Loanwords are words adopted by the speakers of one language from

a different language (the source language). A

loanword can also be called a borrowing.

The abstract noun borrowing refers to the process of speakers

adopting words

from a source language into their native language. «Loan» and

«borrowing» are of course metaphors, because there is no literal

lending process. There is no transfer from

one language to another, and no «returning» words to

the source language. The words simply come to be used by a speech

community that speaks a different language from the one these words

originated in.

Borrowing is a consequence of cultural contact between two language

communities. Borrowing of words can go in both directions between the

two languages in contact, but often there is an asymmetry, such that more words

go from one side to the other. In this case the source language

community has some advantage of power, prestige and/or wealth that

makes the objects and ideas it brings desirable and useful to the borrowing

language community. For example, the Germanic tribes in the first few

centuries A.D. adopted numerous loanwords from Latin as they

adopted new products via trade with the Romans. Few Germanic words, on

the other hand, passed into Latin.

The actual process of borrowing is complex and involves many usage

events (i.e. instances of use of the new word). Generally, some

speakers of the borrowing language know the source language too, or at

least enough of it to utilize the relevant word. They (often

consciously) adopt the new word when

speaking the borrowing language, because it most exactly fits the idea

they are trying to express. If they are bilingual in the source

language, which is often the case, they might pronounce the words the

same or similar to the way they are pronounced in the source language.

For example, English speakers adopted the word garage from

French, at first with a pronunciation nearer to the French

pronunciation than is now usually found. Presumably the very first

speakers who used the word in English knew at least some French and

heard the word used by French speakers, in a French-speaking context.

Those who first use the new word might use it at first only with

speakers of the source language who know the word, but at some point

they come to use the word with those to whom the word was not

previously known.

To these speakers the word may sound ‘foreign’. At this stage, when

most speakers do not know the word and if they hear it think it is

from another language, the word

can be called a foreign word. There are many foreign words

and phrases used in English such as bon vivant (French),

mutatis mutandis (Latin), and Fahrvergnuegen (German).

However, in time more speakers can become familiar with a new foreign

word or expression.

The community of users of this word can

grow to the point where even people who know little or nothing of the

source language understand, and even use, the novel word

themselves. The new word becomes

conventionalized: part of the conventional ways of speaking in

the borrowing language. At this point we call it a borrowing or loanword.

(It should be noted that not all foreign words do become loanwords; if they fall out of use

before they become widespread, they do not reach the loanword stage.)

Conventionalization is a gradual process in which a word progressively

permeates a larger and larger speech community, becoming part of ever

more people’s linguistic repetoire.

As part of its becoming more familiar to more people,

a newly borrowed word gradually adopts sound and other characteristics

of the borrowing language as speakers who do not know the source

language accommodate it to their own linguistic systems. In time,

people in the borrowing community do not perceive the word as a loanword at all. Generally, the longer a borrowed word

has been in the language, and the more frequently it is used, the more

it resembles the native words of the language.

English has gone through many periods in which large numbers of words

from a particular language were borrowed. These periods coincide with

times of major cultural contact between English speakers and those

speaking other languages. The waves of borrowing during periods

of especially strong cultural contacts are not sharply delimited, and

can overlap. For example, the Norse influence on English began already

in the 8th century A.D. and continued strongly well after the Norman

Conquest brought a large influx of Norman French to the language.

It is part of the cultural history of English speakers that they have

always adopted loanwords from the languages of whatever cultures they have

come in contact with. There have been few periods when borrowing

became unfashionable, and there has never been a national academy in

Britain, the U.S., or other English-speaking countries to

attempt to restrict new loanwords, as there has been in many continental

European countries.

The following list is a small sampling of the loanwords that came into

English in different periods and from different languages.

Latin

The forms given in this section are the Old English ones. The original Latin source word is given in parentheses where significantly different. Some Latin words were themselves originally borrowed from Greek. It can be deduced that these borrowings date from the time before the Angles and Saxons left the continent for England, because of very similar forms found in the other old Germanic languages (Old High German, Old Saxon, etc.). The source words are generally attested in Latin texts, in the large body of Latin writings that were preserved through the ages.

| ancor | ‘anchor’ |

| butere | ‘butter’ (L < Gr. butyros) |

| cealc | ‘chalk’ |

| ceas | ‘cheese’ (caseum) |

| cetel | ‘kettle’ |

| cycene | ‘kitchen’ |

| cirice | ‘church’ (ecclesia < Gr. ecclesia) |

| disc | ‘dish’ (discus) |

| mil | ‘mile’ (milia [passuum] ‘a thousand paces’) |

| piper | ‘pepper’ |

| pund | ‘pound’ (pondo ‘a weight’) |

| sacc | ‘sack’ (saccus) |

| sicol | ‘sickle’ |

| straet | ‘street’ ([via] strata ‘straight way’ or stone-paved road) |

| weall | ‘wall’ (vallum) |

| win | ‘wine’ (vinum < Gr. oinos) |

Latin

| apostol | ‘apostle’ (apostolus < Gr. apostolos) |

| casere | ‘caesar, emperor’ |

| ceaster | ‘city’ (castra ‘camp’) |

| cest | ‘chest’ (cista ‘box’) |

| circul | ‘circle’ |

| cometa | ‘comet’ (cometa < Greek) |

| maegester | ‘master’ (magister) |

| martir | ‘martyr’ |

| paper | ‘paper’ (papyrus, from Gr.) |

| tigle | ’tile’ (tegula) |

Celtic

| brocc | ‘badger’ |

| cumb | ‘combe, valley’ |

(few ordinary words, but thousands of place and river names: London, Carlisle,

Devon, Dover, Cornwall, Thames, Avon…)

Scandinavian

Most of these first appeared in the written language in Middle English; but many were no doubt borrowed earlier, during the period of the Danelaw (9th-10th centuries).

- anger, blight, by-law, cake, call, clumsy, doze, egg, fellow, gear, get, give, hale, hit, husband, kick, kill, kilt, kindle, law, low, lump, rag, raise, root, scathe, scorch, score, scowl, scrape, scrub, seat, skill, skin, skirt, sky, sly, take, they, them, their, thrall, thrust, ugly, want, window, wing

- Place name suffixes: -by, -thorpe, -gate

French

- Law and government—attorney, bailiff, chancellor, chattel, country, court, crime, defendent, evidence, government, jail, judge, jury, larceny, noble, parliament, plaintiff, plea, prison, revenue, state, tax, verdict

- Church—abbot, chaplain, chapter, clergy, friar, prayer, preach, priest, religion, sacrament, saint, sermon

- Nobility—baron, baroness; count, countess; duke, duchess; marquis, marquess; prince, princess; viscount, viscountess; noble, royal (contrast native words: king, queen, earl, lord, lady, knight, kingly, queenly)

- Military—army, artillery, battle, captain, company, corporal, defense,enemy,marine, navy, sergeant, soldier, volunteer

- Cooking—beef, boil, broil, butcher, dine, fry, mutton, pork, poultry, roast, salmon, stew, veal

- Culture and luxury goods—art, bracelet, claret, clarinet, dance, diamond, fashion, fur, jewel, oboe, painting, pendant, satin, ruby, sculpture

- Other—adventure, change, charge, chart, courage, devout, dignity, enamor, feign, fruit, letter, literature, magic, male, female, mirror, pilgrimage, proud, question, regard, special

Also Middle English French loans: a huge number of words in age, -ance/-ence, -ant/-ent, -ity, -ment, -tion, con-, de-, and pre- .

Sometimes it’s hard to tell whether a given word came from French or whether it was taken straight from Latin. Words for which this difficulty occurs are those in which there were no special sound and/or spelling changes of the sort that distinguished French from Latin

The effects of the renaissance begin to be seriously felt in England. We see the beginnings of a huge influx of Latin and Greek words, many of them learned words imported by scholars well versed in those languages. But many are borrowings from other languages, as words from European high culture begin to make their presence felt and the first words come in from the earliest period of colonial expansion.

Latin

- agile, abdomen, anatomy, area, capsule, compensate, dexterity, discus, disc/disk, excavate, expensive, fictitious, gradual, habitual, insane, janitor, meditate, notorious, orbit, peninsula, physician, superintendent, ultimate, vindicate

Greek (many of these via Latin)

- anonymous, atmosphere, autograph, catastrophe, climax, comedy, critic, data, ectasy, history, ostracize, parasite, pneumonia, skeleton, tonic, tragedy

- Greek bound morphemes: -ism, -ize

Arabic

- via Spanish—alcove, algebra, zenith, algorithm, almanac, azimuth, alchemy, admiral

- via other Romance languages—amber, cipher, orange, saffron, sugar, zero, coffee

Period of major colonial expansion, industrial/technological revolution, and American immigration.

Words from European languages

French

French continues to be the largest single source of new words outside of very specialized vocabulary domains (scientific/technical vocabulary, still dominated by classical borrowings).

- High culture—ballet, bouillabaise, cabernet, cachet, chaise longue, champagne, chic, cognac, corsage, faux pas, nom de plume, quiche, rouge, roulet, sachet, salon, saloon, sang froid, savoir faire

- War and Military—bastion, brigade, battalion, cavalry, grenade, infantry, pallisade, rebuff, bayonet

- Other—bigot, chassis, clique, denim, garage, grotesque, jean(s), niche, shock

- French Canadian—chowder

- Louisiana French (Cajun)—jambalaya

Spanish

- armada, adobe, alligator, alpaca, armadillo, barricade, bravado, cannibal, canyon, coyote, desperado, embargo, enchilada, guitar, marijuana, mesa, mosquito, mustang, ranch, taco, tornado, tortilla, vigilante

Italian

- alto, arsenal, balcony, broccoli, cameo, casino, cupola, duo, fresco, fugue, gazette (via French), ghetto, gondola, grotto, macaroni, madrigal, motto, piano, opera, pantaloons, prima donna, regatta, sequin, soprano, opera, stanza, stucco, studio, tempo, torso, umbrella, viola, violin

- from Italian American immigrants—cappuccino, espresso, linguini, mafioso, pasta, pizza, ravioli, spaghetti, spumante, zabaglione, zucchini

Dutch, Flemish

- Shipping, naval terms—avast, boom, bow, bowsprit, buoy, commodore, cruise, dock, freight, keel, keelhaul, leak, pump, reef, scoop, scour, skipper, sloop, smuggle, splice, tackle, yawl, yacht

- Cloth industry—bale, cambric, duck (fabric), fuller’s earth, mart, nap (of cloth), selvage, spool, stripe

- Art—easel, etching, landscape, sketch

- War—beleaguer, holster, freebooter, furlough, onslaught

- Food and drink—booze, brandy(wine), coleslaw, cookie, cranberry, crullers, gin, hops, stockfish, waffle

- Other—bugger (orig. French), crap, curl, dollar, scum, split (orig. nautical term), uproar

German

- bum, dunk, feldspar, quartz, hex, lager, knackwurst, liverwurst, loafer, noodle, poodle, dachshund, pretzel, pinochle, pumpernickel, sauerkraut, schnitzel, zwieback, (beer)stein, lederhosen, dirndl

- 20th century German loanwords—blitzkrieg, zeppelin, strafe, U-boat, delicatessen, hamburger, frankfurter, wiener, hausfrau, kindergarten, Oktoberfest, schuss, wunderkind, bundt (cake), spritz (cookies), (apple) strudel

Yiddish (most are 20th century borrowings)

- bagel, Chanukkah (Hanukkah), chutzpah, dreidel, kibbitzer, kosher, lox, pastrami (orig. from Romanian), schlep, spiel, schlepp, schlemiel, schlimazel, gefilte fish, goy, klutz, knish, matzoh, oy vey, schmuck, schnook,

Scandinavian

- fjord, maelstrom, ombudsman, ski, slalom, smorgasbord

Russian

- apparatchik, borscht, czar/tsar, glasnost, icon, perestroika, vodka

Words from other parts of the world

Sanskrit

- avatar, karma, mahatma, swastika, yoga

Hindi

- bandanna, bangle, bungalow, chintz, cot, cummerbund, dungaree, juggernaut, jungle, loot, maharaja, nabob, pajamas, punch (the drink), shampoo, thug, kedgeree, jamboree

Dravidian

- curry, mango, teak, pariah

Persian (Farsi)

- check, checkmate, chess

Arabic

- bedouin, emir, jakir, gazelle, giraffe, harem, hashish, lute, minaret, mosque, myrrh, salaam, sirocco, sultan, vizier, bazaar, caravan

African languages

- banana (via Portuguese), banjo, boogie-woogie, chigger, goober, gorilla, gumbo, jazz, jitterbug, jitters, juke(box), voodoo, yam, zebra, zombie

American Indian languages

- avocado, cacao, cannibal, canoe, chipmunk, chocolate, chili, hammock, hominy, hurricane, maize, moccasin, moose, papoose, pecan, possum, potato, skunk, squaw, succotash, squash, tamale (via Spanish), teepee, terrapin, tobacco, toboggan, tomahawk, tomato, wigwam, woodchuck

- (plus thousands of place names, including Ottawa, Toronto, Saskatchewan and the names of more than half the

states of the U.S., including Michigan, Texas, Nebraska, Illinois)

Chinese

- chop suey, chow mein, dim sum, ketchup, tea, ginseng, kowtow, litchee

Japanese

- geisha, hara kiri, judo, jujitsu, kamikaze, karaoke, kimono, samurai, soy, sumo, sushi, tsunami

Pacific Islands

- bamboo, gingham, rattan, taboo, tattoo, ukulele, boondocks

Australia

- boomerang, budgerigar, didgeridoo, kangaroo (and many more in Australian English)

Lecture №2. Foreign Elements in Modern English. International Words

The term source of borrowing should be distinguished from the term origin of borrowing. The first should be applied to the language from which the loan word was taken into English. The second, on the other hand, refers to the language to which the word may be traced. Thus, the word paperhas French as its source of borrowing and Greek as its origin. It may be observed that several of the terms for items used in writing show their origin in words denoting the raw material. Papyros is the name of a plant; cf. book“the beech tree” (boards of which were used for writing).

Alongside loan words, we distinguish loan translation and semantic loans. Translation loans are words or expressions formed from the elements existing in the English language according to the patterns of the source language. They are not taken into the vocabulary of another language more or less in the same phonemic shape in which they have been functioning in their own language, but undergo the process of translation. It is quite obvious that it is only compound words (i. e. words of two or more stems) which can be subjected to such an operation, each stem being translated separately: masterpiece (from Germ. Meisterstück), wonder child (from Germ. Wunderkind), first dancer (from Ital. prima-ballerina), the moment of truth (from Sp. el momento de la verdad), collective farm (from Rus. колхоз), five-year plan (from Rus. пятилетка). The Russian колхоз was borrowed twice, by way of translation-loan (collective farm) and by way of direct borrowing (kolkhoz). The case is not unique. During the 2nd World War the German word Blitzkrieg was also borrowed into English in two different forms: the translation-loan lightning-war and the direct borrowings blitzkrieg and blitz: Eng. chain-smoker Ger. Kettenraucher; Eng. wall newspaper Rus. стенная газета; Ukr. настінна газета; Eng. (it) goes without saying Fr (cela) vasans dire; Eng. summit conference Ger. Gipfet Konferenz conference au sommet.

The term semantic loan, is used to denote the development in an English word of a new meaning due to the influence of a related word in another language, e.g. the compound word shock brigade which existed in the English language with the meaning «аварийна бригада» acquired a new meaning «ударная бригада» which it borrowed from the Russian language. Eng. pioneer — explorer; one who is among the first in new fields of activity; Rus пионер – a member of the Young Pioneers’ Organization. Each time two nations come into close contact, certain borrowings are a natural consequence. The nature of the contact may be different. It may be wars, invasions or conquests when foreign words are in effect imposed upon the reluctant conquered nation. There are also periods of peace when the process of borrowing is due to trade and international cultural relations. These latter circumstances are certainly more favourable for stimulating the borrowing process, for during invasions and occupations the natural psychological reaction of the oppressed nation is to reject and condemn the language of the oppressor. In this respect the linguistic heritage of the Norman Conquest seems exceptional, especially if compared to the influence of the Mongol-Tartar Yoke on the Russian language. The Mongol-Tartar Yoke also represented a long period of cruel oppression, yet the imprint left by it on the Russian vocabulary is comparatively insignificant.

The difference in the consequences of these evidently similar historical events is usually explained by the divergence in the level of civilisation of the two conflicting nations. Russian civilisation and also the level of its language development at the time of the Mongol-Tartar invasion were superior to those of the invaders. That is why the Russian language successfully resisted the influence of a less developed language system. On the other hand, the Norman culture of the lithe, was certainly superior to that of the Saxons. The result was that an immense number of French words forced their way into English vocabulary. Yet, linguistically speaking, this seeming defeat turned into a victory. Instead of being smashed and broken by the powerful intrusion of the foreign element, the English language managed to preserve its essential structure and vastly enriched its expressive resources with the new borrowings.

Sometimes the borrowing process is to fill a gap in vocabulary. When the Saxons borrowed Latin words for butter, plum, beet, they did it because their own vocabularies lacked words for these new objects. For the same reason the words potato and tomato were borrowed by English from Spanish when these vegetables were first brought to England by the Spaniards. But there is also a great number of words which are borrowed for other reasons. There may be a word (or even several words) which expresses some particular concept, so that there is no gap in the vocabulary and there does not seem to be any need for borrowing. Yet, one more word is borrowed which means almost the same, – almost, but not exactly. It is borrowed because it represents the same concept in some new aspect, supplies a new shade of meaning or a different emotional colouring. This type of borrowing enlarges groups of synonyms and greatly provides to enrich the expressive resources of the vocabulary. That is how the Latin cordial was added to the native friendly, the French desire to wish, the Latin admire and the French adore to like and love.

English vocabulary, which is one of the most extensive amongst the world’s languages contains an immense number of words of foreign origin. Explanations for this should be sought in the history of the language which is closely connected with the history of the nation speaking the language. In order to have a better understanding of the problem, it will be necessary to go through a brief survey of certain historical facts, relating to different epochs.

The first century B. C. Most of the territory, known to us as Europe was occupied by the Roman Empire. Among the inhabitants of the continent were Germanic tribes, «barbarians» as the arrogant Romans called them. Theirs was really a rather primitive stage of development, especially if compared with the high civilisation and refinement of Rome. They were primitive cattle-breeders and knew almost nothing about land cultivation. Their tribal languages contained only Indo-European and Germanic elements. After a number of wars between the Germanic tribes and the Romans these two opposing peoples came into peaceful contact. Trade was carried on, and the Germanic people gained knowledge of new and useful things. The first among them were new things to eat. They were to use the Latin words to name them. It was also to the Romans that the Germanic tribes owed the knowledge of some new fruits and vegetables of which they had no idea before, and the Latin names of these fruits and vegetables entered their vocabularies reflecting this new knowledge: cherry (Lat. cerasum), pear (Lat. pirum), plum (Lat. prunus), pea (Lat. pisum), beet (Lat. beta), pepper (Lat. piper). Some more examples of Latin borrowings of this period are: cup (Lat. cuppa), kitchen (Lat. coquina), mill (Lat. molina), port (Lat. portus), wine (Lat. vinum). The fact that all these borrowings occurred is in itself significant. It was certainly important that the Germanic tribal languages gained a considerable number of new words and were thus enriched. What was even more significant was that all these Latin words were destined to become the earliest group of borrowings in the future English language which was – much later – built on the basis of the Germanic tribal languages.

The fifth century A. D. Several of the Germanic tribes (the most numerous amongst them being the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes) migrated across the sea now known as the English Channel to the British Isles. There they were confronted by the Celts, the original inhabitants of the Isles. The Celts desperately defended their lands against the invaders, but they were no match for the military-minded Teutons and gradually yielded most of their territory. They retreated to the North and South-West (moden Scotland, Wales and Cornwall). Through their numerous contacts with the defeated Celts, the conquerors got to know and assimilated a number of Celtic words (Modern English bald, down, glen, druid, bard, cradle). Especially numerous among the Celtic borrowings were place names, names of rivers, bills, etc. The Germanic tribes occupied the land, but the names of many parts and features of their territory remained Celtic. For instance, the names of the rivers Avon, Exe, Esk, Usk, Ux originate from Celtic words meaning «river» and «water». Even the name of the English capital originates from Celtic Llyn + dun in which llyn is another Celtic word for «river» and dun stands for «a fortified hill», the meaning of the whole being «fortress on the hill over the river». Some Latin words entered the Anglo-Saxon languages through Celtic, among them such widely-used words as street (Lat. strata via) and wall (Lat. vallum).

The seventh century A. D. This century was significant for the christianisation of England. Latin was the official language of the Christian church, and consequently the spread of Christianity was accompanied by a new period of Latin borrowings. These no longer came from spoken Latin as they did eight centuries earlier, but from church Latin. Also, these new Latin borrowings were very different in meaning from the earlier ones. They mostly indicated persons, objects and ideas associated with church and religious rituals. E. g. priest (Lai. presbyter), bishop (Lai. episcopus), monk (Lat. monachus), nun (Lai. nonna), candle (Lai. candela). Additionally, in a class of their own were educational terms. It was quite natural that these were also Latin borrowings, for the first schools in England were church schools, and the first teachers priests and monks. So, the word school is a Latin borrowing (Lat. schola, of Greek origin) and so are such words as scholar (Lai. scholar(-is) and magister (Lat. ma-gister).

From the end of the 8th c. to the middle of the lithe. England underwent several Scandinavian invasions which inevitably left their trace on English vocabulary. Here are some examples of early Scandinavian borrowings: call, v., take, v., cast, v., die, v., law, п., husband, n. (hus+bondi, i. e. «inhabitant of the house»), window n. (vindauga, i. e. «the eye of the wind»), loose, adj., low, adj., weak, adj. Some of the words of this group are easily recognisable as Scandinavian borrowings by the initial sk- combination. E.g. sky, skin, ski, skirt. Certain English words changed their meanings under the influence of Scandinavian words of the same root. So, the Оld English bread which meant «piece» acquired its modern meaning by association with the Scandinavian brand. The О. E. dream which meant «joy» assimilated the meaning of the Scandinavian draumr (with the Germ. Traum «dream» and the Russian дрёма).

1066. With the famous Battle of Hastings, when the English were defeated by the Normans under William the Conqueror, we come to the eventful epoch of the Norman Conquest. The epoch can well be called eventful not only in national, social, political and human terms, but also in linguistic terms. England became a bi-lingual country, and the impact on the English vocabulary made over this two-hundred-years period is immense: French words from the Norman dialect penetrated every aspect of social life. Here is a very brief list of examples of Norman French borrowings.

Administrative words: state, government, parliament, council, power.

Legal terms: court, judge, justice, crime, prison.

Military terms: army, war, soldier, officer, battle, enemy.

Educational terms: pupil, lesson, library, science, pen, pencil.

Everyday life was not unaffected by the powerful influence of French words. Numerous terms of everyday life were also borrowed from French in this period: e. g. table, plate, saucer, dinner, supper, river, autumn, uncle, etc.

The Renaissance Period. In England, as in all European countries, this period was marked by significant developments in science, art and culture and, also, by a revival of interest in the ancient civilisations of Greece and Rome and their languages. Hence, they occurred a considerable number of Latin and Greek borrowings. In contrast to the earliest Latin borrowings (1st c. B. C), the Renaissance ones were rarely concrete names. They were mostly abstract words (e. g. major, minor, intelligent, permanent, to elect, to create). There were naturally numerous scientific and artistic terms (datum, status, phenomenon, philosophy, method, music). The same is true of Greek Renaissance borrowings (e. g. atom, cycle, ethics). The Renaissance was a period of extensive cultural contacts between the major European states. Therefore, it was only natural that new words also entered the English vocabulary from other European languages. The most significant once more were French borrowings. This time they came from the Parisian dialect of French and are known as Parisian borrowings: routine, police, machine, ballet, scene, technique etc. Italian also contributed a considerable number of words to English, e. g. piano, violin, opera, alarm, colonel. Latin Loans are classified into the subgroups:

Early Latin Loans. Those are the words which came into English through the language of Anglo-Saxon tribes. The tribes had been in contact with Roman civilization and had adopted several Latin words denoting objects belonging to that civilization long before the invasion of Angles, Saxons and Jutes into Britain (cup, kitchen, wine).

Later Latin Borrowings. To this group belong the words which penetrated the English vocabulary in the sixth and seventh centuries, when the people of England when converted to Christianity (priest, bishop, nun, candle).

The third period of Latin includes words which came into English due to two historical events: the Norman conquest in 1066 and the Renaissance or the Revival of Learning. Some words came into English through French but some were taken directly from Latin (major, minor, intelligent, permanent).

The Latest Stratum of Latin Words. The words of this period are mainly abstract and scientific words (nylon, molecular, phenomenon, vacuum).

Norman-French Borrowings may be subdivided into subgroups:

Early loans – 12th – 15th century.

Later loans – beginning from the 16th century.

T

he Early French borrowings are simple short words, naturalized in accordance with the English language system (state, power, war, pen, river). Later French borrowings can

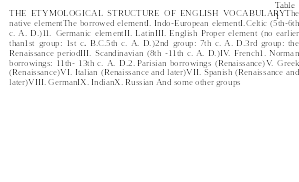

be identified by their peculiarities of form and pronunciation (police, ballet, scene) (table 1). There are certain structural features which enable us to identify some words as borrowings and even to determine the source language.

Lexical correlations are defined as lexical units from different languages which are phonetically and semantically related. The number of Ukrainian-English lexical correlations is about 6870. The history of the Slavonic-German ties resulted in the following correlations: beat – бити, widow – вдова, call – голос, young – юний, day – день etc. Some Ukrainian-English lexical correlations have common Indo-European back-ground: garden – город, murder – мордувати, soot – сажа. Beside Ukrainian – English lexical correlations the Ukrainian language contains borrowings from modern English period: брифінг – briefing; хіт парад – hit parade; диск – жокей – disk – jockey; кітч, халтура – kitch; ескапізм – escapism; масс-медія – mass media; естеблішмент – establishment; серіал – serial.

INTERNATIONAL WORDS

Expanding global contacts result in the considerable growth of international vocabulary. All languages depend for their changes upon the cultural and social matrix in which they operate and various contacts between nations are part of this matrix reflected in vocabulary. International words play an especially prominent part in various terminological systems including the vocabulary of science, industry and art. The etymological sources of this vocabulary reflect the history of world culture. Thus, for example, the mankind’s cultural debt to Italy is reflected in the great number of Italian words connected with architecture, painting and especially music that are borrowed into most European languages: allegro, aria, barcarole, baritone (and other names for voices), concert, opera (and other names for pieces of music), piano and many more. The rate of change in technology, political, social and artistic life has been greatly accelerated in the 20th century and so has the rate of growth of international word stock. A few examples of comparatively new words due to the progress of science will suffice to illustrate the importance of international vocabulary: algorithm, antenna, antibiotic, cybernetics, gene, genetic code, microelectronics, etc. All these show sufficient likeness in English, French, Russian and several other languages. The international word stock is also growing due to the influx of exotic borrowed words like anaconda, bungalow, kraal etc. These come from many different sources. International words should not be mixed with words of the common Indo-European stock that also comprise a sort of common fund of the European languages. This layer is of great importance for the foreign language teacher not only because many words denoting abstract notions are international but also because he must know the most efficient ways of showing the points of similarity and difference between such words as control – контроль; general – генерал; industry – индустрия or magazine – магазин, etc. usually called ‘translator’s false friends’. The treatment of international words at English lessons would be one-sided if the teacher did not draw his pupils’ attention to the spread of the English vocabulary into other languages. We find numerous English words in the field of sport: football, match, tennis, time. A large number of English words are to be found in the vocabulary pertaining to clothes: sweater, nylon, tweed, etc. Cinema and different forms of entertainment are also a source of many international words of English origin: film, club, jazz. At least some of the Russian words borrowed into English and many other languages and thus international should also be mentioned: balalaika, czar, Kremlin, soviet, sputnik, vodka. To sum up this brief treatment of loan words it is necessary to stress that in studying loan words a linguist cannot be content with establishing the source, the date of penetration, the semantic sphere to which the word belonged and the circumstances of the process of borrowing. All these are very important, but one should also be concerned with the changes the new language system into which the loan word penetrates causes in the word itself, and, on the other hand, look for the changes occasioned by the newcomer in the English vocabulary, when in finding its way into the new language it pushed some of its lexical neighbours aside. In the discussion above we have tried to show the importance of the problem of conformity with the patterns typical of the receiving language and its semantic needs.

So, international words are defined as “words of identical origin that occur in several languages as a result of simultaneous or successive borrowings from one ultimate source” (I. V. Arnold). International words reflect the history of word culture, they convey notions which are significant in communication. New inventions, political institutions, leisure activities, science, technological advances have all generated new lexemes and continue to do so: sputnik, television, antenna, gene, cybernetics, bungalow, anaconda, coffee, chocolate, grapefruit, etc. The English language contributed a considerable number of international words to world languages, e.g. the sports terms: football, baseball, cricket, golf. International words are mainly borrowings.

12

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

The modern English language vocabulary possesses a rich history and is characterized by a great number of borrowed words from other languages during different steps of its development.

The reasons why the words were borrowed into English are the following:

Close interaction with a nation for whom English is not the mother tongue

A certain language is imposed on the English people as a result of numerous invasions

The mother tongue lacks the word for denoting a certain notion or object

The notion or object, which is peculiar for another country, is borrowed by the English people, altogether with the word, denoting the object.

The words are borrowed from another language as synonyms that give various shades of meaning to the words already existing in the language. [Арнольд 1986: 205]

Throughout the centuries, the British Isles underwent waves of invasions by Romans, Danes, and Norman French, each inevitably contributing to the way of life on the conquered land and leaving their trace on English vocabulary. [J.Algeo 2010: 247]

The words of Latin origin began to appear in the English language in the 1st century BC. This process is closely connected with the occupation of the territory belonging to Germanic tribes by the Roman invaders. The adopted words naturally indicate the new conceptions that the Germanic peoples acquired from this contact with a higher civilization. [Albert C.Baugh, Thomas Cable 2002: 73]

During this period, mainly the words having to do with agriculture, cattle-breeding, and military affairs were borrowed. Many of the words borrowed in the Old English period have survived into Modern English. Among them are the following words: ancor ‘anchor’ (Lat. ancora), butere ‘butter’ (Lat. būtyrum), cealc ‘chalk’ (Lat. calx), cēse ‘cheese’ (Lat. cāseus), cetel ‘kettle’ (Lat. catillus), cycene ‘kitchen’ (Vul. Lat. cucīna, var. of coquīna), disc ‘dish’ (Lat. discus), mangere ‘-monger, trader’ (Lat. mangō), mīl ‘mile’ (Lat. mīlia [passuum]), piper ‘pepper’ (Lat. piper), pund ‘pound’ (Lat. pondō ), sacc ‘sack’ (Lat. saccus), sicol ‘sickle’ (Lat. secula), strǣt ‘ (Lat. [via] strata ), weall ‘wall’ (Lat. vallum). [J.Algeo 2010: 249]

Moreover, the Germanic tribes owe the knowledge of some new fruits and vegetables of which they had no idea before to the Romans. Thus, the English vocabulary was enlarged by the Latin names for new food products, such as cherry (Lat. cerasum), pear (Lat. pirum), plum (Lat. plunus), pea (Lat. pisum), beet (Lat.beta), plant (Lat.planta). [Антрушина 1985: 35]

A large plaster of borrowed Latin words appeared in the English language as a result of Christianization of England in the 7th century AD. The borrowed words indicated the objects and ideas associated with church and religious rituals. [Антрушина 1985: 36] E.g. alter ‘altar’ (Lat. altar), (a)postol ‘apostle’ (Lat. apostolus), balsam (Lat. balsamum), dēmon (Lat. daemon), messe ‘mass’ (Lat. missa, позже messa), martir ‘martyr. [J.Algeo 2010: 250]

The introduction of Christianity meant the building of churches and the establishment of monasteries. Latin, the language of the services and of ecclesiastical learning, became widely spread throughout England. Schools were established in most of the monasteries and churches. [Albert C.Baugh, Thomas Cable 2002: 76]

A great number of Latin borrowings came into usage during the New English period (since 1500). The words were borrowed at the same time directly from Latin and from Greek as the ultimate source with the Latin as the immediate source. [Антрушина 1985: 38; J.Algeo 2010: 251]. All these words enriched the English language vocabulary in the fields of science, art and culture: e.g. datum, status, phenomenon, philosophy, method, music [Антрушина 1985: 38].

It is difficult to overestimate the immense impact on English vocabulary made by the French language. After the Norman Conquest, the Anglo-Saxon nobility was deprived of their real estate and political rights. All the leading positions were distributed among the Norman conquerors, thus, French became the language of the official class in England. [Аракин 2003: 173].

French words of Norman dialect penetrated every aspect of social life, but most of the words had to do with political life and government (counsel, government, state, parliament, country); judicial proceedings (court, judge, justice, condemn, attorney); army and military affairs (war, battle, army, regiment, victory, cannon, mail). Construction and architecture (palace, pillar, chapel); religion and church (religion, clergy, parish, prayer); school (lesson, pupil, pen, pencil); trade (fair, market, money, mercer) and art (art, colour, ornament).

There is also a great number of loan translations from French, such as marriage of convenience (mariage de conveyance), that goes without saying (ça va sans dire), and trial balloon (ballon d’essai).

It is interesting to note that the same French word may be borrowed at various periods in the history of English, like gentle (thirteenth century), genteel (sixteenth century), and jaunty (seventeenth century), all from French gentil. (Gentile, however, was taken straight from Latin gentīlis, meaning ‘foreign’ in post Classical Latin.) It is similar with chief, first occurring in English in the fourteenth century, and chef, in the nineteenth. [J.Algeo 2010: 256]

In Modern English, there are the words of French origin and the native English words, which denote the same notion. However, they are different in their stylistic value. The English words are neutral, and the borrowed French words may be characterized as “bookish” and “high-flown” [Аракин 2003: 177]. E.g. (to begin — to commence, to come – to arrive, to wish – to desire, to do – to act, speech – discourse, harm – injury, help — aid).

The Renaissance period is characterized by extensive cultural contacts between the major European states. During this period, a great number of words of French origin entered the English language and enriched its vocabulary in the fields of science, culture and art. The peculiar feature of such borrowings is that their French pronunciation is preserved. (machine, police, magazine, ballet, matinée, scene, technique). [Антрушина 1985: 38]

Scandinavian loanwords appeared in the English language at the end of the 8th century AD, when England underwent several Scandinavian invasions.

The newly borrowed words did not denote any new notions – they indicated commonly used objects and habitual actions. [Аракин 2003: 169] In some cases, Scandinavian borrowings so closely resemble their English cognates that it becomes almost impossible to say whether the word was borrowed or not.

Sometimes an English word acquired a new meaning under the influence of a Scandinavian word similar in form. The initial meaning of the word “dream”, for instance, was “joy”. Later on, under the Scandinavian influence it changed its meaning according to the cognate word draumr ‘vision in sleep. ’

Most of the words in Modern English beginning with the sound combination [sk] are of Scandinavian origin e.g. scowl, scrape, scrub, skill, skin, skirt, sky.

References

Антрушина Г.Б., Афанасьева О.В., Морозова Н.Н. Лексикология английского языка. — М.: Высшая школа, 1985. — 223 с.

Аракин В.Д. История английского языка. — М.: ФИЗМАТЛИТ, 2003. — 272 с.

Арнольд И.В. Лексикология современного английского языка. — М. : Высшая школа, 1986. — 295 с.

Пословицы в фразеологическом поле: когнитивный, дискурсивный, сопоставительный аспекты: монография / Н.Ф. Алефиренко [и др.]; под ред. проф. Т.Н. Федуленковой. – Владимир: Изд-во ВлГУ, 2017. 231 с. (С. 176-196)

Современная фразеология: тенденции и инновации: монография (том посвящается д.ф.н. проф. Т.Н. Федуленковой по случаю юбилея) / Н.Ф. Алефиренко, В.И. Зимин, Т.Н. Федуленкова и др. – М.-СПб-Брянск: «Новый проект», 2016. – 200 с.

Традиции и инновации в лингвистике и лингводидактике: Материалы Международ. конф. в честь 65-летия д.ф.н. проф. Т.Н. Федуленковой / ВлГУ им. А.Г. и Н.Г. Столетовых. Владимир, 2015. 268 c.

Федуленкова Т.Н. Лекции по английской фразеологии библейского происхождения. М.: ИД АЕ, 2016. – 146 с.

Федуленкова Т.Н. Сопоставительная фразеология английского, немецкого и шведского языков: курс лекций. М.: ИД Акад. Естествознания, 2012. – 220 с.

Федуленкова Т.Н., Адамия З.К., Чабашвили М. и др. Фразеологическое пространство национального словаря в сопоставительном аспекте: монография. Т.2. / под ред. Т.Н. Федуленковой. – М.: ИД Академии Естествознания, 2014. – 140 с.

Федуленкова Т.Н., Иванов А.В., Куприна Т.В. и др. Фразеология и терминология: грани пересечения: монография – Архангельск: Поморский университет, 2009. – 170 с.

Федуленкова Т.Н., Садыкова А.Г., Давлетбаева Д.Н. Фразеологическое пространство национального словаря в сопоставительном аспекте: монография. Т.1. / отв ред. Т.Н. Федуленкова. – Архангельск: Поморский университет, 2008. – 200 с.

Cross-Linguistic and Cross-Cultural Approaches to Phraseology: ESSE-9, Aarhus, 22-26 August 2008 / T. Fedulenkova (ed.). Arkhangelsk; Aarhus, 2009. 209 p.

John Algeo The Origins and Development of the English Language:. — Wadsworth: Cengage Learning, 2010. — 347 с.

Albert C.Baugh, Thomas Cable A History of the English Language. London: Routledge, 2002. 447 с.

The English language has many borrowed words. English is basically a Germanic language by structure. English vocabulary, however, comes from everywhere. In this posting I talk briefly about the history of English and where many of its borrowed words come from. Finally I talk about parts of many common English words that came from Greek or Latin. There will be many example words and sentences. The download at the end will give you more practice using and understanding borrowed words in English.

How borrowed words work in English

Prior to 1066, the people living in the British Isles had no need for borrowed words. They spoke a German language called Old English. It is related to what we speak today. In 1066, William the Conqueror of France conquered Britain. The language of the nobles became French. The common people, however, still spoke Old English. Because of this, a double vocabulary developed in English. For example, everyone liked pork. The nobles called it by the French word, porc, while the common people called it swine. Both words exist in modern English, although pork is more common. As Christianity spread, more words form other European counties crept into English.

Some fun facts about borrowed words

Here is a brief summary of where many borrowed words in English come from: Latin–29%, French–29%, Greek–6%, other languages–6%, and proper names–4%. That leaves only 26% of English words that are actually English! There is very little that is original about English. Since its words come form so many languages, many may have come from yours.

When English borrowed words, it kept the original spellings from the original languages. All languages borrow words, but many change the rules to fit their phonetics. For example, photograph is a Greek word. Ph has the sound /f/ in Greek. English has kept the ph, but Spanish has changed it to f as in fotografia. This is why English spelling is so difficult and often does not make sense, even for native English speakers.

Some common borrowed words in English

Below is a list of borrowed words and the language they come from. You probably use many f these words every day.

- dollar (Dutch)–connected to a mint where coins are made.

- zero (Arabic)–Many words relating to math come form Arabic.

- alarm (Italian)–to arms

- banana, zebra, jumbo, yam (African tribal languages)

- ketchup (Chinese)

- pyjamas (Urdu and Persian)

- giraffe (Arabic)

- anime, sushi, karaoke (Japanese)

- moccasin (Native American tribal languages)

- ski (Norwegian)

- penguin (Welsh)

- ballot (Italian)–means a small pebble cast into a box to vote

- canteloupe (Italian)–named after a town where this melon grows

- massage (French)

Common parts of words borrowed from Greek

Many common English words were borrowed, in part form Greek. Many other languages have also borrowed these word parts, so you language may have cognates with these words. This will make it easier for you to earn them. You will see the word part, some example words, and an example sentence.

- anti (against)–antibacterial. You need to shower with antibacterial soap before surgery.

- ast (er)–astronomy, asteroid. Astronomy is the study of stars and planets.

- aqu (water)–aquarium. A fish may live in an aquarium.

- auto (self)–automatic. An automatic transmission changes gears by itself.

- bio (life)–biology, biography. A biography is the story of someone’s life.

- chrome (color)–monochrome. A monochrome image has only one color.

- chrono (time)–chronicle. A chronicle is a story told over time.

- geo (earth)–geology. Geology is the study of the earth.

- graph (write)–autograph. Your autograph is your signature.

- hydr (water)–dehydrate. If you don’t drink enough water, you may become dehydrated.

- path (feel)–sympathy. I felt sympathy for her when her father died.

- phono (sound)–telephone. You can hear someone’s voice on the telephone.

- photo (light)–photocopy. Please make a photocopy of this recipe for me.

- tele (far)–television. A television lets you see shows all over the world.

Some common parts of words borrowed from Latin

Although no one speaks Latin anymore, many parts of Latin live on in word parts. Many languages have borrowed from Latin, especially for math, science, and medical words. Chances are you have Latin cognates in your language.

- audi (hear)–audience. The audience enjoyed the concert.

- bene (good)–benefit. My new job has many excellent benefits.

- brev (short– brief, abbreviate. We can abbreviate Mister to Mr.

- circ (round)–circle, circus, circulate. We may need to circulate if there is no place to park.

- dict (say)–dictate, diction. Dictate the letter you want to send, and I’ll write it.

- doc (teach)–document, doctrine. Please read this document before you make a decision.

- gen (birth)–generation. There are 3 generations in her home, the grandparents, the parents, and the kids.

- jur (law) jury–On no! I just got a summons for jury duty.

- lev (lift)–elevate, elevator. Take the elevator to the 5th floor.

- luc, lum (light)–translucent, illuminate. You can see some light through something translucent.

- manu (hand)–manicure, manual. A construction worker does manual labor.

- mis, mit (send)–transmit. You can transmit your message several ways.

- pac (peace)–pacifist. A pacifist does not believe in war.

- port (carry)–portable, export. A laptop is a portable computer.

- scrib, scrip (write)–script, describe. Please describe your hometown.

- sens (feel)–sensitive. She is sensitive, as her feelings are easily hurt.

- terr (earth)–territory, terrestrial. A wolf has a huge territory in the wild.

- tim (fear)–timid. A timid person is fearful and shy.

- vac (empty)–vacuum, evacuate. Please evacuate the building when you hear the fire alarm.

- vid, vis (see)–video, vision. He has poor vision, so he needs glasses.

You now know that English has many words borrowed from other languages. In fact, most English words are borrowed from somewhere else. Many borrowed words are of Greek or Latin origin. A large number of these words have cognates in many languages. If you know what many of these common word parts mean, it will help your English vocabulary to grow. The download will give you additional practice using and understanding many of our borrowed words.

You can download the practice sheet now!

Idioms of the day

- to stop at nothing–This means to be willing to do anything to achieve success. Stephen will stop at nothing to win a large Christmas bonus.

- to law down the law–This means to strongly assert your authority. After Charlie got into his fifth car accident, his parents laid down the law. No more driving!

The larger part of English

vocabulary consists of loan words. Borrowing is one of the ways of

enriching the vocabulary. Words can be borrowed through all kinds of

contacts between nations: wars, invasions, occupation, cultural and

trade relations between countries. It is natural, therefore, in

discussing the problem of loan words in any language to give a

survey of certain historical facts from the life of the people

speaking that language.

3.1. Latin borrowings

The

earliest borrowings came into English from Latin. In the 1st

century B.C. the Germanic tribes lived in Central Europe, they spoke

numerous Germanic languages which contained Indo-European and Common

Germanic elements. As most of Europe was occupied by the Roman Empire

at that time The Germanic tribes came into constant contacts with the

Romans. There were both military conflicts and trade relations. The

Germanic tribes were primitive cattle-breeders who knew next to

nothing about land cultivation. The only products known to them were

meat and milk. So, from the more civilized Romans they learnt how to

make butter and cheese. Since there were no words to name the new

foodstuffs in their tribal languages they had to use Latin words for

them. The Latin names of some fruits and vegetables new to the

Germanic tribes also entered their vocabulary: cherry,

pear, plum, pea, pepper, peach, beet. The

very word plant

is

also of Latin origin. Other Latin borrowings of this period are: cup,

dish, mill, kitchen, wine, mule, pound, inch, mile, kettle.

As Britain

was also part of the Roman Empire at that time, such words as street

(strata

via), wall

(vallum),

camp

(campus),

port

(portus),

chester

(as

in Manchester)

(castra) remaine in the language.

Historically,

all Latin loan words in English can be divided into 3 layers. The

borrowings described above belong to the

first layer.

The second

stream of Latin borrowings came into English with the

Christianization of the British Isles in the 7th

century A.D. The language of the Christian church was Latin and,

naturally,

the second layer

of Latin borrowings consists mostly of different religious terms:

pope,

bishop, monk, nun, priest, altar, devil, creed, angel, psalm, candle,

hymn, apostle, disciple. The

priests were educated people who began to establish church schools

and the words school,

master, verse, scholar, chalk came

into the language. Of words other than religious and educational

terms we may name such as lion,

copper, marble, gem, palm-tree, cap, spade, fork

(вилы).

The

third layer

of Latin borrowings refers to the epoch of Renaissance (in England it

came in the 16th

century, later than in Italy). This period was marked by the

prospering of art, science and culture in all European countries.

There also came a revival of interest in ancient civilizations of

Greece and Rome. The words that came into English during this period

differ greatly from earlier Latin borrowings. Now the borrowing was

done from literature and scientific works that were written in Latin

and the loan words, in contrast to the previous two layers, were

mostly abstract in meaning and many of them were scientific terms.

There were many verbs and adjectives among them and comparatively few

nouns: introduce,

execute, collect, decorate, senior, solar, triangular, evident,

cordial, obvious, union, relation, etc. The

words of the first and second layers were mostly nouns and the

borrowing was from oral everyday communication, not from written

sources.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #