English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- oeconomy, œconomy (obsolete)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English yconomye, yconomy, borrowed via Old French [Term?] or Medieval Latin[1] from Latin oeconomia, from Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomía, “management of a household, administration”), from οἶκος (oîkos, “house”) + νέμω (némō, “distribute, allocate”) (surface analysis eco- + -nomy). The first recorded sense of the word economy, found in a work possibly composed in 1440, is “the management of economic affairs”, in this case, of a monastery.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /iːˈkɒn.ə.mi/

- (General American) enPR: ĭkŏʹnəmē, əkŏʹnəmē IPA(key): /iːˈkɑ.nə.mi/, /ɪˈkɑ.nə.mi/, /əˈkɑ.nə.mi/

- Rhymes: -ɒnəmi

Noun[edit]

economy (countable and uncountable, plural economies)

- Effective management of a community or system, or especially its resources.

- (obsolete) The regular operation of nature in the generation, nutrition and preservation of animals or plants.

- animal economy, vegetable economy

- (obsolete) System of management; general regulation and disposition of the affairs of a state or nation, or of any department of government.

- (obsolete) A system of rules, regulations, rites and ceremonies.

- the Jewish economy

- (obsolete) The disposition or arrangement of any work.

- the economy of a poem

- (obsolete) The regular operation of nature in the generation, nutrition and preservation of animals or plants.

- The study of money, currency and trade, and the efficient use of resources.

- Frugal use of resources.

- economy of word

- April 5, 1729, Jonathan Swift, letter to St. John

- I have no other notion of economy than that it is the parent to liberty and ease.

- The system of production and distribution and consumption. The overall measure of a currency system; as the national economy.

-

2013 August 31, “Horns of a trilemma”, in The Economist, volume 408, number 8851:

-

An economy open to free movement of capital can keep a fixed exchange rate, for example, only by subjugating monetary-policy goals to its defence—by raising interest rates sharply, say, when capital outflows put downward pressure on the currency. Yet the trilemma also implies that an economy can enjoy both free capital flows and an independent monetary policy, so long as it gives up worrying about its exchange rate.

-

-

- (theology) The method of divine government of the world. (See w:Economy (religion).)

- (US) The part of a commercial passenger airplane or train reserved for those paying the lower standard fares; economy class.

- (archaic) Management of one’s residency.

Derived terms[edit]

- agroeconomy

- bioeconomy

- black economy

- circular economy

- collaborative economy

- command economy

- dual economy

- e-economy

- economic

- economical

- economist

- economize

- economy car

- economy class

- economy class syndrome

- economy model

- economy of scale

- economy picking

- economy rate

- economy rice

- false economy

- fuel economy

- gift economy

- gig economy

- Goldilocks economy

- hydrogen economy

- lithium economy

- market economy

- mixed economy

- natural economy

- peer-to-peer economy

- planned economy

- policy economy

- political economy

- premium economy

- quaternary sector of the economy

- reputation economy

- service economy

- sex economy

- sharing economy

- subsistence economy

- tiger economy

- token economy

- transition economy

[edit]

- economics

- macroeconomics

- microeconomics

Translations[edit]

frugal use of resources

- Arabic: اِقْتِصَاد (ar) m (iqtiṣād)

- Armenian: տնտեսում (hy) (tntesum), խնայողություն (hy) (xnayołutʿyun)

- Azerbaijani: qənaət

- Bavarian: Wirtschafd

- Belarusian: экано́мія f (ekanómija), ашча́днасць f (aščádnascʹ), беражлі́васць f (bjeražlívascʹ)

- Bulgarian: пестели́вост (bg) f (pestelívost)

- Czech: úspornost f

- Danish: økonomi (da) c

- Dutch: economie (nl) f

- Finnish: taloudellisuus (fi)

- French: économie (fr) f

- German: Wirtschaft (de) f, Ökonomie (de) f

- Greek: οικονομία (el) f (oikonomía)

- Hindi: किफ़ायत f (kifāyat)

- Icelandic: hagsýni f, nýtni f, ráðdeild f, sparnaður m

- Irish: barainneacht f

- Italian: economia (it) f, risparmio (it) m

- Latvian: ekonomija f

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: хэмнэлт (xemnelt)

- Norman: êconomie f

- Portuguese: economia (pt) f, frugalidade (pt) f

- Russian: эконо́мия (ru) f (ekonómija), бережли́вость (ru) f (berežlívostʹ), экономи́чность (ru) f (ekonomíčnostʹ)

- Sicilian: sparagnu m

- Swedish: ekonomi (sv) c, hushållning (sv) c

- Turkish: ekonomi (tr), iktisat (tr), tutum (tr)

- Ukrainian: еконо́мія (uk) f (ekonómija), бережли́вість (uk) f (berežlývistʹ), еконо́мність f (ekonómnistʹ), оща́дливість f (oščádlyvistʹ)

- Urdu: کِفایَت f (kifāyat)

- Vietnamese: sự tiết kiệm (vi)

production and distribution and consumption

- Afrikaans: ekonomie (af)

- Albanian: ekonomi (sq) f

- Arabic: اِقْتِصَاد (ar) m (iqtiṣād)

- Armenian: տնտեսություն (hy) (tntesutʿyun), էկոնոմիկա (hy) (ēkonomika)

- Azerbaijani: iqtisadiyyat (az)

- Bashkir: иҡтисад (iqtisad)

- Bavarian: Wirtschafd

- Belarusian: экано́міка f (ekanómika), гаспада́рка (be) f (haspadárka)

- Bengali: অর্থনীতি (bn) (orthoniti)

- Bulgarian: иконо́мика (bg) f (ikonómika)

- Burmese: စီးပွားရေး (my) (ci:pwa:re:)

- Catalan: economia (ca) f

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 經濟/经济 (ging1 zai3)

- Dungan: җинҗи (žinži)

- Hakka: 經濟/经济 (kîn-chi)

- Mandarin: 經濟/经济 (zh) (jīngjì)

- Min Dong: 經濟/经济 (gĭng-cá̤)

- Min Nan: 經濟/经济 (zh-min-nan) (keng-chè)

- Wu: 經濟/经济 (jin ji)

- Czech: ekonomika (cs) f, hospodářství (cs) n

- Danish: økonomi (da) c

- Dhivehi: އިޤްތިޞާދު (iqtişādu), މައީށަތް (maīṣat̊)

- Dutch: economie (nl) f

- Estonian: majandus (et)

- Faroese: búskapur m

- Finnish: talous (fi)

- French: économie (fr) f

- Fula:

- Adlam: 𞤬𞤢𞤺𞥆𞤵𞤣𞤵

- Roman: faggudu

- Georgian: ეკონომიკა (eḳonomiḳa)

- German: Wirtschaft (de) f, Ökonomie (de) f

- Greek: οικονομία (el) f (oikonomía)

- Hebrew: כַּלְכָּלָה (he) f (kalkalá)

- Hindi: अर्थव्यवस्था (hi) f (arthavyavasthā), किफ़ायत f (kifāyat)

- Hungarian: gazdaság (hu)

- Icelandic: atvinnulif n, efnahagslíf n

- Ido: ekonomio (io)

- Indonesian: ekonomi (id)

- Irish: geilleagar m

- Italian: economia (it) f

- Japanese: 経済 (ja) (けいざい, keizai)

- Kazakh: экономика (ékonomika), ықтисат (yqtisat)

- Khmer: សេដ្ឋកិច្ច (km) (seetthaʼkəc)

- Korean: 경제(經濟) (ko) (gyeongje)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: îqtisad (ku) f, ekonomî (ku) f, aborî (ku) f

- Kyrgyz: экономика (ky) (ekonomika)

- Lao: ເສດຖະກິດ (lo) (sēt tha kit)

- Latvian: ekonomika (lv) f

- Lithuanian: ekonomika (lt) f

- Macedonian: економија (mk) f (ekonomija)

- Malay: ekonomi (ms)

- Malayalam: സമ്പദ്ഘടന (sampadghaṭana), സമ്പദ്വ്യവസ്ഥ (sampadvyavastha)

- Maltese: ekonomija f

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: эдийн засаг (ediin zasag), аж ахуй (až axuj)

- Mongolian: ᠡᠳ᠋ ᠦᠨ

ᠵᠠᠰᠠᠭ (ed—ün ǰasag), ᠠᠵᠤ

ᠠᠬᠤᠢ (aǰu aqui̯)

- Norman: êconomie f

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: økonomi (no) m

- Occitan: economia (oc) f

- Ossetian: экономикӕ (èkonomikæ)

- Pashto: وټه (ps) f (wëṭa), اقتصاد (ps) m (eqtesãd)

- Persian: اقتصاد (fa) (eqtesâd)

- Polish: ekonomia (pl) f

- Portuguese: economia (pt) f

- Romanian: economie (ro) f

- Russian: эконо́мика (ru) f (ekonómika), хозя́йство (ru) n (xozjájstvo)

- Scottish Gaelic: eaconomaidh m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: привреда, економија f, господарство n

- Roman: privreda (sh) f, ekonomija (sh) f, gospodarstvo (sh) n

- Shan: ပၢႆးမၢၵ်ႈမီး (shn) (páai māak míi)

- Sicilian: ecunumìa (scn) f, mircatu (scn) m

- Sinhalese: අරපරික්සම (arapariksama)

- Slovak: ekonomika (sk) f, hospodárstvo n

- Slovene: gospodarstvo (sl) n

- Spanish: economía (es) f

- Swedish: ekonomi (sv) c, hushållning (sv) c

- Tagalog: ekonomiya (tl), kapamuhayan

- Tajik: иқтисодиёт (iqtisodiyot), иқтисод (iqtisod)

- Tatar: икътисад (iqtisad)

- Thai: เศรษฐกิจ (th) (sèet-tà-gìt)

- Tibetan: དཔལ་འབྱོར (dpal ‘byor)

- Turkish: ekonomi (tr), iktisat (tr), denlik

- Turkmen: ykdysadyýet

- Ukrainian: еконо́міка (uk) f (ekonómika), господа́рство n (hospodárstvo)

- Urdu: مَعِیشَت f (ma’īśat), اِقْتِصاد (iqtisād), اِقْتِصادِیات pl (iqtisādiyāt)

- Uyghur: ئىقتىساد (iqtisad)

- Uzbek: iqtisodiyot (uz), ekonomika (uz), iqtisod (uz)

- Vietnamese: kinh tế (vi)

- Yiddish: עקאָנאָמיע (ekonomye)

Translations to be checked

- Estonian: (please verify) majandus (et)

- German: (please verify) Binnenwirtschaft

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: (please verify) ئابووری (abûrî)

- Northern Kurdish: (please verify) aborî (ku) f, (please verify) ekonomî (ku) f, (please verify) îqtisad (ku) f

- Latin: (please verify) oeconomia (la), (please verify) œconomia f

- Luxembourgish: (please verify) Ökonomie f

- Malayalam: (please verify) സമ്പദ് (sampadŭ)

- Norwegian: (please verify) økonomi (no) f

- Turkish: (please verify) ekonomi (tr)

Adjective[edit]

economy (not comparable)

- Cheap to run; using minimal resources; representing good value for money; economical.

- He bought an economy car.

- Economy size.

Adverb[edit]

economy (not comparable)

- (US) In or via the part of a commercial passenger airplane reserved for those paying the lower standard fares.

- Numerous web sites have tips on how to fly economy.

Translations[edit]

cheap to run

- Portuguese: económico (pt) (Portugal), econômico (pt) (Brazil)

- Russian: эконо́мный (ru) (ekonómnyj)

- Spanish: económico (es)

- Swedish: ekonomisk (sv)

References[edit]

- ^ “īconomī(e, n.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007.

Anagrams[edit]

- monoecy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the word in goods and services meaning. For other uses, see Economy (disambiguation).

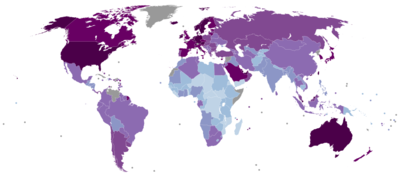

Gross domestic product per capita of countries (2020)

- >50,000

- 35,000–50,000

- 20,000–35,000

- 10,000–20,000

- 5,000–10,000

- 2,000–5,000

- <2,000

- Data unavailable

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the production, use, and management of scarce resources.[1] A given economy is a set of processes that involves its culture, values, education, technological evolution, history, social organization, political structure, legal systems, and natural resources as main factors. These factors give context, content, and set the conditions and parameters in which an economy functions. In other words, the economic domain is a social domain of interrelated human practices and transactions that does not stand alone.

Economic agents can be individuals, businesses, organizations, or governments. Economic transactions occur when two groups or parties agree to the value or price of the transacted good or service, commonly expressed in a certain currency. However, monetary transactions only account for a small part of the economic domain.

Economic activity is spurred by production which uses natural resources, labor and capital. It has changed over time due to technology, innovation (new products, services, processes, expanding markets, diversification of markets, niche markets, increases revenue functions) such as, that which produces intellectual property and changes in industrial relations (most notably child labor being replaced in some parts of the world with universal access to education).

Etymology

The word economy in English is derived from the Middle French’s yconomie, which itself derived from the Medieval Latin’s oeconomia. The Latin word has its origin at the Ancient Greek’s oikonomia or oikonomos. The word’s first part oikos means «house», and the second part nemein means «to manage».[2]

The most frequently used current sense, denoting «the economic system of a country or an area», seems not to have developed until the 1650s.[3]

History

Earliest roots

Ancient Roman mosaic from Bosra, depicting a merchant leading camels through the desert

As long as someone has been making, supplying and distributing goods or services, there has been some sort of economy; economies grew larger as societies grew and became more complex. Sumer developed a large-scale economy based on commodity money, while the Babylonians and their neighboring city states later developed the earliest system of economics as we think of, in terms of rules/laws on debt, legal contracts and law codes relating to business practices, and private property.[4]

The Babylonians and their city state neighbors developed forms of economics comparable to currently used civil society (law) concepts. They developed the first known codified legal and administrative systems, complete with courts, jails, and government records.[5]

The ancient economy was mainly based on subsistence farming.[6] The Shekel are the first to refer to a unit of weight and currency, used by the Semitic peoples. The first usage of the term came from Mesopotamia circa 3000 BC. and referred to a specific mass of barley which related other values in a metric such as silver, bronze, copper, etc. A barley/shekel was originally both a unit of currency and a unit of weight, just as the British Pound was originally a unit denominating a one-pound mass of silver.[7]

For most people, the exchange of goods occurred through social relationships. There were also traders who bartered in the marketplaces. In Ancient Greece, where the present English word ‘economy’ originated,[2] many people were bond slaves of the freeholders.[8] The economic discussion was driven by scarcity.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, what is now known as an economy was not far from the subsistence level. Most exchange occurred within social groups. On top of this, the great conquerors raised what we now call venture capital (from ventura, ital.; risk) to finance their captures. The capital should be refunded by the goods they would bring up in the New World. The discoveries of Marco Polo (1254–1324), Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) and Vasco da Gama (1469–1524) led to a first global economy. The first enterprises were trading establishments. In 1513, the first stock exchange was founded in Antwerp. Economy at the time meant primarily trade.

The European captures became branches of the European states, the so-called colonies. The rising nation-states Spain, Portugal, France, Great Britain and the Netherlands tried to control the trade through custom duties and mercantilism (from mercator, lat.: merchant) was a first approach to intermediate between private wealth and public interest. The secularization in Europe allowed states to use the immense property of the church for the development of towns. The influence of the nobles decreased. The first Secretaries of State for economy started their work. Bankers like Amschel Mayer Rothschild (1773–1855) started to finance national projects such as wars and infrastructure. Economy from then on meant national economy as a topic for the economic activities of the citizens of a state.

Industrial Revolution

The first economist in the true modern meaning of the word was the Scotsman Adam Smith (1723–1790) who was inspired partly by the ideas of physiocracy, a reaction to mercantilism and also later Economics student, Adam Mari.[9] He defined the elements of a national economy: products are offered at a natural price generated by the use of competition — supply and demand — and the division of labor. He maintained that the basic motive for free trade is human self-interest. The so-called self-interest hypothesis became the anthropological basis for economics. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) transferred the idea of supply and demand to the problem of overpopulation.

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport had a profound effect on the socioeconomic and cultural conditions starting in the United Kingdom, then subsequently spreading throughout Europe, North America, and eventually the world.[10] The onset of the Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in human history; almost every aspect of daily life was eventually influenced in some way.

In Europe wild capitalism started to replace the system of mercantilism (today: protectionism) and led to economic growth. The period today is called industrial revolution because the system of Production, production and division of labor enabled the mass production of goods.

20th century

The contemporary concept of «the economy» wasn’t popularly known until the American Great Depression in the 1930s.[11]

After the chaos of two World Wars and the devastating Great Depression, policymakers searched for new ways of controlling the course of the economy.[citation needed] This was explored and discussed by Friedrich August von Hayek (1899–1992) and Milton Friedman (1912–2006) who pleaded for a global free trade and are supposed to be the fathers of the so-called neoliberalism.[12][13] However, the prevailing view was that held by John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who argued for a stronger control of the markets by the state. The theory that the state can alleviate economic problems and instigate economic growth through state manipulation of aggregate demand is called Keynesianism in his honor.[14] In the late 1950s, the economic growth in America and Europe—often called Wirtschaftswunder (ger: economic miracle) —brought up a new form of economy: mass consumption economy. In 1958, John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006) was the first to speak of an affluent society in his book The Affluent Society.[citation needed] In most of the countries the economic system is called a social market economy.[15]

21st century

With the fall of the Iron Curtain and the transition of the countries of the Eastern Bloc towards democratic government and market economies, the idea of the post-industrial society is brought into importance as its role is to mark together the significance that the service sector receives instead of industrialization. Some attribute the first use of this term to Daniel Bell’s 1973 book, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society, while others attribute it to social philosopher Ivan Illich’s book, Tools for Conviviality. The term is also applied in philosophy to designate the fading of postmodernism in the late 90s and especially in the beginning of the 21st century.

With the spread of Internet as a mass media and communication medium especially after 2000–2001, the idea for the Internet and information economy is given place because of the growing importance of e-commerce and electronic businesses, also the term for a global information society as understanding of a new type of «all-connected» society is created. In the late 2000s, the new type of economies and economic expansions of countries like China, Brazil, and India bring attention and interest to different from the usually dominating Western type economies and economic models.

Elements

Types

A market economy is one where goods and services are produced and exchanged according to demand and supply between participants (economic agents) by barter or a medium of exchange with a credit or debit value accepted within the network, such as a unit of currency.[16] A planned economy is one where political agents directly control what is produced and how it is sold and distributed.[17] A green economy is low-carbon and resource efficient. In a green economy, growth in income and employment is driven by public and private investments that reduce carbon emissions and pollution, enhance energy and resource efficiency, and prevent the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.[18] A gig economy is one in which short-term jobs are assigned or chosen on-demand. The global economy refers to humanity’s economic system or systems overall.[citation needed] An informal economy is neither taxed nor monitored by any form of government.[19]

Sectors

The economy may be considered as having developed through the following phases or degrees of precedence:[according to whom?]

- The ancient economy was mainly based on subsistence farming.

- The industrial revolution phase lessened the role of subsistence farming, converting it to more extensive and mono-cultural forms of agriculture in the last three centuries. The economic growth took place mostly in mining, construction and manufacturing industries. Commerce became more significant due to the need for improved exchange and distribution of produce throughout the community.

- In the economies of modern consumer societies phase there is a growing part played by services, finance, and technology—the knowledge economy.

In modern economies, these phase precedences are somewhat differently expressed by the three-sector model:[20]

- Primary: Involves the extraction and production of raw materials, such as corn, coal, wood and iron.

- Secondary: Involves the transformation of raw or intermediate materials into goods e.g. manufacturing steel into cars, or textiles into clothing.

- Tertiary: Involves the provision of services to consumers and businesses, such as baby-sitting, cinema and banking.

Other sectors of the developed community include:

- the public sector or state sector (which usually includes: parliament, law-courts and government centers, various emergency services, public health, shelters for impoverished and threatened people, transport facilities, air/sea ports, post-natal care, hospitals, schools, libraries, museums, preserved historical buildings, parks/gardens, nature-reserves, some universities, national sports grounds/stadiums, national arts/concert-halls or theaters and centers for various religions).

- the private sector or privately run businesses.

- the voluntary sector or social sector.[21]

Indicators

The gross domestic product (GDP) of a country is a measure of the size of its economy, or more specifically, monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced.[22] The most conventional economic analysis of a country relies heavily on economic indicators like the GDP and GDP per capita. While often useful, GDP only includes economic activity for which money is exchanged.[citation needed]

Due to the growing importance of the financial sector in modern times,[23] the term real economy is used by analysts[24][25] as well as politicians[26] to denote the part of the economy that is concerned with the actual production of goods and services,[27] as ostensibly contrasted with the paper economy, or the financial side of the economy,[28] which is concerned with buying and selling on the financial markets. Alternate and long-standing terminology distinguishes measures of an economy expressed in real values (adjusted for inflation), such as real GDP, or in nominal values (unadjusted for inflation).[29]

Studies

The study of economics are roughly divided into macroeconomics and microeconomics.[30] Today, the range of fields of study examining the economy revolves around the social science of economics,[31][32] but may also include sociology,[33] history,[34] anthropology,[35] and geography.[36] Practical fields directly related to the human activities involving production, distribution, exchange, and consumption of goods and services as a whole are business,[37] engineering,[38] government,[39] and health care.[40]

See also

- Economic history

- Economic system

References

- ^ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 9781315765747. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b «economy». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Dictionary.com Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, «economy.» The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. October 24, 2009.

- ^ Sheila C. Dow (2005), «Axioms and Babylonian thought: a reply», Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 27 (3), p. 385-391.

- ^ Charles F. Horne, Ph.D. (1915). «The Code of Hammurabi : Introduction». Yale University. Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Aragón, Fernando M.; Oteiza, Francisco; Rud, Juan Pablo (February 1, 2021). «Climate Change and Agriculture: Subsistence Farmers’ Response to Extreme Heat». American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 13 (1): 1–35. arXiv:1902.09204. doi:10.1257/pol.20190316. ISSN 1945-7731. S2CID 85529687. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Bronson, Bennet (November 1976), «Cash, Cannon, and Cowrie Shells: The Nonmodern Moneys of the World», Bulletin, vol. 47, Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, pp. 3–15.

- ^ G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World (Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 136–137, noting that economic historian Moses Finley maintained «serf» was an incorrect term to apply to the social structures of classical antiquity.

- ^ Quesnay, François. An Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World- preview entry:Physiocrats & physiocracy. Charles Scribner & Sons. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ «Industrial History of European Countries». European Route of Industrial Heritage. Council of Europe. Archived from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Jacob (February 28, 2014). «The Invention Of ‘The Economy’«. NPR — Planet Money. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ Taylor C. Boas, Jordan Gans-Morse (June 2009). «Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan». Studies in Comparative International Development. 44 (2): 137–61. doi:10.1007/s12116-009-9040-5.

- ^ Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-1138844001. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ «What Is Keynesian Economics? – Back to Basics – Finance & Development, September 2014». www.imf.org. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Koppstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark Irving (2005), Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, And Institutions In A Changing Global Order, Cambridge University Press, p. 156, ISBN 0-521-60395-1.

- ^ Gregory, Paul; Stuart, Robert (2004). Stuart, Robert C. (ed.). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century (7th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 538. ISBN 978-0618261819. OCLC 53446988.

Market Economy: Economy in which fundamentals of supply and demand provide signals regarding resource utilization.

- ^ Alec Nove (1987). «Planned Economy». The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. vol. 3. p. 879.

- ^ Kahle, Lynn R.; Gurel-Atay, Eda, eds. (2014). Communicating Sustainability for the Green Economy. New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3680-5.

- ^ «In the shadows». The Economist. June 17, 2004. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Kjeldsen-Kragh, Søren (2007). The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development: The Lessons of History. Copenhagen Business School Press DK. p. 73. ISBN 978-87-630-0194-6.

- ^ Potůček, Martin (1999). Not Only the Market: The Role of the Market, Government, and the Civic Sector. New York: Central European University Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-585-31675-9. OCLC 45729878.

- ^ «Gross Domestic Product | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)». www.bea.gov. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ The volume of financial transactions in the 2008 global economy was 73.5 times higher than nominal world GDP, while, in 1990, this ratio amounted to «only» 15.3 («A General Financial Transaction Tax: A Short Cut of the Pros, the Cons and a Proposal» Archived April 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Archived April 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Austrian Institute for Economic Research, 2009)

- ^ «Meanwhile, in the Real Economy» Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2009

- ^ «Bank Regulation Should Serve Real Economy» Archived March 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Archived March 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2011

- ^ «Perry and Romney Trade Swipes Over ‘Real Economy'» Archived July 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Archived July 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, August 15, 2011

- ^ «Real Economy» Archived February 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine definition in the Financial Times Lexicon

- ^ «Real economy» Archived November 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine definition in the Economic Glossary

- ^ • Deardorff’s Glossary of International Economics, search for real Archived January 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine.

• R. O’Donnell (1987). «real and nominal quantities,» The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 97-98. - ^ Varian, Hal R. (1987). «Microeconomics». The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1212-1. ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5.

- ^ Krugman, Paul; Wells, Robin (2012). Economics (3rd ed.). Worth Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 978-1464128738.

- ^ Backhouse, Roger (2002). The Penguin history of economics. London. ISBN 0-14-026042-0. OCLC 59475581. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

The boundaries of what constitutes economics are further blurred by the fact that economic issues are analysed not only by ‘economists’ but also by historians, geographers, ecologists, management scientists, and engineers.

- ^ Swedberg, Richard (2003). «The Classics in Economic Sociology» (PDF). Principles of Economic Sociology. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–31. ISBN 978-1400829378. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Blum, Matthias; Colvin, Christopher L. (2018), Blum, Matthias; Colvin, Christopher L. (eds.), «Introduction, or Why We Started This Project», An Economist’s Guide to Economic History, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–10, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96568-0_1, ISBN 978-3-319-96568-0

- ^ Chibnik, Michael (2011). Anthropology, Economics, and Choice (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73535-4. OCLC 773036705.

- ^ Clark, Gordon L.; Feldman, Maryann P.; Gertler, Meric S.; Williams, Kate (July 10, 2003). The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-925083-7. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Dielman, Terry E. (2001). Applied regression analysis for business and economics. Duxbury/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-534-37955-9. OCLC 44118027.

- ^ Dharmaraj, E. (2010). Engineering Economics. Mumbai: Himalaya Publishing House. ISBN 9789350432471. OCLC 1058341272.

- ^ King, David (2018). Fiscal Tiers: the economics of multi-level government. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-64813-5. OCLC 1020440881.

- ^ Tarricone, Rosanna (2006). «Cost-of-illness analysis». Health Policy. 77 (1): 51–63. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.016. PMID 16139925.

Further reading

- Friedman, Milton, Capitalism and Freedom, 1962.

- Rothbard, Murray, Man, Economy, and State: A Treatise on Economic Principles, 1962.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth, The Affluent Society, 1958.

- Mises, Ludwig von, Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, 1949.

- Keynes, John Maynard, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936.

- Marx, Karl, Das Kapital, 1867.

- Smith, Adam, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776.

Etymology. From economy, from Latin oeconomia, from Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomía, “management of a household, administration”), from οἶκος (oîkos, “house”) + νόμος (nómos, “management”).

Related Posts:

- What do we mean by efficiency?

— Efficiency signifies a peak level of performance… (Read More) - Why planned economy is bad?

— Production in command economies is notoriously inefficient… (Read More) - What are the advantages of a planned economy?

— AdvantagesPrices are kept under control and thus… (Read More) - What is an example of a planned economy?

— Examples of Centrally Planned Economies Communist and… (Read More) - What are the three types of economy?

— There are three main types of economies:… (Read More) - Why should you choose economics?

— More broadly, an economics degree helps prepare… (Read More) - What is the basic definition of economics?

— Economics is a social science concerned with… (Read More) - What is the modern definition of economics?

— According to Samuelson, ‘Economics is a social… (Read More) - Who gave the best definition of economics?

— Lionel Robbins (1932) developed implications of what… (Read More) - What is the Greek word of economics?

— The word ‘economics’ comes from two Greek… (Read More)

| Economics |

|

|

Economies by region |

| General categories |

|---|

|

Microeconomics · Macroeconomics History of economic thought Methodology · Mainstream & heterodox |

| Technical methods |

|

Mathematical economics Game theory · Optimization Computational · Econometrics Experimental · National accounting |

| Fields and subfields |

|

Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary |

| Lists |

|

Journals · Publications |

|

Economy: concept and history |

| Business and Economics Portal |

| This box: view · talk · edit |

An economy consists of the economic system of a country or other area; the labor, capital and land resources; and the manufacturing, trade, distribution, and consumption of goods and services of that area. An economy may also be described as a spatially limited and social network where goods and services are exchanged according to demand and supply between participants by barter or a medium of exchange with a credit or debit value accepted within the network.

A given economy is the end result of a process that involves its technological evolution, history and social organization, as well as its geography, natural resource endowment, and ecology, as main factors. These factors give context, content, and set the conditions and parameters in which an economy functions.

Contents

- 1 Range

- 2 Etymology

- 3 History

- 3.1 Ancient times

- 3.2 Middle ages

- 3.3 Early modern times

- 3.4 The industrial revolution

- 3.5 After World War II

- 4 Economic Phases of Precedence

- 5 Economic measures

- 5.1 GDP

- 6 Informal economy

- 7 Largest economies by GDP in 2011

- 8 Economies with the Largest Contribution to Global Economic Growth from 1996 to 2011

- 9 See also

- 10 Notes

- 11 References

- 12 Further reading

Range

Today the range of fields of study examining the economy revolve around the social science of economics, but may include sociology (economic sociology), history (economic history), anthropology (economic anthropology), and geography (economic geography). Practical fields directly related to the human activities involving production, distribution, exchange, and consumption of goods and services as a whole, range from engineering to management and business administration to applied science to finance.

All professions, occupations, economic agents or economic activities, contribute to the economy. Consumption, saving, and investment are core variable components in the economy and determine market equilibrium. There are three main sectors of economic activity: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Due to the growing importance of the financial sector in modern times[1], the term real economy is used by analysts[2][3]as well as politicians[4] to denote the part of the economy that is concerned with actually producing goods and services,[5] as ostensibly contrasted with the paper economy, or the financial side of the economy,[6] which is concerned with buying and selling on the financial markets. Alternate and long-standing terminology distinguishes measures of an economy expressed in real values (adjusted for inflation), such as real GDP, or in nominal values (unadjusted for inflation).[7]

Etymology

The English words «economy» and «economics» can be traced back to the Greek words οἰκονόμος, i.e. «one who manages a household», a composite word derived from οἴκος («house») and νέμω («manage; distribute»); οἰκονομία («household management»); and οἰκονομικός («of a household; of family»).

The first recorded sense of the word «œconomy» is in the phrase «the management of œconomic affairs», found in a work possibly composed in a monastery in 1440. «Economy» is later recorded in more general senses, including «thrift» and «administration».

The most frequently used current sense, denoting «the economic system of a country or an area», seems not to have developed until the 19th or 20th century.[8]

History

Ancient times

As long as someone has been making, supplying and distributing goods or services, there has been some sort of economy; economies grew larger as societies grew and became more complex. Sumer developed a large scale economy based on commodity money, while the Babylonians and their neighboring city states later developed the earliest system of economics as we think of, in terms of rules/laws on debt, legal contracts and law codes relating to business practices, and private property.[9]

The Babylonians and their city state neighbors developed forms of economics comparable to currently used civil society (law) concepts.[10] They developed the first known codified legal and administrative systems, complete with courts, jails, and government records.

Several centuries after the invention of cuneiform, the use of writing expanded beyond debt/payment certificates and inventory lists to be applied for the first time, about 2600 BC, to messages and mail delivery, history, legend, mathematics, astronomical records and other pursuits. Ways to divide private property, when it is contended… amounts of interest on debt… rules as to property and monetary compensation concerning property damage or physical damage to a person… fines for ‘wrong doing’… and compensation in money for various infractions of formalized law were standardized for the first time in history.[9]

Greek drachm of Aegina. Obverse: Land turtle / Reverse: ΑΙΓ(INA) and dolphin. The oldest turtle coin dates 700 BC

The ancient economy was mainly based on subsistence farming. The Shekel referred to an ancient unit of weight and currency. The first usage of the term came from Mesopotamia circa 3000 BC. and referred to a specific mass of barley which related other values in a metric such as silver, bronze, copper etc. A barley/shekel was originally both a unit of currency and a unit of weight… just as the British Pound was originally a unit denominating a one pound mass of silver.

For most people the exchange of goods occurred through social relationships. There were also traders who bartered in the marketplaces. In Ancient Greece, where the present English word ‘economy’ originated, many people were bond slaves of the freeholders. Economic discussion was driven by scarcity. Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) was the first to differentiate between a use value and an exchange value of goods. (Politics, Book I.) The exchange ratio he defined was not only the expression of the value of goods but of the relations between the people involved in trade. For most of the time in history economy therefore stood in opposition to institutions with fixed exchange ratios as reign, state, religion, culture, and tradition.[citation needed]

Middle ages

In Medieval times, what we now call economy was not far from the subsistence level. Most exchange occurred within social groups. On top of this, the great conquerors raised venture capital (from ventura, ital.; risk) to finance their captures. The capital should be refunded by the goods they would bring up in the New World. Merchants such as Jakob Fugger (1459–1525) and Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici (1360–1428) founded the first banks.[citation needed] The discoveries of Marco Polo (1254–1324),[dubious – discuss] Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) and Vasco da Gama (1469–1524) led to a first global economy. The first enterprises were trading establishments. In 1513 the first stock exchange was founded in Antwerpen. Economy at the time meant primarily trade.

Early modern times

The European captures became branches of the European states, the so-called colonies. The rising nation-states Spain, Portugal, France, Great Britain and the Netherlands tried to control the trade through custom duties and taxes in order to protect their national economy. The so-called mercantilism (from mercator, lat.: merchant) was a first approach to intermediate between private wealth and public interest. The secularization in Europe allowed states to use the immense property of the church for the development of towns. The influence of the nobles decreased. The first Secretaries of State for economy started their work. Bankers like Amschel Mayer Rothschild (1773–1855) started to finance national projects such as wars and infrastructure. Economy from then on meant national economy as a topic for the economic activities of the citizens of a state.

The industrial revolution

The first economist in the true meaning of the word was the Scotsman Adam Smith (1723–1790). He defined the elements of a national economy: products are offered at a natural price generated by the use of competition — supply and demand — and the division of labour. He maintained that the basic motive for free trade is human self interest. The so-called self interest hypothesis became the anthropological basis for economics. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) transferred the idea of supply and demand to the problem of overpopulation. The United States of America became the place where millions of expatriates from all European countries were searching for free economic evolvement.

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport had a profound effect on the socioeconomic and cultural conditions starting in the United Kingdom, then subsequently spreading throughout Europe, North America, and eventually the world. The onset of the Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in human history; almost every aspect of daily life was eventually influenced in some way. In Europe wild capitalism started to replace the system of mercantilism (today: protectionism) and led to economic growth. The period today is called industrial revolution because the system of Production, production and division of labour enabled the mass production of goods.

After World War II

After the chaos of two World Wars and the devastating Great Depression, policymakers searched for new ways of controlling the course of the economy. This was explored and discussed by Friedrich August von Hayek (1899–1992) and Milton Friedman (1912–2006) who pleaded for a global free trade and are supposed to be the fathers of the so called neoliberalism. However, the prevailing view was that held by John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who argued for a stronger control of the markets by the state. The theory that the state can alleviate economic problems and instigate economic growth through state manipulation of aggregate demand is called Keynesianism in his honor. In the late 1950s the economic growth in America and Europe—often called Wirtschaftswunder (ger: economic miracle) —brought up a new form of economy: mass consumption economy. In 1958 John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006) was the first to speak of an affluent society. In most of the countries the economic system is called a social market economy.

Economic Phases of Precedence

The economy may be considered as having developed through the following Phases or Degrees of Precedence.

- The ancient economy was mainly based on subsistence farming.

- The industrial revolution phase lessened the role of subsistence farming, converting it to more extensive and mono-cultural forms of agriculture in the last three centuries. The economic growth took place mostly in mining, construction and manufacturing industries. Commerce became more significant due to the need for improved exchange and distribution of produce throughout the community.

- In the economies of modern consumer societies phase there is a growing part played by services, finance, and technology—the (knowledge economy).

In modern economies, these phase precedences are somewhat differently expressed by four degrees of activity.[citation needed]

- Primary stage/degree of the economy: Involves the extraction and production of raw materials, such as corn, coal, wood and iron. (A coal miner and a fisherman would be workers in the primary degree.)

- Secondary stage/degree of the economy: Involves the transformation of raw or intermediate materials into goods e.g. manufacturing steel into cars, or textiles into clothing. (A builder and a dressmaker would be workers in the secondary degree.) At this stage the associated industrial economy is also sub-divided into several economic sectors (also called industries). Their separate evolution during the Industrial Revolution phase is dealt with elsewhere.

- Tertiary stage/degree of the economy: Involves the provision of services to consumers and businesses, such as baby-sitting, cinema and banking. (A shopkeeper and an accountant would be workers in the tertiary degree.)

- Quaternary stage/degree of the economy: Involves the research and development needed to produce products from natural resources and their subsequent by-products. (A logging company might research ways to use partially burnt wood to be processed so that the undamaged portions of it can be made into pulp for paper.) Note that education is sometimes included in this sector.

Other sectors of the developed community include :

- the Public Sector or state sector (which usually includes: parliament, law-courts and government centers, various emergency services, public health, shelters for empoverished and threatened people, transport facilities, air/sea ports, post-natal care, hospitals, schools, libraries, museums, preserved historical buildings, parks/gardens, nature-reserves, some universities, national sports grounds/stadiums, national arts/concert-halls or theaters and centers for various religions).

- the Private Sector or privately-run businesses.

- the Social sector or Voluntary sector.

Economic measures

There are a number of ways to measure economic activity of a nation. These methods of measuring economic activity include:

- Consumer spending

- Exchange Rate

- Gross domestic product

- GDP per capita

- GNP

- Stock Market

- Interest Rate

- National Debt

- Rate of Inflation

- Unemployment

- Balance of Trade

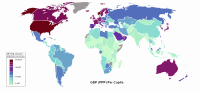

GDP

The GDP — Gross domestic product of a country is a measure of the size of its economy. The most conventional economic analysis of a country relies heavily on economic indicators like the GDP and GDP per capita. While often useful, it should be noted that GDP only includes economic activity for which money is exchanged.

Informal economy

An informal economy is economic activity that is neither taxed nor monitored by a government, contrasted with a formal economy. The informal economy is thus not included in that government’s Gross National Product (GNP). Although the informal economy is often associated with developing countries, all economic systems contain an informal economy in some proportion.

Informal economic activity is a dynamic process which includes many aspects of economic and social theory including exchange, regulation, and enforcement. By its nature, it is necessarily difficult to observe, study, define, and measure. No single source readily or authoritatively defines informal economy as a unit of study.

The terms «under the table» and «off the books» typically refer to this type of economy. The term black market refers to a specific subset of the informal economy. The term «informal sector» was used in many earlier studies, and has been mostly replaced in more recent studies which use the newer term.

Micro economics are focused on an individual person in a given economic society and Macro economics is looking at an economy as a whole. (town, city, region)

Largest economies by GDP in 2011

| List of 20 Largest Economies in Nominal GDP in 2011 by the International Monetary Fund[11][12] | List of 20 Largest Economies in GDP (PPP) in 2011 by the International Monetary Fund[13][14] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economies with the Largest Contribution to Global Economic Growth from 1996 to 2011

| List of 20 Largest Economies by Incremental Nominal GDP from 1996 to 2011 by the International Monetary Fund[15][16] | List of 20 Largest Economies by Incremental GDP (PPP) from 1996 to 2011 by the International Monetary Fund[13][17] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

| Business and economics portal |

- Capitalism

- Econometrics

- Economic history (includes list by country)

- Economic system

- Economic equilibrium

- History of money

- Non-market economics

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Supply and demand

- Thermoeconomics

- World Economy

Notes

- ^ The volume of financial transactions in the 2008 global economy was 73.5 times higher than nominal world GDP, while, in 1990, this ratio amounted to «only» 15.3 («A General Financial Transaction Tax: A Short Cut of the Pros, the Cons and a Proposal», Austrian Institute for Economic Research, 2009)

- ^ «Meanwhile, in the Real Economy», Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2009

- ^ «Bank Regulation Should Serve Real Economy», Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2011

- ^ «Perry and Romney Trade Swipes Over ‘Real Economy'», Wall Street Journal, August 15, 2011

- ^ «Real Economy» definition in the Financial Times Lexicon

- ^ «Real economy» definition in the Economic Glossary

- ^

• Deardorff’s Glossary of International Economics, search for real.

• R. O’Donnell (1987). «real and nominal quantities,» The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 97-98. - ^ Dictionary.com, «economy.» The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 24 Oct. 2009.

- ^ a b Sheila C. Dow (2005), «Axioms and Babylonian thought: a reply», Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 27 (3), p. 385-391.

- ^ Charles F. Horne, Ph.D. (1915). «The Code of Hammurabi : Introduction». Yale University. http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/medieval/hammint.htm. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ «International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, September 2011: Nominal GDP list of countries. Data for the year 2010». Imf.org. 1999-12-04. http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/index.php. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ^ «2010 Nominal GDP for the world and the European Union». Imf.org. 2006-09-14. http://http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=96&pr.y=13&sy=2010&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=001%2C998&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP&grp=1&a=1. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ^ a b «International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, September 2011: GDP (PPP) list of countries. Data for the year 2010». Imf.org. 1999-12-04. http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/index.php. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ^ «2010 GDP (PPP) for the world and the European Union». Imf.org. 2006-09-14. http://http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=96&pr.y=13&sy=2010&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=001%2C998&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP&grp=1&a=1. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ^ «International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, September 2011: Nominal GDP list of countries. Data for the year 2010». Imf.org. 2006-09-14. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=60&pr.y=4&sy=1996&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=512%2C941%2C914%2C446%2C612%2C666%2C614%2C668%2C311%2C672%2C213%2C946%2C911%2C137%2C193%2C962%2C122%2C674%2C912%2C676%2C313%2C548%2C419%2C556%2C513%2C678%2C316%2C181%2C913%2C682%2C124%2C684%2C339%2C273%2C638%2C921%2C514%2C948%2C218%2C943%2C963%2C686%2C616%2C688%2C223%2C518%2C516%2C728%2C918%2C558%2C748%2C138%2C618%2C196%2C522%2C278%2C622%2C692%2C156%2C694%2C624%2C142%2C626%2C449%2C628%2C564%2C228%2C283%2C924%2C853%2C233%2C288%2C632%2C293%2C636%2C566%2C634%2C964%2C238%2C182%2C662%2C453%2C960%2C968%2C423%2C922%2C935%2C714%2C128%2C862%2C611%2C716%2C321%2C456%2C243%2C722%2C248%2C942%2C469%2C718%2C253%2C724%2C642%2C576%2C643%2C936%2C939%2C961%2C644%2C813%2C819%2C199%2C172%2C184%2C132%2C524%2C646%2C361%2C648%2C362%2C915%2C364%2C134%2C732%2C652%2C366%2C174%2C734%2C328%2C144%2C258%2C146%2C656%2C463%2C654%2C528%2C336%2C923%2C263%2C738%2C268%2C578%2C532%2C537%2C944%2C742%2C176%2C866%2C534%2C369%2C536%2C744%2C429%2C186%2C433%2C925%2C178%2C869%2C436%2C746%2C136%2C926%2C343%2C466%2C158%2C112%2C439%2C111%2C916%2C298%2C664%2C927%2C826%2C846%2C542%2C299%2C967%2C582%2C443%2C474%2C917%2C754%2C544%2C698&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP&grp=0&a=. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ^ «Nominal GDP for the world and the European Union». Imf.org. 2006-09-14. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=60&pr.y=4&sy=1996&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=512%2C941%2C914%2C446%2C612%2C666%2C614%2C668%2C311%2C672%2C213%2C946%2C911%2C137%2C193%2C962%2C122%2C674%2C912%2C676%2C313%2C548%2C419%2C556%2C513%2C678%2C316%2C181%2C913%2C682%2C124%2C684%2C339%2C273%2C638%2C921%2C514%2C948%2C218%2C943%2C963%2C686%2C616%2C688%2C223%2C518%2C516%2C728%2C918%2C558%2C748%2C138%2C618%2C196%2C522%2C278%2C622%2C692%2C156%2C694%2C624%2C142%2C626%2C449%2C628%2C564%2C228%2C283%2C924%2C853%2C233%2C288%2C632%2C293%2C636%2C566%2C634%2C964%2C238%2C182%2C662%2C453%2C960%2C968%2C423%2C922%2C935%2C714%2C128%2C862%2C611%2C716%2C321%2C456%2C243%2C722%2C248%2C942%2C469%2C718%2C253%2C724%2C642%2C576%2C643%2C936%2C939%2C961%2C644%2C813%2C819%2C199%2C172%2C184%2C132%2C524%2C646%2C361%2C648%2C362%2C915%2C364%2C134%2C732%2C652%2C366%2C174%2C734%2C328%2C144%2C258%2C146%2C656%2C463%2C654%2C528%2C336%2C923%2C263%2C738%2C268%2C578%2C532%2C537%2C944%2C742%2C176%2C866%2C534%2C369%2C536%2C744%2C429%2C186%2C433%2C925%2C178%2C869%2C436%2C746%2C136%2C926%2C343%2C466%2C158%2C112%2C439%2C111%2C916%2C298%2C664%2C927%2C826%2C846%2C542%2C299%2C967%2C582%2C443%2C474%2C917%2C754%2C544%2C698&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP&grp=0&a=. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ^ «GDP (PPP) for the world and the European Union». Imf.org. 2006-09-14. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=44&pr.y=9&sy=1996&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=001%2C998&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP&grp=1&a=1. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

References

- Aristotle, Politics, Book I-IIX, translated by Benjamin Jowett, Classics.mit.edu

- Barnes, Peter, Capitalism 3.0, A Guide to Reclaiming the Commons, San Francisco 2006, Whatiseconomy.com

- Dill, Alexander, Reclaiming the Hidden Assets, Towards a Global Freeware Index, Global Freeware Research Paper 01-07, 2007, Whatiseconomy.com

- Fehr Ernst, Schmidt, Klaus M., The Economics Of Fairness, Reciprocity and Altruism — experimental Evidence and new Theories, 2005, Discussion PAPER 2005-20, Munich Economics, Whatiseconomy.com

- Marx, Karl, Engels, Friedrich, 1848, The Communist Manifesto, Marxists.org

- Stiglitz, Joseph E., Global public goods and global finance: does global governance ensure that the global public interest is served? In: Advancing Public Goods, Jean-Philippe Touffut, (ed.), Paris 2006, pp. 149/164, GSB.columbia.edu

- Where is the Wealth of Nations? Measuring Capital for the 21st Century. Wealth of Nations Report 2006, Ian Johnson and Francois Bourguignon, World Bank, Washington 2006, Whatiseconomy.com

Further reading

- Friedman, Milton, Capitalism and Freedom, 1962.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth, The Affluent Society, 1958.

- Keynes, John Maynard, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936.

- Smith, Adam, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776.