Содержание

- Work with Events using the Excel JavaScript API

- Events in Excel

- Events in preview

- Event triggers

- Lifecycle of an event handler

- Events and coauthoring

- Register an event handler

- Handle an event

- Remove an event handler

- Enable and disable events

- Create application-level event handlers in Excel

- Summary

- More information

- Creating and Initiating the Event Handler

- How to Turn Off the Event Handler

- Events in the Excel Object Model

Work with Events using the Excel JavaScript API

This article describes important concepts related to working with events in Excel and provides code samples that show how to register event handlers, handle events, and remove event handlers using the Excel JavaScript API.

Events in Excel

Each time certain types of changes occur in an Excel workbook, an event notification fires. By using the Excel JavaScript API, you can register event handlers that allow your add-in to automatically run a designated function when a specific event occurs. The following events are currently supported.

| Event | Description | Supported objects |

|---|---|---|

| onActivated | Occurs when an object is activated. | Chart, ChartCollection, Shape, Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onActivated | Occurs when a workbook is activated. | Workbook |

| onAdded | Occurs when an object is added to the collection. | ChartCollection, CommentCollection, TableCollection, WorksheetCollection |

| onAutoSaveSettingChanged | Occurs when the autoSave setting is changed on the workbook. | Workbook |

| onCalculated | Occurs when a worksheet has finished calculation (or all the worksheets of the collection have finished). | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onChanged | Occurs when the data of individual cells or comments has changed. | CommentCollection, Table, TableCollection, Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onColumnSorted | Occurs when one or more columns have been sorted. This happens as the result of a left-to-right sort operation. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onDataChanged | Occurs when data or formatting within the binding is changed. | Binding |

| onDeactivated | Occurs when an object is deactivated. | Chart, ChartCollection, Shape, Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onDeleted | Occurs when an object is deleted from the collection. | ChartCollection, CommentCollection, TableCollection, WorksheetCollection |

| onFormatChanged | Occurs when the format is changed on a worksheet. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onFormulaChanged | Occurs when a formula is changed. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onProtectionChanged | Occurs when the worksheet protection state is changed. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onRowHiddenChanged | Occurs when the row-hidden state changes on a specific worksheet. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onRowSorted | Occurs when one or more rows have been sorted. This happens as the result of a top-to-bottom sort operation. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onSelectionChanged | Occurs when the active cell or selected range is changed. | Binding, Table, Workbook, Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

| onSettingsChanged | Occurs when the Settings in the document are changed. | SettingCollection |

| onSingleClicked | Occurs when left-clicked/tapped action occurs in the worksheet. | Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

Events in preview

The following events are currently available only in public preview. To use this feature, you must use the preview version of the Office JavaScript API library from the Office.js content delivery network (CDN). The type definition file for TypeScript compilation and IntelliSense is found at the CDN and DefinitelyTyped. You can install these types with npm install —save-dev @types/office-js-preview . For more information on our upcoming APIs, please visit Excel JavaScript API requirement sets.

| Event | Description | Supported objects |

|---|---|---|

| onFiltered | Occurs when a filter is applied to an object. | Table, TableCollection, Worksheet, WorksheetCollection |

Event triggers

Events within an Excel workbook can be triggered by:

- User interaction via the Excel user interface (UI) that changes the workbook

- Office Add-in (JavaScript) code that changes the workbook

- VBA add-in (macro) code that changes the workbook

Any change that complies with default behavior of Excel will trigger the corresponding event(s) in a workbook.

Lifecycle of an event handler

An event handler is created when an add-in registers the event handler. It is destroyed when the add-in unregisters the event handler or when the add-in is refreshed, reloaded, or closed. Event handlers do not persist as part of the Excel file, or across sessions with Excel on the web.

When an object to which events are registered is deleted (e.g., a table with an onChanged event registered), the event handler no longer triggers but remains in memory until the add-in or Excel session refreshes or closes.

With coauthoring, multiple people can work together and edit the same Excel workbook simultaneously. For events that can be triggered by a coauthor, such as onChanged , the corresponding Event object will contain a source property that indicates whether the event was triggered locally by the current user ( event.source = Local ) or was triggered by the remote coauthor ( event.source = Remote ).

Register an event handler

The following code sample registers an event handler for the onChanged event in the worksheet named Sample. The code specifies that when data changes in that worksheet, the handleChange function should run.

Handle an event

As shown in the previous example, when you register an event handler, you indicate the function that should run when the specified event occurs. You can design that function to perform whatever actions your scenario requires. The following code sample shows an event handler function that simply writes information about the event to the console.

Remove an event handler

The following code sample registers an event handler for the onSelectionChanged event in the worksheet named Sample and defines the handleSelectionChange function that will run when the event occurs. It also defines the remove() function that can subsequently be called to remove that event handler. Note that the RequestContext used to create the event handler is needed to remove it.

Enable and disable events

The performance of an add-in may be improved by disabling events. For example, your app might never need to receive events, or it could ignore events while performing batch-edits of multiple entities.

Events are enabled and disabled at the runtime level. The enableEvents property determines if events are fired and their handlers are activated.

The following code sample shows how to toggle events on and off.

Источник

Create application-level event handlers in Excel

Summary

If you want a particular event handler to run whenever a certain event is triggered, you can write an event handler for the Application object. Event handlers for the Application object are global, which means that as long as Microsoft Excel is open, the event handler will run when the appropriate event occurs, regardless of which workbook is active when the event occurs.

This article describes how to create an Application-level event handler and provides an example.

More information

To create an Application-level event handler, you must use the following basic steps:

- Declare a variable for the Application object using the WithEvents keyword. The WithEvents keyword can be used to create an object variable that responds to events triggered by an ActiveX object (such as the Application object).NOTE: WithEvents is valid only in a class module.

- Create the procedure for the specific Application event. For example, you can create a procedure for the WindowResize, WorkbookOpen, or SheetActivate event of the object you declared using WithEvents.

- Create and run a procedure that starts the event handler.

The following example uses these steps to set up a global event handler that displays a message box whenever you resize any workbook window (the event firing the event handler).

Creating and Initiating the Event Handler

Open a new workbook.

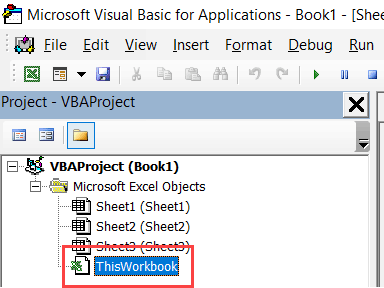

On the Tools menu, point to Macro, and then click Visual Basic Editor.

In Microsoft Office Excel 2007, click Visual Basic in the Code group on the Developer tab.

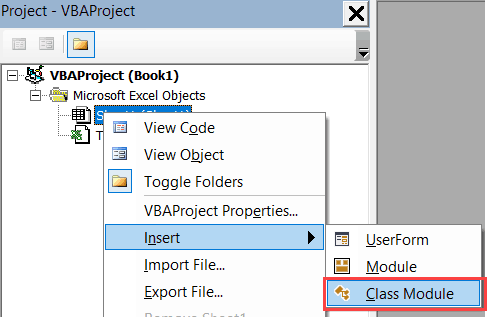

Click Class Module on the Insert menu. This will insert a module titled » — Class1 (Code)» into your project.

Enter the following line of code in the Class1 (Code) module:

The WithEvents keyword makes the appevent variable available in the Object drop-down in the Class1 (Code) module window.

In the Class1 (Code) module window, click the Object drop-down and then click appevent in the list.

In the Class1 (Code) module window, click the Procedure drop-down and then click WindowResize in the list. This will add the following to the Class1 (Code) module sheet:

Add code to the Class1 (Code) module sheet so that it appears as follows:

Next, you have to create an instance of the class and then set the appevent object of the instance of the Class1 to Application. This happens because when you declare a variable, WithEvents, at design time, there is no object associated with it. A WithEvents variable is just like any other object variable — you have to create an object and assign a reference to the object to the WithEvents variable.

On the Insert menu click Module to insert a general type module sheet into your project.

In this module sheet, enter the following code:

Run the test macro.

You have just set the event handler to run each time you resize a workbook window in Microsoft Excel.

On the File menu, click Close and Return to Microsoft Excel.

Resize a workbook window. A message box with «you resized a window» will be displayed.

How to Turn Off the Event Handler

If you close the workbook that contains the above project, the application-level event handler will be turned off. To programmatically turn off the event handler, do the following:

Start the Visual Basic Editor.

In the macro code you entered in Step 9, change the macro to:

Run the test macro again.

On the File menu, click Close and Return to Microsoft Excel.

Источник

Events in the Excel Object Model

Understanding the events in the excel object model is critical because this is often the primary way that your code is run. This chapter examines all the events in the Excel object model, when they are raised, and the type of code you might associate with these events.

Many of the events in the Excel object model are repeated on the Application, Workbook, and Worksheet objects. This repetition allows you to decide whether you want to handle the event for all workbooks, for a particular workbook, or for a particular worksheet. For example, if you want to know when any worksheet in any open workbook is double-clicked, you would handle the Application object’s SheetBeforeDoubleClick event. If you want to know when any worksheet in a particular workbook is double-clicked, you would handle the SheetBeforeDoubleClick event on that Workbook object. If you want to know when one particular sheet is double-clicked, you would handle the BeforeDoubleClick event on that Worksheet object. When an event is repeated on the Application, Workbook, and Worksheet object, it typically is raised first on Worksheet, then Workbook, and finally Application.

New Workbook and Worksheet Events

Excel’s Application object raises a NewWorkbook event when a new blank workbook is created. This event is not raised when a new workbook is created from a template or an existing document. Excel also raises events when new worksheets are created in a particular workbook. Similarly, these events are only raised when a user first creates a new worksheet. They are never raised again on subsequent opens of the workbook.

This discussion now focuses on the various ways in which new workbook and worksheet events are raised:

- Application.NewWorkbook is raised when a new blank workbook is created. Excel passes the new Workbook object as a parameter to this event.

NewWorkbook is the name of both a property and an event on the Application object. Because of this collision, you will not see the NewWorkbook event in Visual Studio’s pop-up menu of properties, events, and methods associated with the Application object. Furthermore, a warning displays at compile time when you try to handle this event. To get Visual Studio’s pop-up menus to work and the warning to go away, you can cast the Application object to the AppEvents_Event interface, as shown in Listing 4-1.

Listing 4-1 shows a console application that handles the Application object’s NewWorkbook and WorkbookNewSheet events. It also creates a new workbook and handles the NewSheet event for that newly created workbook. The console application handles the Close event for the workbook, so when you close the work book the console application will exit and Excel will quit. Listing 4-1 shows several other common techniques. For the sheets passed as object, we use the as operator to cast the object to a Worksheet or a Chart. We then will check the result to verify it is not null to ascertain whether the cast succeeded. This method proves more efficient than using the is operator followed by the as operator, because the latter method requires two casts.

Listing 4-1. A Console Application That Handles New Workbook and Worksheet Events

As you consider the code in Listing 4-1, you might wonder how you will ever remember the syntax of complicated lines of code such as this one:

Fortunately, Visual Studio 2005 helps by generating most of this line of code as well as the corresponding event handler automatically. If you were typing this line of code, after you type +=, Visual Studio displays a pop-up tooltip (see Figure 4-1). If you press the Tab key twice, Visual Studio generates the rest of the line of code and the event handler method automatically.

Figure 4-1. Visual Studio generates event handler code for you if you press the Tab key.

If you are using Visual Studio 2005 Tools for Office (VSTO), you can also use the Properties window to add event handlers to your workbook or worksheet classes. Double-click the project item for your workbook class (typically called ThisWorkbook.cs) or one of your worksheet classes (typically called Sheet1.cs, Sheet2.cs, and so on). Make sure the Properties window is visible. If it is not, choose Properties Window from the View menu to show the Properties window. Make sure that the workbook class (typically called ThisWorkbook) or a worksheet class (typically called Sheet1, Sheet2, and so on) is selected in the combo box at the top of the Properties window. Then click the lightning bolt icon to show events associated with the workbook or worksheet. Type the name of the method you want to use as an event handler in the edit box to the right of the event you want to handle.

Activation and Deactivation Events

Sixteen events in the Excel object model are raised when various objects are activated or deactivated. An object is considered activated when its window receives focus or it is made the selected or active object. For example, worksheets are activated and deactivated when you switch from one worksheet to another within a workbook. Clicking the tab for Sheet3 in a workbook that currently has Sheet1 selected raises a Deactivate event for Sheet1 (it is losing focus) and an Activate event for Sheet3 (it is getting focus). You can activate/deactive chart sheets in the same manner. Doing so raises Activate and Deactivate events on the Chart object corresponding to the chart sheet that was activated or deactivated.

You can also activate/deactivate worksheets. Consider the case where you have the workbooks Book1 and Book2 open at the same time. If you are currently editing Book1 and you switch from Book1 to Book2 by choosing Book2 from the Window menu, the Deactivate event for Book1 is raised and the Activate event for Book2 is raised.

Windows are another example of objects that are activated and deactivated. A workbook can have more than one window open that is showing the workbook. Consider the case where you have the workbook Book1 opened. If you choose New Window from the Window menu, two windows will open in Excel viewing Book1. One window has the caption Book1:1, and the other window has the caption Book1:2. As you switch between Book1:1 and Book1:2, the WindowActivate event is raised for the workbook. Switching between Book1:1 and Book1:2 does not raise the Workbook Activate or Deactivate events because Book1 remains the active workbook.

Note that Activate and Deactivate events are not raised when you switch to an application other than Excel and then switch back to Excel. You might expect that if you had Excel and Word open side by side on your monitor that switching focus by clicking from Excel to Word would raise Deactivate events inside Excel. This is not the caseExcel does not consider switching to another application a deactivation of any of its workbooks, sheets, or windows.

The discussion now turns to the various ways in which Activate and Deactivate events are raised:

- Application.WorkbookActivate is raised whenever a workbook is activated within Excel. Excel passes the Workbook object that was activated as a parameter to this event.

- Workbook.Activate is raised on a particular workbook that is activated. No parameter is passed to this event because the activated workbook is the Workbook object raising the event.

Activate is the name of both a method and an event on the Workbook object. Because of this collision, you will not see the Activate event in Visual Studio’s pop-up menu of properties, events, and methods associated with the Application object. Furthermore, a warning displays at compile time when you try to handle this event.

To get Visual Studio’s pop-up menus to work and to remove the warning, you can cast the Workbook object to the WorkbookEvents_Event interface, as shown in Listing 4-1.

Activate is the name of both a method and an event on the Worksheet and the Chart object. Because of this collision, you will not see the Activate event in Visual Studio’s pop-up menu of properties, events, and methods associated with the Worksheet or Chart object. Furthermore, a warning displays at compile time when you try to handle this event. To get Visual Studio’s pop-up menus to work and the warning to go away, you can cast the Worksheet object to the DocEvents_Event interface and cast the Chart object to the ChartEvents_Events interface, as shown in Listing 4-2.

It is strange that the interface you cast the Worksheet object to is called DocEvents_Event. This is due to the way the PIAs are generatedthe event interface on the COM object Worksheet was called DocEvents rather than WorksheetEvents. The same inconsistency occurs with the Application object; it has an event interface called AppEvents rather than ApplicationEvents.

Listing 4-2 shows a class that handles all of these events. It is passed an Excel Application object to its constructor. The constructor creates a new workbook and gets the first sheet in the workbook. Then it creates a chart sheet. It handles events raised on the Application object as well as the created workbook, the first worksheet in the workbook, and the chart sheet that it adds to the workbook. Because several events pass as a parameter a sheet as an object, a helper method called ReportEvent-WithSheetParameter is used to determine the type of sheet passed and display a message to the console.

Listing 4-2. A Class That Handles Activation and Deactivation Events

Double-Click and Right-Click Events

Several events are raised when a worksheet or a chart sheet is double-clicked or right-clicked (clicked with the right mouse button). Double-click events occur when you double-click in the center of a cell in a worksheet or on a chart sheet. If you double-click the border of the cell, no events are raised. If you double-click column headers or row headers, no events are raised. If you double-click objects in a worksheet (Shape objects in the object model), such as an embedded chart, no events are raised. After you double-click a cell in Excel, Excel enters editing mode for that cella cursor displays in the cell allowing you to type into the cell. If you double-click a cell in editing mode, no events are raised.

The right-click events occur when you right-click a cell in a worksheet or on a chart sheet. A right-click event is also raised when you right-click column headers or row headers. If you right-click objects in a worksheet, such as an embedded chart, no events are raised.

The right-click and double-click events for a chart sheet do not raise events on the Application and Workbook objects. Instead, BeforeDoubleClick and BeforeRightClick events are raised directly on the Chart object.

All the right-click and double-click events have a «Before» in their names. This is because Excel is raising these events before Excel does its default behaviors for double-click and right-clickfor example, displaying a context menu or going into edit mode for the cell you double-clicked. These events all have a bool parameter that is passed by a reference called cancel that allows you to cancel Excel’s default behavior for the double-click or right-click that occurred by setting the cancel parameter to true.

Many of the right-click and double-click events pass a Range object as a parameter. A Range object represents a range of cellsit can represent a single cell or multiple cells. For example, if you select several cells and then right-click the selected cells, a Range object is passed to the right-click event that represents the selected cells.

Double-click and right-click events are raised in various ways, as follows:

- Application.SheetBeforeDoubleClick is raised whenever any cell in any worksheet within Excel is double-clicked. Excel passes as an object the Worksheet that was double-clicked, a Range for the range of cells that was double-clicked, and a bool cancel parameter passed by reference. The cancel parameter can be set to TRue by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing its default double-click behavior. This is a case where it really does not make sense that Worksheet is passed as object because a Chart is never passed. You will always have to cast the object to a Worksheet.

- Workbook.SheetBeforeDoubleClick is raised on a workbook that has a cell in a worksheet that was double-clicked. Excel passes the same parameters as the Application-level SheetBeforeDoubleClick.

- Worksheet.BeforeDoubleClick is raised on a worksheet that is double-clicked. Excel passes a Range for the range of cells that was double-clicked and a bool cancel parameter passed by reference. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing its default double-click behavior.

- Chart.BeforeDoubleClick is raised on a chart sheet that is double-clicked. Excel passes as int an elementID and two parameters called arg1 and arg2. The combination of these three parameters allows you to determine what element of the chart was double-clicked. Excel also passes a bool cancel parameter by reference. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing its default double-click behavior.

- Application.SheetBeforeRightClick is raised whenever any cell in any worksheet within Excel is right-clicked. Excel passes as an object the Worksheet that was right-clicked, a Range for the range of cells that was right-clicked, and a bool cancel parameter passed by reference. The cancel parameter can be set to TRue by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing its default right-click behavior. This is a case where it really does not make sense that Worksheet is passed as an object because a Chart is never passed. You will always have to cast the object to a Worksheet.

- Workbook.SheetBeforeRightClick is raised on a workbook that has a cell in a worksheet that was right-clicked. Excel passes the same parameters as the Application-level SheetBeforeRightClick.

- Worksheet.BeforeRightClick is raised on a worksheet that is right-clicked. Excel passes a Range for the range of cells that was right-clicked and a bool cancel parameter passed by reference. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing its default right-click behavior.

- Chart.BeforeRightClick is raised on a chart sheet that is right-clicked. Strangely enough, Excel does not pass any of the parameters that it passes to the Chart.BeforeDoubleClickEvent. Excel does pass a bool cancel parameter by reference. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing its default right-click behavior.

Listing 4-3 shows a VSTO Workbook class that handles all of these events. This code assumes that you have added a chart sheet to the workbook and it is called Chart1. In VSTO, you do not have to keep a reference to the Workbook object or the Worksheet or Chart objects when handling events raised by these objects because they are already being kept by the project items generated in the VSTO project. You do need to keep a reference to the Application object when handling events raised by the Application object because it is not being kept anywhere in the VSTO project.

The ThisWorkbook class generated by VSTO derives from a class that has all the members of Excel’s Workbook object, so we can add workbook event handlers by adding code that refers to this, as shown in Listing 4-3. We can get an Application object by using this.Application because Application is a property of Workbook. Because the returned application object is not being held as a reference by any other code, we must declare a class member variable to hold on to this Application object so that our events handlers will work. Chapter 1, «An Introduction to Office Programming,» discusses this issue in more detail.

To get to the chart and the worksheet that are in our VSTO project, we use VSTO’s Globals object, which lets us get to the classes Chart1 and Sheet1 that are declared in other project items. We do not have to hold these objects in a class member variable because they have lifetimes that match the lifetime of the VSTO code behind.

We also declare two helper functions in Listing 4-3. One casts the sheet that is passed as an object to a Worksheet and returns the name of the worksheet. The other gets the address of the Range that is passed to many of the events as the target parameter.

The handlers for the right-click events all set the bool cancel parameter that is passed by reference to true. This will make it so that Excel will not do its default behavior on right-click, which is typically to pop up a menu.

Listing 4-3. A VSTO Workbook Customization That Handles Double-Click and Right-Click Events

/// Required method for Designer support — do not modify /// the contents of this method with the code editor. ///

Cancelable Events and Event Bubbling

Listing 4-3 raises an interesting question. What happens when multiple objects handle an event such as BeforeRightClick at multiple levels? Listing 4-3 handles the BeforeRightClick event at the Worksheet, Workbook, and Application level. Excel first raises the event at the Worksheet level for all code that has registered for the Worksheet-level event. Remember that other add-ins could be loaded in Excel handling Worksheet-level events as well. Your code might get the Worksheet.BeforeRightClick event first followed by some other add-in that also is handling the Worksheet.BeforeRightClick event. When multiple add-ins handle the same event on the same object, you cannot rely on any determinate order for who will get the event first. Therefore, do not write your code to rely on any particular ordering.

After events are raised at the Worksheet level, they are then raised at the Workbook level, and finally at the Application level. For a cancelable event, even if one event handler sets the cancel parameter to true, the events will continue to be raised to other event handlers. So even though the code in Listing 4-3 sets the cancel parameter to true in Sheet1_BeforeRightClick, Excel will continue to raise events on other handlers of the worksheet BeforeRightClick and then handlers of the Workbook.SheetBeforeRightClick followed by handlers of the Application.SheetBeforeRightClick.

Another thing you should know about cancelable events is that you can check the incoming cancel parameter in your event handler to see what the last event handler set it to. So in the Sheet1_BeforeRightClick handler, the incoming cancel parameter would be false assuming no other code is handling the event. In the ThisWorkbook_SheetBeforeRightClick handler, the incoming cancel parameter would be true because the last handler, Sheet1_BeforeRightClick, set it to TRue. This means that as an event bubbles through multiple handlers, each subsequent handler can override what the previous handlers did with respect to canceling the default right-click behavior in this example. Application-level handlers get the final sayalthough if multiple Application-level handlers exist for the same event, whether the event gets cancelled or not is indeterminate because no rules dictate which of multiple Application-level event handlers get an event first or last.

Four events are raised when formulas in the worksheet are recalculated. The worksheet is recalculated whenever you change a cell that affects a formula referring to that cell or when you add or modify a formula:

- Application.SheetCalculate is raised whenever any sheet within Excel is recalculated. Excel passes the sheet as an object that was recalculated as a parameter to this event. The sheet object can be cast to a Worksheet or a Chart.

- Workbook.SheetCalculate is raised on a workbook that has a sheet that was recalculated. Excel passes the sheet as an object that was recalculated as a parameter to this event. The sheet object can be cast to a Worksheet or a Chart.

- Worksheet.Calculate is raised on a worksheet that was recalculated.

Calculate is the name of both a method and an event on the Worksheet object. Because of this collision, you will not see the Calculate event in Visual Studio’s pop-up menu of properties, events, and methods associated with the Worksheet object. Furthermore, a warning displays at compile time when you try to handle this event. To get Visual Studio’s pop-up menus to work and the warning to go away, you can cast the Worksheet object to the DocEvents_Event interface, as shown in Listing 4-4.

Listing 4-4 shows a console application that handles all the calculation events. The console application creates a new workbook, gets the first worksheet in the workbook, and creates a chart in the workbook. The console application also handles the Close event for the created workbook to cause the console application to exit when the workbook is closed. To get Excel to raise worksheet and workbook Calculate events, add some values and formulas to the first worksheet in the workbook. To raise the Chart object’s Calculate event, you can right-click the chart sheet that you are handling the event for and choose Source Data from the pop-up menu. Then, click the button to the right of the Data Range text box, switch to the first worksheet, and select a range of values for the chart sheet to display. When you change those values and switch back to the chart sheet, the Chart’s Calculate event will be raised.

Listing 4-4. A Console Application That Handles Calculate Events

Excel raises several events when a cell or range of cells is changed in a worksheet. The cells must be changed by a user editing the cell for change events to be raised. Change events can also be raised when a cell is linked to external data and is changed as a result of refreshing the cell from the external data. Change events are not raised when a cell is changed because of a recalculation. They are not raised when the user changes formatting of the cell without changing the value of the cell. When a user is editing a cell and is in cell edit mode, the change events are not raised until the user exits cell edit mode by leaving that cell or pressing the Enter key:

- Application.SheetChange is raised when a cell or range of cells in any workbook is changed by the user or updated from external data. Excel passes the sheet as an object where the change occurred as a parameter to this event. You can always cast the sheet parameter to a Worksheet because the Change event is not raised for chart sheets. Excel also passes a Range as a parameter for the range of cells that was changed.

- Workbook.SheetChange is raised on a workbook when a cell or range of cells in that workbook is changed by the user or updated from external data. Excel passes the sheet as an object where the change occurred as a parameter to this event. You can always cast the sheet parameter to a Worksheet because the Change event is not raised for chart sheets. Excel also passes a Range as a parameter for the range of cells that was changed.

- Worksheet.Change is raised on a worksheet when a cell or range of cells in that worksheet is changed by the user or updated from external data. Excel passes a Range as a parameter for the range of cells that was changed.

Listing 4-5 shows a class that handles all the Change events. It is passed an Excel Application object to its constructor. The constructor creates a new workbook and gets the first worksheet in the workbook. It handles events raised on the Application object, the workbook, and the first worksheet in the workbook.

Listing 4-5. A Class That Handles Change Events

Follow Hyperlink Events

Excel raises several events when a hyperlink in a cell is clicked. You might think this event is not very interesting, but you can use it as a simple way to invoke an action in your customization. The trick is to create a hyperlink that does nothing, and then handle the FollowHyperlink event and execute your action in that event handler.

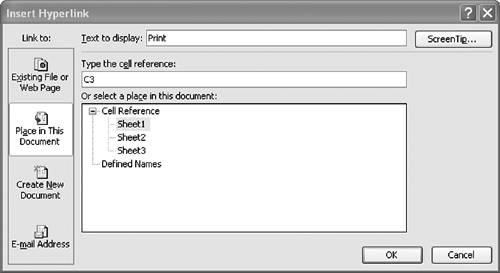

To create a hyperlink that does nothing, right-click the cell where you want to put your hyperlink and choose HyperLink. For our example, we select cell C3. In the dialog that appears, click the Place in This Document button to the left of the dialog (see Figure 4-2). In the Type the cell reference text box, type C3 or the reference of the cell to which you are adding a hyperlink. The logic behind doing this is that Excel will select the cell that C3 is linked to after the hyperlink is clicked and after your event handler runs. If you select a cell other than the cell the user clicked, the selection will move, which is confusing. So we effectively link the cell to itself, creating a do nothing link. In the Text to display text box, type the name of your commandthe name you want displayed in the cell. In this example, we name the command Print.

Figure 4-2. The Insert Hyperlink dialog.

The following events are raised when a hyperlink is clicked:

- Application.SheetFollowHyperlink is raised when a hyperlink is clicked in any workbook open in Excel. Excel passes a Hyperlink object as a parameter to this event. The Hyperlink object gives you information about the hyperlink that was clicked.

- Workbook.SheetFollowHyperlink is raised on a workbook when a hyperlink is clicked in that workbook. Excel passes a Hyperlink object as a parameter to this event. The Hyperlink object gives you information about the hyperlink that was clicked.

- Worksheet.FollowHyperlink is raised on a worksheet when a hyperlink is clicked in that worksheet. Excel passes a Hyperlink object as a parameter to this event. The Hyperlink object gives you information about the hyperlink that was clicked.

Listing 4-6 shows a VSTO customization class for the workbook project item. This class assumes a workbook that has a Print hyperlink in it, created as shown in Figure 4-2. The customization does nothing in the handlers of the Application or Workbook-level hyperlink events but log to the console window. The Worksheet-level handler detects that a hyperlink named Print was clicked and invokes the PrintOut method on the Workbook object to print the workbook.

Listing 4-6. A VSTO Workbook Customization That Handles Hyperlink Events

/// Required method for Designer support — do not modify /// the contents of this method with the code editor. ///

Selection Change Events

Selection change events occur when the selected cell or cells change, or in the case of the Chart.Select event, when the selected chart element within a chart sheet changes:

- Application.SheetSelectionChange is raised whenever the selected cell or cells in any worksheet within Excel change. Excel passes the sheet upon which the selection changed to the event handler. However, the event handler’s parameter is typed as object, so it must be cast to a Worksheet if you want to use the properties or methods of the Worksheet. You are guaranteed to always be able to cast the argument to Worksheet because the SheetSelectionChange event is not raised when selection changes on a Chart. Excel also passes the range of cells that is the new selection.

- Workbook.SheetSelectionChange is raised on a Workbook whenever the selected cell or cells in that workbook change. Excel passes as an object the sheet where the selection changed. You can always cast the sheet object to a Worksheet because this event is not raised for selection changes on a chart sheet. Excel also passes a Range for the range of cells that is the new selection.

- Worksheet.SelectionChange is raised on a Worksheet whenever the selected cell or cells in that worksheet change. Excel passes a Range for the range of cells that is the new selection.

- Chart.Select is raised on a Chart when the selected element within that chart sheet changes. Excel passes as int an elementID and two parameters called arg1 and arg2. The combination of these three parameters allows you to determine what element of the chart was selected.

Select is the name of both a method and an event on the Chart object. Because of this collision, you will not see the Select event in Visual Studio’s pop-up menu of properties, events, and methods associated with the Chart object. Furthermore, a warning displays at compile time when you try to handle this event. To get Visual Studio’s pop-up menus to work and the warning to go away, you can cast the Chart object to the ChartEvents_Events interface, as shown in Listing 4-2.

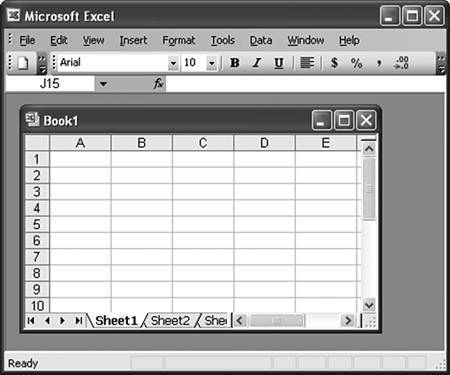

The WindowResize events are raised when a workbook window is resized. These events are only raised if the workbook window is not maximized to fill Excel’s outer application window (see Figure 4-3). Events are raised if you resize a nonmaximized workbook window or minimize the workbook window. No resize events occur when you resize and minimize the outer Excel application window.

- Application.WindowResize is raised when any nonmaximized workbook window is resized or minimized. Excel passes the Window object corresponding to the window that was resized or minimized as a parameter to this event. Excel also passes the Workbook object that was affected as a parameter to this event.

- Workbook.WindowResize is raised on a Workbook when a nonmaximized window associated with that workbook is resized or minimized. Excel passes the Window that was resized or minimized as a parameter to this event.

Figure 4-3. Window Resize events are only raised if the workbook window is not maximized to fill the application window.

Add-In Install and Uninstall Events

A workbook can be saved into a special add-in format (XLA file) by selecting Save As from the File menu and then picking Microsoft Office Excel Add-in as the desired format. The workbook will then be saved to the Application DataMicrosoftAddIns directory found under the user’s document and settings directory. It will appear in the list of available add-ins that displays when you choose Add-Ins from the Tools menu. When you click the check box to enable the add-in, the workbook loads in a hidden state, and the Application.AddinInstall event is raised. When the user clicks the check box to disable the add-in, the Application.AddinUninstall event is raised.

Although you can theoretically save a workbook customized by VSTO as an XLA file, Microsoft does not support this scenario, because many VSTO features such as support for the Document Actions task pane and Smart Tags do not work when a workbook is saved as an XLA file.

XML Import and Export Events

Excel supports the import and export of custom XML data files by allowing you to take an XML schema and map it to cells in a workbook. It is then possible to export or import those cells to an XML data file that conforms to the mapped schema. Excel raises events on the Application and Workbook object before and after an XML file is imported or exported, allowing the developer to further customize and control this feature. Chapter 21, «Working with XML in Excel,» discusses in detail the XML mapping features of Excel.

Before Close Events

Excel raises events before a workbook is closed. These events are to give your code a chance to prevent the closing of the workbook. Excel passes a bool cancel parameter to the event. If your event handler sets the cancel parameter to true, the pending close of the workbook is cancelled and the workbook remains open.

These events cannot be used to determine whether the workbook is actually going to close. Another event handler might run after your event handlerfor example, an event handler in another add-inand that event handler might set the cancel parameter to true preventing the close of the workbook. Furthermore, if the user has changed the workbook and is prompted to save changes when the workbook is closed, the user can click the Cancel button, causing the workbook to remain open.

If you need to run code only when the workbook is actually going to close, VSTO provides a Shutdown event that is not raised until all other event handlers and the user has allowed the close of the workbook.

- Application.WorkbookBeforeClose is raised before any workbook is closed, giving the event handler the chance to prevent the closing of the workbook. Excel passes the Workbook object that is about to be closed. Excel also passes by reference a bool cancel parameter. The cancel parameter can be set to TRue by your event handler to prevent Excel from closing the workbook.

- Workbook.BeforeClose is raised on a workbook that is about to be closed, giving the event handler the chance to prevent the closing of the workbook. Excel passes by reference a bool cancel parameter. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from closing the workbook.

Before Print Events

Excel raises events before a workbook is printed. These events are raised when the user chooses Print or Print Preview from the File menu or presses the print toolbar button. Excel passes a bool cancel parameter to the event. If your event handler sets the cancel parameter to true, the pending print of the workbook will be cancelled and the print dialog or print preview view will not be shown. You might want to do this because you want to replace Excel’s default printing behavior with some custom printing behavior of your own.

These events cannot be used to determine whether the workbook is actually going to be printed. Another event handler might run after your event handler and prevent the printing of the workbook. The user can also press the Cancel button in the Print dialog to stop the printing from occurring.

- Application.WorkbookBeforePrint is raised before any workbook is printed or print previewed, giving the event handler a chance to change the workbook before it is printed or change the default print behavior. Excel passes as a parameter the Workbook that is about to be printed. Excel also passes by reference a bool cancel parameter. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from performing its default print behavior.

- Workbook.BeforePrint is raised on a workbook that is about to be printed or print previewed, giving the event handler a chance to change the workbook before it is printed or change the default print behavior. Excel passes by reference a bool cancel parameter. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent performing its default print behavior.

Before Save Events

Excel raises cancelable events before a workbook is saved, allowing you to perform some custom action before the document is saved. These events are raised when the user chooses Save, Save As, or Save As Web Page commands. They are also raised when the user closes a workbook that has been modified and chooses to save when prompted. Excel passes a bool cancel parameter to the event. If your event handler sets the cancel parameter to true, the save will be cancelled and the save dialog will not be shown. You might want to do this because you want to replace Excel’s default saving behavior with some custom saving behavior of your own.

These events cannot be used to determine whether the workbook is actually going to be saved. Another event handler might run after your event handler and prevent the save of the workbook. The user can also press Cancel in the Save dialog to stop the save of the workbook.

- Application.WorkbookBeforeSave is raised before any workbook is saved, giving the event handler a chance to prevent or override the saving of the workbook. Excel passes as a parameter the Workbook that is about to be saved. Excel also passes a bool saveAsUI parameter that tells the event handler whether Save or Save As was selected. Excel also passes by reference a bool cancel parameter. The cancel parameter can be set to TRue by your event handler to prevent Excel from performing its default save behavior.

- Workbook.BeforeSave is raised on a workbook that is about to be saved, giving the event handler a chance to prevent or override the saving of the workbook. Excel passes a bool saveAsUI parameter that tells the event handler whether Save or Save As was selected. Excel passes by reference a bool cancel parameter. The cancel parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from performing its default save behavior.

Excel raises events when a workbook is opened or when a new workbook is created from a template or an existing document. If a new blank workbook is created, the Application.WorkbookNew event is raised.

- Application.WorkbookOpen is raised when any workbook is opened. Excel passes the Workbook that is opened as a parameter to this event. This event is not raised when a new blank workbook is created. The Application.WorkbookNew event is raised instead.

- Workbook.Open is raised on a workbook when it is opened.

Listing 4-7 shows a console application that handles the BeforeClose, BeforePrint, BeforeSave, and Open events. It sets the cancel parameter to TRue in the BeforeSave and BeforePrint handlers to prevent the saving and printing of the workbook.

Listing 4-7. A Console Application That Handles Close, Print, Save, and Open Events

Toolbar and Menu Events

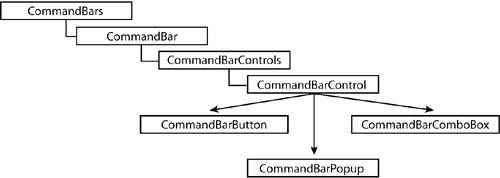

A common way to run your code is by adding a custom toolbar button or menu item to Excel and handling the click event raised by that button or menu item. Both a toolbar and a menu bar are represented by the same object in the Office object model, an object called CommandBar. Figure 4-4 shows the hierarchy of CommandBar-related objects. The Application object has a collection of CommandBars that represent the main menu bar and all the available toolbars in Excel. You can see all the available toolbars in Excel by choosing Customize from the Tools menu.

Figure 4-4. The hierarchy of CommandBar objects.

The CommandBar objects are made available to your application by adding a reference to the Microsoft Office 11.0 Object Library PIA (office.dll). The CommandBar objects are found in the Microsoft.Office.Core namespace.

A CommandBar has a collection of CommandBarControls that contains objects of type CommandBarControl. A CommandBarControl can often be cast to a CommandBarButton, CommandBarPopup, or CommandBarComboBox. It is also possible to have a CommandBarControl that cannot be cast to one of these other typesfor example, it is just a CommandBarControl and cannot be cast to a CommandBarButton, CommandBarPopup, or CommandBarComboxBox.

Listing 4-8 shows some code that iterates over all of the CommandBars available in Excel. The code displays the name or caption of each CommandBar and associated CommandBarControls. When Listing 4-8 gets to a CommandBarControl, it first checks whether it is a CommandBarButton, a CommandBarComboBox, or a CommandBarPopup, and then casts to the corresponding object. If it is not any of these object types, the code uses the CommandBarControl properties. Note that a CommandBarPopup has a Controls property that returns a CommandBarControls collection. Our code uses recursion to iterate the CommandBarControls collection associated with a CommandBarPopup control.

Listing 4-8. A Console Application That Iterates Over All the CommandBars and CommandBarControls in Excel

Excel raises several events on CommandBar, CommandBarButton, and CommandBarComboBox objects:

- CommandBar.OnUpdate is raised when any change occurs to a CommandBar or associated CommandBarControls. This event is raised frequently and can even raise when selection changes in Excel. Handling this event could slow down Excel, so you should handle this event with caution.

- CommandBarButton.Click is raised on a CommandBarButton that is clicked. Excel passes the CommandBarButton that was clicked as a parameter to this event. It also passes by reference a bool cancelDefault parameter. The cancelDefault parameter can be set to true by your event handler to prevent Excel from executing the default action associated with the button. For example, you could handle this event for an existing button such as the Print button. By setting cancelDefault to TRue, you can prevent Excel from doing its default print behavior when the user clicks the button and instead replace that behavior with your own.

- CommandBarComboBox.Change is raised on a CommandBarComboBox that had its text value changedeither because the user chose an option from the drop-down or because the user typed a new value directly into the combo box. Excel passes the CommandBarComboBox that changed as a parameter to this event.

Listing 4-9 shows a console application that creates a CommandBar, a CommandBarButton, and a CommandBarComboBox. It handles the CommandBarButton.Click event to exit the application. It also displays changes made to the CommandBarComboBox in the console window. The CommandBar, CommandBarButton, and CommandBarComboBox are added temporarily; Excel will delete them automatically when the application exits. This is done by passing true to the last parameter of the CommandBarControls.Add method.

Listing 4-9. A Console Application That Adds a CommandBar and a CommandBarButton

Several other less commonly used events in the Excel object model are listed in table 4-1. Figure 4-17 shows the envelope UI that is referred to in this table.

Table 4-1. Additional Excel Events

Application.SheetPivotTableUpdate Workbook.SheetPivotTableUpdate Worksheet.PivotTableUpdate

Raised when a sheet of a Pivot Table report has been updated.

Application.WorkbookPivotTable CloseConnection Workbook.PivotTableCloseConnection

Raised when a PivotTable report connection is closed.

Application.WorkbookPivotTable OpenConnection Workbook.PivotTableOpenConnection

Raised when a PivotTable report connection is opened.

Raised when a workbook that is part of a document workspace is synchronized with the server.

Raised when a range of cells is dragged over a chart.

Raised when a range of cells is dragged and dropped on a chart.

Raised when the user clicks the mouse button while the cursor is over a chart.

Raised when the user moves the mouse cursor within the bounds of a chart.

Raised when the user releases the mouse button while the cursor is over a chart.

Raised when the chart is resized.

Raised when the user changes the data being displayed by the chart.

Raised when the envelope UI is shown inside Excel (see Figure 4-5).

Raised when the envelope UI is hidden (see Figure 4-5).

Raised when an OLEObjectan embedded ActiveX control or OLE objectgets the focus.

Raised when an OLEObjectan embedded ActiveX control or OLE objectloses focus.

Raised after a QueryTable is refreshed.

Raised before a QueryTable is refreshed.

Figure 4-5. The envelope UI inside of Excel.

Источник

Adblock

detector

When you create or record a macro in Excel, you need to run the macro to execute the steps in the code.

A few ways of running a macro includes using the macro dialog box, assigning the macro to a button, using a shortcut, etc.

Apart from these user-initiated macro executions, you can also use VBA events to run the macro.

Excel VBA Events – Introduction

Let me first explain what is an event in VBA.

An event is an action that can trigger the execution of the specified macro.

For example, when you open a new workbook, it’s an event. When you insert a new worksheet, it’s an event. When you double-click on a cell, it’s an event.

There are many such events in VBA, and you can create codes for these events. This means that as soon as an event occurs, and if you have specified a code for that event, that code would instantly be executed.

Excel automatically does this as soon as it notices that an event has taken place. So you only need to write the code and place it in the correct event subroutine (this is covered later in this article).

For example, if you insert a new worksheet and you want it to have a year prefix, you can write the code for it.

Now, whenever anyone inserts a new worksheet, this code would automatically be executed and add the year prefix to the worksheet’s name.

Another example could be that you want to change the color of the cell when someone double-clicks on it. You can use the double-click event for this.

Similarly, you can create VBA codes for many such events (as we will see later in this article).

Below is a short visual that shows the double-click event in action. As soon as I double click on cell A1. Excel instantly opens a message box that shows the address of the cell.

Double-click is an event, and showing the message box is what I have specified in the code whenever the double-click event takes place.

While the above example is a useless event, I hope it helps you understand what events really are.

Different Types of Excel VBA Events

There are different objects in Excel – such as Excel itself (to which we often refer to as the application), workbooks, worksheets, charts, etc.

Each of these objects can have various events associated with it. For example:

- If you create a new workbook, it’s an application level event.

- If you add a new worksheet, it’s a workbook level event.

- If you change the value in a cell in a sheet, it’s a worksheet level event.

Below are the different types of Events that exist in Excel:

- Worksheet Level Events: These are the types of events that would trigger based on the actions taken in the worksheet. Examples of these events include changing a cell in the worksheet, changing the selection, double-clicking on a cell, right-clicking on a cell, etc.

- Workbook Level Events: These events would be triggered based on the actions at the workbook level. Examples of these events include adding a new worksheet, saving the workbook, opening the workbook, printing a part or the entire workbook, etc.

- Application Level Events: These are the events that occur in the Excel application. Example of these would include closing any of the open workbooks or opening a new workbook.

- UserForm Level Events: These events would be triggered based on the actions in the ‘UserForm’. Examples of these include initializing a UserForm or clicking a button in the UserForm.

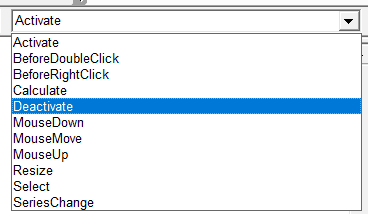

- Chart Events: These are events related to the chart sheet. A chart sheet is different than a worksheet (which is where most of us are used to work in Excel). A chart sheets purpose is to hold a chart. Examples of such events would include changing the series of the chart or resizing the chart.

- OnTime and OnKey Events: These are two events that don’t fit in any of the above categories. So I have listed these separately. ‘OnTime’ event allows you to execute a code at a specific time or after a specific time has elapsed. ‘OnKey’ event allows you to execute a code when a specific keystroke (or a combination of keystrokes) is used.

Where to Put the Event-Related Code

In the above section, I covered the different types of events.

Based on the type of event, you need to put the code in the relevant object.

For example, if it’s a worksheet related event, it should go in the code window of the worksheet object. If it’s workbook related, it should go in the code window for a workbook object.

In VBA, different objects – such as Worksheets, Workbooks, Chart Sheets, UserForms, etc., have their own code windows. You need to put the event code in the relevant object’s code window. For example – if it’s a workbook level event, then you need to have the event code in the Workbook code window.

The following sections cover the places where you can put the event code:

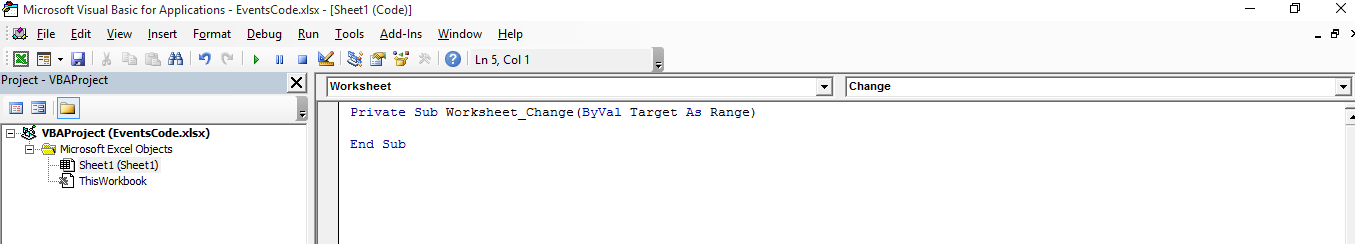

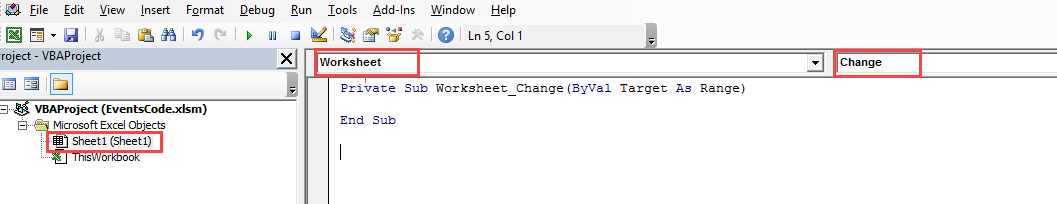

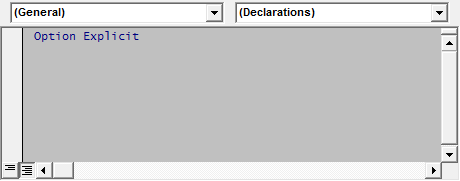

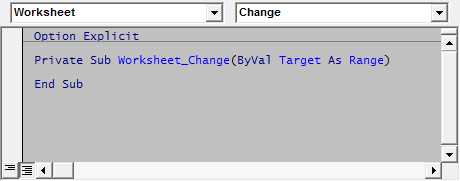

In Worksheet Code Window

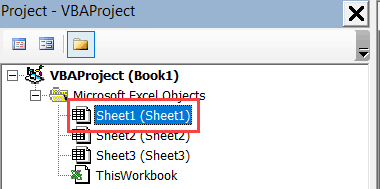

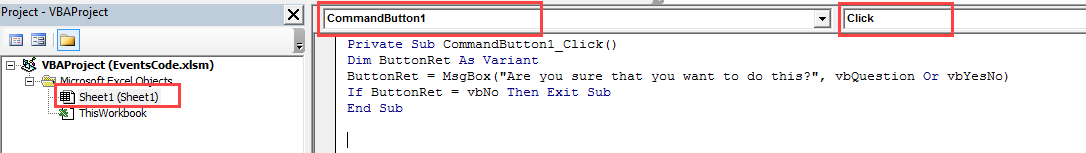

When you open the VB Editor (using keyboard shortcut ALT + F11), you would notice the worksheets object in the Project Explorer. For each worksheet in the workbook, you will see one object.

When you double-click on the worksheet object in which you want to place the code, it would open the code window for that worksheet.

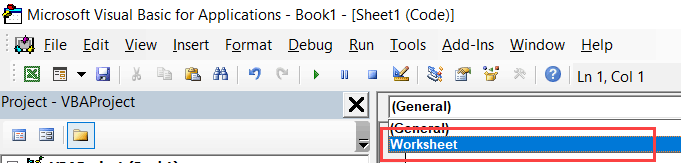

While you can start writing the code from scratch, it’s much better to select the event from a list of options and let VBA automatically insert the relevant code for the selected event.

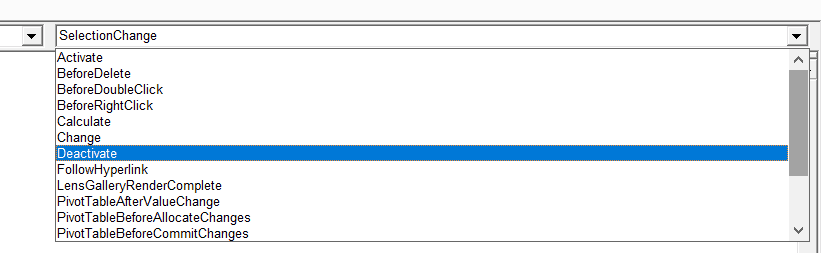

To do this, you need to first select worksheet from the drop down at the top-left of the code window.

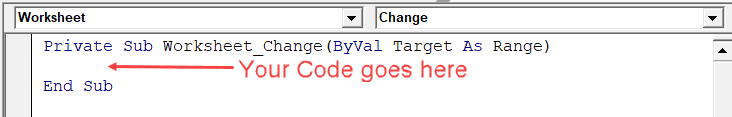

After selecting worksheet from the drop down, you get a list of all the events related to the worksheet. You can select the one you want to use from the drop-down at the top right of the code window.

As soon as you select the event, it would automatically enter the first and last line of the code for the selected event. Now you can add your code in between the two lines.

Note: As soon as you select Worksheet from the drop-down, you would notice two lines of code appear in the code window. Once you have selected the event for which you want the code, you can delete the lines that appeared by default.

Note that each worksheet has a code window of its own. When you put the code for Sheet1, it will only work if the event happens in Sheet1.

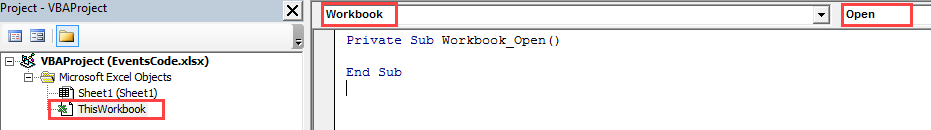

In ThisWorkbook Code Window

Just like worksheets, if you have a workbook level event code, you can place it in ThisWorkbook code window.

When you double-click on ThisWorkbook, it will open the code window for it.

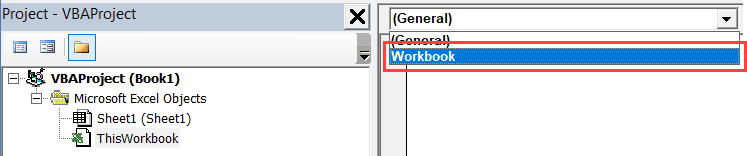

You need to select Workbook from the drop-down at the top-left of the code window.

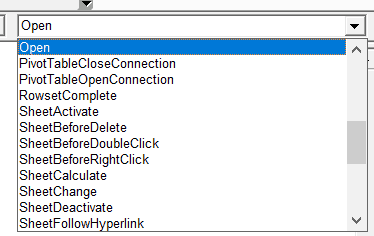

After selecting Workbook from the drop down, you get a list of all the events related to the Workbook. You can select the one you want to use from the drop-down at the top right of the code window.

As soon as you select the event, it would automatically enter the first and last line of the code for the selected event. Now you can add your code in between the two lines.

Note: As soon as you select Workbook from the drop-down, you would notice two lines of code appear in the code window. Once you have selected the event for which you want the code, you can delete the lines that appeared by default.

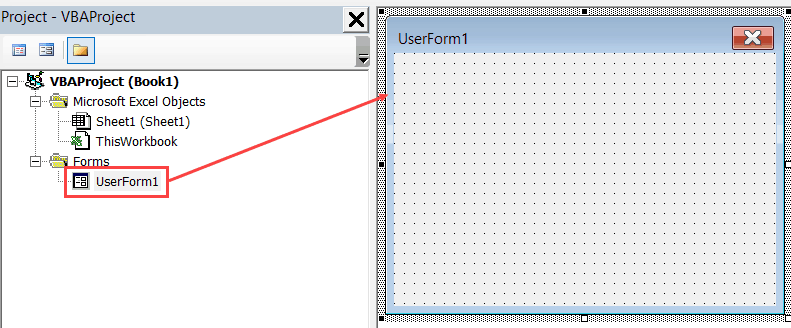

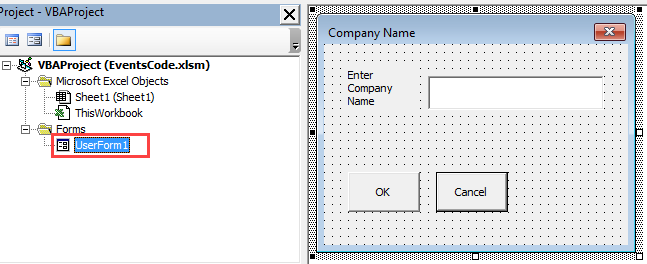

In Userform Code Window

When you’re creating UserForms in Excel, you can also use UserForm events to executes codes based on specific actions. For example, you can specify a code that is executed when the button is clicked.

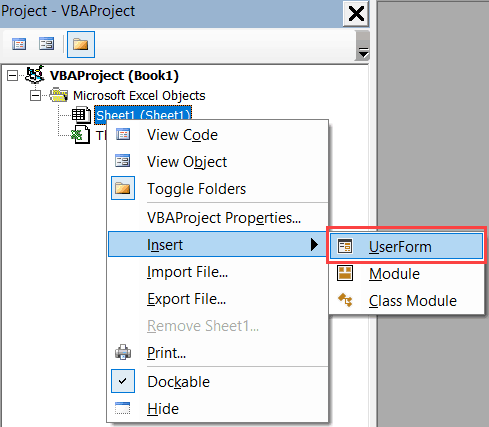

While the Sheet objects and ThisWorkbook objects are already available when you open the VB Editor, UserForm is something you need to create first.

To create a UserForm, right-click on any of the objects, go to Insert and click on UserForm.

This would insert a UserForm object in the workbook.

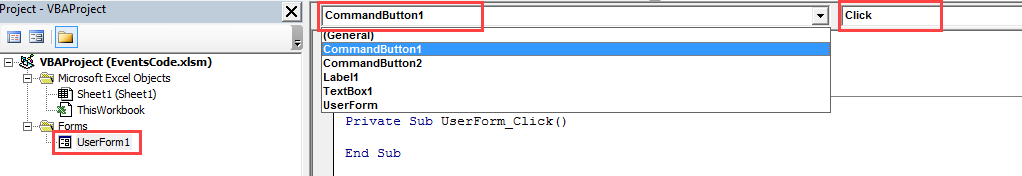

When you double-click on the UserForm (or any of the object that you add to the UserForm), it would open the code window for the UserForm.

Now just like worksheets or ThisWorkbook, you can select the event and it will insert the first and the last line for that event. And then you can add the code in the middle of it.

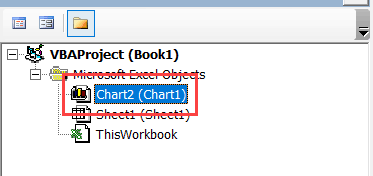

In Chart Code Window

In Excel, you can also insert Chart sheets (which are different then worksheets). A chart sheet is meant to contain charts only.

When you have inserted a chart sheet, you will be able to see the Chart sheet object in the VB Editor.

You can add the event code to the chart sheet code window just like we did in the worksheet.

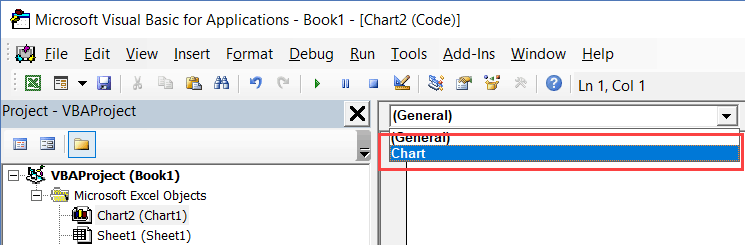

Double click on the Chart sheet object in the Project Explorer. This will open the code window for the chart sheet.

Now, you need to select Chart from the drop-down at the top-left of the code window.

After selecting Chart from the drop-down, you get a list of all the events related to the Chart sheet. You can select the one you want to use from the drop-down at the top right of the code window.

Note: As soon as you select Chart from the drop-down, you would notice two lines of code appear in the code window. Once you have selected the event for which you want the code, you can delete the lines that appeared by default.

In Class Module

Class Modules need to be inserted just like UserForms.

A class module can hold code related to the application – which would be Excel itself, and the embedded charts.

I will cover the class module as a separate tutorial in the coming weeks.

Note that apart from OnTime and OnKey events, none of the above events can be stored in the regular VBA module.

Understanding the Event Sequence

When you trigger an event, it doesn’t happen in isolation. It may also lead to a sequence of multiple triggers.

For example, when you insert a new worksheet, the following things happen:

- A new worksheet is added

- The previous worksheet gets deactivated

- The new worksheet gets activated

While in most cases, you may not need to worry about the sequence, if you’re creating complex codes that rely on events, it’s better to know the sequence to avoid unexpected results.

Understanding the Role of Arguments in VBA Events

Before we jump to Event examples and the awesome things you can do with it, there is one important concept I need to cover.

In VBA events, there would be two types of codes:

- Without any arguments

- With arguments

And in this section, I want to quickly cover the role of arguments.

Below is a code that has no argument in it (the parenthesis are empty):

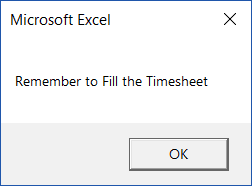

Private Sub Workbook_Open() MsgBox "Remember to Fill the Timesheet" End Sub

With the above code, when you open a workbook, it simply shows a message box with the message – “Remember to fill the Timesheet”.

Now let’s have a look at a code that has an argument.

Private Sub Workbook_NewSheet(ByVal Sh As Object)

Sh.Range("A1") = Sh.Name

End Sub

The above code uses the Sh argument which is defined as an object type. The Sh argument could be a worksheet or a chart sheet, as the above event is triggered when a new sheet is added.

By assigning the new sheet that is added to the workbook to the object variable Sh, VBA has enabled us to use it in the code. So to refer to the new sheet name, I can use Sh.Name.

The concept of arguments will be useful when you go through the VBA events examples in the next sections.

Workbook Level Events (Explained with Examples)

Following are the most commonly used events in a workbook.

| EVENT NAME | WHAT TRIGGERS THE EVENT |

| Activate | When a workbook is activated |

| AfterSave | When a workbook is installed as an add-in |

| BeforeSave | When a workbook is saved |

| BeforeClose | When a workbook is closed |

| BeforePrint | When a workbook is printed |

| Deactivate | When a workbook is deactivated |

| NewSheet | When a new sheet is added |

| Open | When a workbook is opened |

| SheetActivate | When any sheet in the workbook is activated |

| SheetBeforeDelete | When any sheet is deleted |

| SheetBeforeDoubleClick | When any sheet is double-clicked |

| SheetBeforeRightClick | When any sheet is right-clicked |

| SheetCalculate | When any sheet is calculated or recalculated |

| SheetDeactivate | When a workbook is deactivated |

| SheetPivotTableUpdate | When a workbook is updated |

| SheetSelectionChange | When a workbook is changed |

| WindowActivate | When a workbook is activated |

| WindowDeactivate | When a workbook is deactivated |

Note that this is not a complete list. You can find the complete list here.

Remember that the code for Workbook event is stored in the ThisWorkbook objects code window.

Now let’s have a look at some useful workbook events and see how these can be used in your day-to-day work.

Workbook Open Event

Let’s say that you want to show the user a friendly reminder to fill their timesheets whenever they open a specific workbook.

You can use the below code to do this:

Private Sub Workbook_Open() MsgBox "Remember to Fill the Timesheet" End Sub

Now as soon as you open the workbook that has this code, it will show you a message box with the specified message.

There are a few things to know when working with this code (or Workbook Event codes in general):

- If a workbook has a macro and you want to save it, you need to save it in the .XLSM format. Else the macro code would be lost.

- In the above example, the event code would be executed only when the macros are enabled. You may see a yellow bar asking for permission to enable macros. Until that is enabled, the event code is not executed.

- The Workbook event code is placed in the code window of ThisWorkbook object.

You can further refine this code and show the message only of Friday.

The below code would do this:

Private Sub Workbook_Open() wkday = Weekday(Date) If wkday = 6 Then MsgBox "Remember to Fill the Timesheet" End Sub

Note that in the Weekday function, Sunday is assigned the value 1, Monday is 2 and so on.

Hence for Friday, I have used 6.

Workbook Open event can be useful in many situations, such as:

- When you want to show a welcome message to the person when a workbook is opened.

- When you want to display a reminder when the workbook is opened.

- When you want to always activate one specific worksheet in the workbook when it’s opened.

- When you want to open related files along with the workbook.

- When you want to capture the date and time stamp every time the workbook is opened.

Workbook NewSheet Event

NewSheet event is triggered when you insert a new sheet in the workbook.

Let’s say that you want to enter the date and time value in cell A1 of the newly inserted sheet. You can use the below code to do this:

Private Sub Workbook_NewSheet(ByVal Sh As Object)

On Error Resume Next

Sh.Range("A1") = Format(Now, "dd-mmm-yyyy hh:mm:ss")

End Sub

The above code uses ‘On Error Resume Next’ to handle cases where someone inserts a chart sheet and not a worksheet. Since chart sheet doesn’t have cell A1, it would show an error if ‘On Error Resume Next’ is not used.

Another example could be when you want to apply some basic setting or formatting to a new sheet as soon as it is added. For example, if you want to add a new sheet and want it to automatically get a serial number (up to 100), then you can use the code below.

Private Sub Workbook_NewSheet(ByVal Sh As Object)

On Error Resume Next

With Sh.Range("A1")

.Value = "S. No."

.Interior.Color = vbBlue

.Font.Color = vbWhite

End With

For i = 1 To 100

Sh.Range("A1").Offset(i, 0).Value = i

Next i

Sh.Range("A1", Range("A1").End(xlDown)).Borders.LineStyle = xlContinuous

End Sub

The above code also does a bit of formatting. It gives the header cell a blue color and makes the font white. It also applies a border to all the filled cells.

The above code is an example of how a short VBA code can help you steal a few seconds every time you insert a new worksheet (in case this is something that you have to do every time).

Workbook BeforeSave Event

Before Save event is triggered when you save a workbook. Note that the event is triggered first and then the workbook is saved.

When saving an Excel workbook, there could be two possible scenarios:

- You’re saving it for the first time and it will show the Save As dialog box.

- You’ve already saved it earlier and it will simply save and overwrite the changes in the already saved version.

Now let’s have a look at a few examples where you can use the BeforeSave event.

Suppose you have a new workbook that you’re saving for the first time, and you want to remind the user to save it in the K drive, then you can use the below code:

Private Sub Workbook_BeforeSave(ByVal SaveAsUI As Boolean, Cancel As Boolean) If SaveAsUI Then MsgBox "Save this File in the K Drive" End Sub

In the above code, if the file has never been saved, SaveAsUI is True and brings up the Save As dialog box. The above code would display the message before the Save As dialog box appear.

Another example could be to update the date and time when the file is saved in a specific cell.

The below code would insert the date & time stamp in cell A1 of Sheet1 whenever the file is saved.

Private Sub Workbook_BeforeSave(ByVal SaveAsUI As Boolean, Cancel As Boolean)

Worksheets("Sheet1").Range("A1") = Format(Now, "dd-mmm-yyyy hh:mm:ss")

End Sub

Note that this code is executed as soon as the user saves the workbook. If the workbook is being saved for the first time, it will show a Save As dialog box. But the code is already executed by the time you see the Save As dialog box. At this point, if you decide to cancel and not save the workbook, the date and time would already be entered in the cell.

Workbook BeforeClose Event

Before Close event happens right before the workbook is closed.

The below code protects all the worksheets before the workbook is closed.

Private Sub Workbook_BeforeClose(Cancel As Boolean) Dim sh As Worksheet For Each sh In ThisWorkbook.Worksheets sh.Protect Next sh End Sub

Remember that the event code is triggered as soon as you close the workbook.

One important thing to know about this event is that it doesn’t care whether the workbook is actually closed or not.

In case the workbook has not been saved and you’re shown the prompt asking whether to save the workbook or not, and you click Cancel, it will not save your workbook. However, the event code would have already been executed by then.

Workbook BeforePrint Event

When you give the print command (or Print Preview command), the Before Print event is triggered.

The below code would recalculate all the worksheets before your workbook is printed.

Private Sub Workbook_BeforePrint(Cancel As Boolean) For Each ws in Worksheets ws.Calculate Next ws End Sub

When the user is printing the workbook, the event would be fired whether he/she is printing the entire workbook or only a part of it.

Another example below is of the code that would add the date and time to the footer when the workbook is printed.

Private Sub Workbook_BeforePrint(Cancel As Boolean) Dim ws As Worksheet For Each ws In ThisWorkbook.Worksheets ws.PageSetup.LeftFooter = "Printed On - " & Format(Now, "dd-mmm-yyyy hh:mm") Next ws End Sub

Worksheet Level Events (Explained with Examples)

Worksheet events take place based on the triggers in the worksheet.

Following are the most commonly used events in a worksheet.

| Event Name | What triggers the event |

| Activate | When the worksheet is activated |

| BeforeDelete | Before the worksheet is deleted |

| BeforeDoubleClick | Before the worksheet is double-clicked |

| BeforeRightClick | Before the worksheet is right-clicked |

| Calculate | Before the worksheet is calculated or recalculated |

| Change | When the cells in the worksheet are changed |

| Deactivate | When the worksheet is deactivated |

| PivotTableUpdate | When the Pivot Table in the worksheet is updated |

| SelectionChange | When the selection on the worksheet is changed |

Note that this is not a complete list. You can find the complete list here.

Remember that the code for Worksheet event is stored in the worksheet object code window (in the one in which you want the event to be triggered). There can be multiple worksheets in a workbook, and your code would be fired only when the event takes place in the worksheet in which it is placed.

Now let’s have a look at some useful worksheet events and see how these can be used in your day-to-day work.

Worksheet Activate Event

This event is fired when you activate a worksheet.

The below code unprotects a sheet as soon as it is activated.

Private Sub Worksheet_Activate() ActiveSheet.Unprotect End Sub

You can also use this event to make sure a specific cell or a range of cells (or a named range) is selected as soon as you activate the worksheet. The below code would select cell D1 as soon as you activate the sheet.

Private Sub Worksheet_Activate()

ActiveSheet.Range("D1").Select

End Sub

Worksheet Change Event

A change event is fired whenever you make a change in the worksheet.

Well.. not always.

There are some changes that trigger the event, and some that don’t. Here is a list of some changes that won’t trigger the event:

- When you change the formatting of the cell (font size, color, border, etc.).

- When you merge cells. This is surprising as sometimes, merging cells also removes content from all the cells except the top-left one.

- When you add, delete, or edit a cell comment.

- When you sort a range of cells.

- When you use Goal Seek.

The following changes would trigger the event (even though you may think it shouldn’t):

- Copy and pasting formatting would trigger the event.

- Clearing formatting would trigger the event.

- Running a spell check would trigger the event.

Below is a code would show a message box with the address of the cell that has been changed.

Private Sub Worksheet_Change(ByVal Target As Range) MsgBox "You just changed " & Target.Address End Sub

While this is a useless macro, it does show you how to use the Target argument to find out what cells have been changed.

Now let’s see a couple of more useful examples.

Suppose you have a range of cells (let’s say A1:D10) and you want to show a prompt and ask the user if they really wanted to change a cell in this range or not, you can use the below code.

It shows a prompt with two buttons – Yes and No. If the user selects ‘Yes’, the change is done, else it is reversed.

Private Sub Worksheet_Change(ByVal Target As Range)

If Target.Row <= 10 And Target.Column <= 4 Then

Ans = MsgBox("You are making a change in cells in A1:D10. Are you sure you want it?", vbYesNo)

End If

If Ans = vbNo Then

Application.EnableEvents = False

Application.Undo

Application.EnableEvents = True

End If

End Sub

In the above code, we check whether the Target cell is in first 4 columns and the first 10 rows. If that’s the case, the message box is shown. Also, if the user selected No in the message box, the change is reversed (by the Application.Undo command).

Note that I have used Application.EnableEvents = False before the Application.Undo line. And then I reversed it by using Application.EnableEvent = True in the next line.

This is needed as when the undo happens, it also triggers the change event. If I don’t set the EnableEvent to False, it will keep on triggering the change event.

You can also monitor the changes to a named range using the change event. For example, if you have a named range called “DataRange” and you want to show a prompt in case user makes a change in this named range, you can use the code below:

Private Sub Worksheet_Change(ByVal Target As Range)

Dim DRange As Range

Set DRange = Range("DataRange")

If Not Intersect(Target, DRange) Is Nothing Then

MsgBox "You just made a change to the Data Range"

End If

End Sub

The above code checks whether the cell/range where you have made the changes has any cells common to the Data Range. If it does, it shows the message box.

Workbook SelectionChange Event

The selection change event is triggered whenever there is a selection change in the worksheet.

The below code would recalculate the sheet as soon as you change the selection.

Private Sub Worksheet_SelectionChange(ByVal Target As Range) Application.Calculate End Sub

Another example of this event is when you want to highlight the active row and column of the selected cell.

Something as shown below:

The following code can do this:

Private Sub Worksheet_SelectionChange(ByVal Target As Range) Cells.Interior.ColorIndex = xlNone With ActiveCell .EntireRow.Interior.Color = RGB(248, 203, 173) .EntireColumn.Interior.Color = RGB(180, 198, 231) End With End Sub

The code first removes the background color from all the cells and then apply the one mentioned in the code to the active row and column.