In 1929 an RAF crew took aerial shots of the site of the old Roman town of Venta Icenorum around the church of Caistor St Edmund near Norwich. The photographs revealed an extensive road network and soon the archaeologists moved in. During their excavations they came across a large early Anglo-Saxon cemetery with burials dating from the 5th century.

In the cemetery they found some cremation urns as well as pots with possessions in. One of these was full of bones – but they were not human remains. Most were sheep knuckle bones and probably dice or other game pieces. But amongst them was a bone that was and still is of historical importance.

It was a bone from a Roe deer and upon it there were runic inscriptions:

The runes were old German/ old english runes and spelt this word:

Which means Raihan. What is Raihan? Well the ‘an’ in old German meant ”belonging to or from” and the Raih is believed to be a very early version of the word ROE. So this inscription which has been dated to circa 420 AD means “from a roe”.

It is not uncomon in the Saxon period to find similar bones from other animals with writing telling us which beast it is from.

So what we have here are the possessions of a man or woman from the VERY first years of Anglo-Saxon settlement of East Anglia buried in a cemetery that would have been very new within or close to a decaying Roman town. What we also have is the VERY FIRST word written in what would one day become England in the language which would one day be called English.

What we see here are the scrapings of one of the first of the mercenaries who crossed the north sea on hearing the call from the Britons for fighters to help protect Britannia from the Picts and Irish. He and thousands like him stayed on to carve out a nation.

There is more on this word and 99 other ones that form part of our history in The Story of English in 100 words by David Crystal. Its a fascinating book and I very much recommend it.

I find this evidence of the first written word in English fascinating and quite romantic really. I write novels about the early Anglo-Saxon period — always striving to bring back to live people who died 14 centuries ago. This to me is a tangible relic of one of those people. To find out more about my books click here.

The earliest written records of English are inscriptions on hard material made in a special alphabet known as the runes. The word rune originally meant ‘secret’, ‘mystery, and hence came to denote inscriptions believed to be magic. There is no doubt that the art of runic writing was known to the Germanic tribes long before they came to Britain. The runes were used as letters, each symbol to indicate a separate sound. The two best known runic inscriptions in England is an inscription on a box called the «Franks Casket» and the other is a short text on a a stone known as the «Ruthwell Cross». Both records are in the Northumbrian dialect. Many runic inscriptions have been preserved on weapons, coins, amulets, rings. The total number of runic inscriptions in OE is about forty; the last of them belong to the end of the OE period. The first English words to be written down with the help of Latin characters were personal names and place names inserted in Latin texts. Glosses (заметки) to the Gospels (Евангелие) and other religious texts were made in many English monasteries, for the benefit of those who did not know enough Latin (we may mantion the Corpus and Epinal glossaries in the 8th c. Mercian).OE poetry is famous for Bede’s HISTORIA ECCLESIASTICA GENTIS ANGLORUM, which is in Latin, but contains an English fragment of 5 lines. There are about 30,000 lines of OE verse. OE poetry is mainly restricted to 3 subjects: heroic, religious and lyrical. The greatest poem of that time was BEOWULF, an epic of the 7th or 8th c. It was originally composed in the Mercian or Nuthumbrian dialect, but has come to us in a 10th c. West Saxon copy. OE prose: the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLES. Also prose was in translating books on geography, history, philosophy from Latin. TE LIVES OF THE SAINTS by Alfric, the HOMILIES by Wulfstan (passionate sermons – страстные поучения). OE Alphabet. OE scribes (писцы) used two kinds of letters: the runes and the letters of the Latin alphabet. The runes were used as letters, each symbol to indicate a separate sound. Besides. A rune could also represent a word beginning with that sound and was called by that word. In some inscriptions the runes were found arranged in a fixed order making a sort of alphabet. After the first six letters this alphabet is called futhark. The runic alphabet is a specifically Germanic alphabet, not to be found in languages of other groups. The letters are angular (угловые), straight lines are preferred, curved lines avoided: this is due to the fact that runic inscriptions were cut in hard material: stone, bone, or wood. The shapes of some letters resemble those of Greek or Latin, others have not been traced to any known alphabet. Some OE letters indicate two or more sounds, even distinct phonemes. The letters could indicate short and long sounds. The length of vowels is shown by a macron or by line above the letter; long consonants are indicated by double letters.

|

Вычисление основной дактилоскопической формулы Вычислением основной дактоформулы обычно занимается следователь. Для этого все десять пальцев разбиваются на пять пар… |

Расчетные и графические задания Равновесный объем — это объем, определяемый равенством спроса и предложения… |

Кардиналистский и ординалистский подходы Кардиналистский (количественный подход) к анализу полезности основан на представлении о возможности измерения различных благ в условных единицах полезности… |

Обзор компонентов Multisim Компоненты – это основа любой схемы, это все элементы, из которых она состоит. Multisim оперирует с двумя категориями… |

I answered a similar question on Linguistics SE, which I will plagiarize in part here:

How etymological research is done has varied through time. In the case of the «New English Dictionary» (the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary), work started on it in 1857. Then:

[I]n January 1859, the Society issued their ‘Proposal for the publication of a New English Dictionary,’ in which the characteristics of the proposed work were explained, and an appeal made to the English and American public to assist in collecting the raw materials for the work, these materials consisting of quotations illustrating the use of English words by all writers of all ages and in all senses, each quotation being made on a uniform plan on a half-sheet of notepaper, that they might in due course be arranged and classified alphabetically and by meanings. This Appeal met with a generous response: some hundreds of volunteers began to read books, make quotations, and send in their slips to ‘sub-editors,’ who volunteered each to take charge of a letter or part of one, and by whom the slips were in tum further arranged, classified, and to some extent used as the basis of definitions and skeleton schemes of the meanings of words in preparation for the Dictionary.

An Appeal to the English-Speaking and English-Reading Public to Read Books and Make Extracts for The Philological Society’s New English Dictionary

One significant contributor to the early OED worth mentioning is William Chester Minor (1834 – 1920). He was insane, but he was also good at doing etymological research. His story, graphic in some parts, can be found here:

What made him so good, so prolific, was his method: Instead of copying quotations willy-nilly, he’d flip through his library and make a word list for each individual book, indexing the location of nearly every word he saw. These catalogues effectively transformed Minor into a living, breathing search engine. He simply had to reach out to the Oxford editors and ask: So, what words do you need help with?

The «Reading Programme» is still used by the OED, although the methodology is different. The books are still read all the same but here’s what happens next according to a freelance researcher for the OED:

I then consult OED Online to determine whether the word or phrase is in the Dictionary: if it is not, I submit it as a ‘not-in’, and if it is, I decide whether its form or context is important enough to warrant its submission. If it does qualify, I enter the information into tagged fields in an electronic file that has been set up in a standard format. When I have finished the reading, I submit the file to Oxford or New York, where the records are incorporated into OED‘s working database for consideration by the editors, along with thousands of paper citation slips, as they proceed through the current revision. Yes, some of my finds are still submitted as paper slips—a reminder of OED‘s long heritage—but, electronic or paper, I can hardly imagine a better job.

The quotations were collected in a machine readable format for the first time in 1989. The 1990 UK Reading Programme captured material electronically. (Note that the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary came out in 1989.)

In addition to this, the OED now utilizes several online databases of texts, such as Early English Books Online, Eighteenth Century Collections Online, and some newspaper databases.

I have access (for now) to several of these paywalled databases through my college.

If you do your own research with databases (many people use the free Google Books), it’s often easy to find antedatings for pages that haven’t been updated for the third edition of the OED. Updates to the OED3 started in 2000 and continue to this day: it’s a huge dictionary and updating takes time.

See also:

- OED: Researching the Language

Linguistics/English 395,

Spring 2009

Prof. Suzanne Kemmer

Rice University

Course Information

Course Schedule

Owlspace login page

Spelling and Standardization in English: Historical Overview

Writing systems and alphabets in England

English has an alphabetic writing system based on the Roman alphabet

that was brought to Anglo-Saxon England by Christian missionaries

and church officials in the 600s. An earlier Germanic writing system

called runes, also alphabetic and originating ultimately from the same

source as the Roman alphabet, was used for more limited purposes

(largely incantations, curses, and a few poems) when the tribes were

still on the continent and also after their migration to Britain,

up until Christianization.

Alphabetic writing systems are based on the principle of representing

spoken sound segments, specifically those at the level of consonants

and vowels, by written characters, ideally one for each sound

segment. Crucial elements of the sound stream of a message are thus

‘captured’ by a linear sequence of marks that can be «sounded out» to

recapture the message by means of its sounds. The entire sound stream

is not captured, but enough of it is to provide a prompt for lexical

recognition. (Other kinds of writing systems are based on written

representation of other linguistic units such as syllables, words, or

some mix of these.)

The Roman alphabet and Anglo-Saxon

The Roman alphabet, being designed for a language with a very different

phonological system, was never perfectly adapted for writing English

even when first used to represent Anglo-Saxon. The first monks

writing English using Roman letters soon

added new characters to handle the extra sounds. For example, the

front low vowel /æ/ of Anglo-Saxon was represented by a ligature of a

and e, forming a single written character called ash.

They also added a

few runic characters to the alphabet

to represent consonant sounds not

found in Latin or its Romance descendents, such as the fricatives

thorn þ, eth ð, and yogh ȝ (a voiced palatal or velar

fricative, represented by a character that looks

somewhat like a 3). Later on in the medieval

period these runic characters

were replaced with digraphs, two-letter symbols such

as th, sh, and gh. The letters in these digraphs do not have their usual

values, but are used as a complex to indicate single sounds.

Writing in Anglo-Saxon: Variation and incipient standardization

Norms for writing words consistently with an alphabetic character set

are collectively called orthography. Consistency in writing was never

absolute in Anglo-Saxon because the whole system was new and norms for

writing words in a consistent way took time to develop. It is not easy

for writers to remember a single orthographic representation, called a spelling,

for a word; yet this is what is required for standardization, unless

there is a perfect one-to-one correspondence between phonemes and

graphemes, which is an ideal rarely reached with alphabetic systems.

Writers seem to prefer to produce

written forms they have seen before for specific words, even if there

is not a good match between written characters and sounds.

From the reader’s perspective, we might think that simply pronouncing

a word based on the prompts provided by the graphemes would be enough

to allow a reader to produce a spoken message matching the written

form. Yet it turns out that producing the sound of an utterance by

reading it off from the graphemes is no simple cognitive task.

Getting a pronunciation out of alphabetic writing requires people to

analyze the sound string down to the level of component sounds. Yet

this type of phonemic analysis is apparently not an obvious or natural

one for humans; it needs to be taught intensively before it can be

done fairly automatically and that is one reason why acquisition of

literacy at an early age is stressed in cultures with alphabetic

writing. It takes a lot of practice to reliably decode messages from

alphabetic writing. Some of those who try to learn to read alphabetic

writing never master it because they can’t separate the speech string

into individual segments, which are clusters of vocal gestures in

consonants and vowels, in this way. Syllables apparently are a more

natural unit for humans to perceive and hence code (write) and decode

(read) by means of marks on a page.

Reading is also apparently swifter the more familiar the form of the

written words are. A word in a spelling the reader has seen before is

easier and quicker to recognize than one not seen before. Also reading

is apparently quicker the less variation there is in the forms of

words. (But there is much individual variation on this last point.)

The manuscripts were apparently normally read aloud, rather than

internally as most reading is now done. That means the process of

reading was

slow enough that variation in the visual forms did not seriously detract from

production of the sounds as prompted by the written characters. With

reading ‘to oneself’, the process is potentially swifter once the

reader has mastered the system; but variation can then slow it down.

If there was ever consistency at the start of the use of the Roman

alphabet for representing Anglo-Saxon, it began to lessen immediately.

The novelty of the alphabetic system as a technology, the lack of

fixed norms for written representations, and the changes over

time of the language were

all forces that led to greater divergence of the

written forms from the spoken string. Add to that dialect variation:

Some of

the scribes came from outside Wessex, and even when they tried to

write so as to approximate Wessex sounds, their own local

pronunciations often affected the characters they wrote.

Scholars observe the dialect features of individual manuscripts to

gain clues about where the manuscript was composed and/or copied.

There was at that time no strong countervailing force leading toward

standardization, i.e reduction of variation, such as would come

later. Spellings are so variable that to lessen the difficulties

modern readers may have, Old English texts are generally «normalized»,

or printed in accordance with what scholars think is a good

representative form for each word.

Manuscripts were produced in fairly large numbers by monks copying originals

using quill pens, ink, and, as the writing surface, prepared sheepskins (parchment) or the

much more expensive and high quality calfskins

(vellum).

The physical technology of this system hardly changed for 800

years. During that time some norms arose for spelling (incipient

standardized spellings, although still by our standards highly

variable), but the sounds of the language were changing faster. As

usual with written languages, norms for writing lagged behind those

for pronunciation, thus providing another source of divergence of the

written form from the spoken.

Although the royal court was in Winchester, other regional centers of

government and/or learning arose or continued developing, such as

York, Peterborough, Jarrow — and at the end of the Anglo-Saxon period,

just before the conquest, London. The first three of these centers

tended to have their own orthographic norms based on Northern

pronunciations. Thus there was no single center for the development of

orthographic norms, although the royal court in the south exerted a

powerful force for normalization.

The period after the conquest: Spelling during the Middle English period

The Norman Conquest and its aftermath changed the entire social and

governmental structure. It also affected spelling greatly, for various

reasons. The most obvious is that the use of English in written

documents was greatly reduced. English was no longer the dominant

language for law and government, so the tendency toward

standardization for Anglo-Saxon writing was essentially stopped in

its tracks. Some English was still written, but far less than

before. With no schools and monasteries teaching ways of writing Old

English, any incipient norms were swept away and people hardly

literate in the language just tried to

spell as the words sounded, with predictably irregular results.

Second, after the conquest many scribes were French or French-trained.

Their norms for representing sounds were different in many

respects. The letter c, for example, was used in French to spell an

/s/ sound in many loanwords of Latin origin; the letter c in the

Roman writing system represented a /k/, but a sound change in Latin

turned /k/ into /s/ before front non-low vowels. (Thus Latin

civitas /kiwitas/ evolved into French cité, from

where we get our word city.) From many instances like this

one, the use of a single letter c to represent the radically different

sounds /k/ and /s/ came into the English spelling system

(and persists to this day). The /s/ variant developed by assimilation

and weaking of the original /k/ in particular contents. A similar

sound change when Latin was changing into the Romance languages gave

rise to the use of the letter g for both a /g/ sound and a /dȝ/

sound, as in goat vs. gesture. Like the split of the

early /k/ sound into /k/ and /s/, this split of Latin /g/ was induced

by assimilation of the /g/ before front non-low vowels, in which the

sound took on the frontness of the following vowel. And like the

split of /k/, the orthographic mismatch of the letter /g/ and the

sounds it stood for was imported into English via the introduction

during Middle English of

large numbers of French loanwords with the new /dȝ/ sound in

them.

Third, the conquest brought about a change

in the dialect taken as the standard.

The seat of the royal court and government moved to London

after the conquest. (Edward the Confessor built his beloved

Westerminster Abbey in

Westminster, then just down the river to the west of the Roman and

Saxon settlements of London, and used buildings around the abbey as a

seasonal court.

The Conqueror built a whole court complex around the abbey,

which thus became the center of government.)

As a result the new pronunciation norms

were derived from London English and not from ancestral Wessex which

was in the West Country. Many manuscripts were re-copied into the

newly important London dialect of the ruling classes. Older spelling

norms were abandoned for new ones based on London pronunciations.

Writing had been used for governmental purposes from the beginning of

the Anglo-Saxon era, but for a long time its chief use

remained in the church. After the conquest it was used more and more

for governmental purposes, centered in the royal court and

law courts. The Court of Chancery in London became the seat of

official record-keeping, and by the 1300s spelling norms were

developing noticeably, in a written variety called Chancery English.

The rise of two important centers of learning outside London, Oxford

and Cambridge, by the 1300s affected written norms as well. These

towns had somewhat different dialects, but they were still relatively

close to each other and to the court, and many of the spelling norms

developed there could also be applied to writing the London

dialect. The triangle of London-Oxford-Cambridge, with its revolving

scholarly and clerical workforce, became a large and important center

of developing orthographic norms.

Printing and the beginnings of the information revolution

The advent of printing in the late 1400s drastically changed the speed

at which manuscripts could be produced and therefore disseminated, and

the adoption of paper also helped to make written documents cheaper and more

widespread. These factors encouraged the growth of record-keeping and

bureaucracy and the continued growth in importance of the Court of

Chancery and Chancery English. Property records, tax-collecting and

other financial records, laws, and records of crime and punishment

all burgeoned in the 1500s.

The rise of schools, designed to train not

only religious workers but also secular clerical workers for

government, made it possible to train larger numbers of people in

literacy and thereby also further spread the developing norms for

orthography. The growth of London and its role in public institutions

ensured its importance as the center of a linguistic standard for the

developing nation. Standard written norms based on London English developed and

were used even where local pronunciations were hardly affected by

the sounds of spoken London English. Documents moved around in far

greater numbers than people and thus could influence the norms of the

region more easily than the spoken dialect features of travellers.

The growth of a professionalized class of printers outside of the

direct control of church and government led to the role of printers in

setting norms of writing and spelling. Printers had a strong interest

in standardization to reduce variation and hence make the printing

process easier. The printing profession evolved into the profession of

publishing, and publishers have been important ever since in the

setting of written standards.

During the 1500s, a major upheaval in the pronunciation of English

vowels, the Great English Vowel shift, spread through the

speech community and tore the conservative written

forms of the long vowels away from their changing pronunciations, leaving

English with a set of letter-to-written vowel correspondences

different from everywhere else in Europe, as well as internal

variation that bedevils readers in pairs like divine, divinity.

At about the same time, many inflectional endings were reduced and

finally eliminated, notably many final unstressed e’s. These «silent

e’s» were continued in the spelling system but repurposed as a tool to

signal the value of the long vowels changed in the Great Vowel

Shift (e.g. in mate, name, while etc.). Other sounds were reduced then eliminated, such as the k’s and

g’s in the old clusters kn and gn (as in knight and

gnat) and some of the remnants of Old English yogh, the old

velar fricative (as in neighbor and bough). The result is

the numerous set of «silent letters» that learners find so maddening.

By the late 1500s, under the impetus of printing the tremendous

variety of spellings in written English had shaken down into a far

smaller set of variants, and a great part of the outlines of the

modern orthography was in place. Changes in orthographic norms

slowed considerably, and Modern English was left with a spelling

system from an earlier period of its history: essentially it is a

normalized Middle English system. The result is a set of letter-to-sound

mismatches greater than those of elsewhere in Europe, even in some

respects greater than those of French, whose spelling was codified a

little later.

The Reformation and Renaissance

In the late 1500s England became a Protestant country. As part of the

new doctrine and its administration, new documents were needed such as

liturgies for the recently-established Church of England, the Book of

Common Prayer, and above all, English translations and copies of the

Bible.

The push for an accessible version of Scripture, which meant an

English Bible, began a few centuries earlier but was thwarted until

the church and government adopted the basic tenets of the Reformation.

A number of versions of the scripture in English were produced in the

late 1500s, but the culmination of this trend was the King James Bible

of 1611. This was the most influential and most widespread religious

document of the age, and the norms adopted by the translators and

printers of this Bible had an immense influence on writers.

Dictionaries and Other Linguistic Reference Materials

With the growing use of written language, the need was felt for

materials that presented aspects the language in a way that could be

looked up by all who desired information about the language: first,

non-native speakers and later also native speakers of the language who

wanted to know about newly developed parts of the language that were

not part of every native speakers’ knowledge. The first

dictionaries were essentially lists of «hard words», particularly the

large number of new loanwords from the Classical languages and also

from the new colonies overseas. By the 18th century dictionary-writing

was becoming a recognized activity and scholars and other learned

men were being commissioned by publishers to write such materials.

Elsewhere in Europe language academies were established to codify and

normalize all aspects of language. This trend did not catch on in

English-speaking lands and there has never been an officially

recognized academy for standardization either in Britain or the

U.S. There was however an English version of the trend towards

«language purification» that swept European countries through the

Renaissance and Enlightenment. (This trend never fully died out in the

English speaking world, and we see its echoes in prescriptivist

movements that seek to minimize foreign influences, which are viewed as

threats, probably for nationalistic and ethnic-based reasons. Since

languages do not degenerate but only change with the needs of their

speakers, it is difficult to see how one language could actually

be threatened as long as it has speakers—especially one such as

English with such a numerous body of speakers. A language can be threatened

or endangered only if it ceases to be used at all.) Jonathan Swift was a vocal

proponent of English language purification, but as is usual with

purifiers, his knowledge of the history of the language was faulty and

his beliefs about the reasons for particular norms and why they had to

be upheld were irrational.

The publication of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English

Language was a milestone in the development of dictionary and

reference materials. It adopted a more-or-less descriptivist stance

which is very modern, and at odds with the prescriptive views of

earlier producers of dictionaries. Johnson’s recognition of change as

a normal process and his refusal to see it as degeneration was novel

and important.

By the time of Johnson’s dictionary, the spelling

system in place was recognizably that of current Modern English, with

only a few orthographic peculiarities such as the spelling of

show as shew and the use of the «long S» character

(easily confused with the f of that time). Probably the typefaces in

use at the time give more appearance of difference with modern texts

than any of the remaining spelling differences between 18th century

English and contemporary British English.

The political independence of the United States in the 1770s led to a

push towards identifying distinguishing cultural factors. Language was

an obvious way of distinguishing Americans from Britons, since a

recognizable set of American pronunciation features had already

developed. However, instead of using pronunciation differences to try

to develop a separate written standard, Noah Webster wrote a

dictionary containing some regional, American-dialect based

definitions to set it apart, and also introduced into his dictionary

and other writings a set of

spellings that put a distinctive stamp on American orthography without

changing it too much for mutual intelligibility. In other words, most

of the spelling conventions that had solidified in the British

standard written form by the early 19th century were maintained by Webster,

but he added a few systematic differences:

Using -ize instead of -ise for verbs derived from Greek

verbs in -izein; eliminating u in the suffix -our

(thus moving it away from the French-derived spelling of Middle

English to a spelling somewhat more in line with pronunciation on both

sides of the Atlantic), the replacement of -re in French loans

by -er (centre/center, theatre/theater) and a few other

simplications.

Movements advocating more drastic spelling reform of English emerged in

the 18th century, and there are periodic resurgences of this trend,

which represents an attempt to introduce efficiency and save time for

new learners.

Benjamin Franklin devised an alphabetic system largely keeping

English orthography the same but introducing single symbols for the

current digraphs, and additional symbols for vowel distinctions not

systematically represented in the writing system. (See link under

this essay.)

George Bernard Shaw was a passionate advocate of total spelling reform

and left his entire estate to be devoted to this project.

Systems for extreme changes of spelling, however rational, do not

seem to gain much ground in the English speaking world, probably

because updating the spelling to match pronunciation would make older

documents unintelligible for those learning only the new system, as

well as giving trouble as to how to take account of variations in

pronunciation. Another objection is that historically-oriented people (admittedly, a minority)

would not like to see the history of words containing fossil

traces of earlier forms (i.e. antiquated spellings)

erased by updating to modern rational

spellings.

The existing system has now gone on so long that it is difficult to

turn the clock back too much at once, but only by doing so can the

proponents gain their objective of an entirely rational correspondence between

letters and sounds.

Some other European nations make small orthographic adjustments every

generation or so, and thus keep their spelling gradually evolving

along with (or actually a little bit behind) the pronunciation. The

Scandinavian languages are well-known for this strategy. There was a

spelling reform in Germany in 1989 or so, but it was not a drastic

one, although portrayed as dire by some. Recently major national

newspapers have declared their intention to go back to the old system,

leaving language users in confusion about which standard to adopt.

Modern trends for standardization

Current orthography represents two major centers of standardization:

British and American English. The British standard held sway

throughout the world until very recently, when some other countries

began to first accept and then to teach American orthography and

lexical choices. (Grammatical features have been adopted with

more reluctance it seems.) Pronunciation variants are spread auditorily

rather than via writing, but the same changeover from British

to American norms appears to be occurring.

In the English-speaking world beyond Britain and the U.S., the norms

are coming into flux in some places. The spelling usages of former

colonies Canada and Australia are undergoing change as the influence

of the U.S. is felt more and more. These countries were tied to the

mother country, Britain, longer, and have maintained largely British

orthography, but proximity (in the case of Canada) and cultural

influence are exerting pressure on the norms speakers choose. The use

of U.S. spelling variants seems to be on the rise in the populace in

these countries, despite resistance of schools and government. In

other former colonies such changes are less obvious, but the same

trend may be active.

The spread of electronic communication in the form of computers and

phone texting have provided a large number of abbreviatory

conventions. The enforcers of spelling norms, schools and publishers,

have so far maintained the current orthographic standards in printed

documents. But because spelling norms are hard to acquire given all

the spelling-pronunciation mismatches, and writing has become so

democratized through these technologies, the use of non-standard

spellings (not just abbreviations) is increasingly widespread. Such

changes in usage patterns are bound to have some effect on the written

language ultimately, just as speaker’s usage of words eventually

affects what are considered conventional norms. It is still too early

to tell how these effects on the written language will play

out. Publishing itself as an industry feels endangered by the tidal

wave of un-edited electronic publication on the internet. What happens

to publishing as an industry will probably affect how quickly new

orthographic norms are adopted, since publishing is one of the major

conservative forces of orthographic standardization in the modern

world. The others, schools, government, and church, seem less

powerful in determining the form of the documents that are actually

produced on paper.

Useful Sites on Spelling and Spelling Reform

Ben

Franklin’s phonetic alphabet for reformed spelling. (found by

Travis Smith) Benjamin Franklin

developed a keen interest in spelling reform and this is his system for

a more rational spelling system for English. He even took the trouble

to commission a type foundry to

make the new letters needed for typesetting in his proposed system. (He was a

printer/publisher after all.) He wrote an article about it in 1768

when he was living in London. But then he seems to have lost interest

in the project, possibly because he could not interest anyone else in it.

Writing

system reforms and revolutions (in many languages). In addition to

links on writing and spelling reforms in a wide variety of languages, this site

also includes some nice links to sites about writing systems, the

relation of language to writing systems, spelling games and other

curiosities, and issues related to spelling reform and literacy.

Wikipedia on

English spelling reform. An overview of reasons for and against

spelling reform in English. The arguments against are under the

sections «Obstacles» and «Criticism». There is also a short list of

campaigns for spelling reform in English.

Wikipedia on

spelling reform. An overview of reasons for reform, but arguments

against reform are not given in depth. The overall point of view in

this article, unlike in the one above,

is pro-reform. This site also has short

descriptions of reform efforts for a number of languages.

[Students: If you have any other links on spelling, send them to me.]

© 2009 Suzanne Kemmer

Last modified 17 Mar 2009

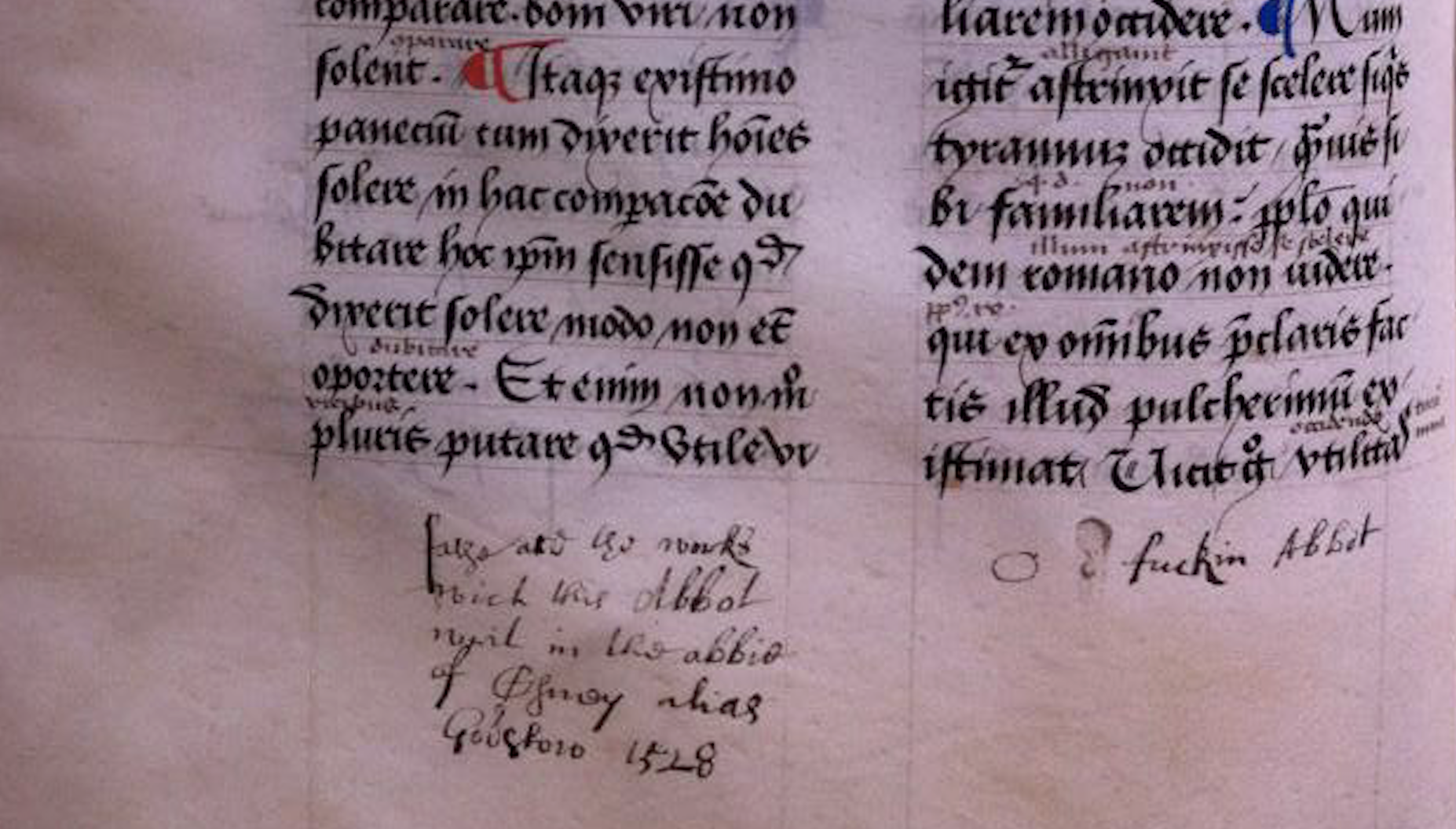

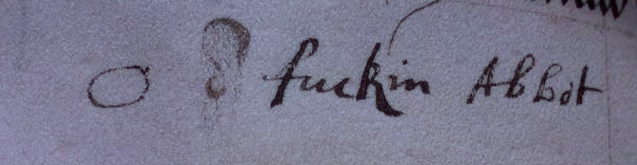

English speakers enjoy what seems like an unmatched curiosity about the origins and historical usages of their language’s curses. The exceedingly popular “F word” has accreted an especially wide body of textual investigation, wide-eyed speculation, and implausible folk etymology. (One of the term’s well-known if spurious creation myths even has a Van Halen album named after it.) “The history begins in murky circumstances,” says the Oxford English Dictionary’s site, and that dictionary of dictionaries has managed to place the word’s earliest print appearance in the early sixteenth century, albeit written “in code” and “in a mixed Latin-and-English context.” Above, you can see one of the few concrete pieces of information we have on the matter: the first definitive use of the F word in “the English adjectival form, which implies use of the verb.”

Here the word appears (for the first time if not the last) noted down by hand in the margins of a proper text, in this case Cicero’s De Officiis. “It’s a monk expressing his displeasure at an abbot,” writes Katharine Trendacosta at i09. “In the margins of a guide to moral conduct. Because of course.” She quotes Melissa Mohr, author of Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing, as declaring it “difficult to know” whether this marginalia-making monk meant the word literally, to accuse this abbott of “questionable monastic morals,” or whether he used it “as an intensifier, to convey his extreme dismay.” Either way, it holds a great deal of value for scholars of language, given, as the OED puts it, “the absence of the word from most printed text before the mid twentieth century” and the “quotation difficulties” that causes. If you find nothing to like in the F word’s ever-increasing prevalence in the media, think of it this way: at least future lexicographers of swearing will have more to go on.

To view the complete manuscript page, click here. The document seemingly resides at Brasenose College, Oxford.

via io9

Related Content:

Steven Pinker Explains the Neuroscience of Swearing (NSFW)

Stephen Fry, Language Enthusiast, Defends The “Unnecessary” Art Of Swearing

George Carlin Performs His “Seven Dirty Words” Routine: Historic and Completely NSFW

Medieval Cats Behaving Badly: Kitties That Left Paw Prints … and Peed … on 15th Century Manuscripts

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.

.jpg)