Times and dates are usually confusing to learners. In this article, we’ll show you the most accurate way to express times and dates right in French.

Express Dates in French

If you are American and have written out dates using numbers, you have probably written something like this: 11/12/18 or 11/12/2018. In America this would refer to November 12, 2018, but in France this would refer to December 11, 2018. This is because in France, as in many European countries, the day is placed before the month, with the year following. Think of the units going from smallest to largest: day-month-year.

Express Times in French

Designating time in France is also approached slightly differently, as the French regularly use the 24-hour clock, often referred to as military time in the United States, since the 24-hour clock is used by branches of the military. In France, you may arrange to meet at 20 h for an 8 PM movie, for instance. To designate the day for this movie date, you could say vendredi, for instance, with a lower-case v. This is also something that differs from how days are designated in other languages, such as English, which uses capital letters for days and months of the year.

A Few Tips for Time and Date Expression

Here are some important things to keep in mind when referring to times and dates in French:

Time expressions in French include “Il est” for pointing out the hour, as with “Il est neuf heures” and “à” for designating a time during which something occurs, e.g., “Le film commence à 19 h 30”, “On est allé à la bibliothèque à 15 h.” You can also use “vers” to express an approximate time: “On y est allé vers 15 h.” The h, designating “heures” (or “heure”, in the case of 1 o’clock) is used as a separator, although you might see a colon at times [ : ].

For telling time, you may use both the 24-hour and 12-hour clocks. It is useful to adjust to the use of the 24-hour clock, known as “l’heure officielle” in France, since this is commonly used by the French, and comes up quite a lot in conversation. It also avoids confusion, since a 10 AM flight and a 10 PM flight are quite different. I remember booking a flight in New York, confusing my AM’s and PM’s, and mistaking one for the other. Luckily, I checked over my flight information before taking off for the airport. This must be why my phone is set to the 24-hour clock.

When the French are using the 12-hour clock, they might add a “matin” or “soir” to emphasize the time of day. “On se voit à sept heures ce soir ?” “Ce bruit m’a réveillée à six heures du matin !” (That’s me, talking about all those awful disruptive sounds, including beeping trucks, car alarms, phones going off, dogs barking for 20 minutes on end, children screaming and crying … I think I’m entering muddy waters.)

Also, you can designate a half hour by saying “dix heures et demie” (remember the agreement with the feminine word for hour that the half-hour takes on; this is distinct from “une demi-heure”, in which the “demi” in the hyphenated compound word is invariable). Think of the Marguerite Duras novel Dix heures et demie du soir en été, published in 1960, in which this hour is described vividly during a family vacation in Spain: “C’est encore une fois les vacances. Encore une fois les routes d’été. Encore une fois des églises à visiter. Encore une fois dix heures et demie du soir en été. Des Goya à voir. Des orages. Des nuits sans sommeil. Et la chaleur.”

In addition to half hours, you can designate quarters of an hour by saying “et quart” and “moins le quart” – remember the use of the definite article when you are talking about something that occurs fifteen minutes before the hour. Thus we have “dix heures et quart”, but “dix heures moins le quart”. These designations are specifically for the 12-hour clock. For the 24-hour clock, l’heure officielle, stick with adding numbers to the hour, as with vingt heures trente, quatorze heures quarante-cinq, etc. We can also say zéro heures for minuit.

For what is designated as 12 h with the 12-hour clock, we have the words midi and minuit, depending on whether the clock strikes this hour during the day or at night.

Calendar days follow the Gregorian calendar that is used worldwide. Remember that the words that are used for days and months of the year in French are never capitalized unless they appear at the beginning of a sentence.

Learn How to Say Monday to Sunday in French

The French week begins with Monday, following the International Standard. Here are the days of the week, along with their three-letter codes (which are used on things like packaging, to show expiration dates, among other things):

Days are masculine. Thus, if your flute lesson occurs on Thursday, you would say “J’ai ma leçon de flûte le jeudi.” The definite article indicates a regularly occurring event. To indicate a specific day, you may use “ce” or nothing at all to introduce the day, depending on the context, e.g., “On va au concert ce dimanche”, “La réunion aura lieu lundi”. The “ce” in the first phrase emphasizes that the concert is this coming Sunday. In the second phrase, it is implied that the Monday you are referring to is approaching imminently.

Learn How to Say the Months of the Year in French

The months of the year are as follows, along with their corresponding three-letter codes:

Months are also masculine. In many cases, you would not need an article to introduce them, but it is important to know the gender for when you have to modify them, as with “Ces négociations se tiendra à Paris ce décembre prochain”. You can introduce months with “en” or “au mois de”: “Je pars en vacances au mois de mai”, “Je passerai l’examen en juin”. For events with specific times and dates, such as exams, you could write the following: L’examen aura lieu le vendredi 2 novembre 2018, de 15 h à 17 h.

If you do, in fact, have an exam approaching, good luck with it and perhaps treat yourself to a movie afterward at 20 h.

🇫🇷 Get More Resources to Learn How to Say Complete Sentences in French

If you are looking for more resources to improve your French speaking and listening skills, try Glossika. Glossika is a team of linguists and polyglots dedicated to changing the way people learn foreign languages to fluency through a natural immersion self-training method.

By training with Glossika, you’ll know how to construct complete sentences in French, you’ll know the accurate French word order, you’ll absorb French grammar rules and expand French vocabulary. All without memorization.

Sign up on Glossika now to get 1000 reps of audio training for completely free. No commitment and no credit card required:

You May Also Like:

- The Most Common Mistakes Learners Make When Learning French

- Differences Between Spoken French and Written French

- Quick Guide to Remembering How to Use French Accent Marks

- Download Guide to French Pronunciation & Grammar (free)

- Download Glossika Beginner’s Guide to French Grammar and Word Order (free)

Subscribe to The Glossika Blog

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox

Lesson focus

Outro

Whether you’re traveling to France or learning the French language, being able to tell time is important. From asking what time it is to the key vocabulary you need for speaking in French about hours, minutes, and days, this lesson will guide you through everything you need to know.

French Vocabulary for Telling Time

To begin with, there are a few key French vocabulary words related to time that you should know. These are the basics and will help you throughout the rest of this lesson.

| time | l’heure |

| noon | midi |

| midnight | minuit |

| and a quarter | et quart |

| quarter to | moins le quart |

| and a half | et demie |

| in the morning | du matin |

| in the afternoon | de l’après-midi |

| in the evening | du soir |

The Rules for Telling Time in French

Telling time in French is just a matter of knowing the French numbers and a few formulas and rules. It’s different than we use in English, so here are the basics:

- The French word for «time,» as in, «What time is it?» is l’heure, not le temps. The latter means «time» as in «I spent a lot of time there.»

- In English, we often leave out «o’clock» and it’s perfectly fine to say «It’s seven.» or «I’m leaving at three-thirty.» This is not so in French. You always have to say heure, except when saying midi (noon) and minuit (midnight).

- In French, the hour and minute are separated by h (for heure, as in 2h00) where in English we use a colon (: as in 2:00).

- French doesn’t have words for «a.m.» and «p.m.» You can use du matin for a.m., de l’après-midi from noon until about 6 p.m., and du soir from 6 p.m. until midnight. However, time is usually expressed on a 24-hour clock. That means that 3 p.m. is normally expressed as quinze heures (15 hours) or 15h00, but you can also say trois heures de l’après-midi (three hours after noon).

What Time Is It? (Quelle heure est-il?)

When you ask what time it is, you will receive an answer similar to this. Keep in mind that there are a few different ways to express different times within the hour, so it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with all of these. You can even practice this throughout your day and speak the time in French whenever you look at a clock.

| It’s one o’clock | Il est une heure | 1h00 |

| It’s two o’clock | Il est deux heures | 2h00 |

| It’s 3:30 | Il est trois heures et demie Il est trois heures trente |

3h30 |

| It’s 4:15 | Il est quatre heures et quart Il est quatre heures quinze |

4h15 |

| It’s 4:45 | Il est cinq heures moins le quart Il est cinq heures moins quinze Il est quatre heures quarante-cinq |

4h45 |

| It’s 5:10 | Il est cinq heures dix | 5h10 |

| It’s 6:50 | Il est sept heures moins dix Il est six heures cinquante |

6h50 |

| It’s 7 a.m. | Il est sept heures du matin | 7h00 |

| It’s 3 p.m. | Il est trois heures de l’après-midi Il est quinze heures |

15h00 |

| It’s noon | Il est midi | 12h00 |

| It’s midnight | Il est minuit | 0h00 |

Asking the Time in French

Conversations regarding what time it is will use questions and answers similar to these. If you’re traveling in a French-speaking country, you’ll find these very useful as you try to maintain your itinerary.

| What time is it? | Quelle heure est-il ? |

| Do you have the time, please? | Est-ce que vous avez l’heure, s’il vous plaît ? |

| What time is the concert? The concert is at eight o’clock in the evening. |

À quelle heure est le concert ? Le concert est à huit heures du soir. |

Periods of Time in French

Now that we have the basics of telling time covered, expand your French vocabulary by studying the words for periods of time. From seconds to millennium, this shortlist of words covers the entire expanse of time.

| a second | une seconde |

| a minute | une minute |

| an hour | une heure |

| a day / a whole day | un jour, une journée |

| a week | une semaine |

| a month | un mois |

| a year / a whole year | un an, une année |

| a decade | une décennie |

| a century | un siècle |

| a millennium | un millénaire |

Points in Time in French

Each day has various points in time that you might need to describe in French. For instance, you might want to talk about a beautiful sunset or let someone know what you’re doing at night. Commit these words to memory and you’ll have no problem doing just that.

| sunrise | le lever de soleil |

| dawn | l’aube (f) |

| morning | le matin |

| afternoon | l’après-midi |

| noon | midi |

| evening | le soir |

| dusk | le crépuscule, entre chien et loup |

| sunset | le coucher de soleil |

| night | la nuit |

| midnight | le minuit |

Temporal Prepositions

As you begin to formulate sentences with your new French time vocabulary, you will find it useful to know these temporal prepositions. These short words are used to further define when something is taking place.

| since | depuis |

| during | pendant |

| at | à |

| in | en |

| in | dans |

| for | pour |

Relative Time in French

Time is relative to other points in time. For instance, there is always a yesterday which is followed by today and tomorrow, so you’ll find this vocabulary a great addition to your ability to explain relationships in time.

| yesterday | hier |

| today | aujourd’hui |

| now | maintenant |

| tomorrow | demain |

| the day before yesterday | avant-hier |

| the day after tomorrow | l’après-demain |

| the day before, the eve of | la veille de |

| the day after, the next day | le lendemain |

| last week | la semaine passée/dernière |

| the final week | la dernière semaine (Notice how dernier is in a different position in «last week» and «the final week.» That subtle change has a significant impact on the meaning.) |

| next week | la semaine prochaine |

| days of the week | les jours de la semaine |

| months of the year | les mois de l’année |

| the calendar | le calendrier |

| the four seasons | les quatre saisons |

| winter came early / late spring came early / late summer came early / late autumn came early / late |

l’hiver fut précoce / tardif le printemps fut précoce / tardif l’ete fut précoce / tardif l’automne fut précoce / tardif |

| last winter last spring last summer last autumn |

l’hiver dernier le printemps dernier l’ete dernier l’automne dernier |

| next winter next spring next summer next autumn |

l’hiver prochain le printemps prochain l’ete prochain l’automne prochain |

| a little while ago, in a little while | tout à l’heure |

| right away | tout de suite |

| within a week | d’ici une semaine |

| for, since | depuis |

| ago (depuis versus il y a) | il y a |

| on time | à l’heure |

| in time | à temps |

| at that time | à l’époque |

| early | en avance |

| late | en retard |

Temporal Adverbs

As you become even more fluent in French, consider adding a few temporal adverbs to your vocabulary. Once again, they can be used to further define when something is taking place.

| currently | actuellement |

| then | alors |

| after | après |

| today | aujourd’hui |

| previously, beforehand | auparavant |

| before | avant |

| soon | bientôt |

| meanwhile | cependant |

| afterwards, meanwhile | ensuite |

| for a long time | longtemps |

| now | maintenant |

| anytime | n’importe quand |

| then | puis |

| recently | récemment |

| late | tard |

| all of a sudden, suddenly | tout à coup |

| in a little while, a little while ago | tout à l’heure |

Frequency in French

There will also be times when you need to speak about the frequency of an event. Whether it only happens once or reoccurs on a weekly or monthly basis, this short vocabulary list will help you achieve that.

| once | une fois |

| once a week | une fois par semaine |

| daily | quotidien |

| every day | tous les jours |

| every other day | tous les deux jours |

| weekly | hebdomadaire |

| every week | toutes les semaines |

| monthly | mensuel |

| yearly | annuel |

Adverbs of Frequency

Adverbs that relate to frequency are just as important and you’ll find yourself using this quite often as your French studies progress.

| again | encore |

| one more time | encore une fois |

| never, ever | jamais |

| sometimes | parfois |

| sometimes | quelquefois |

| rarely | rarement |

| often | souvent |

| always | toujours |

Time Itself: Le Temps

Le temps refers broadly either to the weather or a duration of time, indeterminate or specific. Because it is such a basic concept that surrounds us every day, many French idiomatic expressions have evolved using temps. Here are a few common ones that you might need to know.

| a little while ago | il y a peu de temps |

| in a little while | dans un moment, dans quelque temps |

| at the same time | en même temps |

| at the same time as | au même temps que |

| cooking / preparation time | temps de cuisson / préparation cuisine |

| a part-time job | un temps partiel |

| a full-time job | un temps plein ou plein temps |

| to work part-time | être ou travailler à temps partiel |

| to work full-time | être ou travailler à plein temps ou à temps plein |

| to work full-time | travailler à temps complet |

| to work 30 hours per week | faire un trois quarts (de) temps |

| time to think | le temps de la réflexion |

| to reduce working hours | diminuer le temps de travail |

| to have some spare time / free time | avoir du temps libre |

| in one’s spare time, in a spare moment | à temps perdu |

| in times past, in the old days | au temps jadis |

| with the passing of time | avec le temps |

| all the time, always | tout le temps |

| in music, a strong beat / figuratively, a high point or a highlight | temps fort |

| in sports, a time-out / figuratively, a lull or a slack period | temps mort |

Speaking French is more than just learning vocabulary words from flash cards. Words are just atoms, the building blocks of a language. They have to be put into context and strung together to form a sentence that is imparted with meaning.

Your French classes will teach you a lot about how to conjugate a verb, have your nouns and adjectives agree and what words and phrases will help you find the bathroom. What they might not teach you (but should) is sentence structure.

How are sentences put together in French? Does one use the dative, nominative, accusative and interrogative cases the same way as in English?

Setting aside that pesky grammatical gender agreement required to speak French properly, where and how do adjectives and adverbial phrases fit in a properly constructed sentence?

As an overview of these topics, Superprof presents this chart, one that you might consider printing and clipping and carrying with you to your French lessons or your French tutoring sessions.

| Type of Sentence | Form | Sample | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Declarative | S+V+O | La professeur aime ses éleves. | The teacher loves her students. |

| Negation | S+’ne’+V+’pas’+O | Je ne veux pas aller au cinéma. | I don’t want to go to the cinema. |

| Interrogative sentences | 1. Preface sentence with ‘est-ce-que’ 2. Reverse: V+S+O (formal) |

Est-ce-que tu as fait tes devoirs? Pourrez-vous me dire ou est la bibliothèque? |

Have you done your homework? Could you tell me where the library is? |

| Imperative sentence | V+O | Ouvre(z) la porte! | Open the door! |

| Simple declarative with adjective | S+V+Adj (adj must ‘agree’ with subject!) |

La fille est belle. Le chien est beau. |

The girl is pretty. The dog is pretty. |

| Adverbial pronoun | S+’y’+V | On y va! | Let’s go! |

| Relative clauses | ‘que’ for objects ‘qui’ for people |

Le livre que tu m’as donné… L’homme qui chante… |

The book you gave me… The man who is singing… |

Now, let’s examine each of these constructions in-depth…

But before you dive in, we’ve added a French playlist to enhance your reading experience while learning about French sentence structure. The playlist features a variety of French music, ranging from classic chansons to modern pop hits. Whether you’re a beginner or an advanced French learner, immersing yourself in the language through music can be a great way to improve your listening skills and vocabulary. So sit back, relax, and let the music transport you to the streets of Paris as you dive into the fascinating world of the French language.

The best French tutors available

5 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (30 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (30 reviews)

1st lesson free!

Let’s go

French Sentence Structure: Understanding the Basics

French is a beautiful language, but it can be challenging to master its sentence structure, especially if you are a beginner. However, understanding the rules for forming proper sentences is essential for effective communication in French. In this article, we’ll explore the basics of French sentence structure and provide some useful tips to help you improve your French language skills.

Basic French Sentences and Word Order

In French, as in English, a sentence consists of a subject, verb, and object. The basic word order in French sentences is subject-verb-object (SVO). For example, «Je mange une pomme» means «I am eating an apple.» The subject «je» (I) comes first, followed by the verb «mange» (am eating), and then the object «une pomme» (an apple).

French Sentence Starters and Construction

To construct sentences in French, it’s essential to have a good grasp of sentence starters and construction. Some common sentence starters in French include «Je suis» (I am), «Il y a» (There is), «C’est» (It is), and «Il faut» (It’s necessary).

When constructing sentences, it’s important to pay attention to gender and number agreement. For example, if you want to say «I like the cat,» you would say «J’aime le chat» (not «J’aime la chat»). Similarly, if you want to say «I like the cats,» you would say «J’aime les chats» (not «J’aime le chats»).

French Time Phrases and Directional Words

Time phrases and directional words are also essential components of French sentence structure. Some common time phrases in French include «aujourd’hui» (today), «demain» (tomorrow), and «hier» (yesterday). Directional words such as «à droite» (to the right) and «à gauche» (to the left) are also important for giving directions.

Other Important French Sentence Structure Elements

French also has several conjunctions that are important for linking ideas and constructing more complex sentences. Some common French conjunctions include «et» (and), «mais» (but), and «ou» (or).

Si clauses are another important element of French sentence structure. These clauses are used to express hypothetical situations and typically begin with «si» (if). For example, «Si j’avais de l’argent, j’achèterais une voiture» means «If I had money, I would buy a car.»

With french sentence structure, remember to pay attention to gender and number agreement, use common sentence starters, and include directional words and time phrases to enhance your French language skills. In addition, understanding the grammar rules of French sentence structure is essential for effective communication in the language.

The Simple Declarative Sentence

The most common type of sentence in English and in French is the declarative sentence; a simple expression stating a fact:

Il fait beau.

It (the weather) is nice.

Catherine est une adolescente.

Catherine is a teenager.

Ma mère est danseuse.

My mother is a dancer.

Il écoute la musique.

He listens to music.

As in English, the declarative form in French is the core around which more complicated sentences can be built.

Basic French sentences with nouns

When you learn a language, you start with basic sentences with the most common word order.

In French, this is SVO — Subject + Verb + Object. As for most Romance languages — and, indeed, English — the subject (who is doing the action?) generally comes at the beginning of the sentence.

There follows the verb, and then the direct object (what is he/she doing?). The sentences above are all examples of the SVO construct.

We now expand on that basic sentence structure by adding an indirect object (for/to/with whom is he doing it?):

Subject + Verb + Direct Object + Indirect Object

Marie donne le livre à sa mère.

Marie gives the book to her mother

Jean rend le cartable à son frère.

Jean gives his brother his rucksack back.

Suzanne apporte les pommes à la cuisine.

Suzanne brings the apples to the kitchen.

Lucy rend les livres à la bibliothèque.

Lucy returns the books to the library.

Je prête mon vélo à mon ami.

I lend my bike to my friend.

Marie donne le livre à sa mère.

Marie gives the book to her mother.

Nous offrons des fleurs à notre mère.

We offer flowers to our mother.

Vous envoyez une lettre à votre grand-mère.

You send a letter to your grandmother.

In each of these examples, the subject is doing something with the direct object for, to or with the indirect object.

Until now, we’ve only shown simple sentences using action verbs: somebody or something doing something. What about sentences that use a compound verb?

In French as in English,

compound verbs consist of an auxiliary verb and a participle verb form,

either in the past or present tense.

In English, these ‘helper’ verbs are to be, to have and to do. In French, only the first two, être and avoir, are used in compound structures with being être used less frequently.

Nevertheless, the structure remains the same: the verb that indicates what is happening stays in second place:

Le roi avait pardonné le mousquetaire.

The king had pardoned the musketeer.

J’ai fini la vaisselle.

I have finished the dishes.

Les parents ont gaté ces enfants!

The parents have spoiled these children!

Le proffeseur avait donné des devoirs.

The teacher had given homework.

Mon copain est arrivé hier soir.

My mate arrived yesterday evening.

The only time a direct object might come after an indirect object is if there is additional information attached to it, such as a relative clause:

Jean rend à son frère le cartable qu’il lui avait prêté.

Jean gives his brother back the rucksack he had lent him.

Ma soeur montre à ma mére les dessins que j’avais peint.

My sister shows my mother the drawings I painted.

Mon collegue dit à nôtre patron que je suis fainéante!

My colleague tells our boss that I am lazy!

Benoit lit à sa copine des pôemes qu’il trouve romantique.

Benoit reads to his girlfriend poems he finds romantic.

Gabriel donne à sa soeur les bonbons qu’il avait promi.

Gabriel gave to his sister the sweets he had promised.

Naturally, you could structure the sentence in such a way that the direct object comes before the indirect:

Gabriel a donné les bonbons qu’il avait promi a sa soeur.

Gabriel gave the sweets he had promised to his sister.

However, that makes the sentence meaning ambiguous: He promised the candies to his sister, but who exactly did he give them to?

French being an exceedingly precise language, it is always best to follow the proper sentence structure in order to convey your intended meaning.

It might take a bit of practice, but your language skills will be all the richer for it!

Word order with pronouns

As in many other languages, French words are put into a different order if some or all of them are pronouns.

Let’s take the sentence:

Marie montre son dessin à sa maman.

Marie shows her drawing to her mum.

Subject pronouns stay at the beginning of the sentence:

Elle montre son dessin à sa maman.

She shows her drawing to her mum.

Sometimes, in French, it is much more convenient to describe an object in a sentence by using a pronoun.

Consider the sentence above: She shows her drawing to her mum. How can that sentence be made less cumbersome?

| Elle lui montre son dessin. | ‘lui’ takes the place of ‘maman’ even though, generally, ‘lui’ represents a male. |

| Elle le montre à sa maman. | ‘le’ takes the place of the picture. In this sentence, the gender matches; dessin is masculine. |

| Elle le lui montre. | here, you have a combination of the two representations above, with ‘le’ meaning ‘dessin’ and ‘lui’ in for ‘maman’. |

Let us now suppose you are that dear mum, telling a jealous mother about how your daughter creates artwork for you. You would say:

Son dessin? Elle me le montre!

Her drawing? She shows it to me!

Because of its first-person singular designation, “me” ranks higher than “le” — a mere article. Therefore, you would place ‘me’ before ‘le’ in such sentences.

Object pronouns come BEFORE the verb but AFTER the subject. In what order they come depends on the pronoun:

Subject + ‘me’, ‘te’, ‘se’, ‘nous’, ‘vous’ + ‘le’, ‘la’, ‘les’ + ‘lui’, ‘leur’ + (adverbial pronoun “y”) + ‘en’ + Verb.

Examples:

Elle nous les montre. She shows them to us. Note that ‘montre’ agrees with ‘elle’ — third person singular.

You might also phrase it as a question:

Elle vous les montre? Does she show them to you? Either way, the order listed above remains.

‘En’ is an indefinite plural pronoun that, in this sentence’s case, represents the drawings. ‘en’ is always placed just before the verb:

Elle montre des dessins à sa maman. -> Elle lui en montre. She shows some drawings to her mum. > She shows her them.

Learn more about French grammar rules.

Negative Sentences

The French negative words are: ne…pas and ne…point (the latter is archaic or regional).

“Ne” comes immediately after the subject.

“Pas” comes immediately after the verb.

Marie ne montre pas son dessin à sa maman.

Marie does not show her drawing to her mum.

Marie ne le montre pas à sa maman.

Marie doesn’t show it to her mum.

Marie ne lui montre pas son dessin.

Marie doesn’t show her her drawing.

Marie ne le lui montre pas.

Marie doesn’t show her it.

Negation is pretty straightforward in French, however you should be aware of using ‘any’ properly.

The equivalent of the English “no” or “not…any” is “ne…aucun”:

Marie ne montre aucun dessin à sa mère. Marie doesn’t show any drawing to her mother.

Or: Marie shows no drawings to her mother.

The best French tutors available

5 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (30 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (27 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (26 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (30 reviews)

1st lesson free!

Let’s go

Adding Adjectives, Adverbial Phrases

Adverbs and adverbial phrases

The adverbial phrase or complément circonstanciel can come at the beginning, the end or the middle of the sentence. They are emphasised if they are put at the beginning or the end; it is more colloquial to only put single-word adverbs in the middle.

Such phrases may denote a time:

Marie lui montrera son dessin demain.

Marie will show him/her her drawing tomorrow.

strong>Demain, Marie lui montrera son dessin.

Tomorrow, Marie will show him/her her drawing.

Marie lui montrera demain son dessin.

Marie will show him/her tomorrow her drawing.

Or a place:

Marie lui montrera son dessin à l’école.

Marie will show her drawing at school.

À l’école, Marie lui montrera son dessin.

At school, Marie will show her drawing.

However, if you are using a complément circonstanciel construction to denote a place where an activity has happened, you cannot put that location in the middle of the sentence:

Marie lui montrera à l’école son dessin.

Marie will show him/her at school her drawing.

You’ll note that, as we do not know who the ‘lui’ in question is, it might represent a male or a female — hence both pronouns.

Adverbial pronouns

The adverbial pronoun “y” (directional) comes after most other pronouns but before the plural pronoun “en”. It is generally used to denote a progressive action, or one that is about to take place. However, ‘y’ can only be used if the listener knows what the speaker is talking about:

Marie va à l’école.

Marie goes to school.

If the listener knows where Marie is headed, the speaker could say: Marie y va — Marie is going.

Another example:

Nous irons au bois.

We go to the forest.

Contrast that with the much simpler: Nous y allons. We’re going — the usage is contingent on it being known where we are going!

Caution! You should never say:

Marie y va à l’école or Nous y allons au bois — it suggests the listener both knows and doesn’t know the destination.

Find French lessons that may interest you here.

Adjectives and their placement in the sentence.

Unlike in English, Adjectives are generally placed right after the noun:

Whereas an English speaker would say: ‘the red balloon’, in French, the proper order is: ‘le ballon rouge’. Here are some more examples:

- The hungry lion = le lion affamé.

- The sleepy child = l’enfant somnolent(e).

- The playful cat = le chat (la chatte) ludique.

- A good book = un bon livre.

Do you know of the BAGS group? It denotes constructions wherein the adjective comes before the noun:

- Beauty: Un joli ballon. A pretty balloon. More: Une jolie femme (a pretty woman), une belle chanson (a pretty song)

- Age: Un vieux ballon. An old balloon. More: Un viel homme (an old man), une vieille bicyclette (an old bicycle)

- Goodness: Un méchant ballon. A mean balloon. More: un bon vin (a good wine), une bonne amie (a good friend).

- Size: Un grand ballon. A big balloon. More: Un petit ballon (a small balloon), une petite fille (a small girl).

Adjectives used with verbs expressing a state come after the verb:

Le ballon est vert.

The balloon is green.

Le ballon semble petit.

The balloon seems small.

Le ballon deviendra grand.

The balloon will become big.

Note that adjectives should always agree with the noun they are qualifying in gender and number.

Le chat deviendra grand.

The (male) cat will become big.

La fille semble petite.

The girl seems small.

La voiture est verte.

The car is green.

Dependent and relative clauses

Most dependent or relative clauses come right after the main clause, at the end of the sentence.

Relative clauses

Relative clauses are introduced by the relative pronoun “que” if the noun is an object and «qui» if the noun is human.

These clauses are usually placed at the end of the sentence and come right after the noun they are qualifying — meaning that these nouns are sometimes moved from their usual place in the sentence.

An exception is if the qualifying noun is the subject, then the relative clause is moved forward. If it is very long it can be put between commas.

J’aime la chanson que tu chantes.

I like the song you are singing.

La chanson que tu chantes est belle.

The song you are singing is pretty.

Marie donne à Daniel le livre qu’elle a acheté.

Marie gives Daniel the book she bought.

Marie, qui aime la danse, donne le livre à Daniel.

Marie — who likes dancing — gives the book to Daniel.

Conjunctive clauses

Conjunctive phrases are clauses that are the object of a verb. The verb in question generally deals with thoughts and emotions and the expression of them. They are either infinitive clauses or are introduced with the conjunction “que”.

J’ai décidé de prendre le train.

I decided to take the train.

Elle aide William à apprendre le français.

She helps William learn French.

Il pense que je t’aime.

He thinks I love you.

Tu dis que tu veux mon amitié.

You say you want my friendship.

Check for French lessons for beginners here on Superprof.

The French Interrogative Sentence

French has several ways to build an interrogative. Here are some tips to improve your French dialogue:

Est-ce-que

Putting “est-ce-que” at the beginning of a sentence is the easiest way to formulate a question in French. You can use the usual word order following it.

Est-ce-que vous pouvez m’aider?

Can you help me?

Est-ce-que vous savez où se trouvent les toilettes?

Do you know where the toilets are?

Est-ce-que l’éléphant est le plus grand mammifère terrestre?

Is the elephant the biggest land-bound mammal?

Est-ce-que ce siège est pris?

Is this seat taken?

It is considered inelegant to preface your questions in this manner. During your French lessons, your teacher might insist you use reversal instead.

Reversing subject and predicate

The more elegant phrasing is to reverse the subject and predicate, putting the verb at the beginning of the sentence and hyphenating the subject-verb group:

Pouvez-vous m’aider?

Can you help me?

Savez-vous où se trouve les toilettes?

Do you know where the toilets are?

If the subject of the sentence is not the person you are addressing, it stays at the beginning of the sentence, and an additional subject “il” is added:

L’éléphant est-il le plus grand mammifère terrestre?

Is the elephant the largest land mammal?

Ce siège est-il pris?

Is this seat taken?

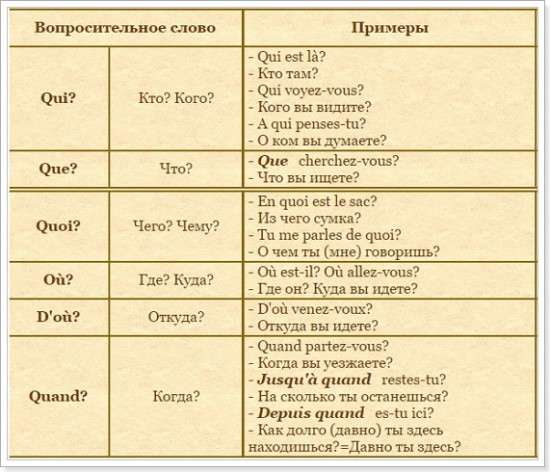

Question words

For questions that cannot be answered by yes or no, French uses question words. They come at the beginning of the sentence, and are followed by the inverted subject-verb group (also more idiomatically, they can also come at the end of a basic sentence).

Check for French conversation classes London here on Superprof.

Here is a list of French words for asking questions:

- Qui: who. Qui es-tu? Who are you?

- Que: what. Que fais-tu? What are you doing?

- Quoi: in rare cases, replaces “que”: Quoi faire?

- Où: where. Où vas-tu? Where are you going?

- Comment: how. Comment vas-tu? How are you?

- Pourquoi: why. Pourquoi manges-tu ces frites? Why are you eating those chips?

- Combien: how much. Combien coûte cette baguette? How much does this baguette cost?

- Quel/quelle/quels/quelles: which. Should agree with the noun it is qualifying: Quels cinémas jouent-ils le nouveau Star Wars? (Which cinema is showing the new Star Wars?) “Quel” can be combined with adverbial prepositions: Dans quel château Edmond Dantès était-il emprisonné? (In what castle was Edmond Dantès imprisoned?) Après quelle date peut-on manger des huîtres? (After what date can you eat oysters?)

Indirect questions

Indirect questions are questions that are related rather than asked. They are introduced by the usual question words:

Ils se demandent quels cinémas montrent le nouveau Star Wars. They are asking themselves which cinemas are showing the new Star Wars film.

Elle demande comment il va. She asks how he’s doing.

My Superprof tutor taught me the correct word order during our French lessons online!

The French Conditional Sentence

The language of Voltaire uses the pair of French words “si… alors” to express a condition over two clauses, though in some French phrases, “alors” is left off. It is considered more colloquial.

Si tu veux apprendre la langue, alors il faut bien apprendre ton vocabulaire français.

If you want to learn the language, so you will have to learn your French vocabulary.

“Si tu ne m’aimes pas je t’aime, et si je t’aime prends gare à toi!”

If you don’t love me, I love you; and if I love you: take care! (from the opera “Carmen”, by Bizet)

Check for French lessons for kids here on Superprof.

Don’t forget to do the grammar exercises in your French grammar textbooks and from your online French course to help you learn all about French sentence structure, learn French expressions and how to conjugate French verbs.

Find French classes Edinburgh on Superprof.

Key Takeaways

- French sentences typically follow a subject-verb-object (SVO) structure, but there are different sentence structures that can be used to convey meaning.

- Basic French sentences often include phrases like «where are you in French?» (où es-tu en français?), «to in French» (pour en français), and «of in French» (de en français), which are fundamental in basic sentence construction.

- French time phrases, such as «in the morning» (le matin) and «at night» (la nuit), are commonly used in French sentences and can be placed at the beginning or end of a sentence to convey meaning.

- Memorizing basic French verbs and the order of pronouns in a sentence is important to understand French sentence structure.

- Starting a sentence with a verb is a common structure in French, and can be used to emphasize the action or event taking place.

- It’s essential to study the language structure and form, as well as to memorize basic French phrases and sentence starters, like «on y va» (let’s go) and «vieux lion rouge» (old red lion) which translate to more familiar meanings.

- Finally, it’s important to master basic French grammar and sentence form in order to build more complex structures and effectively communicate in French.

By

Last updated:

December 14, 2022

Stand Tall! The Guide to Confidence with French Word Order

Is your French still in pieces?

Learning French can be like drawing up plans for a new building.

And what would a building be like without structure?

It probably would not be very safe.

It probably would not serve its intended function.

It probably would not make much sense.

It might not even be able to stand.

Language is the same way.

We can’t just throw words around and expect to be understood.

Even if we chose all the right words, we might very well just be sputtering nonsense if they are not in the right order.

And French has a lot of rules about word order.

It may seem tedious, but these rules, like the laws of physics, ensure that all the elements of your sentence are in the right place to remain standing.

In this post, we are going to go through the basic elements of French word order, so you can build a strong foundation for your French sentences.

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Structuring a Sentence: The Blueprint

We know there is a lot of information to cover when it comes to French word order, so we are going to start by taking a look at the “big picture,” or blueprint, of a French sentence. This will give you a basic idea of word order without overwhelming you with details and exceptions (that will come later!).

- Subject. Good news! As with English, the subject — for example, je (I), tu (you), il/elle/on (he/she/one or we), nous (we), vous (you) and ils/elles (they) — usually goes at the beginning of a sentence.

- Direct and indirect object pronouns, y and en. We will explain these words more in-depth later on, but for now just know that they are helpful because they keep you from having to repeat words/phrases that are understood in context.

- Verb. Next is the verb, or “action word,” like voyager (travel) or simply être (to be).

- Direct object. A direct object is something the verb acts on. For instance, in the sentence “J’ai lavé ma voiture” (I washed my car), voiture (car) is the direct object because it is what is being washed.

- Indirect object. An indirect object, as the name implies, is “indirectly” affected by the verb. In the sentence “J’ai parlé avec ma soeur” (I talked with my sister), the indirect object is mon soeur (my sister).

- Adjective. Sorry, here is a big point of difference between English and French! In French, adjectives normally go after the noun they modify (of course there are exceptions, which we will deal with later).

- Modifiers/additional details. Finally, any more details generally go at the end of the sentence.

So to sum up:

- Subject.

- Direct and indirect object pronouns, y and en.

- Verb.

- Direct object.

- Indirect object.

- Adjective.

- Modifiers/additional details.

Of course, not every sentence will include all of these components, but it gives you a good idea of what to expect.

For example, this sentence includes several of the above components:

Je vous ai envoyé un email important ce soir. (I sent you an important email this evening.)

Je (subject) vous (indirect object pronoun) ai envoyé (verb) un email (direct object) important (adjective) ce soir (additional detail).

Note that vous, while it technically functions as an indirect object as the person the email was written to, is considered a pronoun and is therefore placed before the verb (we will talk more about word order with direct and indirect object pronouns later).

This is because the word vous is itself a pronoun. That is, if we replaced vous with a name, such as “Paul,” it would act as an indirect object and go after the direct object, un email, like so:

J’ai envoyé un email important à Paul ce soir. (I sent an important email to Paul this evening.)

Below, we will go into more detail about different elements of sentences you need to understand in order to get all of your French in order. We have included links to resources to help introduce you to these concepts.

Getting Curious: Questions

If you are learning French, you probably have a lot of questions on your mind. And since conversation is based on a back-and-forth exchange of ideas, you need to be able to ask questions (for clarification, getting more information, changing the subject, etc.).

One of the simplest ways to form a question in French is by inversion. This means the subject and the verb switch places and are hyphenated.

For example, to make “Vous voulez du chocolat” (You want some chocolate) a question, vous (you) and voulez (want) switch places, so that we get:

Voulez-vous du chocolat ? (Do you want some chocolate?)

Inversion is not just for “yes-or-no” questions, though. You may employ a “question word” such as quel (what/which — add “le” for the feminine form and “-s” for the plural) at the beginning of the sentence.

So to ask someone their age, we would say:

Quel âge as-tu ? (Literally, “What age do you have?”)

Since quel calls for a noun, âge follows directly after and the inversion comes last.

Here are some more “question words” you might want to ask:

- Pourquoi (why)

- Comment (how)

- Qui (who)

- Quand (when)

- Oú (where)

- Combien (how many)

Quand allez-vous au musée ? (When are you going to the museum?)

Here, the inversion comes right after the “question word,” because it describes location and is not directly linked to quand.

If you are asking a basic yes-or-no question, you can simply place est-ce que (literally, “is it that”) in front of the phrase you want to confirm.

Thus, “Elle est allée à l’épicerie” (She went to the grocery store), in question form, is:

Est-ce qu‘elle est allée à l’épicerie ? (Did she go to the grocery store?)

Or, if you want to really make things easy for yourself, when you want to ask a yes-or-no question, you don’t have to change the sentence structure at all.

Simply say the phrase you are looking to confirm and raise your intonation at the end. We do the same thing in English all the time.

To continue from the previous example, you can ask “Elle est allée à l’épicerie ?” just as you might say “She went to the grocery store?” in English by emphasizing the last syllable.

If you are still a bit confused (I was when I first learned this), you can hear an example here.

Getting the Details: Adjectives

Remember how I said that French adjectives can seem kind of weird because they usually go after the noun they modify, not before? To give a simple example, one would say une maison bleue (a blue house).

Do you also remember how I said that there are exceptions to this? Aaaah, yes. The infamous exceptions to the French grammar rules.

Fortunately, we do have a handy acronym to help remember what these exceptions are, so don’t panic yet! This acronym is BAGS:

- Beauty. Words like joli (pretty) and beau (handsome): un joli tableau (a pretty painting)

- Age. Words such as vieux (old) and jeune (young): un jeune homme (a young man)

- Goodness. Words such as bon (good) and mauvais (bad): un bon livre (a good book)

- Size. Words such as petit (small) and grand (big): une grande ville (a big city)

Since an adjective may come either before or after the noun, it is possible for a noun to have an adjective both before and after it, such as in ma nouvelle robe rouge (my new red dress). Since “new” describe age, it precedes the noun.

How Is That Done? Adverbs

Adverbs describe how something is done. Just as adjectives modify nouns, adverbs modify verbs, adjectives or other adverbs.

J’ai marché lentement au parc. (I slowly walked to the park.)

As in the sentence above, adverbs usually go after the verb (or other word) they modify.

But, as always, there are exceptions! Some adverbs go at the beginning of the sentence. These are generally adverbs that describe time or affect the sentence as a whole.

Hier, j’ai fait le linge. (Yesterday, I did the laundry.)

Heureusement, elle a reçu une bonne note. (Fortunately, she got a good grade.)

Some short, common adverbs like bien (well) and jamais (never), when used with the passé composé (perfect tense), actually go between the participe passé (past participle) and verbe auxiliare (auxiliary verb):

Il était un bon étudiant parce qu’il a souvent étudié. (He was a good student because he studied often.)

To get some practice with all of these patterns, try out this quiz, which tests where to properly place adverbs in a sentence.

Why So Negative? Ne…Pas

Sometimes you should just say no. One of the peculiar things about French is that they use the double negative (meaning you have to, in essence, say “not” twice), which is technically grammatically incorrect in English (e.g., “I don’t have no money”).

So, in order to effectively negate a French sentence, we must include both ne and pas (though often in slang/informal French, ne is omitted). Ne goes before the verb and pas comes after (ne + verbe + pas):

Vous ne pouvez pas me laisser tout seul ! (You cannot leave me all alone!)

In the passé composé, ne comes before the verbe auxiliare and pas goes before the participe passé (ne + verbe auxiliare + pas + participe passé):

Nous n’avons pas compris la leçon. (We did not understand the lesson.)

Need a bit of practice to fully understand this lesson? This quiz tests how to make a French sentence negative using ne…pas and other forms of negation.

I Object! Direct and Indirect Objects

Good news! We have a few more similarities to English.

The direct object goes after the verb it is being acted on:

As-tu lu ce merveilleux livre ? (Have you read this wonderful book?)

Note that merveilleux goes before the noun because it is considered a “goodness” adjective. Plus, you get another example of using inversion to ask a question!

Next comes the indirect object, which, as the name implies, is “indirectly” acted upon by the verb. This may seem a bit confusing at first, but it makes sense once you see what these look like in context:

Il écrit une lettre à son frère. (He wrote a letter to his brother.)

Une lettre (a letter) is the direct object; this is what was written. Son frère (his brother) is the indirect object because he is whom the letter was written for.

On a parlé avec elle ce soir. (We talked with her this evening.)

Here, there is no direct object. But elle (her) is an indirect object because we didn’t talk her; we talked with her.

Note that, sometimes, we must use a preposition such as à (to) or avec (with). As you can see, these prepositions usually correspond to their English counterparts.

Right to the Point: Direct Object Pronouns

Direct object pronouns might seem a bit complicated at first, but in the long run, they do make things easier for you.

Let’s say you are talking with someone about a movie. No one wants to say “Parc Jurassique” (“Jurassic Park”) twenty times. Most likely, you will quickly switch to “it” instead of saying the whole name every time.

That is exactly what direct object pronouns do in French. They replace a previously established direct object with a pronoun.

These include le, la, l’ and les, depending on the object’s gender and number (use l’ if the pronoun goes right before a vowel). Or, if the direct object is a first or second person (me, you, us), you would employ me, te, vous or nous.

J’adore le “Parc Jurassique” ! Je l’ai vu cent fois ! (I love “Jurassic Park”! I’ve seen it a hundred times!)

Since un film (a movie) is masculine, we would use le to replace “Parc Jurassique,” but since the next word begins with a vowel, we make it l’.

As in the previous example, the direct object pronoun goes before the verb. In the passe composé, this means it precedes the verbe auxiliare.

In the present tense, the pronoun will similarly go right before the conjugated verb:

Aimez-vous le français ? (Do you like French?)

Oui, je le trouve merveilleux ! (Yes, I think it is wonderful!)

Now, the futur proche (near future) is a bit different. The pronoun goes after, not before, the conjugated verb:

Avez-vous lu “Notre-Dame de Paris” ? (Have you read “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”?)

Note: The original French title is literally “Notre Dame of Paris,” but for whatever reason, when it was translated, the title was changed.

Pas encore. Je vais le commencer ce week-end. (Not yet. I am going to start it this weekend.)

One more weird thing (I warned you it would seem complicated). When using a direct object pronoun in the passé composé, the participe passé must agree in gender and number with the pronoun. This means adding an “-e” for feminine and/or “-s” for plural.

Comment as-tu trouvé tes nouveaux professeurs ? (What did you think of your new teachers?)

Je les ai trouvés absolument ennuyeux ! (I thought they were absolutely boring!)

Check out this quiz to practice replacing a direct object with a direct object pronoun and properly placing it in a sentence.

Beating Around the Bush: Indirect Object Pronouns

Just as direct object pronouns stand in for a previously established direct object, indirect object pronouns work the same way for indirect objects. Remember, these are objects that are “indirectly” acted upon by the verb.

A simple (English!) example is “I wrote him a letter.” Him is an indirect object because “him” is not what is being written, but “him” nevertheless receives the action because the letter is being written to “him.”

So what makes indirect object pronouns different from direct ones? First, we use different words. The most common include lui for the singular, and leur for the plural.

But if the indirect object is in the first or second person, it becomes me, te, vous or nous, as with direct object pronouns.

The second major difference is that we don’t have to worry about agreement in the passé composé because, again, it receives the action indirectly:

Est-ce qu’il a téléphoné à ses amis ? (Did he call his friends?)

Oui, il leur a téléphoné hier soir. (Yes, he called them last night.)

As you may have noticed in the above example, indirect object pronouns follow the same rules as direct object pronouns when it comes to order.

Qu’est-ce que tu fais pour l’anniversaire de ton père ? (What are you doing for your dad’s birthday?)

Je lui donne une nouvelle montre. (I am giving him a new watch.)

If we want to use both a direct object pronoun and an indirect object pronoun in the same sentence, we will put the direct object pronoun first.

“Elle a acheté ce sac à sa meilleure amie” (She bought this bag from her best friend) would become:

Elle le lui a acheté. (She bought it from her.)

“Nous envoyons un cadeau à nos professeurs favoris” (We are sending a gift to our favorite teachers) would become:

Nous le leur envoyons. (We are sending it to them.)

To try your hand at this, take a look at this quiz, which has you identify the sentence with an indirect object pronoun that could replace the sentence they give you.

Last, But Not Least: En and Y

En and y are similar to direct and indirect objects in that they replace an understood phrase (meaning you don’t have to repeat the same few words over and over).

En replaces phrases beginning with a partitive article (de, du, de la, d’), which is used to, in essence, denote an indeterminate “part” of something, like in du chocolat (some chocolate).

En may also replace most phrases beginning with some form of de, such as when it is employed with an infinitive.

“J’ai décidé de passer mes vacances en France” (I decided to spend my vacation in France) could become simply:

J’en ai décidé. (I have decided on it.)

Finally, en stands in for phrases expressing number or quantity.

For instance, if a specific number is given, as in “Il a lu cinq livres ce mois” (He read five books this month), then we replace the noun with en and retain the number itself at the end of the sentence:

Il en a lu cinq ce mois. (He read five of them this month.)

Y, on the other hand, will replace most phrases beginning with à, au or aux and phrases specifying location.

For example, “J’habite à Chicago depuis six mois” (I have lived in Chicago for six months) might become:

J’y habite depuis six mois. (I have lived there for six months.)

As you have probably noticed, both en and y go before the verb, just like direct and indirect object pronouns do.

If we were to use en and y in the same sentence, y would go first.

I know this is a lot to remember, and it understandably takes time and practice to get it down. Even then, review is always helpful. A good first step (or refresher!) is this short quiz that tests use of en and y, as well as some of the object pronouns we covered earlier.

Order, Please!

Direct objects. Indirect objects. En. Y. If your head is spinning, take a few deep breaths and take a look at this list, a simple review of the proper order for all these helpful (and perhaps a bit confusing) words:

- Me, te, nous, vous

- Le, le, les, l’

- Lui, leur

- Y

- En

It is understandable if you still feel overwhelmed by all there is to know about French word order.

But remember that skyscrapers aren’t erected overnight; they take detailed planning and careful construction.

In fact, it may take years to go from idea to reality.

Similarly, learning a new language does take time and work, but the view from the top is worth it!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How to tell the time in French? Learn the many ways of telling the time in French with audio (casual & official French time), & useful French time expressions.

If you travel to a French speaking country, chances are that you’re going to have to understand or tell the time in French. Admittedly, there are many ways of telling the time in French, so it can be a bit confusing…

But fear not! My free lesson will teach you the time in French in… no time at all!

And thanks to my audio recordings, you will know the difference between “deux heures” and “douze heures” and won’t miss your train!

This free French lesson – like many on French Today’s blog – features audio recordings. Click on the link next to the headphones to hear the French pronunciation.

Let’s dive right in and see how to tell the time in French.

How To Say Hour in French?

The French word you’ll hear the most for time in the context of telling the time is the word “heure”. It’s a feminine word, and because “heure” starts with a silent h, its pronunciation will vary a lot in liaison, so it’s essential you learn how to tell the time in French with audio recordings.

French Time Pronunciation

This free French lesson – like many on French Today’s blog – features audio recordings. Click on the link next to the headphones to hear the French pronunciation.

I encourage you to repeat out-loud after me so you memorize the right way to tell the time in French.

- It’s one o’clock – Il est une heure (note there is no S at heure since there is only one)

- It’s two o’clock – Il est deux heures

- It’s three o’clock – Il est trois heures

- It’s four o’clock – Il est quatre heures

- It’s five o’clock – Il est cinq heures

- It’s six o’clock – Il est six heures

- It’s seven o’clock – Il est sept heures

- It’s eight o’clock – Il est huit heures

- It’s nine o’clock – Il est neuf heures

- It’s ten o’clock – Il est dix heures

- It’s eleven o’clock – Il est onze heures

- It’s twelve o’clock – Il est douze heures

Repeating the Word Hour in French.

In French, when you tell the time, you always have to repeat the word “heure(s)”. This is the biggest mistake I hear English speakers make when telling the time in French: they forget to include the word “heure”.

In English, you can say : ‘it’s one’.

In French you have to say: “Il est une heure“, saying the word “heure”.

In English you can say: ‘it’s quarter past one’.

In French you have to say: “il est une heure et quart“, saying the word “heure”.

The word heure(s) is pronounced in the same breath as the number, as if it were a weird ending to it.

The key to understanding the time in French

So as you can hear with the audio recordings, the word “heure” becomes neur, zeur, treur, keur, teur with the liaisons and glidings.

Mastering the right pronunciation of the word hour in French is the key to understanding the time in French.

Knowing your French numbers from 0 to 59

Now, to tell the time efficiently and understand it, you need to first learn how to say the numbers in French.

In this lesson, I’m going to concentrate on the expressions and pronunciation differences but I won’t go over how to say the numbers 0 to 59. Please follow this link to learn how to count in French.

How do you Write the Time in French?

Note: in writing, the word “heure” is abbreviated as “h”, not the English “:”.

We don’t write nor say the word “minute” when we say the time, but if you need to abbreviate the word minute, it would be “mn” in French.

- 1:45 in French would be written 1 h 45

- 45 minutes in French would be abbreviated as 45 mn

More Ways To Tell the Time in French

As I said in the intro, there are many ways of telling the time in French.

The 24 Hour French Clock

In French, all the official schedules (TV, radio, trains, planes etc…) use what you call in English “military time”.

Based on a 24 hour clock, you say exactly the number of hour, then the number of minutes.

Note that we don’t say “hundred” for a round hour like you do in English: in French, we just say the hour number. But don’t forget to say the word heure(s)!

- Il est treize heures quarante-cinq = it’s 13:45.

- Il est vingt heures = it’s 20:00.

Check out my French number audiobook. Over four hours of clear explanations, and random number drills recorded at several speeds. Click on the link for more info, a full list of content and audio samples.

This 4+ hours audiobook goes in-depth on how to construct the numbers and how to properly pronounce them with all the modern glidings and elisions that can sometimes completely change the number from it’s written form!

I also cover many French expressions that use numbers as well as how to properly tell the time and understand prices.

Mastering French Numbers

Master All Numbers From 0 To 999 999 999! The most in-depth audiobook about French numbers anywhere

More Details & Audio Samples

All throughout the audiobook, you will find extensive audio drills recorded at 3 different speeds and featuring numbers out of order so you really get a true workout!

Back to studying the time in French.

Minutes Past & to the Hour

This way of telling the time in French is pretty much the same as in English. You just say the number of minutes to or past the hour.

- 1 h 45

It’s fifteen to two – il est deux heures moins quinze

It’s forty-five past one / it’s one forty-five – il est une heure quarante-cinq

Common French Time Expressions

Just like in English, we also use common French time expressions in France, like saying ‘noon’ instead of 12PM.

Let’s learn them!

| noon | midi |

| midnight | minuit |

| and a quarter | et quart |

| quarter to | moins le quart |

| and a half | et demie |

| in the morning | du matin |

| in the afternoon | de l’après-midi |

| in the evening | du soir |

How To Say Quarter Past in French?

To translate the time notion of ‘quarter past’ in French, we say “et quart”.

- It’s quarter past one: il est une heure et quart.

Note the difference between quart (pronounced car) et quatre (4).

How To Say Quarter To in French?

To translate the time notion of ‘quarter to’ in French, we say “moins le quart” (quarter of – pronounced car)

- It’s quarter to four: il est quatre heures moins le quart.

You also want to glide your “le” as much as possible – it almost disappears in modern spoken French pronunciation.

How To Say Half Past in French?

to translate the time notion of ‘half past’ in French, we say “et demie “(and an half, half past the hour)

- It’s half past one: il est une heure et demie.

Note: we glide over the first “e” of demie = dmee in spoken French.

How to Say Noon and Midnight in French?

The French language has equivalents of noon and midnight :

- it’s noon – il est midi

- it’s midnight – il est minuit

Note that these 2 French time expressions do not require the word heure since their position in the day is self-implied.

I strongly recommend that you use these, since “douze heures” sounds a lot like “deux heures” when you make the liaison…

“deux heures” versus “douze heures”

Otherwise, in official time midi is “douze heures” and minuit is “zéro heure” (no S at heure).

How to say AM and PM in French?

You could also be using the twelve hour clock and then add the expressions du matin in the morning, de l’après-midi in the afternoon, du soir in the evening…

Now let see some useful French time sentences.

13 French Time Sentences

Please press play on the audio player to hear my audio recordings. I left enough time for you to repeat out-loud and I encourage you to do it!

- Quelle heure est-il ? = what time is it?

- Il est quelle heure ? = what time is it? (street French)

- Auriez-vous l’heure, s’il vous plaît ? = would you tell me the time, please?

- Tu peux me donner l’heure ? = can you give me the time (street French)

- C’est à quelle heure ? = at what time is it?

- Il est neuf heures pile, neuf heures précises = it’s nine sharp.

- Il est presque minuit = it’s almost midnight

- Il est moins dix = it’s 10 minutes to whatever hour it is now…

- Mon cours commence à la demie = my lesson starts at – whatever hour it is now – thirty.

- C’est ouvert de quelle heure à quelle heure ? = it’s open from what time to what time?

- Le concert est à quelle heure? = at what time is the concert

- Il arrive dans trois quarts d’heure = he’ll be there in 45 minutes.

- Ce magasin est ouvert 24 heures sur 24 = this shop is open all day and all night long (a concept almost unheard of in France

3 Ways to Translate Time in French

Watch out! There are three ways to translate the word ‘time’ in French.

1 – Time as in telling time is “l’heure” in French.

What time is it?

Quelle heure est-il ?

2 – Time as in a period of time is “le temps” in French

I would like to spend some time in France.

J’aimerais passé du temps en France

3 – Time as in instance is “la fois” in French.

How many times have you been to Paris?

Tu es allé à Paris combien de fois ?

How Should I Tell the Time in French?

So, which method should you use to tell the time in French? 12 hour clock, 24 hours official time, minutes past or to the hour, expressions of time?

It’s really up to you. My tip: pick one method and stick to it when you speak so you don’t hesitate…

However you will eventually need to understand all of the various ways of telling the time in order to understand the French when they speak. Bookmark this free lesson and come back to it often!

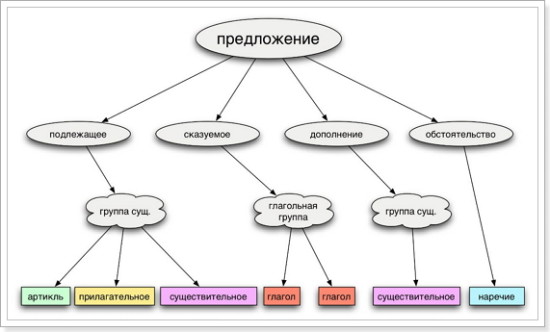

Итак, вы познакомились со спряжением глаголов всех трех групп в настоящем времени, а значит, теперь вы можете составлять предложения! Как же это делать?

Порядок слов в предложении

Для начала определимся с порядком слов во французском предложении. В отличие от русского языка, во французском порядок слов фиксированный — это значит, что у каждой части предложения есть свое место, и изменится оно может только под влиянием правил:

Подлежащее + Сказуемое + Остальные части предложения

Не забудьте, что подлежащее отвечает на вопросы «кто?», «что?» и обычно выражено существительным или местоимением, а сказуемое — на вопросы «что делает?» и выражается глаголом. Последовательность подлежащего и сказуемого в предложении также называется прямым порядком слов.

Существительные-подлежащие в единственном числе можно заменять местоимениями «il» или «elle». Однако, помните, род многих существительных французского языка не соответствует аналогичным словам русского языка, поэтому будьте внимательны, когда производите замену.

Если вы хотите рассказать о своих привычках, предпочтениях или повседневных делах, вам потребуется простое настоящее время: во французском языке оно называется Présent. С его образованием вы уже знакомы — см. уроки 6, 7, 10, 11. Но мало знать, как образуется то или иное время, необходимо помнить, когда его нужно употреблять.

Правила употребления Présent

используется:

- для обозначения повторяющегося действия или привычки. Например: Je vais au travail à pied. — Я хожу на работу пешком;

- для констатации какого-либо факта. Например: J’habite à Rome.— Я живу в Риме;

- для обозначения действия, которое происходит в настоящий момент: Il ecrit une lettre. — Он пишет письмо;

- для обозначения будущего действия вместе с наречиями времени, например: Elle part demain. — Она уезжает завтра;

- для выражения действия в прошлом. Как говорилось ранее, в данном случае использование Présent приобретает особую выразительность и может использоваться, как стилистический прием.

Также для выражения того, что происходит в данный момент, можно использовать словосочетание etre en train de + инфинитив. Не забудьте использовать нужную форму глагола «etre». Например: Nous avons en train de regarder le film. – Мы смотрим фильм.

Чтобы опровергнуть какой-то факт, вам потребуется уже знакомый оборот «ne…pas», например: Je ne parle pas italien. — Я не говорю по-итальянски.

Чтобы задать вопрос, можно использовать несколько способов. Вы с ними уже знакомы:

- С помощью интонации: Tu habites à Rome? — Ты живешь в Риме?

- При помощи инверсии, изменения порядка слов: Habites-tu à Rome?

- С помощью оборота «est-ce-que», который ставится перед предложением. Порядок слов в данном случае менять не нужно: Est-ce-que tu habites à Rome?

Если вопрос необходимо задать к подлежащему, которое выражено существительным, используется сложная инверсия. Попробуем разобраться что это значит., на нескольких примерах:

Jean et Robert habitent à Rome. — Jean et Robert habitent-ils à Rome?

Pierre parle français. — Pierre parle-t-il français?

Как видите, подлежащее ставится на первое место, после чего используется глагол и местоимение, заменяющее подлежащее. Если глагол оканчивается на гласный -a или -е (это бывает в 3-ем лице единственного числа), между глаголом и местоимением появляется буква «t».

Если вопрос нужно задать к предложению, начинающемуся с c’est (это), вам поможет изменение порядка слов, при этом c’est меняется на не сокращенную форму est-ce [эс]. Также вопрос можно задать при помощи интонации. Например: C’est un médecin. — Est-ce un médecin? C’est un médecin? — Это врач?

Вот те важные моменты, которые необходимо помнить о настоящем времени. Пора закрепить теорию на практике!

Задания к уроку

Упражнение 1. Допишите окончания глаголов 1-ой и 2-ой группы, ориентируясь на местоимения. Выполнить это предложение правильно вам поможет урок 10.

1) Nous habit… . 2) Tu chois… . 3) Elles parl… . 4) Ils applaud… . 5) Vous aim… . 6) Il travaill… . 7) Nous mang… . 8)Vous grand… . 9) Il jet… . 10) Nous commenc… .

Упражнение 2. Составьте отрицательные предложения и вопросы при помощи инверсии.

1) Ils habitent à Moscou. 2) Je travaille au bureau. 3) Elle parle français. 4) Robert part demain. 5) C’est une étudiante.

Ответ 1.

1) Nous habitons. 2) Tu choisis. 3) Elles parlent. 4) Ils applaudissent. 5) Vous aimez. 6) Il travaille. 7) Nous mangeons.

Ответ 2.

1) Ils ne habitent pas à Moscou. Habitent-ils à Moscou? 2) Je travaille au bureau. 3) Elle ne parle pas français. Parle-t-elle français? 4) Robert part demain. Robert part-il demain? 5) C’est n’une pas étudiante. Est-ce une étudiante?

Working as a French coach, I’ve noticed that French word order is one of the trickiest things for English speaking students. Building French sentences, especially as you speak, can be very challenging.

Luckily, there are a few tricks that can help you solve this issue. So that’s what we’ll see today: 7 rules of thumb that you can apply right now to make better French sentences with less effort.

Watch the video, or read on below.

How to build a sentence in French easily — French word order tips & tricks French word order can be tricky. In this video, I’ll show you how to build a sente…

-

French word order is 80% similar to English word order

French word order isn’t totally random. It’s actually 80% similar to English word order.

Linguists like to categorize languages according to the order of the three main components of a sentence: subject, verb and object (SVO).

All possible combinations (SOV, SVO, VSO, VOS, OSV, OVS) exist among human languages, but each language has a fixed order. Only 33% of languages follow the “SVO” order, including English and French. So we got pretty lucky there.

I speak English. ↔ Je parle anglais.

In this simple sentence, you can see that the words are in the exact same order in French and in English. We can be grateful for this, as most other languages wouldn’t have this particularly.

This means that, in regards to French word order, an English native’s intuition will be correct most of the time.

As often though, the devil is in the details.

There are a lot of details that I can’t possibly include in a simple blogpost like this. In fact, I created a 69-minutes workshop (available in the French Fluency Accelerator), where I explain all the details one by one in an easy to understand, progressive manner. So, if you get value from this article, I encourage you to join the program, as you’ll get even more value from it.

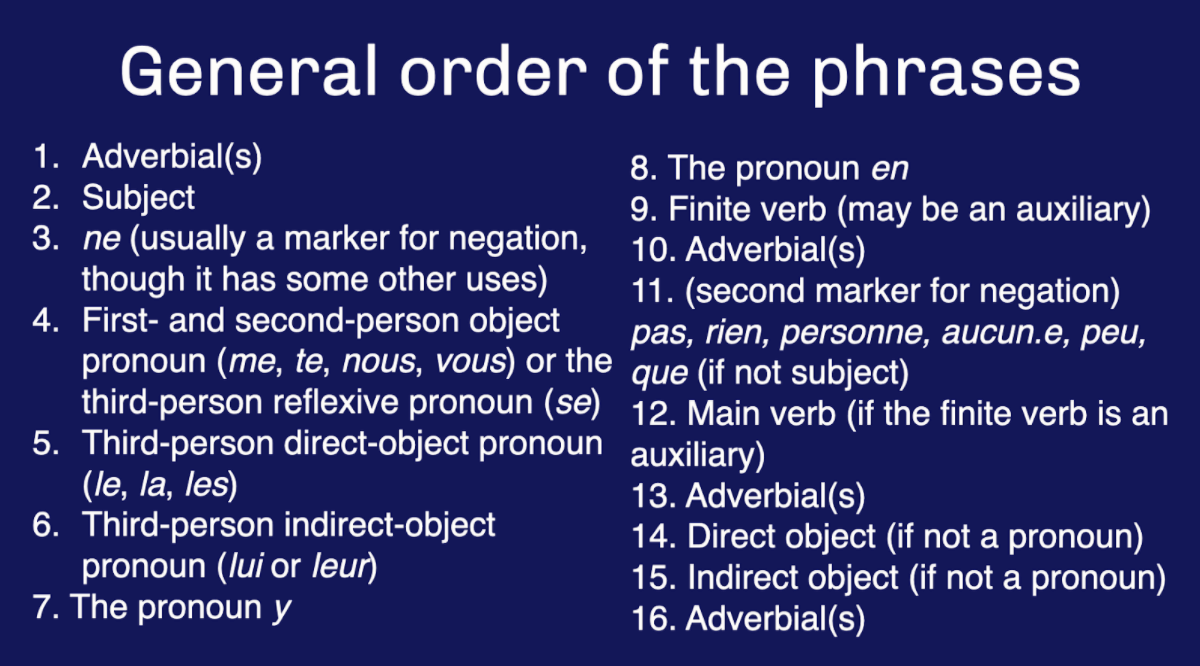

When creating that workshop, I fell down a rabbit hole when I realized that, no matter how good you are at searching the internet, it was impossible to get clear and exhaustive information about French Word Order. Even the wikipedia article about French grammar had it wrong. I eventually edited it to reflect the actual word order of French sentences, with all of its 16 (!) positions.

Here is a slide from the workshop showing all 16 positions:

If you don’t understand everything on this slide, don’t worry, you don’t need to. All French speakers speak intuitively and do not know this order formally. As a learner, you can rely on the following rules of thumb:

2. Make simpler sentences.

As we saw, all important elements are in the same order in English and in French. It’s only the details that trip you up.

The best solution is often to make simpler, shorter sentences, and use more sentences to express your thoughts. This way, you will make the most of the basic sentences structure, and avoid most of those challenging details.

I have shared more about this strategy and why it works in this in this article + video.

3. Use less clauses.

The 16 positions above aren’t even the order of words in a sentence. They’re actually the order of words in each clause.

A sentence can have several clauses. In fact, there’s no limit to how many clauses you can string together into one sentence.

But the more clauses you include, the more challenging it is to make the sentence grammatically correct. And the harder it is for the listener to understand what you mean, even in English.

Of course, when you speak a foreign language, it only gets worse.