.

There are some rules for joining two different words into one, but they do not cover all cases

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY ABOUT JOINING WORDS TOGETHER

Is it correct to write bath tub, or should it be the single word bathtub? Is every day a correct spelling, or everyday? Uncertainties like this are widespread in English, even among proficient users. They are made worse by the fact that in some cases both spellings are correct, but mean different things.

Are there any guidelines for resolving such uncertainties? It seems that in some cases there are and in some there are not. I wish here to indicate some of these guidelines. They mostly involve combinations that can make either one word or two, depending on meaning or grammar.

.

ORDINARY COMPOUNDS

Ordinary compounds are the area with the fewest guidelines. They include words like coursework, which I like to write as a single word but my Microsoft Word spellchecker tells me should be two. As a linguist, I usually disregard computer advice about language (see 68. How Computers Get Grammar Wrong), but the question of why ordinary compound words give especial problems is interesting. First, these words need to be defined.

One can think of a compound as two or more words joined together. Linguists, though, like to speak of joined roots or stems rather than words, partly because the joining into a compound stops them being words (a few are not even words by themselves, e.g. horti- in horticulture).

Another problem with “joined words” is that some, such as fearless, are not considered compounds at all. The -less ending is called not a “root” but an “affix”, a meaningful word part added to a root to modify its meaning. Most affixes (some named suffixes, e.g. -less, -ness, -tion, -ly, -ing; some prefixes, e.g. -un-, in-, mis-, pre-) cannot be separate words, but a few like -less can (see 106. Word-Like Suffixes and 146. Some Important Prefix Types). Thus, words like fearless, unhappy and international are not compounds because they have fewer than two roots. Other compounds are swimsuit, homework and eavesdrop.

Suggestions for recognising a compound are not always very helpful. The frequency of words occurring together is no guide because it ignores the fact that many frequent combinations are not compounds (e.g. town hall and open air). The grammatical classes of the words and the closeness of the link between them are sometimes mentioned, but are unreliable. The age of a combination is also suggested, the claim being that compounds originate as two separate words, and gradually evolve through constant use first into hyphenated expressions (like fire-eater or speed-read – see 223. Uses of Hyphens), and eventually into compounds. However, some quite recent words are already compounds, such as bitmap in computing.

Much more useful is the way compounds are pronounced. Single English words generally contain one syllable that is pronounced more strongly than the others (see 125. Stress and Emphasis). This means compounds should have just one strong syllable, while non-compounds should have more. The rule applies fairly universally (see 243. Pronunciation Secrets, #3). For example, home is the only strong syllable in homework, but one of two in home rule. I write coursework as one word because course- is stronger than work.

The only problem with this approach is that you have to know pronunciations before you start, which is not always the case if English is not your mother tongue. The only other resort is a dictionary or spellcheck!

.

NOUNS DERIVED FROM PHRASAL VERBS

Happily, some compound words have some other helpful features. Most are words whose roots, if written as two words, are also correct but have different meaning and grammar, so that the meaning indicates the spelling or vice versa. A particularly large category of such words is illustrated by the compound noun giveaway (= “obvious clue”). If its two roots are written separately as give away, they become a “phrasal” verb – a combination of a simple English verb (give) with a small adverb (away) – meaning “unintentionally reveal” (see 244. Special Uses of GIVE, #12).

There are many other nouns that can become phrasal verbs, e.g. takeover, takeaway, makeup, cutoff, breakout, setdown, pickup, washout, login and stopover. In writing there is always a need to remember that, if the two “words” are going to act as a verb, they must be spelled separately, but if they are going to act as a noun, they must be written together.

.

OTHER CHOICES THAT DEPEND ON WORD CLASS

In the examples above, it is the choice between noun and verb uses that determines the spelling. Other grammatical choices can have this effect too. The two alternative spellings mentioned earlier, every day and everyday, are an example. The first (with ev- and day said equally strongly) acts in sentences like a noun or adverb, the second (with ev- the strongest) like an adjective. Compare:

(a) NOUN: Every day is different.

(b) ADVERB: Dentists recommend cleaning your teeth every day.

(c) ADJECTIVE: Everyday necessities are expensive.

In (a), every day is noun-like because it is the subject of the verb is (for details of subjects, see 12. Singular and Plural Verb Choices). In (b), the same words act like an adverb, because they give more information about a verb (cleaning) and could easily be replaced by a more familiar adverb like regularly or thoroughly (see 120. Six Things to Know about Adverbs). In (c), the single word everyday appears before a noun (necessities), giving information about it just as any adjective might (see 109. Placing an Adjective after its Noun). It is easily replaced by a more recognizable adjective like regular or daily. For more about every, see 169. “All”, “Each” and “Every”.

Another example of a noun/adverb contrast is any more (as in …cannot pay any more) versus anymore (…cannot pay anymore). In the first, any more is the object of pay and means “more than this amount”, while in the second anymore is not the object of pay (we have to understand something like money instead), and has the adverb meaning “for a longer time”.

A further adverb/adjective contrast is on board versus onboard. I once saw an aeroplane advertisement wrongly saying *available onboard – using an adjective to do an adverb job. The adverb on board is needed because it “describes” an adjective (available). The adjective form cannot be used because there is no noun to describe (see 6. Adjectives with no Noun 1). A correct adjective use would be onboard availability.

Slightly different is alright versus all right. The single word is either an adjective meaning “acceptable” or “undamaged”, as in The system is alright, or an adverb meaning “acceptably”, as in The system works alright. The two words all right, on the other hand, are only an adjective, different in meaning from the adjective alright: they mean “100% correct”. Thus, Your answers are all right means that there are no wrong answers, whereas Your answers are alright means that the answers are acceptable, without indicating how many are right.

Consider also upstairs and up stairs. The single word could be either an adjective (the upstairs room) or an adverb (go upstairs) or a noun (the upstairs). It refers essentially to “the floor above”, without necessarily implying the presence of stairs at all – one could, for example, go upstairs in a lift (see 154. Lone Prepositions after BE). The separated words, by contrast, act only like an adverb and do mean literally “by using stairs” (see 218. Tricky Word Contrasts 8, #3).

The pair may be and maybe illustrates a verb and adverb use:

(d) VERB: Food prices may be higher.

(e) ADVERB: Food prices are maybe higher.

In (e), the verb is are. The adverb maybe, which modifies its meaning, could be replaced by perhaps or possibly. Indeed, in formal writing it should be so replaced because maybe is conversational (see 108. Formal and Informal Words).

My final example is some times and sometimes, noun and adverb:

(f) NOUN: Some times are harder than others.

(g) ADVERB: Sometimes life is harder than at other times.

Again, replacement is a useful separation strategy. The noun times, the subject of are in (f), can be replaced by a more familiar noun like days without radically altering the sentence, while the adverb sometimes in (g) corresponds to occasionally, the subject of is being the noun life.

.

USES INVOLVING “some”, “any”, “every” AND “no”

The words some, any, every and no generally do not make compounds, but can go before practically any noun to make a “noun phrase”. In a few cases, however, this trend is broken and these words must combine with the word after them to form a compound. Occasionally there is even a choice between using one word or two, depending on meaning.

The compulsory some compounds are somehow, somewhere and somewhat; the any compounds are anyhow and anywhere, while every and no make everywhere and nowhere. There is a simple observation that may help these compounds to be remembered: the part after some/any/every/no is not a noun, as is usually required, but a question word instead. The rule is thus that if a combination starting with some, any, every or no lacks a noun, a single word must be written.

The combinations that can be one word or two depending on meaning are someone, somebody, something, sometime, sometimes, anyone, anybody, anything, anyway (Americans might add anytime and anyplace), everyone, everybody, everything, everyday, no-one, nobody and nothing. The endings in these words (-one, -body, -thing, -way, -time, -place and –day) are noun-like and mean the same as question words (who? what/which? how? when? and where? – see 185. Noun Synonyms of Question Words).

Some (tentative) meaning differences associated with these alternative spellings are as follows:

SOME TIME = “an amount of time”

Please give me some time.

SOMETIME (adj.) = “past; old; erstwhile”

I met a sometime colleague

.

SOMETHING = “an object whose exact nature is unimportant”.

SOME THING = “a nasty creature whose exact nature is unknown” (see 260. Formal Written Uses of “Thing”, #2).

Some thing was lurking in the water.

.

ANYONE/ANYBODY = “one or more people; it is unimportant who”

Anyone can come = Whoever wants to come is welcome; Choose anyone = Choose whoever you want – one or more people.

ANY ONE = “any single person/thing out of a group of possibilities”.

Any one can come = Only one person/thing (freely chosen) can come; Choose any one = Choose whoever/whichever you want, but only one.

ANY BODY = “any single body belonging to a living or dead creature”.

Any body is suitable = I will accept whatever body is available.

.

ANYTHING = “whatever (non-human) is conceivable/possible, without limit”.

Bring anything you like = There is no limit in what you can bring; Anything can happen = There is no limit on possible happenings.

ANY THING = “any single non-human entity in a set”.

Choose any thing = Freely choose one of the things in front of you.

.

EVERYONE/EVERYBODY = “all people” (see 169. “All”, “Each” and “Every” and 211.General Words for People).

Everyone/Everybody is welcome.

EVERY ONE = “all members of a previously-mentioned group of at least three things (not people)”.

Diamonds are popular. Every one sells easily.

EVERY BODY = “all individual bodies without exceptions”.

.

EVERYTHING = “all things/aspects/ideas”.

Everything is clear.

EVERY THING = “all individual objects, emphasising lack of exceptions”.

Every thing on display was a gift.

.

NO-ONE/NOBODY = “no people”

No-one/Nobody came.

NO ONE = “not a single” (+ noun)

No one answer is right.

NO BODY = “no individual body”.

.

NOTHING = “zero”.

Nothing is impossible.

NO THING = “no individual object”.

There are other problem combinations besides those discussed here; hopefully these examples will make them easier to deal with.

As a living language, English is in a constant state of flux. This is quite clear when two words work their way into becoming one word.

Abovementioned is a good example, and yes, it’s one word. It started out in life as above-mentioned, but it’s no longer hyphenated and has become one word, just as its predecessor, aforementioned, did.

Other words have left their hyphens behind:

• Firsthand

• Halfway

• Interaction

• Smartphone

• Greenhouse

• Landline

• Videotape

• Handwrite

Some words are barely hanging on to their hyphens, depending on your stylebook, such as:

• Co-worker / Coworker

• Sub-category / Subcategory

• Bi-racial / Biracial

And there are words with the hyphen still decidedly in use:

• E-coli

• Mother-in-law

• Long-term

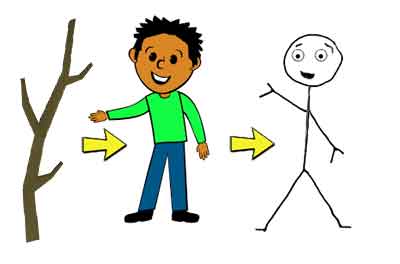

I would just love to tell you the rule about when and how and why two words can go from standing alone to being hyphenated to being one word, such as:

Problem is, there really isn’t a rule. Another aspect of a living language is that what is “correct” is only what is most commonly done. Think all you like that you shouldn’t split infinitives, but it’s no longer an “official” grammatical mistake.

So, while there’s no rule, there is a general trend, which is that the more people use a word, the less likely they are to hyphenate it. That’s why it’s email but e-commerce, and why decision-making is always hyphenated now, even though other such constructions, such as risk taking, muscle building, and drug seeking, are hyphenated only when they’re modifiers.

When it comes to spelling things with hyphens, people basically approach it like cooking asparagus: we do it until we get tired of it and decide it’s OK to stop. Some words may soon be headed for hyphenation:

• Bumper car

• Cell phone

• Conference call

And currently hyphenated words that may soon just be one word include:

• On-site

• Close-up

• Well-being

In better news, there are some groups of two-word / one-word terms that show a pattern, such as:

• Pick up / Pickup

• Make up / Makeup

• Get away / Getaway

• Set up / Setup

• Log in / Login

As you can see, in this group, two words are used when they are a verb + a preposition, and one word is used when it’s a noun.

• Mom’s going to pick up the kids in her pickup.

• Dad wants to make up with her, so he put on his makeup.

• See how I set up that gender-defying setup?

Another pattern shows up in:

• Some time / Sometime

• Any time / Anytime

• Some day / Someday

• Over time / Overtime

• Any one / Anyone

• Every day / Everyday

• No body / Nobody

If I have “some time,” then I have an amount of time, but I’m not telling you exactly how much time it is (e.g., an hour). “Sometime” takes the ball and runs with it, becoming a modifier that means “an unspecified time.”

• I have some time to talk.

• I’ll talk to you sometime.

The others in this group work the same:

• Their game has gotten better over time.

• They’re playing in overtime now.

and

• I have no body buried under my house!

• Oh, that dead guy? He’s nobody.

Our final group here is made up of the troublemakers that don’t really follow a pattern, such as:

• All together / Altogether

• All ready / Already

• May be / Maybe

• Can not / Cannot

These are two-words-made-one for all kinds of reasons, and as such must be learned on their own.

• All together is a modifier that means everyone is included in the action.

• Altogether is also a modifier, but it means “completely.”

• You guys are altogether crazy when you’re all together like this.

whereas

• All ready is a modifier that says something is completely prepared.

• Already is also a modifier, but it means that something has occurred in the past.

• We were already all ready to go an hour ago.

whereas

• May be is a verb.

• Maybe is a modifier indicating uncertainty.

• Maybe I should tell him that one day his children may be famous.

whereas

• Can not is a verb only to be used as an option for choosing not to do something.

• Cannot is a verb and the correct way to spell out “can’t.”

• I cannot explain to my cat I that can not feed her if I do not want to.

And then there’s one pair that’s really fiendish: a part and apart.

• A part is an article and then a noun.

• Apart is a modifier indicating separateness.

• Apart from all that nuisance with the bill, the mechanic stole a part from my car.

The reason this last one is so odd is that it didn’t actually do the a + part = apart dance that the others did. The “a” in “apart” is like the “a” in “asymptomatic” and “asexual,” meaning “not.”

• He’s a sexual guy.

• He’s asexual.

(Good idea not to mess up those two!)

So, while the English language bounces along, throwing out odd changes at its speakers’ whims, we can find some order in the chaos. But for some words, sorry, you just need to memorize them, or hire someone who does, like your friends at ProofreadingPal.

Julia H.

| It’s (one word or two words?) | Options |

·

Next Topic

|

Posted: Saturday, April 22, 2017 12:32:15 PM |

Rank: Advanced Member

Joined: 6/6/2013

Posts: 1,444

Neurons: 7,459

Do contractions count as one word or two?

Contracted words count as the number of words they would be if they were not contracted. For example,

isn’t, didn’t, I’m, I’ll are counted as two words (replacing is not, did not, I am, I will). Where the contraction

replaces one word (e.g. can’t for cannot), it is counted as one word.

Source: www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/248530-cambridge-english-proficiency-faqs.pdf

[image not available]

Source of the exercise (kids’ book): Family and Friends 1 by Naomi Simmons

Hi,

Can we say that according to the brown explanation «it’s» in my students’ books is considered two words and we should circle «it» and » ‘s » separately?

Thank you.

|

Posted: Saturday, April 22, 2017 12:47:54 PM |

Rank: Advanced Member

Joined: 9/19/2011

Posts: 19,178

Neurons: 95,408

The word, «it’s» is one word, but would be counted as two words because if not contracted, you would have two separate words. To circle the words, however, «it’s» would be one word and would be circled. Again, it is one word, but counted as two.

|

Posted: Saturday, April 22, 2017 12:54:02 PM |

Rank: Advanced Member

Joined: 6/6/2013

Posts: 1,444

Neurons: 7,459

Thank you but isn’t your answer in contrast with the brown explanation? The brown explanation regard it as two words. Doesn’t it?

|

Posted: Saturday, April 22, 2017 6:13:21 PM |

Rank: Advanced Member

Joined: 9/19/2011

Posts: 19,178

Neurons: 95,408

sb70012 wrote:

Thank you but isn’t your answer in contrast with the brown explanation? The brown explanation regard it as two words. Doesn’t it?

I think the confusion is in what you circle as a word. For example: the sentence «It’s my bike» would have only three words, but would count as four, according to the instructions. You would circle It’s…my…bike as the words in the sentence. You would not circle It and then circle (‘s) because the (‘s) is not a word.

«It’s» is one word, made up of two words. But because the «It’s» is made up of two words, it counts as two words.

The idea here seems to be simply illustrating how the words in a sentence can be reduced by using contractions. Without the contractions, there would be more words, so the «count» would increase. With contractions, the «count» decreases.

A common writing error occurs when students use the wrong version of a compound word or phrase. It’s important to know the difference between everyday and every day because these expressions have very different meanings.

Improve your writing by learning the differences between expressions that are very similar but that fill very different roles when it comes to sentence structure.

A Lot or Alot?

“A lot” is a two-word phrase meaning very much. This is an informal expression, so you shouldn’t use it “a lot” in your writing.

“Alot” is not a word, so you should never use it!

It’s a good idea to avoid this expression altogether in formal writing.

All Together or Altogether?

Altogether is an adverb meaning completely, entirely, wholly, or «considering everything.» It often modifies an adjective.

«All together» means as a group.

The meal was altogether pleasing, but I would not have served those dishes all together.

Everyday or Every Day?

The two-word expression “every day” is used as an adverb (modifies a verb like wear), to express how often something is done:

I wear a dress every day.

The word “everyday” is an adjective that means common or ordinary. It modifies a noun.

I was horrified when I realized I’d worn an everyday dress to the formal dance.

They served an everyday meal—nothing special.

Never Mind or Nevermind?

The word “nevermind” is often used in error for the two-word term “never mind.”

The phrase “never mind” is a two-word imperative meaning “please disregard” or “pay no attention to that.” This is the version you’ll use most often in your life.

Never mind that man behind the curtain.

All Right or Alright?

“Alright” is a word that appears in dictionaries, but it is a nonstandard version of “all right” and should not be used in formal writing.

To be safe, just use the two-word version.

Is everything all right in there?

Backup or Back Up?

There are many compound words that confuse us because they sound similar to a verb phrase. In general, the verb form usually consists of two words and the similar compound word version is a noun or adjective.

Verb: Please back up your work when using a word processor.

Adjective: Make a backup copy of your work.

Noun: Did you remember to make a backup?

Makeup or Make Up?

Verb: Make up your bed before you leave the house.

Adjective: Study for your makeup exam before you leave the house.

Noun: Apply your makeup before you leave the house.

Workout or Work Out?

Verb: I need to work out more often.

Adjective: I need to wear workout clothing when I go to the gym.

Noun: That jog gave me a good workout.

Pickup or Pick Up?

Verb: Please pick up your clothes.

Adjective: Don’t use a pickup line on me!

Noun: I’m driving my pickup to the mall.

Setup or Set Up?

Verb: You’ll have to set up the chairs for the puppet show.

Adjective: Unfortunately, there is no setup manual for a puppet show.

Noun: The setup will take you all day.

Wake-Up or Wake Up?

Verb: I could not wake up this morning.

Adjective: I should have asked for a wake-up call.

Noun: The accident was a good wake-up.

Have you ever read a document and seen the same words sometimes separate and sometimes combined? Or even sometimes with a hyphen? Some examples are the expressions cut off, cut out, clean up, follow up, and follow through. You might see these handled different ways, like this:

- They decided to cut off his funding.

- Did you apply by the cutoff date?

- When is the cutoff?

How can all of these be correct? The answer is in the dictionary—and in the way the word is used in the sentence. In the first example, cut off is a verb. Webster’s lists cut off as two words when it is used as a verb. In the second example, cutoff is an adjective being used to describe date, and in the third, cutoff is being used as a noun. Webster’s lists cutoff as the correct spelling when it is used as a noun or adjective.

Similar distinctions are true for clean up, follow up, and cut out, but be careful—they don’t all follow the same pattern.

For example:

- During a general cleanup [noun], you must clean up [verb] the mess.

- You can cut up [verb] a fish, but when you are done you have a cut-up [adjective] fish.

- However, nobody likes a cutup [noun].

- You can follow up [verb] a class by doing some reading, but during the follow-up [noun] don’t forget to make some follow-up [adjective] notes.

- If you follow through [verb] on your commitments, you will be commended for having good follow-through [noun].

These examples are from Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, but style guides may have different rules. If the adjective form is not in the dictionary, it should be hyphenated. Your best bet is to always look these up, in other words, to do a lookup, or make yourself a look-up list.

About the Author: Jennie Ruby is a veteran IconLogic trainer and author with titles such as «Essentials of Access 2000» and «Editing with MS Word 2003 and Adobe Acrobat 7» to her credit. Jennie specializes in electronic editing. At the American Psychological Association, she was manager of electronic publishing and manager of technical editing and journal production. Jennie has an M.A. from George Washington University and is a Certified Technical Trainer (Chauncey Group). She is a publishing professional with 20 years of experience in writing, editing and desktop publishing.

The comments to this entry are closed.