Key moments in Romeo and Juliet and some significant facts about the play and its characters.

Every director will choose their own key moments in Romeo and Juliet depending on how they are interpreting the play. Here we’ve listed some important moments in the order in which they appear in the play.

We refer to the RSC Shakespeare edition of the plays. Act and scene numbers vary with different editions.

The scene is set (Act 1 Scene 1)

Montague and Capulet servants clash in the street, the Prince threatens dire punishment if another such brawl should take place, and Romeo tells his friend, Benvolio, of his obsession with Rosaline.

The lovers meet for the first time (Act 1 Scene 4)

Romeo is persuaded to attend a masked party at the Capulet household. Not knowing who she is, he falls in love with Juliet the moment he sees her, and she, equally ignorant that he is a Montague, falls just as instantly for him (this is Act 1, Scene 5 in many editions).

Romeo risks death to meet Juliet again (Act 2 Scene 1)

When everyone has left the party, Romeo creeps into the Capulet garden and sees Juliet on her balcony. They reveal their mutual love and Romeo leaves, promising to arrange a secret marriage and let Juliet’s messenger, her old Nurse, have the details the following morning. This famous scene, known as the Balcony Scene, is numbered Act 2, Scene 2 in many editions.

The wedding is held in secret (Act 2 Scene 5)

Juliet tells her parents she is going to make her confession to Friar Laurence, meets Romeo there and, despite some personal misgivings, the friar marries them immediately.

Romeo angrily kills Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt (Act 3 Scene 1)

Romeo meets Tybalt in the street, and is challenged by him to a duel. Romeo refuses to fight and his friend Mercutio is so disgusted by this ‘cowardice’ that the takes up the challenge instead. As Romeo tries to break up the fight, Tybalt kills Mercutio and, enraged, Romeo then kills Tybalt. The Prince arrives and, on hearing the full story, banishes Romeo rather than have him executed.

The unhappy couple are parted (Act 3 Scene 5)

Arranged by the Friar and the Nurse, Romeo and Juliet have spent their wedding night together. They are immediately parted though, as Romeo must leave for banishment in Mantua or die if he is found in Verona. Believing her grief to be for the death of her cousin, Juliet’s father tries to cheer Juliet by arranging her immediate marriage to Paris. He threatens to disown her when she asks for the marriage to be at least postponed, and she runs to the Friar for advice and help.

The Friar suggests a dangerous solution (Act 4 Scene 1)

Juliet arrives at the Friar’s to be met by Paris, who is busy discussing their wedding plans. She is so desperate that she threatens suicide, and the Friar instead suggests that she takes a potion that will make her appear to be dead. He promises to send a message to Romeo, asking him to return secretly and be with Juliet when she wakes, once her ‘body’ has been taken to the family crypt.

Juliet is found ‘dead’ (Act 4 Scene 4)

The Nurse discovers Juliet ‘s ‘body’ dead’ when she goes to wake her for her marriage Paris. Friar Laurence is called, counsels the family to accept their grief, and arranges for Juliet to be ‘buried’ immediately.

Romeo learns of the tragedy and plans suicide (Act 5 Scene 1)

Romeo’s servant, Balthasar, reaches Mantua before the Friar’s messenger and tells Romeo that Juliet is dead. Romeo buys poison and leaves for Verona, planning to die alongside Juliet’s body.

The tragic conclusion (Act 5 Scene 3)

Trying to break into the Capulet crypt, Romeo is disturbed by Paris and they fight. Romeo kills Paris and reaches Juliet’s body. He drinks the poison, kisses his wife for the last time, and dies. Having learned that Romeo never received his message, the Friar comes to the crypt to be with Juliet when she wakes. He finds Paris’s body and reaches Juliet just as she revives. He cannot persuade her to leave her dead husband, and runs away in fear. Juliet realises what has happened, takes Romeo’s knife and stabs herself to death with it. The watchmen discover the gruesome sight and call the Prince, to whom the Friar confesses everything. Having heard the full story, the Montagues and Capulets are reconciled. Peace has been achieved, but the price has been the lives of two innocent young lovers.

Facts about Romeo and Juliet

- The first words of Romeo and Juliet are in the form of a sonnet. This prologue reveals the ending to the audience before the play has properly begun.

- The play can be considered as a companion piece to that staged by the Mechanicals at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Here the young lovers take their lives in earnest, but in A Midsummer Night’s Dream the story of Pyramus and Thisbe becomes comic entertainment for three sets of newly-weds.

- 90% of the play is in verse, with only 10% in prose. It contains some of Shakespeare’s most beautiful poetry, including the sonnet Romeo and Juliet share when they first meet.

- Although a story of passionate first love, the play is also full of puns. Even in death, Mercutio manages to joke: ‘ask for me tomorrow and you will find me a grave man’.

- Juliet is only 13 at the time she meets and marries Romeo, but we never learn his exact age.

- Like King Lear, the play was adapted by Nahum Tate, changing the story to give it a happy ending.

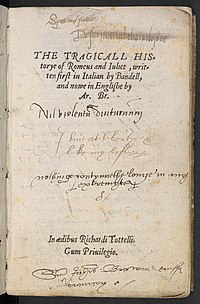

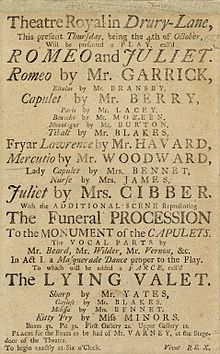

- In 1748, the famous David Garrick staged a version which did not include any mention of Romeo’s love for Rosaline, because Garrick felt this made the tragic hero appear too fickle.

- In March 1662, Mary Saunderson became almost certainly the first woman to play Juliet on the professional stage. Until the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, women were not allowed to perform in public.

- Romeo and Juliet, alongside Hamlet, is probably Shakespeare’s most performed play and has also been adapted in many forms.

- The musical West Side Story is probably the most famous adaptation, while Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet brought Shakespeare’s play to the MTV generation.

Enter Romeo, Mercutio, Benuolio, with fiue or sixe

other Maskers, Torch-bearers.

Rom.

What shall this speeh be spoke for our excuse?

Or shall we on without Apologie?

Ben.

The date is out of such prolixitie,

Weele haue no Cupid, hood winkt with a skarfe,

Bearing a Tartars painted Bow of lath,

Skaring the Ladies like a Crow-keeper.

But let them measure vs by what they will,

Weele measure them with a Measure, and be gone.

Rom.

Giue me a Torch, I am not for this ambling.

Being but heauy I will beare the light.

Mer.

Nay gentle Romeo, we must haue you dance.

Rom.

Not I beleeue me, you haue dancing shooes

With nimble soles, I haue a soale of Lead

So stakes me to the ground, I cannot moue.

Mer.

You are a Louer, borrow Cupids wings,

And soare with them aboue a common bound.

Rom.

I am too sore enpearced with his shaft,

To soare with his light feathers, and to bound:

I cannot bound a pitch aboue dull woe,

Vnder loues heauy burthen doe I sinke.

Hora.

And to sinke in it should you burthen loue,

Too great oppression for a tender thing.

Rom.

Is loue a tender thing? it is too rough,

Too rude, too boysterous, and it pricks like thorne.

Mer.

If loue be rough with you, be rough with loue,

Pricke loue for pricking, and you beat loue downe,

Giue me a Case to put my visage in,

A Visor for a Visor, what care I

What curious eye doth quote deformities:

Here are the Beetle-browes shall blush for me.

Ben.

Come knocke and enter, and no sooner in,

But euery man betake him to his legs.

Rom.

A Torch for me, let wantons light of heart

Tickle the sencelesse rushes with their heeles:

For I am prouerb’d with a Grandsier Phrase,

Ile be a Candle-holder and looke on,

The game was nere so faire, and I am done.

Mer.

Tut, duns the Mouse, the Constables owne word,

If thou art dun, weele draw thee from the mire.

Or saue your reuerence loue, wherein thou stickest

Vp to the eares, come we burne day-light ho.

Rom.

Nay that’s not so.

Mer.

I meane sir I delay,

We wast our lights in vaine, lights, lights, by day;

Take our good meaning, for our Iudgement sits

Fiue times in that, ere once in our fiue wits.

Rom.

And we meane well in going to this Maske,

But ’tis no wit to go.

Rom.

I dreampt a dreame to night.

Mer.

And so did I.

Mer.

That dreamers often lye.

Ro.

In bed a sleepe while they do dreame things true.

Mer.

O then I see Queene Mab hath beene with you:

She is the Fairies Midwife, & she comes in shape no big

ger then Agat-stone, on the fore-finger of an Alderman,

drawne with a teeme of little Atomies, ouer mens noses as

they lie asleepe: her Waggon Spokes made of long Spinners

legs: the Couer of the wings of Grashoppers, her

Traces of the smallest Spiders web, her coullers of the

Moonshines watry Beames, her Whip of Crickets bone,

the Lash of Philome, her Waggoner, a small gray-coated

Gnat, not halfe so bigge as a round little Worme, prickt

from the Lazie-finger of a man. Her Chariot is an emptie

Haselnut, made by the Ioyner Squirrel or old Grub, time

out a mind, the Faries Coach-makers: & in this state she

gallops night by night, through Louers braines: and then

they dreame of Loue. On Courtiers knees, that dreame on

Cursies strait: ore Lawyers fingers, who strait dreamt on

Fees, ore Ladies lips, who strait on kisses dreame, which

oft the angry Mab with blisters plagues, because their

breath with Sweet meats tainted are. Sometime she gallops

ore a Courtiers nose, & then dreames he of smelling

out a sute: & somtime comes she with Tith pigs tale, tickling

a Parsons nose as a lies asleepe, then he dreames of

another Benefice. Sometime she driueth ore a Souldiers

necke, & then dreames he of cutting Forraine throats, of

Breaches, Ambuscados, Spanish Blades: Of Healths fiue

Fadome deepe, and then anon drums in his eares, at which

he startes and wakes; and being thus frighted, sweares a

prayer or two & sleepes againe: this is that very Mab that

plats the manes of Horses in the night: & bakes the Elklocks

in foule sluttish haires, which once vntangled, much

misfortune bodes,

This is the hag, when Maides lie on their backs,

That presses them, and learnes them first to beare,

Making them women of good carriage:

This is she.

Rom.

Peace, peace, Mercutio peace,

Thou talk’st of nothing.

Mer.

True, I talke of dreames:

Which are the children of an idle braine,

Begot of nothing, but vaine phantasie,

Which is as thin of substance as the ayre,

And more inconstant then the wind, who wooes

Euen now the frozen bosome of the North:

And being anger’d, puffes away from thence,

Turning his side to the dew dropping South.

Ben.

This wind you talke of blowes vs from our selues,

Supper is done, and we shall come too late.

Rom.

I feare too early, for my mind misgiues,

Some consequence yet hanging in the starres,

Shall bitterly begin his fearefull date

With this nights reuels, and expire the tearme

Of a despised life clos’d in my brest:

By some vile forfeit of vntimely death.

But he that hath the stirrage of my course,

Direct my sute: on lustie Gentlemen.

Ben.

Strike Drum.

They march about the Stage, and Seruingmen come forth

with their napkins.

Enter Seruant.

Ser.

Where’s Potpan, that he helpes not to take away?

He shift a Trencher? he scrape a Trencher?

1.

When good manners, shall lie in one or two mens

hands, and they vnwasht too, ’tis a foule thing.

Ser.

Away with the Ioynstooles, remoue the Court-

cubbord, looke to the Plate: good thou, saue mee a piece

of Marchpane, and as thou louest me, let the Porter let in

Susan Grindstone, and Nell, Anthonie and Potpan.

2.

I Boy readie.

Ser.

You are lookt for, and cal’d for, askt for, & sought

for, in the great Chamber.

1

We cannot be here and there too, chearly Boyes,

Exeunt.Be brisk awhile, and the longer liuer take all.

Enter all the Guests and Gentlewomen to the

Maskers.

1. Capu.

Welcome Gentlemen,

Ladies that haue their toes

Vnplagu’d with Cornes, will walke about with you:

Ah my Mistresses, which of you all

Will now deny to dance? She that makes dainty,

She Ile sweare hath Cornes: am I come neare ye now?

Welcome Gentlemen, I haue seene the day

That I haue worne a Visor, and could tell

A whispering tale in a faire Ladies eare:

Such as would please: ’tis gone, ’tis gone, ’tis gone,

You are welcome Gentlemen, come Musitians play:

Musicke plaies: and the dance.

A Hall, Hall, giue roome, and foote it Girles,

More light you knaues, and turne the Tables vp:

And quench the fire, the Roome is growne too hot.

Ah sirrah, this vnlookt for sport comes well:

Nay sit, nay sit, good Cozin Capulet,

For you and I are past our dauncing daies:

How long ‘ist now since last your selfe and I

Were in a Maske?

2. Capu.

Berlady thirty yeares.

1. Capu.

What man: ’tis not so much, ’tis not so much,

‘Tis since the Nuptiall of Lucentio,

Come Pentycost as quickely as it will,

Some fiue and twenty yeares, and then we Maskt.

2. Cap.

‘Tis more, ’tis more, his Sonne is elder sir:

His Sonne is thirty.

3. Cap.

Will you tell me that?

His Sonne was but a Ward two yeares agoe.

Rom.

What Ladie is that which doth inrich the hand

Of yonder Knight?

Ser.

I know not sir.

Rom.

O she doth teach the Torches to burne bright:

It seemes she hangs vpon the cheeke of night,

As a rich Iewel in an Æthiops eare:

Beauty too rich for vse, for earth too deare:

So shewes a Snowy Doue trooping with Crowes,

As yonder Lady ore her fellowes showes;

The measure done, Ile watch her place of stand,

And touching hers, make blessed my rude hand.

Did my heart loue till now, forsweare it sight,

For I neuer saw true Beauty till this night.

Tib.

This by his voice, should be a Mountague.

Fetch me my Rapier Boy, what dares the slaue

Come hither couer’d with an antique face,

To fleere and scorne at our Solemnitie?

Now by the stocke and Honour of my kin,

To strike him dead I hold it not a sin.

Cap.

Why how now kinsman,

Wherefore storme you so?

Tib.

Vncle this is a Mountague, our foe:

A Villaine that is hither come in spight,

To scorne at our Solemnitie this night.

Cap.

Young Romeo is it?

Tib.

‘Tis he, that Villaine Romeo.

Cap.

Content thee gentle Coz, let him alone,

A beares him like a portly Gentleman:

And to say truth, Verona brags of him,

To be a vertuous and well gouern’d youth:

I would not for the wealth of all the towne,

Here in my house do him disparagement:

Therfore be patient, take no note of him,

It is my will, the which if thou respect,

Shew a faire presence, and put off these frownes,

An ill beseeming semblance for a Feast.

Tib.

It fits when such a Villaine is a guest,

Ile not endure him.

Cap.

He shall be endur’d.

What goodman boy, I say he shall, go too,

Am I the Maister here or you? go too,

Youle not endure him, God shall mend my soule,

Youle make a Mutinie among the Guests:

You will set cocke a hoope, youle be the man.

Tib.

Why Vncle, ’tis a shame.

Cap.

Go too, go too,

You are a sawcy Boy, ‘ist so indeed?

This tricke may chance to scath you, I know what,

You must contrary me, marry ’tis time.

Well said my hearts, you are a Princox, goe,

Be quiet, or more light, more light for shame,

Ile make you quiet. What, chearely my hearts.

Tib.

Patience perforce, with wilfull choler meeting,

Makes my flesh tremble in their different greeting:

I will withdraw, but this intrusion shall

Exit.Now seeming sweet, conuert to bitter gall.

Rom.

If I prophane with my vnworthiest hand,

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this,

My lips to blushing Pilgrims did ready stand,

To smooth that rough touch, with a tender kisse.

Iul.

Good Pilgrime,

You do wrong your hand too much.

Which mannerly deuotion shewes in this,

For Saints haue hands, that Pilgrims hands do tuch,

And palme to palme, is holy Palmers kisse.

Rom.

Haue not Saints lips, and holy Palmers too?

Iul.

I Pilgrim, lips that they must vse in prayer.

Rom.

O then deare Saint, let lips do what hands do,

They pray (grant thou) least faith turne to dispaire.

Iul.

Saints do not moue,

Though grant for prayers sake.

Rom.

Then moue not while my prayers effect I take:

Thus from my lips, by thine my sin is purg’d.

Iul.

Then haue my lips the sin that they haue tooke.

Rom.

Sin from my lips? O trespasse sweetly vrg’d:

Giue me my sin againe.

Iul.

You kisse by’th’booke.

Nur.

Madam your Mother craues a word with you.

Rom.

What is her Mother?

Nurs.

Marrie Batcheler,

Her Mother is the Lady of the house,

And a good Lady, and a wise, and Vertuous,

I Nur’st her Daughter that you talkt withall:

I tell you, he that can lay hold of her,

Shall haue the chincks.

Rom.

Is she a Capulet?

O deare account! My life is my foes debt.

Ben.

Away, be gone, the sport is at the best.

Rom.

I so I feare, the more is my vnrest.

Cap.

Nay Gentlemen prepare not to be gone,

We haue a trifling foolish Banquet towards:

Is it e’ne so? why then I thanke you all.

I thanke you honest Gentlemen, good night:

More Torches here: come on, then let’s to bed.

Ah sirrah, by my faie it waxes late,

Ile to my rest.

Iuli.

Come hither Nurse,

What is yond Gentleman:

Nur.

The Sonne and Heire of old Tyberio.

Iuli.

What’s he that now is going out of doore?

Nur.

Marrie that I thinke be young Petruchio.

Iul.

What’s he that follows here that would not dance?

Nur.

I know not.

Iul.

Go aske his name: if he be married,

My graue is like to be my wedded bed.

Nur.

His name is Romeo, and a Mountague,

The onely Sonne of your great Enemie.

Iul.

My onely Loue sprung from my onely hate,

Too early seene, vnknowne, and knowne too late,

Prodigious birth of Loue it is to me,

That I must loue a loathed Enemie.

Nur.

What’s this? whats this?

Iul.

A rime, I learne euen now

Of one I dan’st withall.

One cals within, Iuliet.

Nur.

Anon, anon:

Exeunt.Come let’s away, the strangers all are gone.

Chorus.

Now old desire doth in his death bed lie,

And yong affection gapes to be his Hei […],

That faire, for which Loue gron’d for and would die,

With tender Iuliet matcht, is now not faire.

Now Romeo is beloued, and Loues againe,

A like bewitched by the charme of lookes:

But to his foe suppose’d he must complaine,

And she steale Loues sweet bait from fearefull hookes:

Being held a foe, he may not haue accesse

To breath such vowes as Louers vse to sweare,

And she as much in Loue, her meanes much lesse,

To meete her new Beloued any where:

But passion lends them Power, time, meanes to meete,

Temp’ring extremities with extreame sweete.

Enter Romeo alone.

Rom.

Can I goe forward when my heart is here?

Turne backe dull earth, and find thy Center out.

Enter Benuolio with Mercutio.

Ben.

Romeo, my Cozen Romeo, Romeo.

Merc.

He is wise,

And on my life hath stolne him home to bed.

Ben.

He ran this way and leapt this Orchard wall.

Call good Mercutio:

Nay, Ile coniure too.

Mer.

Romeo, Humours, Madman, Passion, Louer,

Appeare thou in the likenesse of a sigh,

Speake but one rime, and I am satisfied:

Cry me but ay me, Prouant, but Loue and day,

Speake to my goship Venus one faire word,

One Nickname for her purblind Sonne and her,

Young Abraham Cupid he that shot so true,

When King Cophetua lou’d the begger Maid,

He heareth not, he stirreth not, he moueth not,

The Ape is dead, I must coniure him,

I coniure thee by Rosalines bright eyes,

By her High forehead, and her Scarlet lip,

By her Fine foote, Straight leg, and Quiuering thigh,

And the Demeanes, that there Adiacent lie,

That in thy likenesse thou appeare to vs.

Ben.

And if he heare thee thou wilt anger him.

Mer.

This cannot anger him, t’would anger him

To raise a spirit in his Mistresse circle,

Of some strange nature, letting it stand

Till she had laid it, and coniured it downe,

That were some spight.

My inuocation is faire and honest, & in his Mistris name,

I coniure onely but to raise vp him.

Ben.

Come, he hath hid himselfe among these Trees

To be consorted with the Humerous night:

Blind is his Loue, and best befits the darke.

Mer.

If Loue be blind, Loue cannot hit the marke,

Now will he sit vnder a Medler tree,

And wish his Mistresse were that kind of Fruite,

As Maides call Medlers when they laugh alone,

O Romeo that she were, O that she were

An open, or thou a Poprin Peare,

Romeo goodnight, Ile to my Truckle bed,

This Field bed is to cold for me to sleepe,

Come shall we go?

Ben.

Go then, for ’tis in vaine to seeke him here

Exeunt.That meanes not to be found.

Rom.

He ieasts at Scarres that neuer felt a wound,

But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the East, and Iuliet is the Sunne,

Arise faire Sun and kill the enuious Moone,

Who is already sicke and pale with griefe,

That thou her Maid art far more faire then she:

Be not her Maid since she is enuious,

Her Vestal liuery is but sicke and greene,

And none but fooles do weare it, cast it off:

It is my Lady, O it is my Loue, O that she knew she were,

She speakes, yet she sayes nothing, what of that?

Her eye discourses, I will answere it:

I am too bold ’tis not to me she speakes:

Two of the fairest starres in all the Heauen,

Hauing some businesse do entreat her eyes,

To twinckle in their Spheres till they returne.

What if her eyes were there, they in her head,

The brightnesse of her cheeke would shame those starres,

As day-light doth a Lampe, her eye in heauen,

Would through the ayrie Region streame so bright,

That Birds would sing, and thinke it were not night:

See how she leanes her cheeke vpon her hand.

O that I were a Gloue vpon that hand,

That I might touch that cheeke.

Iul.

Ay me.

Rom.

She speakes.

Oh speake againe bright Angell, for thou art

As glorious to this night being ore my head,

As is a winged messenger of heauen

Vnto the white vpturned wondring eyes

Of mortalls that fall backe to gaze on him,

When he bestrides the lazie puffing Cloudes,

And sailes vpon the bosome of the ayre.

Iul.

O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

Denie thy Father and refuse thy name:

Or if thou wilt not, be but sworne my Loue,

And Ile no longer be a Capulet.

Rom.

Shall I heare more, or shall I speake at this?

Iu.

‘Tis but thy name that is my Enemy:

Thou art thy selfe, though not a Mountague,

What’s Mountague? it is nor hand nor foote,

Nor arme, nor face, O be some other name

Belonging to a man.

What? in a names that which we call a Rose,

By any other word would smell as sweete,

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo cal’d,

Retaine that deare perfection which he owes,

Without that title Romeo, doffe thy name,

And for thy name which is no part of thee,

Take all my selfe.

Rom.

I take thee at thy word:

Call me but Loue, and Ile be new baptiz’d,

Hence foorth I neuer will be Romeo.

Iuli.

What man art thou, that thus bescreen’d in night

So stumblest on my counsell?

Rom.

By a name,

I know not how to tell thee who I am:

My name deare Saint, is hatefull to my selfe,

Because it is an Enemy to thee,

Had I it written, I would teare the word.

Iuli.

My eares haue yet not drunke a hundred words

Of thy tongues vttering, yet I know the sound.

Art thou not Romeo, and a Montague?

Rom.

Neither faire Maid, if either thee dislike.

Iul.

How cam’st thou hither.

Tell me, and wherefore?

The Orchard walls are high, and hard to climbe,

And the place death, considering who thou art,

If any of my kinsmen find thee here,

Rom.

With Loues light wings

Did I ore-perch these Walls,

For stony limits cannot hold Loue out,

And what Loue can do, that dares Loue attempt:

Therefore thy kinsmen are no stop to me.

Iul.

If they do see thee, they will murther thee.

Rom.

Alacke there lies more perill in thine eye,

Then twenty of their Swords, looke thou but sweete,

And I am proofe against their enmity.

Iul.

I would not for the world they saw thee here.

Rom.

I haue nights cloake to hide me from their eyes

And but thou loue me, let them finde me here,

My life were better ended by their hate,

Then death proroged wanting of thy Loue.

Iul.

By whose direction found’st thou out this place?

Rom.

By Loue that first did promp me to enquire,

He lent me counsell, and I lent him eyes,

I am no Pylot, yet wert thou as far

As that vast-shore-washet with the farthest Sea,

I should aduenture for such Marchandise.

Iul.

Thou knowest the maske of night is on my face,

Else would a Maiden blush bepaint my cheeke,

For that which thou hast heard me speake to night,

Faine would I dwell on forme, faine, faine, denie

What I haue spoke, but farewell Complement,

Doest thou Loue? I know thou wilt say I,

And I will take thy word, yet if thou swear’st,

Thou maiest proue false: at Louers periuries

They say Ioue laught, oh gentle Romeo,

If thou dost Loue, pronounce it faithfully:

Or if thou thinkest I am too quickly wonne,

Ile frowne and be peruerse, and say thee nay,

So thou wilt wooe: But else not for the world.

In truth faire Mountague I am too fond:

And therefore thou maiest thinke my behauiour light,

But trust me Gentleman, Ile proue more true,

Then those that haue coying to be strange,

I should haue beene more strange, I must confesse,

But that thou ouer heard’st ere I was ware

My true Loues passion, therefore pardon me,

And not impute this yeelding to light Loue,

Which the darke night hath so discouered.

Rom.

Lady, by yonder Moone I vow,

That tips with siluer all these Fruite tree tops.

Iul.

O sweare not by the Moone, th’inconstant Moone,

That monethly changes in her circled Orbe,

Least that thy Loue proue likewise variable.

Rom.

What shall I sweare by?

Iul.

Do not sweare at all:

Or if thou wilt sweare by thy gratious selfe,

Which is the God of my Idolatry,

And Ile beleeue thee.

Rom.

If my hearts deare loue.

Iuli.

Well do not sweare, although I ioy in thee:

I haue no ioy of this contract to night,

It is too rash, too vnaduis’d, too sudden,

Too like the lightning which doth cease to be

Ere, one can say, it lightens, Sweete good night:

This bud of Loue by Summers ripening breath,

May proue a beautious Flower when next we meete:

Goodnight, goodnight, as sweete repose and rest,

Come to thy heart, as that within my brest.

Rom.

O wilt thou leaue me so vnsatisfied?

Iuli.

What satisfaction can’st thou haue to night?

Ro.

Th’exchange of thy Loues faithfull vow for mine.

Iul.

I gaue thee mine before thou did’st request it:

And yet I would it were to giue againe.

Rom.

Would’st thou withdraw it,

For what purpose Loue?

Iul.

But to be franke and giue it thee againe,

And yet I wish but for the thing I haue,

My bounty is as boundlesse as the Sea,

My Loue as deepe, the more I giue to thee

The more I haue, for both are Infinite:

I heare some noyse within deare Loue adue:

Cals within.

Anon good Nurse, sweet Mountague be true:

Stay but a little, I will come againe.

Rom.

O blessed blessed night, I am afear’d

Being in night, all this is but a dreame,

Too flattering sweet to be substantiall.

Iul.

Three words deare Romeo,

And goodnight indeed,

If that thy bent of Loue be Honourable,

Thy purpose marriage, send me word to morrow,

By one that Ile procure to come to thee,

Where and what time thou wilt performe the right,

And all my Fortunes at thy foote Ile lay,

And follow thee my Lord throughout the world.

Within: Madam.

I come, anon: but if thou meanest not well,

Within: Madam.I do beseech theee

(By and by I come)

To cease thy strife, and leaue me to my griefe,

To morrow will I send.

Rom.

So thriue my soule.

Iu.

Exit.A thousand times goodnight.

Rome.

A thousand times the worse to want thy light,

Loue goes toward Loue as school-boyes frō thier books

But Loue frō Loue, towards schoole with heauie lookes.

Enter Iuliet againe.

Iul.

Hist Romeo hist: O for a Falkners voice,

To lure this Tassell gentle backe againe,

Bondage is hoarse, and may not speake aloud,

Else would I teare the Caue where Eccho lies,

And make her ayrie tongue more hoarse, then

With repetition of my Romeo.

Rom.

It is my soule that calls vpon my name.

How siluer sweet, sound Louers tongues by night,

Like softest Musicke to attending eares.

Iul.

Romeo.

Rom.

My Neece.

Iul.

What a clock to morrow

Shall I send to thee?

Rom.

By the houre of nine.

Iul.

I will not faile, ’tis twenty yeares till then,

I haue forgot why I did call thee backe.

Rom.

Let me stand here till thou remember it.

Iul.

I shall forget, to haue thee still stand there,

Remembring how I Loue thy company.

Rom.

And Ile still stay, to haue thee still forget,

Forgetting any other home but this.

Iul.

‘Tis almost morning, I would haue thee gone,

And yet no further then a wantons Bird,

That let’s it hop a little from his hand,

Like a poore prisoner in his twisted Gyues,

And with a silken thred plucks it backe againe,

So louing Iealous of his liberty.

Rom.

I would I were thy Bird.

Iul.

Sweet so would I,

Yet I should kill thee with much cherishing:

Good night, good night.

Rom.

Parting is such sweete sorrow,

That I shall say goodnight, till it be morrow.

Iul.

Sleepe dwell vpon thine eyes, peace in thy brest.

Rom.

Would I were sleepe and peace so sweet to rest,

The gray ey’d morne smiles on the frowning night,

Checkring the Easterne Clouds with streakes of light,

And darkenesse fleckel’d like a drunkard reeles,

From forth dayes pathway, made by Titans wheeles.

Hence will I to my ghostly Fries close Cell,

Exit.His helpe to craue, and my deare hap to tell.

Enter Frier alone with a basket.

Fri.

The gray ey’d morne smiles on the frowning night,

Checkring the Easterne Cloudes with streaks of light:

And fleckled darknesse like a drunkard reeles,

From forth daies path, and Titans burning wheeles:

Now ere the Sun aduance his burning eye,

The day to cheere, and nights danke dew to dry,

I must vpfill this Osier Cage of ours,

With balefull weedes, and precious Iuiced flowers,

The earth that’s Natures mother, is her Tombe,

What is her burying graue that is her wombe:

And from her wombe children of diuers kind

We sucking on her naturall bosome find:

Many for many vertues excellent:

None but for some, and yet all different.

O mickle is the powerfull grace that lies

In Plants, Hearbs, stones, and their true qualities:

For nought so vile, that on earth doth liue,

But to the earth some speciall good doth giue.

Nor ought so good, but strain’d from that faire vse,

Reuolts from true birth, stumbling on abuse.

Vertue it selfe turnes vice being misapplied,

And vice sometime by action dignified.

Enter Romeo.

Within the infant rin’d of this weake flower,

Poyson hath residence, and medicine power:

For this being smelt, with that part cheares each part,

Being tasted slayes all sences with the heart.

Two such opposed Kings encampe them still,

In man as well as Hearbes, grace and rude will:

And where the worser is predominant,

Full soone the Canker death eates vp that Plant.

Rom.

Good morrow Father.

Fri.

Benedecite.

What early tongue so sweet saluteth me?

Young Sonne, it argues a distempered head,

So soone to bid goodmorrow to thy bed;

Care keepes his watch in euery old mans eye,

And where Care lodges, sleepe will neuer lye:

But where vnbrused youth with vnstuft braine

Doth couch his lims, there, golden sleepe doth raigne;

Therefore thy earlinesse doth me assure,

Thou art vprous’d with some distemprature;

Or if not so, then here I hit it right.

Our Romeo hath not beene in bed to night.

Rom.

That last is true, the sweeter rest was mine.

Fri.

God pardon sin: wast thou with Rosaline?

Rom.

With Rosaline, my ghostly Father? No,

I haue forgot that name, and that names woe.

Fri.

That’s my good Son, but wher hast thou bin then?

Rom.

Ile tell thee ere thou aske it me agen:

I haue beene feasting with mine enemie,

Where on a sudden one hath wounded me,

That’s by me wounded: both our remedies

Within thy helpe and holy phisicke lies:

I beare no hatred, blessed man: for loe

My intercession likewise steads my foe.

Fri.

Be plaine good Son, rest homely in thy drift,

Ridling confession, findes but ridling shrift.

Rom.

Then plainly know my hearts deare Loue is set,

On the faire daughter of rich Capulet:

As mine on hers, so hers is set on mine;

And all combin’d, saue what thou must combine

By holy marriage: when and where, and how,

We met, we wooed, and made exchange of vow:

Ile tell thee as we passe, but this I pray,

That thou consent to marrie vs to day.

Fri.

Holy S. Francis, what a change is heere?

Is Rosaline that thou didst Loue so deare

So soone forsaken? young mens Loue then lies

Not truely in their hearts, but in their eyes.

Iesu Maria, what a deale of brine

Hath washt thy sallow cheekes for Rosaline?

How much salt water throwne away in wast,

To season Loue that of it doth not tast.

The Sun not yet thy sighes, from heauen cleares,

Thy old grones yet ringing in my auncient eares:

Lo here vpon thy cheeke the staine doth sit,

Of an old teare that is not washt off yet.

If ere thou wast thy selfe, and these woes thine,

Thou and these woes, were all for Rosaline.

And art thou chang’d? pronounce this sentence then,

Women may fall, when there’s no strength in men.

Rom.

Thou chid’st me oft for louing Rosaline.

Fri.

For doting, not for louing pupill mine.

Rom.

And bad’st me bury Loue.

Fri.

Not in a graue,

To lay one in, another out to haue.

Rom.

I pray thee chide me not, her I Loue now

Doth grace for grace, and Loue for Loue allow:

The other did not so.

Fri.

O she knew well,

Thy Loue did read by rote, that could not spell:

But come young wauerer, come goe with me,

In one respect, Ile thy assistant be:

For this alliance may so happy proue,

To turne your houshould rancor to pure Loue.

Rom.

O let vs hence, I stand on sudden hast.

Fri.

Exeunt.Wisely and slow, they stumble that run fast.

Enter Benuolio and Mercutio.

Mer.

Where the deu’le should this Romeo be? came he

not home to night?

Ben.

Not to his Fathers, I spoke with his man.

Mer.

Why that same pale hard-harted wench, that Ro

saline torments him so, that he will sure run mad.

Ben.

Tibalt, the kinsman to old Capulet, hath sent a

Letter to his Fathers house.

Mer.

A challenge on my life.

Ben.

Romeo will answere it.

Mer.

Any man that can write, may answere a Letter.

Ben.

Nay, he will answere the Letters Maister how he

dares, being dared.

Mer.

Alas poore Romeo, he is already dead stab’d with

a white wenches blacke eye, runne through the eare with

a Loue song, the very pinne of his heart, cleft with the

blind Bowe-boyes but-shaft, and is he a man to encounter

Tybalt?

Ben.

Why what is Tibalt?

Mer.

More then Prince of Cats. Oh hee’s the Couragious

Captaine of Complements: he fights as you sing

pricksong, keeps time, distance, and proportion, he rests

his minum, one, two, and the third in your bosom: the very

butcher of a silk button, a Dualist, a Dualist: a Gentleman

of the very first house of the first and second cause: ah the

immortall Passado, the Punto reuerso, the Hay.

Ben.

The what?

Mer.

The Pox of such antique lisping affecting phantacies,

these new tuners of accent: Iesu a very good blade,

a very tall man, a very good whore. Why is not this a

lamentable thing Grandsire, that we should be thus afflicted

with these strange flies: these fashion Mongers, these

pardon-mee’s, who stand so much on the new form, that they

cannot sit at ease on the old bench. O their bones, their

bones.

Enter Romeo.

Ben.

Here comes Romeo, here comes Romeo.

Mer.

Without his Roe, like a dryed Hering. O flesh,

flesh, how art thou fishified? Now is he for the numbers

that Petrarch flowed in: Laura to his Lady, was a kitchen

wench, marrie she had a better Loue to berime her: Dido

a dowdie, Cleopatra a Gipsie, Hellen and Hero, hildinsga

and Harlots: Thisbie a gray eie or so, but not to the purpose.

Signior Romeo, Bon iour, there’s a French salutation to your

French slop: you gaue vs the counterfait fairely last

night.

Romeo.

Good morrow to you both, what counterfeit

did I giue you?

Mer.

The slip sir, the slip, can you not conceiue?

Rom.

Pardon Mercutio, my businesse was great, and in

such a case as mine, a man may straine curtesie.

Mer.

That’s as much as to say, such a case as yours con

strains a man to bow in the hams.

Rom.

Meaning to cursie.

Mer.

Thou hast most kindly hit it.

Rom.

A most curteous exposition.

Mer.

Nay, I am the very pinck of curtesie.

Rom.

Pinke for flower.

Mer.

Right.

Rom.

Why then is my Pump well flowr’d.

Mer.

Sure wit, follow me this ieast, now till thou hast

worne out thy Pump, that when the single sole of it is

worne, the ieast may remaine after the wearing, sole-

singular.

Rom.

O single sol’d ieast,

Soly singular for the singlenesse.

Mer.

Come betweene vs good Benuolio, my wits faints.

Rom.

Swits and spurs,

Swits and spurs, or Ile crie a match.

Mer.

Nay, if our wits run the Wild-Goose chase, I am

done: For thou hast more of the Wild-Goose in one of

thy wits, then I am sure I haue in my whole fiue. Was I

with you there for the Goose?

Rom.

Thou wast neuer with mee for any thing, when

thou wast not there for the Goose.

Mer.

I will bite thee by the eare for that iest.

Rom.

Nay, good Goose bite not.

Mer.

Thy wit is a very Bitter-sweeting,

It is a most sharpe sawce.

Rom.

And is it not well seru’d into a Sweet-Goose?

Mer.

Oh here’s a wit of Cheuerell, that stretches from

an ynch narrow, to an ell broad.

Rom.

I stretch it out for that word, broad, which added

to the Goose, proues thee farre and wide, abroad Goose.

Mer.

Why is not this better now, then groning for

Loue, now art thou sociable, now art thou Romeo: now art

thou what thou art, by Art as well as by Nature, for this

driueling Loue is like a great Naturall, that runs lolling

vp and downe to hid his bable in a hole.

Ben.

Stop there, stop there.

Mer.

Thou desir’st me to stop in my tale against the haire.

Ben.

Thou would’st else haue made thy tale large.

Mer.

O thou art deceiu’d, I would haue made it short,

or I was come to the whole depth of my tale, and meant

indeed to occupie the argument no longer.

Enter Nurse and her man.

Rom.

Here’s a goodly geare.

A sayle, a sayle.

Mer.

Two, two: a Shirt and a Smocke.

Nur.

Peter?

Peter.

Anon.

Nur.

My Fan Peter?

Mer.

Good Peter to hide her face?

For her Fans the fairer face?

Nur.

God ye good morrow Gentlemen.

Mer.

God ye gooden faire Gentlewoman.

Nur.

Is it gooden?

Mer.

‘Tis no lesse I tell you: for the bawdy hand of the

Dyall is now vpon the pricke of Noone.

Nur.

Out vpon you: what a man are you?

Rom.

One Gentlewoman,

That God hath made, himselfe to mar.

Nur.

By my troth it is said, for himselfe to, mar quath

a Gentlemen, can any of you tel me where I may find

the young Romeo?

Romeo.

I can tell you: but young Romeo will be older

when you haue found him, then he was when you sought

him: I am the youngest of that name, for fault of a worse.

Nur.

You say well.

Mer.

Yea is the worst well,

Very well tooke: Ifaith, wisely, wisely.

Nur.

If you be he sir,

I desire some confidence with you?

Ben.

She will endite him to some Supper.

Mer.

A baud, a baud, a baud. So ho.

Rom.

What hast thou found?

Mer.

No Hare sir, vnlesse a Hare sir in a Lenten pie,

that is something stale and hoare ere it be spent.

An old Hare hoare, and an old Hare hoare is very good

meat in Lent.

But a Hare that is hoare is too much for a score, when it

hoares ere it be spent,

Romeo will you come to your Fathers? Weele to dinner

thither.

Rom.

I will follow you.

Mer.

Farewell auncient Lady:

Exit. Mercutio, Benuolio.Farewell Lady, Lady, Lady.

Nur.

I pray you sir, what sawcie Merchant was this

that was so full of his roperie?

Rom.

A Gentleman Nurse, that loues to heare himselfe

talke, and will speake more in a minute, then he will stand

to in a Moneth.

Nur.

And a speake any thing against me, Ile take him

downe, & a were lustier then he is, and twentie such Iacks:

and if I cannot, Ile finde those that shall: scuruie knaue, I

am none of his flurt-gils, I am none of his skaines mates,

and thou must stand by too and suffer euery knaue to vse

me at his pleasure.

Pet.

I saw no man vse you at his pleasure: if I had, my

weapon should quickly haue beene out, I warrant you, I

dare draw assoone as another man, if I see occasion in a

good quarrell, and the law on my side.

Nur

Now afore God, I am so vext, that euery part about

me quiuers, skuruy knaue: pray you sir a word: and as I

told you, my young Lady bid me enquire you out, what

she bid me say, I will keepe to my selfe: but first let me

tell ye, if ye should leade her in a fooles paradise, as they

say, it were a very grosse kind of behauiour, as they say:

for the Gentlewoman is yong: & therefore, if you should

deale double with her, truely it were an ill thing to be

offered to any Gentlewoman, and very weake dealing.

Nur.

Nurse commend me to thy Lady and Mistresse, I

protest vnto thee.

Nur.

Good heart, and yfaith I will tell her as much:

Lord, Lord she will be a ioyfull woman.

Rom.

What wilt thou tell her Nurse? thou doest not

marke me?

Nur.

I will tell her sir, that you do protest, which as I

take it, is a Gentleman-like offer.

Rom.

Bid her deuise some meanes to come to shrift this afternoone,

And there she shall at Frier Lawrence Cell

Be shriu’d and married: here is for thy paines.

Nur.

No truly sir not a penny.

Rom.

Go too, I say you shall.

Nur

This afternoone sir? well she shall be there.

Ro.

And stay thou good Nurse behind the Abbey wall,

Within this houre my man shall be with thee,

And bring thee Cords made like a tackled staire,

Which to the high top gallant of my ioy,

Must be my conuoy in the secret night.

Farewell, be trustie and Ile quite thy paines:

Farewell, commend me to thy Mistresse.

Nur.

Now God in heauen blesse thee: harke you sir,

Rom.

What saist thou my deare Nurse?

Nurse.

Is your man secret, did you nere heare say two

may keepe counsell putting one away.

Ro.

Warrant thee my man is true as steele.

Nur.

Well sir, my Mistresse is the sweetest Lady, Lord,

Lord, when ’twas a little prating thing. O there is a

Noble man in Towne one Paris, that would faine lay knife

aboard: but she good soule had as leeue a see Toade, a very

Toade as see him: I anger her sometimes, and tell her that

Paris is the properer man, but Ile warrant you, when I say

so, shee lookes as pale as any clout in the versall world.

Doth not Rosemarie and Romeo begin both with a letter?

Rom.

I Nurse, what of that? Both with an R

Nur.

A mocker that’s the dogs name. R. is for the no,

I know it begins with some other letter, and she hath the

prettiest sententious of it, of you and Rosemary, that it

would do you good to heare it.

Rom.

Commend me to thy Lady.

Nur.

I a thousand times. Peter?

Pet.

Anon.

Nur.

Exit Nurse and Peter.Before and apace.

Enter Iuliet.

Iul.

The clocke strook nine, when I did send the Nurse,

In halfe an houre she promised to returne,

Perchance she cannot meete him: that’s not so:

Oh she is lame, Loues Herauld should be thoughts,

Which ten times faster glides then the Sunnes beames,

Driuing backe shadowes ouer lowring hils.

Therefore do nimble Pinion’d Doues draw Loue,

And therefore hath the wind-swift Cupid wings:

Now is the Sun vpon the highmost hill

Of this daies iourney, and from nine till twelue,

I three long houres, yet she is not come.

Had she affections and warme youthfull blood,

She would be as swift in motion as a ball,

My words would bandy her to my sweete Loue,

And his to me, but old folkes,

Many faine as they were dead,

Vnwieldie, slow, heauy, and pale as lead.

Enter Nurse.

O God she comes, O hony Nurse what newes?

Hast thou met with him? send thy man away.

Nur.

Peter stay at the gate.

Iul.

Now good sweet Nurse:

O Lord, why lookest thou sad?

Though newes, be sad, yet tell them merrily.

If good thou sham’st the musicke of sweet newes,

By playing it to me, with so sower a face.

Nur.

I am a weary, giue me leaue awhile,

Fie how my bones ake, what a iaunt haue I had?

Iul.

I would thou had’st my bones, and I thy newes:

Nay come I pray thee speake, good good Nurse speake.

Nur.

Iesu what hast? can you not stay a while?

Do you not see that I am out of breath?

Iul.

How art thou out of breath, when thou hast breth

To say to me, that thou art out of breath?

The excuse that thou dost make in this delay,

Is longer then the tale thou dost excuse.

Is thy newes good or bad? answere to that,

Say either, and Ile stay the circumstance:

Let me be satisfied, ist good or bad?

Nur.

Well, you haue made a simple choice, you know

not how to chuse a man: Romeo, no not he though his face

be better then any mans, yet his legs excels all mens, and

for a hand, and a foote, and a body, though they be not to

be talkt on, yet they are past compare: he is not the flower

of curtesie, but Ile warrant him as gentle a Lambe: go thy

waies wench, serue God. What haue you din’d at home?

Iul.

No no: but all this this did I know before

What saies he of our marriage? what of that?

Nur.

Lord how my head akes, what a head haue I?

It beates as it would fall in twenty peeces.

My backe a tother side: o my backe, my backe:

Beshrew your heart for sending me about

To catch my death with iaunting vp and downe.

Iul.

Ifaith: I am sorrie that thou art so well.

Sweet sweet, sweet Nurse, tell me what saies my Loue?

Nur.

Your Loue saies like an honest Gentleman,

And a courteous, and a kind, and a handsome,

And I warrant a vertuous: where is your Mother?

Iul.

Where is my Mother?

Why she is within, where should she be?

How odly thou repli’st:

Your Loue saies like an honest Gentleman:

Where is your Mother?

Nur.

O Gods Lady deare,

Are you so hot? marrie come vp I trow,

Is this the Poultis for my aking bones?

Henceforward do your messages your selfe.

Iul.

Heere’s such a coile, come what saies Romeo?

Nur.

Haue you got leaue to go to shrift to day?

Iul.

I haue.

Nur.

Then high you hence to Frier Lawrence Cell,

There staies a Husband to make you a wife:

Now comes the wanton bloud vp in your cheekes,

Thei’le be in Scarlet straight at any newes:

Hie you to Church, I must an other way,

To fetch a Ladder by the which your Loue

Must climde a birds nest Soone when it is darke:

I am the drudge, and toile in your delight:

But you shall beare the burthen soone at night.

Go Ile to dinner, hie you to the Cell.

Iul.

Exeunt.Hie to high Fortune, honest Nurse, farewell.

Enter Frier and Romeo.

Fri.

So smile the heauens vpon this holy act,

That after houres, with sorrow chide vs not.

Rom.

Amen, amen, but come what sorrow can,

It cannot counteruaile the exchange of ioy

That one short minute giues me in her sight:

Do thou but close our hands with holy words,

Then Loue-deuouring death do what he dare,

It is inough. I may but call her mine.

Fri.

These violent delights haue violent endes,

And in their triumph: die like fire and powder;

Which as they kisse consume. The sweetest honey

Is loathsome in his owne deliciousnesse,

And in the taste confoundes the appetite.

Therefore Loue moderately, long Loue doth so,

Too swift arriues as tardie as too slow.

Enter Iuliet.

Here comes the Lady. Oh so light a foot

Will nere weare out the euerlasting flint,

A Louer may bestride the Gossamours,

That ydles in the wanton Summer ayre,

And yet not fall, so light is vanitie.

Iul.

Good euen to my ghostly Confessor.

Fri.

Romeo shall thanke thee Daughter for vs both.

Iul.

As much to him, else in his thanks too much.

Fri.

Ah Iuliet, if the measure of thy ioy

Be heapt like mine, and that thy skill be more

To blason it, then sweeten with thy breath

This neighbour ayre, and let rich musickes tongue,

Vnfold the imagin’d happinesse that both

Receiue in either, by this deere encounter.

Iul.

Conceit more rich in matter then in words,

Brags of his substance, not of Ornament:

They are but beggers that can count their worth,

But my true Loue is growne to such such excesse,

I cannot sum vp some of halfe my wealth.

Fri.

Come, come with me, & we will make short worke,

For by your leaues, you shall not stay alone,

Till holy Church incorporate two in one.

Enter Mercutio, Benuolio, and men.

Ben.

I pray thee good Mercutio lets retire,

The day is hot, the Capulets abroad:

And if we meet, we shal not scape a brawle, for now these

hot dayes, is the mad blood stirring.

Mer.

Thou art like one of these fellowes, that when he

enters the confines of a Tauerne, claps me his Sword vpon

the Table, and sayes, God send me no need of thee: and by

the operation of the second cup, drawes him on the Drawer,

when indeed there is no need.

Ben.

Am I like such a Fellow?

Mer.

Come, come, thou art as hot a Iacke in thy mood,

as any in Italieand assoone moued to be moodie, and as

soone moodie to be mou’d.

Ben.

And what too?

Mer.

Nay, and there were two such, we should haue

none shortly, for one would kill the other: thou, why thou

wilt quarrell with a man that hath a haire more, or a haire

lesse in his beard, then thou hast: thou wilt quarrell with a

man for cracking Nuts, hauing no other reason, but because

thou hast hasell eyes: what eye, but such an eye,

would spie out such a quarrell? thy head is full of quarrels,

as an egge is full of meat, and yet thy head hath bin

beaten as addle as an egge for quarreling: thou hast quarrel’d

with a man for coffing in the street, because he hath

wakened thy Dog that hath laine asleepe in the Sun. Did’st

thou not fall out with a Tailor for wearing his new Doublet

before Easter? with another, for tying his new shooes

with old Riband, and yet thou wilt Tutor me from

quarrelling?

Ben.

And I were so apt to quarell as thou art, any man

should buy the Fee-simple of my life, for an houre and a

quarter.

Mer.

The Fee-simple? O simple.

Enter Tybalt, Petruchio, and others.

Ben.

By my head here comes the Capulets.

Mer.

By my heele I care not.

Tyb.

Follow me close, for I will speake to them.

Gentlemen, Good den, a word with one of you.

Mer.

And but one word with one of vs? couple it with

something, make it a word and a blow.

Tib.

You shall find me apt inough to that sir, and you

will giue me occasion.

Mercu.

Could you not take some occasion without giuing?

Tib.

Mercutio thou consort’st with Romeo.

Mer.

Consort? what dost thou make vs Minstrels? &

thou make Minstrels of vs, looke to heare nothing but dis

cords: heere’s my fiddlesticke, heere’s that shall make you

daunce. Come consort.

Ben.

We talke here in the publike haunt of men:

Either withdraw vnto some priuate place,

Or reason coldly of your greeuances:

Or else depart, here all eies gaze on vs.

Mer.

Mens eyes were made to looke, and let them gaze.

I will not budge for no mans pleasure I.

Enter Romeo.

Tib.

Well peace be with you sir, here comes my man.

Mer.

But Ile be hang’d sir if he weare your Liuery:

Marry go before to field, heele be your follower,

Your worship in that sense, may call him man.

Tib.

Romeo, the loue I beare thee, can affoord

No better terme then this: Thou art a Villaine.

Rom.

Tibalt, the reason that I haue to loue thee,

Doth much excuse the appertaining rage

To such a greeting: Villaine am I none;

Therefore farewell, I see thou know’st me not.

Tib.

Boy, this shall not excuse the iniuries

That thou hast done me, therefore turne and draw.

Rom.

I do protest I neuer iniur’d thee,

But lou’d thee better then thou can’st deuise:

Till thou shalt know the reason of my loue,

And so good Capulet, which name I tender

As dearely as my owne, be satisfied.

Mer.

O calme, dishonourable, vile submission:

Alla stucatho carries it away.

Tybalt, you Rat-catcher, will you walke?

Tib.

What wouldst thou haue with me?

Mer.

Good King of Cats, nothing but one of your nine

liues, that I meane to make bold withall, and as you shall

vse me hereafter dry beate the rest of the eight. Will you

pluck your Sword out of his Pilcher by the eares? Make

hast, least mine be about your eares ere it be out.

Tib.

I am for you.

Rom.

Gentle Mercutio, put thy Rapier vp.

Mer.

Come sir, your Passado.

Rom.

Draw Benuolio, beat downe their weapons:

Gentlemen, for shame forbeare this outrage,

Tibalt, Mercutio, the Prince expresly hath

Forbidden bandying in Verona streetes.

Exit Tybalt.Hold Tybalt, good Mercutio.

Mer.

I am hurt.

A plague a both the Houses, I am sped:

Is he gone and hath nothing?

Ben.

What art thou hurt?

Mer.

I, I, a scratch, a scratch, marry ’tis inough,

Where is my Page? go Villaine fetch a Surgeon.

Rom.

Courage man, the hurt cannot be much.

Mer.

No: ’tis not so deepe as a well, nor so wide as a

Church doore, but ’tis inough, ’twill serue: aske for me to

morrow, and you shall find me a graue man. I am pepper’d

I warrant, for this world: a plague a both your houses.

What, a Dog, a Rat, a Mouse, a Cat to scratch a man to

death: a Braggart, a Rogue, a Villaine, that fights by the

booke of Arithmeticke, why the deu’le came you betweene

vs? I was hurt vnder your arme.

Rom.

I thought all for the best.

Mer.

Helpe me into some house Benuolio,

Or I shall faint: a plague a both your houses.

They haue made wormes meat of me,

Exit.I haue it, and soundly to your Houses.

Rom.

This Gentleman the Princes neere Alie,

My very Friend hath got his mortall hurt

In my behalfe, my reputation stain’d

With Tibalts slaunder, Tybalt that an houre

Hath beene my Cozin: O Sweet Iuliet,

Thy Beauty hath made me Effeminate,

And in my temper softned Valours steele.

Enter Benuolio.

Ben.

O Romeo, Romeo, braue Mercutio’s is dead,

That Gallant spirit hath aspir’d the Cloudes,

Which too vntimely here did scorne the earth.

Rom.

This daies blacke Fate, on mo daies doth depend,

This but begins, the wo others must end.

Enter Tybalt.

Ben.

Here comes the Furious Tybalt backe againe.

Rom.

He gon in triumph, and Mercutio slaine?

Away to heauen respectiue Lenitie,

And fire and Fury, be my conduct now.

Now Tybalt take the Villaine backe againe

That late thou gau’st me, for Mercutios soule

Is but a little way aboue our heads,

Staying for thine to keepe him companie:

Either thou or I, or both, must goe with him.

Tib.

Thou wretched Boy that didst consort him here,

Shalt with him hence.

Rom.

This shall determine that.

They fight. Tybalt falles.

Ben.

Romeo, away be gone:

The Citizens are vp, and Tybalt slaine,

Stand not amaz’d, the Prince will Doome thee death

If thou art taken: hence, be gone, away.

Rom.

O! I am Fortunes foole.

Ben.

Exit Romeo.Why dost thou stay?

Enter Citizens.

Citi.

Which way ran he that kild Mercutio?

Tibalt that Murtherer, which way ran he?

Ben.

There lies that Tybalt.

Citi.

Vp sir go with me:

I charge thee in the Princes names obey.

Enter Prince, old Montague, Capulet, their

Wiues and all.

Prin.

Where are the vile beginners of this Fray?

Ben.

O Noble Prince, I can discouer all

The vnluckie Mannage of this fatall brall:

There lies the man slaine by young Romeo,

That slew thy kinsman braue Mercutio.

Cap. Wi.

Tybalt, my Cozin? O my Brothers Child,

O Prince, O Cozin, Husband, O the blood is spild

Of my deare kinsman. Prince as thou art true,

For bloud of ours, shed bloud of Mountague.

O Cozin, Cozin.

Prin.

Benuolio, who began this Fray?

Ben.

Tybalt here slaine, whom Romeo’s hand slay,

Romeo that spoke him faire, bid him bethinke

How nice the Quarrell was, and vrg’d withall

Your high displeasure: all this vttered,

With gentle breath, calme looke, knees humbly bow’d

Could not take truce with the vnruly spleene

Of Tybalts deafe to peace, but that he Tilts

With Peircing steele at bold Mercutio’s breast,

Who all as hot, turnes deadly point to point,

And with a Martiall scorne, with one hand beates

Cold death aside, and with the other sends

It back to Tybalt, whose dexterity

Retorts it: Romeo he cries aloud,

Hold Friends, Friends part, and swifter then his tongue,

His aged arme beats downe their fatall points,

And twixt them rushes, vnderneath whose arme,

An enuious thrust from Tybalt, hit the life

Of stout Mercutio, and then Tybalt fled.

But by and by comes backe to Romeo,

Who had but newly entertained Reuenge,

And too’t they goe like lightning, for ere I

Could draw to part them, was stout Tybalt slaine:

And as he fell, did Romeo turne and flie:

This is the truth, or let Benuolio die.

Cap. Wi.

He is a kinsman to the Mountague,

Affection makes him false, he speakes not true:

Some twenty of them fought in this blacke strife,

And all those twenty could but kill one life.

I beg for Iustice, which thou Prince must giue:

Romeo slew Tybalt, Romeo must not liue.

Prin.

Romeo slew him, he slew Mercutio,

Who now the price of his deare blood doth owe.

Cap.

Not Romeo Prince, he was Mercutios Friend,

His fault concludes, but what the law should end,

The life of Tybalt.

Prin.

And for that offence,

Immediately we doe exile him hence:

I haue an interest in your hearts proceeding:

My bloud for your rude brawles doth lie a bleeding.

But Ile Amerce you with so strong a fine,

That you shall all repent the losse of mine.

It will be deafe to pleading and excuses,

Nor teares, nor prayers shall purchase our abuses.

Therefore vse none, let Romeo hence in hast,

Else when he is found, that houre is his last.

Beare hence his body, and attend our will:

Exeunt.Mercy not Murders, pardoning those that kill.

Enter Iuliet alone.

Iul.

Gallop apace, you fiery footed [steedes],

Towards Phæbus lodging, such a Wagoner

As Phaeton would whip you to the west,

And bring in Cloudie night immediately.

Spred thy close Curtaine Loue-performing night,

That run-awayes eyes may wincke, and Romeo

Leape to these armes, vntalkt of and vnseene,

Louers can see to doe their Amorous rights,

And by their owne Beauties: or if Loue be blind,

It best agrees with night: come ciuill night,

Thou sober suted Matron all in blacke,

And learne me how to loose a winning match,

Plaid for a paire of stainlesse Maidenhoods,

Hood my vnman’d blood bayting in my Cheekes,

With thy Blacke mantle, till strange Loue grow bold,

Thinke true Loue acted simple modestie:

Come night, come Romeo, come thou day in night,

For thou wilt lie vpon the wings of night

Whiter then new Snow vpon a Rauens backe:

Come gentle night, come louing blackebrow’d night.

Giue me my Romeo, and when I shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little starres,

And he will make the Face of heauen so fine,

That all the world will be in Loue with night,

And pay no worship to the Garish Sun.

O I haue bought the Mansion of a Loue,

But not possest it, and though I am sold,

Not yet enioy’d, so tedious is this day,

As is the night before some Festiuall,

To an impatient child that hath new robes

And may not weare them, O here comes my Nurse:

Enter Nurse with cords.

And she brings newes and euery tongue that speaks

But Romeos, name, speakes heauenly eloquence:

Now Nurse, what newes? what hast thou there?

The Cords that Romeo bid thee fetch?

Nur.

I, I, the Cords.

Iuli.

Ay me, what newes?

Why dost thou wring thy hands.

Nur.

A welady, hee’s dead, hee’s dead,

We are vndone Lady, we are vndone.

Alacke the day, hee’s gone, hee’s kil’d, he’s dead.

Iul.

Can heauen be so enuious?

Nur.

Romeo can,

Though heauen cannot. O Romeo, Romeo,

Who euer would haue thought it Romeo.

Iuli.

What diuell art thou,

That dost torment me thus?

This torture should be roar’d in dismall hell,

Hath Romeo slaine himselfe? say thou but I,

And that bare vowell I shall poyson more

Then the death-darting eye of Cockatrice,

I am not I, if there be such an I.

Or those eyes shot, that makes thee answere I:

If he be slaine say I, or if not, no.

Briefe, sounds, determine of my weale or wo.

Nur.

I saw the wound, I saw it with mine eyes,

God saue the marke, here on his manly brest,

A pitteous Coarse, a bloody piteous Coarse:

Pale, pale as ashes, all bedawb’d in blood,

All in gore blood, I sounded at the sight-

Iul.

O breake my heart,

Poore Banckrout breake at once,

To prison eyes, nere looke on libertie.

Vile earth to earth resigne, end motion here,

And thou and Romeo presse on heauie beere.

Nur.

O Tybalt, Tybalt, the best Friend I had:

O curteous Tybalt honest Gentleman,

That euer I should liue to see thee dead.

Iul.

What storme is this that blowes so contrarie?

Is Romeo slaughtred? and is Tybalt dead?

My dearest Cozen, and my dearer Lord:

Then dreadfull Trumpet sound the generall doome,

For who is liuing, if those two are gone?

Nur.

Tybalt is gone, and Romeo banished,

Romeo that kil’d him, he is banished.

Iul.

O God!

Did Rom’os hand shed Tybalts blood

It did, it did, alas the day, it did.

Nur.

O Serpent heart, hid with a flowring face.

Iul.

Did euer Dragon keepe so faire a Caue?

Beautifull Tyrant, fiend Angelicall:

Rauenous Doue-feather’d Rauen,

Woluish-rauening Lambe,

Dispised substance of Diuinest show:

Iust opposite to what thou iustly seem’st,

A dimne Saint, an Honourable Villaine:

O Nature! what had’st thou to doe in hell,

When thou did’st bower the spirit of a fiend

In mortall paradise of such sweet flesh?

Was euer booke containing such vile matter

So fairely bound? O that deceit should dwell

In such a gorgeous Pallace.

Nur.

There’s no trust, no faith, no honestie in men,

All periur’d, all forsworne, all naught, all dissemblers,

Ah where’s my man? giue me some Aqua-vitæ?

These griefes, these woes, these sorrowes make me old:

Shame come to Romeo.

Iul.

Blister’d be thy tongue

For such a wish, he was not borne to shame:

Vpon his brow shame is asham’d to sit;

For ’tis a throane where Honour may be Crown’d

Sole Monarch of the vniuersall earth:

O what a beast was I to chide him?

Nur.

Will you speake well of him,

That kil’d your Cozen?

Iul.

Shall I speake ill of him that is my husband?

Ah poore my Lord, what tongue shall smooth thy name,

When I thy three houres wife haue mangled it.

But wherefore Villaine did’st thou kill my Cozin?

That Villaine Cozin would haue kil’d my husband:

Backe foolish teares, backe to your natiue spring,

Your tributarie drops belong to woe,

Which you mistaking offer vp to ioy:

My husband liues that Tibalt would haue slaine,

And Tibalt dead that would haue slaine my husband:

All this is comfort, wherefore weepe I then?

Some words there was worser then Tybalts death

That murdered me, I would forget it feine,

But oh, it presses to my memory,

Like damned guilty deedes to sinners minds,

Tybalt is dead and Romeo banished:

That banished, that one word banished,

Hath slaine ten thousand Tibalts: Tibalts death

Was woe inough if it had ended there:

Or if sower woe delights in fellowship,

And needly will be rankt with other griefes,

Why followed not when she said Tibalts dead,

Thy Father or thy Mother, nay or both,

Which moderne lamentation might haue mou’d.

But which a rere-ward following Tybalts death

Romeo is banished to speake that word,

Is Father, Mother, Tybalt, Romeo, Iuliet,

All slaine, all dead: Romeo is banished,

There is no end, no limit, measure, bound,

In that words death, no words can that woe sound.

Where is my Father and my Mother Nurse?

Nur.

Weeping and wailing ouer Tybalts Coarse,

Will you go to them? I will bring you thither.

Iu.

Wash they his wounds with tears: mine shal be spent

When theirs are drie for Romeo’s banishment.

Take vp those Cordes, poore ropes you are beguil’d,

Both you and I for Romeo is exild:

He made you for a high-way to my bed,

But I a Maid, die Maiden widowed.

Come Cord, come Nurse, Ile to my wedding bed,

And death not Romeo, take my Maiden head.

Nur.

Hie to your Chamber, Ile find Romeo

To comfort you, I wot well where he is:

Harke ye your Romeo will be heere at night,

Ile to him, he is hid at Lawrence Cell.

Iul.

O find him, giue this Ring to my true Knight,

Exit.And bid him come, to take his last farewell.

Enter Frier and Romeo.

Fri.

Romeo come forth,

Come forth thou fearfull man,

Affliction is enamor’d of thy parts:

And thou art wedded to calamitie.

Rom.

Father what newes?

What is the Princes Doome?

What sorrow craues acquaintance at my hand,

That I yet know not?

Fri.

Too familiar

Is my deare Sonne with such sowre Company:

I bring thee tydings of the Princes Doome.

Rom.

What lesse then Doomesday,

Is the Princes Doome?

Fri.

A gentler iudgement vanisht from his lips,

Not bodies death, but bodies banishment.

Rom.

Ha, banishment? be mercifull, say death:

For exile hath more terror in his looke,

Much more then death: do not say banishment.

Fri.

Here from Verona art thou banished:

Be patient, for the world is broad and wide.

Rom.

There is no world without Verona walles,

But Purgatorie, Torture, hell it selfe:

Hence banished, is banisht from the world,

And worlds exile is death. Then banished,

Is death, mistearm’d, calling death banished,

Thou cut’st my head off with a golden Axe,

And smilest vpon the stroke that murders me.

Fri.

O deadly sin, O rude vnthankefulnesse!

Thy falt our Law calles death, but the kind Prince

Taking thy part, hath rusht aside the Law,

And turn’d that blacke word death, to banishment.

This is deare mercy, and thou seest it not.

Rom.

‘Tis Torture and not mercy, heauen is here

Where Iuliet liues, and euery Cat and Dog,

And little Mouse, euery vnworthy thing

Liue here in Heauen and may looke on her,

But Romeo may not. More Validitie,

More Honourable state, more Courtship liues

In carrion Flies, then Romeo: they may seaze

On the white wonder of deare Iuliets hand,

And steale immortall blessing from her lips,

Who euen in pure and vestall modestie

Still blush, as thinking their owne kisses sin.

This may Flies doe, when I from this must flie,

And saist thou yet, that exile is not death?

But Romeo may not, hee is banished.

Hadst thou no poyson mixt, no sharpe ground knife,

No sudden meane of death, though nere so meane,

But banished to kill me? Banished?

O Frier, the damned vse that word in hell:

Howlings attends it, how hast thou the hart

Being a Diuine, a Ghostly Confessor,

A Sin-Absoluer, and my Friend profest:

To mangle me with that word, banished?

Fri.

Then fond Mad man, heare me speake.

Rom.

O thou wilt speake againe of banishment.

Fri.

Ile giue thee Armour to keepe off that word,

Aduersities sweete milke, Philosophie,

To comfort thee, though thou art banished.

Rom.

Yet banished? hang vp Philosophie:

Vnlesse Philosohpie} can make a Iuliet,

Displant a Towne, reuerse a Princes Doome,

It helpes not, it preuailes not, talke no more.

Fri.

O then I see, that Mad men haue no eares.

Rom.

How should they,

When wisemen haue no eyes?

Fri.

Let me dispaire with thee of thy estate,

Rom.

Thou can’st not speake of that yu dost not feele,

Wert thou as young as Iuliet my Loue:

An houre but married, Tybalt murdered,

Doting like me, and like me banished,

Then mightest thou speake,

Then mightest thou teare thy hayre,

And fall vpon the ground as I doe now,

Taking the measure of an vnmade graue.

Enter Nurse, and knockes.

Frier.

Arise one knockes,

Good Romeo hide thy selfe.

Rom.

Not I,

Vnlesse the breath of Hartsicke groanes

Mist-like infold me from the search of eyes.

Knocke

Fri.

Harke how they knocke:

(Who’s there) Romeo arise,

Thou wilt be taken, stay a while, stand vp:

Knocke.

Run to my study: by and by, Gods will

What simplenesse is this: I come, I come.

Knocke

Who knocks so hard?

Whence come you? what’s your will?

Enter Nurse.

Nur.

Let me come in,

And you shall know my errand:

I come from Lady Iuliet.

Fri.

Welcome then.

Nur.

O holy Frier, O tell me holy Frier,

Where’s my Ladies Lord? where’s Romeo?

Fri.

There on the ground,

With his owne teares made drunke.

Nur.

O he is euen in my Mistresse case,

Iust in her case. O wofull simpathy:

Pittious predicament, euen so lies she,

Blubbring and weeping, weeping and blubbring,

Stand vp, stand vp, stand and you be a man,

For Iuliets sake, for her sake rise and stand:

Why should you fall into so deepe an O.

Rom.

Nurse.

Nur.

Ah sir, ah sir, deaths the end of all.

Rom.

Speak’st thou of Iuliet? how is it with her?

Doth not she thinke me an old Murtherer,

Now I haue stain’d the Childhood of our ioy,

With blood remoued, but little from her owne?

Where is she? and how doth she? and what sayes

My conceal’d Lady to our conceal’d Loue?

Nur.

Oh she sayes nothing sir, but weeps and weeps,

And now fals on her bed, and then starts vp,

And Tybalt calls, and then on Romeo cries,

And then downe falls againe.

Ro.

As if that name shot from the dead leuell of a Gun,

Did murder her, as that names cursed hand

Murdred her kinsman. Oh tell me Frier, tell me,

In what vile part of this Anatomie

Doth my name lodge? Tell me, that I may sacke

The hatefull Mansion.

Fri.

Hold thy desperate hand:

Art thou a man? thy forme cries out thou art:

Thy teares are womanish, thy wild acts denote

The vnreasonable Furie of a beast.

Vnseemely woman, in a seeming man,

And ill beseeming beast in seeming both,

Thou hast amaz’d me. By my holy order,

I thought thy disposition better temper’d.

Hast thou slaine Tybalt? wilt thou slay thy selfe?

And slay thy Lady, that in thy life lies,

By doing damned hate vpon thy selfe?