English[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

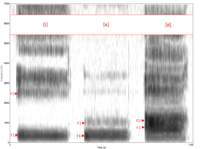

- enPR: lăngʹgwĭj, IPA(key): /ˈlæŋɡwɪd͡ʒ/

- (General American, Canada) IPA(key): (see /æ/ raising) [ˈleɪŋɡwɪd͡ʒ]

- Rhymes: -æŋɡwɪdʒ

- Hyphenation: lan‧guage

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English langage, language, from Old French language, from Vulgar Latin *linguāticum, from Latin lingua (“tongue, speech, language”), from Old Latin dingua (“tongue”), from Proto-Indo-European *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂s (“tongue, speech, language”). Displaced native Old English ġeþēode.

Noun[edit]

language (countable and uncountable, plural languages)

| Examples |

|---|

|

The English Wiktionary uses the English language to define words from all of the world’s languages.

|

- (countable) A body of words, and set of methods of combining them (called a grammar), understood by a community and used as a form of communication.

-

The English language and the German language are related.

-

Deaf and mute people communicate using languages like ASL.

- 1867, Report on the Systems of Deaf-Mute Instruction pursued in Europe, quoted in 1983 in History of the College for the Deaf, 1857-1907 →ISBN, page 240:

- Hence the natural language of the mute is, in schools of this class, suppressed as soon and as far as possible, and its existence as a language, capable of being made the reliable and precise vehicle for the widest range of thought, is ignored.

-

2000, Geary Hobson, The Last of the Ofos, →ISBN, page 113:

-

Mr. Darko, generally acknowledged to be the last surviving member of the Ofo Tribe, was also the last remaining speaker of the tribe’s language.

-

-

- (uncountable) The ability to communicate using words.

-

the gift of language

-

1981, William Irwin Thompson, The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light: Mythology, Sexuality and the Origins of Culture, London: Rider/Hutchinson & Co., page 15:

-

Language is the articulation of the limited to express the unlimited; it is the ultimate mystery which is the image of God, for in breaking up infinity to create finite beings, God has found a way to let the limited being yet be a reflection of His unlimited Being.

-

-

- (uncountable) A sublanguage: the slang of a particular community or jargon of a particular specialist field.

-

1892, Walter Besant, “Prologue: Who is Edmund Gray?”, in The Ivory Gate […], New York, N.Y.: Harper & Brothers, […], →OCLC:

-

Thus, when he drew up instructions in lawyer language, he expressed the important words by an initial, a medial, or a final consonant, and made scratches for all the words between; his clerks, however, understood him very well.

-

-

1991, Stephen Fry, The Liar, London: Heinemann, →OCLC, page 35:

-

And ‘blubbing’… Blubbing went out with ‘decent’ and ‘ripping’. Mind you, not a bad new language to start up. Nineteen-twenties schoolboy slang could be due for a revival.

-

-

legal language; the language of chemistry

-

- (countable, uncountable, figurative) The expression of thought (the communication of meaning) in a specified way; that which communicates something, as language does.

-

body language; the language of the eyes

-

2001, Eugene C. Kennedy; Sara C. Charles, On Becoming a Counselor, →ISBN:

-

A tale about themselves [is] told by people with help from the universal languages of their eyes, their hands, and even their shirting feet.

-

-

2005, Sean Dooley, The Big Twitch, Sydney: Allen and Unwin, page 231:

-

Birding had become like that for me. It is a language that, once learnt, I have been unable to unlearn.

-

-

- (countable, uncountable) A body of sounds, signs and/or signals by which animals communicate, and by which plants are sometimes also thought to communicate.

- 1983, The Listener, volume 110, page 14:

- A more likely hypothesis was that the attacked leaves were transmitting some airborne chemical signal to sound the alarm, rather like insects sending out warnings […] But this is the first time that a plant-to-plant language has been detected.

- 2009, Animals in Translation, page 274:

- Prairie dogs use their language to refer to real dangers in the real world, so it definitely has meaning.

- 1983, The Listener, volume 110, page 14:

- (computing, countable) A computer language; a machine language.

-

2015, Kent D. Lee, Foundations of Programming Languages, →ISBN, page 94:

-

In fact pointers are called references in these languages to distinguish them from pointers in languages like C and C++.

-

-

- (uncountable) Manner of expression.

- 1782, William Cowper, Hope

- Their language simple, as their manners meek, […]

- 1782, William Cowper, Hope

- (uncountable) The particular words used in a speech or a passage of text.

-

The language used in the law does not permit any other interpretation.

-

The language he used to talk to me was obscene.

-

- (uncountable) Profanity.

-

1978, James Carroll, Mortal Friends, →ISBN, page 500:

-

«Where the hell is Horace?» ¶ «There he is. He’s coming. You shouldn’t use language.»

-

-

Synonyms[edit]

- (form of communication): see Thesaurus:language

- (vocabulary of a particular field): see Thesaurus:jargon

- (computer language): computer language, programming language, machine language

- (particular words used): see Thesaurus:wording

Hypernyms[edit]

- medium

Hyponyms[edit]

- See Category:en:Languages

- artificial language

- auxiliary language

- bad language

- body language

- common language

- computer/computing language

- constructed language

- corpus language

- dead language

- endangered language

- engineered language

- everyday language

- experimental language

- extinct language

- foreign language

- formal language

- foul language

- global language

- hardware description language

- indigenous language

- international language

- link language

- literary language

- living language

- logical language

- machine language

- main language

- mathematical language

- meta language

- metaphorical language

- minority language

- modern language

- multi-paradigm language

- natural language

- object language

- pattern language

- philosophical language

- phonetic language

- planned language

- principal language

- private language

- programming language

- scripting language

- secular language

- sign language

- spoken language

- standard language

- subject-oriented language

- target language

- universal language

- vehicular language

- vernacular language

- working language

- world language

- active-stative language

- agglutinative language

- analytic language

- direct-inverse language

- E-language

- ergative-absolutive language

- I-language

- isolating language

- nominative-accusative language

- oligosynthetic language

- OV language

- polysynthetic language

- synthetic language

- tripartite language

- VO language

Derived terms[edit]

- A language

- AB language

- abstract language

- aspect-oriented language

- aspect-oriented programming language

- assembly language

- B language

- C language

- child language

- class-based language

- classical language

- clean language

- community language

- Community language

- conditional assembly language

- contact language

- context-free language

- curly-brace language

- curly-braces language

- curly-bracket language

- daughter language

- delegation language

- domain-specific language

- dynamic language

- e-language learning

- English-language

- esoteric programming language

- expressive language

- first language

- German-language

- ghost language

- good language

- heritage language

- high-level language

- home language

- imperative language

- indexing language

- interlanguage

- intermediate language

- international auxiliary language

- Iranian language

- Iranic language

- killer language

- language area

- language arts

- language assimilation

- language assistant

- language barrier

- language code

- language contact

- language continuum

- language cop

- language death

- language ecology

- language exchange

- language extinction

- language family

- language game

- language island

- language isolate

- language lab

- language laboratory

- language model

- language nest

- language of education

- language of flowers

- language planning

- language police

- language pollution

- language processing

- language replacement

- language school

- language shift

- language swap

- language technology

- language transfer

- language-agnostic

- language-independent

- languaging

- large language model

- link-language

- lip language

- liturgical language

- loaded language

- logical language

- love language

- low-level language

- macro language

- markup language

- matrix language

- mind one’s language

- mini-language

- mixed language

- moon language

- mother language

- native language

- natural language processing

- natural language understanding

- null-subject language

- object-based language

- object-oriented language

- official language

- Oïl language

- pandanus language

- parent language

- people-first language

- Polish-language

- private language argument

- private language problem

- private language thesis

- pro-drop language

- proto-language

- prototype-based language

- query language

- receptive language

- reconstructed language

- regular language

- role-oriented language

- Romance language

- second language

- sleeping language

- source language

- speak someone’s language

- speak the same language

- specific language impairment

- static language

- statically-typed language

- strong language

- style sheet language

- Sydney language

- symbolic language

- systems language

- Turkish-language

- unparliamentary language

- ur-language

- village sign language

- visual language

- visual programming language

- watch one’s language

- Western Desert language

- whole language

- wooden language

[edit]

- langue

- lingua

- lingua franca

- linguine

- linguistics

- tonguage

Translations[edit]

Verb[edit]

language (third-person singular simple present languages, present participle languaging, simple past and past participle languaged)

- (rare, now nonstandard or technical) To communicate by language; to express in language.

-

1655, Thomas Fuller, James Nichols, editor, The Church History of Britain, […], volume (please specify |volume=I to III), new edition, London: […] [James Nichols] for Thomas Tegg and Son, […], published 1837, →OCLC:

- Others were languaged in such doubtful expressions that they have a double sense.

-

Interjection[edit]

language

- An admonishment said in response to vulgar language.

-

You’re a pile of shit!

Hey! Language!

-

See also[edit]

- bilingual

- lexis

- linguistics

- multilingual

- term

- trilingual

- word

Etymology 2[edit]

Alteration of languet.

Noun[edit]

language (plural languages)

- A languet, a flat plate in or below the flue pipe of an organ.

-

1896, William Horatio Clarke, The Organist’s Retrospect, →ISBN Invalid ISBN, page 79:

-

A flue-pipe is one in which the air passes through the throat, or flue, which is the narrow, longitudinal aperture between the lower lip and the tongue, or language. […] The language is adjusted by slightly elevating or depressing it, […]

-

-

References[edit]

- language at OneLook Dictionary Search

- language in Keywords for Today: A 21st Century Vocabulary, edited by The Keywords Project, Colin MacCabe, Holly Yanacek, 2018.

- “language”, in The Century Dictionary […], New York, N.Y.: The Century Co., 1911, →OCLC.

French[edit]

Noun[edit]

language m (plural languages)

- Archaic spelling of langage.

Middle English[edit]

Noun[edit]

language (plural languages)

- Alternative form of langage

Middle French[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- langage, langaige, languaige

Etymology[edit]

From Old French language.

Noun[edit]

language m (plural languages)

- language (style of communicating)

[edit]

- langue

Descendants[edit]

- French: langage (see there for further descendants)

Old French[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Vulgar Latin *linguāticum, from Classical Latin lingua (“tongue, language”).

Pronunciation[edit]

- (archaic) IPA(key): /lenˈɡwad͡ʒə/

- (classical) IPA(key): /lanˈɡad͡ʒə/

- (late) IPA(key): /lanˈɡaʒə/

Noun[edit]

language f (oblique plural languages, nominative singular language, nominative plural languages)

- language (style of communicating)

[edit]

- langue, lingue

Descendants[edit]

- Bourguignon: langaige

- Middle French: language, langage, langaige, languaige

- French: langage (see there for further descendants)

Borrowings: (some possibly from O.Occitan lenguatge instead)

- → Middle English: langage, language, langag, langwache

- English: language

- → Friulian: lengaç

- → Ladin: lingaz

- → Romansch: linguatg, lungatg; lungaitg; linguach

noun

- a systematic means of communicating by the use of sounds or conventional symbols

he taught foreign languages

the language introduced is standard throughout the text

the speed with which a program can be executed depends on the language in which it is written

- (language) communication by word of mouth (syn: speech)

he uttered harsh language

he recorded the spoken language of the streets

- the text of a popular song or musical-comedy number (syn: lyric, words)

the song uses colloquial language

- the cognitive processes involved in producing and understanding linguistic communication

he didn’t have the language to express his feelings

- the mental faculty or power of vocal communication (syn: speech)

language sets homo sapiens apart from all other animals

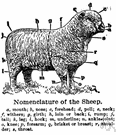

- a system of words used to name things in a particular discipline (syn: nomenclature, terminology)

the language of sociology

Extra examples

How many languages do you speak?

French is her first language.

The book has been translated into several languages.

He’s learning English as a second language.

A new word that has recently entered the language

The formal language of the report

The beauty of Shakespeare’s language

She expressed her ideas using simple and clear language.

He is always careful in his use of language.

His companion rounded on him with a torrent of abusive language.

It took him several years to master the language.

Andrea’s native language is German.

For the majority of Tanzanians, Swahili is their second language.

She had lived in Italy for years, and her command of the language was excellent.

I didn’t speak much Japanese, and I was worried that the language barrier might be a problem.

Word forms

noun

singular: language

plural: languages

lan·guage

(lăng′gwĭj)

n.

1.

a. Communication of thoughts and feelings through a system of arbitrary signals, such as voice sounds, gestures, or written symbols.

b. Such a system including its rules for combining its components, such as words.

c. Such a system as used by a nation, people, or other distinct community; often contrasted with dialect.

2.

a. A system of signs, symbols, gestures, or rules used in communicating: the language of algebra.

b. Computers A system of symbols and rules used for communication with or between computers.

3. Body language; kinesics.

4. The special vocabulary and usages of a scientific, professional, or other group: «his total mastery of screen language—camera placement, editing—and his handling of actors» (Jack Kroll).

5. A characteristic style of speech or writing: Shakespearean language.

6. A particular manner of expression: profane language; persuasive language.

7. The manner or means of communication between living creatures other than humans: the language of dolphins.

8. Verbal communication as a subject of study.

9. The wording of a legal document or statute as distinct from the spirit.

[Middle English, from Old French langage, from langue, tongue, language, from Latin lingua; see dn̥ghū- in Indo-European roots.]

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

language

(ˈlæŋɡwɪdʒ)

n

1. (Linguistics) a system for the expression of thoughts, feelings, etc, by the use of spoken sounds or conventional symbols

2. (Linguistics) the faculty for the use of such systems, which is a distinguishing characteristic of man as compared with other animals

3. (Linguistics) the language of a particular nation or people: the French language.

4. any other systematic or nonsystematic means of communicating, such as gesture or animal sounds: the language of love.

5. the specialized vocabulary used by a particular group: medical language.

6. a particular manner or style of verbal expression: your language is disgusting.

8. speak the same language to communicate with understanding because of common background, values, etc

[C13: from Old French langage, ultimately from Latin lingua tongue]

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

lan•guage

(ˈlæŋ gwɪdʒ)

n.

1. a body of words and the systems for their use common to a people of the same community or nation, the same geographical area, or the same cultural tradition: the French language.

2.

a. communication using a system of arbitrary vocal sounds, written symbols, signs, or gestures in conventional ways with conventional meanings: spoken language; sign language.

b. the ability to communicate in this way.

3. the system of linguistic signs or symbols considered in the abstract.

4. any set or system of formalized symbols, signs, sounds, or gestures used or conceived as a means of communicating: the language of mathematics.

5. the means of communication used by animals: the language of birds.

6. communication of thought, feeling, etc., through a nonverbal medium: body language; the language of flowers.

7. the study of language; linguistics.

8. the vocabulary or phraseology used by a particular group, profession, etc.

9. a particular manner of verbal expression: flowery language.

10. choice of words or style of writing; diction: the language of poetry.

11. a set of symbols and syntactic rules for their combination and use, by means of which a computer can be given directions.

12. Archaic. faculty or power of speech.

[1250–1300; Middle English < Anglo-French, variant of langage, Old French =langue tongue, language (< Latin lingua) + -age -age]

syn: language, dialect, jargon, vernacular refer to patterns of vocabulary, syntax, and usage characteristic of communities of various sizes and types. language is applied to the general pattern of a people or nation: the English language. dialect is applied to regionally or socially distinct forms or varieties of a language, often forms used by provincial communities that differ from the standard variety: the Scottish dialect. jargon is applied to the specialized language, esp. the vocabulary, used by a particular (usu. occupational) group within a community or to language considered unintelligible or obscure: technical jargon. The vernacular is the natural, everyday pattern of speech, usu. on an informal level, used by people indigenous to a community.

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

Language

language typical of academies or the world of learning; pedantic language.

a word, phrase, or idiom peculiar to American English. Cf. Briticism, Canadianism.

the art or practice of making anagrams. Also called metagrammatism.

anything characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race, especially any linguistic peculiarity that sterns from Old English and has not been affected by another language.

Linguistics. the loss of an initial unstressed vowel in a word, as squire for esquire. Also called apharesis, aphesis. — aphetic, adj.

of or relating to languages that have no grammatical inflections.

a word, phrase, idiom, or other characteristic of Aramaic occurring in a corpus written in another language.

Obsolete, a courtly phrase or expression. — aulic, adj.

the study of the Basque language and culture.

1. the ability to speak two languages.

2. the use of two languages, as in a community. Also bilinguality, diglottism. — bilingual, bilinguist, n. — bilingual, adj.

the state or quality of being composed of two letters, as a word. — biliteral, adj.

coarse, vulgar, violent, or abusive language. [Allusion to the scurrilous language used in Billingsgate market, London.]

a word, idiom, or phrase characteristic of or restricted to British English. Also called Britishism. Cf. Americanism, Canadianism.

1. a word or phrase commonly used in Canadian rather than British or American English. Cf. Americanism, Briticism.

2. a word or phrase typical of Canadian French or English that is present in another language.

3. an instance of speech, behavior, customs, etc., typical of Canada.

1. a word, phrase, or idiom characteristic of Celtic languages in material written in another language.

2. a Celtic custom or usage.

an idiom or other linguistic feature peculiar to Chaldean, especially in material written in another language. — Chaldaic, n., adj.

a word or phrase characteristic of Cilicia.

Rare. the use of euphemisms in order to avoid the use of plain words and any misfortune associated with them.

a word, phrase, or expression characteristic of ordinary or familiar conversation rather than formal speech or writing, as “She’s out” for “She is not at home.” — colloquial, adj.

a colloquial word or expression or one used in conversation more than in writing. Also conversationism.

a mania for foul speech.

1. the science or study of secret writing, especially code and cipher systems.

2. the procedures and methods of making and using secret languages, as codes or ciphers. — cryptographer, cryptographist, n. — cryptographic, cryptographical, cryptographal, adj.

1. the study of, or the use of, methods and procedures for translating and interpreting codes and ciphers; cryptanalysis.

2.cryptography. — cryptologist, n.

a word or expression characteristic of the Danish language.

1. of or relating to the common people; popular.

2. of, pertaining to, or noting the simplified form of hieratic writing used in ancient Egypt.

3. (cap.) of, belonging to, or connected with modern colloquial Greek. Also called Romaic.

a student of demotic language and writings.

an expression of scorn. — deristic, adj.

1. a dialect word or expression.

2. dialectal speech or influence.

a bilingual book or other work. — diglottic, adj.

the condition of having two syllables. — disyllable, n. — disyllabic, disyllabical, adj.

the use of language that is characteristic of the Dorian Greeks.

1. a deliberate substitution of a disagreeable, offensive, or disparaging word for an otherwise inoffensive term, as pig for policeman.

2. an instance of such substitution. Cf. euphemism.

a pithy statement, often containing a paradox.

paragoge.

the state or quality of being ambiguous in meaning or capable of double interpretation. — equivocal, adj.

a book of etymologies; any treatise on the derivation of words.

the branch of linguistics that studies the origin and history of words. — etymologist, n. — etymologie, etymological, adj.

1. the deliberate or polite use of a pleasant or neutral word or expression to avoid the emotional implications of a plain term, as passed over for died.

2. an instance of such use. Cf. dysphemism, genteelism. — euphemist, n. — euphemistic, euphemistical, euphemious, adj.

the customs, languages, and traditions distinctive of Europeans.

a custom or language characteristic peculiar to foreigners.

French characterized by an interlarding of English loan words.

a French loanword in English, as tête-à-tête. Also called Gallicism.

1. a French linguistic peculiarity.

2. a French idiom or expression used in another language. Also called Frenchism.

1. the deliberate use of a word or phrase as a substitute for one thought to be less proper, if not coarse, as male cow for buil or limb for leg.

2. an instance of such substitution.

a German loanword in English, as gemütlich. Also called Teutonism, Teutonicism.

the study of the origin of language. — glottogonic, adj.

1. the worship of letters or words.

2. a devotion to the letter, as in law or Scripture; literalism.

1. an expression or construction peculiar to Hebrew.

2. the character, spirit, principles, or customs of the Hebrew people.

3. a Hebrew loanword in English, as shekel. — Hebraist, n. — Hebraistic, Hebraic, adj.

the state or quality of a given word’s having the same spelling as another word, but with a different sound or pronunciation and a different meaning, as lead ’guide’ and lead ’metal.’ Cf. homonymy. — heteronym, n. — heteronymous, adj.

an unconscious tendency to use words other than those intended. Cf. malapropism.

1. an Irish characteristic.

2. an idiom peculiar to Irish English. Also called Hibernicism. — Hibernian, adj.

a Spanish word or expression that often appears in another language, as bodega.

the ability, in certain languages, to express a complex idea or entire sentence in a single word, as the imperative “Stop!” — holophrasm, n. — holophrastic, adj.

the state or quality of a given word’s having the same spelling and the same sound or pronunciation as another word, but with a different meaning, as race ’tribe’ and race ’running contest.’ Cf. heteronymy. — homonym, n. — homonymous, adj.

1. a word formed from elements drawn from different languages.

2. the practice of coining such words.

a compilation of idiomatic words and phrases.

the advocacy of using the artificial language Ido, based upon Esperanto. — Ido, Idoist, n. — Idoistic, adj.

the tendency in some individuals to refer to themselves in the third person. — illeist, n.

an artificial international language, based upon the Romance languages, designed for use by the scientific community.

excessive use of the sound i and the substituting of this sound for other vowels. — iotacist, n.

Rare. an Irishism.

1. a word or phrase commonly used in Ireland rather than England or America, as begorra.

2. a mode of speech, idiom, or custom characteristic of the Irish. Also Iricism.

the numerical equality between words or lines of verse according to the ancient Greek notation, in which each letter receives a corresponding number. — isopsephic, adj.

an Italian loanword in English, as chiaroscuro. Also Italicism.

1. an Italian loanword in English, as chiaroscuro.

2. Italianism. See also printing.

a style of art, idiom, custom, mannerism, etc., typical of the Japanese.

Rare. a person who makes use of a jargon in his speech.

a word or expression whose root is the Kentish dialect.

1. a mode of expression imitative of Latin.

2. a Latin word, phrase, or expression that of ten appears in another lan-guage. — Latinize, v.

1. a particular way of speaking or writing Latin.

2. the use or knowledge of Latin.

the writing or compiling of dictionaries. — lexicographer, n. — lexicographic, lexicographical, adj.

1. a person skilled in the science of language. Also linguistician.

2. a person skilled in many languages; a polyglot.

a custom or manner of speaking peculiar to one locality. Also called provincialism. — localist, n. — localistic, adj.

a system in which ruling power is vested in words.

Rare. a cunning with words; verbal legerdemain. Also logodaedalus.

veneration or excessive regard for words. — logolatrous, adj.

1. a dispute about or concerning words.

2. a contention marked by the careless or incorrect use of words; a mean-ingless battle of words. — logomach, logomacher, logomachist, n. — logo- machic, logomachical, adj.

a form of divination involving the observation of words and discourse.

a mania for words or talking.

a lover of words. Also called philologue, philologer.

an abnormal fear or dislike of words.

1. an excessive or abnormal, sometimes incoherent talkativeness. — logorrheic, adj.

1. the unconscious use of an inappropriate word, especially in a cliché, as fender for feather in “You could have knocked me over with a fender.” [Named after Mrs. Malaprop, a character prone to such uses, in The Rivals, by Richard Brinsley Sheridan]

2. an instance of such misuse. Cf. heterophemism.

a word or expression that comes from the language of the Medes.

a member of an order of Armenian monks, founded in 1715 by Mekhitar da Pietro, dedicated to literary work, espeeially the perfecting of the Armenian language and the translation into it of the major works of other languages.

anagrammatism.

the practice of making a literal translation from one language into another. Cf. paraphrasis. — metaphrast, n. — metaphrastic, metaphrastical, adj.

a person capable of speaking only one language.

the condition of having only one syllable. — monosyllable, n. — monosyllabic, adj.

Obsolete, speaking foolishly. — morologist, n.

mytacism.

excessive use of or fondness for, or incorrect use of the letter m and the sound it represents. Also mutacism.

1. a new word, usage, or phrase.

2. the coining or introduction of new words or new senses for established words. See also theology. — neologian, neologist, n. — neologistic, neologistical, adj.

Rare. neologism. — neophrastic, adj.

1. a neologism.

2. the use of neologisms. — neoterist, n.

a word or phrase characteristic of those who reside in New York City.

a word or expression characteristic of a northern dialect.

the science of defining technical terms. — orismologic, orismological, adj.

the art of correct grammar and correct use of words. — orthologer, orthologian, n. — orthological, adj.

the ability to speak any language. — pantoglot, n.

the addition of a sound or group of sounds at the end of a word, as in the nonstandard idear for idea. Also called epithesis. — paragogic, paragogical, adj.

the recasting of an idea in words different from that originally used, whether in the same language or in a translation. Cf. metaphrasis, periphrasis. — paraphrastic, paraphrastical, adj.

1. word formation by the addition of both a prefix and a suffix to a stem or word, as international.

2. word formation by the addition of a suffix to a phrase or compound word, as nickel-and-diming. — parasynthetic, adj.

the use of equivocal or ambiguous terms. — parisological, adj.

the collecting and study of proverbs. Cf. proverbialism. — paroe-miologist, n. — paroemiologic, paroemiological, adj.

1. an artificial international language using signs and figures instead of words.

2. any artificial language, as Esperanto. — pasigraphic, adj.

Linguistics. a semantic change in a word to a lower, less respect-able meaning, as in hussy. Also pejoration.

a book or other work written in five languages. — pentaglot, adj.

1. a roundabout way of speaking or writing; circumlocution.

2. an expression in such fashion. Cf. paraphrasis. — periphrastic, adj.

Archaic. a pleonasm.

1. an idiom or the idiomatic aspect of a language.

2. a mode of expression.

3. Obsolete, a phrasebook. — phraseologist, n. — phraseologic, phraseological, adj.

1. an addiction to spoken or written expression in platitudes.

2. a staleness or dullness of both language and ideas. Also called platitudinism. — platitudinarian, n.

1. the use of unnecessary words to express an idea; redundancy.

2. an instance of this, as true fact.

3. a redundant word or expression. — pleonastic, adj.

a specialist in Polish language, literature, and culture.

1. a person who speaks several languages.

2. a mixture of languages. See also books. — polyglot, n., adj. — polyglottic, polyglottous, adj.

the ability to use or to speak several languages. — polyglot, n., adj.

Rare. verbosity.

a diversity of meanings for a given word.

the condition of having three or more syllables. — polysyllable, n. — polysyllabic, polysyllabical, adj.

the creation or use of portmanteau words, or words that are a blend of two other words, as smog (from smoke and fog).

excessive fastidiousness or over-refinement in language or behavior.

purism.

excessive wordiness in speech or writing; longwindedness. — prolix, adj.

a phrase typical of the Biblical prophets.

the composing, collecting, or customary use of proverbs. Cf. paroemiology. — proverbialist, n.

localism.

a love of vacuous or trivial talk.

obfuscating language and jargon as used by psychologists, psychoanalysts, and psychiatrists, characterized by recondite phrases and arcane names for common conditions.

the policy or attempt to purify language and to make it conform to the rigors of pronunciation, usage, grammar, etc. that have been arbitrarily set forth by a certain group. Also called prescriptivism. See also art; criticism; literature; representation. — purist, n.,adj.

coarse, vulgar, or obscene language or joking. — ribald, adj.

demotic.

something characteristic of or influenced by Russia, its people, customs, language, etc.

a rustic habit or mode of expression. — rustic, adj. — rusticity, n.

a word, idiom, phrase, etc., of Anglo-Saxon or supposed Anglo-Saxon origin.

a feature characteristic of Scottish English or a word or phrase commonly used in Scotland rather than in England or America, as bonny.

1. the study of meaning.

2. the study of linguistic development by classifying and examining changes in meaning and form. — semanticist, semantician, n. — semantic, adj.

a word, phrase, or idiom from a Semitic language, especially in the context of another language.

the study of Semitic languages and culture. — Semitist, Semiticist, n.

the practice of using very long words. Also sesquipedalism, sesquipedality. — sesquipedal, sesquipedalian, adj.

a slangy expression or word.

a Slavic loanword in English, as blini.

one who specializes in the study of Slavic languages, literatures, or other aspects of Slavic culture. Also Slavist.

the transposition of initial or other sounds of words, usually by accident, as “queer dean” for “dear Queen.” [After the Rev. W. A. Spooner, 1844-1930, noted for such slips.] — spoonerize, v.

Archaic. the use of a secret language or code; cryptography. — steganographer, n.

the study of the language, history, and archaeology of the Sumerians. — Sumerologist, n.

a syllabary.

1. a table of syllables, as might be used for teaching a language.

2. a system of characters or symbols representing syllables instead of individual sounds. Also syllabarium.

a word that cannot be used as a term in its own right in logic, as an adverb or preposition. — syncategorematic, adj.

an expression whose origin is Syriac, a language based on the eastern Aramaic dialect.

Rare. tautology.

needless repetition of a concept in word or phrase; redundancy or pleonasm. Also tautologism. — tautologist, n. — tautological, tautologous, adj.

1. the classification of terms associated with a particular field; nomenclature.

2. the terms of any branch of knowledge, field of activity, etc. — terminologic, terminological, adj.

1. anything typical or characteristic of the Teutons or Germans, as customs, attitudes, actions, etc.

2. Germanism. — Teutonic, adj.

a word, phrase, or idiom in English that is common to both Great Britain and the United States.

a trite, commonplace or hackneyed saying, expression, etc.; a platitude.

1. the use of the second person, as in apostrophe.

2. in certain languages, the use of the familiar second person in cases where the formal third person is usually found and expected.

3. an instance of such use.

Rare. the state or quality of having only one meaning or of being unmistakable in meaning, as a word or statement. — univocal, adj.

1. a verbal expression, as a word or phrase.

2. the way in which something is worded.

3. a phrase or sentence devoid or almost devoid of meaning.

4. a use of words regarded as obscuring ideas or reality; verbiage.

wordiness or prolixity; an excess of words.

Facetious. misuse or overuse of a word or any use of a word which is damaging to it.

meaningless repetition of words and phrases.

an excessive use of or attraction to words.

the quality or condition of wordiness; excessive use of words, especially unnecessary prolixity. — verbose, adj.

1. a word, phrase, or idiom from the native and popular language, contrasted with literary or learned language.

2. the use of the vernacular. — vernacular, n., adj.

a word or phrase characteristic of a village or rural community.

a speaker or advocate of Volapük, a language proposed for use as an international language.

a word or phrase used chiefly in coarse, colloquial speech. — vulgarian, vulgarist, n.

the habit of referring to oneself by the pronoun “we.”

a word or form of pronunciation distinctive of the western United States.

a remark or expression characterized by cleverness in perception and choice of words.

Facetious. the art or technique of employing a vocabulary of arcane, recondite words in order to gain an advantage over another person.

1. a Yankee characteristic or character.

2. British. a linguistic or cultural trait peculiar to the United States.

3. Southern U.S. a linguistic or cultural trait peculiar to the states siding with the Union during the Civil War.

4. Northern U.S. a linguistic or cultural trait peculiar to the New England states.

a Yiddish loanword in English, as chutzpa.

the language and customs of people living in the county of Yorkshire, England.

-Ologies & -Isms. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Language

See Also: SPEAKING, WORD(S)

- Greek is like lace; every man gets as much as he can —Samuel Johnson

- It is with language as with manners: they are both established by the usage of people of fashion —Lord Chesterfield

See Also: MANNERS

- Language, if it throws a veil over our ideas, adds a softness and refinement to them, like that which the atmosphere gives to naked objects —William Hazlitt

- Language is a city, to the building of which every human being brings a stone —Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Language is an art, like brewing or baking —Charles R. Darwin

- Languages evolve like species. They can degenerate just as oysters and barnacles have lost their heads —F. L. Lucas

- Languages, like our bodies, are in a perpetual flux, and stand in need of recruits to supply those words which are continually falling into disuse —C. C. Felton

- Show them [Americans with a penchant for “fat” talk] a lean, plain word that cuts to the bones and watch them lard it with thick greasy syllables front and back until it wheezes and gasps for breath as it comes lumbering down upon some poor threadbare sentence like a sack of iron on a swayback horse —Russell Baker

- Slang is English with its sleeves rolled up —Carl Sandburg, quoted by William Safire in series on English language, PBS, September, 1986

- To write jargon is like perpetually shuffling around in the fog and cottonwool of abstract terms —Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

Similes Dictionary, 1st Edition. © 1988 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Language

(See also DICTION, GIBBERISH, PROFANITY.)

bombast Pretentious speech; high-flown or inflated language. It is but a short step from the now obsolete literal meaning of bombast ‘cotton-wool padding or stuffing for garments’ to its current figurative sense of verbal padding or turgid language. Shakespeare used the word figuratively as early as 1588:

We have received your letters full of love,

Your favors, the ambassadors of love,

And in our maiden council rated them

At courtship, pleasant jest and courtesy,

As bombast and as lining to the time.

(Love’s Labour’s Lost, V, ii)

bumf Official documents collectively; piles of paper, specifically, paper containing jargon and bureaucratise; thus, such language itself: gobbledegook, governmentese, Whitehallese, Washingtonese. This contemptuous British expression comes from bumf, a portmanteau type contraction for bum fodder ‘toilet paper.’ It has been used figuratively since the 1930s.

I shall get a daily pile of bumf from the Ministry of Mines. (Evelyn Waugh, Scoop, 1938)

claptrap Bombast, high-sounding but empty language. The word derives from the literal claptrap, defined in one of Nathan Bailey’s dictionaries (1727-31) as “a trap to catch a clap by way of applause from the spectators at a play.” The kind of high-flown and grandiose language actors would use in order to win applause from an audience gave the word its current meaning.

dirty word A word which because of its associations is highly controversial, a red-flag word; a word which elicits responses of suspicion, paranoia, dissension, etc.; a sensitive topic, a sore spot. Dirty word originally referred to a blatantly obscene or taboo word. Currently it is also used to describe a superficially inoffensive word which is treated as if it were offensive because of its unpleasant or controversial associations. Depending on the context, such a word can be considered unpopular and taboo one day and “safe” the next.

gobbledegook Circumlocutory and pretentious speech or writing; official or professional jargon, bureaucratese, officialese. The term’s coinage has been attributed to Maury Maverick.

The Veterans Administration translated its bureaucratic gobbledygook. (Time, July, 1947)

inkhorn term An obscure, pedantic word borrowed from another language, especially Latin or Greek; a learned or literary term; affectedly erudite language. An inkhorn is a small, portable container formerly used to hold writing ink and originally made of horn. It symbolizes pedantry and affected erudition in this expression as well as in the phrase to smell of the inkhorn ‘to be pedantic’ The expression, now archaic, dates from at least 1543.

Irrevocable, irradiation, depopulation and such like, … which …were long time despised for inkhorn terms. (George Puttenham, The Art of English Poesy, 1589)

jawbreaker A word difficult to pronounce; a polysyllabic word. This self-evident expression appeared in print as early as the 19th century.

You will find no “jawbreakers” in Sackville. (George E. Saintsbury, A History of Elizabethan Literature, 1887)

malapropism The ridiculous misuse of similar sounding words, sometimes through ignorance, but often with punning or humorous intent. This eponymous term alludes to Mrs. Malaprop, a pleasant though pompously ignorant character in Richard B. Sheridan’s comedie play, The Rivals (1775). Mrs. Malaprop, whose name is derived from the French mal à propos ‘inappropriate,’ continually confuses and misapplies words and phrases, e.g., “As headstrong as an allegory [alligator] on the banks of the Nile.” (III, iii)

Lamaitre has reproached Shakespeare for his love of malapropisms. (Harper’s Magazine, April, 1890)

A person known for using malapropisms is often called a Mrs. Malaprop.

mumbo jumbo See GIBBERISH.

portmanteau word A word formed by the blending of two other words. Portmanteau is a British term for a suitcase which opens up into two parts. The concept of a portmanteau word was coined by Lewis Carroll in Through the Looking Glass (1872):

Well, ‘slithy’ means “lithe and slimy”

… You see it’s like a portmanteau—

There are two meanings packed into one.

Carroll’s use of portmanteau has been extended to include the amalgamation of one or more qualities into a single idea or notion This usage is illustrated by D. G. Hoffman, as cited in Webster’s Third:

Its central character is a portmanteau figure whose traits are derived from several mythical heroes.

red-flag term A word whose associations trigger an automatic response of anger, belligerence, defensiveness, etc.; an inflammatory catchphrase. A red flag has long been the symbol of revolutionary insurgents. To wave the red flag is to incite to violence. In addition, it is conventionally believed that a bull becomes enraged and aroused to attack by the waving of a red cape. All these uses are interrelated and serve as possible antecedents of red-flag used adjectivally to describe incendiary language.

Picturesque Expressions: A Thematic Dictionary, 1st Edition. © 1980 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

ThesaurusAntonymsRelated WordsSynonymsLegend:

| Noun | 1. |  language — a systematic means of communicating by the use of sounds or conventional symbols; «he taught foreign languages»; «the language introduced is standard throughout the text»; «the speed with which a program can be executed depends on the language in which it is written» language — a systematic means of communicating by the use of sounds or conventional symbols; «he taught foreign languages»; «the language introduced is standard throughout the text»; «the speed with which a program can be executed depends on the language in which it is written»

linguistic communication communication — something that is communicated by or to or between people or groups usage — the customary manner in which a language (or a form of a language) is spoken or written; «English usage»; «a usage borrowed from French» dead language — a language that is no longer learned as a native language words — language that is spoken or written; «he has a gift for words»; «she put her thoughts into words» source language — a language that is to be translated into another language target language, object language — the language into which a text written in another language is to be translated accent mark, accent — a diacritical mark used to indicate stress or placed above a vowel to indicate a special pronunciation sign language, signing — language expressed by visible hand gestures artificial language — a language that is deliberately created for a specific purpose metalanguage — a language that can be used to describe languages native language — the language that a person has spoken from earliest childhood indigenous language — a language that originated in a specified place and was not brought to that place from elsewhere superstrate, superstratum — the language of a later invading people that is imposed on an indigenous population and contributes features to their language natural language, tongue — a human written or spoken language used by a community; opposed to e.g. a computer language interlanguage, lingua franca, koine — a common language used by speakers of different languages; «Koine is a dialect of ancient Greek that was the lingua franca of the empire of Alexander the Great and was widely spoken throughout the eastern Mediterranean area in Roman times» linguistic string, string of words, word string — a linear sequence of words as spoken or written expressive style, style — a way of expressing something (in language or art or music etc.) that is characteristic of a particular person or group of people or period; «all the reporters were expected to adopt the style of the newspaper» barrage, bombardment, onslaught, outpouring — the rapid and continuous delivery of linguistic communication (spoken or written); «a barrage of questions»; «a bombardment of mail complaining about his mistake» speech communication, spoken communication, spoken language, voice communication, oral communication, speech, language — (language) communication by word of mouth; «his speech was garbled»; «he uttered harsh language»; «he recorded the spoken language of the streets» slanguage — language characterized by excessive use of slang or cant alphabetize — provide with an alphabet; «Cyril and Method alphabetized the Slavic languages» synchronic — concerned with phenomena (especially language) at a particular period without considering historical antecedents; «synchronic linguistics» diachronic, historical — used of the study of a phenomenon (especially language) as it changes through time; «diachronic linguistics» |

| 2. |  language — (language) communication by word of mouth; «his speech was garbled»; «he uttered harsh language»; «he recorded the spoken language of the streets» language — (language) communication by word of mouth; «his speech was garbled»; «he uttered harsh language»; «he recorded the spoken language of the streets»

speech communication, spoken communication, spoken language, voice communication, oral communication, speech language, linguistic communication — a systematic means of communicating by the use of sounds or conventional symbols; «he taught foreign languages»; «the language introduced is standard throughout the text»; «the speed with which a program can be executed depends on the language in which it is written» auditory communication — communication that relies on hearing words — the words that are spoken; «I listened to his words very closely» orthoepy, pronunciation — the way a word or a language is customarily spoken; «the pronunciation of Chinese is difficult for foreigners»; «that is the correct pronunciation» conversation — the use of speech for informal exchange of views or ideas or information etc. give-and-take, discussion, word — an exchange of views on some topic; «we had a good discussion»; «we had a word or two about it» locution, saying, expression — a word or phrase that particular people use in particular situations; «pardon the expression» non-standard speech — speech that differs from the usual accepted, easily recognizable speech of native adult members of a speech community idiolect — the language or speech of one individual at a particular period in life monologue — a long utterance by one person (especially one that prevents others from participating in the conversation) magic spell, magical spell, charm, spell — a verbal formula believed to have magical force; «he whispered a spell as he moved his hands»; «inscribed around its base is a charm in Balinese» dictation — speech intended for reproduction in writing monologue, soliloquy — speech you make to yourself |

|

| 3. | language — the text of a popular song or musical-comedy number; «his compositions always started with the lyrics»; «he wrote both words and music»; «the song uses colloquial language»

lyric, words text, textual matter — the words of something written; «there were more than a thousand words of text»; «they handed out the printed text of the mayor’s speech»; «he wants to reconstruct the original text» song, vocal — a short musical composition with words; «a successful musical must have at least three good songs» love lyric — the lyric of a love song |

|

| 4. | language — the cognitive processes involved in producing and understanding linguistic communication; «he didn’t have the language to express his feelings»

linguistic process higher cognitive process — cognitive processes that presuppose the availability of knowledge and put it to use reading — the cognitive process of understanding a written linguistic message; «his main reading was detective stories»; «suggestions for further reading» |

|

| 5. | language — the mental faculty or power of vocal communication; «language sets homo sapiens apart from all other animals»

speech faculty, mental faculty, module — one of the inherent cognitive or perceptual powers of the mind lexis — all of the words in a language; all word forms having meaning or grammatical function lexicon, mental lexicon, vocabulary — a language user’s knowledge of words verbalise, verbalize — convert into a verb; «many English nouns have become verbalized» |

|

| 6. |  language — a system of words used to name things in a particular discipline; «legal terminology»; «biological nomenclature»; «the language of sociology» language — a system of words used to name things in a particular discipline; «legal terminology»; «biological nomenclature»; «the language of sociology»

nomenclature, terminology word — a unit of language that native speakers can identify; «words are the blocks from which sentences are made»; «he hardly said ten words all morning» markup language — a set of symbols and rules for their use when doing a markup of a document toponomy, toponymy — the nomenclature of regional anatomy |

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

language

noun

3. speech, communication, expression, speaking, talk, talking, conversation, discourse, interchange, utterance, parlance, vocalization, verbalization Students examined how children acquire language.

4. style, wording, expression, phrasing, vocabulary, usage, parlance, diction, phraseology a booklet summarising it in plain language

Quotations

«Language is the dress of thought» [Samuel Johnson Lives of the English Poets: Cowley]

«After all, when you come right down to it, how many people speak the same language even when they speak the same language?» [Russell Hoban The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz]

«Languages are the pedigrees of nations» [Samuel Johnson]

«A language is a dialect with an army and a navy» [Max Weinrich]

«One does not inhabit a country; one inhabits a language. That is our country, our fatherland — and no other» [E.M. Cioran Anathemas and Admirations]

«Everything can change, but not the language that we carry inside us, like a world more exclusive and final than one’s mother’s womb» [Italo Calvino By Way of an Autobiography]

«To God I speak Spanish, to women Italian, to men French, and to my horse — German» [attributed to Emperor Charles V]

«In language, the ignorant have prescribed laws to the learned» [Richard Duppa Maxims]

«Language is fossil poetry» [Ralph Waldo Emerson Essays: Nominalist and Realist]

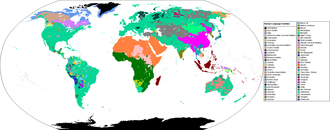

Languages

African Languages Adamawa, Afrikaans, Akan, Amharic, Bambara, Barotse, Bashkir, Bemba, Berber, Chewa, Chichewa, Coptic, Damara, Duala, Dyula, Edo, Bini, or Beni, Ewe, Fanagalo or Fanakalo, Fang, Fanti, Fula, Fulah, or Fulani, Ga or Gã, Galla, Ganda, Griqua or Grikwa, Hausa, Herero, Hottentot, Hutu, Ibibio or Efik, Ibo or Igbo, Kabyle, Kikuyu, Kingwana, Kirundi, Kongo, Krio, Lozi, Luba or Tshiluba, Luganda, Luo, Malagasy, Malinke or Maninke, Masai, Matabele, Mossi or Moore, Nama or Namaqua, Ndebele, Nuba, Nupe, Nyanja, Nyoro, Ovambo, Pedi or Northern Sotho, Pondo, Rwanda, Sango, Sesotho, Shona, Somali, Songhai, Sotho, Susu, Swahili, Swazi, Temne, Tigré, Tigrinya, Tiv, Tonga, Tsonga, Tswana, Tuareg, Twi or (formerly) Ashanti, Venda, Wolof, Xhosa, Yoruba, Zulu

Asian Languages Abkhaz, Abkhazi, or Abkhazian, Adygei or Adyghe, Afghan, Ainu, Arabic, Aramaic, Armenian, Assamese, Azerbaijani, Bahasa Indonesia, Balinese, Baluchi or Balochi, Bengali, Bihari, Brahui, Burmese, Buryat or Buriat, Cantonese, Chukchee or Chukchi, Chuvash, Chinese, Cham, Circassian, Dinka, Divehi, Dzongka, Evenki, Farsi, Filipino, Gondi, Gujarati or Gujerati, Gurkhali, Hebrew, Hindi, Hindustani, Hindoostani, or Hindostani, Iranian, Japanese, Javanese, Kabardian, Kafiri, Kalmuck or Kalmyk, Kannada, Kanarese, or Canarese, Kara-Kalpak, Karen, Kashmiri, Kazakh or Kazak, Kazan Tatar, Khalkha, Khmer, Kirghiz, Korean, Kurdish, Lahnda, Lao, Lepcha, Malay, Malayalam or Malayalaam, Manchu, Mandarin, Marathi or Mahratti, Mishmi, Mon, Mongol, Mongolian, Moro, Naga, Nepali, Nuri, Oriya, Ossetian or Ossetic, Ostyak, Pashto, Pushto, or Pushtu, Punjabi, Shan, Sindhi, Sinhalese, Sogdian, Tadzhiki or Tadzhik, Tagalog, Tamil, Tatar, Telugu or Telegu, Thai, Tibetan, Tungus, Turkmen, Turkoman or Turkman, Uigur or Uighur, Urdu, Uzbek, Vietnamese, Yakut

Australasian Languages Aranda, Beach-la-Mar, Dinka, Fijian, Gurindji, Hawaiian, Hiri Motu, kamilaroi, Krio, Maori, Moriori, Motu, Nauruan, Neo-Melanesian, Papuan, Pintubi, Police Motu, Samoan, Solomon Islands Pidgin, Tongan, Tuvaluan, Warlpiri

European Languages Albanian, Alemannic, Basque, Bohemian, Bokmål, Breton, Bulgarian, Byelorussian, Castilian, Catalan, Cheremiss or Cheremis, Cornish, Croatian, Cymric or Kymric, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Erse, Estonian, Faeroese, Finnish, Flemish, French, Frisian, Friulian, Gaelic, Gagauzi, Galician, Georgian, German, Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Karelian, Komi, Ladin, Ladino, Lallans or Lallan, Lapp, Latvian or Lettish, Lithuanian, Lusatian, Macedonian, Magyar, Maltese, Manx, Mingrelian or Mingrel, Mordvin, Norwegian, Nynorsk or Landsmål, Polish, Portuguese, Provençal, Romanian, Romansch or Romansh, Romany or Romanes, Russian, Samoyed, Sardinian, Serbo-Croat or Serbo-Croatian, Shelta, Slovak, Slovene, Sorbian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, Udmurt, Ukrainian, Vogul, Votyak, Welsh, Yiddish, Zyrian

North American Languages Abnaki, Aleut or Aleutian, Algonquin or Algonkin, Apache, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Blackfoot, Caddoan, Catawba, Cayuga, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Chickasaw, Chinook, Choctaw, Comanche, Creek, Crow, Delaware, Erie, Eskimo, Fox, Haida, Hopi, Huron, Inuktitut, Iroquois, Kwakiutl, Mahican or Mohican, Massachuset or Massachusetts, Menomini, Micmac, Mixtec, Mohave or Mojave, Mohawk, Narraganset or Narragansett, Navaho or Navajo, Nez Percé, Nootka, Ojibwa, Okanagan, Okanogan, or Okinagan, Oneida, Onondaga, Osage, Paiute or Piute, Pawnee, Pequot, Sahaptin, Sahaptan, or Sahaptian, Seminole, Seneca, Shawnee, Shoshone or Shoshoni, Sioux, Tahltan, Taino, Tlingit, Tuscarora, Ute, Winnebago, Zuñi

South American Languages Araucanian, Aymara, Chibchan, Galibi, Guarani, Nahuatl, Quechua, Kechua, or Quichua, Tupi, Zapotec

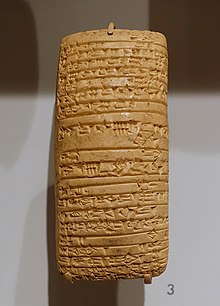

Ancient Languages Akkadian, Ancient Greek, Anglo-Saxon, Assyrian, Avar, Avestan or Avestic, Aztec, Babylonian, Canaanite, Celtiberian, Chaldee, Edomite, Egyptian, Elamite, Ethiopic, Etruscan, Faliscan, Frankish, Gallo-Romance or Gallo-Roman, Ge’ez, Gothic, Hebrew, Himyaritic, Hittite, Illyrian, Inca, Ionic, Koine, Langobardic, langue d’oc, langue d’oïl, Latin, Libyan, Lycian, Lydian, Maya or Mayan, Messapian or Messapïc, Norn, Old Church Slavonic, Old High German, Old Norse, Old Prussian, Oscan, Osco-Umbrian, Pahlavi or Pehlevi, Pali, Phoenician, Phrygian, Pictish, Punic, Sabaean or Sabean, Sabellian, Sanskrit, Scythian, Sumerian, Syriac, Thracian, Thraco-Phrygian, Tocharian or Tokharian, Ugaritic, Umbrian, Vedic, Venetic, Volscian, Wendish

Artificial Languages Esperanto, Ido, interlingua, Volapuk or Volapük

Language Groups Afro-Asiatic, Albanian, Algonquian or Algonkian, Altaic, Anatolian, Athapascan, Athapaskan, Athabascan, or Athabaskan, Arawakan, Armenian, Australian, Austro-Asiatic, Austronesian, Baltic, Bantu, Benue-Congo, Brythonic, Caddoan, Canaanitic, Carib, Caucasian, Celtic, Chadic, Chari-Nile, Cushitic, Cymric, Dardic, Dravidian, East Germanic, East Iranian, Eskimo, Finnic, Germanic, Gur, Hamitic, Hamito-Semitic, Hellenic, Hindustani, Indic, Indo-Aryan, Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Indo-Pacific, Iranian, Iroquoian, Italic, Khoisan, Kordofanian, Kwa, Malayo-Polynesian, Mande, Mayan, Melanesian, Micronesian, Mongolic, Mon-Khmer, Munda, Muskogean or Muskhogean, Na-Dene or Na-Déné, Nguni, Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan, Nilotic, Norse, North Germanic, Oceanic, Pahari, Pama-Nyungan, Penutian, Polynesian, Rhaetian, Romance, Saharan, Salish or Salishan, San, Sanskritic, Semi-Bantu, Semitic, Semito-Hamitic, Shoshonean, Siouan, Sinitic, Sino-Tibetan, Slavonic, Sudanic, Tibeto-Burman, Trans-New Guinea phylum, Tungusic, Tupi-Guarani, Turkic, Ugric, Uralic, Uto-Aztecan, Voltaic, Wakashan, West Atlantic, West Germanic, West Iranian, West Slavonic, Yuman

Collins Thesaurus of the English Language – Complete and Unabridged 2nd Edition. 2002 © HarperCollins Publishers 1995, 2002

language

noun

1. A system of terms used by a people sharing a history and culture:

2. Specialized expressions indigenous to a particular field, subject, trade, or subculture:

argot, cant, dialect, idiom, jargon, lexicon, lingo, patois, terminology, vernacular, vocabulary.

The American Heritage® Roget’s Thesaurus. Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

1

a

: the words, their pronunciation, and the methods of combining them used and understood by a community

studied the French language

b(1)

: audible, articulate, meaningful sound as produced by the action of the vocal organs

(2)

: a systematic means of communicating ideas or feelings by the use of conventionalized signs, sounds, gestures, or marks having understood meanings

the language of mathematics

(3)

: the suggestion by objects, actions, or conditions of associated ideas or feelings

language in their very gesture—

(4)

: the means by which animals communicate

(5)

: a formal system of signs and symbols (such as FORTRAN or a calculus in logic) including rules for the formation and transformation of admissible expressions

2

a

: form or manner of verbal expression

specifically

: style

the beauty of Shakespeare’s language

b

: the vocabulary and phraseology belonging to an art or a department of knowledge

the language of diplomacy

c

: profanity

shouldn’t of blamed the fellers if they’d cut loose with some language—

3

: the study of language especially as a school subject

earned a grade of B in language

4

: specific words especially in a law or regulation

The police were diligent in enforcing the language of the law.

Synonyms

Example Sentences

How many languages do you speak?

French is her first language.

The book has been translated into several languages.

He’s learning English as a second language.

a new word that has recently entered the language

the formal language of the report

the beauty of Shakespeare’s language

She expressed her ideas using simple and clear language.

He is always careful in his use of language.

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

The majority of classes provide subtitles in several languages, however.

—

There’s a handful of Latin, or Spanish-language, artists who will be performing at the 2023 edition, which is slated to run on two consecutive weekends, from April 14 to 16 and then again from April 21 to 23.

—

Every Tuesday and Thursday, Cpt. Andrew Winters ends the long workday with a three-hour Korean-language class.

—

Since 1952, Planeta has bestowed an annual reward to outstanding unpublished Spanish-language works with the largest endowment worldwide, one million Euros.

—

On the Chinese-language front, aside from Zhang’s blockbuster, the selection includes the recent Chinese remake of Hachiko, featuring another Chinese industry legend, Feng Xiaogang, in the lead role.

—

The game has since sold millions of copies in more than 40 languages worldwide.

—

Versions of Me featured tracks with artists like Saweetie, Khalid, and Missy Elliott, showing Anitta moving seamlessly into English-language collaborations.

—

Poway Unified has promoted its varied schooling options, which include a hybrid school that combines online and in-person learning, a virtual-only school, a home-schooling program and dual-language programs, Osborne said.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘language.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Middle English, from Anglo-French langage, from lange, langue tongue, language, from Latin lingua — more at tongue

First Known Use

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

Time Traveler

The first known use of language was

in the 14th century

Dictionary Entries Near language

Cite this Entry

“Language.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/language. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on language

Last Updated:

10 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

The word as a basic unit of language

The word is the subject matter of Lexicology. The

word may be described as a basic unit of language. The definition of

the word is one of the most difficult problems in Linguistics because

any word has many different aspects. It is simultaneously a semantic,

grammatical and phonological unit.

Accordingly the word may be defined as

the basic unit of a given language resulting from the association of

a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds capable of a

particular grammatical employment. This

definition based on the definition of a word given by the eminent

French linguist Arthur Meillet does

not permit us to distinguish words from phrases. We

can accept the given definition adding that a word is the smallest

significant unit of a given language capable of functioning alone and

characterized by positional mobility within a sentence, morphological

uninterruptability and semantic integrity.

In Russian Linguistics it is the word but not the morpheme as in

American descriptive linguistics that is the basic unit of language

and the basic unit of lexical articulation of the flow of the speech.

Thus, the word is a structural and

semantic entity within the language system. The word is the basic

unit of the language system, the largest on the morphological level

and the smallest on the syntactic level of linguistic analysis.

As any language unit the word is a two facet unit possessing both its

outer form (sound form) and content (meaning) which is not created in

speech but used ready-maid. As the basic unit of language the word is

characterized by independence or separateness (отдельность),

as a free standing item, and identity (тождество).

The word as an independent

free standing language unit is

distinguished in speech due to its ability to take on grammatical

inflections (грамматическая

оформленнасть) which makes it

different from the morpheme.

The structural

integrity (цельная

оформленнасть) of the word

combined with the semantic integrity and morphological

uninterruptability (морфологическая

непрерывность) makes the word

different from word combinations.

The identity of the

word manifests itself in the ability of

a word to exist as a system and unity of all its forms (grammatical

forms creating its paradigm) and variants: lexical-semantic,

morphological, phonetic and graphic.

The system showing a word in all its word forms is

called its paradigm. The lexical meaning of a word is the same

throughout the paradigm, i.e. all the word forms of one and the same

word are lexical identical while the grammatical meaning varies from

one form to another (give-gave-given-giving-gives;

worker-workers-worker’s-workers’).

Besides the grammatical forms of the words (or

word forms), words possess lexical varieties called variants of words

(a word – a polisemantic word in one of its meanings in which it is

used in speech is described as a lexical-semantic variants. The term

was introduced by A.I. Smernitskiy; e.g. “to learn at school” –

“to learn about smth”; man – мужчина/человек).

Words may have phonetic, graphic and morphological variants:

often – [Þfən]/[

Þftən] – phonetic

variants

birdy/birdie –

graphic variants

phonetic/phonetical – morphological

variants

Thus, within the language system the word exists as a system and

unity of all its forms and variants. The term lexeme may

serve to express the idea of the word as a system of its forms and

variants.

Every word names a given referent and another one and this

relationship creates the basis for establishing understanding in

verbal intercourse (общение). But because

words mirror concepts through our perception of the world there’s

no singleness in word-thing correlations.

As reality becomes more complicated, it calls for

more sophisticated means of nomination. In recent times Lexicology

has developed a more psycho-linguistic and ethno-cultural orientation

aimed at looking into the actual reality of how lexical items work.

Соседние файлы в папке Lecture1

- #

- #

- #

- #

- Top Definitions

- Synonyms

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Scientific

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

[ lang-gwij ]

/ ˈlæŋ gwɪdʒ /

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

a body of words and the systems for their use common to a people who are of the same community or nation, the same geographical area, or the same cultural tradition: the two languages of Belgium; a Bantu language; the French language; the Yiddish language.

communication by voice in the distinctively human manner, using arbitrary sounds in conventional ways with conventional meanings; speech.

the system of linguistic signs or symbols considered in the abstract (opposed to speech).

any set or system of such symbols as used in a more or less uniform fashion by a number of people, who are thus enabled to communicate intelligibly with one another.

any system of formalized symbols, signs, sounds, gestures, or the like used or conceived as a means of communicating thought, emotion, etc.: the language of mathematics; sign language.

the means of communication used by animals: the language of birds.

communication of meaning in any way; medium that is expressive, significant, etc.: the language of flowers; the language of art.

linguistics; the study of language.

the speech or phraseology peculiar to a class, profession, etc.; lexis; jargon.

a particular manner of verbal expression: flowery language.

choice of words or style of writing; diction: the language of poetry.

Computers. a set of characters and symbols and syntactic rules for their combination and use, by means of which a computer can be given directions: The language of many commercial application programs is COBOL.

a nation or people considered in terms of their speech.

Archaic. faculty or power of speech.

VIDEO FOR LANGUAGE

Calling All Wordies: Why Do You Love Language And Words?

We’re asking you, Dictionary.com wordies (a person with an enthusiastic interest in words and language; a logophile), to tell us why you love language and words. Go!

MORE VIDEOS FROM DICTIONARY.COM

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of language

First recorded in 1250–1300; Middle English, from Anglo-French, variant spelling of langage, derivative of langue “tongue.” See lingua, -age

synonym study for language

2. See speech. 4, 9. Language, dialect, jargon, vernacular refer to linguistic configurations of vocabulary, syntax, phonology, and usage that are characteristic of communities of various sizes and types. Language is a broad term applied to the overall linguistic configurations that allow a particular people to communicate: the English language; the French language. Dialect is applied to certain forms or varieties of a language, often those that provincial communities or special groups retain (or develop) even after a standard has been established: Scottish dialect; regional dialect; Southern dialect. A jargon is either an artificial linguistic configuration used by a particular (usually occupational) group within a community or a special configuration created for communication in a particular business or trade or for communication between members of groups that speak different languages: computer jargon; the Chinook jargon. A vernacular is the authentic natural pattern—the ordinary speech—of a given language, now usually on the informal level. It is at once congruent with and, in relatively small ways, distinguished from the standard language in syntax, vocabulary, usage, and pronunciation. It is used by persons indigenous to a certain community, large or small.

OTHER WORDS FROM language

pre·lan·guage, adjective

Words nearby language

Langshan, Langston, langsyne, Langton, Langtry, language, language acquisition device, language arts, language barrier, language death, language laboratory

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to language

accent, dialect, expression, jargon, prose, sound, speech, style, terminology, vocabulary, voice, word, argot, articulation, brogue, cant, communication, conversation, diction, dictionary

How to use language in a sentence

-

It offers a more searing version of events than the sometimes technical language in previous crash reports and investigations, including one conducted by the Transportation Department’s Inspector General.

-

The language that was used — that could have possibly had a chilling effect on other people coming forward — shouldn’t have been allowed.

-

Toucan raises $3 million to teach you new languages as you browse the web — The startup has developed a Chrome browser extension designed for anyone who wants to learn a new language but hasn’t found the motivation or the time.

-

Looking ahead, Toucan is planning to add new languages and to launch browser extensions for Firefox and Safari.

-

This announcement covers changes to Google Search, Google News, autocomplete, fact checking, through BERT and language processing.

-

Despite the strong language, however, the neither the JPO nor Lockheed could dispute a single fact in either Daily Beast report.

-

Some of them already are in Germany taking language lessons.

-

His first language was Russian, then he learned Swedish, but chooses to perform in monosyllabic broken English.

-

We also have a language filled with distaste for the civilian “others.”

-

Disagreements will focus on right and wrong, not parsing of legal language.

-

“Perhaps you do not speak my language,” she said in Urdu, the tongue most frequently heard in Upper India.

-

I would ask you to imagine it translated into every language, a common material of understanding throughout all the world.

-

And all over the world each language would be taught with the same accent and quantities and idioms—a very desirable thing indeed.

-

But don’t go hunting after them, there are still modern Immortals in the darkness of a forgotten language.

-

Light, the symbol of life’s joy, seems to be the first language in which the spirit of beauty speaks to a child.

British Dictionary definitions for language

noun

a system for the expression of thoughts, feelings, etc, by the use of spoken sounds or conventional symbols

the faculty for the use of such systems, which is a distinguishing characteristic of man as compared with other animals

the language of a particular nation or peoplethe French language