Released in 1979 by Micropro International, WordStar was the first commercially successful word processing software program produced for microcomputers. It became the best-selling software program of the early 1980s.

Its inventors were Seymour Rubenstein and Rob Barnaby. Rubenstein had been the director of marketing for IMS Associates, Inc. (IMSAI). This was a California-based computer company, which he left in 1978 to start his own software company. He convinced Barnaby, the chief programmer for IMSAI, to join him. Hw gave Barnaby the task of writing a data processing program.

What Is Word Processing?

Prior to the invention of word processing, the only way to get one’s thoughts down on paper was via a typewriter or a printing press. Word processing, however, allowed people to write, edit, and produce documents by using a computer.

First Word Processing Programs

The first computer word processors were line editors, software-writing aids that allowed a programmer to make changes in a line of program code. Altair programmer Michael Shrayer decided to write the manuals for computer programs on the same computers the programs ran on. He wrote a somewhat popular software program called the Electric Pencil in 1976. It was the actual first PC word processing program.

Other early word processor programs worth noting were: Apple Write I, Samna III, Word, WordPerfect, and Scripsit.

The Rise of WordStar

Seymour Rubenstein first started developing an early version of a word processor for the IMSAI 8080 computer when he was director of marketing for IMSAI. He left to start MicroPro International Inc. in 1978 with only $8,500 in cash.

At Rubenstein’s urging, software programmer Rob Barnaby left IMSAI to join MicroPro. Barnaby wrote the 1979 version of WordStar for CP/M, the mass-market operating system created for Intel’s 8080/85-based microcomputers by Gary Kildall, released in 1977. Jim Fox, Barnaby’s assistant, ported (meaning re-wrote for a different operating system) WordStar from the CP/M operating system to MS/PC DOS, the by then a famous operating system introduced by Microsoft and Bill Gates in 1981.

The 3.0 version of WordStar for DOS was released in 1982. Within three years, WordStar was the most popular word processing software in the world. However, by the late 1980s, programs like WordPerfect knocked Wordstar out of the word processing market after the poor performance of WordStar 2000. Said Rubenstein about what happened:

«In the early days, the size of the market was more promise than reality…WordStar was a tremendous learning experience. I didn’t know all that much about the world of big business.»

WordStar’s Influence

Communications as we know it today, in which everyone is for all intents and purposes is their own publisher, would not exist if WordStar had not pioneered the industry. Even then, Arthur C. Clarke, the famous science-fiction writer, seemed to know its importance. Upon meeting Rubenstein and Barnaby, he said:

«I am happy to greet the geniuses who made me a born-again writer, having announced my retirement in 1978, I now have six books in the works and two [probables], all through WordStar.»

According to Frank Bruni, a columnist for the New York Times, one of the most influential classes he ever took was not the one where he first read Plato or discovered The Great Gatsby or learned to appreciate Modern Art or Bach Sonatas. The class that so influenced Bruni was—drum roll please—the summer school program he attended as a teenager to learn how to type.

In an essay titled “What I Learned in Secretarial School,” Bruni extolled the drudgery and humility that was entailed in learning how to properly place one’s hands on a typewriter’s keyboard and type, without looking at the keys, phrases like “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.”

According to Bruni, who has been a Times White House reporter, Rome bureau chief and restaurant critic and is the author of three best-selling books—his ability to get started as a writer owed much to his fluid abilities as a typist. “I developed a reputation as a fleet writer when really I was a fleet typist. The talents were somehow intertwined. Confidence in my typing gave me confidence in everything else.”

Fast forward nearly four decades, and you might be asking “Why wasn’t he allowed to look at the keys?” or “Who cares about the quick fox and the lazy dog?” or even more fundamentally, “What’s a typewriter?”

Read next: Behind the orange icon: the history of PowerPoint

Going back to Gutenberg

To get the answers to those questions, you need to know a bit more about the history of typing and the history of word processing, including the history of word processing software (and inevitably Microsoft Word). And for all of that, even in this brief history of word processing, it’s helpful to very briefly go back a few centuries to when Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 invented moveable type.

Before Gutenberg, all books were completely handwritten. There was no printing as we know it today. Making a second copy of a book involved hiring a scribe to copy the entire book again by hand. Gutenberg essentially invented the printing industry by replacing handwritten letters with blocks of type. Setting the type was laborious, but once it was done the pages could be reproduced much faster, cheaper and in much larger quantities. A Bible Gutenberg completed in 1455 cost the equivalent of three years’ wages of the average clerk—expensive, but a fraction of the cost of hiring a scribe. Books and pamphlets began to fly off the presses, helping to usher in the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment or really the world as we know it today.

The invention of the typewriter

Still, someone had to write the text in the first place which required putting pen or pencil to paper. It took more than four centuries for that to change, but eventually it did with the development in the late 1800s of the first successful typewriters. Now someone could sit at a typewriter, insert a blank piece of paper and perfectly formed letters would appear on a page as you pressed each key against an inked ribbon inside the typewriter. Typewriters took off in the business world. Instead of handwritten letters or contracts, in which penmanship might lead to errors or legal issues, the cleanly written pages that flew out of typewriters greased the wheels of commerce.

As typewriters became essential in the business world, the demand grew for fast, accurate typists. Training programs similar to the one Bruni attended proliferated. Practicing phrases like “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” were helpful because they were a way to train your hands to correctly hit all the right keys without looking (which would slow you down). Businesses employed thousands of typists.

Being a good typist was about more than just speed

However, to be a good typist, you had to be more than just fast. You had to know…

- How to insert the paper in the typewriter so each page started in the same place.

- How to correctly set the line spacing and the margins—especially the right margin where, when you reached it, a bell would ring warning you to hit the carriage return to move down a line and back to the left margin. (Woe to you if you ignored the bell).

- Also, because business documents followed specific formats—especially business letters—a major part of your training was to learn that template: the placement of the date, your contact information, the recipient’s information, the salutation, the body of the letter, the closing, etc. The worst thing you could do was get the formatting wrong and go back and retype everything.

Typewriters had no memory capabilities, making retyping documents a fact of life. But that began to change in the 1960s with typewriters like the hugely popular IBM Selectric series that essentially launched the era of word processing. These new memory typewriters could store information on magnetic tapes and later cards. When a mistake was made, the typist would simply backspace the typewriter and retype the correct text over the original error. The typewriter could remember the correct version so when the typist would insert a new blank sheet, the typewriter would automatically print out a flawless version of the desired text.

In the 1970s, the invention of larger storage devices (the first floppy disks) and cheaper computer memory led to word processing solutions capable of storing and managing whole documents. That was followed by the addition of cathode ray tube (CRT) screens and computerized printers. Now you could easily view the entire page as you were typing, go back and forth to make edits and instantly print out the results. The modern era of word processing took off.

At first, there was a boom in dedicated word processors, which are essentially computers with proprietary software whose sole function was to churn out typed documents. Companies who made them, such as Vydec and Wang Laboratories, became hugely successful. Individuals still used typewriters, but dedicated word processors took over for large offices and large-scale document production.

The PC revolution

Then came the PC revolution starting with Apple in 1977 and then the IBM PC in 1981. Word processing quickly became one of the most popular applications for these new devices with programs such as WordStar, WordPerfect, MultiMate and Microsoft Word in hot demand (the first version of Microsoft Word appeared on its own in 1983 and later became part of Microsoft Word Office). These programs were not cheap—sometimes $500 and up. There were endless debates over which was the best word processor, but each one made it possible to duplicate many (if not all) of the functions of a dedicated word processor.

Just as Gutenberg revolutionized printing, and the typewriter revolutionized the production of business documents, the PC revolutionized word processing. Now for the price of the software and a thousand dollars plus for the PC, you could avoid spending tens of thousands of dollars on a dedicated word processing solution. The market for dedicated word processors plummeted and the history of the word processor as it had been known was essentially over. PCs began to replace typewriters and word processors in offices throughout the world.

For your average everyday typist, word processing on a PC was infinitely easier. No longer did you have to manually insert a carriage return at the end of a line as the software automatically moved on. Misspell a word? Use find and replace to make the correction. Move paragraphs around with cut and paste.

The addition of spell check and in the early 1990s, autocorrect, made it even easier to churn out documents with no mistakes. Yes, if you wanted to be really speedy, you still needed to master “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.” But now it wasn’t absolutely necessary.

What’s been lost in the history of word processing

Still, in the evolution from typewriting to word processing (and now in the era of the cloud-based online word processor), something has been lost. And it’s not insignificant.

Typewriters were so limited in their formatting capabilities that, everyone learned how to format them the same way. So, inevitably, one business letter looked very much like any other business letter.

Today, just the opposite is the case. With a program like Word, you can create any look you want. That’s, of course, good and bad—and it can be really bad if you care about the image and the brand you are conveying with your business documents.

In many businesses today, failure to follow basic formatting and templating leads to what we at Templafy call “document anarchy”: business documents are produced using different fonts, different logos, different colors. The visual clues that help tell the recipient who the document is from and what it’s about—clues that are essential to fast, accurate communication—get lost entirely. That’s where Templafy comes in.

Templafy improves word processing for enterprises

If you want to save users time, help protect brand image, make compliance easier, and much more; Templafy provides a way for large organizations to centrally manage both the appearance and the content of the thousands of business documents that get generated each day.

Templafy enables an organization to maintain a central, cloud-based library of up-to-date digital assets—such as document templates, logos, slides, photographs, illustrations, and text elements—and then simplifies and personalizes their distribution across your organization.

When your employees open Microsoft Word, Outlook or other programs the correct templates are right there for them to use with the fonts and line spacing already set up.

When revisions are needed to the format, the logo or the disclaimer text, Templafy provides a single place to make the changes and roll them out across your entire organization. For documents like offer letters, contracts, budgets, sales proposals and more, Templafy ensures that the correct templates, graphics, and text elements are readily available to use.

Templafy also streamlines the process of creating new documents, providing prompts and options to guide users through the setup of any document with easy access to centrally managed text elements, slides, charts, tables, etc. Prefigured design solutions guide users to create professional-looking work. Your users still use Word to write the document, but Templafy assists them in creating documents that follow the latest company brand and legal standards.

We don’t train typists any more, the way Frank Bruni was trained when he was a teenager. We aren’t going back to the days of the typewriter when every business letter everywhere looked the same.

Whether you think the loss of that kind of control is good or bad, one thing is for certain: it’s not coming back.

But if you care about the image you convey with your business documents—and you also want to streamline their production and ensure they are legally compliant—the templating capabilities provided by Templafy offer a great solution.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

WordPerfect, a word processor first released for minicomputers in 1979 and later ported to microcomputers, running on Windows XP

A word processor (WP)[1][2] is a device or computer program that provides for input, editing, formatting, and output of text, often with some additional features.

Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to the function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers.

The functions of a word processor program fall somewhere between those of a simple text editor and a fully functioned desktop publishing program. However, the distinctions between these three have changed over time and were unclear after 2010.[3][4]

Background[edit]

Word processors did not develop out of computer technology. Rather, they evolved from mechanical machines and only later did they merge with the computer field.[5] The history of word processing is the story of the gradual automation of the physical aspects of writing and editing, and then to the refinement of the technology to make it available to corporations and Individuals.

The term word processing appeared in American offices in early 1970s centered on the idea of streamlining the work to typists, but the meaning soon shifted toward the automation of the whole editing cycle.

At first, the designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies with emerging ones to develop stand-alone equipment, creating a new business distinct from the emerging world of the personal computer. The concept of word processing arose from the more general data processing, which since the 1950s had been the application of computers to business administration.[6]

Through history, there have been three types of word processors: mechanical, electronic and software.

Mechanical word processing[edit]

The first word processing device (a «Machine for Transcribing Letters» that appears to have been similar to a typewriter) was patented by Henry Mill for a machine that was capable of «writing so clearly and accurately you could not distinguish it from a printing press».[7] More than a century later, another patent appeared in the name of William Austin Burt for the typographer. In the late 19th century, Christopher Latham Sholes[8] created the first recognizable typewriter although it was a large size, which was described as a «literary piano».[9]

The only «word processing» these mechanical systems could perform was to change where letters appeared on the page, to fill in spaces that were previously left on the page, or to skip over lines. It was not until decades later that the introduction of electricity and electronics into typewriters began to help the writer with the mechanical part. The term “word processing” (translated from the German word Textverarbeitung) itself was created in the 1950s by Ulrich Steinhilper, a German IBM typewriter sales executive. However, it did not make its appearance in 1960s office management or computing literature (an example of grey literature), though many of the ideas, products, and technologies to which it would later be applied were already well known. Nonetheless, by 1971 the term was recognized by the New York Times[10] as a business «buzz word». Word processing paralleled the more general «data processing», or the application of computers to business administration.

Thus by 1972 discussion of word processing was common in publications devoted to business office management and technology, and by the mid-1970s the term would have been familiar to any office manager who consulted business periodicals.

Electromechanical and electronic word processing[edit]

By the late 1960s, IBM had developed the IBM MT/ST (Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter). This was a model of the IBM Selectric typewriter from the earlier part of this decade, but it came built into its own desk, integrated with magnetic tape recording and playback facilities along with controls and a bank of electrical relays. The MT/ST automated word wrap, but it had no screen. This device allowed a user to rewrite text that had been written on another tape, and it also allowed limited collaboration in the sense that a user could send the tape to another person to let them edit the document or make a copy. It was a revolution for the word processing industry. In 1969, the tapes were replaced by magnetic cards. These memory cards were inserted into an extra device that accompanied the MT/ST, able to read and record users’ work.

In the early 1970s, word processing began to slowly shift from glorified typewriters augmented with electronic features to become fully computer-based (although only with single-purpose hardware) with the development of several innovations. Just before the arrival of the personal computer (PC), IBM developed the floppy disk. In the early 1970s, the first word-processing systems appeared which allowed display and editing of documents on CRT screens.

During this era, these early stand-alone word processing systems were designed, built, and marketed by several pioneering companies. Linolex Systems was founded in 1970 by James Lincoln and Robert Oleksiak. Linolex based its technology on microprocessors, floppy drives and software. It was a computer-based system for application in the word processing businesses and it sold systems through its own sales force. With a base of installed systems in over 500 sites, Linolex Systems sold 3 million units in 1975 — a year before the Apple computer was released.[11]

At that time, the Lexitron Corporation also produced a series of dedicated word-processing microcomputers. Lexitron was the first to use a full-sized video display screen (CRT) in its models by 1978. Lexitron also used 51⁄4 inch floppy diskettes, which became the standard in the personal computer field. The program disk was inserted in one drive, and the system booted up. The data diskette was then put in the second drive. The operating system and the word processing program were combined in one file.[12]

Another of the early word processing adopters was Vydec, which created in 1973 the first modern text processor, the «Vydec Word Processing System». It had built-in multiple functions like the ability to share content by diskette and print it.[further explanation needed] The Vydec Word Processing System sold for $12,000 at the time, (about $60,000 adjusted for inflation).[13]

The Redactron Corporation (organized by Evelyn Berezin in 1969) designed and manufactured editing systems, including correcting/editing typewriters, cassette and card units, and eventually a word processor called the Data Secretary. The Burroughs Corporation acquired Redactron in 1976.[14]

A CRT-based system by Wang Laboratories became one of the most popular systems of the 1970s and early 1980s. The Wang system displayed text on a CRT screen, and incorporated virtually every fundamental characteristic of word processors as they are known today. While early computerized word processor system were often expensive and hard to use (that is, like the computer mainframes of the 1960s), the Wang system was a true office machine, affordable to organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily mastered and operated by secretarial staff.

The phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to Wang’s. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (AES Data machines — re-badged), CPT, and NBI. All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, with prices in the $10,000 range. Cheap general-purpose personal computers were still the domain of hobbyists.

Japanese word processor devices[edit]

In Japan, even though typewriters with Japanese writing system had widely been used for businesses and governments, they were limited to specialists who required special skills due to the wide variety of letters, until computer-based devices came onto the market. In 1977, Sharp showcased a prototype of a computer-based word processing dedicated device with Japanese writing system in Business Show in Tokyo.[15][16]

Toshiba released the first Japanese word processor JW-10 in February 1979.[17] The price was 6,300,000 JPY, equivalent to US$45,000. This is selected as one of the milestones of IEEE.[18]

Toshiba Rupo JW-P22(K)(March 1986) and an optional micro floppy disk drive unit JW-F201

The Japanese writing system uses a large number of kanji (logographic Chinese characters) which require 2 bytes to store, so having one key per each symbol is infeasible. Japanese word processing became possible with the development of the Japanese input method (a sequence of keypresses, with visual feedback, which selects a character) — now widely used in personal computers. Oki launched OKI WORD EDITOR-200 in March 1979 with this kana-based keyboard input system. In 1980 several electronics and office equipment brands entered this rapidly growing market with more compact and affordable devices. While the average unit price in 1980 was 2,000,000 JPY (US$14,300), it was dropped to 164,000 JPY (US$1,200) in 1985.[19] Even after personal computers became widely available, Japanese word processors remained popular as they tended to be more portable (an «office computer» was initially too large to carry around), and become necessities in business and academics, even for private individuals in the second half of the 1980s.[20] The phrase «word processor» has been abbreviated as «Wa-pro» or «wapuro» in Japanese.

Word processing software[edit]

The final step in word processing came with the advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s and 1980s and with the subsequent creation of word processing software. Word processing software that would create much more complex and capable output was developed and prices began to fall, making them more accessible to the public. By the late 1970s, computerized word processors were still primarily used by employees composing documents for large and midsized businesses (e.g., law firms and newspapers). Within a few years, the falling prices of PCs made word processing available for the first time to all writers in the convenience of their homes.

The first word processing program for personal computers (microcomputers) was Electric Pencil, from Michael Shrayer Software, which went on sale in December 1976. In 1978 WordStar appeared and because of its many new features soon dominated the market. However, WordStar was written for the early CP/M (Control Program–Micro) operating system, and by the time it was rewritten for the newer MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System), it was obsolete. Suddenly, WordPerfect dominated the word processing programs during the DOS era, while there was a large variety of less successful programs.

Early word processing software was not as intuitive as word processor devices. Most early word processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys such as «copy» or «bold». Moreover, CP/M lacked cursor keys; for example WordStar used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond» for cursor navigation. However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as “killer app” spreadsheet applications, e.g. VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software became serious competition for the dedicated machines and soon dominated the market.

Then in the late 1980s innovations such as the advent of laser printers, a «typographic» approach to word processing (WYSIWYG — What You See Is What You Get), using bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), and graphical user interfaces such as “copy and paste” (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor). These were popularized by MacWrite on the Apple Macintosh in 1983, and Microsoft Word on the IBM PC in 1984. These were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people.

Of particular interest also is the standardization of TrueType fonts used in both Macintosh and Windows PCs. While the publishers of the operating systems provide TrueType typefaces, they are largely gathered from traditional typefaces converted by smaller font publishing houses to replicate standard fonts. Demand for new and interesting fonts, which can be found free of copyright restrictions, or commissioned from font designers, occurred.

The growing popularity of the Windows operating system in the 1990s later took Microsoft Word along with it. Originally called «Microsoft Multi-Tool Word», this program quickly became a synonym for “word processor”.

From early in the 21st century Google Docs popularized the transition to online or offline web browser based word processing, this was enabled by the widespread adoption of suitable internet connectivity in businesses and domestic households and later the popularity of smartphones. Google Docs enabled word processing from within any vendor’s web browser, which could run on any vendor’s operating system on any physical device type including tablets and smartphones, although offline editing is limited to a few Chromium based web browsers. Google Docs also enabled the significant growth of use of information technology such as remote access to files and collaborative real-time editing, both becoming simple to do with little or no need for costly software and specialist IT support.

See also[edit]

- List of word processors

- Formatted text

References[edit]

- ^ Enterprise, I. D. G. (1 January 1981). «Computerworld». IDG Enterprise. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Waterhouse, Shirley A. (1 January 1979). Word processing fundamentals. Canfield Press. ISBN 9780064537223. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Amanda Presley (28 January 2010). «What Distinguishes Desktop Publishing From Word Processing?». Brighthub.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «How to Use Microsoft Word as a Desktop Publishing Tool». PCWorld. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Price, Jonathan, and Urban, Linda Pin. The Definitive Word-Processing Book. New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1984, page xxiii.

- ^ W.A. Kleinschrod, «The ‘Gal Friday’ is a Typing Specialist Now,» Administrative Management vol. 32, no. 6, 1971, pp. 20-27

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. The Tech Ninja. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ See also Samuel W. Soule and Carlos Glidden.

- ^ The Scientific American, The Type Writer, New York (August 10, 1872)

- ^ W.D. Smith, “Lag Persists for Business Equipment,” New York Times, 26 Oct. 1971, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Linolex Systems, Internal Communications & Disclosure in 3M acquisition, The Petritz Collection, 1975.

- ^ «Lexitron VT1200 — RICM». Ricomputermuseum.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (1 June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «Redactron Corporation. @ SNAC». Snaccooperative.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «日本語ワードプロセッサ». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ «【シャープ】 日本語ワープロの試作機». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ 原忠正 (1997). «日本人による日本人のためのワープロ». The Journal of the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan. 117 (3): 175–178. Bibcode:1997JIEEJ.117..175.. doi:10.1541/ieejjournal.117.175.

- ^ «プレスリリース;当社の日本語ワードプロセッサが「IEEEマイルストーン」に認定». 東芝. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^

«【富士通】 OASYS 100G». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05. - ^ 情報処理学会 歴史特別委員会『日本のコンピュータ史』ISBN 4274209334 p135-136

|

Inventors of the Modern Computer WordStar Seymour Rubenstein & Rob Barnaby |

In the early days, the size of the market was more promise than reality…

WordStar was a tremendous learning experience. I didn’t know all that much

about the world of big business. I thought I knew it» — Seymour Rubenstein

«I am happy to greet the geniuses who made me a born-again writer,

having announced my retirement in 1978, I now have six books in the works

and two [probables], all through WordStar.» Arthur C. Clarke on meeting

Rubenstein and Barnaby

Released in 1979 by Micropro International Inc., WordStar was the first

commercially successful word processing software program produced for microcomputers

and the best selling software program of the early eighties. Word processing

can be defined as the manipulation of computer generated text data including

creating, editing, storing, retrieving and printing a document.

The first computer word processors were line editors, software-writing

aids that allowed a programmer to make changes in a line of program code.

Altair

programmer Michael Shrayer decided to write the manuals for computer programs

on the same computers the programs ran on. He wrote the somewhat popular

and the actual first PC word processing program, the Electric Pencil in

1976. Some other early word processor programs were Apple Write I, Samna

III, Word, WordPerfect and Scripsit.

Seymour Rubenstein first started developing an early version of a word

processor for the IMSAI

8080 computer when he was director of marketing for IMSAI. He left

to start MicroPro International Inc. in 1978 with only $8,500 in cash.

Software programmer Rob Barnaby was convinced to leave IMSAI and tag along

with Rubenstein and MicroPro. Barnaby wrote the 1979 version of WordStar.

Jim Fox, Barnaby’s assistant, ported (re-wrote for a different operating

system) WordStar from the CP/M operating system to MS/PC DOS.

Note: The CP/M operating system was developed by Gary Kildall, founder

of Digital Research, copywritten in 1976 and released in 1977. MS/PC DOS

is the famous operating system introduced by MicroSoft and Bill Gates in

1981.

Related

Links

artwork ©MaryBellis

A word processor is an electronic device or computer software application, that performs the task of composition, editing, formatting, and sometimes printing of documents.

The First Word Processor

Released in 1979 by Micropro International, WordStar was the first commercially successful word processing software program produced for microcomputers and the best selling software program of the early eighties.

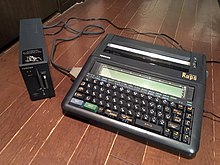

Word processor application that had a dominant market share during the early- to mid-1980s. Formerly published by MicroPro International, it was originally written for the CP/M operating system but later ported to DOS. Although Seymour I. Rubinstein was the principal owner of the company, Rob Barnaby was the sole author of the early versions of the program. Starting with WordStar 4.0, the program was built on new code written principally by Peter Mierau.

WordStar was deliberately written to make as few assumptions about the underlying system as possible, allowing it to be easily ported across the many platforms that proliferated in the early 1980s. As all of these versions had relatively similar commands and controls, users could move between platforms with equal ease. Already popular, its inclusion with the Osborne 1 computer made the program become the de facto standard for much of the word processing market.

As the computer market quickly became dominated by the IBM PC, this same portable design made it difficult for the program to add new features and affected its performance. In spite of its great popularity in the early 1980s, these problems allowed WordPerfect to take WordStar’s place as the most widely used word processor from 1985 onwards.