An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) representing phonemes, units of sounds that distinguish words, of certain spoken languages.[1] Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syllable, and logographic systems use characters to represent words, morphemes, or other semantic units.[2][3]

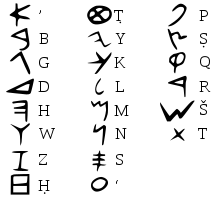

The Egyptians are believed to have created the first alphabet in a technical sense. The short uniliteral signs are used to write pronunciation guides for logograms, or a character that represents a word, or morpheme, and later on, being used to write foreign words.[4] This was used up to the 5th century AD.[5] The first fully phonemic script, the Proto-Sinaitic script, which developed into the Phoenician alphabet, is considered to be the first alphabet and is the ancestor of most modern alphabets, abjads, and abugidas, including Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and possibly Brahmic.[6][7] It was created by Semitic-speaking workers and slaves in the Sinai Peninsula in modern-day Egypt, by selecting a small number of hieroglyphs commonly seen in their Egyptian surroundings to describe the sounds, as opposed to the semantic values of the Canaanite languages.[8][9]

Peter T. Daniels distinguishes an abugida, a set of graphemes that represent consonantal base letters that diacritics modify to represent vowels, like in Devanagari and other South Asian scripts, an abjad, in which letters predominantly or exclusively represent consonants such as the original Phoenician, Hebrew or Arabic, and an alphabet, a set of graphemes that represent both consonants and vowels. In this narrow sense of the word, the first true alphabet was the Greek alphabet,[10][11] which was based on the earlier Phoenician abjad.

Alphabets are usually associated with a standard ordering of letters. This makes them useful for purposes of collation, which allows words to be sorted in a specific order, commonly known as the alphabetical order. It also means that their letters can be used as an alternative method of «numbering» ordered items, in such contexts as numbered lists and number placements. There are also names for letters in some languages. This is known as acrophony; It is present in some modern scripts, such as Greek, and many Semitic scripts, such as Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac. It was used in some ancient alphabets, such as in Phoenician. However, this system is not present in all languages, such as the Latin alphabet, which adds a vowel after a character for each letter. Some systems also used to have this system but later on abandoned it for a system similar to Latin, such as Cyrillic.

Etymology

The English word alphabet came into Middle English from the Late Latin word alphabetum, which in turn originated in the Greek, ἀλφάβητος (alphábētos); it was made from the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha (α) and beta (β).[12] The names for the Greek letters, in turn, came from the first two letters of the Phoenician alphabet: aleph, the word for ox, and bet, the word for house.[13]

History

Ancient Near Eastern alphabets

The Ancient Egyptian writing system had a set of some 24 hieroglyphs that are called uniliterals,[14] which are glyphs that provide one sound.[15] These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names.[4] The script was used a fair amount in the 4th century CE.[16] However, after pagan temples were closed down, it was forgotten in the 5th century until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone.[5] There was also the Cuneiform script. The script was used to write several ancient languages. However, it was primarily used to write Sumerian.[17] The last known use of the Cuneiform script was in 75 CE, after which the script fell out of use.[18]

In the Middle Bronze Age, an apparently «alphabetic» system known as the Proto-Sinaitic script appeared in Egyptian turquoise mines in the Sinai peninsula dated c. 15th century BCE, apparently left by Canaanite workers. In 1999, John and Deborah Darnell, American Egyptologists, discovered an earlier version of this first alphabet at the Wadi el-Hol valley in Egypt. The script dated to c. 1800 BCE and shows evidence of having been adapted from specific forms of Egyptian hieroglyphs that could be dated to c. 2000 BCE, strongly suggesting that the first alphabet had developed about that time.[19] The script was based on letter appearances and names, believed to be based on Egyptian hieroglyphs.[6] This script had no characters representing vowels. Originally, it probably was a syllabary—a script where syllables are represented with characters—with symbols that were not needed being removed. The best-attested Bronze Age alphabet is Ugaritic, invented in Ugarit (Syria) before the 15th century BCE. This was an alphabetic cuneiform script with 30 signs, including three that indicate the following vowel. This script was not used after the destruction of Ugarit in 1178 BCE.[20]

The Proto-Sinaitic script eventually developed into the Phoenician alphabet, conventionally called «Proto-Canaanite» before c. 1050 BCE.[7] The oldest text in Phoenician script is an inscription on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram c. 1000 BCE. This script is the parent script of all western alphabets. By the tenth century BCE, two other forms distinguish themselves, Canaanite and Aramaic. The Aramaic gave rise to the Hebrew script.[21]

The South Arabian alphabet, a sister script to the Phoenician alphabet, is the script from which the Ge’ez alphabet, an abugida, a writing system where consonant-vowel sequences are written as units, which was used around the horn of Africa, descended. Vowel-less alphabets are called abjads, currently exemplified in others such as Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac. The omission of vowels was not always a satisfactory solution due to the need of preserving sacred texts. «Weak» consonants are used to indicate vowels. These letters have a dual function since they can also be used as pure consonants.[22][23]

The Proto-Sinaitic script and the Ugaritic script were the first scripts with a limited number of signs instead of using many different signs for words, in contrast to the other widely used writing systems at the time, Cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Linear B. The Phoenician script was probably the first phonemic script,[6][7] and it contained only about two dozen distinct letters, making it a script simple enough for traders to learn. Another advantage of the Phoenician alphabet was that it could write different languages since it recorded words phonemically.[24]

The Phoenician script was spread across the Mediterranean by the Phoenicians.[7] The Greek Alphabet was the first alphabet in which vowels have independent letter forms separate from those of consonants. The Greeks chose letters representing sounds that did not exist in Phoenician to represent vowels. The syllabical Linear B, a script that was used by the Mycenaean Greeks from the 16th century BCE, had 87 symbols, including five vowels. In its early years, there were many variants of the Greek alphabet, causing many different alphabets to evolve from it.[25]

European alphabets

The Greek alphabet, in Euboean form, was carried over by Greek colonists to the Italian peninsula circa 800-600 BCE giving rise to many different alphabets used to write the Italic languages, like the Etruscan alphabet.[26] One of these became the Latin alphabet, which spread across Europe as the Romans expanded their republic. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the alphabet survived in intellectual and religious works. It came to be used for the descendant languages of Latin (the Romance languages) and most of the other languages of western and central Europe. Today, it is the most widely used script in the world.[27]

The Etruscan alphabet remained nearly unchanged for several hundred years. Only evolving once the Etruscan language changed itself. The letters used for non-existent phonemes were dropped.[28] Afterwards, however, the alphabet went through many different changes. The final classical form of Etruscan contained 20 letters. Four of them are vowels (a, e, i, and u). Six fewer letters than the earlier forms. The script in its classical form was used until the 1st century CE. The Etruscan language itself was not used in imperial Rome, but the script was used for religious texts.[29]

Some adaptations of the Latin alphabet have ligatures, a combination of two letters make one, such as æ in Danish and Icelandic and Ȣ in Algonquian; borrowings from other alphabets, such as the thorn þ in Old English and Icelandic, which came from the Futhark runes;[30] and modified existing letters, such as the eth ð of Old English and Icelandic, which is a modified d. Other alphabets only use a subset of the Latin alphabet, such as Hawaiian and Italian, which uses the letters j, k, x, y, and w only in foreign words.[31]

Another notable script is Elder Futhark, believed to have evolved out of one of the Old Italic alphabets. Elder Futhark gave rise to other alphabets known collectively as the Runic alphabets. The Runic alphabets were used for Germanic languages from 100 CE to the late Middle Ages, being engraved on stone and jewelry, although inscriptions found on bone and wood occasionally appear. These alphabets have since been replaced with the Latin alphabet. The exception was for decorative use, where the runes remained in use until the 20th century.[32]

The Old Hungarian script was the writing system of the Hungarians. It was in use during the entire history of Hungary, albeit not as an official writing system. From the 19th century, it once again became more and more popular.[33]

The Glagolitic alphabet was the initial script of the liturgical language Old Church Slavonic and became, together with the Greek uncial script, the basis of the Cyrillic script. Cyrillic is one of the most widely used modern alphabetic scripts and is notable for its use in Slavic languages and also for other languages within the former Soviet Union. Cyrillic alphabets include Serbian, Macedonian, Bulgarian, Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian. The Glagolitic alphabet is believed to have been created by Saints Cyril and Methodius, while the Cyrillic alphabet was created by Clement of Ohrid, their disciple. They feature many letters that appear to have been borrowed from or influenced by Greek and Hebrew.[34]

Asian alphabets

Beyond the logographic Chinese writing, many phonetic scripts exist in Asia. The Arabic alphabet, Hebrew alphabet, Syriac alphabet, and other abjads of the Middle East are developments of the Aramaic alphabet.[35][36]

Most alphabetic scripts of India and Eastern Asia descend from the Brahmi script, believed to be a descendant of Aramaic.[37]

Hangul

In Korea, Sejong the Great created the Hangul alphabet in 1443 CE.[38] Hangul is a unique alphabet: it is a featural alphabet, where the design of many of the letters comes from a sound’s place of articulation, like P looking like the widened mouth and L looking like the tongue pulled in.[39] The creation of Hangul was planned by the government of the day,[40] and it places individual letters in syllable clusters with equal dimensions, in the same way as Chinese characters. This change allows for mixed-script writing, where one syllable always takes up one type space no matter how many letters get stacked into building that one sound-block.[41]

Zhuyin

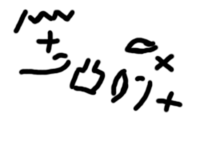

Zhuyin, sometimes referred to as Bopomofo, is a semi-syllabary. It transcribes Mandarin phonetically in the Republic of China. After the later establishment of the People’s Republic of China and its adoption of Hanyu Pinyin, the use of Zhuyin today is limited. However, it is still widely used in Taiwan. Zhuyin developed from a form of Chinese shorthand based on Chinese characters in the early 1900s and has elements of both an alphabet and a syllabary. Like an alphabet, the phonemes of syllable initials are represented by individual symbols, but like a syllabary, the phonemes of the syllable finals are not; each possible final (excluding the medial glide) has its own character, an example being luan written as ㄌㄨㄢ (l-u-an). The last symbol ㄢ takes place as the entire final -an. While Zhuyin is not a mainstream writing system, it is still often used in ways similar to a romanization system, for aiding pronunciation and as an input method for Chinese characters on computers and cellphones.[42]

Romanization

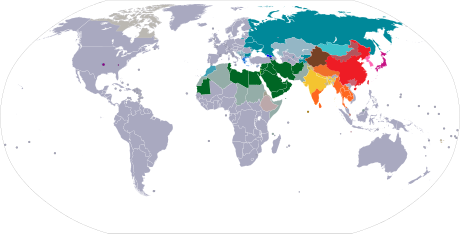

European alphabets, especially Latin and Cyrillic, have been adapted for many languages of Asia. Arabic is also widely used, sometimes as an abjad, as with Urdu and Persian, and sometimes as a complete alphabet, as with Kurdish and Uyghur.[43][44]

Types

The term «alphabet» is used by linguists and paleographers in both a wide and a narrow sense. In a broader sense, an alphabet is a segmental script at the phoneme level—that is, it has separate glyphs for individual sounds and not for larger units such as syllables or words. In the narrower sense, some scholars distinguish «true» alphabets from two other types of segmental script, abjads, and abugidas. These three differ in how they treat vowels. Abjads have letters for consonants and leave most vowels unexpressed. Abugidas are also consonant-based but indicate vowels with diacritics, a systematic graphic modification of the consonants.[45] The earliest known alphabet using this sense is the Wadi el-Hol script, believed to be an abjad. Its successor, Phoenician, is the ancestor of modern alphabets, including Arabic, Greek, Latin (via the Old Italic alphabet), Cyrillic (via the Greek alphabet), and Hebrew (via Aramaic).[46][47]

Examples of present-day abjads are the Arabic and Hebrew scripts;[48] true alphabets include Latin, Cyrillic, and Korean Hangul; and abugidas, used to write Tigrinya, Amharic, Hindi, and Thai. The Canadian Aboriginal syllabics are also an abugida, rather than a syllabary, as their name would imply, because each glyph stands for a consonant and is modified by rotation to represent the following vowel. In a true syllabary, each consonant-vowel combination gets represented by a separate glyph.[49]

All three types may be augmented with syllabic glyphs. Ugaritic, for example, is essentially an abjad but has syllabic letters for /ʔa, ʔi, ʔu/[50][51] These are the only times that vowels are indicated. Coptic has a letter for /ti/.[52] Devanagari is typically an abugida augmented with dedicated letters for initial vowels, though some traditions use अ as a zero consonant as the graphic base for such vowels.[53][54]

The boundaries between the three types of segmental scripts are not always clear-cut. For example, Sorani Kurdish is written in the Arabic script, which, when used for other languages, is an abjad.[55] In Kurdish, writing the vowels is mandatory, and whole letters are used, so the script is a true alphabet. Other languages may use a Semitic abjad with forced vowel diacritics, effectively making them abugidas. On the other hand, the Phagspa script of the Mongol Empire was based closely on the Tibetan abugida, but vowel marks are written after the preceding consonant rather than as diacritic marks. Although short a is not written, as in the Indic abugidas, The source of the term «abugida,» namely the Ge’ez abugida now used for Amharic and Tigrinya, has assimilated into their consonant modifications. It is no longer systematic and must be learned as a syllabary rather than as a segmental script. Even more extreme, the Pahlavi abjad eventually became logographic.[56]

Thus the primary categorisation of alphabets reflects how they treat vowels. For tonal languages, further classification can be based on their treatment of tone. Though names do not yet exist to distinguish the various types. Some alphabets disregard tone entirely, especially when it does not carry a heavy functional load,[57] as in Somali and many other languages of Africa and the Americas.[58] Most commonly, tones are indicated by diacritics, which is how vowels are treated in abugidas, which is the case for Vietnamese (a true alphabet) and Thai (an abugida). In Thai, the tone is determined primarily by a consonant, with diacritics for disambiguation.[59] In the Pollard script, an abugida, vowels are indicated by diacritics. The placing of the diacritic relative to the consonant is modified to indicate the tone.[44] More rarely, a script may have separate letters for tones, as is the case for Hmong and Zhuang.[60] For many, regardless of whether letters or diacritics get used, the most common tone is not marked, just as the most common vowel is not marked in Indic abugidas. In Zhuyin, not only is one of the tones unmarked; but there is a diacritic to indicate a lack of tone, like the virama of Indic.[61]

Alphabetical order

Alphabets often come to be associated with a standard ordering of their letters; this is for collation—namely, for listing words and other items in alphabetical order.[62]

Latin alphabets

The basic ordering of the Latin alphabet (A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z), which derives from the Northwest Semitic «Abgad» order,[63] is already well established. Although, languages using this alphabet have different conventions for their treatment of modified letters (such as the French é, à, and ô) and certain combinations of letters (multigraphs). In French, these are not considered to be additional letters for collation. However, in Icelandic, the accented letters such as á, í, and ö are considered distinct letters representing different vowel sounds from sounds represented by their unaccented counterparts. In Spanish, ñ is considered a separate letter, but accented vowels such as á and é are not. The ll and ch were also formerly considered single letters and sorted separately after l and c, but in 1994, the tenth congress of the Association of Spanish Language Academies changed the collating order so that ll came to be sorted between lk and lm in the dictionary and ch came to be sorted between cg and ci; those digraphs were still formally designated as letters, but in 2010 the Real Academia Española changed it, so they are no longer considered letters at all.[64][65]

In German, words starting with sch- (which spells the German phoneme /ʃ/) are inserted between words with initial sca- and sci- (all incidentally loanwords) instead of appearing after the initial sz, as though it were a single letter, which contrasts several languages such as Albanian, in which dh-, ë-, gj-, ll-, rr-, th-, xh-, and zh-, which all represent phonemes and considered separate single letters, would follow the letters d, e, g, l, n, r, t, x, and z, respectively, as well as Hungarian and Welsh. Further, German words with an umlaut get collated ignoring the umlaut as—contrary to Turkish, which adopted the graphemes ö and ü, and where a word like tüfek would come after tuz, in the dictionary. An exception is the German telephone directory, where umlauts are sorted like ä=ae since names such as Jäger also appear with the spelling Jaeger and are not distinguished in the spoken language.[66]

The Danish and Norwegian alphabets end with æ—ø—å,[67][68] whereas the Swedish conventionally put å—ä—ö at the end. However, æ phonetically corresponds with ä, as does ø and ö.[69]

Early alphabets

It is unknown whether the earliest alphabets had a defined sequence. Some alphabets today, such as the Hanuno’o script, are learned one letter at a time, in no particular order, and are not used for collation where a definite order is required.[70] However, a dozen Ugaritic tablets from the fourteenth century BCE preserve the alphabet in two sequences. One, the ABCDE order later used in Phoenician, has continued with minor changes in Hebrew, Greek, Armenian, Gothic, Cyrillic, and Latin; the other, HMĦLQ, was used in southern Arabia and is preserved today in Ethiopic.[71] Both orders have therefore been stable for at least 3000 years.[72]

Runic used an unrelated Futhark sequence, which got simplified later on.[73] Arabic uses usually uses its sequence, although Arabic retains the traditional abjadi order, which is used for numbers.[74]

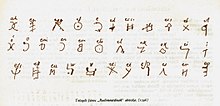

The Brahmic family of alphabets used in India uses a unique order based on phonology: The letters are arranged according to how and where the sounds get produced in the mouth. This organization is present in Southeast Asia, Tibet, Korean hangul, and even Japanese kana, which is not an alphabet.[75]

Acrophony

In Phoenician, each letter got associated with a word that begins with that sound. This is called acrophony and is continuously used to varying degrees in Samaritan, Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic.[76][77][78][79]

Acrophony got abandoned in Latin. It referred to the letters by adding a vowel (usually «e,» sometimes «a,» or «u») before or after the consonant. Two exceptions were Y and Z, which were borrowed from the Greek alphabet rather than Etruscan. They were known as Y Graeca «Greek Y» and zeta (from Greek)—this discrepancy was inherited by many European languages, as in the term zed for Z in all forms of English, other than American English.[80] Over time names sometimes shifted or were added, as in double U for W, or «double V» in French, the English name for Y, and the American zee for Z. Comparing them in English and French gives a clear reflection of the Great Vowel Shift: A, B, C, and D are pronounced /eɪ, biː, siː, diː/ in today’s English, but in contemporary French they are /a, be, se, de/.[81] The French names (from which the English names got derived) preserve the qualities of the English vowels before the Great Vowel Shift. By contrast, the names of F, L, M, N, and S (/ɛf, ɛl, ɛm, ɛn, ɛs/) remain the same in both languages because «short» vowels were largely unaffected by the Shift.[82]

In Cyrillic, originally, acrophony was present using Slavic words. The first three words going, azŭ, buky, vědě, with the Cyrillic collation order being, А, Б, В. However, this was later abandoned in favor of a system similar to Latin.[83]

Orthography and pronunciation

When an alphabet is adopted or developed to represent a given language, an orthography generally comes into being, providing rules for spelling words, following the principle on which alphabets get based. These rules will map letters of the alphabet to the phonemes of the spoken language.[84] In a perfectly phonemic orthography, there would be a consistent one-to-one correspondence between the letters and the phonemes so that a writer could predict the spelling of a word given its pronunciation, and a speaker would always know the pronunciation of a word given its spelling, and vice versa. However, this ideal is usually never achieved in practice. Languages can come close to it, such as Spanish and Finnish. others, such as English, deviate from it to a much larger degree.[85]

The pronunciation of a language often evolves independently of its writing system. Writing systems have been borrowed for languages the orthography was not initially made to use. The degree to which letters of an alphabet correspond to phonemes of a language varies.[86]

Languages may fail to achieve a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds in any of several ways:

- A language may represent a given phoneme by combinations of letters rather than just a single letter. Two-letter combinations are called digraphs, and three-letter groups are called trigraphs. German uses the tetragraphs (four letters) «tsch» for the phoneme German pronunciation: [tʃ] and (in a few borrowed words) «dsch» for [dʒ].[87] Kabardian also uses a tetragraph for one of its phonemes, namely «кхъу.»[88] Two letters representing one sound occur in several instances in Hungarian as well (where, for instance, cs stands for [tʃ], sz for [s], zs for [ʒ], dzs for [dʒ]).[89]

- A language may represent the same phoneme with two or more different letters or combinations of letters. An example is modern Greek which may write the phoneme Greek pronunciation: [i] in six different ways: ⟨ι⟩, ⟨η⟩, ⟨υ⟩, ⟨ει⟩, ⟨οι⟩, and ⟨υι⟩.[90]

- A language may spell some words with unpronounced letters that exist for historical or other reasons. For example, the spelling of the Thai word for «beer» [เบียร์] retains a letter for the final consonant «r» present in the English word it borrows, but silences it.[91]

- Pronunciation of individual words may change according to the presence of surrounding words in a sentence, for example, in Sandhi.[92]

- Different dialects of a language may use different phonemes for the same word.[93]

- A language may use different sets of symbols or rules for distinct vocabulary items, typically for foreign words, such as in the Japanese katakana syllabary is used for foreign words, and there are rules in English for using loanwords from other languages.[94][95]

National languages sometimes elect to address the problem of dialects by associating the alphabet with the national standard. Some national languages like Finnish, Armenian, Turkish, Russian, Serbo-Croatian (Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian), and Bulgarian have a very regular spelling system with nearly one-to-one correspondence between letters and phonemes.[96] Similarly, the Italian verb corresponding to ‘spell (out),’ compitare, is unknown to many Italians because spelling is usually trivial, as Italian spelling is highly phonemic.[97] In standard Spanish, one can tell the pronunciation of a word from its spelling, but not vice versa, as phonemes sometimes can be represented in more than one way, but a given letter is consistently pronounced.[98] French using silent letters, nasal vowels, and elision, may seem to lack much correspondence between the spelling and pronunciation. However, its rules on pronunciation, though complex, are consistent and predictable with a fair degree of accuracy.[99]

At the other extreme are languages such as English, where pronunciations mostly have to be memorized as they do not correspond to the spelling consistently. For English, this is because the Great Vowel Shift occurred after the orthography got established and because English has acquired a large number of loanwords at different times, retaining their original spelling at varying levels.[100] However, even English has general, albeit complex, rules that predict pronunciation from spelling. Rules like this are usually successful. However, rules to predict spelling from pronunciation have a higher failure rate.[101]

Sometimes, countries have the written language undergo a spelling reform to realign the writing with the contemporary spoken language. These can range from simple spelling changes and word forms to switching the entire writing system. For example, Turkey switched from the Arabic alphabet to a Latin-based Turkish alphabet,[102] and when Kazakh changed from an Arabic script to a Cyrillic script due to the Soviet Union’s influence, and in 2021, it made a transition to the Latin alphabet, similar to Turkish.[103][104] The Cyrillic script used to be official in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan before they all switched to the Latin alphabet, including Uzbekistan that is having a reform of the alphabet to use diacritics on the letters that are marked by apostrophes and the letters that are digraphs.[105][106]

The standard system of symbols used by linguists to represent sounds in any language, independently of orthography, is called the International Phonetic Alphabet.[107]

See also

- Abecedarium

- Acrophony

- Akshara

- Alphabet book

- Alphabet effect

- Alphabet song

- Alphabetical order

- Butterfly Alphabet

- Character encoding

- Constructed script

- Fingerspelling

- NATO phonetic alphabet

- Lipogram

- List of writing systems

- Pangram

- Thoth

- Transliteration

- Unicode

References

- ^ Pulgram, Ernst (1951). «Phoneme and Grapheme: A Parallel». WORD. 7 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1080/00437956.1951.11659389. ISSN 0043-7956.

- ^ Daniels & Bright 1996, p. 4

- ^ Taylor, Insup (1980), Kolers, Paul A.; Wrolstad, Merald E.; Bouma, Herman (eds.), «The Korean writing system: An alphabet? A syllabary? a logography?», Processing of Visible Language, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 67–82, doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-1068-6_5, ISBN 978-1-4684-1070-9, retrieved 19 June 2021

- ^ a b Daniels & Bright 1996, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b Houston, Stephen; Baines, John; Cooper, Jerrold (July 2003). «Last Writing: Script Obsolescence in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Mesoamerica». Comparative Studies in Society and History. 45 (3). doi:10.1017/S0010417503000227. ISSN 0010-4175. S2CID 145542213.

- ^ a b c Coulmas 1989, pp. 140–141

- ^ a b c d Daniels & Bright 1996, pp. 92–96

- ^ Goldwasser, O. (2012). «The Miners that Invented the Alphabet — a Response to Christopher Rollston». Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 4 (3): 9–22. doi:10.2458/azu_jaei_v04i3_goldwasser.

- ^ Goldwasser, O. (2010). «How the Alphabet was Born from Hieroglyphs». Biblical Archaeology Review. 36 (2): 40–53.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (1996). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-21481-6.

- ^ Millard 1986, p. 396

- ^ «alphabet». Merriam-Webster.com.

- ^ «Alphabet | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Lynn, Bernadette (8 April 2004). «The Development of the Western Alphabet». h2g2. BBC. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ «Uniliteral Signs». www.bibalex.org. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Allen, James P. (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (Revised 2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139486354.

- ^ Bram, Jagersma (2010). A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian. Universiteit Leiden. p. 15.

- ^ Westenholz, Aage (19 January 2007). «The Graeco-Babyloniaca Once Again». Zeitschrift für Assyrologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. 97 (2). doi:10.1515/ZA.2007.014. ISSN 0084-5299. S2CID 161908528.

- ^ Darnell, J. C.; Dobbs-Allsopp, F. W.; Lundberg, Marilyn J.; McCarter, P. Kyle; Zuckerman, Bruce; Manassa, Colleen (2005). «Two Early Alphabetic Inscriptions from the Wadi el-Ḥôl: New Evidence for the Origin of the Alphabet from the Western Desert of Egypt». The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 59: 63, 65, 67–71, 73–113, 115–124. JSTOR 3768583.

- ^ Ugaritic Writing online

- ^ Coulmas 1989, p. 142

- ^ Coulmas 1989, p. 147

- ^ «Matres lectionis | orthography | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Hock, Hans; Joseph, Brian (22 July 2019). Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics (3rd ed.). Mouton De Gruyter. p. 85. ISBN 978-3110609691.

- ^ Ventris, Micheal; Chadwick, John (2015). Documents in Mycenaean Greek: Three Hundred Selected Tablets from Knossos, Pylos and Mycenae with Commentary and Vocabulary (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1107503410.

- ^ Etruscology. Alessandro Naso. Boston. 2017. ISBN 978-1-934078-49-5. OCLC 1012851705.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Jeffery, L. H.; Johnston, A. W. (10 May 1990). The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece: A Study of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and Its Development from the Eighth to the Fifth Centuries B.C. (Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology) (Revised ed.). Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198140610.

- ^ Bonfante, Giuliano (2002). The Etruscan language : an introduction. Larissa Bonfante (2nd ed.). Manchester [England]: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5539-3. OCLC 50072597.

- ^ «Etruscan alphabet | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Britannica. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Knight, Sirona (2008). Runes. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-6006-8. OCLC 213301655.

- ^ Robustelli, Cecilia; Maiden, Martin (4 February 2014). A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian. Routledge Reference Grammars (2nd ed.). Routledge (published 25 May 2007). ISBN 978-0340913390.

- ^ Stifter, David (2010), «Lepontische Studien: Lexicon Leponticum und die Funktion von san im Lepontischen», in Stüber, Karin; et al. (eds.), Akten des 5. Deutschsprachigen Keltologensymposiums. Zürich, 7.–10. September 2009, Wien.

- ^ Maxwell, Alexander (2004). «Contemporary Hungarian Rune-Writing Ideological Linguistic Nationalism within a Homogenous Nation» (PDF). Anthropos.

- ^ «Glagolitic alphabet | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ «Aramaic Alphabet | PDF | Languages Of Asia | Writing». Scribd. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Blau, Joshua (2010). Phonology and morphology of Biblical Hebrew : an introduction. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-601-1. OCLC 759160098.

- ^ «Brāhmī | writing system | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ «上親制諺文二十八字…是謂訓民正音 (His majesty created 28 characters himself… It is Hunminjeongeum (original name for Hangul))», 《세종실록 (The Annals of the Choson Dynasty : Sejong)》 25년 12월.

- ^ Hitkari, Cherry (6 October 2021). «Alphabet’s Epitome: The Invention of Hangul and its Contribution to the Korean Society». Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ «Hangul | Alphabet Chart & Pronunciation | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Paul A. Kolers; Merald Ernest Wrolstad; Herman Bouma (1980). Processing of visible language 2. New York. ISBN 0-306-40576-8. OCLC 7099393.

- ^ «The Definition of the Bopomofo Chinese Phonetic System». ThoughtCo. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Thackston, W.M. (2006), «—Sorani Kurdish— A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings», Harvard Faculty of Arts & Sciences, Harvard University, retrieved 10 June 2021

- ^ a b Zhou, Minglang (24 October 2012). Multilingualism in China: The Politics of Writing Reforms for Minority Languages. Mouton de Gruyter.

- ^ For critics of the abjad-abugida-alphabet distinction, see Reinhard G. Lehmann: «27-30-22-26. How Many Letters Needs an Alphabet? The Case of Semitic», in: The idea of writing: Writing across borders; edited by Alex de Voogt and Joachim Friedrich Quack, Leiden: Brill 2012, p. 11-52, esp p. 22-27

- ^ «Sinaitic inscriptions | Alphabet, Meaning, & Decipherment | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Thamis. «The Phoenician Alphabet & Language». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Lipiński, Edward (1975). Studies in Aramaic inscriptions and onomastics. [Leuven]: Leuven University Press. ISBN 90-6186-019-9. OCLC 2005521.

- ^ Bernard Comrie, 2005, «Writing Systems», in Haspelmath et al. eds, The World Atlas of Language Structures (p 568 ff). Also Robert Bringhurst, 2004, The solid form of language: an essay on writing and meaning.

- ^ Florian Coulmas, 1991, The writing systems of the world

- ^ Schniedewind, William M. (2007). A primer on Ugaritic : language, culture, and literature. Joel H. Hunt. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-34933-1. OCLC 647687091.

- ^ «КОПТСКОЕ ПИСЬМО • Большая российская энциклопедия — электронная версия». bigenc.ru. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Dhanesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9. OCLC 648298147.

- ^ «A Practical Sanskrit Introductory by Charles Wikner». sanskritdocuments.org. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Thackston, W. M. (2022). Sorani Kurdish — A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings. Independently Published. ISBN 979-8837159206.

- ^ Nyberg, Henrik (1964). A Manual of Pahlavi: Glossary (in German). Harrassowitz (published 31 December 1974). ISBN 978-3447015806.

- ^ Alphonsa, Alice Celin; Bhanja, Chuya China; Laskar, Azharuddin; Laskar, Rabul Hussain (July 2017). «Spectral feature based automatic tonal and non-tonal language classification». 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT): 1271–1276. doi:10.1109/ICICICT1.2017.8342752. ISBN 978-1-5090-6106-8. S2CID 5060391.

- ^ Galaal, Muuse Haaji Ismaaʻiil; Andrzejewski, Bogumił W. (1956). Hikmaad Soomaali. Oxford University Press.

- ^ B., Alisscia (20 March 2021). Thai-English Picture Book: Thai Consonants, Vowels, 4 Tone Marks, Numbers and Activity Book for Kids | Thai Language Learning. Amazon Digital Services LLC (published 20 March 2021). ISBN 9798725525847.

- ^ Clark, Marybeth (2000), Diexis and anaphora and prelinguistic universals, Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, vol. 29, pp. 46–61

- ^ «Devanagari — an overview | ScienceDirect Topics». www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Street, Julie (10 June 2020). «From A to Z — the surprising history of alphabetical order». ABC News. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Reinhard G. Lehmann: «27-30-22-26. How Many Letters Needs an Alphabet? The Case of Semitic», in: The idea of writing: Writing across borders; edited by Alex de Voogt and Joachim Friedrich Quack, Leiden: Brill 2012, p. 11-52

- ^ Real Academia Española. Exclusión de «ch» y «ll» del abecedario.

- ^ «La ‘i griega’ se llamará ‘ye'». Cuba Debate. 2010-11-05. Retrieved 12 December 2010. Cubadebate.cu

- ^ DIN 5007-1:2005-08 FILING OF CHARACTER STRINGS — PART 1: GENERAL RULES FOR PROCESSING (ABC RULES) (in German). German Institute for Standardisation (Deutsches Institut für Normung). 2005.

- ^ WAGmob (25 December 2013). Learn Danish (Alphabet and Numbers). WAGmob.

- ^ WAGmob (2 January 2014). Learn Norwegian (Alphabet and Numbers). WAGmob.

- ^ Holmes, Philip (2003). Swedish : a comprehensive grammar. Ian Hinchliffe (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415278836. OCLC 52269425.

- ^ Conklin, Harold C. (2007). Fine description : ethnographic and linguistic essays. Joel Corneal Kuipers, Ray McDermott. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. pp. 320–342. ISBN 978-0-938692-85-0. OCLC 131239101.

- ^ Millard 1986, p. 395

- ^ «ScriptSource — Ethiopic (Geʻez)». scriptsource.org. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Elliott, Ralph Warren Victor (1980). Runes, an introduction. Manchester, Eng.: Manchester Univ. Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-7190-0787-9. OCLC 7088245.

- ^ «ترتيب المداخل والبطاقات في القوائم والفهارس الموضوعية — منتديات اليسير للمكتبات وتقنية المعلومات». alyaseer.net. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010). A history of the Japanese language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-511-93242-7. OCLC 695989981.

- ^ «World Wide Words: Acrophony». World Wide Words. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ «The Samaritan Script». The Samaritans. Retrieved 13 December 2022. Notice the «Names of the Letters» Section.

- ^ MacLeod, Ewan (2015). Learn The Aramiac Alphabet. pp. 3–4.

- ^ «Arabic alphabet, ABC — Names in Arabic». 3 February 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Sampson, Geoffrey (1985). Writing systems : a linguistic introduction. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1254-9. OCLC 12745931.

- ^ Pedersen, Loren E. (2016). A simple approach to French pronunciation : a comprehensive guide. Minneapolis, MN. ISBN 978-1-63505-259-6. OCLC 962924935.

- ^ «The Great Vowel Shift». chaucer.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 13 December 2022. Note how it says short vowels are similar between Middle and Modern English.

- ^ Lunt, Horace G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic grammar (7th Revised ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016284-9. OCLC 46421814.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (1992). Frost, Ram; Katz, Leonard (eds.). Beyond Orthographic Depth in Reading: Equitable Division of Labor. Advances in Psychology. ISBN 9780444891402.

- ^ Nordlund, Taru (2012). «Standardization of Finnish Orthography: From Reformists to National Awakeners». Walter de Gruyter: 351–372. doi:10.1515/9783110288179.351. ISBN 9783110288179. S2CID 156286003.

- ^ Rogers, Henry (1 January 1999). «Sociolinguistic factors in borrowed writing systems». Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics. 17. ISSN 1718-3510.

- ^ Reindl, Donald (2005). The Effects of Historical German-Slovene Language Contact on the Slovene Language (Digitized ed.). Indiana University, Department of Slavic Languages and Literature. p. 90.

- ^ Dictionaries, An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Vol. 3rd. Walter De Gruyter. 1991.

- ^ Berecz, Ágoston (2020). Empty signs, historical imaginaries : the entangled nationalization of names and naming in a late Habsburg borderland. New York. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-78920-635-7. OCLC 1135915948.

- ^ Campbell, George L.; King, Gareth (7 December 2018). The Routledge Concise Compendium of the World’s Languages (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis. p. 253. ISBN 9781135692636.

- ^ Allyn, Eric; Chaiyana, Samorn (1995). The Bua Luang What You See is what You Say Thai Phrase Handbook Contemporary Thai-language Phrases in Context, WYSIWYS Easier-to-read Transliteration System. Bua Luang Publishing Company. ISBN 9780942777048. Note in the pronunciation guide next to «เบียร์» it has it being said as, «Bia»

- ^ Strielkowski, Wadim; Birkök, Mehmet; Khan, Intakhab, eds. (2022). Advances in Social Science, Education, and Humanities Research: Proceedings of the 2022 6th international Seminar, on Education, Management, and Social Sciences. Atlantis Press. p. 644. ISBN 978-2-494069-30-5.

- ^ Gasser, Micheal (10 April 2021). «4.5: English Accents». Social Sci LibreTexts. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Workbook/laboratory manual to accompany Yookoso! : an invitation to contemporary Japanese. Sachiko Fuji, Yasuhiko Tohsaku. New York: McGraw-Hill. 1994. ISBN 0-07-072293-5. OCLC 36107173.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Durkin, Philip (2014). Borrowed words : a history of loanwords in English. Oxford Scholarship Online. ISBN 978-0-19-166706-0. OCLC 868265392.

- ^ Joshi, R. Malatesha (2013). Handbook of Orthography and Literacy. P.G. Aaron. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-78134-6. OCLC 1164868444.

- ^ Kambourakis, Kristie McCrary (2007). Reassessing the role of the syllable in Italian phonology : an experimental study of consonant cluster syllabification, definite article allomorphy and segment duration. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-06197-7. OCLC 1226326275.

- ^ «Spanish Pronunciation: The Ultimate Guide | The Mimic Meth». The Mimic Method. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Rochester, Myrna Bell (2009). Easy French step-by-step : master high-frequency grammar for French proficiency—fast!. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-164221-7. OCLC 303676798.

- ^ Denham, Kristin E. (2010). Linguistics for everyone : an introduction. Anne C. Lobeck. Boston, MA: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4130-1589-8. OCLC 432689138.

- ^ Linstead, Stephen (11 December 2014). «English spellings don’t match the sounds they are supposed to represent. It’s time to change | Mind your language». the Guardian. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Zürcher, Erik Jan (2004). Turkey : a modern history (3rd ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 188–189. ISBN 1-4175-5697-8. OCLC 56987767.

- ^ «Нұрсұлтан Назарбаев. Болашаққа бағдар: рухани жаңғыру». 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ О переводе алфавита казахского языка с кириллицы на латинскую графику [On the change of the alphabet of the Kazakh language from the Cyrillic to the Latin script] (in Russian). President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ «ÖZBEK ALIFBOSI». www.evertype.com. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ «Uzbekistan Aims For Full Transition To Latin-Based Alphabet By 2023». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association : a guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65236-7. OCLC 40305532.

Bibliography

- Coulmas, Florian (1989). The Writing Systems of the World. Blackwell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-631-18028-9.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7. Overview of modern and some ancient writing systems.

- Driver, G. R. (1976). Semitic Writing (Schweich Lectures on Biblical Archaeology S.) 3Rev Ed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-725917-7.

- Haarmann, Harald (2004). Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

- Hoffman, Joel M. (2004). In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3654-8. Chapter 3 traces and summarizes the invention of alphabetic writing.

- Logan, Robert K. (2004). The Alphabet Effect: A Media Ecology Understanding of the Making of Western Civilization. Hampton Press. ISBN 978-1-57273-523-1.

- McLuhan, Marshall; Logan, Robert K. (1977). «Alphabet, Mother of Invention». ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 34 (4): 373–383. JSTOR 42575278.

- Millard, A. R. (1986). «The Infancy of the Alphabet». World Archaeology. 17 (3): 390–398. doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979978. JSTOR 124703.

- Ouaknin, Marc-Alain; Bacon, Josephine (1999). Mysteries of the Alphabet: The Origins of Writing. Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-7892-0521-6.

- Powell, Barry (1991). Homer and the Origin of the Greek Alphabet. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58907-9.

- Powell, Barry B. (2009). Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6256-2.

- Sacks, David (2004). Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z. Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-1173-3.

- Saggs, H. W. F. (1991). Civilization Before Greece and Rome. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05031-8. Chapter 4 traces the invention of writing

Further reading

- Josephine Quinn, «Alphabet Politics» (review of Silvia Ferrara, The Greatest Invention: A History of the World in Nine Mysterious Scripts, translated from the Italian by Todd Portnowitz, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022, 289 pp.; and Johanna Drucker, Inventing the Alphabet: The Origins of Letters from Antiquity to the Present, University of Chicago Press, 2022, 380 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 1 (19 January 2023), pp. 6, 8, 10.

External links

Look up alphabet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alphabets.

- The Origins of abc

- «Language, Writing and Alphabet: An Interview with Christophe Rico», Damqātum 3 (2007)

- Michael Everson’s Alphabets of Europe

- Evolution of alphabets, animation by Prof. Robert Fradkin at the University of Maryland

- How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs—Biblical Archaeology Review

- An Early Hellenic Alphabet

- Museum of the Alphabet

- The Alphabet, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Eleanor Robson, Alan Millard and Rosalind Thomas (In Our Time, 18 December 2003)

I heard that it is the names of the first two Greek letters put together. Is this true?

asked Jul 7, 2011 at 19:55

DanielDaniel

57.1k75 gold badges256 silver badges377 bronze badges

Although there are already 2 correct answers, I’d like to add a few points.

But first I’d like to recommend the very informative and very accessible booklet «The Early Alphabet — available on Google book» at least partially — of which I drew the following bullet points.

- The letter alpha originally represented a cow head. If you imagine a capital A upside down, you’ll see that it’s pretty close. It’s Phoenician name was alf which meant «Ox». Hence the Greek «alpha».

- The letter beta was originally a house (actually the bird’s eye view of a square house). In most Semitic languages the word for house is pronounced «Beth, Bayt…». Hence the Greek «beta».

- Gamma is a camel,

- Delta a door,

-

Epsilon a window etc…

-

The order of the letters (all consonants and actually shorthand for syllabaries) was actually fixed very early. One of the earliest of these abecedaries is actually still written in cuneiforms (a syllabic writing system) and is more than 3200 years old.

answered Jul 7, 2011 at 21:17

Alain Pannetier ΦAlain Pannetier Φ

17.7k3 gold badges57 silver badges109 bronze badges

Yes, it is true. Etymonline.com says:

560s (implied in alphabetical), from L.L. alphabetum (Tertullian), from Gk. alphabetos, from alpha + beta.

Alpha is the first letter in the Greek «alphabet», and Beta is the second.

Hellion

59.1k21 gold badges130 silver badges212 bronze badges

answered Jul 7, 2011 at 19:58

ThursagenThursagen

41.4k43 gold badges165 silver badges241 bronze badges

4

The alphabet entry in Etymonline includes:

1560s (implied in alphabetical), from L.L. alphabetum (Tertullian), from Gk. alphabetos, from alpha + beta.

The Wiktionary entry for alphabet also adds:

… Ancient Greek ἀλφάβητος (alphabētos), from the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha (Α) and beta (Β), from Phoenician aleph (“ox”) and beth (“house”), so called because they were pictograms of those objects.

answered Jul 7, 2011 at 20:04

aedia λaedia λ

10.6k9 gold badges44 silver badges69 bronze badges

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Table of Contents

- What is the root word of alphabet?

- Is alphabet Latin or Greek?

- What does the word alphabet stand for?

- What does the letter Z mean in the Bible?

- Why is z zed?

- What is the Hebrew letter for Z?

- What does Yod symbolize?

- Is a Yod rare?

- What does the letter Y look like in Hebrew?

- What does the word ten mean in Hebrew?

- How is w pronounced in Hebrew?

- Is W pronounced V in Hebrew?

- What does V mean in Hebrew?

- Does VAV mean nail?

- How do you write 666 in Hebrew?

- What is the Hebrew symbol for the number six?

The Greek letters get their name from Phoenician and/or Hebrew. “Alef” means “ox” (the letter derives from an even older glyph representing an ox) and “be(j)t” means house (same thing). So the word alphabet sort of derives from all three languages. Yes, this is the origin of the word.

What is the root word of alphabet?

Etymology. The English word alphabet came into Middle English from the Late Latin word alphabetum, which in turn originated in the Greek ἀλφάβητος (alphabētos). The Greek word was made from the first two letters, alpha(α) and beta(β).

Is alphabet Latin or Greek?

The Latin alphabet evolved from the visually similar Etruscan alphabet, which evolved from the Cumaean Greek version of the Greek alphabet, which was itself descended from the Phoenician alphabet, which in turn derived from Egyptian hieroglyphics.

What does the word alphabet stand for?

1a : a set of letters or other characters with which one or more languages are written especially if arranged in a customary order. b : a system of signs or signals that serve as equivalents for letters. 2 : rudiments, elements.

What does the letter Z mean in the Bible?

Z in Hebrew is Zayin and it means ‘sword’ or ‘a weapon of the spirit. ‘ A sword can cut through confusion, it can cut down one’s enemies, and it stands for Air, one of the four elements. With that, it also stands for ‘thought’ as well as ‘word.

Why is z zed?

The British and others pronounce “z”, “zed”, owing to the origin of the letter “z”, the Greek letter “Zeta”. This gave rise to the Old French “zede”, which resulted in the English “zed” around the 15th century.

What is the Hebrew letter for Z?

Zayin

| ← Waw Zayin Heth → | |

|---|---|

| Phonemic representation | z |

| Position in alphabet | 7 |

| Numerical value | 7 |

| Alphabetic derivatives of the Phoenician |

What does Yod symbolize?

“Yod” in the Hebrew language signifies iodine. Iodine is also called يود yod in Arabic.

Is a Yod rare?

“THE FINGER OF GOD” A Yod, also known as the “Finger of God”, or the “Finger of Fate”, is a rare astrological aspect that involves any 3 planets or points in the horoscope that form an isoscoles triangle.

What does the letter Y look like in Hebrew?

The Modern Hebrew name yud is a derivative of the two letter word (yad), a Hebrew word meaning “hand,” the original name for the letter….Yud.

| Ancient Name: | Yad |

|---|---|

| Sound: | Y, iy |

What does the word ten mean in Hebrew?

The Hebrew word for the number ten is pronounced, `eser and looks like this: עשר The first character is the `ayin, ע, and symbolically means to see, eye, discern, or divine providence. The second character is the Shin, ש, and symbolically means the tree of life, burning bush, God’s spirit, etc.

How is w pronounced in Hebrew?

, Hebrew waw/vav ו, Syriac waw ܘ and Arabic wāw و (sixth in abjadi order; 27th in modern Arabic order). It represents the consonant [w] in original Hebrew, and [v] in modern Hebrew, as well as the vowels [u] and [o]….Arabic wāw.

| wāw | |

|---|---|

| Phonetic usage | /w/, /v/, /uː/ |

| Alphabetical position | 4 |

| History | |

| Development | و |

Is W pronounced V in Hebrew?

The letter “vav” is pronounced “v” in modern Hebrew. However, in ancient Hebrew it was pronounced “w”. Many Yemenite Jews still pronounce it “w” when praying in the synagogue.

What does V mean in Hebrew?

The tent pegs were made of wood and may have been Y-shaped to prevent the rope from slipping off. The Modern Hebrew name for this letter is vav, a word meaning “peg” or “hook.” This letter is used as a consonant with a “v” sound and as a vowel with a “ow” and “uw” sound.

Does VAV mean nail?

Vav is the sixth letter of the Hebrew aleph-bet. It means hook, nail or tent peg. As the pictograph indicates, this letter represents a peg or hook, which is used for securing something.

How do you write 666 in Hebrew?

Nero Caesar in Hebrew is NeRON QeiSaR; adding up the letters we get “the number of the man”, 666. This kind of numerical signature is called gematria, and is still used in Hebrew and Arabic.

What is the Hebrew symbol for the number six?

ו

- Abkhaz: алфавит (alfavitʼ)

- Adyghe: тхыпкъылъэ (txəpqəlˢe)

- Afrikaans: alfabet (af)

- Albanian: alfabet (sq) m

- Alemannic German: Alphabet

- Amharic: ፊደል (fidäl)

- Apache:

- Western Apache: biabcʼhíí (their alphabet), abcʼhí

- Arabic: حُرُوف الْهِجَاء m pl (ḥurūf al-hijāʔ), أَبْجَد (ar) m (ʔabjad), أَلِفْبَاء m (ʔalifbāʔ), أَلِفْبَائِيَّة f (ʔalifbāʔiyya), أَبْجَدِيَّة f (ʔabjadiyya)

- Aramaic: ܐܠܦܒܝܬ

- Armenian: այբուբեն (hy) (aybuben)

- Assamese: বৰ্ণমালা (bornomala)

- Asturian: alfabetu (ast) m

- Azerbaijani: əlifba (az)

- Bashkir: әлифба (älifba)

- Basque: alfabeto (eu)

- Belarusian: алфаві́т m (alfavít), а́збука f (ázbuka), альфабэ́т m (alʹfabét), абяца́дла f (abjacádla), абэцэ́да f (abecéda) (Latin alphabet)

- Bengali: বর্ণমালা (bornomala)

- Bikol Central: alpabeto

- Breton: lizherenneg (br) f

- Bulgarian: а́збука (bg) f (ázbuka), алфави́та f (alfavíta) (dated)

- Burmese: အက္ခရာ (my) (akhka.ra)

- Catalan: alfabet (ca) m, abecedari (ca) m

- Chinese:

- Dungan: зыму (zɨmu), элифбе (elifbi͡ə)

- Mandarin: 字母 (zh) (zìmǔ), 字母表 (zh) (zìmǔbiǎo), 字母系統/字母系统 (zìmǔ xìtǒng)

- Chuvash: алфавит (alfavit)

- Cornish: lytherennek f, abecedari m

- Corsican: alfabetu (co) m

- Czech: abeceda (cs) f

- Danish: alfabet (da) n

- Dhivehi: އަލިފުބާ (alifubā)

- Dinka: kïndegɔ̈t

- Dutch: ABC (nl) n, alfabet (nl) n

- Esperanto: alfabeto (eo)

- Estonian: tähestik (et), alfabeet (et)

- Faroese: bókstavarað n, stavrað n, stavarað n

- Finnish: aakkoset (fi) pl, aakkosto (fi), aakkosisto

- French: alphabet (fr) m

- Gagauz: alfavit

- Galician: alfabeto (gl) m

- Georgian: ანბანი (ka) (anbani)

- German: ABC (de) n, Alphabet (de) n

- Greek: αλφάβητο (el) n (alfávito), αλφαβήτα (el) f (alfavíta)

- Ancient: ἀλφάβητος m (alphábētos)

- Greenlandic: alfabet, oqaasiliuutissat, qanermissarissat

- Guaraní: achegety

- Haitian Creole: abese

- Hebrew: אָלֶף־בֵּית (he) m (alef-bét), אָלֶפְבֵּית (he) m (alefbét)

- Hindi: वर्णमाला (hi) f (varṇamālā), मूलाक्षर m (mūlākṣar), अक्षरमाला (hi) f (akṣarmālā)

- Hungarian: ábécé (hu)

- Icelandic: stafróf (is) n, rittáknakerfi n

- Ido: alfabeto (io)

- Indonesian: abjad (id), alfabet (id), aksara (id)

- Interlingua: alphabeto

- Irish: aibítir (ga) f, aibidil f

- Old Irish: apgitir f

- Italian: alfabeto (it) m

- Japanese: アルファベット (ja) (arufabetto) (often of Roman and other foreign alphabets), 文字 (ja) (もじ, moji)

- Javanese: aksara (jv), alfabèt

- Kannada: ಅಕ್ಷರಮಾಲೆ (kn) (akṣaramāle)

- Kazakh: әліпби (älıpbi), әліппе (älıppe), алфавит (kk) (alfavit)

- Khmer: អក្ខរក្រម (km) (ʼakkhaʼraa krɑm), អក្សរ (km) (ʼaksɑɑ)

- Korean: 알파벳 (ko) (alpabet) (often of Roman and other foreign alphabets), 문자(文字) (ko) (munja), 음소문자(音素文字) (ko) (eumsomunja)

- Kumyk: алифба (alifba)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: alfabe (ku)

- Kyrgyz: алфавит (ky) (alfavit), алиппе (ky) (alippe)

- Lakota: oówaptaya

- Lao: ໂຕຫນັງສື (tō nang sư̄), ແມ່ກໍກາ (mǣ kǭ kā), ອັກສອນ (ʼak sǭn)

- Latin: alphabetum (la) n, abecedārium (la) n

- Latvian: alfabēts m

- Lithuanian: abėcėlė (lt) f, alphabet (lt) m, alfabetas m

- Luxembourgish: Alphabet (lb) n

- Macedonian: азбука f (azbuka)

- Malagasy: abidy (mg)

- Malay: abjad (ms), huruf (ms), aksara (ms)

- Jawi: ابجد, حروف, اکسارا

- Malayalam: അക്ഷരമാല (ml) (akṣaramāla)

- Maltese: alfabet

- Manx: abbyrlhit

- Maori: tātai reta, arapū

- Marathi: मुळाक्षरे (muḷākṣare), वर्णमाला (varṇamālā)

- Middle Dutch: please add this translation if you can

- Middle English: abece

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: цагаан толгой (cagaan tolgoj)

- Navajo: saad bee álʼíní, áábée

- Nepali: वर्णमाला (varṇamālā)

- Northern Sami: alfabēhta

- Norwegian: abc (no), alfabet (no) n

- Bokmål: alfabet (no) n

- Nynorsk: alfabet n

- Occitan: alfabet (oc) m

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: аꙁъбоукꙑ f (azŭbuky)

- Old East Slavic: азбукꙑ f (azbuky)

- Old English: stæfrof

- Old Norse: stafróf

- Oromo: qubee

- Ossetian: абетӕ (abetæ), алфавит (alfavit)

- Pashto: الفبې (ps) f (alefbé)

- Pennsylvania German: Aa-Be-Ze

- Persian: الفبا (fa) (alefbâ)

- Polish: alfabet (pl) m inan, abecadło (pl) n

- Portuguese: abc m, abecê (pt) m, á-bê-cê (pt) m, alfabeto (pt) m, abecedário (pt) m

- Romani: alfabéto m

- Romanian: alfabet (ro) n

- Russian: алфави́т (ru) m (alfavít), а́збука (ru) f (ázbuka)

- Rusyn: алфаві́т m (alfavít), а́збука f (ázbuka)

- Sanskrit: अक्षरसमाम्नाय (sa) m (akṣarasamāmnāya)

- Scottish Gaelic: aibidil f

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: а̀збука f (Cyrillic alphabet), абеце́да f (Roman alphabet), алфа̀бе̄т m

- Roman: àzbuka (sh) f (Cyrillic alphabet), abecéda (sh) f (Roman alphabet), alfàbēt (sh) m

- Skolt Sami: alfabeʹtt

- Slovak: abeceda (sk) f

- Slovene: abeceda (sl) f

- Southern Sami: alfabeete

- Spanish: alfabeto (es) m, abecedario (es) m

- Swahili: alfabeti (sw)

- Swedish: ABC (sv) n, alfabet (sv) n

- Tagalog: alpabeto (tl), abakada (tl),

- Tajik: алифбо (tg) (alifbo)

- Tamil: அகரவரிசை (akaravaricai), நெடுங்கணக்கு (ta) (neṭuṅkaṇakku)

- Tatar: әлифба (tt) (älifba)

- Telugu: అక్షరమాల (te) (akṣaramāla)

- Thai: ตัวอักษร (th) (dtuua-àk-sɔ̌ɔn), อักษร (th) (àk-sɔ̌ɔn)

- Tibetan: ཀ་ཁ (ka kha)

- Tigrinya: ፊደል (fidäl)

- Turkish: alfabe (tr), abece (tr)

- Turkmen: elipbiý

- Udi: тӏетӏир (ṭeṭir)

- Ukrainian: абе́тка (uk) f (abétka), алфаві́т (uk) m (alfavít), а́збука (uk) f (ázbuka), альфабе́т m (alʹfabét), алфа́віт (uk) m (alfávit) (alternative stress, rare)

- Urdu: حروف تہجی (harūf tahajī)

- Uyghur: ئالفابىت (alfabit), ئېلىپبە (ëlipbe)

- Uzbek: alifbo (uz)

- Vietnamese: bảng chữ cái

- Vilamovian: alfabet n

- Volapük: lafab (vo)

- Võro: tähistü

- Walloon: alfabet (wa)

- Welsh: gwyddor (cy) f

- West Frisian: alfabet (fy) n

- Winnebago: woowagax

- Yakut: алфавит (alfavit)

- Yiddish: אַלף־בית (yi) m (alef-beys) (Hebrew alphabet), אַלפֿאַבעט f (alfabet) (Latin alphabet), גלחות n (galkhes) (Latin alphabet), אַזבוקע f (azbuke) (Cyrillic alphabet)

- Yup’ik: igat