All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

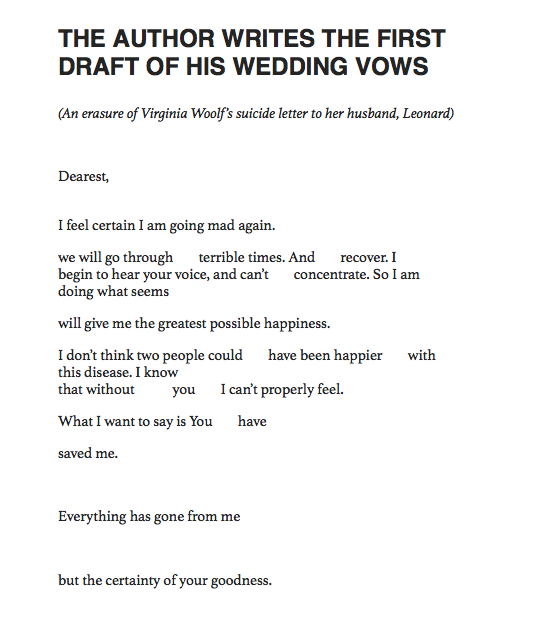

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

When writing academically, the most precise choice is most often the right one. When two words can convey the same idea, the shortest and clearest option is usually the wisest.

The process of choosing what to write involves a lot of consideration. Writing a paper requires choosing a topic, selecting a method, selecting resources, and setting up the main idea; then, when it’s time to write, selecting the words and structuring them.

Choosing the right words seems obvious, but selecting the right words will change your writing tone and content. There are several approaches to consciously choosing words, and we will explore them in this article.

Why is it important to choose the right words when writing?

There are two types of meanings for words: denotative and connotative. Definition and usage are referred to as denotation. Associating, connecting, and using words are described by their connotations. When it comes to using words in academia, these factors can be very important.

When writing a publication, using the right words is essential to its effectiveness. It is imperative to make choices when writing academically, just as when writing in other forms. The phrase, sentence, or even paragraph that most accurately conveys your argument is the first thing you should choose when you’re writing.

Readers are more likely to understand a concept when the word choice is meaningful or striking. The purpose of it is to provide clarity, convey, and enhance concepts. There are several factors that can limit an author’s ability to convey accurate information through their word choice.

Use the right words and the right images together to boost your paper’s potential

Using the right images is just as important as the right words. Beautiful designs and scientifically accurate images can also be decisive when it comes to publishing a successful science paper. Try using Mind the Graph to easily create your visuals and take your work to another level.

The best ways to avoid making mistakes with your word choice

Your reader will have difficulty understanding what you meant when you use misused words or grammar structures. If there is “ambiguity”, “vagueness” or “Unclarity” in these words, they may be ineffective. Writers know what they intend to say, but readers know only what they actually said. Therefore, it is very important to avoid making such mistakes.

Your word choice should always be based on your audience’s understanding. Thus, it is unsuitable to use slang, geographical terms, endearments, and jargon in academic writing. Avoid any phrase that is uncertain about the audience’s understanding.

When proofreading your work, keep your readers’ perspective in mind. Matching the terminology of your subject matter is also important. Clarity and concision are only part of establishing your credibility as an author.

Words can often obscure your meaning if you use too many. A larger amount of material to read and analyze makes it more difficult to read and understand your writing. If your writing has extra words, try to eliminate them.

Keep your tone positive without sounding overly assertive. If you want to brainstorm while you write, you can use the slash/option technique. If you’re stuck on a word or a sentence, write out two or more alternatives. Getting a sense of the right tone of wording for your paper is best done by writing it in at least two ways.

Word choice examples and guide

Jargon

Jargon is an unintuitive, sometimes deliberate way of confusing words or expressions in order to influence a reader’s interpretation. Example: Patients suffered from high fevers and many side effects due to diseases, which they could not handle. (too many words describing the same idea when it could just be a simple sentence,” The disease caused severe symptoms in patients.)

Clichés

When a phrase becomes so common that its meaning is lost, it is called a cliché. A very typical example is “the grass is always greener on the other side” or “last but not least”, do not use it in academic writing.

Big Words

Using big words might sound fancy, but they don’t add meaning rather lead to an inability to comprehend a subject.

Generally used adjectives and adverbs

Appropriate adjectives and adverbs hold quantifiable meanings. Therefore, it is best to use words that describe the context and are accurate.

Wordiness

If your text is too wordy, the reader has to skim through more text to find the main implications of the paper.

Bring words to life with the power of visual

Exactly, we have many templates for every type of science visual communication. Save time by working smarter. The illustrations we offer can be customized to meet your specific needs, and we have a wide range of categories to choose from. With Mind the Graph, science communication is easier than ever before.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual

communication in science.

— Exclusive Guide

— Design tips

— Scientific news and trends

— Tutorials and templates

G ood word choice is about precision and personality; the words you choose help define your voice.

How word choice shapes your voice

You’ve buckled down to write your content. You’re proud of your ideas.

But when you read your draft … it kind of sucks. A spark is missing. The content sounds blah. It doesn’t sound like you at all.

Makes you want to cry?

Cultivating an engaging voice may feel like an arduous, perhaps even painful journey.

But when you nurture a sense of play, that excruciating journey turns into a fun adventure.

While experimenting with words, you’ll find your voice. And when you’ve found your voice, your content stands out in a drab sea of grey words. Fierce. And proud.

Want to know how to have fun with words and find your voice?

Why word choice can feel tricky

Most of us tend to choose safe words—the words popping in our mind first. These are the words everyone is using.

Everyday language is a good idea, because readers can quickly grasp your ideas. But when you use only everyday language, your content doesn’t stand out. You sound like everyone else. Your content lacks sparkle.

Writing is different from talking. When we speak we use hand gestures and facial expressions to add emotion and meaning to our words. But when we write, we can’t wink, we can’t smile, we can’t slam the table, and we can’t put our hands up in the air.

So, our written words have to work harder. Our words have to whisper or shout. Our words have to attract attention and engage. Our words have to express emotion.

This is why you need to infuse your writing with more emotional words, with colorful language, with a sensory touch. You need to push yourself gently outside your comfort zone and play with different words.

Examples of word choice

Have you ever studied how others choose their words?

And have you noticed how their words give you an impression of their personality?

Below follow snippets from a sales page for a fitness book of DragonDoor. What type of personality comes across?

- How to construct a barn door back—and walk with loaded guns

- How to take a trip to hell—and steal a Satanic six-pack

- How to guarantee steel rod fingers

- Time to deliver the final bullet to those aching muscles: the Crucifix pull—brilliant and very painful!

The DragonDoor copy uses strong sensory and emotional words like “loaded guns,” “bullet,” “trip to hell,” “Satanic,” and “steel rod.”

Now, let’s compare this to a sales page for a yoga teaching class of Balance Yoga and Wellness. Try to imagine the type of teacher who’s written this:

- Heart-centered yoga: Learn the foundations of Anusara yoga, including the loops and spirals, universal principles and more.

- Balance your body and mind: Learn and apply ayurvedic principles to your diet and lifestyle so you get healthier and happier. Improve your sleep and digestion so your energy invigorates your students and others around you.

- Spark your creativity: Make your own mala bracelets, eye pillows, clay models, and yantras. Tapping into your creative center will help to infuse a sense of playfulness into your teaching.

This copy uses softer and more positive words like “invigorate,” “heart-centered,” “spark,” “balance,” “healthier,” “happier,” and “tap into.”

Choosing your words isn’t just about being precise and concise. The words you choose also give an impression of your personality; they define your voice.

How do you want to come across? How do you want to interact with your audience?

How word choice shapes your voice

Below follow four questions to consider when considering how words shape your voice.

1. Do you use jargon or everyday language?

Whether you want to use jargon or not mainly depends on the experience of your readers. Do they understand your technical terms?

DragonDoor uses some technical language like “pecs,” “hanging straight leg raises,” “stand-to-stand bridges,” and “progressive calisthenics.” For instance:

Why mastery of progressive calisthenics is the ultimate secret for building maximum raw strength

Balance Yoga and Wellness also assumes you know basic yoga terms:

Open the doors to yoga philosophy, including Tantra, Samkhya, Hatha Yoga and key texts

When considering your word choice, consider your audience. Which words would they use? Do they understand technical language and jargon? Also, consider whether your audience would appreciate slang or not.

2. Do you appeal to negative or positive emotions?

Positive or negative word choice has a big impact on how readers perceive your voice and your personality.

DragonDoor, for instance, addresses readers’ fears of doing things wrong or acting like a “baby-weight pumper” or “wannabee.” They might make you feel insecure:

- Do you make this stupid mistake with your push ups? This is wrong, wrong, wrong!

- This little fella will really separate the iron men from the baby-weight pumpers!

- These Gecko pushups truly separate the wannabees from the real thing

- Obey these important caveats before you start bridging—or risk injury

- The dumb, fickle, want-it-yesterday way to fail in your long term Convict Conditioning training

Balance Yoga and Wellness uses a positive tone of encouragement instead:

You may think that you aren’t cut out to teach yoga. Or that you aren’t advanced enough. But this is far from the truth. During our course you develop your own yoga practice. You build skills and grow in self-confidence.

Do you want to agitate and stir up fear? Or comfort, encourage, and soothe? How positive do you want to sound?

3. Do you use strong or subtle sensory words?

DragonDoor uses strong language, borrowing terminology from prisons and war:

- One crucial reason why a lot of convicts deliberately avoid weight-training

- Bar pulls—an old convict favorite for good reason

- How to effectively bulletproof the vulnerable rotator cuff muscles

- Transform skinny legs into pillars of power, complete with steel cord quads, rock-hard glutes and thick, shapely calves

The copy of Balance Yoga and Wellness strikes a warmer tone:

Do you nurture an intense love for yoga?

Are you astonished how much your life has improved since you stepped into your first yoga class?

You gained strength, flexibility and fitness. You tapped into a deep calmness, and experienced a new sense of peace and inner beauty.

Now, what’s next?

(…) Our Teacher Training helps you nourish a deeper understanding of yoga, delve into human anatomy, and gain the confidence to share the magic of yoga with your friends and family and community.

How do you spice up your content? With fight analogies? Or cooking metaphors? With hints of seduction? Or warmongering?

4. How much curiosity do you arouse?

DragonDoor arouses curiosity with phrases like “little-known ways,” “a dormant superpower,” and a “jealously-guarded system:”

- The dormant superpower for muscle growth waiting to be released if you only do this

- Try this little-known way to make stand-to-stand bridges harder and increasingly more explosive without adding any external resistance

- A jealously-guarded system for going from puny to powerful—when your life may depend on the speed of your results

The copy of Balance Yoga and Wellness is more straightforward about what you’ll learn and why:

- Sequence a yoga class: Use creativity and knowledge of yoga postures to develop a balanced yoga class.

- Use language effectively: Learn effective verbal cues for leading a yoga class.

- Breakdown key yoga postures: Talk students into and out of yoga postures, what the fundamental alignment cues are for each postures.

- Teach safely: Appreciate how our anatomy impacts different types of yoga postures, and learn how to modify yoga postures to avoid injury.

Curiosity-arousing phrases change the tone of your writing. Moreover, curiosity can nudge readers to take action—to satisfy their curiosity.

But it’s a fine balance as too much curiosity arousal can make your content flimsy, pushy, and hypey. In contrast, pairing benefits with features makes your content more substantial, straightforward, and honest.

A word choice exercise: Get out of a writing funk

Ready to explore your voice?

And play with different words?

Try the exercise below and experiment with your word choice. Try to impersonate different personalities. Also, pay attention to how your voice changes when you borrow phrases from, for instance, cooking, fighting, dating, or sports.

Word choice exercise

Complete the following sentence:

I’m a … and I’m on a mission to …

Examples:

The standard, drab version:

I’m a copywriter on a mission to improve web content.

The power-puncher:

I write powerful copy for explosive conversions and skyrocketing sales.

Another strong-armed copywriter:

I write damn good copy for businesses who must stand out in cut-throat competition.

The competitor:

I write the ultimate sales-boosting copy so you can give your competitors the middle finger.

The sparkling personality:

I’m a creative copywriter on a mission to add sparkle to boring web content.

The seductress:

I write copy so seductive your favorite clients fall in love with your work.

The sensory cook:

I cook up delicious copy, zesty emails, and tasty blog posts to help you grow your business.

The quiet rebel:

I’m an irreverent copywriter on a mission to stamp out gobbledygook.

Have fun with as many options as you like. Leave the options percolating overnight, and choose a favorite the next day. Consider adding your mission statement to your social media bios and About page.

Playing with words is like trying new clothes

Pick up a different style, try it on, and see how it looks in the mirror.

Does that jacket make you feel confident? Does that fuchsia scarf make you feel more creative? Wanna try a bolder style? Or a different color?

Playing with words puts the fun back into writing.

It enlivens our copy. And invigorates our soul.

Have fun!

FREE 22-page ebook

How to Choose Words With Power and Pizzazz

- Discover 4 wordy rules for captivating your audience

- Learn how to fortify and energize your message

- Get examples that show you how to spice up your writing

Get My Free Ebook >>

PS Thank you to Darren DeMatas of Selfstartr for inspiring this post.

The words a writer chooses are the building materials from which he or she constructs any given piece of writing—from a poem to a speech to a thesis on thermonuclear dynamics. Strong, carefully chosen words (also known as diction) ensure that the finished work is cohesive and imparts the meaning or information the author intended. Weak word choice creates confusion and dooms a writer’s work either to fall short of expectations or fail to make its point entirely.

Factors That Influence Good Word Choice

When selecting words to achieve the maximum desired effect, a writer must take a number of factors into consideration:

- Meaning: Words can be chosen for either their denotative meaning, which is the definition you’d find in a dictionary or the connotative meaning, which is the emotions, circumstances, or descriptive variations the word evokes.

- Specificity: Words that are concrete rather than abstract are more powerful in certain types of writing, specifically academic works and works of nonfiction. However, abstract words can be powerful tools when creating poetry, fiction, or persuasive rhetoric.

- Audience: Whether the writer seeks to engage, amuse, entertain, inform, or even incite anger, the audience is the person or persons for whom a piece of work is intended.

- Level of Diction: The level of diction an author chooses directly relates to the intended audience. Diction is classified into four levels of language:

- Formal which denotes serious discourse

- Informal which denotes relaxed but polite conversation

- Colloquial which denotes language in everyday usage

- Slang which denotes new, often highly informal words and phrases that evolve as a result sociolinguistic constructs such as age, class, wealth status, ethnicity, nationality, and regional dialects.

- Tone: Tone is an author’s attitude toward a topic. When employed effectively, tone—be it contempt, awe, agreement, or outrage—is a powerful tool that writers use to achieve a desired goal or purpose.

- Style: Word choice is an essential element in the style of any writer. While his or her audience may play a role in the stylistic choices a writer makes, style is the unique voice that sets one writer apart from another.

The Appropriate Words for a Given Audience

To be effective, a writer must choose words based on a number of factors that relate directly to the audience for whom a piece of work is intended. For example, the language chosen for a dissertation on advanced algebra would not only contain jargon specific to that field of study; the writer would also have the expectation that the intended reader possessed an advanced level of understanding in the given subject matter that at a minimum equaled, or potentially outpaced his or her own.

On the other hand, an author writing a children’s book would choose age-appropriate words that kids could understand and relate to. Likewise, while a contemporary playwright is likely to use slang and colloquialism to connect with the audience, an art historian would likely use more formal language to describe a piece of work about which he or she is writing, especially if the intended audience is a peer or academic group.

«Choosing words that are too difficult, too technical, or too easy for your receiver can be a communication barrier. If words are too difficult or too technical, the receiver may not understand them; if words are too simple, the reader could become bored or be insulted. In either case, the message falls short of meeting its goals . . . Word choice is also a consideration when communicating with receivers for whom English is not the primary language [who] may not be familiar with colloquial English.»

(From «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

Word Selection for Composition

Word choice is an essential element for any student learning to write effectively. Appropriate word choice allows students to display their knowledge, not just about English, but with regard to any given field of study from science and mathematics to civics and history.

Fast Facts: Six Principles of Word Choice for Composition

- Choose understandable words.

- Use specific, precise words.

- Choose strong words.

- Emphasize positive words.

- Avoid overused words.

- Avoid obsolete words.

(Adapted from «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

The challenge for teachers of composition is to help students understand the reasoning behind the specific word choices they’ve made and then letting the students know whether or not those choices work. Simply telling a student something doesn’t make sense or is awkwardly phrased won’t help that student become a better writer. If a student’s word choice is weak, inaccurate, or clichéd, a good teacher will not only explain how they went wrong but ask the student to rethink his or her choices based on the given feedback.

Word Choice for Literature

Arguably, choosing effective words when writing literature is more complicated than choosing words for composition writing. First, a writer must consider the constraints for the chosen discipline in which they are writing. Since literary pursuits as such as poetry and fiction can be broken down into an almost endless variety of niches, genres, and subgenres, this alone can be daunting. In addition, writers must also be able to distinguish themselves from other writers by selecting a vocabulary that creates and sustains a style that is authentic to their own voice.

When writing for a literary audience, individual taste is yet another huge determining factor with regard to which writer a reader considers a «good» and who they may find intolerable. That’s because «good» is subjective. For example, William Faulker and Ernest Hemmingway were both considered giants of 20th-century American literature, and yet their styles of writing could not be more different. Someone who adores Faulkner’s languorous stream-of-consciousness style may disdain Hemmingway’s spare, staccato, unembellished prose, and vice versa.

Making Better Word Choices — 4 Examples

by: David J. Clapham

Writers face many decisions when working on a project. Choosing the correct word for a certain situation is one choice that writers often either struggle with or make an incorrect choice. This article will give some basic guidance to writers on four of the more common word choices that authors face.

Choosing the wrong words can have a poor effect on your writing and on you. Whether you are writing a cover letter for a job, a business proposal, or an application essay for graduate school using words poorly can result in negative feedback. One could find entire books regarding word choices for writers, this article will touch on some fundamental, but important ways to choose the correct word for your situation.

Our starting point will be the use of «There are» or «There is» to begin sentences. Consider this; the word «there» indicates «not here» (in other words, some other place). Now look at the sentence below and think about what the meaning is and what might be intended.

There are four dogs playing with a ball.

If the writer meant that four dogs are over there and they are playing with a ball, then this would be technically correct. If the intention was merely that four dogs are playing with a ball, here, there, or anywhere, then the sentence could be worded better. The following sentence would show better wording on the writer’s part.

Four dogs are playing with a ball.

The next two words that writers often confuse are «which» and «that.» If the goal of your writing is to describe something and you have used commas to separate the phrase from the rest of the sentence you want to use «which.» When a writer wants a word to define and the reference is restricted then you want to use «that.» The first sentence below shows the correct use of «that» and the second sentence shows correct use of «which.»

The Yodo is the river that runs through Osaka.

The Yodo, which is a major waterway, runs though Osaka.

Our next word choice is between «while» and «although.» Another way of thinking about the word «although» is to look at its meaning, as found on Merriam-Webster Online dictionary the meaning is, «in spite of the fact that : even though.»(1) The definition of «while» indicates a relation to time, such as during a period when something else is happening. Two correctly worded sentences are below.

Although he is not tall, he is a good basketball player.

While he listened to the radio, he finished his homework.

A writer’s choice between «since» and «because» also involves the possibility of a reference to time. Many people use «since» when they really mean «because,» this is rarely a correct use of the word «since.» When choosing a word to suggest «from a definite past time until now»(1) use «since.» If you are not referring to time, «because» should be the word you choose. Try using «because,» if your sentence does not make sense then you probably want to use «since.» In the examples below the two incorrect sentences do not sound correct, while the correct sentences actually sound better.

Incorrect: He had few friends since he was too annoying.

Correct: He had few friends because he was too annoying.

Incorrect: He has not ridden a bicycle because 1990.

Correct: He has not ridden a bicycle since 1990.

Whether you are writing an essay for school or you are writing a speech for your CEO, choose your words carefully because what people hear or read from you can make a big difference in their opinion about you and your intelligence. For anyone writing, regardless of topic, length, or purpose, ask for assistance if you need it, not doing so can have serious repercussions on your reputation.

About The Author

David Clapham is the owner of Blue Arch Consulting, a proofreading and editing business helping clients worldwide to generate English documents of all types. Their website is at http://www.blue-arch.net.