Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

Best Answer

Copy

The word is «krime’nos»,»krime’ni»,»krime’no» for a male, a

female and a natural subject respectively.

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the greek word for hidden?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

| Kryptos | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Artist | Jim Sanborn |

| Year | 1990 |

| Location | Langley, Virginia |

| 38°57′08″N 77°08′45″W / 38.95227°N 77.14573°WCoordinates: 38°57′08″N 77°08′45″W / 38.95227°N 77.14573°W |

Kryptos is a sculpture by the American artist Jim Sanborn located on the grounds of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters, the George Bush Center for Intelligence in Langley, Virginia. Since its dedication on November 3, 1990, there has been much speculation about the meaning of the four encrypted messages it bears. Of these four messages, the first three have been solved, while the fourth message remains one of the most famous unsolved codes in the world. The sculpture continues to be of interest to cryptanalysts, both amateur and professional, who are attempting to decipher the fourth passage. The artist has so far given four clues to this passage.

Description[edit]

Close-up view of part of the text

The main part of the sculpture is located in the northwest corner of the New Headquarters Building courtyard, outside of the Agency’s cafeteria. The sculpture comprises four large copper plates with other elements consisting of water, wood, plants, red and green granite, white quartz, and petrified wood. The most prominent feature is a large vertical S-shaped copper screen resembling a scroll or a piece of paper emerging from a computer printer, half of which consists of encrypted text. The characters are all found within the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, along with question marks, and are cut out of the copper plates. The main sculpture contains four separate enigmatic messages, three of which have been deciphered.[1]

In addition to the main part of the sculpture, Jim Sanborn also placed other pieces of art at the CIA grounds, such as several large granite slabs with sandwiched copper sheets outside the entrance to the New Headquarters Building. Several morse code messages are found on these copper sheets, and one of the stone slabs has an engraving of a compass rose pointing to a lodestone. Other elements of Sanborn’s installation include a landscaped garden area, a fish pond with opposing wooden benches, a reflecting pool, and other pieces of stone including a triangle-shaped black stone slab.

The name Kryptos comes from the ancient Greek word for «hidden», and the theme of the sculpture is «Intelligence Gathering».

The cost of the sculpture in 1988 was US $250,000 (worth US $501,000 in 2016).[2]

Encrypted messages[edit]

The ciphertext on the left-hand side of the sculpture (as seen from the courtyard) of the main sculpture contains 869 characters in total: 865 letters and 4 question marks (spacing is important).

In April 2006, however, Sanborn released information stating that a letter was omitted from this side of Kryptos «for aesthetic reasons, to keep the sculpture visually balanced».[3]

There are also three misspelled words in the plaintext of the deciphered first three passages, which Sanborn has said was intentional,[3] and three letters (YAR) near the beginning of the bottom half of the left side are the only characters on the sculpture in superscript.

The right-hand side of the sculpture comprises a keyed Vigenère encryption tableau, consisting of 867 letters.

One of the lines of the Vigenère tableau has an extra character (L). Bauer, Link, and Molle[4] suggest that this may be a reference to the Hill cipher as an encryption method for the fourth passage of the sculpture. However, Sanborn omitted the extra letter from small Kryptos models that he sold.

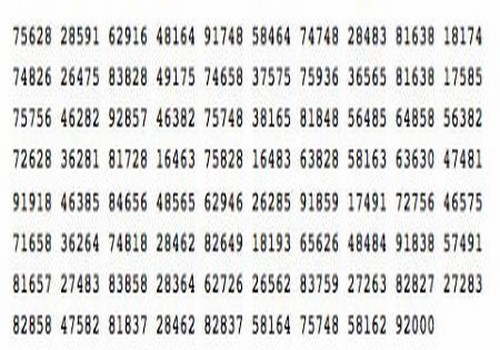

EMUFPHZLRFAXYUSDJKZLDKRNSHGNFIVJ YQTQUXQBQVYUVLLTREVJYQTMKYRDMFD VFPJUDEEHZWETZYVGWHKKQETGFQJNCE GGWHKK?DQMCPFQZDQMMIAGPFXHQRLG TIMVMZJANQLVKQEDAGDVFRPJUNGEUNA QZGZLECGYUXUEENJTBJLBQCRTBJDFHRR YIZETKZEMVDUFKSJHKFWHKUWQLSZFTI HHDDDUVH?DWKBFUFPWNTDFIYCUQZERE EVLDKFEZMOQQJLTTUGSYQPFEUNLAVIDX FLGGTEZ?FKZBSFDQVGOGIPUFXHHDRKF FHQNTGPUAECNUVPDJMQCLQUMUNEDFQ ELZZVRRGKFFVOEEXBDMVPNFQXEZLGRE DNQFMPNZGLFLPMRJQYALMGNUVPDXVKP DQUMEBEDMHDAFMJGZNUPLGEWJLLAETG |

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCD AKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYP BRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPT CYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTO DPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOS ETOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSA FOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSAB GSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABC HABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCD IBCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDE JCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEF KDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFG LEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGH MFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHI |

ENDYAHROHNLSRHEOCPTEOIBIDYSHNAIA CHTNREYULDSLLSLLNOHSNOSMRWXMNE TPRNGATIHNRARPESLNNELEBLPIIACAE WMTWNDITEENRAHCTENEUDRETNHAEOE TFOLSEDTIWENHAEIOYTEYQHEENCTAYCR EIFTBRSPAMHHEWENATAMATEGYEERLB TEEFOASFIOTUETUAEOTOARMAEERTNRTI BSEDDNIAAHTTMSTEWPIEROAGRIEWFEB AECTDDHILCEIHSITEGOEAOSDDRYDLORIT RKLMLEHAGTDHARDPNEOHMGFMFEUHE ECDMRIPFEIMEHNLSSTTRTVDOHW?OBKR UOXOGHULBSOLIFBBWFLRVQQPRNGKSSO TWTQSJQSSEKZZWATJKLUDIAWINFBNYP VTTMZFPKWGDKZXTJCDIGKUHUAUEKCAR |

NGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJL OHIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJL PIJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLM QJLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMN RLMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQ SMNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQU TNQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUV UQUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVW VUVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWX WVWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZ XWXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZK YXZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKR ZZKRYPTOSABCDEFGHIJLMNQUVWXZKRY ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCD |

Sanborn worked with a retiring CIA employee named Ed Scheidt, Chairman of the CIA Office of Communications, to come up with the cryptographic systems used on the sculpture.[5]

Sanborn has revealed that the sculpture contains a riddle within a riddle, which will be solvable only after the four encrypted passages have been deciphered.[5]

He has given conflicting information about the sculpture’s answer, saying at one time that he gave the complete solution to the then-CIA director William Webster during the dedication ceremony; but later, he also said that he had not given Webster the entire solution. He did, however, confirm that a passage of the plaintext of the second message reads «Who knows the exact location? Only WW.»

Sanborn also confirmed that should he die before the entire sculpture becomes deciphered, there will be someone able to confirm the solution.[6] In 2020, Sanborn stated that he planned to put the secret to the solution up for auction once he dies.[7]

Solvers[edit]

The first person to announce publicly that he had solved the first three passages was Jim Gillogly, a computer scientist from southern California, who deciphered these passages using a computer, and revealed his solutions in 1999.[8]

After Gillogly’s announcement, the CIA revealed that their analyst David Stein had solved the same passages in 1998 using pencil and paper techniques, although at the time of his solution the information was only disseminated within the intelligence community.[9] No public announcement was made until July 1999,[10][11] although in November 1998 it was revealed that «a CIA analyst working on his own time [had] solved the lion’s share of it».[12]

The NSA claimed that some of their employees had solved the same three passages but would not reveal names or dates until March 2000, when it was learned that an NSA team led by Ken Miller, along with Dennis McDaniels and two other unnamed individuals, had solved passages 1–3 in late 1992.[13] In 2013, in response to a Freedom of Information Act request by Elonka Dunin, the NSA released documents that show these attempts to solve the Kryptos puzzle in 1992, following a challenge by Bill Studeman, then Deputy Director of the CIA. The documents show that by June 1993, a small group of NSA cryptanalysts had succeeded in solving the first three passages of the sculpture.[14][15]

The above attempts to solve Kryptos all had found that passage 2 ended with WESTIDBYROWS. However, in 2005, Dr Nicole Friedrich, a logician from Vancouver, Canada, determined that another possible plaintext was: WESTPLAYERTWO.[16] Dr. Friedrich solved the ending to section K2 from a clue that became apparent after she had determined a running cipher of K4 that resulted in an incomplete but partially legible K4 plaintext, involving text such as XPIST, REALIZE, AYD EQ HR, and others, but the find that instigated her discovery of K2 plaintext was the clue WESTX.

On April 19, 2006, Sanborn contacted an online community dedicated to the Kryptos puzzle to inform them that what was once the accepted solution to passage 2 was incorrect. Sanborn said that he made an error in the sculpture by omitting an S in the ciphertext (an X in the plaintext), and he confirmed that the last passage of the plaintext was WESTXLAYERTWO, and not WESTIDBYROWS.[17]

Solutions[edit]

The following are the solutions of passages 1–3 of the sculpture.[18]

Misspellings present in the text are included verbatim.

Solution of passage 1[edit]

Method: Vigenère

Keywords: Kryptos, Palimpsest

BETWEEN SUBTLE SHADING AND THE ABSENCE OF LIGHT LIES THE NUANCE OF IQLUSION

Iqlusion was an intentional misspelling of illusion.[19][20]

Solution of passage 2[edit]

Method: Vigenère

Keywords: Kryptos, Abscissa

IT WAS TOTALLY INVISIBLE HOWS THAT POSSIBLE ? THEY USED THE EARTHS MAGNETIC FIELD X THE INFORMATION WAS GATHERED AND TRANSMITTED UNDERGRUUND TO AN UNKNOWN LOCATION X DOES LANGLEY KNOW ABOUT THIS ? THEY SHOULD ITS BURIED OUT THERE SOMEWHERE X WHO KNOWS THE EXACT LOCATION ? ONLY WW THIS WAS HIS LAST MESSAGE X THIRTY EIGHT DEGREES FIFTY SEVEN MINUTES SIX POINT FIVE SECONDS NORTH SEVENTY SEVEN DEGREES EIGHT MINUTES FORTY FOUR SECONDS WEST X LAYER TWO

The coordinates mentioned in the plaintext, 38°57′6.5″N 77°8′44″W / 38.951806°N 77.14556°W, have been interpreted using a modern Geodetic datum as indicating a point that is approximately 174 feet (53 meters) southeast of the sculpture.[1]

Solution of passage 3[edit]

Method: Transposition

SLOWLY DESPARATLY SLOWLY THE REMAINS OF PASSAGE DEBRIS THAT ENCUMBERED THE LOWER PART OF THE DOORWAY WAS REMOVED WITH TREMBLING HANDS I MADE A TINY BREACH IN THE UPPER LEFT HAND CORNER AND THEN WIDENING THE HOLE A LITTLE I INSERTED THE CANDLE AND PEERED IN THE HOT AIR ESCAPING FROM THE CHAMBER CAUSED THE FLAME TO FLICKER BUT PRESENTLY DETAILS OF THE ROOM WITHIN EMERGED FROM THE MIST X CAN YOU SEE ANYTHING Q ?

This is a paraphrased quotation from Howard Carter’s account of the opening of the tomb of Tutankhamun on November 26, 1922, as described in his 1923 book The Tomb of Tutankhamun. The question with which it ends is asked by Lord Carnarvon, to which Carter (in the book) famously replied «wonderful things». In the November 26, 1922, field notes, however, his reply was, «Yes, it is wonderful».[21]

Clues given for passage 4[edit]

The Mengenlehreuhr may be the “Berlin Clock” the encrypted message references.

When commenting in 2006 about his error in passage 2, Sanborn said that the answers to the first three passages contain clues to the fourth passage.[22] In November 2010, Sanborn released a clue, publicly stating that «NYPVTT», the 64th–69th letters in passage four, become «BERLIN» after decryption.[23][24]

Sanborn gave The New York Times another clue in November 2014: the letters «MZFPK», the 70th–74th letters in passage four, become «CLOCK» after decryption.[25] The 74th letter is K in both the plaintext and ciphertext, meaning that it is possible for a character to encrypt to itself. This means it does not have the weakness, where a character could never be encrypted as itself, that was known to be inherent in the German Enigma machine.

Sanborn further stated that in order to solve passage 4, «You’d better delve into that particular clock,» but added, «There are several really interesting clocks in Berlin.»[26] The particular clock in question is presumably the Berlin Clock, although the Alexanderplatz World Clock and Clock of Flowing Time are other candidates.

The clock in Berlin referred to may be a time that is famous in the history of World War 2. «This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note, stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.»

- — Neville Chamberlain, 3 September 1939

In an article published on January 29, 2020, by the New York Times, Sanborn gave another clue: at positions 26–34, ciphertext «QQPRNGKSS» is the word «NORTHEAST».[7]

In August 2020, Sanborn revealed that the four letters in positions 22–25, ciphertext «FLRV», in the plaintext are «EAST». Sanborn commented that he «released this layout to several people as early as April». The first person known to have shared this hint more widely was Sukhwant Singh.[27]

There are some suggestions about the relationship between K4 and the Enigma machine. The initial German Patent of the Enigma machine is DE385682 (19 May 1922).[28] The number 385682 closely resembles the coordinates «38°57′6.5″N 77°8′44″W / 38.951806°N 77.14556°W, LAYER 2″ shown in the K2 plain text, and the scene depicted in the K3 plain text (Opening Tutankhamun’s Tomb by Howard Carter) occurred in the same year 1922.

[edit]

Kryptos was the first cryptographic sculpture made by Sanborn.

After producing Kryptos he went on to make several other sculptures with codes and other types of writing, including one entitled Antipodes, which is at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., an «Untitled Kryptos Piece» that was sold to a private collector, and Cyrillic Projector, which contains encrypted Russian Cyrillic text that included an extract from a classified KGB document.

The cipher on one side of Antipodes repeats the text from Kryptos. Much of the cipher on Antipodes‘ other side is duplicated on Cyrillic Projector. The Russian portion of the cipher found on Cyrillic Projector and Antipodes was solved in 2003 by Frank Corr and Mike Bales independently from each other with translation from Russian plaintext provided by Elonka Dunin.[29]

Ex Nexum was installed in 1997 at Little Rock Old U.S. Post Office & Courthouse.

Some additional sculptures by Sanborn include Native American texts: Rippowam[30] was installed at the University of Connecticut, in Stamford in 1999, while Lux was installed in 2001 at an old US Post Office building in Fort Myers, Florida.[31] Iacto is located at the University of Iowa, between the Adler Journalism Building and Main Library.[32]

Indian Run is located next to the U.S. Federal Courthouse in Beltsville, Maryland, and contains a bronze cylinder perforated with the text of the Iroquois Book of the Great Law.

This document includes the contribution of the indigenous peoples to the United States legal system.[33]

The text is written in Onondaga and was transcribed from the ancient oral tradition of five Iroquois nations.[34]

A,A was installed at the Plaza in front of the new library at the University of Houston, in Houston, Texas, in 2004, and Radiance was installed at the Department of Energy, Coast, and Environment, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge in 2008.[31]

In popular culture[edit]

The dust jacket of the US version of Dan Brown’s 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code contains two references to Kryptos—one on the back cover (coordinates printed light red on dark red, vertically next to the blurbs) is a reference to the coordinates mentioned in the plaintext of passage 2 (see above), except the degrees digit is off by one. When Brown and his publisher were asked about this, they both gave the same reply: «The discrepancy is intentional». The coordinates were part of the first clue of the second Da Vinci Code WebQuest, the first answer being Kryptos. The other reference is hidden in the brown «tear» artwork—upside-down words which say «Only WW knows», which is another reference to the second message on Kryptos.[2][35]

Kryptos features in Dan Brown’s 2009 novel The Lost Symbol.[1]

A small version of Kryptos appears in the season 5 episode of Alias «S.O.S.». In it, Marshall Flinkman, in a small moment of comic relief, says he has cracked the code just by looking at it during a tour visit to the CIA office. The solution he describes sounds like the solution to the first two parts.

In the season 2 episode of The King of Queens «Meet By-Product», a framed picture of Kryptos hangs on the wall by the door.

The progressive metal band Between the Buried and Me has a reference to Kryptos in their song «Obfuscation» from their 2009 album, The Great Misdirect.

Kryptos features in several of M. L. Buchman’s Miranda Chase series titles including Drone, Thunderbird, Ghostrider, and White Top.

James Ponti’s young adult novel City Spies: City of the Dead uses Kryptos and the online community of cryptographers seeking to solve K4 as a means of passing messages between a cryptographer and a deep cover spy.

See also[edit]

- A,A

- Copiale cipher

- History of cryptography

- Voynich manuscript

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Secrets of the Lost Symbol, pp.319–326

- ^ a b «FAQ About Kryptos». Elonka.com. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ a b Zetter, Kim. «Typo Confounds Kryptos Sleuths» Wired April 20, 2006

- ^ Bauer, Link, and Molle, 2016, p. 548.

- ^ a b Champagne, Christine; Beebe, Drew (July 25, 2020). «This sculpture at CIA headquarters holds one of the world’s most famous unsolved mysteries». CNN. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Zetter, Kim. «Questions for Kryptos’ Creator,» Wired (January 20, 2005).

- ^ a b «This Sculpture Holds a Decades-Old C.I.A. Mystery. And Now, Another Clue». New York Times. January 29, 2020.

- ^ Markoff, John (June 16, 1999). «CIA’s Artistic Enigma Reveals All but Final Clues». New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ Stein, David D. (1999). «The Puzzle at CIA Headquarters: Cracking the Courtyard Crypto» (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 43 (1).

- ^ «Cracking the Code of a CIA Sculpture». Washington Post. July 19, 1999. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ Zetter, Kim. «CIA Releases Analyst’s Fascinating Tale of Cracking the Kryptos Sculpture». Wired. Wired.com. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ Bessonette, Colin (November 16, 1998). «Q&A on the News». The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. A2.

A CIA analyst working on his own time has solved the lion’s share of it, but it hasn’t been completely decoded, CIA spokesman Mark Mansfield told Q&A. He said the best way to describe the sculpture is to say it incorporates natural building materials native to America and includes an encoded copper screen. When and if someone completely solves the message, a decision will be made about releasing it to the public, «but we’re not at that point yet,» Mansfield said.

- ^ Bowman, Tom (March 17, 2000). «Unlocking the secret of ‘Kryptos’«. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ Zetter, Kim (July 10, 2013). «Documents Reveal How the NSA Cracked the Kryptos Sculpture Years Before the CIA». wired.com.

- ^ Sadowski, Jathan (July 11, 2013). «NSA Cracked Kryptos Before the CIA. What Other Mysteries Has It Solved?». slate.com.

- ^ «From a radio interview on BellCoreRadio, season 1, episode 32, Barcode Brothers». 2005-10-11. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Zetter, Kim (20 November 2014). «Finally, a New Clue to Solve the CIA’s Mysterious Kryptos Sculpture». Wired. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

in 2006, Sanborn realized he had also made an inadvertent error, a missing «x» that he mistakenly deleted from the end of a line in passage 2, a passage that was already solved.

- ^ Corey Lindsly. «Kryptos: The Sanborn Sculpture at CIA Headquarters». Elonka.com. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Zetter, Kim (10 July 2013). «Documents Reveal How the NSA Cracked the Kryptos Sculpture Years Before the CIA». Wired. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Schwartz, John; Corum, Jonathan (January 29, 2020). «This Sculpture Holds a Decades-Old C.I.A. Mystery. And Now, Another Clue». The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ [1] Archived May 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zetter, Kim (April 20, 2006). «Typo Confounds Kryptos Sleuths». Wired.com. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ Schwartz, John (2010-11-20). «Artist releases clue to Kryptos». The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ All Things Considered. «‘Kryptos’ Sculptor Drops New Clue In 20-Year Mystery». NPR. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ «A New Clue to ‘Kryptos’«. The New York Times. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Schwartz, John (November 20, 2014). «Sculptor Offers Another Clue in 24-Year-Old Mystery at C.I.A.» The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ John Schwartz (23 August 2020). «Kryptos News». Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ «Enigma Patents». Crypto Museum. 2009-09-10. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ Cyrillic Riddle Solved Science, vol 302, 10 Oct. 2003, page 224

- ^ «127. UConn Public Art Collection (8 of 30)». ctmuseumquest.com.

- ^ a b «Jim Sanborn: The Artist’s Official Site». jimsanborn.net.

- ^ «Iacto | Facilities Management». www.facilities.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ «H. Con. Res. 331, October 21, 1988» (PDF). United States Senate. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ^ «Sanborn’s Indian Run Artwork». elonka.com.

- ^ McKinnon, John D. (May 27, 2005). «CIA sculpture ‘kryptos’ draws mystery lovers». Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

References[edit]

Books[edit]

- Jonathan Binstock and Jim Sanborn (2003). Atomic Time: Pure Science and Seduction. ISBN 0-88675-072-5. (contains 1–2 pages about Kryptos)

- Dunin, Elonka (2006). The Mammoth Book of Secret Codes and Cryptograms. Constable & Robinson. p. 500. ISBN 0-7867-1726-2.

- Dunin, Elonka (2009). «Kryptos: The Unsolved Enigma». In Daniel Burstein; Arne de Keijzer (eds.). Secrets of the Lost Symbol: The Unauthorized Guide to the Mysteries Behind The Da Vinci Code Sequel. HarperCollins. pp. 319–326. ISBN 978-0-06-196495-4.

- Dunin, Elonka (2009). «Art, Encryption, and the Preservation of Secrets: An interview with Jim Sanborn». In Daniel Burstein; Arne de Keijzer (eds.). Secrets of the Lost Symbol: The Unauthorized Guide to the Mysteries Behind The Da Vinci Code Sequel. HarperCollins. pp. 294–300. ISBN 978-0-06-196495-4.

- Taylor, Greg (2009). «Decoding Kryptos«. In John Weber (ed.). Illustrated Guide to the Lost Symbol. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-2366-6.

Journal articles[edit]

- Bauer, Craig; Link, Gregory; Molle, Dante (2016). «James Sanborn’s Kryptos and the matrix encryption conjecture». Cryptologia. 40 (5): 541–552. doi:10.1080/01611194.2016.1141556. S2CID 26592088.

Conference papers[edit]

- Bean, Richard (2021). Cryptodiagnosis of «Kryptos K4». 4th International Conference on Historical Cryptology HistoCrypt. doi:10.3384/ecp183153.

Articles[edit]

- Kryptos 1,735 Alphabetical letters

- «Gillogly Cracks CIA Art», & «The Kryptos Code Unmasked», 1999, New York Times and Cypherpunks archive

- «Unlocking the secret of Kryptos«, March 17, 2000, Sun Journal

- «Solving the Enigma of Kryptos», January 26, 2005, Wired, by Kim Zetter

- «Interest grows in solving cryptic CIA puzzle after link to Da Vinci Code«, June 11, 2005, The Guardian

- «Cracking the Code», June 19, 2005, CNN

- Mission Impossible: The Code Even the CIA Can’t Crack

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kryptos.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Kryptos.

- Jim Sanborn’s official Kryptos webpage by Jim Sanborn

- Kryptos website maintained by Elonka Dunin (includes Kryptos FAQ, transcript, pictures and links)

- Kryptos photos by Jim Gillogly

- Washington Post: Cracking the Code of a CIA Sculpture

- Wired : Documents Reveal How the NSA Cracked the Kryptos Sculpture Years Before the CIA

- PBS : Segment (Video) on Kryptos from Nova ScienceNow

- The General Services Administration Kryptos webpage

- The General Services Administration Ex Nexum webpage

- The General Services Administration Indian Run webpage

- The General Services Administration Binary Systems webpage

- The Central Intelligence Agency Kryptos webpage

- The National Security Agency Kryptos webpage

- The Kryptos Project by Julie (Jew-Lee) Irena Lann

- Nicole (Monet) Friedrich’s Kryptos Observations

- Patrick Foster’s Kryptos page

- A practical introduction to brute-force decryption of Kryptos passages 1-3

- Top Definitions

- Synonyms

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

verb (used with object), hid, hid·den or hid, hid·ing.

to conceal from sight; prevent from being seen or discovered: Where did she hide her jewels?

to obstruct the view of; cover up: The sun was hidden by the clouds.

to conceal from knowledge or exposure; keep secret: to hide one’s feelings.

verb (used without object), hid, hid·den or hid, hid·ing.

to conceal oneself; lie concealed: He hid in the closet.

noun

British. a place of concealment for hunting or observing wildlife; hunting blind.

Verb Phrases

hide out, to go into or remain in hiding: After breaking out of jail, he hid out in a deserted farmhouse.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of hide

1

First recorded before 900; Middle English hiden, Old English hȳdan; cognate with Old Frisian hūda; akin to Greek keúthein “to hide”; see also hide2

synonym study for hide

1. Hide, conceal, secrete mean to put out of sight or in a secret place. Hide is the general word: to hide one’s money or purpose; A dog hides a bone. Conceal, somewhat more formal, is to cover from sight: A rock concealed them from view. Secrete means to put away carefully, in order to keep secret: The spy secreted the important papers.

OTHER WORDS FROM hide

hid·a·ble, adjectivehid·a·bil·i·ty, nounhider, noun

Words nearby hide

hidden agenda, hidden hand, hiddenite, hidden tax, hidden unemployment, hide, Hide-A-Bed, hide-and-seek, hideaway, hideaway bed, hidebound

Other definitions for hide (2 of 3)

noun

the pelt or skin of one of the larger animals (cow, horse, buffalo, etc.), raw or dressed.

Informal.

- the skin of a human being: Get out of here or I’ll tan your hide!

- safety or welfare: He’s only worried about his own hide.

verb (used with object), hid·ed, hid·ing.

Informal. to administer a beating to; thrash.

to protect (a rope, as a boltrope of a sail) with a covering of leather.

Origin of hide

2

First recorded before 900; Middle English; Old English hȳd; cognate with Dutch huid, Old Norse hūth, Danish, Swedish hud, Old High German hūt (German Haut ); akin to Latin cutis “skin,” Greek kýtos “hollow, container”; see also cutis, hide1

synonym study for hide

OTHER WORDS FROM hide

hideless, adjective

Other definitions for hide (3 of 3)

noun Old English Law.

a unit of land measurement varying from 60 to 120 acres (24 to 49 hectares) or more, depending upon local usage.

Origin of hide

3

First recorded before 900; Middle English hide, Old English hīd(e), hīg(i)d “portion of land, family,” from Germanic hīwidō; akin to Latin cīvis “citizen,” Greek keîsthai “to lie down, rest, remain, abide”

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to hide

bury, camouflage, cover, disguise, hole up, mask, obscure, plant, protect, shelter, shield, smuggle, stash, suppress, tuck away, withhold, adumbrate, cache, cloak, curtain

How to use hide in a sentence

-

Those applied to deer hide displayed much in common with the business end of the ancient stone tool, including a wavy surface and clusters of shallow grooves.

-

The last reported sighting was in 1953, and blue tigers were soon the stuff of legends, with not so much as a preserved hide to prove they ever existed.

-

The hide is roughly twice the thickness of most leather gloves, providing top-notch protection for whatever type of task you want to do.

-

Other stone tools and a pigment chunk buried with her likely were used to cut apart game and prepare hides.

-

Dixon says they already had bored their way through the tough alligator hide.

-

He does not hesitate to hide some Marxist books from her library because she fears that the military could use them against her.

-

Don’t hide behind meaningless rhetoric or claim you’re ready for action only to back off when the NRA comes knocking.

-

And he scarcely bothered to hide his chief ambition: to lead his country as prime minister.

-

They carefully scanned open windows along the route, looking for places where a shooter might hide.

-

You can hide your extreme views and duck from having to answer questions about them.

-

Poor Squinty ran and tried to hide under the straw, for he knew the boy was talking about him.

-

Instinctively he tried to hide both pain and anger—it could only increase this distance that was already there.

-

Consult not with him that layeth a snare for thee, and hide thy counsel from them that envy thee.

-

As Isabel walked carefully down the slippery stair she veiled her eyes to hide the wonder in them.

-

Even the stern, inflexible commander turned to hide an emotion he would have blushed to betray.

British Dictionary definitions for hide (1 of 3)

verb hides, hiding, hid (hɪd), hidden (ˈhɪdən) or hid

to put or keep (oneself or an object) in a secret place; conceal (oneself or an object) from view or discoveryto hide a pencil; to hide from the police

(tr) to conceal or obscurethe clouds hid the sun

(tr) to keep secret

(tr) to turn (one’s head, eyes, etc) away

noun

British a place of concealment, usually disguised to appear as part of the natural environment, used by hunters, birdwatchers, etcUS and Canadian equivalent: blind

Derived forms of hide

hidable, adjectivehider, noun

Word Origin for hide

Old English hӯdan; related to Old Frisian hēda, Middle Low German hüden, Greek keuthein

British Dictionary definitions for hide (2 of 3)

noun

the skin of an animal, esp the tough thick skin of a large mammal, either tanned or raw

informal the human skin

Australian and NZ informal impudence

verb hides, hiding or hided

Derived forms of hide

hideless, adjective

Word Origin for hide

Old English hӯd; related to Old Norse hūth, Old Frisian hēd, Old High German hūt, Latin cutis skin, Greek kutos; see cuticle

British Dictionary definitions for hide (3 of 3)

noun

an obsolete Brit unit of land measure, varying in magnitude from about 60 to 120 acres

Word Origin for hide

Old English hīgid; related to hīw family, household, Latin cīvis citizen

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Other Idioms and Phrases with hide

In addition to the idioms beginning with hide

- hide and seek

- hide nor hair, neither

- hide one’s face

- hide one’s head in the sand

- hide one’s light under a bushel

- hide out

also see:

- cover one’s ass (hide)

- tan one’s hide

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

1 year(s) ago

A negative form19 A professor was lecturing his class one day. He wanted to focus on negation one __________ time. MUCH20 “The ____________ example is English”, he said, “In English a double negative forms a positive. In some languages, though, such as Russian, a double negative is still a negative. ONE21 However, there ____________ a language wherein a double positive can form a negative. ”A loud voice from the back piped up, ‘Yeah, right. ‘ NOT BEA boot on the wrong foot22 Willy asked his teacher to help him get his shoes on at the end of a busy day. After quite a struggle, Tessa finally got them on. “They’re on the wrong ____________, Miss,” mumbled Willy. Staying calm she swapped them over for him. FOOT23 “They’re not my shoes, Miss,” Willy murmurs again. Tessa ____________ hard to keep her cool and asked Willy why he hadn’t told her before. FIGHT24 She then kneeled down again and helped him pull the shoes off. “These aren’t my shoes, they’re my brother’s and Mum told ______________ not to tell anyone. ” I25 Tessa helped him back into his shoes, got him into his coat, wrapped his scarf round his neck. When he ____________, she asked, “Where are your gloves, Willy?” “Oh, Miss, I always put them in my shoes ” DRESS26 The first form of cryptography was actually the simple writing of a message. Do you know why? Because most people were ____________ to read or write. ABLE27 In fact, the very word cryptography comes from the Greek words ‘kryptos’, which mean ‘hidden’, and ‘graphein’, which means ‘writing’. Cryptography, by its very nature, implies secrecy and ____________. DIRECTNESS28 Early cryptography included transforming messages into unreadable figures to protect the content of a message while it was carried from one ____________ to another. ADDRESS29 Nowadays, cryptography has evolved ____________ and today it includes such things as digital signatures, authentification of a sender or receiver and many more. GREAT30 People wanted to conceal messages since they moved out of caves and started living in groups. The earliest forms of cryptography were found in the cradle of ____________, Egypt, Greece and Rome. CIVILIZE31 The Greeks, for example, wrapped a tape around a stick, and then wrote the message on the wound tape. Unwinding the tape made the writing ____________. The receiver of the message had a stick of the same diameter and used it to decipher the message. MEANING

ответы: 1

Зарегистрируйтесь, чтобы добавить ответ

Ответ:

19. More

20. First

21. Is

22. Feet

23. Fought

24. Me

25. Was dressed

26. Not able/unable

27. Directness

28. Addressee/receiver

29. Greatly/a lot

30. Civilisation

31. Meaningful

Oct 31, 2021

Чтобы ответить необходимо зарегистрироваться.

For thousands of years, cryptography has been used for secret communications. The ciphertext or codes are a confidential way of writing any sensitive information. During the World Wars, these types of code were widely used for transmitting crucial information over long distances.

But the development of cryptography has been paralleled by the advancement of cryptanalysis – the “breaking” of codes. It’s more like a ball game between these two: sometimes the code breakers get the upper hand, sometimes they didn’t.

We are listing some of those mysterious and famous Uncracked texts and code that are still under scrutiny.

11. The Somerton Man (Tamam Shud)

The case of Somerton Man was an unsolved mystery of an unidentified man found dead on Somerton beach in Glenelg, South Australia on 1st December 1948. From the dead body, police recovered a piece of paper with the words ‘Tamam shud’ a Persian phrase for “ended” printed on it. Later, it was recognized that the piece was torn from a copy of ‘Rubaiyat’ of Omar Khayyam.

Upon retrieval of the copy, intensive studies were done on a series of mysterious letters founded on the final pages of the book, but nothing seemed to help. In fact, the International authorities like F.B.I and Scotland Yard were unable to figure out anything meaningful. So far, this case has been considered “one of Australia’s most profound mysteries”.

10. Zodiac Killer’s Code

The ‘Zodiac’ was a mysterious serial killer who terrorized Northern California between the late 1960s and 1970s. There are nearly 37 killings on his name mostly in San Francisco Bay, the cities of Benicia and Vallejo.

He shot two high school students on December 20, 1968. A year later, the local newspapers received an anonymous letter from the killer in which he took full credit for the murders. The letter contained a 408-symbol cryptogram in which the killer hid his identity.

The publishers received another letter after a few months, but this time he addressed himself as the Zodiac. He then sent two more cryptograms, one of which was never decoded. It was never traced and there is no personal information about him, except the name Zodiac. The Zodiac murder case is still open in the California High Court (since 1969).

9. D’agapeyeff Cipher

Alexander D’Agapeyeff was a Russian born English cryptographer who is famous for his still unsolved D’agapeyeff cipher. In 1939, he published the first edition of his book: Codes and Ciphers, an elementary book on cryptography.

At the end of the book, he mentioned a “challenge cipher” for readers. The code is still not decoded but upon asking D’Agapeyeff for a possible method for solving the riddle, he answered he has forgotten how to solve it.

Cryptographers and scientists believe that the code can never be solved as it contains numerous mistakes. Alexander was regarded by many as the most talented cryptographer majorly because his cipher remained unsolved for more than 70 years.

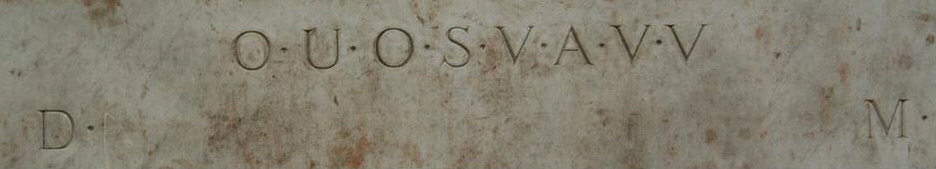

8. Shugborough Inscription

The Shugborough inscription is regarded as one of the world’s top uncracked ciphertexts. It is a series of letters – O U O S V A V V between the letters D and M, engraved on an 18th-century monument in the ground of Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, England.

What did fascinate historians and cryptographers is that the inscription is engraved just below the mirror image of Nicolas Poussin’s famous painting: The Shepherds Arcadia.

In 1982, the authors of the ‘The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail’ suggested that Poussin was a member of the Priory of Sion, and his panting and engravings contain hidden message(s) of great significance. There are many other theories related to his cipher but without any proof.

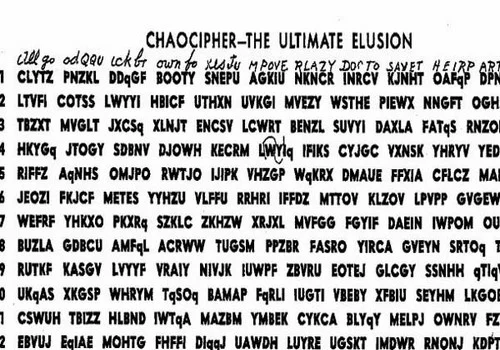

7. Chaocipher

Cryptographer John F. Byrne came up with the Chaocipher in 1918. According to him, Chaocipher was simple yet unbreakable. Bryne was so confident that he offered cash rewards to anyone who could solve it.

The Chaocipher was created using two simple rotating disks and was small enough to fit into a cigar packet. In May 2010 the Byrne family donated the Chaocipher-related papers to the National Cryptologic Museum in Ft. Meade, Maryland, USA.

6. The Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich manuscript is a handwritten book in an unknown script. It is named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish book dealer who bought it in 1912. The manuscript has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century around 1404-1438 and may have been originated from Northern Italy.

The book has around 240 pages filled with illustrations and diagrams. Over the decades, many top code-breakers and cryptographers have tried to solve it but they never got succeeded, though they have made some remarkable discoveries.

More to read: Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

5. Dorabella Cipher

Photo credit: Wikimedia

The Dorabella Cipher is an enciphered letter written by a British music composer, Edward Elgar to his friend Dora Penny. The cipher consists of 87 characters spread over three lines and they look like numeric semicircles written in one of the 8 directions.

Written in 1987, the letter has never been solved. In 2007, the Elgar Society organized a Dorabella competition and offered a big prize to the person who solves it. Many entries were received and some were very impressive but none was found satisfactory.

4. Linear A

Linear A and Linear B are names given to the two scripts used in Ancient Greek civilization. Sir Arthur Evans was among the first archaeologists to discover both sets of writings in various excavations.

In the 1950s, Linear B was widely deciphered mostly by Michael Ventris, an English linguist, and architect. Building upon Linear B, language scientists and cryptographers are still trying to understand its much more complex predecessor Linear A.

Linear A has hundreds of signs. They are understood to represent syllabic, ideographic, and semantic values in a similar manner to Linear B. While a considerable amount of those syllabic signs are similar to ones in Linear B, approximately 80% of Linear A characters are unique.

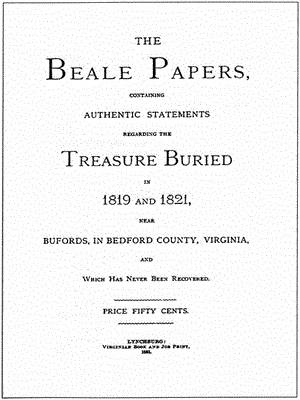

3. The Beale Cipher

The Beale cipher originates from an 1885 pamphlet announcing a secret treasure buried by a person named Thomas J. Bealle in a location near Bedford County, Virginia. The cipher is divided into three parts, one of which allegedly contains the location of a buried treasure of gold, silver, and jewels worth over $64 million. Out of these three, only one has been successfully solved while the other two remain a mystery.

Some experts consider Beale ciphers as an elaborate hoax. Some articles written in the 1980s reveal that there is a strong possibility that these ciphers may not have been written in the 19th century. Also, historical records of the city of Virginia cast serious doubts upon the existence of Thomas J. Beale.

2. The Phaistos Disc

The Phaistos Disc is just another jewel of ancient Greek civilization. In 1908, an Italian archaeologist Luigi Pernier discovered a disc of about 15 cm in diameter, consisting of stamped symbols from Phaistos on the island of Crete, Italy.

The Phaistos disc consists of 45 distinct signs, which were more likely to be made by pressing “seals” into a disc of soft clay in a clockwise sequence spiraling towards the center of the disk. After years of studies, archaeologists, historians, and cryptologists have come to the conclusion that the writings cannot be deciphered until more references are found in this context.

1. Kryptos

Recommended: 10 Unsolved Scientific Mysteries | Unlocked Answers

Kryptos is an encrypted sculpture located just outside the headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) at Langley, Virginia. Since its inauguration on November 3rd, 1990, there have been many speculations about the message it carries.

The name kryptos comes from the ancient Greek word for “hidden”. The sculpture consists of 869 characters, of which 865 are letters and 4 are question marks. It is divided into four parts, one of which is still un-deciphered and it’s also famous as one of the popular unsolved codes in the world.