned with the instrumental conveying of information at all, but with the social interplay embodied in the activity itself. In fact, in a narrowly instrumental, purely informational sense most language use is no use at all. Moreover, we are all regularly exposed to a barrage of more or less overtly playful language, often accompanied by no less playful images and music. Hence the perennial attraction (and distraction) of everything from advertising and pop songs to newspapers, panel games, quizzes, comedy shows, crosswords, Scrabble and graffiti.»

(Rob Pope, The English Studies Book: An Introduction to Language, Literature and Culture, 2nd ed. Routledge, 2002)

Word Play in the Classroom

«We believe the evidence base supports using word play in the classroom. Our belief relates to these four research-grounded statements about word play:

— Word play is motivating and an important component of the word-rich classroom.

— Word play calls on students to reflect metacognitively on words, word parts, and context.

— Word play requires students to be active learners and capitalizes on possibilities for the social construction of meaning.

— Word play develops domains of word meaning and relatedness as it engages students in practice and rehearsal of words.»

(Camille L. Z. Blachowicz and Peter Fisher, «Keeping the ‘Fun’ in Fundamental: Encouraging Word Awareness and Incidental Word Learning in the Classroom Through Word Play.» Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice, ed. by James F. Baumann and Edward J. Kameenui. Guilford, 2004)

Shakespeare’s Word Play

«Wordplay was a game the Elizabethans played seriously. Shakespeare’s first audience would have found a noble climax in the conclusion of Mark Antony’s lament over Caesar:

O World! thou wast the Forrest to this Hart

And this indeed, O World, the Hart of thee,

just as they would have relished the earnest pun of Hamlet’s reproach to Gertrude:

Could you on this faire Mountaine leave to feed,

And batten on this Moore?

To Elizabethan ways of thinking, there was plenty of authority for these eloquent devices. It was to be found in Scripture (Tu es Petrus . . .) and in the whole line of rhetoricians, from Aristotle and Quintilian, through the neo-classical textbooks that Shakespeare read perforce at school, to the English writers such as Puttenham whom he read later for his own advantage as a poet.»

(M. M. Mahood, Shakespeare’s Wordplay. Routledge, 1968)

Found Word-Play

«A few years ago I was sitting at a battered desk in my room in the funky old wing of the Pioneer Inn, Lahaina, Maui, when I discovered the following rhapsody scratched with ballpoint pen into the soft wooden bottom of the desk drawer.

Saxaphone

Saxiphone

Saxophone

Saxyphone

Saxephone

Saxafone

Obviously, some unknown traveler—drunk, stoned, or simply Spell-Check deprived—had been penning a postcard or letter when he or she ran headlong into Dr. Sax’s marvelous instrument. I have no idea how the problem was resolved, but the confused attempt struck me as a little poem, an ode to the challenges of our written language.»

(Tom Robbins, «Send Us a Souvenir From the Road.» Wild Ducks Flying Backward, Bantam, 2005)

Alternate Spellings: wordplay, word-play

If you want to improve your writing, maybe it’s time to ditch all the writing books and podcasts and play some word games instead.

Yes, seriously! Word games and writing games are great ways to develop your vocabulary, to help you think more deeply about words, to have fun with story and structure, and to get a lot of fun out of writing.

But games can be a great way to:

- Develop your vocabulary

- Help you think more deeply about words

- Become more fluent in English (if it’s a foreign language for you)

- Invent and develop characters

… and much more.

After the list of 50 writing games, I’ve given you a top ten that I think are particularly great for kids who want to practice their writing skills. Many of the other games are suitable for children, too, so by all means try out other games as a family if you want to.

Of course, there are loads of online games (and quizzes and tools) that you can use to improve your writing skills, and I will be talking about some of the best of those. But there are also lots of tried-and-tested classic games that you can play with pen and paper, or using cards and dice … and we’ll be taking a look at those first.

5 Pen and Paper Word Games

I’ll start with the simplest games: pen and paper ones that you can play pretty much anywhere, so long as you have a pen.

All of these are suitable for children, and some (like crosswords) are enjoyed by many adults too.

#1: Hangman (2+ players)

Hangman is a classic word game for two players. One player thinks of a word and writes down dashes to represent the number of letters. The other guesses letters of the alphabet. Correct letters are inserted into the word; incorrect letters result in another segment of the “hangman” being drawn.

This is a great game for developing spelling and vocabulary. If you’re playing it with small children, you can do it without the perhaps rather unpleasant “hangman” element, and just count how many guesses each player takes!

#2: Crosswords (1 player)

A crossword is a grid of white and black squares, where each white square is one letter of a word. The words intersect. You can find crosswords in many newspapers and magazines (on all sorts of subjects), and you can buy booklets and books full of them. Some crosswords are “cryptic”: great if you like brainteasers. Others have more straightforward clues.

Crosswords are great if you want to learn new words and definitions, or (at the cryptic end of the scale) if you enjoy playing with words and language. Simple ones are suitable for fairly young children, with a little help.

#3: Word searches (1 player)

A word search has a grid (often 10×10 or more) filled with letters, and a number of words written alongside or beneath the grid. The person completing the word search needs to find those words within the grid.

Most word searches are easy enough for children, though younger children will struggle with backward and diagonal words. They’re a good way to get used to letter patterns and to improve spelling – and because word searches rely on matching letters, even children who can’t read well will be able to complete simple ones.

#4: Consequences (2+ players, ideally 4+)

This is a fun game with a group of people, as you get a wild and wacky mix of ideas. Each player writes down one line of a story and folds the paper over before passing it around the table to the next player. The very simple version we play has five lines: (1) A male name, (2) The word “met” then a female name, (3) “He said …” (4) “She said …” (5) “And then …”

Once all five stages are complete, the players open out the papers and read out the results. This can be great for sparking ideas, or as a way to encourage reluctant writers to have a go.

#5: Bulls and Cows (2 players)

This game, which can also be called “Mastermind” or “Jotto” involves one player thinking up a secret word of a set number of letters. The second player guesses a word; the first player tells them how many letters match in the right position (bulls) and how many letters are correct but in the wrong position (cows).

Our five year old loves this game, and it’s been a great way to develop her spelling and handwriting as well as logical thinking about which letters can or can’t be the correct ones after a few guesses.

10 Board and Dice Games

These are all games you can buy from Amazon (or quite probably your local toyshop). They’re fun ways to foster a love of writing within your family, or to share your enjoyment of words with your friends.

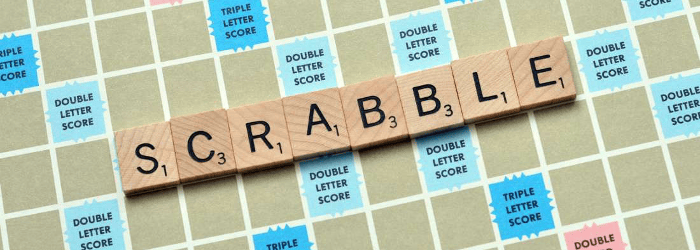

#1: Scrabble (2+ players)

A classic of word games, Scrabble is a game played with letter tiles on a board that’s marked with different squares. (Some squares provide extra points.) Letters have different points values depending on how common they are. The end result of scrabble looks like a crossword: a number of words overlapping with one another.

If you want to develop your vocabulary (particularly of obscure two-letter words…) then Scrabble is a great game to play. It’s suitable for children too, particularly in “Junior” versions.

#2: Boggle (2+ players)

This is less well known than Scrabble, but it was one I enjoyed as a child. To play Boggle, you shake a box full of dice with a letter on each side, and the dice land in the 4×4 grid at the bottom of the box. You then make as many words as you can from the resulting face-up letters.

Again, this is a good one for developing vocabulary – and it can be played by children as well as by adults. You need to write down the words you come up with, which can also be good for developing handwriting.

#3: Pass the Bomb (2+ players)

It’s very simple to play: you deal a card for the round pass a “bomb” around the table and when it goes off, the person holding it loses. Before you can pass the bomb on during your turn, you need to come up with a word that contains the letters on the card.

It’s a fun family or party game, and can work well with a wide range of ages. It’s a great way to help children think about letter patterns, too, and to develop vocabulary and spelling.

#4: Story Cubes (1+ players)

There are lots of different versions of these available, and they all work in a similar way. The open-ended game has a set of cubes that you roll to create ideas for a story that you can tell along with the other players. If you prefer, you can use them to come up with stories that you’re going to write on your own.

There are lots of different ways you can use them: as writing prompts for a school class or group, to make up a bedtime story together with your children, for getting past your own writers’ block, or almost anything you can think of.

#5: Apples to Apples (2+ players)

Apples to Apples has red cards (with the name of a person, place, thing, etc) and green cards (with two different descriptions): the player with a green card selects one of the descriptions, and others have to choose a card from their hand of red cards. The judge for that game decides which red card best matches the description.

If you want to develop your vocabulary (or your kids’), this could be a fun game to play. There are lots of expansions available, plus a “junior” version with simpler words. (If you’re playing with adults, you might also want to consider Cards Against Humanity, a decidedly not-kid-friendly game that works in a very similar way.)

#6: Letter Tycoon (2+ players)

In this game, you have a hand of 7 cards which you can use in conjunction with the 3 “community cards” to create a valuable word. It’s a more strategic game than some others, with aspects of finance (like patents and royalties) involved too – if you’re a budding tycoon, you might really enjoy it.

Because not all the game strategy depends on simply being good with words, it doesn’t matter if some players have a larger vocabulary than others. It’s suitable for children, too, so you can play it as a family game.

#7: Dabble (2+ players)

Dabble is a family-friendly game where you compete with other players to be the first to create five words (of 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 letters) using your 20 tiles. It’s very simple to get the hang of … but coming up with the words might be more challenging than you expect!

If you enjoy Boggle or Scrabble, you’ll probably have fun with Dabble. It’s a great way to develop both spelling and vocabulary, and to have fun with words.

#8: Upwords (2+ players)

Upwords is like 3D Scrabble: you can stack tiles on top of other tiles to create new words. The board is smaller than a Scrabble board (and doesn’t have double and triple word score squares) so it’s not as complex as it might initially sound.

Like similar games, it’s a great one for building vocabulary and for developing your spelling. It’s suitable for kids, too, so it could be a great game for the whole family.

#9: Tapple (2+ players)

Tapple has a wheel, with most of the letters of the alphabet on it, and lots of different “topic cards” that cover 144 different categories. There are lots of different ways you can play it – the basic rules are that each player has to think of a word that fits the topic within 10 seconds, but that word can’t start with a starting letter that’s been used previously.

While small children might find it a bit too challenging or frustrating, due to the short time limit, this could be a great game for older children looking to extend their vocabulary. All the categories are suitable for kids.

#10: Last Word (2+ players)

In Last Word, players have to come up with answers to “Subject” and “Letter” combinations, racing to get the last word before the buzzer. It works a bit like a combination of “Tapple” and “Pass the Bomb”.

You can easily play it with a large group (there are tokens for up to 8 players, but you could add more without affecting the gameplay). It’s a great way to develop vocabulary and, to some extent, spelling.

5 Roleplaying Games

While my geeky tendencies have been reined in a bit since I had kids, I’ll admit I have a great fondness for roleplaying games: ones where you come up with a character (often, but by no means always in a magic-medieval setting) and play as them. These are some great ones that you might like to try.

#1: Dungeons and Dragons (3+ players)

Although you might never have played Dungeons and Dragons, I’m sure you’ve heard of this classic roleplaying game that’s been around since 1974 and is now onto is 5th edition. It takes rather longer to get to grips with than a board or card game: to play, you need a “Dungeon Master” (essentially the storyteller of the game) and at least two players (who each control a character), plus rulebooks and a lot of different dice.

It’s a great game for developing the “big picture” aspects of writing, like the ability to construct a plot and a story (if you’re the Dungeon Master) and the skills involved with creating a character, giving them a backstory, and acting “in character” as them (if you’re one of the players).

#2: Amazing Tales (1 parent, plus 1 or 2 children)

This is a kid-friendly RPG aimed at parents who want to create a story with their child(ren). It’s like a very simple version of Dungeons and Dragons, and has straightforward but flexible rules. You can play it with a single six-sided dice – though it’s better if you have four dice (with six, eight, ten and twelve sides).

If you want to encourage your child’s creativity and have fun creating stories together, this is a wonderful game to play. The rulebook contains lots of ideas and sample settings, with suggested characters and skills … but you can come up with pretty much any scenario you like.

#3: LARP (Live Action Roleplay) (lots of players)

Over the past decade or so, LARP has become a bit more mainstream than it once was. It’s short for “Live Action Roleplay” … which basically means dressing up as your character and pretending to be them. It’s a bit like Dungeons and Dragons crossed with improv drama.

The nature of LARP is that it needs quite a lot of people, so unless you have loads of friends to rope in, you’ll want to join an organised LARP – there are lots out there, covering all sorts of different themes, from traditional fantasy ones to futuristic sci-fi ones. Some are suitable for children, but do ask event organisers about this. They won’t necessarily involve any sort of writing, but can be a great way to explore characters and dialogue.

#4: MUDs (lots of players)

MUDs, or “multi-user dungeons” have been around since the early days of networked computing in the ‘70s, and are the forerunners of games like Fortnite and World of Warcraft. They’re now distinctly retro-looking text-based online games, where players create a character and interact with other characters and the world.

Like other types of roleplaying game, they’re a great way to practice storytelling and character-development skills. They also involve a lot of writing – so they can be useful for things like vocabulary and spelling. Some are suitable for children, but as with anything online, do ensure your children know how to be safe (e.g. by not giving out their full name, address, etc).

#5: Online Forum Games / Forum Roleplaying (2+ players)

Some fan communities write collaborative fanfiction through forums (here’s an example), with different people posting little pieces as different “characters” to continue a story. These can be quite involved and complex, and they can be a great way to learn the skills of telling a long, detailed story (e.g. if you’re thinking of writing a novel).

They’ll probably appeal most to writers who are already producing fanfiction on their own, and who have a fair amount of time for the back-and-forth required for forum roleplaying. Again, if your child wants to get involved with this type of roleplaying, do make sure you monitor what they’re doing and who they’re interacting with.

10 Word Games You Can Play on Your Phone

These days, many writers are more likely to have their phone to hand than a pen and paper … and to be fair, there’s nothing wrong with that. You can easily make notes on a phone, whether by tapping them in or by recording them. If you find yourself with a bit of time on your hands, why not try one of these writing-related games?

Note: all of these are free to download, but most allow in-app purchases, and you may find you need to make a purchase to get the most out of them.

#1: Bonza Word Puzzle

This game is a bit like a deconstructed crossword: you get bits of the puzzle and you drag them together to form words that will all match with the clue. If you’re a fan of crosswords and want something a bit different, you might just love it.

It’s a great way to think hard about letter patterns and how words are put together, so it might be a good game for older children who’re looking to develop their spelling and vocabulary, too.

#2: Dropwords 2

Dropwords 2 (a rewrite of the original Dropwords) is a word-finding puzzle where letters drop from the top of the screen: if you remember Tetris, you’ll get the idea. It’s a bit like Scrabble or Boggle, and you have to race the clock to make letters out of the words on the screen.

With six different modes (“normall”, “lightning”, “relax”, etc), it’s suitable for children and for people who are learning English, as well as for those wanting to really challenge their vocabulary skills.

#3: Spellspire

Spellspire is a fantasy-style game where you select letters from a grid to create words: the longer the word, the bigger the blast from your magic wand! You can kill monsters, buy better equipment, and make your way to the top of the Spellspire.

If your kids aren’t very motivated to practice their spelling, this could be a great game for them. (Or, let’s face it, for you!) You can also choose to play it against your Facebook friends, adding a competitive element.

#4: TypeShift

This is a relatively simple game that lets you create words from letters arranged on different dials. There are a couple of different ways you can play: by trying to use all the letters on the dials at least once to create words, or by tackling the “Clue Puzzles”, which are a bit like crossword clues.

Again, if you want to develop your spelling and vocabulary, this is a straightforward game that you can use to do so. You can buy extra puzzle packs at a fairly reasonable price, if you find that you want to play it a lot.

#5: Wordalot

This crossword app uses pictures rather than written clues, which is a fun twist. You can use coins to get hints (you can earn these through the game, or purchase them with real money).

If you enjoy doing crosswords but want something a bit different, give this one a try. You might find that as well as helping you develop your spelling and vocabulary, it’s a great way to develop your lateral thinking as you puzzle out the clues.

#6: WordBrain

This game is another one where you have to find hidden, scrambled words within a grid. There are loads of different levels (1180!) and so this could keep you busy for a long time. You can purchase hints – this could potentially see you clocking up quite a spend, though.

All the words are appropriate for children (though some are tricky to spell), so your kids might well enjoy this game too, as a way to develop their spelling and vocabulary.

#7: Ruzzle

Ruzzle works like Boggle, with a 4×4 grid of letters that you use to make words (the letters must be adjacent to one another). You can play it against friends, or simply against random players.

Like the other apps we’ve looked at, it’s a good one for developing your vocabulary and spelling. Some players said it included too many ads, so this is something to be aware of if you plan to use the free version rather than upgrading.

#8: WordWhizzle Search

This is a word search type game with loads of different levels to play. If you enjoy word searches, it’s a great way to carry lots around in your pocket! You can play it alone or with Facebook friends. It’s easy to get to grips with, but the levels get increasingly tricky, so you’re unlikely to get bored quickly.

As with other apps, this is a great one for developing your spelling and vocabulary. Each level has a particular description (words should match with this), so you have to avoid any “decoy” words that don’t match.

#9: 7 Little Words

This game works a bit like a crossword: each puzzle has seven clues, seven mystery words, and 20 tiles that include groups of letters. You need to solve the clues and rearrange the letter types so you can create the answers to the mystery words – so it’s also a bit like an anagram.

There are five different difficulty levels (“easy” to “impossible”) and each game is quick to play, so this could be a good one for kids too. Again, it’s a great way to develop vocabulary and spelling.

#10: Words With Friends

This classic word-building game is hugely popular, and you can play against your Facebook or Twitter friends, or against a random opponent. It works just like Scrabble, where you have seven letter tiles and add them to a board.

You can chat with the opponent in a chat window, so do be aware of this if you’re allowing your kids to play. The game is a great way to develop vocabulary and spelling, and you can play it fairly casually because there’s no time limit on your moves.

10 Word Games You Can Play in Your Browser

What if you want a writing-related game you can play while taking a break at your computer? All of these are games that you can play in your browser: some involve a lot of writing and are essentially story-telling apps, whereas others are essentially digital versions of traditional pen and paper games.

Unless otherwise noted, these games are free. With some free browser games, you’ll see a lot of ads. If this annoys you, or if you’re concerned that the ads may be unsuitable for your children, you may want to opt for premium games instead.

#1: Wild West Hangman

This is a digital version of Hangman, which we covered above. You choose a category for words (e.g. “Countries” or “Fruits And Vegetables”) and then you play it just like regular Hangman.

It’s simple enough for children – but it only takes six wrong guesses for your cowboy to be hanged, too, so it could get frustrating for younger children.

#2: Word Wipe

In Word Wipe, you swipe adjacent tiles (including diagonals) to create words, a bit like in Boggle. The tiles fall down a 10×10 grid (moving into the blank spaces you’ve created when your word disappears from the grid) – your aim is to clear whole rows of the grid.

Since the easiest words to create are short, simple ones, this is a great game for children or for adults who want to get better at spelling.

#3: Sheffer Crossword

As you might expect, this is a crossword game! There’s a different free puzzle each day, and you can choose from puzzles from the past couple of weeks. It looks very much like a traditional crossword, and you simply click on a clue then type in your answer.

The clues are straightforward rather than cryptic, though probably not easy enough to make this a good app for children or for English learners. If you’re a fan of crosswords, this will definitely be a great way to develop your vocabulary, though.

#4: Twine

Twine is a bit different from some of the other games we’ve looked at: it’s a tool for telling interactive stories (a bit like the old “Choose Your Own Adventure” books, or a text-based adventure game). You lay out your story as different cards and create connections between them.

If you want to experiment with interactive fiction, this is a simple, code-free to get started – as reviewer Kitty Horrorshow puts it, “if you can type words and occasionally put brackets around some of those words, you can make a Twine game”. It’s a great way to deepen your understanding of story, plot and narrative.

#5: Storium

Like Twine, Storium is designed to help you tell stories … but these stories are written in collaboration with others. (There’s a great review, with screenshots, here on GeekMom.) You can either join a story as a character within it, or you can narrate a story – so this is a great game for building lots of different big-picture fiction-writing skills.

It’s suitable for teens, but probably involves a bit too much writing for younger children. If you’d like to write fiction but the idea of creating a whole novel on your own seems a bit overwhelming, or if you enjoy roleplaying-type games (like Dungeons and Dragons), then you might just love Storium.

#6: Words for Evil

This game combines a fantasy RPG setting (where you fight monsters, get loot, gain levels and so on), with word games to play along the way. It could be a good way to encourage a reluctant young teen writer to have fun playing with words – or you might simply enjoy playing it yourself.

The word games work in a very similar way to Word Wipe, so if you found that game frustrating, then Words for Evil probably isn’t for you!

#7: First Draft of the Revolution

This game is an interactive story, told in the form of letters (epistolary). It comes at writing from a much more literary angle than many of the other games, and if you’ve studied English literature or creative writing, or if you teach writing, then you might find it particularly interesting.

The graphics are gorgeous – playing the game is like turning the pages of a book. To play First Draft of the Revolution, you make choices about how to rewrite the main character (Juliette’s) draft letters – helping you gain insight into the process of drafting and redrafting, as well as affecting the ongoing story.

#8: Writing Challenge

Writing Challenge can be used alone or with friends, creating a collaborative story by racing against the clock. You can use it as an app on your phone, as well as on your computer, so you can add to your stories at any time.

If you struggle to stay motivated when you’re writing, then Writing Challenge could be a great way to gamify your writing life – and potentially to create collaborative works of fiction.

#9: Plot Generator

Plot Generator works a bit like Mad Libs: you select a particular type of story (e.g. short story, movie script, fairytale) then enter a bunch of words as prompted. The website creates the finished piece for you. There are also options for story ideas (essentially writing prompts), character generators, and much more on the site.

If you’re stuck for an idea, or just want to play around a bit, Plot Generator could be a lot of fun. Some of the options, like Fairy Tale, are great to use with young children – others may not be so suitable, so do vet the different options first.

#10: The Novelist ($9.99)

The Novelist follows the life of Dan Kaplan, a struggling novelist who’s also trying to be a good husband and father. You can make choices about what Dan should do to reach his goals in different areas of his life – and the decisions you make affect what happens next in the game. You are a “ghost” in the house, learning about and influencing the characters.

While there’s not any actual writing involved in the game, it could be a thought-provoking way to explore how writing fits into your own life.

10 Games to Help You Learn to Type

Typing might seem like an odd thing to include on a list of writing games. But so much of writing involves being able to type – and if you’re a slow typist, you’ll find that your fingers can’t keep up with your brain! While most people find that their typing does naturally improve with practice, these games are all quick ways for you (or your kids) to get that practice in a fun way.

Obviously, all of these games should help to improve typing skills: those which involve whole words may also help with spelling and vocabulary. Unless otherwise mentioned, they’re free.

#1: Dance Mat Typing

This game is designed to teach children touch type (type without looking at the keyboard). It starts off with Level 1, teaching you the “home row” (middle row) keys on the keyboard. Other letters are gradually added in as the game progresses.

It’s very much aimed at kids, so teens and adults may find the animated talking goat a bit annoying or patronising! Unlike many other free games, though, it doesn’t include ads.

#2: Spider Typer

This typing game took a while to load for me: you too many find it’s a bit slow. In the game, you type the letters that appear on chameleons that are trying to catch a spider (the chameleons disappear when you hit their letter). The spider keeps rising up into a tree, and if it safely gets there, you move on to the next level.

It’s suitable for kids, and starts off very easy with just letters: if you set it to a harder difficulty, you need to type whole words.

#3: NitroType

This is a competitive typing game where you race a car against friends (or total strangers) by typing the text at the bottom of the screen. It’s a good one for practicing typing whole sentences, including punctuation – not just typing letters or words.

Older children might enjoy it, and any adults with a strong competitive streak! You can compete as a “guest racer”, or you can create an account and login so you can level up and gain rewards like a better car.

#4: TypeRacer

TypeRacer is similar to NitroType: you control a racing car and the faster you type, the faster your car moves. You can practice on your own, enter a typing race, or race against your friends if you prefer.

If you create an account and login, other users can see your username, score, average speed and so on – and they can also send you messages. This could potentially open you up to receiving spam or unwanted communications, so do be aware of this, particularly if you’re allowing your child to play.

#5: The Typing of the Ghosts

In this game, you destroy ghosts by typing the word on them. The graphics are pretty rudimentary, though it is a free game and a good way to practice quickly typing words. It’s suitable for children, and the sound effects (there’s a noise for every letterstroke) may appeal to kids.

You don’t need to create an account or login: you can simply start playing straight away.

#6: Typing Chef

In this game, you type cooking-related words (usually types of equipment). It involves single words and a few double words with a space between at the early levels.

There’s nothing particularly unusual about this game compared with others, though it wasn’t so ad-heavy as some and doesn’t require any registration. It’s good for teaching words and phrases, but not for helping you to learn to type whole sentences.

#7: TypeTastic

This is a fun typing game aimed at young kids, so it starts with the fundamentals. You start by building a keyboard from letter blocks, then learn how to spot letters on the keyboard quickly before learning where those letters are located.

Teachers or parents might be interested in reading about why the game starts with mapping the keyboard. The interface and graphics are pretty good, given that it’s a free game, and it’s designed specifically with young children in mind.

#8: Typer Shark! Delux

This is a free typing game, where you’re a diver exploring the seas. You can choose from different difficulty levels, and – in a mechanic that’s probably by now quite familiar if you’ve played any of the other typing games – you get rid of creatures like sharks by typing the word written on them.

Again, this can help you with your typing speed and accuracy. I found it was a bit slow to load, but it’s not full of ads like some other games.

#9: Typing Attack

In this game, you’re a spaceship, facing enemy spaceships – each with a word written on them. I expect you can guess what you need to do: type the word correctly to destroy the spaceship. Some words are shorter, some longer, and as with other games, there are multiple difficulty settings.

You’ll need to watch an ad before the game loads, which can be annoying, and means that it isn’t necessarily suitable for children.

#10: The Typing of the Dead: Overkill ($14.99)

This game is definitely aimed at adults rather than kids, because it’s a bit gory. It also costs $14.99, so it’s probably one that’ll suit you best if you’re really keen to improve your typing speed – perhaps you do transcription, for instance, or you’re a freelance writer.

To play the game, you type the words that appear in front of the enemies and monsters: each type you type a letter correctly, you send a bullet at them. If you like horror games and films, it could be a fun way to learn to type faster – but it won’t necessarily improve your accuracy with whole sentences.

10 Word Games that Are Particularly Suited to Kids

While I’ve tried to indicate above whether or not the games are suitable for kids, I wanted to list the ten that I’d particularly recommend if you want to help your children get a great start as budding writers.

Several of these are games I play with my five-year-old already; others are games I’m really looking forward to using with her and my son as they get older. I won’t repeat the full descriptions: just scroll back up if you want those.

#1: Word searches (pen and paper) – you can buy whole books of these, or print off free ones. Older kids might have fun creating their own for their friends or siblings.

#2: Bulls and Cows (pen and paper) – you can play this with just a pen and paper (or if you’ve got a really good memory, with nothing at all).

#3: Boggle (board game) – this is simple enough for quite young children to get the hang of it: my five-year-old enjoys playing it with her Granny.

#4: Story Cubes (dice game) – your child can use these on their own to come up with ideas for a story, or you could use them with a group of children – e.g. in a classroom or as part of a club.

#5: Amazing Tales (roleplaying) – this child-friendly RPG is a great way to introduce big-picture storytelling skills, particularly developing a character.

#6: Spellspire (phone app) – a fun spelling/word-creation game your child can play on your phone (and probably a bit more educational than yet another game of Angry Birds).

#7: Wild West Hangman (browser game) – if your child likes hangman but you don’t always have the time to play it with them, this is a good alternative.

#8: First Draft of the Revolution (browser game) – if your teen is interested in writing and/or the French revolution, they might really enjoy this intriguing game based around redrafting letters.

#9: Dance Mat Typing (typing game) – this game from the BBC is high-quality, and designed to appeal to young children. It teaches good typing practice from the start, by explaining correct finger placement on the keys.

#10: TypeTastic – this is another typing game aimed at young children, and this one starts with putting together a keyboard – a great place to begin.

—

Do you have any favourite writing games – of any type? Share them with us in the comments.

It goes without saying that writers are drawn to language, but because we love words so much, the English language is filled with word play. By interrogating the complexities of language—homophones, homographs, words with multiple meanings, sentence structures, etc.—writers can explore new possibilities in their work through a play on words.

It’s easiest to employ word play in poetry, given how many linguistic possibilities there are in poetry that are harder to achieve in prose. Nonetheless, the devices listed in this article apply to writers of all genres, styles, and forms of writing.

After examining different word play examples—such as portmanteaus, malapropisms, and oxymorons—we’ll look at opportunities for how these devices can propel your writing. But first, let’s establish what we mean when we’re talking about a play on words.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Wordplay Definition

Word play, also written as wordplay, word-play, or a play on words, is when a writer experiments with the sound, meaning, and/or construction of words to produce new and interesting meanings. In other words, the writer is twisting language to say something unexpected, with the intent of entertaining or provoking the reader.

Wordplay definition: Experimentation with the sounds, definitions, and/or constructions of words to produce new and interesting meanings.

It should come as no surprise that many word play examples were written by Shakespeare. One such example comes from Hamlet. Some time after Polonius is killed, Hamlet’s uncle, Claudius, asks him where Polonius is. The below exchange occurs:

KING CLAUDIUS

Now, Hamlet, where’s Polonius?

HAMLET

At supper.

KING CLAUDIUS

At supper! where?

HAMLET

Not where he eats, but where he is eaten: a certain

convocation of politic worms are e’en at him. Your

worm is your only emperor for diet: we fat all

creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for

maggots: your fat king and your lean beggar is but

variable service, two dishes, but to one table:

that’s the end.

The line “Not where he eats, but where he is eaten” is a play on words, drawing the audience’s attention to Polonius’ death. He is not eating, but being consumed by the worms. This play on the meaning of “eat” utilizes the verb’s multiple definitions—to consume versus to decompose. (It is also an example of synchysis, and of polyptoton, a type of repetition device.)

The most common of word play examples is the pun. A pun directly plays with the sounds and meanings of words to create new and surprising sentences. For example, “The incredulous cat said you’ve got to be kitten me right meow!” puns on the words “kidding” (kitten) and “now” (meow).

To learn more about puns, check out our article on Pun Examples in Literature. Some of the play on words examples in this article can also count as puns, but because we’ve covered puns in a previous blog, this article covers different and surprising possibilities for twisting and torturing language.

Examples of a Play on Words: 10 Literary Devices

Word play isn’t just a way to have fun with language, it’s also a means of creating new and surprising meanings. By experimenting with the possibilities of sound and meaning, writers can create new ideas that traditional language fails to encompass.

Let’s see word play in action. The following examples of a play on words all come from published works of literature.

1. Word Play Examples: Anthimeria

Anthimeria is a type of word play in which a word is employed using a different part of speech than what is typically associated with that word. (For reference, the parts of speech are: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, articles, interjections, conjunctions, and prepositions.)

Most commonly, a writer using anthimeria will make a verb a noun (nominalization), or make a noun a verb (verbification). It would be much harder to employ this device using other parts of speech: using an adjective as a pronoun, for example, would be difficult to read, even for the reader familiar with anthimeria.

Here are some word play examples using anthimeria:

Nouns to Verbs

The thunder would not peace at my bidding.

—From King Lear, (IV, vi.) by Shakespeare

The word “peace” is being used as a verb, meaning “to calm down.” Many anthimeria examples come to us from Shakespare, in part because of his genius with language, and in part because he needed to use certain words that would preserve the meter of his verse.

“I’ll unhair thy head.”

—From Antony and Cleopatra (II, v.) by Shakespeare

Of course, “unhair” isn’t a word at all. But, it’s using “hair” as a verb, and then using the opposite of that verb, to express scalping someone’s hair off.

Up from my cabin, My sea-gown scarf’d about me, in the dark

Groped I to find out them; had my desire.

—From Hamlet, (V, ii.) by Shakespeare

Shakespeare is using “scarf” as a verb, meaning “to wrap around.” Nowadays, the use of “scarf” as a verb is recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary, but at the time, this was a very new usage of the word.

Verbs to Nouns

It’s difficult to find examples of nominalization in literature, mostly because it’s not a wise decision in terms of writing style. Verbs are the strongest parts of speech: they provide the action of your sentences, and can also provide necessary description and characterization in far fewer words than nouns and adjectives can. Using a verb as a noun only hampers the power of that verb.

Nonetheless, we use verbs as nouns all the time in everyday conversation. If you “hashtag” something on social media, you’re using the noun hashtag as a verb. Or, if you “need a good drink,” you’re noun-ing the verb “drink.” Often, nouns become acceptable dictionary entries for verbs because of the repeated use of nominalizations in everyday speech.

Nouns and Verbs to Adjectives

“The parishioners about here,” continued Mrs. Day, not looking at any living being, but snatching up the brown delf tea-things, “are the laziest, gossipest, poachest, jailest set of any ever I came among.”

—From Under the Greenwood Tree by Thomas Hardy

The words “gossipest, poachest, jailest” might seem silly or immature. But, they’re fun and striking uses of language, and they help characterize Mrs. Day through dialogue.

“I’ll get you, my pretty.”

—From The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

By using the adjective “pretty” as a noun, the witch’s use of anthimeria in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz strikes a chilling note: it’s both pejorative and suggests that the witch could own Dorothy’s beauty.

Anthimeria isn’t just a form of language play, it’s also a means of forging neologisms, which eventually enter the English lexicon. Many words began as anthimerias. For example, the word “typing” used to be a new word, as people didn’t “employ type” until the invention of typing devices, like typewriters. The word “ceiling” comes from an antiquated word “ceil,” meaning sky: “ceiling” means to cover over something, and that verb eventually became the noun we use today.

2. Word Play Examples: Double Entendre

A double entendre is a form of word play in which a word or phrase is used ambiguously, meaning the reader can interpret it in multiple ways. A double entendre usually has a literal meaning and a figurative meaning, with both meanings interacting with each other in some surprising or unusual way.

In everyday speech, the double entendre is often employed sexually. Indeed, writers often use the device lasciviously, and bawdry bards like Shakespeare won’t hesitate when it comes to dirty jokes.

Nonetheless, here a few examples of double entendre that are a little more PG:

“Marriage is a fine institution, but I’m not ready for an institution.”

—Mae West, quoted in The 2,548 Best Things Anybody Ever Said by Robert Byrne

The repeated use of “institution” suggests a double meaning. While marriage is, literally, an institution, West is also suggesting that marriage is an institution in a different sense—like a prison or a psychiatric hospital, one that she’s not ready to commit to.

“What ails you, Polyphemus,” said they, “that you make such a noise, breaking the stillness of the night, and preventing us from being able to sleep? Surely no man is carrying off your sheep? Surely no man is trying to kill you either by fraud or by force?”But Polyphemus shouted to them from inside the cave, “No man is killing me by fraud; no man is killing me by force.”

“Then,” said they, “if no man is attacking you, you must be ill; when Jove makes people ill, there is no help for it, and you had better pray to your father Neptune.”

—Odyssey by Homer

In Homer’s Odyssey, the hero, Odysseus, tells the cyclops Polyphemus that his name is “no man.” Then, when Odysseus blinds Polyphemus, the cyclops is enraged and tells people that “no man” did this, suggesting that his blindness is an affliction from the gods. In this instance, Polyphemus means one thing but communicates another, causing humorous ambiguity for the audience.

On the contrary, Aunt Augusta, I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital importance of being Earnest.

—The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People by Oscar Wilde

In Oscar Wilde’s play, the protagonist Jack Worthing leads a double life: to his lover in the countryside, he’s Jack, while he’s Ernest to his lover in the city. The play follows this character’s deceptions, as well as his realization of the necessity of being true to himself. Thus, in this final line of the play, Jack realizes the importance of being “earnest,” a pun and double entendre on “Ernest.”

3. Word Play Examples: Kenning

The kenning is a type of metaphor that was popular among medieval poets. It is a phrase, usually two nouns, that describes something figuratively, often using words only somewhat related to the object being described.

If you’ve read Beowulf, you’ve seen the kenning in action—and you know that, in translation, some kennings are easier understood than others. For example, the ocean is often described as the “whale path,” which makes sense. But a dragon is described as a “mound keeper,” and if you don’t know that dragons in literature tend to hoard piles of gold, it might be harder to understand this kenning.

A kenning is constructed with a “base word” and a “determinant.” The base word has a metaphoric relationship with the object being described, and the determinant modifies the base word. So, in the kenning “whale path,” the “path” is the base word, as it’s a metaphor for the sea. “Whale” acts as a determinant, cluing the reader towards the water.

The kenning is a play on words because it uses marginally related nouns to describe things in new and exciting language. Here are a few examples:

Kenning In Beowulf

At some point in the text of Beowulf, the following kennings occur:

- Battle shirt — armor

- Battle sweat — blood

- Earth hall — burial mound

- Helmet bearer — warrior

- Raven harvest — corpse

- Ring giver — king

- Sail road — the sea

- Sea cloth — sail

- Sky candle — the sun

- Sword sleep — death

Don’t be too surprised by all of the references to fighting and death. Most of Beowulf is a series of battles, and given that the story developed across centuries of Old English, much of the epic poem explores God, glory, and victory.

Kenning Elsewhere in Literature

The majority of kennings come from Old English poetry, though some contemporary poets also employ the device in their work. Here are a few more kenning word play examples.

So the earth-stepper spoke, mindful of hardships,

of fierce slaughter, the fall of kin:

Oft must I, alone, the hour before dawn

lament my care. Among the living

none now remains to whom I dare

my inmost thought clearly reveal.

I know it for truth: it is in a warrior

noble strength to bind fast his spirit,

guard his wealth-chamber, think what he will.

—”The Wanderer” (Anonymous)

“The Wanderer” is a poem anonymously written and preserved in a codex called The Exeter Book, a manuscript from the late 900s. It contains approximately ⅙ of the Old English poetry we know about today. In this poem, an “earth-stepper” is a person, and a “wealth-chamber” is the wanderer’s mind or heart—wherever it is that he stores his immaterial virtues.

No, they’re sapped and now-swept as my sea-wolf’s love-cry.

—from “Cuil Cliffs” by Ian Crockatt

Ian Crockatt is a contemporary poet and translator from Scotland, and his work with Old Norse poetry certainly influences his own poems. “Sea wolf” is a kenning for “sailor,” and a “love cry” is a love poem.

There is a singer everyone has heard,Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again.

He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

Mid-summer is to spring as one to ten.

He says the early petal-fall is past

When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

On sunny days a moment overcast;

And comes that other fall we name the fall.

He says the highway dust is over all.

The bird would cease and be as other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to make of a diminished thing.

—“The Oven Bird” by Robert Frost

In this Frost sonnet, the speaker employs the kenning “petal-fall” to describe the autumn. The full text of the poem has been included, not for any particular reason, other than it’s simply a lovely, striking poem.

4. Word Play Examples: Malapropism

A malapropism is a device primarily used in dialogue. It is employed when the correct word in a sentence is replaced with a similar-sounding word or phrase that has an entirely different meaning.

For example, the word “assimilation” sounds a lot like the phrase “a simulation.” Employing a malapropism, I might have a character say “Everything is programmed. We all live in assimilation.”

For the most part, malapropisms are humorous examples of a play on words. They often make fun of people who use pretentious language to sound intelligent. But, in everyday speech, we probably employ more malapropisms than we think, so this device also emulates real speech.

The name “malapropism” comes from the play The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. In it, the character Mrs. Malaprop often uses words with opposite meanings but similar sounds to the word she intends. Here’s an example from the play:

“He is the very pineapple of politeness!” (Instead of pinnacle.)

Malapropisms are also known as Dogberryisms (from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing), or as acyrologia. Though this word play device is employed humorously, it also demonstrates the complex relationship our brain has with language, and how easy it is to mix words up phonetically.

5. Word Play Examples: Metalepsis

Metalepsis is the use of a figure of speech in a new or surprising context, creating multiple layers of meaning. In other words, the writer takes a figure of speech and employs it metaphorically, using that figure of speech to reference something that is otherwise unspoken.

This is a tricky literary device to define, so let’s look at an example right away:

As he swung toward them holding up the handHalf in appeal, but half as if to keep

The life from spilling…

—“Out, Out” by Robert Frost

The expected phrase here would be “the blood from spilling.” But, in this excerpt, “life” replaces the word “blood.” The word life, then, becomes a metonymy for “blood,” and as this displacement occurs in the common phrase “spilled blood,” “life” becomes a metalepsis.

So, there are two layers of meaning going on here. One is the meaning derived from the phrase “spilled blood,” and the other comes from the use of “life” to represent “blood.” In any metalepsis, there are multiple layers of meaning occurring, as a metaphor or metonymy is employed to modify a figurative phrase, adding complexity to the phrase itself.

This is a tricky, advanced example of word play, and it primarily occurs in poetry. Here are a few other examples in literature:

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?”

—Dr. Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Here, the face in question is that of Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman in the world (according to The Iliad and the Odyssey). Helen is claimed by Paris, a prince of Troy, and when he takes Helen home with him, it incites the Trojan war—thus the references to a thousand ships and the towers of Ilium. So, the face refers to Helen, and Faustus describes the beauty of that face tangentially, referencing the magnitude of the Trojan War.

“And I also have given you cleanness of teeth in all your cities.”

—The Book of Amos (4:6)

In this Biblical passage, the phrase “cleanness of teeth” is actually referencing hunger. By having nothing to eat, the people have nothing to stain their teeth with. Thus, the figurative image of clean teeth becomes a metalepsis for starvation.

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

—Macbeth (V; v), by Shakespeare

This is a complex extended metaphor and metalepsis. Instead of saying “to the ends of time,” Shakespeare modifies this phrase to “the last syllable of recorded time.” He then extends this idea by saying that life is “a walking shadow, a poor player”—in other words, that which speaks the syllables of recorded time, and then never speaks again. By describing life as an idiot which signifies nothing, Macbeth is saying that life has no inherent value or meaning, and that all men are fools who exist at the whim of a random universe.

Note: this soliloquy arrives after the death of Macbeth’s wife, and it clues us towards Macbeth’s growing madness. So, yes, it’s a very dark passage, but dark for a reason.

To summarize: a metalepsis is a type of word play in which the writer describes something using a tangentially related image or figure of speech. It is, put most succinctly, a metonymy of a metonymy. There is also a narratological device called metalepsis, but it has nothing to do with this particular literary device.

6. Word Play Examples: Oxymoron

An oxymoron is a self-contradictory phrase. It is usually just two words long, with each word’s definition contrasting the other one’s, despite the apparent meaning of the words themselves. It is a play on words because opposing meanings are juxtaposed to form a new, seemingly-impossible idea.

A common example of this is the phrase “virtual reality.” Well, if it’s virtual, then it isn’t reality, just a simulation of a new reality. Nonetheless, we employ those words together all the time, and in fact, the juxtaposition of these incompatible terms creates a new, interesting meaning.

Oxymorons occur all the time in everyday speech. “Same difference,” “Only option,” “live recording,” and even the genre “magical realism.” In any of these examples, a new meaning forms from the placement of these incongruous words.

Here are a few examples from literature:

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.”

—Romeo and Juliet (II; ii), by Shakespeare

“No light; but rather darkness visible”

—Paradise Lost by John Milton

“Their traitorous trueness, and their loyal deceit.”

—“The Hound of Heaven” by Francis Thompson

Note: an oxymoron is not self-negating, but self-contradictory. The use of opposing words should mean that each word cancels the other out, but in a good oxymoron, a new meaning is produced amidst the contradictions. So, you can’t just put two opposing words together: writing “the healthy sick man,” for example, doesn’t mean anything, unless maybe it’s placed into a very specific context. An oxymoron should produce new meaning on its own.

7. Word Play Examples: Palindrome

The palindrome is a word play device not often employed in literature, but it is language at its most entertaining, and can provide interesting challenges to the daring poet or storyteller.

A palindrome is a word or phrase that is spelled the exact same forwards and backwards (excluding spaces). The word “racecar,” for example, is spelled the same in both directions. So is the phrase “Able was I ere I saw Elba.” So is the sentence “A man, a plan, a canal, Panama.”

The longer a palindrome gets, the less likely it is to make sense. Take, for example, the poem “Dammit I’m Mad” by Demetri Martin. It’s a perfect palindrome, but, although there are some striking examples of language (for example, “A hymn I plug, deified as a sign in ruby ash”), much of the word choice is nonsensical.

Because of this, there are also palindromes that occur at the line-level. Meaning, the words cannot be read forwards and backwards, but the lines of a poem are the same forwards and backwards. The poem “Doppelganger” by James A. Lindon is an example.

Want to challenge yourself? Write a palindrome that tells a cohesive story. You’ll be playing with both the spellings of words and with the meanings that arise from unconventional word choice. Good luck!

8. Word Play Examples: Paraprosdokian

A paraprosdokian is a play on words where the writer diverts from the expected ending of a sentence. In other words, the writer starts a sentence with a predictable ending, but then supplies a new, unexpected ending that complicates the original meanings of the words and surprises the reader.

Here’s an example sentence: “Is there anything that mankind can’t accomplish? We’ve been to the moon, eradicated polio, and made grapes that taste like cotton candy.” This last clause is a paraprosdokian: the reader expects the list to contain great, life-altering achievements, but ending the list with something a bit more trivial, like cotton candy grapes, is a humorous and unexpected twist.

With the paraprosdokian, writers contort the expected endings of sentences to create surprising juxtapositions, playing with both words and sentence structures. Here are a few literary examples, with the paraprosdokian in bold:

By the time you swear you’re his,

Shivering and sighing,

And he vows his passion is

Infinite, undying—

Lady, make a note of this:

One of you is lying.

—“Unfortunate Coincidence” by Dorothy Parker

“By the wide lake’s margin I mark’d her lie –The wide, weird lake where the alders sigh –

A young fair thing, with a shy, soft eye;

And I deem’d that her thoughts had flown …

All motionless, all alone.

Then I heard a noise, as of men and boys,

And a boisterous troop drew nigh.

Whither now will retreat those fairy feet?

Where hide till the storm pass by?

On the lake where the alders sigh …

For she was a water-rat.”

—“Shelter” by Charles Stuart Calverley

9. Word Play Examples: Portmanteau

A portmanteau is a word which combines two distinct words in both sound and meaning. “Smog,” for example, is a portmanteau of both “smoke” and “fog,” because both the sounds of the words are combined as well as the definition of each word.

The portmanteau has become a popular marketing tactic in recent years. A portmanteau is also, often, an example of a neologism—a coined word for which new language is necessary to describe new things.

Here are a few portmanteaus that have recently entered the English lexicon:

- Fanzine (fan + magazine)

- Telethon (telephone + marathon)

- Camcorder (camera + recorder)

- Blog (web + log)

- Vlog (video + blog)

- Staycation (stay + vacation)

- Bromance (brother + romance)

- Webinar (web + seminar)

- Hangry (hungry + angry)

- Cosplay (costume + play)

Lewis Carroll popularized the portmanteau, but a work of fiction that’s rife with this word play is Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce. The novel—which is notoriously difficult to read due to its use of foreign words, as well as its disregard for conventional spelling and syntax—has coined portmanteaus like “ethiquetical” (ethical + etiquette), “laysense” (layman + sense), and “fadograph” (fading + photograph).

10. Word Play Examples: Spoonerism

A spoonerism occurs when the initial sounds of two neighboring words are swapped. For instance, the phrase “blushing crow” is a spoonerism of “crushing blow.”

Often, spoonerisms are slips of the tongue. We might confuse our syllables when we speak, which is a natural result of our brains’ relationships to language.

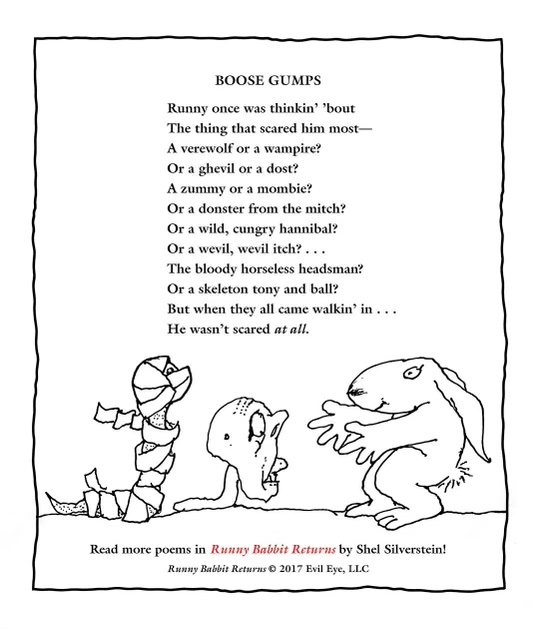

Spoonerisms can be literary examples of a play on words. But they’re also just ways to have fun with language. An example is Shel Silverstein’s posthumous collection of children’s poems Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook.

How to Use a Play on Words in Your Writing

Writers can utilize word play for two different strategies: literary effect, and creative thinking.

When it comes to literary effect, a play on words can surprise, delight, provoke, and entertain the reader. Devices like oxymoron, metalepsis, and kenning offer new, innovative possibilities in language, and a strong example of these devices can move the reader in a way that ordinary language cannot.

Word play can also stimulate your own creativity. If you experiment with language using literary devices, you might stumble upon the following:

- A title for your work.

- Character names.

- Witty dialogue.

- Interesting or provocative description.

- The core idea of a poem or short story.

I’ll give a personal example. Once, in a fiction course, I was struggling to come up with an idea for a short story. A friend and I ended up bouncing words around and came up with the phrase “psychic psychiatrist” (an example of alliteration and polyptoton). Just playing with words like this was enough to inspire me to write a story about exactly that, a psychiatrist who predicts the future for their clients without realizing it.

Titles like The Importance of Being Earnest (a self-referential pun), “Dammit I’m Mad” (palindrome), or Back to the Future (oxymoron) all use word play to frame and guide the story or poem. You might find inspiration for your own work by considering, with careful attention and an appreciation for language, the many possibilities of a play on words.

Experiment with Word Play at Writers.com

The instructors at Writers.com are masters of word play. Not only do we love words, we love to mess with them in surprising and innovative ways. If you want to formulate new ideas for your work, take a look at our upcoming online writing classes, where you’ll receive expert instruction on all the work you write and submit.