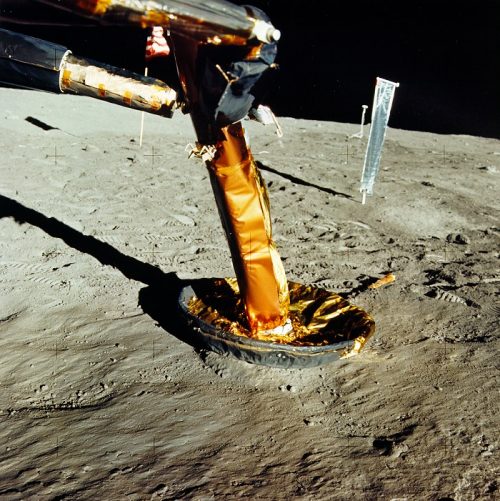

(Image credit: NASA)

Were Neil Armstrong’s historic first words spoken on the moon pre-scripted or, as the late astronaut long held, ad-libbed on the spot?

Armstrong, on becoming the first person to set foot onto another planetary body on July 20, 1969, radioed back to Earth, «That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind.» His quote instantly became a part of history. (The «a» wasn’t audible in the broadcast but the astronaut said — and a 2006 audio analysis supported — that he did indeed speak the word.)

Since returning to Earth four decades ago and up until his death last year, Armstrong maintained that he did not give any thought to what he would say while on the moon until after he safely landed the Apollo 11 lunar module «Eagle» at Tranquility Base.

But a new interview with his brother suggests Armstrong’s «small step» quote was not a «giant leap» at improvisation. [Neil Armstrong Buried at Sea (NASA Photos)]

«He slipped me a piece of paper and said ‘read that,'» said Dean Armstrong, Neil’s younger brother, during a new BBC documentary on the first moonwalker’s life that first aired on Sunday (Dec. 30). «On that piece of paper there was ‘That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.'»

Neil then asked his brother what he thought about the quote. «Fabulous,» Dean recalled as saying, to which his brother replied, ‘I thought you might like that, but I wanted you to read it.'»

According to Dean, that conversation took place months before his brother launched to the moon. But not everyone accepts his account as being accurate.

«As much as I respect Dean Armstrong, I do not believe his recollection of this is correct,» James R. Hansen, Neil Armstrong‘s authorized biographer, wrote on Facebook.

Neil Armstrong ‘never told lies’

«I spent a great deal of time talking about this issue during my near-60 hours of interviews for my biography of him, ‘First Man,'» Hansen said, describing his research into the origin of the «one small step» quote. «Neil was the sort of man who never told lies. He might avoid or evade certain questions and answers, but he never outright lied.»

In «First Man: A Life of Neil A. Armstrong» (2005, Simon and Schuster), Armstrong told Hansen that he came up with the quote as he completed the post-landing checklist and prepared for humanity’s first moonwalk.

«Once on the surface and realizing that the moment was at hand, fortunately I had some hours to think about it after getting there,» Armstrong said.

«It just sort of evolved during the period that I was doing the procedures of the practice takeoff and the EVA prep and all the other activities that were on our flight schedule at the time,» Armstrong told Hansen. «I didn’t think it was particularly important, but other people obviously did.» [Photos: Neil Armstrong Remembered]

Armstrong recounted the same course of events in other interviews and during public lectures held before and after the research for his biography. To Hansen, the astronaut’s own words leave no room for debate.

«He told me quite specifically and emphatically that he did not pre-plan what he would say and came up with the phrase only after the landing,» Hansen wrote on Facebook. «That was what he told me clearly and on tape.»

As further evidence, «First Man» also quotes Armstrong’s first wife Janet as having had «absolutely no idea what her husband would say when he stepped onto the moon.»

Nor, apparently, did his crewmates.

«On the way to the moon, Mike [Collins] and I had asked Neil what he was going to say when he stepped out on the moon,» astronaut Buzz Aldrin told Hansen. «He had replied that he was still thinking it over.»

Hansen interviewed Dean Armstrong for «First Man» as well, but Neil’s brother did not say anything then about his knowing the quote ahead of time.

«I think we should accept [what Neil said] as true and not a story his brother never has told for 43 years and did not mention to me during my long interview for the book,» said Hansen. «Why wouldn’t he have told that story for his brother’s authorized biography?»

‘The Hobbit’ and other hypotheses

Dean Armstrong is not the first to suggest his brother gave more than a passing thought to his first words on the moon.

As Hansen recounts in «First Man,» some have attributed the idea for the quote to the moonwalker’s apparent affinity for J.R.R. Tolkien’s works of fiction. After leaving NASA in 1971, Armstrong named his farm for a valley described in «The Lord of the Rings» and chose an email address with a Tolkien theme.

According to the theory, Armstrong’s historic quote can be traced to «The Hobbit,» to a scene where the protagonist Bilbo Baggins jumps over the villainous Gollum in a leap that Tolkien described as «not a great leap for a man, but a leap in the dark.»

«Regrettably for Tolkien fans,» explained Hansen in «First Man,» «Armstrong’s reading of the classic books could not have influenced what he said when he stepped on the lunar surface in 1969. Indeed, he did come to read ‘The Hobbit’ and ‘The Lord of the Rings,’ but not until well after Apollo 11.»

Another hypothesis suggests Armstrong took inspiration from a memo circulating around NASA. Written by Willis Shapely, an associate deputy administrator at the space agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., the memo suggested that the lunar landing should be symbolized «as an historic step forward for all mankind.»

The problem, Hansen writes, is Armstrong had no memory of ever seeing the memo, let alone it «planting the seed» for his historic first words.

Follow collectSPACE on Facebook and Twitter @collectSPACE and editor Robert Pearlman @robertpearlman. Copyright 2012 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, an online publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of «Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018. He previously developed online content for the National Space Society and Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, helped establish the space tourism company Space Adventures and currently serves on the History Committee of the American Astronautical Society, the advisory committee for The Mars Generation and leadership board of For All Moonkind. In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History.

Most Popular

On July 20, 1969, an estimated 650 million people watched in suspense as Neil Armstrong descended a ladder towards the surface of the Moon.

As he took his first steps, he uttered words that would be written into history books for generations to come: “That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.”

Or at least that’s how the media reported his words.

But Armstrong insisted that he actually said, “That’s one small step for a man.” In fact, in the official transcript of the Moon landing mission, NASA transcribes the quote as “that’s one small step for (a) man.”

As a linguist, I’m fascinated by mistakes between what people say and what people hear.

In fact, I recently conducted a study on ambiguous speech, using Armstrong’s famous quote to try to figure out why and how we successfully understand speech most of the time, but also make the occasional mistake.

Our extraordinary speech-processing abilities

Despite confusion over Armstrong’s words, speakers and listeners have a remarkable ability to agree on what is said and what is heard.

When we talk, we formulate a thought, retrieve words from memory and move our mouths to produce sound. We do this quickly, producing, in English, around five syllables every second.

The process for listeners is equally complex and speedy. We hear sounds, which we separate into speech and non-speech information, combine the speech sounds into words, and determine the meanings of these words. Again, this happens nearly instantaneously, and errors rarely occur.

These processes are even more extraordinary when you think more closely about the properties of speech. Unlike writing, speech doesn’t have spaces between words. When people speak, there are typically very few pauses within a sentence.

Yet listeners have little trouble determining word boundaries in real time. This is because there are little cues – like pitch and rhythm – that indicate when one word stops and the next begins.

But problems in speech perception can arise when those kinds of cues are missing, especially when pitch and rhythm are used for non-linguistic purposes, like in music. This is one reason why misheard song lyrics – called “mondegreens” – are common. When singing or rapping, a lot of the speech cues we usually use are shifted to accommodate the song’s beat, which can end up jamming our default perception process.

But it’s not just lyrics that are misheard. This can happen in everyday speech, and some have wondered if this is what happened in the case of Neil Armstrong.

Studying Armstrong’s mixed signals

Over the years, researchers have tried to comb the audio files of Armstrong’s famous words, with mixed results. Some have suggested that Armstrong definitely produced the infamous “a,” while others maintain that it’s unlikely or too difficult to tell. But the original sound file was recorded 50 years ago, and the quality is pretty poor.

So can we ever really know whether Neil Armstrong uttered that little “a”?

Perhaps not. But in a recent study, my colleagues and I tried to get to the bottom of this.

First, we explored how similar the speech signals are when a speaker intends to say “for” or “for a.” That is, could a production of “for” be consistent with the sound waves, or acoustics, of “for a,” and vice-versa?

So we examined nearly 200 productions of “for” and 200 productions of “for a.” We found that the acoustics of the productions of each of these tokens were nearly identical. In other words, the sound waves produced by “He bought it for a school” and “He bought one for school” are strikingly similar.

But this doesn’t tell us what Armstrong actually said on that July day in 1969. So we wanted to see if listeners sometimes miss little words like “a” in contexts like Armstrong’s phrase.

We wondered whether “a” was always perceived by listeners, even when it was clearly produced. And we found that, in several studies, listeners often misheard short words, like “a.” This is especially true when the speaking rate was as slow as Armstrong’s.

In addition, we were able to manipulate whether or not people heard these short words just by altering the rate of speech. So perhaps this was a perfect storm of conditions for listeners to misperceive the intended meaning of this famous quote.

The case of the missing “a” is one example of the challenges in producing and understanding speech. Nonetheless, we typically perceive and produce speech quickly, easily and without conscious effort.

A better understanding of this process can be especially useful when trying to help people with speech or hearing impairments. And it allows researchers to better understand how these skills are learned by adults trying to acquire a new language, which can, in turn, help language learners develop more efficient strategies.

Fifty years ago, humanity was changed when Neil Armstrong took those first steps on the Moon. But he probably didn’t realize that his famous first words could also help us better understand how humans communicate.

—By Melissa Michaud Baese-Berk, associate professor, Department of Linguistics

The Conversation

What was the first words said on the moon and who said them?

As you can guess, it wasn’t Neil Armstrong’s One Small Step. It was, according to a lot of sources, his colleague, Buzz Aldrin.

The quote mentioned earlier was uttered at 102:45:40 MET [ Mission Elapsed Time ] 20:17:40 GMT on July 20, 1969. That was when the first piece of the lander touched the surface. It seems that the first words from the actual surface was Neil saying Shutdown. instructing Aldrin to turn off the descent engine. That was performed a second after that call at 102:45:44 MET. four seconds after Aldrin should have shut down the engine as the last few feet should have been un-powered. Neil had decided to do the full descent under power as a safety option so to protect the vehicle as much as possible.

The most famous conversation after the landing is when CAPCOM, Charlie Duke, gets himself tongue-tied due to the change of call sign. When the landing occurred, convention stated that the lander Eagle changed from the call sign Eagle to Tranquility Base. That to confirm that the landing had been successful.

102:45:58 Armstong: Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

102:56:06 Duke: (Momentarily tongue-tied) Roger, Twan…(correcting himself) Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

102:46:16 Aldrin: Thank you.

We’re not 100% sure that it was Aldrin who thanked CAPCOM. It seems a very Buzz thing to do ‘tho!

It was quite a fraught landing with the computer throwing up strange errors as well as fuel issues that were, just about, sorted out. When Buzz said Contact Light they had 17 seconds of fuel left before they had to abort the landing. A little less time than it takes an Olympic athlete to cover 200 meters!

The errors mentioned above were 1201/12012 errors. In layman terms it meant that the computer was getting too much information and didn’t have the capacity to deal with it all. It was doing its job and was ignoring jobs that it knew weren’t important and carrying on. It was discovered in the post-mission debriefings that the radar was running in the wrong mode. This was altered in later missions so to remove that possible error occurring again. An amazing computer that worked flawlessly even if the mission plan was flawed.

We knew what he meant.

Published Jan 26, 2003

Claim:

Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong flubbed his historic ‘one small step’ remark as he became the first man to set foot on the surface of the moon.

Rating:

English has no handy term for what the French call it esprit de l’escalier, and the Germans know as treppenwitz: the «wit of the staircase,» those clever remarks or cutting rejoinders that only come to mind once it’s too late for us to deliver them — literally, as we’re headed down the stairs and out of the house. English also lacks an expression to describe the antithesis of treppenwitz, those occasions when one has a perfect remark carefully prepared in advance but fails to deliver it properly. If English did have such an expression, we could apply it to the words of the first man on the moon, Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong, who had the misfortune of misspeaking his scripted line during one of the most widely-viewed live broadcasts in television history.

What Neil Armstrong meant to say as he descended from the ladder of Apollo 11’s Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) and stepped onto the lunar surface, thus becoming the first person ever to set foot on the moon, was «That’s one small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind.»

Unfortunately, however, Armstrong flubbed his line in the excitement of the moment, omitting one small word («a») and delivering the line as «That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.» The missing article made a world of difference in literal meaning, though — instead of a statement linking the small action of one man with a monumental achievement for (and by) all of humanity, Armstrong instead uttered a somewhat contradictory phrase that equated a small step by the human race with a momentous achievement by humankind («man» and «mankind» having the same approximate meaning in English). Nonetheless, since the quote as actually spoken by Armstrong still sounded good, and most everyone understood the meaning he intended to convey, his words were widely repeated that day and have since joined the pantheon of the most well-known quotes in the English language.

After the Apollo 11 astronauts returned to Earth, Armstrong corrected his mistake (stating that he had been «misquoted»), and NASA obligingly provided the cover story that «static» had obscured the missing word:

Neil A. Armstrong, the Apollo 11 commander, had said that one small word was omitted in the official version of the historic utterance he made he stepped on the moon 11 days ago.When Mr. Armstrong saw the quotation — «That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind» — in the mission transcript after his return to earth, he said he was misquoted, it was reported yesterday.

There should have been the article «a» before «man,» the astronaut said.

The «a» apparently went unheard and unrecorded in the transmission because of static, a spokesman for the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston said today in a telephone interview.

Whatever the reason, inserting the omitted article makes a slight but significant change in the meaning of Mr. Armstrong’s words, which should read: «That’s one small step for a man, one giant step (sic) for ma[n]kind.»1

Press reporters, however, were more skeptical about what Armstrong had actually said:

On July 20, 1969, Joel Shurkin was chief of the Reuters news agency’s team at Mission Control in Houston, Tex. «When Armstrong landed, we all listened to the raw air-to-ground and when he said the part about the ‘small step’ it was fuzzy — this was the unenhanced version, live — and it was not clear if he said ‘a man’ or ‘man,’ » he says, sharing his experience publicly for the first time.Nor were the words perfectly clear for the more than a billion people listening and watching the televised broadcast as the lunar module Eagle touched down, and Mr. Armstrong and fellow astronaut Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin stepped out into what Mr. Aldrin described as «magnificent desolation.»

Months after the lunar landing, in the book First on the Moon, which was billed as an «exclusive and official account . . . as seen by the men who experienced it,» Mr. Armstrong recalls his famous words as: «That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.»

He notes that Mission Control missed the «a» in the first phrase, writing that «tape recorders are fallible.»

However, for the dozens of journalists in Houston, the uncertainty left them feeling their own version of space sickness.

«It was one of the most important quotes in history and it wouldn’t do to get it wrong and we didn’t have time to pursue the matter,» Mr. Shurkin wrote in a posting to a list-serv of the U.S. National Association of Science Writers.

«Worse, it wouldn’t do to have me say one thing, and the Associated Press another, or to be contradicted by The New York Times.»

The journalists from the major wire services and newspapers gave up watching the live broadcast and huddled in the press room debating what to do. They decided that they would agree on what they heard and all file the same quote.

«We concluded that he did not say ‘a man’ and that’s the way it went out to the world,» says Mr. Shurkin, now a writer in Baltimore.2

The New York Times clearly didn’t buy the «static» explanation (hence the «Whatever the reason …» introductory phrase in the final sentence of their article), and little detective work is necessary to reveal it as a face-saving fabrication: NASA’s own recording of Armstrong’s transmission from the lunar surface reveals that his words are clearly audible over the background static; that the word «man» follows immediately on the heels of «for,» with no gap between them into which Armstrong could conceivably have inserted the word «a»; and that Armstrong pauses noticeably after the word «man,» as he realizes he’s flubbed his line and hesitates momentarily before completing it.

In the years since that historic Apollo 11 mission, astronaut Armstrong has apparently reconciled himself to admitting that he did indeed misspeak his key line:

Later, a representative for the Grumman company (it had built the Eagle, essentially a high-tech aluminum can) presented Mr. Armstrong with a silver plaque bearing his 11-word — now immortalized — sentence, «That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.»Mr. Armstrong insisted that they had left out an «a». Sure, he had been awake for 24 hours before his epoch-marking pronouncement, battling lunar stage fright in front of the world’s largest audience ever, and was mulling over the fact that while putting on his bulky space suit he had broken the circuit breaker for the switch to start the Eagle’s engine for ascent.

But he knew what he said. «There must be an ‘a’, » Mr. Armstrong says of the event in the 1986 book Chariots for Apollo. «I rehearsed it that way. I meant it that way. And I’m sure I said it that way.»

Then the Grumman representative, Tommy Attridge, put on a commemorative 45-rpm recording of the flight. No matter what speed they played it at, there was no «a».

According to the authors, Mr. Armstrong sighed, «Damn, I really did it. I blew the first words on the moon, didn’t I?»2

Happily for Neil Armstrong, the tremendous scientific and cultural importance of his achievement dwarfed his minor verbal slip-up, and despite his failure to deliver his line as planned, it remains one of the world’s most famous sentences.

In September 2006, Peter Ford of Control Bionics announced he had analyzed the historic Apollo 11 recordings and claimed to have found a «signature for the missing ‘a,» (supposedly spoken by Armstrong «10 times too quickly to be heard») but the results have not been validated by other audio analysts and have been criticized as simply interpreting ambiguous data to match a predetermined conclusion. As Rick Houston wrote in Footprints in the Dust, a history of the Apollo program:

Note should be made of the debate that has existed almost from the time Armstrong uttered the famous saying. Did he actually say «One small step for a man,» with the indefinite article a somehow lost in transmission? No, he did not, and to imply otherwise is revisionist history. Granted, it is possible, if not probable, that he intended to say «a man.» From the tone and inflection of his voice it seems for all the world that Armstrong caught the mistake immediately. Following «That’s one small step for man,» he added another one, stopped again, then finished the statement with «giant leap for mankind.» There’s nothing lost in transmission, nothing at all, no matter what any super-scientific studies to the contrary might suggest.

Additional information:

Apollo 11 transcript

Sources

2. Berkowitz, Jacob. “Moon Landing: One Small Slipup for (a) Man.”

[Toronto] Globe and Mail. 17 July 2004 (p. F9).

Boller Jr., Paul F. and John George. They Never Said It.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-19-506469-0 (pp. 4-5).

Burgess, Colin. Footprints in the Dust: The Epic Voyages of Apollo, 1969-1975.

Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8032-2665-4 (pp. 13-14).

Carreau, Mark. “One Small Step for Clarity.”

Houston Chronicle. 3 October 2006.

Keyes, Ralph. Nice Guys Finish Seventh.

New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 0-06-270020-0

(pp. 15-16).

Poundstone, William. Big Secrets.

New York: Quill, 1983. ISBN 0-688-04830-7 (pp. 183-184).

1. The New York Times. “Armstrong Adds an ‘A’ to Historical Quotation.”

31 July 1969 (p. 20).

By David Mikkelson

David Mikkelson founded the site now known as snopes.com back in 1994.

Article Tags

Become

a Member

Your membership is the foundation of our sustainability and resilience.

Perks

Ad-Free Browsing on Snopes.com

Members-Only Newsletter

Cancel Anytime

On July 20, 1969, an estimated 650 million people watched in suspense as Neil Armstrong descended a ladder towards the surface of the moon.

As he took his first steps, he uttered words that would be written into history books for generations to come: “That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.”

Or, at least, that’s how the media reported his words.

But Armstrong insisted that he actually said, “That’s one small step for a man.” In fact, in the official transcript of the moon landing mission, NASA transcribes the quote as “that’s one small step for (a) man.”

In fact, I recently conducted a study on ambiguous speech, using Armstrong’s famous quote to try to figure out why and how we successfully understand speech most of the time, but also make the occasional mistake.

See also: Apollo 11 Was Seconds Away From Having to Abort the Moon Landing

Our Extraordinary Speech-Processing Abilities

Despite confusion over Armstrong’s words, speakers and listeners have a remarkable ability to agree on what is said and what is heard.

When we talk, we formulate a thought, retrieve words from memory, and move our mouths to produce sound. We do this quickly, producing, in English, around five syllables every second.

The process for listeners is equally complex and speedy. We hear sounds, which we separate into speech and non-speech information, combine the speech sounds into words, and determine the meanings of these words. Again, this happens nearly instantaneously, and errors rarely occur.

These processes are even more extraordinary when you think more closely about the properties of speech. Unlike writing, speech doesn’t have spaces between words. When people speak, there are typically very few pauses within a sentence.

Yet listeners have little trouble determining word boundaries in real-time. This is because there are little cues — like pitch and rhythm — that indicate when one word stops and the next begins.

But problems in speech perception can arise when those kinds of cues are missing, especially when pitch and rhythm are used for non-linguistic purposes, like in music. This is one reason why misheard song lyrics —called “mondegreens” — are common. When singing or rapping, a lot of the speech cues we usually use are shifted to accommodate the song’s beat, which can end up jamming our default perception process.

It’s not just lyrics that are misheard. It can happen in everyday speech, and some have wondered if this is what happened in the case of Neil Armstrong.

Studying Armstrong’s Mixed Signals

Over the years, researchers have tried to comb the audio files of Armstrong’s famous words with mixed results. Some have suggested that Armstrong definitely produced the infamous “a,” while others maintain that it’s unlikely or too difficult to tell. But the original sound file was recorded 50 years ago, and the quality is pretty poor.

So can we ever really know whether Neil Armstrong uttered that little “a”?

Perhaps not. But in a recent study, my colleagues and I tried to get to the bottom of this.

First, we explored how similar the speech signals are when a speaker intends to say “for” or “for a.” That is, could a production of “for” be consistent with the sound waves, or acoustics, of “for a,” and vice-versa?

So we examined nearly 200 productions of “for” and 200 productions of “for a.” We found that the acoustics of the productions of each of these tokens were nearly identical. In other words, the sound waves produced by “he bought it for a school” and “he bought one for school” are strikingly similar.

But this doesn’t tell us what Armstrong actually said on that July day in 1969. So we wanted to see if listeners sometimes miss little words like “a” in contexts like Armstrong’s phrase.

We wondered whether “a” was always perceived by listeners, even when it was clearly produced. And we found that, in several studies, listeners often misheard short words, like “a.” This is especially true when the speaking rate was as slow as Armstrong’s.

In addition, we were able to manipulate whether or not people heard these short words just by altering the rate of speech. So perhaps this was a perfect storm of conditions for listeners to misperceive the intended meaning of this famous quote.

The case of the missing “a” is one example of the challenges in producing and understanding speech. Nonetheless, we typically perceive and produce speech quickly, easily, and without conscious effort.

A better understanding of this process can be especially useful when trying to help people with speech or hearing impairments. And it allows researchers to better understand how these skills are learned by adults trying to acquire a new language, which can, in turn, help language learners develop more efficient strategies.

Fifty years ago, humanity was changed when Neil Armstrong took those first steps on the moon. But he probably didn’t realize that his famous first words could also help us better understand how humans communicate.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Melissa Michaud Baese-Berk. Read the original article here.