Asked by: Miss Virginia Hoppe

Score: 4.1/5

(73 votes)

It is built by joining two stems, one of which is simple, the other is derived. The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words. Derived words are those composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes.

How are English words constructed?

At the basic level, words are made of «morphemes.» These are the smallest units of meaning: roots and affixes (prefixes and suffixes). … In contrast, derivation makes a word with a clearly different meaning: such as «unhappy» or «happiness», both from «happy». The «un-» and «-ness» are derivational morphemes.

How are words built and formed?

Many words are built using a combination of linguistic elements, such as prefixes, suffixes, and combining forms. Whereas prefixes and suffixes adjust the sense of a word or its word class, combining forms differ by contributing to the particular meaning of that word.

How are new words added to the English language?

A word gets into a dictionary when it is used by many people who all agree that it means the same thing. … First, you drop the word into your conversation and writing, then others pick it up; the more its use spreads, the more likely it will be noticed by dictionary editors, or lexicographers.

How are words combined?

A portmanteau is a word that is formed by combining two different terms to create a new entity. Through blending the sounds and meanings of two existing words, a portmanteau creates a new expression that is a linguistic blend of the two individual terms.

23 related questions found

What two words hold the most letters?

Mailbox also called as Letter Box or Mail Slot is used to receive incoming posts or mails usually placed at a business place or a private residential place while Post Box contains the outgoing letters.

Why do I combine words when I talk?

When stress responses are active, we can experience a wide range of abnormal actions, such as mixing up our words when speaking. Many anxious and overly stressed people experience mixing up their words when speaking. Because this is just another symptom of anxiety and/or stress, it needn’t be a need for concern.

Is YEET a word?

Yeet is an exclamation that can be used for excitement, approval, surprise, or to show all-around energy. … Although yeet is an interjection (think Yes! or Score!), it also became a dance term that gained popularity in 2014 thanks to Black social media culture, which gave it momentum.

What words are being removed from the dictionary 2020?

These words may be removed from some dictionaries

- Aerodrome.

- Alienism.

- Bever.

- Brabble.

- Charabanc.

- Deliciate.

- Frigorific.

- Supererogate.

What is the longest word in the English dictionary 2021?

The longest word in any of the major English language dictionaries is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, a word that refers to a lung disease contracted from the inhalation of very fine silica particles, specifically from a volcano; medically, it is the same as silicosis.

Is Auto a combining form?

Other definitions for auto (2 of 5)

a combining form meaning “self,” “same,” “spontaneous,” used in the formation of compound words: autograph, autodidact. Also especially before a vowel, aut- .

Do all words have a combining form?

No, the combining form is putting together several word elements to form a variety of terms. A combining vowel is a vowel the help with pronunciation of the word. Do all words require a prefix? No, not every term will have a prefix.

Is an example of a combining form?

A combining form is a form of a word that only appears as part of another word. … For example, para- is a combining form in the word paratrooper because in that word it represents the word parachute. Para- is a prefix, however, in the words paranormal and paramedic.

What was the first word on earth?

Also according to Wiki answers,the first word ever uttered was “Aa,” which meant “Hey!” This was said by an australopithecine in Ethiopia more than a million years ago.

What is the oldest word in the English language?

Mother, bark and spit are just three of 23 words that researchers believe date back 15,000 years, making them the oldest known words.

What are the new words in the dictionary 2020?

5 new words you shouldn’t miss in 2020

- Climate Emergency. Let’s begin our list with The Oxford Dictionary Word of The Year – climate emergency. …

- Permaculture. Permaculture is an old word that’s recently become more popular. …

- Freegan. A freegan is also a portmanteau that combines the words free and vegan. …

- Hothouse. …

- Hellacious.

What is the shortest word in the dictionary?

Answer: Eunoia, at six letters long, is the shortest word in the English language that contains all five main vowels. Seven letter words with this property include adoulie, douleia, eucosia, eulogia, eunomia, eutopia, miaoued, moineau, sequoia, and suoidea. acobdarfq and 3 more users found this answer helpful.

Do dictionaries have every word?

Dictionaries do not contain all the words

Perhaps because they tend to be rather large books there is frequently an assumption that most dictionaries contain all the words in the language. … There has never been, and never will be, a dictionary that includes all the words in English.

What does YEET mean?

Yeet: an exclamation of enthusiasm, approval, triumph, pleasure, joy, etc.

Is YEET a word Scrabble?

Is YEET a Scrabble word? YEET is not a valid scrabble word.

What is a YEET baby?

— A Chesterfield baby and her uncle have become viral sensations, entertaining millions of people on TikTok and Instagram. … So much so, Marleigh is now affectionately called «The Yeet Baby» and can be found on Tik Tok and Instagram under that handle.

What is it called when you mix up words when speaking?

This is known as stuttering. You may speak fast and jam words together, or say «uh» often. This is called cluttering. These changes in speech sounds are called disfluencies.

Why do I forget words when speaking?

Aphasia is a communication disorder that makes it hard to use words. It can affect your speech, writing, and ability to understand language. Aphasia results from damage or injury to language parts of the brain. It’s more common in older adults, particularly those who have had a stroke.

What is it called when you forget words?

Lethologica is both the forgetting of a word and the trace of that word we know is somewhere in our memory.

Chapter 5 how english words are made. word-building1

Before turning to the various processes of making words, it would be useful to analyse the related problem of the composition of words, i. e. of their constituent parts.

If viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units which are called morphemes. Morphemes do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of words. Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots (or radicals} and affixes. The latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word (as in re-read, mis-pronounce, un-well) and suffixes which follow the root (as in teach-er, cur-able, diet-ate).

Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building known as affixation (or derivation).

Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary. Successfully competing with this structural type is the so-called root word which has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier borrowings (house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and, in Modern English, has been greatly enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion (e. g. to hand, v. formed from the noun hand; to can, v. from can, п.; to pale, v. from pale, adj.; a find, n. from to find, v.; etc.).

Another wide-spread word-structure is a compound word consisting of two or more stems2 (e. g. dining-room, bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing). Words of this structural type are produced by the word-building process called composition.

The somewhat odd-looking words like flu, pram, lab, M. P., V-day, H-bomb are called shortenings, contractions or curtailed words and are produced by the way of word-building called shortening (contraction).

The four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word-building.

To return to the question posed by the title of this chapter, of how words are made, let us try and get a more detailed picture of each of the major types of Modern English word-building and, also, of some minor types.

Affixation

The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this procedure is Very important and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the main types of affixes.

From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some Native Suffixes1

|

Noun-forming |

-er |

worker, miner, teacher, painter, etc. |

|

-ness |

coldness, loneliness, loveliness, etc. |

|

|

-ing |

feeling, meaning, singing, reading, etc. |

|

|

-dom |

freedom, wisdom, kingdom, etc. |

|

|

-hood |

childhood, manhood, motherhood, etc. |

|

|

-ship |

friendship, companionship, mastership, etc. |

|

|

-th |

length, breadth, health, truth, etc. |

|

|

Adjective-forming |

-ful |

careful, joyful, wonderful, sinful, skilful, etc. |

|

-less |

careless, sleepless, cloudless, senseless, etc. |

|

|

-y |

cozy, tidy, merry, snowy, showy, etc. |

|

|

-ish |

English, Spanish, reddish, childish, etc. |

|

|

-ly |

lonely, lovely, ugly, likely, lordly, etc. |

|

|

-en |

wooden, woollen, silken, golden, etc. |

|

|

-some |

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc. |

|

|

Verb-forming |

-en |

widen, redden, darken, sadden, etc. |

|

Adverb-forming |

-ly |

warmly, hardly, simply, carefully, coldly, etc. |

Borrowed affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English vocabulary (Ch. 3). It would be wrong, though, to suppose that affixes are borrowed in the same way and for the same reasons as words. An affix of foreign origin can be regarded as borrowed only after it has begun an independent and active life in the recipient language, that is, is taking part in the word-making processes of that language. This can only occur when the total of words with this affix is so great in the recipient language as to affect the native speakers’ subconscious to the extent that they no longer realize its foreign flavour and accept it as their own.

* * *

Affixes can also be classified into productive and non-productive types. By productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonce-words, i. e. words coined and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually formed on the level of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive patterns in word-building. When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an unputdownable thriller, we will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in dictionaries, for it is a nonce-Word coined on the current pattern of Modern English and is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming borrowed suffix -able and the native prefix un-.

Consider, for example, the following:

Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish, dispeptic-lookingish cove with an eye like a haddock.

(From Right-Ho, Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse)

The adjectives thinnish and baldish bring to mind dozens of other adjectives made with the same suffix; oldish, youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish, yellowish, etc. But dispeptic-lookingish is the author’s creation aimed at a humorous effect, and, at the same time, proving beyond doubt that the suffix -ish is a live and active one.

The same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: «I don’t like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish». (Mondayish is certainly a nonce-word.)

One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are quite & number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no longer used in word-derivation (e. g. the adjective-forming native suffixes -ful, -ly; the adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant, -ent, -al which are quite frequent).

Some Productive Affixes

|

Noun-forming suffixes |

-er, -ing, -ness, -ism1 (materialism), -ist1 (impressionist), -ance |

|

Adjective-forming suffixes |

-y, -ish, -ed (learned), -able, -less |

|

Adverb-forming suffixes |

-ly |

|

Verb-forming suffixes |

-ize/-ise (realize), -ate |

|

Prefixes |

un(unhappy), re(reconstruct), dis (disappoint) |

Note. Examples are given only for the affixes which are not listed in the tables at p. 82 and p. 83.

Some Non-Productive Affixes

|

Noun-forming suffixes |

-th,-hood |

|

Adjective-forming suffixes |

-ly, -some, -en, -ous |

|

Verb-forming suffix |

-en |

Note. The native noun-forming suffixes -dom and -ship ceased to be productive centuries ago. Yet, Professor I. V. Arnold in The English Word gives some examples of comparatively new formations with the suffix -dom: boredom, serfdom, slavedom [15]. The same is true about -ship (e. gsalesmanship). The adjective-forming -ish, which leaves no doubt as to its productivity nowadays, has comparatively recently regained it, after having been non-productive for many centuries.

Semantics of Affixes

The morpheme, and therefore affix, which is a type of morpheme, is generally defined as the smallest indivisible component of the word possessing a meaning of its own. Meanings of affixes are specific and considerably differ from those of root morphemes. Affixes have widely generalized meanings and refer the concept conveyed by the whole word to a certain category, which is vast and all-embracing. So, the noun-forming suffix -er could be roughly defined as designating persons from the object of their occupation or labour (painter — the one who paints) or from their place of origin or abode {southerner — the one living in the South). The adjective-forming suffix -ful has the meaning of «full of», «characterized by» (beautiful, careful) whereas -ish Olay often imply insufficiency of quality (greenish — green, but not quite; youngish — not quite young but looking it).

Such examples might lead one to the somewhat hasty conclusion that the meaning of a derived word is always a sum of the meanings of its morphemes: un/eat/able =» «not fit to eat» where not stands for unand fit for: -able.

There are numerous derived words whose meanings can really be easily deduced from the meanings of their constituent parts. Yet, such cases represent only the first and simplest stage of semantic readjustment with in derived words. The constituent morphemes within derivatives do not always preserve their current meanings and are open to subtle and complicated semantic shifts.

Let us take at random some of the adjectives formed with the same productive suffix -y, and try to deduce the meaning of the suffix from their dictionary definitions:

brainy (inform.) — intelligent, intellectual, i. e, characterized by brains

catty — quietly or slyly malicious, spiteful, i. e, characterized by features ascribed to a cat

chatty — given to chat, inclined to chat

dressy (inform.) — showy in dress, i. e. inclined to dress well or to be overdressed

fishy (e. g. in a fishy story, inform.) — improbable, hard to believe (like stories told by fishermen)

foxy — foxlike, cunning or crafty, i. e. characterized by features ascribed to a fox

stagy — theatrical, unnatural, i. e. inclined to affectation, to unnatural theatrical manners

touchy — apt to take offence on slight provocation, i. e. resenting a touch or contact (not at all inclined to be touched)1

The Random-House Dictionary defines the meaning of the -y suffix as «characterized by or inclined to the substance or action of the root to which the affix is attached». [46] Yet, even the few given examples show that, on the one hand, there are cases, like touchy or fishy that are not covered by the definition. On the other hand, even those cases that are roughly covered, show a wide variety of subtle shades of meaning. It is not only the suffix that adds its own meaning to the meaning of the root, but the suffix is, in its turn, affected by the root and undergoes certain semantic changes, so that the mutual influence of root and affix creates a wide range of subtle nuances.

But is the suffix -y probably exceptional in this respect? It is sufficient to examine further examples to see that other affixes also offer an interesting variety of semantic shades. Compare, for instance, the meanings of adjective-forming suffixes in each of these groups of adjectives.

1. eatable (fit or good to eat)2

lovable (worthy of loving)

questionable (open to doubt, to question)

imaginable (capable of being imagined)

2. lovely (charming, beautiful, i. e. inspiring love)

lonely (solitary, without company; lone; the meaning of the suffix does not seem to add anything to that of the root)

friendly (characteristic of or befitting a friend.)

heavenly (resembling or befitting heaven; beautiful, splendid)

3. childish (resembling or befitting a child)

tallish (rather tall, but not quite, i. e. approaching the quality of big size)

girlish (like a girl, but, often, in a bad imitation of one)

bookish (1) given or devoted to reading or study;

(2) more acquainted with books than with real life, i. e. possessing the quality of bookish learning)

The semantic distinctions of words produced from the same root by means of different affixes are also of considerable interest, both for language studies and research work. Compare: womanly — womanish, flowery — flowered -— flowering, starry — starred, reddened — reddish, shortened — shortish.

The semantic difference between the members of these groups is very obvious: the meanings of the suffixes are so distinct that they colour the whole words.

Womanly is used in a complimentary manner about girls and women, whereas womanish is used to indicate an effeminate man and certainly implies criticism.

Flowery is applied to speech or a style (cf. with the R. цветистый), flowered means «decorated with a patters of flowers» (e. g. flowered silk or chintz, cf. with the R, цветастый) and flowering is the same as blossoming (e. g. flowering bushes or shrubs, cf. with the R. цветущий).

Starry means «resembling stars» (e. g. starry eyes) and starred — «covered or decorated with stars» (e. g. starred skies).

Reddened and shortened both imply the result of an action or process, as in the eyes reddened with weeping or a shortened version of a story (i. e. a story that has been abridged) whereas shortish and reddish point to insufficiency of quality: reddish is not exactly red, but tinged with red, and a shortish man is probably a little taller than a man described as short.

Conversion

When in a book-review a book is referred to as a splendid read, is read to be regarded as a verb or a noun? What part of speech is room in the sentence: I was to room with another girl called Jessie. If a character in a novel is spoken about as one who had to be satisfied with the role of a has-been, what is this odd-looking has-been, a verb or a noun? One must admit that it has quite a verbal appearance, but why, then, is it preceded by the article?

Why is the word if used in the plural form in the popular proverb: If ifs and ans were pots and pans? (an = if, dial., arch.)

This type of questions naturally arise when one deals with words produced by conversion, one of the most productive ways of modern English word-building.

Conversion is sometimes referred to as an affixless way of word-building or even affixless derivation. Saying that, however, is saying very little because there are other types of word-building in which new words are also formed without affixes (most compounds, contracted words, sound-imitation words, etc.).

Conversion consists in making a new word from some existing word by changing the category of a part of speech, the morphemic shape of the original word remaining unchanged. The new word has a meaning Which differs from that of the original one though it can more or less be easily associated with it. It has also a new paradigm peculiar to its new category as a part of speech.

The question of conversion has, for a long time, been a controversial one in several aspects. The very essence of this process has been treated by a number of scholars (e. g. H. Sweet), not as a word-building act, but as a mere functional change. From this point of view the word hand in Hand me that book is not a verb, but a noun used in a verbal syntactical function, that is, hand (me) and hands (in She has small hands) are not two different words but one. Hence, the case cannot be treated as one of word-formation for no new word appears.

According to this functional approach, conversion may be regarded as a specific feature of the English categories of parts of speech, which are supposed to be able to break through the rigid borderlines dividing one category from another thus enriching the process of communication not by the creation of new words but through the sheer flexibility of the syntactic structures.

Nowadays this theory finds increasingly fewer supporters, and conversion is universally accepted as one of the major ways of enriching English vocabulary with new words. One of the major arguments for this approach to conversion is the semantic change that regularly accompanies each instance of conversion. Normally, a word changes its syntactic function without any shift in lexical meaning. E. g. both in yellow leaves and in The leaves were turning yellow the adjective denotes colour. Yet, in The leaves yellowed the converted unit no longer denotes colour, but the process of changing colour, so that there is an essential change in meaning.

The change of meaning is even more obvious in such pairs as hand > to hand, face > to face, to go > a go, to make > a make, etc.

The other argument is the regularity and completeness with which converted units develop a paradigm of their new category of part of speech. As soon as it has crossed the category borderline, the new word automatically acquires all the properties of the new category, so that if it has entered the verb category, it is now regularly used in all the forms of tense and it also develops the forms of the participle and the gerund. Such regularity can hardly be regarded as indicating a mere functional change which might be expected to bear more occasional characteristics. The completeness of the paradigms in new conversion formations seems to be a decisive argument proving that here we are dealing with new words and not with mere functional variants. The data of the more reputable modern English dictionaries confirm this point of view: they all present converted pairs as homonyms, i. e. as two words, thus supporting the thesis that conversion is a word-building process.

Conversion is not only a highly productive but also a particularly English way of word-building. Its immense productivity is considerably encouraged by certain features of the English language in its modern Stage of development. The analytical structure of Modern English greatly facilitates processes of making words of one category of parts of speech from words of another. So does the simplicity of paradigms of En-lush parts of speech. A great number of one-syllable Words is another factor in favour of conversion, for such words are naturally more mobile and flexible than polysyllables.

Conversion is a convenient and «easy» way of enriching the vocabulary with new words. It is certainly an advantage to have two (or more) words where there Was one, all of them fixed on the same structural and semantic base.

The high productivity of conversion finds its reflection in speech where numerous occasional cases of conversion can be found, which are not registered by dictionaries and which occur momentarily, through the immediate need of the situation. «If anybody oranges me again tonight, I’ll knock his face off, says the annoyed hero of a story by O’Henry when a shop-assistant offers him oranges (for the tenth time in one night) instead of peaches for which he is looking («Lit. tie Speck in Garnered Fruit»). One is not likely to find the verb to orange in any dictionary, but in this situation it answers the need for brevity, expressiveness and humour.

The very first example, which opens the section on conversion in this chapter (the book is a splendid read), though taken from a book-review, is a nonce-word, which may be used by reviewers now and then or in informal verbal communication, but has not yet found its way into the universally acknowledged English vocabulary.

Such examples as these show that conversion is a vital and developing process that penetrates contemporary speech as well. Subconsciously every English speaker realizes the immense potentiality of making a word into another part of speech when the need arises.

* * *

One should guard against thinking that every case of noun and verb (verb and adjective, adjective and noun, etc.) with the same morphemic shape results from conversion. There are numerous pairs of words (e. g. love, n. — to love, v.; work, n. — to work, v.; drink, n. — to drink, v., etc.) which did, not occur due to conversion but coincided as a result of certain historical processes (dropping of endings, simplification of stems) when before that they had different forms (e. g. O. E. lufu, n. — lufian, v.). On the other hand, it is quite true that the first cases of conversion (which were registered in the 14th c.) imitated such pairs of words as love, n. — to love, v. for they were numerous to the vocabulary and were subconsciously accepted by native speakers as one of the typical language patterns.

* * *

The two categories of parts of speech especially affected by conversion are nouns and verbs. Verbs made from nouns are the most numerous amongst the words produced by conversion: e. g. to hand, to back, to face, to eye, to mouth, to nose, to dog, to wolf, to monkey, to can, to coal, to stage, to screen, to room, to floor, to ^lack-mail, to blacklist, to honeymoon, and very many ethers.

Nouns are frequently made from verbs: do (e. g. This ifs the queerest do I’ve ever come across. Do — event, incident), go (e. g. He has still plenty of go at his age. Go — energy), make, run, find, catch, cut, walk, worry, show, move, etc.

Verbs can also be made from adjectives: to pale, to yellow, to cool, to grey, to rough (e. g. We decided sq rough it in the tents as the weather was warm), etc.

Other parts of speech are not entirely unsusceptible to conversion as the following examples show: to down, to out (as in a newspaper heading Diplomatist Outed from Budapest), the ups and downs, the ins and outs, like, n. (as in the like of me and the like of you).

* * *

It was mentioned at the beginning of this section that a word made by conversion has a different meaning from that of the word from which it was made though the two meanings can be associated. There are Certain regularities in these associations which can be roughly classified. For instance, in the group of verbs made from nouns some of the regular semantic associations are as indicated in the following list:

I. The noun is the name of a tool or implement, the verb denotes an action performed by the tool: to hammer, to nail, to pin, to brush, to comb, to pencil.

II. The noun is the name of an animal, the verb denotes an action or aspect of behaviour considered typical of this animal: to dog, to wolf, to monkey, to ape, to fox, to rat. Yet, to fish does not mean «to behave like a fish» but «to try to catch fish». The same meaning of hunting activities is conveyed by the verb to whale and one of the meanings of to rat; the other is «to turn informer, squeal» (sl.).

III. The name of a part of the human body — an action performed by it: to hand, to leg (sl.), to eye, to elbow, to shoulder, to nose, to mouth. However, to face does not imply doing something by or even with one’s face but turning it in a certain direction. To back means either «to move backwards» or, in the figurative sense, «to support somebody or something».

IV. The name of a profession or occupation — an activity typical of it: to nurse, to cook, to maid, to groom.

V. The name of a place — the process of occupying» the place or of putting smth./smb. in it (to room, to house, to place, to table, to cage).

VI. The name of a container — the act of putting smth. within the container (to can, to bottle, to pocket).

VII. The name of a meal — the process of taking it (to lunch, to supper).

The suggested groups do not include all the great variety of verbs made from nouns by conversion. They just represent the most obvious cases and illustrate, convincingly enough, the great variety of semantic interrelations within so-called converted pairs and the complex nature of the logical associations which specify them.

In actual fact, these associations are not only complex but sometimes perplexing. It would seem that if you know that the verb formed from the name of an animal denotes behaviour typical of the animal, it would easy for you to guess the meaning of such a verb provided that you know the meaning of the noun. Yet, it is not always easy. Of course, the meaning of to fox is rather obvious being derived from the associated reputation of that animal for cunning: to fox means «to act cunningly or craftily». But what about to wolf? How is one to know which of the characteristics of the animal was picked by the speaker’s subconscious when this verb was produced? Ferocity? Loud and unpleasant fowling? The inclination to live in packs? Yet, as the Hollowing example shows, to wolf means «to eat greedily, voraciously»: Charlie went on wolfing the chocolate. (R. Dahl)

In the same way, from numerous characteristics of | be dog, only one was chosen for the verb to dog which is well illustrated by the following example:

And what of Charles? I pity any detective who would have to dog him through those twenty months.

(From The French Lieutenant’s Woman by J. Fowles)

(To dog — to follow or track like a dog, especially with hostile intent.)

The two verbs to ape and to monkey, which might be expected to mean more or less the same, have shared between themselves certain typical features of the same animal:

to ape — to imitate, mimic (e. g. He had always aped the gentleman in his clothes and manners. — J. Fowles);

to monkey — to fool, to act or play idly and foolishly. To monkey can also be used in the meaning «to imitate», but much rarer than to ape.

The following anecdote shows that the intricacies ex semantic associations in words made by conversion may prove somewhat bewildering even for some native-speakers, especially for children.

«Mother», said Johnny, «is it correct to say you ‘water a horse’ when he’s thirsty?»

«Yes, quite correct.»

«Then», (picking up a saucer) «I’m going to milk the cat.»

The joke is based on the child’s mistaken association of two apparently similar patterns: water, п. — to water, v.; milk, n. — to milk, v. But it turns out that the meanings of the two verbs arose from different associations: to water a horse means «to give him water», but to milk implies getting milk from an animal (e. g, to milk a cow).

Exercises

I. Consider your answers to the following.

1. What are the main ways of enriching the English vocabulary?

2. What are the principal productive ways of word-building in English?

3. What do we mean by derivation?

4. What is the difference between frequency and productivity of affixes? Why can’t one consider the noun-forming suffix -age, that is commonly met in many words (cabbage, village, marriage, etc.), a productive one?

5. Give examples of your own to show that affixes have meanings.

6. Look through Chapter 3 and say what languages served as the main sources of borrowed affixes. Illustrate your answer by examples.

7. Prove that the words a finger and to finger («to touch or handle with .the fingers») are two words and not the one word finger used either as a noun or as a verb.

8. What features of Modern English have produced the high productivity of conversion? и

9. Which categories of parts of speech are especially affected by conversion?

10. Prove that the pair of words love, n. and love, v. do not present a case of conversion.

II. The italicized words in the following jokes and extracts are formed by derivation. Write them out in two columns:

A. Those formed with the help of productive affixes.

B. Those formed with the help of non-productive affixes. Explain the etymology of each borrowed affix.

1. Willie was invited to a party, where refreshments were bountifully served.

«Won’t you have something more, Willie?» the hostess said.

«No, thank you,» replied Willie, with an expression of great satisfaction. «I’m full.»

«Well, then,» smiled the hostess, «put some delicious fruit and cakes in your pocket to eat on the way home.»

«No, thank you,» came the rather startling response of Willie, «they’re full too.»

2. The scene was a tiny wayside railway platform and the sun was going down behind the distant hills. It was a glorious sight. An intending passenger was chatting with one of the porters.

«Fine sight, the sun tipping the hills with gold,» said the poetic passenger.

«Yes,» reported the porter; «and to think that there was a time when I was often as lucky as them ‘ills.»

3. A lady who was a very uncertain driver stopped her car at traffic signals which were against her. As the green flashed on, her engine stalled, and when she restarted it the colour was again red. This flurried her so much that when green returned she again stalled her engine and the cars behind began to hoot. While she was waiting for the green the third time the constable on duty stepped across and with a smile said: «Those are the only colours, showing today, ma’am.»

4. «You have an admirable cook, yet you are always growling about her to your friends.»

«Do you suppose I want her lured away?»

5. Patient: Do you extract teeth painlessly?

Dentist: Not always — the other day I nearly dislocated my wrist.

6. The inspector was paying a hurried visit to a slightly overcrowded school.

«Any abnormal children in your class?» he inquired of one harassed-looking teacher.

«Yes,» she replied, with knitted brow, «two of them have good manners.»

7. «I’d like you to come right over,» a man phoned an undertaker, «and supervise the burial of my poor, departed wife.»

«Your wife!» gasped the undertaker. «Didn’t I bury her two years ago?»

«You don’t understand,» said the man. «You see I married again.»

«Oh,» said the undertaker. «Congratulations.»

8. Dear Daddy-Long-Legs.

Please forget about that dreadful letter I sent you last week — I was feeling terribly lonely and miserable and sore-throaty the night I wrote. I didn’t know it, but I was just coming down with tonsillitis and grippe …I’m |b the infirmary now, and have been for six days. The Head nurse is very bossy. She is tall and thinnish with a Hark face and the funniest smile. This is the first time they would let me sit up and have a pen or a pencil. please forgive me for being impertinent and ungrateful.

Yours with love.

Judy Abbott

(From Daddy-Long-Legs by J. Webster)1

9. The residence of Mr. Peter Pett, the well-known financier, on Riverside Drive, New York, is one of the leading eyesores of that breezy and expensive boulevard …Through the rich interior of this mansion Mr. Pett, its nominal proprietor, was wandering like a lost spirit. There was a look of exasperation on his usually patient face. He was afflicted by a sense of the pathos of his position. It was not as if he demanded much from life. At that moment all that he wanted was a quiet spot where he might read his Sunday paper in solitary peace and he could not find one. Intruders lurked behind every door. The place was congested. This sort of thing had been growing worse and worse ever since his marriage two years previously. Marriage had certainly complicated life for Mr. Pett, as it does for the man who waits fifty years before trying it. There was a strong literary virus in Mrs. Pett’s system. She not only wrote voluminously herself — but aimed at maintaining a salon… She gave shelter beneath her terra-cotta roof to no fewer than six young unrecognized geniuses. Six brilliant youths, mostly novelists who had not yet started…

(From Piccadilly Jim by P. G. Wodehouse. Abridged)

III. Write out from any five pages of the book you are reading examples which illustrate borrowed and native affixes in the tables in Ch. 3 and 5. Comment on their productivity.

IV. Explain the etymology and productivity of the affixes given below. Say what parts of speech can be formed with their help.

-ness, -ous, -ly, -y, -dom, -ish, -tion, -ed, -en, -ess, -or, -er, -hood, -less, -ate, -ing, -al, -ful, un-, re-, im (in)-, dis-, over-, ab

V. Write out from the book yon are reading all the words with the adjective-forming suffix -ly and not less than 20 words with the homonymous adverb-forming suffix. Say what these suffixes have in common and in what way they are differentiated.

VI. Deduce the meanings of the following derivatives from the meanings of their constituents. Explain your deduction. What are the meanings of the affixes in the words under examination?

Reddish, ad].; overwrite, v.; irregular, adj.; illegals adj.; retype, v.; old-womanish, adj.; disrespectable, adj.; inexpensive, adj.; unladylike, adj.; disorganize, v.; renew, u.; eatable, adj.; overdress, u.; disinfection, п.; snobbish, adj.; handful, п.; tallish, adj.; sandy, adj.; breakable, adj.; underfed, adj.

VII. In the following examples the italicized words are formed from the same root by means of different affixes. Translate these derivatives into Russian and explain the Difference in meaning.

1. a) Sallie is the most amusing person in the world — and Julia Pendleton the least so. b) Ann was wary, but amused. 2. a) He had a charming smile, almost womanish in sweetness, b) I have kept up with you through Miss Pittypat but she gave me no information that you had developed womanly sweetness. 3. a) I have been having a delightful and entertaining conversation with my old chum, Lord Wisbeach. b) Thanks for your invitation. I’d be delighted to come. 4. a) Sally thinks everything is funny — even flunking — and Julia is bored at everything. She never makes the slightest effort to be pleasant, b) — Why are you going to America? — To make my fortune, I hope. — How pleased your father will be if you do. 5. a) Long before |he reached the brownstone house… the first fine careless rapture of his mad outbreak had passed from Jerry Mitchell, leaving nervous apprehension in its place. b) If your nephew has really succeeded in his experiments you should be awfully careful. 6. a) The trouble with college is that you are expected to know such a lot of things you’ve never learned. It’s very confusing at times. b) That platform was a confused mass of travellers, porters, baggage, trucks, boys with magazines, friends, relatives. 7. a) At last I decided that even this rather mannish efficient woman could do with a little help. b) He was only a boy not a man yet, but he spoke in a manly way. 8. a) The boy’s respectful manner changed noticeably. b) It may be a respectable occupation, but it Sounds rather criminal to me. 9. a) «Who is leading in the pennant race?» said this strange butler in a feverish whisper, b) It was an idea peculiarly suited to her temperament, an idea that she might have suggested her. self if she had thought of it …this idea of his fevered imagination. 10. Dear Daddy-Long-Legs. You only wanted to hear from me once a month, didn’t you? And I’ve been peppering you with letters every few days! But I’ve been so excited about all these new adventures that I must talk to somebody… Speaking of classics, have you ever read Hamlet? If you haven’t, do it right off. It’s perfectly exciting. I’ve been hearing about Shakespeare all my life but I had no idea he really wrote so well, I always suspected him of going largerly on his reputation. (J. Webster)1

VIII. Explain the difference between the meanings of the following words produced from the same root by means of different affixes. Translate the words into Russian.

Watery — waterish, embarrassed — embarrassing. manly — mannish, colourful — coloured, distressed — distressing, respected — respectful — respectable, exhaustive — exhausting — exhausted, bored — boring, touchy — touched — touching.

IX. Find eases of conversion in the following sentences.

1. The clerk was eyeing him expectantly. 2. Under the cover of that protective din he was able to toy with a steaming dish which his waiter had brought. 3. An aggressive man battled his way to Stout’s side. 4. Just a few yards from the front door of the bar there was an elderly woman comfortably seated on a chair, holding a hose linked to a tap and watering the pavement. 5. — What are you doing here? — I’m tidying your room. 6. My seat was in the middle of a row. I could not leave without inconveniencing a great many people, so I remained. 7. How on earth do you remember to milk the cows and give pigs their dinner? 8. In a few minutes Papa stalked off, correctly booted and well mufflered. 9. «Then it’s practically impossible to steal any diamonds?» asked Mrs. Blair with as keen an air of disappointment as though she had been journeying there for the express purpose. 10. Ten minutes later I was Speeding along in the direction of Cape Town. 11. Restaurants in all large cities have their ups and 33owns. 12. The upshot seemed to be that I was left to Пасе life with the sum of £ 87 17s 4d. 13. «A man could Hie very happy in a house like this if he didn’t have to poison his days with work,» said Jimmy. 14. I often heard that fellows after some great shock or loss have a habit, after they’ve been on the floor for a while wondering what hit them, of picking themselves up and piecing themselves together.

X. One of the italicized words in the following examples |!was made from the other by conversion. What semantic correlations exist between them?

1. a) «You’ve got a funny nose,» he added, b) He began to nose about. He pulled out drawer after drawer, pottering round like an old bloodhound. 2. a) I’d seen so many cases of fellows who had become perfect slaves |of their valets, b) I supposed that while he had been valeting old Worplesdon Florence must have trodden on this toes in some way. 3. a) It so happened that the night before I had been present at a rather cheery little supper. b) So the next night I took him along to supper with me. 4. a) Buck seized Thorton’s hand in his teeth. |Ь) The desk clerk handed me the key. 5. a) A small hairy object sprang from a basket and stood yapping in ;the middle of the room. b) There are advantages, you see, about rooming with Julia. 6. a) «I’m engaged for lunch, but I’ve plenty of time.» b) There was a time when he and I had been lads about town together, lunching and dining together practically every day. 7. a) Mr. Biffen rang up on the telephone while you were in your bath. b) I found Muriel singer there, sitting by herself at a table near the door. Corky, I took it, was out telephoning. 8. Use small nails and nail the picture on the wall. 9. a) I could just see that he was waving a letter or something equally foul in my face. b) When the bell stopped. Crane turned around and faced the students seated in rows before him. 10. a) Lizzie is a good cook. b) She cooks the meals in Mr. Priestley’s house. 11. a) The wolf was suspicious and afraid, b) Fortunately, however, the second course consisted of a chicken fricassee of such outstanding excellence that the old boy, after wolfing a plateful, handed up his dinner-pail for a second installment and became almost genial. 12. Use the big hammer for those nails and hammer them in well. 13. a) «Put a ribbon round your hair and be Alice-in-Wonderland,» said Maxim. «You look like it now with your finger in your mouth.» b) The coach fingered the papers on his desk and squinted through his bifocals. 14. a) The room was airy but small. There were, however, a few vacant spots, and in these had been placed a washstand, a chest of drawers and a midget rocker-chair, b) «Well, when I got to New York it looked a decent sort of place to me …» 15. a) These men wanted dog’s, and the dogs they wanted were heavy dogs, with strong muscles… and furry coats to protect them from the frost. b) «Jeeves,» I said, «I have begun to feel absolutely haunted. This woman dog’s me.»

XI. Explain the semantic correlations within the following pairs of words.

Shelter — to shelter, park — to park, groom — to groom, elbow — to elbow, breakfast — to breakfast, pin — to pin, trap — to trap, fish — to fish, head — to head, nurse — to nurse.

XII. Which of the two words in the following pairs is made by conversion? Deduce the meanings and use them in constructing sentences of your own.

|

star, n. — to star, v. picture, n. — to picture, v. colour, n. — to colour, v. blush, n. — to blush, v. key, n. — to key, v. fool, n. — to fool, v. breakfast, n. — to breakfast, v. house, n. — to house, v. monkey, n. — to monkey, v. fork, n. — to fork, v. slice, n. — to slice, v. |

age, n. — to age, v. touch, n. — to touch, v. make, n. — to make, v. finger, n. — to finger, v. empty, adj. — to empty, v. poor, adj. — the poor, n. pale, adj. — to pale, v. dry, adj. — to dry, v. nurse, n. — to nurse, v. dress, n. — to dress, v. floor, n. — to floor, v. |

XIII. Read the following joke, explain the type of word-building in the italicized words and say everything you can about the way they were made.

A successful old lawyer tells the following story about the beginning of his professional life:

«I had just installed myself in my office, had put in a phone, when, through the glass of my door I saw a shadow. It was doubtless my first client to see me. Picture me, then, grabbing the nice, shiny receiver of my new phone and plunging into an imaginary conversation. It ran something like this:

‘Yes, Mr. S!’ I was saying as the stranger entered the office. ‘I’ll attend to that corporation matter for you. Mr. J. had me on the phone this morning and wanted me to settle a damage suit, but I had to put him off, as I was too busy with other cases. But I’ll manage to sandwich your case in between the others somehow. Yes. Yes. All right. Goodbye.’

Being sure, then, that I had duly impressed my prospective client, I hung up the receiver and turned to him.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ the man said, ‘but I’m from the telephone company. I’ve come to connect your instrument.'»

WORD-BUILDING IN ENGLISH

Word-formation l process of creating new words from resources of a particular language according to certain semantic and structural patterns existing in the language

Word-formation l branch of Lexicology l studies the patterns on which the English language builds words l may be studied synchronically and diachronically

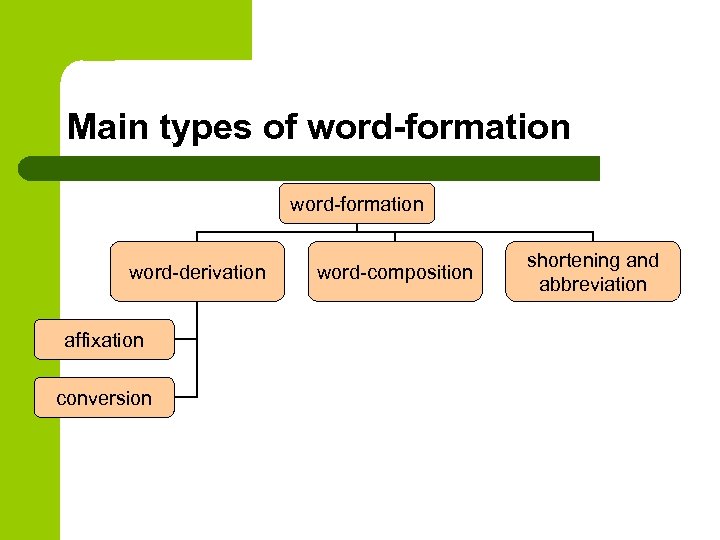

Main types of word-formation word-derivation affixation conversion word-composition shortening and abbreviation

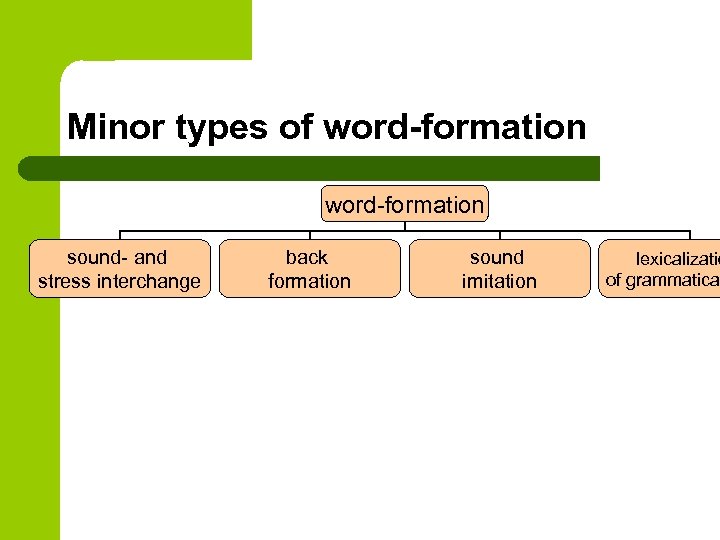

Minor types of word-formation sound- and stress interchange back formation sound imitation lexicalizatio of grammatical

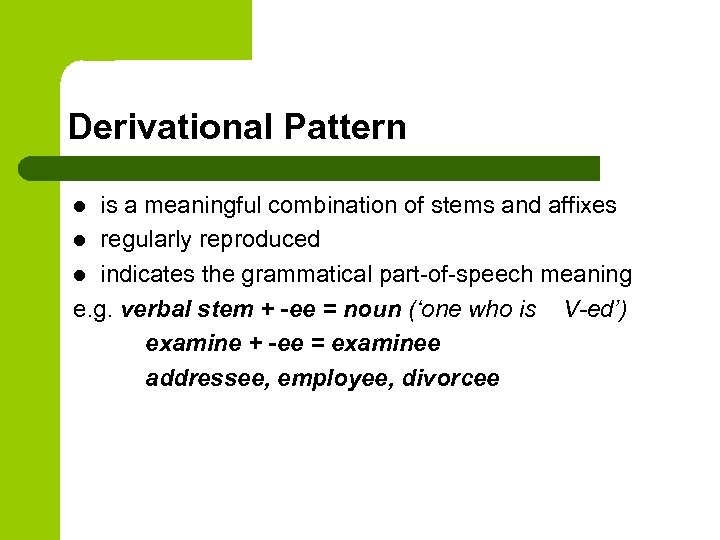

Derivational Pattern is a meaningful combination of stems and affixes l regularly reproduced l indicates the grammatical part-of-speech meaning e. g. verbal stem + -ee = noun (‘one who is V-ed’) examine + -ee = examinee addressee, employee, divorcee l

Affixation l l formation of words by adding derivational affixes to stems one of the most productive ways of wordbuilding

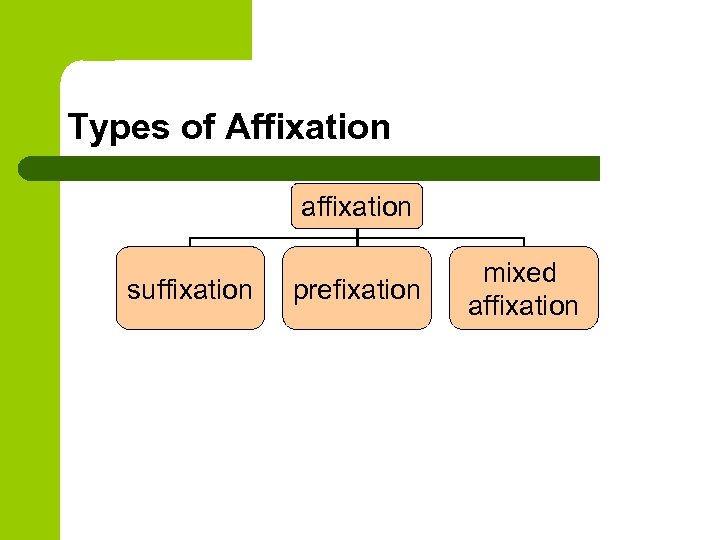

Types of Affixation affixation suffixation prefixation mixed affixation

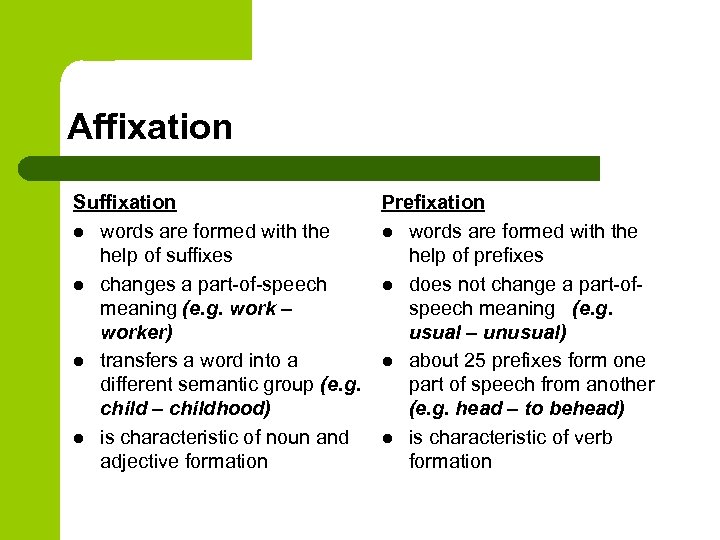

Affixation Suffixation l words are formed with the help of suffixes l changes a part-of-speech meaning (e. g. work – worker) l transfers a word into a different semantic group (e. g. child – childhood) l is characteristic of noun and adjective formation Prefixation l words are formed with the help of prefixes l does not change a part-ofspeech meaning (e. g. usual – unusual) l about 25 prefixes form one part of speech from another (e. g. head – to behead) l is characteristic of verb formation

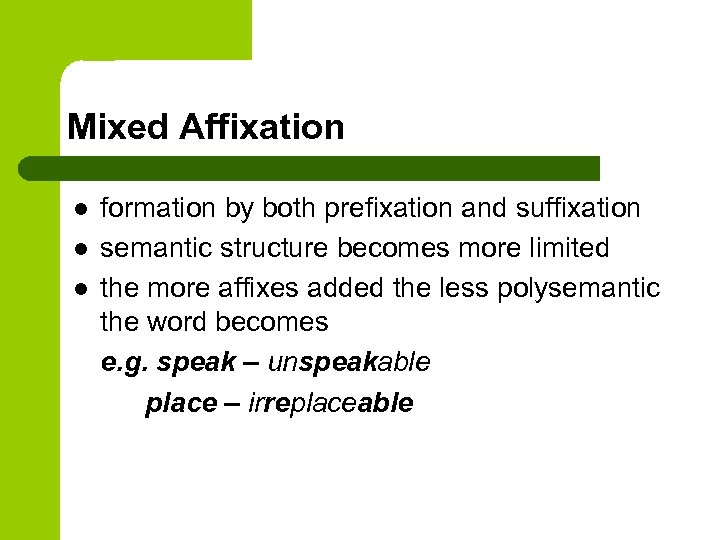

Mixed Affixation l l l formation by both prefixation and suffixation semantic structure becomes more limited the more affixes added the less polysemantic the word becomes e. g. speak – unspeakable place – irreplaceable

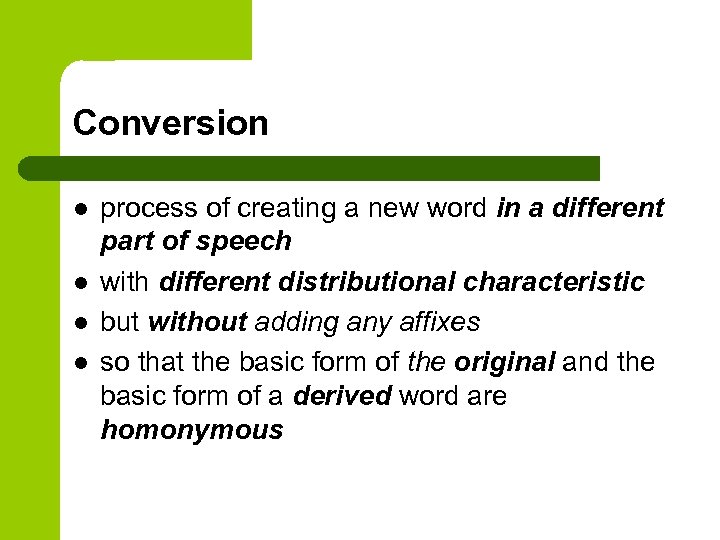

Conversion l l process of creating a new word in a different part of speech with different distributional characteristic but without adding any affixes so that the basic form of the original and the basic form of a derived word are homonymous

Conversion A new word: l has a meaning different from the original one l has a new paradigm peculiar to its new category as a part of speech l the morphemic shape of the original word remains unchanged

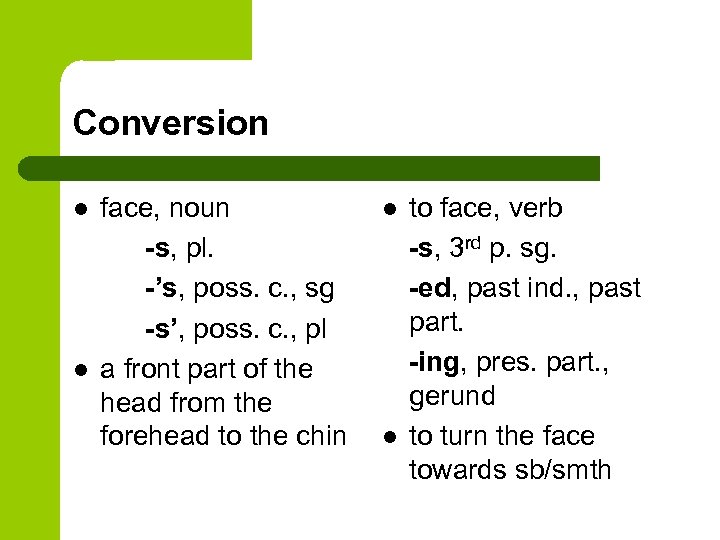

Conversion l l face, noun -s, pl. -’s, poss. c. , sg -s’, poss. c. , pl a front part of the head from the forehead to the chin l l to face, verb -s, 3 rd p. sg. -ed, past ind. , past part. -ing, pres. part. , gerund to turn the face towards sb/smth

Reasons for the widespread development of conversion absence of morphological elements which mark the part of speech of the word e. g. back (noun) – If you use mirrors you can see the l back of your head to back – Their houses back onto the river. back (adverb) – Put the book back on the shelf. back (adjective) – a back garden, back teeth

Reasons for the widespread development of conversion l simplicity of paradigms of English parts of speech l a great number of one-syllable words that are mobile and flexible

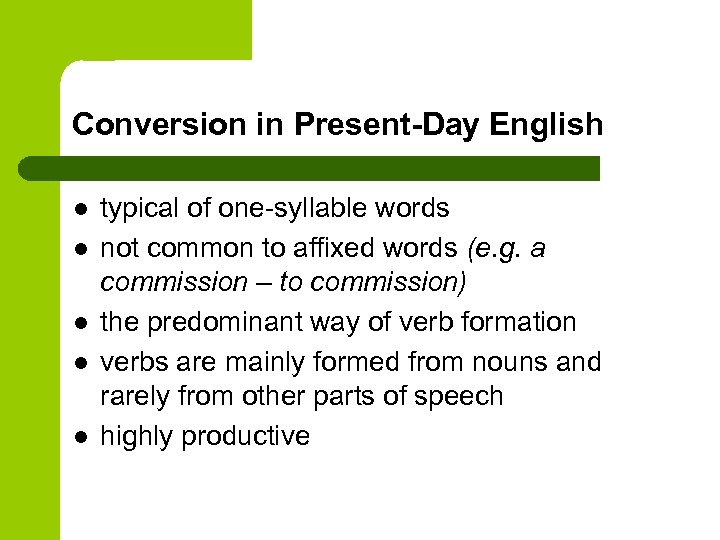

Conversion in Present-Day English l l l typical of one-syllable words not common to affixed words (e. g. a commission – to commission) the predominant way of verb formation verbs are mainly formed from nouns and rarely from other parts of speech highly productive

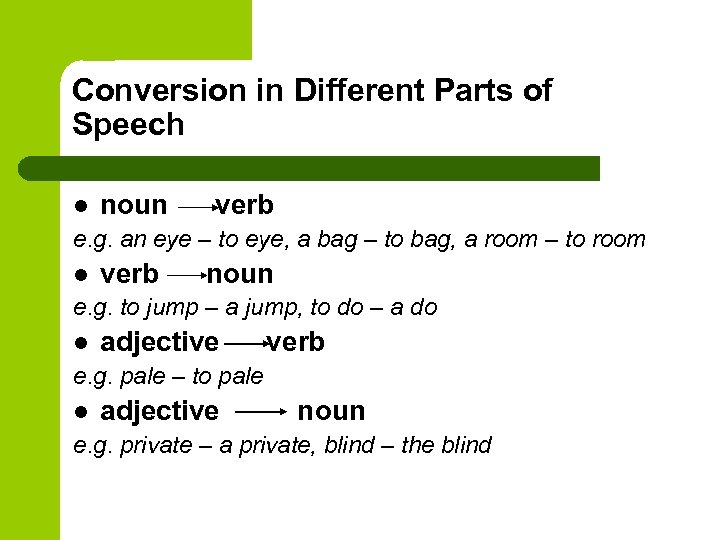

Conversion in Different Parts of Speech l noun verb e. g. an eye – to eye, a bag – to bag, a room – to room l verb noun e. g. to jump – a jump, to do – a do l adjective verb e. g. pale – to pale l adjective noun e. g. private – a private, blind – the blind

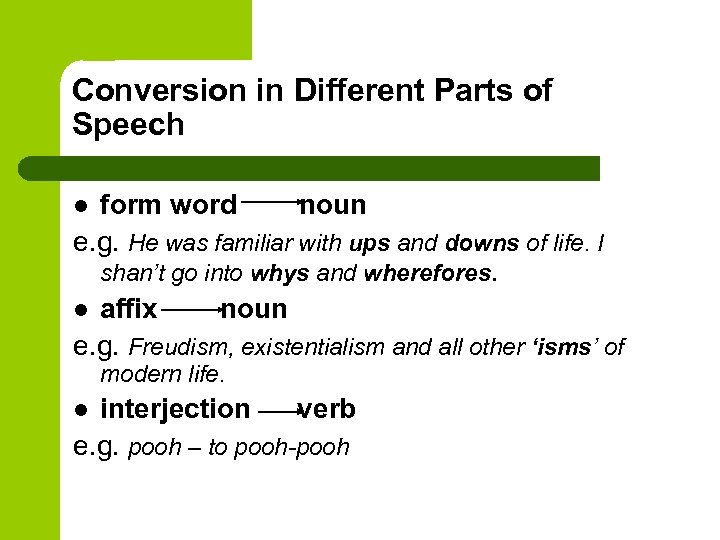

Conversion in Different Parts of Speech form word noun e. g. He was familiar with ups and downs of life. I shan’t go into whys and wherefores. l affix noun e. g. Freudism, existentialism and all other ‘isms’ of l modern life. interjection verb e. g. pooh – to pooh-pooh l

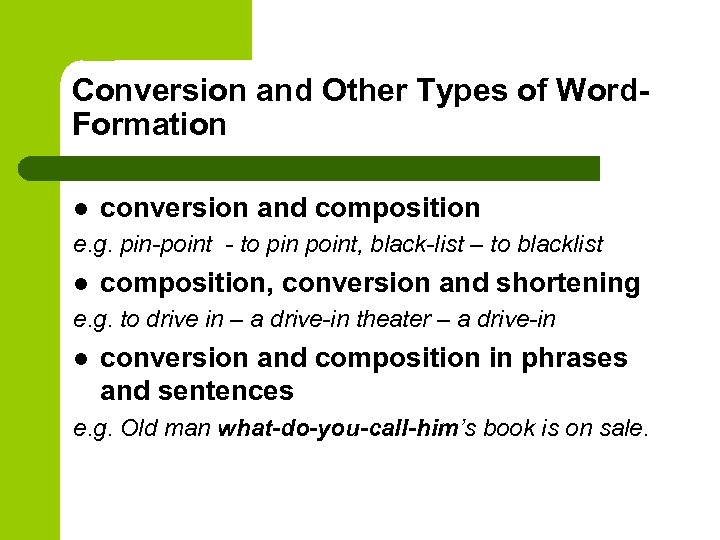

Conversion and Other Types of Word. Formation l conversion and composition e. g. pin-point — to pin point, black-list – to blacklist l composition, conversion and shortening e. g. to drive in – a drive-in theater – a drive-in l conversion and composition in phrases and sentences e. g. Old man what-do-you-call-him’s book is on sale.

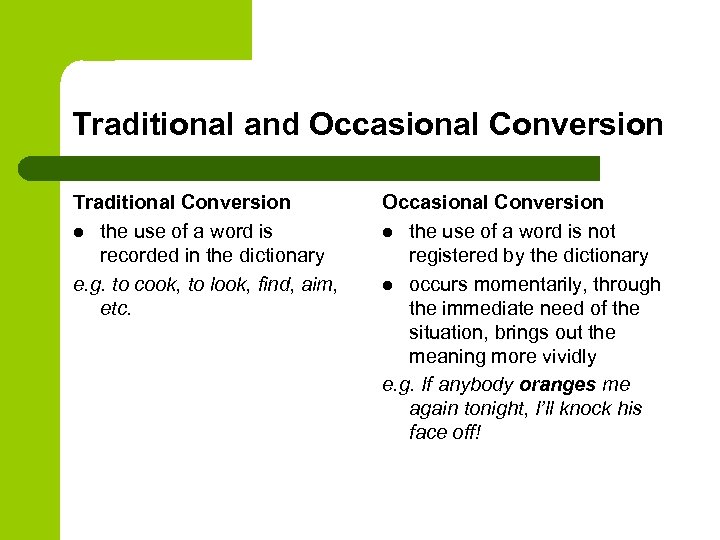

Traditional and Occasional Conversion Traditional Conversion l the use of a word is recorded in the dictionary e. g. to cook, to look, find, aim, etc. Occasional Conversion l the use of a word is not registered by the dictionary l occurs momentarily, through the immediate need of the situation, brings out the meaning more vividly e. g. If anybody oranges me again tonight, I’ll knock his face off!

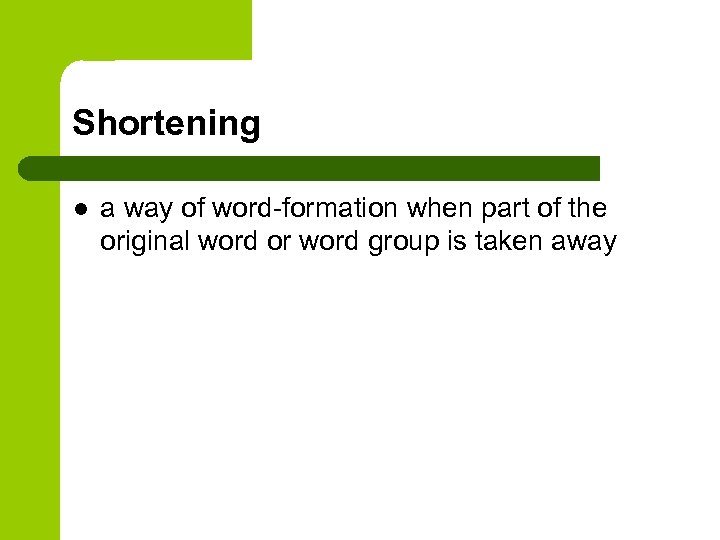

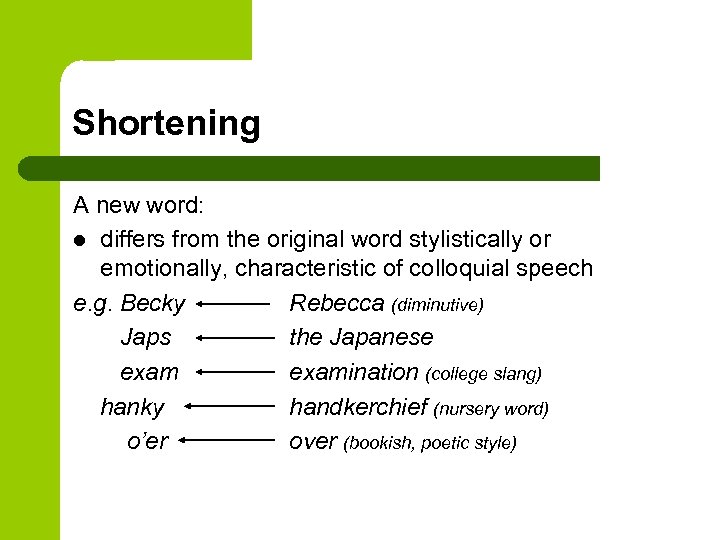

Shortening l a way of word-formation when part of the original word or word group is taken away

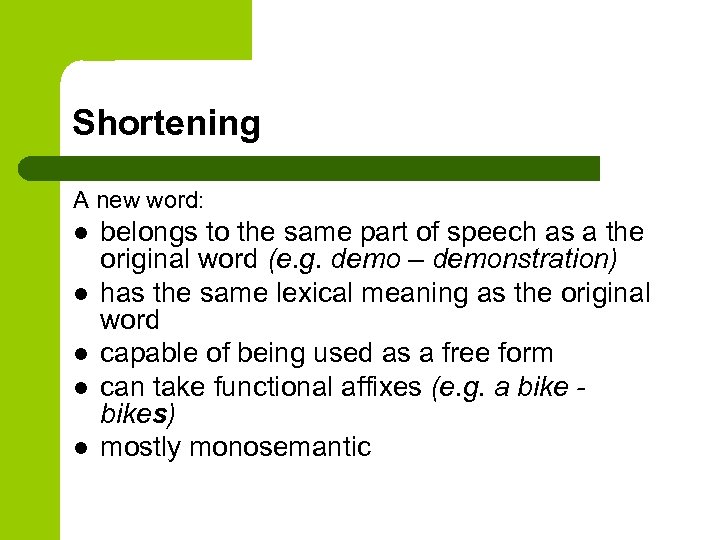

Shortening A new word: l l l belongs to the same part of speech as a the original word (e. g. demo – demonstration) has the same lexical meaning as the original word capable of being used as a free form can take functional affixes (e. g. a bikes) mostly monosemantic

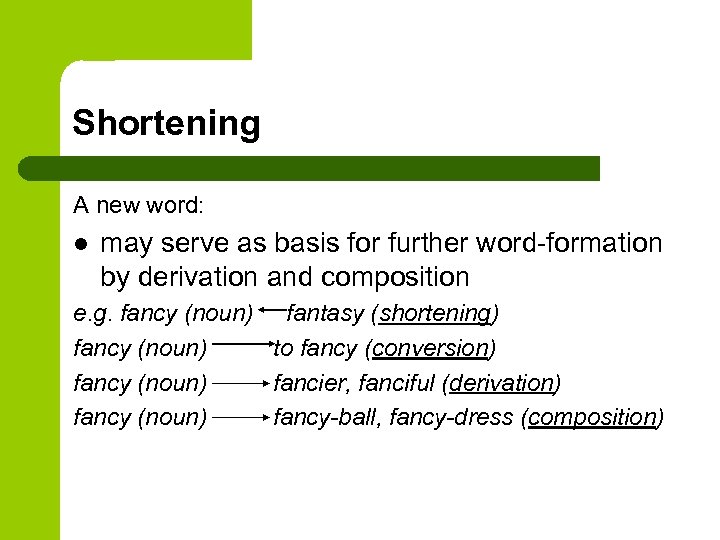

Shortening A new word: l may serve as basis for further word-formation by derivation and composition e. g. fancy (noun) fantasy (shortening) fancy (noun) to fancy (conversion) fancy (noun) fancier, fanciful (derivation) fancy (noun) fancy-ball, fancy-dress (composition)

Shortening A new word: l differs from the original word stylistically or emotionally, characteristic of colloquial speech e. g. Becky Rebecca (diminutive) Japs the Japanese examination (college slang) hanky handkerchief (nursery word) o’er over (bookish, poetic style)

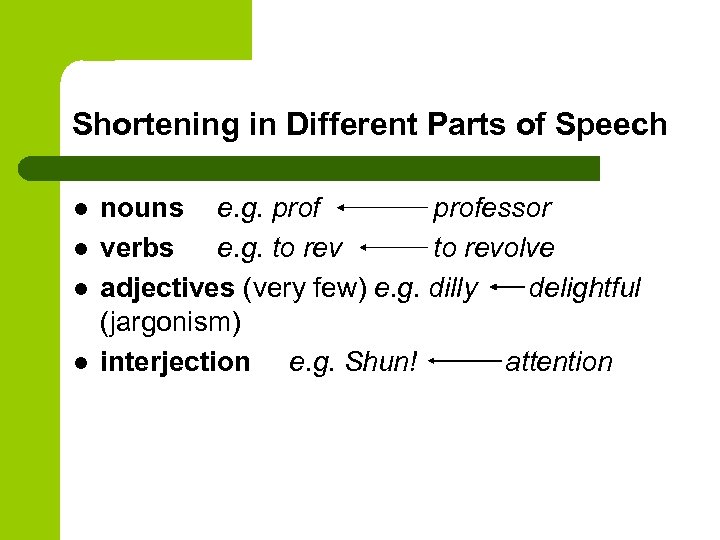

Shortening in Different Parts of Speech l l nouns e. g. professor verbs e. g. to revolve adjectives (very few) e. g. dilly delightful (jargonism) interjection e. g. Shun! attention

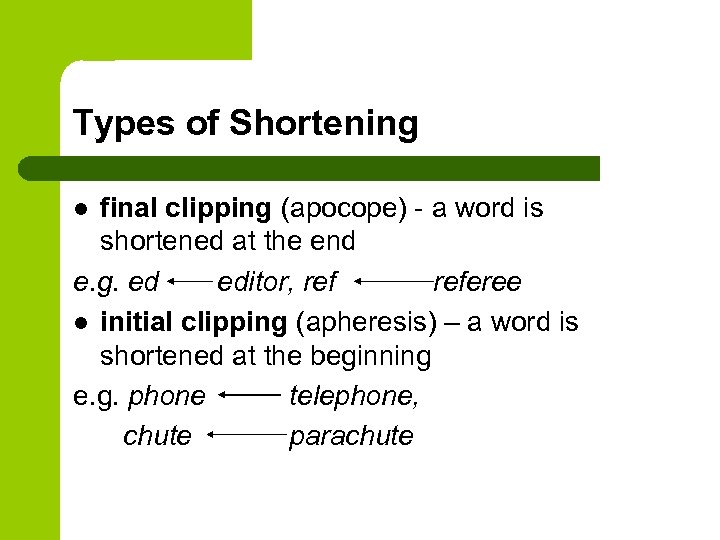

Types of Shortening final clipping (apocope) — a word is shortened at the end e. g. ed editor, referee l initial clipping (apheresis) – a word is shortened at the beginning e. g. phone telephone, chute parachute l

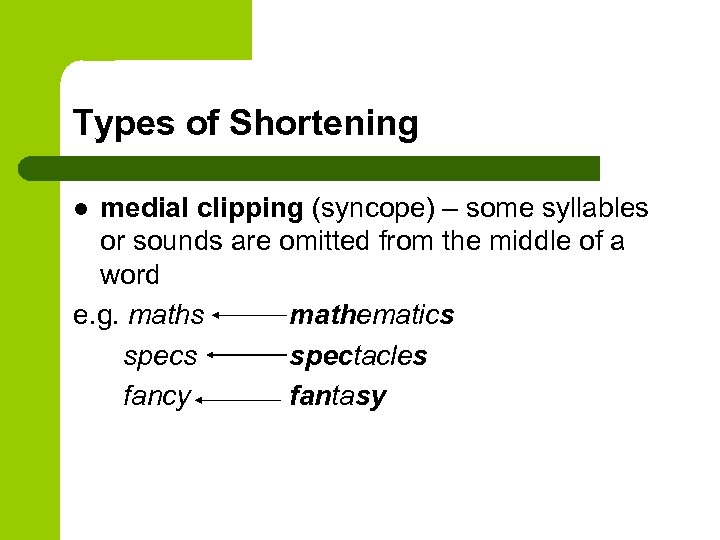

Types of Shortening medial clipping (syncope) – some syllables or sounds are omitted from the middle of a word e. g. maths mathematics spectacles fancy fantasy l

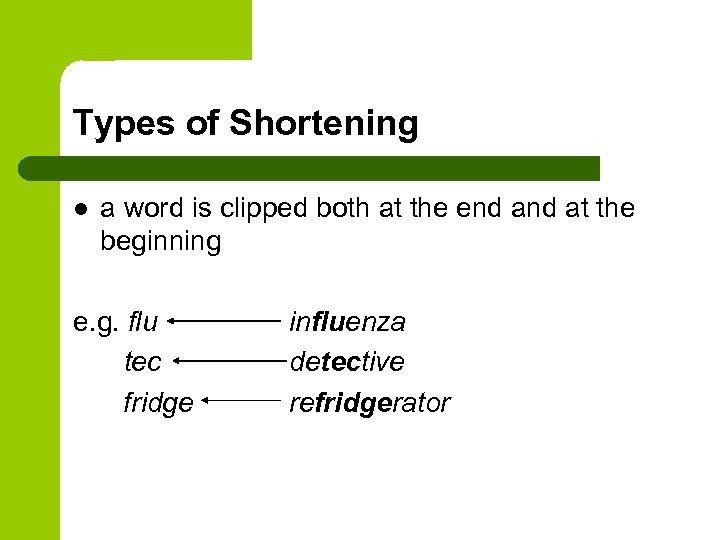

Types of Shortening l a word is clipped both at the end at the beginning e. g. flu tec fridge influenza detective refridgerator

Abbreviation (graphical shortening) l l shortening of word or word-groups in written speech in speech the corresponding full forms are used e. g. lb — pound e. g. – for example i. e. – that is Dr. – Doctor Oct. — October

Composition l l is the way of word-building when a word is formed by joining two or more stems to form one word one of the most productive ways of wordbuilding in Modern English

Compound Words consist of at least two stems which occur in the language as free forms e. g. a brother-in-law, airbus, snow-white l

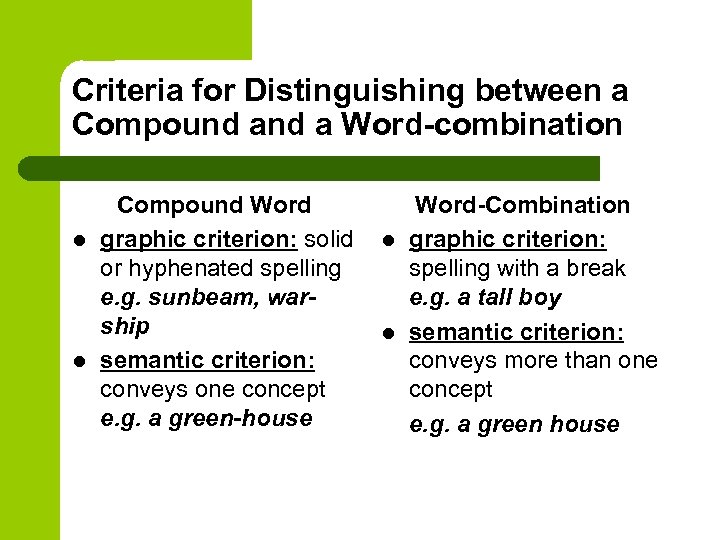

Criteria for Distinguishing between a Compound a Word-combination l l Compound Word graphic criterion: solid or hyphenated spelling e. g. sunbeam, warship semantic criterion: conveys one concept e. g. a green-house l l Word-Combination graphic criterion: spelling with a break e. g. a tall boy semantic criterion: conveys more than one concept e. g. a green house

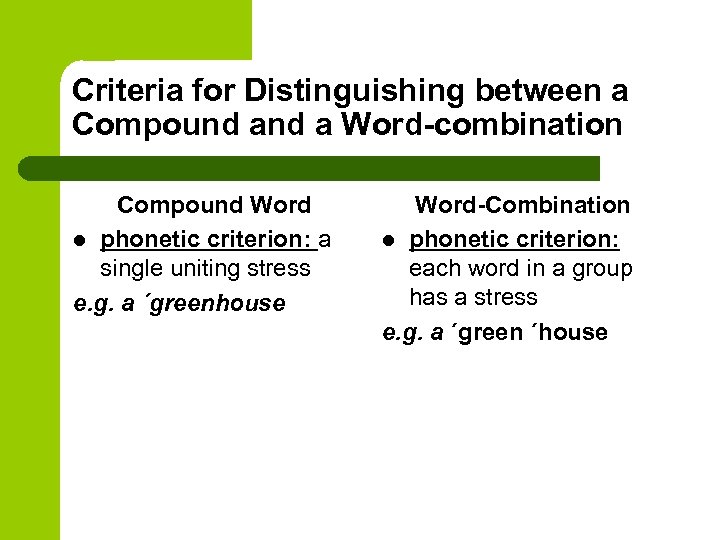

Criteria for Distinguishing between a Compound a Word-combination Compound Word l phonetic criterion: a single uniting stress e. g. a ´greenhouse Word-Combination l phonetic criterion: each word in a group has a stress e. g. a ´green ´house

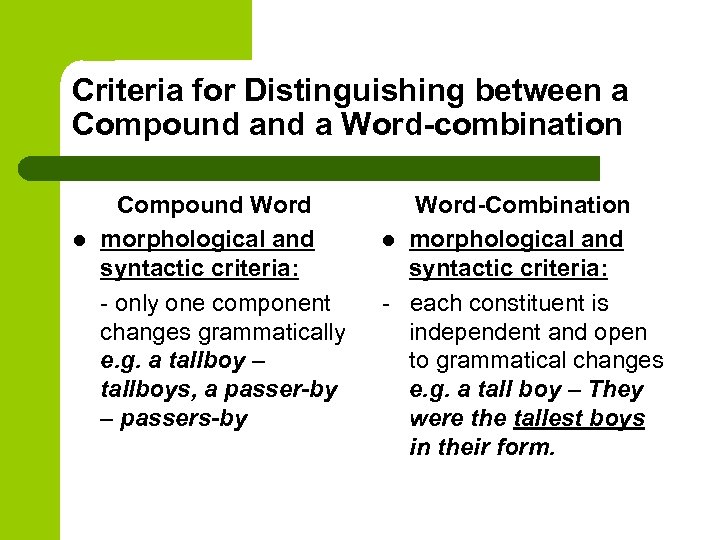

Criteria for Distinguishing between a Compound a Word-combination l Compound Word morphological and syntactic criteria: — only one component changes grammatically e. g. a tallboy – tallboys, a passer-by – passers-by Word-Combination l morphological and syntactic criteria: — each constituent is independent and open to grammatical changes e. g. a tall boy – They were the tallest boys in their form.

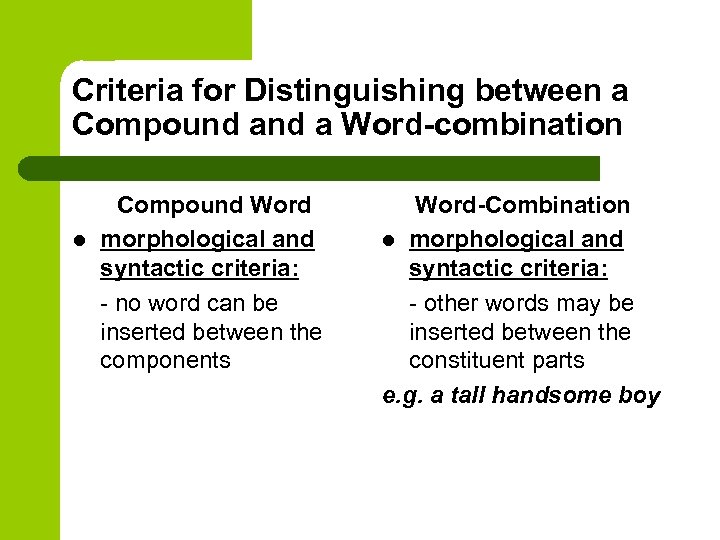

Criteria for Distinguishing between a Compound a Word-combination l Compound Word morphological and syntactic criteria: — no word can be inserted between the components Word-Combination l morphological and syntactic criteria: — other words may be inserted between the constituent parts e. g. a tall handsome boy

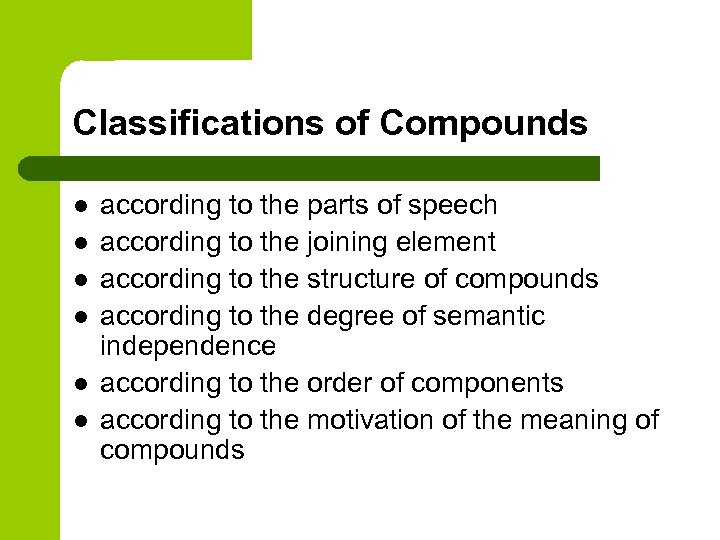

Classifications of Compounds l l l according to the parts of speech according to the joining element according to the structure of compounds according to the degree of semantic independence according to the order of components according to the motivation of the meaning of compounds

Classification of compounds according to the part of speech nouns and adjectives e. g. baby-sitter, power-hungry (энергоемкий) l adverbs and prepositions e. g. indoors, within, outside l verbs (formed by means of conversion or backformation) e. g. to handcuff hand-cuffs, to babysit baby-sitter l

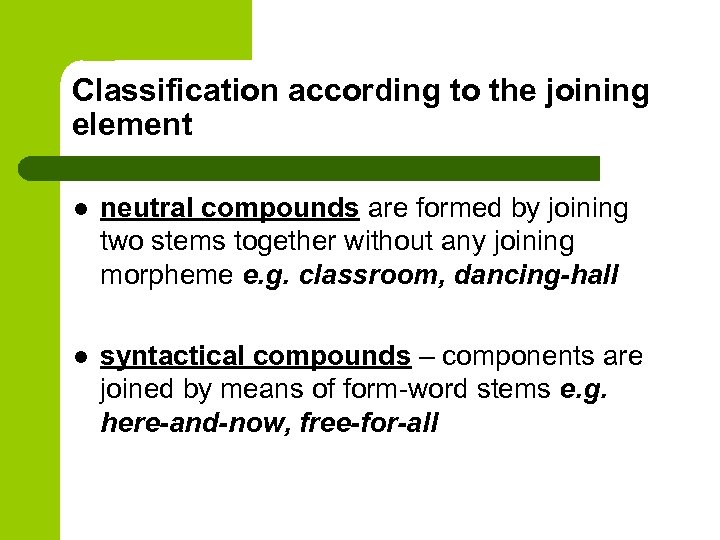

Classification according to the joining element l neutral compounds are formed by joining two stems together without any joining morpheme e. g. classroom, dancing-hall l syntactical compounds – components are joined by means of form-word stems e. g. here-and-now, free-for-all

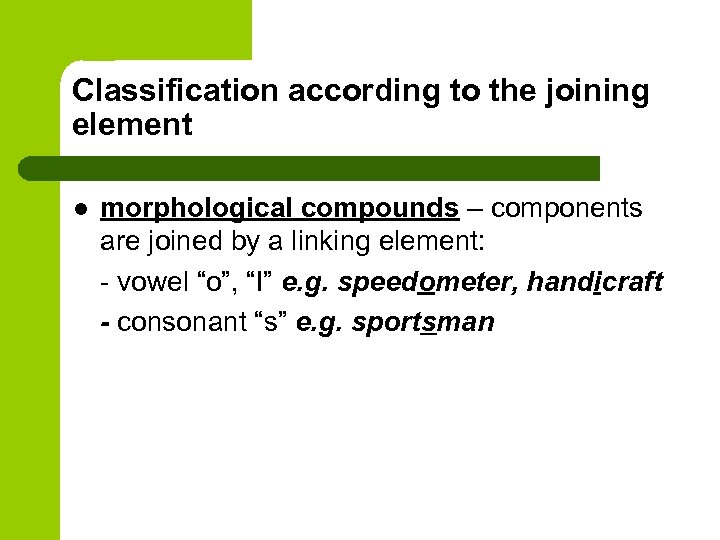

Classification according to the joining element l morphological compounds – components are joined by a linking element: — vowel “o”, “I” e. g. speedometer, handicraft — consonant “s” e. g. sportsman

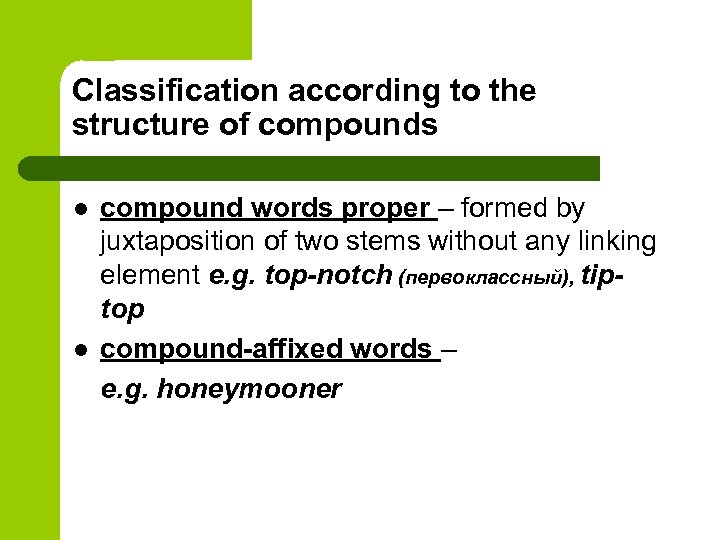

Classification according to the structure of compounds l l compound words proper – formed by juxtaposition of two stems without any linking element e. g. top-notch (первоклассный), tiptop compound-affixed words – e. g. honeymooner

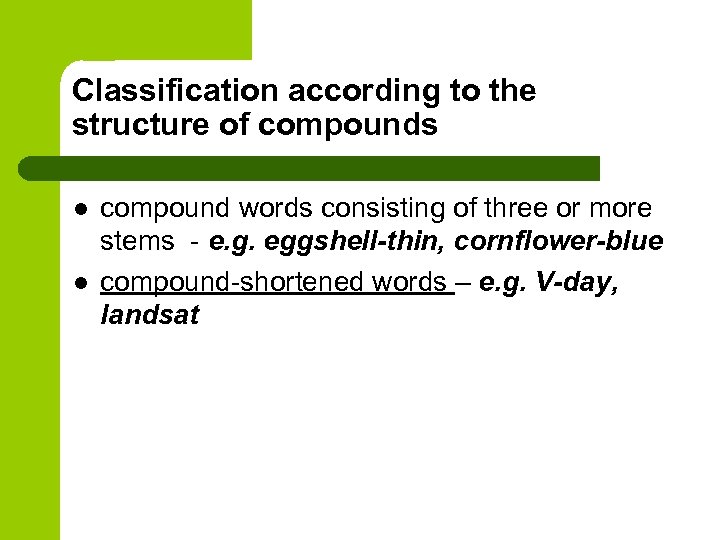

Classification according to the structure of compounds l l compound words consisting of three or more stems — e. g. eggshell-thin, cornflower-blue compound-shortened words – e. g. V-day, landsat

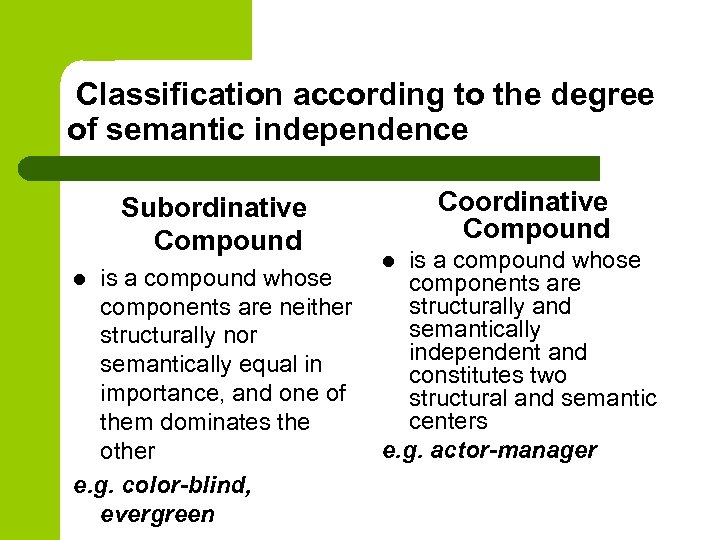

Classification according to the degree of semantic independence Subordinative Compound is a compound whose components are neither structurally nor semantically equal in importance, and one of them dominates the other e. g. color-blind, evergreen l Coordinative Compound is a compound whose components are structurally and semantically independent and constitutes two structural and semantic centers e. g. actor-manager l

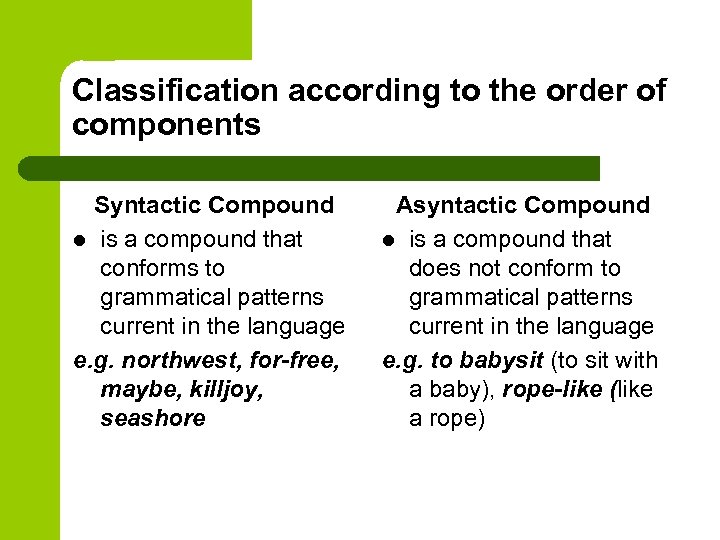

Classification according to the order of components Syntactic Compound l is a compound that conforms to grammatical patterns current in the language e. g. northwest, for-free, maybe, killjoy, seashore Asyntactic Compound l is a compound that does not conform to grammatical patterns current in the language e. g. to babysit (to sit with a baby), rope-like (like a rope)

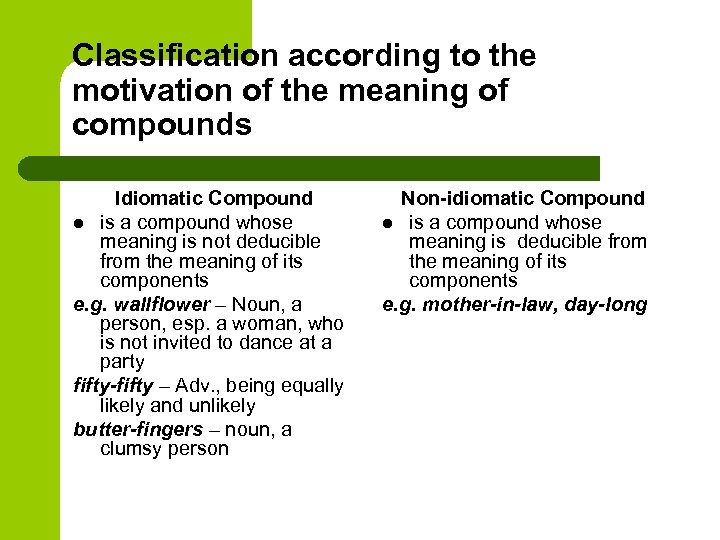

Classification according to the motivation of the meaning of compounds Idiomatic Compound l is a compound whose meaning is not deducible from the meaning of its components e. g. wallflower – Noun, a person, esp. a woman, who is not invited to dance at a party fifty-fifty – Adv. , being equally likely and unlikely butter-fingers – noun, a clumsy person Non-idiomatic Compound l is a compound whose meaning is deducible from the meaning of its components e. g. mother-in-law, day-long

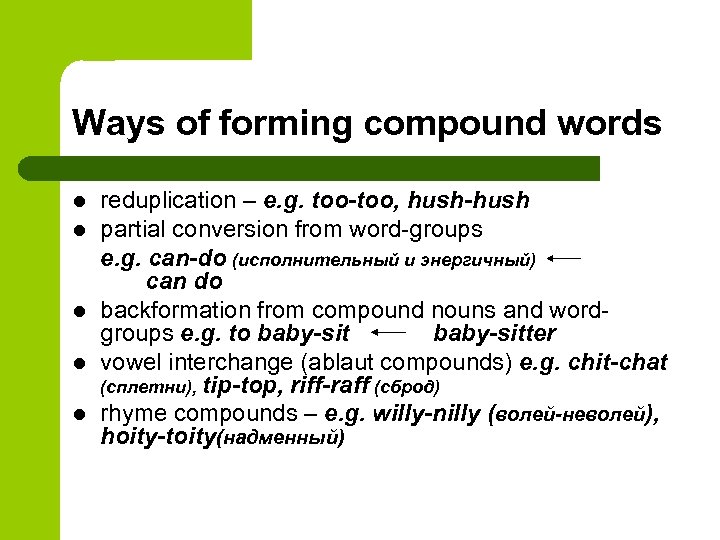

Ways of forming compound words l l l reduplication – e. g. too-too, hush-hush partial conversion from word-groups e. g. can-do (исполнительный и энергичный) can do backformation from compound nouns and wordgroups e. g. to baby-sitter vowel interchange (ablaut compounds) e. g. chit-chat (сплетни), tip-top, riff-raff (сброд) rhyme compounds – e. g. willy-nilly (волей-неволей), hoity-toity(надменный)

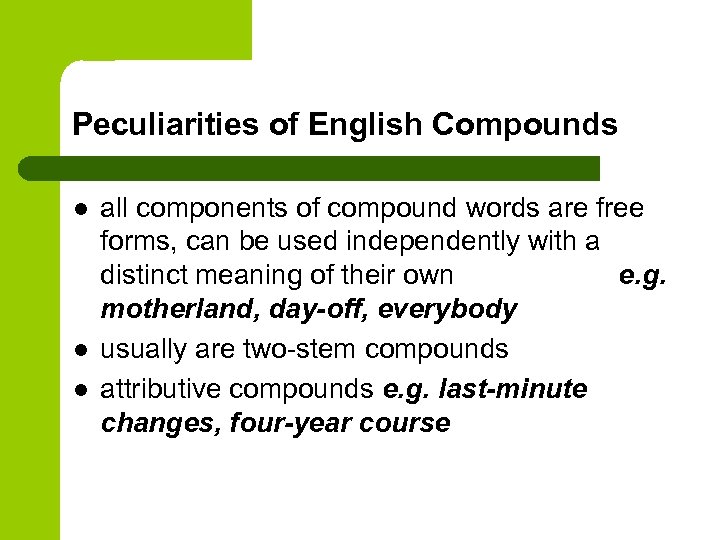

Peculiarities of English Compounds l l l all components of compound words are free forms, can be used independently with a distinct meaning of their own e. g. motherland, day-off, everybody usually are two-stem compounds attributive compounds e. g. last-minute changes, four-year course

Sound Interchange l way of forming new words with the help of change of sounds within a word

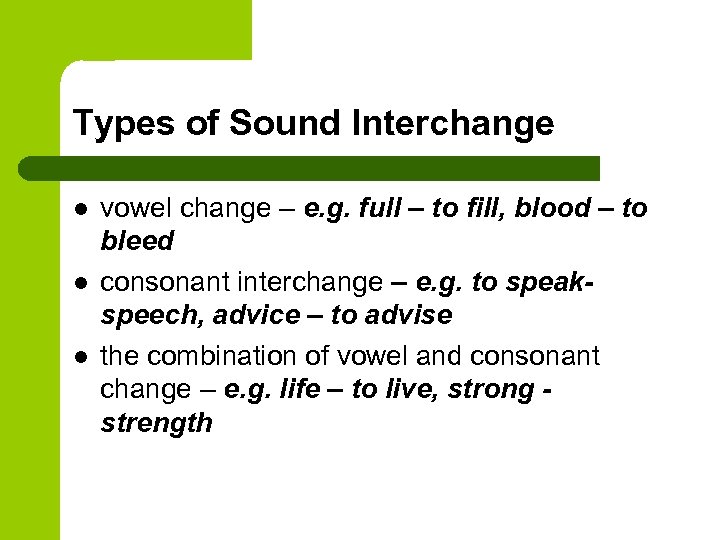

Types of Sound Interchange l l l vowel change – e. g. full – to fill, blood – to bleed consonant interchange – e. g. to speakspeech, advice – to advise the combination of vowel and consonant change – e. g. life – to live, strong strength

Stress Interchange l e. g. ´import — to im´port, ´suspect – to sus´pect

Lexicalization of Grammatical Form l way of creating new words with the help of suffix “s” e. g. glass – glasses, custom – customs, colour — colours

Backformation l way of creating new words by subtracting a real or supposed suffix from the original word e. g. to beggar, to editor, to burgler

Sound Imitation (Onomatopoeia) l way of forming new words by imitating different kinds of sounds that may be produced by animals, birds, insects, human being and inanimate objects e. g. buzz, croak, moo, mew, purr, roar e. g. clink, whip, splash, bubble e. g. giggle, mutter, babble

This tutorial will introduce you to the basic concept of how a certain class of words are constructed in Standard English.

What is a Morpheme?

Table 1 Examples of constraints: Click Photo For Large View

A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning. It can be expressed in three different ways: as a word, whether monosyllabic, e.g., coat, love, or polysyllabic, e.g., pillow, avocado, as a syllable, e.g., un- as in unforgiving, or re- as in refocus, or sound segment, e.g., -s as in apples, or –th as in width.

Principle of Compositionality

The meaning of a simple or complex expression is fully determined by the meaning of its constituents and its structure. In other words, the parts equal the whole. Thus words generally can be understood as a root meaning + additional morphemes required to communicate a concept. For example, the root run means to move one’s body quickly across a surface. By attaching –er to the root, we now have a morphologically complex word that refers to the person who move his/her body quickly across a surface.

Productivity is the notion that a given morpheme has a high frequency of usage to the extent that its meaning is clear even when not attached to a root, or when attached to an unlikely or novel root. This gives speakers the possibility to accurately recognize forms we’ve never heard before. For example, we are more likely to derive a noun from an adjective using –ness rather than –th. Take the new adjective lit, which means exciting, crazy, or amazing and attach –ness to form litness, and despite the fact that the latter is not an officially recognized lexical item, the understanding would be clear, even if a bit awkward. However, a combination of lit + –th, would not be understood.

Not only are some morphemes more productive than others, but languages also adhere to language specific constraints that restrict, which affixes can attach to various parts of speech.

Hierarchy

Table 2 Click For Large View

Word composition must not only adhere to language specific constraints as to which morphemes may be attached to a word (meaning + part of speech) but must also adhere to the order in which they are attached – this is referred to as the hierarchy of compositionality. Word trees allow us to diagram the structure of the word as a systematic process by which meaning is composed. They show the number of morphemes, and the order in which they attach to one another.

Take a look…

disappearance

How can we determine the process by which the word disappearance is constructed? These are the steps:

- Locate the root: appear

- List words that have the prefix dis-, and we list words that have the suffix –ance.

*Note: This can only be done with words composed of 2 or more morphemes (one prefix + root, root + suffix). Morphemes must belong unambiguously to one part of speech. Let’s look at the pattern in Table 2:

figure 1 Click Photo For Larger View

- State the rules:

We see that dis- attaches to verbs, and does not change the part of speech:

appear – disappear

V V

–ance attaches to verbs, and does change part of speech:

appear – disappear

V N

- Starting with the root, add one affix at a time, noting the resulting part of speech. This construction referred to as unambiguous since there is only one possible order by which the word may be formed. Now take a look at the word unlockable. Following the steps above results in two possible constructions.

figure 2 Click Photo For Larger View

- Locate the root: lock (as a verb) List words that have the prefix un-, and those that have the suffix –able.

- un– attaches to adjectives and a few restricted verbs and does not change the part of speech. –able attaches to verbs to derive adjectives. We see that un- attaches to verbs, and does not change the part of speech:

lock – unlock

V V

–able attaches to verbs, and does change part of speechlock – lockable

V Adj - State the rules:

So both constructions are grammatical. What does this mean? It means that each structure yields a different meaning. Think about it. In figure 2, example a. unlock means to open an item that is locked. Unlockable thus means the item is able to be unlocked. In b., lockable means that an item may be locked if necessary. Unlockable means it cannot be locked if necessary!

This is construction referred to as ambiguous since there are two possible orders by which the word is formed, each resulting in a different meaning.

You may have to read this section over a few times to wrap your brain around this concept.

For practice on word construction, go to our Morphology: Word Compositionality 1.1.

R. Aronow, K. Bannar

Back to Morphology Tutorials

The wake-up packets sent by the site server are constructed using the MAC address of the target computer,

hardware inventory information previously collected.

Пакеты пробуждения, отправленные сервером сайта, составлены с использованием MAC- адреса конечного компьютера, полученного во время

предыдущего сбора сведений об оборудовании.

Weighted projective spaces can be constructed using a polynomial ring whose variables have non-standard degrees.

Взвешенные проективные пространства можно построить, используя кольца многочленов с нестандартными степенями переменных.

and standard deviation parameters and will yield an appropriate QuantityDistribution.

и стандартного отклонения и даст соответствующее распределение QuantityDistribution.

600 m² of large-area formwork.

Для возведения четырех стеновых панелей башни применялись 28 подъемно-переставных автоматов и 600 м² крупноформатной опалубки.

To do that they use marginal abatement cost curves, also called»GHG mitigation supply curves» that are constructed

using

a bottom-up approach.

Для этого они используют кривые предельных затрат на снижение выбросов, известные также под названием» кривые предложения для сокращения выбросов ПГ», которые строятся на основе подхода» от частного к общему.

Tanks are constructed

using

natural stones, cement blocks, ferro-cement or reinforced concrete.

Резервуары для хранения воды сооружаются с использованием природного камня, цементных блоков, армоцемента или железобетона.

Signals Si are constructed

using

auxiliary signals, which propagate to the left.

Сигналы Si генерируются с использованием вспомогательных сигналов, распространяющихся влево.

The properties are constructed

using

locally sourced stone in order to blend in with the geography of the peninsula.

Недвижимость построена с использованием местного камня для гармоничного сочетания с окрестностями полуострова.

Getting started with server-side programming

is

usually easier than with client-side development,

because dynamic websites tend to perform a lot of very similar operations, and are constructed

using

web frameworks that make these

and other common web server operations easy.

Начинать с серверного программировния обычно легче, чем с разработки на стороне

клиента, поскольку динамические веб- сайты склонны производить множество однообразных операций и сконструированы с использованием веб- фреймворков, которые выполняют эти и

другие привычные веб- серверу операции с легкостью.

All buildings were constructed

using

the principles of bio-climatic architecture.

Все здания были построены с использованием принципов био климатический архитектуры.

The internal network within the apartment is constructed

using

Cat6 cables.

Внутренняя сеть квартиры будет построена с использованием кабелей категории 6.

Furthermore, the majority of housing was constructed

using

materials of poor quality.

Кроме того, большинство домов было построено с использованием материалов низкого качества.

The CeBIT stand of Zurich University was constructed

using

the“In-situ Fabricator”.

Стенд Университета г. Цюрих на выставке CeBIT был построен с применением технологии“ In- situ Fabricator”.

В 1952 году была построена электростанция мощностью 100 МВт, работающая на ШМ.

The panel is constructed

using

statistical methods of calculation with a.

Панель строится с использованием статистических методов расчета со.

The administrative and household building was constructed

using

energy-efficient technologies and materials.

Административно- бытовой корпус построен с использованием энергоэффективных технологий и материалов.

As 18 2× 32, a regular octadecagon cannot be constructed

using

a compass and straightedge.

Имея 18 2× 32 сторон, правильный восемнадцатиугольник не может быть построен с помощью циркуля и линейки.

Eighty-six low-cost housing units in urban areas of»Somaliland» were constructed

using

community contracting methods.

В городских районах<< Сомалиленда>> на основе методов общинного подряда было построено 86 единиц дешевого жилья.

and took into account climate change and krill fishery management.

учитывающая изменение климата и управление промыслом криля.

Then the template is constructed

using

the contour representation of the face.

После этого формируется шаблон, содержащий контурное представление области лица.

and has a wooden compressor and a bent metal gas turbine.

Его первый двигатель был построен с использованием ручного инструмента

и имел деревянный компрессор и турбину из изогнутого металла.

The catalog was constructed

using

Rejewski’s»cyclometer», a special-purpose device for

creating a catalog of permutations.

Картотека была создана при помощи« циклометра» Реевского, специального устройства

для создания каталога перестановок.

but later Paik

used

parts from radio and television sets.

Ранние работы такого плана были сконструированы преимущественно из кусков проволоки и металла,

позднее включали радио и телевизоры.

Results: 727571,

Time: 0.3383

English

—

Russian

Russian

—

English

построенный, созданный

глагол

- строить, сооружать; воздвигать; конструировать

- составлять, строить (предложение, уравнение и т. д.)

- создавать; сочинять; придумывать

- конструктивный элемент, конструктив

- структурный компонент

существительное

- (мысленная) конструкция; концепция; положение; конструкт

- конструкция, сооружение; логическая структура

- особ. мысленная

- обобщенный образ (чего-л.)

- мат. (геометрическое) построение

Мои примеры

Словосочетания

constructed data — данные контрольного примера; искусственные данные

experimentally-constructed — экспериментально сконструированный

systematically constructed basis sets — систематически построенные базисные наборы

be constructed from — изготавливаться из

be constructed of — конструироваться из

completely constructed object — завершённый строительством объект

completely constructed project — законченный строительством объект

constructed and installed equipment — изготовленное и установленное оборудование

sturdily constructed — прочной конструкции

constructed value — условная цена

Примеры с переводом

The writer constructed the story from memories of her childhood.

В основу сюжета писательница положила свои детские воспоминания.

Boyce has constructed a new theory of management.

Бойс создал новую теорию управления.

The hut was constructed from trees that grew in the nearby forest.

Домик построили из деревьев, срубленных в близлежащем лесу.

The products are poorly constructed; ergo, they break easily.

Эти изделия плохо сконструированы, а следовательно, они легко ломаются.

Habitations were constructed on platforms raised above the lake, and resting on piles.

Жилища были построены на платформах, поднятых при помощи свай над уровнем озера.

The arriving national guardsmen were forced to live in a hutment until permanent barracks could be constructed.

Прибывающие нацгвардейцы были вынуждены жить во временных бараках, пока не появилась возможность построить постоянные казармы.

Примеры, ожидающие перевода

Some eccentric constructed an electric brassiere warmer

Only the buildings that were constructed of more substantial materials survived the earthquake.

…although the winery is brand-new, it has been constructed and decorated to give it a patina of old-world quaintness…

Для того чтобы добавить вариант перевода, кликните по иконке ☰, напротив примера.

Возможные однокоренные слова

construct — конструкция, концепция, строить, создавать, конструировать

construction — строительство, конструкция, построение, сооружение, здание, строение, стройка

constructing — строительство, строительный, строящий

reconstructed — восстановленный

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.