This article is written for users of the following Microsoft Word versions: 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, and Word in Microsoft 365. If you are using an earlier version (Word 2003 or earlier), this tip may not work for you. For a version of this tip written specifically for earlier versions of Word, click here: Inserting Foreign Characters.

Written by Allen Wyatt (last updated December 21, 2019)

This tip applies to Word 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, and Word in Microsoft 365

If English is your native language, you may periodically have a need to type something that contains a character that doesn’t appear in the English alphabet. For instance, words that are of French descent (such as résumé) may require an accent over some of the vowels to be technically correct.

The first thing to remember is that you are not creating some kind of «compound character» that is composed of a regular character and an accent mark. What you are doing is using a single character from a foreign language—the é character is a single character, not a compound character.

There are multiple ways to insert foreign characters. One way is to choose Symbol from the Insert menu, and then look for the character you need. While this approach is possible, it can quickly become tedious if you use quite a few special characters in your writing.

Another possible approach is to use the AutoCorrect feature of Word. This works great for some words, and not so great for others. For instance, you wouldn’t want to set up AutoCorrect to convert all instances of resume to résumé, since both variations are words in their own right. You can use it for other words that do not have a similar spelling in English. In fact, Microsoft has already included several such words in AutoCorrect—for instance, if you type souffle you get soufflé or if you type touche you get touché.

Word does include a set of handy shortcuts for creating foreign characters. Essentially, the shortcut consists of holding down the Ctrl key and pressing the accent mark that appears as part of the foreign character, and then pressing the character that appears under the accent mark. For instance, to create the é in résumé, you would type Ctrl+’ (an apostrophe) and then type the e. There are a number of these shortcuts, as shown here:

| Shortcut | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| Ctrl+’ | Adds an acute accent to the character typed next (é) | |

| Ctrl+’ | When followed by d or D, creates the old English character «eth» (ð, Ð) | |

| Ctrl+` | Adds a grave accent to the character typed next (á) | |

| Ctrl+^ | Adds a circumflex to the character typed next (â) | |

| Ctrl+~ | Adds a tilde to the character typed next (ñ) | |

| Ctrl+: | Adds a dieresis or umlaut to the character typed next (ü) | |

| Ctrl+@ | Adds a degree symbol above the letters a and A; used primarily in Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish (å, Å) | |

| Ctrl+& | Creates combination or Germanic characters based on the character typed next (æ) | |

| Ctrl+, | Adds a cedilla to the character typed next (ç) | |

| Ctrl+/ | Adds a slash through the letters o and O; used primarily in Danish and Norwegian (ø, Ø) | |

| Alt+Ctrl+? | Creates an upside-down question mark (¿) | |

| Alt+Ctrl+! | Creates an upside-down exclamation mark (¡) |

Note that not all shortcuts hold to the general rule outlined earlier, and some accent character designators are approximations. (For instance, using Ctrl+: results in the next character having an umlaut, as in ü, even though the colon is not the actual accent character used.)

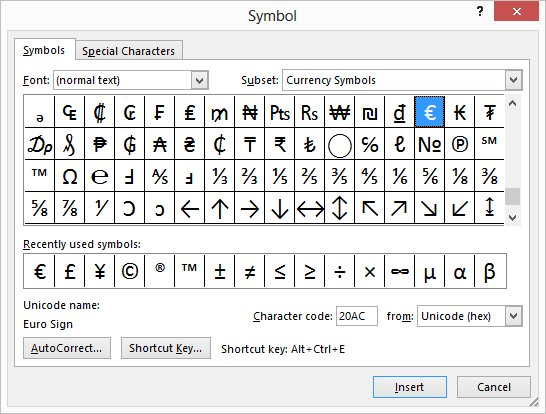

If you ever forget the shortcut combination for a particular foreign character, you can use the Symbol dialog box to help you out. For instance, let’s assume that you forget how to create ñ, as in Cañon City, a lovely town in Colorado that is home to the amazing Royal Gorge Bridge. You could follow these general steps:

- Type the first two characters of the city name (Ca).

- Display the Symbol dialog box.

- Make sure that the Font drop-down is set to (normal text). (See Figure 1.)

- In the character area of the dialog box, locate the ñ character and select it.

- Notice at the bottom right portion of the dialog box you can see the keyboard shortcut you can use to create the character. In this case, you use Ctrl+~ followed by the n.

Figure 1. The Symbol dialog box.

You can use this technique to figure out the shortcut for any of the foreign-language characters.

Another method for inserting foreign characters is to just remember their ANSI codes, and then enter them by holding down the Alt key as you type the code on the numeric keypad. For instance, you can enter the é in résumé by holding down Alt and entering 0233 on the keypad. When the Alt key is released, the specified character appears. Interestingly enough, you can find out what the ANSI values are by using the Character Map accessory in Windows. While it functions very similarly to the Symbol dialog box in Word, the shortcuts shown all rely on the Alt-keypad technique.

WordTips is your source for cost-effective Microsoft Word training.

(Microsoft Word is the most popular word processing software in the world.)

This tip (10445) applies to Microsoft Word 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, and Word in Microsoft 365. You can find a version of this tip for the older menu interface of Word here: Inserting Foreign Characters.

Author Bio

With more than 50 non-fiction books and numerous magazine articles to his credit, Allen Wyatt is an internationally recognized author. He is president of Sharon Parq Associates, a computer and publishing services company. Learn more about Allen…

MORE FROM ALLEN

Protecting Fields

Fields are very helpful for inserting dynamic information or standardizing the information that appears in a document. …

Discover More

Understanding Auditing

Excel provides some great tools that can help you see the relationships between the formulas in your worksheets. These …

Discover More

Finding the Path to the Desktop

Figuring out where Windows places certain items (such as the user’s desktop) can be a bit frustrating. Fortunately, there …

Discover More

Word for Microsoft 365 Outlook for Microsoft 365 Word 2021 Outlook 2021 Word 2019 Outlook 2019 Word 2016 Outlook 2016 Word 2013 Outlook 2013 Word 2010 More…Less

In Word and Outlook, you can use accent marks (or diacritical marks) in a document, such as an acute accent, cedilla, circumflex, diaeresis or umlaut, grave accent, or tilde.

-

For keyboard shortcuts in which you press two or more keys simultaneously, the keys to press are separated by a plus sign (+) in the tables. For example, to type a copyright symbol © , hold down the Alt key and type 0169.

-

For keyboard shortcuts in which you press one key immediately followed by another key, the keys to press are separated by a comma (,). For example, for è you would press Ctrl + ` , release and then type e.

-

To type a lowercase character by using a key combination that includes the SHIFT key, hold down the CTRL+SHIFT+symbol keys simultaneously, and then release them before you type the letter. For example, to type a ô, hold down CTRL, SHIFT and ^, release and type o.

|

To insert this |

Press |

|---|---|

|

à, è, ì, ò, ù, |

CTRL+` (ACCENT GRAVE), the letter |

|

á, é, í, ó, ú, ý |

CTRL+’ (APOSTROPHE), the letter |

|

â, ê, î, ô, û |

CTRL+SHIFT+^ (CARET), the letter |

|

ã, ñ, õ |

CTRL+SHIFT+~ (TILDE), the letter |

|

ä, ë, ï, ö, ü, ÿ, |

CTRL+SHIFT+: (COLON), the letter |

|

å, Å |

CTRL+SHIFT+@, a or A |

|

æ, Æ |

CTRL+SHIFT+&, a or A |

|

œ, Œ |

CTRL+SHIFT+&, o or O |

|

ç, Ç |

CTRL+, (COMMA), c or C |

|

ð, Ð |

CTRL+’ (APOSTROPHE), d or D |

|

ø, Ø |

CTRL+/, o or O |

|

¿ |

ALT+CTRL+SHIFT+? |

|

¡ |

ALT+CTRL+SHIFT+! |

|

ß |

CTRL+SHIFT+&, s |

|

The Unicode character for the specified Unicode (hexadecimal) character code |

The character code, ALT+X For example, to insert the euro currency symbol |

|

The ANSI character for the specified ANSI (decimal) character code |

ALT+the character code (on the numeric keypad) Make sure that NUM LOCK is on before you type the character code. For example, to insert the euro currency symbol, hold down the ALT key and press 0128 on the numeric keypad. For more info on using Unicode and ASCII characters, see Insert ASCII or Unicode character codes. |

|

To insert this macron character: Ā ā Ē ē Ī ī Ō ō Ū ū |

Press this: Alt+0256 Alt+0257 Alt+0274 Alt+0275 Alt+0298 Alt+0299 Alt+0332 Alt+0333 Alt+0362 Alt+0363 |

Notes:

-

If you’re working on a laptop without a separate numeric keyboard, you can add most accented characters using the Insert > Symbol > More Symbols command in Word. For more info, see Insert a symbol in Word.

-

If you plan to type in other languages often you should consider switching your keyboard layout to that language. For more info see Switch between languages using the Language bar.

Need more help?

Want more options?

Explore subscription benefits, browse training courses, learn how to secure your device, and more.

Communities help you ask and answer questions, give feedback, and hear from experts with rich knowledge.

This question is not about italicisation or how to construct plurals. I wonder what are general guidelines for writing foreign words based on a Latin alphabet in English text. I know that, for languages written in completely different script systems, there exist more or less standard per-language “romanization” procedures (such as writing Japanse in rōmaji). My question is about words from languages with Latin script, where some glyphs are not found commonly in English. Examples of such characters include:

- accents of all kinds (é, ô, ñ, etc.)

- ligatures (æ, œ, ij, Å, ç, ķ, etc.)

- characters not found at all: thorn (Þ), eth (ð), german ß,

How should these words be written in English text? Should they be copied entirely, normalized in some way (e.g., ß → ss, é → e), or transliterated so that they can be read as they should be spelt?

My personal preference is to borrow them as they are, but I would like to know what style guides recommand and what is common usage in press.

Added: data from some research is inconsistent:

- New Oxford American Dictionary has piñata, but Anschluss (vs. ß) and oeuvre (vs. œ).

- The Guardian uses the two variants of both Anschluß and œuvre

- I don’t know other languages well enough that I know what to look for

2nd addition: I’m starting a bounty on this, because I style haven’t found any reference to actual style guides, or research from data in open-access corpuses/corpora (which I don’t know how to do myself).

tchrist♦

132k48 gold badges366 silver badges566 bronze badges

asked Jan 19, 2011 at 12:31

10

The Times (not to be confused with the New York Times) style guide says:

foreign words Write in roman when foreign words and phrases have become essentially a part of the English language (eg, elite, debacle, fête, de rigueur, soirée); likewise, now use roman rather than italic, but retain accents, in a bon mot, a bête noire, the raison d’être. Avoid pretension by using an English phrase wherever one will serve. See accents

and

accents Give French, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Italian, Irish and Ancient Greek words their proper accents and diacritical marks; omit in other languages unless you are sure of them. Accents should be used in headlines and on capital letters. With Anglicised words, no need for accents in foreign words that have taken English nationality (hotel, depot, debacle, elite, regime etc), but keep the accent when it makes a crucial difference to pronunciation or understanding — café, communiqué, détente, émigré, façade, fête, fiancée, mêlée, métier, pâté, protégé, raison d’être; also note vis-à-vis. See foreign words, Spanish

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/tools_and_services/specials/style_guide/article986724.ece

Thursagen

41.4k43 gold badges165 silver badges241 bronze badges

answered Jan 22, 2011 at 23:10

Peter TaylorPeter Taylor

3,89125 silver badges24 bronze badges

1

The ideal would be to preserve the word as it appears in its native language, but it is something that English-speakers are very lazy about. Anything that looks orthographically odd (i.e. has glyphs that aren’t part of everyday English) stands out and is usually thought of as pretentious, so there is a strong social pressure to normalize. Ligatures in particular tend to unlink into their component letters (think of ß as a ligature in this respect), and missing characters translate in various slightly inconsistent ways.

If a word becomes common currency in English, it gets normalized over time. In particular, the accents fall off: writing «café» is considered a bit affected these days, and «rôle» has pretty much died out, for example.

answered Jan 19, 2011 at 14:19

2

I am no expert in this matter, but as a native speaker of other languages beside English, I would like to contribute the following.

I have the impression that the OP is using the label «accents of all kinds» for things that fall in, at least, two very different categories: some are true accents, such as the one in «á», and some others are not, like the one on «ñ». The «á» in Spanish is still an «a» to all effects, but an accented one. However, an «ñ» is not an accented «n» but a totally different letter altogether. They are not exchangeable.

answered Jan 21, 2011 at 23:57

CesarGonCesarGon

3,5751 gold badge23 silver badges31 bronze badges

8

The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), says that ligatures should be decomposed in Latin and transliterated Greek, as well as in words borrowed into the English lexicon. However, æ and œ should be used for Old English and French words respectively, when respectively in an Old English or French context.

There’s a whole chapter on foreign languages, but in general I’d preserve accents and “strange” letters when including words from foreign languages.

But it depends a lot on context as well. What kind of text are you writing, who is your audience? In an academic context the answer is usually pretty straightforward (just see how books and papers in relevant fields do it), but if you’re writing for a wider audience, simplifying may be prudent.

tchrist♦

132k48 gold badges366 silver badges566 bronze badges

answered Jan 24, 2011 at 9:57

arnsholtarnsholt

4333 silver badges8 bronze badges

The accents that are more likely to be kept in are the ones we’re more familiar with. British kids are taught French so French words are almost never changed. Latin-based alphabets that the country is not familiar with, such as Scandinavian languages are more likely to be changed, either to french style or none.

answered Jan 20, 2011 at 23:09

tobylanetobylane

2511 silver badge3 bronze badges

Generally they should be written as they appear in their native language; this is the standard practice in the press, I believe.

answered Jan 19, 2011 at 12:38

7

I’ve often seen phrases or words in foreign languages italicized in text to signal to the reader that the word is of foreign origin, and may therefore be later explained to the reader at the author’s discretion. The author can include as many foreign characters as they feel is appropriate.

Be very careful about this, however. For example, if the reader has no familiarity with the language in question and the author decides not to explain the text in question, the reader may start to feel excluded or left out of the story.

One extreme example would be the teachers in Charlie Brown cartoons (not text, I know). Usually, the Charlie Brown characters will partially restate the trombone «wah-wo-whas» in their reply, so as to keep the intended audience included in the implied other half of the conversation.

answered Jan 19, 2011 at 16:21

ZootZoot

3,4451 gold badge20 silver badges32 bronze badges

The decision to transliterate or not depends on the original language. Russian, Sanskrit, and Ancient Greek are Indo-European languages that are usually transliterated. However, commentaries on original texts often do not transliterate. Some writers use both original and transliterated texts (Jacob Klein’s A Commentary On Plato’s Meno).

answered Jan 21, 2011 at 17:43

JonJon

4951 gold badge3 silver badges8 bronze badges

2

-

#1

Some questions on transliteration. Letter ج «JEEM» is pronounced as G in Egyptian Arabic and is used to write English, England — Ingiliizi, Ingiltera (saw too many romanisations for the same word!). Is ج pronounced as J in other Arabic countries in the same word? I also saw it written with «kaf» ك Is there a standard way to show G sound in Arabic (not just Egyptian)?

Letter ڤ (veh = feh with 3 dots above) is used to convey V

Letter پ (peh = beh with 3 dots below) is used to convey P

Letter چ (tcheh = jiim with 3 dots below) is used to convey ch or j (in Egyptian Arabic only?)

Is «e» (as in pen) usually replaced with «a» (tanis = tennis) or «i» (tilifizyuun)?

Is «o» usually replaced with «u» in foreign words?

SC Unipad software has some Arabic symbols for which I haven’t seen any description, to mention some:

ٯ

ٺ

ٻ

ټ

ٽ

ٿ

ڀ

ڃ

ڄ

څ

ڇ

Are some of these used in other languages using Arabic script or are they special symbols for some othe purposes?

elroy

Moderator: EHL, Arabic, Hebrew, German(-Spanish)

-

#2

Anatoli said:

Some questions on transliteration. Letter ج «JEEM» is pronounced as G in Egyptian Arabic and is used to write English, England — Ingiliizi, Ingiltera (saw too many romanisations for the same word!). Is ج pronounced as J in other Arabic countries in the same word?

No — at least not in Palestinian Arabic. We say «Ingliizi» and «Ingeltra.»

I also saw it written with «kaf» ك Is there a standard way to show G sound in Arabic (not just Egyptian)?

Generally, a ج is used but as you have observed a ك is also possible.

Letter ڤ (veh = feh with 3 dots above) is used to convey V

Letter پ (peh = beh with 3 dots below) is used to convey PLetter چ (tcheh = jiim with 3 dots below) is used to convey ch or j (in Egyptian Arabic only?)

To me it is used to convey «g.» For «ch» I would simply write تش and for «j» I’d use ج of course.

Is «e» (as in pen) usually replaced with «a» (tanis = tennis) or «i» (tilifizyuun)?

«i,» undoubtedly

Is «o» usually replaced with «u» in foreign words?

yes

SC Unipad software has some Arabic symbols for which I haven’t seen any description, to mention some:

ٯ

ٺ

ٻ

ټ

ٽ

ٿ

ڀ

ڃ

ڄ

څ

ڇAre some of these used in other languages using Arabic script or are they special symbols for some othe purposes?

Besides the first three you mentioned (before the list), we do not use any non-Arabic symbols. Anything else would have to be part of other languages that use the Arabic script.

-

#3

Anatoli,

Elroi’s comments are invaluable. Remember there are differences in colloquial that do not exist in MSA. I will add that ج is g in Northern Egypt not Southern Egypt. I have heard gineh the unit of currency pronounced jineh in the south. It is also g in the Adeni variant of Yemeni Arabic. For foreign/loan words; on a menu the French word gateau was written with ج and a man requested jatoh. Peugeot spelled with ب, And ف for v. Back to colloquial in the Gulf including Iraq چ ch local pronunciation of ك . I do not think it is common but in Tunisia, I have seen ڤ for g the southern and Bedouin pronunciation of ق in song lyrics. The Gulf and Iraq use گ for the g sound of ق. As for the other letters you wrote they are called modified Arabic letters ( note their origin is Arabic but they represent sounds not found in classical Arabic) See Urdu, Farsi, Uigur/Uyghur alphabets on Wikipedia or other sources.By the way Parsi is the original name for Farsi before the Arabic alphabet was used.

-

#4

Thanks, guys.

Elroy,

I saw in a textbook «jeep» transliterated as both چيپ and جيب The «jeem» is written with 3 dots to distinguish from Egyptian G and «ba» with 3 dots is a «pa». Is it only Egyptian usage?

-

#5

The letter «v» ڤ is used in words like «Vienna». I haven’t come across any other «normal» word (except for persons’ names) yet. The letter پ is not used in MSA either. I have seen it in the Anglicized word for bariid, which is pusta = پوستة. Is it used in the Arab countries?

-

#6

It also might be noteworthy to say that which Arabic letter is used to transliterate a foreign word with a ‘g’ sound might depend on the position of a ‘g’ in the word and/or the vocal combination of surrounding letters.

As well as ج and ك being used to transliterate غ is also used. For example, the word gorilla has found its way into Arabic as:

غوريلا

(ghuuriila)

This would not work for for the word «English» because a voweless ن followed by a غ results in a difficult pronunciatory liaison.

Unfortunately, I can’t think of any other examples at this time. If I do, I will post them.

-

#7

It might be interesting how they spell the word «garage» in Iraqi and Egyptian Arabic:

كراج (Iraqi)

جراج (Egyptian)

Can someone confirm this or do our Egyptian and Iraqi members disagree?

-

#8

Can someone confirm/deny that چ can be used to transliterate «j» (jeep), it’s probably only for Egypt to make sure it’s not pronounced «g»? Elroy said it looks likes like jiim but this one has three dots. Also, has someone seen پ (pa’) used in Arabic (not other languages)?

Can’t find it any more but Seven Up could be written something like سڤنأپ (?), not sure about the alif but the «ve» and the «pe» were there.

-

#9

Whodunit said:

It might be interesting how they spell the word «garage» in Iraqi and Egyptian Arabic:

كراج (Iraqi)

جراج (Egyptian)Can someone confirm this or do our Egyptian and Iraqi members disagree?

Why not just ﺝﺍﺭﻏ ?

-

#10

Anatoli said:

Can someone confirm/deny that چ can be used to transliterate «j» (jeep), it’s probably only for Egypt to make sure it’s not pronounced «g»? Elroy said it looks likes like jiim but this one has three dots. Also, has someone seen پ (pa’) used in Arabic (not other languages)?

Can’t find it any more but Seven Up could be written something like سڤنأپ(?), not sure about the alif but the «ve» and the «pe» were there.

Maybe they are used in some parts of the Arab world to transliterate words, but generally, I would say it is not used.

Whodunit said:

It might be interesting how they spell the word «garage» in Iraqi and Egyptian Arabic:

كراج (Iraqi)

جراج (Egyptian)Can someone confirm this or do our Egyptian and Iraqi members disagree?

Garage can also be spelled جراش .

linguist786 said:

I thought of that myself, but, I guess, for some reason or another, the pronunciation of garage has become standardized (at least in Egyptian Arabic) with the normal ‘g’ sound.

I did think of another foreign word, though, with gheen. Michigan is normally transliterated as ميشيغان (miishiighaan)

-

#11

Hey guys, so many questions to answer !

I’ll try to help you as much as I can :

I’ll start with the «g» being transliterated as ك :

In Egypt we do not do this, it always looks strange to us seeing the words نكليزية-كراج in some texts, specially those coming from the Levant الشام (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine), for us (Egyptians) they’re إنجليزية — جراج and we pronounce them ingilizeyya — garaaj.

Like the Jeep car, we write it جيب with a regular ج and pronounce it jeep, because we know that’s how it’s called, just like the jeans جينز we pronounce it like in English, and we wite in with regular Arabic ج .

Josh Adkins said:

As well as ج and ك being used to transliterate غ is also used. For example, the word gorilla has found its way into Arabic as:

غوريلا (ghuuriila)

Unfortunately, I can’t think of any other examples at this time. If I do, I will post them.

What about جغرافيا goghrafia (geography) ?

Whodunit said:

The letter «v» ڤ is used in words like «Vienna». I haven’t come across any other «normal» word (except for persons’ names) yet. The letter پ is not used in MSA either. I have seen it in the Anglicized word for bariid, which is pusta = پوستة. Is it used in the Arab countries?

The letters ڤ and پ , and also چ are not widely used in the Arabic transliteration of foreign words. Specially the first two. The sound «v» and «p» do not exist in Arabic, many people find great difficulty pronouncing the «p», so even if it’s transliterated it won’t make much difference.

The word «pusta», for example, is pronounced -at least here in Egypt- bosta. So as you see, there would be need for taking the trouble of transliterating it this way (i.e. with the three dots).

I don’t know about the other countries, but I rarely see Arabic texts with the three dots.

Anatoli said:

Can someone confirm/deny that چ can be used to transliterate «j» (jeep), it’s probably only for Egypt to make sure it’s not pronounced «g»?

In Egypt we don’t pronounce the sound «j» unless for foreign words that we know they are pronounced like that.

Examples: John, Joseph, Jeep, Jeans, Georgia….

And we transliterate them with the ج (with one dot)

Also, has someone seen پ (pa’) used in Arabic (not other languages)? Can’t find it any more but Seven Up could be written something like سڤنأپ(?), not sure about the alif but the «ve» and the «pe» were there.

It’s hard to find it in an Arabic text, because it’s really very rarely used.

I think Seven Up may be one of the very few -if not the only one- to transliterate their name like this, maybe they wanted to make sure people would pronounce the name right. But it’s written like this سڤن أپ

-

#12

I dug this out: Jeep can be written (but there are methods) in Arabic as چيپ with both چ and پ . It’s probably another rarity.

(EDIT: corrected missed letter, thanks Cherine, I lost it when copying from a word processor)

Here they mention letter

چ in Egyptian usage:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_phonology

For rare foreign words with J I would spell

them with چ, so that no-one had doubts how to pronounce them but I see Cherine, that this letter is not too popular in Egypt and other 3-dot letters (except for ث, of course).

Interesting, this situation with borrowed letters is similar to Japanese. In Japanese, like in Arabic, there is no «v». They use «b» or «w» syllables to transliterate and invented the «v» syllables (in katakana syllable alphabet), people still pronounce «b» or «w», even if it’s spelled with the letters.

-

#13

Anatoli said:

I dug this out: Jeep can be written (but there are methods) in Arabic as چيپ with both چ and پ . It’s probably another rarity.

I corrected a little typo, if you don’t mind

Yes, the word Jeep can be written like this, but in Egypt we write it like this جيب and we pronounced it almost like Jeep (almost because of the «p» not the «j» ) most people say jeeb.

Don’t forget that wikipedia is not excatly the perfect source of knowledge

As I said, we know those symbols, but we almost never use them. Specially not on a computer I don’t have them on my Arabic keyboard (little confession : I copy from your post and past them

)

For rare foreign words with J I would spell

them with چ, so that no-one had doubts how to pronounce them but I see Cherine, that this letter is not too popular in Egypt and other 3-dot letters (except for ث, of course).

We can’t compare these symbols with ث which is a «genuine» Arabic letter.

And you forgot the ش which also has 3 dots

-

#14

You’re right Cherine, they are not on standard Arabic keyboard. I agree, these Persian letters are not worth using in Arabic. I used SC UniPad to enter them.

elroy

Moderator: EHL, Arabic, Hebrew, German(-Spanish)

-

#15

Let me talk about what I’ve seen in Palestinian publications:

Generally, we do not use ك to transliterate «g,» but I have seen it done.

The three characters ڤ, پ, and چ are used relatively frequently, to transliterate «p,» «v,» and «g» (not «j») respectively. Otherwise, one just uses, ف, ب, and ج (or ك). Note that this is done only when a word is foreign and the «p,» «v,» or «g» sound is pronounced by those who can. The word «bosTa» does not count, because it is pronounced with a «b» by everybody, even those who can pronounce the sound «p.» This word can almost be considered an Arabic word. Such is not the case with foreign names, for example, which are more likely to be transliterated using non-Arabic characters. I hope the distinction is clear.

-

#16

Strange that چ and ج have almost the reverse usage (transliteration) in Egypt and Palestine

I saw in a textbook Jakarta written with a چ in Egyptian context to represent J sound.

Is another Persian letter گ (gaf) used at all? It differs from «kaf» by an extra stroke above.

-

#17

See post #3, but only for colloquial,pronounced ch.

-

#18

Anatoli said:

Strange that چ and ج have almost the reverse usage (transliteration) in Egypt and Palestine

![Smile :) :)]()

Interesting -and intelligent- remark Anatoli I’ve never thought of that

Is another Persian letter گ (gaf) used at all? It differs from «kaf» by an extra stroke above.

I’ve never seen it in any transliteration, I think it’s because it may be mistaken for a ka (kaf+fa7a كـَـ)

-

#19

cherine said:

I’ve never seen it in any transliteration, I think it’s because it may be mistaken for a ka (kaf+fat7a كـَـ)

Only if it is the initial letter. The other forms of the gaaf look very different from the Arabic letter kaaf + fat7a.

-

#20

Anatoli said:

SC Unipad software has some Arabic symbols for which I haven’t seen any description

Try the Unicode site (it is Unicode.org but I may not post url’s yet) and the file U0600-arab.pdf. Lots of «Arabic» letters you perhaps haven’t seen before, from Pashto, Dargwa, old Malay, Uighur… Explanations included.

-

#21

I don’t know about the other countries, but I rarely see Arabic texts with the three dots.

Reviving an old thread…

Dear Cherine, I send you a delightful example here. These are «Caprice» caramel sweets from Algeria (at first I was wondering if I was learning to read Arabic properly, because of the Persian پ !)

-

#22

Dear Cherine, I send you a delightful example here. These are «Caprice» caramel sweets from Algeria (at first I was wondering if I was learning to read Arabic properly, because of the Persian پ

!)

Chère Nanon,

As I said previously, in some countries we sometimes use the b with 3 dots to transliterate the sound «p» that doesn’t exist in Arabic.

But the use of this symbol is not as commonly used in Egypt as the ج with the 3 dots. We use the ج for (g) and the one with 3 dots for the sound (j), although not all the time.

-

#23

I found an interesting usage for Persian letters پ and ڤ in Arabic, even if they miss on keyboards. They are actually used, less ambiguously to render Roman letters P and V. Of course, B can be called بيه or بي (same as B), PC — بي سي, Pocket PC — بي سي جيب. V can also be called وي and في, e.g DVD is دي في دي.

Arabic Wikipedia has some info on how Roman or English letters are called in Arabic.

I can confirm that Hans Wehr dictionary occasionally uses additional letters for some words like «virus», «jeep», I’ve seen about 10 examples after a short search but they are not common on the web for the reasons discussed before.

-

#24

Just Iraq. It’s rarely used in the Gulf.

Iraqis even spell قال as كال, which I’ve always felt was unnecessary.

In Saudi Arabia it’s common to use ق, at least by ordinary people on the web (as opposed to formal writing). There’s even a brand of food products called قودي (from «Goody»).

-

#25

I saw these letters (some of them borrowed from Fārsi) in texts from different countries from mashreq to maghreb: گ for g(ale), پ for p and most often ج for j(oke); sometimes seen also: ژ for zh (IPA [ʒ], like in pleasure. or je in French, ж or ž in many languages) and ڤ for v.

I found them most often in ’Irāqi transcriptions of songs or popular tales, but not only — e.g. in (often poor) Morrocan and Algerian phrasebooks to “learn” Tamazight, or in subtitles on the Moroccan تمازيغت or the Algerian قناة الامازيغ 4 TV channels (often to impose the Arabic script i.o. Tifinaɣ…).

For my part, I use a

Persian

keyboard for Mac computers to get all characters you can find in languages using the Arabic or derived ابجدیة. The sole language which is difficult to write with this keyboard (and others, too) is Uyghur, especially when it comes to words beginning with a vowel, which are written with an initial —ئـ, which often appears as an isolated ئ, depending on the encoding your PC uses.

Another point is about the use of گ or ق to transcribe the “hard” g sound (apart from the most populous part of Egypt), I noticed that it depends more on the period than on the country factor: twenty years ago it was still ق which was used, as this is the way the qāf is pronounced in many dialects (e.g. the name قرفتي in Morocco, pron. like /Gorfti/), then, fifteen years ago, the گ appeared here and there, except that ݣ is used in Morocco in some well-defined cases (official translitteration of “Berber” place names like إنزڭان or unofficial written darija).

A few words still to say that if Wikipedia is definitively not a fully reliable source — despite their policy known there as “

non-personal point of views

” —, their entry about the Arabic alphabet can be a helpful start for beginners not willing to buy good grammars and learning books.

Last edited: Mar 28, 2010

, type

, type