Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

Best Answer

Copy

The word for ‘Finland’ in Finnish is Suomi. This word made also be user to refer to the language itself, Finnish.

Please see the related links below if you’re interested in hearing a native speaker’s pronunciation of ‘Suomi’.

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

📓

See all Study Guides

✍️

Create a Study Guide

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the Finnish name for Finland?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

The majority of nations in the world name the country as “Finland”, Finns name their country Suomi.

Finland.

The origin of word Finland is dark and mysterious. Fennits or poor hunters who are mentioned by Tatsit in the treatise “the origin of Germans and a site of Germany”, under the description remind more Samis. A popular belief is that a word fennit has been borrowed from the German languages and designated wanderers.

Under other version the name of Finland occurs from man’s name Fin (in ancient documents there are also names Finn, Fenrir, Finnegan) which was spread in Scandinavia and Ireland. Some sources date Finland to the root fen – a bog, that is it turns out that Finland is the country of bogs instead of lakes. In 14 century when Finland was a part of Sweden, the Swedish deputies in Finland were called capitaneus Finlandiae. So, Finlandiae, Sweden officially named a southwest part of Finland belonging to it with a chief town of Turku.

Suomi

For a long time disputes are conducted discussing whence the word of Suomi originates from. In 20 century the Finnish grandmothers told to their grandsons that the country Suomi is obliged by the name to the marshy landscapes, that Suomi comes from the Finnish word suo, a bog. By another version Suomi has one root with a word suomu (scales) because there lived people doing clothes from a beautiful and elastic fish skin of breeds salmon. One more version withdraws the name of Finland to a word suoma – something like “gifted soil, earth”.

By the word of Suomi was called in the Middle Ages the province of Varsinajs-Suomi (actually the present Finland) at southwest coast of the country. Later, in the beginning of 15 centuries its name has extended to all Finland, in particular, the Swedish king Gustav Vaza called itself Grand duke of Suomi. His son Juhana III subscribed a title of Grand duke Suomi: Suomen Suuriruhtinas. Now, when the most part of the Finnish bogs is drained, the fish skin is left in the past, and the earths are not favored for anybody, these theories have hopelessly become outdated. Modern researches say that word Suomi has been borrowed, and it took place probably more than 4000 years ago.

One of the theories asserts that the word Suomi representatives of Indo-European culture have brought with themselves, they are probable ancestors of balts which were located at southern coast of Finland approximately in 2500 B.C. Ancient settlers named this place zeme, the earth. To the same root there ascend slavic and Baltic names “the earth” in Russian, Polish, Chech, Latvian. In due course in the Finnish dialects zeme it was transformed in säme, and from it in häme (Häme is a province in the western Finland), saame (Samis) and soome came, whence has occurred the modern name of Finland Suomi. This can seem strange, but linguists prove that words zeme and suomi are etymologically close, unlike the words suomi and suomu.

|

Republic of Finland

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Maamme (Finnish) Vårt land (Swedish) (English: «Our Land») |

|

|

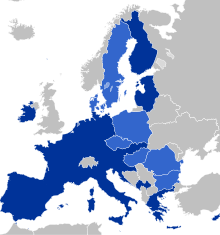

Location of Finland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Helsinki 60°10′15″N 24°56′15″E / 60.17083°N 24.93750°E |

| Official languages |

|

| Recognized national languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2021)[1][2] |

|

| Religion

(2021)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic[4] |

|

• President |

Sauli Niinistö |

|

• Prime Minister |

Sanna Marin |

|

• Speaker of the Parliament |

Petteri Orpo |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence

from Russia |

|

|

• Integration and autonomy in the Russian Empire |

29 March 1809 |

|

• Declaration of Independence |

6 December 1917 |

|

• Finnish Civil War |

January – May 1918 |

|

• Constitution established |

17 July 1919 |

|

• Winter War |

30 November 1939 – 13 March 1940 |

|

• Continuation War |

25 June 1941 – 19 September 1944 |

|

• Joined the EU |

1 January 1995 |

|

• Joined NATO |

4 April 2023 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

338,455 km2 (130,678 sq mi) (65th) |

|

• Water (%) |

9.71 (2015)[5] |

| Population | |

|

• 2023 estimate |

|

|

• Density |

16.4/km2 (42.5/sq mi) (213th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2021) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 11th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy[10] |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +358 |

| ISO 3166 code | FI |

| Internet TLD | .fi, .axa |

|

Finland (Finnish: Suomi [ˈsuo̯mi] (listen); Swedish: Finland [ˈfɪ̌nland] (

listen)), officially the Republic of Finland (Finnish: Suomen tasavalta; Swedish: Republiken Finland (

listen to all)),[note 2] is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, across from Estonia. Finland covers an area of 338,455 square kilometres (130,678 sq mi) with a population of 5.6 million. Helsinki is the capital and largest city. The vast majority of the population are ethnic Finns. Finnish and Swedish are the official languages, Swedish is the native language of 5.2% of the population.[11] Finland’s climate varies from humid continental in the south to the boreal in the north. The land cover is primarily a boreal forest biome, with more than 180,000 recorded lakes.[12]

Finland was first inhabited around 9000 BC after the Last Glacial Period.[13] The Stone Age introduced several different ceramic styles and cultures. The Bronze Age and Iron Age were characterized by contacts with other cultures in Fennoscandia and the Baltic region.[14] From the late 13th century, Finland became a part of Sweden as a consequence of the Northern Crusades. In 1809, as a result of the Finnish War, Finland became part of the Russian Empire as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, during which Finnish art flourished and the idea of independence began to take hold. In 1906, Finland became the first European state to grant universal suffrage, and the first in the world to give all adult citizens the right to run for public office.[15][note 3] After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Finland declared independence from Russia. In 1918, the fledgling state was divided by the Finnish Civil War. During World War II, Finland fought the Soviet Union in the Winter War and the Continuation War, and Nazi Germany in the Lapland War. It subsequently lost parts of its territory, but maintained its independence.

Finland largely remained an agrarian country until the 1950s. After World War II, it rapidly industrialized and developed an advanced economy, while building an extensive welfare state based on the Nordic model; the country soon enjoyed widespread prosperity and a high per capita income.[16] During the Cold War, Finland adopted an official policy of neutrality. Finland joined the European Union in 1995, the Eurozone at its inception in 1999 and NATO in 2023. Finland is a top performer in numerous metrics of national performance, including education, economic competitiveness, civil liberties, quality of life and human development.[17][18][19][20]

History

Prehistory

The area that is now Finland was settled in, at the latest, around 8,500 BC during the Stone Age towards the end of the last glacial period. The artefacts the first settlers left behind present characteristics that are shared with those found in Estonia, Russia, and Norway.[23] The earliest people were hunter-gatherers, using stone tools.[24]

The first pottery appeared in 5200 BC, when the Comb Ceramic culture was introduced.[25] The arrival of the Corded Ware culture in Southern coastal Finland between 3000 and 2500 BC may have coincided with the start of agriculture.[26] Even with the introduction of agriculture, hunting and fishing continued to be important parts of the subsistence economy.

In the Bronze Age permanent all-year-round cultivation and animal husbandry spread, but the cold climate phase slowed the change.[27] The Seima-Turbino phenomenon brought the first bronze artefacts to the region and possibly also the Finno-Ugric languages.[27][28] Commercial contacts that had so far mostly been to Estonia started to extend to Scandinavia. Domestic manufacture of bronze artefacts started 1300 BC.[29]

In the Iron Age population grew. Finland Proper was the most densely populated area. Commercial contacts in the Baltic Sea region grew and extended during the eighth and ninth centuries. Main exports from Finland were furs, slaves, castoreum, and falcons to European courts. Imports included silk and other fabrics, jewelry, Ulfberht swords, and, in lesser extent, glass. Production of iron started approximately in 500 BC.[30] At the end of the ninth century, indigenous artefact culture, especially weapons and women’s jewelry, had more common local features than ever before. This has been interpreted to be expressing common Finnish identity.[31]

An ancient Finnish man’s outfit. The interpretation is based on the findings of the cemetery which dates from the late 13th century to the early 15th century.

An early form of Finnic languages spread to the Baltic Sea region approximately 1900 BC. Common Finnic language was spoken around Gulf of Finland 2000 years ago. The dialects from which the modern-day Finnish language was developed came into existence during the Iron Age.[32] Although distantly related, the Sami people retained the hunter-gatherer lifestyle longer than the Finns. The Sami cultural identity and the Sami language have survived in Lapland, the northernmost province.

The name Suomi (Finnish for ‘Finland’) has uncertain origins, but a common etymology with saame (the Sami) has been suggested.[33][34] In the earliest historical sources, from the 12th and 13th centuries, the term Finland refers to the coastal region around Turku. This region later became known as Finland Proper in distinction from the country name Finland.[35] See also Etymology of Finns.

Swedish era

The 12th and 13th centuries were a violent time in the northern Baltic Sea. The Livonian Crusade was ongoing and the Finnish tribes such as the Tavastians and Karelians were in frequent conflicts with Novgorod and with each other. Also, during the 12th and 13th centuries several crusades from the Catholic realms of the Baltic Sea area were made against the Finnish tribes. Danes waged at least three crusades to Finland, in 1187 or slightly earlier,[36] in 1191 and in 1202,[37] and Swedes, possibly the so-called second crusade to Finland, in 1249 against Tavastians and the third crusade to Finland in 1293 against the Karelians. The so-called first crusade to Finland, possibly in 1155, is most likely an unreal event.[38]

As a result of the crusades (mostly with the second crusade led by Birger Jarl) and the colonization of some Finnish coastal areas with Christian Swedish population during the Middle Ages,[39] Finland gradually became part of the kingdom of Sweden and the sphere of influence of the Catholic Church.[40] Under Sweden, Finland was annexed as part of the cultural order of Western Europe.[41]

Now lying within Helsinki, Suomenlinna is a UNESCO World Heritage Site consisting of an inhabited 18th-century sea fortress built on six islands. It is one of Finland’s most popular tourist attractions.

Swedish was the dominant language of the nobility, administration, and education; Finnish was chiefly a language for the peasantry, clergy, and local courts in predominantly Finnish-speaking areas. During the Protestant Reformation, the Finns gradually converted to Lutheranism.[42]

In the 16th century, a bishop and Lutheran Reformer Mikael Agricola published the first written works in Finnish;[43] and Finland’s current capital city, Helsinki, was founded by King Gustav Vasa in 1555.[44] The first university in Finland, the Royal Academy of Turku, was established by Queen Christina of Sweden at the proposal of Count Per Brahe in 1640.[45][46]

The Finns reaped a reputation in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) as a well-trained cavalrymen called «Hakkapeliitta».[47][48] Finland suffered a severe famine in 1695–1697, during which about one third of the Finnish population died,[49] and a devastating plague a few years later.

In the 18th century, wars between Sweden and Russia twice led to the occupation of Finland by Russian forces, times known to the Finns as the Greater Wrath (1714–1721) and the Lesser Wrath (1742–1743).[50][49] It is estimated that almost an entire generation of young men was lost during the Great Wrath, due mainly to the destruction of homes and farms, and the burning of Helsinki.[51]

Russian era

The Swedish era ended in the Finnish War in 1809. On 29 March 1809, having been taken over by the armies of Alexander I of Russia, Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire with the recognition given at the Diet held in Porvoo. This situation lasted until the end of 1917.[50] In 1812, Alexander I incorporated the Russian Vyborg province into the Grand Duchy of Finland. In 1854, Finland became involved in Russia’s involvement in the Crimean War, when the British and French navies bombed the Finnish coast and Åland during the so-called Åland War.[52]

During the Russian era, the Finnish language began to gain recognition. From the 1860s onwards, a strong Finnish nationalist movement known as the Fennoman movement grew. One of its most prominent leading figures of the movement was the philosopher and politician J. V. Snellman, who pushed for the stabilization of the status of the Finnish language and its own currency, the Finnish markka, in the Grand Duchy of Finland.[52][53] Milestones included the publication of what would become Finland’s national epic – the Kalevala – in 1835, and the Finnish language’s achieving equal legal status with Swedish in 1892. In the spirit of the notion of Adolf Ivar Arwidsson (1791–1858) – «we are not Swedes, we do not want to become Russians, let us, therefore, be Finns» – a Finnish national identity was established.[54] Still there was no genuine independence movement in Finland until the early 20th century.[55]

The Finnish famine of 1866–1868 occurred after freezing temperatures in early September ravaged crops,[56] and it killed approximately 15% of the population, making it one of the worst famines in European history. The famine led the Russian Empire to ease financial regulations, and investment rose in the following decades. Economic development was rapid.[57] The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was still half of that of the United States and a third of that of Britain.[57]

From 1869 until 1917, the Russian Empire pursued a policy known as the «Russification of Finland». This policy was interrupted between 1905 and 1908. In 1906, universal suffrage was adopted in the Grand Duchy of Finland. However, the relationship between the Grand Duchy and the Russian Empire soured when the Russian government made moves to restrict Finnish autonomy. For example, universal suffrage was, in practice, virtually meaningless, since the tsar did not have to approve any of the laws adopted by the Finnish parliament. The desire for independence gained ground, first among radical liberals[58] and socialists, driven in part by a declaration called the February Manifesto by the last tsar of the Russian Empire, Nicholas II, on 15 February 1899.[59]

Civil war and early independence

After the 1917 February Revolution, the position of Finland as part of the Russian Empire was questioned, mainly by Social Democrats. The Parliament, controlled by social democrats, passed the so-called Power Act to give the highest authority to the Parliament. This was rejected by the Russian Provisional Government which decided to dissolve the Parliament.[60] New elections were conducted, in which right-wing parties won with a slim majority. Some social democrats refused to accept the result and still claimed that the dissolution of the parliament (and thus the ensuing elections) were extralegal. The two nearly equally powerful political blocs, the right-wing parties, and the social-democratic party were highly antagonized.

The October Revolution in Russia changed the geopolitical situation once more. Suddenly, the right-wing parties in Finland started to reconsider their decision to block the transfer of the highest executive power from the Russian government to Finland, as the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. The right-wing government, led by Prime Minister P. E. Svinhufvud, presented Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917, which was officially approved on 6 December, by the Finnish Parliament. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), led by Vladimir Lenin, recognized independence on 4 January 1918.[61]

On 27 January 1918 the government’s began to disarm the Russian forces in Pohjanmaa. The socialists gained control of southern Finland and Helsinki, but the White government continued in exile from Vaasa.[62][63] This sparked the brief but bitter civil war. The Whites, who were supported by Imperial Germany, prevailed over the Reds,[64] and their self-proclaimed Finnish Socialist Workers’ Republic.[65] After the war, tens of thousands of Reds were interned in camps, where thousands were executed or died from malnutrition and disease. Deep social and political enmity was sown between the Reds and Whites and would last until the Winter War and even beyond.[66][67] The civil war and the 1918–1920 activist expeditions called «Kinship Wars» into Soviet Russia strained Eastern relations.[68][69]

After brief experimentation with monarchy, when an attempt to make Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse King of Finland was unsuccessful, Finland became a presidential republic, with K. J. Ståhlberg elected as its first president in 1919. As a liberal nationalist with a legal background, Ståhlberg anchored the state in liberal democracy, supported the rule of law, and embarked on internal reforms.[70] Finland was also one of the first European countries to strongly aim for equality for women, with Miina Sillanpää serving in Väinö Tanner’s cabinet as the first female minister in Finnish history in 1926–1927.[71] The Finnish–Russian border was defined in 1920 by the Treaty of Tartu, largely following the historic border but granting Pechenga (Finnish: Petsamo) and its Barents Sea harbour to Finland.[50] Finnish democracy did not experience any Soviet coup attempts and likewise survived the anti-communist Lapua Movement.

In 1917, the population was three million. Credit-based land reform was enacted after the civil war, increasing the proportion of the capital-owning population.[57] About 70% of workers were occupied in agriculture and 10% in industry.[72]

World War II

The Soviet Union launched the Winter War on 30 November 1939 in an effort to annex Finland.[73] The Finnish Democratic Republic was established by Joseph Stalin at the beginning of the war to govern Finland after Soviet conquest.[74] The Red Army was defeated in numerous battles, notably at the Battle of Suomussalmi. After two months of negligible progress on the battlefield, as well as severe losses of men and materiel, the Soviets put an end to the Finnish Democratic Republic in late January 1940 and recognized the legal Finnish government as the legitimate government of Finland.[75] Soviet forces began to make progress in February and reached Vyborg in March. The fighting came to an end on 13 March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland had successfully defended its independence, but ceded 9% of its territory to the Soviet Union.

Hostilities resumed in June 1941 with the Continuation War, when Finland aligned with Germany following the latter’s invasion of the Soviet Union; the primary aim was to recapture the territory lost to the Soviets scarcely one year before.[76] Finnish forces occupied East Karelia from 1941 to 1944. Finnish resistance to the Vyborg–Petrozavodsk offensive in the summer of 1944 led to a standstill, and the two sides reached an armistice. This was followed by the Lapland War of 1944–1945, when Finland fought retreating German forces in northern Finland. Famous war heroes of the aforementioned wars include Simo Häyhä,[77][78] Aarne Juutilainen,[79] and Lauri Törni.[80]

The Armistice and treaty signed with the Soviet Union in 1944 and 1948 included Finnish obligations, restraints, and reparations, as well as further Finnish territorial concessions in addition to those in the Moscow Peace Treaty. As a result of the two wars, Finland ceded Petsamo, along with parts of Finnish Karelia and Salla; this amounted to 12% of Finland’s land area, 20% of its industrial capacity, its second-largest city, Vyborg (Viipuri), and the ice-free port of Liinakhamari (Liinahamari). Almost the whole Finnish population, some 400,000 people, fled these areas. Finland lost 97,000 soldiers and was forced to pay war reparations of $300 million ($3.7 billion in 2021); nevertheless, it avoided occupation by Soviet forces and managed to retain its independence.

For a few decades after 1944, the Communists were a strong political party. The Soviet Union persuaded Finland to reject Marshall Plan aid. However, in the hope of preserving Finland’s independence, the United States provided secret development aid and helped the Social Democratic Party.[81]

After the war

Urho Kekkonen was Finland’s longest-serving president in 1956–1982.

Establishing trade with the Western powers, such as the United Kingdom, and paying reparations to the Soviet Union produced a transformation of Finland from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrialized one. Valmet (originally a shipyard, then several metal workshops) was founded to create materials for war reparations. After the reparations had been paid off, Finland continued to trade with the Soviet Union in the framework of bilateral trade.

In 1950, 46% of Finnish workers worked in agriculture and a third lived in urban areas.[82] The new jobs in manufacturing, services, and trade quickly attracted people to the towns. The average number of births per woman declined from a baby boom peak of 3.5 in 1947 to 1.5 in 1973.[82] When baby boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs quickly enough, and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, with emigration peaking in 1969 and 1970.[82] Finland took part in trade liberalization in the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet bloc during the Cold War. The military YYA Treaty (Finno-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance) gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics. This was extensively exploited by president Urho Kekkonen against his opponents. He maintained an effective monopoly on Soviet relations from 1956 on, which was crucial for his continued popularity. In politics, there was a tendency to avoid any policies and statements that could be interpreted as anti-Soviet. This phenomenon was given the name «Finlandization» by the West German press.[83]

Finland maintained a market economy. Various industries benefited from trade privileges with the Soviets. Economic growth was rapid in the postwar era, and by 1975 Finland’s GDP per capita was the 15th-highest in the world. In the 1970s and 1980s, Finland built one of the most extensive welfare states in the world. Finland negotiated with the European Economic Community (EEC, a predecessor of the European Union) a treaty that mostly abolished customs duties towards the EEC starting from 1977. In 1981, President Urho Kekkonen’s failing health forced him to retire after holding office for 25 years.

Miscalculated macroeconomic decisions, a banking crisis, the collapse of its largest trading partner (the Soviet Union), and a global economic downturn caused a deep early 1990s recession in Finland. The depression bottomed out in 1993, and Finland saw steady economic growth for more than ten years.[84] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland began increasing integration with the West.[85] Finland joined the European Union in 1995, and the Eurozone in 1999. Much of the late 1990s economic growth was fueled by the success of the mobile phone manufacturer Nokia.[41]

21st century

Prime Minister Sanna Marin and President Sauli Niinistö at the press conference announcing Finland’s intent to apply to NATO on 15 May 2022

The Finnish population elected Tarja Halonen in the 2000 Presidential election, making her the first female President of Finland.[86] Financial crises paralyzed Finland’s exports in 2008, resulting in weaker economic growth throughout the decade.[87][88] Sauli Niinistö has subsequently been elected the President of Finland since 2012.[89]

Finland’s support for NATO rose enormously after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[90][91][92] On 11 May 2022, Finland entered into a mutual security pact with the United Kingdom.[93] On 12 May, Finland’s president and prime minister called for NATO membership «without delay».[94] Subsequently, on 17 May, the Parliament of Finland decided by a vote of 188–8 that it supported Finland’s accession to NATO.[95][96] On 18 May the president and foreign minister submitted the application for membership.[97] Finland became a member of NATO on 4 April 2023.[98]

Geography

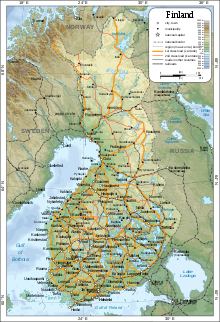

Topographic map of Finland

Lying approximately between latitudes 60° and 70° N, and longitudes 20° and 32° E, Finland is one of the world’s northernmost countries. Of world capitals, only Reykjavík lies more to the north than Helsinki. The distance from the southernmost point – Hanko in Uusimaa – to the northernmost – Nuorgam in Lapland – is 1,160 kilometres (720 mi).

Finland has about 168,000 lakes (of area larger than 500 m2 or 0.12 acres) and 179,000 islands.[99] Its largest lake, Saimaa, is the fourth largest in Europe. The Finnish Lakeland is the area with the most lakes in the country; many of the major cities in the area, most notably Tampere, Jyväskylä and Kuopio, are located near the large lakes. The greatest concentration of islands is found in the southwest, in the Archipelago Sea between continental Finland and the main island of Åland.

Much of the geography of Finland is a result of the Ice Age. The glaciers were thicker and lasted longer in Fennoscandia compared with the rest of Europe. Their eroding effects have left the Finnish landscape mostly flat with few hills and fewer mountains. Its highest point, the Halti at 1,324 metres (4,344 ft), is found in the extreme north of Lapland at the border between Finland and Norway. The highest mountain whose peak is entirely in Finland is Ridnitšohkka at 1,316 m (4,318 ft), directly adjacent to Halti.

The retreating glaciers have left the land with morainic deposits in formations of eskers. These are ridges of stratified gravel and sand, running northwest to southeast, where the ancient edge of the glacier once lay. Among the biggest of these are the three Salpausselkä ridges that run across southern Finland.

Having been compressed under the enormous weight of the glaciers, terrain in Finland is rising due to the post-glacial rebound. The effect is strongest around the Gulf of Bothnia, where land steadily rises about 1 cm (0.4 in) a year. As a result, the old sea bottom turns little by little into dry land: the surface area of the country is expanding by about 7 square kilometres (2.7 sq mi) annually.[100] Relatively speaking, Finland is rising from the sea.[101]

The landscape is covered mostly by coniferous taiga forests and fens, with little cultivated land. Of the total area, 10% is lakes, rivers, and ponds, and 78% is forest. The forest consists of pine, spruce, birch, and other species.[102] Finland is the largest producer of wood in Europe and among the largest in the world. The most common type of rock is granite. It is a ubiquitous part of the scenery, visible wherever there is no soil cover. Moraine or till is the most common type of soil, covered by a thin layer of humus of biological origin. Podzol profile development is seen in most forest soils except where drainage is poor. Gleysols and peat bogs occupy poorly drained areas.

Biodiversity

In Finland, Reindeers graze in Lapland area and on the fells.

In recent decades, Wolverine populations have grown in Finland.

Phytogeographically, Finland is shared between the Arctic, central European, and northern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Finland can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Scandinavian and Russian taiga, Sarmatic mixed forests, and Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands.[104] Taiga covers most of Finland from northern regions of southern provinces to the north of Lapland. On the southwestern coast, south of the Helsinki-Rauma line, forests are characterized by mixed forests, that are more typical in the Baltic region. In the extreme north of Finland, near the tree line and Arctic Ocean, Montane Birch forests are common. Finland had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.08/10, ranking it 109th globally out of 172 countries.[105]

Similarly, Finland has a diverse and extensive range of fauna. There are at least sixty native mammalian species, 248 breeding bird species, over 70 fish species, and 11 reptile and frog species present today, many migrating from neighbouring countries thousands of years ago.

Large and widely recognized wildlife mammals found in Finland are the brown bear, grey wolf, wolverine, and elk. Three of the more striking birds are the whooper swan, a large European swan and the national bird of Finland; the Western capercaillie, a large, black-plumaged member of the grouse family; and the Eurasian eagle-owl. The latter is considered an indicator of old-growth forest connectivity, and has been declining because of landscape fragmentation.[106] Around 24,000 species of insects are prevalent in Finland some of the most common being hornets with tribes of beetles such as the Onciderini also being common. The most common breeding birds are the willow warbler, common chaffinch, and redwing.[107] Of some seventy species of freshwater fish, the northern pike, perch, and others are plentiful. Atlantic salmon remains the favourite of fly rod enthusiasts.

The endangered Saimaa ringed seal, one of only three lake seal species in the world, exists only in the Saimaa lake system of southeastern Finland, down to only 390 seals today.[108][109] The species has become the emblem of the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation.[110]

A third of Finland’s land area originally consisted of moorland, about half of this area has been drained for cultivation over the past centuries.[111]

Climate

The main factor influencing Finland’s climate is the country’s geographical position between the 60th and 70th northern parallels in the Eurasian continent’s coastal zone. In the Köppen climate classification, the whole of Finland lies in the boreal zone, characterized by warm summers and freezing winters. Within the country, the temperateness varies considerably between the southern coastal regions and the extreme north, showing characteristics of both a maritime and a continental climate. Finland is near enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be continuously warmed by the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream combines with the moderating effects of the Baltic Sea and numerous inland lakes to explain the unusually warm climate compared with other regions that share the same latitude, such as Alaska, Siberia, and southern Greenland.[112]

Winters in southern Finland (when mean daily temperature remains below 0 °C or 32 °F) are usually about 100 days long, and in the inland the snow typically covers the land from about late November to April, and on the coastal areas such as Helsinki, snow often covers the land from late December to late March.[113] Even in the south, the harshest winter nights can see the temperatures fall to −30 °C (−22 °F) although on coastal areas like Helsinki, temperatures below −30 °C (−22 °F) are rare. Climatic summers (when mean daily temperature remains above 10 °C or 50 °F) in southern Finland last from about late May to mid-September, and in the inland, the warmest days of July can reach over 35 °C (95 °F).[112] Although most of Finland lies on the taiga belt, the southernmost coastal regions are sometimes classified as hemiboreal.[114]

In northern Finland, particularly in Lapland, the winters are long and cold, while the summers are relatively warm but short. On the most severe winter days in Lapland can see the temperature fall to −45 °C (−49 °F). The winter of the north lasts for about 200 days with permanent snow cover from about mid-October to early May. Summers in the north are quite short, only two to three months, but can still see maximum daily temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F) during heat waves.[112] No part of Finland has Arctic tundra, but Alpine tundra can be found at the fells Lapland.[114]

The Finnish climate is suitable for cereal farming only in the southernmost regions, while the northern regions are suitable for animal husbandry.[115]

A quarter of Finland’s territory lies within the Arctic Circle and the midnight sun can be experienced for more days the farther north one travels. At Finland’s northernmost point, the sun does not set for 73 consecutive days during summer and does not rise at all for 51 days during winter.[112]

Regions

Finland consists of 19 regions (maakunta). The counties are governed by regional councils which serve as forums of cooperation for the municipalities of a county. The main tasks of the counties are regional planning and development of enterprise and education. In addition, the public health services are usually organized based on counties. Regional councils are elected by municipal councils, each municipality sending representatives in proportion to its population. In addition to inter-municipal cooperation, which is the responsibility of regional councils, each county has a state Employment and Economic Development Centre which is responsible for the local administration of labour, agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and entrepreneurial affairs. Historically, counties are divisions of historical provinces of Finland, areas that represent local dialects and culture more accurately.

Six Regional State Administrative Agencies are responsible for one of the counties called alue in Finnish; in addition, Åland was designated a seventh county.[116]

| Regional map | English Name[117] | Finnish name | Swedish name | Capital | Regional state administrative agency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Lapland | Lappi | Lappland | Rovaniemi | Lapland |

| North Ostrobothnia | Pohjois-Pohjanmaa | Norra Österbotten | Oulu | Northern Finland | |

| Kainuu | Kainuu | Kajanaland | Kajaani | Northern Finland | |

| North Karelia | Pohjois-Karjala | Norra Karelen | Joensuu | Eastern Finland | |

| North Savo | Pohjois-Savo | Norra Savolax | Kuopio | Eastern Finland | |

| South Savo | Etelä-Savo | Södra Savolax | Mikkeli | Eastern Finland | |

| South Ostrobothnia | Etelä-Pohjanmaa | Södra Österbotten | Seinäjoki | Western and Central Finland | |

| Central Ostrobothnia | Keski-Pohjanmaa | Mellersta Österbotten | Kokkola | Western and Central Finland | |

| Ostrobothnia | Pohjanmaa | Österbotten | Vaasa | Western and Central Finland | |

| Pirkanmaa | Pirkanmaa | Birkaland | Tampere | Western and Central Finland | |

| Central Finland | Keski-Suomi | Mellersta Finland | Jyväskylä | Western and Central Finland | |

| Satakunta | Satakunta | Satakunta | Pori | South-Western Finland | |

| Southwest Finland | Varsinais-Suomi | Egentliga Finland | Turku | South-Western Finland | |

| South Karelia | Etelä-Karjala | Södra Karelen | Lappeenranta | Southern Finland | |

| Päijät-Häme | Päijät-Häme | Päijänne-Tavastland | Lahti | Southern Finland | |

| Kanta-Häme | Kanta-Häme | Egentliga Tavastland | Hämeenlinna | Southern Finland | |

| Uusimaa | Uusimaa | Nyland | Helsinki | Southern Finland | |

| Kymenlaakso | Kymenlaakso | Kymmenedalen | Kotka and Kouvola | Southern Finland | |

| Åland[note 4] | Ahvenanmaa | Åland | Mariehamn | Åland |

The county of Eastern Uusimaa (Itä-Uusimaa) was consolidated with Uusimaa on 1 January 2011.[118]

Administrative divisions

The fundamental administrative divisions of the country are the municipalities, which may also call themselves towns or cities. They account for half of the public spending. Spending is financed by municipal income tax, state subsidies, and other revenue. As of 2021, there are 309 municipalities,[119] and most have fewer than 6,000 residents.

In addition to municipalities, two intermediate levels are defined. Municipalities co-operate in seventy sub-regions and nineteen counties. These are governed by the member municipalities and have only limited powers. The autonomous province of Åland has a permanent democratically elected regional council. Sami people have a semi-autonomous Sami native region in Lapland for issues on language and culture.

In the following chart, the number of inhabitants includes those living in the entire municipality (kunta/kommun), not just in the built-up area. The land area is given in km2, and the density in inhabitants per km2 (land area). The figures are as of 28 February 2023. The capital region – comprising Helsinki, Vantaa, Espoo and Kauniainen – forms a continuous conurbation of over 1.1 million people. However, common administration is limited to voluntary cooperation of all municipalities, e.g. in Helsinki Metropolitan Area Council.

| City | Population[120] | Land area[121] | Density | Regional map | Population density map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helsinki | 665,558 | 213.75 | 3,113.72 |

Municipalities (thin borders) and counties (thick borders) of Finland (2021) |

The population densities of Finnish municipalities (2010) |

| Espoo | 306,792 | 312.26 | 982.49 | ||

| Tampere | 249,720 | 525.03 | 475.63 | ||

| Vantaa | 243,496 | 238.37 | 1,021.5 | ||

| Oulu | 212,127 | 1,410.17 | 150.43 | ||

| Turku | 198,211 | 245.67 | 806.82 | ||

| Jyväskylä | 145,962 | 1,170.99 | 124.65 | ||

| Kuopio | 122,615 | 1,597.39 | 76.76 | ||

| Lahti | 120,211 | 459.47 | 261.63 | ||

| Pori | 83,171 | 834.06 | 99.72 | ||

| Kouvola | 79,309 | 2,558.24 | 31 | ||

| Joensuu | 77,480 | 2,381.76 | 32.53 | ||

| Lappeenranta | 72,595 | 1,433.36 | 50.65 | ||

| Hämeenlinna | 68,011 | 1,785.76 | 38.09 | ||

| Vaasa | 68,049 | 188.81 | 360.41 |

Government and politics

Constitution

The Constitution of Finland defines the political system; Finland is a parliamentary republic within the framework of a representative democracy. The Prime Minister is the country’s most powerful person. Citizens can run and vote in parliamentary, municipal, presidential, and European Union elections.

President

Finland’s head of state is the President of the Republic. Finland has had for most of its independence a semi-presidential system of government, but in the last few decades the powers of the President have been diminished, and the country is now considered a parliamentary republic.[4] A new constitution enacted in 2000, have made the presidency a primarily ceremonial office that appoints the Prime Minister as elected by Parliament, appoints and dismisses the other ministers of the Finnish Government on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, opens parliamentary sessions, and confers state honors. Nevertheless, the President remains responsible for Finland’s foreign relations, including the making of war and peace, but excluding matters related to the European Union. Moreover, the President exercises supreme command over the Finnish Defence Forces as commander-in-chief. In the exercise of his or her foreign and defense powers, the President is required to consult the Finnish Government, but the Government’s advice is not binding. In addition, the President has several domestic reserve powers, including the authority to veto legislation, to grant pardons, and to appoint several public officials. The President is also required by the Constitution to dismiss individual ministers or the entire Government upon a parliamentary vote of no confidence.[122]

The President is directly elected via runoff voting for a maximum of two consecutive 6-year terms. The current president is Sauli Niinistö; he took office on 1 March 2012. Former presidents were K. J. Ståhlberg (1919–1925), L. K. Relander (1925–1931), P. E. Svinhufvud (1931–1937), Kyösti Kallio (1937–1940), Risto Ryti (1940–1944), C. G. E. Mannerheim (1944–1946), J. K. Paasikivi (1946–1956), Urho Kekkonen (1956–1982), Mauno Koivisto (1982–1994), Martti Ahtisaari (1994–2000), and Tarja Halonen (2000–2012).

Parliament

The Session Hall of the Parliament of Finland

The 200-member unicameral Parliament of Finland (Finnish: Eduskunta) exercises supreme legislative authority in the country. It may alter the constitution and ordinary laws, dismiss the cabinet, and override presidential vetoes. Its acts are not subject to judicial review; the constitutionality of new laws is assessed by the parliament’s constitutional law committee. The parliament is elected for a term of four years using the proportional D’Hondt method within several multi-seat constituencies through the most open list multi-member districts. Various parliament committees listen to experts and prepare legislation.

Significant parliamentary parties are Centre Party, Christian Democrats, Finns Party, Green League, Left Alliance, National Coalition Party, Social Democrats and Swedish People’s Party.

Cabinet

After parliamentary elections, the parties negotiate among themselves on forming a new cabinet (the Finnish Government), which then has to be approved by a simple majority vote in the parliament. The cabinet can be dismissed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, although this rarely happens (the last time in 1957), as the parties represented in the cabinet usually make up a majority in the parliament.

The cabinet exercises most executive powers and originates most of the bills that the parliament then debates and votes on. It is headed by the Prime Minister of Finland, and consists of him or her, other ministers, and the Chancellor of Justice. Each minister heads his or her ministry, or, in some cases, has responsibility for a subset of a ministry’s policy. After the prime minister, the most powerful minister is often the minister of finance.

As no one party ever dominates the parliament, Finnish cabinets are multi-party coalitions. As a rule, the post of prime minister goes to the leader of the biggest party and that of the minister of finance to the leader of the second biggest.

The Marin Cabinet is the incumbent 76th government of Finland. It took office on 10 December 2019.[123][124] The cabinet consists of a coalition formed by the Social Democratic Party, the Centre Party, the Green League, the Left Alliance, and the Swedish People’s Party.[125]

Law

The judicial system of Finland is a civil law system divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with jurisdiction over litigation between individuals and the public administration. Finnish law is codified and based on Swedish law and in a wider sense, civil law or Roman law. The court system for civil and criminal jurisdiction consists of local courts, regional appellate courts, and the Supreme Court. The administrative branch of justice consists of administrative courts and the Supreme Administrative Court. In addition to the regular courts, there are a few special courts in certain branches of administration. There is also a High Court of Impeachment for criminal charges against certain high-ranking officeholders.

Around 92% of residents have confidence in Finland’s security institutions.[126] The overall crime rate of Finland is not high in the EU context. Some crime types are above average, notably the high homicide rate for Western Europe.[127] A day fine system is in effect and also applied to offenses such as speeding. Finland has a very low number of corruption charges; Transparency International ranks Finland as one of the least corrupt countries in Europe.

Foreign relations

According to the 2012 constitution, the president (currently Sauli Niinistö) leads foreign policy in cooperation with the government, except that the president has no role in EU affairs.[128] In 2008, president Martti Ahtisaari was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[129]

Military

The Finnish Defence Forces consist of a cadre of professional soldiers (mainly officers and technical personnel), currently serving conscripts, and a large reserve. The standard readiness strength is 34,700 people in uniform, of which 25% are professional soldiers. A universal male conscription is in place, under which all male Finnish nationals above 18 years of age serve for 6 to 12 months of armed service or 12 months of civilian (non-armed) service.

Voluntary post-conscription overseas peacekeeping service is popular, and troops serve around the world in UN, NATO, and EU missions. Women are allowed to serve in all combat arms. In 2022, 1211 women entered voluntary military service.[130] The army consists of a highly mobile field army backed up by local defence units. With a high capability of military personnel,[131] arsenal[132] and homeland defence willingness, Finland is one of Europe’s militarily strongest countries.[133]

Sisu Nasu NA-110 tracked transport vehicle of the Finnish Army. Most conscripts receive training for warfare in winter, and transport vehicles such as this give mobility in heavy snow.

Finnish defence expenditure per capita is one of the highest in the European Union.[134] The branches of the military are the army, the navy, and the air force. The border guard is under the Ministry of the Interior but can be incorporated into the Defence Forces when required for defence readiness.

Finland became a member of NATO on 4 April 2023,[98] though it participated in the NATO Response Force before becoming a member. Finland also contributes to the EU Battlegroup.[135][136][137] Finland sent personnel to the Kosovo Force and the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan.[138][139]

Finland has one of the world’s most extensive welfare systems, one that guarantees decent living conditions for all residents. The welfare system was created almost entirely during the first three decades after World War II. Finland’s history has been harsher than the histories of the other Nordic countries, but not harsh enough to bar the country from following its path of social development.[140]

Human rights

Section 6 of the Finnish Constitution states: «No one shall be placed in a different position on situation of sex, age, origin, language, religion, belief, opinion, state of health, disability or any other personal reason without an acceptable reason».[141]

Finland has been ranked above average among the world’s countries in democracy,[142] press freedom,[143] and human development.[144] Amnesty International has expressed concern regarding some issues in Finland, such as the imprisonment of conscientious objectors, and societal discrimination against Romani people and members of other ethnic and linguistic minorities.[145][146]

Economy

As of 2022, Finland has the 16th highest nominal GDP per capita in the world according to the IMF.

In addition to the fact that Finland is one of the richest countries in the world, it is known for its well-developed welfare system, such as free education, and advanced health care system.

The largest sector of the economy is the service sector at 66% of GDP, followed by manufacturing and refining at 31%. Primary production represents 2.9%.[147] With respect to foreign trade, the key economic sector is manufacturing. The largest industries in 2007[148] were electronics (22%); machinery, vehicles, and other engineered metal products (21.1%); forest industry (13%); and chemicals (11%). The gross domestic product peaked in 2008. As of 2015, the country’s economy is at the 2006 level.[149][150] Finland is ranked as the 9th most innovative country in the Global Innovation Index in 2022.[151]

Finland has significant timber, mineral (iron, chromium, copper, nickel, and gold), and freshwater resources. Forestry, paper factories, and the agricultural sector are important for rural residents. The Greater Helsinki area generates around one-third of Finland’s GDP. Private services are the largest employer in Finland.

Finland’s climate and soils make growing crops a particular challenge. The country has severe winters and relatively short growing seasons that are sometimes interrupted by frost. However, because the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift Current moderate the climate, Finland contains half of the world’s arable land north of 60° north latitude. Annual precipitation is usually sufficient, but it occurs almost exclusively during the winter months, making summer droughts a constant threat. In response to the climate, farmers have relied on quick-ripening and frost-resistant varieties of crops, and they have cultivated south-facing slopes as well as richer bottomlands to ensure production even in years with summer frosts. Drainage systems are often needed to remove excess water. Finland’s agriculture has been efficient and productive—at least when compared with farming in other European countries.[140]

A treemap representing the exports of Finland in 2017

Forests play a key role in the country’s economy, making it one of the world’s leading wood producers and providing raw materials at competitive prices for the crucial wood processing industries. As in agriculture, the government has long played a leading role in forestry, regulating tree cutting, sponsoring technical improvements, and establishing long-term plans to ensure that the country’s forests continue to supply the wood-processing industries.[140]

As of 2008, average purchasing power-adjusted income levels are similar to those of Italy, Sweden, Germany, and France.[152] In 2006, 62% of the workforce worked for enterprises with less than 250 employees and they accounted for 49% of total business turnover.[153] The female employment rate is high. Gender segregation between male-dominated professions and female-dominated professions is higher than in the US.[154] The proportion of part-time workers was one of the lowest in OECD in 1999.[154] In 2013, the 10 largest private sector employers in Finland were Itella, Nokia, OP-Pohjola, ISS, VR, Kesko, UPM-Kymmene, YIT, Metso, and Nordea.[155] The unemployment rate was 6.8% in 2022.[156]

As of 2006, 2.4 million households reside in Finland. The average size is 2.1 persons; 40% of households consist of a single person, 32% two persons and 28% three or more persons. Residential buildings total 1.2 million, and the average residential space is 38 square metres (410 sq ft) per person. The average residential property without land costs €1,187 per sq metre and residential land €8.60 per sq metre. 74% of households had a car.[157] In 2017, Finland’s GDP reached €224 billion.[158]

Finland has the highest concentration of cooperatives relative to its population.[159] The largest retailer, which is also the largest private employer, S-Group, and the largest bank, OP-Group, in the country are both cooperatives.

Energy

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (January 2022) |

The free and largely privately owned financial and physical Nordic energy markets traded in NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe and Nord Pool Spot exchanges, have provided competitive prices compared with other EU countries. As of 2007, Finland has roughly the lowest industrial electricity prices in the EU-15.[161]

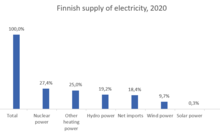

In 2006, the energy market was around 90 terawatt hours and the peak demand around 15 gigawatts in winter. This means that the energy consumption per capita is around 7.2 tons of oil equivalent per year. Industry and construction consumed 51% of total consumption, a relatively high figure reflecting Finland’s industries.[162][163] Finland’s hydrocarbon resources are limited to peat and wood. About 10–15% of the electricity is produced by hydropower.[164] In 2008, renewable energy (mainly hydropower and various forms of wood energy) was high at 31% compared with the EU average of 10.3% in final energy consumption.[165] A varying amount (5–17%) of electricity is imported from Sweden and Norway. As of February 2022, Finland’s strategic petroleum reserves held 200 days worth of net oil imports in the case of emergencies.[166]

Supply of electricity in Finland[167]

Finland has four privately owned nuclear reactors producing 18% of the country’s energy.[168] The fifth reactor – the world’s largest at 1600 MWe – is scheduled to be operational by 2023. The Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository is currently under construction at the Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant in the municipality of Eurajoki, on the west coast of Finland, by the company Posiva.[169]

Transport

A VR Class Sr2 locomotive. The state-owned VR operates a railway network serving all major cities in Finland.

Finland’s road system is utilized by most internal cargo and passenger traffic. The annual state operated road network expenditure of around €1 billion is paid for with vehicle and fuel taxes which amount to around €1.5 billion and €1 billion, respectively. Among the Finnish highways, the most significant and busiest main roads include the Turku Highway (E18), the Tampere Highway (E12), the Lahti Highway (E75), and the ring roads (Ring I and Ring III) of the Helsinki metropolitan area and the Tampere Ring Road of the Tampere urban area.[170]

The main international passenger gateway is Helsinki Airport, which handled about 21 million passengers in 2019 (5 million in 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic). Oulu Airport is the second largest with 1 million passengers in 2019 (300,000 in 2020), whilst another 25 airports have scheduled passenger services.[171] The Helsinki Airport-based Finnair, Blue1, and Nordic Regional Airlines, Norwegian Air Shuttle sell air services both domestically and internationally.

The Government annually spends around €350 million to maintain the 5,865-kilometre-long (3,644 mi) network of railway tracks. Rail transport is handled by the state-owned VR Group.[172] Finland’s first railway was opened in 1862,[173][174] and today it forms part of the Finnish Main Line, which is more than 800 kilometers long. Helsinki opened the world’s northernmost metro system in 1982.

The majority of international cargo shipments are handled at ports. Vuosaari Harbour in Helsinki is the largest container port in Finland; others include Kotka, Hamina, Hanko, Pori, Rauma, and Oulu. There is passenger traffic from Helsinki and Turku, which have ferry connections to Tallinn, Mariehamn, Stockholm and Travemünde. The Helsinki-Tallinn route is one of the busiest passenger sea routes in the world.[175] By passenger counts, the Port of Helsinki is the third busiest port in the world.[176]

Industry

Finland rapidly industrialized after World War II, achieving GDP per capita levels comparable to that of Japan or the UK at the beginning of the 1970s. Initially, most of the economic development was based on two broad groups of export-led industries, the «metal industry» (metalliteollisuus) and «forest industry» (metsäteollisuus). The «metal industry» includes shipbuilding, metalworking, the automotive industry, engineered products such as motors and electronics, and production of metals and alloys including steel, copper and chromium. Many of the world’s biggest cruise ships, including MS Freedom of the Seas and the Oasis of the Seas have been built in Finnish shipyards.[177]

[178] The «forest industry» includes forestry, timber, pulp and paper, and is often considered a logical development based on Finland’s extensive forest resources, as 73% of the area is covered by forest. In the pulp and paper industry, many major companies are based in Finland; Ahlstrom-Munksjö, Metsä Board, and UPM are all Finnish forest-based companies with revenues exceeding €1 billion. However, in recent decades, the Finnish economy has diversified, with companies expanding into fields such as electronics (Nokia), metrology (Vaisala), petroleum (Neste), and video games (Rovio Entertainment), and is no longer dominated by the two sectors of metal and forest industry. Likewise, the structure has changed, with the service sector growing. Despite this, production for export is still more prominent than in Western Europe, thus making Finland possibly more vulnerable to global economic trends.

In 2017, the Finnish economy was estimated to consist of approximately 2.7% agriculture, 28.2% manufacturing, and 69.1% services.[179] In 2019, the per-capita income of Finland was estimated to be $48,869. In 2020, Finland was ranked 20th on the ease of doing business index, among 190 jurisdictions.

Public policy

Flags of the Nordic countries and Åland from left to right: Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Åland

Finnish politicians have often emulated the Nordic model.[180] Nordics have been free-trading for over a century. The level of protection in commodity trade has been low, except for agricultural products.[180] Finland is ranked 16th in the 2008 global Index of Economic Freedom and ninth in Europe.[181] According to the OECD, only four EU-15 countries have less regulated product markets and only one has less regulated financial markets.[180] The 2007 IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook ranked Finland 17th most competitive.[182] The World Economic Forum 2008 index ranked Finland the sixth most competitive.[183]

The legal system is clear and business bureaucracy less than most countries.[181] Property rights are well protected and contractual agreements are strictly honoured.[181] Finland is rated the least corrupt country in the world in the Corruption Perceptions Index[184] and 13th in the Ease of doing business index.[185]

In Finland, collective labour agreements are universally valid. These are drafted every few years for each profession and seniority level, with only a few jobs outside the system. The agreement becomes universally enforceable provided that more than 50% of the employees support it, in practice by being a member of a relevant trade union. The unionization rate is high (70%), especially in the middle class (AKAVA, mostly for university-educated professionals: 80%).[180]

Tourism

In 2017, tourism in Finland grossed approximately €15.0 billion. Of this, €4.6 billion (30%) came from foreign tourism.[187] In 2017, there were 15.2 million overnight stays of domestic tourists and 6.7 million overnight stays of foreign tourists.[188] Tourism contributes roughly 2.7% to Finland’s GDP.[189]

Lapland has the highest tourism consumption of any Finnish region.[189] Above the Arctic Circle, in midwinter, there is a polar night, a period when the sun does not rise for days or weeks, or even months, and correspondingly, midnight sun in the summer, with no sunset even at midnight (for up to 73 consecutive days, at the northernmost point). Lapland is so far north that the aurora borealis, fluorescence in the high atmosphere due to solar wind, is seen regularly in the fall, winter, and spring. Finnish Lapland is also locally regarded as the home of Santa Claus, with several theme parks, such as Santa Claus Village and Santa Park in Rovaniemi.[190] Other significant tourist destinations in Lapland also include ski resorts (such as Levi, Ruka and Ylläs)[191] and sleigh rides led by either reindeer or huskies.[192][193]

Tourist attractions in Finland include the natural landscape found throughout the country as well as urban attractions. Finland contains 40 national parks (such as the Koli National Park in North Karelia), from the Southern shores of the Gulf of Finland to the high fells of Lapland. Outdoor activities range from Nordic skiing, golf, fishing, yachting, lake cruises, hiking, and kayaking, among many others. Bird-watching is popular for those fond of avifauna, however, hunting is also popular.

The most famous tourist attractions in Helsinki include the Helsinki Cathedral and the Suomenlinna sea fortress. The most well-known Finnish amusement parks include Linnanmäki in Helsinki and Särkänniemi in Tampere.[194] St. Olaf’s Castle (Olavinlinna) in Savonlinna hosts the annual Savonlinna Opera Festival,[195] and the medieval milieus of the cities of Turku, Rauma and Porvoo also attract spectators.[196] Commercial cruises between major coastal and port cities in the Baltic region play a significant role in the local tourism industry.

Demographics

Population by ethnic background in 2021[1][2]

Finnish (91.54%)

Other European (4.12%)

Asian (2.77%)

Others (0.48%)

The population of Finland is currently about 5.5 million. The current birth rate is 10.42 per 1,000 residents, for a fertility rate of 1.49 children born per woman,[197] one of the lowest in the world, significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1. In 1887 Finland recorded its highest rate, 5.17 children born per woman.[198] Finland has one of the oldest populations in the world, with a median age of 42.6 years.[199] Approximately half of voters are estimated to be over 50 years old.[200][82][201][202] Finland has an average population density of 18 inhabitants per square kilometre. This is the third-lowest population density of any European country, behind those of Norway and Iceland, and the lowest population density of any European Union member country. Finland’s population has always been concentrated in the southern parts of the country, a phenomenon that became even more pronounced during 20th-century urbanization. Two of the three largest cities in Finland are situated in the Greater Helsinki metropolitan area—Helsinki and Espoo.[203] In the largest cities of Finland, Tampere holds the third place after Helsinki and Espoo while also Helsinki-neighbouring Vantaa is the fourth. Other cities with population over 100,000 are Turku, Oulu, Jyväskylä, Kuopio, and Lahti.

Finland’s immigrant population is growing.[204] As of 2021, there were 469,633 people with a foreign background living in Finland (8.5% of the population), most of whom are from the former Soviet Union, Estonia, Somalia, Iraq and former Yugoslavia.[205][206] The children of foreigners are not automatically given Finnish citizenship, as Finnish nationality law practices and maintain jus sanguinis policy where only children born to at least one Finnish parent are granted citizenship. If they are born in Finland and cannot get citizenship of any other country, they become citizens.[207] Additionally, certain persons of Finnish descent who reside in countries that were once part of Soviet Union, retain the right of return, a right to establish permanent residency in the country, which would eventually entitle them to qualify for citizenship.[208] 442,290 people in Finland in 2021 were born in another country, representing 8% of the population. The 10 largest foreign born groups are (in order) from Russia, Estonia, Sweden, Iraq, China, Somalia, Thailand, Vietnam, Serbia and India, with Turkey dropping to 11th place from last year.[209]

Language

Municipalities of Finland:

unilingually Finnish

bilingual with Finnish as majority language, Swedish as minority language

bilingual with Swedish as majority language, Finnish as minority language

unilingually Swedish

bilingual with Finnish as majority language, Sami as minority language

Finnish and Swedish are the official languages of Finland. Finnish predominates nationwide while Swedish is spoken in some coastal areas in the west and south (with towns such as Ekenäs,[210] Pargas,[211] Närpes,[211] Kristinestad,[212] Jakobstad[213] and Nykarleby.[214]) and in the autonomous region of Åland, which is the only monolingual Swedish-speaking region in Finland.[215] The native language of 87.3% of the population is Finnish,[216][217] which is part of the Finnic subgroup of the Uralic language. The language is one of only four official EU languages not of Indo-European origin, and has no relation through descent to the other national languages of the Nordics. Conversely, Finnish is closely related to Estonian and Karelian, and more distantly to Hungarian and the Sami languages.

Swedish is the native language of 5.2% of the population (Swedish-speaking Finns).[218] Swedish is a compulsory school subject and general knowledge of the language is good among many non-native speakers.[219] Likewise, a majority of Swedish-speaking non-Ålanders can speak Finnish.[220] The Finnish side of the land border with Sweden is unilingually Finnish-speaking. The Swedish across the border is distinct from the Swedish spoken in Finland. There is a sizeable pronunciation difference between the varieties of Swedish spoken in the two countries, although their mutual intelligibility is nearly universal.[221]

Finnish Romani is spoken by some 5,000–6,000 people; Romani and Finnish Sign Language are also recognized in the constitution. There are two sign languages: Finnish Sign Language, spoken natively by 4,000–5,000 people,[222] and Finland-Swedish Sign Language, spoken natively by about 150 people. Tatar is spoken by a Finnish Tatar minority of about 800 people whose ancestors moved to Finland mainly during Russian rule from the 1870s to the 1920s.[223]

The Sami languages have an official status in parts of Lapland, where the Sami, numbering around 7,000,[224] are recognized as an indigenous people. About a quarter of them speak a Sami language as their mother tongue.[225] The Sami languages that are spoken in Finland are Northern Sami, Inari Sami, and Skolt Sami.[note 5] The rights of minority groups (in particular Sami, Swedish speakers, and Romani people) are protected by the constitution.[226] The Nordic languages and Karelian are also specially recognized in parts of Finland.

The largest immigrant languages are Russian (1.6%), Estonian (0.9%), Arabic (0.7%), English (0.5%) and Somali (0.4%).[227]

English is studied by most pupils as a compulsory subject from the first grade (at seven years of age), formerly from the third or fifth grade, in the comprehensive school (in some schools other languages can be chosen instead).[228][229][230][231] German, French, Spanish and Russian can be studied as second foreign languages from the fourth grade (at 10 years of age; some schools may offer other options).[232]

Largest cities

Religion

Religions in Finland (2019)[233]

Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (68.72%)

Orthodox Church (1.10%)

Other Christian (0.93%)

Other religions (0.76%)

Unaffiliated (28.49%)

With 3.9 million members,[234] the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland is Finland’s largest religious body; at the end of 2019, 68.7% of Finns were members of the church.[235] The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland has seen its share of the country’s population declining by roughly one percent annually in recent years.[235] The decline has been due to both church membership resignations and falling baptism rates.[236][237] The second largest group, accounting for 26.3% of the population[235] in 2017, has no religious affiliation. A small minority belongs to the Finnish Orthodox Church (1.1%). Other Protestant denominations and the Roman Catholic Church are significantly smaller, as are the Jewish and other non-Christian communities (totalling 1.6%). The Pew Research Center estimated the Muslim population at 2.7% in 2016.[238]

Finland’s state church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia from 1809 to 1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland was established. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919, and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution. The main Lutheran and Orthodox churches have special roles such as in state ceremonies and schools.[239]

In 2016, 69.3% of Finnish children were baptized[240] and 82.3% were confirmed in 2012 at the age of 15,[241] and over 90% of the funerals are Christian. However, the majority of Lutherans attend church only for special occasions like Christmas ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. The Lutheran Church estimates that approximately 1.8% of its members attend church services weekly.[242] The average number of church visits per year by church members is approximately two.[243]

According to a 2010 Eurobarometer poll, 33% of Finnish citizens responded that they «believe there is a God»; 42% answered that they «believe there is some sort of spirit or life force»; and 22% that they «do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force».[244] According to ISSP survey data (2008), 8% consider themselves «highly religious», and 31% «moderately religious». In the same survey, 28% reported themselves as «agnostic» and 29% as «non-religious».[245]

Health

Life expectancy was 79 years for men and 84 years for women in 2017.[246] The under-five mortality rate was 2.3 per 1,000 live births in 2017, ranking Finland’s rate among the lowest in the world.[247] The fertility rate in 2014 stood at 1.71 children born/per woman and has been below the replacement rate of 2.1 since 1969.[248] With a low birth rate women also become mothers at a later age, the mean age at first live birth being 28.6 in 2014.[248] A 2011 study published in The Lancet medical journal found that Finland had the lowest stillbirth rate out of 193 countries.[249]

There has been a slight increase or no change in welfare and health inequalities between population groups in the 21st century. Lifestyle-related diseases are on the rise. More than half a million Finns suffer from diabetes, type 1 diabetes being globally the most common in Finland. Many children are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The number of musculoskeletal diseases and cancers are increasing, although the cancer prognosis has improved. Allergies and dementia are also growing health problems in Finland. One of the most common reasons for work disability are due to mental disorders, in particular depression.[250] The suicide rates were 13 per 100 000 in 2017, close to the North European average.[251] Suicide rates are still among the highest among developed countries in the OECD.[252]

There are 307 residents for each doctor.[253] About 19% of health care is funded directly by households and 77% by taxation.

In April 2012, Finland was ranked second in Gross National Happiness in a report published by The Earth Institute.[254] Since 2012, Finland has every time ranked at least in the top 5 of world’s happiest countries in the annual World Happiness Report by the United Nations,[255][256][257] as well as ranking as the happiest country in 2018.[258]

Education and science

Most pre-tertiary education is arranged at the municipal level. Around 3 percent of students are enrolled in private schools (mostly specialist language and international schools).[260] Formal education is usually started at the age of 7. Primary school takes normally six years and lower secondary school three years.

The curriculum is set by the Ministry of Education and Culture and the Education Board. Education is compulsory between the ages of 7 and 18. After lower secondary school, graduates may apply to trade schools or gymnasiums (upper secondary schools). Trade schools offer a vocational education: approximately 40% of an age group choose this path after the lower secondary school.[261] Academically oriented gymnasiums have higher entrance requirements and specifically prepare for Abitur and tertiary education. Graduation from either formally qualifies for tertiary education.

In tertiary education, two mostly separate and non-interoperating sectors are found: the profession-oriented polytechnics and the research-oriented universities. Education is free and living expenses are to a large extent financed by the government through student benefits. There are 15 universities and 24 Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) in the country.[262][263] The University of Helsinki is ranked 75th in the Top University Ranking of 2010.[264] Other reputable universities of Finland include Aalto University in Espoo, both University of Turku and Åbo Akademi University in Turku, University of Jyväskylä, University of Oulu, LUT University in Lappeenranta and Lahti, University of Eastern Finland in Kuopio and Joensuu, and Tampere University.[265]

The World Economic Forum ranks Finland’s tertiary education No. 1 in the world.[266] Around 33% of residents have a tertiary degree, similar to Nordics and more than in most other OECD countries except Canada (44%), United States (38%) and Japan (37%).[267] In addition, 38% of Finland’s population has a university or college degree, which is among the highest percentages in the world.[268][269] Adult education appears in several forms, such as secondary evening schools, civic and workers’ institutes, study centres, vocational course centres, and folk high schools.[140]

More than 30% of tertiary graduates are in science-related fields. Forest improvement, materials research, environmental sciences, neural networks, low-temperature physics, brain research, biotechnology, genetic technology, and communications showcase fields of study where Finnish researchers have had a significant impact.[270] Finland is highly productive in scientific research. In 2005, Finland had the fourth most scientific publications per capita of the OECD countries.[271] In 2007, 1,801 patents were filed in Finland.[272]

Culture

Literature

Written Finnish could be said to have existed since Mikael Agricola translated the New Testament into Finnish during the Protestant Reformation, but few notable works of literature were written until the 19th century and the beginning of a Finnish national Romantic Movement. This prompted Elias Lönnrot to collect Finnish and Karelian folk poetry and arrange and publish them as the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic. The era saw a rise of poets and novelists who wrote in Finnish, notably the national writer of Finland, Aleksis Kivi (The Seven Brothers), and Minna Canth, Eino Leino, and Juhani Aho. Many writers of the national awakening wrote in Swedish, such as the national poet J. L. Runeberg (The Tales of Ensign Stål) and Zachris Topelius.

After Finland became independent, there was a rise of modernist writers, most famously the Swedish-speaking poet Edith Södergran. Finnish-speaking authors explored national and historical themes. Most famous of them were Frans Eemil Sillanpää, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1939, historical novelist Mika Waltari, and Väinö Linna with his The Unknown Soldier and Under the North Star trilogy. Beginning with Paavo Haavikko, Finnish poetry adopted modernism. Besides Lönnrot’s Kalevala and Waltari, the Swedish-speaking Tove Jansson, best known as the creator of The Moomins, is the most translated Finnish writer;[273] her books have been translated into more than 40 languages.[274]

Visual arts, design, and architecture

The visual arts in Finland started to form their characteristics in the 19th century when Romantic nationalism was rising in autonomic Finland. The best known Finnish painters, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, started painting in a naturalist style but moved to national romanticism. Other notable painters of the era include Pekka Halonen, Eero Järnefelt, Helene Schjerfbeck and Hugo Simberg. In the late 20th century, the homoerotic art of Touko Laaksonen, pseudonym Tom of Finland, found a worldwide audience.[275][276]

Finland’s best-known sculptor of the 20th century was Wäinö Aaltonen, remembered for his monumental busts and sculptures. The works of Eila Hiltunen and Laila Pullinen exemplifies the modernism in sculpture.