Continue Learning about English Language Arts

Can you end a sentence with the word then?

no u cannot end a sentence with the word then.

Both the question, and the above answer, end with the word

then…

Can you end a sentence with the word at?

A sentence can end with the word at,such as:Who are you looking at? Where is your head at?

Can you end a sentence with the word became?

a sentence with became

Can you end a sentence with the word also?

Yes.

«Either» is used at the end if the sentence is negative.

Can you end a sentence with the word of?

Not many sentences do, but you can try!

Hint: You can end a sentence with the words ‘heard of’

The words «were,» «we’re,» and «where» are easily confused because they have similar sounds and spellings. They are not homophones—words that have the same sounds or spellings—and their meanings and uses are quite different. «Were» (rhymes with «fur») is a past form of the verb «to be.» «We’re» (rhymes with «fear») is a contraction of «we are.» The adverb and conjunction «where» (rhymes with «hair») refers to a place.

How to Use Were

Use «were» as a past tense verb, as the:

- First-person plural of «be» (We «were» busy last week.)

- Second-person singular and plural of «be» (You «were» busy last week.)

- Third-person plural of «be» (They «were» busy last week.)

- Subjunctive of «be» for all persons (If I «were» you, I’d demand a raise.)

How to Use We’re

Since «we’re» is a contraction for «we are»—and in rarer cases «we were»—simply use «we’re» when you want to write or say a shorter version of the first-person plural pronoun «we» and to be verb «are.» The apostrophe replaces letter «a» (for «we are») or the letters «we» (for «we were, though that use is much less common). For example:

- «We’re» going back to work tomorrow.

In this sentence, which is perfectly acceptable English, you are saying: «We are» going back to work tomorrow.

How to Use Where

Use «where» as an adverb referring to a location, as in:

- I don’t know «where» you live.

Here, the writer is stating that she does not know «where» (at what place or location) the listener or reader lives. This word is also often used to start a question, such as:

- «Where» do you live?

In the sentence, the speaker is trying to find out at what location the listener or reader lives. Often, the person speaking (or even writing, as in a letter or email), is trying to find the exact address where the person resides.

How to Remember the Differences

To determine the difference between «were» and «we’re,» try substituting «we are» for the word. If it works, you know you can use «we’re.» If it doesn’t, you need «were.» For example, take the sentence:

- «We’re» going to the movies.

You could swap in «we are» for «we’re,» and the sentence still makes sense:

- «We are» going to the movies.

However, if you replace «were» for «we are,» the sentence does not work:

- «Were» going to the movies.

If you read the sentence aloud, your ear might tell you that the sentence lacks something. Indeed, it does: Since «were» is a past form of «to be,» you are lacking a subject. The sentence would work if you added in the word «we,» as in:

- We «were» going to the movies.

When trying to determine the difference between «were» and «we’re» versus «where,» remember that «were» and «we’re» are both «to be» verbs, or at least contain a «to be» verb; whereas, «where» always refers to a location. So, use the terms at the end of each sentence, as in:

- You live «were?» (This is the past form of «are.»)

- You live «we’re?» (This actually means: You live «we are?»)

Both of these uses don’t make sense. However, if you say:

- You live «where?»

That sentence works, because you are ending the sentence with the location word, «where.» To further clarify, swap out «where» with a location:

- You live in California?

- You live upstairs?

- You live in Europe?

- You live where?

Remember this trick, and you’ll never confuse «where» for «were» and «we’re.»

Examples

To understand examples, simply apply the above rules and tricks to create sentences making up a brief narrative.

- We’re going to Savannah for St. Patrick’s Day.

This sentence means «we are» going to a particular location, Savannah. The word «we’re» contains the subject of the sentence, «we,» as well as a verb «are.»

- But, we don’t know where we’ll be staying.

In this case, the term «where» refers to a location—or more specifically, the lack of a location. The writer/speaker does not know in what location his group will be staying.

- Last year we were forced to sleep in the van.

In this sentence, the speaker describes a past action—last year—when the group (sans a location to stay) had to sleep in a vehicle. The following sentence—and the end of this brief narrative—uses all three terms:

- We were lost in the middle of Timbuktu. No one knew where we were. Next time we travel, we’re going to bring along a map.

In the first bolded word, the group (in the past) was lost. Therefore, no one knew «where» (the location) we «were» (past tense of «are»). Switching to the present, the writer notes that in the future, «we’re» (we are) going to bring a map.

Sources

- » Common Errors in English Usage: Were / Were.» Washington State University.

- «Commonly Confused Word, were, we’re, where.» Online Writing Support/Townson University.

- Shrives, Craig. “Wear, Were, We’re, and Where.” The Difference between Wear, Were, We’re, and Where (Grammar Lesson). Grammar-monster.com.

THE USAGE OF ‘WAS’ AND ‘WERE’ WITH EXAMPLES

Let’s start from the beginning.

These are the past simple forms of the verb ‘to be’. Generally, ‘was’ is used with singular pronouns (one subject), and ‘were’ is used with plural pronouns (more than one subject), but the pronoun ‘you’ is an exception!

WAS is usually used with the pronouns ‘I’, ‘she’, ‘he’, and ‘it’.

WERE is usually used with pronouns ‘you’, ‘we’, and ‘they’.

(See the information just before and after ‘USE 2’ below, for more information about the use of the pronouns ‘you’ and ‘I’.)

[Tweet “WAS is usually used with the pronouns ‘I’, ‘she’, ‘he’, and ‘it’. “]

USE 1:

PAST SIMPLE

Some basic sentence examples:

- I was married for 5 years.

- She was unwell last week.

- It was not my fault!

- We were worried about the test results.

- They were busy working all day yesterday.

- You were supposed to help me.

However, there are exceptions to this rule!

Firstly, as I mentioned before, even though ‘you’ is a singular pronoun it is used with WERE.

- You were asleep when he rang.

- Where were you yesterday?

- Whom were you talking to?

[Tweet “WERE is usually used with pronouns ‘you’, ‘we’, and ‘they’.”]

USE 2:

PAST SUBJUNCTIVE AS A CONDITIONAL

Secondly, the pronoun ‘I’ can be used with WERE as a conditional as well as with WAS. WERE is the past subjunctive of the present verb ‘to be’, meaning it expresses hope, possibility or supposition rather than stating a fact.

- If I were you, I wouldn’t touch that.

(I’m not you, it’s hypothetical – used for the present or future)

- If I were a multi-billionaire, I would rid the world of poverty.

(I’m not a multi-billionaire, it’s hypothetical – used for the present or future)

- If I were in his shoes, I would accept their offer.

(I’m not him or in his position, it’s hypothetical – used for the present and future)

- If I was rude to you yesterday, I’m very sorry.

(The condition is unclear, but it is presumed to have been true in the past)

- If I was annoying you last night, I’m sorry. I was in a bad mood.

(The condition is unclear, but it is presumed to have been true in the past)

- If I was healthier, I probably would have been able to win the race.

(The condition is unclear, but it is presumed to have been a possibility of being true in the past)

Read more:

If I Was or If I Were?

PAST CONTINUOUS / PAST SIMPLE

Remember that in Past Simple, a specific time is used to show when an action began or finished. In Past Continuous (Progressive), a specific time only interrupts the action.

USE 3:

INTERRUPTED ACTION IN THE PAST

[subject 1 + WAS/WERE + verb+ing + WHEN + subject 2 + past simple verb]

Use Past Continuous to indicate when a longer action in the past was interrupted, usually by a shorter action that occurs (Past Simple).

Here are some examples:

- She was studying when he called.

- He was cooking when the phone rang.

- They were shopping when they heard an explosion.

- We were dancing when the power went out.

- I was listening to music when the doorbell rang.

Read more:

How to use IS, WAS, THAT, THE!

USE 4:

SPECIFIC TIME AS AN INTERRUPTION

Similar to USE 1 above, however you can use a specific time as an interruption.

- At 3am last night, I was studying.

- Last night at 8pm, we were watching a movie.

- Yesterday at this time, I was sitting in my office.

USE 5:

DESCRIBING PARALLEL ACTIONS

You can use the Past Continuous to describe two parallel actions in one sentence. It expresses the idea that they were happening at the same time.

- I was cooking while he was playing with the baby.

- While Eleanor was studying, Toby was cooking a meal for them.

- I wasn’t paying attention when he was talking to me, so I don’t remember everything he said.

Read more:

Subjunctive “I Wish I Were” [Infographic]

USE 6:

A SERIES OF PARALLEL ACTIONS

A series of parallel actions can be used to describe the atmosphere at a particular time in the past.

- When I walked into my house, my husband was watching TV, the baby was crying, my son was playing computer games, and the dog was barking in the garden!

- When I stepped into the office, my boss was shouting at someone on the phone, his secretary was running towards his office, my assistant was printing a document, and all the telephones were constantly ringing!

USE 7:

REACTION OF A SUBJECT

[Subject + WAS/WERE + adjective + at/by/with + noun]

Used to show the reaction of a subject towards a noun.

- I was amazed at how clean the house was!

- We were surprised by their eagerness to help us.

- She was very happy with her new car.

USE 8:

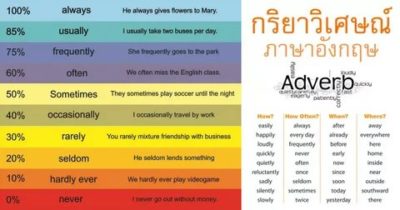

ADVERBS OF FREQUENCY

The Past Continuous is used with adverbs of frequency such as ‘always’ or ‘constantly’ to express that something happened often in the past. Note: This does not apply to all the adverbs of time.

[Subject + WAS/WERE + adverb of time + verb+ing]

- He was always buying me flowers.

- She was constantly talking throughout my lessons.

- They were always sitting next to each other in class.

- She was usually sitting in the garden on a Friday.

- I was continuously exceeding expectations.

Read more:

How To Use The Passive Voice With Helpful Examples

USE 9:

WHILE VS WHEN

Dependent clauses are groups of words which have meaning but aren’t complete sentences. Some clauses can start with the word ‘when’ and others can start with the word ‘while’ (Note: This does not apply to all dependent clauses). When you talk about things in the past, ‘when’ is usually followed by the Past Simple verb, whereas ‘while is followed by the Past Continuous verb. They have similar meanings but

When you talk about things in the past, ‘when’ is usually followed by the Past Simple verb, whereas ‘while is followed by the Past Continuous verb. They have similar meanings but emphasize different parts of a sentence.

Here are some examples:

- I was studying when the doorbell rang.

- While I was studying, the doorbell rang.

- She was cooking when her friends arrived.

- While she was cooking, her friends arrived.

USE 10:

ADVERBS OF TIME PLACEMENT

Adverbs of time can be added to sentences in the Past Continuous tense. You can use adverbs such as always, never, ever, only, still, just, etc. Here are some examples to show you the placement for adverbs:

- Weren’t you ever listening to what I said?

- You were never listening to anything I said.

- Was she always telling you off?

- She was always telling you off.

- He was still shouting as she walked away.

- Was he still shouting as she walked away?

USE 11:

ACTIVE AND PASSIVE

Sentences can be active or passive. Most sentences are active, where the subject is doing the action and the object is receiving the action. The subject and object can be swapped around to change a sentence from active to passive.

Active – The professor was teaching his students.

Passive – The students were being taught by the professor.

Active – Jenny was making tea for her friends.

Passive – Tea was being made by Jenny for her friends.

Active – Her brother was hugging her.

Passive – She was being hugged by her brother.

USE 12:

USING A SPECIFIC PERIOD OF TIME

You can describe the state of a noun at a particular time in the past.

[Subject + WAS/WERE + time period]

- I was only 16 when I started working full-time.

- Why were you being horrible to me last week?

- I was just a paperboy before I became CEO of the New York Times.

Read more:

When to Use THIS and THAT in English?

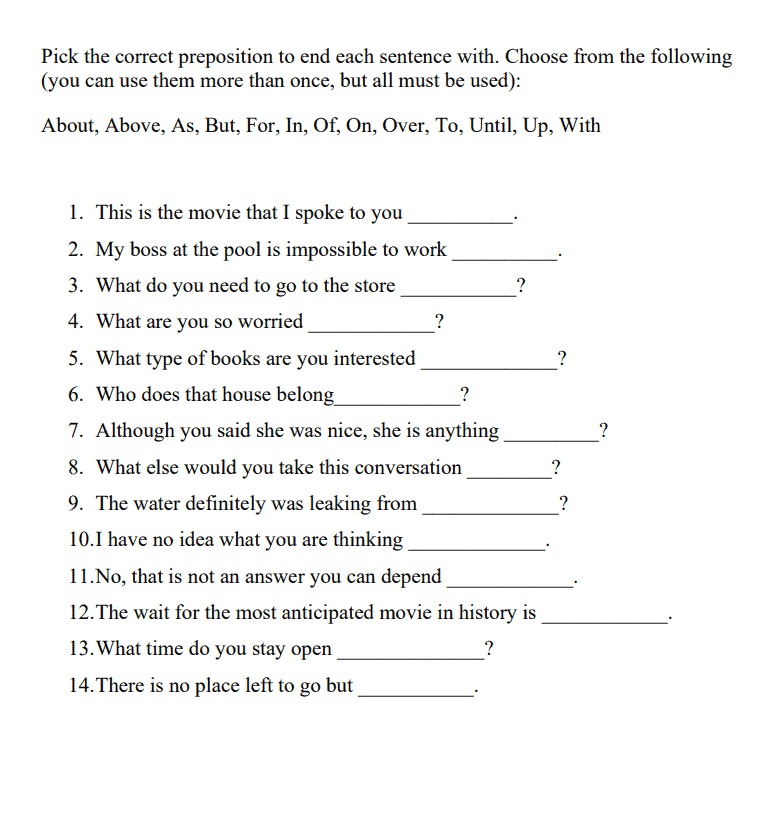

You’ve probably heard that you can never, under any circumstances, use a preposition at the end of a sentence. However, there are plenty of opportunities to use a preposition in this manner, and if it makes your sentence sound more natural, it is absolutely acceptable.

Below we review what a preposition is, how it can be used, when it is acceptable to end a sentence with one, and how to make corrections when it may be frowned upon. Use these rules and examples to ensure your writing is clear and concise.

Can I End a Sentence With a Preposition?

Ending a sentence with a preposition is acceptable during informal writing and casual conversation. It is frowned upon when used in a formal context or when the preposition is missing an object.

What is a Preposition?

A preposition is a word or group of words that show direction, time, location, place, spatial relationships, or introduce an object. They are relationship words used before a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun and are crucial for effective communication.

There are over a hundred prepositions you can take advantage of, but the most common are those we use in everyday speech and writing. Frequently used prepositions include:

| about | above | across |

| after | against | along |

| among | around | as |

| at | before | behind |

| between | but | by |

| during | except | for |

| from | in | like |

| next to | of | off |

| on | over | past |

| than | through | to |

| until | up | with |

Ending a Sentence With a Preposition: When You Can and When You Can’t

There are various instances when you can and can’t use prepositions at the end of a sentence. We use them more often in speech than in writing due to the higher instances of casual conversation we involve ourselves with (see what I did there?). But, it is entirely acceptable to use them in writing as well to create an informal tone.

However, avoid them during formal instances, and make sure you present your words properly.

When to End a Sentence With a Preposition

There are many opportunities to use a preposition at the end of a sentence. The phrasing of these sentences is generally more conversational and, therefore, much more relaxed.

In Informal Conversation and Writing

Informal settings allow for prepositional endings in conversation and writing. You most likely already do it when speaking to friends and family or in a casual atmosphere. It might also sound awkward not to use a preposition at the end, making it acceptable in this scenario as well.

For Example:

- Who are you talking about?

- I have no idea what I’m hungry for. Vs. I have no idea for what I’m hungry.

If the Preposition Is Part of an Informal Phrase

When the preposition is included in an informal phrase at the end of a sentence, its use is also acceptable.

For Example:

- Six excited preschoolers were almost too much to put up with.

When an Idiom or Colloquialism Ends a Sentence

Some idioms and colloquialisms end in prepositions, and if you use them in sentences, they are appropriate to place at the end as well.

For Example:

- A good mechanic is hard to come by.

When NOT to End a Sentence With a Preposition

When speaking or writing to people you may not know for work or school assignments, it is best to take a more formal approach and avoid end of sentence prepositional use. When proofreading and editing these types of examples, consider moving prepositions within the sentences.

In Formal Writing

The audience usually determines formal writing. If you are writing for work, an event, or to people you want to communicate clearly and concisely to, avoid the informal tone suggested with the placement of prepositions at the end of a sentence.

For Example:

- The early Triassic is the era on which I’m focused. Vs. the early Triassic is the area I’m focused on.

- Romantic literature is a subject about which Ruby knows nothing. Vs. Romantic literature is a subject Ruby knows nothing about.

Prepositions and the Passive Voice

A passive voice in writing occurs when you might not know the subject of a sentence, or who is performing an action. It ends in a preposition and is easy to correct. However, there is nothing wrong with using it, even though traditional grammarians consider it a no-no. Just be sure that you have no other way to clarify the sentence without it sounding awkward.

For Example:

- The game has been called off. Vs. The game was rescheduled.

- The issue was dealt with. Vs. The boss dealt with the issue.

Unnecessary Prepositions

Sometimes, sentences end with a preposition because too many are in the sentence. These are easy to edit for clarity and to help avoid wordiness.

For Example:

- The whites and colored laundry need to be separated out. Vs. The whites and colored laundry need to be separated.

- Sanna is confused about where she is going to. Vs. Sanna is confused about where she is going.

Examples of Using Prepositions at the End of Sentences

As with many grammar and usage rules, the question of whether or not to end sentences with prepositions is ultimately a matter of taste.

These arbitrary rules have never hampered great writers and influencers, and sentence-ending prepositions can be found in some of the most beautiful writing in the English language.

Ending a Sentence With “Is”

- Winning isn’t everything, but wanting to win is. [Vince Lombardi]

Ending a Sentence with “On”

- When you reach the end of your rope, tie a knot in it and hang on. [Franklin D. Roosevelt]

- In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on. [Robert Frost]

Ending a Sentence With “Up”

- Many of life’s failures are people who did not realize how close they were to success when they gave up. [Thomas A. Edison]

Ending a Sentence With “With”

- Finn the Red-Handed had stolen a skillet and a quantity of half-cured leaf tobacco, and had also brought a few corn-cobs to make pipes with. [Mark Twain]

Ending a Sentences With “To”

- There was a little money left, but to Mrs. Bart, it seemed worse than nothing the mere mockery of what she was entitled to. [Edith Wharton]

- It’s funny. All one has to do is say something nobody understands and they’ll do practically anything you want them to. [J D Salinger]

Ending a Sentence With “Of”

- Mr. Barsad saw losing cards in it that Sydney Carton knew nothing of. [Charles Dickens]

Ending a Sentence With “For”

- Then she remembered what she had been waiting for. [James Joyce]

- There is some good in this world, and it’s worth fighting for. [J.RR. Tolkein]

Ending a Sentence With “Out”

- Time, which sees all things, has found you out. [Oedipus]

- Things work out best for those who make the best of how things work out. [John Wooden]

Ending a Sentence with “Over”

- For you, a thousand times over. [Khaled Hosseini]

Let’s Review and a Worksheet to Download

Although we use many prepositions in everyday language, some of the most common ones make their way to the end of a sentence. This use is often casual and works to help a sentence flow. However, you want to avoid their use in formal settings if you can. Also, look for unnecessary use even in an informal situation, and correct the sentence for clarity.

Unlike some other languages, we build much of the meaning of a sentence in English through the use of word order in that sentence. So, can you end a sentence with the verb “is”?

Yes, we can end a sentence with “is,” such as when we confirm that something is the case by saying, “It is.” Specific rules govern English sentence word order, but there is no rule stating that a sentence may not end with the verb “is” or with any other verb for that matter.

This article will examine some rules and conventions regarding the order of words in a sentence. You will see that ending a sentence with a verb such as “is” or any variation of the verb “to be” is perfectly acceptable in modern English. Any caution against this practice is more a question of style than of proper English usage.

Yes, you can certainly end a sentence with a verb. Some verbs can even form one-word sentences with an implied subject. For example: Come! Hurry! Don’t! Sometimes, a simple predicate can be a verb on its own.

Word order refers to how we arrange words in sentences. Most sentences start with a subject and continue with something that we say about the subject. This divides the sentence into two parts: the subject and the predicate, usually comprising the verb plus an object.

You can also end sentences with intransitive verbs that do not require an object. For example, “I coughed” and “The plane crashed” include intransitive verbs that do not need a direct object.

However, in place of the direct object, we may answer the question “where?” “when?” “how?” or “how long?” For example, “I coughed all night” and “The plane crashed into the building.”

Can You End a Sentence With “Is”?

Word order plays an important part in determining syntax and whether, for example, one may end a sentence in formal writing with a verb or, more specifically, with the verb “to be.” Since “is” is a form of “to be,” can you end a question with “is”?

Indicating State or Location

Having reviewed the basic structure of a sentence, let’s see how and when word order starts to change and how “is” ends up at the end of a sentence. Here are some examples where “is” indicates existence:

- I have no idea where your jacket is.

- I didn’t think there was a solution, but there is.

- I’m not sure who is faster on the track, but I think Jack is.

- I can’t see what the problem is.

Can You End a Question With Is?

Another common occasion is when we change a direct question to an indirect question. Take this example of a simple statement:

- John has a tree in his yard.

If we formed a direct question — one of many possible questions — from this statement, we might ask, “Where is John’s tree?” But an indirect question would change the word order to “Can you tell me where John’s tree is?” Indirect questions can end with is.

However, it would be syntactically incorrect to say, “Can you tell me where is John’s tree?” This word order may be accepted in certain colloquial or spoken settings, but, strictly speaking, it is incorrect.

We can also use “is” at the end of a short reply to a question. For example:

Q: Who is going next?

A: He is.

Ending a Sentence with Forms of the Verb “To Be”

| Present | Past |

|---|---|

| I am | I was |

| You are | You were |

| He/she/it is | He/she/it was |

| We are | We were |

| You are | You were |

| They are | They were |

| Present participle: I am being, etc. | Past participle: I have been, etc. |

Be-verbs like “is” can be tricky since they most often function as linking verbs, connecting a predicate nominative or predicate adjective to the subject. However, we can also use be-verbs as main verbs indicating existence.

For the purposes of this article, we are referring to any and all of these forms of the verb “to be” when we use them at the end of a sentence (source).

As for sentences ending with a verb form of “to be” in the existential sense, there are numerous famous examples in published literature.

- In philosophy: I think, therefore I am. (René Descartes, 1595–1650)

- In Shakespeare: To be, or not to be…. (Hamlet, c.1600)

To be perfectly accurate, although we all recognize the quotation, Shakespeare didn’t technically end his sentence there so much as introduce a brief pause, but he could have stopped there (source). He was using “be” as a synonym for “exist,” which functions as a main verb.

For more on be-verbs, make sure you read our article, “I’m or I Am: Similarities and Differences in Usage.”

Basic Word Order in English

The fundamental building blocks of English sentence structure are therefore S-V-O, which stands for Subject-Verb-Object. In a simple sentence, the “subject” is the initiator of some action, represented by the verb, which impacts upon the object of the action. For example:

- John climbs the tree.

In this sentence, the subject John performs the action (climbs) on the direct object (the tree). The subject is typically a noun or pronoun, which is a person, place, or thing. The verb is the action or “doing word,” and the object is the word or group of words influenced by the action.

The Importance of Word Order in English

In journalism, the headline “Man Bites Dog!” is far more likely to sell newspapers than a similar headline proclaiming that a dog had bitten a man. The former is an unusual event likely to attract a reader’s attention; the latter, not so much.

This is just one illustration that the order in which we place words in English sometimes dramatically influences the meaning and impact of what we say (source).

In the same way, “The tree climbs John” would make no sense at all. Other languages follow a different word order, such as S-O-V in Tamil. They would say:

- John the tree climbs.

Arabic has a V-S-O structure, like this:

- Climbs John the tree.

In some of the ancient languages, such as Greek and Latin, word order in a sentence is largely immaterial because word endings determine the function of a word in a sentence.

This alteration of word endings to indicate function is called inflection. Modern German is still quite an inflected language. Still, as Leslie Dunton-Downer says in her entertaining look at how English continues to evolve:

Indeed, having lost so much inflection, Modern English relies heavily on word order to convey grammatical information. And it doesn’t much like having its conventional word order upset.

Dunton-Downer, L. (2010). The English is Coming! How One Language Is Sweeping the World. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Naturally, students studying English from a different language structure may find English word order, also called syntax, confusing at first.

Types of Sentences

We can classify simple sentences as statements, questions, or commands. A statement might be, “John climbs the tree in his garden,” while a question could be, “Did you see John climbing the tree in his garden?” And a command might be, “John, do not climb the tree in the garden.”

Notice that in all of these different types of sentences, the word order remains much the same as in the simple sentence, although some of the word endings might change.

Complex and Compound Sentences

As the names imply, these sentences follow a similar word order to the simple sentence but become more complex in the amount of information that they impart.

In complex sentences, we are essentially joining two simple sentences (or independent clauses) together using a conjunction, and in compound sentences, we are adding one or more dependent clauses to an independent clause (source).

Complex and compound sentences allow for more variety in our writing. Word order, however, still usually follows the pattern of S-V-O.

“Is” is not the only verb that may end a sentence; there are many other examples. This is typically so in the case of wh-questions — “what,” “where,” “why,” “who,” “when.” So, for example, if we start with a simple statement such as:

- The girls (S) watched (V) some movies (O).

We may ask inquisitively:

- What (O) did (V) the girls (S) watch (V)?

We could move the object “what” to follow the verb “watched”: “The girls watched what?” The above statement/question pairing shows that the normal word order S-V-O changes quite naturally into the question with the word order of O-V-S-V, with the verb now at the end of the sentence (source).

Common Objections to Ending a Sentence with a Verb

We can also characterize writing style as more or less formal. Formal writing style follows certain quite well-established conventions. In selecting an appropriate style, the writer must be aware of the intended purpose of the text, the audience for whom they are writing, and the appropriateness of the style to the subject matter.

Some sources will warn “good writers” to avoid ending a sentence with a verb. Still, as we’ve already mentioned, this is more a question of writing style than of correct grammar or syntax.

The reasons some give for avoiding verb endings usually refer to the sentence being otherwise “top-heavy,” “imbalanced,” or undesirable by virtue of the verb not being situated as close to the subject of the sentence as possible.

Some will object to be-verbs at the end of a sentence, but we’ve already demonstrated that be-verbs can also function as main verbs.

You may also witness someone cite the misguided warning against ending a sentence with a preposition as a reason not to end a sentence with a verb “is.” This is doubly misguided because (a) there is nothing wrong with ending a sentence with a preposition, and (b) “is” is not a preposition to begin with.

How justified are these other warnings? Is “The children are swimming” any less clear than “The children are taking a swim”?

“Swimming” is the gerund form of the verb “to swim,” a gerund being a verb ending in -ing that acts as a noun. In answer to the question, we might argue that “swimming” is the shorter and more commonly used expression compared to “taking a swim” and is, therefore, preferable.

Here’s another example of a sentence ending with a verb:

- Chimpanzees are far more intelligent than experts originally thought.

Strategies for Avoiding These Endings

If you still feel the need to avoid ending a sentence with a verb, we could turn this into the passive voice:

- Chimpanzees are far more intelligent than originally thought by experts.

But who would feel the necessity for making that change, and aren’t we supposed to avoid the passive voice where possible, too? The following is a case in point:

- Several experiments (S) were performed (V).

This sentence ending in a verb is also in the passive voice, and although we’re not told who performed the experiments, we may assume it was a bunch of students or laboratory technicians or such-like. Still, this sentence would be better written in the standard active voice, as follows:

The students (S) performed (V) several experiments (O).

Alternatively, any sentence ending in a verb can often be “balanced,” if at all necessary, by adding a bit of additional clarifying information; for example:

- Additional add-on components (S) can be bought (V).

We can “improve” this verb-ending sentence either by turning it into the active voice, “You can buy additional add-on components,” or by adding some further information, “Additional add-on components can be bought at all leading software stores.” This article was written for strategiesforparents.com.

But as should be clear by now, under most conditions and circumstances, there really is no need to avoid ending a sentence with a verb.

Final Thoughts

There is no rule stating that a sentence may not end with a verb or with any form of the verb “to be.” On the contrary, many sentences and well-known expressions do end with the verb “is.” This is one “fake rule” that you can happily ignore.

There are rules in English governing sentence structure to convey the true sense of what one is trying to communicate. The order in which words appear in the sentence, and not the word endings, determines some of this meaning.

Ending a sentence with a preposition (such as with, of, and to) is permissible in the English language. It seems that the idea that this should be avoided originated with writers Joshua Poole and John Dryden, who were trying to align the language with Latin, but there is no reason to suggest ending a sentence with a preposition is wrong. Nonetheless, the idea that it is a rule is still held by many.

When one looks back over the glorious and bloodstained history of grammar and usage wars, it quickly becomes apparent that many of the things which got our ancestors in a swivet no longer bother us very much. George Fox, the founder of the Religious Society of Friends, was so upset that people were using you (instead of thou) to address a single person that in 1660 he wrote an entire book about it. «Is he not a Novice,» Fox wrote, «and Unmannerly, and an Ideot, and a Fool, that speaks You to one, which is not to be spoken to a singular, but to many?» The rest of us have pretty much moved on.

In regard to the rule against ending a sentence with a preposition, Churchill is famous for saying «This is the sort of nonsense up with which I will not put.» However, it’s unlikely that he ever said such a thing.

And then there are some prohibitions which have a curiously tenacious ability to stick around (such as not beginning a sentence with and), in defiance of common sense, grammar experts, and the way that actual people use the English language. Perhaps the most notable example of such is the rule against ending a sentence with a preposition (also known as preposition stranding, or sentence-terminal prepositions, for those of you who would like to impress/alienate your friends).

Where did this rule come from?

There is some disagreement as to how we came to cluck our tongues at people who finish off their sentences with an of, to, or through, but it is agreed that it’s been bothering people for a very long time. Many people believe that the rule originated with the 17th century poet John Dryden, who in 1672 chastised Ben Jonson: «The preposition in the end of the sentence; a common fault with him.” Jonson probably didn’t take much heed of this admonition, seeing as how he was dead, but untold millions of people have suffered in the subsequent years as a result.

Nuria Yáñez-Bouza has proposed an alternate theory: she discovered that, several decades prior to Dryden, an obscure grammarian named Joshua Poole took a similar position in his book The English Accidence. Poole was more concerned with prepositions being placed in «their naturall order,» and did not mention the end of the sentence as specifically as Dryden did.

If we are to be fair we may credit Poole for creating the rule, and Dryden for popularizing it. Both Dryden and Poole were likely motivated by a desire to make English grammar more in line with Latin, a language in which sentences syntactically cannot end in prepositions.

In the 18th century, a number of people who liked telling other people that they were wrong decided Dryden was correct and began advising against the terminal preposition. Sometimes, the advice was to not end a sentence with a preposition. At other times it was more general, as Poole’s rule was. For instance, Noah Webster, in his 1784 book on grammar, took care to advise against separating prepositions «from the words which they govern.» He did allow that «grammarians seem to allow of this mode of expression in conversation and familiar writings, but it is generally considered inelegant, and in the grave and sublime styles, is certainly inadmissible.»

However, by the time the 20th century rolled around most grammar and usage guides had come to the conclusion that there was really nothing wrong with terminal prepositions. In fact, there has been, for about 100 years now, near unanimity in this regard from usage guides. The matter must therefore be settled, mustn’t it?

No, it must not. A quick look at newspapers from the past year indicates that there are still a number of people who find the terminal preposition an abomination, enough so that they are willing—perhaps, one imagines, even eager—to write letters to the editor of any newspaper in which they find it.

Why do both editorial and letter writers have to flagrantly split the infinitive? And lastly, ending a sentence with a preposition is something we can do without!

— letter to Daily Camera (Boulder, CO), 17 February 2016I would think a State Columnist would know correct English, unless this was done to get people’s attention. It sure got mine. The first sentence of the second paragraph, «Here’s where we’re at». Really…No sentence should end in a preposition. It should be, «Here’s where we are». If it wasn’t done on purpose, I would suggest Patrick go back to English Grammar 101 before he writes his next column.

— letter to Asheville (NC) Citizen-Times, 15 February 2016Conventional wisdom would figure that a Canadian citizen is a Canadian, regardless of status. Plus, you’re not supposed to end a sentence with a preposition.

— The Star Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan), 25 September 2015

It would appear that some people are determined to hold on to this rule, no matter how many times they are informed that it really isn’t one. In a similar vein, many people who like to use terminal prepositions will give some mangled version of a quote from Winston Churchill, «This is the sort of nonsense up with which I will not put.» The linguist Ben Zimmer has conclusively demonstrated that, as is the case with so many Churchill quotes, this was almost certainly never said by him.

If you don’t like to end your sentences with prepositions, you don’t have to—just don’t say that it is a rule. And if you like to end your sentences with a succinct with, go right ahead and keep doing so—just don’t quote Winston Churchill when someone says that you shouldn’t.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

предложение словом

предложение со слов

фразу словом

предложение со слова «

I’m sure you know somebody who can’t say anything about any idea, plan, or activity without crutching the sentence with the word but.

Уверен, вы знаете людей, которые не могут говорить об идее, плане или деятельности, не испортив предложение словом «но».

He started a sentence with the word «atomic» or «nuclear» and then randomly chose words from the auto-complete suggestions.

«Я начинал предложение со слов «ядерный» или «атомный» и потом выбирал одно из автоматически предложенных вариантов.

Do not start a sentence with the word «but».

He just started every sentence with the word atomic or nuclear and gave the phone to fill in the rest.

Он просто начинал каждое предложение со слова «атомный» или «ядерный» и давал телефону заполнить остальное.

I made up a sentence with the word that I had just learned.

Starting a sentence with the word «you» almost guarantees a non-productive conversation.

Начинать фразу со слова «ты» — верный путь к непродуктивному разговору.

You don’t need to finish every sentence with the word «sir.»

You should avoid beginning a sentence with the word «also.»

You should avoid beginning a sentence with the word «also.»

It is grammatically incorrect to end a sentence with the word «and,» but I get so upset when I think about Ike.

Грамматически неправильно заканчивать фразу словом «и», но я так расстраиваюсь при мысли об Айке.

Insert a period after C, delete whereas and begin new sentence with the word Domestic.

Mr. de GOUTTES wondered whether it was necessary to introduce the second sentence with the word «Nevertheless».

Mr. Lallah suggested replacing the words «as to» in the third sentence with the word «affirming» rather than «stressing» or «suggesting».

Г-н Лаллах предлагает заменить в третьем предложении выражение «что касается» словом «подтверждая» вместо слов «подчеркивая» или «предполагая».

The United Nations Appeals Tribunal, by its decision of 10 October 2011, decided to adopt an amendment to article 5, paragraph 1, by replacing the word «two» in the second sentence with the word «three».

В своем решении от 10 октября 2011 года Апелляционный трибунал Организации Объединенных Наций постановил принять поправку к пункту 1 статьи 5, заменив во втором предложении слово «две» словом «три».

There are two reasons why a writer would end a sentence with the word «stop» written entirely in

СУЩЕСТВУЕТ две причины, почему писателю может захотеться закончить фразу словом «точка», написанным целиком заглавными буквами (ТОЧКА).

And it’s incredibly more for the control group that did the sentences without money and way less not only for the people who unscrambled the sentence with the word salary but also way less if they saw Monopoly money in the corner.

Большинство из контрольной группы, получившие предложения без упоминания денег, гораздо реже из людей, получивших предложение с упоминанием зарплаты, и даже люди, с деньгами из монополии, реже обращались за помощью.

Ok, Ferrari CEO Louis Camilleri implicitly stated that he does not intend to listen to «that word» in the very same sentence with the word Ferrari.

Во время презентации в прошлом году, генеральный директор Ferrari Луи Кэри Камиллери заявил, что не хочет слышать это слово «в той же фразе, в которой есть Ferrari».

Результатов: 17. Точных совпадений: 17. Затраченное время: 49 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Adverbs in English sentences. Where do they belong?

Adverbs are words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, or phrases. They often answer the question «How?» (How?). For example:

She sings beautifully.

She sings beautifully. (How does she sing? Beautifully.)

He runs very Fast.

He runs very fast. (How fast does he run? Very fast.)

I occasionally practice speaking English.

From time to time I practice conversational English. (How often do I practice? From time to time.)

The place occupied by an adverb in an English sentence depends on what type this adverb belongs to. It is in this aspect that we will understand in today’s English lesson.

1. Do not put an adverb between the verb and the object of its action

In the next sentence painted is a verb and the house — an object. carefullyas you might have guessed — this is an adverb.

I Carefully painted the house. = Correctly

I painted the house Carefully. = Correctly

I painted Carefully the house. = Wrong

Here’s another example. In this sentence read Is a verb, a book Is the object of action, and Sometimes — adverb.

I Sometimes read a book before bed. = Correctly

Sometimes I read a book before bed. = Correctly

I read a book before bed Sometimes. = Acceptable, but only in informal situations

I read Sometimes a book before bed. = Wrong

Front position: at the beginning of a sentence

suddenly the phone rank.

Suddenly the phone rang.

fortunately, no one was injured.

Fortunately, no one was hurt.

Maybe I’ll go for a walk.

Maybe I’ll go for a walk.

Mid position: next to the main verb

I always exercise before work.

I always do my exercises before work.

They have Completely forgotten about our appointment.

They completely forgot about our meeting.

He was probably late for the interview.

He was probably late for the interview.

She slowly began to recover from her illness.

She slowly began to recover from her illness.

End position: at the end of a sentence

You speak English well.

You speak English well.

Please sit there.

Please sit here.

They ate dinner quietly.

They dined quietly.

Mode of action adverbs

quickly, slowly, easily, happily, well, * badly, seriously

The position in the middle of the sentence makes the adverb less expressive:

He quickly corrected his mistake.

He quickly corrected his mistake.

She easily passed the test.

She passed the test easily.

We happily

Source: https://english-bird.ru/position-of-adverbs/

Present simple — educational rules and examples

The English language has an extensive system of tenses. One of the most commonly used variations is the present simple tense. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at everything related to this temporary form, including education, rules and examples of the present simple, as well as special use cases.

Definition and use

This time covers a fairly long period of time. It does not indicate the duration of the action or its completeness, for example, as a perfect time. Present Simple describes the process as such. So, the present simple rule says that this temporary form is used in the following cases:

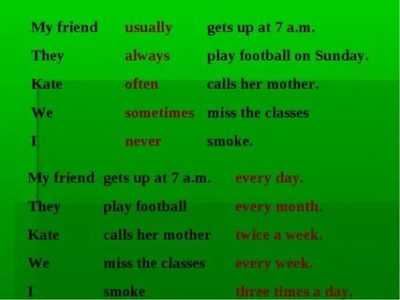

1. When the speaker communicates about regularly repeated actions, habits, patterns. Often, such sentences are accompanied by satellite adverbs. These include: usually (usually), every month / day / week / (every month / day / week), always (always), seldom (rarely), often (often), daily (daily), etc.

Example: He always wakes up at 6 am — He always wakes up at 6 am.

I often visit my parents. — I often visit my parents.

They never go to clubs. — They never go to clubs.

2. Schedules and work schedules also use time in English, present simple.

The train arrives at 7 am — The train arrives at 7 am.

The theater works till 11 pm — The theater is open until 11 pm.

3. When all known truths, facts, statements, stereotypes are mentioned.

Example: Io is Jupiter’s satellite. — Io is a satellite of Jupiter.

Boys love cars. — Boys love cars.

Winter comes after autumn. — After autumn comes winter.

4. When mentioning the present action without linking it to a specific moment of speech.

For example: His grandpa lives in Australia. — His grandfather lives in Australia.

Lila learns chemistry. — Leela is studying chemistry.

5. When narrating. When the speaker is leading a story, communicating someone’s actions.

My husband wakes up at 5 am, has his breakfast, gets dressed, and goes to work. — My husband wakes up at 5 o’clock in the morning, has breakfast, gets dressed and goes to work.

6. Present Indefinite time is also used to compose instructions, manuals, recipes (often in the imperative mood).

Take two eggs, add a glass of water, and cook it for 20 minutes. — Take two eggs, add a glass of water and cook for 20 minutes.

7. Commentators also use Present Simple in their speech.

Arshavin takes the ball and gets it to the box. — Arshavin takes the ball and sends it to the penalty area.

8. When mentioning planned events taking place in the future. In this case, such a temporary form is used contrary to the rules of the future tense to emphasize the planned action.

He arrives next week. — He’s coming next week.

9. Newspaper headlines are used instead of past tense to avoid bulky headlines

Russia Launches A New Satellite. — Russia is launching a new satellite.

Time Education Present Simple

The present indefinite time has one of the simplest forms of education. When using Present Indefinite, no one should have any difficulties. To understand everything about the formation of the present simple, let us single out 3 subparagraphs for a separate consideration of the affirmative, negative, and interrogative forms of this tense.

Statement

The affirmative form present simple has direct word order.

In the first place is the subject (Subject), followed by the predicate (Verb) in the desired form, the third place is taken by the additional members of the sentence.

When forming the affirmative form Present Simple, it is necessary to put the infinitive without the particle to (V1) in the desired form. The endings -s, -es are added to the 3rd person singular, that is, to he / she / it, as well as to all nouns that are replaced by these pronouns. For example,

I go to theater every month. — I go to the theater every month.

Source: https://lim-english.com/pravila-anglijskogo-yazyka/present-simple/

Present Simple marker words: definition, rules and examples

“Time markers” are words that make it possible to determine that the sentence should use the present Simple temporal form. Let’s see how this works, taking the example of Present Simple marker words.

Present Simple time

One of the first topics when learning English grammar is Present Simple. This is the Simple Present Tense, which applies in the following cases:

- to indicate a state, habitual, repetitive action;

- to describe scientific facts, accepted statements, common truths, laws of nature;

- when listing the following one after another actions;

- practical guides, operating instructions, instructions;

- various schedules (trains, buses, cinema sessions, etc.);

- newspaper headlines;

The English language itself helps to understand all cases of using the temporary form of Present Simple. He may suggest special signals — time indicators.

What are time markers

The verbs in the sentence describe actions and events, and they unfold in time. Therefore, the verb itself is directly related to temporary circumstances: when the event took place, how long it lasted, by what moment it ended, etc.

Tense circumstances are not accidental in sentences: they serve as indicators for different verb forms. Such pointers are called temporary markers. For each time in the English language, its own set of indicators is allocated, including Present Simple markers.

If you master the verbal indicators, it is much easier to detect the use of this or that tense. Present Simple pointers will prompt you that in such a context it is the simple present that is used, and not, for example, Present Continuous.

But you should always be careful. Some markers can refer to multiple times. The choice in such cases comes only from the context and understanding of the essence of the situation. And there may be sentences in which there are no circumstances of the tense at all and an indication of the verb form. Therefore, in order to use Present Simple correctly and correctly interpret the indicator hints, it is necessary to master the values of the present simple.

List of time markers

There are often more difficult situations. Sometimes we talk about events inherent in Present Simple. Sometimes we use Present Continuous and other times. It can be difficult to figure it out here, and temporary pointers make our life very much easier.

Basic temp pointers for Present Simple Tense (simple present tense)

| always | always |

| often | often |

| usually | usually |

| sometimes | sometimes |

| never | never |

Without these pointers, nowhere. You definitely need to know them. Often we are also asked the question: «How often do you do it?» (How often do you do this?)

And here there are often variations — twice a week, three times a week, every day, etc. How to say it?

Temporary pointer table for Present Simple Tense (simple present tense)

| every day | Cada dia |

| every week | every week |

| every month | every month |

| Every year | every year |

| two times a week | twice a week |

| three times per week | three times a week |

| four times a month | four times a month |

| on weekends | at weekends |

| on Mondays | on Mondays |

| on Sundays | on Sundays |

| rarely | seldom |

| Rarely |

This is a more extensive list of temporary pointers. Very often students forget how to say the word «rarely» in English. Not everyone knows the words seldom and rarely. In this case, you can say sometimes and everything will be clear.

It is also important to pay attention to the differences between British and American English when we talk about temporary pointers. How do you say “on weekends” in English? UK version — at weekends. The American version is on weekends. That is, a different pretext is put.

So, for each time in the English language there are auxiliary words — clues that show what kind of temporary form we have in front of us. Present Simple is no exception, and has its own list of auxiliary words.

Examples of time markers

Sample sentences with adverbs of frequency in Present Simple:

- He always gets up at 7 am — He always gets up at 7 am.

- They are usually at home in the evening. “They’re usually at home in the evening.

- Miranda and Greg often visit their grandmother. — Miranda and Greg often visit their grandmother.

- She rarely meets her friends. — She rarely meets with friends.

- We are hardly ever late for work. — We are almost never late for work.

- I never borrow money from my friends. — I never borrow money from friends.

Usually adverbs of frequency are placed before the main verb of the sentence, in particular:

- I sometimes have a shower in the morning. — I sometimes take a shower in the morning.

- Mark doesn’t always give his girlfriend flowers. — Mark does not always give flowers to his girlfriend.

However, there is one situation where this order of words is violated — when there is a verb to be in a sentence, adverbs of frequency are established after it, for example:

- She is hardly ever worried. — She almost never worries.

- Helen and Mike aren’t usually at work at this time. — Helen and Mike are usually not at work at this time.

As a rule, adverbs of frequency are placed before the main verb of a sentence, in particular:

- I sometimes have a shower in the morning. — I sometimes take a shower in the morning.

- Mark doesn’t always give his girlfriend flowers. — Mark does not always give flowers to his girlfriend.

However, there is one situation where this order of words is violated — when there is a verb to be in a sentence, adverbs of frequency are placed after it, in particular:

- She is hardly ever worried. — She almost never worries.

- Helen and Mike aren’t usually at work at this time. — Helen and Mike are usually not at work at this time.

Phrases expressing frequency — they are usually placed at the end of a sentence.

Phrases formed by the word every:

- every + day / week / month / year

- I go shopping every day. — I go shopping every day.

- Scarlett watches a new film every week. — Scarlett watches a fresh movie every week.

- She visits her mother-in-law every month. — She visits her mother-in-law every month.

- Molly goes on holiday every year. — Molly goes on vacation every year.

Phrases formed using the words once and twice:

- once + a week / month / year and twice + a week / month / year

- We see each other once a month. — We see each other once a month.

- Ivan has English lessons twice a week. — Ivan studies English twice a week.

Starting from 3 times or more, we use the word times: three times a month, four times a year

Charlotte’s daughter usually comes to see her about ten times a year. “Charlotte’s daughter usually visits her about ten times a year.

Source: https://englishfull.ru/grammatika/slova-markery-present-simple.html

Adverbs in English: rules of education and place in a sentence with tables and translation

An adverb is a part of speech that answers the question «How?» and characterizes a verb, adjective or other adverb. There are different types of adverbs — manner of action (how), place (where), time (when), degree (to what extent), frequency (how often), opinions. Consider the rules for using adverbs in English.

Formation of adverbs in English

How are adverbs formed? By structure, adverbs can be divided into the following groups:

| Simple | Derivatives | Composite | Composite |

| long (long) | slowly | anyhow (in any way) | at once (immediately) |

| enough (enough) | wise (similarly) | sometimes (sometimes) | at last (finally) |

| then (then) | forward | nowhere (nowhere) | so far (so far) |

The most common way to form adverbs is by adding the -ly suffix to the adjective. Such adverbs usually have a similar meaning to them.

| Adjective | Adverb |

| bad | badly (poorly) |

| Beautiful | beautifully (beautiful) |

| carefully | Carefully (attentively) |

| quick | quickly (quickly) |

| quiet | quietly (quiet) |

| soft | gently (soft) |

Consider the spelling change when adding the -ly suffix:

- le changing to ly (gentle — gently)

- y changing to ily (easy — easily)

- ic changing to ically (automatic — automatically)

- ue changing to uly (true — truly)

- ll changing to eye (full — fully)

Other examples of suffixes: -ward (s), -long, -wise

- clockwise

- forward

- headlong

Adverbs are exceptions

Some adverbs can be both adjectives and adverbs in different situations without adding suffixes:

- It was a fast train. The train went fast.

- He returned from a long journey. Will you stay here long?

- The price is very low. The plane flew very low.

- We have very little time. He reads very little.

Other examples of exceptions are hard, high, deep, last, late, near, wide, early, far, straight, right, wrong.

Most common exception: good — well.

Some adverbs have two forms — one without -ly and one with it. These forms have different meanings. Examples: hard / hardly, last / lastly, late / lately, near / nearly, high / highly.

| Adjective | Adverb without -ly | Adverb with -ly |

| He is a hard worker | He works hard | I could hardly understand him (I could hardly understand him) |

| He returned in late autumn (He returned in late autumn) | I went to bed late yesterday (I went to bed late yesterday) | I haven’t seen him lately (I haven’t seen him lately) |

| He is studying the history of the Near East | He lives quite near | It is nearly 5 o’clock (Now almost 5 o’clock) |

| The house is very high | The plane flew very high | It is a highly developed state |

Place and order of adverbs in a sentence

Where is the adverb in English? The position in the sentence depends on the type of adverb (read below), their number and other factors.

| — before adjectives, other adverbs and participles | The task was surprisingly simple.He walked very fast.We are extremely interested in their offer. |

| — usually after verbs | He speaks slowly |

| — at the beginning of a sentence for emphasis | Slowly, he entered the room. Now I understand what you mean |

| — when there are two or more adverbs in a sentence, they go in the following order: manner — place — time | She spoke very well here last time |

| — if the sentence contains a verb of movement (go, come, leave etc.), the adverbs go in this order: place — manner — time | She arrived here by train yesterday |

Types of adverbs in English with lists

The following classification of adverbs is distinguished — the adverbs of the mode of action, time, frequency, place and direction, degree and opinion. Let’s consider all these groups in more detail.

Adverbs of manner

Such adverbs tell us how something is happening: well, badly, slowly, and so on.

- How did John behave? He behaved badly.

- Did you sleep well?

- He came very quickly

We do not use adverbs after linking verbs to be, become, feel, get, look, seem. We use adjectives after them.

- Sue felt happy

- Nobody seemed amused

- I am not sure

Mode adverbs appear before the main verb, after auxiliary verbs, or at the end of a sentence

- They quickly returned

- He was anxiously waiting for their reply

- She smiled kindly

Adverbs of time

List of adverbs of the time: When (when), now (now), then (then, then) before (before, before) after (then, after), afterwards (subsequently), once (once), fair (just now, just), still (still), already / yet (already), yet (yet, yet), since (since), early (early), lately / recently (recently), suddenly (suddenly), soon (soon), long (for a long time), August (ago), today (today), Tomorrow (tomorrow), yesterday (yesterday) etc.

Tense adverbs usually appear at the end of a sentence. They can be placed in the first place for emphasis, in other words, to give the desired stylistic coloring:

- I saw her yesterday

- Still I can’t understand what happened then (still ahead for dramatic coloring)

Some monosyllabic adverbs of the tense (soon, now, then) come before the main verbs and after the auxiliary verbs:

- I now understand what he means

- She will soon come back home

Remarks:

- We say tonight (tonight / night), tomorrow night, last night (not “yesterday night”)

- Already and yet can mean already. At the same time, already is used only in statements, and yet in questions and negations.

- The preposition for can mean “during” and is used with adverbs of time: for a long time, for 10 years.

Adverbs of frequency

They answer the question «How often?» The most common ones are: always (always), generally, normally, normally (usually), frequently, frequently (often), seldom, rarely (rarely), Sometimes (sometimes), from time to time, occasionally (occasionally), never (never).

Where to put such adverbs? Frequency adverbs come after auxiliary verbs, but before the main semantic ones:

- He has never visited us.

- Paul is often barks.

- He Sometimes comes here.

Generally, usually, normally, often, frequently, sometimes can be at the beginning of a sentence to give a stylistic coloring:

- I usually go to work by metro. — Usually, I go to work by metro.

Adverbs of place and direction

List of the main adverbs of place and direction: here (here), there (there, there), Where (where, where), somewhere, anywhere (somewhere, somewhere) nowhere (nowhere, nowhere) elsewhere (somewhere else) far away (far), near (close), inside (inside), outside (outside), above (above, above), below (below, below).

Such adverbs are usually placed at the end of a sentence:

- How long are they going to stay here?

Somewhere, anywhere, nowhere

Source: https://dundeeclub.ru/grammar/narechiya-v-anglijskom-yazyke-s-perevodom-tablitsami-i-primerami-adverbs.html

Frequency adverbs in English

Skip to content

In this article, we will analyze the adverbs of frequency in the English language.

These include adverbs of time, which provide the listener with additional information, showing the frequency of events.

These adverbs are important and should be part of the vocabulary of any English learner.

There are two types of frequency adverbs in English:

- certain adverbs of frequency that clearly indicate the frequency, time frame;

- indefinite adverbs of frequency that do not indicate specific terms.

Let’s take a closer look at them and learn how to use them.

Certain adverbs of frequency in English

Words that clearly describe the frequency with which events occur. Whether it’s week, month, time of day, day of the week:

- once — once, once;

- twice — twice;

- three, four times — three, four times;

- daily — daily;

- monthly — monthly;

- yearly / annually — annually.

Certain adverbs of frequency:

- change the meaning of the verb (characterize it);

- in most cases, they are placed at the beginning (separated by a comma) and at the end of a sentence;

- ending in «-ly»: used only at the end of a sentence; can act as adjectives — daily meetings, yearly report.

I drink beer daily… — Every day I drink beer.

They eat rice once a week… “They eat rice once a week.

They play football four teams a week… — They play football four times a week.

Frequency adverbs with «every»

Every:

- morning, evening, night — every morning (evening, night);

- weekend — every weekend;

- Saturday, Monday, ect. — every Saturday (Monday, etc.);

- minute, hour, day, week, year — every minute (hour, day, week, year).

every morning, I drink tea. — Every morning I drink tea.

Every year , my parents go to the theater. — Every year my parents go to the theater.

My mother cooks Cada dia… — My mom cooks every day.

All the family every week go fishing. — Every week the whole family goes fishing.

Every Friday, they play poker until the night. “They play poker until nightfall every Friday.

Always

Described Probability: 100%

They always go to the beach in the summer. — In the summer they always go to the beach.

My father is always very busy. — My father is always busy.

Usually

Described Probability: 90%

We usually get up at 10 am — We usually get up at 10 am.

Does Jane usually have lunch at home? «Does Jane usually have dinner at home?»

Normally

Translation: usually, as usual, usual

Described Probability: 80%

I Normally pay my rent. — I usually pay the rent.

He doesn’t Normally wear jeans. — He usually doesn’t wear jeans.

often, frequently

Described Probability: 60-70%

I often read before bed. — Before going to bed, I often read.

I Frequently exercise in the evenings. — I often exercise in the evenings.

Frequency adverbs in English describing events that occur from time to time

Source: https://englishboost.ru/narechiya-chastotnosti-v-anglijskom/

Place of an adverb in a sentence in English: before a verb or after?

The place of an adverb in a sentence in English is not fixed in many cases. The same adverb can be used at the beginning, middle or end of a sentence. We will consider the basic patterns of the arrangement of adverbs in a sentence, the features of the use of individual adverbs.

Typically, an adverb occupies one of three positions in a sentence.

After the predicate and the complement, if any.

Let’s stay here… — Let’s stay here.

Before the subject.

Yesterday we had a good time. “We had a good time yesterday.

If the predicate consists of one verb, then “in the middle” is before the verb.

He Rarely talks to his neighbors. — He rarely talks to neighbors.

If the predicate has more than one word, then “in the middle” is after the auxiliary or modal verb.

You can never rely on him. — You never you can’t rely on him.

He is always late. — He always is late.

Some adverbs can appear before an auxiliary or modal verb.

He really is the person we were looking for. — He really and there is the person we were looking for.

He Surely can drive. — He definitely knows how to drive a car.

In an interrogative sentence, “middle” is between the subject and the main verb.

Do you often help people? — You often do you help people?

Consider in which cases the adverb is at the end of a sentence, at the beginning and in the middle.

Place of adverbs of mode of action

Mode of action adverbs such as slowly — slowly, fast, quickly — quickly, immediately — immediately, well — well, are at the end of the sentence.

You have done your work well. — You did the job good.

Hold the box carefully. — Keep the box carefully.

come back immediately. — Come back immediately.

Cats can sneak very slowly. — Cats are very good at sneaking slow.

Adverbs of place

Place adverbs such as here — here, there — there, also at the end of the sentence.

We will build a church here. — We will build here church.

His office is there. — His office there.

Place of adverbs of tense in a sentence

At the end of the sentence, adverbs indicating a specific time are used: now — now, now, tomorrow — tomorrow, yesterday — yesterday, etc. Do not confuse them with such adverbs as often — often, Rarely — rarely, always — always, never — never, indicating the frequency of action — they are also called adverbs of frequency (adverbs of frequency).

Don’t forget to return the books tomorrow. “Don’t forget to return the books tomorrow.

You will be safe now. — Now you will be safe.

The same adverbs, especially if you need to emphasize them, are often used at the beginning of a sentence:

tomorrow we will put an end to it. — Tomorrow we will put an end to this.

Now you will tell me the truth. — Now you will tell me the truth.

Place of adverbs of frequency (always, never, etc.)

Frequency adverbs are a type of time adverb that indicates how often an action takes place: often — often, Sometimes — sometimes, always, ever — always, never — never, Rarely — rarely, usually — usually. They are located in the middle of the sentence.

I usually take a bus to work. — I usually take the bus to work.

You can always use my tools. “You can always use my tools.

Usually sometimes found at the beginning of a sentence.

usually, we have lunch together. “We usually have lunch together.

Please note that if the adverb of frequency indicates not an indefinite frequency (always, rarely), but a specific one (every day, on Sundays), it is usually used at the end of a sentence:

We go to the swimming pool on Sundays… — We go to the pool on Sundays.

He reads in English every day. — He reads in English every day.

Place of adverbs of measure and degree

Adverbs of measure and degree include words such as: really — really, very, very — very, extremely — extremely, quite — enough, fair — just, just now, Almost — almost. They are in the middle of the sentence.

Adverbs of measure and degree can be used with an adjective or other adverb in front of them.

- Adverb before adjective:

The noise was too loud. — The noise was too loud.

It was extremely dangerous. — It was extremely dangerously.

- Adverb before another adverb:

They can also characterize the actions and states expressed by the verb. Let me remind you that if there is one verb in a sentence, then “in the middle of the sentence” — before this verb.

If there is an auxiliary or modal verb, then “in the middle of a sentence” is after the modal or auxiliary verb.

Some reinforcing adverbs such as really — really, surely, certainly — exactly, of course, definitely — definitely, can come before an auxiliary or modal verb.

Exceptions — adverb enough (enough), it comes after the word being defined.

Source: https://langformula.ru/english-grammar/adverb-position/

Adverbs in English (Adverbs)

The adverb is the part of speech that determines when, where, and how an action is taken. A feature of this part of speech is also that it is capable of transmitting signs of an adjective or other adverb. It is also important to remember that adverbs in English play the role of circumstances. Consider the formation of adverbs, give vivid examples and exceptions to the rules where they are put in a sentence, and also consider the degrees of comparison.

Adverbs in English: Basic Functions

It will be easy for beginner students who have just decided to study languages to master this topic, since the adverb in English performs the same functions as in Russian, and is often placed in an identical position. Therefore, the language barrier will be overcome quickly and easily.

The most commonly used types of adverbs in tables =>

Place adverbs WHERE (ADVERBS OF PLACE)

| close | near |

| long away | far |

| inside | inside |

| there | there |

| everywhere | everywhere |

| here | here |

Time adverbs WHEN (ADVERBS OF TIME)

| late | late |

| soon | soon |

| early | early |

| then | then |

| today | today |

| now | now |

On a note! When, where and why are relative adverbs. The tenses are used in any speech — business, colloquial, artistic and narrow-profile. Relative words can easily and simply explain any situation.

Action adverbs HOW (ADVERBS OF MANNER)

| carefully | Carefully |

| poorly | badly |

| fast | solid |

| simple / easy | easily |

| complicated | hard |

| loud | loudly |

Adverbs of measure and degree TO WHAT EXTENT (ADVERBS OF DEGREE)

| rather | rather |

| terribly | terribly |

| almost | Almost |

| too | too |

| very | very |

| really | really |

If you find it difficult to learn the words themselves and understand the adverbs and the rules that the table indicates, use them in sentences. By examples it is always easier to learn a rule, of all kinds.

Here are some examples:

The girl faced the difficult situation very bravely => The girl met a difficult situation very bravely. The adverb answers the question How? How?

My mom came home late because she didn’t manage to catch the bus => Mom came home late (when Mom came home, time was later) because she could not catch the bus. The adverb answers the question When? When?

The Professor explained the theory three times and extremely patiently => The professor explained the theory three times and very patiently. The adverb answers the question To what extent? To what extent?

These yummy mushrooms were everywhere => These delicious mushrooms were everywhere (everywhere). The adverb answers the question Where? Where?

Rules for the formation of an adverb in English

All adverbs in which the English language is rich are divided into 4 categories =>

- Simple (Simple Adverbs)

Source: https://speakenglishwell.ru/narechiya-v-anglijskom-yazyke-adverbs/

Frequency adverbs in English

Adverbs play an important role in communication, they describe the way, character, image of the performed action. When we want to indicate how often a particular action is performed, we use an adverb that expresses frequency. What adverbs of frequency exist, how they differ and how to use them in speech — read further in this article.

The adverb of frequency indicates how often an action is performed (which is more often

everything is represented by a verb). There are 6 main adverbs of frequency: always — always, usually (or normally) — usually, often — often, sometimes — sometimes, rarely — rarely, never — never. They differ in the degree of frequency with which the action they describe is performed. What are the differences, see the table below.

In addition to rarely, seldom can be used, but it is gradually falling out of use in modern English.

The place of the adverb of frequency in the sentence

As you can see from the table above, the main place for the adverb of frequency in a sentence is

between the subject and the predicate, between the subject of the action and the action. Below are a few more examples:

- Sara always goes out on Saturday evenings. / Sarah always walks on Saturday nights.

- her boyfriend usually picks her up and they drive into the city center. / Her boyfriend usually picks her up by car and they drive to the city center.

- They often meet friends and have a drink together. / They often meet up with friends and go to a bar.

- In the winter they Sometimes go to the cinema. / In winter they sometimes go to the movies.

- They Rarely go in the summer because they prefer to stay outside. / In the summer they rarely go to the movies, as they prefer to stay in the fresh air.

- They never get home before midnight. / They never do not return home until midnight.

An exception to this rule is the verb to be (to be)… In sentences with this verb, the adverb of frequency comes after the verb, as in these examples:

- There are always lots of people in the city center on Saturday nights. / On Saturday evenings in the city center (available) always many people.

- It’s often difficult to find a place to park. / (This is) often difficult to find a parking place.

- But our friends are never on time so it doesn’t matter if we’re late. / But our friends (are) never [don’t come] on time, so it doesn’t matter if we’re late.

As is often the case in English, there are variations on this rule. For example,

you can put adverbs sometimes — sometimes and usually — usually at the beginning of a sentence:

- Sometimes she does her homework with friends. / Sometimes she is doing her homework with friends.

- Usually they study on their own. / Usually they do it on their own.

But, of course, the easiest way is to follow the basic rule and put all adverbs that express the frequency between the subject and the predicate, the subject of the action and the action.

Question form

To ask a question about how often an action is performed, it is usually used

How often design? — «How often?», For example:

- how often do you watch films? / How often do you watch movies

- how often does he play tennis? / How often he plays tennis?