The general word for father in Japanese is お父さん (otousan). However, there is more than one way to say father in Japanese.

In a previous article, we discussed the various terms for mother in Japanese and when to use them. The same rules apply here: depending on whose father you’re speaking about and the social situation you’re in, the word will be different. Once you start learning Japanese, knowing the right word to use will become easy. Let’s look at how to say father in Japanese.

1. 父(Chichi)- My Father

父 (chichi) is a general term for father in Japanese. You only use chichi to refer to your own father when talking to other people.

It’s important to remember that chichi is more of a term, not a title. It wouldn’t be polite to speak to your father and call him chichi. You use it when you talk to other people about your father.

Examples:

1. 父は漬物が苦手なんです。

(Chichi wa tsukemono ga nigate nan desu.)

My father doesn’t like pickles.

2. 父は2年前に亡くなりました。

(Chichi wa ni nen mae ni naku narimashita.)

My father passed away 2 years ago.

3. 将棋は父から教わりました。

(Shougi wa chichi kara osowarimashita.)

I learned how to play Shougi (Japanese chess) from my father.

2. お父さん(Otousan)- Dad, Father

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, お父さん (otousan) is the “general” way to say father in Japanese. This is because the word otousan is probably the most “useful” way to say father.

You can use it when you talk about someone else’s father. Many Japanese people also call their own dad otousan. You can even call your spouse’s father otousan since you are married into their family.

Adults also use the word when they are speaking to younger children about their fathers. A teacher might even say otousan when speaking directly to the father of one of their students.

Depending on the social situation, the suffix -さん (-san) may be replaced with -様 (sama) for a more formal nuance. This would hold the same meaning as “father,” whereas otousan might be more like “dad.”

Otousama is very polite and formal, so you’ll often hear it said by staff (in a store, school, etc.). You’ll never hear people refer to their own father as otousama in this modern era.

On the other side of the spectrum, adding the suffix -ちゃん (-chan) creates the Japanese equivalent of “daddy.”However, otouchan is an incredibly popular title these days, especially among younger children.

Examples:

1. お父ちゃん! 朝ごはんできたよ!

(Otou-chan! Asagohan dekita yo!)

Dad! It’s time for breakfast!

2. 太助君、この写真はお父さんが撮ったの?

(Tasuke-kun, kono shashin wa otousan ga totta no?)

Did your dad take this picture, Tasuke?

3. 父親(Chichi-Oya)- A Father

The word 父親(chichi-oya)is a general term for father in Japanese. Chichi-oya is even less personal in its nuance than chichi and is used when speaking about all fathers in general.

If you use it to directly refer to someone’s father, (as in, “how is your father?” or “I saw your father today.”), it will come off as cold and even impolite. Calling your father chichi-oya would also be unnatural or cold, so be careful about when you use this term.

It’s often used to refer to fathers in general (example #1 and #2 below). It can also be used to talk about your father in an impersonal way (example #3).

Examples:

1. 父親は父の日に、ビールが欲しいと言われています。

(Chichi-oya wa chichi no hi ni, biiru ga hoshii to iwarete imasu.)

Fathers like receiving beer for Father’s Day.

2. 父親のいない家庭

(Chichi oya no inai katei.)

Fatherless households.

3. 私には父親の違う妹がいます。

(Watashi niwa chichi oya no chigau imouto ga imasu.)

I have a younger sister with a different father.

4. 親父(Oyaji)- Old Man, Pops

When used to refer to father in Japanese, the word 親父 (oyaji) should be restricted to casual conversation. Oyaji has a warmer, more personal nuance to it than chichi-oya or chichi, but is very informal.. The English equivalent would be something like “my old man.”

You can use oyaji when talking about your dad to someone else (example #1 below). Some people call their own dad oyaji (examples #2 and #3).

Oyaji can also be used to refer to an older man past his 50s (example #4 below).

The term oyaji tends to have a rugged, masculine sense when it’s used. Men use oyaji more than women, as Japanese is still a fairly gendered language.

Adding “-san” to form the word 親父さん (oyajisan) can possibly be used to refer to your boss if you are in a “master & disciple” type of relationship. For example, some people who are learning techniques and skills from a sushi chef or craftsman might call their master oyajisan.

One fun fact about this term is that the Japanese use it in their word for dad jokes: 親父ギャグ(oyaji gyagu), or “old man gag!”

Examples:

1. うちの親父は変わっている人だよ!

(Uchi no oya-ji wa kawatteiru hito da yo!)

My old man is a weirdo!

2. ラーメン作るけど、親父も食べる?

(Ramen tsukuru kedo oyaji mo taberu?)

I’m going to make some ramen. Would you like some, dad?

3. 親父、田中さんから電話だよ。

(Oyaji, Tanaka san kara denwa da yo.)

Dad, youu have a call from Mr. Tanaka.

4. あそこの親父は誰?

(Asoko no oyaji wa dare?)

Who is that old guy over there?

5. パパ(Papa)- Papa, Daddy

It might be surprising to hear Japanese children use an English word like papa, but this borrowed term for father is used in Japan all the time. パパ(papa) is similar in Japanese to daddy.

The majority of people who use it are young children—or perhaps their parents. Like otou-chan, the word papa is considered “cute” and casual. Even young children, who are taught the formality of their language and culture from a very young age, might not use papa in polite company.

Example:

1. パパ、抱っこして!

(Papa, dakko shite!)

Daddy, pick me up!

6. おとん(Oton)- Paw, Pa

The word おとん (oton) is technically 関西弁 (Kansai-ben), or Japan’s dialect in the Kansai region. This gives the word a very casual and fun-loving feel. It’s not the right word for father if you’re in polite or formal company, but oton is great for friends and family.

Kansai-ben is a big part of Japan’s pop culture, as most comedians are from Osaka and have a heavy dialect. If you use oton correctly, you’ll be a big hit and make plenty of people smile.

Example:

1. な、おとん。たこ焼き食べへんか?

(Na, oton. Takoyaki tabehen ka?)

Pa, do you want some takoyaki?

7. 義理のお父さん(Giri no Otousan)- Father-in-Law

義理のお父さん (giri no otou-san) is the proper term for the father of your spouse. While many people go on to refer to their fathers-in-law as otousan or other less formal terms, giri no otousan will typically be the go-to for polite company.

Like chichi, giri no otousan is a word to use when speaking about your father-in-law. When speaking to him, use otousan. If you feel like your relationship isn’t that close yet, it’s perfectly acceptable to refer to your father-in-law by his name. Be sure to add the suffix -san to that as well!

Example:

1. 義理のお父さんは 弁護士です。

(Giri no otou-san wa bengoshi desu.)

My father-in-law is a lawyer.

8. 父上(Chichi-Ue)- Honorable Father

父上 (chichi-ue) is an old-fashioned word that was used by samurai and noble families. However, you’ll often come across the term in Japanese literature or media. It is rarely, if ever, used in everyday conversation.

You might use chichi-ue if you’re messing around and want to sound dramatic or old-fashioned (example below).

Example:

1. 父上、こっちに来てください。

(Chichi-ue, kocchi ni kite kudasai.)

Come here, honorable father.

9. 尊父(Sonpu)- (Your) Honored Father

尊父 (sonpu) is honorific Japanese. It means “your father” and often has the prefix 御 (go-) preceding it for extra formality.

Sonpu is rarely used outside of written Japanese. You’ll often find it in condolence letters or other formal addresses for special occasions.

Example:

1. 御尊父へよろしくお伝えください。

(Gosonpu e yoroshiku otsutae kudasai.)

Please give my respects to your honored father.

10. 父君(Chichi-Gimi)- (Your) Honored Father

The word 父君 (chichi-gimi) has the same meaning and nuance as sonpu.

Chichi-gimi is honorific Japanese or 尊敬語(sonkeigo). It should only be used to refer to other people’s fathers. If you use chichi-gimi to refer to your father, it will seem as though you are honoring yourself.

However, this is a word that almost no one uses in daily conversation. You’ll probably never run into a situation where you’ll have to use this word too. The words chichi, otousan, and otousama (explained above) will fit almost all of the situations you find yourself in.

Example:

1. 父君に「お誕生日おめでとうございます」と伝えて頂きたい。

(Chichi-gimi ni “otanjoubi omedetou gozaimasu” to tsutaete itadakitai.)

Please tell your father I wish him a happy birthday.

Conclusion

There are many ways to say father in Japanese. Choosing the right word will depend on whether you’re speaking to your father or talking about someone else’s.

Of course, the formality of the situation you are in and the people you are talking to should also be considered. Take these into consideration, and you’ll be able to say father in Japanese like a native!

How do you say father in your language? Let us know in the comments! Thank you for reading this article on how to say father in Japanese.

Team Japanese uses affiliate links. That means that if you purchase something through a link on this site, we may earn a commission (at no extra cost to you).

Among the first few vocabulary we learn in any language is how to call our family members. A standard word for father in Japanese is otousan (お父さん / おとうさん). But did you know that there are many other ways to refer to your father in Japanese?

Depending on who you are speaking to or talking about, you might have to change your speech to better fit the situation. You must be polite when speaking to your father, but you can be humble when talking about him to other people. Sounds a bit tricky, right?

Fear not! Here is our handy guide on the different Japanese words for ‘father’.

- Otousan

- Chichi

- Papa

- Tousan/touchan

- Chichi oya

- Chichi ue

- Oyaji

- Oton

- Giri no otousan

お父さん

Father (polite)

The most common way to say father in Japanese is otousan (お父さん / おとうさん). This can be used when you are speaking to your own father or talking about somebody else’s father.

Examples:

Speaking directly to your father

Otousan, Shohei-kun to matsuri ni itte mo ii desu ka?

お父さん、所平くんと祭りに行ってもいいですか。

おとうさん、 しょへいくん と まつり に いって も いい です か。

Father, may I go to the festival with Shohei?

Talking about somebody else’s father

Hana-chan no otousan wa enjinia desu.

ハナちゃんのお父さんはエンジニアです。

はなちゃん の おとうさん は えんじにあ です

Hana’s father is an engineer.

Take a look at the second example. The polite form is important when talking about someone else’s father, because it denotes respect for them. In fact, people also call their fathers-in-law otousan! There is another word for father-in-law, which will be discussed further down this list.

In otousan, the character for father (父) has the prefix ‘o’ (お) and the honorific suffix -san (~さん). The former is attached to a word in its kunyomi or Japanese reading to make it more polite, while the latter adds the meaning of Mr. or Ms. when added to a name.

Another variation is otousama (お父様 / おとうさま). This only appears in extremely formal situations and written communication, and is rarely used in daily conversation. Depending on the situation, you must mind the right usage of this word!

Chichi

父

Father (humble)

Chichi (父 / ちち) is the humble way to say father in Japanese. It is typically used when speaking about your father to somebody else. It can also mean father in a general context, like how it is used in chichi no hi (父の日 / ちちのひ) or Father’s Day.

Example:

Chichi wa byouin ni tsutomete iru.

父は病院に勤めている。

ちち は びょういん に つとめている。

My father works for a hospital.

As you may have noticed, chichi consists of only the kanji for father (父), missing any polite or honorific markers unlike otousan, which makes this a humble term.

This is also the word that adults use when they talk about their father to somebody else. Keep in mind that it is not polite to call your father chichi when speaking to him!

Papa

パパ

Dad

Papa (パパ) is used across all languages by little children of elementary age or younger to talk about or speak to their father. Japanese also has a number of loan words from various languages, and papa is one of them. Because of this, it is always written in katakana.

When children grow older, they are expected to start calling their father otousan. Although in some cases, female children may use papa as an affectionate way of addressing their fathers even in adulthood. This is not so common for male children.

Tousan/touchan

父さん / 父ちゃん

Daddy

Just like the previous word, tousan (父さん / とうさん) and touchan (父ちゃん / とうちゃん) is a child-like variation of otousan. Think of this word as the equivalent of ‘daddy’ in English. If you are a child, you may use this word when speaking to your father or when you talk about him to your friends.

The honorific -chan (~ちゃん) is added to a word or name to give a more affectionate meaning. Even if kids get accustomed to using tousan or touchan, they typically grow out of it and start using otousan when they reach middle school.

Chichi oya

父親

Father-parent

When speaking about ‘father’ in a broader context, just like in the news or an informative documentary, you might hear chichi oya (父親 / ちちおや). This word directly translates to ‘father-parent’. It can refer to any male that has a child or has been a father. It can also be used to identify human or animal fathers too!

Compared to most of the words on this list, chichi oya is less frequently heard in daily speech, so it will sound awkward to use this when talking with your father or somebody else’s.

Chichi ue

父上

Father (old-fashioned)

Now here’s one for the history buffs! Chichi ue (父上 / ちちうえ) is an archaic word for father in Japanese. It translates to ‘honorable/honored father’.

The word ue (上 / うえ) means ‘above’ or ‘up’, and when added to chichi signifies honor or respect for one’s father. This was originally used in households of the samurai or nobility before the Meiji restoration.

Even though nobody uses this anymore, you can hear chichi ue in dialogue in historical video games, dramas, or movies. You can most definitely use this to joke around with your dad and have a good laugh, too!

Oyaji

親父

One’s father, my old man

Because they are comprised of the same characters, you might think that oyaji (親父 / おやじ) is the same as chichi-oya, but reversed. Oyaji means one’s father, but it is more colloquial-sounding. It can also refer to middle-aged or elderly men.

It’s more common to hear men use this term in a familiar language when referring to their own fathers, think ‘my old man’ in English. You can also use this when speaking directly to your father.

One interesting use of this word is between a master and apprentice. Somebody in an apprenticeship can call their teacher or master oyajisama (親父様 / おやじさま). Another use is oyaji gyagu (オヤジギャグ), which pertains to ‘bad/corny pun’ or ‘old man gag’!

Oton

お父ん

Dad (Kansai dialect)

Oton (お父ん / おとん) is the word for father in Kansai dialect. On your Japanese learning journey, you’re bound to come across a number of words in Kansai-ben or dialect. It is one of the most widely-spoken dialects in Japan and is more casual-sounding than the ‘standard Japanese’ spoken in Tokyo.

Compared to the rest of the words for dad, oton sounds more ‘country’, so if you end up blurting it out in a formal situation, it will sound funny. Did you know that the best Japanese comedians hail from the Kansai region? If you learn a bit of Kansai-ben, you will be able to appreciate a lot of comedy on TV!

Giri no otousan

義理のお父さん

Father-in-law

One can call their spouse’s father otousan when speaking directly to them, but when talking about your father-in-law, the proper term to use is giri no otousan (義理のお父さん / ぎりのおとうさん). This is appropriate for polite situations and for addressing other peoples’ fathers-in-law.

There are also the words giri no chichi (義理の父 / ぎりのちち) and gifu (義父 / ぎふ) which also mean father-in-law.

Giri (義理 / ぎり) means ‘in-law’ or ‘relation by marriage’. It can also mean ‘step’ as in ‘step father’ or ‘step sibling’.

Dad in Japanese

We hope you found this post useful! In English, we have lots of different words to refer to our fathers (dad, daddy, pops, the old man…) and Japanese is no different! Just remember to think about who you’re talking to, and what level of formality is needed.

Learn how to talk about your other family members in Japanese here:

Related posts:

- How to Say Mother in Japanese

- How to Say Sister in Japanese

- How to Say Brother in Japanese

- How to Say Daughter in Japanese

- How to Say Son in Japanese

- How to Say Husband in Japanese

- How to Say Wife in Japanese

Ready to take the next step in your Japanese language journey? Our recommended online course is JapanesePod101.

Thea Ongchua

Thea is a freelance content writer, currently majoring in Japanese studies. She likes to create art and draws inspiration from film and music. Thea was inspired to study Japanese language and culture by reading the literary works of Haruki Murakami and Edogawa Ranpo.

How do you address your father in Japanese?

Japan. In Japan, most people use “Oto-san” which is a formal and polite word to call their father. While “Chichi” is used to refer to one’s father when they talk to someone else, “Oyaji” (Old man) is an informal way for sons to call their fathers.

How do you say dad in anime?

If you’ve ever taken an introductory Japanese class, or watched many J-dramas or anime, this is probably the first one you learned. Otou-san is the most common, broadly usable phrase for father/dad in Japanese.

Is oyaji disrespectful?

Oyaji – not really as rude as the below two, but its a little lower on the casual scale bordering on rude.. but not really. Something a son would usually say to their father or in reference to.

What is the meaning of Otosan?

Otosan means ‘someone else’s father’. It is also what you address your own father as. You do NOT use them to talk ABOUT your own parents. For this, as mentioned, use ‘haha’ and ‘chichi’.

What is Sugoi desu ne?

Sugoi desu ne! = Lit. Really? Great! このアニメは ほんとうに すごいですね!

What does Ora Ora mean in Japanese?

The word ‘ora‘ is used as a taunt, e.g. when trying to pick a fight with / bully someone. Its closest equivalent in English is “come on!” It’s usually uttered with a heavily emphasized, rolled R. 31. 2.

What does Ora Ora Ora Ora mean?

according to google translate , ora means ”Oh” and muda means ”Useless”. So whenever DIO says muda or ”useless” Jotaro replies with ora or ”Oh”.

What does Yare Yare?

“Yare yare” is a Japanese phrase that you will often hear in anime – especially if you are a fan of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. Yare yare (やれ やれ) is a Japanese interjection that is mainly used by men and means “Good grief”, “Give me a break”, or “Thank G

What is Oya in Japanese?

In Japanese, the meaning of the name depends on the kanji used to write it; some ways of writing the name include “big arrow” (大矢), “big house” (大家, 大宅, or 大屋), and “big valley” (大谷).

What is Oya Oya Oya?

oyao1237. Oya‘oya is an Oceanic dialect cluster spoken at the tip of the Papuan Peninsula in Papua New Guinea.

What does Baka mean?

Baka (馬鹿, ばか in hiragana, or バカ in katakana) means “fool”, or (as an adjectival noun) “foolish” and is the most frequently used pejorative term in the Japanese language. This word baka has a long history, an uncertain etymology (possibly from Sanskrit or Classical Chinese), and linguistic complexities.

What does Ara Ara mean?

What’s the meaning of ara–ara in Japanese? Ara–ara is a type of interjection, primarily used by youngish females to express some curious surprise and/or amusement. You could translate it as, “Oh-ho,” “tsk-tsk,” or “Hmm?” Another word with the same pronunciation means rough, rude, or harsh.

What does Oya mean Yoruba?

In Yoruba, the name Oya means “she tore.” She is known as Ọya-Iyansan – the “mother of nine” — because of 9 children she gave birth to all of them being stillborn; suffering from lifetime of barrenness. She is the patron of the Niger River (known to the Yoruba as the Odo-Ọya)

Is Oya a word?

OYA is not a valid scrabble word.

Is Eya a Scrabble word?

EYA is not a valid scrabble word.

Is uya a Scrabble word?

UYA is not a valid scrabble word.

Last Updated: December 14, 2021 | Author: andree2321

Contents

- 1 How do you say dad in anime?

- 2 What does Otochan mean?

- 3 What does Papi mean in Japanese?

- 4 How do you say dad in Japanese hiragana?

- 5 What San means in Japanese?

- 6 What is Senpai Japanese?

- 7 What is Mama Japanese?

- 8 Can Kun be used for a girl?

- 9 Can Senpai mean Daddy?

- 10 What do UwU mean?

- 11 What does DEKU mean in Japanese?

- 12 What does Oi mean in Japanese?

- 13 Is OwO furry or Weeb?

- 14 Is UwU a bad word?

- 15 Is UwU furry or Weeb?

- 16 What does UWU girl mean?

- 17 What does OwO mean in Roblox?

- 18 Why do furries say OwO?

How do you say dad in anime?

Father. The father of the family is usually addressed with otou-san, (お父さん), and with chichi (父) when referring to one’s own father to somebody outside the family.

What does Otochan mean?

The word “おとうさん” or “Otousan” means “father” in Japanese. The ‘o’ at the beginning is used as an honorific. ‘tou-san’ is just as acceptable, however it is much more informally used by a member of the family, or might even be used when a child is talking about their father to another person.

What does Papi mean in Japanese?

noun (common) (futsuumeishi) puppy.

How do you say dad in Japanese hiragana?

Chichi – “Father”; Otosan – Someone Else’s Father

- Kanji: 父 // Hiragana: ちち

- Kanji: お父さん // Hiragana: おとおさん

What San means in Japanese?

As a rule of thumb, in Japanese business life, the surname name is always followed by the honorific suffix “san” (meaning “dear” or actually “honorable Mr/Ms.”). There are of course many other options such as “sama” (highly revered customer or company manager) or “sensei” (Dr. or professor).

What is Senpai Japanese?

In Japanese the word is used more broadly to mean “teacher” or “master.” Like sensei, senpai is used in English in contexts of martial arts as well as religious instruction, in particular Buddhism. Sensei in those contexts refers to someone of a higher rank than senpai. Ranking below a senpai is a kohai.

What is Mama Japanese?

ママ (Mama)

The word ママ (mama) is used by little children in Japan to refer to their mother. It has the same nuance as the word “mommy.” … However, the nuance of mama is more childish.

Uwu is an emoticon depicting a cute face. It is used to express various warm, happy, or affectionate feelings. A closely related emoticon is owo, which can more specifically show surprise and excitement. There are many variations of uwu and owo, including and OwO, UwU, and OwU, among others.

For reference, a list of words for family members in Japanese.

- Introduction

- Summary

- Chart

- Family

- Family Tree

- Father

- Mother

- Son

- Daughter

- Parent

- Child

- Parent & Child

- Birth Order

- Counters

- Eldest Child

- Youngest Child

- Numbered Son Names

- Husband

- Shujin 主人

- Dan’na 旦那

- Father words

- Anata あなた

- Groom

- Wife

- Mother Words

- Bride

- In-Laws

- Spouses & Marriage

- Brother

- Older Brother

- Younger Brother

- Eldest Brother

- Youngest Brother

- Sister

- Older Sister

- Younger Sister

- Eldest Sister

- Youngest Sister

- Siblings

- 兄弟, 兄妹, 姉弟, 姉妹

- Twins

- Grandfather

- Great-Grandfather

- Grandmother

- Great-Grandmother

- Grandchild

- Great-Grandchild

- Grandparents

- Great-Grandparents

- Uncle

- Aunt

- Cousin

- Second Cousin

- Nephew

- Niece

- Nephew & Niece

- Adopted Family

- Blood Related

- Nuances, Usage & Differences

- San, Chan, Sama

- Chichi vs. Otousan

Haha vs. Okaasan

Ani vs. Oniisan

Ane vs. Oneesan - Mama, Papa

- Chichioya, Hahaoya

- Oyaji, Ofukuro

- Chichiue, Hahaue, Aniue, Aneue

- 父君, 母君

- 父御, 母御

- 尊父, 御親父

- ファーザー, マザー, シスター, ブラザー

- Aniki, Aneki

- 兄者, 姉者, 兄者人, 姉者人

- Obocchan, Ojousan

- Ooji, Ooba

- Jiji, Baba

- 外祖父, 内祖父, 外祖母, 内祖母, 外孫, 内孫

- 叔父, 伯父, 叔母, 伯母

- 従兄弟, 従姉妹, 従兄, 従弟, 従姉, 従妹

Introduction

This post is so long it needs an introduction. To clear any doubts you may have:

Kanji can be read different ways. This is why chichi 父 and otousan お父さん are written like that. Furthermore, one same word can be written with different kanji.

There are too many synonyms in this article. Check the nuances section at the end for clarification between multiple words. (in particular, the difference between chichi 父 and otousan お父さん)

Terms Found in References

The term NG as seen in the titles of many referenced articles stands for «not good» and means you shouldn’t use or say something.

- wo sasu を指す

To point at. (literally)

To refer to. - yobikata 呼び方

Way of calling (someone). - uyamau 敬う

To show reverence toward. (honorific terms do this.)

Summary

A summarized version of this whole article:

- kazoku 家族

Family.

- otousan お父さん

chichi 父

Father. - okaasan お母さん

haha 母

Mother. - oya 親

Parent.

- musuko 息子

Son. - musume 娘

Daughter. - ko 子

Child.

- oniisan お兄さん

ani 兄

Older brother. - otouto 弟

Younger brother. - oneesan お姉さん

ane 姉

Older sister. - imouto 妹

Younger sister. - kyoudaishimai 兄弟姉妹

Siblings.

- ojiisan お祖父さん

sofu 祖父

Grandfather. - obaasan お祖母さん

sobo 祖母

Grandmother. - sofubo 祖父母

Grandparents.

- magomusuko 孫息子

Grandson. - magomusume 孫娘

Granddaughter. - mago 孫

Grandchild.

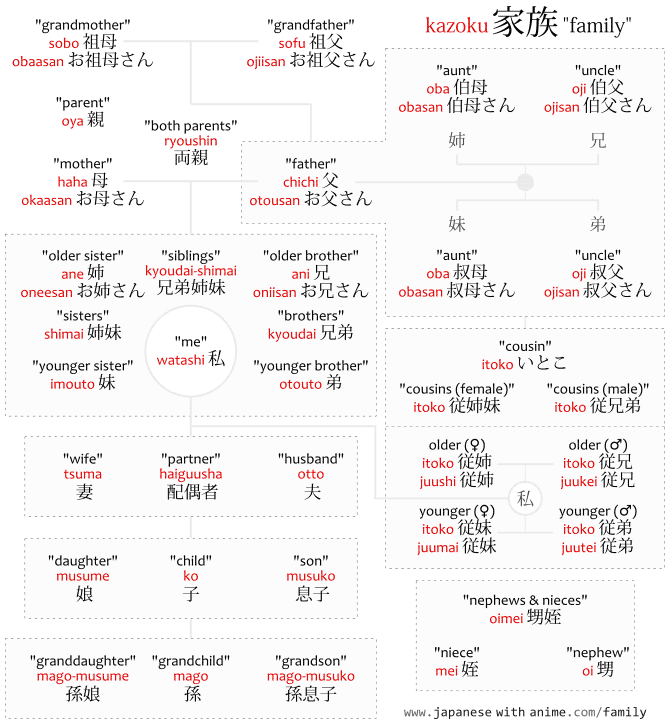

Chart

Here’s a chart of the Japanese family words:

To say family in Japanese:

- kazoku 家族

(Note: ohana お鼻 means «nose.»)

When «family» refers to one’s «household,» the term katei 家庭 is used instead. This would be used in cases like «familial» matters, something that happened inside the family. That is: kazoku is a family as a structure, kinship, while katei is domestic, related to home.

One phrase common in anime is katei jijou 家庭事情, «familial circumstances,» usually used when a characters parents want him to move from one school to another or something like that.

Family Tree

To say family tree in Japanese:

- kakeizu 家系図

This is because a kakei 家系 is the «lineage of a family,» while a zu 図 is a «diagram.»

Father

To say father in Japanese:

- chichi 父 [chichi vs. otousan]

- otousan お父さん

- otousama お父様

- otouchan お父ちゃん

- tousan 父さん

- touchan 父ちゃん

- otou お父 [san, sama, chan difference]

- papa パパ [papa, mama usage]

- chichioya 父親 [chichioya, hahaoya usage]

- oyaji 親父

- oyajisan 親父さん

- oyassan おやっさん [oyaji, ofukuro usage]

- chichiue 父上 [chichiue, hahaue, aniue, aneue usage]

- fukun 父君

- chichigimi 父君 [fukun, chichigimi, hahagimi usage]

- chichigo 父御

- tetego 父御 [chichigo, hahago, tetego usage]

- sonpu 尊父

- goshinpu 御親父 [sonpu, goshinpu usage]

- faazaa ファーザー [katakanizations of family words]

Note: a «father» as in a «priest» of the Catholic church, etc. is shinpu 神父 in Japanese.

Mother

The words for mother in Japanese:

- haha 母 [haha vs. okaasan]

- okaasan お母さん

- okaasama お母様

- okaachan お母ちゃん

- kaasan 母さん

- kaachan 母ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

- mama ママ [papa, mama usage]

- hahaoya 母親 [chichioya, hahaoya usage]

- ofukuro お袋

- ofukurosan お袋さん [oyaji, ofukuro usage]

- hahaue 母上 [chichiue, hahaue, aniue, aneue usage]

- hahagimi 母君 [fukun, chichigimi, hahagimi usage]

- mazaa マザー [katakanizations of family words]

Son

The word for son in Japanese is:

- musuko 息子

Toward the sons of other people, the following words are used:

- musukosan 息子さん

- obocchan お坊ちゃん

- obocchan お坊っちゃん

- bocchan 坊ちゃん [obocchan, ojousan usage]

- goshisoku ご子息

- goreisoku ご令息

The terms goshisoku and goreisoku are more formal and may be considered too formal to use normally, specially goreisoku.

Daughter

The word for daughter in Japanese is:

- musume 娘

Toward the daughters of other people, the following words are used:

- musumesan 娘さん

- ojouchan お嬢さん

- ojousan お嬢さん

- ojousama お嬢様 [obocchan, ojousan usage]

- goshijo ご子女

- gosokujo ご息女

- goreijou ご令嬢

The terms goshijo, gosokujo and goreijo are formal, and sometimes considered too formal to be used normally, specially goreijou.

Parent

To say parent in Japanese:

- oya 親

Parent.

- ryoushin 両親

Both parents. - goryoushin ご両親

(someone else’s) parents. - fubo 父母

Father and mother.

Father or mother. (in some cases) - kataoya 片親

Single parent. One of the two parents. - futaoya 二親

Two parents.

The terms above may all be used to say «parents» in Japanese. The term goryoushin ご両親, with the go ご honorific, is used to refer to the parents of other people, not your parents, only of other people.

Child

To say child in Japanese:

- ko 子

Child. - okosan お子さん

(someone else’s) child. - __ no ko 〇〇の子

__’s child. (insert name there.)

The word kodomo 子供 may refer to someone’s «children» in plural, __ no kodomo 〇〇の子供. But it may also refer to «children» as in «they’re young.»

(note: there’s an entirely separate article for ko 子 because that word has other uses.)

Parent & Child

The following terms are used when when talking about parent and child at the same time.

- oyako 親子

Parent and child. - fushi 父子

Father and child. - boshi 母子

Mother and child.

Sometimes, the kanji for «daughter,» musume 娘, may be used instead of ko 子 in the words above to hint the gender of the child is female. These’d be gikun, artificial readings. For example:

- oyako 親娘

oyamusume 親娘

Parent and daughter.

Birth Order

In Japanese, there are terms for sons and daughters based their birth order, which are used instead of phrases like «first son,» «oldest son,» «first daughter,» etc. we’d use in English.

Counters

Normally, the children are counted using numbers and counters.

- ichinan 一男

First-born son. Eldest son. - jinan 次男 (二男)

Second-born son. - san’nan 三男

Third-born son. - yon’nan 四男

Fourth-born son.

- ichijo 一女

First-born daughter. Eldest daughter. - jijo 次女 (二女)

Second-born daughter. - sanjo 三女

Third-born daughter. - yonjo 四女

Fourth-born daughter.

You may have noticed the terms jinan 次男 and jijo 次女 are not written with the kanji for «two,» ni 二, and not read ninan and nijo either. This happens because they second son and daughter are the «next» (after the first) son and daughter, so they’re written with the kanji for «next,» tsugi 次. They may be written with 二 too, but they’d still be read jinan and jijo.

Eldest Child

There are synonyms for «first-born» that use the kanji for the word «long,» nagai 長い, because they’ve been born for the longest time, they’re older, the eldest.

- chounan 長男

Eldest son. - choujo 長女

Eldest daughter. - choushi 長子

Eldest child.

For the record: the chounan is the chounan forever. The jinan never becomes chounan, not even if the chounan dies and the jinan surpasses him in (living) age. The same applies to the other words.

Youngest Child

The terms for the «youngest» child in Japanese used the kanji for the word «end,» matsu 末, as they’re the last children born and consequently at the end of the offspring list.

- matsunan 末男

Youngest son. - matsujo 末女

Youngest daughter. - suekko 末っ子

Youngest child.

Numbered Son Names

In some cases, parents may name their sons following a certain custom of adding a suffix according to their birth order. In which case, the name of a person (or anime character) hints whether they’re the youngest or have an older brother, etc.

- tarou 太郎

ichirou 一郎

First-born son. - jirou 次郎

Second-born son. - saburou 三郎

Third-born son. - shirou 四郎

Fourth-born son.

For example, in Uchouten Kazoku, the name of the sons of main character’s family are: Yaichirou, Yajirou, Yasaburou, and Yashirou.

This practice is called haikoumei 輩行名.

Husband

To say husband in Japanese:

- otto 夫

The word above means «husband» literally. The following words are used when referring to one’s husband in person:

Shujin 主人

- shujin 主人

- goshujin ご主人

- goshujinsan ご主人さん

- goshujinsama ご主人様

The word shujin originates from the «lord,» aruji 主, of a home, implying the husband, in which case everyone else in that same home serves the lord, the man of the house.

Although most people don’t really care the term’s origins, some of the working women in modern society may be against its usage, as the word seems rather sexist. It always means husband, never wife, implying you can assume the lord of the house is male. The term onnashujin 女主人 exists for female shujin, but that word is not used to say «wife.»

The term goshujin, with the honorific prefix go 御, would refer to other people’s husbands, as it’s unusual to use honorifics toward yourself. You don’t need to use honorific suffixes (san, sama) with this word.

In anime, the term goshujinsama often refers to a maid’s «master,» in other words, the lord of the house where the maid serves. It’s also used in similar fashion in other contexts.

Dan’na 旦那

- dan’na 旦那

- dan’nasan 旦那さん

- dan’nasama 旦那様

The dan’na words are often used more casually than shujin.

Besides meaning «husband,» the word dan’na may also refer to the master of a house, like shujin, and sometimes it can also refer to the master (owner) of a shop, so long as he is a man.

Besides that, dan’na 旦那, written as dan’na 檀那, means «(male) patron,» and it’s used to refer to male customers of shops. This is similar to how the word «boss» is sometimes used in English to refer to customers, as they’re the ones giving the orders.

Besides that, too, the origin of dan’na 旦那 lies in the word daana ダーナ, loaned from Sanskrit, where it would mean «donation.» Basically donation means patron means customers means «boss» means master of the shop means master of the house means husband.

Father Words

Sometimes, words that would usually mean «father» can be used to refer to one’s husband.

- otousan お父さん

- papa パパ

Anata あなた

Sometimes, the word anata あなた, meaning «you,» is used by wives when talking to their husbands. This contrast with the usual way to refer to people in Japanese: normally you wouldn’t refer to people by you, anata, kimi, etc. and instead refer to them by their names or title (like their profession, etc.)

Note that anata is only used when talking to the husband. There’s no such thing as «my anata» meaning my «husband.»

Groom

To say groom in Japanese:

- muko 婿

(also means son-in-law.)

References

- 夫や主人、旦那の使い分け方。正しい使い分けで一目置かれる妻に! — josei-bigaku.jp

- 「夫」、「ご主人」、「旦那」 この言葉について。 — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

- 「ご主人」はNG?夫婦・パートナーの呼び方あれこれ — allabout.co.jp

- 旦那 — gogen-allguide.com

Wife

To say wife in Japanese:

- tsuma 妻

The word above means «wife» literally. The following words are used to refer to wives:

- yome 嫁

- yomesan 嫁さん

Originally, yome referred to the bride of your son, but nowadays it’s also used to refer to your own bride, or your own wife too.

- okusan 奥さん

- okusama 奥様

The term okusama is normally used to refer to other people’s wives, not yours. Although some people use it to refer to their own wife.

The following terms feel a bit old, but they also exist:

- kamisan 上さん

- kanai 家内

- nyoubou 女房

Mother Words

Sometimes, words that would usually mean «mother» can be used to refer to one’s wife.

- okaasan お母さん

- mama ママ

Bride

To say bride in Japanese:

- yome 嫁

(also means daughter-in-law.)

(note: ore no yome 俺の嫁, «my wife/bride,» is the Japanese equivalent of my waifu)

References

- 「妻・嫁・奥さん・家内」正しい呼び方は?〇〇はNG! 8件 — trend-town.info

In-Laws

The words to refer to in-laws are the following:

- muko 婿

Son-in-law.

Husband of your daughter. - yome 嫁

Daughter-in-law.

Wife of your son.

- shuutome 姑

Mother-in-law.

Mother of your spouse. - shuuto 舅

Father-in-law.

Father of your spouse.

The following words have the «artificial,» gi 義, prefix and have other uses (like adoptive relatives, etc.). But they can be used to refer to in-laws too.

- gibo 義母

giri no haha 義理の母

Mother-in-law. - gifu 義父

giri no chichi 義理の父

Father-in-law.

- gikyoudai 義兄弟

Brothers-in-law.

Siblings-in-law. - gikei 義兄

Older brother-in-law. - gitei 義弟

Younger brother-in-law.

- gishi 義姉

giri no ane 義理の姉

Older sister-in-law. - gimai 義妹

giri no imouto 義理の妹

Younger sister-in-law.

Spouses & Marriage

Some more words about spouses, marriage, husbands and wives:

- haiguusha 配偶者

Spouse. Partner. - paatonaa パートナー

Partner. - fuufu 夫婦

Husband and wife.

Married couple.

- kekkon 結婚

Marriage. - kekkon suru 結婚する

To marry. - X to kekkon suru Xと結婚する

To marry with X.

Brother

To say brother in Japanese there are different words depending on whether they’re your older brother or younger brother.

Older Brother

To say older brother in Japanese:

- ani 兄 [ani vs. oniisan]

- oniisan お兄さん

- oniisama お兄様

- oniisan お兄ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

- aniue 兄上 [chichiue, hahaue, aniue, aneue usage]

- aniki 兄貴 [aniki, aneki usage]

- anija 兄者

- anijahito 兄者人 [兄者, 姉者, 兄者人, 姉者人 usage]

- burazaa ブラザー [katakanizations of family words]

- anchan あんちゃん

Sister Princess

The anime Sister Princess disturbingly features 12 characters pretending they are the younger sister of the main character, and 13 different ways to say «older brother» in Japanese. For reference:

- oniichan お兄ちゃん

- oniichama お兄ちゃま

- onii あにぃ

- oniisama お兄様

- oniitama おにいたま

- aniuesama 兄上様

- niisama にいさま

- aniki アニキ

- anikun 兄くん

- anigimi-sama 兄君さま

- onichama 兄チャマ

- niiya 兄や

- anchan あんちゃん

Younger Brother

To say younger brother in Japanese:

- otouto 弟

The term otoutosan 弟さん is used when talking about the otouto of someone else.

Eldest Brother

An older brother is just any of your brothers older than you. The eldest brother is specifically called:

- choukei 長兄

(see eldest child for explanation)

Youngest Brother

Conversely, the youngest brother among your siblings is called:

- battei 末弟

(see youngest child for explanation)

Sister

To say sister in Japanese there are different words depending on whether they’re your older sister or your younger sister.

Older Sister

To say older sister in Japanese:

- ane 姉 [ane vs. oneesan]

- oneesan お姉さん

- oneesama お姉さま

- oneechan お姉ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

- aneue 姉上 [chichiue, hahaue, aniue, aneue usage]

- aneki 姉貴 [aniki, aneki usage]

- aneja 姉者

- anejahito 姉者人 [兄者, 姉者, 兄者人, 姉者人 usage]

- shisutaa シスター [katakanizations of family words]

Younger Sister

To say younger sister in Japanese:

- imouto 妹

Th term imoutosan 妹さん is used when talking about the imouto of someone else.

Eldest Sister

An older sister is just any of your sister older than you. The eldest sister is specifically called:

- choushi 長姉

(see eldest child for explanation)

Youngest Sister

Conversely, the youngest sister among your siblings is called:

- matsumai 末妹

(see youngest child for explanation)

Siblings

The words for siblings in Japanese are written with the kanji of the words for brothers and sisters.

- kyoudai 兄弟

Brothers. (male)

Siblings. (neutral) - shimai 姉妹

Sisters. - kyoudaishimai 兄弟姉妹

Brothers and sisters.

Siblings.

兄弟, 兄妹, 姉弟, 姉妹

Sometimes, the word kyoudai may be written with different kanji depending on the gender of the siblings, as a gikun, even though the words keimai, shitei and shimai exist.

- kyoudai 兄弟

Older brother, younger brother. - kyoudai 兄妹

keimai 兄妹

Older brother, younger sister. - kyoudai 姉弟

shitei 姉弟

Older sister, younger brother. - kyoudai 姉妹

shimai 姉妹

Older sister, younger sister.

Twins

The word for twins in Japanese is:

- futago 双子

Terms for «multiple birth,» tatai 多胎, of higher numbers include:

- mitsugo 三つ子

Triplets. - yotsugo 四つ子

Quadruplets. - itsutsugo 五つ子

Quintuplets. - mutsugo 六つ子

Sextuplets.

(you know, like in Osomatsu-san おそ松さん) - nanatsugo 七つ子

Septuplets. - yatsugo 八つ子

Octuplets. - kokonotsugo 九つ子

Nonuplets. - juttsugo 十つ子

Decuplets.

References

- 双子、三つ子、四つ子、五つ子、六つ子、七つ子、八つ子、九つ子。 ズバリその次は? — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

Grandfather

To say grandfather in Japanese:

- sofu 祖父 [sofu vs. ojiisan]

- ojiisan お祖父さん

- ojiichan お祖父ちゃん

- ojiisama お祖父様 [san, sama, chan difference]

Sometimes the words above are written with another kanji, for example ojiisan お爺さん. This is usually a way to refer to just any «old man» rather than anyone’s actual grandfather. Just like «grandpa» is sometimes used toward elders in English.

- ooji 祖父 [ooji, ooba usage]

- jii じい

- jiiji じいじ

- jiji 祖父 [jiji, baba usage]

- gaisofu 外祖父

- naisofu 内祖父 [外祖父 vs. 内祖父]

Great-Grandfather

To say great-grandfather in Japanese:

- sou-sofu 曾祖父

hii-jiji 曾祖父

ooooji 大祖父 (seriously? おおおお? Seriously??)

Great-grandfather. - kou-sofu 高祖父

Great-great-grandfather.

(note: there are no common words for greatness above this.)

Grandmother

To say grandmother in Japanese:

- sobo 祖母 [sobo vs. obaasan]

- obaasan お祖母さん

- obaachan お祖母ちゃん

- obaasama お祖母様 [san, sama, chan difference]

When written as obaasan お婆さん, the word refers to a «old woman» familial relationship. The same as «grandma» is used in English.

- ooba 祖母 [ooji, ooba usage]

- baaba ばあば

- baba 祖母 [jiji, baba usage]

- gaisobo 外祖母

- naisobo 内祖母 [外祖母 vs. 内祖母]

Great-Grandmother

To say great-grandmother in Japanese:

- sou-sobo 曾祖母

hii-baba 曾祖母

Great-grandmother. - kou-sobo 高祖母

Great-great-grandmother.

(note: there are no common words for greatness above this.)

Grandchild

To say grandchild in Japanese:

- mago 孫

Grandchild. - magomusuko 孫息子

Grandson. - magomusume 孫娘

Granddaughter.

- gaison 外孫

- naison 内孫 [外孫 vs. 内孫]

Great-Grandchild

To say great-grandchild in Japanese and further:

- himago ひ孫

himago 曾孫

souson 曾孫

Great-grandchild. - yashago 玄孫

genson 玄孫

Great-great-grandchild. - raigon 来孫

Great-great-great-grandchild. - konson 昆孫

Great-great-great-great-grandchild. - jouson 仍孫

Great-great-great-great-great-grandchild. - unson 雲孫

Great-great-great-great-great-great-grandchild.

Isn’t that great?

References

- 子・孫・ひ孫・・・ — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

Grandparents

To say grandparents in Japanese:

- sofubo 祖父母

Grandparents.

Grandfather and [grand]mother.

Great-Grandparents

To say great-grandparents in Japanese:

- sou-sofubo 曽祖父母

Great-grandparents. - kou-sofubo 高祖父母

Great-great-grandparents.

(note: there are no common words for greatness above this.)

Uncle

To say uncle in Japanese, when talking about your parent’s «older brother,» ani 兄:

- oji 伯父 [oji vs. ojisan]

- ojisan 伯父さん

- ojisama 伯父様

- ojichan 伯父ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

To say uncle in Japanese, when talking about your parent’s «younger brother,» otouto 弟:

- oji 叔父 [oji vs. ojisan]

- ojisan 叔父さん

- ojisama 叔父様

- ojichan 叔父ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

To say uncle in Japanese, when calling some random old man «uncle» colloquially even though you’re not related at all: ojisan 小父さん.

(see 叔父, 伯父, 叔母, 伯母 for details.)

Aunt

To say aunt in Japanese, when talking about your parent’s «older sister,» ane 姉:

- oba 伯母 [oba vs. obasan]

- obasan 伯母さん

- obasama 伯母様

- obachan 伯母ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

To say aunt in Japanese, when talking about your parent’s «younger sister,» imouto 妹:

- oba 叔母 [oba vs. obasan]

- obasan 伯母さん

- obasama 叔母様

- obachan 叔母ちゃん [san, sama, chan difference]

The word obasan 小母さん may be used colloquially to refer to random old women, family or not.

(see 叔父, 伯父, 叔母, 伯母 for details.)

Cousin

To say cousin in Japanese:

- itoko いとこ

- itoko 従兄弟

- itoko 従姉妹

- itoko 従兄

juukei 従兄 - itoko 従弟

juutei 従弟 - itoko 従姉

juushi 従姉 - itoko 従妹

juumai 従妹

Just use itoko いとこ or check 従兄弟, 従姉妹, 従兄, 従弟, 従姉, 従妹 for the differences.

Second Cousin

Your first cousins are the children of the siblings of your parents. Your second cousins are the grandchildren of the siblings of your grandparents, To say second cousin in Japanese:

- hatoko はとこ

hatoko 再従兄弟 - mataitoko 又いとこ

- futaitoko 二いとこ

- iyaitoko 弥いとこ

The いとこ part may be written with kanji following the same rules as the word itoko いとこ, «cousin.»

The word hatoko is a jukujikun 熟字訓 that somehow managed to be written with 3 kana (はとこ) but 4 kanji (再従兄弟). Very exceptional. Anyway, it works the same as its synonyms. You can change the 従兄弟 part in 再従兄弟 depending on the second cousin.

References

- 「再従兄弟」は何と読む? 平仮名で書いた方が字数が少ない「コスパが悪い熟語」 — nlab.itmedia.co.jp

Nephew

To say nephew in Japanese:

- oi 甥

- oikko 甥っ子

- oigo 甥御

Niece

To say niece in Japanese:

- mei 姪

- meikko 姪っ子

- meigo 姪御

Nephew & Niece

To refer to any nephews or nieces you may or may not have:

- oimei 甥姪

In other words: kyoudai-shimai no kodomo 兄弟姉妹の子供, «children of your brothers and sisters.»

Adopted Family

- koji 孤児

Orphan.

- yashinau 養う

To adopt (a child, not an idea, attitude, etc.). - youshi-engumi 養子縁組

Adoption. - youshin 養親

Adoptive parent (or parents.) - youshi 養子

Adopted child. - youfubo 養父母

Adoptive father and mother.

Adoptive parents. - youjo 養女

Adopted daughter. - youka 養家

Adoptive family.

Generally speaking, jitsu 実, «real,» implies someone is related by blood, while gi 義 and giri 義理 implies they are not related by blood.

For example:

- giri no haha 義理の母

gibo 義母

Stepmother.

Foster mother.

Mother-in-law. - giri no chichi 義理の父

gifu 義父

Stepfather.

Foster father.

Father-in-law. - giri no kyoudai 義理の兄弟

Stepbrothers.

Foster brothers.

Brothers-in-law.

And so on. Some examples of the counterpart:

- jitsu no imouto 実の妹

jitsumai 実妹

Younger sister related by blood. Biological younger sister. - jitsu no ani 実の兄

jikkei 実兄

Older brother related by blood. Biological older brother.

By the way, chi no tsunagari 血の繋がり, literally «connection of blood,» refers to blood relationships.

Nuances, Usage & Differences

Honorifics

A number of words for family members have honorifics suffixes that can change between san, chan and sama. For example:

- otousan, otouchan, otousama

- okaasan, okaachan, oksaama

- oniisan, oniichan, oniisama

- oneesan, oneechan, oneesama

- ojiisan, ojiichan, ojiisama

- obaasan, obaachan, obaasama

- ojisan, ojichan, ojisama

- obasan, obachan, obasama

These words all refer to the same thing regardless of suffix. That is: oniisan, oniisama, and oniichan all mean «older brother.» Likewise, oneesan, oneesama, and oneechan all mean «older sister.»

The difference between them is in nuance.

The san suffix may be regarded as neutral. The sama suffix is more formal, traditional, respectful, and puts a distance between the speaker and the person they’re referring to. Meanwhile, the chan suffix is less formal, and more intimate, friendly, chummy instead, implying closeness between the speaker and whom they’re referring to.

Cues in Anime

In anime, the suffix used may hint the relationship between the characters and show an aspect of their family.

For example: when calling fathers, mothers, older siblings with sama, it implies respect. This may mean the family places importance in tradition. Like a rich family where children are educated to say «father,» and not just «dad,» as that may sound ridiculous if heard by others.

In some cases, an older brother or sister being called with sama implies the younger sibling has excessive admiration for them.

On the other side, using chan implies it’s a cozier family where rigid norms don’t really matter. Toward parents, it may imply a good relationship with them. Or it may imply it’s a poor family. Or one from the countryside.

(In Rose of The Versailles, one character is ridiculed in a royal court for calling their parent with -chan.)

Referring to siblings with chan implies the closeness likewise. Sometimes this is done mockingly.

父 vs. お父さん, 母 vs. お母さん

A number of Japanese words for family members have versions with and without honorifics. For example:

- chichi and otousan

- haha and okaasan

- ani and oniisan

- ane and oneesan

- sofu and ojiisan

- sobo and obaasan

There’s no difference between these words in meaning. Both chichi and otousan mean «father.» Both haha and okaasan mean «mother.» The difference between chichi and otousan, haha and okaasan, etc. is in how they are used.

Basically, it follows the golden rule that you don’t use honorifics toward yourself, except on a familial level instead.

The versions with honorifics, otousan, okaasan, etc. are used only when talking to someone inside the family, «relatives,» miuchi 身内, while the versions without honorifics, chichi, haha, etc. are used outside the family, «other people,» tanin 他人.

For example:

- If you are talking to your father,

you use otousan. - If you are talking to your mother,

about your father,

you use otousan. - If you are talking to your brothers,

about your father,

you use otousan. - If you are talking to someone you met on the street,

about your father,

you use chichi.

Following that, if you’re talking about someone else’s relatives, you may use honorifics too.

For example:

- watashi no chichi to anata no otousan 私の父とあなたのお父さん

My father and your father.

This means that, when one character is talking to someone they are not related to, chichi refers to their father, while otousan refers to the father of whom they’re talking to.

Note that to some people mistaking the usage described above makes you look like you weren’t properly taught how to use the words. Also note that some people do mistake how the words are used. And some people do not mind how they are used. So it’s a really tricky set of words.

References

- お父さんお母さん、父母の使い分け — oshiete.goo.ne.jp

- 家族の呼び方と身内と他人に使う敬語の違い — careerpark.jp

パパ, ママ

Some children use the terms papa and mama instead of otousan and okaasan to refer to their own parents.

You might imagine this would only be a trivial fraction of all children, as papa and mama are obviously western words, surely otouchan and okaachan or something more Japanese-sounding would be more adequate?

However, a good portion of the families (39.8% according to the referenced data) have their children use papa and mama inside the family, when not talking to people outside the family.

Note that the word mama まま also means «the way something is.»

References

- パパ・ママ派が約4割。5割はお父さん・お母さん — benesse.jp

父親, 母親

The terms chichioya and hahaoya differ from haha and chichi in the way they’re used.

When you use chichi and haha, you’re talking about what a person, who happens to be a father or a mother, is doing. That is, it’s merely a way to refer to them, to describe them. You can replace these words by their names every time and the phrase would still make sense.

«Mother went to X,» for example.

Meanwhile, chichioya and hahaoya refer to parents as parents, acting in their capacity as parents. They can be used, for example, to speak generally: «a mother would do this,» or, «mothers do this.»

Furthermore, there are cases where chichioya and hahaoya refer to one’s parents, not parents in general. In this case, the terms are used because they feel more general, therefore more distant, and lack the intimate aspect of chichi and haha.

In other words: chichi and haha sound too casual when compared to chichioya and hahaoya, so people use the oya words instead in situations they want to avoid sounding too cozy.

References

- 自分の「父親」と「父」、「母親」と「母」の使い分け — oshiete.goo.ne.jp

親父, お袋

The terms oyaji and ofukuro mean «father» and «mother» respectively. They’re used mostly by men, not by women.

In anime, characters calling their fathers oyaji are common. Some of them have a rebel personality, making the term oyaji sound like a disrespectful word. In fact, some people in real life think the term is impolite.

That isn’t necessarily true. Sure, these terms aren’t exactly full of reverence, however, they’re often simply the way people end up calling their parents. It doesn’t imply they respect them less or more. It can imply they have a closer relationship, maybe, but it would be wrong to assume someone who says oyaji is in bad terms with their father.

Sometimes, suffixes are added to the words: oyajisan 親父さん, ofukurosan お袋さん. The contraction oyassan おやっさん also exists.

References

- 自分の親に「親父」「お袋」と呼ぶのは、今まで育ててくれた親に対して失礼で非常識だと思いますか? — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

- 男性はよく「お袋の味」といいますが — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

父上, 母上, 兄上, 姉上

There are some Japanese terms for family members that end in ue 上. They’re simply the non-ue version with ue added to it.

- chichi and chichiue.

- haha and hahaue.

- ani and aniue.

- ane and aneue.

The words above infer reverence, as ue 上 means above. So they’re generally used toward seniors. The words for son, daughter and younger brother, younger sister do not have ue 上 versions.

The difference between chichi and chichiue, haha and hahaue, etc. is in how they’re used. There’s no difference in meaning. Both chichi and chichiue mean «father,» and so on.

The words with ue, chichiue, hahaue, aniue, aneue, are not used in modern times. They were more common in the Meiji era (before 1912). Nowadays chichi and the other non-ue words are used more instead.

So if you have to choose, choose the words without ue.

In writing, the ue words may still be used, just not in speech. Also note that some families still prefer to use the ue words instead, but that’s just some particular cases and not the general situation.

In anime, fiction, etc., specially theater pieces, the usage of chichiue, hahaue, aniue, aneue indicates the character comes from a very traditional family, or that they’re somehow anachronistic. Like they time-traveled to or from the Meiji era or something.

References

- お父さん(おとうさん)/パパ/父上(ちちうえ)/おやじ — dictionary.goo.ne.jp

父君, 母君

The words fukun, also read chichigimi, and hahagimi, are ways to refer with reverence to a father and a mother.

These words are like chichiue and hahaue: they’re rather old, they aren’t used much in speech, and they are found more in writing.

One difference, however, is that chichiue and hahaue are used to refer to your own parents, while chichigimi and hahagimi are used to refer to someone else’s parents.

References

- 父君(ふくん)/父君(ちちぎみ)/父御(ちちご)/尊父(そんぷ)/御親父(ごしんぷ) — dictionary.goo.ne.jp

父御, 母御

The words chichigo and hahago are just like chichigimi and hahagimi, used to refer to other people’s parents, mainly used in writing, except the terms feel a bit older-fashioned.

The word chichigo is also read as tetego.

尊父, 御親父

The words sonpu and and goshinpu are mainly used to refer to the parents of whom you’re talking. These are also words of reverence, and also used more in writing.

ファーザー, マザー, シスター, ブラザー

The words faazaa, mazaa, shisutaa, and burazaa are katakanizations of the English words «mother,» «father,» «sister,» and «brother.»

Although these words aren’t really used in real life to refer to people’s family, they’re often seen in loaned words that make use of them, like «motherboard,» for example.

More often, these words refer to another type of relationship. For example, shisutaa can refer to a «nun,» like «sister» sometimes does in English.

In anime, there are cases where characters may call their family by these words but that’s just anime being anime.

兄貴, 姉貴

The words aniki and aneki refer to a brother and a sister respectively. These words are like aniue and aneue, they refer to them with reverence, except they are still used in speech to this day.

The reason for this is probably that aniki and aneki are sometimes used to refer not to one’s real brother, but just to an older guy or girl whom they respect. That is: it’s basically senpai, the «bro» version, and its female counterpart.

In particular, in anime it’s common for gang members to call their boss aniki, even if that boss is just a middle-management kinda boss and he has a bossier gang boss himself. Likewise, girl gangs would use aneki.

兄者, 姉者, 兄者人, 姉者人

The words anija and aneja are words used in the past to refer to the «older brother» and «older sister» respectively. They aren’t used in modern speech, but you may see it in songs, anime, manga, etc.

They’re abbreviations of anijahito 兄者人 and anejahito 姉者人.

Since these words infer reverence to whom they refer to, they exist only for the seniors, the older brother and older sister.

Words such otoja 弟者, which would be the «younger brother» variant, probably did not exist when onija and oneja were in use,. Instead, it’s possible they were made up in modern times. Remember: onija and oneja are still used in fiction, music, etc. today. So someone, knowing onija was a word, figured otoja would be a word too.

References

- 兄者、って、 弟が兄を呼ぶのに — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

お坊ちゃん, お嬢さん

The terms obocchan and ojousan are two separate words that have similar usage. They refer to someone else’s son and daughter respectively, and they’re used in reverence.

The origin of obocchan seems to come from «Buddhist priests,» bouzu 坊主. Because of their iconic crew cut hairstyle, the term «bouzu head,» bouzu-atama 坊主頭, even came to mean that. And young boys, who had such hairstyle, ended up being called obocchan affectionately.

This is why obocchan, with the affectionate chan, often refers to the son of someone, while obousan, with a simple san, rather refers to a Buddhist priest.

The word ojousan, on the other hand, normally refers to someone’s daughter, simply put. But it can be used in other ways too.

For example, sometimes ojousan refers to a young woman whose name is unknown.

Because the terms obocchan and ojousama refer to children but have honorifics, they’ve come to be associated with children of rich families. After all, among lesser enriched families people wouldn’t waste time with such pleasantries.

In anime, it’s often butlers, maids, etc. that call the children of their masters these words:

- obocchan おぼっちゃん

- obocchama おぼっちゃま

- ojouchan お嬢ちゃん

- ojousan お嬢さん

- ojousama お嬢様

Since these terms are associated with rich children, it’s sometimes the case of saying someone is an obocchan or ojousama mockingly if they appear to be from a rich family. In this case you aren’t really saying «son» or «daughter,» it’s more like a slang that implies they’re snobby, or have a different social position, tastes, etc.

References

- 「お坊ちゃん」と「お坊さん」 — detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

おおじ, おおば

The terms ooji and ooba are used to refer to a grandfather and grandmother respectively. These terms come from oochichi 大父, literally «great father,» and oohaha 大母, «great mother,» respectively.

じじ, ばば

The terms jiji, baba are used to refer to a grandfather and a grandmother respectively. The terms jii じい and jiiji じいじ are distortions of jiji じじ, while baaba ばあば is a distortion of baba ばば.

These terms are usually associated with children, who eventually stop using these words and start saying something else when they grow up. This isn’t always the case, however, as there are adults who use them too.

Some people consider these terms a bit rude, believing ojiisan and obaasan should be used instead.

外祖父, 内祖父, 外祖母, 内祖母, 外孫, 内孫

Historically, Japan has a system where the one true heir of a given family is usually be the «oldest son,» chounan 長男, the «first-born son,» ichinan 一男.

Since this heir would inherit everything of the family, the family business, firms, heirlooms, cursed swords with demons sealed inside, houses, properties, style of martial arts, assets, etc. the heir would probably have to stay home learning about his ancestry and the techniques that have been passed down his family line for generations.

Meanwhile, the daughters and the younger sons would go away and get married off into other families.

Because of this, there’s a practice of calling the heirs of the family line «inside,» uchi 内, since they stay inside the family, and those that married into the family «outside,» soto 外, since they come from outside the family. This can be seen in the following words:

- nai-sofu 内祖父

- nai-sobo 内祖母

- nai-son 内孫

uchi-mago 内孫 - gai-sofu 外祖父

- gai-sobo 外祖母

- gai-son 外孫

soto-mago 外孫

The easiest way to tell these apart is the surname, or family name.

If your grandparent had to changed their family name to yours, they’re from «outside» and entered the family. If your grandchild has a different surname than yours, they’ve left your family and gone «outside.»

Generally speaking, the child of your son is «inside» while the child of your daughter is «outside.»

An exception happens when a mukoyoushi 婿養子 is involved, which is a husband that takes the wife’s family name. If your son is a mukoyoushi, he changed his family name, so his child is going to be «outside» your family. Conversely, if your daughter marries a mukoyoushi, she keeps your family name, so her child would be «inside» your family.

The practice of calling heirs this way has fallen out of usage since World War II, probably because it became less relevant in modern times. Because of this, not everyone knows the words’ original meanings.

Instead, they’ll assume a gaisofu always means the maternal grandfather, as it normally means that, even though there’s a possibility that’s not the case.

For example, if your father is mukoyoushi, then gaisofu would be your paternal grandfather, because your mother kept her family name. Since you inherited the family name from your mother, you were born «inside» your mother’s family, and «outside» your father’s family. Consequently, your mother parents are «inside» and your father parents «outside.»

References

- 内孫と外孫の違いを教えて下さい。

- 外祖父と祖父の違いがよくわからないのです

叔父, 伯父, 叔母, 伯母

In Japanese, the words «uncle,» oji, «aunt,» oba, and their derivatives may be written with different kanji: 伯父 and 叔父 for oji, 伯母 and 叔母 for oba.

The difference between 伯父 and 叔父 is that 伯父 is your «mother or father’s older brother,» fubo no ani 父母の兄, while 叔父 is your «mother or father’s younger brother,» fubo no otouto 父母の弟.

Likewise, the difference between 伯母 and 叔母 is that 伯母 is your «mother or father’s older sister,» fubo no ane 父母の姉, while 叔母 is your «mother or father’s younger sister,» fubo no imouto 父母の妹.

Why Different Kanji?

The truth is there aren’t Japanese words for your «parent’s younger brother» and for your «parent’s older brother.» There’s only one single word for both cases: oji, your «parent’s brother.»

The reason it gets written differently according to the seniority is because kanji were imported from China, and in the Chinese language (I guess) there’s one word for the younger brother uncle and one word for the older brother uncle.

So Chinese had four words while Japanese only has two, oji and oba. This mismatch is why there are extra ways to write the same Japanese word and those extra ways bear different meaning according to their Chinese origins.

従兄弟, 従姉妹, 従兄, 従弟, 従姉, 従妹

The word for cousin in Japanese, itoko いとこ, may be written with different kanji depending on what it refers to.

When written with just the kanji for older brother, younger brother, older sister, or younger sister, it implies the gender and age of the cousin in question. In this case, the age refers to whether the cousin is older or younger than you (or if you say X’s cousin, older or younger than X.)

- itoko 従兄

Older male cousin. - itoko 従弟

Younger male cousin. - itoko 従姉

Older female cousin. - itoko 従妹

Younger female cousin.

Those kanji can be combined, just like in the words «brothers,» kyoudai 兄妹, or «sisters,» shimai 姉妹, in which case it refers to:

- itoko 従兄弟

Male cousins. - itoko 従姉妹

Female cousins. - itoko 従兄妹

One male cousin and his younger sister. - itoko 従姉弟

One female cousin and her younger brother.

Why Itoko Has So Many Kanji?

The reason why the word itoko words this way is because in Chinese there are actually different words depending on the cousin and the kanji combinations stem from how those words are written in hanzi..

Basically, there’s just one common Japanese word, itoko, for all those Chinese counterparts, which is why itoko becomes gikun

Sometimes those words can get read with on’yomi instead, changing depending on the kanji, for example:

- juukei 従兄

- juutei 従弟

- juushi 従姉

- juumai 従妹

References

- 「いとこ」の漢字の使い分けを教えてください。 — chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp

Otou-san is just the tip of the paternal iceberg.

Just like the U.S., Japan celebrates Father’s Day on the third Sunday in June. The way Japan celebrates it is pretty similar too: presents, dinner out, and a greater willingness to just let dad relax and sip his beer in peace while relaxing on the couch and watching golf on TV.

Some things are still uniquely Japanese, though. With Father’s Day coming at the start of the summer, a nice jinbei (a traditional Japanese roomwear garment) is a popular present, and some of the top restaurant picks are yakiniku or kaitenzushi (revolving sushi) joints. And of course, they don’t call it “Father’s Day” in Japan, since there’s a Japanese word for “father.”

Well, actually, there are a ton of different ways to say “father” in Japanese, and what better day to take a look at them than today?

1. otou-san / お父さん

Technically we’re going to look at five different but related terms here in entry #1.

If you’ve ever taken an introductory Japanese class, or watched many J-dramas or anime, this is probably the first one you learned. Otou-san is the most common, broadly usable phrase for father/dad in Japanese.

At the same time, it’s actually just one of many arrangements in a surprisingly flexible system. -san is the standard suffix to show politeness when talking about a person in Japan, but if you want to kick the politeness/formality up a notch, you can change it to otou-sama. On the other hand, if you want to go the other way and make it sound more sweetly affectionate, you can say otou-chan (though that one’s most commonly used by little kids). As a quick-and-simple rough equivalency list you can generally think of otou-san as “dad,” otou-sama as “father,” and otou-chan as “daddy.”

Speaking of politeness, the o at the start of otou-san is itself a politeness-boosting prefix, so you can remove it and just say tou-san or tou-chan. Tou-sama, however, is a combination you’ll never hear, since -sama itself is too formal to fit with the dropped o.

One important thing to keep in mind: since politeness towards others and humility regarding yourself/your own family are considered good manners in Japanese culture, when you’re talking about someone else’s father, it’s best to stick with otou-san or otou-sama, the most polite options. Out of the two, otou-san is usually the wisest choice, since otou-sama can sound a little baroque, and it’s also best to avoid otou-sama when talking about your own dad, since it can make you sound conceited about your father’s status, or perhaps intimidated by his stature.

2. chichi / 父

Our second way to say father, chichi, is actually written with the exact same kanji character as the “tou” part of otou-san (父), just with no additional hiragana characters in front of or behind it. That unfettered status makes chichi the most absolutely neutral way to say father in Japanese, and so the lack of added politeness means you usually don’t use it to talk about someone else’s dad.

However, there’s a school of thought that you absolutely should use chichi when talking about your own dad once you reach adulthood. The logic is that otou-san and its various alternate forms are all, to some extent, terms of respect. As such, if you’re talking to someone else and use the term otou-san to refer to your own father, the linguistic implication is that you’re saying that your dad occupies a position of higher respect than the person you’re talking to.

If you’re a little kid talking to another little kid, that’s not an issue, since adults are generally in a position of authority compared to children. But if you’re a full-grown adult talking to another adult, it’d be kind of presumptuous to talk as though your dad is in a position that demands the other person’s respect like it’s a matter of course, and so chichi, in some people’s minds, becomes the better choice for talking about your own dad in grown-up conversations.

All that said, “you shouldn’t use otou-san for talking about your own dad to other people” is an admittedly old-school way of thinking, and a guideline that younger Japanese people are increasingly less likely to adhere to or worry about. And last, chichi is the word used in the Japanese term for father’s day, Chichi no Hi.

3. papa / パパ

Yep, papa. Just like in English and many European languages, papa is now readily understood in Japanese. It does, however, have a very childish ring to it, and so it’s something that most kids, especially boys, start growing out of by the time they finish elementary school. Some women continue to use it into adulthood, but even then primarily when speaking directly to their father or other family members, not in conversations with other people, to avoid being seen as a daddy’s girl.

4. oyaji / 親父 / おやじ

Oyaji is really two vocabulary words in one. Written with the kanji characters for “parent” (親) and “father” (父), it not only means dad, but is also a generic term for a middle-aged or elderly man.

Oyaji is the roughest-sounding term on our list, but said with enough warmth in your voice, it can also radiate a certain masculine jovialness, and is almost exclusively used by men.

▼ Pictured: Mr. Sato’s dad, who he calls “oyaji”

In English, oyaji is closest to “pop” or “pops.” In keeping with that casualness, while oyaji can be written in kanji, you’ll also often see it written in hiragana, which has a less formal feel. And yes, you may have also heard oyaji as part of the phrase “ero oyaji” (“dirty old man”).

5. oton / おとん

As we move further down the list, we’re also moving farther out into the countryside. To people from Tokyo and east Japan, oton has a decidedly country bumpkin feel, sort of like “pa” in English.

But oton isn’t strictly for yokels, and as you head west from Tokyo, you’ll start to hear it used by people who speak Kansai dialect, the style of Japanese prevalent in and around Osaka. That said, oton always carries a bit of a rustic feeling, and while some may say that’s just backwoods charm, it’ll probably earn a few chuckles if you say it in a formal situation.

6. chichiue / 父上

On the surface, chichiue looks like it shouldn’t be all that different from chichi. After all, it’s just the same “dad” kanji as chichi (父) with 上, meaning “up” or “above,” tacked onto the end. So it’s just a polite way of saying father, right?

Sure…if you happen to be a samurai. Chichiue is an extremely old-fashioned way of speaking, and it’s more or less like saying “exalted father.”

7. chichioya / 父親

And last, we come to chichioya. Written by reversing the kanji for oyaji, putting “father” first and “parent” second. Chichioya is a useful term for talking about fathers in a general or societal sense, perhaps in a prepared announcement or written statement. Generally, though it’s not so commonly used in conversation to talk about a specific person’s father, and especially not your own.

So just like when we looked at the different ways to say “love,” once again Japanese proves itself to be a seriously deep language. Thanks for reading, and happy Father’s Day to you and your dad, whatever you call him.

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: Pakutaso (1, 2, 3), SoraNews24, Pakutaso (5)

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Casey didn’t have space to point out that no one ever says otou-kun in the article, but you can follow him on Twitter anyway.

- Words

- Sentences

Definition of father

-

(n) father; dad; papa; pa; pop; daddy; dada

お父さんは煙草の煙でたくさん輪を作れる。

Dad can blow many smoke rings.

- (n) father; male parent

- (n) father

-

(n) father

私の父は大の旅行ずきです。

My father is a great traveler.

-

(n) father (esp. used in samurai families prior to the Meiji period)

あなたのお父上にお会いするのを楽しみにしています。

I’m looking forward to seeing your father.

-

(n) father

その少年は父親に似ている。

The boy takes after his father.

- (n) old man; venerable gentleman

- (suf) venerable; old; father

-

(n) father; dad; papa; pa; pop; daddy; dada

彼は父さんほど背が高くない。

He is not as tall as his father.

- (n) father

- (n) (another’s respected) father

- (n) father (term commonly used until the end of the Meiji period); Dad

- (n) father

-

(n) father

お父さまがお亡くなりになったそうで。

I’m sorry to hear that your father passed away.

- (n) father

- (n) father

- (n) father; priest

- (n) father (used by children of court nobles and noble families)

- (n) father

- (n) mother; father; parent

- (n) daddy; father; husband

- (n) father

- (n) father; male parent

- father‘s room