From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The history of email entails an evolving set of technologies and standards that culminated in the email systems in use today.

Computer-based messaging between users of the same system became possible following the advent of time-sharing in the early 1960s, with a notable implementation by MIT’s CTSS project in 1965. Informal methods of using shared files to pass messages were soon expanded into the first mail systems. Most developers of early mainframes and minicomputers developed similar, but generally incompatible, mail applications. Over time, a complex web of gateways and routing systems linked many of them. Some systems also supported a form of instant messaging, where sender and receiver needed to be online simultaneously.

In 1971 the first ARPANET network mail was sent, introducing the now-familiar address syntax with the ‘@’ symbol designating the user’s system address. Over a series of RFCs, conventions were refined for sending mail messages over the File Transfer Protocol. Several other email networks developed in the 1970s and expanded subsequently.

Proprietary electronic mail systems began to emerge in the 1970s and early 1980s. IBM developed a primitive in-house solution for office automation over the period 1970–1972, and replaced it with OFS (Office System), proving mail transfer between individuals, in 1974. This system developed into IBM Profs, which was available on request to customers before being released commercially in 1981. CompuServe began offering electronic mail designed for intraoffice memos in 1978. The development team for the Xerox Star began using electronic mail in the late 1970s. Development work on DEC’s ALL-IN-1 system began in 1977 and was released in 1982. Hewlett-Packard launched HPMAIL (later HP DeskManager) in 1982, which became the world’s largest selling email system.

The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) protocol was implemented on the ARPANET in 1983. LAN email systems emerged in the mid-1980s. For a time in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it seemed likely that either a proprietary commercial system or the X.400 email system, part of the Government Open Systems Interconnection Profile (GOSIP), would predominate. However, a combination of factors made the current Internet suite of SMTP, POP3 and IMAP email protocols the standard (see Protocol Wars).

During the 1980s and 1990s, use of email became common in business, government, universities, and defense/military industries. Starting with the advent of webmail (the web-era form of email) and email clients in the mid-1990s, use of email began to extend to the rest of the public. By the 2000s, email had gained ubiquitous status. The popularity of smartphones since the 2010s has enabled instant access to emails.

Precursors[edit]

The first electrical transmission of messages began in the 19th century in the form of the electrical telegraph, which started to replace earlier forms of telegraphy from the 1840s in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Telex became an operational teleprinter service in 1933, beginning in Germany and Europe, and after 1945 spread around the world.[1]

The AUTODIN military network in the United States, first operational in 1962, provided a message service between 1,350 terminals, handling 30 million messages per month, with an average message length of approximately 3,000 characters.[2] By 1968, AUTODIN linked more than 300 sites in several countries.

Terminology and usage[edit]

The term mail in the context of messages between computer users has been in use since the 1960s. In RFCs relating to the ARPANET, network mail was used since 1973.[3][4]

Historically, the term electronic mail is any electronic document transmission.[nb 1] For example, several writers in the early 1970s used the term to refer to fax document transmission.[5][6] The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has a first quotation for electronic mail in the modern context in 1975.[7] Electronic mail was widely discussed in the late 1970s, but was usually shortened simply to mail.[8] In September 1976, a Business Week article entitled When interoffice mail goes electronic remarked «In a sense, electronic mail is not new».[9]

The OED provides a June 1979 first usage for E-mail: “Postal Service pushes ahead with E-mail” in the journal Electronics.[7] No earlier usage has been found; although, the first usage of the term email may be lost.[10] CompuServe rebranded its electronic mail service as EMAIL in April 1981, which popularized the term.[8][9] The term computer mail was also used in the early 1980s.[11][12]

The June 1979 usage of E-mail referred to the United States Postal Service (USPS) project called Electronic Computer Originated Mail, which they abbreviated E-COM. USPS began looking into electronic mail in 1977 resulting in the E-COM proposal in September 1978. The service launched in 1982, allowing corporate customers to send electronic mail to a post office branch from where it was printed and delivered in the normal way. It operated until 1985.[13][14][15]

Host-based mail systems[edit]

With the introduction of MIT’s Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) in 1961,[16] for the first time multiple users could log into a central system[nb 2] from remote terminals, and store and share files on the central disk.[17] Informal methods of using such shared files to pass messages were soon developed and expanded into the first mail systems.

- 1962

- The 1440/1460 Administrative Terminal System was able to exchange messages between terminals.[18]

- 1965

- MIT’s CTSS «MAIL» command was proposed by Pat Crisman, Glenda Schroeder, and Louis Pouzin, then implemented by Tom Van Vleck and Noel Morris.[19] Each user’s messages would be added to a local file called «MAIL BOX», which would have a «private» mode so that only the owner could read or delete messages. The proposed uses of the system were for communication from CTSS to notify users that files had been backed up, discussion between authors of CTSS commands, and communication from command authors to the CTSS manual editor. Developers of other early systems subsequently developed similar mail applications.

- 1968

- ATS/360.[20][21]

- 1971

- SNDMSG, a local inter-user mail program developed by Ray Tomlinson, incorporating the experimental file transfer program, CPYNET, allowed the first networked electronic mail over the ARPANET.[22][23] The addresses contained the ‘@’ character as a separator between local part and host.[23]

- 1972

- The Unix mail program enabled users to write mails and send them to mailboxes of other Unix users.[24][25] Furthermore, it helped managing the mailbox of the current user.

- APL Mailbox, by Larry Breed of STSC, aimed at being a more robust mail software than a predecessor written in 1971.[26][27][28]

- IBM developed a primitive in-house system for office automation over the period 1970–1972.[29]: 321–323 [30]

- 1973

- 666 BOX, by Leslie Goldsmith of I. P. Sharp Associates, a reimplementation of APL Mailbox.[26]

- 1974

- August — The PLATO IV Notes on-line message board system was generalized to offer «personal notes».[2][31]

- October — IBM OFS (Office System), proving mail transfer between individuals, was first installed as a replacement for their earlier in-house office automation system.[29]: 327–332 [30]

- 1978

- CompuServe offered electronic mail, designed primarily for intraoffice memos, as part of their corporate Infoplex service.[32]

- Mail client written by Kurt Shoens for Unix and distributed with the Second Berkeley Software Distribution included support for aliases and distribution lists, forwarding, formatting messages, and accessing different mailboxes.[33] It used the Unix mail client to send messages between system users. The concept was extended to communicate remotely over the Berkeley Network.[34]

- Computerized Bulletin Board System (CBBS) was a public dial-up BBS.

- 1979

- September 24 — CompuServe launched a dialup service labelled MicroNET which offered electronic mail.[35]

- ARPANET delivermail, the predecessor of sendmail, was shipped with 4.0 and 4.1 BSD.

- MH Message Handling System developed at The RAND Corporation provided several tools for managing electronic mail on Unix.[36]

- 1980

- July — Minitel experimental service launched in France, enabled users to have a mail box. Introduced commercially throughout France in 1982.

- Electronic Mail, an in-house application developed for a HP1000 minicomputer by a high school student, Shiva Ayyadurai. He was engaged on an internship project since 1978 at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, under Leslie P. Michelson. The shortened name EMAIL was used to describe the program in 1981 and the copyright for the code was registered in the US on August 30, 1982.[37][38][39] Ayyadurai asserted a claim since 2010 to be the inventor of email, which is disputed.[8][9][40][41]

- Wang Laboratories introduced its Integrated Information Systems line, incorporating the ability to attach digitised voice messages.[42][43]

- 1981

- April 1 — CompuServe rebranded its electronic mail service as EMAIL. A US trademark application (USPTO SN:73432146) was filed on June 27, 1983, but abandoned in August 1984.[8][9][44]

- IBM PROFS, the predecessor of OfficeVision/VM, is released, incorporating a centralised virtual machine to manage mail transfer between individuals.[45][46] Before that it was a PRPQ (Programming Request for Price Quotation), an IBM administrative term for non-standard software offerings with unique features, support and pricing.[29]: 321 By this year it had 500 users.[29]: 340

- Xerox Star goes on sale, offering a commercial variant of the Xerox Alto’s multi-user virtual office, including computer mail.[12][47] The Star had been in development since 1977 and the development team relied heavily on the technologies they were working on, including electronic mail.[48][49][50]

- 1982

- April — HPMAIL by Hewlett-Packard, went on sale. Later developed into HP DeskManager, this became the world’s largest selling email system.[51]

- May — ALL-IN-1 by Digital Equipment Corporation, an office automation system including functionality in electronic messaging, was released.[52] Development work began in 1977.[53] In-house electronic mail was in use at DEC prior to the commercial release of ALL-IN-1.

- 1984

- FidoNet is released, creating a network of connected Email accepting, and forwarding Bulletin boards.

- Prestel Mailbox service launched, offering private messaging, on the UK Viewdata service.[54] The Duke of Edinburgh’s account would be hacked within months of launch; the resulting legal case helped to define computer misuse laws in the UK and around the world.[55]

- 1994

- Mar 9 — PTG MAIL-DAEMON, the first experimental Webmail services is made available at CERN, by Phillip Hallam-Baker.[56]

Email networks[edit]

The first electronic message was sent between these two adjacent PDP-10 computers at BBN Technologies in 1971, connected only through the ARPANET.

To facilitate electronic mail exchange between remote sites and with other organizations, telecommunication links, such as dialup modems or leased lines, provided means to transport email globally, creating local and global networks. This was challenging for a number of reasons, including the widely different email address formats in use.

- In 1971 the first message was sent between two computers on the ARPANET.[23] Through RFC 561, RFC 680, RFC 724, and finally 1977’s RFC 733, this became a standardized working system based on the File Transfer Protocol (FTP).

- PLATO IV was networked to individual terminals over leased data lines prior to the implementation of personal notes in 1974.[31]

- IBM VNET was deployed by 1975, using BSC to communicate among CP-67 and VM hosts running RSCS.

- Unix mail was networked by 1978’s UUCP,[57] which was also used for USENET newsgroup postings, with similar headers.

- BerkNet, the Berkeley Network, was written by Eric Schmidt in 1978 and included first in the Second Berkeley Software Distribution. It provided support for sending and receiving messages over serial communication links. The Unix mail tool was extended to send messages using Berknet.[34]

- The delivermail tool, written by Eric Allman in 1979 and 1980 (and shipped in 4BSD), provided support for routing mail over dissimilar networks, including Arpanet, UUCP, and BerkNet. (It also provided support for mail user aliases.)[58]

- The mail client included in 4BSD (1980) was extended to provide interoperability between a variety of mail systems.[59]

- BITNET (1981) provided electronic mail services for educational institutions. It was based on the IBM VNET email system.[60]

- 1983 – MCI Mail Operated by MCI Communications Corporation. This was the first commercial public email service to use the Internet. MCI Mail also allowed subscribers to send regular postal mail (overnight) to non-subscribers.[61]

- In 1984, IBM PCs running DOS could link with FidoNet for email and shared bulletin board posting.

- Several companies established electronic mail services in the United Kingdom during the 1970s and early 1980s, enabling subscribers to send email either internally within a company network or over telephone connections or data networks such as Packet Switch Stream.[62][63]

ARPANET mail[edit]

Experimental message transfers between separate computer systems began shortly after the creation of the ARPANET in 1969.[19] Ray Tomlinson, of BBN, sent the first message across the network in 1971, initiating the use of the «@» sign to separate the names of the user and the user’s machine.[64] He sent a message from one Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-10 computer to another PDP-10. The two machines were placed next to each other.[23][65] Tomlinson’s work was adopted across the ARPANET, which significantly increased network traffic.[66] Tomlinson has been called «the inventor of modern email».[67]

A «Mail Protocol» was proposed in RFC 196 in July 1971, and a more comprehensive approach in RFC 524 in June 1973, but these were not implemented.[68][69]

From SNDMSG to MSG[edit]

In the early 1970s, Ray Tomlinson updated an existing utility called SNDMSG so that it could copy messages (as files) over the network. Lawrence Roberts, the project manager for the ARPANET development, took the idea of READMAIL, which dumped all «recent» messages onto the user’s terminal, and wrote a program for TENEX in TECO macros called RD, which permitted access to individual messages.[70] Barry Wessler then updated RD and called it NRD.[71]

Marty Yonke rewrote NRD to include reading, access to SNDMSG for sending, and a help system, and called the utility WRD, which was later known as BANANARD. John Vittal then updated this version to include three important commands: Move (combined save/delete command), Answer (determined to whom a reply should be sent) and Forward (sent a message to a person who was not already a recipient). The system was called MSG. With inclusion of these features, MSG is considered to be the first integrated modern electronic mail program, from which many other applications have descended.[70]

FTP mail[edit]

ARPANET defined conventions from 1973 for dissimilar computers to exchange mail using the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) over a homogeneous network. Two FTP commands, MAIL and MLFL, permitted an FTP user process to deliver a file or string of text to an FTP server process, designating it as mail to be made available to a user, identified by a local name, in its host.

The use of the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) for «network mail» was proposed in RFC 469 in March 1973.[72] Through RFC 561, RFC 680, RFC 724, and finally RFC 733 in November 1977, a standardized framework was developed for «electronic mail» using FTP mail servers on the ARPANET.[11]

Delivermail was introduced in 1979 as a mail transport agent, i.e. email server. It used the FTP protocol to transmit electronic mail messages to the recipient.[73]

Initially, addresses were of the form, username@hostname. Addresses were extended to username@host.domain by RFC 805 in February 1982.

Attempts at interoperability[edit]

Early interoperability among independent systems included:

- The Coloured Book protocols ran on academic networks in the United Kingdom from 1975 until 1992.[62][74][75][76]

- UUCP implementations for Unix systems, initially released in 1979, and later for other operating systems, that only had dial-up communications available.

- CSNET, which began operation in 1981, initially used a purpose-built dial-up protocol, called Phonenet, to provide mail-relay services for non-ARPANET hosts.

- The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) protocol was implemented in 1983. It was first proposed by Jon Postel and Suzanne Sluizer in September 1980.

- X.400, published in 1984, was promoted by major vendors, and mandated for government use under GOSIP, but abandoned by all but a few in favor of Internet protocol suite’s SMTP by the mid-1990s (see Protocol Wars).[62][77]

- Soft-Switch released its eponymous email gateway product in 1984, acquired by Lotus Software ten years later.[78]

- Message Handling System (MHS) protocol developed in 1986. Developed by Action Technologies, this was later bought and promoted by Novell.[79][80][81] However they abandoned it after purchasing the non-MHS WordPerfect Office—which they renamed GroupWise.

- HP OpenMail, initially designed in 1987, was known for its ability to interconnect several other APIs and protocols, including MAPI, cc:Mail, SMTP/MIME, and X.400.

LAN email systems[edit]

In the early 1980s, networked personal computers on LANs became increasingly important. Server-based systems similar to the earlier mainframe systems were developed. Examples include:

- cc:Mail

- LANtastic

- Banyan VINES (1984)

- Microsoft Mail (1988)

- WordPerfect Office (1988), later rebranded Novell GroupWise

- Lotus Notes (1989)

Eventually these systems could link different organizations as long as each organization ran the same email system and proprietary protocol. Various vendors supplied gateway software to link these incompatible systems.

Internet email[edit]

SMTP[edit]

In September 1980, Jon Postel and Suzanne Sluizer published RFC 772 which proposed the Mail Transfer Protocol to enable servers to transmit «computer mail» on the ARPANET as a replacement for FTP. RFC 780 of May 1981 removed all references to FTP. In November 1981, Postel published RFC 788 describing the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) protocol, which was updated by RFC 821 in August 1982.

ARPANET switched to TCP/IP in 1983 and the Internet grew rapidly thereafter (see Protocol Wars). SMTP continued to be used on the Internet.

A new mail transfer agent based on SMTP, Sendmail, was introduced in 1983.

After the introduction of the Domain Name System (DNS) in 1985, mail routing was updated in January 1986 by RFC 974.

As the influence of the ARPANET spread across academic communities, gateways were developed to pass mail to and from other networks such as CSNET, JANET, BITNET, X.400, and FidoNet. This often involved addresses such as:

hubhost!middlehost!edgehost!user@uucpgateway.somedomain.example.com

which routes mail to a user with a «bang path» address at a UUCP host.

POP and IMAP[edit]

The Internet community developed two further standards, the Post Office Protocol (POP) and the Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP), in 1984 and 1988 respectively. POP and IMAP enabled connections with remote e-mail servers that contained users’ mailboxes.

Email clients[edit]

During the 1980s and 1990s, use of email became common in business, government, universities, and defense/military industries. Starting with the advent of webmail (the web-era form of email) and email clients in the mid-1990s, use of email began to extend to the rest of the public. By the 2000s, email had gained ubiquitous status. The popularity of smartphones since the 2010s has enabled instant access to emails.

Mail servers[edit]

Many providers of mail server software emerged in the 1980s with various features.

Notable first uses of email[edit]

- Ray Tomlinson is generally recognized as sending the first electronic mail, between two different computers on the ARPANET, in 1971.[82][83][84]

- Sylvia Wilbur, who worked for Peter Kirstein at University College London, was «probably one of the first people in [the United Kingdom] ever to send an email [over the ARPANET], back in 1974».[85][86]

- Queen Elizabeth II sent the first electronic mail from a head of state over the ARPANET from the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment in England on March 26, 1976.[87][88]

- Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign became the first to use electronic mail for internal communications in the autumn of 1976.[27][28][89]

- The first UUCP emails from the U.S. arrived in the UK in 1979 and UUCP email between the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark started in 1980, becoming a regular service via EUnet in 1982, which expanded coverage to Sweden and later France, Germany, Switzerland and other countries in Europe.[90][91]

- IBM PROFS email was used by the U.S. National Security Council under President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.[45][92]

- The first Internet email sent to Germany via CSNET was from Laura Breeden to Michael Rotert and Werner Zorn as a carbon copy at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology on August 3, 1984.[93][94]

- The first email sent from outer space was August 9, 1991, Space Shuttle mission STS-43.[95]

- Bill Clinton was the first U.S. president to use Internet email in the 1990s, including a reply to an email from the prime minister of Sweden in 1994.[96][97][98][99]

See also[edit]

- History of email spam

- History of email marketing

- History of Gmail

Notes[edit]

- ^ Separate to the development of electronic mail services, the French word émail primarily referred to vitreous enamel or sometimes ceramic glaze. A rare term, it was mainly used by art historians and medievalists.[citation needed]

- ^ an IBM 7094

References[edit]

- ^

Roemisch, Rudolf (1978). «Siemens EDS System in Service in Europe and Overseas». Siemens Review. Siemens-Schuckertwerke AG. 45 (4): 176. Retrieved 2016-02-04.The inauguration of the first telex service in the world in Germany in 1933 was soon followed by the development of similar networks in several more European countries. However, telex did not enjoy significant and worldwide growth until after 1945. Thanks to the great advantages of the new telex service, above all in overcoming time differences and language problems, telex networks were introduced in quick succession in all parts of the world.

- ^ a b National Research Council (1976). «Chapter IV: Systems». Electronic Message Systems for the U.S. Postal Service. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 27–35. doi:10.17226/19976. ISBN 978-0-309-33501-0.

- ^ Network Mail Meeting Summary. 8 March 1973. doi:10.17487/RFC0469. RFC 469.

- ^ Standardizing Network Mail Headers. 5 September 1973. doi:10.17487/RFC0561. RFC 561.

- ^ Brown, Ron (October 26, 1972). «Fax invades the mail market». New Scientist. Vol. 56, no. 817. London, England: New Scientist Ltd. pp. 218–221. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016.

- ^ Luckett, Herbert P. (March 1973). «What’s News: Electronic-mail delivery gets started». Popular Science. Vol. 202, no. 3. Harlan, Iowa: Bonnier Corporation. p. 85. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ a b «Appeals: email». Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ a b c d «Did V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai Invent Email? | SIGCIS». www.sigcis.org. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ a b c d Mike Masnick (May 22, 2019). «Laying Out All The Evidence: Shiva Ayyadurai Did Not Invent Email». Techdirt. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ «Why the first use of the word ‘e-mail’ may be lost forever». Washington Post. July 28, 2015. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ a b Standard for the Format of ARPA Network Text Messages. 21 November 1977. doi:10.17487/RFC0733. RFC 733.

- ^ a b Brotz, Douglas K. (May 1981). «Laurel Manual» (PDF). Xerox.

- ^ «The Last Dinosaur: The U.S. Postal Service». Cato Institute. 1985-02-12. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ USPS Historian (July 2008). «E-COM, Electronic Computer Originated Mail» (PDF).

- ^ «The Post Office Almost Delivered Your First E-Mail». Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ Roy J. Daigle, Ph. D. «CTSS, Compatible Time-Sharing System». Milestones in Computer Development. Archived from the original on October 29, 2006. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ^ Tom Van Vleck. «The IBM 7094 and CTSS». Multicians.org. Retrieved September 10, 2004.

- ^ 1440/1460 Administrative Terminal System (1440-CX-07X and 1460-CX-08X) Application Description (PDF), Second Edition, IBM, p. 10, H20-0129-1

- ^ a b Tom Van Vleck. «The History of Electronic Mail».

- ^ System/360 Administrative Terminal System DOS (ATS/DOS) Program Description Manual, IBM, H20-0508

- ^ System/360 Administrative Terminal System-OS (ATS/OS) Application Description Manual, IBM, H20-0297

- ^ Elliott, Geoffrey (2004). Global business information technology : an integrated systems approach. Financial Times Prentice Hall. p. 425. ISBN 9780321270122.

- ^ a b c d Tomlinson, Ray. «The First Network Email». Openmap.bbn.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-09. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ «Version 3 Unix mail(1) manual page from 10/25/1972». Minnie.tuhs.org. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ «Version 6 Unix mail(1) manual page from 2/21/1975». Minnie.tuhs.org. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ a b Leslie Goldsmith. «Leslie Goldsmith’s story of the Mailbox». APL Quotations and Anecdotes.

- ^ a b «Home > Communications > The Internet > History of the internet > Internet in its infancy». actewagl.com.au. Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ a b Catherine Lathwell, ed. (c. 1979). The STSC Story: It’s About Time. Scientific Time Sharing Corporation. 7:08 minutes in. Retrieved 2017-01-06. Promotional video for Scientific Time Sharing Corporation, which features President Jimmy Carter’s press secretary Jody Powell explaining how the company’s «APLplus Mailbox» Message Processing System enabled the 1976 Carter presidential campaign to easily move information around the country to coordinate the campaign.

- ^ a b c d Gardner, P. C. (1981). «A system for the automated office environment». IBM Systems Journal. 20 (3): 321–345. doi:10.1147/sj.203.0321. ISSN 0018-8670.

- ^ a b «The History of Electronic Mail». multicians.org. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

IBM CP/CMS had electronic mail as early as 1966, and was widely used within IBM in the 1970s. Eventually this facility evolved into the PROFS product in the 1980s.

- ^ a b David Wooley (January 10, 1994). «PLATO: The Emergence of an Online Community». Personal Notes.

- ^ Connie Winkler (October 22, 1979). «CompuServe pins hopes on MicroNET, InfoPlex». Computerworld. Vol. 13, no. 42. p. 69.

- ^ The Mail Reference Manual, Kurt Shoens, University of California, Berkeley, 1979.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Eric (May 1979). An Introduction to the Berkeley Network (PDF) (Technical report). Computer Science Division, University of California at Berkeley.

This document describes the use of a network between a number of UNIX machines on the Berkeley campus. This network can execute commands on other machines, including file transfers, sending and receiving mail, remote printing, and shell-scripts.

- ^ Dylan Tweney (September 24, 1979). «Sept. 24, 1979: First Online Service for Consumers Debuts». Wired.

- ^ A Mail Handling System, Bruce Borden, The RAND Corporation, 1979.

- ^ Aamoth, Doug (2011-11-15). «The Man Who Invented Email». Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ Kolawole, Emi (2012-02-17). «Smithsonian acquires documents from inventor of ‘EMAIL’ program». Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ «Statement from the National Museum of American History: Collection of Materials from V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai» (Press release). National Museum of American History. 23 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Pexton, Patrick B. (2012-03-01). «Origins of e-mail: My mea culpa». Washington Post. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ Crocker, David (20 March 2012). «A history of e-mail: Collaboration, innovation and the birth of a system». Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ Hoard, Bruce (1982-03-29). «Voice Seen Top Communications Form». Computerworld. Vol. 16, no. 13. IDG Enterprise.

- ^ Haigh, Thomas (2006). «Remembering the Office of the Future: The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation» (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 28 (4): 6–31. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2006.70. S2CID 11270328.

- ^ «Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) — 73432146[SN]». tmsearch.uspto.gov. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ a b «IBM100 — The Networked Business Place». IBM. 2020-08-02. Archived from the original on 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ^ Lewis, Robin; Dart, Michael (2014-08-12). The New Rules of Retail: Competing in the World’s Toughest Marketplace. St. Martin’s Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-137-48089-7.

- ^ «Xerox 8010 Star Information System». National Museum of American History. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ Ollig, Mark (October 31, 2011). «They could have owned the computer industry». Herald Journal. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ «Tech before its time: Xerox’s shooting Star computer». New Scientist. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ «The Xerox Star». toastytech.com. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ «HP Computer Museum».

- ^ «1982 Timeline». DIGITAL Computing Timeline. 1998-01-30. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ «ALL-IN-1». DIGITAL Computing Timeline. 1998-01-30.

- ^ «How to Send an Email in 1984». www.vice.com. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ «Archive of historic BT ’email’ hack preserved». BBC News. 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ Hallam-Baker, Phillip (March 9, 1994). «Announcing alpha test of PTG MAIL-DAEMON server». Google Groups. Newsgroup: comp.archives. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ «Version 7 Unix manual: «UUCP Implementation Description» by D. A. Nowitz, and «A Dial-Up Network of UNIX Systems» by D. A. Nowitz and M. E. Lesk». Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ Setting up the Fourth Berkeley Software Tape, William N. Joy, Ozalp Babaoglu, Keith Sklower, University of California, Berkeley, 1980.

- ^ Mail(1), UNIX Programmer’s Manual, 4BSD, University of California, Berkeley, 1980.

- ^ «BITNET History». livinginternet.com.

- ^ «MCI Mail», MCI Mail

- ^ a b c Rutter, Dorian (2005). From Diversity to Convergence: British Computer Networks and the Internet, 1970-1995 (PDF) (Computer Science thesis). The University of Warwick.

- ^ Barry Fox (1985-10-17). «The electronic mail is getting through». New Scientist. Reed Business Information. pp. 61–64.

- ^ Lievrouw, L. A. (2006). Lievrouw, L. A.; Livingstone, S. M. (eds.). Handbook of New Media: Student Edition. SAGE. p. 253. ISBN 1412918731. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Wave New World,Time Magazine, October 19, 2009, p.48

- ^ Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 106–111. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5. OCLC 44962566.

- ^ «Ray Tomlinson, Inventor Of Modern Email, Dies». NPR.org. 6 March 2016.

- ^ Tom Van Vleck. «The History of Electronic Mail».

It is not clear this protocol was ever implemented

- ^ Crocker, David H. (December 1977). Framework and Functions of the «MS» Personal Message System (PDF) (Report). The RAND Corporation. R-2134-ARPA.

- ^ a b «Email History». Livinginternet.com. 1996-05-13. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ^ *Partridge, Craig (April–June 2008). «The Technical Development of Internet Email» (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. Berlin: IEEE Computer Society. 30 (2): 3–29. doi:10.1109/mahc.2008.32. S2CID 206442868. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-12.

- ^ Network Mail Meeting Summary. doi:10.17487/RFC0469. RFC 469.

- ^ Bryan Costales (2002). «History». Sendmail (3rd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- ^ Davies, Howard; Bressan, Beatrice (2010-04-26). A History of International Research Networking: The People who Made it Happen. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-3-527-32710-2.

- ^ Earnshaw, Rae; Vince, John (2007-09-20). Digital Convergence – Libraries of the Future. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-84628-903-3.

- ^ «IP». FLAGSHIP, Central Computing Department Newsletter (12). January 1991.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin; Garcia-Swartz, Daniel D (2013). «The History of the Internet: The Missing Narratives». Journal of Information Technology. 28 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1057/jit.2013.4. ISSN 0268-3962.

- ^ Glenn Rifkin (1994-06-17). «Lotus Agrees to Acquire Softswitch». The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ Daniel Blum (1994-09-19). «Delivering the Enterprise Message». Network World.

- ^ Mark Gibbs (1994-03-07). «Hot on the LAN». Network World. Archived from the original on 2014-03-30.

- ^ «MHS: Correct Addressing format to DaVinci Email via MHS». Microsoft Support Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ^ «Official Biography: Raymond Tomlinson | Internet Hall of Fame». www.internethalloffame.org. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ «Email inventor on his legacy». BBC News. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ «Ray Tomlinson, creator of modern email, dies». www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Abbate, Janet (April 2001), «Silvia Wilbur», IEEE History Center Interview #634, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

- ^ Kirstein, Peter (January–March 1999). «Early experiences with the Arpanet and Internet in the United Kingdom». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. 21 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1109/85.759368.

- ^ Metz, Cade (2012-12-25). «How the Queen of England Beat Everyone to the Internet». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ Left, Sarah (2002-03-13). «Email timeline». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ Franke-Ruta, Garance (2013-12-09). «When Jimmy Carter Was the Computer-Driven Candidate». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ Houlder, Peter (19 January 2007). «Starting the Commercial Internet in the UK» (PDF). 6th UK Network Operators’ Forum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- ^ Reid, Jim (3 April 2007). «Networking in UK Academia ~25 Years Ago» (PDF). 7th UK Network Operators’ Forum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- ^ «National Security Archive/White House E-Mail». nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ «Historic First Email From U.S. to Germany Arrives in 1984 | Internet Hall of Fame». www.internethalloffame.org. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- ^ «25 Jahre E-Mail in Deutschland — Und es hat «Pling!» gemacht» [25 years of email in Germany — and it went «Pling!»]. Der Spiegel (in German). 2009-08-01.

- ^ «Macintosh Portable: Used in Space Shuttle». support.apple.com. Feb 19, 2012. Archived from the original on Jun 19, 2018. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ LaFrance, Adrienne (2015-03-12). «The Truth About Bill Clinton’s Emails». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ «First president with regular email access». Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ Sandre, Andreas (2017-11-07). «What’s the first ever presidential email?». Medium. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ Bildt, Carl (13 December 2016). «I sent the first email between heads of state—but the real revolution of connectivity is still to come». Quartz. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

External links[edit]

Look up email or outbox in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- IANA’s list of standard header fields

- The History of Email is Dave Crocker’s attempt at capturing the sequence of ‘significant’ occurrences in the evolution of email; a collaborative effort that also cites this page.

- The History of Electronic Mail is a personal memoir by the implementer of an early email system

- A Look at the Origins of Network Email is a short, yet vivid recap of the key historical facts

- Business E-Mail Compromise — An Emerging Global Threat, FBI

Somewhere out there, during the early days of networked communication, somebody probably complained about a lengthy term and decided to do something about it. At that point, the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary are guessing, “electronic mail” became “email” (or “e-mail”), and a cornucopia of e-prefixed words would follow over the next few decades.

Thing is, for years, the OED editors have been asking the public to help them find documentation of the first time “email” was used — and they still haven’t had any luck.

The OED recently renewed its plea for help in tracking down documentation of the first time someone wrote “email” or “e-mail” instead of “electronic mail.” The appeal has been online for three years — and the word has been an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary since 1989 — but the OED still doesn’t have a verifiable instance of the first time someone used it.

“You’re tempted to think that someone said in some message board, ‘I’m tired of typing out electronic mail. Can we just call it email?’ ” Katherine Martin, the head of U.S. dictionaries for Oxford University Press, told The Washington Post. “Something that’s truly unique like this, you expect there to be a single person.”

Right now, the earliest use the editors can find dates to 1979. And that citation comes from a headline in a scientific journal:

1979 Electronics 7 June 63 (heading) Postal Service pushes ahead with E-mail.

“Sometimes, you think, we haven’t had any results because there’s nothing earlier out there,” Martin said. “For email, there are a couple reasons that seem important to continue to look at it.”

For one thing, Martin explained, the citation simply “doesn’t look like a coinage.” To the 1979 readers of Electronics, the idea that “e-” meant “electronic” would be a large leap to make. The prefix simply didn’t exist before email, Martin said, and it seems very unlikely that a journal would decide to go ahead and put “e-mail” in a headline if readers weren’t already at least somewhat familiar with the term.

“It’s not something you’d expect people to understand if it wasn’t already in use,” Martin said.

These OED appeals, in some form, date back to the 19th century origins of the dictionary. The earliest printed appeals asked the public to read specific books and look for quotations for any notable words. Soon, the dictionary’s first editor, James Murray, tweaked his strategy: He sent out lists of words for which he needed quotations.

“We will from time to time print and circulate among our existing Readers lists of the verbal desiderata discovered in the course of arranging and working up the materials already in hand,” reads an appeal pamphlet from 1879.

The pamphlet explains that the dictionary’s editors were looking for quotations for three reasons: First, some words don’t have any quotations, or only one, and the editors simply need more; second, some words need more current quotations; and third, as is still the case with many of today’s online appeals, the editors need to find earlier — ideally the earliest — use of a particular word. The process of finding that first quotation is called “antedating” by lexicographers.

The appeals have continued on and off since the 19th century. Before going online, Martin said, editors used paper newsletters to publicize their latest appeals.

Since 2012, the OED’s editors have been appealing online for help tracking down early quotations of words, old and new, when editors don’t think they have the full story of a word’s origins and usage. Basically, the editors ask readers to leave comments— available for the public to read — directing editors toward any leads or quotations that might fit the bill. The editors respond to those requests as they come in, also in the comments, and when the word is successfully antedated, the appeal is closed.

Many of these appeals have been successful, such as the ones for “bromance” and “FAQ” and the use of “the Company” to refer to the CIA.

The editors also found out something very surprising about “skive,” a World War I British slang word meaning to evade duty. Before posting the online appeal, the editors assumed the word came from conversations between British and French troops, since the French word “esquiver” has a similar meaning. The earliest citation supporting that usage dates to 1919.

However, one reader found a citation from 1918 — in a student publication from the University of Notre Dame in South Bend. Yes, in America. That discovery “raises more questions than it answers,” Martin admits. But it does demonstrate just how helpful these online appeals can be. Sometimes, readers will look in places the editors haven’t even considered.

So if the online appeals process has been a pretty interesting success overall for the OED, why is “email” still languishing?

Often, for words coined in the age of networked communications, editors and interested readers know that the first usage is somewhere out there, on a publicly accessible message board, or in a tweet, or a blog post. But for “email,” the editors need to access a different sort of networked world. “It’s a lot harder for email; it’s so early in the history of networked computing conversations,” Martin said.

The appeal has generated a few responses, Martin added, but nothing verifiable yet. It’s likely that the antedating they’re looking for lies in archived messages held by someone who was involved in the creation or the early implementation of what we’d recognize as emails today. If that’s the case, the editors are hoping one of those people will hear that the OED is looking for them and respond. “In a way, that’s what the appeal is intended to do: To request that any of those people who were involved in those things step forward,” Martin said.

MORE READING:

The Oxford English Dictionary editors are asking the public to help them find documentation of the first time «email» was used. Photo / Richard Robinson

Somewhere out there, during the early days of networked communication, somebody probably complained about a lengthy term and decided to do something about it. At that point, the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary are guessing, «electronic mail» became «email» (or «e-mail»), and a cornucopia of e-prefixed words would follow over the next few decades.

Thing is, for years, the OED editors have been asking the public to help them find documentation of the first time «email» was used — and they still haven’t had any luck.

Read also:

• The guy trying to turn emoji into a legitimate, usable language

• Tweet, wingsuit, burqini — newest dictionary additions

The OED recently renewed its plea for help in tracking down documentation of the first time someone wrote «email» or «e-mail» instead of «electronic mail.» The appeal has been online for three years — and the word has been an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary since 1989 — but the OED still doesn’t have a verifiable instance of the first time someone used it.

«You’re tempted to think that someone said in some message board, ‘I’m tired of typing out electronic mail. Can we just call it email?’ » Katherine Martin, the head of US dictionaries for Oxford University Press, told The Washington Post. «Something that’s truly unique like this, you expect there to be a single person.»

1979 headline

Right now, the earliest use the editors can find dates to 1979. And that citation comes from a headline in a scientific journal:

«1979 Electronics 7 June 63 (heading) Postal Service pushes ahead with E-mail.»

«Sometimes, you think, we haven’t had any results because there’s nothing earlier out there,» Martin said. «For email, there are a couple reasons that seem important to continue to look at it.»

For one thing, Martin explained, the citation simply «doesn’t look like a coinage.» To the 1979 readers of Electronics, the idea that «e-» meant «electronic» would be a large leap to make. The prefix simply didn’t exist before email, Martin said, and it seems very unlikely that a journal would decide to go ahead and put «e-mail» in a headline if readers weren’t already at least somewhat familiar with the term.

«It’s not something you’d expect people to understand if it wasn’t already in use,» Martin said.

Public appeals

These OED appeals, in some form, date back to the 19th century origins of the dictionary. The earliest printed appeals asked the public to read specific books and look for quotations for any notable words. Soon, the dictionary’s first editor, James Murray, tweaked his strategy: He sent out lists of words for which he needed quotations.

«We will from time to time print and circulate among our existing Readers lists of the verbal desiderata discovered in the course of arranging and working up the materials already in hand,» reads an appeal pamphlet from 1879.

The pamphlet explains that the dictionary’s editors were looking for quotations for three reasons: First, some words don’t have any quotations, or only one, and the editors simply need more; second, some words need more current quotations; and third, as is still the case with many of today’s online appeals, the editors need to find earlier — ideally the earliest — use of a particular word. The process of finding that first quotation is called «antedating» by lexicographers.

The appeals have continued on and off since the 19th century. Before going online, Martin said, editors used paper newsletters to publicise their latest appeals.

‘Bromance’

Since 2012, the OED’s editors have been appealing online for help tracking down early quotations of words, old and new, when editors don’t think they have the full story of a word’s origins and usage. Basically, the editors ask readers to leave comments — available for the public to read — directing editors toward any leads or quotations that might fit the bill. The editors respond to those requests as they come in, also in the comments, and when the word is successfully antedated, the appeal is closed.

Many of these appeals have been successful, such as the ones for «bromance» and «FAQ» and the use of «the Company» to refer to the CIA.

The editors also found out something very surprising about «skive,» a World War I British slang word meaning to evade duty. Before posting the online appeal, the editors assumed the word came from conversations between British and French troops, since the French word «esquiver» has a similar meaning. The earliest citation supporting that usage dates to 1919.

However, one reader found a citation from 1918 — in a student publication from the University of Notre Dame in South Bend. Yes, in America. That discovery «raises more questions than it answers,» Martin admits. But it does demonstrate just how helpful these online appeals can be. Sometimes, readers will look in places the editors haven’t even considered.

Networked world

So if the online appeals process has been a pretty interesting success overall for the OED, why is «email» still languishing?

Often, for words coined in the age of networked communications, editors and interested readers know that the first usage is somewhere out there, on a publicly accessible message board, or in a tweet, or a blog post. But for «email,» the editors need to access a different sort of networked world. «It’s a lot harder for email; it’s so early in the history of networked computing conversations,» Martin said.

The appeal has generated a few responses, Martin added, but nothing verifiable yet. It’s likely that the antedating they’re looking for lies in archived messages held by someone who was involved in the creation or the early implementation of what we’d recognise as emails today. If that’s the case, the editors are hoping one of those people will hear that the OED is looking for them and respond.

«In a way, that’s what the appeal is intended to do: To request that any of those people who were involved in those things step forward,» Martin said.

Ray Tomlinson, the man who literally put the “@” in email, died on Saturday, but his invention, which allowed electronic messages to spread across the internet and fill our lives and our inboxes on a daily basis, will live on.

Here is a brief look at what Tomlinson started and the evolution of email through the last half-century.

The first electronic message — 1965

The very first version of what would become known as email was invented in 1965 at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as part of the university’s Compatible Time-Sharing System, which allowed users to share files and messages on a central disk, logging in from remote terminals.

Tomlinson and the @ — 1971

American computer programmer Tomlinson arguably conceived the method of sending email between different computers across the forerunner to the internet, Arpanet, at the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa), introducing the “@” sign to allow messages to be targeted at certain users on certain machines.

Emails become a standard — 1973

The first email standard was proposed in 1973 at Darpa and finalised within Arpanet in 1977, including common things such as the to and from fields, and the ability to forward emails to others who were not initially a recipient.

The Queen sends her first email — 1976

Queen Elizabeth II sends an email on Arpanet, becoming the first head of state to do so.

Eric Schmidt designs BerkNet — 1978

Eric Schmidt, who would later lead Google and oversee the introduction of Gmail, wrote Berkley Network as part of his master’s thesis in 1978, which was an early intranet service offering messaging over serial connections.

EMAIL program developed — 1979

At the age of 14, Shiva Ayyadurai writes a program called EMAIL for the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, which sent electronic messages within the university, later copyrighting the term in 1982. Whether or not this is the first use of the word email is up for debate.

Microsoft Mail arrives — 1988

The first version of Microsoft Mail was released in 1988 for Mac OS, allowing users of Apple’s AppleTalk Networks to send messages to each other. In 1991, a second version was released for other platforms including DOS and Windows, which laid the groundwork for Microsoft’s later Outlook and Exchange email systems.

CompuServe starts internet-based email service — 1989

CompuServe became the first online service to offer internet connectivity via dial-up phone connections, and its proprietary email service allowed other internet users to send emails to each other.

Lotus Notes launched — 1989

The first version Lotus Notes was released in 1989 by Lotus Development Corporation, which was bought by IBM in 1995.

The start of spam — 1990

The rise of spam can be charted back to the very early days of Arpanet, but it wasn’t until the early 1990s that it hit users across the internet, when it was aimed at message boards and later email addresses.

April 1994 is the first recorded business practice of spam from two lawyers from Phoenix, Laurence Carter and Martha Siegel, who ended up writing a book on it.

The attachment — 1992

The attachment was born when the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (Mime) protocol was released, which includes the ability to attach things that are not just text to emails. And so begins the painful exercise of trying to delete emails to make space after someone sends you a massive attachment in the days of limited inbox space.

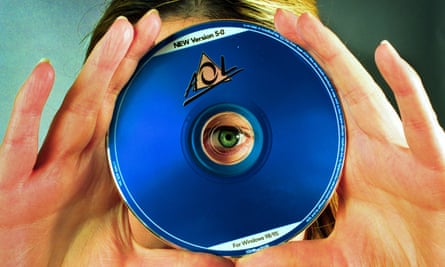

Outlook and Aol — 1993

The first version of Microsoft’s Outlook was released in 1993 as part of Exchange Server 5.5, while at the same time US internet service providers AOL and Delphi connected their email systems, paving the way for modern, overloaded email systems we struggle with today.

Hotmail launches — 1996

Before Microsoft bought it for $400m, 1996 saw the launch of one of the first popular webmail email services called HoTMaiL developed by Sabeer Bhatia and Jack Smith. It was one of the first email services not tied to a particular ISP and adopted new HTML-based email formatting – hence the stylising of the brand name.

It was bought by Microsoft in 1997, rebranded MSN Hotmail, then Windows Live Hotmail and replaced by Outlook.com in 2013.

Yahoo Mail follows — 1997

Yahoo Mail was launched the year after Hotmail, which was gaining users by the thousands, and was based on internet company Four11’s Rocketmail, which was bought as part of Yahoo’s acquisition of the company.

You’ve Got Mail, and so has everyone else — 1998

Email was cemented in the public consciousness with the notorious “you’ve got mail” sound of email arriving for AOL users, which formed the cornerstone of the 1998 Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan romantic comedy, You’ve Got Mail.

By the late 1990s spam was becoming a real problem – inducted to the Oxford English Dictionary in 1998 – as more and more marketers jumped on the practically zero-cost outreach proposition and inundated our inboxes.

In 2002, the European Union released its Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications, which included a section on spam that made it illegal to send unsolicited communications for direct marketing purposes without prior consent of the recipient.

The US passed similar laws in 2004, although neither have been particularly effective at reducing the load.

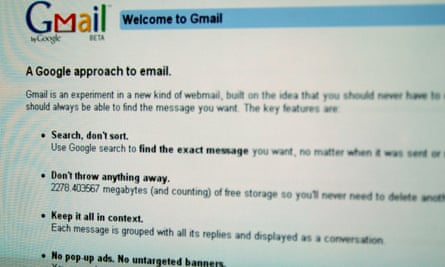

Gmail launches — 2004

Google’s popular email service, Gmail, started life as an internal mail system for Google employees, developed by Paul Buchheit in 2001. It wasn’t unveiled to the public until a limited, invite-only beta release in 2004. It was made publicly available in 2007 and dropped its “beta” status in 2009.

Fighting back against spam — 2005

The first email standard to attempt to fight the deluge of spam by verifying senders was published after a five-year development. Sender Policy Framework was then implemented by a variety of anti-spam programs. A standard of authentication to attempt to prevent email spoofing and phishing was also released called DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM).

Email goes mobile for casual users — 2007

Apple’s first iPhone was released in 2007, which began to introduce mobile email to the consumer masses. Until that point pre-capacitive consumer smartphones typically had limited email support, while RIM’s BlackBerry had brought the burden of work email to employee palms starting in 2003.

Buried in email — 2015

From humble internal communications beginnings, email now dominates a vast proportion of everyday life. An estimated 4.4bn email addresses are in use worldwide with 205bn emails sent per day in 2015, according to data from market research firm Radicati Group.

That number is set to increase to over 246bn emails a day by the end of 2019.

- What was the best (and worst) email you ever received?

- 12 things today’s gamers don’t remember about old games

Our tech magazine switched from e-mail to email (and from e-book to ebook) within the past year, over the vigorous opposition of the copy editors.

The copy editors’ position was that e-mail preserves the special status of the «e» as the sole surviving remnant of an entire word (electronic), as do the spellings A-bomb («A» for atomic), B-boy («B» for break), C-section («C» for cesarean), f-stop («f» for focal), g-force («g» for gravity), H-bomb («H» for hydrogen). M-day («M» for mobilization), n-type («n» for negative), P-wave («P» for pressure), R-value («R» for resistance), and T-bill («T» for Treasury). The only arguable exception to this pattern that I’m aware of (aside from the disputed email and ebook) is Xmas («X» [standing in for chi] for Christ)—and that example has problems of its own, starting with the fact that it’s a shortened form of a word that is already closed up).

The copy editors further argued that the vast majority of the 55 «e-» words that had shown up at least once in articles for our magazine over the previous ten years benefited from hyphenation as a way to clarify to readers that the words bore the sense «electronic.» Here are some of those terms: e-banking, e-based, e-billing, e-book, e-card, e-census, e-commerce, e-crime, e-customers, e-dating, e-education, e-entertainment, e-filing, e-finance, e-government, e-health, e-ink, e-learning, e-lending, e-magazine [sometimes e-zine], e-money, e-music, e-newspaper, e-payments, e-privacy, e-reader, e-recycling [sometimes e-cycling], e-retailer [sometimes e-tailer], e-schools, e-services, e-shoppers, e-tax, e-ticketing, e-travel, e-voting, e-wallet, e-waste, e-work. As a matter of consistency, the copy editors argued, we should handle all «e-for-electronic» constructions the same way—and realistically that would mean hyphenating all of them, since no one was advocating for ebased, eeducation, eink, eretailer, or ewaste.

The countervailing argument was that spelling e-mail with a hyphen made us look old-fashioned, and that maintaining a broadly consistent approach to punctuation was overrated.

Here’s a radical idea: Maybe all of these words of the G-man («G» for government) type aren’t «compound words» as we normally understand that term. Maybe instead they’re a special class of contractions, with three distinguishing characteristics:

-

The first word of the contracted phrase is reduced to a single letter.

-

That first letter is pronounced as the letter itself, rather than as the sound it would have represented in the original phrase.

-

To indicate the unusual nature of the contraction, we use a hyphen instead of an apostrophe for punctuation.

One point in favor of interpreting these words as contractions is that in their spelled-out form they are neither hyphenated nor closed up: cesarean section, electronic mail, hydrogen bomb. The same characteristic applies to he will, is not, and we had. One very strong argument against doing so is that, as Mr. Scott says, «It’s never been done.» In any event, contractions tend not to lose their identifying punctuation, which puts them on a very different footing from the nonce words (such as «soft-ware» and «bee-keeper») that other answerers have mentioned.