The

vocabulary of a language includes not only words but also stable word

combinations which also serve as a means of expressing concepts. They

are phraseological word equivalents reproduced in speech the way

words are reproduced and not created anew in actual speech.

An

ordinary word combination is created according to the grammatical

rules of the language in accordance with a certain idea. The general

meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the

conjoined meanings of its elements. Every notional word functions

here as a certain member of the sentence. Thus, an ordinary word

combination is a syntactical pattern.

A

free word combination is a combination in which any element can be

substituted by another.

e.g.:

I

like this idea. I dislike this idea. He likes the idea. I like that

idea. I like this thought.

But

when we use the term free we are not precise. The freedom of a word

in a combination with others is relative as it is not only the

syntactical pattern that matters. There are logical limitations too.

The

second group of word combinations is semi-free word combinations.

They are the combinations in which the substitution is possible but

limited.

e.g.:

to

cut a poor/funny/strange figure.

Non-free

word combinations are those in which the substitution is impossible.

e.g.:

to

come clean, to be in low water.

2. Classifications of Phraseological Units

A

major stimulus to intensive studies of phraseology was prof.

Vinogradov’s research. The classification suggested by him has been

widely adopted by linguists working on other languages. The

classification of phraseological units suggested by V.V.

Vinogradov

includes:

—

standardised word combinations, i.e. phrases characterised by the

limited combinative power of their components, which retain their

semantic independence: to

meet the request/requirement,

подавати надію, страх бере, зачепити

гордість, покласти край;

—

phraseological unities, i.e. phrases in which the meaning of the

whole is not the sum of meanings of the components but it is based on

them and the motivation is apparent: to

stand to one’s guns,

передати куті меду, прикусити язика,

вивести на чисту воду, тримати камінь

за пазухою;

—

fusions, i.e. phrases in which the meaning cannot be derived as a

whole from the conjoined meanings of its components:

tit

for tat,

теревені правити, піймати облизня,

викинути коника, у Сірка очі позичити.

Phraseological

unities are very often metaphoric. The components of such unities are

not semantically independent, the meaning of every component is

subordinated to the figurative meaning of the phraseological unity as

a whole. The latter may have a homonymous expression — a free

syntactical word combination.

e.g.:

Nick

is a musician. He plays the first fiddle.

It

is his wife who plays the first fiddle in the house.

Phraseological

unities may vary in their semantic and grammatical structure. Not all

of them are figurative. Here we can find professionalisms, coupled

synonyms.

A.V.

Koonin

finds it necessary to divide English phraseological unities into

figurative and non-figurative.

Figurative

unities are often related to analogous expressions with direct

meaning in the very same way in which a word used in its transferred

sense is related to the same word used in its direct meaning.

Scientific

English, technical vocabulary, the vocabulary of arts and sports have

given many expressions of this kind: in

full blast; to hit below the belt; to spike smb’s guns.

Among

phraseological unities we find many verb-adverb combinations: to

look for; to look after; to put down; to give in.

Phraseological

fusions are the most synthetical of all the phraseological groups.

They seem to be completely unmotivated though their motivation can be

unearthed by means of historic analysis.

They

fall under the following groups:

Idiomatic

expressions which are associated with some obsolete customs: the

grey mare, to rob Peter to pay Paul.

Idiomatic

expressions which go back to some long forgotten historical facts

they were based on: to bell the cat, Damocles’ sword.

Idiomatic

expressions expressively individual in their character: My

God! My eye!

Idiomatic

expressions containing archaic elements: by

dint of (dint – blow); in fine (fine – end).

Semantic

Classification of Phraseological Units

1.

Phraseological units referring to the same notion.

e.g.:

Hard

work — to burn the midnight oil; to do back-breaking work; to hit the

books; to keep one’s nose to the grindstone; to work like a dog; to

work one’s fingers to the bone.

Compromise

– to find middle ground; to go halfway.

Independence

– to be on one’s own; to have a mind of one’s own; to stand on

one’s own two feet.

Experience

– to be an old hand at something; to know something like the back

of one’s palm; to know the rope.Ледарювати

– байдики бити, ханьки м’яти, ганяти

вітер по вулицях, тинятися з кутка в

куток, і за холодну воду не братися.

2.

Professionalisms

e.g.:

on

the rocks; to stick to one’s guns; breakers ahead. 3.

Phraseological units having similar components

e.g.:

a

dog in the manger; dog days; to agree like cat and dog; to rain cats

and dogs. To fall on deaf ears; to talk somebody’s ear off; to have

a good ear for; to be all ears. To see red; a red herring; a red

carpet treatment; to be in the red;

з перших рук; як без рук; горить у руках;

не давати волі рукам.

4.

Phraseological units referring to the same lexico-semantic field.

e.g.:

Body

parts – to cost an arm and leg; to pick somebody’s brain; to get

one’s feet wet; to get off the chest; to rub elbows with; not to

have a leg to stand on; to stick one’s neck out; to be nosey; to

make a headway; to knuckle down; to shake a leg; to pay through the

noser; to tip toe around; to mouth off;

без клепки в голові; серце з перцем;

легка рука.

Fruits

and vegetables –

red as a beet; a couch potato; a hot potato; a real peach; as cool as

a cucumber; a top banana;гриби

після дощу; як горох при дорозі; як

виросте гарбуз на вербі.

Animals

– sly

as a fox; to be a bull in a china shop; to go ape; to be a lucky dog;

to play cat and mouse;

як з гуски вода, як баран на нові ворота;

у свинячий голос; гнатися за двома

зайцями.

Structural

Classification of Phraseological Units

Еnglish

phraseological units can function like verbs (to

drop a brick; to drop a line; to go halves; to go shares; to travel

bodkin),

phraseological units functioning like nouns (brains

trust, ladies’ man,

phraseological units functioning like adjectives (high

and dry,

high

and low,ill at ease,

phraseological units functioning like adverbs (tooth

and nail, on

guard;

by heart,

phraseological units functioning like prepositions (in

order to; by virtue

of),

phraseological units functioning like interjections (Good

heavens! Gracious me! Great Scot!).

Ukrainian

phraseological

units

can

function

like

nouns

(наріжний

камінь, біла ворона, лебедина пісня),

adjectives

(

не з полохливого десятка, не остання

спиця в

колесі,

білими нитками шитий),

verbs

(

мотати на вус, товкти воду в ступі,

ускочити

в

халепу),

adverbs

(

не чуючи землі під ногами, кров холоне

в жилах, ні в зуб ногою), interjections

(цур тобі, ні пуху ні пера, хай йому

грець).

Another

structural classification was initiated by A.V. Koonin. He singles

out Nominative, Nominative and Nominative-Communicative,

Interjective, Communicative phraseological units.

Nominative

phraseological units are of several types. It depends on the type of

dependence. The first one is phraseological units with constant

dependence of the elements.

e.g.:

the

Black Maria; the ace of trumps; a spark in the powder magazine.

The

second type is represented by the phraseological units with the

constant variant dependence of the elements.

e.g.:

dead

marines/men; a blind pig/tiger; a good/great deal.

There

also exist phraseological units with grammar variants.

e.g.:

Procrustes’

bed = the Procrustean bed = the bed of Procrustes.

Another

type of the Nominative phraseological units is units with

quantitative variants. They are formed with the help of the reduction

or adding the elements.

e.g.:

the

voice of one crying in the wilderness = a voice crying out in the

wilderness= a voice crying in the wilderness = a voice in the

wilderness.

The

next type of the Nominative phraseological units is adjectival

phraseological units.

e.g.:

mad

as a hatter; swift as thought; as like as two peas; fit as a fiddle.

The

function of the adverbial phraseological units is that of an

adverbial modifier of attendant circumstances.

e.g.:

as

cool as a cucumber; from one’s cradle to one’s grave; from pillar

to post; once in a blue moon.

Nominative

and Nominative-Communicative phraseological units are of several

types as well. The first type is verbal phraseological units. Verbal

phraseological units refer to this type in such cases: a) when the

verb is not used in the Passive voice (

to drink

like

a fish; to buy a pig in a poke; to close one’s eyes on something

; b) if the verb is not used in the Active voice (to

be reduced to a shadow; to be gathered to one’s fathers).

Nominative

and Nominative-Communicative phraseological units can have lexical

variants.

e.g.:

to

tread/walk on air; to close/shut books; to draw a red herring across

the trail/track; to come to a fine/handsome/nice/pretty pass; to sail

close/near to the wind; to crook/lift the elbow/the little finger.

Grammar

variants are also possible.

e.g.:

to

get into deep water = to get into deep waters; to pay nature’s debt

= to pay the debt of nature.

Examples

of quantitative variants can also be found: to

cut the Gordian knot = to cut the knot; to lead somebody a dance = to

lead somebody a pretty dance.

Lexico-grammar

variants are also possible: to

close/shut a /the door/doors on/upon/to somebody.

Interjective

phraseological units are represented by: by

George! By Jove! Good heavens! Gracious me!

Communicative

phraseological units are represented by proverbs and sayings.

e.g.:

Rome

was not built in a day. An apple a day keeps a doctor away. That’s

another pair of shoes. More power to your elbow. Carry me out.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

LECTURE 13.

PHRASEOLOGY: PRINCIPLES OF CLASSIFICATION

1) Free word-groups versus phraseological units versus words

a) Structural Criterion

b) Semantic criterion

c) Syntactic Criterion

2) Semantic structure of phraseological units

3) Types of transference of phraseological units

4) Classifications of phraseological units

a) Thematic principle of classification of phraseological units

b) Academician V.V. Vidogradov’s classification of phraseological units

c) Structural principle of classification of phraseological units

d) Professor Smirnitsky’s classification of phraseological units

e) Professor A.V. Koonin’s classification of phraseological units

f) Classification of phraseological units on the base of their origin

1. Free word-groups versus phraseological units versus words

A phraseological unit can be defined as a reproduced and idiomatic (non-motivaetd) or partially morivated unit built up according to the model of free word-groups (or sentences) and semantically and syntactically brought into correlation with words. Hence, there is a need for criteria exposing the degree of similarity / difference between phraseological units and free word-groups, phraseological units and words.

a) Structural Criterion

The structural criterion brings forth pronounced features which on the one hand state a certain structural similarity between phraseological units and free word-combinations at the same time opposing them to single words (1), and on the other hand specify their structural distinctions (2).

1) A feature proper both to free phrases and phraseological units is the divisibility (раздельнооформленность) of their structure, i.e. they consist of separate structural elements. This fact stands them in opposition to words as structurally integral (цельнооформленные) units. The structural integrity of a word is defined by the presence of a common grammatical form for all constituent elements of this word. For example, the grammatical change in the word shipwreck implies that inflexions are added to both elements of the word simultaneously — ship-wreck-( ), ship-wreck-s, while in the word-group the wreck of a ship each element can change its grammatical form independently from the other — (the) wreck-( ) of the ships, (the) wrecks of (the) ships. Like in word-groups, in phraseological units potentially any component may be changed grammatically, but these changes are rather few, limited and occasional and usually serve for a stylistic effect, e.g. a Black Maria ‘a van used by police for bringing suspected criminals to the police station’: the Blackest Maria, Black Marias.

2) The principal difference between phraseological units and free word-groups manifests itself in the structural invariability of the former. The structural invariability suggests no (or rather limited) substitutions of components. For example, to give somebody the cold shoulder means ‘to treat somebody coldly, to ignore or cut him’, but a warm shoulder or a cold elbow makes no sense. There are also strict restrictions on the componental extension and grammatical changes of components of phraseological units. The use of the words big, great in a white elephant meaning ‘an expensive but useless thing’ can change or even destroy the meaning of the phraseological unit. The same is true if the plural form feet in the phraseological unit from head to foot is used instead of the singular form. In a free word-group all these changes are possible.

b) Semantic criterion

The semantic criterion is of great help in stating the semantic difference/similarity between free word-groups and phraseological units, (1), and between phraseological units and words (2).

1) The meaning in phraseological units is created by mutual interaction of elements and conveys a single concept. The actual meaning of a phraseological unit is figurative (transferred) and is opposed to the literal meaning of a word-combination from which it is derived. The transference of the initial word-group can be based on simile, metaphor, metonymy, and synecdoche. The degree of transference varies and may affect either the whole unit or only one of its constituents, cf.: to skate on thin ice – ‘to take risks’; the small hours — ‘the early hours of the morning’. Besides, in the formation of the semantic structure of phraseological units a cultural component plays a special and very important role. It marks phraseological units as bearers of cultural information based on a unique experience of the nation. For example, the phraseological unit red tape originates in the old custom of Government officials and lawyers tying up (перевязывать) their papers with red tape. Heads or tails comes from the old custom of deciding a dispute or settling which of two possible alternatives shall be followed by tossing a coin (heads refers to the sovereign’s head on one side of the coin, and tails means the reverse side).

In a free phrase the semantic correlative ties are fundamentally different. The meaning in a word-group is based on the combined meaning of the words constituting its structure. Each element in a word-combination has a much greater semantic independence and stands for a separate concept, e.g. to cut bread, to cut cheese, to eat bread. Every word in a free phrase can form additional syntactic ties with other words outside the expression retaining its individual meaning.

2) The semantic unity, however, makes phraseological units similar to words. The semantic similarity between the two is proved by the fact that, for instance, kick the bucket whose meaning is understood as a whole and not related to the meaning of individual words can be replaced within context by the word to die, the phraseological unit in a brown study – by the word gloomy.

c) Syntactic Criterion

The syntactic criterion reveals the close ties between single words and phraseological units as well as free word-groups. Like words (as well as word-combinations), phraseological units may have different syntactic functions in the sentence, e.g. the subject (narrow escape, first night, baker’s dozen), the predicate (to have a good mind, to play Russian roulette, to make a virtue of necessity), an attribute (high and mighty, quick on the trigger, as ugly as sin), an adverbial (in full swing, on second thoughts, off the record). In accordance with the function they perform in the sentence phraseological units can be classified into: substantive, verbal, adjectival, adverbial, interjectional.

Like free word-groups phraseological units can be divided into coordinative (e.g. the life and soul of something, free and easy, neck and crop) and subordinative (e.g. long in the tooth, a big fish in a little pond, the villain of the piece).

Thus, the characteristic features of phraseological units are: ready-made reproduction, structural divisibility, morphological stability, permanence of lexical composition, semantic unity, syntactic fixity.

2. Semantic structure of phraseological units

The semantic structure of phraseological units is formed by semantic ultimate constituents called macrocomponents of meaning. The macrocomponental model of phraseological meaning was worked out by V.N. Teliya. There are the following principal macrocomponents in the semantic structure of phraseological units:

1. Denotational (descriptive) macrocomponent that contains the information about the objective reality, it is the procedure connected with categorization, i.e. the classification of phenomena of the reality, based on the typical idea about what is denoted by a phraseological unit, i.e. about the denotatum.

2. Evaluational macrocomponent that contains information about the value of what is denoted by a phraseological unit, i.e. what value the speaker sees in this or that object/phenomenon of reality – the denotatum. The rational evaluation may be positive, negative and neutral, e.g. a home from home – ‘a place or situation where one feels completely happy and at ease’ (positive), the lion’s den — ‘a place of great danger’ (negative), in the flesh — ‘in bodily form’ (neutral). Evaluation may depend on empathy (i.e. a viewpoint) of the speaker/ hearer.

3. Motivational macrocomponent that correlates with the notion of the inner form of a phraseological unit, which may be viewed as the motif of transference, the image-forming base, the associative-imaginary complex, etc. The notion ‘motivation of a phraseological unit’ can be defined as the aptness of ‘the literal reading’ of a unit to be associated with the denotational and evaluational aspects of meaning. For example, the literal reading of the phraseological unit to have broad shoulders evokes associations connected with physical strength of a person. The idea that broad shoulders are indicative of a person’s strength and endurance actualizes, becomes the base for transference and forms the following meaning: ‘to be able to bear the full weight of one’s responsibilities’.

4. Emotive macrocomponent that is the contents of subjective modality expressing feeling-relation to what is denoted by a phraseological unit within the range of approval/disapproval, e.g. a leading light in something —‘a person who is important in a particular group’ (spoken with approval), to lead a cat and dog life — ‘used to describe a husband and wife who quarrel furiously with each other most of the time’ (spoken with disapproval). Emotiveness is also the result of interpretation of the imaginary base (образное основание) in a cultural aspect.

5. Stylistic macrocomponent that points to the communicative register in which a phraseological unit is used and to the social-role relationships between the participants of communication, e.g. sick at heart — ‘very sad’ (formal), be sick to death —‘to be angry and bored because something unpleasant has been happening for too long’ (informal), pass by on the other side — ‘to ignore a person who needs help’ (neutral).

6. Grammatical macrocomponent that contains the information about all possible morphological and syntactic changes of a phraseo¬logical unit, e.g. to be in deep water = to be in deep waters; to take away smb’s breath = to take smb’s breath away; Achilles’ heel = the heel of Achilles.

7. Gender macrocomponent (was singled out by I.V. Zykova) that may be expressed explicitly, i.e. determined by the structure and/or semantics of a phraseological unit, and in that case it points out to the class of objects denoted by the phraseological unit: men, women, people (both men and women). For example, compare the phraseological units every Tom, Dick and Harry meaning ‘every or any man’ and every Tom, Dick and Sheila which denotes ‘every or any man and woman’. Gender macrocomponent may be expressed implicitly and then it denotes the initial (or historical) reference of a phraseological unit to the class of objects denoted by it which is as a rule stipulated by the historical development, traditions, stereotypes, cultural realia of the given society, e.g. to wash one’s dirty linen in public — ‘discuss or argue about one’s personal affairs in public’. The implicit presence of the gender macrocomponent in this phraseo- logical unit is conditioned by the idea about traditional women’s work (cf. with Russian: выносить cop из избы). Gender, implicitly as well as explicitly expressed, reveals knowledge about such cultural concepts as masculinity and femininity that are peculiar to this or that society. The implicit gender macrocomponent is defined within the range of three conceptual spheres: masculine, feminine, intergender. Compare, for instance, the implicitly expressed intergender macrocomponent in to feel like royalty meaning ‘to feel like a member of the Royal Family, to feel majestic’ and its counterparts, i.e. phraseological units with explicitly expressed gender macrocomponent, to feel like a queen and to feel like a king.

3. Types of transference of phraseological units

Phraseological transference is a complete or partial change of meaning of an initial (source) word-combination (or a sentence) as a result of which the word-combination (or the sentence) acquires a new meaning and turns into a phraseological unit. Phraseological transference may be based on simile, metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, etc. or on their combination.

1) Transference based on simile is the intensification of some feature of an object (phenomenon, thing) denoted by a phraseological unit by means of bringing it into contact with another object (phenomenon, thing) belonging to an entirely different class. Compare the following English and Russian phraseological units: (as) pretty as a picture — хороша как картинка, (as) fat as a pig — жирный как свинья, to fight like a lion — сражаться как лев, to swim like a fish — плавать как рыба.

2) Transference based on metaphor is a likening (уподобление) of one object (phenomenon, action) of reality to another, which is associated with it on the basis of real or imaginable resemblance. For example, in the phraseological unit to bend somebody to one’s bow meaning ‘to submit someone’ transference is based on metaphor, i.e. on the likening of a subordinated, submitted person to a thing (bow) a good command of which allows its owner to do with it everything he wants to.

Metaphors can bear a hyperbolic character: flog a dead horse —‘waste energy on a lost cause or unalterable situation (букв, стегать дохлую лошадь). Metaphors may also have a euphemistic character which serves to soften unpleasant facts: go to one’s long rest, join the majority – ‘to die’.

3) Transference based on metonymy is a transfer of name (перенос наименования) from one object (phenomenon, thing, action, process, etc.) to another based on the contiguity of their properties, relations, etc’ The transfer of name is conditioned by close ties between the two objects, the idea about one object is inseparably linked with the idea about the other object. For example, the metonymical transference in the phraseological unit a silk stocking meaning ‘a rich, well-dressed man’ is based on the replacement of the genuine object (a man) by the article of clothing which was very fashionable and popular among men in the past.

4) Synecdoche is a variety of metonymy. Transference based on synecdoche is naming the whole by its part, the replacement of the common by the private, of the plural by the singular and vice versa. For example, the components flesh and blood in the phraseological unit in the flesh and blood meaning ‘in a material form’ as the integral parts of the real existence replace a person himself or any living being, see the following sentences: We’ve been writing to each other for ten years, but now he’s actually going to be here in the flesh and blood. Thousands of fans flocked to Dublin to see their heroes in the flesh and blood. Synecdoche is usually found in combination with other types of transference, e.g. metaphor: to hold one’s tongue — ‘to say nothing, to be discreet’.

4. Classifications of phraseological units

a) Thematic principle of classification of phraseological units

The traditional and oldest principle for classifying phraseological units is based on their original content and might be alluded to as «thematic» (although the term is not universally accepted). The approach is widely used in numerous English and American guides to idiom, phrase books, etc. On this principle, idioms are classified according to their sources of origin, ‘source’ referring to the particular sphere of human activity, of life of nature, of natural phenomena, etc. So, L. P. Smith gives in his classification groups of idioms used by sailors, fishermen, soldiers, hunters and associated with the realia, phenomena and conditions of their occupations. In Smith’s classification we also find groups of idioms associated with domestic and wild animals and birds, agriculture and cooking. There are also numerous idioms drawn from sports, arts, etc.

This principle of classification is sometimes called «etymological». The term does not seem appropriate since we usually mean something different when we speak of the etymology of a word or word-group: whether the word (or word-group) is native or borrowed, and, if the latter, what is the source of borrowing. It is true that Smith makes a special study of idioms borrowed from other languages, but that is only a relatively small part of his classification system. The general principle is not etymological.

Smith points out that word-groups associated with the sea and the life of seamen are especially numerous in English vocabulary. Most of them have long since developed metaphorical meanings which have no longer any association with the sea or sailors. Here are some examples.

To be all at sea — to be unable to understand; to be in a state of ignorance or bewilderment about something (e. g. How can I be a judge in a situation in which I am all at sea? I’m afraid I’m all at sea in this problem). V. H. Collins remarks that the metaphor is that of a boat tossed about, out of control, with its occupants not knowing where they are.

To sink or swim — to fail or succeed (e. g. It is a case of sink or swim. All depends on his own effort.)

In deep water — in trouble or danger.

In low water, on the rocks — in strained financial circumstances.

To be in the same boat with somebody — to be in a situation in which people share the same difficulties and dangers (e. g. I don’t like you much, but seeing that we’re in the same boat I’ll back you all I can). The metaphor is that of passengers in the life-boat of a sunken ship.

To sail under false colours — to pretend to be what one is not; sometimes, to pose as a friend and, at the same time, have hostile intentions. The metaphor is that of an enemy ship that approaches its intended prey showing at the mast the flag («colours») of a pretended friendly nation.

To show one’s colours — to betray one’s real character or intentions. The allusion is, once more, to a ship showing the flag of its country at the mast.

To strike one’s colours — to surrender, give in, admit one is beaten. The metaphor refers to a ship’s hauling down its flag (sign of surrender).

To weather (to ride out) the storm — to overcome difficulties; to have courageously stood against misfortunes.

To bow to the storm — to give in, to acknowledge one’s defeat.

Three sheets in(to) the wind (sl.) — very drunk.

Half seas over (sl.) — drunk.

The thematic principle of classifying phraseological units has real merit but it does not take into consideration the linguistic characteristic features of the phraseological units.

b) Academician V.V. Vidogradov’s classification of phraseological units

The classification system of phraseological units devised by V.V. Vinogradov is considered by some linguists of today to be outdated, and yet its value is beyond doubt because it was the first classification system which was based on the semantic principle. It goes without saying that semantic characteristics are of immense importance in phraseological units. It is also well known that in modern research they are often sadly ignored. That is why any attempt at studying the semantic aspect of phraseological units should be appreciated.

V.V. Vinogradov’s classification system is founded on the degree of semantic cohesion between the components of a phraseological unit. Units with a partially transferred meaning show the weakest cohesion between their components. The more distant the meaning of a phraseological unit from the current meaning of its constituent parts, the greater is its degree of semantic cohesion. Accordingly, V.V. Vinogradov classifies phraseological units according to the degree of idiomaticity. Here are three classes of phraseological units: phraseological fusions (сращения), phraseological unities (единства) and phraseological collocations (сочетания).

1) Phraseological combinations are word-groups with a partially changed meaning. They may be said to be clearly motivated, that is, the meaning of the unit can be easily deduced from the meanings of its constituents.

E. g. to be at one’s wits’ end, to be good at something, to be a good hand at something, to have a bite, to come off a poor second, to come to a sticky end (coll.), to look a sight (coll.), to take something for granted, to stick to one’s word, to stick at nothing, gospel truth, bosom friends.

2) Phraseological unities are word-groups with a completely changed meaning, that is, the meaning of the unit does not correspond to the meanings of its constituent parts. They are motivated units or, putting it another way, the meaning of the whole unit can be deduced from the meanings of the constituent parts; the metaphor, on which the shift of meaning is based, is clear and transparent.

E. g. to stick to one’s guns (~ to be true to one’s views or convictions. The image is that of a gunner or guncrew who do not desert their guns even if a battle seems lost); to sit on the fence (~ in discussion, politics, etc. refrain from committing oneself to either side); to catch/clutch at a straw/straws (~ when in extreme danger, avail oneself of even the slightest chance of rescue); to lose one’s head (~ to be at a loss what to do; to be out of one’s mind); to lose one’s heart to smb. (~ to fall in love); to lock the stable door after the horse is stolen (~ to take precautions too late, when the mischief is done); to look a gift horse in the mouth (= to examine a present too critically; to find fault with something one gained without effort); to ride the high horse (~ to behave in a superior, haughty, overbearing way. The image is that of a person mounted on a horse so high that he looks down on others); the last drop/straw (the final culminating circumstance that makes a situation unendurable); a big bug/pot, sl. (a person of importance); a fish out of water (a person situated uncomfortably outside his usual or proper environment).

3) Phraseological fusions are word-groups with a completely changed meaning but, in contrast to the unities, they are demotivated, that is, their meaning cannot be deduced from the meanings of the constituent parts; the metaphor, on which the shift of meaning was based, has lost its clarity and is obscure.

E. g. to come a cropper (to come to disaster); neck and crop (entirely, altogether, thoroughly, as in: He was thrown out neck and crop. She severed all relations with them neck and crop.); at sixes and sevens (in confusion or in disagreement); to set one’s cap at smb. (to try and attract a man; spoken about girls and women. The image, which is now obscure, may have been either that of a child trying to catch a butterfly with his cap or of a girl putting on a pretty cap so as to attract a certain person. In Vanity Fair: «Be careful, Joe, that girl is setting her cap at you.»); to leave smb. in the lurch (to abandon a friend when he is in trouble); to show the white feather (to betray one’s cowardice. The allusion was originally to cock fighting. A white feather in a cock’s plumage denoted a bad fighter); to dance attendance on smb. (to try and please or attract smb.; to show exaggerated attention to smb.).

c) Structural principle of classification of phraseological units

It is obvious that Acadimician V.V. Vinogradov’s classification system does not take into account the structural characteristics of phraseological units. On the other hand, the border-line separating unities from fusions is vague and even subjective. One and the same phraseological unit may appear motivated to one person (and therefore be labelled as a unity) and demotivated to another (and be regarded as a fusion). The more profound one’s command of the language and one’s knowledge of its history, the fewer fusions one is likely to discover in it.

The structural principle of classifying phraseological units is based on their ability to perform the same syntactical functions as words. In the traditional structural approach, the following principal groups of phraseological units are distinguishable.

A.Verbal. E. g. to run for one’s (dear) life, to get (win) the upper hand, to talk through one’s hat, to make a song and dance about something, to sit pretty (Amer. sl.).

B.Substantive. E. g. dog’s life, cat-and-dog life, calf love, white lie, tall order, birds of a feather, birds of passage, red tape, brown study.

C.Adjectival. E. g. high and mighty, spick and span, brand new, safe and sound. In this group the so-called comparative word-groups are particularly expressive and sometimes amusing in their unanticipated and capricious associations: (as) cool as a cucumber, (as) nervous as a cat, (as) weak as a kitten, (as) good as gold (usu. spoken about children), (as) pretty as a picture, as large as life, (as) slippery as an eel, (as) thick as thieves, (as) drunk as an owl (sl.), (as) mad as a hatter/a hare in March.

D. Adverbial. E. g. high and low (as in They searched for him high and low), by hook or by crook (as in She decided that, by hook or by crook, she must marry him), for love or money (as in He came to the conclusion that a really good job couldn’t be found for love or money), in cold blood (as in The crime was said to have been committed in cold blood), in the dead of night, between the devil and the deep sea (in a situation in which danger threatens whatever course of action one takes), to the bitter end (as in to fight to the bitter end), by a long chalk (as in It is not the same thing, by a long chalk).

E. Interjectional. E. g. my God/ by Jove! by George! goodness gracious! good Heavens! sakes alive! (Amer.)

d) Professor A.I. Smirnitsky’s classification of phraseological units

Professor Smirnitsky offered a classification system for English phraseological units which is interesting as an attempt to combine the structural and the semantic principles. Phraseological units in this classification system are grouped according to the number and semantic significance of their constituent parts. Accordingly two large groups are established:

A. One-summit units, which have one meaningful constituent (e. g. to give up, to make out, to pull out, to be tired, to be surprised1);

B. Two-summit and multi-summit units which have two or more meaningful constituents (e. g. black art, first night, common sense, to fish in troubled waters).

Within each of these large groups the phraseological units are classified according to the category of parts of speech of the summit constituent. So, one-summit units are subdivided into: a) verbal-adverbial units equivalent to verbs in which the semantic and the grammatical centres coincide in the first constituent (e. g. to give up); b) units equivalent to verbs which have their semantic centre in the second constituent and their grammatical centre in the first (e. g. to be tired); c) prepositional-substantive units equivalent either to adverbs or to copulas and having their semantic centre in the substantive constituent and no grammatical centre (e. g. by heart, by means of).

Two-summit and multi-summit phraseological units are classified into: a) attributive-substantive two-summit units equivalent to nouns (e. g. black art), b) verbal-substantive two-summit units equivalent to verbs (e. g. to take the floor), c) phraseological repetitions equivalent to adverbs (e. g. now or never); d) adverbial multi-summit units (e. g. every other day).

Professor A.I. Smirnitsky also distinguishes proper phraseological units which, in his classification system, are units with non-figurative meanings, and idioms, that is, units with transferred meanings based on a metaphor.

Professor A.V. Koonin, the leading Russian authority on English phraseology, pointed out certain inconsistencies in this classification system. First of all, the subdivision into phraseological units (as non-idiomatic units) and idioms contradicts the leading criterion of a phraseological unit suggested by Professor Smirnitsky: it should be idiomatic.

Professor Koonin also objects to the inclusion of such word-groups as black art, best man, first night in phraseology (in Professor Smirnitsky’s classification system, the two-summit phraseological units) as all these word-groups are not characterised by a transferred meaning. It is also pointed out that verbs with post-positions (e. g. give up) are included in the classification but their status as phraseological units is not supported by any convincing argument.

e) Professor A.V. Koonin’s classification of phraseological units

The classification system of phraseological units suggested by Professor A. V. Koonin is the latest out-standing achievement in the Russian theory of phraseology. The classification is based on the combined structural-semantic principle and it also considers the quotient of stability of phraseological units.

Phraseological units are subdivided into the following four classes according to their function in communication determined by their structural-semantic characteristics.

1) Nominative phraseological units are represented by word-groups, including the ones with one meaningful word, and coordinative phrases of the type wear and tear, well and good. The first class also includes word-groups with a predicative structure, such as as the crow flies, and, also, predicative phrases of the type see how the land lies, ships that pass in the night.

2) Nominative-communicative phraseological units include word-groups of the type to break the ice — the ice is broken, that is, verbal word-groups which are transformed into a sentence when the verb is used in the Passive Voice.

3) Phraseological units which are neither nominative nor communicative include interjectional word-groups.

4) Communicative phraseological units are represented by proverbs and sayings.

These four classes are divided into sub-groups according to the type of structure of the phraseological unit. The sub-groups include further rubrics representing types of structural-semantic meanings according to the kind of relations between the constituents and to either full or partial transference of meaning.

The classification system includes a considerable number of subtypes and gradations and objectively reflects the wealth of types of phraseological units existing in the language. It is based on truly scientific and modern criteria and represents an earnest attempt to take into account all the relevant aspects of phraseological units and combine them within the borders of one classification system.

f) Classification of phraseological units on the base of their origin

The consideration of the origin of phraseological units contributes to a better understanding of phraseological meaning. According to their origin all phraseological units may be divided into two big groups: native and borrowed.

a) The main sources of native phraseological units are:

1) Terminological and professional lexics, e.g. physics: center of gravity (центр тяжести), specific weight (удельный вес); navigation: cut the painter (обрубить канат) — ‘to become independent’, lower one’s colours (спустить свой флаг) — ‘to yield, to give in’; military sphere: fall into line (стать в строй) — ‘conform with others’;

2) British literature, e.g. the green-eyed monster —‘jealousy’ (W.Shakespeare); like Hamlet without the prince —‘the most important person at event is absent’ (W.Shakespeare); fall on evil days —‘live in poverty after having enjoyed better times’ (J.Milton); a sight for sore eyes — ‘a person or thing that one is extremely pleased or relieved to see’ (J.Swift); how goes the enemy? (Ch. Dickens) —‘what is the time?’; never say die —‘do not give up hope in a difficult situation’ (Ch.Dickens);

3) British traditions and customs, e.g. baker’s dozen —‘a group of thirteen’. In the past British merchants of bread received from bakers thirteen loaves instead of twelve and the thirteenth loaf was merchants’ profit.

4) Superstitions and legends, e.g. a black sheep —‘a less successful or more immoral person in a family or a group’. People believed that a black sheep was marked by the devil; the halcyon days —‘a very happy or successful period in the past’. According to an ancient legend a halcyon (зимородок) hatches/grows its fledglings in a nest that sails in the sea and during this period (about two weeks) the sea is completely calm;

5) Historical facts and events, personalities, e.g. as well be hanged (or hung) for a sheep as a lamb —‘something that you say when you are going to be punished for something so you decide to do something worse because your punishment will not be any more severe’. According to an old law a person who stole a sheep was sentenced to death by hanging, so it was worth stealing something more because there was no worse punishment; to do a Thatcher —‘to stay in power as prime minister for three consecutive terms (from the former Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher)’;

6) Phenomena and facts of everyday life, e.g. carry coals to Newcastle —‘to take something to a place where there is plenty of it available’. Newcastle is a town in Northern England where a lot of coal was produced; to get out of wood —‘to be saved from danger or difficulty’.

b) The main sources of borrowed phraseological units are:

1) the Holy Script, e.g. the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing —‘communication in an organization is bad so that one part does not know what is happening in another part’; the kiss of Judas — ‘any display of affection whose purpose is to conceal any act of treachery’ (Matthew XXVI: 49);

2) Ancient legends and myths belonging to different religious or cultural traditions, e.g. to cut the Gordian knot —‘to deal with a difficult problem in a strong, simple and effective way’ (from the legend saying that Gordius, king of Gordium, tied an intricate knot and prophesied that whoever untied it would become the ruler of Asia. It was cut through with a sword by Alexander the Great); a Procrustean bed —‘a harsh, inhumane system into which the individual is fitted by force, regardless of his own needs and wishes’ (from Greek Mythology, Procrustes — a robber who forced travelers to lie on a bed and made them fit by stretching their limbs or cutting off the appropriate length of leg);

3) Facts and events of the world history, e.g. to cross the Rubicon —‘to do something which will have very important results which cannot be changed after’. Julius Caesar started a war which resulted in victory for him by crossing the river Rubicon in Italy; to meet one’s Waterloo —‘be faced with, esp. after previous success, a final defeat, a difficulty or obstacle one cannot overcome (from the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo 1815)’;

4) Variants of the English language, e.g. a heavy hitter —‘someone who is powerful and has achieved a lot’ (American); a hole card —‘a secret advantage that is ready to use when you need it’ (American); be home and hosed —‘to have completed something successfully’ (Australian);

5) Other languages (classical and modern), e.g. second to none —‘equal with any other and better than most’ (from Latin: nulli secundus); for smb’s fair eyes —‘because of personal sympathy, not be worth one’s deserts, services, for nothing’ (from French: pour les beaux yeux de qn.); the fair sex — ‘women’ (from French: le beau sex); let the cat out of the bag — ‘reveal a secret carelessly or by mistake’ (from German: die Katze aus dem Sack lassen); tilt at windmills —‘to waste time trying to deal with enemies or problems that do no exist’ (from Spanish: acometer molinos de viento); every dog is a lion at home — ‘to feel significant in the familiar surrounding’ (from Italian: ogni cane e leone a casa sua).

FREE-WORD COMBINATIONS

Definition of a word-group and its basic features Structure of word-groups Meaning of word-groups Motivation in word-groups

Word-Group the largest two-facet language unit consists of more than one word studied in the syntagmatic level of analysis

Word-Group the degree of structural and semantic cohesion may vary e.g. at least, by means of, take place – semantically and structurally inseparable e.g. a week ago, kind to people – have greater semantic and structural independence

Free-Word Combination word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose

Features of Word-groups Lexical Valency Grammatical Valency

Lexical Valency (Collocability) The ability of a word to appear in various combinations with other words, or lexical contexts e.g. question – vital/pressing/urgent/etc., question at issue, to raise a question, a question on the agenda

Lexical Valency (Collocability) words habitually collocated in speech make a cliché e.g. to put forward a question

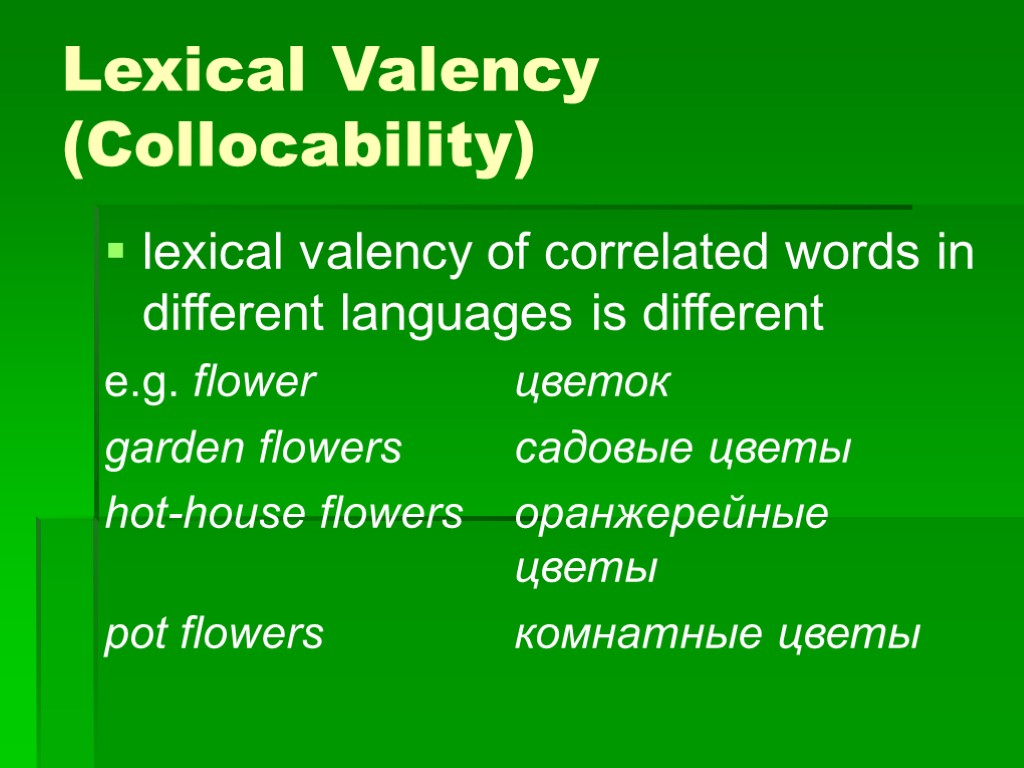

Lexical Valency (Collocability) lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different e.g. flower цветок garden flowers садовые цветы hot-house flowers оранжерейные цветы pot flowers комнатные цветы

Lexical Valency (Collocability) different meanings of one and the same word may be revealed through different type of lexical valency e.g. heavy table, book heavy snow, rain heavy drinker, eater heavy sorrow, sleep heavy industry

Grammatical Valency The ability of a word to appear in specific grammatical structures, or grammatical contexts

Grammatical Valency the minimal grammatical context in which the words are used when brought together to form a word-group is called the pattern of the word-group

Grammatical Valency restricted by the part of speech e.g. an adjective + noun, infinitive, prepositional group a kind man, kind to people, heavy to lift limited by the inner structure of the language e.g. to propose a plan – to suggest a plan to propose to do smth —

Grammatical Valency grammatical valency of correlated words in different languages is different e.g. enter the room — войти в комнату

Classifications of word-groups according to the distribution according to the head-word according to the syntactic pattern

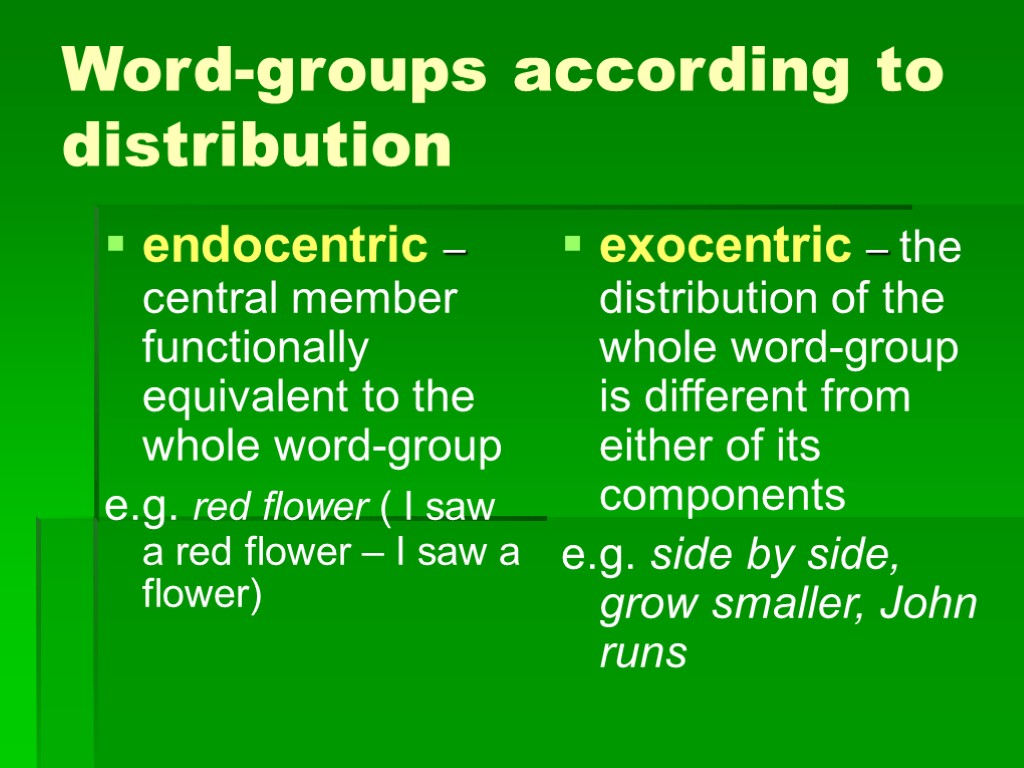

Word-groups according to distribution endocentric – central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group e.g. red flower ( I saw a red flower – I saw a flower) exocentric – the distribution of the whole word-group is different from either of its components e.g. side by side, grow smaller, John runs

Word-groups according to the head word nominal groups e.g. red flower adjectival groups e.g. kind to people verbal groups e.g. to speak well

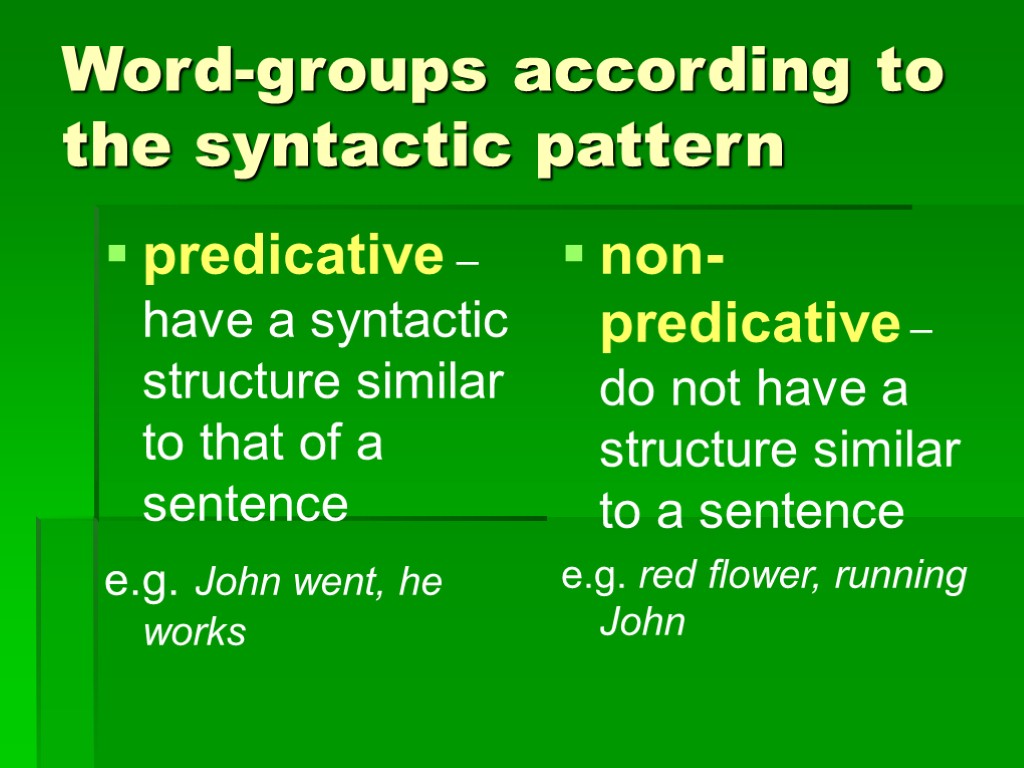

Word-groups according to the syntactic pattern predicative – have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence e.g. John went, he works non-predicative – do not have a structure similar to a sentence e.g. red flower, running John

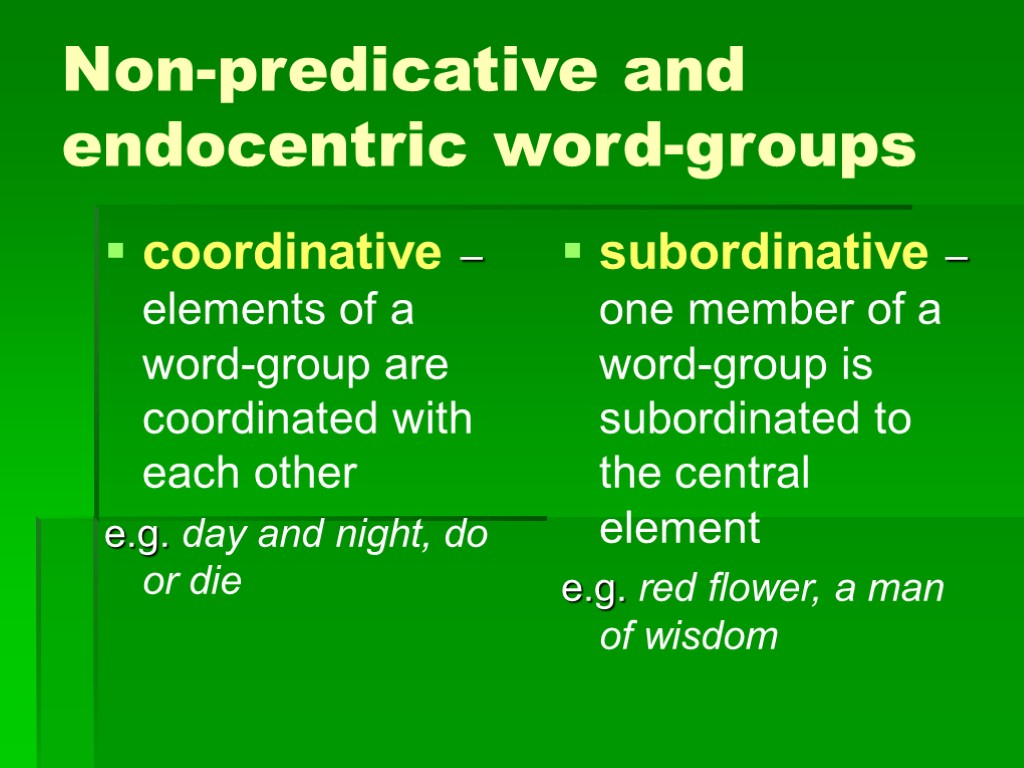

Non-predicative and endocentric word-groups coordinative – elements of a word-group are coordinated with each other e.g. day and night, do or die subordinative – one member of a word-group is subordinated to the central element e.g. red flower, a man of wisdom

Meaning of Word-Groups lexical meaning structural meaning

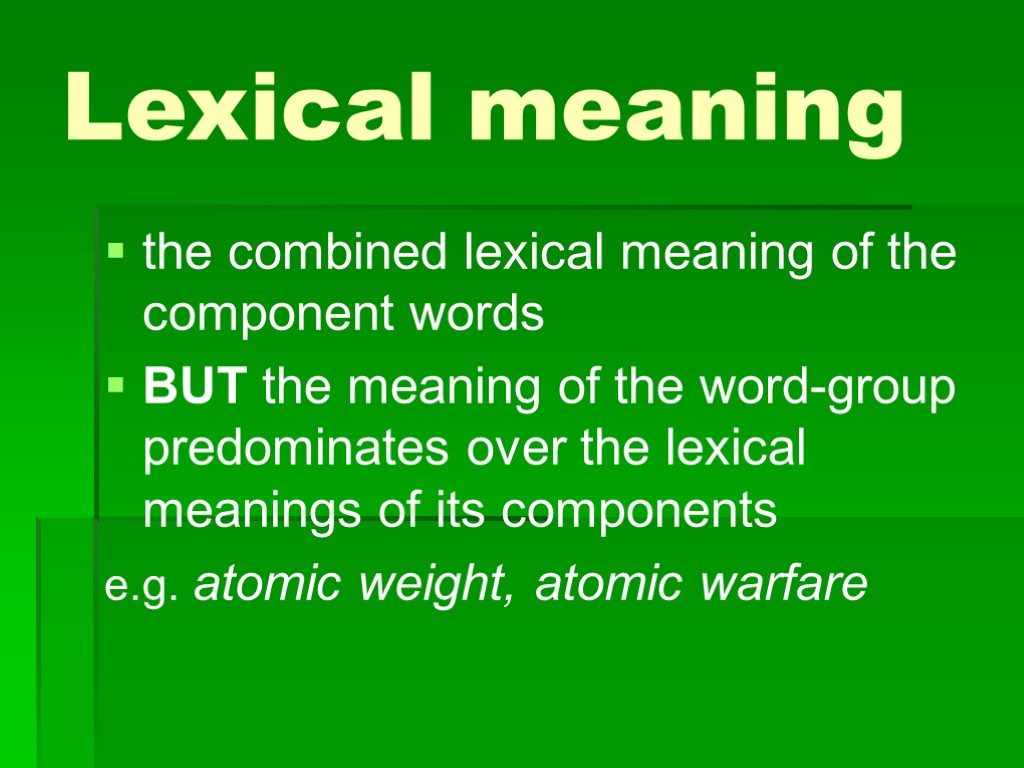

Lexical meaning the combined lexical meaning of the component words BUT the meaning of the word-group predominates over the lexical meanings of its components e.g. atomic weight, atomic warfare

Lexical meaning polysemantic words are used only in one of their meanings e.g. man and wife, blind man stylistic reference of a word-group may be different from that of its components e.g. old, boy, bags, fun – old boy (дружище), bags of fun

Structural meaning meaning conveyed by the arrangement of components of a word-group e.g. school grammar – grammar school

Structural meaning structural and lexical meanings are interdependent and inseparable e.g. school children – to school children all the sun long – all the night long, all the week long

Motivation in Word-groups lexically motivated — the combined lexical meaning of a group is deducible from the meanings of its components lexically non-motivated – the meaning of the whole is not seen through the meanings of the elements

Motivation in Word-groups lexically motivated e.g. red flower lexically non-motivated e.g. red tape – ‘official bureaucratic methods’

Motivation in Word-groups e.g. apple sauce – ‘a sauce made of apples’ apple sauce – ‘nonsense’

Motivation in Word-groups Non-motivated word-groups are called phraseological units or idioms

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

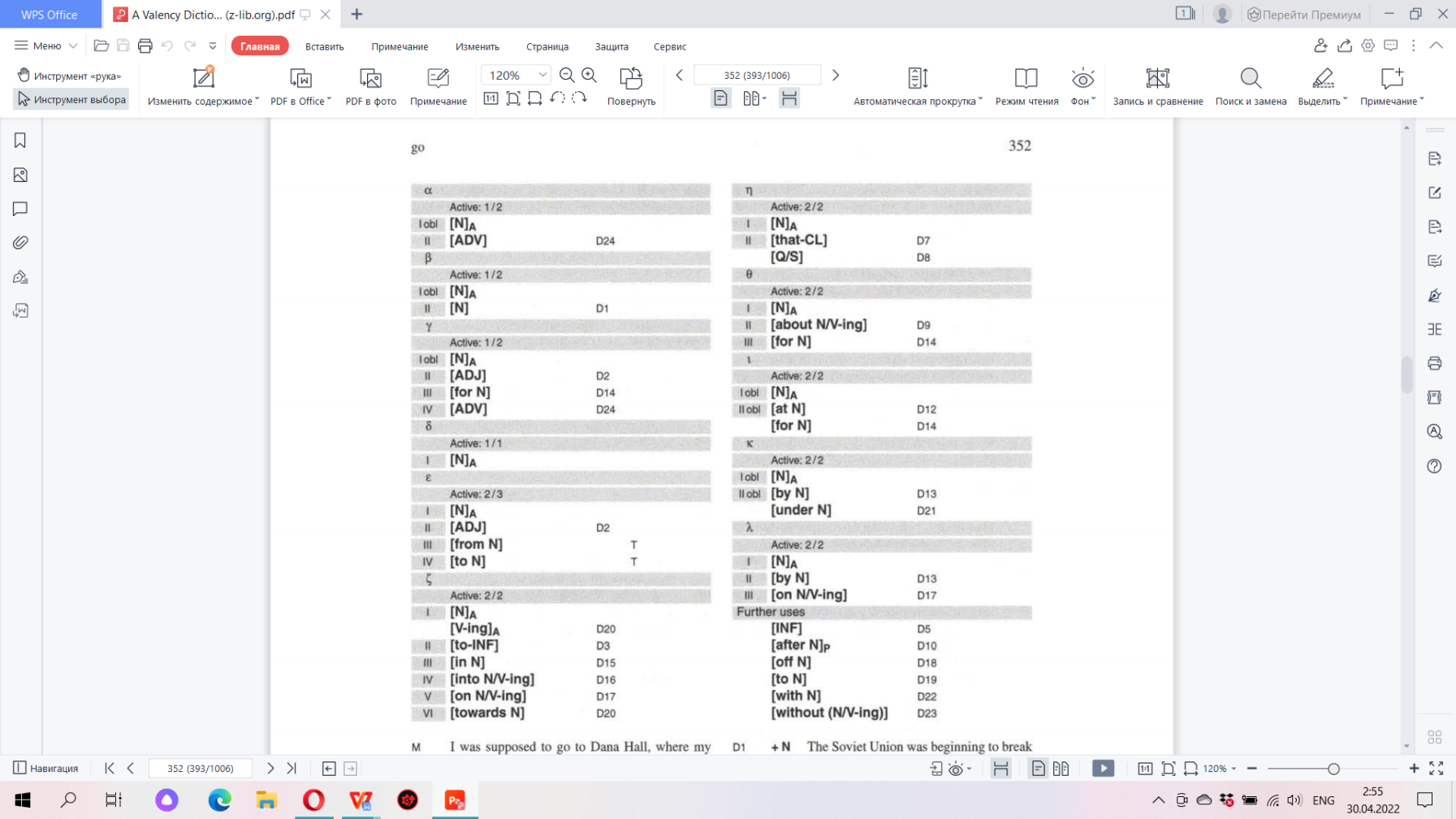

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |

| This year, my garden yielded several baskets full of tomatoes. | produce or provide |

| It is important for a teacher to develop a rapport with his or her students. | good relationship |