The

vocabulary of a language includes not only words but also stable word

combinations which also serve as a means of expressing concepts. They

are phraseological word equivalents reproduced in speech the way

words are reproduced and not created anew in actual speech.

An

ordinary word combination is created according to the grammatical

rules of the language in accordance with a certain idea. The general

meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the

conjoined meanings of its elements. Every notional word functions

here as a certain member of the sentence. Thus, an ordinary word

combination is a syntactical pattern.

A

free word combination is a combination in which any element can be

substituted by another.

e.g.:

I

like this idea. I dislike this idea. He likes the idea. I like that

idea. I like this thought.

But

when we use the term free we are not precise. The freedom of a word

in a combination with others is relative as it is not only the

syntactical pattern that matters. There are logical limitations too.

The

second group of word combinations is semi-free word combinations.

They are the combinations in which the substitution is possible but

limited.

e.g.:

to

cut a poor/funny/strange figure.

Non-free

word combinations are those in which the substitution is impossible.

e.g.:

to

come clean, to be in low water.

2. Classifications of Phraseological Units

A

major stimulus to intensive studies of phraseology was prof.

Vinogradov’s research. The classification suggested by him has been

widely adopted by linguists working on other languages. The

classification of phraseological units suggested by V.V.

Vinogradov

includes:

—

standardised word combinations, i.e. phrases characterised by the

limited combinative power of their components, which retain their

semantic independence: to

meet the request/requirement,

подавати надію, страх бере, зачепити

гордість, покласти край;

—

phraseological unities, i.e. phrases in which the meaning of the

whole is not the sum of meanings of the components but it is based on

them and the motivation is apparent: to

stand to one’s guns,

передати куті меду, прикусити язика,

вивести на чисту воду, тримати камінь

за пазухою;

—

fusions, i.e. phrases in which the meaning cannot be derived as a

whole from the conjoined meanings of its components:

tit

for tat,

теревені правити, піймати облизня,

викинути коника, у Сірка очі позичити.

Phraseological

unities are very often metaphoric. The components of such unities are

not semantically independent, the meaning of every component is

subordinated to the figurative meaning of the phraseological unity as

a whole. The latter may have a homonymous expression — a free

syntactical word combination.

e.g.:

Nick

is a musician. He plays the first fiddle.

It

is his wife who plays the first fiddle in the house.

Phraseological

unities may vary in their semantic and grammatical structure. Not all

of them are figurative. Here we can find professionalisms, coupled

synonyms.

A.V.

Koonin

finds it necessary to divide English phraseological unities into

figurative and non-figurative.

Figurative

unities are often related to analogous expressions with direct

meaning in the very same way in which a word used in its transferred

sense is related to the same word used in its direct meaning.

Scientific

English, technical vocabulary, the vocabulary of arts and sports have

given many expressions of this kind: in

full blast; to hit below the belt; to spike smb’s guns.

Among

phraseological unities we find many verb-adverb combinations: to

look for; to look after; to put down; to give in.

Phraseological

fusions are the most synthetical of all the phraseological groups.

They seem to be completely unmotivated though their motivation can be

unearthed by means of historic analysis.

They

fall under the following groups:

Idiomatic

expressions which are associated with some obsolete customs: the

grey mare, to rob Peter to pay Paul.

Idiomatic

expressions which go back to some long forgotten historical facts

they were based on: to bell the cat, Damocles’ sword.

Idiomatic

expressions expressively individual in their character: My

God! My eye!

Idiomatic

expressions containing archaic elements: by

dint of (dint – blow); in fine (fine – end).

Semantic

Classification of Phraseological Units

1.

Phraseological units referring to the same notion.

e.g.:

Hard

work — to burn the midnight oil; to do back-breaking work; to hit the

books; to keep one’s nose to the grindstone; to work like a dog; to

work one’s fingers to the bone.

Compromise

– to find middle ground; to go halfway.

Independence

– to be on one’s own; to have a mind of one’s own; to stand on

one’s own two feet.

Experience

– to be an old hand at something; to know something like the back

of one’s palm; to know the rope.Ледарювати

– байдики бити, ханьки м’яти, ганяти

вітер по вулицях, тинятися з кутка в

куток, і за холодну воду не братися.

2.

Professionalisms

e.g.:

on

the rocks; to stick to one’s guns; breakers ahead. 3.

Phraseological units having similar components

e.g.:

a

dog in the manger; dog days; to agree like cat and dog; to rain cats

and dogs. To fall on deaf ears; to talk somebody’s ear off; to have

a good ear for; to be all ears. To see red; a red herring; a red

carpet treatment; to be in the red;

з перших рук; як без рук; горить у руках;

не давати волі рукам.

4.

Phraseological units referring to the same lexico-semantic field.

e.g.:

Body

parts – to cost an arm and leg; to pick somebody’s brain; to get

one’s feet wet; to get off the chest; to rub elbows with; not to

have a leg to stand on; to stick one’s neck out; to be nosey; to

make a headway; to knuckle down; to shake a leg; to pay through the

noser; to tip toe around; to mouth off;

без клепки в голові; серце з перцем;

легка рука.

Fruits

and vegetables –

red as a beet; a couch potato; a hot potato; a real peach; as cool as

a cucumber; a top banana;гриби

після дощу; як горох при дорозі; як

виросте гарбуз на вербі.

Animals

– sly

as a fox; to be a bull in a china shop; to go ape; to be a lucky dog;

to play cat and mouse;

як з гуски вода, як баран на нові ворота;

у свинячий голос; гнатися за двома

зайцями.

Structural

Classification of Phraseological Units

Еnglish

phraseological units can function like verbs (to

drop a brick; to drop a line; to go halves; to go shares; to travel

bodkin),

phraseological units functioning like nouns (brains

trust, ladies’ man,

phraseological units functioning like adjectives (high

and dry,

high

and low,ill at ease,

phraseological units functioning like adverbs (tooth

and nail, on

guard;

by heart,

phraseological units functioning like prepositions (in

order to; by virtue

of),

phraseological units functioning like interjections (Good

heavens! Gracious me! Great Scot!).

Ukrainian

phraseological

units

can

function

like

nouns

(наріжний

камінь, біла ворона, лебедина пісня),

adjectives

(

не з полохливого десятка, не остання

спиця в

колесі,

білими нитками шитий),

verbs

(

мотати на вус, товкти воду в ступі,

ускочити

в

халепу),

adverbs

(

не чуючи землі під ногами, кров холоне

в жилах, ні в зуб ногою), interjections

(цур тобі, ні пуху ні пера, хай йому

грець).

Another

structural classification was initiated by A.V. Koonin. He singles

out Nominative, Nominative and Nominative-Communicative,

Interjective, Communicative phraseological units.

Nominative

phraseological units are of several types. It depends on the type of

dependence. The first one is phraseological units with constant

dependence of the elements.

e.g.:

the

Black Maria; the ace of trumps; a spark in the powder magazine.

The

second type is represented by the phraseological units with the

constant variant dependence of the elements.

e.g.:

dead

marines/men; a blind pig/tiger; a good/great deal.

There

also exist phraseological units with grammar variants.

e.g.:

Procrustes’

bed = the Procrustean bed = the bed of Procrustes.

Another

type of the Nominative phraseological units is units with

quantitative variants. They are formed with the help of the reduction

or adding the elements.

e.g.:

the

voice of one crying in the wilderness = a voice crying out in the

wilderness= a voice crying in the wilderness = a voice in the

wilderness.

The

next type of the Nominative phraseological units is adjectival

phraseological units.

e.g.:

mad

as a hatter; swift as thought; as like as two peas; fit as a fiddle.

The

function of the adverbial phraseological units is that of an

adverbial modifier of attendant circumstances.

e.g.:

as

cool as a cucumber; from one’s cradle to one’s grave; from pillar

to post; once in a blue moon.

Nominative

and Nominative-Communicative phraseological units are of several

types as well. The first type is verbal phraseological units. Verbal

phraseological units refer to this type in such cases: a) when the

verb is not used in the Passive voice (

to drink

like

a fish; to buy a pig in a poke; to close one’s eyes on something

; b) if the verb is not used in the Active voice (to

be reduced to a shadow; to be gathered to one’s fathers).

Nominative

and Nominative-Communicative phraseological units can have lexical

variants.

e.g.:

to

tread/walk on air; to close/shut books; to draw a red herring across

the trail/track; to come to a fine/handsome/nice/pretty pass; to sail

close/near to the wind; to crook/lift the elbow/the little finger.

Grammar

variants are also possible.

e.g.:

to

get into deep water = to get into deep waters; to pay nature’s debt

= to pay the debt of nature.

Examples

of quantitative variants can also be found: to

cut the Gordian knot = to cut the knot; to lead somebody a dance = to

lead somebody a pretty dance.

Lexico-grammar

variants are also possible: to

close/shut a /the door/doors on/upon/to somebody.

Interjective

phraseological units are represented by: by

George! By Jove! Good heavens! Gracious me!

Communicative

phraseological units are represented by proverbs and sayings.

e.g.:

Rome

was not built in a day. An apple a day keeps a doctor away. That’s

another pair of shoes. More power to your elbow. Carry me out.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

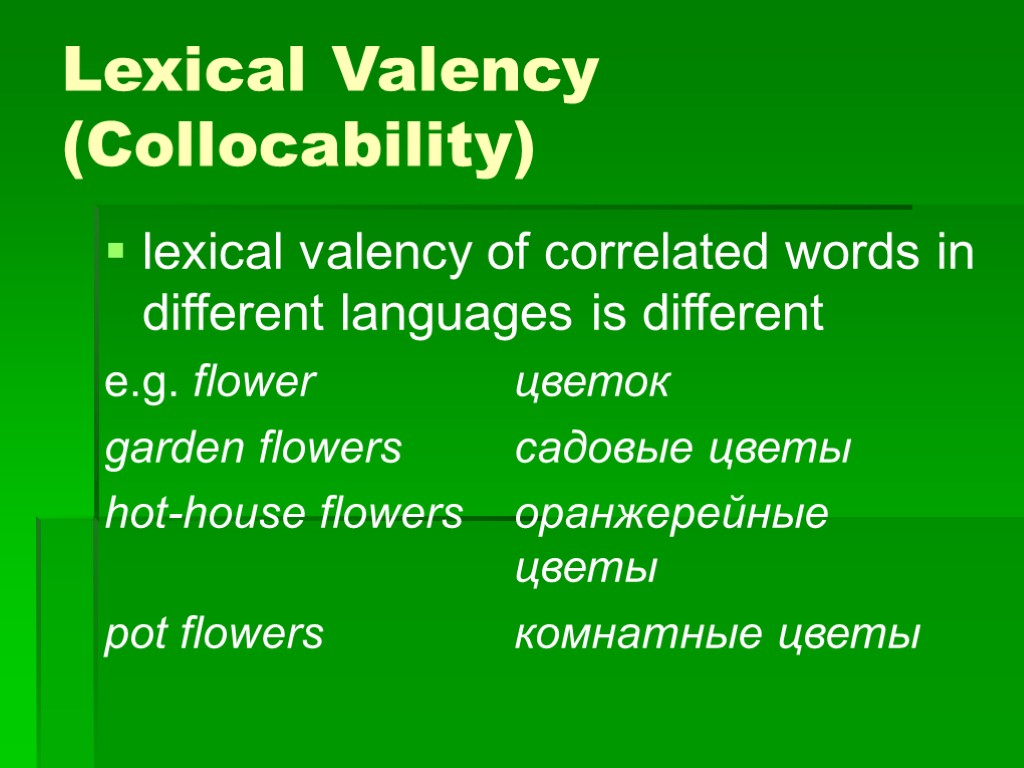

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

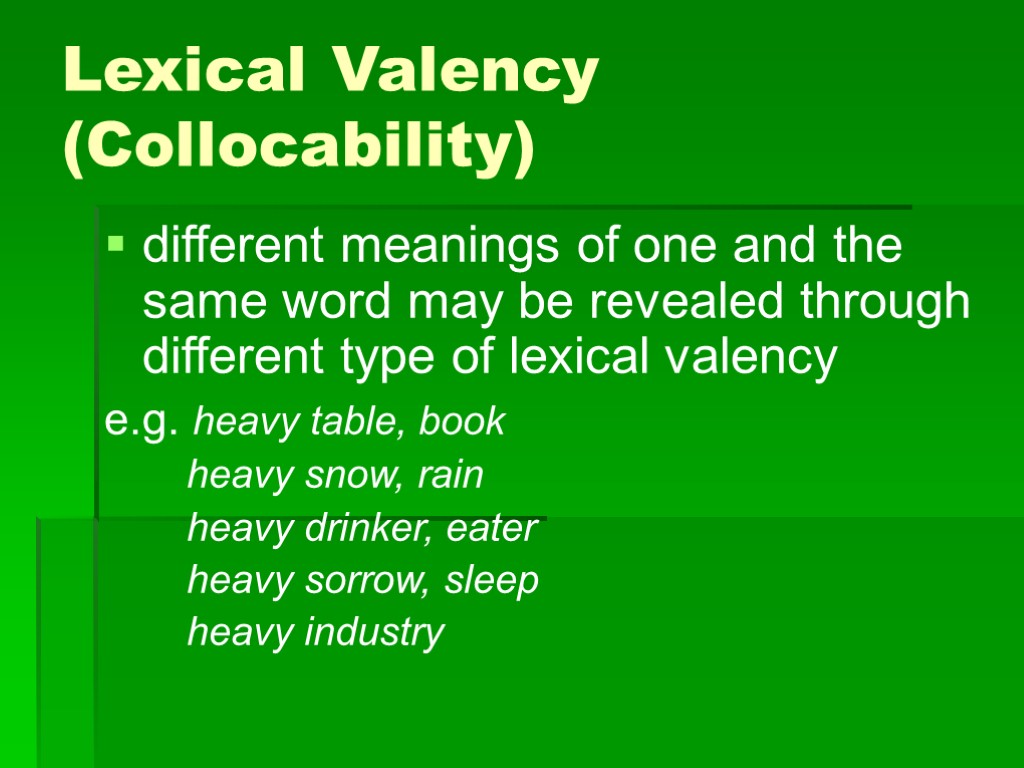

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

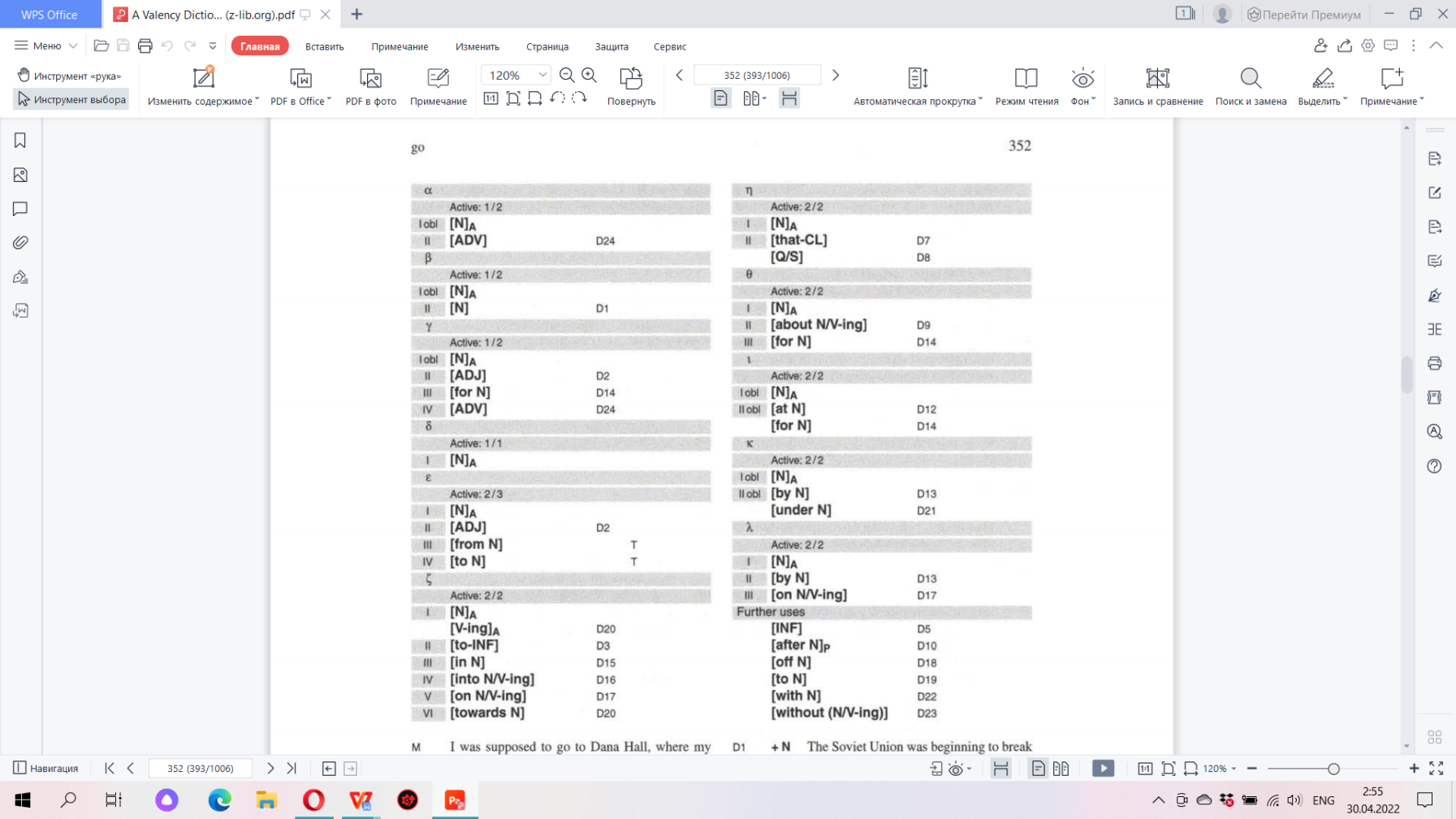

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

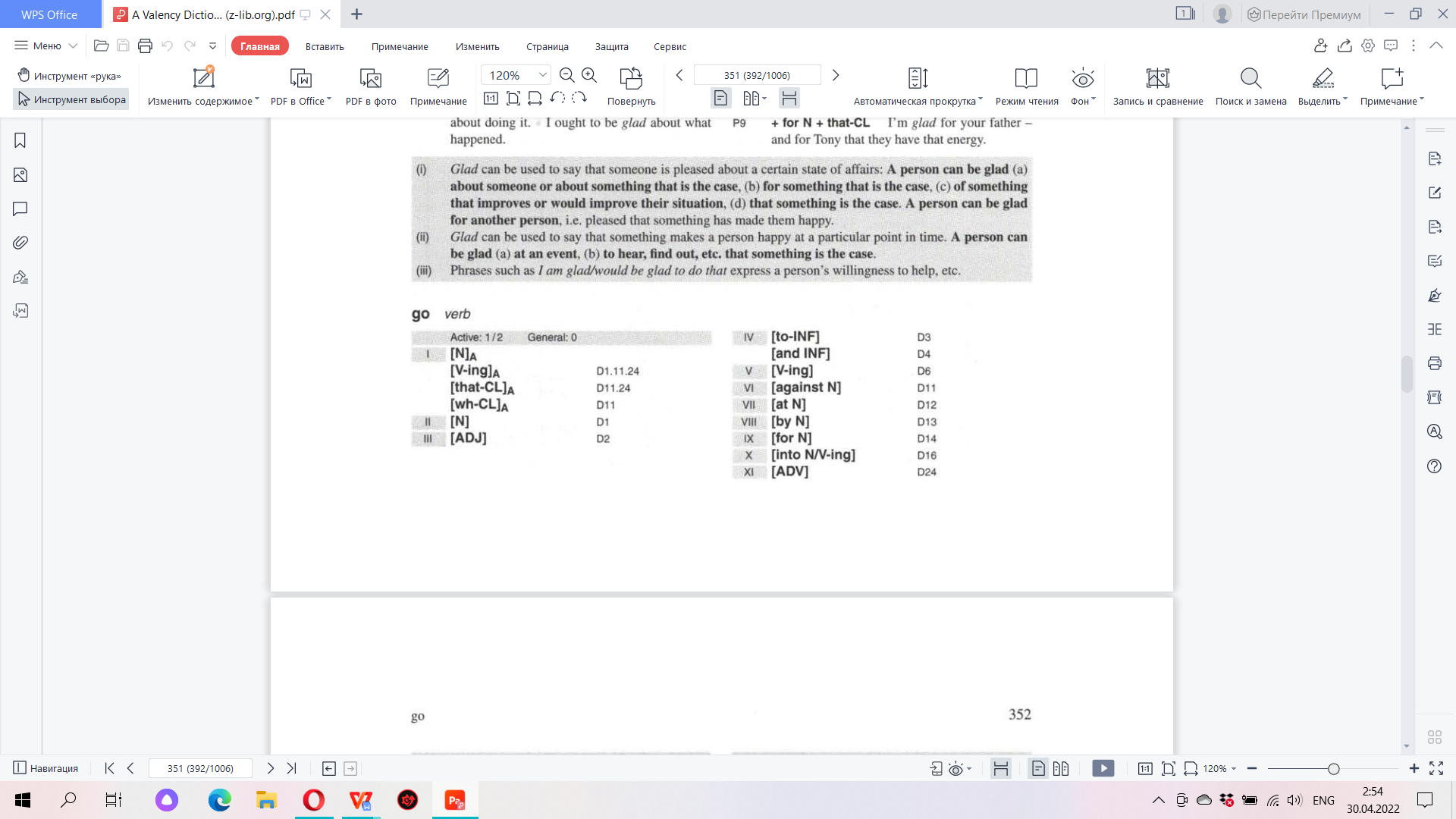

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |

| This year, my garden yielded several baskets full of tomatoes. | produce or provide |

| It is important for a teacher to develop a rapport with his or her students. | good relationship |

FREE-WORD COMBINATIONS

Definition of a word-group and its basic features Structure of word-groups Meaning of word-groups Motivation in word-groups

Word-Group the largest two-facet language unit consists of more than one word studied in the syntagmatic level of analysis

Word-Group the degree of structural and semantic cohesion may vary e.g. at least, by means of, take place – semantically and structurally inseparable e.g. a week ago, kind to people – have greater semantic and structural independence

Free-Word Combination word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose

Features of Word-groups Lexical Valency Grammatical Valency

Lexical Valency (Collocability) The ability of a word to appear in various combinations with other words, or lexical contexts e.g. question – vital/pressing/urgent/etc., question at issue, to raise a question, a question on the agenda

Lexical Valency (Collocability) words habitually collocated in speech make a cliché e.g. to put forward a question

Lexical Valency (Collocability) lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different e.g. flower цветок garden flowers садовые цветы hot-house flowers оранжерейные цветы pot flowers комнатные цветы

Lexical Valency (Collocability) different meanings of one and the same word may be revealed through different type of lexical valency e.g. heavy table, book heavy snow, rain heavy drinker, eater heavy sorrow, sleep heavy industry

Grammatical Valency The ability of a word to appear in specific grammatical structures, or grammatical contexts

Grammatical Valency the minimal grammatical context in which the words are used when brought together to form a word-group is called the pattern of the word-group

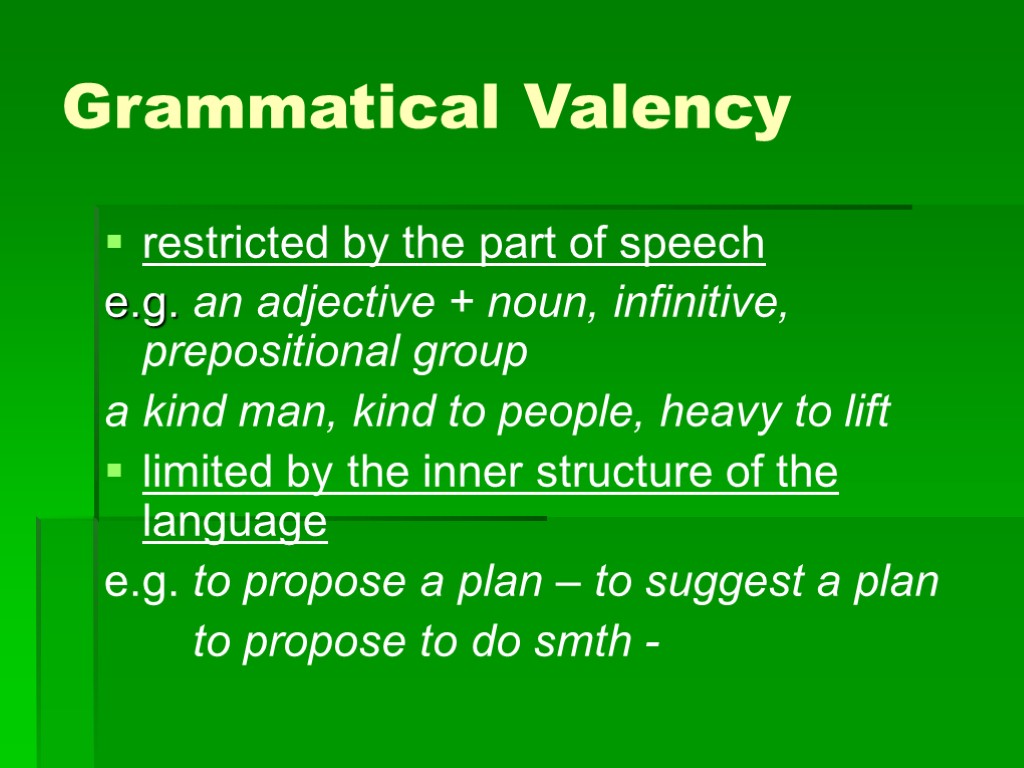

Grammatical Valency restricted by the part of speech e.g. an adjective + noun, infinitive, prepositional group a kind man, kind to people, heavy to lift limited by the inner structure of the language e.g. to propose a plan – to suggest a plan to propose to do smth —

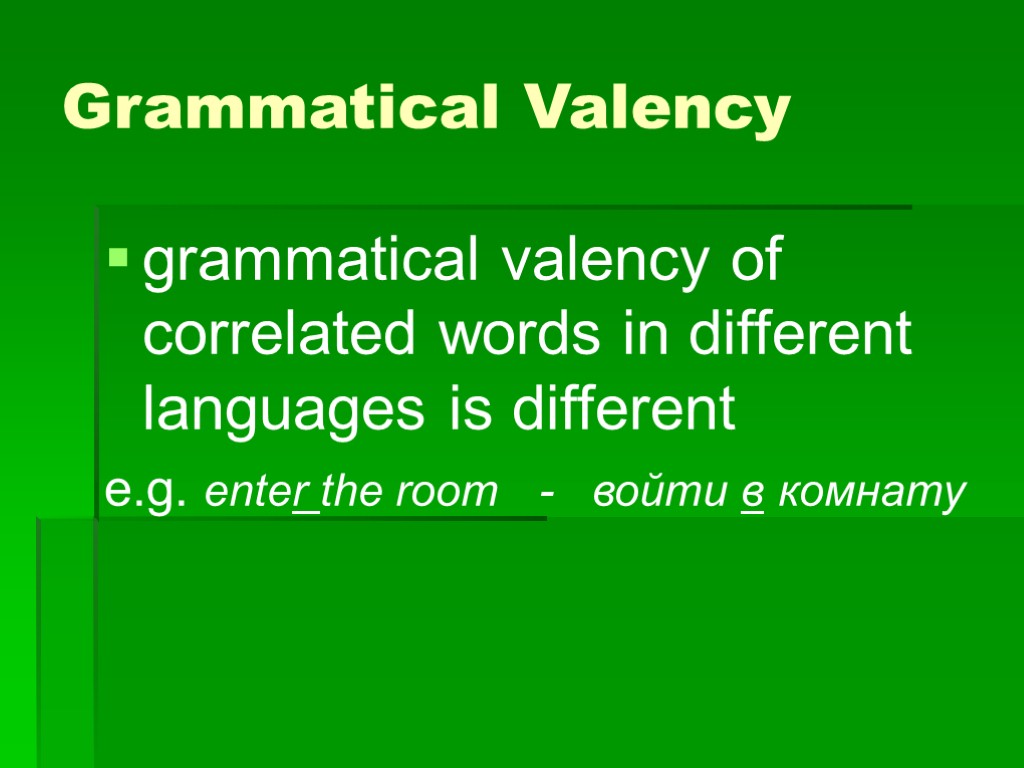

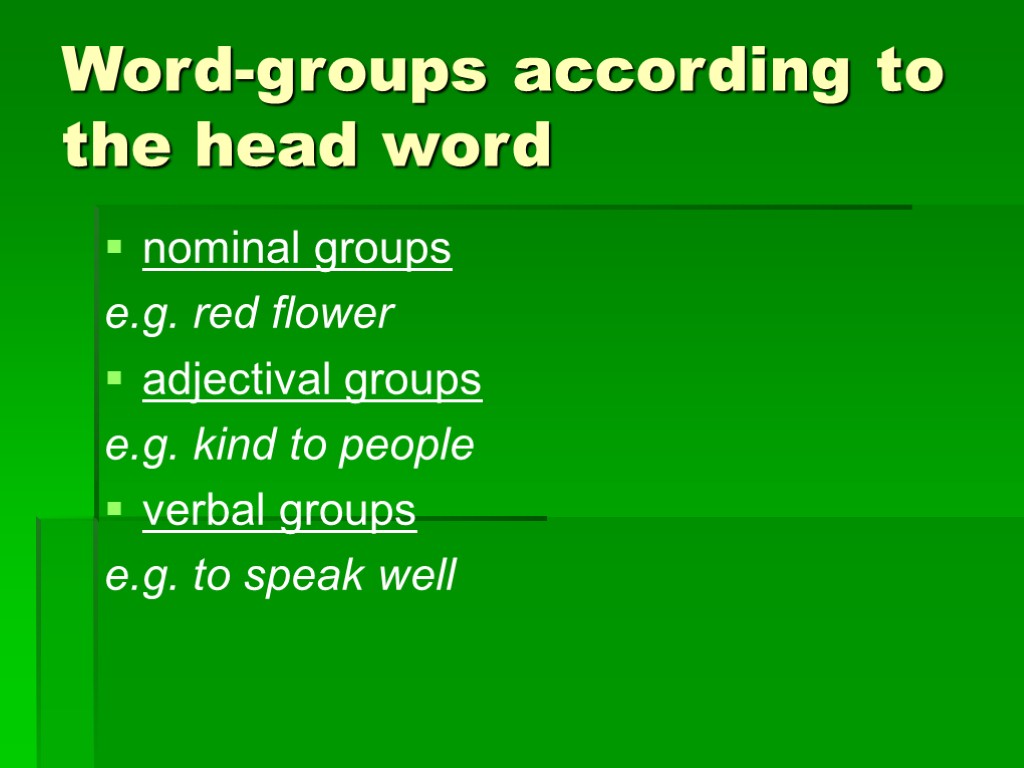

Grammatical Valency grammatical valency of correlated words in different languages is different e.g. enter the room — войти в комнату

Classifications of word-groups according to the distribution according to the head-word according to the syntactic pattern

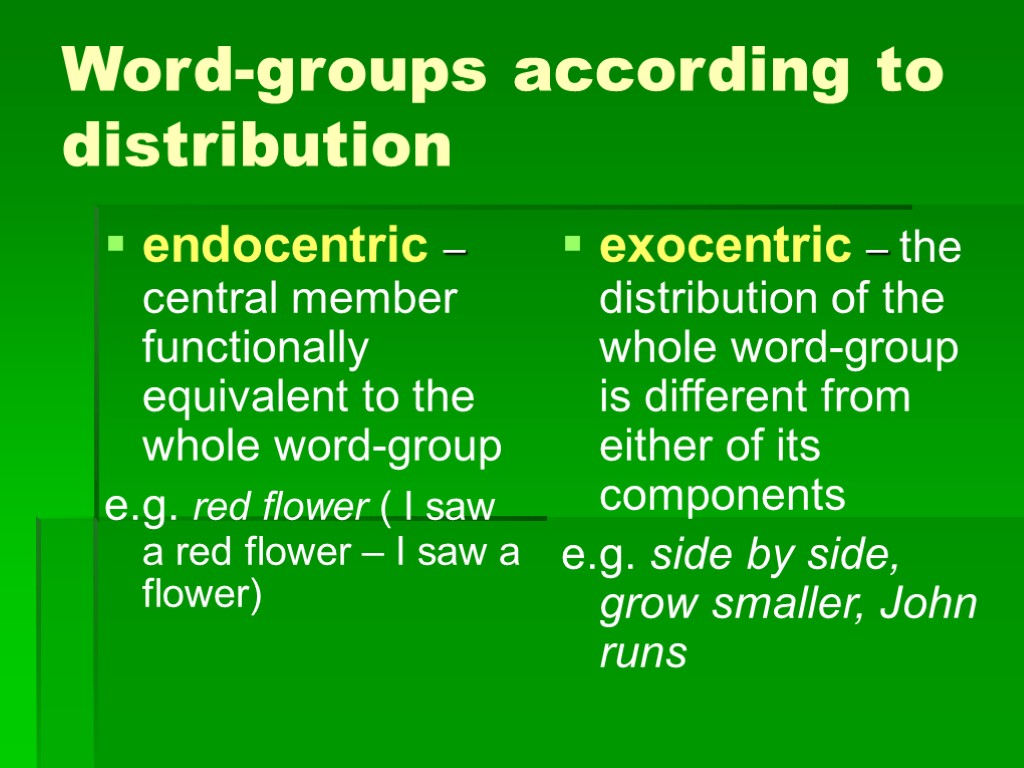

Word-groups according to distribution endocentric – central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group e.g. red flower ( I saw a red flower – I saw a flower) exocentric – the distribution of the whole word-group is different from either of its components e.g. side by side, grow smaller, John runs

Word-groups according to the head word nominal groups e.g. red flower adjectival groups e.g. kind to people verbal groups e.g. to speak well

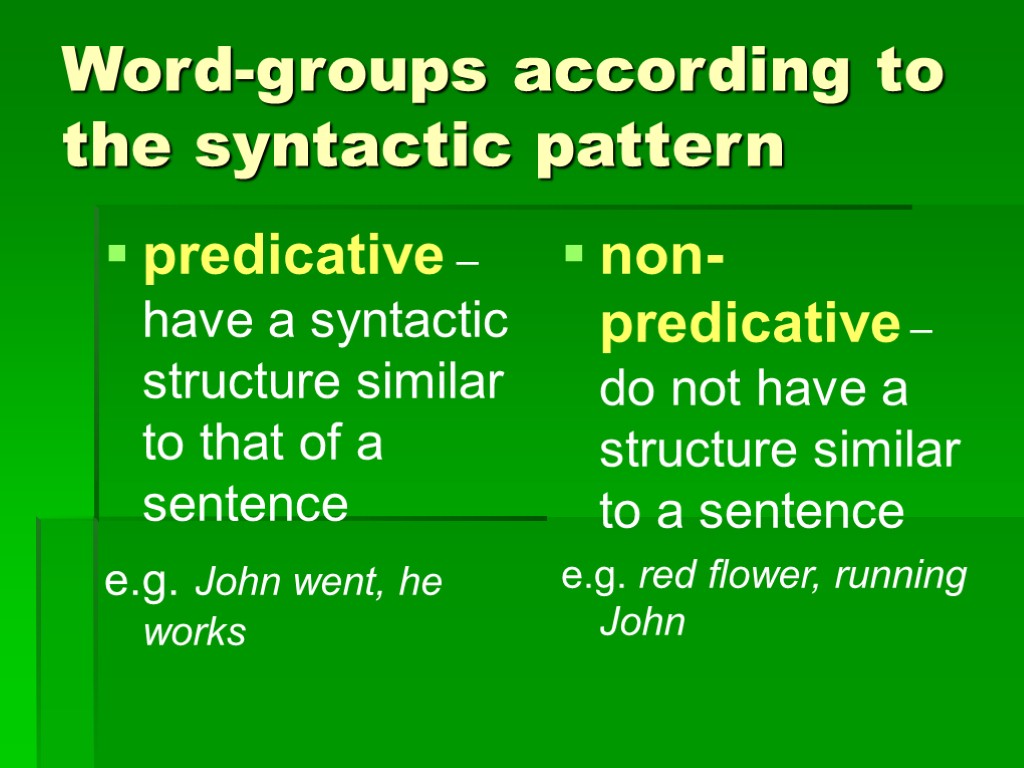

Word-groups according to the syntactic pattern predicative – have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence e.g. John went, he works non-predicative – do not have a structure similar to a sentence e.g. red flower, running John

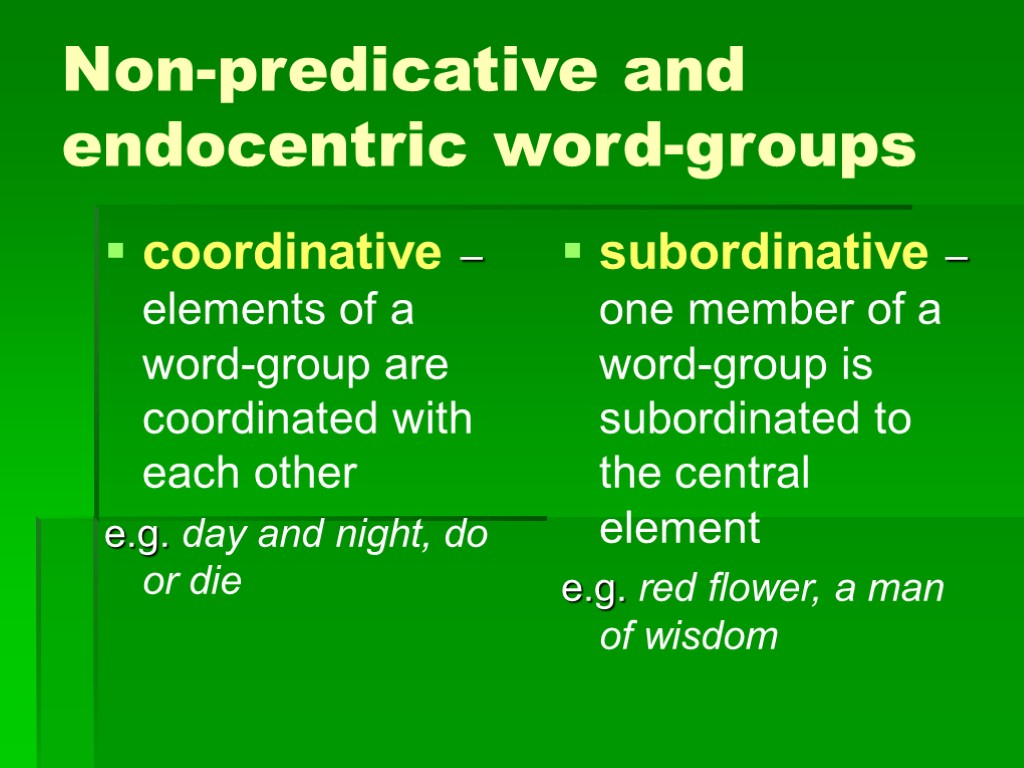

Non-predicative and endocentric word-groups coordinative – elements of a word-group are coordinated with each other e.g. day and night, do or die subordinative – one member of a word-group is subordinated to the central element e.g. red flower, a man of wisdom

Meaning of Word-Groups lexical meaning structural meaning

Lexical meaning the combined lexical meaning of the component words BUT the meaning of the word-group predominates over the lexical meanings of its components e.g. atomic weight, atomic warfare

Lexical meaning polysemantic words are used only in one of their meanings e.g. man and wife, blind man stylistic reference of a word-group may be different from that of its components e.g. old, boy, bags, fun – old boy (дружище), bags of fun

Structural meaning meaning conveyed by the arrangement of components of a word-group e.g. school grammar – grammar school

Structural meaning structural and lexical meanings are interdependent and inseparable e.g. school children – to school children all the sun long – all the night long, all the week long

Motivation in Word-groups lexically motivated — the combined lexical meaning of a group is deducible from the meanings of its components lexically non-motivated – the meaning of the whole is not seen through the meanings of the elements

Motivation in Word-groups lexically motivated e.g. red flower lexically non-motivated e.g. red tape – ‘official bureaucratic methods’

Motivation in Word-groups e.g. apple sauce – ‘a sauce made of apples’ apple sauce – ‘nonsense’

Motivation in Word-groups Non-motivated word-groups are called phraseological units or idioms

Free word groups and phraseological units

A word-group is the largest two-facet lexical unit comprising more than one word but expressing one global concept.

The lexical meaning of the word groups is the combined lexical meaning of the component words. The meaning of the word groups is motivated by the meanings of the component members and is supported by the structural pattern. But it’s not a mere sum total of all these meanings! Polysemantic words are used in word groups only in 1 of their meanings. These meanings of the component words in such word groups are mutually interdependent and inseparable (blind man – «a human being unable to see», blind type – «the copy isn’t readable).

Word groups possess not only the lexical meaning, but also the meaning conveyed mainly by the pattern of arrangement of their constituents. The structural pattern of word groups is the carrier of a certain semantic component not necessarily dependent on the actual lexical meaning of its members (school grammar – «grammar which is taught in school», grammar school – «a type of school»). We have to distinguish between the structural meaning of a given type of word groups as such and the lexical meaning of its constituents.

It is often argued that the meaning of word groups is also dependent on some extra-linguistic factors – on the situation in which word groups are habitually used by native speakers.

Words put together to form lexical units make phrases or word-groups. One must recall that lexicology deals with words, word-forming morphemes and word-groups.

The degree of structural and semantic cohesion of word-groups may vary. Some word-groups, e.g. at least, point of view, by means, to take place, etc. seem to be functionally and semantically inseparable. They are usually described as set phrases, word-equivalents or phraseological units and are studied by the branch of lexicology which is known as phraseology. In other word-groups such as to take lessons, kind to people, a week ago, the component-members seem to possess greater semantic and structural independence. Word-groups of this type are defined as free word-groups or phrases and are studied in syntax.

Before discussing phraseology it is necessary to outline the features common to various word-groups irrespective of the degree of structural and semantic cohesion of the component-words.

There are two factors which are important in uniting words into word-groups:

– the lexical valency of words;

– the grammatical valency of words.

Lexical valency

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. E.g. the noun question is often combined with such adjectives as vital, pressing, urgent, delicate, etc.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency. The range of the lexical valency of words is delimited by the inner structure of the English words. Thus, to raise and to lift are synonyms, but only the former is collocated with the noun question. The verbs to take, to catch, to seize, to grasp are synonyms, but they are found in different collocations:

to take – exams, measures, precautions, etc.;

to grasp – the truth, the meaning.

Words habitually collocated in speech tend to form a cliche.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical, because as it was said before, it depends on the inner structure of the vocabulary of the language. Both the English flower and the Russian цветок may be combined with a number of similar words, e.g. garden flowers, hot house flowers (cf. the Russian – садовые цветы, оранжерейные цветы), but in English flower cannot be combined with the word room, while in Russian we say комнатные цветы (in English we say pot-flowers).

Words are also used in grammatical contexts. The minimal grammatical context in which the words are used to form word-groups is usually described as the pattern of the word-group. E.g., the adjective heavy can be followed by a noun (A+N) – heavy food, heavy storm, heavy box, heavy eater. But we cannot say «heavy cheese» or «heavy to lift, to carry», etc.

The aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactical) structures is termed grammatical valency.

The grammatical valency of words may be different. The grammatical valency is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. E.g., no English adjective can be followed by the finite form of a verb.

Then, the grammatical valency is also delimited by the inner structure of the language. E.g., to suggest, to propose are synonyms. Both can be followed by a noun, but only to propose can be followed by the infinitive of a verb – to propose to do something.

Clever and intelligent have the same grammatical valency, but only clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern A+prep+N – clever at maths.

Structurally word-groups can be considered in different ways. Word-groups may be described as for the order and arrangement of the component-members. E.g., the word-group to read a book can be classified as a verbal-nominal group, to look at smb. – as a verbal-prepositional-nominal group, etc.

By the criterion of distribution all word-groups may be divided into two big classes: according to their head-words and according to their syntactical patterns.

Word-groups may be classified according to their head-words into:

nominal groups – red flower;

adjective groups – kind to people;

verbal groups – to speak well.

The head is not necessarily the component that occurs first.

Word-groups are classified according to their syntactical pattern into predicative and non-predicative groups. Such word-groups as he went, Bob walks that have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence are termed as predicative, all others are non-predicative ones.

Non-predicative word-groups are divided into subordinative and coordinative depending on the type of syntactic relations between the components. E.g., a red flower, a man of freedom are subordinative non-predicative word-groups, red and freedom being dependent words, while day and night, do and die are coordinative non-predicative word-groups.

The lexical meaning of a word-group may be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the component members. But it should be pointed out, however, that the term «combined lexical meaning» does not imply that the meaning of the word-group is always a simple additive result of all the lexical meanings of the component words. As a rule, the meanings of the component words are mutually dependent and the meaning of the word-group naturally predominates over the lexical meaning of the components. The interdependence is well seen in word-groups made up of polysemantic words. E.g., in the phrases the blind man, the blind type the word blind has different meanings – unable to see and vague.

So we see that polysemantic words are used in word-groups only in one of their meanings.

The term motivation is used to denote the relationship existing between the phonemic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one hand and its meaning on the other.

There are three main types of motivation:

1) phonetical

2) morphological

3) semantic

1. Phonetical motivation is used when there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word. For example: buzz, cuckoo, gigle. The sounds of a word are imitative of sounds in nature, or smth that produces a characteristic sound. This type of motivation is determined by the phonological system of each language.

2. Morphological motivation – the relationship between morphemic structure and meaning. The main criterion in morphological motivation is the relationship between morphemes. One-morphemed words are non-motivated. Ex – means «former» when we talk about humans ex-wife, ex-president. Re – means «again»: rebuild, rewrite. In borowed words motivation is faded: «expect, export, recover (get better)». Morphological motivation is especially obvious in newly coined words, or in the words created in this century. In older words motivation is established etymologically.

The structure-pattern of the word is very important too: «finger-ring» and «ring-finger». Though combined lexical meaning is the same. The difference of meaning can be explained by the arrangement of the components.

Morphological motivation has some irregularities: «smoker» – si not «the one who smokes», it is «a railway car in which passenger may smoke».

The degree of motivation can be different:

«endless» is completely motivated

«cranberry» is partially motivated: morpheme «cran-» has no lexical meaning.

3. Semantic motivation is based on the co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word within the same synchronous system. «Mouth» denotes a part of the human face and at the same time it can be applied to any opening: «the mouth of a river». «Ermine» is not only the anme of a small animal, but also a fur. In their direct meaning «mouth» and «ermine» are not motivated.

In compound words it is morphological motivation when the meaning of the whole word is based on direct meanings of its components and semantic motivation is when combination of components is used figuratively. For example «headache» is «pain in the head» (morphological) and «smth. annoying» (sematic).

When the connection between the meaning of the word and its form is conventional (there is no perceptible reason for the word having this phonemic and morphemic composition) the word is non-motivated (for the present state of language development). Words that seem non-motivated now may have lost their motivation: «earn» is derived from «earnian – to harvest», but now this word is non-motivated.

As to compounds, their motivation is morphological if the meaning of the whole is based on the direct meaning of the components, and semantic if the combination is used figuratively: watchdog – a dog kept for watching property (morphologically motivated); – a watchful human guardian (semantically motivated).

Every vocabulary is in a state of constant development. Words that seem non-motivated at present may have lost their motivation. When some people recognize the motivation, whereas others do not, motivation is said to be faded.

Semantically all word-groups may be classified into motivated and non-motivated. Non-motivated word-groups are usually described as phraseological units or idioms.

Word-groups may be described as lexically motivated if the combined lexical meaning of the groups is based on the meaning of their components. Thus take lessons is motivated; take place – ‘occur’ is lexically non-motivated.

Word-groups are said to be structurally motivated if the meaning of the pattern is deduced from the order and arrangement of the member-words of the group. Red flower is motivated as the meaning of the pattern quality – substance can be deduced from the order and arrangement of the words red and flower, whereas the seemingly identical pattern red tape (‘official bureaucratic methods’) cannot be interpreted as quality – substance.

Seemingly identical word-groups are sometimes found to be motivated or non-motivated depending on their semantic interpretation. Thus apple sauce, e.g., is lexically and structurally motivated when it means ‘a sauce made of apples’ but when used to denote ‘nonsense’ it is clearly non-motivated

Word-groups like words may be also analyzed from the point of view of their motivation. Word-groups may be called as lexically motivated if the combined lexical meaning of the group is deducible from the meaning of the components. All free phrases are completely motivated.

It follows from the above discussion that word-groups may be also classified into motivated and non-motivated units. Non-motivated word-groups are habitually described as phraseological units or idioms.

Investigations of English phraseology began not long ago. English and American linguists as a rule are busy collecting different words, word-groups and sentences which are interesting from the point of view of their origin, style, usage or some other features. All these units are habitually described as «idioms», but no attempt has been made to describe these idioms as a separate class of linguistic units or a specific class of word-groups.

Difference in terminology («set-phrases», «idioms» and «word-equivalents») reflects certain differences in the main criteria used to distinguish types of phraseological units and free word-groups. The term «set phrase» implies that the basic criterion of differentiation is stability of the lexical components and grammatical structure of word-groups.

There is a certain divergence of opinion as to the essential features of phraseological units as distinguished from other word-groups and the nature of phrases that can be properly termed «phraseological units». The habitual terms «set-phrases», «idioms», «word-equivalents» are sometimes treated differently by different linguists. However these terms reflect to certain extend the main debatable points of phraseology which centre in the divergent views concerning the nature and essential features of phraseological units as distinguished from the so-called free word-groups.

The term «set expression» implies that the basic criterion of differentiation is stability of the lexical components and grammatical structure of word-groups.

The term «word-equivalent» stresses not only semantic but also functional inseparability of certain word-groups, their aptness to function in speech as single words.

The term «idioms» generally implies that the essential feature of the linguistic units under consideration is idiomaticity or lack of motivation. Uriel Weinreich expresses his view that an idiom is a complex phrase, the meaning of which cannot be derived from the meanings of its elements. He developed a more truthful supposition, claiming that an idiom is a subset of a phraseological unit. Ray Jackendoff and Charles Fillmore offered a fairly broad definition of the idiom, which, in Fillmore’s words, reads as follows: «…an idiomatic expression or construction is something a language user could fail to know while knowing everything else in the language». Chafe also lists four features of idioms that make them anomalies in the traditional language unit paradigm: non-compositionality, transformational defectiveness, ungrammaticality and frequency asymmetry.

Great work in this field has been done by the outstanding Russian linguist A. Shakhmatov in his work «Syntax». This work was continued by Acad. V.V. Vinogradov. Great investigations of English phraseology were done by Prof. A. Cunin, I. Arnold and others.

Phraseological units are habitually defined as non-motivated word-groups that cannot be freely made up in speech but are reproduced as ready-made units; the other essential feature of phraseological units is stability of the lexical components and grammatical structure.

Unlike components of free word-groups which may vary according to the needs of communication, member-words of phraseological units are always reproduced as single unchangeable collocations. E.g., in a red flower (a free phrase) the adjective red may be substituted by another adjective denoting colour, and the word-group will retain the meaning: «the flower of a certain colour».

In the phraseological unit red tape (bürokratik metodlar) no such substitution is possible, as a change of the adjective would cause a complete change in the meaning of the group: it would then mean «tape of a certain colour». It follows that the phraseological unit red tape is semantically non-motivated, i.e. its meaning cannot be deduced from the meaning of its components, and that it exists as a ready-made linguistic unit which does not allow any change of its lexical components and its grammatical structure.

Grammatical structure of phraseological units is to a certain degree also stable:

red tape – a phraseological unit;

red tapes – a free word-group;

to go to bed – a phraseological unit;

to go to the bed – a free word-group.

Still the basic criterion is comparative lack of motivation, or idiomaticity of the phraseological units. Semantic motivation is based on the coexistence of direct and figurative meaning.

Taking into consideration mainly the degree of idiomaticity phraseological units may be classified into three big groups. This classification was first suggested by Acad. V.V. Vinogradov. These groups are:

– phraseological fusions,

– phraseological unities,

– phraseological collocations, or habitual collocations.

Phraseological fusions are completely non-motivated word-groups. Themeaning of the components has no connection at least synchronically with the meaning of the whole group. Idiomaticity is combined with complete stability of the lexical components and the grammatical structure of the fusion.

Phraseological unities are partially non-motivated word-groups as their meaning can usually be understood through (deduced from) the metaphoric meaning of the whole phraseological unit.

Phraseological unities are usually marked by a comparatively high degree of stability of the lexical components and grammatical structure. Phraseological unities can have homonymous free phrases, used in direct meanings.

§ to skate on thin ice – to skate on thin ice (to risk);

§ to wash one’s hands off dirt – to wash one’s hands off (to withdraw from participance);

§ to play the first role in the theatre – to play the first role (to dominate).

There must be not less than two notional wordsin metaphorical meanings.

Phraseological collocations are partially motivated but they are made up of words having special lexical valency which is marked by a certain degree of stability in such word-groups. In phraseological collocations variability of components is strictly limited. They differ from phraseological unities by the fact that one of the components in them is used in its direct meaning, the other – in indirect meaning, and the meaning of the whole group dominates over the meaning of its components. As figurativeness is expressed only in one component of the phrase it is hardly felt.

§ to pay a visit, tribute, attention, respect;

§ to break a promise, a rule, news, silence;

§ to meet demands, requirement, necessity;

§ to set free; to set at liberty;

§ to make money, journey;

§ to fall ill.

The structure V + N (дополнение) is the largest group of phraseological collocations.

Phraseological units may be defined as specific word-groups functioning as word-equivalents; they are equivalent to definite classes of words. The part-of-speech meaning of phraseological units is felt as belonging to the word-group as a whole irrespective of the part-of-speech meaning of component words. Comparing a free word-group, e.g. a long day and a phraseological unit, e.g. in the long run, we observe that in the free word-group the noun day and the adjective long preserve the part-of-speech meaning proper to these words taken in isolation. The whole group is viewed as composed of two independent units (A + N). In the phraseological unit in the long run the part-of-speech meaning belongs to the group as a single whole. In the long run is grammatically equivalent to single adverbs, e.g. finally, firstly, etc.

So, phraseological units are included into the system of parts of speech.

Phraseological units are created from free word-groups. But in the course of time some words – constituents of phraseological units may drop out of the language; the situation in which the phraseological unit was formed can be forgotten, motivation can be lost and these phrases become phraseological fusions.

The vocabulary of a language is enriched not only by words, but also by phraseological units. Phraseological units are word-groups that cannot be made in the process of speech, they exist in the language as ready-made units. They are compiled in special dictionaries. The same as words phraseological units express a single notion and are used in a sentence as one part of it. American and British lexicographers call such units «idioms». We can mention such dictionaries as: L. Smith «Words and Idioms», V. Collins «A Book of English Idioms» etc. In these dictionaries we can find words, peculiar in their semantics (idiomatic), side by side with word-groups and sentences. In these dictionaries they are arranged, as a rule, into different semantic groups.

Phraseological units can be classified according to the ways they are formed, according to the degree of the motivation of their meaning, according to their structure and according to their part-of-speech meaning.

A.V. Koonin classified phraseological units according to the way they are formed. He pointed out primary and secondary ways of forming phraseological units.

Among two-top units A.I. Smirnitsky points out the following structural types:

a) attributive-nominal such as: a month of Sundays, grey matter, a millstone round one’s neck and many others. Units of this type are noun equivalents and can be partly or perfectly idiomatic. In partly idiomatic units (phrasisms) sometimes the first component is idiomatic, e.g. high road, in other cases the second component is idiomatic, e.g. first night. In many cases both components are idiomatic, e.g. red tape, blind alley, bed of nail, shot in the arm and many others.

b) verb-nominal phraseological units, e.g. to read between the lines, to speak BBC, to sweep under the carpet etc. The grammar centre of such units is the verb, the semantic centre in many cases is the nominal component, e.g. to fall in love. In some units the verb is both the grammar and the semantic centre, e.g. not to know the ropes. These units can be perfectly idiomatic as well, e.g. to burn one’s boats, to vote with one’s feet, to take to the cleaners’ etc.

Very close to such units are word-groups of the type to have a glance, to have a smoke. These units are not idiomatic and are treated in grammar as a special syntactical combination, a kind of aspect.

c) phraseological repetitions, such as: now or never, part and parcel, country and western etc. Such units can be built on antonyms, e.g. ups and downs, back and forth; often they are formed by means of alliteration, e.g cakes and ale, as busy as a bee. Components in repetitions are joined by means of conjunctions. These units are equivalents of adverbs or adjectives and have no grammar centre. They can also be partly or perfectly idiomatic, e.g. cool as a cucumber (partly), bread and butter (perfectly).

Phraseological units the same as compound words can have more than two tops (stems in compound words), e.g. to take a back seat, a peg to hang a thing on, lock, stock and barrel, to be a shadow of one’s own self, at one’s own sweet will.

Phraseological units can be classified as parts of speech. This classification was suggested by I.V. Arnold. Here we have the following groups:

a) noun phraseologisms denoting an object, a person, a living being, e.g. bullet train, latchkey child, redbrick university, Green Berets,

b) verb phraseologisms denoting an action, a state, a feeling, e.g. to break the log-jam, to get on somebody’s coattails, to be on the beam, to nose out, to make headlines,

c) adjective phraseologisms denoting a quality, e.g. loose as a goose, dull as lead

d) adverb phraseological units, such as: with a bump, in the soup, like a dream, like a dog with two tails,

e) preposition phraseological units, e.g. in the course of, on the stroke of,

f) interjection phraseological units, e.g. «Catch me!», «Well, I never!» etc.

In I.V. Arnold’s classification there are also sentence equivalents, proverbs, sayings and quotations, e.g. «The sky is the limit», «What makes him tick», «I am easy». Proverbs are usually metaphorical, e.g. «Too many cooks spoil the broth», while sayings are as a rule non-metaphorical, e.g. «Where there is a will there is a way».

Теги:

Free word groups. Phraseological units

Контрольная работа

Английский

Просмотров: 27100

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Free word groups. Phraseological units

Lecture № 6. Free Word-groups. Stylistically Marked and Stylistically Neutral Words

Every utterance is a patterned, rhymed and segmented sequence of signals. On the lexical level these signals building up the utterance are not exclusively words. Alongside this separate words speakers use larger blocks consisting of more than one word. Words combined to express ideas and thoughts make up word-groups. The degree of structural and semantic cohesion of words within word-groups may vary. Some word-groups are functionally and semantically inseparable: rough diamond, cooked goose. Such word-groups are traditionally described as set-phrases or phraseological units. Characteristic features of phraseological units are non-motivation for idiomaticity and stability of context. They cannot be freely made up in speech but are reproduced as ready-made units. The component members in other word-groups possess greater semantic and structural independence: to cause misunderstanding, to shine brightly, linguistic phenomenon, red rose. Word-groups of this type are denned as free word-groups for free phrases. They are freely made up in speech by the speakers according to the needs of communication. Set expressions are contrasted to free phrases and semi-fixed combinations. All these different stages of restrictions imposed upon co-occurrence of words, upon the lexical filling of structural patterns which are specific for every language. The restriction may be independent of the ties existing in extra-linguistic reality between the object spoken of and be conditioned by purely linguistic factors, or have extralinguistic causes in the history of the people. In free word-combination the linguistic factors are chiefly connected with grammatical properties of words.

Free word-group is a group of syntactically connected notional words within a sentence, which by itself is not a sentence. This definition is recognized more or less universally in this country and abroad. Though Other linguistics define the term word-group differently — as any group of words connected semantically and grammatically which does not make up a sentence by itself. From this point of view words-components of a word-group may belong to any part of speech, therefore such groups as in the morning, the window, and Bill are also considered to be word-groups (though they comprise only one notional word and one form-word).

STRUCTURE OF FREE WORD-GROUPS

Structurally word-groups may be approached in various ways. All word-groups may be analysed by the criterion of distribution into two big classes. Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit can be used. If the word-group has the same linguistic distribution as one of its members, it is described as endocentric i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group. The word-groups red flower, bravery of all kinds, are distributionally identical with their central components flower and braver, cf: I saw a red flower — 1 saw a flower; I appreciate bravery of all kinds — I appreciate bravery. If the distribution of the word-group is different from either of its members, it is regarded as exocentric i.e. as having no such central member, for instance side by side or grow smaller and others where the component words are not syntactically substitutable for the whole word-group. In endocentric word-groups the central component that has the same distribution as the whole group is clearly the dominant member or the head to which all other members of the group are subordinated, in the word-group red flower the head is the noun flower and in the word-group kind of people the head is the adjective kind.

Word-groups are also classified according to their syntactic pattern into predicative and non-predicative groups. Such word-groups, e.g. John works, he went that have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence, are classified as predicative, and all others as non-predicative. Non-predicative word-groups may be subdivided according to the type of syntactic relation between the components into subordinate and coordinative. Such word-groups as red flower, a man of wisdom and the like are termed subordinate in which flower and man are head-words and red, of wisdom are subordinated to them respectively and function as their attributes. Such phrases as woman and child, day and night, do or die are classified as coordinative. Both members in these word-groups are functionally and semantically equal. Subordinate word-groups may be classified according to their head-words into nominal groups (red flower), adjectival groups (kind to people), verbal groups (to speak well), pronominal (all of them). The head is not necessarily the component that comes first in the word-group. In such nominal word-groups as very great bravery, bravery in the struggle the noun bravery is the head whether followed or preceded by other words.

MEANING OF FREE WORD-GROUPS. INTERRELATION OF STRUCTURAL AND LEXICAL MEANINGS IN WORD-GROUPS. MOTIVATION IN WORD-GROUPS

The meaning of word-groups may be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the components. The lexical meaning of the word-group may be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the component words. Thus the lexical meaning of the word-group red flower may be described denotationally as the combined meaning of the words red and flower. It should be pointed out, however, that the term combined lexical meaning is not to imply that the meaning of the word-group is a mere additive result of all the lexical meaning of the component members. As a rule, the meaning of the component words are mutually dependant and the meaning of the word-group naturally predominates over the lexical meanings of its constituents.

Word-groups possess not only the lexical meaning, but also the meaning conveyed by the pattern of arrangement of their constituent’s. Such word groups as school grammar and grammar school are semantically different because of the difference in the pattern of arrangement of the component words. It is assumed that the structural pattern of word-group is the carrier of a certain semantic component which does not necessarily depend on the actual lexical meaning of its members. In the example discussed above school grammar the structural meaning of the word-group may be abstracted from the group and described as equality-substance meaning. This is the meaning expressed by the pattern of the word-group but not by either the word school or the word grammar. It follows that we have to distinguish between the structural meaning of a given type of word-group as such and the lexical meaning of its constituents.

The lexical and structural meaning in word-groups are interdependent and inseparable. The inseparability of these two semantic components in word-groups can be illustrated by the semantic analysis of individual word-groups in which the norms of conventional collocability of words seem to be deliberately overstepped. For instance, in the word-group all the sun long we observe a departure from the norm of lexical valency represented by such word-groups as all the day long, all the night long, all the week long, etc. The structural pattern of these word-groups in ordinary usage and the word-group all the sun long is identical. The generalized meaning of the pattern may be described as “a unit of time”. Replacing day, night, week by another noun the sun we do not find any change in the structural meaning of the pattern. The group all the sun long functions semantically as a unit of time. The noun sun, however, included in the group continues to carry its own lexical meaning (not “a unit of time”) which violates the norms of collocability in this word-group. It follows that the meaning of the word-group is derived from the combined lexical meanings of its constituents and is inseparable from the meaning of the pattern of their arrangement. Word-groups may be also analyzed from the point of view of their motivation. Word groups may be described as lexically motivated if the combined lexical meaning of the group is deducible from the meaning of its components. The degrees of motivation may be different and range from complete motivation to lack of it. Free word-groups, however, are characterized by complete motivation, as their components carry their individual lexical meanings. Phraseological units are described as non-motivated and are characterized by different degree of idiomaticity.

LEXICAL AND GRAMMATICAL VALENCY

Two basic linguistic factors which unite words into word-groups and which largely account for their combinability are lexical valency or collocability and grammatical valency. Words are known to be used in lexical context, i.e. in combination with other words. The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations, with other words is qualified as its lexical collocability or valency. The range of a potential lexical collocability of words is restricted by the inner structure of the language wordstock, This can be easily observed in the examples, as follows: though the words bend, curl are registered by the dictionaries as synonyms their collocability is different, for they tend to combine with different words, cf: to bend a wire/pipe/stick/head/knees; to curl hair/moustache/lips. There can be cases of synonymic groups where one synonym would have the widest possible range of collocability (like shake which enters combinations with an immense number of words including earth, air, mountains, beliefs, spears, walls, souls, tablecloths, carpets etc.) while another will have the limitation inherent in its semantic structure (like wag — to shake a thing by one end, and confined to rigid group of nouns – tail, finger, head, tongue, beard, chin). There is certain norm of lexical valency for each word and any intentional departure from this norm is qualified as a stylistic device, cf: tons of words, a life ago. Words traditionally collocated in speech tend to make up so called cliches or traditional word combinations. In traditional combinations words retain their full semantic independence although they are limited in their combinative power: to wage a war, to render a service, to make friends. Words in traditional combinations are combined according to the patterns of grammatical structure of the given language. Traditional combinations fall into the following structural types:

1 V+N combinations: deal a blow, bear a grudge, take a fancy etc.

-

V+prep+N: fall into disgrace, take into account, come into being etc.

-

V+Adj: work hard, rain heavily etc.

-

V+Adj: set free, make sure, put right etc.

-

Adj+N: maiden voyage, dead silence, feline eyes, aquiline nose etc.

-

N+V: time passes/flies, tastes vary etc.

7. N+prep+N: breach of promise, flow of words, flash of hope, flood of tears etc. Grammatical combinability also tells upon the freedom of bringing words together. The aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (syntactic) structures is termed grammatical valency. The grammatical valency of words may be different. The range of it is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This statement, though, does not entitle to say that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is identical. Thus, the two synonyms clever and intelligent are said to posses different grammatical valency as the word clever can fit the syntactic pattern of Adj+prep at+N clever at physics, clever at social sciences, whereas the word intelligent can never be found in exactly the same syntactic pattern. Unlike, frequent departures from the norms of lexical valency, departures from the grammatical valency norms are not admissible unless a speaker purposefully wants to make the word group unintelligible to native speakers.

FUNCTIONAL STYLES