New_etymology вопрошает: «Отойдя от отождествления слова ‘GIRL’ c детьми обоего пола, просите себя, что является первым признаком, отличающим мальчика от девочки, boy от girl?»

Ну и сам же, разумеется, дает ответ (кому интересно):

https://lengvizdika.livejournal.com/358368.html

Смешно?) Вот и я о том же) Не менее смешно (а может и более), нежели утверждение А. Драгункина, что girl — это горлица) Кстати, в основе у обоих то же самое «горло-жерло»)

А теперь проявим настоящую этимологию данного слова, учитывая, что оно было применимо не только (и не столько) к девочкам, но и в целом к детям, малышам! Это важно!

girl. c. 1300, gyrle «child, young person» (дети, юные персоны)

немецк. kerl «мальчик, малец»,

ср.-нем. karl «малыш»

КАРлики — это просто «КОРотышки», маленькие люди, малыши.

От КОРотить, КОРнать, соКРАщать, уКОРачивать, КОРоткий…

из той же основы, что и англ. shear (срезать), датск. skære (резать), японск. 切る kiru (резать), галисийск. cortar (резать)

англ. short (короткий)

англ. shorts (шорты, укороченные штаны, трусы)

англ. shorty (коротышка)

армян. կարճ karch (короткий)

датск. kort (короткий)

нем. kurz (короткий)

греч. ἀκαρής akaris (очень маленький)

польск. karzeł (карлик, малыш)

ирланд. gearr (короткий)

ирл. gearrtha (резать, срезать, сокращать, укорачивать)

н-.ненемецк. gære (мальчик, девочка)

норвежск. gorre (малыш)

шведск, gurre (маленький ребенок)

Вот и весь «секрет»)

Кстати:

Ещё момент, на который прошу обратить внимание!

КОЦать, отКУСывать, КОСить, КУСать…

Т.е. (опять же: срезать, сократить, сделать короче)

азерб. kəsmək (резать)

татар. кисү (резать)

казахск. кесу (резать)

турецк. kesmek (резать)

киргиз. кесүү (резать)

турецк. kısa (короткий)

узбекск. qisqa (короткий)

татарск. кыска (короткий)

азерб. qısa (короткий)

казахск. қысқа (короткий)

и (внимание):

казахск. қыз (девочка)

турецк. kız (девочка)

киргиз. кыз (девочка)

татарск. кыз (девочка)

т.е. точно та же схема, что и с «girl», но замешанная на иной этимологической основе!

Однако: и это ещё не всё!

Что такое РЕЗать? Это ведь не только сокращать, крошить, сечь, делить на части и пр. но и выРАЖать, делать РЕЗче, отчетливее, выРАЗительнее… кРАСивее!)

соответственно и слова имеющие точки пересечения с этой основой, пусть даже синонимичные, содержащие иные основы, могут быть связаны с РЕЗкостью в семантике выРАЗительности, яркости, кРАСоты:

смотр.:

ГУЗель (или ГЮЗель), значение имени «красавица»

«Гюзель отличается красивой внешностью, острым умом, быстрой реакцией и темпераментом»

казах. қыз (девочка) — в основе те же КУСать, КОСить (т.е. острота, резкость, резвость): энергичность, темперамент, острота, выРАЗительность, кРАСота, кРАСный, РЫЖий, РУДый, РЕЗкий, выРАЗительный

сравн.: қызар (покраснеть), қызару (воспалительный), қызған (разогретый), қызғана (ревновать), қыздыр (нагревать), қызба (темперамент), қызбалы (темпераментный), қызбалық (вспыльчивость)

Шохруххон — Киз бола

Вот как всё в этимологии тонко переплетается!

A girl is a young female human, usually a child or an adolescent. When a girl becomes an adult, she is accurately described as a woman. However, the term girl is also used for other meanings, including young woman,[1] and is sometimes used as a synonym for daughter,[2] or girlfriend.[citation needed] In certain contexts, the usage of girl for a woman may be derogatory. Girl may also be a term of endearment used by an adult, usually a woman, to designate adult female friends. Girl also appears in portmanteaus (compound words) like showgirl, cowgirl, and schoolgirl.

The treatment and status of girls in any society is usually closely related to the status of women in that culture. In cultures where women have a low societal position, girls may be unwanted by their parents, and the state may invest less in services for girls. Girls’ upbringing ranges from being relatively the same as that of boys to complete sex segregation and completely different gender roles.

Etymology

The English word girl first appeared during the Middle Ages between 1250 and 1300 CE and came from the Anglo-Saxon word gerle (also spelled girle or gurle).[3] The Anglo-Saxon word gerela meaning dress or clothing item also seems to have been used as a metonym in some sense.[1] Until the late 1400s, the word meant a child of either sex, and has meant ‘female child’ since about the late 1500s century.[4]

Usage for adult women

The word girl is sometimes used to refer to an adult female, usually a younger one. This usage may be considered derogatory or disrespectful in professional or other formal contexts, just as the term boy can be considered disparaging when applied to an adult man. Hence, this usage is often deprecative.[1] It can also be used depreciatively when used to discriminate against children (e.g., «you’re just a girl«). However, girl can also be a professional designation for a woman employed as a model or other public feminine representative such as a showgirl, and in such cases is not generally considered derogatory.

In a casual context, the word has positive uses, as evidenced by its use in titles of popular music. It has been used playfully for people acting in an energetic fashion (Canadian singer Nelly Furtado’s «Promiscuous Girl») or as a way of unifying women of all ages on the basis of their once having been girls (American country singer Martina McBride’s «This One’s for the Girls»).

History

The status of girls throughout world history is closely related to the status of women in any culture. Where women enjoy a more equal status with men, girls benefit from greater attention to their needs.

Girls’ education

Girls’ formal education has traditionally been considered far less important than that of boys. In Europe, exceptions were rare before the printing press and the Reformation made literacy more widespread. One notable exception to the general neglect of girls’ literacy is Queen Elizabeth I. In her case, as a child, she was in a precarious position as a possible heir to the throne, and her life was in fact endangered by the political scheming of other powerful members of the court. Following the execution of her mother, Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth was considered illegitimate. Her education was for the most part ignored by Henry VIII. Remarkably, Henry VIII’s widow, Catherine Parr, took an interest in the high intelligence of Elizabeth, and supported the decision to provide her with an impressive education after Henry’s death, starting when Elizabeth was 9.[5] Elizabeth received an education equal to that of a prominent male aristocrat; she was educated in Latin, Greek, Spanish, French, philosophy, history, mathematics and music. It has been argued that Elizabeth’s high-quality education helped her grow up to become a successful monarch.[6]

By the 18th century, Europeans recognized the value of literacy, and schools were opened to educate the public in growing numbers. Education in the Age of Enlightenment in France led to up to a third of women becoming literate by the time of the French Revolution, contrasting with roughly half of men by that time.[7] However, education was still not considered as important for girls as for boys, who were being trained for professions that remained closed to women, and girls were not admitted to secondary level schools in France until the late 19th century. Girls were not entitled to receive a Baccalaureate diploma in France until the reforms of 1924 under education minister Léon Bérard. Schools were segregated in France until the end of World War II. Since then, compulsory education laws have raised the education of girls and young women throughout Europe. In many European countries, girls’ education was restricted until the 1970s, especially at higher levels. This was often done by teaching different subjects to each sex, especially since tertiary education was considered primarily for males, particularly with regard to technical education. For example, prestigious engineering schools, such as École Polytechnique, did not allow women until the 1970s.[8]

«Coming of age» customs

Many cultures have traditional customs to mark the «coming of age» of a girl or boy, to recognize their transition to adulthood, or to mark other milestones of their journey to maturity as children.

Japan has a coming-of-age ritual called Shichi-Go-San (七五三), which literally means «Seven-Five-Three». This is a traditional rite of passage and festival day in Japan for three- and seven-year-old girls and three- and five-year-old boys, held annually on November 15. It is generally observed on the nearest weekend. On this day, the girl will be dressed in a traditional kimono, and will be taken to a temple by her family for a blessing ceremony. Nowadays, the occasion is also marked with a formal photo portrait.

Many coming-of-age ceremonies are to acknowledge the passing of a girl through puberty, when she experiences menarche, or her first menstruation. The traditional Apache coming-of-age ceremony for girls is called the na’ii’ees (Sunrise Ceremony), and takes place over four days. The girls are painted with clay and pollen, which they must not wash off until the end of the rituals, which involve dancing and rituals that challenge physical strength. Girls are given teaching in aspects of sexuality, confidence, and healing ability. The girls pray in the direction of the east at dawn, and in the four cardinal directions, which represent the four stages of life. This ceremony was banned by the U.S. government for many decades; after being decriminalized by the Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978, it has seen a revival.

[9]

Some coming-of-age ceremonies are religious rituals to recognize a girl’s maturity with respect to her understanding of religious beliefs, and to recognize her changing role in her religious community. Confirmation is a ceremony common to many Christian denominations for both boys and girls, usually taking place when the child is in their teen years. In Roman Catholic communities, Confirmation ceremonies are considered one of seven sacraments that a Catholic may receive during their life. In many countries, it is traditional for Catholics children to undergo another sacrament, First Communion, at the age of 7 years old. The sacrament is usually performed in a church once a year, with children who are of age receive a blessing from a Bishop in a special ceremony. It is traditional in many countries for Catholic girls to wear white dresses and possibly a small veil or wreath of flowers in their hair to their First Communion. The white dress symbolizes spiritual purity.

A traditional coming-of-age ritual for daughters of college age (17 to 21 years old) from high society and well-connected upper-class and White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) families in North America and Europe has historically been their debut at a debutante ball, such as the International Debutante Ball in New York City. Traditionally, debutantes wear couture white gowns and gloves symbolising purity and wealth.

Across Latin America, the fiesta de quince años is a celebration of a girl’s fifteenth birthday. The girl celebrating the birthday is called a Quinceañera. This birthday is celebrated differently from any other birthday, as it marks the transition from childhood to young womanhood.[10]

Preparing girls for marriage

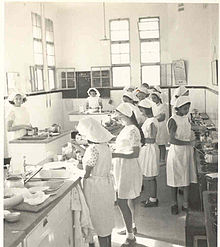

Cooking class at a girls’ school in Jerusalem, c. 1936. Girls’ upbringing and education were traditionally focused on preparing them to be future wives.

In many ancient societies, girls’ upbringing had much to do with preparing them to be future wives. In many cultures, it was not the norm for women to be economically independent. Thus, where a girl’s future well-being depended upon marrying her to a man who was economically self-sufficient, it was crucial to prepare her to meet whatever qualities or skills were popularly expected of wives.

Western society

In cultures ranging from Ancient Greece to the 19th-century United States, girls have been taught such essential domestic skills as sewing, cooking, gardening, and basic hygiene and medical care such as preparing balms and salves, and in some cases midwife skills. These skills would be taught from generation to generation, with the knowledge passed down orally from mother to daughter. A well-known reference to these important women’s skills is in the folk tale Rumpelstiltskin, which dates back to Medieval Germany and was collected in written form by the folklorists the Brothers Grimm. The miller’s daughter is valued as a potential wife because of her reputation for being able to spin straw into gold.

China

In some parts of China, beginning in the Southern Tang kingdom in Nanjing (937-975),[11] the custom of foot binding was associated with upper-class women who were worthy of a life of leisure, and husbands who could afford to spare them the necessity of work (which would require the ability to be mobile and spend the day on their feet).[11] Because of this belief, parents hoping to ensure a good marriage for their daughters would begin binding their feet from about the age of 5–8 to achieve the ideal appearance.[11] The tinier the feet, the better the social rank of a future husband.[11] This practice did not end until the early years of the 20th century.[11]

China has had many customs tied to girls and their roles as future wives and mothers. According to one custom, a girl’s way of wearing her hair would indicate her marital status. An unmarried girl would wear her hair in two «pigtails», and once married, she would wear her hair in one.[12]

Africa

In some cultures, girls’ passing through puberty is viewed with concern for a girl’s chastity. In some communities, there is a traditional belief that female genital mutilation is a necessity to prevent a girl from becoming sexually promiscuous. The practice is dangerous, however, and leads to long-term health problems for women who have undergone it. The practice has been a custom in 28 countries of Africa, and persists mainly in rural areas. This coming-of-age custom, sometimes incorrectly described as «female circumcision», is being outlawed by governments, and challenged by human rights groups and other concerned community members, who are working to end the practice.

Trafficking and trading girls

The Pashtun population has a tradition of trading girls in solving disputes.

Girls have been used historically, and are still used in some parts of the world, in settlements of disputes between families, through practices such as baad, swara, or vani. In such situations, a girl from a criminal’s family is given to the victim’s family as a servant or a bride. Another practice is that of selling girls in exchange for the bride price. The 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery defines «institutions and practices similar to slavery» to include:[13] c) Any institution or practice whereby: (i) A woman, without the right to refuse, is promised or given in marriage on payment of a consideration in money or in kind to her parents, guardian, family or any other person or group; or (ii) The husband of a woman, his family, or his clan, has the right to transfer her to another person for value received or otherwise; or (iii) A woman on the death of her husband is liable to be inherited by another person.

Demographics

China has an imbalanced sex ratio, a situation partly caused by the one child policy. Photo shows girls in 1982 in China.

World map of birth sex ratios, 2012

2011 Census sex ratio map for the states and Union Territories of India, boys per 100 girls in 0 to 1 age group.[14]

Scholars are unclear and in dispute as to possible causes for variations in human sex ratios at birth.[15][16] Countries which have sex ratios of 108 and above are usually presumed as engaging in sex selection. However, deviations in sex ratios at birth can occur for natural causes too. Nevertheless, the practice of bias against girls, through sex selective abortion, female infanticide, female abandonment, as well as favouring sons with regard to allocating of family resources[17] is well documented in parts of South Asia, East Asia, and the Caucasus. Such practices are a major concern in China, India and Pakistan. In these cultures, the low status of women creates a bias against females.[18]

China and India have a very strong son preference. In China, the one child policy was largely responsible for an unbalanced sex ratio. Sex-selective abortion, as well as rejection of girl children is common. The Dying Rooms is a 1995 television documentary film about Chinese state orphanages, which documented how parents abandoned their newborn girls into orphanages, where the staff would leave the children in rooms to die of thirst, or starvation. In India, the practice of dowry is partly responsible for a strong son preference.

Another manifestation of son preference is the violence inflicted against mothers who give birth to girls.[19][20][21]

In India, by 2011, there were 91 girls younger than 6 for every 100 boys. Its 2011 census showed[22] that the ratio of girls to boys under the age of 6 years old has dropped even during the past decade, from 927 girls for every 1000 boys in 2001 to 918 girls for every 1000 boys in 2011. In China, scholars[23] report 794 baby girls for every 1000 baby boys in rural regions. In Azerbaijan, last 20 years of birth data suggests 862 girls were born for every 1000 boys, on average every year.[24] Steven Mosher, president of the Population Research Institute in Washington, D.C. has said: «Twenty-five million men in China currently can’t find brides because there is a shortage of women […] young men emigrate overseas to find brides.» The gender imbalance in these regions is also blamed for spurring growth in the commercial sex trade; the UN’s 2005 report states that up to 800,000 people being trafficked across borders each year, and as many as 80 percent are women and girls.[25]

Biology

A girl with a doll, a traditionally female toy. Photo by Hermann Kapps

A victor of the Heraean Games, represented near the start of a race. Various cultures throughout history have had different ideas of acceptable activities for girls.

Embryos that inherit two X chromosomes (XX), one from each parent, are generally identified as girls when born.

About one in a thousand girls have a 47,XXX karyotype, and one in 2500 have a 45,X one.

Girls have a female reproductive system. Some intersex children with ambiguous genitals, as well as transgender children may also be classified or self-identify as girls.[26][27][28][page needed][better source needed]

Girls’ bodies undergo gradual changes during puberty. Puberty is the process of physical changes by which a child’s body matures into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction to enable fertilization. It is initiated by hormonal signals from the brain to the gonads. In response to the signals, the gonads produce hormones that stimulate libido and the growth, function, and transformation of the brain, bones, muscle, blood, skin, hair, breasts, and sexual organs. Physical growth—height and weight—accelerates in the first half of puberty and is completed when the child has developed an adult body. Until the maturation of their reproductive capabilities, the pre-pubertal, physical differences between boys and girls are the genitalia. Puberty is a process that usually takes place between 10 and 16 years, but these ages differ from person to person. The major landmark of female puberty is menarche, the onset of menstruation, which occurs on average between 12 and 13.[29][30] According to a 2010 Canadian study, the variation of age in which menstruation begins had a «statistically significant» relation to where the child was living, household income, and family type.[31]

Gender and environment

Rows of pink girls’ toys in a Canadian store, 2011. Biological sex interacts with environment in ways not fully understood in creating gender roles.

Biological sex interacts with environment in ways not fully understood.[32] Identical twin girls separated at birth and reunited decades later have shown both startling similarities and differences.[33] In 2005, professor Kim Wallen of Emory University noted, «I think the ‘nature versus nurture’ question is not meaningful, because it treats them as independent factors, whereas in fact everything is nature and nurture.»[34] Wallen said gender differences emerge very early and come about through an underlying preference males and females have for their chosen activities.

Femininity is a set of attributes, behaviours, and roles generally associated with girls and women. Femininity is socially constructed, but made up of both socially-defined and biologically created factors.[35][36][37] This makes it distinct from the definition of the biological female sex,[38][39] as both males and females can exhibit feminine traits. Traits traditionally cited as feminine include gentleness, empathy, and sensitivity,[40][41][42] though traits associated with femininity vary depending on location and context, and are influenced by a variety of social and cultural factors.[43]

Gender neutrality describes the idea that policies, language, and other social institutions should avoid distinguishing roles according to people’s sex or gender, in order to avoid discrimination arising from rigid gender roles. Unisex refers to things that are considered appropriate for any sex. Campaigns for unisex toys include Let Toys Be Toys.

Teenage pregnancy

Teenage pregnancy is pregnancy in an adolescent girl. A female can become pregnant from sexual intercourse after she has begun to ovulate. Pregnant teenagers face many of the same pregnancy related issues as other women. There are, however, additional concerns for young adolescents as they are less likely to be physically developed enough to sustain a healthy pregnancy or to give birth.[44][45][46]

In developed countries, teenage pregnancy is usually associated with social issues, including lower educational levels, poverty, and other negative life outcomes; and often carries a social stigma.[47] By contrast, teenage girls in developing countries are often married, and their pregnancies welcomed by family and society. However, in these societies, child marriage and early pregnancy often combine with malnutrition and poor health care and create medical problems.

Girls’ education

Girls’ equal access to education has been achieved in some countries, but there are significant disparities in the majority. There are gaps in access between different regions and countries and even within countries. Girls account for 60 per cent of children out of school in Arab countries and 66 per cent of non-attendees in South and West Asia; however, more girls than boys attend schools in many countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, North America and Western Europe.[48] Research has measured the economic cost of this inequality to developing countries: Plan International’s analysis shows that a total of 65 low, middle income and transition countries fail to offer girls the same secondary school opportunities as boys, and in total, these countries are missing out on annual economic growth of an estimated $92 billion.[48]

Although the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has asserted «primary education shall be compulsory and available free to all» girls are slightly less likely to be enrolled as students in primary and secondary schools (70%:74% and 59%:65%). Worldwide efforts have been made to end this disparity (such as through the Millennium Development Goals) and the gap has closed since 1990.[49]

Educational environment and expectations

According to Kim Wallen, expectations will nonetheless play a role in how girls perform academically. For example, if females skilled in math are told a test is «gender neutral» they achieve high scores, but if they are told males outperformed females in the past, the females will do much worse. «What’s strange is,» Wallen observed, «according to the research, all one apparently has to do is tell a woman who has a lifetime of socialization of being poor in math that a math test is gender neutral, and all effects of that socialization go away.»[51] Author Judith Harris has said that aside from their genetic contribution, the nurturing provided by parents likely has less long-term influence over their offspring than other environmental aspects such as the children’s peer group.[52]

In England, studies by the National Literacy Trust have shown girls score consistently higher than boys in all scholastic areas from the ages of 7 through 16, with the most striking differences noted in reading and writing skills.[53] In the United States, historically, girls lagged on standardized tests. In 1996 the average score of 503 for US girls from all races on the SAT verbal test was 4 points lower than boys. In math, the average for girls was 492, which was 35 points lower than boys. «When girls take the exact same courses,» commented Wayne Camara, a research scientist with the College Board, «that 35-point gap dissipates quite a bit.» At the time Leslie R. Wolfe, president of the Center for Women Policy Studies said girls scored differently on the math tests because they tend to work the problems out while boys use «test-taking tricks» such as immediately checking the answers already given in multiple-choice questions. Wolfe said girls are steady and thorough while «boys play this test like a pin-ball machine.» Wolfe also said although girls had lower SAT scores they consistently get higher grades than boys across all courses in their first year in college.[54] By 2006 girls were outscoring boys on the verbal portion of the United States’ nationwide SAT exam by 11 points.[55] A 2005 University of Chicago study showed that a majority presence of girls in the classroom tends to enhance the academic performance of boys.[56][57]

Obstacles to girls’ access to education

In many parts of the world, girls face significant obstacles to accessing proper education. These obstacles include: early and forced marriages; early pregnancy; prejudice based on gender stereotypes at home, at school and in the community; violence on the way to school, or in and around schools; long distances to schools; vulnerability to the HIV epidemic; school fees, which often lead to parents sending only their sons to school; lack of gender sensitive approaches and materials in classrooms.[58][59][60]

Sex segregation

Further information: Purdah

Sex segregation is the physical, legal, and cultural separation of people according to their biological sex. It is practiced in many societies, especially starting when children attain puberty. In certain circumstances, sex segregation is controversial.[61] Some critics contend that it is a violation of capabilities and human rights and can create economic inefficiencies and discrimination, while some supporters argue that it is central to certain religious laws and social and cultural histories and traditions.[62][63] Purdah is a religious and social practice of female seclusion prevalent among some Muslim and Hindu communities in South Asia.[64] It takes two forms: physical segregation of the sexes and the requirement that women cover almost entirely their bodies. The ages from which this practice is enforced vary by community. Such practices are most common in cultures where the concept of family honor is very strong. In cultures where sex segregation is common, the predominant form of education in single sex education.

Violence against girls

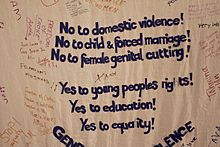

Millions of girls, some less than 1 year old, undergo ritual female genital mutilation (FGM) every year. This practice is found in parts of Africa,[65] some Middle East countries such as Iraq and Yemen,[66][67] Malaysia and Indonesia.[68][69] A worldwide campaign is underway to prevent FGM/C and other violence against girls.

In many parts of the world, girls are at risk of specific forms of violence and abuse, such as sex-selective abortion, female genital mutilation, child marriage, child sexual abuse, honor killings.

In parts of the world, especially in East Asia, South Asia and some Western countries’ girls are sometimes seen as unwanted; in some cases, girls are selectively aborted, abused, mistreated or abandoned by their parents or relatives.[70][71] In China, boys exceed girls by more than 30 million, suggesting over a million excess boys are born every year than expected for normal human sex ratio at birth.[23] In India, scholars[72] estimate from boy to girl ratio at birth that sex-selective abortions cause a loss of about 1.5%, or 100,000 female births per year. Abnormal boy to girl ratio at birth is also seen in Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia, suggesting possible sex-selective abortions against girls.[73]

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as «all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.»[74] It is practiced mainly in 28 countries in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, particularly Egypt and Ethiopia, and in parts of Southeast Asia and the Middle East.[75] FGM is most often carried out on girls aged between infancy and 15 years.[76]

Child marriages, where girls are married at young ages (often forced and often to much older husbands) remain common in many parts of the world. They are fairly widespread in parts of the world, especially in Africa,[77][78] South Asia,[79] Southeast and East Asia,[80][81] the Middle East,[82][83] Latin America,[84] and Oceania.[85] The ten countries with the highest rates of child marriage are: Niger, Chad, Central African Republic, Bangladesh, Guinea, Mozambique, Mali, Burkina Faso, South Sudan, and Malawi.[86]

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a form of child abuse in which an adult or older adolescent uses a child for sexual stimulation.[87][88] In Western countries CSA is considered a serious crime, but in many parts of the world there is a tacit tolerance of the practice. CSA can take many forms, one of which is child prostitution. Child prostitution is the commercial sexual exploitation of children in which a child performs the services of prostitution, for financial benefit. It is estimated that each year at least one million children, mostly girls, become prostitutes.[89] Child prostitution is common in many parts of the world, especially in Southeast Asia (Thailand, Cambodia), and many adults from wealthy countries travel to these regions to engage in child sex tourism.

In many parts of the world, girls who are deemed to have tarnished the ‘honor’ of their families by refusing arranged marriages, having premarital sex, dressing in ways deemed inappropriate or even becoming the victims of rape, are at risk of honor killing by their families.[90]

Health

Girls’ health suffers in cultures where girls are valued less than boys, and families allocate most resources to boys. A major threat to girls’ health is early marriage, which often leads to early pregnancy. Girls forced into child marriage often become pregnant quickly after marriage, increasing their risk of complications and maternal mortality. Such complications resulting from pregnancy and birth at young ages are a leading cause of death among teenage girls in developing countries.[91] Female genital mutilation (FGM) practiced in many parts of the world is another leading cause of ill health for girls.[92]

Girls and child labor

Gender influences the pattern of child labor. Girls tend to be asked by their families to perform more domestic work in their parental home than boys are, and often at younger ages than boys. Employment as a paid domestic worker is the most common form of child labor for girls. In some places, such as East and Southeast Asia, parents often see work as a domestic servant as a good preparation for marriage. Domestic service, however, is among the least regulated of all professions, and exposes workers to serious risks, such as violence, exploitation and abuse by the employers, because the workers are often isolated from the outside world. Child labor has a very negative effect on education. Girls either stop their education, or, when they continue it, they are often subjected to a double burden, or a triple burden of work outside the home, housework in the parental home, and schoolwork. This situation is common in places such as parts of Asia and Latin America.[93][94]

International initiatives for girls’ rights

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1988) and Millennium Development Goals (2000) promoted better access to education for all girls and boys and to eliminate gender disparities at both primary and secondary level. Worldwide school enrolment and literacy rates for girls have improved continuously. In 2005, global primary net enrolment rates were 85 per cent for girls, up from 78 per cent 15 years earlier; at the secondary level, girls’ enrolment increased 10 percentage points to 57 per cent over the same period.[48]

A number of international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have created programs focussing on addressing disparities in girls’ access to such necessities as food, healthcare and education. CAMFED is one organization active in providing education to girls in sub-Saharan Africa. PLAN International’s «Because I am a Girl» campaign is a high-profile example of such initiatives. PLAN’s research has shown that educating girls can have a powerful ripple effect, boosting the economies of their towns and villages; providing girls with access to education has also been demonstrated to improve community understanding of health matters, reducing HIV rates, improving nutritional awareness, reducing birthrates and improving infant health. Research demonstrates that a girl who has received an education will:

- Earn up to 25 percent more and reinvest 90 percent in her family.

- Be three times less likely to become HIV-positive.

- Have fewer, healthier children who are 40 percent more likely to live past the age of five.[95]

Plan International also created a campaign to establish an International Day of the Girl. The goals of this initiative are to raise global awareness of the unique challenges facing girls, as well as the key role they have in addressing larger poverty and development challenges. A delegation of girls from Plan Canada introduced the idea to Rona Ambrose, Canada’s Minister of Public Works and Government Services and Minister for Status of Women, at the 55th Session of the Commission on the Status of Women at United Nations Headquarters in February 2011. In March 2011, Canada’s Parliament unanimously adopted a motion requesting that Canada take the lead at the United Nations in the initiative to proclaim an International Day of the Girl.[96] The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted an International Day of the Girl Child on December 19, 2011. The first International Day of the Girl Child is October 11, 2012.

Its most recent research has led PLAN International to identify a need to coordinate projects that address boys’ roles in their communities, as well as finding ways of including boys in activities that reduce gender discrimination. Since political, religious and local community leaders are most often men, men and boys have great influence over any effort to improve girls’ lives and achieve gender equality. PLAN International’s 2011 Annual Report points out that men have more influence and may be able to convince communities to curb early marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM) more effectively than women. Egyptian religious leader Sheikh Saad, who has campaigned against the practice, is quoted in the report: “We have decided that our daughter will not go through this bad, inhumane experience […] I am part of the change.”[97]

Art and literature

Historically, art and literature in Western culture has portrayed girls as symbols of innocence, purity, virtue and hope. Egyptian murals included sympathetic portraits of young girls who were daughters of royalty. Sappho’s poetry carries love poems addressed to girls.

In Europe, some early paintings featuring girls were Petrus Christus’ Portrait of a Young Girl (about 1460), Juan de Flandes’ Portrait of a Young Girl (about 1505), Frans Hals’ Die Amme mit dem Kind in 1620, Diego Velázquez’ Las Meninas in 1656, Jan Steen’s The Feast of St. Nicolas (about 1660) and Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring along with Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. Later paintings of girls include Albert Anker’s portrait of a Girl with a Domino Tower and Camille Pissarro’s 1883 Portrait of a Felix Daughter.

Mary Cassatt painted many famous Impressionist works that idealize the innocence of girls and the mother-daughter bond, for example her 1884 work Children on the Beach. During the same era, Whistler’s Harmony in Gray and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander and The White Girl depict girls in the same light.

The European children’s literature canon includes many notable works with young female protagonists. Traditional fairy tales have preserved memorable stories about girls. Among these are Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Rapunzel, The Princess and the Pea and the Brothers Grimm’s Little Red Riding Hood. Well-known children’s books about girls include Heidi, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Nancy Drew series, Little House on the Prairie, Madeline, Pippi Longstocking, A Wrinkle in Time, Dragonsong, and Little Women.

Beginning in the late Victorian era, more nuanced depictions of girl protagonists became popular. Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl, The Little Mermaid, and other tales featured themes that ventured into tragedy. Published in 1865, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll featured a widely noted female protagonist, Alice, confronting eccentric characters and intellectual puzzles in surreal settings. The character of the plucky, yet proper, Alice has proven immensely popular and inspired similar heroines in literature and pop culture.[98] Literature followed different cultural currents, sometimes romanticizing and idealizing girlhood, and at other times developing under the influence of the growing literary realism movement. Many Victorian novels begin with the childhood of their heroine, such as Jane Eyre, an orphan who suffers ill treatment from her guardians and then at a girls’ boarding school. The character Natasha in War and Peace, on the other hand, is sentimentalized.

By the 20th century, the portrayal of girls in fiction had for the most part abandoned idealized portrayals of girls. Popular literary novels include Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird in which a young girl, Scout, is faced with the awareness of the forces of bigotry in her community. Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial book Lolita (1955) is about a doomed relationship between a 12-year-old girl and an adult scholar as they travel across the United States. Zazie dans le métro (Zazie in the Metro) (1959) by Raymond Queneau is a popular French novel that humorously celebrates the innocence and precocity of Zazie, who ventures off on her own to explore Paris, escaping from her uncle (a professional female impersonator) and her mother (who is preoccupied by a meeting with her lover). Zazie was also made into a popular movie in 1960 (Zazie dans le Métro) by French director Louis Malle.

Books which have both boy and girl protagonists have tended to focus more on the boys, but important girl characters appear in Knight’s Castle, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Book of Three and the Harry Potter series.

Recent novels with an adult audience have included reflections on girlhood experiences. Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden begins as the female main character and her sister are dropped off in the pleasure district after being separated from their family in 19th-century Japan. Snow Flower and the Secret Fan by Lisa See traces the laotong (old sames) bond of friendship between a pair of childhood friends in modern Beijing, and the parallel friendship of their ancestors in 19th-century Hunan, China.

-

-

The Salona Girl, marble head from city of Salona, 3rd century AD (archaeological museum, Zagreb)

Popular culture

There have been many comic books and comic strips featuring a girl as the main character such as Little Lulu and Little Orphan Annie from the US, and Minnie the Minx from the UK. In superhero comic books an early girl character was Etta Candy, one of Wonder Woman’s sidekicks. In the Peanuts series (by Charles Schulz) girl characters include Peppermint Patty, Lucy van Pelt and Sally Brown.

In Japanese animated cartoons and comic books girls are often protagonists. Most of Hayao Miyazaki’s animated films feature a young girl heroine, as in Majo no takkyūbin (Kiki’s Delivery Service). There are many other girl protagonists in the shōjo style of manga, which is targeted at girls as an audience. Among these are The Wallflower, Ceres, Celestial Legend, Tokyo Mew Mew and Full Moon o Sagashite. Meanwhile, some genres of Japanese cartoons may feature sexualized and objectified portrayals of girls.

The term girl is widely heard in the lyrics of popular music (such as with the song «About a Girl»), most often meaning a young adult or teenaged female.

See also

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Girls.

Look up girl in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Female infanticide

- Girl group

- Tomboy

- Woman

- Shōjo

References

- ^ a b c Dictionary.com, «Girl». Retrieved January 2, 2008.

- ^ «Girl — Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary». Merriam-webster.com. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary (1913), girl Archived 2009-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary, girl, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ The childhood and education of Elizabeth I (Radio Broadcast). August 30, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-11-16.

- ^ Briscoe, Alexandra (2011-02-17). «BBC — History — Elizabeth I: An Overview». BBC. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ Melton, James Van Horn. (2001). The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ «1958 to today». www.polytechnique.edu. 2017. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ Paul L. Allen (2001-07-26). «Coming of age: Apache twins Fayreen and Farren Holden are welcomed into adulthood in a four-day tribal ceremony». Tucson Citizen. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ «Fifteen Questions on the Quinceañera». United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- ^ a b c d e Cartwright, M. (2017). Foot-Binding — World History Encyclopedia. [online] worldhistory.org. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Foot-Binding/ [Accessed APril 15, 2022].

- ^ Perkins, Dorothy (2000). Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. New York, NY: Checkmark Books.

- ^ «Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery». Ohchr.org. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Age Data C13 Table (India/States/UTs ) Final Population — 2011 Census of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (2013)

- ^ James W.H. (July 2008), «Hypothesis:Evidence that Mammalian Sex Ratios at birth are partially controlled by parental hormonal levels around the time of conception», Journal of Endocrinology 198 (1), pp 3–15

- ^ France MESLÉ; Jacques VALLIN; Irina BADURASHVILI (2007). A Sharp Increase in Sex Ratio at Birth in the Caucasus. Why? How? (PDF). Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography. pp. 73–89. ISBN 978-2-910053-29-1.

- ^ Son Preference

- ^ Jones & 1999-2000.

- ^ Afghan woman is killed ‘for giving birth to a girl’ — BBC News

- ^ 23-year-old woman killed for giving birth to twin daughters | Bareilly News — Times of India

- ^ 56 killed for giving birth to girl child in Pakistan

- ^ CHILD SEX RATIO IN INDIA Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine Dr C Chandramouli, Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India (2011)

- ^ a b Wei Xing Zhu, Li Lu, Therese Hesketh, China’s Excess Males, Sex Selective Abortion, and One Child Policy: Analysis of Data from 2005 National Intercensus Survey, BMJ: British Medical Journal, Vol. 338, No. 7700 (Apr. 18, 2009), pp. 920-923

- ^ «Gender Statistics Highlights from 2012 World Development Report». World DataBank, a compilation of databases by the World Bank. February 2012.

- ^ Karabin, Sherry (13 June 2007). «Infanticide, Abortion Responsible for 60 Million Girls Missing in Asia». Fox News. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ «Transgender Children & Youth: Understanding the Basics». Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 2022-10-01.

- ^ «What’s intersex?». Planned Parenthood. 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2022-10-01.

- ^ Ethics And Intersex Sharon E. Sytsma

- ^ (Tanner, 1990).

- ^ Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A (April 2003). «Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart». Pediatrics. 111 (4 Pt 1): 844–50. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.844. PMID 12671122.

- ^ Al-Sahab B, Ardern CI, Hamadeh MJ, Tamim H (2010). «Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth». BMC Public Health. 10: 736. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736. PMC 3001737. PMID 21110899.

- ^ Salon.com, Kurt Kleiner, A mind of their own Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine (book review of Nature via Nurture by Matt Ridley), 19 June 2003, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ BBC, Jane Beresford, Twins reunited, after 35 years apart, 31 December 2007, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ «The Academic Exchange». 2011-06-29. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ Marianne van den Wijngaard (1997). Reinventing the sexes: the biomedical construction of femininity and masculinity. Race, gender, and science. Indiana University Press. pp. 171 pages. ISBN 978-0-253-21087-6. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Hale Martin, Stephen Edward Finn (2010). Masculinity and Femininity in the MMPI-2 and MMPI-A. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 310 pages. ISBN 978-0-8166-2445-4. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Richard Dunphy (2000). Sexual politics: an introduction. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 240 pages. ISBN 978-0-7486-1247-5. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Ferrante, Joan (2010-01-01). Sociology: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 269–272. ISBN 978-0-8400-3204-1.

- ‘^ Gender, Women and Health: What do we mean by «sex» and «gender»? The World Health Organization

- ^ Vetterling-Braggin, Mary «Femininity,» «masculinity,» and «androgyny»: a modern philosophical discussion

- ^ Worell, Judith, Encyclopedia of women and gender: sex similarities and differences and the impact of society on gender, Volume 1 Elsevier, 2001, ISBN 0-12-227246-3, ISBN 978-0-12-227246-2

- ^ Thomas, R. Murray (2000). Recent Theories of Human Development. SAGE Publications. p. 248. ISBN 978-0761922476.

Gender feminists also consider traditional feminine traits (gentleness, modesty, humility, sacrifice, supportiveness, empathy, compassion, tenderness, nurturance, intuitiveness, sensitivity, unselfishness) morally superior to the traditional masculine traits of courage, strong will, ambition, independence, assertiveness, initiative, rationality and emotional control.

- ^ Witt, Charlotte, ed. (2010). Feminist Metaphysics: Explorations in the Ontology of Sex, Gender and Identity. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 77. ISBN 978-90-481-3782-4.

- ^ Mayor S (2004). «Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries». BMJ. 328 (7449): 1152. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1152-a. PMC 411126. PMID 15142897.

- ^ Loto OM, Ezechi OC, Kalu BK, Loto A, Ezechi L, Ogunniyi SO (2004). «Poor obstetric performance of teenagers: Is it age- or quality of care-related?». Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 24 (4): 395–398. doi:10.1080/01443610410001685529. PMID 15203579. S2CID 43808921.

- ^ Abalkhail BA (1995). «Adolescent pregnancy: Are there biological barriers for pregnancy outcomes?». The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association. 70 (5–6): 609–625. PMID 17214178.

- ^ «Young mothers face stigma and abuse, say charities». BBC News. 25 February 2014.

- ^ a b c «Paying the Price: The economic cost of failing to educate girls» (PDF). PLAN International. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ The State of the World’s Children 2004 — Girls, Education and Development Archived 2018-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, UNICEF, 2004

- ^ Peer, Basharat (10 October 2012), «The Girl Who Wanted To Go To School», The New Yorker

- ^ Emory University website, Women’s work? Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, September 2005, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ PBS.org, Nature vs. nurture Archived 2014-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, 20 October 1998, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ literacytrust.org, Literacy achievement in England, including gender split Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, 2007, retrieved 7 December 2008

- ^ New York Times,

Katherine Q Seelye, Group Seeks to Alter S.A.T. to Raise Girls’ Scores, 14 March 1997, retrieved 2 January 2008 - ^ ABC News, John Berman, Girls Achieve Rare SAT Scores, 30 August 2006, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ harrisschool.uchicago.edu, Girl-Dominated Classrooms Can Improve Boys’ Early School Performance Archived 2007-08-19 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 January 2008

- ^ «India baby girl deaths ‘increase’«. BBC News. 21 June 2008.

- ^ «Global issues affecting women and girls | National Union of Teachers — NUT». Teachers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ «Global Campaign For Education United States Chapter». Campaignforeducationusa.org. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ «Because I am a Girl». Plan-international.org. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Salomone, Rosemary C. «Are Single-Sex Schools Inherently Unequal? Same, Different, Equal: Rethinking Single-Sex Schooling.» «Michigan Law Review.» 102(6):1219-1244

- ^ The World Bank. 2012. «Gender Equality and Development: World Development Report 2012.» Washington, D.C: The World Bank.

- ^ Nussbaum, Martha C. 2003. «Women’s Education: A Global Challenge.» «Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society» 29(2): 325–355

- ^ Wilkinson-Weber, Clare M. (25 March 1999). Embroidering Lives: Women’s Work and Skill in the Lucknow Embroidery Industry. SUNY Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780791440889.

Purdah regulates the interactions of women with certain kinds of men. Typically, Hindu women must avoid specific male affines (in-laws) and Muslim women are restricted from contact with men outside the family, or at least their contact with these men is highly circumscribed (Papanek 1982:3). In practice, many elements of both «Hindu» and «Muslim» purdah are shared by women of both groups in South Asia (Vatuk 1982; Jeffery 1979), and Hindu and Muslim women both adopt similar strategies of self-effacement, like covering the face, keeping silent, and looking down, when in the company of persons to be avoided.

- ^ Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine UNICEF, (July 2013)

- ^ FGM — Where is it practiced? European Campaign on FGM & Amnesty International (2012)

- ^ Tackling Female Genital Mutilation in the Kurdistan Region Sofia Barbarani, The Kurdistan Tribune (March 4, 2013)

- ^ World Health Organization, Female genital mutilation: an overview. 1998, Geneva: World Health Organization

- ^ William G. Clarence-Smith (2012) ‘Female Circumcision in Southeast Asia since the Coming of Islam’, in Chitra Raghavan and James P. Levine (eds.), Self-Determination and Women’s Rights in Muslim Societies, Brandeis University Press; ISBN 978-1611682809; see pages 124-146

- ^ Goodkind, Daniel (1999). «Should Prenatal Sex Selection be Restricted?: Ethical Questions and Their Implications for Research and Policy». Population Studies. 53 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/00324720308069. JSTOR 2584811.

- ^ A. Gettis, J. Getis, and J. D. Fellmann (2004). Introduction to Geography, Ninth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 200. ISBN 0-07-252183-X

- ^ Arnold, Fred, Kishor, Sunita, & Roy, T. K. (2002). «Sex-Selective Abortions in India». Population and Development Review. 28 (4): 759–785. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00759.x. JSTOR 3092788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ France MESLÉ; Jacques VALLIN; Irina BADURASHVILI (2007). A Sharp Increase in Sex Ratio at Birth in the Caucasus. Why? How?. Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography. pp. 73–89. ISBN 978-2-910053-29-1.

- ^ «Female genital mutilation», World Health Organization, February 2013.

- ^ «An update on WHO’s work on female genital mutilation (FGM)», World Health Organization, 2011, p. 2: «Most women who have experienced FGM live in one of the 28 countries in Africa and the Middle East – nearly half of them in just two countries: Egypt and Ethiopia. Countries in which FGM has been documented include: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania and Yemen. The prevalence of FGM ranges from 0.6% to 98% of the female population.»

- Rahman, Anika and Toubia, Nahid. Female Genital Mutilation: A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide. Zed Books, 2000 (hereafter Rahman and Toubia 2000), p. 7: «Currently, FC/FGM is practiced in 28 African countries in the sub-Saharan and North-eastern regions.»

- Also see «Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation», World Health Organization, 2008, p. 4: «Types I, II and III female genital mutilation have been documented in 28 countries in Africa and in a few countries in Asia and the Middle East.»

- ^ «WHO | Female genital mutilation». Who.int. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Child brides die young ANTHONY KAMBA, Africa in Fact Journal (1 AUGUST 2013)

- ^ Marrying too young, End child marriage United Nations Population Fund (2012), See page 23

- ^ Early Marriage, Child Spouses UNICEF, See section on Asia, page 4 (2001)

- ^ Southeast Asia’s big dilemma: what to do about child marriage? Archived 2013-10-03 at the Wayback Machine August 20, 2013

- ^ PHILIPPINES: Early marriage puts girls at risk IRIN, United Nations News Service (January 26, 2010)

- ^ «How Come You Allow Little Girls to Get Married?» — Child Marriage in Yemen Human Rights Watch, (2011); pages 15-23

- ^ Child marriage still an issue in Saudi Arabia Joel Brinkley, San Francisco Chronicle (March 14, 2010)

- ^ Child Marriage — What we know? Public Broadcasting Service (United States), 2010

- ^ Early Marriage, Child Spouses UNICEF, See section on Oceania, page 5

- ^ WHO | Child marriages: 39,000 every day. Who.int (2013-03-07). Retrieved on 2013-04-06.

- ^ «Child Sexual Abuse». Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2008-04-02.

- ^ «Guidelines for psychological evaluations in child protection matters. Committee on Professional Practice and Standards, APA Board of Professional Affairs». The American Psychologist. 54 (8): 586–93. August 1999. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.586. PMID 10453704.

Abuse, sexual (child): generally defined as contacts between a child and an adult or other person significantly older or in a position of power or control over the child, where the child is being used for sexual stimulation of the adult or other person.

- ^ «Child Trafficking and Prostitution» (PDF). Globalfunsforchildren.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-07. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ «Ethics — Honour crimes». BBC. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Child marriage | UNFPA — United Nations Population Fund

- ^ Female genital mutilation

- ^ «Child labour : Are girls affected differently from boys» (PDF). Unicef.org. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ «Counting Cinderellas». Paa2009.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ «CAMFED USA: What we do». CAMFED. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ «Canada Calls on Member States to Proclaim International Day of the Girl (News Release October 11, 2011)». Status of Women Canada. Archived from the original on October 31, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ «‘Because I am a Girl’ group finds boys matter, too». Toronto Star. 17 September 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ «The Guardian view on Alice in Wonderland: a dauntless, no-nonsense heroine». The Guardian. 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- Abkhaz: аҧҳəызба (apḥəəzba), аӡӷаб (adzğab)

- Adyghe: пшъашъэ (pŝaaŝe)

- Afar: awka

- Afrikaans: meisie (af)

- Aklanon: deaga

- Albanian: vajzë (sq), çikë (sq) f, gocë (sq) f, cucë (sq) f, voce (sq) f

- Aleut: asxinux, ayaĝaadax̂

- Alutor: ljaŋi

- Alviri-Vidari:

- Vidari: کنگ (kaneg)

- Amharic: ሴት ልጅ f (set ləǧ), ልጃገረድ (ləǧagäräd)

- Arabic: بِنْت f (bint), فَتَاة f (fatāh), طِفْلة f (ṭifla) (child)

- Egyptian Arabic: بنت f (bent)

- Moroccan Arabic: بنت f (bent), درية f (derreya)

- Armenian: աղջիկ (hy) (ałǰik)

- Aromanian: featã

- Assamese: ছোৱালী (süali)

- Asturian: neña (ast) f, ñena f

- Avar: яс (jas)

- Azerbaijani: qız (az)

- Baluchi: جنک (jinik, janik)

- Bashkir: ҡыҙ (qıð)

- Basque: neska (eu)

- Bavarian: Dirndl, Mädl, Madli, Deandl, Meudl

- Belarusian: дзяўчы́на f (dzjaŭčýna), дзяўча́ f (dzjaŭčá) (child), дзяўчы́нка f (dzjaŭčýnka) (child)

- Bengali: মেয়ে (bn) (meẏoe)

- Breton: plac’h (br) f

- Budukh: риж (riž)

- Bulgarian: момиче́ (bg) n (momičé), дево́йка (bg) f (devójka), мома́ (bg) f (momá), моми́ченце n (momíčence) (child), дево́йче n (devójče) (child)

- Burmese: သူငယ်မ (my) (su-ngaima.), မိန်းကလေး (my) (min:ka.le:), ကောင်မလေး (my) (kaungma.le:) (little girl)

- Buryat: басаган (basagan)

- Catalan: noia (ca) f, nena (ca) f (little girl), xiqueta (ca), al·lota (ca) f

- Central Franconian: Mädsche

- Central Siberian Yupik: neveghsaq

- Central Sierra Miwok: kolí-

- Chechen: йоӏ (jọ)

- Cherokee: (adolescent) ᎠᏔᏄᏣ (atanutsa)

- Chickasaw: chipota tiik

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 女仔 (neoi5 zai2), 細路女/细路女 (sai3 lou6 neoi5-2) (child)

- Dungan: нүзы (nüzɨ), гўнён (gwni͡on), ятур (i͡atur), нүвазы (nüvazɨ)

- Hakka: 細妹仔/细妹仔 (se-moi-é)

- Mandarin: 女孩兒/女孩儿 (zh) (nǚháir), 女孩子 (zh) (nǚháizi), 姑娘 (zh) (gūniang), 女兒/女儿 (zh) (nǚ’ér), 丫頭/丫头 (zh) (yātou) (colloquial, deprecating or endearing)

- Min Nan: 查某囡仔 (zh-min-nan) (cha-bó͘ gín-á)

- Wu: 囡兒/囡儿 (noe hhngg)

- Chiricahua: ’it’éeké, jeekȩ́n

- Chukchi: ӈээккэӄэй (ṇėėkkėqėj)

- Cimbrian: diirna f

- Coptic:

- Bohairic: ϣⲉⲣⲓ f (šeri)

- Sahidic: ϣⲉⲉⲣⲉ f (šeere)

- Crimean Tatar: qız

- Czech: holka (cs) f, děvče (cs) n, dívka (cs) f, holčička (cs) f (child)

- Danish: pige (da) c

- Darkinjung: mirkan

- Dolgan: кыыс

- Dutch: meisje (nl) n, meid (nl) f, meidje (nl) n, griet (nl) f, grietje (nl) n, maagd (nl) f (dated)

- Egyptian: (zꜣt f), (šrjt f)

- Elfdalian: kulla f

- Erza: тейтерь (ťejťeŕ)

- Eshtehardi: تیتی f (titiya)

- Esperanto: knabino (eo)

- Estonian: tüdruk (et), plika (et)

- Even: асаткан (asatkan)

- Evenki: асаткан (asatkan), хунат (hunat)

- Ewe: nyɔnuvi

- Faroese: genta (fo) f

- Finnish: tyttö (fi)

- French: fille (fr) f, jeune fille (fr) f

- Friulian: frute f, frutate f

- Galician: nena (gl) f, meniña (gl) f, moza f, rapaza f, rapariga f

- Georgian: გოგო (ka) (gogo), გოგონა (gogona)

- German: Mädchen (de) n, (regional) Mädel (de) n, Magd (de) f (dated), Wicht (de) (archaic, dialectal)

- Alemannic German: Goof f, Maidle, Maitli, Meitle, Meidschi, Modi, Meetle, Meitji, Moadle, Meiki

- East Central German: Madel (Silesian), Mädel (Silesian)

- Gothic: 𐌼𐌰𐌲𐌰𐌸𐍃 f (magaþs), 𐌼𐌰𐍅𐌹 f (mawi), 𐌼𐌰𐍅𐌹𐌻𐍉 f (mawilō)

- Greek: κορίτσι (el) n (korítsi)

- Ancient: κόρη f (kórē), κοράσιον n (korásion)

- Greenlandic: niviarsiaq

- Guaraní: kuñataĩ, mitãkuña

- Hausa: yarinya

- Hawaiian: kaikamahine (child), wahine ʻōpio (young woman)

- Hebrew: יַלְדָּה f (yaldá) (child), נַעֲרָה (he) f (na’ará) (teens or twenties)

- Hiligaynon: babaye (of any age), dalaga (adolescent or older and unmarried)

- Hindi: लड़की (hi) f (laṛkī)

- Hiri Motu: kekeni

- Hungarian: lány (hu)

- Icelandic: stúlka (is) f, stelpa (is) f (informal), telpa (is) f (informal, dated)

- Ido: yunino (io), puerino (io)

- Indonesian: (please verify) anak perempuan, (please verify) gadis (id)

- Ingrian: tyttö

- Ingush: йоӏ (jọ)

- Interlingua: puera (child), pupa

- Inupiaq: niaqsaaʁruk

- Irish: cailín (ga) m

- Italian: bambina (it) f (child), ragazza (it) f (adolescent)

- Japanese: 女の子 (ja) (おんなのこ, onna no ko), 少女 (ja) (しょうじょ, shōjo), 女子 (ja) (じょし, joshi), 乙女 (ja) (おとめ, otome)

- Jicarilla: ch’eekéé

- Kabyle: ⵜⴰⵇⵛⵉⵛⵜ (taqcict)

- Kalmyk: күүкн (küükn)

- Kamba: mwiitu

- Kashmiri: کوٗر (ks) (kūr), لٔڑکی (ks) (lạḍkī), کٔٹ (ks) (kạṭ)

- Kashubian: dzéwczã n

- Kazakh: қыз (kk) (qyz)

- Khmer: ក្មេងស្រី (kmeeng srəy)

- Khoekhoe: ǀgôas

- Kikuyu: karĩgũ class 12 (uncircumcised and small), karĩĩgũ class 12 (uncircumcised and small), kĩrĩgũ class 7 (uncircumcised teenager), mũirĩtu class 1 (circumcised), mũirĩĩtu class 1 (circumcised)

- Koch Rajbangsi: চেংৰী (ceṅri)

- Korean: 소녀(少女) (ko) (sonyeo), 여자(女子)아이 (ko) (yeojaai), 녀자(女子)아이 (nyeojaai) (North Korea)

- Krio: titi

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: کچ (ckb) (kiç)

- Northern Kurdish: keç (ku)

- Kyrgyz: кыз (ky) (kız)

- Ladin: muta f

- Lao: ເດັກຍິງ (dek nying)

- Latgalian: meitine f, mārga f

- Latin: puella (la) f, pura f, puera f, adolescens f

- Latvian: meitene f, meiča f (colloquial), skuķis m (colloquial), skuķe f (colloquial)

- Lezgi: руш (ruš)

- Lithuanian: mergina f, mergaitė f

- Livonian: neitški

- Lombard: tósa f, tusa f

- Louisiana Creole French: fiy

- Luganda: omuwala

- Luo: nyathina

- Luxembourgish: Meedchen (lb) n

- Macedonian: чупе n (čupe), девојка f (devojka), девојче n (devojče) (child)

- Malagasy: tovovavy (mg)

- Malay: gadis

- Malayalam: പെൺകുട്ടി (peṇkuṭṭi)

- Maltese: tfajla f

- Manchu: ᡤᡝᡤᡝ (gege)

- Maori: taitamāhine, kōhine (young woman), hine, kōtiro, kōhaia, tamahine (mi)

- Marathi: मुल्गी f (mulgī)

- Maricopa: mshhay

- Mazanderani: کیجا

- Meru: mwari

- Mingrelian: ძღაბი (ʒɣabi), ცირა (cira)

- Mizo: hmeichhe naupang, nula

- Mohawk: eksà:ʼa

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: охин (mn) (oxin)

- Motu: kekeni

- Mwani: mwari

- Mòcheno: diarn f

- Naga Pidgin: chokri

- Navajo: atʼééd

- Neapolitan: peccerella f, nenna f

- Nepali: केटी (ne) (keṭī)

- Norman: hardelle f (Jersey)

- North Frisian: (Föhr-Amrum) foomen f

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: jente (no) m or f, pike (no) m

- Nynorsk: jente f, jenta f

- O’odham: cehia

- Occitan: dròlla (oc) f, drolleta f (child), gojata (oc) f (teens or twenties), filha (oc) f

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: дѣва f (děva), дѣвица f (děvica)

- Old English: mæġden n

- Old Prussian: mērgā

- Oromo: dubara

- Ossetian: чызг (ḱyzg)

- Ottoman Turkish: بنت (bint), دختر (duhter), قیز (kız)

- Pali: kaññā f

- Pashto: نجلۍ (ps) f (nǰələi), ووړکۍ f (worrkəi)

- Persian: دختر (fa) (doxtar)

- Plautdietsch: Mejal f, Mäakjen n

- Polish: dziewczyna (pl) f, dziewczę (pl) f (formally), dziewa (pl) f (archaic), dziewczynka (pl) f (child), dziołcha (pl), dziewoja (pl), dziewczę (pl), dziewka (pl), dzieweczka (pl) f

- Portuguese: garota (pt), menina (pt) (child), moça (pt) (youngster), rapariga (pt) (Portugal)

- Punjabi: ਕੁੜੀ (pa) (kuṛī)

- Quechua: taski

- Rhine Franconian: Maadche

- Romani: ćhaj f (Romani), rakli f (non-Romani)

- Kalo Finnish Romani: tšai f (Romani), rakli f (non-Romani)

- Vlax Romani: ćhej f (Romani), rakli f (non-Romani)

- Romanian: fată (ro) f, copilă (ro) f (child)

- Russian: де́вушка (ru) f (dévuška), де́вочка (ru) f (dévočka) (child), девчо́нка (ru) f (devčónka), деви́ца (ru) f (devíca)

- Rusyn: дівча f (divča)

- Sami:

- Inari: nieidâ

- Northern: nieida

- Skolt: nijdd

- Southern: nïejte

- Samoan: teine (sm)

- Sanskrit: बाला (sa) f (bālā), कन्या (sa) f (kanyā)

- Scots: lassie

- Scottish Gaelic: caileag (gd) f (child), nighean (gd) f (child, adolescent), nighneag (gd), nìonag (gd) f (child)

- Seraiki: چُھوہِر (skr) f (chūhir)

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: дѐво̄јка f, дјѐво̄јка f

- Roman: dèvōjka (sh) f, djèvōjka (sh) f

- Sidamo: seemo

- Sirenik: náẋserráẋ

- Slovak: dievča (sk) n, dievčatko n (child)

- Slovene: dekle (sl) n, deklica f (child)

- Somali: inan

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: źowćo n

- Upper Sorbian: dźowćo n

- Spanish: niña (es) f (child), muchacha (es) f (teens or twenties), chica (es) f (teens or twenties), (Chile) cabra (es) f, (Mexico) chamaca (es) f, (Spain, Chile, Argentina) lola (es) f, (Argentina) nena (es) f, (Chile) chiquilla (es) f

- Sumerian: 𒆠𒂖 (KI.SIKIL)

- Svan: დინა (dina)

- Swabian: Mädle, Fehl, Fohl, Boscha

- Swahili: msichana (sw), mwari (sw)

- Swedish: flicka (sv) c, tjej (sv) c, jänta (sv) c, tös (sv) c

- Sylheti: ꠙꠥꠞꠤ (furi), ꠍꠥꠞꠉꠤ (súrogi)

- Tagalog: babae (tl) (of any age), batang babae (child), dalaga (adolescent or older and unmarried)

- Tajik: духтар (tg) (duxtar)

- Talysh:

- Asalemi: کله (kəla)

- Tamil: சிறுமி (ta) (ciṟumi), பெண் (ta) (peṇ)

- Taos: upę̀yu’úna

- Tatar: кыз (tt) (qız)

- Telugu: అమ్మాయి (te) (ammāyi), కన్య (te) (kanya), బాలిక (te) (bālika), పిల్ల (te) (pilla)

- Thai: เด็กผู้หญิง (th) (dèk-pûu-yǐng), เด็กหญิง (th) (dèk-yǐng), เด็กสาว (dèk-sǎao)

- Tibetan: བུ་མོ (bu mo)

- Tupinambá: kunhãta’ĩ (child), kunhãmuku (adolescent)

- Turkish: kız (tr)

- Turkmen: gyz

- Tuvan: уруг (urug), кыс (kıs)

- Tzotzil: tseb

- Udmurt: нылмурт (nylmurt)

- Ugaritic: 𐎔𐎙𐎚 (pġt)

- Ukrainian: ді́вчина (uk) f (dívčyna), ді́вчинка f (dívčynka) (child), дівча́ n (divčá) (child), дівча́тко n (divčátko) (child)

- Urdu: لڑکی f (laṛkī)

- Uyghur: قىز (qiz)

- Uzbek: qiz (uz)

- Venetian: tóxa f, toxata f

- Veps: neičukaine, neižne

- Vietnamese: cô gái (vi), con gái (vi), gái (vi)

- Vilamovian: miöed

- Volapük: jicil (vo)

- Walloon: båshele (wa) f, feye (wa) f

- Welsh: bachgennes f, geneth (cy) f

- West Frisian: famke (fy) n, faam (fy) c

- Western Apache: at’eedn, at’een, it’eedn, it’een, it’éédn, it’één, (-na’ilį’) na’ilín, (collective) it’ídé, at’eedn

- Wiradhuri: migay

- Yakut: кыыс (kııs)

- Yiddish: מיידל n or f (meydl)

- Yucatec Maya: chʼúupal

- Yup’ik: neviarcaq

- Yámana: čule-kipa

- Zazaki: kena

What is the origin of the word girl?

The English word girl first appeared during the Middle Ages between 1250 and 1300 CE and came from the Anglo-Saxon word gerle (also spelled girle or gurle). Girl has meant any young unmarried woman since about 1530. Its first noted meaning for sweetheart is 1648.

When was the word girl invented?

13th century

When did girl mean child?

Where does the word girl come from? The word girl, meaning “a female child,” originally meant any “child” or “young person,” regardless of gender. Girl, for “child,” is recorded around 1250–1300.

What is the root meaning of girl?

girl (n.) c. 1300, gyrle “child, young person” (of either sex but most frequently of females), of unknown origin. Girl does not go back to any Old English or Old Germanic form. It is part of a large group of Germanic words whose root begins with a g or k and ends in r.

What is it called when a girl dressed like a boy?

Transvestism is the practice of dressing in a manner traditionally associated with the opposite sex. In some cultures, transvestism is practiced for religious, traditional, or ceremonial reasons.

Can you turn into a girl without surgery?

Many transgender people transition without using hormones or surgery. Nonmedical options include: Living as your gender identity. This includes changing your clothing, name, speech or other things.

Can a girl be a simp?

A simp, by definition, is someone who does way too much for someone they like. That’s the Urban Dictionary top definition. It never specifies a gender, but everyone knows simp is used exclusively to describe men, and men’s behaviour towards women.

What does Simping stand for?

Urban Dictionary defines a simp as “someone who does way too much for a person they like”. This behavior, known as simping, is carried out by both men and women toward a variety of targets of both genders, including celebrities, politicians, e-girls, and e-boys.

- 12 лет назад

Меня спросили:

«Английское слово «girl» («девушка») изначально предназначалось для описания молодых людей обоего пола. Только в начале 16-го века термин начал использоваться конкретно для женского пола.» Правда ли это?

Что поведает нам Dictionary.com :

1250-1300 — в среднеанглийском для обозначения ребенка, молодого человека или девушки в ходу были слова gurle, girle, gerle; сравним с древнеанглийским gyrela/gi(e)rela — некий элемент одежды, который носили только молодые (девушки и юноши), потом видимо произошел метонимический перенос значения с «элемента одежды», на того кто его носил.

И еще немного о термине girl: также как взрослые мужчины (mature men) и даже молодые мужчины (young men) не любят, когда из называют мальчиками (boys), женщины (adult women) могут почувствовать себя оскорбленными, если их назовут girls/gals(более разговорный вариант). Раньше про секретаршу можно было сказать girl/my girl (I’ll have my girl look it up and call you back), группу женщин назвать girls, а незамужнюю даму a bachelor girl, но сейчас такое уже не допускается.