| French | |

|---|---|

| français | |

| Pronunciation | [fʁɑ̃sɛ] |

| Native to | France, Switzerland, Belgium, Canada, and other locations in the Francophonie |

| Speakers | Native: 80 million (2022)[1] Total (L1 + L2): 270 million (2022)[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Old Latin

|

|

Writing system |

Latin (French alphabet) French Braille |

|

Signed forms |

Signed French (français signé) |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

29 countries

10 subnational

Intergovernmental organizations

|

| Regulated by | Académie Française (French Academy) (France) Office québécois de la langue française (Quebec Board of the French Language) (Quebec) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | fr |

| ISO 639-2 | fre (B) fra (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | fra |

| Glottolog | stan1290 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-i |

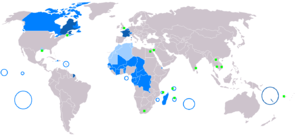

States where French is the majority native language States where it is an official or administrative language but not a majority native language States where it is a minority or secondary language |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

French (français [fʁɑ̃sɛ] or langue française [lɑ̃ɡ fʁɑ̃sɛz]) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Northern Gaul. Its closest relatives are the other langues d’oïl—languages historically spoken in northern France and in southern Belgium, which French (Francien) largely supplanted. French was also influenced by native Celtic languages of Northern Roman Gaul like Gallia Belgica and by the (Germanic) Frankish language of the post-Roman Frankish invaders. Today, owing to France’s past overseas expansion, there are numerous French-based creole languages, most notably Haitian Creole. A French-speaking person or nation may be referred to as Francophone in both English and French.

French is an official language in 29 countries across multiple continents,[2] most of which are members of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), the community of 84 countries which share the official use or teaching of French. French is also one of six official languages used in the United Nations.[3] It is spoken as a first language (in descending order of the number of speakers) in France; Canada (especially in the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, and New Brunswick, as well as other Francophone regions); Belgium (Wallonia and the Brussels-Capital Region); western Switzerland (specifically the cantons forming the Romandy region); parts of Luxembourg; parts of the United States (the states of Louisiana, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont); Monaco; the Aosta Valley region of Italy; and various communities elsewhere.[4]

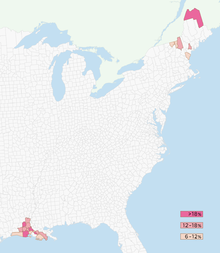

In 2015, approximately 40% of the francophone population (including L2 and partial speakers) lived in Europe, 36% in sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian Ocean, 15% in North Africa and the Middle East, 8% in the Americas, and 1% in Asia and Oceania.[5] French is the second-most widely spoken mother tongue in the European Union.[6] Of Europeans who speak other languages natively, approximately one-fifth are able to speak French as a second language.[7] French is the second-most taught foreign language in the EU. All institutions of the EU use French as a working language along with English and German; in certain institutions, French is the sole working language (e.g. at the Court of Justice of the European Union).[8] French is also the 18th most natively spoken language in the world, fifth most spoken language by total number of speakers and the second or third most studied language worldwide (with about 120 million learners as of 2017).[9] As a result of French and Belgian colonialism from the 16th century onward, French was introduced to new territories in the Americas, Africa and Asia. Most second-language speakers reside in Francophone Africa, in particular Gabon, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Mauritius, Senegal and Ivory Coast.[10]

French is estimated to have about 76 million native speakers; about 235 million daily, fluent speakers;[11][1][12] and another 77–110 million secondary speakers who speak it as a second language to varying degrees of proficiency, mainly in Africa.[13] According to the OIF, approximately 321 million people worldwide are «able to speak the language»,[14] without specifying the criteria for this estimation or whom it encompasses.[15] According to a demographic projection led by the Université Laval and the Réseau Démographie de l’Agence universitaire de la Francophonie, the total number of French speakers will reach approximately 500 million in 2025 and 650 million by 2050.[16] OIF estimates 700 million by 2050, 80% of whom will be in Africa.[5]

French has a long history as an international language of literature and scientific standards and is a primary or second language of many international organisations including the United Nations, the European Union, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the World Trade Organization, the International Olympic Committee, and the International Committee of the Red Cross. In 2011, Bloomberg Businessweek ranked French the third most useful language for business, after English and Standard Mandarin Chinese.[17]

History

French is a Romance language (meaning that it is descended primarily from Vulgar Latin) that evolved out of the Gallo-Romance dialects spoken in northern France. The language’s early forms include Old French and Middle French.

Vulgar Latin in Gaul

Due to Roman rule, Latin was gradually adopted by the inhabitants of Gaul, and as the language was learned by the common people it developed a distinct local character, with grammatical differences from Latin as spoken elsewhere, some of which being attested on graffiti.[18] This local variety evolved into the Gallo-Romance tongues, which include French and its closest relatives, such as Arpitan.

The evolution of Latin in Gaul was shaped by its coexistence for over half a millennium beside the native Celtic Gaulish language, which did not go extinct until the late sixth century, long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[19] The population remained 90% indigenous in origin;[20][21] the Romanizing class were the local native elite (not Roman settlers), whose children learned Latin in Roman schools. At the time of the collapse of the Empire, this local elite had been slowly abandoning Gaulish entirely, but the rural and lower class populations remained Gaulish speakers who could sometimes also speak Latin or Greek.[22] The final language shift from Gaulish to Vulgar Latin among rural and lower class populations occurred later, when both they and the incoming Frankish ruler/military class adopted the Gallo-Roman Vulgar Latin speech of the urban intellectual elite.[22]

The Gaulish language likely survived into the sixth century in France despite considerable Romanization.[19] Coexisting with Latin, Gaulish helped shape the Vulgar Latin dialects that developed into French[22][19] contributing loanwords and calques (including oui,[23] the word for «yes»),[24] sound changes shaped by Gaulish influence,[25][26][27] and influences in conjugation and word order.[24][28][18] Recent computational studies suggest that early gender shifts may have been motivated by the gender of the corresponding word in Gaulish.[29]

The estimated number of French words that can be attributed to Gaulish is placed at 154 by the Petit Robert,[30] which is often viewed as representing standardized French, while if non-standard dialects are included, the number increases to 240.[31] Known Gaulish loans are skewed toward certain semantic fields, such as plant life (chêne, bille, etc.), animals (mouton, cheval, etc.), nature (boue, etc.), domestic activities (ex. berceau), farming and rural units of measure (arpent, lieue, borne, boisseau), weapons,[32] and products traded regionally rather than further afield.[33] This semantic distribution has been attributed to peasants being the last to hold onto Gaulish.[33][32]

Old French

The beginning of French in Gaul was greatly influenced by Germanic invasions into the country. These invasions had the greatest impact on the northern part of the country and on the language there.[34] A language divide began to grow across the country. The population in the north spoke langue d’oïl while the population in the south spoke langue d’oc.[34] Langue d’oïl grew into what is known as Old French. The period of Old French spanned between the 8th and 14th centuries. Old French shared many characteristics with Latin. For example, Old French made use of different possible word orders just as Latin did because it had a case system that retained the difference between nominative subjects and oblique non-subjects.[35] The period is marked by a heavy superstrate influence from the Germanic Frankish language, which non-exhaustively included the use in upper-class speech and higher registers of V2 word order,[36] a large percentage of the vocabulary (now at around 15% of modern French vocabulary[37]) including the impersonal singular pronoun on (a calque of Germanic man), and the name of the language itself.

Up until its later stages, Old French, alongside Old Occitan, maintained a relic of the old nominal case system of Latin longer than most other Romance languages (with the notable exception of Romanian which still currently maintains a case distinction), differentiating between an oblique case and a nominative case. The phonology was characterized by heavy syllabic stress, which led to the emergence of various complicated diphthongs such as -eau which would later be leveled to monophthongs.[citation needed]

The earliest evidence of what became Old French can be seen in the Oaths of Strasbourg and the Sequence of Saint Eulalia, while Old French literature began to be produced in the eleventh century, with major early works often focusing on the lives of saints (such as the Vie de Saint Alexis), or wars and royal courts, notably including the Chanson de Roland, epic cycles focused on King Arthur and his court, as well as a cycle focused on William of Orange.[citation needed]

Middle French

Within Old French many dialects emerged but the Francien dialect is one that not only continued but also thrived during the Middle French period (14th–17th centuries).[34] Modern French grew out of this Francien dialect.[34] Grammatically, during the period of Middle French, noun declensions were lost and there began to be standardized rules. Robert Estienne published the first Latin-French dictionary, which included information about phonetics, etymology, and grammar.[38] Politically, the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (1539) named French the language of law.

Modern French

During the 17th century, French replaced Latin as the most important language of diplomacy and international relations (lingua franca). It retained this role until approximately the middle of the 20th century, when it was replaced by English as the United States became the dominant global power following the Second World War.[39][40] Stanley Meisler of the Los Angeles Times said that the fact that the Treaty of Versailles was written in English as well as French was the «first diplomatic blow» against the language.[41]

During the Grand Siècle (17th century), France, under the rule of powerful leaders such as Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIV, enjoyed a period of prosperity and prominence among European nations. Richelieu established the Académie Française to protect the French language. By the early 1800s, Parisian French had become the primary language of the aristocracy in France.

Near the beginning of the 19th century, the French government began to pursue policies with the end goal of eradicating the many minorities and regional languages (patois) spoken in France. This began in 1794 with Henri Grégoire’s «Report on the necessity and means to annihilate the patois and to universalize the use of the French language». When public education was made compulsory, only French was taught and the use of any other (patois) language was punished. The goals of the public school system were made especially clear to the French-speaking teachers sent to teach students in regions such as Occitania and Brittany. Instructions given by a French official to teachers in the department of Finistère, in western Brittany, included the following: «And remember, Gents: you were given your position in order to kill the Breton language».[42] The prefect of Basses-Pyrénées in the French Basque Country wrote in 1846: «Our schools in the Basque Country are particularly meant to replace the Basque language with French…»[42] Students were taught that their ancestral languages were inferior and they should be ashamed of them; this process was known in the Occitan-speaking region as Vergonha.

Geographic distribution

Europe

Spoken by 19.71% of the European Union’s population, French is the third most widely spoken language in the EU, after English and German and the second-most-widely taught language after English.[6][44]

Under the Constitution of France, French has been the official language of the Republic since 1992,[45] although the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts made it mandatory for legal documents in 1539. France mandates the use of French in official government publications, public education except in specific cases, and legal contracts; advertisements must bear a translation of foreign words.

In Belgium, French is an official language at the federal level along with Dutch and German. At the regional level, French is the sole official language of Wallonia (excluding a part of the East Cantons, which are German-speaking) and one of the two official languages—along with Dutch—of the Brussels-Capital Region, where it is spoken by the majority of the population (approx. 80%), often as their primary language.[46]

French is one of the four official languages of Switzerland, along with German, Italian, and Romansh, and is spoken in the western part of Switzerland, called Romandy, of which Geneva is the largest city. The language divisions in Switzerland do not coincide with political subdivisions, and some cantons have bilingual status: for example, cities such as Biel/Bienne and cantons such as Valais, Fribourg and Berne. French is the native language of about 23% of the Swiss population, and is spoken by 50%[47] of the population.

Along with Luxembourgish and German, French is one of the three official languages of Luxembourg, where it is generally the preferred language of business as well as of the different public administrations. It is also the official language of Monaco.

At a regional level, French is acknowledged as an official language in the Aosta Valley region of Italy where it is the first language of approximately 30% of the population, while French dialects remain spoken by minorities on the Channel Islands. It is also spoken in Andorra and is the main language after Catalan in El Pas de la Casa. The language is taught as the primary second language in the German state of Saarland, with French being taught from pre-school and over 43% of citizens being able to speak French.[48][49]

Distribution of native French speakers in 6 countries in 2021

Africa

Countries usually considered part of Francophone Africa

Their population was 442.1 million in 2020,[50] and it is forecast to reach between 845 million[51] and 891 million[52] in 2050.

Countries sometimes considered as Francophone Africa

Countries that are not Francophone but are Members or Observers of the OIF

The majority of the world’s French-speaking population lives in Africa. According to a 2018 estimate from the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, an estimated 141 million African people spread across 34 countries and territories[Note 1] can speak French as either a first or a second language.[53][54] This number does not include the people living in non-Francophone African countries who have learned French as a foreign language. Due to the rise of French in Africa, the total French-speaking population worldwide is expected to reach 700 million people in 2050.[55] French is the fastest growing language on the continent (in terms of either official or foreign languages).[56][57]

French is mostly a second language in Africa, but it has become a first language in some urban areas, such as the region of Abidjan, Ivory Coast[58] and in Libreville, Gabon.[59] There is not a single African French, but multiple forms that diverged through contact with various indigenous African languages.[60]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region where the French language is most likely to expand, because of the expansion of education and rapid population growth.[61] It is also where the language has evolved the most in recent years.[62][63] Some vernacular forms of French in Africa can be difficult to understand for French speakers from other countries,[64] but written forms of the language are very closely related to those of the rest of the French-speaking world.

Americas

Canada

French language distribution in Canada

Regions where French is the main language

Regions where French is an official language but not a majority native language

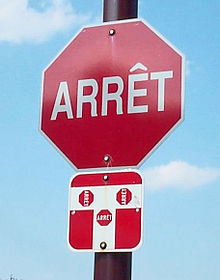

The «arrêt» signs (French for «stop») are used in Canada while the English stop, which is also a valid French word, is used in France and other French-speaking countries and regions.

French is the second-most common language in Canada, after English, and both are official languages at the federal level. It is the first language of 9.5 million people or 29% and the second language for 2.07 million or 6% of the entire population of Canada.[12] French is the sole official language in the province of Quebec, being the mother tongue for some 7 million people, or almost 80% (2006 Census) of the province[citation needed]. About 95% of the people of Quebec speak French as either their first or second language, and for some as their third language. Quebec is also home to the city of Montreal, which is the world’s fourth-largest French-speaking city, by number of first language speakers.[65][citation needed] New Brunswick and Manitoba are the only officially bilingual provinces, though full bilingualism is enacted only in New Brunswick, where about one third of the population is Francophone. French is also an official language of all of the territories (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon). Out of the three, Yukon has the most French speakers, making up just under 4% of the population.[66] Furthermore, while French is not an official language in Ontario, the French Language Services Act ensures that provincial services are to be available in the language. The Act applies to areas of the province where there are significant Francophone communities, namely Eastern Ontario and Northern Ontario. Elsewhere, sizable French-speaking minorities are found in southern Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and the Port au Port Peninsula in Newfoundland and Labrador, where the unique Newfoundland French dialect was historically spoken. Smaller pockets of French speakers exist in all other provinces. The Ontarian city of Ottawa, the Canadian capital, is also effectively bilingual, as it has a large population of federal government workers, who are required to offer services in both French and English, and is across a river from Quebec, opposite the major city of Gatineau with which it forms a single metropolitan area.[citation needed]

United States

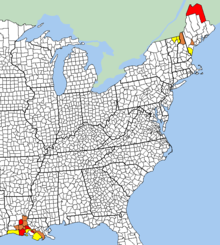

French language spread in the United States. Counties marked in lighter pink are those where 6–12% of the population speaks French at home; medium pink, 12–18%; darker pink, over 18%. French-based creole languages are not included.

According to the United States Census Bureau (2011), French is the fourth[67] most spoken language in the United States after English, Spanish, and Chinese, when all forms of French are considered together and all dialects of Chinese are similarly combined. French is the second-most spoken language (after English) in the states of Maine and Vermont. In Louisiana, it is tied with Spanish for second-most spoken if Louisiana French and all creoles such as Haitian are included. French is the third most spoken language (after English and Spanish) in the states of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.[68] Louisiana is home to many distinct French dialects, collectively known as Louisiana French. New England French, essentially a variant of Canadian French, is spoken in parts of New England. Missouri French was historically spoken in Missouri and Illinois (formerly known as Upper Louisiana), but is nearly extinct today.[69] French also survived in isolated pockets along the Gulf Coast of what was previously French Lower Louisiana, such as Mon Louis Island, Alabama and DeLisle, Mississippi (the latter only being discovered by linguists in the 1990s) but these varieties are severely endangered or presumed extinct.

Caribbean

French is one of two official languages in Haiti alongside Haitian Creole. It is the principal language of education, administration, business, and public signage and is spoken by all educated Haitians. It is also used for ceremonial events such as weddings, graduations, and church masses. The vast majority of the population speaks Haitian Creole as their first language; the rest largely speak French as a first language.[70] As a French Creole language, Haitian Creole draws the large majority of its vocabulary from French, with influences from West African languages, as well as several European languages. It is closely related to Louisiana Creole and the creole from the Lesser Antilles.[71]

French is the sole official language of all the overseas territories of France in the Caribbean that are collectively referred to as the French West Indies, namely Guadeloupe, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, and Martinique.

Other territories

French is the official language of both French Guiana on the South American continent,[72] and of Saint Pierre and Miquelon,[73] an archipelago off the coast of Newfoundland in North America.

Asia

Southeast Asia

French was the official language of the colony of French Indochina, comprising modern-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. It continues to be an administrative language in Laos and Cambodia, although its influence has waned in recent decades.[74] In colonial Vietnam, the elites primarily spoke French, while many servants who worked in French households spoke a French pidgin known as «Tây Bồi» (now extinct). After French rule ended, South Vietnam continued to use French in administration, education, and trade.[75] However, since the Fall of Saigon and the opening of a unified Vietnam’s economy, French has gradually been effectively displaced as the first foreign language of choice by English in Vietnam. Nevertheless, it continues to be taught as the other main foreign language in the Vietnamese educational system and is regarded as a cultural language.[76]

All three countries are full members of La Francophonie (OIF).

India

French was the official language of French India, consisting of the geographically separate enclaves referred to as Puducherry. It continued to be an official language of the territory even after its cession to India in 1956 until 1965.[77] A small number of older locals still retain knowledge of the language, although it has now given way to Tamil and English.[77][78]

Western Asia

Lebanon

A former French mandate, Lebanon designates Arabic as the sole official language, while a special law regulates cases when French can be publicly used. Article 11 of Lebanon’s Constitution states that «Arabic is the official national language. A law determines the cases in which the French language is to be used».[79] The French language in Lebanon is a widespread second language among the Lebanese people, and is taught in many schools along with Arabic and English. French is used on Lebanese pound banknotes, on road signs, on Lebanese license plates, and on official buildings (alongside Arabic).

Today, French and English are secondary languages of Lebanon, with about 40% of the population being Francophone and 40% Anglophone.[80] The use of English is growing in the business and media environment. Out of about 900,000 students, about 500,000 are enrolled in Francophone schools, public or private, in which the teaching of mathematics and scientific subjects is provided in French.[81] Actual usage of French varies depending on the region and social status. One-third of high school students educated in French go on to pursue higher education in English-speaking institutions. English is the language of business and communication, with French being an element of social distinction, chosen for its emotional value.[82]

United Arab Emirates and Qatar

The UAE has the status in the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie as an observer state, and Qatar has the status in the organization as an associate state. However, in both countries, French is not spoken by almost any of the general population or migrant workers, but spoken by a small minority of those who invest in Francophone countries or have other financial or family ties. Their entrance as observer and associate states respectively into the organization was aided a good deal by their investments into the Organisation and France itself.[83] A country’s status as an observer state in the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie gives the country the right to send representatives to organization meetings and make formal requests to the organization but they do not have voting rights within the OIF.[84] A country’s status as an associate state also does not give a country voting abilities but associate states can discuss and review organization matters.[85]

Oceania and Australasia

French is an official language of the Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu, where 31% of the population was estimated to speak it in 2018.[53] In the French special collectivity of New Caledonia, 97% of the population can speak, read and write French[86] while in French Polynesia this figure is 95%,[87] and in the French collectivity of Wallis and Futuna, it is 84%.[88]

In French Polynesia and to a lesser extent Wallis and Futuna, where oral and written knowledge of the French language has become almost universal (95% and 84% respectively), French increasingly tends to displace the native Polynesian languages as the language most spoken at home. In French Polynesia, the percentage of the population who reported that French was the language they use the most at home rose from 67% at the 2007 census to 74% at the 2017 census.[89][87] In Wallis and Futuna, the percentage of the population who reported that French was the language they use the most at home rose from 10% at the 2008 census to 13% at the 2018 census.[88][90]

Future

The future of the French language is often discussed in the news. For example, in 2014, The New York Times documented an increase in the teaching of French in New York, especially in K-12 dual-language programs where Spanish and Mandarin are the only second-language options more popular than French.[91] In a study published in March 2014 by Forbes, the investment bank Natixis said that French could become the world’s most spoken language by 2050. It noted that French is spreading in areas where the population is rapidly increasing, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.[92]

In the European Union, French was the dominant language within all institutions until the 1990s. After several enlargements of the EU (1995, 2004), French significantly lost ground in favour of English, which is more widely spoken and taught in most EU countries. French currently remains one of the three working languages, or «procedural languages», of the EU, along with English and German. It is the second-most widely used language within EU institutions after English, but remains the preferred language of certain institutions or administrations such as the Court of Justice of the European Union, where it is the sole internal working language, or the Directorate-General for Agriculture. Since 2016, Brexit has rekindled discussions on whether or not French should again hold greater role within the institutions of the European Union.[93]

Varieties

- African French

- Maghreb French (North African French)

- Aostan French

- Belgian French

- Cambodian French

- Canadian French

- Acadian French

- Newfoundland French

- New England French

- Ontario French

- Quebec French

- French French

- Guianese French

- Meridional French

- Haitian French

- Indian French

- Jersey Legal French

- Lao French

- Louisiana French

- Cajun French

- Missouri French

- South East Asian French

- Swiss French

- Vietnamese French

- West Indian French

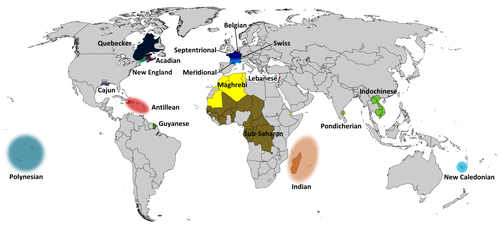

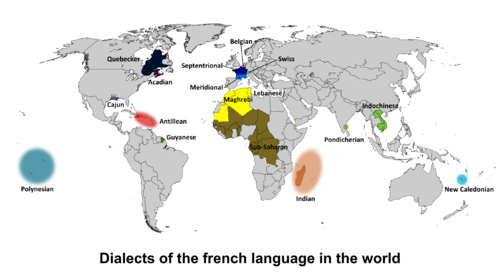

Varieties of the French language in the world

Current status and importance

A leading world language, French is taught in universities around the world, and is one of the world’s most influential languages because of its wide use in the worlds of journalism, jurisprudence, education, and diplomacy.[94]

In diplomacy, French is one of the six official languages of the United Nations (and one of the UN Secretariat’s only two working languages[95]), one of twenty official and three procedural languages of the European Union, an official language of NATO, the International Olympic Committee, the Council of Europe, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Organization of American States (alongside Spanish, Portuguese and English), the Eurovision Song Contest, one of eighteen official languages of the European Space Agency, World Trade Organization and the least used of the three official languages in the North American Free Trade Agreement countries. It is also a working language in nonprofit organisations such as the Red Cross (alongside English, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic and Russian), Amnesty International (alongside 32 other languages of which English is the most used, followed by Spanish, Portuguese, German, and Italian), Médecins sans Frontières (used alongside English, Spanish, Portuguese and Arabic), and Médecins du Monde (used alongside English).[96] Given the demographic prospects of the French-speaking nations of Africa, researcher Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry wrote in 2014 that French «could be the language of the future».[97]

Significant as a judicial language, French is one of the official languages of such major international and regional courts, tribunals, and dispute-settlement bodies as the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the Caribbean Court of Justice, the Court of Justice for the Economic Community of West African States, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea the International Criminal Court and the World Trade Organization Appellate Body. It is the sole internal working language of the Court of Justice of the European Union, and makes with English the European Court of Human Rights’s two working languages.[98]

In 1997, George Weber published, in Language Today, a comprehensive academic study entitled «The World’s 10 most influential languages».[99] In the article, Weber ranked French as, after English, the second-most influential language of the world, ahead of Spanish.[99] His criteria were the numbers of native speakers, the number of secondary speakers (especially high for French among fellow world languages), the number of countries using the language and their respective populations, the economic power of the countries using the language, the number of major areas in which the language is used, and the linguistic prestige associated with the mastery of the language (Weber highlighted that French in particular enjoys considerable linguistic prestige).[99] In a 2008 reassessment of his article, Weber concluded that his findings were still correct since «the situation among the top ten remains unchanged.»[99]

Knowledge of French is often considered to be a useful skill by business owners in the United Kingdom; a 2014 study found that 50% of British managers considered French to be a valuable asset for their business, thus ranking French as the most sought-after foreign language there, ahead of German (49%) and Spanish (44%).[100] MIT economist Albert Saiz calculated a 2.3% premium for those who have French as a foreign language in the workplace.[101]

In English-speaking Canada, the United Kingdom, and Ireland, French is the first foreign language taught and in number of pupils is far ahead of other languages. In the United States, French is the second-most commonly taught foreign language in schools and universities, although well behind Spanish. In some areas of the country near French-speaking Quebec, however, it is the foreign language more commonly taught.

Phonology

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal/ Postalveolar |

Velar/ Uvular |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ʁ |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ||

| Approximant | plain | l | j | ||

| labial | ɥ | w |

Vowel phonemes in French

|

|

Although there are many French regional accents, foreign learners normally use only one variety of the language.

- There are a maximum of 17 vowels in French, not all of which are used in every dialect: /a/, /ɑ/, /e/, /ɛ/, /ɛː/, /ə/, /i/, /o/, /ɔ/, /y/, /u/, /œ/, /ø/, plus the nasalized vowels /ɑ̃/, /ɛ̃/, /ɔ̃/ and /œ̃/. In France, the vowels /ɑ/, /ɛː/ and /œ̃/ are tending to be replaced by /a/, /ɛ/ and /ɛ̃/ in many people’s speech, but the distinction of /ɛ̃/ and /œ̃/ is present in Meridional French. In Quebec and Belgian French, the vowels /ɑ/, /ə/, /ɛː/ and /œ̃/ are present.

- Voiced stops (i.e., /b, d, ɡ/) are typically produced fully voiced throughout.

- Voiceless stops (i.e., /p, t, k/) are unaspirated.

- The velar nasal /ŋ/ can occur in final position in borrowed (usually English) words: parking, camping, swing. The palatal nasal /ɲ/ can occur in word initial position (e.g., gnon), but it is most frequently found in intervocalic, onset position or word-finally (e.g., montagne).

- French has three pairs of homorganic fricatives distinguished by voicing, i.e., labiodental /f/~/v/, dental /s/~/z/, and palato-alveolar /ʃ/~/ʒ/. /s/~/z/ are dental, like the plosives /t/~/d/ and the nasal /n/.

- French has one rhotic whose pronunciation varies considerably among speakers and phonetic contexts. In general, it is described as a voiced uvular fricative, as in [ʁu] roue, «wheel». Vowels are often lengthened before this segment. It can be reduced to an approximant, particularly in final position (e.g., fort), or reduced to zero in some word-final positions. For other speakers, a uvular trill is also common, and an apical trill [r] occurs in some dialects.

- Lateral and central approximants: The lateral approximant /l/ is unvelarised in both onset (lire) and coda position (il). In the onset, the central approximants [w], [ɥ], and [j] each correspond to a high vowel, /u/, /y/, and /i/ respectively. There are a few minimal pairs where the approximant and corresponding vowel contrast, but there are also many cases where they are in free variation. Contrasts between /j/ and /i/ occur in final position as in /pɛj/ paye, «pay», vs. /pɛi/ pays, «country».

French pronunciation follows strict rules based on spelling, but French spelling is often based more on history than phonology. The rules for pronunciation vary between dialects, but the standard rules are:

- Final single consonants, in particular s, x, z, t, d, n, p and g, are normally silent. (A consonant is considered «final» when no vowel follows it even if one or more consonants follow it.) The final letters f, k, q, and l, however, are normally pronounced. The final c is sometimes pronounced like in bac, sac, roc but can also be silent like in blanc or estomac. The final r is usually silent when it follows an e in a word of two or more syllables, but it is pronounced in some words (hiver, super, cancer etc.).

- When the following word begins with a vowel, however, a silent consonant may once again be pronounced, to provide a liaison or «link» between the two words. Some liaisons are mandatory, for example the s in les amants or vous avez; some are optional, depending on dialect and register, for example, the first s in deux cents euros or euros irlandais; and some are forbidden, for example, the s in beaucoup d’hommes aiment. The t of et is never pronounced and the silent final consonant of a noun is only pronounced in the plural and in set phrases like pied-à-terre.

- Doubling a final n and adding a silent e at the end of a word (e.g., chien → chienne) makes it clearly pronounced. Doubling a final l and adding a silent e (e.g., gentil → gentille) adds a [j] sound if the l is preceded by the letter i.

- Some monosyllabic function words ending in a or e, such as je and que, drop their final vowel when placed before a word that begins with a vowel sound (thus avoiding a hiatus). The missing vowel is replaced by an apostrophe. (e.g., *je ai is instead pronounced and spelled → j’ai). This gives, for example, the same pronunciation for l’homme qu’il a vu («the man whom he saw») and l’homme qui l’a vu («the man who saw him»). However, for Belgian French the sentences are pronounced differently; in the first sentence the syllable break is as «qu’il-a», while the second breaks as «qui-l’a». It can also be noted that, in Quebec French, the second example (l’homme qui l’a vu) is more emphasized on l’a vu.

Writing system

Alphabet

French is written with the 26 letters of the basic Latin script, with four diacritics appearing on vowels (circumflex accent, acute accent, grave accent, diaeresis) and the cedilla appearing in «ç».

There are two ligatures, «œ» and «æ», but they are often replaced in contemporary French with «oe» and «ae», because the ligatures do not appear on the AZERTY keyboard layout used in French-speaking countries. However this is nonstandard in formal and literary texts.

Orthography

French spelling, like English spelling, tends to preserve obsolete pronunciation rules. This is mainly due to extreme phonetic changes since the Old French period, without a corresponding change in spelling. Moreover, some conscious changes were made to restore Latin orthography (as with some English words such as «debt»):

- Old French doit > French doigt «finger» (Latin digitus)

- Old French pie > French pied «foot» [Latin pes (stem: ped-)]

French orthography is morphophonemic. While it contains 130 graphemes that denote only 36 phonemes, many of its spelling rules are likely due to a consistency in morphemic patterns such as adding suffixes and prefixes.[102] Many given spellings of common morphemes usually lead to a predictable sound. In particular, a given vowel combination or diacritic generally leads to one phoneme. However, there is not a one-to-one relation of a phoneme and a single related grapheme, which can be seen in how tomber and tombé both end with the /e/ phoneme.[103] Additionally, there are many variations in the pronunciation of consonants at the end of words, demonstrated by how the x in paix is not pronounced though at the end of Aix it is.

As a result, it can be difficult to predict the spelling of a word based on the sound. Final consonants are generally silent, except when the following word begins with a vowel (see Liaison (French)). For example, the following words end in a vowel sound: pied, aller, les, finit, beaux. The same words followed by a vowel, however, may sound the consonants, as they do in these examples: beaux-arts, les amis, pied-à-terre.

French writing, as with any language, is affected by the spoken language. In Old French, the plural for animal was animals. The /als/ sequence was unstable and was turned into a diphthong /aus/. This change was then reflected in the orthography: animaus. The us ending, very common in Latin, was then abbreviated by copyists (monks) by the letter x, resulting in a written form animax. As the French language further evolved, the pronunciation of au turned into /o/ so that the u was reestablished in orthography for consistency, resulting in modern French animaux (pronounced first /animos/ before the final /s/ was dropped in contemporary French). The same is true for cheval pluralized as chevaux and many others. In addition, castel pl. castels became château pl. châteaux.

- Nasal: n and m. When n or m follows a vowel or diphthong, the n or m becomes silent and causes the preceding vowel to become nasalized (i.e., pronounced with the soft palate extended downward so as to allow part of the air to leave through the nostrils). Exceptions are when the n or m is doubled, or immediately followed by a vowel. The prefixes en- and em- are always nasalized. The rules are more complex than this but may vary between dialects.

- Digraphs: French uses not only diacritics to specify its large range of vowel sounds and diphthongs, but also specific combinations of vowels, sometimes with following consonants, to show which sound is intended.

- Gemination: Within words, double consonants are generally not pronounced as geminates in modern French (but geminates can be heard in the cinema or TV news from as recently as the 1970s, and in very refined elocution they may still occur). For example, illusion is pronounced [ilyzjɔ̃] and not [ilːyzjɔ̃]. However, gemination does occur between words; for example, une info («a news item» or «a piece of information») is pronounced [ynɛ̃fo], whereas une nympho («a nymphomaniac») is pronounced [ynːɛ̃fo].

- Accents are used sometimes for pronunciation, sometimes to distinguish similar words, and sometimes based on etymology alone.

- Accents that affect pronunciation

- The acute accent (l’accent aigu) é (e.g., école—school) means that the vowel is pronounced /e/ instead of the default /ə/.

- The grave accent (l’accent grave) è (e.g., élève—pupil) means that the vowel is pronounced /ɛ/ instead of the default /ə/.

- The circumflex (l’accent circonflexe) ê (e.g. forêt—forest) shows that an e is pronounced /ɛ/ and that an ô is pronounced /o/. In standard French, it also signifies a pronunciation of /ɑ/ for the letter â, but this differentiation is disappearing. In the mid-18th century, the circumflex was used in place of s after a vowel, where that letter s was not pronounced. Thus, forest became forêt, hospital became hôpital, and hostel became hôtel.

- Diaeresis or tréma (ë, ï, ü, ÿ): over e, i, u or y, indicates that a vowel is to be pronounced separately from the preceding one: naïve, Noël.

- The combination of e with diaeresis following o (Noël [ɔɛ]) is nasalized in the regular way if followed by n (Samoëns [wɛ̃])

- The combination of e with diaeresis following a is either pronounced [ɛ] (Raphaël, Israël [aɛ]) or not pronounced, leaving only the a (Staël [a]) and the a is nasalized in the regular way if aë is followed by n (Saint-Saëns [ɑ̃])

- A diaeresis on y only occurs in some proper names and in modern editions of old French texts. Some proper names in which ÿ appears include Aÿ (a commune in Marne, formerly Aÿ-Champagne), Rue des Cloÿs (an alley in Paris), Croÿ (family name and hotel on the Boulevard Raspail, Paris), Château du Faÿ [fr] (near Pontoise), Ghÿs (name of Flemish origin spelt Ghijs where ij in handwriting looked like ÿ to French clerks), L’Haÿ-les-Roses (commune near Paris), Pierre Louÿs (author), Moÿ-de-l’Aisne (commune in Aisne and a family name), and Le Blanc de Nicolaÿ (an insurance company in eastern France).

- The diaeresis on u appears in the Biblical proper names Archélaüs, Capharnaüm, Emmaüs, Ésaü, and Saül, as well as French names such as Haüy. Nevertheless, since the 1990 orthographic changes, the diaeresis in words containing guë (such as aiguë or ciguë) may be moved onto the u: aigüe, cigüe, and by analogy may be used in verbs such as j’argüe.

- In addition, words coming from German retain their umlaut (ä, ö and ü) if applicable but use often French pronunciation, such as Kärcher (trademark of a pressure washer).

- The cedilla (la cédille) ç (e.g., garçon—boy) means that the letter ç is pronounced /s/ in front of the back vowels a, o and u (c is otherwise /k/ before a back vowel). C is always pronounced /s/ in front of the front vowels e, i, and y, thus ç is never found in front of front vowels.

- Accents with no pronunciation effect

- The circumflex does not affect the pronunciation of the letters i or u, nor, in most dialects, a. It usually indicates that an s came after it long ago, as in île (from former isle, compare with English word «isle»). The explanation is that some words share the same orthography, so the circumflex is put here to mark the difference between the two words. For example, dites (you say) / dîtes (you said), or even du (of the) / dû (past participle for the verb devoir = must, have to, owe; in this case, the circumflex disappears in the plural and the feminine).

- All other accents are used only to distinguish similar words, as in the case of distinguishing the adverbs là and où («there», «where») from the article la («the» feminine singular) and the conjunction ou («or»), respectively.

- Accents that affect pronunciation

Some proposals exist to simplify the existing writing system, but they still fail to gather interest.[104][105][106][107]

In 1990, a reform accepted some changes to French orthography. At the time the proposed changes were considered to be suggestions. In 2016, schoolbooks in France began to use the newer recommended spellings, with instruction to teachers that both old and new spellings be deemed correct.[108]

Grammar

French is a moderately inflected language. Nouns and most pronouns are inflected for number (singular or plural, though in most nouns the plural is pronounced the same as the singular even if spelled differently); adjectives, for number and gender (masculine or feminine) of their nouns; personal pronouns and a few other pronouns, for person, number, gender, and case; and verbs, for tense, aspect, mood, and the person and number of their subjects. Case is primarily marked using word order and prepositions, while certain verb features are marked using auxiliary verbs. According to the French lexicogrammatical system, French has a rank-scale hierarchy with clause as the top rank, which is followed by group rank, word rank, and morpheme rank. A French clause is made up of groups, groups are made up of words, and lastly, words are made up of morphemes.[109]

French grammar shares several notable features with most other Romance languages, including

- the loss of Latin declensions

- the loss of the neuter gender

- the development of grammatical articles from Latin demonstratives

- the loss of certain Latin tenses and the creation of new tenses from auxiliaries.

Nouns

Every French noun is either masculine or feminine. Because French nouns are not inflected for gender, a noun’s form cannot specify its gender. For nouns regarding the living, their grammatical genders often correspond to that which they refer to. For example, a male teacher is an «enseignant» while a female teacher is an «enseignante». However, plural nouns that refer to a group that includes both masculine and feminine entities are always masculine. So a group of two male teachers would be «enseignants». A group of two male teachers and two female teachers would still be «enseignants». In many situations, and in the case of «enseignant», both the singular and plural form of a noun are pronounced identically. The article used for singular nouns is different from that used for plural nouns and the article provides a distinguishing factor between the two in speech. For example, the singular «le professeur» or «la professeur(e)» (the male or female teacher, professor) can be distinguished from the plural «les professeurs» because «le», «la», and «les» are all pronounced differently. There are some situations where both the feminine and masculine form of a noun are the same and the article provides the only difference. For example, «le dentiste» refers to a male dentist while «la dentiste» refers to a female dentist.

Verbs

Moods and tense-aspect forms

The French language consists of both finite and non-finite moods. The finite moods include the indicative mood (indicatif), the subjunctive mood (subjonctif), the imperative mood (impératif), and the conditional mood (conditionnel). The non-finite moods include the infinitive mood (infinitif), the present participle (participe présent), and the past participle (participe passé).

Finite moods

Indicative (Indicatif)

The indicative mood makes use of eight tense-aspect forms. These include the present (présent), the simple past (passé composé and passé simple), the past imperfective (imparfait), the pluperfect (plus-que-parfait), the simple future (futur simple), the future perfect (futur antérieur), and the past perfect (passé antérieur). Some forms are less commonly used today. In today’s spoken French, the passé composé is used while the passé simple is reserved for formal situations or for literary purposes. Similarly, the plus-que-parfait is used for speaking rather than the older passé antérieur seen in literary works.

Within the indicative mood, the passé composé, plus-que-parfait, futur antérieur, and passé antérieur all use auxiliary verbs in their forms.

| Indicatif | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Présent | Imparfait | Passé composé | Passé simple | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st Person | j’aime | nous aimons | j’aimais | nous aimions | j’ai aimé | nous avons aimé | j’aimai | nous aimâmes |

| 2nd Person | tu aimes | vous aimez | tu aimais | vous aimiez | tu as aimé | vous avez aimé | tu aimas | vous aimâtes |

| 3rd Person | il/elle aime | ils/elles aiment | il/elle aimait | ils/elles aimaient | il/elle a aimé | ils/elles ont aimé | il/elle aima | ils/elles aimèrent |

| Futur simple | Futur antérieur | Plus-que-parfait | Passé antérieur | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st Person | j’aimerai | nous aimerons | j’aurai aimé | nous aurons aimé | j’avais aimé | nous avions aimé | j’eus aimé | nous eûmes aimé |

| 2nd Person | tu aimeras | vous aimerez | tu auras aimé | vous aurez aimé | tu avais aimé | vous aviez aimé | tu eus aimé | vous eûtes aimé |

| 3rd Person | il/elle aimera | ils/elles aimeront | il/elle aura aimé | ils/elles auront aimé | il/elle avait aimé | ils/elles avaient aimé | il/elle eut aimé | ils/elles eurent aimé |

Subjunctive (Subjonctif)

The subjunctive mood only includes four of the tense-aspect forms found in the indicative: present (présent), simple past (passé composé), past imperfective (imparfait), and pluperfect (plus-que-parfait).

Within the subjunctive mood, the passé composé and plus-que-parfait use auxiliary verbs in their forms.

| Subjonctif | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Présent | Imparfait | Passé composé | Plus-que-parfait | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st Person | j’aime | nous aimions | j’aimasse | nous aimassions | j’aie aimé | nous ayons aimé | j’eusse aimé | nous eussions aimé |

| 2nd Person | tu aimes | vous aimiez | tu aimasses | vous aimassiez | tu aies aimé | vous ayez aimé | tu eusses aimé | vous eussiez aimé |

| 3rd Person | il/elle aime | ils/elles aiment | il/elle aimât | ils/elles aimassent | il/elle ait aimé | ils/elles aient aimé | il/elle eût aimé | ils/elles eussent aimé |

Imperative (Imperatif)

The imperative is used in the present tense (with the exception of a few instances where it is used in the perfect tense). The imperative is used to give commands to you (tu), we/us (nous), and plural you (vous).

| Imperatif | ||

|---|---|---|

| Présent | ||

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1st Person | aimons | |

| 2nd Person | aime | aimez |

Conditional (Conditionnel)

The conditional makes use of the present (présent) and the past (passé).

The passé uses auxiliary verbs in its forms.

| Conditionnel | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Présent | Passé | |||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st Person | j’aimerais | nous aimerions | j’aurais aimé | nous aurions aimé |

| 2nd Person | tu aimerais | vous aimeriez | tu aurais aimé | vous auriez aimé |

| 3rd Person | il/elle aimerait | ils/elles aimeraient | il/elle aurait aimé | ils/elles auraient aimé |

Voice

French uses both the active voice and the passive voice. The active voice is unmarked while the passive voice is formed by using a form of verb être («to be») and the past participle.

Example of the active voice:

- «Elle aime le chien.» She loves the dog.

- «Marc a conduit la voiture.» Marc drove the car.

Example of the passive voice:

- «Le chien est aimé par elle.» The dog is loved by her.

- «La voiture a été conduite par Marc.» The car was driven by Marc.

Syntax

Word order

French declarative word order is subject–verb–object although a pronoun object precedes the verb. Some types of sentences allow for or require different word orders, in particular inversion of the subject and verb, as in «Parlez-vous français ?» when asking a question rather than «Vous parlez français ?» Both formulations are used, and carry a rising inflection on the last word. The literal English translations are «Do you speak French?» and «You speak French?», respectively. To avoid inversion while asking a question, «Est-ce que» (literally «is it that») may be placed at the beginning of the sentence. «Parlez-vous français ?» may become «Est-ce que vous parlez français ?» French also uses verb–object–subject (VOS) and object–subject–verb (OSV) word order. OSV word order is not used often and VOS is reserved for formal writings.[35]

Vocabulary

Root languages of loanwords[110]

English (25.10%)

Other Asian languages (2.12%)

Other languages (3.43%)

The majority of French words derive from Vulgar Latin or were constructed from Latin or Greek roots. In many cases, a single etymological root appears in French in a «popular» or native form, inherited from Vulgar Latin, and a learned form, borrowed later from Classical Latin. The following pairs consist of a native noun and a learned adjective:

- brother: frère / fraternel from Latin frater / fraternalis

- finger: doigt / digital from Latin digitus / digitalis

- faith: foi / fidèle from Latin fides / fidelis

- eye: œil / oculaire from Latin oculus / ocularis

However, a historical tendency to Gallicise Latin roots can be identified, whereas English conversely leans towards a more direct incorporation of the Latin:

- rayonnement / radiation from Latin radiatio

- éteindre / extinguish from Latin exstinguere

- noyau / nucleus from Latin nucleus

- ensoleillement / insolation from Latin insolatio

There are also noun-noun and adjective-adjective pairs:

- thing/cause: chose / cause from Latin causa

- cold: froid / frigide from Latin frigidum

It can be difficult to identify the Latin source of native French words because in the evolution from Vulgar Latin, unstressed syllables were severely reduced and the remaining vowels and consonants underwent significant modifications.

More recently[when?] the linguistic policy of the French language academies of France and Quebec has been to provide French equivalents[111] to (mainly English) imported words, either by using existing vocabulary, extending its meaning or deriving a new word according to French morphological rules. The result is often two (or more) co-existing terms for describing the same phenomenon.

- mercatique / marketing

- finance fantôme / shadow banking

- bloc-notes / notepad

- ailière / wingsuit

- tiers-lieu / coworking

It is estimated that 12% (4,200) of common French words found in a typical dictionary such as the Petit Larousse or Micro-Robert Plus (35,000 words) are of foreign origin (where Greek and Latin learned words are not seen as foreign). About 25% (1,054) of these foreign words come from English and are fairly recent borrowings. The others are some 707 words from Italian, 550 from ancient Germanic languages, 481 from other Gallo-Romance languages, 215 from Arabic, 164 from German, 160 from Celtic languages, 159 from Spanish, 153 from Dutch, 112 from Persian and Sanskrit, 101 from Native American languages, 89 from other Asian languages, 56 from other Afro-Asiatic languages, 55 from Balto-Slavic languages, 10 from Basque and 144 (about 3%) from other languages.[110]

One study analyzing the degree of differentiation of Romance languages in comparison to Latin estimated that among the languages analyzed French has the greatest distance from Latin.[112] Lexical similarity is 89% with Italian, 80% with Sardinian, 78% with Rhaeto-Romance, and 75% with Romanian, Spanish and Portuguese.[113][1]

Numerals

The numeral system used in the majority of Francophone countries employs both decimal and vigesimal counting. After the use of unique names for the numbers 1-16, those from 17 to 69 are counted by tens, while twenty (vingt) is used as a base number in the names of numbers from 70 to 99. The French word for 80 is quatre-vingts, literally «four twenties», and the word for 75 is soixante-quinze, literally «sixty-fifteen». The vigesimal method of counting is analogous to the archaic English use of score, as in «fourscore and seven» (87), or «threescore and ten» (70).

Belgian, Swiss, and Aostan French[114] as well as that used in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, use different names for 70 and 90, namely septante and nonante. In Switzerland, depending on the local dialect, 80 can be quatre-vingts (Geneva, Neuchâtel, Jura) or huitante (Vaud, Valais, Fribourg). The Aosta Valley similarly uses huitante[114] for 80. Conversely, Belgium and in its former African colonies use quatre-vingts for 80.

In Old French (during the Middle Ages), all numbers from 30 to 99 could be said in either base 10 or base 20, e.g. vint et doze (twenty and twelve) for 32, dous vinz et diz (two twenties and ten) for 50, uitante for 80, or nonante for 90.[115]

The term octante was historically used in Switzerland for 80, but is now considered archaic.[116]

French, like most European languages, uses a space to separate thousands.[117] The comma (French: virgule) is used in French numbers as a decimal point, i.e. «2,5» instead of «2.5». In the case of currencies, the currency markers are substituted for decimal point, i.e. «5$7» for «5 dollars and 7 cents».

Example text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in French:

- Tous les êtres humains naissent libres et égaux en dignité et en droits. Ils sont doués de raison et de conscience et doivent agir les uns envers les autres dans un esprit de fraternité.[118]

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[119]

See also

- Alliance Française

- AZERTY

- Français fondamental

- Francization

- Francophile

- Francophobia

- Francophonie

- French language in the United States

- French language in Canada

- French poetry

- Glossary of French expressions in English

- Influence of French on English

- Language education

- List of countries where French is an official language

- List of English words of French origin

- List of French loanwords in Persian

- List of French words and phrases used by English speakers

- List of German words of French origin

- Official bilingualism in Canada

- Varieties of French

Notes

- ^ 29 full members of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF): Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, DR Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Niger, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Seychelles, Togo, and Tunisia.

One associate member of the OIF: Ghana.

One observer of the OIF: Mozambique.

One country not member or observer of the OIF: Algeria.

Two French territories in Africa: Réunion and Mayotte.

References

- ^ a b c d French at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ «In which countries of the world is this language spoken…» Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ «Official Languages». www.un.org. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ «Census in Brief: English, French and official language minorities in Canada». www12.statcan.gc.ca. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ a b «The status of French in the world». Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ a b European Commission (June 2012), «Europeans and their Languages» (PDF), Special Eurobarometer 386, Europa, p. 5, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016, retrieved 7 September 2014

- ^ «Why Learn French». Archived from the original on 19 June 2008.

- ^ Develey, Alice (25 February 2017). «Le français est la deuxième langue la plus étudiée dans l’Union européenne» – via Le Figaro.

- ^ «How many people speak French and where is French spoken». Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ (in French) La Francophonie dans le monde 2006–2007 published by the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. Nathan Archived 14 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Paris, 2007.

- ^ «Estimation des francophones dans le monde en 2015. Sources et démarches méthodologiques.» [archive] [PDF], sur Observatoire démographique et statistique de l’espace francophone [archive].

- ^ a b «Francophonie («Qu’est-ce que la Francophonie?»)». www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca.

- ^ «The World’s Most Widely Spoken Languages». Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ «La langue française dans le monde» (PDF). Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ «French language is on the up, report reveals». thelocal.fr. 6 November 2014.

- ^ «Agora: La francophonie de demain». 24 November 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ Lauerman, John (30 August 2011). «Mandarin Chinese Most Useful Business Language After English». Bloomberg. New York. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015.

French, spoken by 68 million people worldwide and the official language of 27 countries, was ranked second [to Mandarin].

- ^ a b Adams, J. N. (2007). «Chapter V – Regionalisms in provincial texts: Gaul». The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC – AD 600. Cambridge. pp. 279–289. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482977. ISBN 978-0-511-48297-7.

- ^ a b c Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

- ^ Lodge, R. Anthony (1993). French: From Dialect to Standard. p. 46. ISBN 9780415080712.

- ^ Craven, Thomas D. (2002). Comparative Historical Dialectology: Italo-Romance Clues to Ibero-Romance Sound Change. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 1588113132.

- ^ a b c Mufwene, Salikoko S. «Language birth and death.» Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 33 (2004): 201-222.

- ^ Peter Schrijver, Studies in the History of Celtic Pronouns and Particles, Maynooth, 1997, 15.

- ^ a b Savignac, Jean-Paul (2004). Dictionnaire Français-Gaulois. Paris: La Différence. p. 26.

- ^ Pellegrini, Giovanni Battista. 2011. «Substrata.» In Posner and Green (2011), Romance Comparative and Historical Linguistics, De Gruyter Mouton: pages 43-74. Celtic influences on French discussed in pages 64-67. Page 65:»In recent years the primary role of the substratum… has been disputed. Best documented is the CT- > it change which is found in all Western Romania… more reservations have been expressed about… ū > [y]…»; :»Summary on page 67: «There can be no doubt that the way French stands out from the other Western Romance languages (Vidos 1956: 363) is largely due to the intensity of its Celtic substratum, compared with lateral areas like Iberia and Venetia…»

- ^ Henri Guiter, «Sur le substrat gaulois dans la Romania», in Munus amicitae. Studia linguistica in honorem Witoldi Manczak septuagenarii, eds., Anna Bochnakowa & Stanislan Widlak, Krakow, 1995.

- ^ Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), 83.

- ^ Matasovic, Ranko (2007). «Insular Celtic as a Language Area». Papers from the Workship within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies. The Celtic Languages in Contact: 106.

- ^ Polinsky, Maria; Van Everbroeck, Ezra (2003). «Development of Gender Classifications: Modeling the Historical Change from Latin to French». Language. 79 (2): 356–390. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.134.9933. doi:10.1353/lan.2003.0131. JSTOR 4489422. S2CID 6797972.

- ^ Christian Schmitt (1997). «Keltische im heutigen Französisch». Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie. 49–50: 814–829.

- ^ Müller, Bodo (1982). «Geostatistik der gallischen/keltischen Substratwörter in der Galloromania». In Winkelmann, Otto (ed.). Festschrift für Johannes Hubschmid zum 65. Geburtsag. Beiträge zur allgemeinen, indogermanischen und romanischen Sprachwissenschaft. pp. 603–620.

- ^ a b Urban Holmes and Alexander Herman Schutz (June 1938). A History of the French Language. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. p. 30. ISBN 9780819601919.

«…sixty-eight or more Celtic words in standard Latin; not all of these came down into Romance…. did not survive among the people. Vulgar speech in Gaul used many others… at least 361 words of Gaulish provenance in French and Provençal. These Celtic words fell into more homely types than… borrowings from Germanː agriculture… household effects… animals… food and drink… trees… body — 17 (dor < durnu), dress… construction… birds… fish… insects… pièce < *pettia, and the remainder divided among weapons, religion, literature, music, persons, sickness and mineral. It is evident that the peasants were the last to hold to their Celtic. The count on the Celtic element was made by Leslie Moss at the University of North Carolina… based on unanimity of agreement among the best lexicographers…

- ^ a b Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), page 82.

- ^ a b c d «HarvardKey — Login». www.pin1.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b Lahousse, Karen; Lamiroy, Béatrice (2012). «Word order in French, Spanish and Italian:A grammaticalization account». Folia Linguistica. 46 (2). doi:10.1515/flin.2012.014. ISSN 1614-7308. S2CID 146854174.

- ^ Rowlett, P. 2007. The Syntax of French. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 4

- ^ Pope, Mildred K. (1934). From Latin to Modern French with Especial Consideration of Anglo-Norman Phonology and Morphology. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- ^ Victor, Joseph M. (1978). Charles de Bovelles, 1479–1553: An Intellectual Biography. Librairie Droz. p. 28.

- ^ The World’s 10 Most Influential Languages Archived 12 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Top Languages. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Battye, Adrian; Hintze, Marie-Anne; Rowlett, Paul (2003). The French Language Today: A Linguistic Introduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-41796-6.

- ^ Meisler, Stanley (1 March 1986). «Seduction Still Works : French—a Language in Decline». The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b Labouysse, Georges (2007). L’Imposture. Mensonges et manipulations de l’Histoire officielle. France: Institut d’études occitanes. ISBN 978-2-85910-426-9.

- ^ EUROPA, data for EU25, published before 2007 enlargement.

- ^ «Explore language knowledge in Europe». languageknowledge.eu.

- ^ Novoa, Cristina; Moghaddam, Fathali M. (2014). «Applied Perspectives: Policies for Managing Cultural Diversity». In Benet-Martínez, Verónica; Hong, Ying-Yi (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Multicultural Identity. Oxford Library of Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-19-979669-4. LCCN 2014006430. OCLC 871965715.

- ^ Van Parijs, Philippe, Professor of economic and social ethics at the UCLouvain, Visiting Professor at Harvard University and the KULeuven. «Belgium’s new linguistic challenge» (PDF). KVS Express (Supplement to Newspaper de Morgen) March–April 2006: Article from original source (pdf 4.9 MB) pp. 34–36 republished by the Belgian Federal Government Service (ministry) of Economy – Directorate–general Statistics Belgium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) – The linguistic situation in Belgium (and in particular various estimates of the population speaking French and Dutch in Brussels) is discussed in detail. - ^ Abalain, Hervé (2007). Le français et les langues. ISBN 978-2-87747-881-6. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ «Allemagne : le français, bientôt la deuxième langue officielle de la Sarre». 28 April 2014.

- ^ «German region of Saarland moves towards bilingualism». BBC News. 21 January 2014.

- ^ Population Reference Bureau. «2020 World Population Data Sheet — Population mid-2020». Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ United Nations. «World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision» (XLSX). Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Population Reference Bureau. «2020 World Population Data Sheet — Population mid-2050». Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ a b Observatoire de la langue française de l’Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. «Estimation du nombre de francophones (2018)» (PDF). Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Observatoire démographique et statistique de l’espace francophone (ODSEF). «Estimation des populations francophones dans le monde en 2018 — Sources et démarches méthodologiques» (PDF). Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Cross, Tony (19 March 2010), «French language growing, especially in Africa», Radio France Internationale, retrieved 25 May 2013

- ^ «Agora: La francophonie de demain». 24 November 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ «Bulletin de liaison du réseau démographie» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ (in French) Le français à Abidjan : Pour une approche syntaxique du non-standard by Katja Ploog, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2002.

- ^ «L’aménagement linguistique dans le monde». CEFAN (Chaire pour le développement de la recherche sur la culture d’expression française en Amérique du Nord, Université Laval (in French). Jacques Leclerc. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ «Annonces import export Francophone — CECIF.com». www.cecif.com.

- ^ France-Diplomatie Archived 27 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine «Furthermore, the demographic growth of Southern hemisphere countries leads us to anticipate a new increase in the overall number of French speakers.»

- ^ (in French) «Le français, langue en évolution. Dans beaucoup de pays francophones, surtout sur le continent africain, une proportion importante de la population ne parle pas couramment le français (même s’il est souvent la langue officielle du pays). Ce qui signifie qu’au fur et à mesure que les nouvelles générations vont à l’école, le nombre de francophones augmente : on estime qu’en 2015, ceux-ci seront deux fois plus nombreux qu’aujourd’hui. Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine»

- ^ (in French) c) Le sabir franco-africain Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine: «C’est la variété du français la plus fluctuante. Le sabir franco-africain est instable et hétérogène sous toutes ses formes. Il existe des énoncés où les mots sont français mais leur ordre reste celui de la langue africaine. En somme, autant les langues africaines sont envahies par les structures et les mots français, autant la langue française se métamorphose en Afrique, donnant naissance à plusieurs variétés.»

- ^ (in French) République centrafricaine Archived 5 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine: Il existe une autre variété de français, beaucoup plus répandue et plus permissive : le français local. C’est un français très influencé par les langues centrafricaines, surtout par le sango. Cette variété est parlée par les classes non-instruites, qui n’ont pu terminer leur scolarité. Ils utilisent ce qu’ils connaissent du français avec des emprunts massifs aux langues locales. Cette variété peut causer des problèmes de compréhension avec les francophones des autres pays, car les interférences linguistiques, d’ordre lexical et sémantique, sont très importantes. (One example of a variety of African French that is difficult to understand for European French speakers).

- ^ «What are the largest French-speaking cities in the world?». Tourist Maker. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ «Detailed Mother Tongue (186), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) (2006 Census)». 2.statcan.ca. 7 December 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ «Language Use in the United States: 2011, American Community Survey Reports, Camille Ryan, Issued August 2013» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ «LANGUAGE SPOKEN AT HOME BY ABILITY TO SPEAK ENGLISH FOR THE POPULATION 5 YEARS AND OVER : Universe: Population 5 years and over : 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates??». Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich; International Sociological Association (1989). Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 306–08. ISBN 978-0-89925-356-5. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ DeGraff, Michel; Ruggles, Molly (1 August 2014). «A Creole Solution for Haiti’s Woes». The New York Times. p. A17. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

Under the 1987 Constitution, adopted after the overthrow of Jean‑Claude Duvalier’s dictatorship, [Haitian] Creole and French have been the two official languages, but most of the population speaks only Creole fluently.

- ^ Ministère de l’Éducation nationale

- ^ «Guyana – World Travel Guide».

- ^ «Saint Pierre and Miquelon». CIA World Factbook. 18 October 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Michael (16 October 1993). «French Declines in Indochina, as English Booms». International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ says, Aly Chiman (1 February 2007). «The Role of English in Vietnam’s Foreign Language Policy: A Brief History». www.worldwide.rs.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Andy and Anthony J. Liddicoat, The Routledge International Handbook of Language Education Policy in Asia., Routledge, 2019, p. 192

- ^ a b «English to continue as link language in Puducherry: Court». The Times of India. 14 September 2014.

- ^ Pondicherry, the French outpost in India, France 24

- ^ Prof. Dr. Axel Tschentscher, LL.M. «Article 11 of the Lebanese Constitution». Servat.unibe.ch. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ OIF 2014, p. 217.

- ^ OIF 2014, p. 218.

- ^ OIF 2014, p. 358.

- ^ «How Qatar Became a Francophone Country».

- ^ Draaisma, Muriel (26 November 2016). «La Francophonie grants observer status to Ontario». CBC News. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ «Greece joins international Francophone body». EURACTIV.com. 29 November 2004. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ «P9-1 – Population de 14 ans et plus selon la connaissance du français, le sexe, par commune, «zone» et par province de résidence» (XLS) (in French). Government of France. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ a b Institut Statistique de Polynésie Française (ISPF). «Recensement 2017 – Données détaillées Langues». Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ a b STSEE. «Les premiers résultats du recensement de la population 2018 — Principaux_tableaux_population_2018» (in French). Archived from the original (ODS) on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Institut Statistique de Polynésie Française (ISPF). «Recensement 2007 – Données détaillées Langues». Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ «Tableau Pop_06_1 : Population selon le sexe, la connaissance du français et l’âge décennal» (in French). Government of France. Archived from the original (XLS) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Semple, Kirk (30 January 2014). «A Big Advocate of French in New York’s Schools: France». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022.

- ^ Gobry, Pascal-Emmanuel. «Want To Know The Language Of The Future? The Data Suggests It Could Be…French». Forbes.

- ^ «Focus — EU after Brexit: Will the French language make a comeback?». France 24. 17 October 2019.

- ^ Kai Chan, Distinguished Fellow, INSEAD Innovation and Policy Initiative, «These are the most powerful languages in the world», World Economic Forum, December 2016

- ^ Rodney Ball, Dawn Marley, The French-Speaking World: A Practical Introduction to Sociolinguistic Issues, Taylor & Francis, 2016, page 6

- ^ The French Ministry of Foreign affairs. «France-Diplomatie». France Diplomatie: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development.

- ^ Gobry, Pascal-Emmanuel (21 March 2014). «Want To Know The Language of the Future? The Data Suggests It Could Be…French». Forbes. Retrieved 18 November 2018.