Asked

1 year, 5 months ago

Viewed

101 times

I have a task to find if a word starts with an o ends with a t or both. For finding if it starts or ends the code works fine . For the both part it doesn’t work but I cant find the problem. It should return onetwo if the word starts with o and ends with t.

def one_two(word):

if word[0] == "o":

return "one"

if word[-1] == "t":

return "two"

if word[0] == "o" and word[-1] == "t":

return "onetwo"

assert (one_two("only") == "one")

assert (one_two("cart") == "two")

assert (one_two("o+++t") == "onetwo")

asked Nov 1, 2021 at 19:21

9

You need to check first if both conditions are true, if not the both case would never execute:

def one_two(word):

if word == "":

return "empty"

if word[0] == "o" and word[-1] == "t":

return "onetwo"

elif word[0] == "o":

return "one"

elif word[-1] == "t":

return "two"

print(one_two("only") == "one")

print(one_two("cart") == "two")

print(one_two("o+++t") == "onetwo")

answered Nov 1, 2021 at 19:24

CardstdaniCardstdani

4,9513 gold badges10 silver badges31 bronze badges

0

As already mentioned, you’d need to check the last condition first, as it’s checking both the first and last letter. Note that you can keep the multiple if statements if you want, rather than switch to use elif, because the return statements break out of the function early in any case.

def one_two(word):

try:

fw, *_, lw = word

except ValueError: # empty string, or string is too short

if not word:

return None

fw, lw = word, word

if (fw, lw) == ('o', 't'):

return 'onetwo'

if fw == 'o':

return 'one'

if lw == 't':

return 'two'

assert (one_two("only") == "one")

assert (one_two("cart") == "two")

print(one_two("o+++t"))

assert (one_two("o+++t") == "onetwo")

# edge cases

assert one_two('') is None

assert one_two('o') == 'one'

assert one_two('t') == 'two'

assert one_two('ot') == 'onetwo'

answered Nov 1, 2021 at 19:31

rv.kvetchrv.kvetch

9,2543 gold badges20 silver badges46 bronze badges

0

you are saying return so code doesn’t continue

you can try check it otherway around or simply go like this:

def one_two(word):

msg = ""

if word[0] == "o":

msg += "one"

if word[-1] == "t":

msg += "two"

return msg

assert (one_two("only") == "one")

assert (one_two("cart") == "two")

assert (one_two("o+++t") == "onetwo")

answered Nov 1, 2021 at 19:26

aberkbaberkb

6466 silver badges12 bronze badges

def one_two(word):

return {'o': 'one'}.get(word[0], '') + {'t': 'two'}.get(word[-1], '') if len(word) else ''

answered Nov 1, 2021 at 19:43

Алексей РАлексей Р

7,4442 gold badges7 silver badges18 bronze badges

1

Issue

I have a task to find if a word starts with an o ends with a t or both. For finding if it starts or ends the code works fine . For the both part it doesn’t work but I cant find the problem. It should return onetwo if the word starts with o and ends with t.

def one_two(word):

if word[0] == "o":

return "one"

if word[-1] == "t":

return "two"

if word[0] == "o" and word[-1] == "t":

return "onetwo"

assert (one_two("only") == "one")

assert (one_two("cart") == "two")

assert (one_two("o+++t") == "onetwo")

Solution

You need to check first if both conditions are true, if not the both case would never execute:

def one_two(word):

if word == "":

return "empty"

if word[0] == "o" and word[-1] == "t":

return "onetwo"

elif word[0] == "o":

return "one"

elif word[-1] == "t":

return "two"

print(one_two("only") == "one")

print(one_two("cart") == "two")

print(one_two("o+++t") == "onetwo")

Answered By – Cardstdani

This Answer collected from stackoverflow, is licensed under cc by-sa 2.5 , cc by-sa 3.0 and cc by-sa 4.0

Last update on January 14 2023 06:23:11 (UTC/GMT +8 hours)

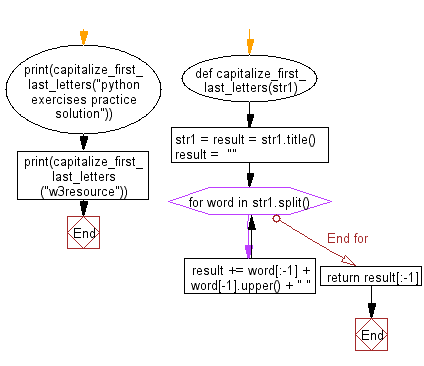

Python String: Exercise-60 with Solution

Write a Python program to capitalize the first and last letters of each word in a given string.

Sample Solution-1:

Python Code:

def capitalize_first_last_letters(str1):

str1 = result = str1.title()

result = ""

for word in str1.split():

result += word[:-1] + word[-1].upper() + " "

return result[:-1]

print(capitalize_first_last_letters("python exercises practice solution"))

print(capitalize_first_last_letters("w3resource"))

Sample Output:

PythoN ExerciseS PracticE SolutioN W3ResourcE

Pictorial Presentation:

Flowchart:

Visualize Python code execution:

The following tool visualize what the computer is doing step-by-step as it executes the said program:

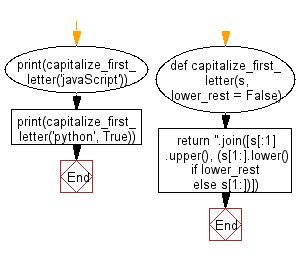

Sample Solution-2:

Capitalizes the first letter of a string.

- Use list slicing and str.upper() to capitalize the first letter of the string.

- Use str.join() to combine the capitalized first letter with the rest of the characters.

- Omit the lower_rest parameter to keep the rest of the string intact, or set it to True to convert to lowercase.

Python Code:

def capitalize_first_letter(s, lower_rest = False):

return ''.join([s[:1].upper(), (s[1:].lower() if lower_rest else s[1:])])

print(capitalize_first_letter('javaScript'))

print(capitalize_first_letter('python', True))

Sample Output:

JavaScript Python

Flowchart:

Visualize Python code execution:

The following tool visualize what the computer is doing step-by-step as it executes the said program:

Python Code Editor:

Have another way to solve this solution? Contribute your code (and comments) through Disqus.

Previous: Write a Python program to find the maximum occuring character in a given string.

Next: Write a Python program to remove duplicate characters of a given string.

What is the difficulty level of this exercise?

Test your Programming skills with w3resource’s quiz.

Python: Tips of the Day

Casts the provided value as a list if it’s not one:

Example:

def tips_cast(val):

return list(val) if isinstance(val, (tuple, list, set, dict)) else [val]

print(tips_cast('bar'))

print(tips_cast([1]))

print(tips_cast(('foo', 'bar')))

Output:

['bar'] [1] ['foo', 'bar']

- Weekly Trends

- Java Basic Programming Exercises

- SQL Subqueries

- Adventureworks Database Exercises

- C# Sharp Basic Exercises

- SQL COUNT() with distinct

- JavaScript String Exercises

- JavaScript HTML Form Validation

- Java Collection Exercises

- SQL COUNT() function

- SQL Inner Join

- JavaScript functions Exercises

- Python Tutorial

- Python Array Exercises

- SQL Cross Join

- C# Sharp Array Exercises

You’ve probably seen the classic piece of «internet trivia» in the image above before — it’s been circulating since at least 2003.

On first glance, it seems legit. Because you can actually read it, right? But, while the meme contains a grain of truth, the reality is always more complicated.

The meme asserts, citing an unnamed Cambridge scientist, that if the first and last letters of a word are in the correct places, you can still read a piece of text.

We’ve unjumbled the message verbatim.

«According to a researche [sic] at Cambridge University, it doesn’t matter in what order the letters in a word are, the only importent [sic] thing is that the first and last letter be at the right place. The rest can be a total mess and you can still read it without problem. This is because the human mind does not read every letter by itself but the word as a whole.»

In fact, there never was a Cambridge researcher (the earliest form of the meme actually circulated without that particular addition), but there is some science behind why we can read that particular jumbled text.

The phenomenon has been given the slightly tongue-in-cheek name «Typoglycaemia,» and it works because our brains don’t just rely on what they see — they also rely on what we expect to see.

In 2011, researchers from the University of Glasgow, conducting unrelated research, found that when something is obscured from or unclear to the eye, human minds can predict what they think they’re going to see and fill in the blanks.

«Effectively, our brains construct an incredibly complex jigsaw puzzle using any pieces it can get access to,» explained researcher Fraser Smith. «These are provided by the context in which we see them, our memories and our other senses.»

However, the meme is only part of the story. Matt Davis, a researcher at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, wanted to get to the bottom of the «Cambridge» claim, since he believed he should have heard of the research before.

He managed to track down the original demonstration of letter randomisation to a researcher named Graham Rawlinson, who wrote his PhD thesis on the topic at Nottingham University in 1976.

He conducted 16 experiments and found that yes, people could recognise words if the middle letters were jumbled, but, as Davis points out, there are several caveats.

- It’s much easier to do with short words, probably because there are fewer variables.

- Function words that provide grammatical structure, such as and, the and a, tend to stay the same because they’re so short. This helps the reader by preserving the structure, making prediction easier.

- Switching adjacent letters, such as porbelm for problem, is easier to translate than switching more distant letters, as in plorebm.

- None of the words in the meme are jumbled to make another word — Davis gives the example of wouthit vs witohut. This is because words that differ only in the position of two adjacent letters, such as calm and clam, or trial and trail, are more difficult to read.

- The words all more or less preserved their original sound — order was changed to oredr instead of odrer, for instance.

- The text is reasonably predictable.

It also helps to keep double letters together. It’s much easier to decipher aoccdrnig and mttaer than adcinorcg and metatr, for example.

There is evidence to suggest that ascending and descending elements play a role, too — that what we’re recognising is the shape of a word. This is why mixed-case text, such as alternating caps, is so difficult to read — it radically changes the shape of a word, even when all the letters are in the right place.

If you have a play around with this generator, you can see for yourself how properly randomising the middle letters of words can make text extremely difficult to read. Try this:

The adkmgowenlcent — whcih cmeos in a reropt of new mcie etpnremxeis taht ddin’t iotdncure scuh mantiotus — isn’t thelcclnaiy a rtoatriecn of tiher eearlir fidginns, but it geos a lnog way to shnwiog taht the aalrm blels suhold plarobby neevr hvae been sdnuoed in the fsrit plcae.

Maybe that one is cheating a little — it’s a paragraph from a ScienceAlert story about CRISPR.

The acknowledgment — which comes in a report of new mice experiments that didn’t introduce such mutations — isn’t technically a retraction of their earlier findings, but it goes a long way to showing that the alarm bells should probably never have been sounded in the first place.

See how you go with this one.

Soaesn of mtiss and mloelw ftisnflurues,

Csloe boosm-feinrd of the mrtuniag sun;

Cnponsiirg wtih him how to laod and besls

Wtih friut the viens taht runod the tahtch-eevs run

That’s the first four lines of the poem «To Autumn» by John Keats.

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run

So while there are some fascinating cognitive processes behind how we use prediction and word shape to improve our reading skills, it really isn’t as simple as that meme would have you believe.

If you want to delve into the topic further, you can read Davis’ full and fascinating analysis here.

#!/usr/bin/perl

my $first_last = ”;

my $word = “This-is-my-word”;

my @letters = split(//, $word);

$first_last = $letters[0] . “….” . $letters[$#letters];

print $first_last;

Tags: perl tips, programming

This entry was posted on 2011/09/24 at 1:16 am and is filed under Programming, Server side — Perl. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

2 Responses to “how to get the first and last letters of a word”

-

bislinks Says:

2011/10/08 at 3:56 pm | Reply

As the Perl experts say: “there is more than one way to do the same thing in perl;” here is another way to get the same results:

#!/usr/bin/perl

use CGI; use strict; my $q=new CGI; print $q->header(-type=>’text/html’);my $word = “This-is-a-word or a sentence “;

my @word = split(//, $word);

my $total = scalar(@word);

my $middle = scalar(@word) / 2;

$middle = substr($middle, 0, 2);

my $first = substr($word, 0, 1);

my $last = substr($word, -1, 1);

my $mid = substr($word, $middle, 1);print $q->start_html(-title=>’word magic in perl’);

print qq~The complete word is $word.

The first letter is $firstand the last letter is $last

and the exact middle letter is $mid

total letters in the word is $total

the number of the middle letter is $middleHere is a link to the complete documentation on substrings at perl.org

~;print $q->end_html();

-

bislinks Says:

2011/10/08 at 7:19 pm | Reply

Click here to see the output of the above script.