The best way to understand word and morpheme, when they become rather confusing, is through understanding the difference between the two, the word and the morpheme. A language consists of various elements such as sentences, words, syllables, morphemes, etc. A morpheme is usually considered as the smallest element of a word or else a grammar element, whereas a word is a complete meaningful element of language. The difference between the two is that while a word always conveys a meaning, in the case of a morpheme, this is doubtful. It can sometimes convey a meaning and sometimes not. This article attempts to highlight this difference through a description of the two terms.

What is a Morpheme?

A morpheme refers to the smallest meaningful element of a word. A morpheme cannot be further broken into parts. For example, chair, dog, bird, table, computer are all morphemes. As you can see they express a direct meaning yet cannot be further separated into smaller parts. However, a morpheme is not similar to a syllable as it carries a meaning. For example, when we say giraffe, it consists of a number of syllables but a single morpheme. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes a single word can carry a number of morphemes. Let us try to understand this through an example. If we take the word ‘regained’, this word consists of 3 morphemes. They are, ‘re’ , ‘gain’ and ‘ed’.

Chair is a Morpheme

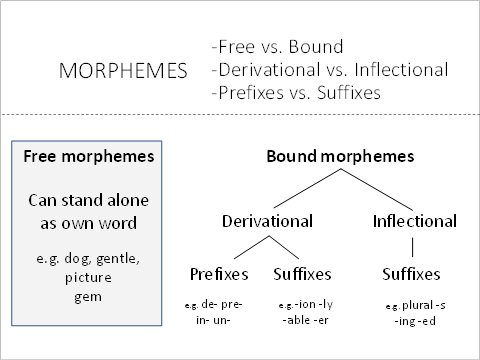

In linguistics, we speak of different varieties of morphemes. They are free morphemes and bound morphemes. Free morphemes refer to those that can stand as a single word. Nouns, adjectives can be considered as free morphemes (brush, chalk, pen, act, find). Bound morphemes cannot stand alone. They are usually attached to other forms. Prefixes and suffixes are examples for bound morphemes (re, ly, ness, pre, un, dis).

What is a Word?

A word can be defined as a meaningful element of a language. Unlike a morpheme, it can always stand alone. A word can consist of a single morpheme or a number of morphemes. For example, when we say ‘reconstruct,‘ it is a single word, but it is not a single morpheme but two morphemes together (‘re‘ and ‘construct‘). When forming phrases or sentences, we use a number of words. For example, when we say ‘Didn’t you hear, he has been reassigned to the head office,’ it is a combination of words that convey a meaning to the reader. But, let us take a single word from the sentence, ‘reassigned’; this once again conveys a complete meaning. But even though this is a single word, it consists of a number of morphemes. They are, ‘re’ , ‘assign’, ‘ed’. This is the main difference between a morpheme and a word.

Re (Morpheme) + Construct (Morpheme) = Reconstruct (Word)

What is the difference between Word and Morpheme?

• A morpheme is the smallest meaningful part of a word.

• A word is a separate meaningful unit, which can be used to form sentences.

• The main difference is that while a word can stand alone, a morpheme may or may not be able to stand alone.

Images Courtesy:

- Chair via Wikicommons (Public Domain)

Morphology is the study of words, word formation, and the relationship between words. In Morphology, we look at morphemes — the smallest lexical items of meaning. Studying morphemes helps us to understand the meaning, structure, and etymology (history) of words.

Morphemes: meaning

The word morphemes from the Greek morphḗ, meaning ‘shape, form‘. Morphemes are the smallest lexical items of meaning or grammatical function that a word can be broken down to. Morphemes are usually, but not always, words.

Look at the following examples of morphemes:

These words cannot be made shorter than they already are or they would stop being words or lose their meaning.

For example, ‘house’ cannot be split into ho- and -us’ as they are both meaningless.

However, not all morphemes are words.

For example, ‘s’ is not a word, but it is a morpheme; ‘s’ shows plurality and means ‘more than one’.

The word ‘books’ is made up of two morphemes: book + s.

Morphemes play a fundamental role in the structure and meaning of language, and understanding them can help us to better understand the words we use and the rules that govern their use.

How to identify a morpheme

You can identify morphemes by seeing if the word or letters in question meet the following criteria:

-

Morphemes must have meaning. E.g. the word ‘cat’ represents and small furry animal. The suffix ‘-s’ you might find at the end of the word ‘cat’ represents plurality.

- Morphemes cannot be divided into smaller parts without losing or changing their meaning. E.g. dividing the word ‘cat’ into ‘ca’ leaves us with a meaningless set of letters. The word ‘at’ is a morpheme in its own right.

Types of morphemes

There are two types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes

Free morphemes can stand alone and don’t need to be attached to any other morphemes to get their meaning. Most words are free morphemes, such as the above-mentioned words house, book, bed, light, world, people, and so on.

Bound morphemes

Bound morphemes, however, cannot stand alone. The most common example of bound morphemes are suffixes, such as —s, —er, —ing, and -est.

Let’s look at some examples of free and bound morphemes:

-

Tall

-

Tree

-

-er

-

-s

‘Tall’ and ‘Tree’ are free morphemes.

We understand what ‘tall’ and ‘tree’ mean; they don’t require extra add-ons. We can use them to create a simple sentence like ‘That tree is tall.’

On the other hand, ‘-er’ and ‘-s’ are bound morphemes. You won’t see them on their own because they are suffixes that add meaning to the words they are attached to.

So if we add ‘-er’ to ‘tall’ we get the comparative form ‘taller’, while ‘tree’ plus ‘-s’ becomes plural: ‘trees’.

Morphemes: structure

Morphemes are made up of two separate classes.

-

Bases (or roots)

-

Affixes

A morpheme’s base is the main root that gives the word its meaning.

On the other hand, an affix is a morpheme we can add that changes or modifies the meaning of the base.

‘Kind’ is the free base morpheme in the word ‘kindly’. (kind + -ly)

‘-less’ is a bound morpheme in the word ‘careless’. (Care + —less)

Morphemes: affixes

Affixes are bound morphemes that occur before or after a base word. They are made up of suffixes and prefixes.

Suffixes are attached to the end of the base or root word. Some of the most common suffixes include —er, -or, -ly, -ism, and -less.

Taller

Thinner

Comfortably

Absurdism

Ageism

Aimless

Fearless

Prefixes come before the base word. Typical prefixes include ante-, pre-, un-, and dis-.

Antedate

Prehistoric

Unkind

Disappear

Derivational affixes

Derivational affixes are used to change the meaning of a word by building on its base. For instance, by adding the prefix ‘un-‘ to the word ‘kind‘, we got a new word with a whole new meaning. In fact, ‘unkind‘ has the exact opposite meaning of ‘kind’!

Another example is adding the suffix ‘-or’ to the word ‘act’ to create ‘actor’. The word ‘act’ is a verb, whereas ‘actor’ is a noun.

Inflectional affixes

Inflectional affixes only modify the meaning of words instead of changing them. This means they modify the words by making them plural, comparative or superlative, or by changing the verb tense.

books — books

short — shorter

quick — quickest

walk — walked

climb — climbing

There are many derivational affixes in English, but only eight inflectional affixes and these are all suffixes.

|

Word class |

Modification reason |

Suffixes |

| To modify nouns | Plural & possessive forms | -s (or -es), -‘s (or s’) |

| To modify adjectives |

Comparative & superlative forms |

-er, -est |

| To modify verbs |

3rd person singular, past tense, present & past participles |

-s, -ed, -ing, -en |

All prefixes in English are derivational. However, suffixes may be either derivational or inflectional.

Morphemes: categories

The free morphemes we looked at earlier (such as tree, book, and tall) fall into two categories:

- Lexical morphemes

- Functional morphemes

Reminder: Most words are free morphemes because they have meaning on their own, such as house, book, bed, light, world, people etc.

Lexical morphemes

Lexical morphemes are words that give us the main meaning of a sentence, text or conversation. These words can be nouns, adjectives and verbs. Examples of lexical morphemes include:

- house

- book

- tree

- panther

- loud

- quiet

- big

- orange

- blue

- open

- run

- talk

Because we can add new lexical morphemes to a language (new words get added to the dictionary each year!), they are considered an ‘open’ class of words.

Functional morphemes

Functional (or grammatical) morphemes are mostly words that have a functional purpose, such as linking or referencing lexical words. Functional morphemes include prepositions, conjunctions, articles and pronouns. Examples of functional morphemes include:

- and

- but

- when

- because

- on

- near

- above

- in

- the

- that

- it

- them.

We can rarely add new functional morphemes to the language, so we call this a ‘closed’ class of words.

Allomorphs

Allomorphs are a variant of morphemes. An allomorph is a unit of meaning that can change its sound and spelling but doesn’t change its meaning and function.

In English, the indefinite article morpheme has two allomorphs. Its two forms are ‘a’ and ‘an’. If the indefinite article precedes a word beginning with a constant sound it is ‘a’, and if it precedes a word beginning with a vowel sound, it is ‘an’.

Past Tense allomorphs

In English, regular verbs use the past tense morpheme -ed; this shows us that the verb happened in the past. The pronunciation of this morpheme changes its sound according to the last consonant of the verb but always keeps its past tense function. This is an example of an allomorph.

Consider regular verbs ending in t or d, like ‘rent’ or ‘add’.

Now look at their past forms: ‘rented‘ and ‘added‘. Try pronouncing them. Notice how the —ed at the end changes to an /id/ sound (e.g. rent /ɪd/, add /ɪd/).

Now consider the past simple forms of want, rest, print, and plant. When we pronounce them, we get: wanted (want /ɪd/), rested (rest /ɪd/), printed (print /ɪd/), planted (plant /ɪd/).

Now look at other regular verbs ending in the following ‘voiceless’ phonemes: /p/, /k/, /s/, /h/, /ch/, /sh/, /f/, /x/. Try pronouncing the past form and notice how the allomorph ‘-ed’ at the end changes to a /t/ sound. For example, dropped, pressed, laughed, and washed.

Plural allomorphs

Typically we add ‘s’ or ‘es’ to most nouns in English when we want to create the plural form. The plural forms ‘s’ or ‘es’ remain the same and have the same function, but their sound changes depending on the form of the noun. The plural morpheme has three allomorphs: [s], [z], and [ɨz].

When a noun ends in a voiceless consonant (i.e. ch, f, k, p, s, sh, t, th), the plural allomorph is /s/.

Book becomes books (pronounced book/s/)

When a noun ends in a voiced phoneme (i.e. b, l, r, j, d, v, m, n, g, w, z, a, e, i, o, u) the plural form remains ‘s’ or ‘es’ but the allomorph sound changes to /z/.

Key becomes keys (pronounced key/z/)

Bee becomes bees (pronounced bee/z/)

When a noun ends in a sibilant (i.e. s, ss, z), the sound of the allomorph sound becomes /iz/.

Bus becomes buses (bus/iz/)

house becomes houses (hous/iz/)

A sibilant is a phonetic sound that makes a hissing sound, e.g. ‘s’ or ‘z’.

Zero (bound) morphemes

The zero bound morpheme has no phonetic form and is also referred to as an invisible affix, null morpheme, or ghost morpheme.

A zero morpheme is when a word changes its meaning but does not change its form.

In English, certain nouns and verbs do not change their appearance even when they change number or tense.

Sheep, deer, and fish, keep the same form whether they are used as singular or plural.

Some verbs like hit, cut, and cost remains the same in their present and past forms.

Morphemes — Key takeaways

- Morphemes are the smallest lexical unit of meaning. Most words are free morphemes, and most affixes are bound morphemes.

- There are two types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

- Free morphemes can stand alone, whereas bound morphemes must be attached to another morpheme to get their meaning.

- Morphemes are made up of two separate classes called bases (or roots) and affixes.

- Free morphemes fall into two categories; lexical and functional. Lexical morphemes are words that give us the main meaning of a sentence, and functional morphemes have a grammatical purpose.

2. Synthetic means of form-building.

3. Analytical forms.

1. The main task of morphology

is the study of the structure of words. The sinallesl significant

(meaningful) units of grammar are called morghemes.

Morphemes are commonly

classified into free (those which can occur as separate words) and

bound. A word consisting of a single (free) morpheme is

monomorphemic, its opposite is polymorphemic.

According to their meaning

and, function morphemfes are subdivided into lexical (roots),

lexico-grammatical (word-building affixes ) and grammatical

(form-building affexes, or inflexions)

Morphemes

are abstract units, respresented in speech by morphs. Most morphemes

are realized by single morphs: un-self-ish.

Some morphemes may be manifested by more than one morph according to

their position. Such alternative morphs, or positional variants of a

morpheme are called allomorphs: cats, [s], dog’s [z], foxes [iz],

oxen.

Morphemic variants are

identified in the text on the basis of their co-occurence with other

morphs, or their environment. The total of environments constitutes

the distribution.

There may

be three types of morphemic distribution: contrastive,

non-contrastiye, conplementary Morphs are in coutrastive distribution

if their position is the same and their meanings are different:

charming

— charmed.

Morphs are in non-contrastive distribution if their position is the

same and their meanings are the same: learned

— learnt.

Such morphs constitute free variants of the same morpheme. Morphs are

in complementary distribution if their positions are different and

their meanings are the same: speaks.

-teaches.

Such morphs are allomorphs of the same morpheme.

Grammatical

meanings may be expressed by the absence of the morpheme. Compare:

book

— books.

The meaning of plurality is expressed by the morpheme —s.

The meaning of singularity is expressed by the absence of the

morpheme. Such meaningful absence of the morpheme is called

zero-morpheme.

The

function of the morpheme may be performed by a separate word. In the

opposition work

— will work

the meaning of the future is expressed by the word will.

Will is a contradictory unit. Formally it is a word, functionally it

is a morpheme. As it has the features of a word and a morpheme, it is

called a word morpheme. Word-morphemes may be called semi-bound

morphemes.

2. Means of form-building and

grammatical forms are divided into synthetic and analytical.

Synthetic forms are built with

the help of bound morphemes, analytical forms are built with the help

of semi-bound morphemes (word-morphemes).

Synthetic means of

form-building are affixation, sound-interchange (inner-inflexion),

suppletivity.

Typical

features of English affixation are scarcity and homonymy of affixes.

Another characteristic feature is a great number of zero-morphemes.

Though .English grammatical

affixes are few in number, affixation is a productive means of

form-building.

Sound

interchange may be of two types: vowel- and consonant-interchange. It

is often accompanied by affixation: bring

— brought.

Sound interchange is not

productive in Modern English. It is used to build the forms of

irregular verbs.

Forms of

one word may be derived from different roots: go

— went, I— me, good — better.

This means of form-building is called suppletivity. Different roots

may be treated as suppletive forms if:

1) they have the same lexical

meaning;

2) there are no parallel

non-suppletive forms;

3) other words of the same

class build their forms without suppletivity.

Suppletivity, like

inner-inflexion, is not productive in Modern English, but it occurs

in words with a very high frequency.

3.

Analytical forms are combinations of the auxiliary element (a word

-morpheme) and the notional element; is

writing.

Analytical forms are

contradictory units: phrases in form and wordforms in function.

In the

analytical form is

writing

the auxiliary verb be

is lexically empty. It expresses the grammatical meaning. The

notional element expresses both the lexical and the grammatical

meaning. So the grammatical meaning is expressed by the two

components of the analytical form: the auxiliary verb be

and the affix —ing..

The word-morpheme be

and the inflexion —ing

constitute

a discontinuous morpheme.

Analytical forms are

correlated with synthetic forms. There must be at least one synthetic

form in the paradigm.

Analytical forms have

developed from free phrases and there are structures which take an

intermediary position between free phrases and analytical forms: will

go, more beautiful.

The abundant use of analytical

forms, especially in the system of the verb, is the characteristic

feature of Modern English.

TOPIC IV

Parts

of Speech

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Definition of Morpheme

A morpheme is the smallest syntactical and meaningful linguistic unit that contains a word, or an element of the word such as the use of –s whereas this unit is not divisible further into smaller syntactical parts.

For instance, in the sentence, “It was the best of times; it was the worst of times” (A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens), all the underlined words are morphemes, as they cannot be divided further into smaller units.

Types of Morpheme

There are two types of morphemes which are:

- Free Morpheme

The free morpheme is just a simple word that has a single morpheme; thus, it is free and can occur independently. For instance, in “David wishes to go there,” “go” is a free morpheme. - Bound Morpheme

By contrast to a free morpheme, a bound morpheme is used with a free morpheme to construct a complete word, as it cannot stand independently. For example, in “The farmer wants to kill duckling,” the bound morphemes “-er,” “s,” and “ling” cannot stand on their own. They need free morphemes of “farm,” “want” and “duck” to give meanings.

Bound morphemes are of two types which include:

- Inflectional Morpheme

This type of morpheme is only a suffix. It transforms the function of words by adding -ly as a suffix to the base of the noun, such as in “friend,” which becomes “friendly.” Now it contains two morphemes “friend” and “-ly.” Here, “-ly” is an inflectional morpheme, as it has changed the noun “friend” into an adjective “friendly.” - Derivational Morpheme

This type of morpheme uses both prefix as well as suffix, and has the ability to change function as well as meaning of words. For instance, adding the suffix “-less” to the noun “meaning” makes the meaning of this word entirely different.

Examples of Morpheme in Literature

Example #1: Hamlet (by William Shakespeare)

“Sit down awhile;

And let us once again assail your ears,

That are so fortified against our story

What we have two nights seen.

Before my God, I might not this believe

Without the sensible and true avouch

Of mine own eyes.”

All the underlined words in this example are bound morphemes, as they cannot exist independently. For instance, “awhile” is a combination of two morphemes “a” and “while.” Similarly, “again,” “nights,” and “before” are combinations of two morphemes each.

Example #2: Tyger Tyger (by William Blake)

“Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

In this example, all of the underlined words are bound morphemes. The second one, “immortal,” and the third one, “fearful,” have changed functions and meanings after the addition of suffixes. “Fearful” is an inflectional morpheme, and it has changed this noun into an adjective.

Example #3: For Whom the Bell Tolls (by Earnest Hemingway)

“The young man, who was studying the country, took his glasses from the pocket of his faded, khaki flannel shirt, wiped the lenses with a handkerchief, screwed the eyepieces around until the boards of the mill showed suddenly clearly and he saw the wooden bench beside the door; the huge pile of sawdust that rose behind the open shed where the circular saw was, and a stretch of the flume that brought the logs down from the mountainside on the other bank of the stream.”

In this passage, all the underlined words “studying,” “handkerchief,” “suddenly,” “clearly,” “wooden,” “beside,” and “mountainside” are bound morphemes.

Example #4: Master of the Game (by Sidney Sheldon)

“Jamie McGregor was one of the dreamers. He was barely eighteen, a handsome lad, tall and fair-haired, with startlingly light gray eyes. There was an attractive ingenuousness about him, an eagerness to please that was endearing. He had a light-hearted disposition and a soul filled with optimism.”

This passage is another good example of bound morphemes. The underlined words “dreamers,” “barely,” “handsome,” “fair-headed,” “eagerness,” “light-hearted,” and “filled” are bound morphemes.

Function of Morpheme

A morpheme is a meaningful unit in English morphology. The basic function of a morpheme is to give meaning to a word. It may or may not stand alone. When it stands alone, it is thought to be a root. However, when it depends upon other morphemes to complete an idea, then it becomes an affix and plays a grammatical function. Besides, inflectional and derivational morphemes can transform meanings and functions of the words respectively adding richness and beauty to a text.

Morphology is the study of words and their parts. Morphemes, like prefixes, suffixes and base words, are defined as the smallest meaningful units of meaning. Morphemes are important for phonics in both reading and spelling, as well as in vocabulary and comprehension.

Why use morphology

Teaching morphemes unlocks the structures and meanings within words. It is very useful to have a strong awareness of prefixes, suffixes and base words. These are often spelt the same across different words, even when the sound changes, and often have a consistent purpose and/or meaning.

Types of morphemes

Free vs. bound

Morphemes can be either single words (free morphemes) or parts of words (bound morphemes).

A free morpheme can stand alone as its own word

- gentle

- father

- licence

- picture

- gem

A bound morpheme only occurs as part of a word

- -s as in cat+s

- -ed as in crumb+ed

- un- as in un+happy

- mis- as in mis-fortune

- -er as in teach+er

In the example above: un+system+atic+al+ly, there is a root word (system) and bound morphemes that attach to the root (un-, -atic, -al, -ly)

system = root un-, -atic, -al, -ly = bound morphemes

If two free morphemes are joined together they create a compound word. These words are a great way to introduce morphology (the study of word parts) into the classroom.

For more details, see:

Compound words

Inflectional vs. derivational

Morphemes can also be divided into inflectional or derivational morphemes.

Inflectional morphemes change what a word does in terms of grammar, but does not create a new word.

For example, the word <skip> has many forms: skip (base form), skipping (present progressive), skipped (past tense).

The inflectional morphemes -ing and -ed are added to the base word skip, to indicate the tense of the word.

If a word has an inflectional morpheme, it is still the same word, with a few suffixes added. So if you looked up <skip> in the dictionary, then only the base word <skip> would get its own entry into the dictionary. Skipping and skipped are listed under skip, as they are inflections of the base word. Skipping and skipped do not get their own dictionary entry.

Skip

verb, skipped, skipping.

- to move in a light, springy manner by bounding forward with alternate hops on each foot. to pass from one point, thing, subject, etc.,

- to another, disregarding or omitting what intervenes: He skipped through the book quickly.

- to go away hastily and secretly; flee without notice.

From

Dictionary.com — skip

Another example is <run>: run (base form), running (present progressive), ran (past tense). In this example the past tense marker changes the vowel of the word: run (rhymes with fun), to ran (rhymes with can). However, the inflectional morphemes -ing and past tense morpheme are added to the base word <run>, and are listed in the same dictionary entry.

Run

verb, ran, run, running.

- to go quickly by moving the legs more rapidly than at a walk and in such a manner that for an instant in each step all or both feet are off the ground.

- to move with haste; act quickly: Run upstairs and get the iodine.

- to depart quickly; take to flight; flee or escape: to run from danger.

From

Dictionary.com — run

Derivational morphemes are different to inflectional morphemes, as they do derive/create a new word, which gets its own entry in the dictionary. Derivational morphemes help us to create new words out of base words.

For example, we can create new words from <act> by adding derivational prefixes (e.g. re- en-) and suffixes (e.g. -or).

Thus out of <act> we can get re+act = react en+act = enact act+or = actor.

Whenever a derivational morpheme is added, a new word (and dictionary entry) is derived/created.

For the <act> example, the following dictionary entries can be found:

Act

noun

- anything done, being done, or to be done; deed; performance: a heroic act.

- the process of doing: caught in the act.

- a formal decision, law, or the like, by a legislature, ruler, court, or other authority; decree or edict; statute; judgement, resolve, or award: an act of Parliament.

From

Dictionary.com — act

React

verb

- to act in response to an agent or influence: How did the audience react to the speech?

- to act reciprocally upon each other, as two things.

- to act in a reverse direction or manner, especially so as to return to a prior condition.

From

Dictionary.com — react

Enact

verb

- to make into an act or statute: Parliament has enacted a new tax law.

- to represent on or as on the stage; act the part of: to enact Hamlet.

From

Dictionary.com — enact

Actor

noun

- a person who acts in stage plays, motion pictures, television broadcasts, etc.

- a person who does something; participant.

From

Dictionary.com — actor

Teachers should highlight and encourage students to analyse both Inflectional and Derivational morphemes when focussing on phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.

For more information, see:

Prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases

Many morphemes are very helpful for analysing unfamiliar words. Morphemes can be divided into prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases.

- Prefixes are morphemes that attach to the front of a root/base word.

- Suffixes are morphemes that attach to the end of a root/base word, or to other suffixes (see example below)

- Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning.

- Generally, base words are free morphemes, that can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

- Whereas root words are bound morphemes that cannot stand by themselves (e.g. -ject as in subject/reject, and -volve as in evolve/revolve).

Most morphemes can be divided into:

- Anglo-Saxon Morphemes (like re-, un-, and -ness);

- Latin Morphemes (like non-, ex-, -ion, and -ify); and

- Greek Morphemes (like micro, photo, graph).

It is useful to highlight how words can be broken down into morphemes (and which each of these mean) and how they can be built up again).

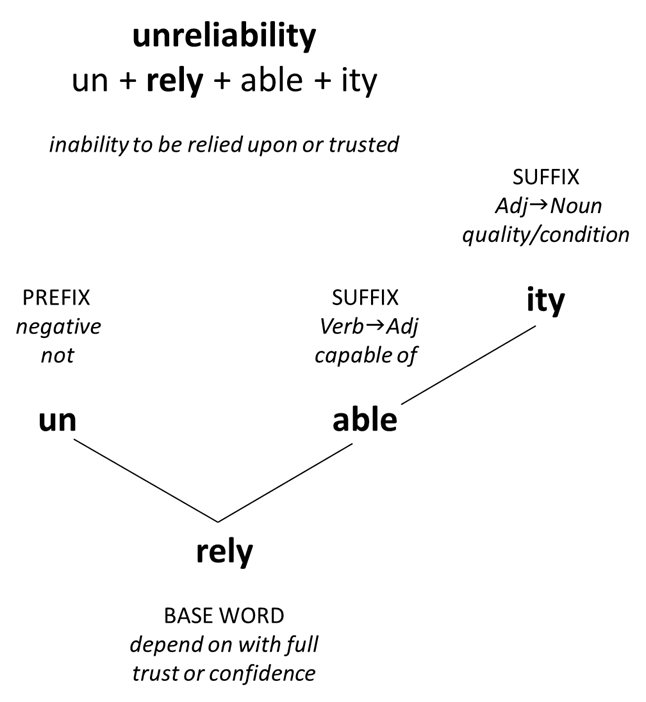

For example, the word <unreliability> may be unfamiliar to students when they first encounter it.

If <unreliability> is broken into its morphemes, students can deduce or infer the meaning.

So it is helpful for both reading and spelling to provide opportunities to analyse words, and become familiar with common morphemes, including their meaning and function.

Compound words

Compound words (or compounds) are created by joining free morphemes together. Remember that a free morpheme is a morpheme that can stand along as its own word (unlike bound morphemes — e.g. -ly, -ed, re-, pre-). Compounds are a fun and accessible way to introduce the idea that words can have multiple parts (morphemes). Teachers can highlight that these compound words are made up of two separate words joined together to make a new word. For example dog + house = doghouse

Examples

- lifetime

- basketball

- cannot

- fireworks

- inside

- upside

- footpath

- sunflower

- moonlight

- schoolhouse

- railroad

- skateboard

- meantime

- bypass

- sometimes

- airport

- butterflies

- grasshopper

- fireflies

- footprint

- something

- homemade

- backbone

- passport

- upstream

- spearmint

- earthquake

- backward

- football

- scapegoat

- eyeball

- afternoon

- sandstone

- meanwhile

- limestone

- keyboard

- seashore

- touchdown

- alongside

- subway

- toothpaste

- silversmith

- nearby

- raincheck

- blacksmith

- headquarters

- lukewarm

- underground

- horseback

- toothpick

- honeymoon

- bootstrap

- township

- dishwasher

- household

- weekend

- popcorn

- riverbank

- pickup

- bookcase

- babysitter

- saucepan

- bluefish

- hamburger

- honeydew

- thunderstorm

- spokesperson

- widespread

- hometown

- commonplace

- supermarket

Example activities of highlighting morphemes for phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension

There are numerous ways to highlight morphemes for the purpose of phonics, vocabulary and comprehension activities and lessons.

Highlighting the morphology of words is useful for explaining phonics patterns (graphemes) and spelling rules, as well as discovering the meanings of unfamiliar words, and demonstrating how words are linked together. Highlighting and analysing morphemes is also useful, therefore, for providing comprehension strategies.

Examples of how to embed morphological awareness into literacy activities can include:

- Sorting words by base/root words (word families), or by prefixes or suffixes

- Word Detective — Students break longer words down into their prefixes, suffixes, and base words

- e.g. Find the morphemes in multi-morphemic words like: dissatisfied unstoppable ridiculously hydrophobic metamorphosis oxygenate fortifications

- Word Builder — students are given base words and prefixes/suffixes and see how many words they can build, and what meaning they might have:

- Prefixes: un- de- pre- re- co- con-

Base Words: play help flex bend blue sad sat

Suffixes: -ful -ly -less -able/-ible -ing -ion -y -ish -ness -ment - Etymology investigation — students are given multi-morphemic words from texts they have been reading and are asked to research the origins (etymology) of the word. Teachers could use words like progressive, circumspect, revocation, and students could find out the morphemes within each word, their etymology, meanings, and use.