A list of movies I would recommend that have titles beginning with the word «the» (The Lion King, The Lord of the Rings, etc.).

avg. score: 110 of 440 (25%)

required scores: 1, 36, 86, 117, 157

How many have you seen?

The Great Train Robbery (1903)

The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912)

The Birth of a Nation (1915)

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Kid (1921)

The Sheik (1921)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923)

The Ten Commandments (1923)

The Navigator (1924)

The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

The Freshman (1925)

The Gold Rush (1925)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Lost World (1925)

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926)

The General (1926)

The King of Kings (1927)

The Circus (1928)

The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Skeleton Dance (1929)

The Public Enemy (1931)

The Blood of a Poet (1932)

The Most Dangerous Game (1932)

The Mummy (1932)

The Invisible Man (1933)

The Black Cat (1934)

The Thin Man (1934)

ADVERTISEMENT

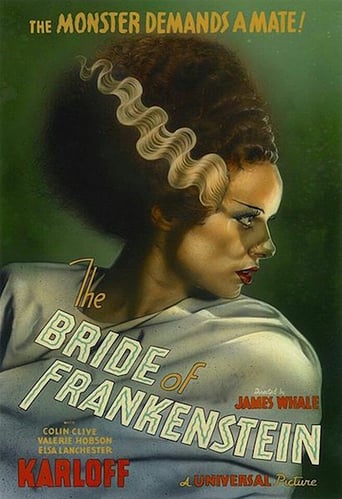

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

The 39 Steps (1935)

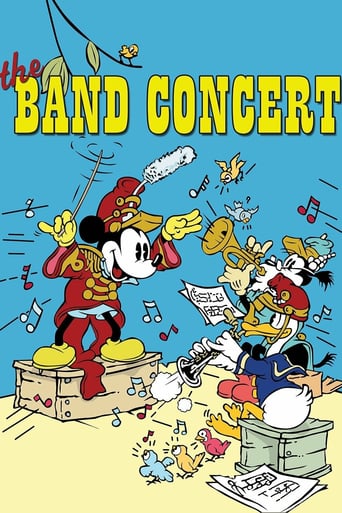

The Band Concert (1935)

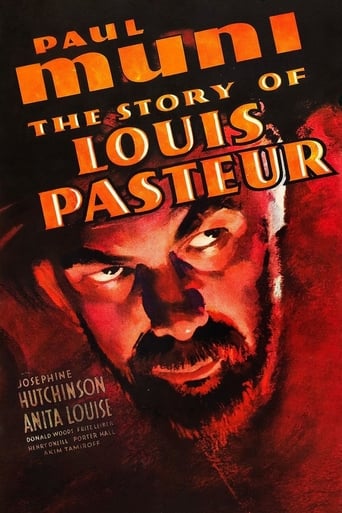

The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936)

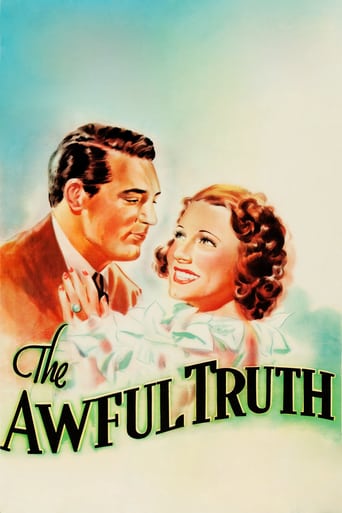

The Awful Truth (1937)

The Life of Emile Zola (1937)

The Tale of the Fox (1937)

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939)

The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

Newsletter ·

Help/Contact ·

Privacy ·

Copyright Claim

© 2023 App Spring, Inc.

·

This product uses the TMDb API but is not endorsed or certified by TMDb.

|

|

Seen It — Movies & TV Android & iOS |

Seen It is a new app from the creators of List Challenges. You can view movies and shows in one place and filter by streaming provider, genre, release year, runtime, and rating (Rotten Tomatoes, Imdb, and/or Metacritic). Also, you can track what you’ve seen, want to see, like, or dislike, as well as track individual seasons or episodes of shows. In addition, you can see the most watched/liked stuff amongst your friends. Learn more at SEENIT.FUN

Here is a list of 100 random movies (current, cult, classic, and foreign) which start with the word «The».

avg. score: 36 of 138 (26%)

required scores: 1, 19, 28, 40, 55

How many have you seen?

The Abyss (1989)

The Act of Killing (2012)

The Adventures of Dollie (1908)

The Alphabet (1968)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)

The Avengers (2012)

The Babadook (2014)

The Battle of Algiers (1966)

The Battle of Culloden

The Big Lebowski (1998)

The Black Imp (1905)

The Blair Witch Project (1999)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Blob (1988)

The Book Thief (2013)

The Bridge (2006)

The Browning Version (1951)

The Bucket List (2007)

The Cabin in the Woods (2012)

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

The Cat With Hands (2001)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005)

The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (2008)

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010)

The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

The Conformist (1970)

The Conversation (1974)

The Dark Knight (2008)

The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

ADVERTISEMENT

The Death of Louis XIV (2016)

The Departed (2006)

The Descent (2005)

The Devil (1972)

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972)

The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

The Elephant Man (1980)

The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches on (1987)

The Evil Dead (1981)

The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895)

The Exorcist (1973)

The Fall (2008)

Newsletter ·

Help/Contact ·

Privacy ·

Copyright Claim

© 2023 App Spring, Inc.

·

This product uses the TMDb API but is not endorsed or certified by TMDb.

|

|

Seen It — Movies & TV Android & iOS |

Seen It is a new app from the creators of List Challenges. You can view movies and shows in one place and filter by streaming provider, genre, release year, runtime, and rating (Rotten Tomatoes, Imdb, and/or Metacritic). Also, you can track what you’ve seen, want to see, like, or dislike, as well as track individual seasons or episodes of shows. In addition, you can see the most watched/liked stuff amongst your friends. Learn more at SEENIT.FUN

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Words | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Antonio Calvache |

| Edited by | Leslie Jones |

| Music by | Marcelo Zarvos |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | CBS Films |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million[1] |

| Box office | $16.4 million[1] |

The Words is a 2012 American mystery romantic drama film, written and directed by Brian Klugman and Lee Sternthal in their directorial debut. It stars Bradley Cooper, Zoe Saldana, Olivia Wilde, Jeremy Irons, Ben Barnes, Dennis Quaid, and Nora Arnezeder. Cooper, a childhood friend of Klugman and Sternthal from Philadelphia, was also the executive producer.[2]

Plot[edit]

Clayton Hammond is doing a reading of his new book, The Words. He begins reading from the book, which is centered on the fictional character Rory Jansen, an aspiring writer who lives in NYC with his girlfriend, Dora. Rory borrows some money from his father, gets a job as a mail supervisor at a literary agency, and attempts to sell his first novel, which is repeatedly rejected by publishers.

After living together for some time, Rory and Dora marry and, during their honeymoon in Paris, Dora buys Rory an old briefcase he was admiring in an antiques store. Returning to America and having his book rejected again, Rory finds an old but masterfully written manuscript in the briefcase with a central character named Jack.

Rory types the manuscript into his laptop to know what it feels like to write something truly great, even if it’s only pretend. Later, while using the laptop, Dora happens upon the novel, reading it. She mistakenly assumes that Rory wrote it and convinces him to give it to a publisher at work, Joseph Cutler. After a few months Cutler finally reads it and offers Rory a contract which he accepts. The book is a hit and Rory becomes famous.

At this point, Hammond takes a break from the reading and goes backstage, where he is introduced by his agent to Daniella, a student and amateur writer who wants to interview him. She notes that he is separated from his wife, although he still wears a wedding ring. Hammond agrees to meet her after the ceremony and returns to the stage, where he continues the reading.

The second part details Rory’s encounter with an old man in Central Park, who reveals himself as the true author of the manuscript, based on his life in Paris.

When he was a young man and stationed in France with the U.S. Army in the final days of World War II, he fell in love with Celia, a French waitress. They eventually married and had a daughter, who later died.

Unable to cope with the loss, Celia left him and moved to her parents’ home in the country. He then used his pain as inspiration to write the manuscript, which he took to Celia while visiting her. She found the story so moving she returned to him. However, she unintentionally left the manuscript in a briefcase on the train after her trip back to Paris, losing it. Because of this, their reconciliation was short-lived, and they divorced soon afterwards.

The public reading ends and Hammond tells his fans they must buy the book to learn how it ends. Daniella then accompanies Hammond back to his apartment where she pressures him into telling her the ending. Hammond explains that Rory tells the truth about the creation of the story, first to his wife and then to Cutler. He also tells him he wants to credit the old man as the true author. Cutler angrily advises against this as it would severely damage both their reputations, and recommends giving the old man a share of the book’s profits instead.

Rory then seeks out the old man to pay him and finds him working in a plant nursery. He refuses the money, then tells about seeing Celia once more. While riding the train to work, years after his divorce, he spotted her with a new husband and a young son at a train station. The old man points out that people always move on from their mistakes, and Rory will too.

Daniella continues to pressure Hammond for more details. He reveals that the old man died not long after Rory’s second meeting with him along with the secret of the manuscript’s true author. Daniella deduces that The Words is actually an autobiographical book, with Rory as Hammond’s surrogate.

She kisses him, reassuring him that people move on from their mistakes, but he pulls away, telling her that there is a fine line between life and fiction. The film flashes back to Rory and Dora in their tiny kitchen, as Rory whispers «I’m sorry» in her ear.

Cast[edit]

- Bradley Cooper[3][4] as Rory Jansen[5]

- Zoe Saldana[4] as Dora Jansen[6]

- Olivia Wilde[4][7] as Daniella[8]

- Jeremy Irons[3] as The Old Man

- Ben Barnes[8] as the Young Man[5]

- Dennis Quaid[4] as Clay Hammond[5]

- J. K. Simmons[8] as Mr. Jansen[6]

- John Hannah[8] as Richard Ford

- Nora Arnezeder as Celia

- Željko Ivanek as Joseph Cutler

- Michael McKean as Nelson Wyllie

- Ron Rifkin as Timothy Epstein

- Brian Klugman as Jason Rosen

- Liz Stauber as Camy Rosen

- Lee Sternthal as Brett Copsey

Themes[edit]

The script includes several references to writer Ernest Hemingway. Rory and Dora view a commemorative plaque to Hemingway during their Paris honeymoon.[9] The plot device of Celia leaving her husband’s manuscript in a leather satchel on a train is reminiscent of a similar episode in Hemingway’s life, when his first wife Hadley left a briefcase containing all of his writings up to 1922 on a train; the manuscripts were never recovered.[10][11] Roger Ebert points out the similarity between the name of the character «The Old Man» and Hemingway’s novel The Old Man and the Sea, and the commonality of the name Dora among the wives of novelists.[11]

Allegations of similarity to German novel[edit]

According to some Swiss newspapers, the plot of The Words is similar to that of the 2004 novel Lila Lila by Martin Suter (made into the German film Lila, Lila released in 2009), which is also about a young unsuccessful author who discovers an old manuscript, is pushed by his girlfriend into publishing it, becomes enormously successful, is later confronted by an old man who is (or in that case, knows) the original author, and then publishes a second book about how this all happened.

Brian Klugman and Lee Sternthal say that they knew nothing of Suter, his work, or Lila Lila. They had the idea and began writing The Words in 1999, years before Lila Lila was published. Together they attended the 2000 Sundance Screenwriter’s Lab with their original screenplay.[2][12][13]

Production[edit]

Filming[edit]

Filming began in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, on June 7, 2011[14] for a period of 25 days.[2] The Montreal location was used because it could pass as both Paris and New York.[15]

Release[edit]

The Words had its world premiere at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival.[16] Prior to its official premiere and following a press and industry screening at Sundance, the film was purchased by CBS Films for $2 million with a $1.5 million print and advertising commitment.[16]

The Words grossed nearly $11.5 million in North America and $1.7 million worldwide, against a production budget of $6 million.[17]

Reception[edit]

The Words received mostly negative reviews from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes it has a 22% rating based on 117 reviews with an average rating of 4.6/10 and the consensus stating: «Neither as clever nor as interesting as it appears to think it is, The Words maroons its talented stars in an overly complex, dramatically inert literary thriller that’s ultimately a poor substitute for a good book».[18] At Metacritic, the film received 37 out of 100 with «generally unfavorable reviews» from 30 critics.[19] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of «B» on an A+ to F scale.[20]

Jen Chaney from The Washington Post gave the film 1.5 out of 5 stars, saying it «is a well-acted but narratively limp indie that’s undermined by a failure to connect emotionally with its audience».[21] Chris Pandolfi from At A Theater Near You praised the film, saying that while its «ambiguity is unlikely to be appreciated by everyone,» it «deserves to be structurally, emotionally, and thematically analyzed».[22] Stephen Holden of The New York Times also praised the film as «a clever, entertaining yarn».[10]

References[edit]

- ^ a b «The Words (2012) — Financial Information». The Numbers. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Kaufman, Amy (September 7, 2012). «Bradley Cooper helps his friends get ‘The Words’ out». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Newman, Nick (2011-02-10). «Bradley Cooper and Jeremy Irons Starring Together in ‘The Words’«. TheFilmStage.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ a b c d «Zoe Saldana, Olivia Wilde, Bradley Cooper and Dennis Quaid Join ‘The Words’«. Shockya.com. 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ a b c Labrecque, Jeff (28 January 2012). «Sundance: ‘The Words’ Bradley Cooper on being ‘creatively stymied’ in his own career». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ a b Horn, John (21 January 2012). «Sundance 2012: Bradley Cooper gets naughty in ‘The Words’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ «Olivia Wilde Joins Bradley Cooper in ‘The Words’«. FilmoFilia.com. 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ a b c d «Olivia Wilde, Ben Barnes, J.K. Simmons & John Hannah Join Bradley Cooper In ‘The Words’«. indieWIRE. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Pols, Mary (September 6, 2012). «The Words: Oh What a Tangled Web They Weave». Time. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen (September 7, 2012). «A Few Hungry Writers, Playing Fast and Loose». The New York Times. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (September 5, 2012). «Reviews: The Words». roberebert.com. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Philippe Zweifel (2012-09-27). «Lila Worte». Tages Anzeiger. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ^ Sarah Fux (2012-09-27). «Wie viel Suter steckt in «The Words»?». Zürcher Studierendenzeitung. Archived from the original on 2014-05-02. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ^ «‘The Words’ filming location in Montreal on June 7, 2011″. OnLocationVacations.com. 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Meehan, Jay (20 January 2012). «Sundance Screenwriters’ Lab helped shape ‘The Words’«. The Park Record. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ a b Miller, Daniel and Jay A. Fernandez (January 22, 2012). «Sundance 2012: Bradley Cooper’s ‘The Words’ Sells to CBS Films After Heated Bidding». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ «The Words». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ «The Words Movie Reviews». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ «The Words Review». Metacritic. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ^ «Home». CinemaScore. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ Chaney, Jen (2012-09-07). «Finding A Voice in Another’s Tragedy». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2013-02-05. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Pandolfi, Chris (2012-09-07). «The Words (2012) Review by Chris Pandolfi». At A Theater Near You. Archived from the original on 2012-09-21. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- The Words at IMDb

- The Words at AllMovie

The Taking of Pelham 123

(Joseph H Sargent, 1974)

In Sargent’s ingenious, headlong thriller about a New York subway-train hijack, transit detective Walther Matthau handles things ably above ground, but the real attractions are down below: the gang of ruthless hijackers code-named, Reservoir Dogs-style, after colours, and led by the implacable Robert Shaw in one of his nastiest roles.

The Tale of the Fox

(Irene and Wladyslaw Starewicz, 1930)

The Starewiczs took ten years to complete their astounding puppet-animation fairy tale, Le Roman de la Renard. In essence, it’s a very European treatment of the adventures of a deceitful fox — ie, there are no cute moral lessons here. But it’s the stop-motion stuffed animals and other strange beasties that make this film so watchable; nothing made since even comes close.

The Talented Mr Ripley

(Anthony Minghella, 1999)

A psychological thriller with a touch of grown-up class: Anthony Minghella brought his formidable directorial intelligence to this disturbing story of a conman’s most dangerous weapon: a capacity, almost like that of a Method actor, for self-delusion. Jude Law is the handsome playboy, into whose affections the unstable young flatterer Ripley (Matt Damon) insinuates himself.

Tampopo

(Juzo Itami, 1985)

A Japanese one-off that speaks the international language of food and finds the richness of the world in a bowl of noodles. Ostensibly the comic tale of a widow’s quest for culinary distinction, this throws all manner of flavours into the mix — from erotic interludes to western parodies — but never over-eggs the pudding.

The Taste of Cherry

(Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

Kiarostami produced his masterpiece with this elegant, spare, humanist work. A middle-aged man drives around the itinerant labour-markets of Tehran. What does he want? To commit suicide, and to efface himself utterly from the world. So needs a shovel-wielding labourer to fill in the shallow grave in which he will lie, after swallowing poison. An old man tries to talk him out of it, passionately praising the fruits of God’s bounty.

Taxi Driver

(Martin Scorsese, 1976)

All movie lunatics must be forever judged against Travis Bickle, whose nightly encounter with Gotham’s depravity spurs his deranged quest to save a young prostitute from the underworld. The mayhem comes with an ironic coda that almost makes you wonder if it was all a bad dream.

Team America: World Police

(Trey Parker, Matt Stone, 2004)

Magnificently funny, bad-taste puppet satire on American hubris, and a clever deconstruction of Hollywood action pictures to boot. Team America are the A-team of US foreign policy, kicking terrorist ass. Like the Thunderbirds, they move about in a funny head-bobbing way, but they can fight and have sex. The film has the greatest vomit scene in Hollywood history.

Tears of the Black Tiger

(Wisit Sasanatieng, 2000)

A recklessly inventive, vibrantly stylised Thai western that looks like it was made by someone who had never seen a real one. But what a beautiful concoction it is, with its saturated colours, ingenious gunfights, 1940s love songs and absurd extremes of melodrama. It’s both strange and familiar, like an acid trip at a village fete.

Ten Things I Hate About You

(Gil Junger, 1999)

Updated Shakespearean teen comedies were the staple of the late 90s, and this one fares well with the pivotal casting of an unknown Heath Ledger in the debut role of arrogant Patrick Verona, whose baiting of the phenomenally hostile Julia Stiles’ Kat is worthy homage to the sizzling chemistry between Taylor and Burton (who were paired in the 1967 version of Taming of the Shrew).

The Terminator

(James Cameron, 1983)

The movie that made Arnold Schwarzenegger an icon, in transition from body-builder beefcake to grade-A action star. He is the implacable cyborg sent from a totalitarian future to kill the mother of a future resistance fighter. James Cameron’s direction is virile and stylish and Arnie is magnificent with his absurd body, treacle-thick voice and an infinitesmal touch of drollery that none of his subsequent attempts at out-and-out comedy ever equalled.

Terminator 2: Judgment Day

(James Cameron, 1991)

He said he’d be back, and here he is: Arnold Schwarzenegger returns as the time-traveling cyborg in a rare sequel that tops the first, with bigger stunts, bigger effects and a bigger story. This time he’s been sent back to the 1990s to protect future saviour of humanity Edward Furlong and his long-suffering mum Linda Hamilton from Robert Patrick’s new shape-shifting Terminator model.

Tetsuo: The Iron Man

(Shinya Tsukamoto, 1989)

Industrial-strength metalhead film-making as a salaryman office drone becomes «infected» by bizarre mechanical growths after being involved in a hit and run incident. This short feature practically attacks the viewer with grotesque imagery and a screeching soundtrack, but it displays great imagination and ingenuity at every turn.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

(Tobe Hooper, 1974)

«Who Will Survive… and What Will Be Left of Them?» Hooper, in Hitchcock/Jaws style, holds his cannibalistic monsters back for a full 40 minutes of agonising build-up, and then unleashes them with sledgehammer suddenness (and with an actual sledgehammer, naturally). Notable for its lack of blood, its unnerving sound-design, and the best title ever.

Thelma & Louise

(Ridley Scott, 1991)

The ultimate chick-flick road-trip movie, this one has it all: feisty gun toting Southern women, murder, rape, armed robbery, a Thunderbird convertible on the open road, a killer soundtrack, a high speed car chase, and the world’s introduction to Brad Pitt’s torso. Teenage slumber parties couldn’t ask for a more complete package.

There’s Something About Mary

(Peter and Bobby Farrelly, 1998)

The Farrelly brothers made themselves the kings of the non-PC 1990s with their distinctive brand of outrageous and offensive comedy, which, apparently, they alone were allowed to perpetrate with impunity. A guy finds that he is still in love with a girl with whom he had a catastrophic prom date in high school. This is Mary, played by Cameron Diaz: whose beaming face, framed by a semen-encrusted hairstyle, became a classic image.

These Are the Damned

(Joseph Losey, 1963)

Unusually bleak sci-fi horror from Hammer studios with American director Losey on board — he, at the time, was living a life of self-imposed exile to avoid the McCarthy witch-hunt. Radioactive kids bring death to whoever the come into contact with. The downbeat ending is memorable as are the twisted Elisabeth Frink statues that populate the scenery.

They Live by Night

(Nicholas Ray, 1948)

The finest American directorial debut after Citizen Kane, Ray’s adaptation of Edward Anderson’s 1935 Bonnie-and-Clyde novel Thieves Like Us outlines the poetic humanism and romantic fatalism that would characterise nearly all of his later work. Farley Granger and Cathy O’Donnell are cinema’s most affecting doomed young lovers.

The Thief of Bagdad

(Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, Tim Whelan, 1940)

An English production, with some shooting in Hollywood, this was the Korda Brothers’ view of the Arabian Nights. It has Sabu, Conrad Veidt, June Duprez and Rex Ingram as the mythical figures. But it’s the magic that touches you, and one of the magicians was Michael Powell.

The Thin Blue Line

(Errol Morris, 1988)

Morris’s riveting and groundbreaking documentary — it ignored all the then-prevalent rules of the form by using speculation and reconstructed sequences — secured the release of its incarcerated protagonist by pressuring the real killer to acknowledge his crimes. The injustice of it all will have you screaming with anger.

The Thing (From Another World)

(Christian Nyby, 1951)

It’s supposed that Howard Hawks directed some of this and Ben Hecht provided some uncredited rewrites; it certainly has some of their fingerprints on it. Snappy, overlapping dialogue fills the air as an isolated team of scientists battle a humanoid alien plant creature — «An intellectual carrot, whatever next?» One of the earliest and best alien invasion movies.

Things to Come

(William Cameron Menzies, 1936)

It has to be said that some of the actors here aren’t taking this as seriously as they should, which partly diminishes the impact HG Wells’ predictive science fiction. It’s often left to the stunning sets and special effects to carry the movie, a task they handle with great style.

The Third Man

(Carol Reed, 1949)

Still a contender for the finest British movie ever made, and a home-made film noir to measure up to the best of Hollywood (or France, for that matter) — even if it has American stars and was shot in Vienna. It’s filled with unforgettable movie moments — Anton Karas’ zither theme tune, Orson Welles’ emergence out of the shadows, his famous «cuckoo clock» speech on the Ferris wheel, the sewer chase, the closing funeral scene. Our hero, Joseph Cotten, a pulp western novelist, is repeatedly warned about mixing fact and fiction as he sifts through the rubble of postwar Vienna investigating the death of his old friend Harry Lime (Welles). As Cotten gradually pieces the story together, a very different picture of Lime starts to emerge, along with unpalatable political and economic truths. It’s a captivating mystery, soaked in atmosphere, filled with memorable characters and beautifully filmed in black and white. But beneath the surface, Graham Greene’s script engineers a multitude of confrontations: American optimism versus European fatalism; childhood versus adulthood; money versus humanity; friendship versus patriotism; fact versus fiction. Very few films bear so much weight so gracefully.

Steve Rose

The Thirty Nine Steps

(Alfred Hitchcock, 1935)

The classic Boy’s Own adventure from John Buchan’s novel rattles along at a furious pace. Robert Donat is the innocent murder suspect Richard Hannay, chased by the police from London to the Scottish Borders and back, while he pursues dastardly spies and dallies with Madeleine Carroll: a thriller brimming with wit and verve.

Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould

(François Girard, 1993)

Endlessly fertile bio-pic of the legendarily eccentric pianist, that takes its cue from Gould’s famous Goldberg Variations treatment. Canadian director Girard incorporates animation, radio, and straight recreation to tell Gould’s story; Colm Feore puts in a career-best performance in the title role.

This Is Spinal Tap

(Rob Reiner, 1984)

A gem which went almost unnoticed on its initial cinema release, but accumulated word-of-mouth cult status through video rental. Tap created the «mockumentary» genre with its wonderful homage to ageing Brit rockers in the US, a mix of the Rolling Stones, Black Sabbath and unknown exports like Foghat. Every frame, every line, is a joy.

This Sporting Life

(Lindsay Anderson, 1963)

Who needs Marlon Brando when you’ve got Richard Harris? Lindsay Anderson’s blistering adaptation of David Storey’s novel about a miner-turned-rugby league professional is galvanised by Harris’ extraordinary performance as Frank Machin. Harris combines brutality and machismo with an unexpected sensitivity, with excellent support from Rachel Roberts as the widow with whom he has such a destructive relationship.

The Thomas Crown Affair

(Norman Jewison, 1968)

Though he explored his rugged side in later movies, and his cooler side in earlier movies, Steve McQueen perhaps epitomised his reputation as Hollywood It-Guy in this of-the-moment, groovy 60s heist flick. As millionaire criminal Thomas Crown, he exudes playboy charm with a dangerous edge, seducing stone-faced insurance adjuster Vicki Anderson (Faye Dunaway) with the most famous chess game in film history.

Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines

(Ken Annakin, 1965)

It’s chocks away for a squadron of international comedians in this barnstorming comedy about an aerial race from London to Paris in 1910. Robert Morley is the patriotic lord stumping up £10,000 prize money, hoping that dashing Englishman James Fox will win the dosh, and his daughter Sarah Miles’s hand. Fast, slapstick fun, from beginning to end.

Three Colours Trilogy

(Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1993-94)

In two short years, Kieslowski produced three haunting films that form the high water mark of old-style European arthouse cinema. His colour-coded trilogy explores liberty, equality and fraternity using overlapping destinies between characters as a leitmotif: in Blue, a woman (Juliette Binoche) grieves the loss of her family; in White, a Pole plots revenge against his French ex-wife (Delpy); in Red, a model (Irene Jacob) and a judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant) meet through a chance encounter.

Three Kings

(David O Russell, 1999)

Almost 10 years after the first Iraq war, and a couple of years before 9/11, this was a window of opportunity to make a thoroughly cynical, subversive movie about rascally American soldiers fighting in the Middle East. David Russell’s movie is about three dodgy adventurers — George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg, and Ice Cube — who set out to steal Kuwaiti gold. There are some daring comments about hypocrisy and torture: an interesting, underrated movie.

The Three Musketeers

(Richard Lester, 1973)

Of the many screen versions of the Dumas classic, Lester’s exuberant account is the most outright fun: a rousing mix of knockabout action and coarse-grained humour, performed with obvious merriment by a starry cast including Michael York as the artless D’Artagnan, Frank Finlay, Richard Chamberlain and glowering Oliver Reed his trusty trio.

Throne of Blood

(Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

So many big-screen Shakespeare adaptations are stilted and self-conscious but these aren’t charges that can be levelled at Kurosawa’s bloodcurdling Samurai-style reworking of Macbeth. The action is transferred to a foggy medieval Japan, and a brutal, arrowy death scene makes it an extraordinary finish.

Thunderball

(Terence Young, 1965)

Purists may argue over the greatest Bond movie, but the shadow this one cast over the series cannot be ignored. The handmade approach to this film means that sequences such as the fight between dozens of divers not only thrill in the context of the story, but amaze as feats of physical film-making.

THX 1138

(George Lucas, 1971)

The story may borrow rather heavily from George Orwell, but Lucas’ visuals are quite stunning. A sterile future world populated by drugged-out shaven-headed citizens and policed by robots, it has plenty of stark, interesting detail to engage the viewer — Walter Murch’s inventive collage soundtrack adds further layers.

Time of the Gypsies

(Emir Kusturica, 1988)

A combination of magical romance and down-to-earth realism, Kusturica’s epic, set in the former Yugoslavia, fills the screen with unfamiliar sights and sensations, and conjures some moments of cinematic awe. To call it lively is an understatement.

Time Out

(Laurent Cantet, 2001)

Detached yet emotional, this French drama that makes the ordinary world of employment look like an alien landscape, and captures the desperation and anxiety of economic identity. Aurelién Recoing plays a man too ashamed to reveal his joblessness to his family, and his pretence takes him further and further out of his depth.

Time Regained

(Raoul Ruiz, 1999)

Ruiz’s brilliant account of the final volume of Proust is a brilliant intuition of Proust’s passionate journey back into his past and the belle époque. Almost every French character actor was present, including Emmanuelle Béart as Gilberte, Catherine Deneuve as Odette, and Pascale Greggory as Robert Saint-Loup. Superbly atmospheric.

A Time to Live and a Time to Die

(Hou Hsiao-Hsien, 1985)

Arguably the masterwork of modern Taiwanese cinema, a loosely autobiographical account of the generation gap among a family of Chinese exiles from the mainland. Filmed with awe-inspiring humanity, and a luminous visual brilliance.

Timecode

(Mike Figgis, 2000)

With this boldly experimental picture, Figgis showed that the spirit of questioning, envelope-pushing, cerebral cinema is still alive in the UK. Using a split screen and digital video techniques, Figgis showed four different lives and different narratives unrolling in parallel and in real time, directing our attention from one to the other in the sound mix. They separate and overlap, and the effect is a little mind-fuddling, but fascinating.

The Tin Drum

(Volker Schlöndorff, 1979)

Allegorical epic set in interwar Germany, revolving around the unusually perspicacious son of a rural couple who receives a tin drum on his third birthday and decides not to grow any older. Schlöndorff’s award-winning adaptation of Grass’s novel is a savagely funny defiance of Nazism, personified by little drum-banging Oskar and his haunting ear-splitting scream.

Titanic

(James Cameron, 1997)

Triumphant director James Cameron declared at the Oscars that he was «king of the world!» And for a while he was, with this piece of spectacular hokum, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet as star-crossed lovers aboard the sinking ship. Their story was deemed to have been the Gone With The Wind for a new generation.

To Be or Not to Be

(Ernst Lubitsch, 1942)

A brilliantly pointed comedy from Lubitsch, bringing the energy and fizz of the screwball genre to political satire. Carole Lombard and Jack Benny play two actors in a repertory company adrift in Warsaw during the Nazi invasion. Disguised as a Nazi, Jack Benny has the sensationally provocative line: «We do the concentrating and the Poles do the camping!» Lubitsch was criticised for this, but this devastatingly non-PC blast has more bite than any of the sentimental nonsense of Roberto Benigni’s Life Is Beautiful.

To Have and Have Not

(Howard Hawks, 1944)

No one doubts that the US fought the second world war with courage, zeal and even justice. But it says so much for the cheek and the cool of the country that the big war effort here is devoted to «You do know how to whistle, don’t you?» It’s taken from Hemingway, but what counts is Bogart and Bacall meeting under the camera’s gaze and following the inner script.

To Kill a Mockingbird

(Robert Mulligan, 1962)

From the Harper Lee novel, the story of how Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) defends a black man in a southern, country court. Intensely liberal, beautifully written and played, the film is seen from a child’s point of view: fathers and daughters are especially passionate about it.

Together

(Lukas Moodysson, 2000)

Great Swedish feelgood movie. Moodysson’s acutely observed comic 70s period piece sees a commune through the young and wonderfully vulnerable eyes of Eva and Stefan. Hippy values are gently satirised while the vitriol is reserved for the hypocritical middle class neighbours. As Eva adeptly observes — all adults are idiots.

Tokyo Drifter

(Seijun Suzuki, 1966)

A stylised yakuza thriller swinging to the beat of Japan’s burgeoning youth culture. The story is mournful in tone — a hitman driven by loyalty; his gang bosses driven by money — but the sets are outlandish and colour saturates the screen. How many heroes could pull off a powder-blue suit?

Tokyo Story

(Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

The great Japanese director’s masterpiece. Full of the quiet drama of family life, it follows an elderly couple who leave their quiet provincial home to visit their children in chaotic Tokyo, only to find that both their son and daughter are too busily self-centred to care for them: this is simplicity bordering on the magical.

Tom Jones

(Tony Richardson, 1963)

Henry Fielding’s bawdy, big-hearted 18th-century novel, joyously recreated for the swinging 1960s. Albert Finney is Tom, the foundling who undergoes a variety of picaresque and amorous adventures before finally wedding squire’s daughter Sophie (Susannah York); screenwriter John Osborne won one of the film’s four Oscars for his brilliant distillation of the massive book.

Tommy

(Ken Russell, 1975)

The Who’s deranged rock opera depicting a deaf, dumb and blind kid who sure plays a mean pinball. Don’t let the plot put you off: this is a peculiarly British acid trip (unsurprising with Russell at the helm). As well as the Who, there’s Jack Nicholson, Tina Turner, and Elton John to look out for in this strange tale.

Top Gun

(Tony Scott, 1986)

Testosterone-charged valentine to the macho world of fighter pilots, Tony Scott’s slick, bombastic blockbuster is pure 80s gold. Sporting leather flying jacket and aviators, little Tom Cruise grins and struts as he takes on rival hotshot Val Kilmer and romances teacher Kelly McGillis to classic power ballad Take My Breath Away.

El Topo

(Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970)

The only way they could sell this hard-to-categorise movie to early 70s audiences was to promise them that they’d be seeing things that they wouldn’t see elsewhere. That’s a promise that’s still valid. Jodorowsky’s imagery is cryptic rather than just wilfully surreal, which is why this is still pored over today.

Touch of Evil

(Orson Welles, 1958)

Sex, drugs, violence, corruption, a lurid border town, a butch gang terrorising poor Janet Leigh, a walrus-sized police captain whose very flesh seems contaminated with vice. Welles’ final studio picture swarms with bright light and big sound; its every scene is sensational, onward from the famous first tracking shot.

A Touch of Zen

(King Hu, 1969)

It clocks in at a fearsome 3 hours 20 minutes and starts with a glacially paced ghost story, but this martial arts epic is worth the effort. Its action sequences have been picked over by later film-makers (notably Ang Lee, for the bamboo-forest fight in Crouching Tiger), and it is conceived and choreographed with a grand scope that builds to an awesome peak.

Touching the Void

(Kevin Macdonald, 2003)

A gripping true-life story about friendship, survival and the existence of God. Macdonald’s drama-documentary recreated Joe Simpson and Simon Yates’s climbing expedition in the Peruvian Andes in the 1980s. Simpson broke his leg in zero-visibility snow and wind; Yates, guessing he was dead, cut his rope and carried on alone. Simpson survived — and began crawling back to base camp.

Toy Story

(John Lasseter, 1995)

Genius computer effects are matched by a witty script and engaging characters in a sweet animated adventure. Tom Hanks is the voice of Woody, a pull-string cowboy who becomes jealous when flashy spaceman Buzz Lightyear supplants his position as top toy. As appealing for adults as it is for kids.

The Train

(John Frankenheimer, 1964)

Rousing war movie that still stirs the blood. Burt Lancaster is the crafty railway inspector who masterminds the Resistance’s plan to prevent the Nazis stealing the cream of France’s paintings before the Allies reach Paris.

Trainspotting

(Danny Boyle, 1996)

Shocking and funny by turns, this exhilarating trawl through Edinburgh’s junkie subculture opens with a pounding chase set to Iggy Pop’s Lust for Life and never lets up. Emaciated Ewan McGregor is sympathetic as amoral hero Renton, and there’s knockout support from all concerned.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

(John Huston, 1948)

On location in Mexico, it looks and feels rough as three men go hunting for gold — it’s Tim Holt (solid), Bogart (treacherous) and Walter Huston (the inspired old-timer who laughs like crazy as the gold goes blowing in the wind). Directed by Huston’s father, John.

Trees Lounge

(Steve Buscemi, 1996)

First-time director Buscemi ruminated on what might have been in this poignant, personal story about a barfly loser who learns some serious life lessons the hard way. Buscemi brings a lugubrious authenticity to the downtrodden Tommy, a serial quitter whose days in the boozy gloom of the local bar will resonate with anyone who’s ever stood on the brink of a lost weekend.

The Trial

(Orson Welles, 1962)

Listen for the sound of the typewriters. Orson Welles hired hundreds of typists and filled a factory with desks to convey the soullessness of the office life Josef K (Anthony Perkins) endured. Kafka has rarely been brought to the screen better. Welles described it as his most autobiographical movie. «I’ve had recurring nightmares of guilt all my life,» he claimed.

Triumph of the Will

(Leni Riefenstahl, 1935)

As much a triumph of Riefenstahl’s will as Hitler’s, as she had to overcome innumerable technical difficulties to film the 1934 Nuremberg rally. The purpose, she freely admitted, was «the glorification of the Fuhrer», and with all the Nazi crazy gang, plus legions of stormtroopers on show, it remains a potent, disturbing piece of propaganda.

Tron

(Steven Lisberger, 1982)

When the 80s weren’t sending android assassins back in time, they were sucking you into renegade computer mainframes. Disney’s 1982 technophobe spectacular foxed audiences who had barely got used to Pacman, but stands as a retro-futuristic wonder now, as Jeff Bridge’s hacker makes seamless digital love with the glorious wireframe backdrops.

Trop Belle Pour Toi

(Bertrand Blier, 1989)

Satirical romantic comedy about an affluent middle-aged car dealer (Gerard Depardieu) who develops an inexplicable passion for his sweet, frumpy secretary (Josiane Balasko), and cheats on his beautiful trophy wife (Carole Bouquet). Though not as provocative as Blier’s earlier films, the classic husband-wife-mistress triangle goes beyond the farce, laced with sombre-edged reflections on love.

Twelve Monkeys

(Terry Gilliam, 1995)

Is he a time traveller or suffering a psychotic episode? Gilliam manages to be both cohesive and cryptic with this expansion of Chris Marker’s La Jetee. As with most of Gilliam’s imaginative output, you can’t help feeling that this managed to slip through while the studio executives weren’t looking.

24 Hour Party People

(Michael Winterbottom, 2002)

Affectionate and evocative drama about the rise and fall of the Manchester music scene from the late 70s to the early 90s. Steve Coogan is enjoyably daft as self-styled music impresario Tony Wilson — a man universally despised by the volatile talent he champions, from Joy Division and New Order to the Happy Mondays.

Two Lane Blacktop

(Monte Hellman, 1971)

The Driver, the Mechanic, the Girl, GTO: the road-weary gear-heads and «smalltown car-freaks» of Hellman’s existential masterpiece (by way of Camus and photographer Robert Frank) are so profoundly alienated that they’ve drifted away from their own names, as they race for pink slips across the backroads of a vanishing America.

2001: A Space Odyssey

(Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

The ambition of Kubrick’s sci-fi picture is still breathtaking, and the movie holds up perfectly well, despite CGI advances. In fact, its sheer imaginative boldness towers over other space adventures. A journey into the far reaches of space becomes a parable for man’s evolutionary progression into a post-human, or super-human existence. Very few films really inspire awe, but this is one.

Содержание:

- Жанры кино на английском языке.

- Кинопроизводство.

- Английские слова на тему «Кино»: общая лексика.

Слова и выражения о кино — это один из слоев лексики, в которые проникло много заимствований из других языков. Нередко их можно заменить русскоязычными аналогами, но этого не делают, особенно в профессиональной среде, для экономии времени и простоты выражения мыслей. Как известно, язык всегда стремится к простоте.

Например, вместо «сеттинг» можно сказать «место и время действия», но слово «сеттинг» просто короче. Некоторые слова иностранного происхождения уже прочно вошли в русский язык и не воспринимаются как иностранные, например: актер, монтаж, жанр, вестерн.

Жанры кино на английском языке

Ниже приведены общие названия жанров кино на английском языке. Эти слова не всегда используются в чистом виде. При описании фильмов могут встретиться также поджанры и смешанные жанры. Например, жанр action-adventure (приключенческий боевик) или поджанр фильмов о любви (romance) — романтическая комедия (romantic comedie).

| genre | жанр |

| feature film | художественный фильм (полнометражный) |

| short film | короткометражный фильм |

| action | боевик |

| adventure | приключенческий фильм |

| comedy | комедия |

| drama | драма |

| crime | криминальный фильм |

| horror | фильм ужасов (хоррор) |

| fantasy | фэнтези |

| romance | фильм о любви |

| thriller | триллер |

| animation | анимационный фильм |

| family | семейный фильм |

| war | фильм о войне |

| documentary | документальный фильм |

| musical | мюзикл |

| biography | биографический фильм |

| sci-fi | научная фантастика |

| western | вестерн |

| post-apocalyptic | постапокалипсис |

Скачать PDF

Кинопроизводство

Фильм — это результат долгой и слаженной работы большого коллектива профессионалов, производственный цикл фильма делится на основные этапы:

- Проектирование (development) — создается проект фильма, сценарий, согласуются основные финансовые вопросы.

- Предварительная подготовка (pre-production) — формируется съемочная группа, подбираются актеры, планируются съемки.

- Съемки (production) — собственно, снимается фильм.

- Пост-производство (post-production) — монтаж, звук, спецэффекты.

- Распространение (sale) — то, ради чего все и делается. Бывают случаи, когда именно на этом этапе из-за плохого маркетинга «запарывается» отличный проект.

Чаще всего говорят о этапах pre-production, production и postproduction. Хоть для этих терминов и есть русскоязычные эквиваленты «предварительная подготовка», «съемки» и «пост-производство», но довольно часто говорят просто «препродакшн», «продакшн» и «постпродакшн».

Подобная история со словами sequel, prequel, spin-off, которые можно перевести как предыстория, продолжение и ответвление, но чаще для простоты и удобства мы говорим «сиквел», «приквел» и «спин офф».

| cast | актерский состав |

| crew | съемочная команда |

| actor | актер |

| actress | актриса |

| movie star | кинозвезда |

| director | режиссер |

| scriptwriter | сценарист |

| cameraman | оператор |

| stunt | каскадер |

| make up artist | гример |

| make up | грим |

| costume designer | художник по костюмам |

| film editor | монтажер |

| stunt coordinator | постановщик трюков |

| lighting technician | осветитель |

| stylist | стилист |

| choreographer | хореограф |

| music composer | композитор |

| soundtrack | саундтрэк |

| sound effect | звуковой эффект |

| visual effect | визуальный эффект |

| CGI (computer-generated imagery) | компьютерная графика |

| special effect | спецэффект |

| pre-production | предварительная подготовка фильма (препродакшн) |

| production | съемочный этап (продакшн) |

| post-production | пост-производство фильма (постпродакшн) |

| prequel | приквел |

| sequel | сиквел |

| spinn off | спин офф |

| remake | римейк |

Скачать PDF

Английские слова на тему «Кино»: общая лексика

Эти слова и выражения пригодятся для обсуждения фильма. Особенно пригодится фраза «the film is set in», которая встречается в описании любого фильма. В данном случае фразовый глагол set in имеет значение «иметь местом и временем действия», например:

The film is set in the 1990s on a small tropical island. — Действие фильма происходит в 1990-х на маленьком тропическом острове.

Отсюда же и слово setting (сеттинг) — место и время действия.

| movie (film) | фильм |

| television series (TV show) | телесериал |

| soap | мыльная опера |

| the show aired on the AMC | шоу (сериал) выходило в эфир на AMC |

| plot | сюжет |

| exposition | экспозиция |

| conflict | конфликт |

| rising action | развитие действия |

| climax | кульминация |

| resolution | развязка |

| plot twist | сюжетный поворот |

| cliffhanger | клиффхэнгер (худ. прием: обрыв повествование в напряженный момент, особенно часто в сериалах) |

| scene | сцена |

| episode | эпизод |

| season | сезон |

| dialogue | диалог |

| main character | главный герой |

| hero (heroine) | герой (героиня) |

| anti-hero | антигерой |

| superhero | супергерой |

| villain | злодей |

| the film is set in | действие фильма происходит в |

| setting | сеттинг |

| to shoot | снимать на камеру |

| the film came out in 2015 | фильм вышел в 2015 году |

| subtitles | субтитры |

| the film is dubbed into Russian | фильм дублирован на русский язык |

| close-up | крупный план |

| long shot | общий план |

| big-budget film | высокобюджетный фильм |

| B-movie | низкобюджетный фильм (фильм категории «B») |

| gag | шутка |

| suspense | саспенс (худож. прием: тревожное, напряженное ожидание) |

| narrator | рассказчик |

| slow motion | замедленное движение |

| time-lapse | ускоренное движение |

| voice-over | закадровый голос |

Скачать PDF

Читайте также близкие по теме статьи:

- Как смотреть сериалы на английском?

- Puzzle Englsh — изучаем английский язык по сериалам.

Здравствуйте! Меня зовут Сергей Ним, я автор этого сайта, а также книг, курсов, видеоуроков по английскому языку.

Подпишитесь на мой Телеграм-канал, чтобы узнавать о новых видео, материалах по английскому языку.

У меня также есть канал на YouTube, где я регулярно публикую свои видео.