fausse

Summary

The French translation for “false; fake (feminine singular)” is fausse.

See also

Examples of «false; fake (feminine singular)» in use

There are 2 examples of the French word for «false; fake (feminine singular)» being used:

Practice Lesson

Themed Courses

Part of Speech Courses

-

#1

I’ve noticed that in a few languages, like German and French, the word for «false» can also mean «wrong/incorrect». For example, you can say «Your sentence is false» when you mean that it has grammatical errors. In English and Portuguese this does not work. What about your language?

Thanks in advance.

-

#2

This doesn’t work in Danish:

falskt ≠ forkert

-

#3

Hard question to answer for

Dutch

, because we have two words for ‘false’ but neither of them is used in the same way as the English term. They are vals < Fr. faux and fout, derived from the noun fout ‘fault, mistake’ < Fr. faute. By the way, French faute and faux are also related. Additionally we also borrowed foutief from French, and there’s Germanic verkeerd ‘wrong’.

Vals denotes things that are unreal or insincere upto being simply wicked, mean. It could sometimes be translated with ‘false’: e.g. vals alarm ‘false alarm’. I can only think of one instance where it should actually be translated with ‘wrong’: valse noot ‘wrong note’.

Fout is more like ‘wrong’, to be applied with faults and mistakes. So, yes, you could say die zin is fout ‘that sentence is wrong’. (Foutief is about the same but it is used way less often.)

Verkeerd is the most like ‘wrong’ — it actually evolved from the same kind of meaning: ‘twisted’. Unlike fout, it is not used meaning ‘untrue, (false)’.

-

#4

We use the same term for both ideas in Gaelic – ceàrr (pronounced kyarr)

-

#5

I’ve noticed that in a few languages, like German and French, the word for «false» can also mean «wrong/incorrect». For example, you can say «Your sentence is false» when you mean that it has grammatical errors. In English and Portuguese this does not work. What about your language?

Thanks in advance.

In

Indonesian

there is a difference between palsu (loanword from Portuguese falso) and salah.

-

#6

In Arabic you use the same word. i.e. false = khata’ — wrong = khata’

-

#7

In Italian we use two different words:

False = falso

Wrong = sbagliato

-

#8

Turkish:

false/wrong: yanlış

-

#9

Serbian (I’m giving just the most common adjectives):

false — lažan, neistinit (untrue, artificial, feigned, pseudo)

wrong — netačan, nepravilan, pogrešan etc. (incorrect, mistaken, inaccurate, not the right one etc.)

So far I can find only one adjective that

partly

«covers» both meanings — manjkav (the closest meaning is «having a fault/flaw» or «missing a part»):

Rečenica ti je manjkava. («Your sentence is not correct» — meaning that something is missing, it’s not quite correct.)

Njegova priča je manjkava. («His story is false» — meaning that it causes doubt, something is missing again, so it can’t be quite truthful.)

-

#10

In Arabic you use the same word. i.e. false = khata’ — wrong = khata’

I’m unsure as to the exact distinction Persian makes between «wrong» and «false», but «khataa'»/»xataa» is oneway of saying «wrong». «Qalat» means just downright «wrong», «eshtebaa» is used to mean «mistaken» or «incorrect». Also, one could always say «dorost nist» («He/she/it is not correct/right/true»).

-

#11

In Hungarian it’s difficult to answer that.

th word for false is hamis, which can also mean fake, counterfeit but not wrong.

the word for wrong is hibás, which can be used for false,

i think everybody gets it.

-

#12

I’m unsure as to the exact distinction Persian makes between «wrong» and «false», but «khataa'»/»xataa» is oneway of saying «wrong».

In Arabic, khata’ خطأ is something wrong/false/incorrect — it is the opposite of correct. Ghalat غلط is something that is used/put/applied/said incorrectly, but it can be correct itself. Ghalat is closer to «mistake» although not identical.

-

#13

In Arabic you use the same word. i.e. false = khata’ — wrong = khata’

Maha, allow me to disagree a bit. False (like the French «faux») means زائف or مزيف . So, in Arabic, we have khata’ for wrong, and zà’if or muzayyaf for false.

Which doesn’t mean that khata’ doesn’t mean false, I just wanted to note that «false» has other meanings in Arabic.

I’m unsure as to the exact distinction Persian makes between «wrong» and «false», but «khataa'»/»xataa» is oneway of saying «wrong». «Qalat» means just downright «wrong»

Ghalat غلط is something that is used/put/applied/said incorrectly, but it can be correct itself. Ghalat is closer to «mistake» although not identical.

Are you sure that something «ghalat» can be correct in itslef? I think we use this word the same way as in Persian.

-

#14

Maha, allow me to disagree a bit. False (like the French «faux») means زائف or مزيف . So, in Arabic, we have khata’ for wrong, and zà’if or muzayyaf for false.

Which doesn’t mean that khata’ doesn’t mean false, I just wanted to note that «false» has other meanings in Arabic.

I understood false as in «Answer the following with True or False»; in which case false = khata’; I did not understand false as fake in which case it would be مزيف. As I’m sure you are aware, you can never have a word-for-word translation from Arabic to English, it alsways depends on the context or on how you understand the word (as in this case) even if it is less so in some cases.

Are you sure that something «ghalat» can be correct in itslef? I think we use this word the same way as in Persian.

This I am positive about; in order not to get off topic, I’ll open a new thread in the Arabic forum.

-

#15

I understood false as in «Answer the following with True or False»; in which case false = khata’; I did not understand false as fake in which case it would be مزيف.

I thought so But as I know some French, I guess it helped me know what was Outsider talking about, unless I’m mistaken of course.

As I’m sure you are aware, you can never have a word-for-word translation from Arabic to English, it alsways depends on the context or on how you understand the word (as in this case) even if it is less so in some cases.

Of course. We agree about that.

Thanks for the new thread in the Arabic forum.

-

#16

In Italian we use two different words:

False = falso

Wrong = sbagliato

It´s similar in spanish:

Falso=falso

Wrong=equivocado/erróneo

-

#17

I was not so interested in «false» in the sense of «counterfeit», although, in the languages that I know, including that meaning does not make any difference.

Perhaps it does in Arabic. Still, the contrast that interests me mostly is between «false» in the logical sense, and «wrong/incorrect» in the sense of not being the right answer to a question, or not being the right way to do something.

- It is false that 2+2=5.

- The sentence «This is just between you and I» is

falsewrong/incorrect.

It is true that «wrong» and «incorrect» could also be used in the first sentence, but I hope you can see the distinction I’m making…

-

#18

In that case, Maha’s post stands as perfectly correct

-

#19

I’ve noticed that in a few languages, like German and French, the word for «false» can also mean «wrong/incorrect». For example, you can say «Your sentence is false» when you mean that it has grammatical errors. In English and Portuguese this does not work. What about your language?

Thanks in advance.

Outsider,

Actually the only time when you say «This sentence is false» in French is when you do mean truth value. An example would be when you’re discussing logic puzzles or logic theory. In any other context you would say properly «This sentence is correct/incorrect»: Cette phrase est correcte/incorrecte (in a grammatical sense). Sometimes people will use instead «bonne/mauvaise» (good/bad) but never will they use «true/false» («vraie/fausse») in the way you suggest …

BRD

-

#21

I think you are mistaken. I have seen, even in this forum, exchanges like the following:

P.S. Here are a few real examples:

-snip-

I hope this is convincing enough.

Not quite. In these quotes «faux» (false) is used in sentences where the adverb «grammatically» (grammaticalement) is implicitly used. The same applies to English where people commonly use phrases like «This sentence is grammatically false».

Although in both instances (French and English), the proper word to use would have been «correct» (as in «This sentence is grammatically correct» or «Cette phrase est grammticalement correcte)

Anent the «recent thread» example it only shows the difference between the form/syntax and the meaning. In this context «true/false» applies to the assertion the sentence is making that is, to the meaning itself. The walking professor might have answered either «True», «Correct» or «Good» («Vrai», «Correct» or «Bon») and would have been … correct in both languages

BRD

-

#22

In these quotes «faux» (false) is used in sentences where the adverb «grammatically» (grammaticalement) is implicitly used. The same applies to English where people commonly use phrases like «This sentence is grammatically false».

I didn’t know you could say that in English!

I’d never heard it before. In any case, you certainly can’t say it Portuguese, or several other languages. The word that means «false» cannot be used in the sense of «[grammatically] incorrect».

Although in both instances (French and English), the proper word to use would have been «correct» (as in «This sentence is grammatically correct» or «Cette phrase est grammticalement correcte)

I was not under the impression that the use of faux in the French examples I gave was improper. I just see it as a difference in the meaning of cognates that belong to different languages. Semantic broadening and divergence, to use a fancy phrase. It’s interesting, but nothing extraordinary. What makes you say that incorrecte would be more proper than faux?

-

#23

I didn’t know you could say that in English!

Well, you could use Google to check it out

I’d never heard it before. In any case, you certainly can’t say it Portuguese, or several other languages. The word that means «false» cannot be used in the sense of «[grammatically] incorrect».

Well, as I said it’s not a proper usage but it’s common for people to mix up syntax and semantic. So «correct/incorrect» should refer to the syntax, when «true/false» should refer to the meaning. But since «correct/incorrect» is used for both syntax and semantic (as in «- You have 2 children? -Correct») people tend to do it the other way around and use «true/false» when referring to the syntax.

I was not under the impression that the use of faux in the French examples I gave was improper. I just see it as a difference in the meaning of cognates that belong to different languages. Semantic broadening and divergence, to use a fancy phrase. It’s interesting, but nothing extraordinary. What makes you say that incorrecte would be more proper than faux?

Well, for the reason quoted above: abusive confusion between syntax/grammar and semantic. To be fair this stands for French as used in France but I don’t see why the argument shouldn’t apply to other regions as well.

BRD

-

#24

I didn’t know you could say that in English!

I don’t think you *can* say «This sentence is grammatically false» in standard English, however many google hits there may be for it (I haven’t checked)

I wonder if the French use of «faux» implies «false logic»?

EDIT. I’ve since checked the number of google hits for «grammatically false». There are a total of 139, of which many appear to be written by non-native speakers. QED.

-

#25

I don’t think you *can* say «This sentence is grammatically false» in standard English, however many google hits there may be for it (I haven’t checked)

![Big Grin :D :D]()

I don’t think it’s a proper way to say it either in French of in English but people do My post was an attempt at explaining why people would be tempted to do so …

I wonder if the French use of «faux» implies «false logic»?

I take it by «false logic» you mean buggy logical reasoning, right?

Let’s see: consider a student saying: «2 + 2 = 5»

— From the perspective of a well-written arithmetic formula this is correct

— From the perspective of a formal system describing arithmetic this is not a theorem

— From the perspective of natural numbers, this assertion is false.

Although all of the 3 domains above are somewhat well mathematically differentiated, in day-to-day life they are often considered as equivalent.

So whether the French or the English speaking teacher uses «incorrect», «impossible» or «false» it carries the same practical intent: «You’re a moron!»

BRD

-

#26

I don’t think it’s a proper way to say it either in French of in English but people do

![Smile :) :)]()

But I don’t think it’s improper French. We might have to agree to disagree about this (I did not understand your previous explanation). I see native speakers speak and write that way all the time. Is there any grammar of French that condemns this use of faux? Does the Académie Française condemn it?

Anyway, welcome to the forum, and merry Christmas.

-

#27

To expand on MarX, in Malay, «false» would typically use palsu. This word would be used in the context of «fake» or «counterfeit». «Wrong» would be translated as salah and used in the sense of «a wrong answer». Silap would connote a «mistake» or «unintentional error». «True or false?» would best be translated as benar atau tidak (Literally «True or not»)?

-

#28

Thanks for your warm welcome Ousider, merry Christmas to you too.

Ok, here goes my argument of «authority» : when I was 15 y.o. my French teacher -who also was «an agrégé de grammaire» (it does not get more authoritative than when teaching French grammar)- did not condone it; NOT because it was violating French grammar rules per se, but because of pragmatic knowledge. «true/false» should apply only to the meaning of a sentence and not its syntax which is correct/incorrect. In other word, a sentence is never true or false, it’s just a sentence. But the fact(s) expressed by this sentence can be «true» or «false».

Another way to look at it: in order to decide if a sentence is correct or incorrect you generally don’t need to look at anything else than at the sentence itself an at the grammar rules (and obviously the vocabulary) of a given language. To decide if a fact is true or false (and yes one also says that a fact is «correct» or «incorrect») you need to appeal to your understanding of the world (e.g. «The moon is closer from earth than the sun») is «true» only because you know of Astronomy (independently of any language).

Finally, the fact that people are using certain forms does not mean they are correct. For instance many (Most) French speaking persons are using the «subjonctif» tense after «après que» (e.g saying improperly «Après qu’il ait monté l’escalier» instead of «Après qu’il a monté l’escalier») I have no doubt than the next generation will accept this as the proper usage … Right now it’s debatable and that was certainly not accepted at the beginning of the 20th century …

BRD

-

#29

[B said:

BigRedDog[/B]]In these quotes «faux» (false) is used in sentences where the adverb «grammatically» (grammaticalement) is implicitly used. The same applies to English where people commonly use phrases like «This sentence is grammatically false».

Outsider said:

I didn’t know you could say that in English!

I’d never heard it before.

Outsider is correct. The statement is poppycock. It may be grammatically correct, but the content is a blatant falsehood. It’s wrong. In English people do not «commonly use phrases like» the one presented.

I have taken the dare, and looked for it using Google. Here is the underwhelming result:

Results 1 — 1 of 1 for «This sentence is grammatically false».

You can stand on your head and spit wooden nickels before you will convince me that English speakers use such statements. (

Results 1 — 20 of about 87 for «Stand on your head and spit wooden nickels».)

In the opening post, it was stated accurately that English does not allow for this use of false.

For example, you can say «Your sentence is false» when you mean that it has grammatical errors. In English and Portuguese this does not work. What about your language?

If someone has any real evidence to contradict that true statement, it would be interesting to see it. If not, perhaps it would be best to address the thread question.

-

#30

Outsider is correct. The statement is poppycock. It may be grammatically correct, but the content is a blatant falsehood. It’s wrong. In English people do not «commonly use phrases like» the one presented.

-snip-

In the opening post, it was stated accurately that English does not allow for this use of false.

If someone has any real evidence to contradict that true statement, it would be interesting to see it. If not, perhaps it would be best to address the thread question.

Well cuchuflete although you might be right in that it’s not frequent, you’re certainly wrong in thinking it’s not used in English; using Google on «grammatically false» instead, you will see that sources as different as Oxford journals and Wikipedia articles are using the expression.

BRD

-

#31

I don’t think you *can* say «This sentence is grammatically false» in standard English, however many google hits there may be for it (I haven’t checked)

I wonder if the French use of «faux» implies «false logic»?

EDIT. I’ve since checked the number of google hits for «grammatically false». There are a total of 139, of which many appear to be written by non-native speakers. QED.

139 total Google citations does not indicate frequency. To the contrary, it shows that an expression is quite rare in English. To call such an expression, with or without the rest of the sentence presented as ‘commonly’ used is a falsehood.

Beating a dead horse won’t bring the equine back to life.

Well cuchuflete although you might be right in that it’s not frequent, you’re certainly wrong in thinking it’s not used in English; using Google on «grammatically false» instead, you will see that sources as different as Oxford journals and Wikipedia articles are using the expression.

Defending—or trying to defend—what you didn’t originally say does nothing to support the original assertion, which was wrong. «Grammatically false» is a rarity in English. Outsider based this thread on a legitimate statement. Nothing presented subsequently has undermined that statement. Você acha?

-

#32

Defending—or trying to defend—what you didn’t originally say does nothing to support the original assertion, which was wrong. «Grammatically false» is a rarity in English. Outsider based this thread on a legitimate statement. Nothing presented subsequently has undermined that statement. Você acha?

I fail to see your point, I agreed it was less common than I thought initially. As to your obvious willingness to flame, what can I say?

Have a merry Christmas!

BRD

-

#33

I fail to see your point, I agreed it was less common than I thought initially.

Some more Google search reveals:

Instances of «grammatically false» and «grammatically incorrect» are 134 vs. 136 000 (the latter being surely a rounded number).

This means that out of all the instances that necessitate a relevant expression only 0.1% was materialised as «grammatically false.» This means that a large aggregate community as described by the Google search results almost always rejects «grammatically false.»

-

#34

Tagalog:* False= Huwad or mali’ / ** Wrong= mali’ or sala’ E.G. 1.) Your answer is false= mali ang sagot mo. 2.) You use the wrong word= Ginamit mo ang maling salita. 3.) Wrong thoughts= salang pag iisip 4.) The predicted period is incorrect= ang hula sa panahon ng kaganapan ay sala’.

French and English have hundreds of cognates (words which look and/or are pronounced alike in the two languages), including true (similar meanings), false (different meanings), and semi-false (some similar and some different meanings). A list of hundreds of false cognates can be a bit unwieldy, so here is an abridged list of the most common false cognates in French and English.

Common False Cognates in French and English

Actuellement vs Actually

Actuellement means «at the present time» and should be translated as currently or right now:

- Je travaille actuellement — I am currently working

A related word is actuel, which means present or current:

- le problème actuel — the current/present problem

Actually means «in fact» and should be translated as en fait or à vrai dire.

- Actually, I don’t know him — En fait, je ne le connais pas

Actual means real or true, and depending on the context can be translated as réel, véritable, positif, or concret:

- The actual value — la valeur réelle

Assister vs Assist

Assister à nearly always means to attend something:

- J’ai assisté à la conférence — I attended (went to) the conference

To assist means to help or aid someone or something:

- I assisted the woman into the building — J’ai aidé la dame à entrer dans l’immeuble

Attendre vs Attend

Attendre à means to wait for:

- Nous avons attendu pendant deux heures — We waited for two hours.

To attend is translated by assister (see above):

- I attended the conference — J’ai assisté à la conférence

Avertissement vs Advertisement

Un avertissement is a warning or caution, from the verb avertir — to warn. An advertisement is une publicité, une réclame, or un spot publicitaire.

Blesser vs Bless

Blesser means to wound, injure, or offend, while to bless means bénir.

Bras vs Bras

Le bras refers to an arm; bras in English is the plural of bra — un soutien-gorge.

Caractère vs Character

Caractère refers only to the character or temperament of a person or thing:

- Cette maison a du caractère — This house has character.

Character can mean both nature/temperament as well as a person in a play:

- Education develops character — L’éducation développe le caractère

- Romeo is a famous character — Romeo est un personnage célebre

Cent vs Cent

Cent is the French word for a hundred, while cent in English can be figuratively translated by un sou. Literally, it is one-hundredth of a dollar.

Chair vs Chair

La chair means flesh. A chair can refer to une chaise, un fauteuil (armchair), or un siège (seat).

Chance vs Chance

La chance means luck, while chance in English refers to un hasard, une possibilité, or une occasion. To say «I didn’t have a chance to…» see Occasion vs Occasion, below.

Christian vs Christian

Christian is a masculine French name while Christian in English can be an adjective or a noun: (un) chrétien.

Coin vs Coin

Le coin refers to a corner in every sense of the English word. It can also be used figuratively to mean from the area:

- l’épicier du coin — the local grocer

- Vous êtes du coin ? — Are you from around here?

A coin is a piece of metal used as money — une pièce de monnaie.

Collège vs College

Le collège and le lycée both refer to high school:

- Mon collège a 1 000 élèves — My high school has 1,000 students

College is translated by université:

- This college’s tuition is very expensive — Les frais de scolarité à cette université sont très élevés.

Commander vs Command

Commander is a semi-false cognate. It means to make an order (command) as well as to order (request) a meal or goods/services. Une commande is translated by order in English.

Command can be translated by commander, ordonner, or exiger. It is also a noun: un ordre or un commandement.

Con vs Con

Con is a vulgar word that literally refers to female genitalia. It usually means an idiot, or is used as an adjective in the sense of bloody or damned.

Con can be a noun — la frime, une escroquerie, or a verb — duper, escroquer.

- Pros and cons — le pour et le contre

Crayon vs Crayon

Un crayon is a pencil, while a crayon is as un crayon de couleur. The French language uses this expression for both crayon and colored pencil.

Déception vs Deception

Une déception is a disappointment or let-down, while a deception is une tromperie or duperie.

Demander vs Demand

Demander means to ask for:

- Il m’a demandé de chercher son pull — He asked me to look for his sweater

Note that the French noun une demande does correspond to the English noun demand. To demand is usually translated by exiger:

- He demanded that I look for his sweater — Il a exigé que je cherche son pull

Déranger vs Derange

Déranger can mean to derange (the mind), as well as to bother, disturb, or disrupt.

- Excusez-moi de vous déranger… — I’m sorry for bothering you….

To derange is used only when talking about mental health (usually as an adjective: deranged = dérangé).

Douche vs Douche

Une douche is a shower, while douche in English refers to a method of cleaning a body cavity with air or water: lavage interne.

Entrée vs Entrée

Une entrée is an hors-d’oeuvre or appetizer, while an entrée refers to the main course of a meal: le plat principal.

Envie vs Envy

Avoir envie de means to want or to feel like something:

- Je n’ai pas envie de travailler — I don’t want to work / I don’t feel like working

The verb envier, however, does mean to envy.

Envy means to be jealous or desirous of something belonging to another. The French verb is envier:

- I envy John’s courage — J’envie le courage à Jean

Éventuellement vs Eventually

Éventuellement means possibly, if need be, or even:

- Vous pouvez éventuellement prendre ma voiture — You can even take my car / You can take my car if need be.

Eventually indicates that an action will occur at a later time; it can be translated by finalement, à la longue, or tôt ou tard:

- I will eventually do it — Je le ferai finalement / tôt ou tard

Expérience vs Experience

Expérience is a semi-false cognate, because it means both experience and experiment:

- J’ai fait une expérience — I did an experiment

- J’ai eu une expérience intéressante — I had an interesting experience

Experience can be a noun or verb refering to something that happened. Only the noun translates into expérience:

- Experience shows that … — L’expérience démontre que…

- He experienced some difficulties — Il a rencontré des difficultés

Finalement vs Finally

Finalement means eventually or in the end, while finally is enfin or en dernier lieu.

Football vs Football

Le football, or le foot, refers to soccer (in American English). In the US, football = le football américain.

Formidable vs Formidable

Formidable is an interesting word because it means great or terrific; almost the opposite of the English.

- Ce film est formidable ! — This is a great movie!

Formidable in English means dreadful or fearsome:

- The opposition is formidable — L’opposition est redoutable/effrayante

Gentil vs Gentle

Gentil usually means nice or kind:

- Il a un gentil mot pour chacun — He has a kind word for everyone

It can also mean good, as in:

- il a été gentil — he was a good boy

Gentle can also mean kind but in the more physical sense of soft or not rough. It can be translated by doux, aimable, modéré, or léger:

- He is gentle with his hands — Il a la main douce

- A gentle breeze — une brise légère

Gratuité vs Gratuity

Gratuité refers to anything that is given for free:

- la gratuité de l’éducation — free education

while a gratuity is un pourboire or une gratification.

Gros vs Gross

Gros means big, fat, heavy, or serious:

- un gros problème — a big/serious problem

Gross means grossier, fruste, or (informally) dégueullasse.

Ignorer vs Ignore

Ignorer is a semi-false cognate. It nearly always means to be ignorant or unaware of something:

- j’ignore tout de cette affaire — I know nothing about this business

To ignore means to deliberately not pay attention to someone or something. The usual translations are ne tenir aucun compte de, ne pas relever, and ne pas prêter attention à.

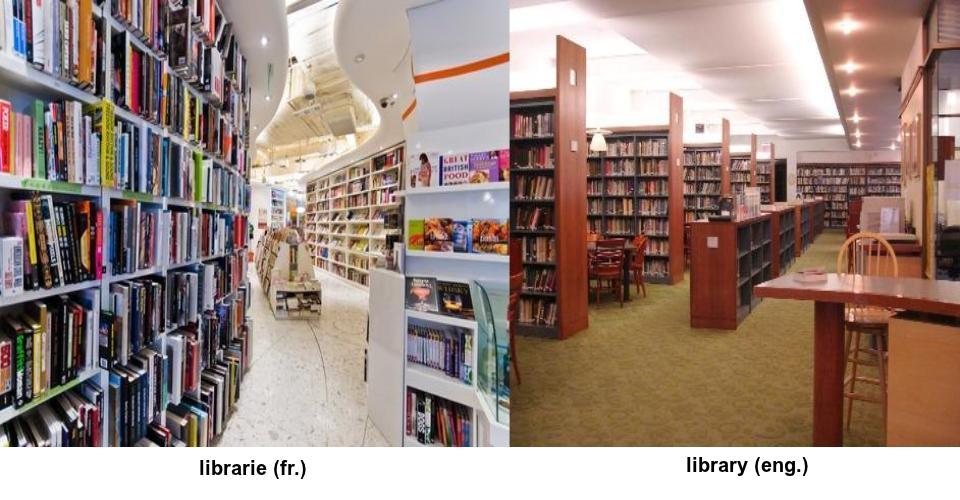

Librairie vs Library

Une librairie refers to a bookstore, while library in French is une bibliothèque.

Monnaie vs Money

La monnaie can refer to currency, coin(age), or change, and money is the general term for argent.

Napkin vs Napkin

Un napkin refers to a sanitary napkin. A napkin is correctly translated by une serviette.

Occasion vs Occasion

Occasion refers to a(n) occasion, circumstance, opportunity, or second-hand purchase.

- Une chemise d’occasion — a second-hand or used shirt.

Avoir l’occasion de means to have a/the chance to:

- Je n’avais pas l’occasion de lui parler — I didn’t have a chance to talk to him.

An occasion is une occasion, un événement, or un motif.

Opportunité vs Opportunity

Opportunité refers to timeliness or appropriateness:

- Nous discutons de l’opportunité d’aller à la plage — We’re discussing the appropriateness of going to the beach (under the circumstances).

Opportunity leans toward favorable circumstances for a particular action or event and is translated by une occasion:

- It’s an opportunity to improve your French — C’est une occasion de te perfectionner en français.

Parti/Partie vs Party

Un parti can refer to several different things: a political party, an option or course of action (prendre un parti — to make a decision), or a match (i.e., He’s a good match for you). It is also the past participle of partir (to leave).

Une partie can mean a part (e.g., une partie du film — a part of the film), a field or subject, a game (e.g., une partie de cartes — a game of cards), or a party in a trial.

A party usually refers to une fête, soirée, or réception; un correspondant (on the phone), or un groupe/une équipe.

Pièce vs Piece

Une pièce is a semi-false cognate. It means piece only in the sense of broken pieces. Otherwise, it indicates a room, sheet of paper, coin, or play.

Piece is a part of something — un morceau or une tranche.

Professeur vs Professor

Un professeur refers to a high school, college, or university teacher or instructor, while a professor is un professeur titulaire d’une chaire.

Publicité vs Publicity

Publicité is a semi-false cognate. In addition to publicity, une publicité can mean advertising in general, as well as a commercial or advertisement. Publicity is translated by de la publicité.

Quitter vs Quit

Quitter is a semi-false cognate: it means both to leave and to quit (i.e., leave something for good). When quit means to leave something for good, it is translated by quitter. When it means to quit (stop) doing something, it is translated by arrêter de:

- I need to quit smoking — Je dois arrêter de fumer.

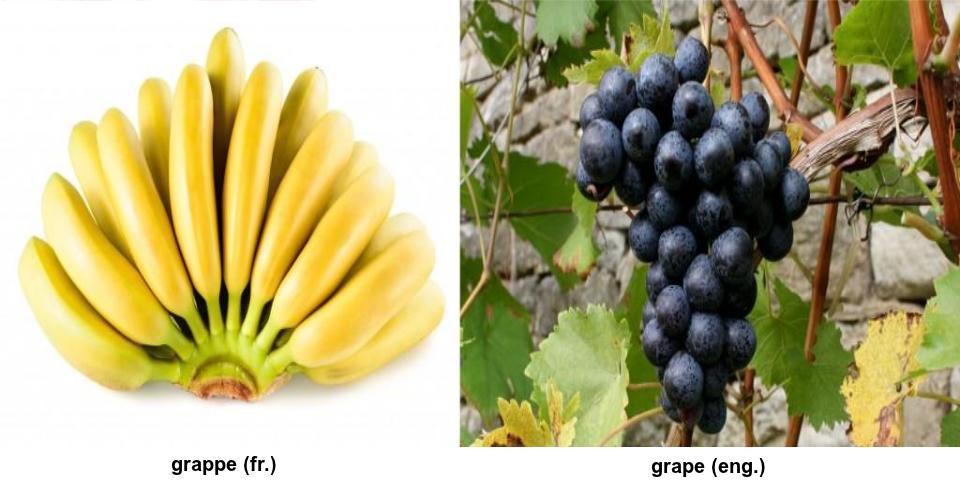

Raisin vs Raisin

Un raisin is a grape; a raisin is un raisin sec.

Rater vs Rate

Rater means to misfire, miss, mess up, or fail, while rate is the noun proportion or taux or the verb évaluer or considérer.

Réaliser vs Realize

Réaliser means to fulfill (a dream or aspiration) or achieve. To realize means se rendre compte de, prendre conscience de, or comprendre.

Rester vs Rest

Rester is a semi-false cognate. It usually means to stay or remain:

- Je suis restée à la maison — I stayed at the house

When it is used idiomatically, it is translated by rest:

- He refused to let the matter rest — Il refusait d’en rester là

The verb to rest in the sense of getting some rest is translated by se reposer:

- Elle ne se repose jamais — She never rests

Réunion vs Reunion

Une réunion can mean collection, gathering, raising (of money), or reunion. A reunion is une réunion, but note that it usually refers to a meeting of a group that has been separated for an extended period of time (e.g., class reunion, family reunion).

Robe vs Robe

Une robe is a dress, frock, or gown, while a robe is un peignoir.

Sale vs Sale

Sale is an adjective — dirty. Saler means to salt. A sale is une vente or un solde.

Sympathique vs Sympathetic

Sympathique (often shortened to sympa) means nice, likeable, friendly, kindly. Sympathetic can be translated by compatissant or de sympathie.

Type vs Type

Un type is informal for a guy or bloke. In the normal register, it can mean type, kind, or epitome.

- Quel type de moto ? — What kind of motorbike?

- Le type de l’égoïsme — The epitome of selfishness.

Type means un type, un genre, une espèce, une sorte, une marque, etc.

Unique vs Unique

The French word unique means only when it precedes a noun (unique fille — only girl) and unique or one of a kind when it follows. In English, unique means unique, inimitable, or exceptionnel.

Zone vs Zone

Une zone usually means a zone or an area, but it can also refer to a slum. A zone is une zone.

Have you ever trusted blindly and gotten stabbed in the back?

I’m not talking about people – I’m talking about French vocabulary.

French and English share a complicated linguistic history, leaving us to juggle loads of faux amis (false friends).

Long story short, you have to be careful out there.—but by learning these false cognates now you’ll save yourself from future confusion and embarrassment!

Contents

- What Are French False Friends (aka “Faux Amis”)?

- The Challenge of French False Cognates

- 20 Common French False Friends

-

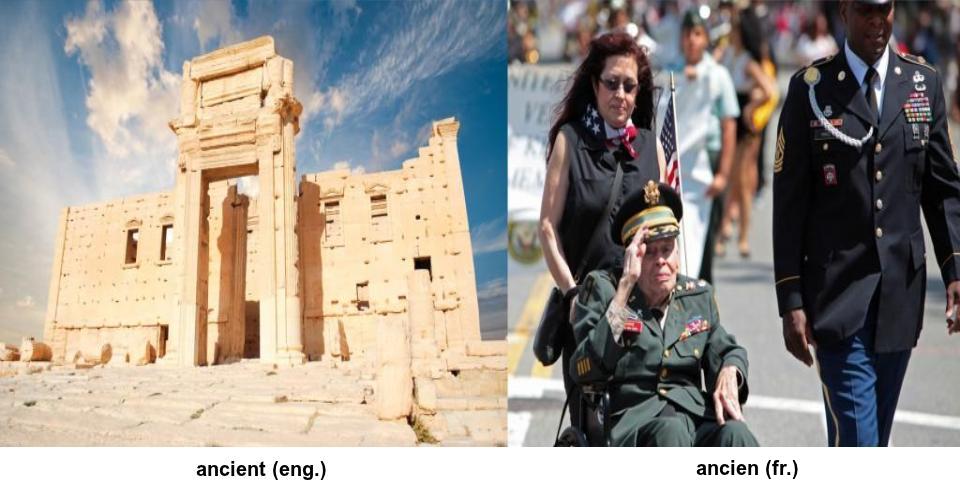

- 1. Ancien/Ancient

- 2. Attendre/Attend

- 3. Bras/Bras

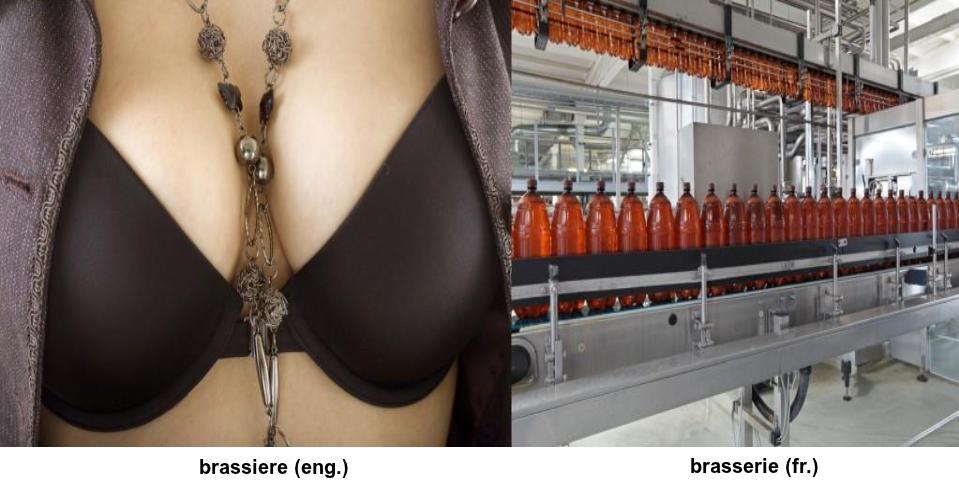

- 4. Brasserie/Brassiere

- 5. Blessé/Blessed

- 6. Bouton/Button

- 7. Monnaie/Money

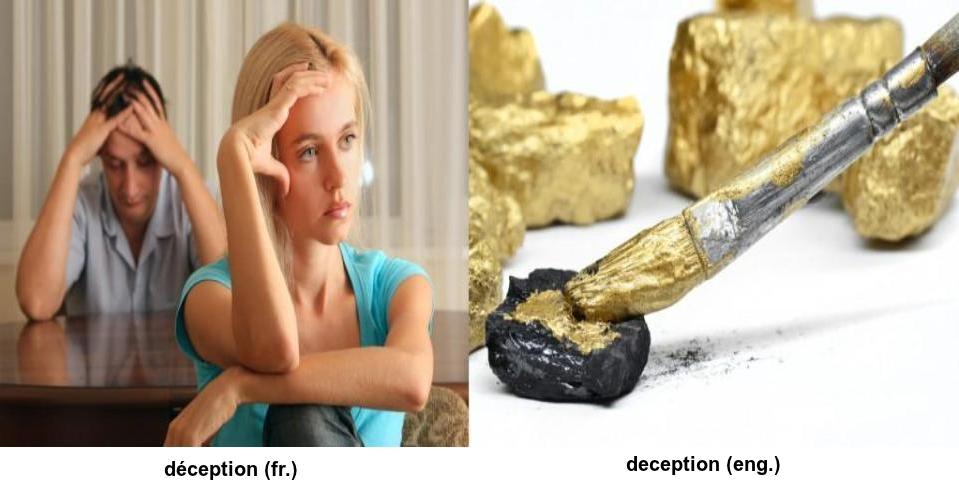

- 8. Déception/Deception

- 9. Envie/Envy

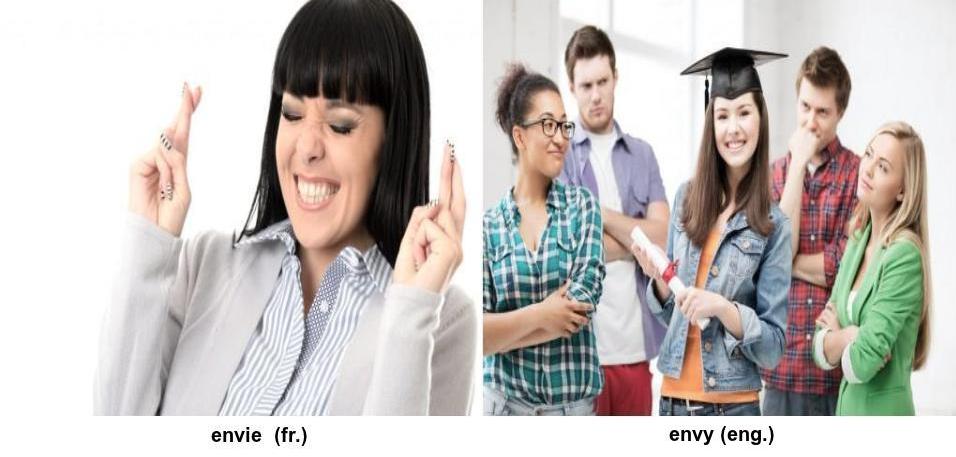

- 10. Grand/Grand

- 11. Grappe/Grape

- 12. Joli/Jolly

- 13. Journée/Journey

- 14. Librairie/Library

- 15. Location/Location

- 16. Coin/Coin

- 17. Passer/Pass

- 18. Préservatif/Preservative

- 19. Prune/Prune

- 20. Raisin/Raisin

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are French False Friends (aka “Faux Amis”)?

When French words look like English words, they really ought to mean the same thing, oughtn’t they? Often they do, fortunately, but some words don’t play fair. And those are the faux amis, which literally translates to “false friends.” These words can easily trick you into getting the wrong end of the stick, or to say something senseless or embarrassing that you hadn’t intended at all.

The Challenge of French False Cognates

False cognates are words that look identical in both languages but whose meanings differ. For the purposes of this blog, we’re also including “semi-false cognates” in our list of faux amis. Semi-false cognates are words that don’t look exactly the same, but they’re similar enough to invite confusion. An example of a French false cognate is the word grand. If you visit a grand city, you would expect to see impressive buildings since the English “grand” means it has a wow factor. But if you go to une grande ville expecting to be wowed, you’ll probably end up being disappointed instead. That’s because in French, the adjective grand(e) often simply means big. The town could be a dump, but if it’s big it could correctly be described as grande.

Semi-false cognates can set you up for disappointments too. For instance, you might fix up a blind date with une jolie fille, confidently looking forward to a fun evening with plenty of laughs. A jolly girl is sure to have a good sense of humor and be great company, even if she leaves something be desired in the looks department. But since the French adjective joli does not mean jolly, but rather means pretty, you could be wrong on both counts. She’ll be drop-dead gorgeous, but she might turn out to be as miserable as sin and not crack a smile all evening. The consequences of being led astray by a false friend can range from being left feeling slightly puzzled, to suffering acute embarrassment when you see, from the other person’s reaction, that you’ve said something rather shocking.

20 Common French False Friends

1. Ancien/Ancient

Ancien can mean ancient, but more often it means former. It’s important to know that un ancien combattant means an old soldier in the sense of a former soldier. It doesn’t mean that he’s as old as Methuselah. Similarly, the ancien maire of a commune is the former mayor, who might still be a young man; your ancienne voiture is the car you used to own; and l’ancienne gare describes the former station building, probably converted to another use such as a house, a shop, or a café. A good rule of thumb is that if ancien comes before the noun, it usually means former rather than ancient/old.

2. Attendre/Attend

Attendre means to wait for. Je t’attends is one of the little phrases that boyfriends and girlfriends often text to each other when they’re spending time apart. They’re really aying “I’m waiting for you,” and not “I’m attending to you.” If you’re planning on romancing someone in French you’ll need to know this distinction (and learning these French romance words too wouldn’t hurt!).

3. Bras/Bras

Votre bras means your arm, the limb between your shoulder and your wrist. It has no connection whatsoever with female undergarment. The French word for a bra is un soutien-gorge.

4. Brasserie/Brassiere

Again, no connection with lingerie. Une brasserie is either a brewery, or a bar that serves meals.

5. Blessé/Blessed

Blesser means to wound, either emotionally or physically. So un enfant blessé is not a child that you are expected to kneel down and worship, but more likely a child that needs patching up with an antiseptic wipe and a bandage.

6. Bouton/Button

Bouton does indeed mean button, but you might be mystified to hear French teenagers complaining about their boutons. They’re actually worrying about their complexions, since un bouton also means a pimple. Teenspeak can often be baffling to the uninitiated, but these 15 French slang words every French learner should know will help you keep up with le langage des ados (teen-speak).

7. Monnaie/Money

Monnaie means loose change. A person who gets to the checkout and says they have no monnaie is apologizing for not having the right change. You could easily have no monnaie, but plenty of money.

8. Déception/Deception

This is a sneaky faux ami. The verb decevoir, the noun déception, and the adjective déçu all have to do with being disappointed or disillusioned, and not actually deceived. This could lead to a fundamental misunderstanding if you think that somebody is accusing another person of deceiving them, rather than simply disappointing them.

9. Envie/Envy

You need to be careful with this one. The verb envier can be used in the sense of “to envy,” but the noun envie means wish or desire. You could say “J’ai envie d’une glace,” meaning “I want ice cream.” What you shouldn’t say is “J’ai envie de toi” if you mean “I envy you,” because what you would actually be saying is, “I want you.” Of course, if you listen to French pop music and watch French movies as part of your language learning strategy, you won’t fall into this trap because that particular phrase crops up very regularly whenever love and passion come into song lyrics or movie scripts.

10. Grand/Grand

Grand can mean great (un grand écrivain is a great writer), but it can also simply mean big. When used to describe a person’s physical appearance, it means tall.

11. Grappe/Grape

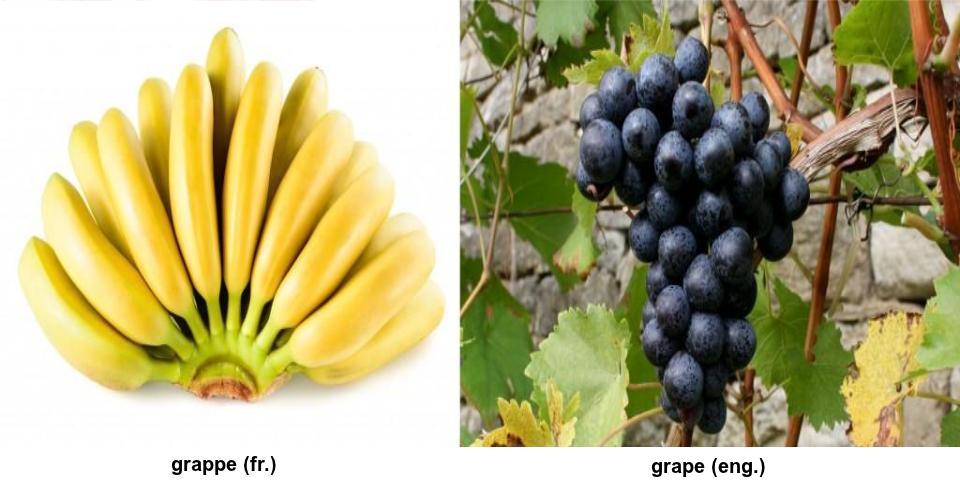

Une grappe de raisins does indeed mean a bunch of grapes, but don’t get confused; grappe means bunch. You can also have une grappe de bananes without a grape in sight.

12. Joli/Jolly

Joli(e) means pretty, and is used to describe objects as well as people.

13. Journée/Journey

This is a very common false friend. Une journée is a day, so if somebody wishes you “bonne journée,” they are saying “have a nice day.” It doesn’t mean they think you’re going off on a journey.

14. Librairie/Library

This is another – often confused – faux amis. There is a book connection, but une librairie is where you go to buy a book, not to borrow one. It means a bookshop or newsstand. If you want a library, it is une bibliothèque, or these days, it’s often part of la médiathèque. Keep these differences in mind while hunting down your next French book for your language learning routine!

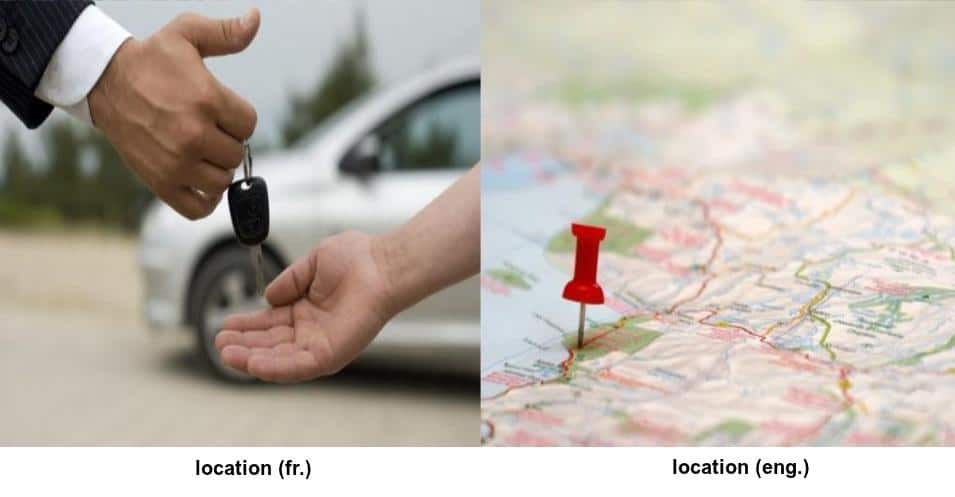

15. Location/Location

Location means rental. This can cause confusion because you often see advertisements describing “Les meilleures locations de vacances,” which looks as if it is saying “the best vacation locations.” It actually specifically means “the best holiday rentals,” so it’s all about accommodation for rent as opposed to places to visit.

16. Coin/Coin

Coin is the French word for corner. It has nothing whatsoever to do with the jingling money in your purse – those are pièces or monnaie. Dans le coin means in the immediate neighborhood, and “coin-coin” is what French ducks say instead of “quack quack”.

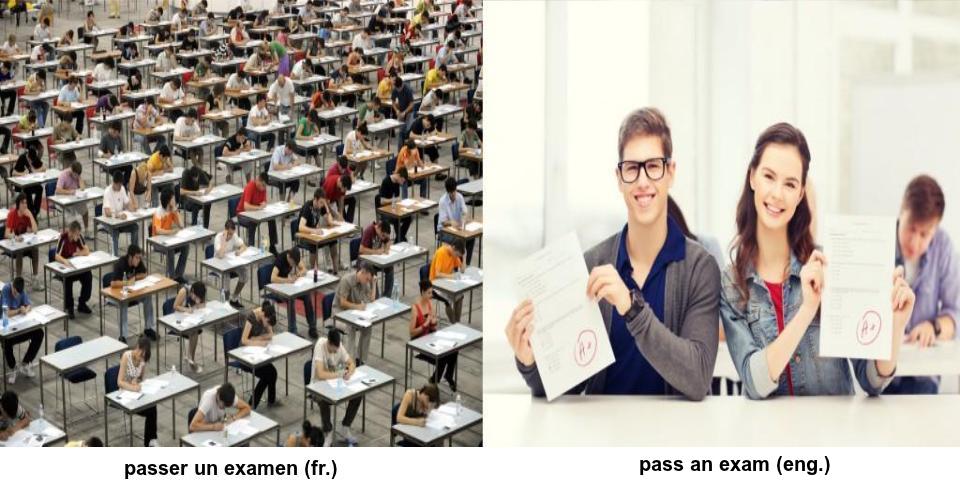

17. Passer/Pass

Passer un examen does not mean to pass an exam. Rather, it means to take an exam. So if a French friend who’s been learning to drive says “J’ai passé le code ce matin,” do not immediately start congratulating him or her on passing their driving test. You need to wait until they get their email or letter telling them the result before you start celebrating! To pass, in the English sense you’re probably more familiar with, is réussir.

18. Préservatif/Preservative

This one is possibly the most treacherous faux ami of all. Un préservatif is a condom. If you want a food preservative or wood preservative, do not ask for un préservatif!

19. Prune/Prune

You can’t trust words that describe fruits and their dried equivalents. Une prune is a plum. When you dry une prune to turn it into a prune, it becomes un pruneau.

20. Raisin/Raisin

Another tricky fruit to watch: un raisin is a grape. Raisins and sultanas are both called raisins secs, or dried grapes – which is logical because it’s what they are, but it does make for linguistic confusion.

French false friends can be a bit intimidating at first. However, making funny mistakes is just part of the learning process. Many of these silly slips ups tend to get a big laugh from native conversation partners. As you probably noticed, some mixed up words could cause a real scandal! The further you progress in your French language learning, the better you will come to know these common French false friends. Beware, though: there are plenty more out there!

The more you expose yourself to the French language, the more these faux amis will make themselves apparent—however, they’re not always immediately obvious unless you’re also able to see the English translation.

Resources which allow you to see both French and English are ideal for detecting them, such as books, audio transcripts and video subtitles that contain parallel text. On the video-based language learning program FluentU, authentic French video clips are paired with dual-language transcripts and interactive subtitles that make it easier to spot false friends and other language differences.

The best advice when learning French vocabulary is to not fret over possible mistakes – simply learn all you can, lighten up, and learn to laugh at yourself whenever this tricky language happens to trip you up!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Do you have any fake friends? In French, there are loads of them. Wait… what?

Let me explain: the English and the French have always had a complex relationship throughout history, and the same goes for their vocabulary! Faux amis (fake/false friends) are words that appear to mean the same in different languages but actually have completely different meanings.

Example: Un raisin (french) is not a raisin in English (it is actually a grape).

Because the words are identical looking, this can generate a lot of confusion for learners and creates some embarrassing situations during conversations. There are quite a few faux-amis (fake friends) in the French language, and you just have to learn to recognize them to avoid making mistakes.

They can be very misleading and deceptive.

Why are there so many faux amis in French?

The reason there are so many faux amis is that it’s estimated that 30% of the English vocabulary comes from the French language. How crazy is that!?

Becoming familiar with the French language as much as possible is the key to avoiding using faux amis. With Lingopie, you can practice your French by watching films, documentaries, series and more at your own pace. No matter what level you are at, you have the option of following along with the subtitles in both English and/or French.

Learning French from a textbook just isn’t enough if you want to become fluent. You need to expose yourself to the language by listening to it, as well as practicing speaking it. With Lingopie you have the option of practicing your pronunciation with the microphone tool. Your accuracy will be assessed so that you improve every time. Slowly you will build your vocabulary and you will find it easier to avoid using faux amis.

So,back to my original topic, here is a list of some of the most commonly made mistakes when it comes to faux amis in French:

What are the most common French faux amis?

1. Bras

What it looks like it means: a bra

What it really means: an arm

In French, the word ‘le bras’ means ‘arm’, rather than the female undergarment.

If you want to know the french word for bra it is ‘un soutien-gorge’. Remember this one because it can be awkward to get this muddled up in the middle of a conversation!

Here are some French expressions with the word ‘bras’:

‘Baisser les bras’. To give up

‘Rester les bras croisés’. To sit idly by/ to stand around doing absolutely nothing

2. Blessé

What it looks like it means: blessed

What it actually means: hurt, injured, wounded

‘Blessé’ means to be injured or wounded, rather than to be blessed (which is what it looks like it should be!). ‘Blessé’ comes from the verb ‘blesser’ which means to hurt somebody.

Example: L’accident a fait deux blessés. Two people were injured in the accident.

The actual word for ‘blessed’ in French is ‘béni(e)’.

3. Excité(e)

What it looks like it means: excited

What it actually means: horny/ sexually aroused

If you say ‘je suis excité(e)’ in French, you are not saying that you are excited, you are saying that you are horny! *major awks moment*. This is a very common mistake to make (Emily makes the same mistake in the Emily in Paris series!).

If you want to say you are excited for something, stick to ‘J’ai hâte de…’ or ‘Je suis impatient(e) de…’ or ‘il me tarde de…’

4. Actuellement

What it looks like it means: Actually

What it actually means: Currently/ now/ at the moment

This is a very easy word to misinterpret. ‘Actuellement’ means ‘currently’ or ‘now’. Here is an example of a phrase with actuellement:

‘Elle travaille actuellement en France’. She is now working in France.

If you want to say ‘actually’ in French, use ‘en fait’.

5. Journée

What it looks like it means: a journey

What it actually means: day/ daytime

This is another common mistake French learners make. ‘Journée’ means ‘day’ rather than ‘a journey’. Look at these examples:

Bonne journée: Have a good day

Il a plu toute la journée: It rained all day

The French word for journey is ‘voyage’ . This might be easy to remember because of the well-known expression ‘bon voyage’!

6. Raisin

What it looks like it means: a raisin

What it actually means: a grape

I used to get mixed up with this one a lot when I was learning French myself. ‘Un raisin’ is NOT ‘a raisin’ in English but rather ‘a grape’. (And technically raisins are dried grapes which makes it even more confusing! Eurgh!!)

For reference, the word for raisin in French is ‘raisins secs’ (plural).

7. Un Préservatif

What it looks like it means: a preservative

What it actually means: a condom

To avoid embarrassment, it’s best to really learn this one. ‘Un préservatif’ is a condom. Please try not to ask a waiter at a French restaurant if your food has any ‘préservatifs’. You will most likely get a weird look back, to say the least haha!

The word for preservatives is actually ‘conservateurs’.

8. Joli(e)

What it looks like it means: jolly/happy

What it actually means: pretty/ handsome/ nice/ lovely

Here’s another nasty faux ami. Contrary to popular belief ‘jolie(e)’ does not mean ‘jolly’, but rather ‘pretty’ or ‘nice’.

Here’s an example: Tu es une jolie fille. You are a pretty girl

The word for jolly in French is ‘gai(e)’.

9. Éventuellement

What it looks like it means: Eventually

What it actually means: Possibly, maybe, potentially

‘Éventuellement’ definitely looks like it should mean ‘eventually’ in English, but it actually means ‘possibly’.

Take a look at this sentence:

Je crains d’être éventuellement en retard. I’m afraid I’ll possibly be late.

The word for ‘eventually’ in French is ‘finalement’.

10. Sensible

What it looks like it means: Sensible

What it actually means: Sensitive

This is another false friend people often get muddled with. ‘Sensible’ means ‘sensitive’ in English.

Example: Elle est très sensible. She is very sensitive.

The word for ‘sensible’ in French is ‘raisonnable’. Look at this example:

Sois raisonnable! Be sensible!

11. Location

What it looks like it means: a location

What it actually means: rental, the rent

‘Location’ is another faux ami. It means ‘a rental’ rather than ‘a location’.

Look at these examples:

La location de voitures. Car rental

Location de skis. Ski hire/rental

If you want to say ‘a location’ in French, stick to ‘un lieu’ or ‘un endroit’

12. Librairie

What it looks like it means: a library

What it actually means: a bookshop

This is super confusing, I know! ‘Librairie’ does not translate as ‘library’ but rather as ‘bookshop’. So you cannot borrow a book from a ‘librairie’, but you can buy one.

The French word for ‘a library’ is ‘une bibliothèque’

13. Magasin

What it looks like it means: a magazine

What it actually means: a shop

When I was studying French this was the false friend that tripped me up the most. ‘Un magasin’ is a shop, not a magazine. Take a look at this example:

Les magasins ouvrent à 7h. The shops open at 7 o’clock.

The word for ‘magazine’ in French is the same as in English: ‘magazine’. (It still looks very similar to ‘magasin’ so take time to learn this one off by heart).

14. Rester

What it looks like it means: to rest

What it actually means: to stay/to remain

Another sneaky faux ami is ‘rester’. Most people assume it means ‘to rest’ but it actually means ‘to stay’.

Example: Je suis resté à la maison. I stayed at home.

The French word for to rest is ‘se reposer’.

15. Attendre

What it looks like it means: to attend

What it actually means: to wait for

Attendre does not mean to attend. It is the verb for to wait for somebody/ something. Look at this example:

J’attends ma sœur tous les jours à la même heure. I wait for my sister every day at the same time.

If you want to say the word attend in French, use ‘assister à’.

Summing up:

So, how many of these were you familiar with? As you can see, the French language is full of faux amis. They can be deceiving but you don’t have to let them trip you up. The more you familiarize yourself with French the less mistakes you are likely to make. You can start by learning this list of 15 French false friends.

But there are plenty more out there. Are you familiar with any others? As I mentioned before, listening to French as much as possible is key to avoiding mistakes.

Learning with Lingopie is such a useful way to keep up to date with the French that is used in daily life. You will also be immersing yourself in French culture whilst binge watching some shows. It’s a win-win situation!

Create an account today and start to excel in your French language learning. If you sign up today you get 70% off.

Bonne chance!