Computational lexicography deals

with the design, compilation, use and evaluation of electronic

(electronically readable/machine readable) dictionaries. Electronic

dictionaries fundamentally differ in

form, content, and function from conventional word-books. Among the

most significant differences are: 1) the use of multimedia means; 2)

the navigable help indices in windows oriented software; 3) the use

of sound, animation, audio and visual (pictures, videos) elements as

well as interactive exercises and games; 4) the varied possibilities

of search and access methods that allow the user to specify the

output in a number of ways; 5) the access to and retrieval of

information are no longer determined by the internal, traditionally

alphabetical, organization of the dictionary, but a non-linear

structure of the text; 6) the use of hyperlinks which allow easily

and quickly to cross-refer to words within an entry or to other words

connected with this entry.

In case of electronic dictionaries the demands on

the user become greater as the emphasis is less on following a

predetermined path through the dictionary structure and more on

navigating relationships across and within entries via a choice of

links. So before using an electronic dictionary it is necessary to

acquire certain navigational and searching skills apart from the

‘conventional dictionary skills’. The difference between the

minimal skills acquired for the use of conventional and electronic

dictionaries is given in table.

|

Dictionaries |

Electronic |

|

1. |

1. |

|

2. Knowing how to use the Guide |

2. Knowing how to use the Help |

|

3. |

3. |

|

4. |

4. |

|

5. |

5. Knowing how to use the Audio |

|

6. |

6. |

|

7. |

7. |

|

8. |

8. |

|

9. |

9. |

|

10. |

10. Recording the dictionary information in |

There are distinguished two main types of electronic dictionaries:

online dictionaries and CD-ROM dictionaries. To use on-line

dictionaries it is necessary to have access to the Internet. To

install CD-ROM dictionaries on a computer it is necessary to ensure

that a computer meets the minimum system requirements that are

usually enumerated in the User Guide.

Among the on-line

dictionaries there are the following:

the Oxford English Dictionary Online,

the Merriam-

Webster Online Dictionary, the

Cambridge Dictionaries Online (including

Cambridge Advanced Learner’s

Dictionary, Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms, Cambridge

Dictionary of American English, etc.),

the American Heritage Dictionary of the

English language and many others. Each

dictionary has its own benefits and differs, sometimes greatly, in

the interface, material available, contents area, number of options,

organization of entries, search capabilities, etc. from other

dictionaries of such kind.

The Oxford English

Dictionary Online, for instance,

contains the material of the 20-volume Oxford

English Dictionary and 3-volume

Additions Series. Besides

more revised and new entries are added to the online dictionary every

quarter. The layout of a typical entry window is given below. The

Oxford English Dictionary Online is

characterized by the following main features: 1) the display of

entries according to a user’s needs, i.e. entries can be displayed

by turning pronunciations, etymologies, variant spellings, and

quotations on and off; 2) the search for pronunciations as well as

accented and other special characters; 3) the search for words which

have come into English via a particular language; 4) the search for

quotations from a specified year, or from a particular author and/or

work; 5) the search for a term when a user knows only meaning; 6) the

use of wildcards’ if a user is unsure of a spelling; 7) the

restrictions of a search to a previous results set;

first cited date, authors, and works; 9) the case-sensitive searches;

and some others.

Among the CD-ROM

dictionaries there are the following:

the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English on CD-ROM, the Cambridge

International Dictionary of English on CD-ROM, the

Collins COBUILD on CD-ROM, the

Concise Oxford Dictionary on CD-ROM, and

many others.

In most cases CD-ROM dictionaries are electronic versions of the

printed reference books supplemented by more visual information,

pronunciation, interactive exercises and games and allowing the user

to carry out searches impossible with the book dictionaries.

The Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English on CD-ROM, for

example, differs from the paper dictionary in the following way: 1)

every word is pronounced in British and American English. A user can

also record his/her own pronunciation and compare it with the

accepted form; 2) it gives 15,000 word origins or etymologies and

contains 7000 encyclopedic entries for people, places, and things,

taken from the Longman Dictionary of

English Language and Culture; 3) there

are 80,000 additional examples given in the Longman Examples Bank; 4)

over a million corpus sentences are included for very advanced

learners and teachers of English; 5) it contains 150,000 extra words

(collocates) that are used with the headword; 6) it has the Activator

section which is very helpful in choosing the right word in this or

that context and provides essay writing technique; 7) there are a lot

of interactive activities in grammar, vocabulary, culture, as well as

exam practice exercises.

The Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English on CD-ROM has

its own distinctive features that make it prominent among the

dictionaries of this kind. There are three main functions in the

CD-ROM dictionary, each opening in the main window but with a

slightly different look. These three functions are the Dictionary,

Activator, and Exercises.

Users can choose the full sized

display, or «Pop-Up Mode». The dictionary interface

includes a search bar, an area for viewing entries, and windows for

the Phrase Bank, Examples Bank, and

the Activate Your Language tool.

In the entry display (left side of the screen),

the word is presented along with links to pronunciation, usage note,

word origin, verb form, and word set, but not all links are active

for all entries. The Phrase Bank

includes phrases that use the search

word, as well as words that are commonly used with the search word.

The Examples Bank presents

samples of the word’s usage from “Extra dictionary examples”

and “Sentences from books, newspapers, etc.” The Activate

Your Language section, which does not

have entries for all words, allows a user to continue the search in

the Activator.

In lexicography the developments in electronic instrumentation and

computer science have revolutionized the dictionary-making process,

shown new perspectives in this field, supported lexicographical

studies in different directions.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

11

Abstract

Modern trends in English lexicography

Table of contents

Introduction……………………………………………………….3

Modern trends in English lexicography……………………………4

Conclusion………………………………………………………...10

List of sources……………………………………………………..11

Introduction

There is, however, another point of view on lexicography. Its supporters believe that lexicography is not just a technique, not just a practical activity in compiling dictionary entries and not even an art, an independent scientific discipline that has its own subject of study (dictionaries of various types), its own scientific and methodological principles, its own theoretical problematics. its place among other sciences in the language.

For the first time this point on lexicography was expressed with certainty by the prominent Soviet linguist Academician L.V. Shcherba. In the preface to the Russian-French dictionary (1936), he wrote: «I consider it extremely wrong that our qualified linguists disdain for dictionary work. How did she get such a ridiculous name «compilation» of dictionaries. And indeed, our linguists, and even more so our «compilers» of vocabulary, insisted that the work should be of a scientific nature and in no way consist in a mechanical comparison of some ready-made elements».

The last decade was marked by a significant rise in lexicographic activity and the release of a large number of Russian-language author’s words of new types, the subject of the lexicographical description of which is paraliterature and its derivatives, namely comics, feature films and computer games, computer games, fantasy.

Lexicographers came to the creation of qualitatively new reference books from the point of view of the addressee, the issue of choosing sources.

It should be especially noted that the prototype of the new author’s words are the projects of the projects of reference books created by readers for the works of the fantasy genre, which are of great interest among users. First of all, this circumstance is associated with the lack of professional reference books for modern works of the fantasy genre, which is difficult to understand without certain cultural, historical and mythological knowledge.

Modern trends in English lexicography

The modern period in the development of the lexicography of the English language can be called «scientific or historical», since it is based on the following concepts:

1) compilation of dictionaries according to the historical principle;

2) replacing the prescriptive or normative principle of compiling dictionaries with a systemic descriptive approach;

3) description of vocabulary as a system [1].

The first scientific dictionary was Roger’s Thesaurus, but the pearl of English lexicography that best embodied these concepts is the Oxford English Dictionary, the largest lexicographic project of the 19th and 20th centuries. Work on it began under the auspices of the Royal Philological Society in 1857, with the first volume published in 1888 and the last in 1933. The dictionary is edited by Sir James Murray. Roger’s thesaurus belongs to a special group of dictionaries — ideographic. In thesaurus dictionaries, vocabulary is organized according to a thematic principle. Roger began his work by dividing the conceptual field of the English language into four large classes: abstract relations, space, matter and spirit (mind, will, feelings). These classes are further subdivided into several genera, which, in turn, are subdivided into a certain number of species. Each species includes numbered groups. These groups (there are 1000 of them in total) are designated by words with a sufficiently broad semantics, which makes it possible to combine under them a number of words that are close in meaning [2].

However, soon after the publication of the dictionary, it became clear that it is very difficult to use it. Practice required a reasonable synthesis of the ideographic and alphabetical arrangement of words. So Roger added an alphabetical index to the dictionary, giving each word information about its place in ideographic classification. Roger’s thesaurus should be recognized as an outstanding phenomenon in world lexicography. Its main advantage is that it was the first scientifically substantiated attempt to create a kind of mock-up of a logically ordered language dictionary.

Recently, in the lexicography of the English language, there has been a clear tendency to reflect linguistic phenomena in direct connection with the elements of culture, thereby describing the influence of culture on the formation of language. An example is Longman Dictionary of English and Culture, Macmillan Dictionary.

The study of lexicography is closely related to the problems considered in lexicology. Revealing the meanings of polysemantic words and ways of their representation in dictionaries, distinguishing homonymy and polysemy, synonymy of lexical units — these are just some of the problems faced by both lexicologists and lexicographers. Compilers of dictionaries use the achievements of lexicology in their works, and lexicologists very often turn to the data of dictionaries in their research [3].

Depending on the number of languages represented, all linguistic dictionaries can be divided into three types: monolingual, bilingual and multilingual. The last two types are often referred to as translation dictionaries.

By designation and purpose of creation, explanatory dictionaries are divided into descriptive and prescriptive (normative). In English lexicographic terminology, they are called descriptive and prescriptive, respectively.

Descriptive dictionaries are intended to fully describe the vocabulary of a particular area and to record all its uses.

The quality of descriptive vocabulary depends on the degree of completeness with which its vocabulary reflects the area described, and on how accurate the definitions of the meaning of the words presented in the material are. The best example of a descriptive English dictionary is the Oxford English Dictionary.

By the way the vocabulary is organized in the dictionary, a special type of dictionaries can be distinguished — ideographic dictionaries or (as they are often called) thesauri. An example of such a dictionary is Roger’s Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases. Unlike explanatory dictionaries, in which dictionary entries are arranged in alphabetical order of the headword, ideographic dictionaries organize vocabulary by topic.

By the nature of the vocabulary, explanatory dictionaries are divided into general and private. Oxford English Dictionary, Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Random House Dictionary of English are general explanatory dictionaries because they reflect the entire lexical system of the English language, and not any part of it.

Private explanatory dictionaries should include dictionaries that reflect only a specific area of the vocabulary of the national language. Such are, for example, dictionaries of phraseological units (idioms), dialectal or slang dictionaries. The Oxford Dictionary of American Slang (1992) and the Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (1999) are their own explanatory dictionaries.

Depending on the target orientation, dictionaries can be divided into general and private. Aspect orientation assumes the following levels of vocabulary description:

Phonetic (pronunciation dictionaries);

Spelling (spelling dictionaries);

Word-building (dictionaries of word-building elements);

Syntactic (collocation dictionaries);

Pragmatic (frequency dictionaries) [4].

Among other types of words can be called usus dictionaries (in English terminology «dictionaries of use»), the subject of the description is the features of the use of linguistic forms, especially those that can cause difficulties. Two varieties of such lexicographic reference books are dictionaries of difficulties and dictionaries of compatibility: Dictionary of Common Mistakes of Longman (1987), Combinatorial Dictionary of the English language BBI, edited by M. Benson, E. Benson, R. Ilson (1986).

Professor I.V. Arnold proposed her original classification of dictionaries based on the principle of oppositions to the distinctive features of a dictionary.

Some scholars refer to special monolingual and bilingual dictionaries terminological glossaries, concordances, dictionaries of antonyms and synonyms, borrowings, neologisms, abbreviations, proverbs, personal and surnames, toponyms.

Thus, in the history of lexicography, there is more than one classification of dictionaries. There are a lot of them. Summarizing the well-known category Dubichinsky V.V. One of the 9 differentiating bases developed their unification, one of which includes onomastic dictionaries from the point of view of culturology, that is, dictionaries of toponyms, anthroponyms, chrematonyms and others [5].

According to the most authoritative experts in the field of lexicography (in particular):

1) The desire for such a completeness of the characteristics of the word allows not only to understand it in a given context, but also to use it correctly in one’s own speech. Thus, the transition to active type dictionaries is carried out.

2) Striving to overcome the traditional isolation of lexicography from theoretical linguistics in general and from semantics in particular.

3) Striving to overcome the traditional isolation of the dictionary description of the language from its grammatical description.

4) Transition from a purely philological description of a word to an integral philological and cultural description of a word-concept, with the involvement of elements of ethnolinguistic knowledge.

5) Updating lexicographic techniques and means: the introduction of «guides» for a dictionary entry, an assessment of the correctness of the use of one or another word in different situations on the basis of a representative «linguistic collegium». This method has already been successfully tested in the compilation of the Dictionary of the English Language «American Heritage», the material of which was tested by a collegium of one hundred recognized native speakers of exemplary of English language [6].

The main theoretical problems of lexicography:

1) the problem of choosing vocabulary for vocabulary

2) the problem of the optimal structure of a dictionary

3) ways of interpreting the meaning of a word in a dictionary entry

4) the means used by compilers of dictionaries to illustrate the use of a word in speech,

5) development of parameters that underlie the classification and quality assessment of dictionaries.

The theory of lexicography studies the history of dictionaries, their typology, and deals with the critical description of dictionaries.

Lexicography as a practice includes collecting materials, editing, preparing a dictionary, publishing it, presenting it, and organizing an advertising campaign.

The study of lexicography is related to the problems considered in lexicology. Highlighting the meanings of polysemous words and ways of representing them in dictionaries, differentiating homonymy and polysemy, lexical synonymy are just a few of the problems that both lexicologists and lexicographers deal with. Compilers use the achievements of lexicology in their works.

The field of modern lexicography presents a great number and variety of dictionaries of all types. Within English lexicography there are monolingual and bilingual general dictionaries, etymological and present-day English dictionaries, those which deal with jargon, dialects and slang. Modern lexicography distinguishes between historical and pragmatically oriented or learner’s dictionaries. Pragmatically oriented dictionaries are those which side by side with meanings of words recorded in works of literature register functionally prominent meanings, thus giving the readers a clear idea of how the word is actually used in speech.

Modern trends in English Lexicography are connected with the appearance and rapid development of such branches of linguistics as Corpus Linguistics and Computational Linguistics.

Corpus-based Linguistics deals mainly with compiling various electronic corpora for conducting investigations in linguistic fields such as phonetics, phonology, grammar, stylistic, discourse, lexicon and many others. Corpora are large and systematic enterprises: they contain conversations, magazine articles, newspapers, lectures, chapters of novels, brochures, etc. Among them The British National Corpus, Longman Corpus Network, Spoken British Corpus, International Cambridge Language Survey, etc. Corpus provides investigators with a source of hypotheses about the way the language works.

A large and well-constructed corpus gives excellent information about frequency, distribution, and typicality of linguistic features – such as words, collocations, spellings, pronunciations, and grammatical constructions. The development of Corpus Linguistics has given birth to Corpus-based Lexicography and a new corpus-based generation of dictionaries.

The use of corpora in dictionary-making practices gives a lexicographer a lot of opportunities; among the most important ones is the opportunity:

1) to produce and revise dictionaries very quickly, thus providing up-to-date information about the language;

2) to give more complete and precise definitions since a larger number of natural examples are examined;

3) to keep on top of new words entering the language, or existing words changing their meanings;

4) to treat phrases and collocations more systematically than was previously possible due to the ability to call up word-combinations rather than words due to the existence of mutual information tools which establish relationship between co-occurring words;

5) to register cultural connotations and underlying ideologies which a language has.

Some of lexicographical giants have their own electronic text archives which they use depending on the type of dictionary compiled.

Conclusion

Modern trends in English lexicography are connected with the appearance and rapid development of such branches of linguistics as corpus (or corpus-based) linguistics and computational linguistics. Corpus (or corpus-based) linguistics deals with compiling various electronic corpora for conducting investigations in different linguistic fields. Computational linguistics is the branch of linguistics in which the techniques of computer science are applied to the analysis and synthesis of language and speech. Computational lexicographydeals with the design, compilation, use and evaluation of electronic dictionaries. Electronic dictionaries fundamentally differ in form, content, and function from conventional word-books. Among the most significant differences are: 1) the use of multimedia means; 2) the navigable help indices in windows oriented software; 3) the use of sound, animation, audio and visual (pictures, videos) elements as well as interactive exercises and games; 4) the varied possibilities of search and access methods that allow the user to specify the output in a number of ways; 5) the access to and retrieval of information are no longer determined by the internal, traditionally alphabetical, organization of the dictionary, but a non-linear structure of the text; 6) the use of hyperlinks which allow easily and quickly to cross-refer to words within an entry or to other words connected with this entry. There are distinguished two main types of electronic dictionaries: online dictionaries and CD-ROM dictionaries.

List of sources

Babich, Galina Nikolaevna (2016). Lexicology: a current guide = Lexicologia angliskogo yazyka (8 ed.). Moscow: Flinta. p. 1. ISBN 978-5-9765-0249-9. OCLC 934368509.

Dzharasova, T. T. (2020). English lexicology and lexicography: theory and practice (2 ed.). Almaty: Al-Farabi Kazakh National University. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-601-04-0595-0.

Dzharasova, T. T. (2020). English lexicology and lexicography: theory and practice (2 ed.). Almaty: Al-Farabi Kazakh National University. p. 41. ISBN 978-601-04-0595-0.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2007). Lexicology: a short introduction. Colin Yallop. London: Continuum. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-4411-5054-7. OCLC 741690096.

Joseph, Brian D.; Janda, Richard D., eds. (2003), «The Handbook of Historical Linguistics», The Handbook of Historical Linguistics, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, p. 183, ISBN 9780631195719.

Popescu, Floriana (2019). A paradigm of comparative lexicology. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 1-5275-1808-6. OCLC 1063709395.

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

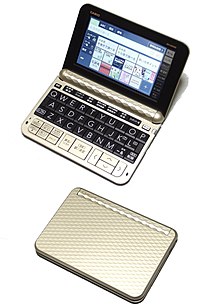

An electronic dictionary is a portable electronic device that serves as

the digital form of any kind of dictionary. Available in a number of forms,

electronic dictionaries range in function from general single-language

dictionaries to very specific, terminology-based dictionaries for medical,

legal, and other professional languages. The size of most print dictionaries

can be cumbersome and costly, so putting this information into electronic form

reduces the unwieldiness of carrying them as well as reduces their cost, as

large quantities of paper are saved and the material is contained in computer

memory devices.

The topicality

of work is in the fact that e-dictionary is used in every area by different

kind of people, especially by young learners.

The aim of the research work is giving general

characteristics to e-dictionary and defining the main ways of its using in

developing four skills.

To achieve our aim we

have to solve the following objectives:

1.

Define the functions of innovative technologies

in teaching foreign language;

2.

Analyze a types of e-dictionaries;

The object of the work is e-dictionaries of

the English language.

The subject

is causes and tendencies of English language.

E-dictionaries are very wide theme to

investigate; it has many types and tendencies for today. At our term paper the scientific novelty of the investigation is the use of e-dictionaries through

teaching.

The theoretical

significance of the work is the

usage of e-dictionaries in English language reveals its causes and tendencies.

The e-dictionaries is very useful in the

society. We face to them on the mass media and of course at everyday

communication.

The practical

significance of the investigation is

in the fact that this material can be recommended for widening vocabulary and

development of speech and knowledge of English language.

The research work consists of introduction,

theoretical and practical parts, conclusion, list of used literature.

1.

Innovative

technologies in teaching Foreign Language

1.1 The concept of e-dictionary

An electronic dictionary is a portable electronic device that serves as

the digital form of any kind of dictionary. Available in a number of forms,

electronic dictionaries range in function from general single-language

dictionaries to very specific, terminology-based dictionaries for medical,

legal, and other professional languages. The size of most print dictionaries

can be cumbersome and costly, so putting this information into electronic form

reduces the unwieldiness of carrying them as well as reduces their cost, as

large quantities of paper are saved and the material is contained in computer

memory devices.

As technology has advanced, the number of features that are available in

electronic dictionaries has also increased. Many models are equipped with

text-to-speech and speech-to-text capabilities, interactive vocabulary games,

calculators, and data transport. Most recently, electronic dictionaries have

become available on mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers,

although the features on these devices are not as varied or as complex as the

features that are found on conventional handheld dictionaries and current software

offerings [1, 39].

Until fairly recently, there were two kinds of

electronic dictionary: small handheld devices with one or more dictionaries

loaded on them, and optical disks (CD-ROMs and latterly DVD-ROMs) sold

alongside the big (paper) learner’s dictionaries like the Oxford Advanced

Learner’s and the Macmillan English Dictionary (MED). Handheld dictionaries —

small devices about the size of a BlackBerry — have been around for many years:

the Speak & Spell machine that ET cannibalized in order to phone home was

an early and primitive example. This is the format of choice in Japan, and

current models may include up to a hundred different dictionaries —

monolingual, bilingual, general, specialized, you name it. Almost three million

of these are sold annually in Japan alone, so it’s a huge market. All the

well-known learner’s dictionaries appear on one or other of these devices, but

the publishers make very little money from this kind of licensing — a fraction

of what they would earn from selling a physical book. One can’t help feeling

this is a transitional technology (albeit one that has shown remarkable staying

power): it’s very hard to use these dictionaries effectively because their

contents are so diverse, and minimally integrated. In any case, this

‘pile-it-high’ model isn’t well-adapted to the needs of language learners: a

dictionary with two million terms on it may sound impressive, but who really

needs it?

Longman’s Interactive English Dictionary was the first

learner’s dictionary to appear in CD-ROM form, back in 1993 [8, 86]. Early

versions of CD-ROM dictionaries were partly a sales gimmick and partly a

genuine effort to engage with the new technology and see how it could improve

access to the information in the dictionary. The new medium provided far more

powerful search functions than the basic alphabetical order that conventional

dictionaries rely on. Throw in audio pronunciations, and a few games and

exercises, and that was the basic package for several years. Looking back, what

is striking about those early electronic dictionaries is that the print medium

was assumed to be the ‘primary’ one, with the electronic a sort of

afterthought: the layout of the CD-ROM screens more or less replicated what you

would find on the pages of the printed book, and publishers were slow to grasp

the implications of the new medium. For example, dictionaries have

traditionally handled idioms by explaining them at one entry, and using

cross-references to redirect the user from other possible locations: thus, kick

the bucket might be defined at the headword kick, and if you looked it up at

bucket you would be referred to the ‘right’ entry. This was, simply, a

space-saving strategy: paper dictionaries have to pack a lot of information

into a limited space, so you can’t afford to have two (or more) entries for the

same idiom. There is no need to do this is an electronic dictionary, of course

— but old habits die hard [1, 87].

Gradually, these products improved as they began to

exploit the opportunities of the medium more intelligently. The CD-ROM for the

Macmillan English Dictionary, for example, includes an ‘advanced search’

function that allows you to perform complex searches with minimum difficulty,

by combining any number of features like register, frequency, and grammatical behavior,

in a Boolean search [9, 213]. So if you want a list of all the high-frequency

transitive verbs which are never — or almost always — used in the passive, this

is easily done. Or you might be interested in all the words and phrases marked

both ‘British’ and ‘humorous’. Or a list of every entry that has the

subject-label Cinema. These and other features — notably a thesaurus which

provides near-synonyms for every word, phrase, and meaning in the dictionary —

mean that the CD-ROM is not just an easily-searchable version of its paper

counterpart, but a store of ‘new’ information which simply wouldn’t fit in a

printed dictionary.

1.2 Classification

and types of e-dictionaries

TYPES OF ELECTRONIC DICTIONARIES

Dictionary of simple

words

Phonological

dictionaries

Dictionary of

compound terms

Meaning

Semantic markers

Dictionaries and

grammars have been recognized as crucial components of most applications of

Natural Language Processing (NLP). Numerous prototypes of language analyzers

and generators have been built, but, practically none of these prototypes incorporate

full scale dictionaries and grammars. This general situation has been dubbed:

processing with «toy dictionaries» and «toy grammars».

Defining a full scale dictionary is already a problem in itself and this

question must be addressed in several steps and constitutes in fact the core of

the project [3, 25].

Dictionary of simple words

The first step is the level of graphically

simple words, namely words as they appear as entries of commercial

dictionaries. In order to match a dictionary of canonical entries with words as

they are found in texts, entries must be inflected. The general inflection

scheme consists in appending inflection codes to canonical entries in order to

generate all inflected forms. This approach seems straightforward, and even well-prepared

by existing material such as conjugation dictionaries built for pedagogical

purposes [2, 96]. However, few such dictionaries exist to-day, either in

academic or industrial environments. There are indeed various questions to be

solved both at the practical and at the theoretical level, in order to reach an

operational stage of coverage for a dictionary. The members of the RELEX group

have all built such a dictionary (DELA) for their language. These dictionaries

are to be completed by many derivatives and technical words [12, 36].

-

derivational morphology is not accounted for in

common dictionaries: because simple words such as:

unreusability,

coprocessible

are easy to coin and to understand, they are not

entered into commercial dictionaries, the reason is that morphological studies

have shown that they are extremely numerous. The size of current dictionaries

is about 100 000 canonical entries (to the extent that derived words can be

listed), derived words increase the size of the lexicon by a factor one hundred

at least;

-

when a dictionary is applied to a text, many

graphic words (i.e. sequences of ASCII characters bounded by consecutive

separators) are not recognized. Proper names and numbers for example are not

entries of current dictionaries.

At this point, a

first definition of full scale dictionary can be given: A full coverage

dictionary is a dictionary which recognizes all the ASCII sequences of a

library of texts [4, 74].

Phonological dictionaries

The morphological

dictionaries DELA under construction by each partner can be adjoined a

phonological component. In this domain it is not thinkable to use only a

universal alphabet like the International Phonetic Alphabet: too many

specialists disagree on the basic sounds. But national alphabets can be easily

designed according to foreseen applications: phonetization of written texts,

use in spelling correction, etc. Constructing a phonetic system is a two

component task:

— First, all the entries of the component of

simple words must be encoded. Then phonogical rules of inflection must be

devised;

— second, a phonetization of corpora using the

phonetic dictionary as well as general rules must be constructed;

— other components will be necessary, for

example in French rules of ‘liaison’ and elision are necessary to generate the

phonetic forms of compounds starting from simple words [5, 122].

The various teams

have already acquired some experience in this area, in particular French and

Italian have been partly described.

Dictionary

of compound terms

The next step in

complexity is the construction of dictionaries of compound terms. The

participants of the project have adopted the classification of parts of speech

used for simple terms:

-

compound verbs: to look upon down, to feel free

to, to take into account, etc. -

compound adjectives: free of charge, well done,

well-to-do, tax-free, etc. -

compound adverb: from time to time, time and

again, in fact, in order to, etc; -

compound nouns: sulfuric acid, border town, deed

of gift, etc. -

other varied compounds, such as determiners (as

many as, a handful of), conjunctions, (as soon as, to the extent that), etc.

Within each of these

major categories, subclasses are defined in terms of the categories that make

the compounds. From the point of view of the recognition of complex utterances

in a text one will have to distinguish at least two main types of entries

depending of the variability of the terms :

-

totally frozen compounds, such as many adverbs,

for example as a matter of fact, or for instance, where the nouns cannot be put

in plural, nor modified by adjectives. The complex preposition in order to is

not in this category because modifying insertions are possible as in in order

presumably to (satisfy her). There are also many compound adjectives such as

stiff necked. -

variable compounds: they range from nouns with a

plural form, which are the simplest changing shapes, to discontinuous verbs,

such as to take X into account where to take [7, 189].

Meaning

The DELA system

common to 6 languages is the most elementary form of dictionary: a list of

words, and attached to each word, the grammatical information needed to inflect

it or to keep it invariable. For European languages, this information is

limited to gender, number, case, tense, mood and person. There is no limit to

the amount of information that one may want to attach to words: syntactic,

semantic, phonetic, stylistic, historical, encyclopedic data can be introduced,

depending on applications. Already, the minimal information previously required

allows for some syntactic computations: rules that establish elementary

agreement between the inflected words of a text, can be defined and used in a

parser. Also this elementary information is used to represent certain

ambiguities (i.e. called homographs at this level of description). [14, 47] For

example, the French word voile can be:

- a masculine noun (veil),

- a feminine noun (sail),

-

a verb (to veil) in the present tense of the

indicative mood, 1st and 3rd person singular. It can also be a form in the

subjunctive (1st and 3rd person singular) and in the imperative (2nd person

singular).

Thus, at the

descriptive level of the parts of speech, we have 3 homographs: 2 nouns, 1

verb. At the more precise level of inflected forms, we have 5 verbal forms,

hence 7 homographic forms.

This level of description does not provide for

semantic ambiguities. For example,

— the masculine noun voile can also mean

«soft palate» (le voile du palais), a fabric (Swiss voile),

difficulty in seeing (un voile devant les yeux), etc. — the verb can mean to

veil a statue, but also to buckle a wheel, etc.

At this point, the

list of words which must be built does not require any evaluation of the use of

words, ancient or modern, hypercorrect or slang, etc. Hence, one does not have

to sort out more or less obsolete words, as for example many found among the

entries of a dictionary such as the Oxford English Dictionary.

With respect to these

minimal demands, a superficial examination of the best available dictionaries

shows that they are incomplete in many respects, and thus unfit as a basis for

automatic analysis [13, 176].

Forms of Electronic Dictionaries

There are five main types of available electronic dictionaries. First,

the most common form of an electronic dictionary is a standalone, handheld

electronic device. CD-ROMs and DVD-ROMs are also an available form of

electronic dictionaries, and these are often included with the purchase of a

conventional, printed dictionary. These programs can then be loaded onto

personal computers. There are also some free or pay-for-use online

dictionaries. Many of the more recent forms of technology, such as eReaders, tablet

computers, and smartphones, now have electronic dictionary capabilities. The

features sought by consumers may vary slightly depending on which type of

electronic dictionary is chosen, but for the most part, they remain similar.

Important Features of an

Electronic Dictionary

There are a number of features that are available on an electronic

dictionary, and this guide will discuss the 10 features that buyers should look

for in an electronic dictionary. However, in addition to these features, some

other considerations when choosing an electronic dictionary should include the

size of the device, whether it is a separate handheld dictionary, its required

power source, the cost of the electronic dictionary, as well as its

compatibility with any of the user’s other devices such as PCs or mobile

devices. Buyers should take these details into consideration, along with the

following top 10 features to look for in an electronic dictionary [10, 269].

1.

Type/Number of Dictionaries

There are a number of popular English dictionaries, such as the Oxford

English Dictionary and the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Some

electronic dictionaries will come with only one dictionary pre-loaded within

its software, while others can offer several different dictionaries. The

variety of dictionaries that is offered and the quality of the default

dictionary can mean the difference between a casual user’s ability to benefit

from the dictionary versus the dictionary being able to be utilized for more

rigorous academic use.

2.

Translation Capability

Many electronic dictionary users are in the process of learning English

as a second language. Having their native language available for translation is

of great use to users in this situation. Additionally, travelers can greatly benefit

from translator programs on electronic dictionaries. These compact devices (or

programs for mobile devices) are beneficial when a user is in a foreign country

and does not know the native language. For professional translators, some

electronic dictionaries may also have storable vocabulary banks for quick

reference. Depending on the level of their translation needs, purchasers should

research the complexity of a specific electronic dictionary’s translating

capabilities.

3.

Thesaurus

A thesaurus allows users to input a word and be given a list of possible

alternatives to that word. Thesauruses are especially popular with students who

need to elevate their vocabulary within assignments. This feature is available

on many electronic dictionaries and is a beneficial one for many.

4.

Pronunciation

For those users who would like to hear the correct pronunciation of

vocabulary words, whether in English or in other languages, some electronic

dictionaries come with speakers and with the ability to sound out the word for

the user so that the proper pronunciation is conveyed. This can save the

speaker any embarrassment that may result from mispronunciation.

5.

Stylus

Some electronic dictionaries allow the user to write on a screen with a

stylus implement and then have the dictionary find and define the word or

symbol. These are especially useful in languages that utilize other symbols

that may be unfamiliar to the user, such as Kanji (Japanese) or Hebrew letters.

6.

Data Transport

Electronic dictionaries can come with USB storage capabilities that can

be loaded onto other devices. The dictionary serves as a memory card of sorts,

and this can be used to share specific vocabulary or translation lists with

other devices.

7.

Learning Programs

Another great feature of electronic dictionaries for students is the

learning programs that are included on some models. These programs can include

mini-lessons along with self-testing options to help the user improve their

vocabulary knowledge. These programs are of great use for those who are

preparing for standardized tests such as the SATs and ACTs.

8.

Encyclopedia

Some electronic dictionaries come with encyclopedia information, which

provides overviews of a variety of topics. While it may not be an entirely

necessary function for some users, encyclopedias can also round out the context

of dictionary definitions.

9.

Built-in Camera

As one of the more unique features of an electronic dictionary, a

built-in camera can be used to take a photograph of an unfamiliar word in a

text, on a sign, or in any other print form, in order to search for and define

the word. This definition can be in English or in another language, provided

that the electronic dictionary also has that language available.

10.

Added Features

Several extras that usually are available with electronic devices can

include calculators, currency converters, and alarm clocks. Those who are

looking to purchase an electronic dictionary should prioritize their own needs

and find a device that best meets these individual needs [19, 217].

1.3 Teaching Young learners

Young children

tend to change their mood every other minute, and they find it extremely

difficult to sit still. On the other hand, they show a greater motivation than

adults to do things that appeal to them. Since it is almost impossible to cater

to the interests of about 25 young individuals, the teacher has to be inventive

in selecting interesting activities, and must provide a great variety of them.

My teaching approach is neither purely communicative nor audio-lingual (AL); it

also involves features of total physical response (TPR), which is particularly

appropriate for young children. I do not consider any of the abovementioned

approaches sufficient of itself to bring about a high degree of language

proficiency in the learner. The goal is to achieve communicative competence,

but the manner of teaching includes audio-lingual features, such as

choral/single drills, and activities deriving from TPR [21, 16].

The lesson I

will describe is designed for eight- to ten-year-olds at the beginning level.

The topic of the unit is Everyday Life. The learners must describe their day

and what is going on at home at certain times. The grammatical focus is on the

present tenses (simple and continuous). As the present continuous does not

exist as a tense form in the students’ native language (German), the teacher

must make the time reference very clear to them. The present continuous has

several functions, but, since the new form is challenging enough, we will stick

to the present time reference and will focus only on action in process. The

structural pattern of the verb is also new. In order to automatize it several

drills are necessary. Having set up the lesson plan as shown on the next page,

we can now discuss it step by step. The discussion follows the order of the lesson

plan [18, 49].

Warm-up

This step is

essential in preparing the learners for the lesson. Imagine that their previous

lesson was mathematics or history, and how far away their thoughts may be from

English. My experience shows that children respond enthusiastically to songs

and welcome them as a warm-up activity. Using songs in the classroom has a

whole range of advantages. Some of them are listed by Garcia-Saez , e.g.,

creating a positive feeling for language learning, awakening interest during

the lesson, stimulating students to greater oral participation, and breaking

the monotony of the day. The song chosen for this lesson («Are you sleeping,

are you sleeping…») has an additional function: when singing the song, the

learners are using the new tense form subconsciously; thus, it breaks the ice

in introducing difficult and strange grammar [15, 176].

Introduction

The purpose of

the next step is to familiarize the students with the topic. Although to the

learners switching to the picture (we chose one with a boy reading a book and

dreaming of being the leading character) seems to be coincidental and only

topic-related, the teacher has two other purposes: to introduce the idea of

describing a picture, and to have the learners continue using the new grammatical

form subconsciously. This step consists of informal teacher-learner talk and

leads directly to the following stage. Goal Setting «There is an old rule in

theatre that, when the house lights go down, the audience is never to be left

in the dark for more than a brief moment. A ray of light is shown on the

curtain even before it opens.» These metaphoric words are used by Meyer and

Sugg to explain the need of clear goal setting in a lesson. Students should

always, at all stages, know what they are doing and why they are doing it. This

is necessary not only so they will feel a certain satisfaction about their

achievement at the end of the lesson, but also for good motivation throughout

the lesson. Research has also shown that students are more attentive to their

work if the teacher explains the goals of the lesson. The goal for this lesson

is skill oriented, whereas the new grammar feature serves only as a means to

achieve this goal. This communicative goal setting derived from my personal

experience, as will be seen in the following stage [6, 247].

Presentation of the New

Grammatical Item in Context

I still remember

vividly my English teacher in high school destroying any motivation and

enthusiasm I had by opening the lesson with the unforgettable phrase «Today we

are dealing with grammar.» The same unpleasant feeling came over me years

later, when, as a young, inexperienced teacher, I was approached by one of my

pupils, who shyly asked me «Machen wir heute etwa Grammatik?» («Are we dealing

with grammar today?»). It took a while to get rid of that feeling-not by making

students get used to such phrases but by showing them a different, more

integrated and communicative approach to grammar. I try to make the learner

conscious of what s/he is already able to use sub/unconsciously. That means

that the grammatical structures have already been used by the students

(sometimes only in repeating the teacher’s words) before they are explained. In

the lesson I am describing, the learners had used the pres ent continuous in

the song and in the t-l talk about the picture. For elicitation the teacher

could use either his/her questions to the students (e.g., What is he reading?)

or the students’ (correct) answers. Of course, the teacher should always

provide more than one or two examples.

Explanation

In the

explanation phase students are forced to think about the elicited sentences and

analyses them for themselves. The teacher’s questions serve as hints or clues

to point the learner in the right direction. I always prefer a cognitive,

inductive approach, which involves the learners in analysing and explaining the

use and form of a structure, because this supports their understanding of it.

In this lesson, at this early stage of language learning, the teacher might be

justified in switching to the mother tongue both to save time and to keep

things from getting too complicated. The Natural Approach to language learning

holds that only acquired (in contrast to learned) knowledge is effective in

use, while knowledge of rules applies only to monitoring the language output; nevertheless,

it is thought that familiarity with language rules and their automatisation

will facilitate the language-learning process. In my experience, students do

not hesitate to make use of structures they have learned once and automatised

to such a degree that they are able to use them subconsciously. In learning the

present continuous, German students are faced with an item that does not exist

in their mother tongue. Contrastive Analysis would predict difficulty in

acquiring and using this structure. In fact, I have never had problems in

introducing the students to this tense form; it causes only minor difficulty as

compared to other structures. Moreover, they tend to overuse it. We will now

switch to the practice stage of the lesson. The view of practice I prefer can

be adapted from the traditional one:

PRESENT ⇒

CONTROLLED PRACTICE ⇒ FREE PRACTICE into: SUBCONSCIOUS USE ⇒

ELICITATION ⇒ CONTROLLED PRACTICE ⇒

FREE PRACTICE

Littlewood

divides activities into pre-communicative and communicative activities. Using

his terminology we will start with purely pre-communicative activities.

Formal Drill

The

controlled-practice phase of the lesson starts with a simple repetition of the

new language feature in different variations. In order to distract the young

learners from the «grammar» point, a jazz-chant variation is used as a first

drill:

I’m saying: Hsh, Hsh. Tom 1 is

sleeping. What are you saying? I’m saying: Hsh, hsh. Tom is sleeping. Who is

sleeping? Tom is sleeping, he is sleeping. Is he sleeping? Yes, he is.

Aaaaa…not any more.

Based on the

work of Graham , this short jazz chant reinforces the present-continuous

structure. As Graham points out, jazz chants are highly motivating because of

their rhythms and humor. In addition, the young learners need not patiently

remain in their seats. They can move, clap their hands, snap their fingers, or

tap their feet; they are involved both mentally and physically. Songs, poems,

chants, and similar activities reduce anxiety and increase the personal

involvement of second-language learners. This kind of practice is certainly not

a «formal drill» of the traditional stimulus-response kind.

Pair Work

So far, the

learners have, for the most part, only had to respond to the teacher’s stimuli.

Now the mode is changing from teacher-centered to learner-centered. The

learners depend more on each other and engage in interactive tasks. Certainly,

the pair-work activity at this stage belongs to the pre-communicative

activities in Littlewood’s taxonomy. But even this kind of mini-dialogue can

support the learners’ speaking proficiency. The pattern that the teacher may

introduce as a model to guide the students can, for example, have the following

structure using appropriate flash cards:

What’s going on

here? They are speaking. What is she doing? She is singing. or by adding

adverbs (if they are already known): How is he singing? He is singing loudly.

or using yes/no questions: Is the sun shining? Yes, it’s shining. / No it’s

raining.

Some

of the phrases have already been practiced in the jazz chant and the previous

exercise. The illustrations on the flash cards serve two purposes. First of

all, they «can be quite helpful in creating the motivating, game-like

atmosphere so conducive to learning»), and secondly, they provide visual

support for the speaking activity. Learners are expected to create a certain

level of awareness when they perform, i.e., they have to consciously make use

of the new structure, but they also have to focus on meaning and probably shift

from «focus on form» to «focus on meaning» during the practice period. In

exchanging the flash cards and performing dialogues with more than one exchange

learners also get involved with such features of conversation as turn-taking.

Because pair work is learner centered, the teacher’s role is less dominant. The

teacher must monitor the learners’ performance in order to provide feedback and

help where necessary. S/he can also take part in the conversation as a

participant.

Group Work

The next stage

of the lesson switches from oral activities to writing. For developing writing

skills we use the process approach. This group activity presents the learners

with a task that becomes gradually less difficult, preparing them for the more

challenging goal at the end of the lesson. A cooperative (in contrast to

competitive and individualistic) goal structure helps students achieve greater

success in group-work activities , as well as educating children to be more

cooperative. In our lesson the group must first discuss the appropriate time

for each action and then write up the activities. Each group is given a

different set of pictures and times, so that the ultimate success of the story

depends on the participation of each group. As an outcome of the group work

they write their sentences on an OHP foil, which makes the evaluation phase far

easier and visible to the whole class. Following the sub processes of writing,

this stage belongs to the prewriting phase. Several structural drills are

demanded as a prewriting activity. The actual writing task at the lesson end is

subdivided, too, as we will see.

Writing

The first step

is to re-introduce the picture. This re-introduction should achieve familiarity

with the subject, i.e., the description of the picture. (We chose a picture

showing a typical German family at the Sunday morning breakfast table.) The

teacher should not use a formal expression like «Let’s describe the picture

now,» but should use words that call attention to the content more than the

form, e.g., «Look, what is going on one Sunday morning in this family? What can

you see? First, let’s find some names for the people….» Thus, the learners will

focus more on the content of the picture. They may use words that don’t go in

the direction the teacher wants to lead them, but a friendly teacher-learner /

learner-teacher talk can inspire motivation and the enthusiasm to communicate.

For the prewriting phase many activities, such as exchange of experiences,

thinking, remembering, talking, reading, or noting, are required. The students

will not stick to using only the present continuous, but remember, it is only

one means to achieve the goal.

The next step in

this process could be the description of just one person, e.g., the boy. The

learners have to do this in writing. One pupil could, for instance, write on

the blackboard as an example for discussion afterwards. The teacher could then

change the mode again and ask the students to describe orally either one more

person or the whole picture, using their written notes as a beginning. Another

possibility is to start with the beginning sentences from the blackboard and

carry on, involving different students in a sequence. The teacher can collect

catchwords from the students and note continue

this activity, depending on classroom circumstances and the particular

learners. In any case it might be supportive for the learners to find some

words or phrases to help them write it up. As we cannot expect, in a 45-50

minute lesson, to finish this work, the teacher should have the students complete

it as homework. It might be a good start for the next lesson to compare the

different stories that the pupils come up with. She can then go ahead with more

authentic situations for using the present continuous, either in the form of

dialogues or simply in describing different actions, e.g., «Look out of the

window and tell me what’s going on in the street.»

Conclusion to the 1st

chapter. In the 1st

chapter we defined the term of e-dictionary, its types and history. We found

scholars from different countries and studied their articles, books.

2.

ACTIVITIES USING E-DICTIONARIES

2.1

E-dictionaries for developing listening and speaking

With the purpose of exploring the effectiveness

of the computer dictionaries and encyclopedias there the experimental teaching

in 10th grades of the Karaganda high school was conducted. The number of

participants was 40 where the 10 «a» class was an experimental group and the 10

«b» class — control group. The main criteria of selection of participants of

the experiment were level of English Proficiency, level of computer literacy

and age. So, to identify the level of English there has been presented the

pretest that consists of three stages: grammar-vocabulary test, listening

comprehension tasks and speaking on the curriculum topics. The age of the

participants was 16 years old. It was agreed to use computer dictionaries for

in-class activities and computer encyclopedias for out-of-class work in ESL

teaching in a short-term view. In the frame of the main objective of the

research the main tasks of experimental teaching were the following:

—

to teach school students to work with electronic

dictionaries and translation systems;

—

to teach school students to study English with the

help of computer dictionaries;

—

to lead the comparative analysis of work with traditional

and computer dictionaries;

—

to conclude the result and offer the recommendations.

The criteria of the estimation of the

experimental teaching have been allocated the time, during which students would

be making the tasks; the speed, with which work would have been done and the correctness

of results of the done assignments. The teaching and learning process has been

researched in two high school classes, in which in one class there was teaching

with the use of traditional dictionaries and in another one — the use of computer

dictionaries. The experiment lasted a half of one school term (one month).

The task that was given to the students was to practice

the new lexical units on the module: «What do you like?», «What’s best in your

country?»; to listen and to comprehend the content of the texts translating

with use of the dictionary «Lingo» and speak on the topic using the studied

words and word expressions. At the lessons there has been used the multimedia

base of the interactive whiteboard (IWB), which is known as a touch-sensitive projection

screen that allows the teacher to control a computer directly by touching the

screen. The IWB is a convenient modern tool for effective academic purposes,

business presentations, and seminars. It not only combines advantages of the

big screen and marker boards, but also allows to keep all marks and the changes

made during discussion and even to operate computer applications, not

interrupting performance and providing access to resources of the Internet.

The results of the experimental teaching are

reflected in Tables 1, 2 and show that the quality of learning with the use of

computer dictionary «Lingo» is much high than the quality of learning with the

use of traditional dictionaries, that is presented in the

Diagram B.

Table1: Indexes of the quality of the learning

progress of the 10 «A» class

|

Week number |

Respondents |

Respondents |

% of the |

|

1 |

20 |

7 |

35% |

|

2 |

20 |

9 |

45% |

|

3 |

20 |

11 |

55% |

|

4 |

20 |

9 |

45% |

|

Total |

45% |

Table 2: Indexes of the quality of the learning

progress of the 10 «B» class

|

Week number |

Respondents |

Respondents |

% of the |

|

1 |

20 |

11 |

55% |

|

2 |

20 |

15 |

75% |

|

3 |

20 |

14 |

80% |

|

4 |

20 |

17 |

85& |

|

Total |

71% |

Diagram B. Comparative analysis of the quality of

learning in the group 10 «B» and group 10 «A»

The qualitative and quantitative analysis of the

experimental teaching with the use of computer dictionaries suggests that the

time spent by the students of the experimental group on doing tasks is less

than that of the control one. The speed of learning materials is higher in

experimental group than in the control one, and the correctness of answers more

often corresponds to the sample. The criteria of assessment allow judging a

degree and quality of developed skills of the students. The use of the computer

dictionary in educational process allows expanding the borders of the

traditional lesson where the students are in direct contact with the teacher

and get necessary support only from him, but also promotes to increase of the

students’ interest to independent work with the language material. It is

necessary to note the shortening of time in doing tasks, and also in deleting a

gap between, so-called, «strong» and «weak» students. It was observed that

there was a great interest of the weak students thanks to study with the use of

computer dictionaries. It was found out that it reduced probability of

duplication of students’ answers while translating and develops a language

guess in selection of a suitable word equivalent. Thus, using of computer

dictionaries at the foreign language lessons is one of the relatively new means

of raising pupils’ motivation to foreign languages learning, developing of

self-directed work of pupils and multilingual perception of language units.

The research on the determination of the role of

Wikipedia has been realized with the same tenth grade students. The task given

to the students, which was out of class activity, was to expanding the

students’ knowledge in the frame of cultural aspect of foreign language

learning. The lesson was organized in the form of the game and devoted to a

theme «The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland». The analysis

of work with Wikipedia in out-of-class activity allows defining the great role

of Wikipedia materials, which are authentic, and that is highly important for

language learning. During the activity there were being involved four language

skills: listening and reading comprehension skills, speaking and writing skills

as well. There were the following tasks with texts taken from the computer

encyclopedia: finding the main idea, analysis, annotation, synthesis and

compression of the information, development of grammatical terminology,

translation of texts from English to Russian.

2.2 Activities using

e-dictionary

This activities great

for looking up words and you will use them to teach dictionary

skills, but there are also other great things you can do

with these rather large volumes of words. Here are just a few ideas.

|

Activities |

Explanation |

|

|

1 |

Play Speed Word Search. |

Give each student or pair of students a dictionary. When you call out |

|

2 |

Play Mystery Word |

1. |

|

3 |

Play Dictionary Dig |

2. |

|

4 |

Collect New Words |

Have each student keep a notebook of new words. This is a nice |

|

5 |

Make up New Words |

Ask each student make up a new word and definition. Have each student |

|

6 |

Estimate and Measure |

Have the students stack all of the dictionaries into |

|

7 |

Line Them Up Like Dominoes |

3. |

2.3 An Experiment Using

Electronic Dictionaries with EFL Students

The two outstanding differences

between electronic dictionaries (EDs) and paper dictionaries (PDs) are size,

weight and cost. For example, the Seiko TR-7700 ED contains the contents of the

Kenkyusha New College English to Japanese and Japanese to English paper

dictionaries. It weighs less than one eighth of its paper counterpart, and

costs over 5 times as much. Do EDs have any other advantages that justify the

extra cost? Should we recommend to students that they buy one?

An

important factor for most learners is whether the dictionary is quick and easy

to use. We set up a simple classroom experiment to compare the look-up speed of

paper and electronic dictionaries.

Objective

The objective of the experiment was

purely look-up speed; i.e. how quickly students could find the definition(s) of

an unknown word. We took no account of the quality or number of definitions,

nor even students’ ability to read and comprehend them.

Method

We divided a first year English

conversation class into two groups. We gave a paper bilingual dictionary to

each student in the PD group and an electronic dictionary to each student in

the ED group.

Three

lists of ten words were prepared with each list containing words with the same

initial letters and the same number of letters per word.

Table 1: The word lists.

|

List A |

List B |

List C |

|

Cool |

Cost |

Chop |

|

Fame |

Feel |

Fish |

|

Peel |

Pair |

Page |

|

Search |

School |

Screen |

|

Coffee |

Cookie |

Copper |

|

Ladder |

Leader |

Letter |

|

Attitude |

Argument |

Approval |

|

Ignorant |

Illusion |

Immature |

|

Parallel |

Paranoid |

Parasite |

We

gave students as much time as they needed to look up the words on List A. In

practice, this was about ten minutes. This was to let students get used to the

particular PD or ED they would use in the test. The actual test didn’t begin

until all students felt comfortable with their dictionary.

Then,

we gave the PD students copies of List B and the ED students copies of List C,

face down. At the start command, they turned over their papers and looked up

each word in order. They were told not to take time to read any definitions. As

each student finished the list, she raised her hand, and we recorded the time

taken.

Finally,

when all the students had finished, they changed places with a student in the

other group, leaving the dictionaries and the word lists, face down, on their

desks. They then looked up the ten words on the other list with the other type

of dictionary.

The

experiment was repeated with several first year English conversation classes.

Results

The average look-up time for ten

words using a PD was 168 seconds (about 17 seconds per word); using an ED, 130

seconds (about 13 seconds per word) . In short, our students could look up

words about 23% faster with an ED.

Objective and Method

Our show-of-hands survey of 781

students at Kyoritsu Women’s University and College found that 88 (about 11%)

owned an ED. We asked those students to complete a questionnaire (Appendix 1)

there and then, in class.

The

questionnaire asked students how often, where, and when they use their EDs, and

whether for English to Japanese translation or vice versa. It also asked

students for their attitude to their ED’s features, specifically the

pronunciation feature, if present. The answers to these questions were

impressionistic; we did not ask respondents to observe their dictionary use

quantitatively before completing the questionnaire.

When

we designed the questionnaire we were not investigating a particular

hypothesis; what follows emerged clearly from the data gathered.

Result and discussion

Six returns were invalid for various

reasons; the results are based on the remaining 82 usable questionnaires.

Where?

Given that they are much smaller and

lighter than content equivalent paper dictionaries (PDs), we were surprised to

find that students rarely use their EDs on the move. Most students use them

both at home and in the classroom, roughly 50% in each place. The heaviest

users claim to use them slightly more at home. Over half of respondents claimed

never to use their ED’s while traveling. Well over half couldn’t think of any

other places they used them, with the most common exception (only 11 out of 82)

being the library. Given the relatively high cost of EDs, it would be cheaper

for most of our respondents to buy two PDs, and keep one at home and one in a

locker at school. In hindsight, it would have been useful to know why these

students own an ED — did they buy it themselves (why?) or was it an unsolicited

gift?

When?

As our experiment demonstrated, EDs

can be somewhat faster, but this small speed difference is probably not enough

to justify their extra cost when looking up the words needed to understand an

L2 reading passage or write a report in L2 for homework. However, it is for precisely

these activities that most of our respondents use their EDs the most.

On

the other hand, the 23% speed difference could be a decisive factor when trying

to follow the content of a conversation, lecture or TV program. However, the

questionnaire showed that almost none of our respondents takes advantage of her

ED’s superior look-up speed when speaking in or listening to the L2.

It

is interesting to compare the rank order of students’ ED usage, as revealed by

the questionnaire, to what is generally considered to be the natural order of

language acquisition, at least in children learning their L1. They are opposite

(see Table 2).

Table 2: Natural Order of Acquisition vs. Student

Usage of EDs

|

Rank Order |

Natural Order of |

Student Usage of |

|

1 |

Listening |

Reading |

|

2 |

Speaking |

Writing |

|

3 |

Reading |

Speaking |

|

4 |

Writing |

Listening |

If

learners are trying to master English for communicative purposes, as many claim

to be, then using their ED’s counter to the natural order of acquisition is

like swimming upstream.

Why Do Our Students Make so Little

Use of EDs When Listening?

The most obvious explanation is that

they do very little listening anyhow. Although this is impossible to verify

from our questionnaire results, we know that most of the respondents are

literature or international studies majors, not conversation school students.

Consequently, they are following curricula which require much more reading and

writing than listening or speaking. Habits acquired in school would also tend

to bias students towards a preference for reading and writing. Further,

practical considerations (e.g., living in an L1 environment) minimize the need

to deal with aural input.

A

second explanation is that students do not trust their ability to catch

correctly the words that they do hear; perhaps rightly so. For example:

-

I

say, «I feel empathy. « -

She

hears, «I feel empty. « - I offer, «Ice cream ? «

- She wonders, «I scream ? «

What Good Does It Do to Look Up an Unknown Word if the

Word Itself is Misunderstood?

A third explanation involves the

irrational English spelling system. Even if the listener hears the unknown word

correctly, she cannot necessarily spell it correctly. This is less of an

obstacle these days thanks to the error tolerant and similar input functions of

modern EDs. These features allow the user to input her best guess as to a

word’s spelling, then choose the target word from a list of likely candidates

displayed on the screen.

Pronunciation Function

Respondents’ enthusiasm for hearing

their ED pronounce words was not high. While a few felt this function was

«very important», the vast majority felt it was only «somewhat

important» or «not important», suggesting that few students have

any intention of actually trying to say their newly acquired words.

Conclusion to the 1st

chapter.

A new technology tends to be used in the same

way as the traditional technology it supersedes. For many years during the

twenties and thirties, movies were vaudeville and stage shows on a big screen.

The earliest computer assisted language learning packages were little more than

textbooks on a small screen.

At

present, electronic dictionaries are still fundamentally paper dictionaries on

a microchip. They have certain unique functions, such as error tolerant input,

cross-referencing (e.g. synonyms and antonyms), and word and spelling games,

and they are probably faster to use. On the other hand, some people simply