Morphology is the study of words and their parts. Morphemes, like prefixes, suffixes and base words, are defined as the smallest meaningful units of meaning. Morphemes are important for phonics in both reading and spelling, as well as in vocabulary and comprehension.

Why use morphology

Teaching morphemes unlocks the structures and meanings within words. It is very useful to have a strong awareness of prefixes, suffixes and base words. These are often spelt the same across different words, even when the sound changes, and often have a consistent purpose and/or meaning.

Types of morphemes

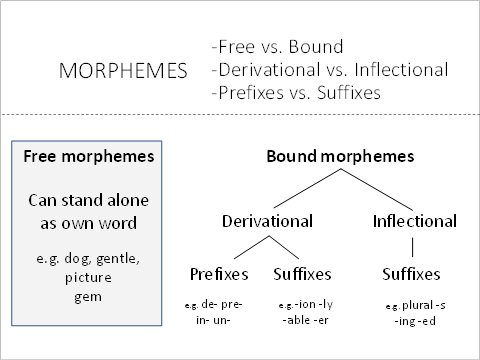

Free vs. bound

Morphemes can be either single words (free morphemes) or parts of words (bound morphemes).

A free morpheme can stand alone as its own word

- gentle

- father

- licence

- picture

- gem

A bound morpheme only occurs as part of a word

- -s as in cat+s

- -ed as in crumb+ed

- un- as in un+happy

- mis- as in mis-fortune

- -er as in teach+er

In the example above: un+system+atic+al+ly, there is a root word (system) and bound morphemes that attach to the root (un-, -atic, -al, -ly)

system = root un-, -atic, -al, -ly = bound morphemes

If two free morphemes are joined together they create a compound word. These words are a great way to introduce morphology (the study of word parts) into the classroom.

For more details, see:

Compound words

Inflectional vs. derivational

Morphemes can also be divided into inflectional or derivational morphemes.

Inflectional morphemes change what a word does in terms of grammar, but does not create a new word.

For example, the word <skip> has many forms: skip (base form), skipping (present progressive), skipped (past tense).

The inflectional morphemes -ing and -ed are added to the base word skip, to indicate the tense of the word.

If a word has an inflectional morpheme, it is still the same word, with a few suffixes added. So if you looked up <skip> in the dictionary, then only the base word <skip> would get its own entry into the dictionary. Skipping and skipped are listed under skip, as they are inflections of the base word. Skipping and skipped do not get their own dictionary entry.

Skip

verb, skipped, skipping.

- to move in a light, springy manner by bounding forward with alternate hops on each foot. to pass from one point, thing, subject, etc.,

- to another, disregarding or omitting what intervenes: He skipped through the book quickly.

- to go away hastily and secretly; flee without notice.

From

Dictionary.com — skip

Another example is <run>: run (base form), running (present progressive), ran (past tense). In this example the past tense marker changes the vowel of the word: run (rhymes with fun), to ran (rhymes with can). However, the inflectional morphemes -ing and past tense morpheme are added to the base word <run>, and are listed in the same dictionary entry.

Run

verb, ran, run, running.

- to go quickly by moving the legs more rapidly than at a walk and in such a manner that for an instant in each step all or both feet are off the ground.

- to move with haste; act quickly: Run upstairs and get the iodine.

- to depart quickly; take to flight; flee or escape: to run from danger.

From

Dictionary.com — run

Derivational morphemes are different to inflectional morphemes, as they do derive/create a new word, which gets its own entry in the dictionary. Derivational morphemes help us to create new words out of base words.

For example, we can create new words from <act> by adding derivational prefixes (e.g. re- en-) and suffixes (e.g. -or).

Thus out of <act> we can get re+act = react en+act = enact act+or = actor.

Whenever a derivational morpheme is added, a new word (and dictionary entry) is derived/created.

For the <act> example, the following dictionary entries can be found:

Act

noun

- anything done, being done, or to be done; deed; performance: a heroic act.

- the process of doing: caught in the act.

- a formal decision, law, or the like, by a legislature, ruler, court, or other authority; decree or edict; statute; judgement, resolve, or award: an act of Parliament.

From

Dictionary.com — act

React

verb

- to act in response to an agent or influence: How did the audience react to the speech?

- to act reciprocally upon each other, as two things.

- to act in a reverse direction or manner, especially so as to return to a prior condition.

From

Dictionary.com — react

Enact

verb

- to make into an act or statute: Parliament has enacted a new tax law.

- to represent on or as on the stage; act the part of: to enact Hamlet.

From

Dictionary.com — enact

Actor

noun

- a person who acts in stage plays, motion pictures, television broadcasts, etc.

- a person who does something; participant.

From

Dictionary.com — actor

Teachers should highlight and encourage students to analyse both Inflectional and Derivational morphemes when focussing on phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.

For more information, see:

Prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases

Many morphemes are very helpful for analysing unfamiliar words. Morphemes can be divided into prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases.

- Prefixes are morphemes that attach to the front of a root/base word.

- Suffixes are morphemes that attach to the end of a root/base word, or to other suffixes (see example below)

- Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning.

- Generally, base words are free morphemes, that can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

- Whereas root words are bound morphemes that cannot stand by themselves (e.g. -ject as in subject/reject, and -volve as in evolve/revolve).

Most morphemes can be divided into:

- Anglo-Saxon Morphemes (like re-, un-, and -ness);

- Latin Morphemes (like non-, ex-, -ion, and -ify); and

- Greek Morphemes (like micro, photo, graph).

It is useful to highlight how words can be broken down into morphemes (and which each of these mean) and how they can be built up again).

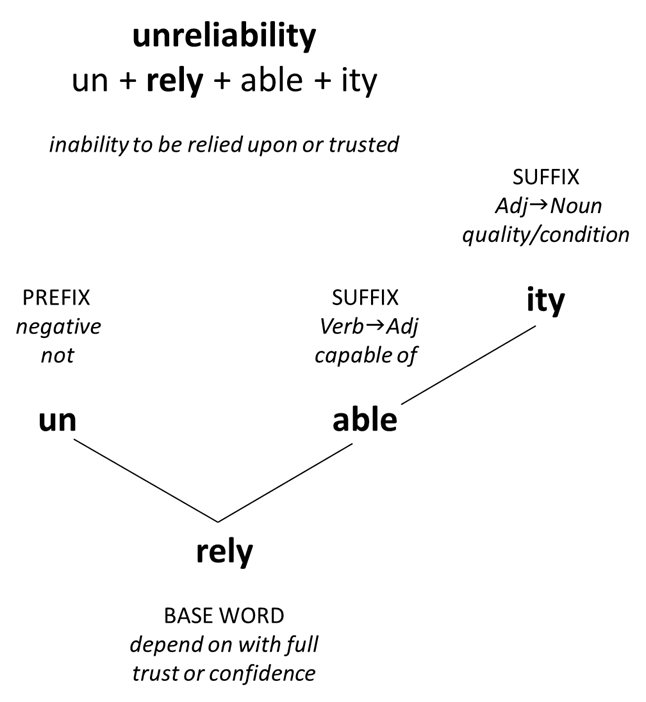

For example, the word <unreliability> may be unfamiliar to students when they first encounter it.

If <unreliability> is broken into its morphemes, students can deduce or infer the meaning.

So it is helpful for both reading and spelling to provide opportunities to analyse words, and become familiar with common morphemes, including their meaning and function.

Compound words

Compound words (or compounds) are created by joining free morphemes together. Remember that a free morpheme is a morpheme that can stand along as its own word (unlike bound morphemes — e.g. -ly, -ed, re-, pre-). Compounds are a fun and accessible way to introduce the idea that words can have multiple parts (morphemes). Teachers can highlight that these compound words are made up of two separate words joined together to make a new word. For example dog + house = doghouse

Examples

- lifetime

- basketball

- cannot

- fireworks

- inside

- upside

- footpath

- sunflower

- moonlight

- schoolhouse

- railroad

- skateboard

- meantime

- bypass

- sometimes

- airport

- butterflies

- grasshopper

- fireflies

- footprint

- something

- homemade

- backbone

- passport

- upstream

- spearmint

- earthquake

- backward

- football

- scapegoat

- eyeball

- afternoon

- sandstone

- meanwhile

- limestone

- keyboard

- seashore

- touchdown

- alongside

- subway

- toothpaste

- silversmith

- nearby

- raincheck

- blacksmith

- headquarters

- lukewarm

- underground

- horseback

- toothpick

- honeymoon

- bootstrap

- township

- dishwasher

- household

- weekend

- popcorn

- riverbank

- pickup

- bookcase

- babysitter

- saucepan

- bluefish

- hamburger

- honeydew

- thunderstorm

- spokesperson

- widespread

- hometown

- commonplace

- supermarket

Example activities of highlighting morphemes for phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension

There are numerous ways to highlight morphemes for the purpose of phonics, vocabulary and comprehension activities and lessons.

Highlighting the morphology of words is useful for explaining phonics patterns (graphemes) and spelling rules, as well as discovering the meanings of unfamiliar words, and demonstrating how words are linked together. Highlighting and analysing morphemes is also useful, therefore, for providing comprehension strategies.

Examples of how to embed morphological awareness into literacy activities can include:

- Sorting words by base/root words (word families), or by prefixes or suffixes

- Word Detective — Students break longer words down into their prefixes, suffixes, and base words

- e.g. Find the morphemes in multi-morphemic words like: dissatisfied unstoppable ridiculously hydrophobic metamorphosis oxygenate fortifications

- Word Builder — students are given base words and prefixes/suffixes and see how many words they can build, and what meaning they might have:

- Prefixes: un- de- pre- re- co- con-

Base Words: play help flex bend blue sad sat

Suffixes: -ful -ly -less -able/-ible -ing -ion -y -ish -ness -ment - Etymology investigation — students are given multi-morphemic words from texts they have been reading and are asked to research the origins (etymology) of the word. Teachers could use words like progressive, circumspect, revocation, and students could find out the morphemes within each word, their etymology, meanings, and use.

2. Dividing words into morphemes

Divide the following words by placing a + between their morphemes. (Some of the words may be monomorphemic and therefore indivisible.)

Example: replaces = re + place + s

4. Matching morpheme types

Write the one proper description from the list under B for the italicized part of each word in A.

|

A |

B |

|---|---|

|

|

|

5. Zulu

Part One

Consider the following nouns in Zulu and proceed to look for the recurring forms.

umfazi ‘married woman’

umfani ‘boy’

umzali ‘parent’

umfundisi ‘teacher’

umbazi ‘carver’

umlimi ‘farmer’

umdlali ‘player’

umfundi ‘reader’

abafazi ‘married women’

abafani ‘boys’

abazali ‘parents’

abafundisi ‘teachers’

ababazi ‘carvers’

abalimi ‘farmers’

abadlali ‘players’

abafundi ‘readers’

a. What is the morpheme meaning ‘singular’ in Zulu?

The morpheme meaning singular in Zulu is “um.”

b. What is the morpheme meaning ‘plural’ in Zulu?

The morpheme meaning plural in Zulu is “aba.”

|

Stems (singular) |

Meanings |

|

um + fazi (married woman) |

prefix + adjective + noun |

|

um + fani (boy) |

prefix + noun |

|

um + zali (parent) |

prefix + noun |

|

um + fundisi (teacher) |

prefix + verb + suffix |

|

um + bazi (carver) |

prefix + verb + suffix |

|

um + limi (farmer) |

prefix + verb + suffix |

|

um + dlali (player) |

prefix + verb + suffix |

|

um + fundi (reader) |

prefix + verb + suffix |

|

Stems (plural) |

Meanings |

|---|---|

|

aba + fazi (married women) |

prefix + verb + noun |

|

aba + fani (boys) |

prefix + noun + suffix |

|

aba + zali (parents) |

prefix + noun+ suffix |

|

aba + fundisi (teachers) |

prefix + noun + suffix |

|

aba + bazi (carvers) |

prefix + noun + suffix |

|

aba + limi (farmers) |

prefix + noun + suffix |

|

aba + dlali (players) |

prefix + noun + suffix |

|

aba + fundi (readers) |

prefix + noun + suffix |

Part 2

The following Zulu verbs are derived from noun stems by adding a verbal suffix.

fundisa ‘to teach’

lima ‘to cultivate’

funda ‘to read’

baza ‘to carve’

The derivational suffix that species the category verb is “-a.”

The nominal suffix that forms nouns is “-i.”

In Zulu, nouns are formed by having having the suffix -i at the end of a word.

The stem morpheme ‘read’ is um + fun → umfun

The stem morpheme meaning ‘read’ is um + ba → umba

6. Swedish

Sweden has given the world the rock group ABBA, the automobile Volvo, and the great film director Ingmar Bergman. The Swedish language offers us a noun morphology that you can analyze with the knowledge gained reading this chapter. Consider these Swedish noun forms:

en lampa ‘a lamp’

en stol ‘a chair’

en matta ‘a carpet’

lampor ‘lamps’

stolar ‘chairs’

mattor ‘carpets’

lampan ‘the lamp’

stolen ‘the chair’

mattan ‘the carpet’

lamporna ‘the lamps’

stolarna ‘the chairs’

mattorna ‘the carpets’

en bil ‘a car’

en soffa ‘a sofa’

en tratt ‘a funnel’

bilar ‘cars’

soffor ‘sofas’

trattar ‘funnels’

bilen ‘the car’

soffan ‘the sofa’

tratten ‘the funnel’

bilarna ‘the cars’

sofforna ‘the sofas’

trattarna ‘the funnels’

a. What is the Swedish word for the indefinite article a (or an)?

The Swedish word for the indefinite article a is “en.”

b. What are the two forms of the plural morpheme in this data? How can you tell which form applies?

The two forms of the plural morpheme in this data are “-ar” and “-or.” The “-ar” morpheme is used when a word ends in a consonant, while the “-or” morpheme is used when a word ends with a vowel. I figured out how this form applies by observing the plural and singular forms of the words.

|

Swedish word (singular) |

Proposed plural suffix |

Actual plural form |

|---|---|---|

|

lampa |

-or |

lampor |

|

matta |

-or |

mattor |

|

stol |

-ar |

stolar |

|

bil |

-ar |

bilar |

|

soffa |

-or |

soffor |

|

tratt |

-ar |

trattar |

By observing the words side by side, I saw a pattern with words that ended with a vowel and words that ended with a consonant. I was able to see that words that ended with a consonant had the “-ar” plural morpheme, while words that ended with a consonant had a “-or” plural morpheme.

c. What are the two forms of the morpheme that make a singular word definite, that is, correspond to the English article the? How can you tell which form applies?

The two forms of the morpheme that make a singular word definite are “-en” and “-n.” Similar to the previous question, I observed the singular form and the definite form in order to find the two morpheme forms.

|

Swedish word (singular) |

Proposed definite suffix |

Actual definite form |

|---|---|---|

|

stol |

-en |

stolen |

|

matta |

-n |

mattan |

|

bil |

-en |

bilen |

|

soffa |

-n |

soffan |

|

tratt |

-en |

tratten |

This observation equates the observation from the previous question because the pattern is the same. Words that end with a consonant have an “-en” definite morpheme, while words that end with a vowel have an “-n” definite morpheme.

d. What is the morpheme that makes a plural word definite?

The morpheme that makes a plural word definite is “-na.” Again, I found this pattern by using a table to compare plural word forms and their definite plural word forms.

|

Swedish word (plural) |

Proposed definite form |

Actual definite form |

|---|---|---|

|

lampor |

-na |

lamporna |

|

mattor |

-na |

mattorna |

|

stolar |

-na |

stolarna |

|

bilar |

-na |

bilarna |

|

soffor |

-na |

sofforna |

|

trattar |

-na |

trattarna |

The various suffixes occur following one another. For example, the word “lampa” uses the plural form in order to get “lampor” and then if someone wanted the plural definite form, then they would add the “-na” suffix, and if they want the singular form, then they would add the singular definite form “-en.”

These are the forms for ‘girls,’ ‘the girl,’ and ‘the girls’:

|

Plural form |

Definite form |

Definite plural form |

|---|---|---|

|

flickor |

flicken |

flickorna |

These are the forms for ‘buses’ and ‘the bus’:

|

Plural form |

Definite form |

|---|---|

|

bussar |

bussen |

15. Parent and Child Dialogue

Consider the following dialogue between parent and schoolchild:

PARENT: When will you be done with your eight-page book report, dear?

CHILD: I haven’t started it yet.

PARENT: But it’s due tomorrow, you should have begun weeks ago. Why do you always wait until the last minute?

CHILD: I have more confidence in myself than you do.

PARENT: Say what?

CHILD: I mean, how long could it possibly take to read an eight-page book?

The humor is based on the ambiguity of the compound eight-page book report. Draw two trees similar to those in the text for top hat rack to reveal the ambiguity.

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

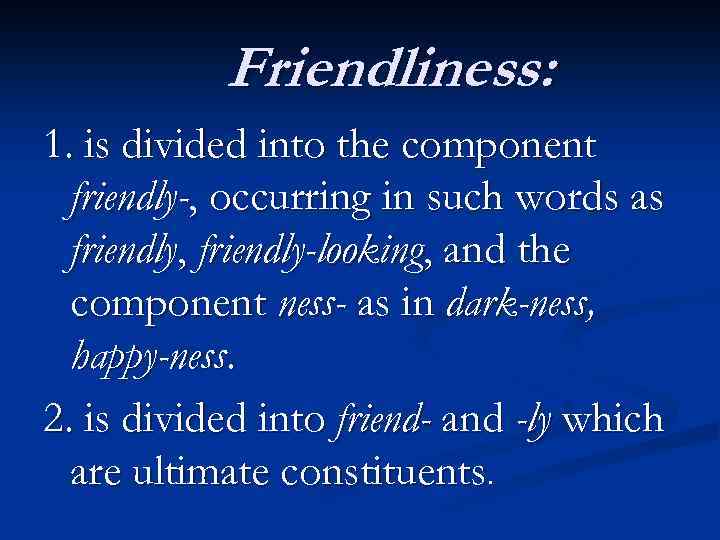

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27509

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

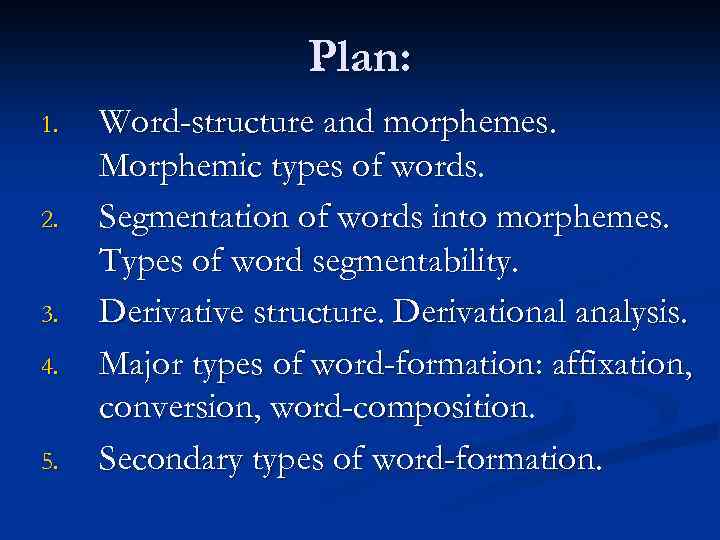

Lecture 6 Word-structure and Word-formation

Plan: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Word-structure and morphemes. Morphemic types of words. Segmentation of words into morphemes. Types of word segmentability. Derivative structure. Derivational analysis. Major types of word-formation: affixation, conversion, word-composition. Secondary types of word-formation.

1. Word-structure and morphemes. Morphemic types of words

The Morpheme: the smallest ____ indivisible two-facet language unit.

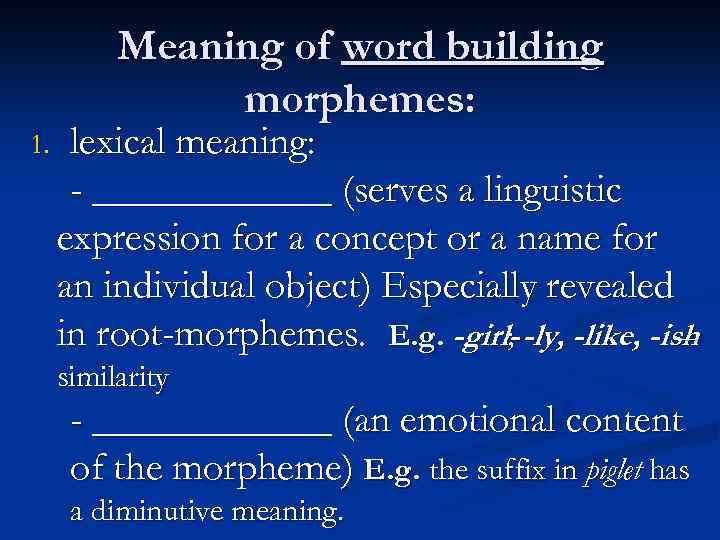

Meaning of word building morphemes: 1. lexical meaning: — ______ (serves a linguistic expression for a concept or a name for an individual object) Especially revealed in root-morphemes. E. g. -girl- -ly, -like, -ish ; – similarity — ______ (an emotional content of the morpheme) E. g. the suffix in piglet has a diminutive meaning.

Word building morphemes do not possess grammatical meaning.

Meaning of word building morphemes: 2. part-of-speech meaning (is proper only to _______) (government, teach-er)

Specific meaning of word building morphemes: n Differential: serves to distinguish words having the same morphemes (over-cook, under cook, precook) n Distributional (the meaning of morpheme arrangement in a word: certain morphemes usually follow or precede the root) (un-effective, speech-less)

Semantic Classification of Morphemes: ______ morpheme (the lexical center of words, has an individual meaning) n non-root or ______ morpheme. n

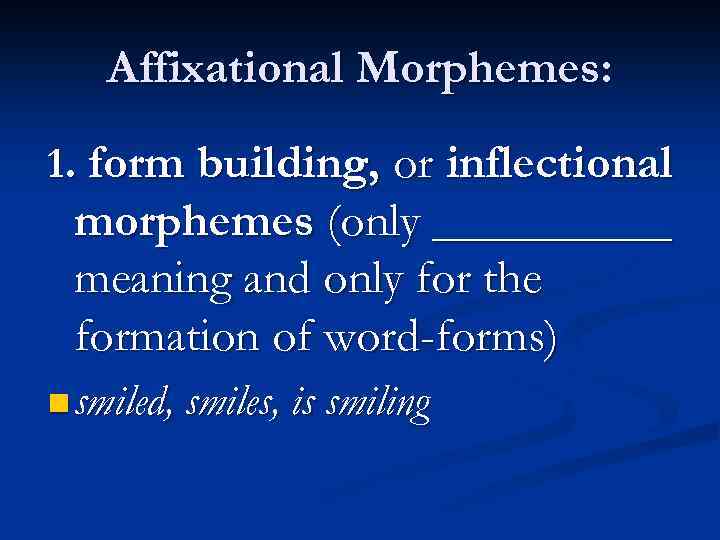

Affixational Morphemes: 1. form building, or inflectional morphemes (only _____ meaning and only for the formation of word-forms) n smiled, smiles, is smiling

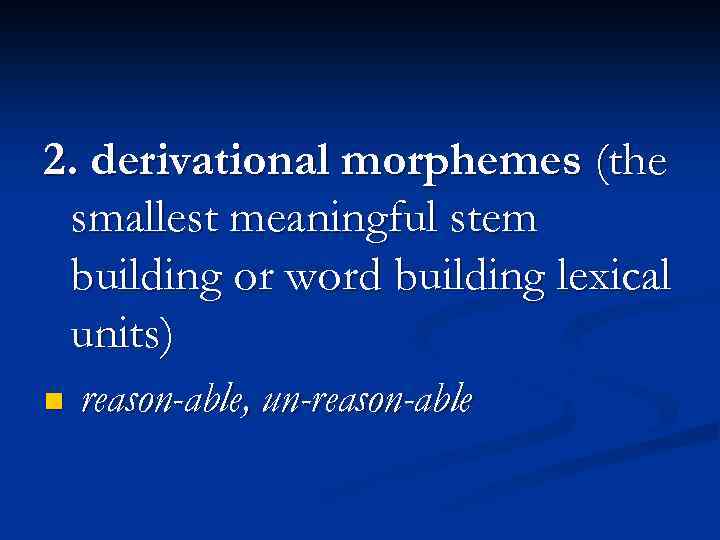

2. derivational morphemes (the smallest meaningful stem building or word building lexical units) n reason-able, un-reason-able

Derivational morphemes: n prefixes n suffixes

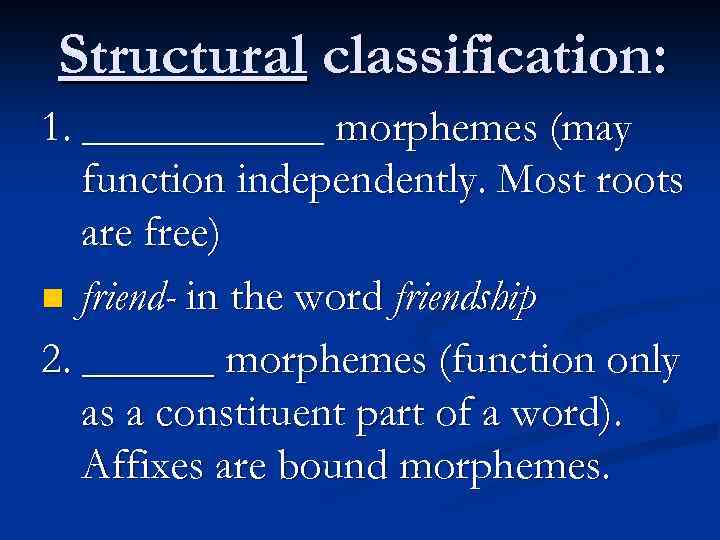

Structural classification: 1. ______ morphemes (may function independently. Most roots are free) n friend- in the word friendship 2. ______ morphemes (function only as a constituent part of a word). Affixes are bound morphemes.

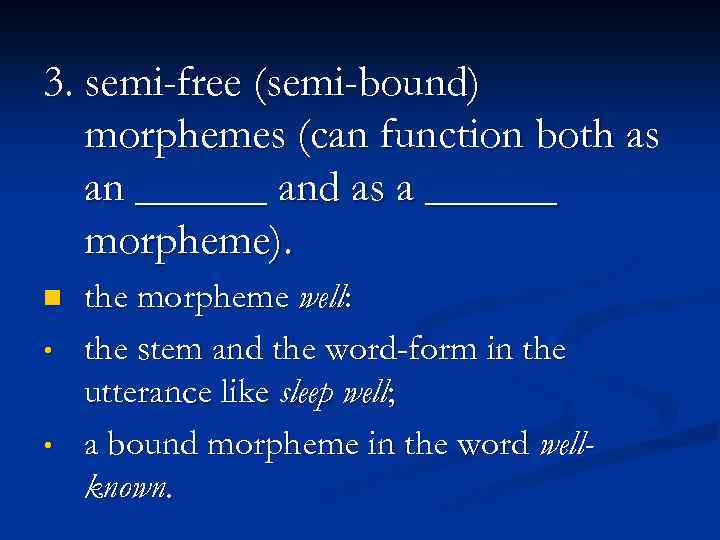

3. semi-free (semi-bound) morphemes (can function both as an ______ and as a ______ morpheme). n • • the morpheme well: the stem and the word-form in the utterance like sleep well; a bound morpheme in the word wellknown.

According to the Number of the Morphemes: § monomorphic words § polymorphic

Monomorphic or root -words: only one rootmorpheme. § small, dog.

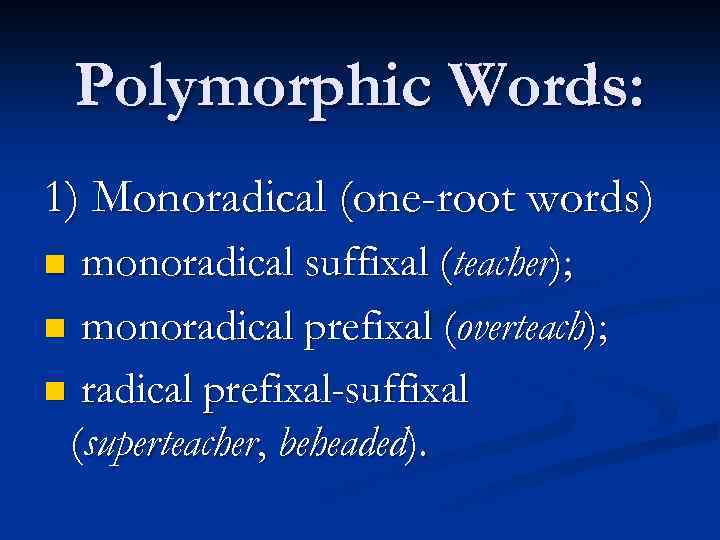

Polymorphic Words: 1) Monoradical (one-root words) monoradical suffixal (teacher); n monoradical prefixal (overteach); n radical prefixal-suffixal (superteacher, beheaded). n

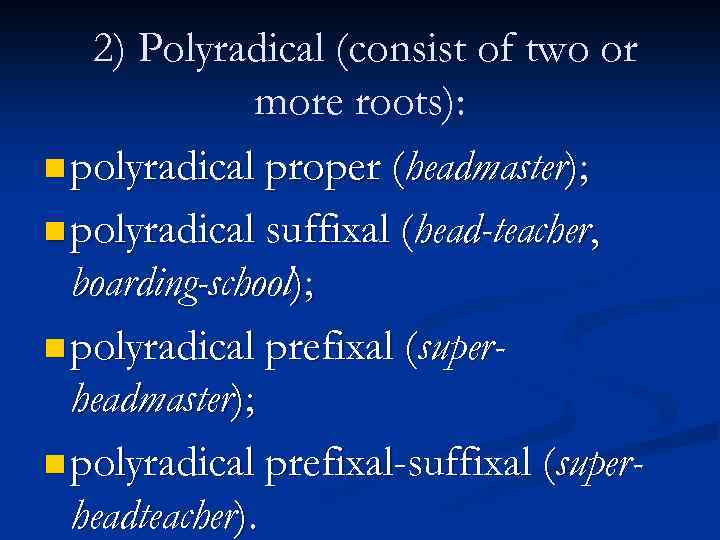

2) Polyradical (consist of two or more roots): n polyradical proper (headmaster); n polyradical suffixal (head-teacher, boarding-school); n polyradical prefixal (superheadmaster); n polyradical prefixal-suffixal (superheadteacher).

2. Segmentation of words into morphemes. Types of word segmentability

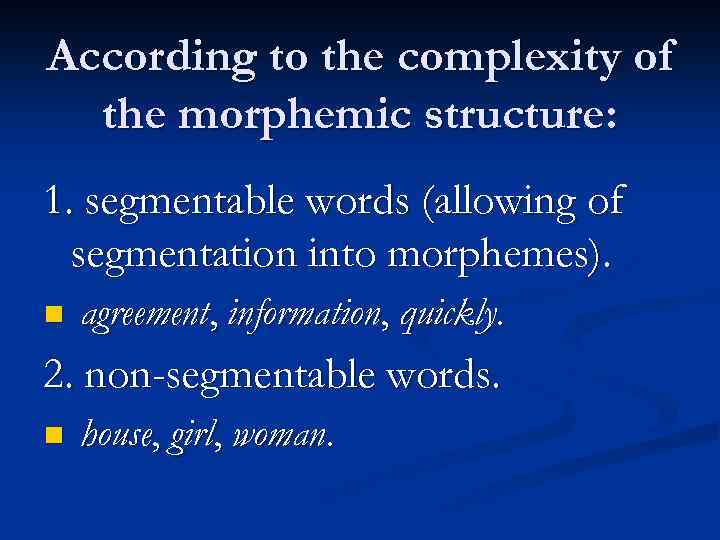

According to the complexity of the morphemic structure: 1. segmentable words (allowing of segmentation into morphemes). n agreement, information, quickly. 2. non-segmentable words. n house, girl, woman.

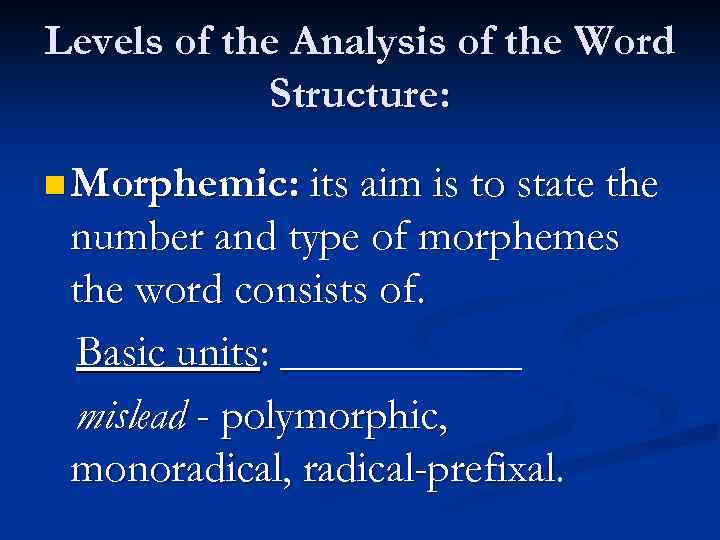

Levels of the Analysis of the Word Structure: n Morphemic: its aim is to state the number and type of morphemes the word consists of. Basic units: ______ mislead — polymorphic, monoradical, radical-prefixal.

n Derivational: its aim is to establish the correlations between different types of words and to establish a word’s derivational structure. Basic units: derivational bases, derivational affixes, derivational patterns.

The Morphemic Analysis: the operation of breaking a segmentable word into the constituent morphemes.

The method of Immediate and Ultimate constituents (the IC and UC method): to know how many _____ parts are there in a word.

At every stage the word is broken into 2 components (IC-s) unless we achieve units incapable of further division – the so-called ultimate constituents.

Friendliness: 1. is divided into the component friendly-, occurring in such words as friendly, friendly-looking, and the component ness- as in dark-ness, happy-ness. 2. is divided into friend- and -ly which are ultimate constituents.

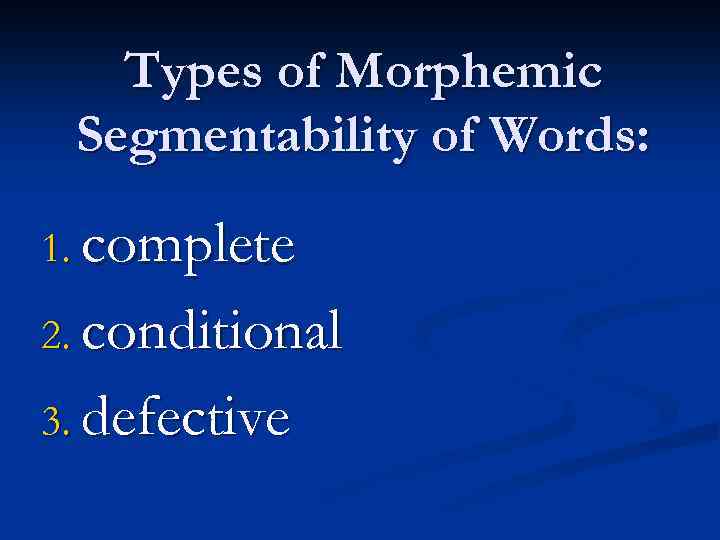

Types of Morphemic Segmentability of Words: 1. complete 2. conditional 3. defective

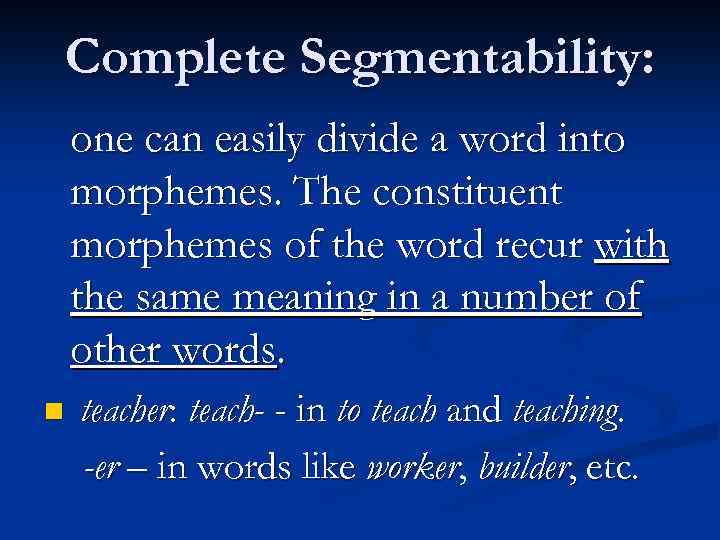

Complete Segmentability: one can easily divide a word into morphemes. The constituent morphemes of the word recur with the same meaning in a number of other words. n teacher: teach- — in to teach and teaching. -er – in words like worker, builder, etc.

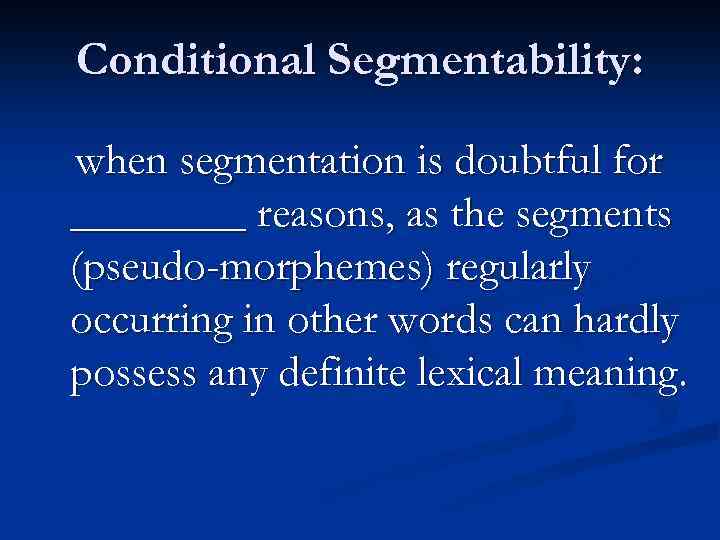

Conditional Segmentability: when segmentation is doubtful for ____ reasons, as the segments (pseudo-morphemes) regularly occurring in other words can hardly possess any definite lexical meaning.

n retain, detain, contain or receive, conceive, perceive: sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-], [kən-] seem to be singled out quite easily due to their recurrence in a number of words, but they have nothing in common with the phonetically identical morphemes like re-, de- as in words rewrite, re-organize, decode.

Defective Segmentability: when segmentation is doubtful for ______ reasons because one of the components (a unique morpheme) has a specific lexical meaning but seldom or never occurs in other words.

n streamlet, ringlet, leaflet: the morpheme -let has the denotational meaning of diminutiveness and is combined with the morphemes stream-, ring-, leaf-, each having a clear denotational meaning. n hamlet – the morpheme -let retains the same meaning of diminutiveness, but the soundcluster [hæm] does not occur in any English word with the meaning it has in the word hamlet.

Morphological analysis: + reveals the number of meaningful constituents in a word and their usual sequence. — does not reveal the way the word is constructed.

3. Derivative structure. Derivational analysis

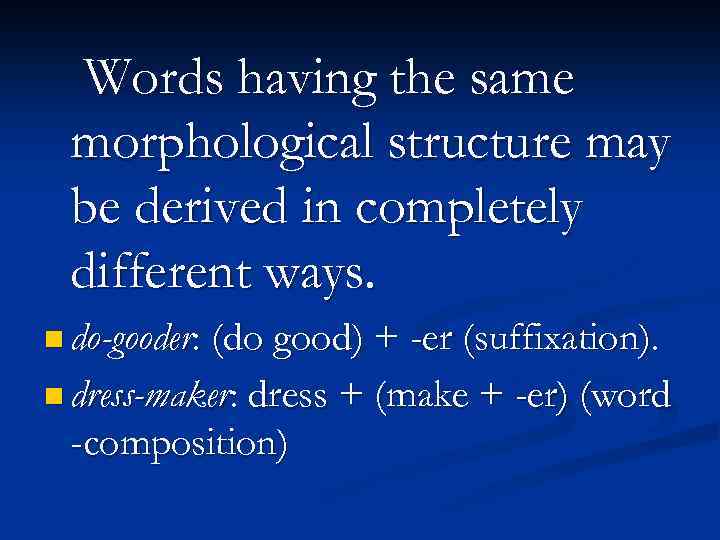

Words having the same morphological structure may be derived in completely different ways. n do-gooder: (do good) + -er (suffixation). n dress-maker: dress + (make + -er) (word -composition)

Derivatives: nare words depending on some other lexical items that motivate them structurally and semantically.

The basic elements of a derivative structure of a word: n a derivational base n a derivational affix n derivational pattern

A derivational base: n a unit to which derivational affixes are added. It is always monosemantic.

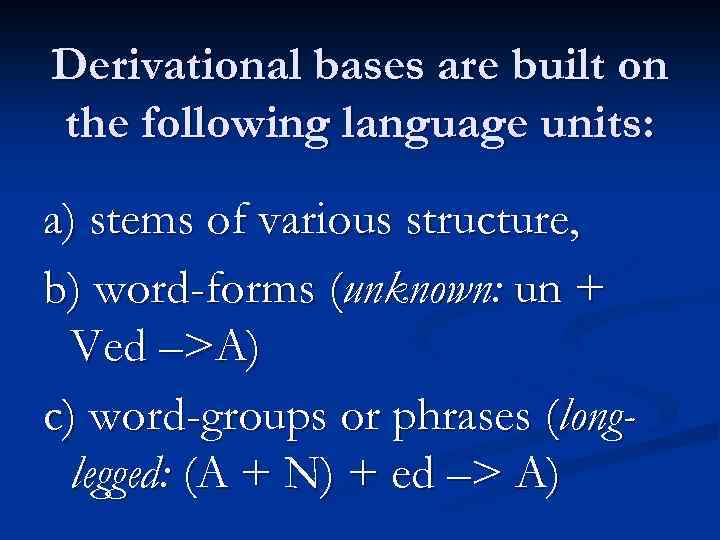

Derivational bases are built on the following language units: a) stems of various structure, b) word-forms (unknown: un + Ved –>A) c) word-groups or phrases (longlegged: (A + N) + ed –> A)

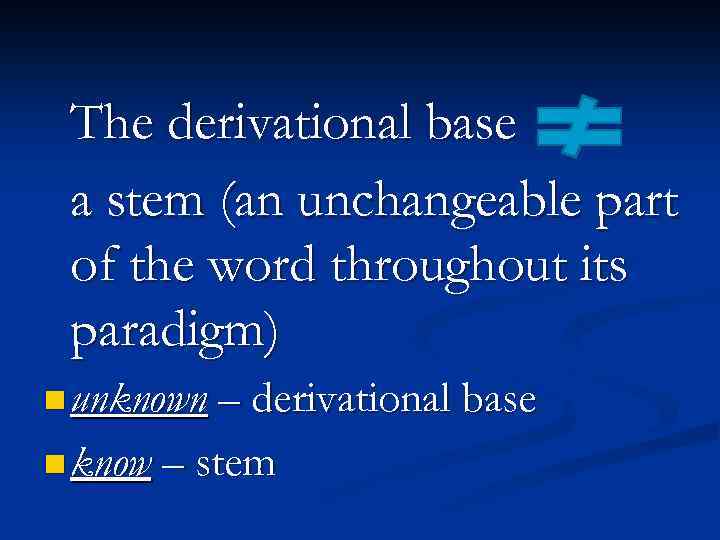

The derivational base a stem (an unchangeable part of the word throughout its paradigm) n unknown – derivational base n know – stem

A derivational affix is added to a derivational base.

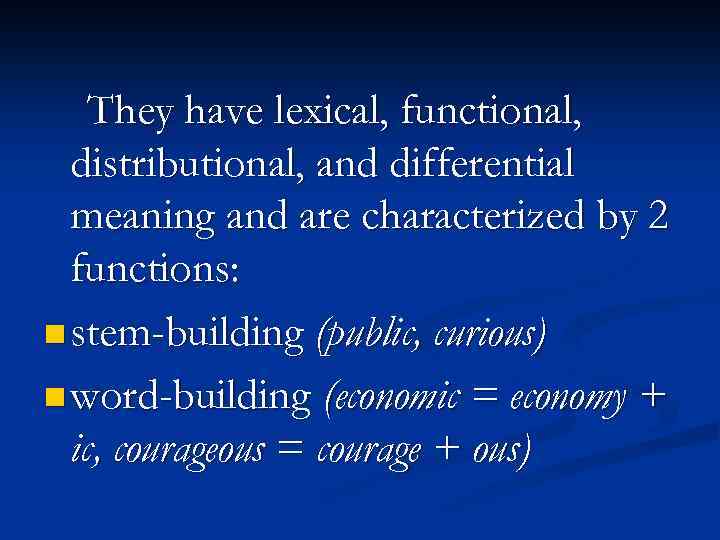

They have lexical, functional, distributional, and differential meaning and are characterized by 2 functions: n stem-building (public, curious) n word-building (economic = economy + ic, courageous = courage + ous)

A derivational pattern: a scheme of order and arrangement of the IC-s of the word. n v + -er =N (teach-teacher, build- builder) n re + v = V (re + write — rewrite)

4. Major types of wordformation: affixation, conversion, wordcomposition

In English there are three major types of word-formation: affixation, n zero derivation (conversion), n composition (compounding). n

Affixation. Prefixation. Classifications of prefixes. Suffixation. Classifications of suffixes. Productivity of suffixes.

Affixation has been one of the most productive ways of word-building throughout the history of English.

Affixation: n formation of new words by adding _____ affixes to different types of derivational bases.

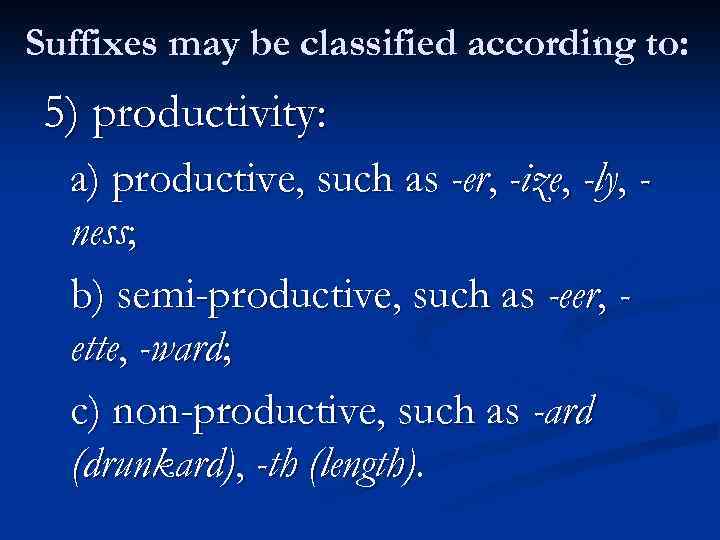

Affixes: n ______ (take part in deriving new words in the particular period of language development. To identify productive affixes one should look for them among neologisms). E. g. -er, -able. n ______. E. g. -hood, -ous.

The productivity of affixes their frequency of occurrence: there are some high-frequency affixes which are no longer used in word derivation (the adjective-forming suffixes -ful, -ly, etc. ).

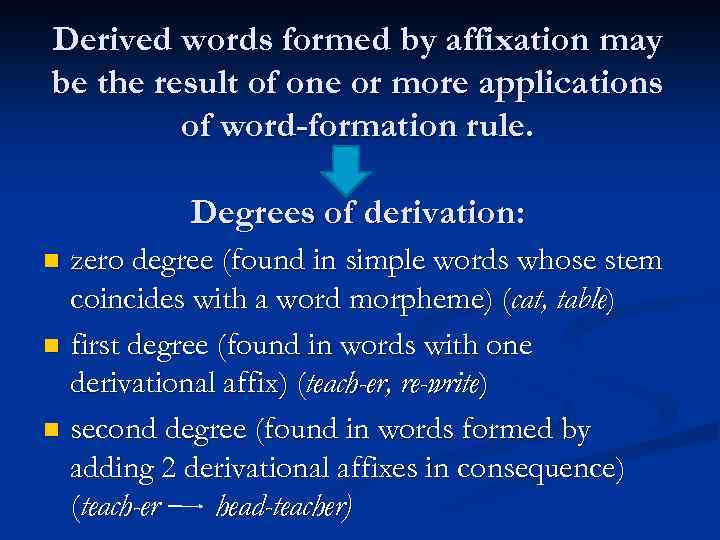

Derived words formed by affixation may be the result of one or more applications of word-formation rule. Degrees of derivation: zero degree (found in simple words whose stem coincides with a word morpheme) (cat, table) n first degree (found in words with one derivational affix) (teach-er, re-write) n second degree (found in words formed by adding 2 derivational affixes in consequence) (teach-er head-teacher) n

Affixation: n suffixation n prefixation

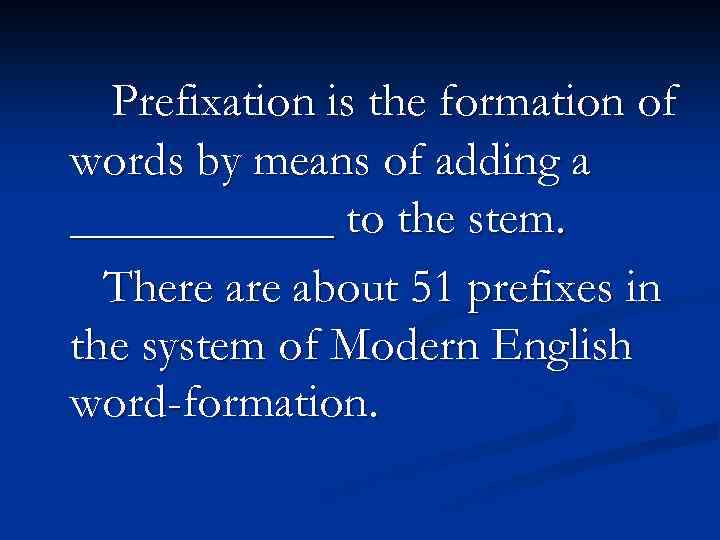

Prefixation is the formation of words by means of adding a ______ to the stem. There about 51 prefixes in the system of Modern English word-formation.

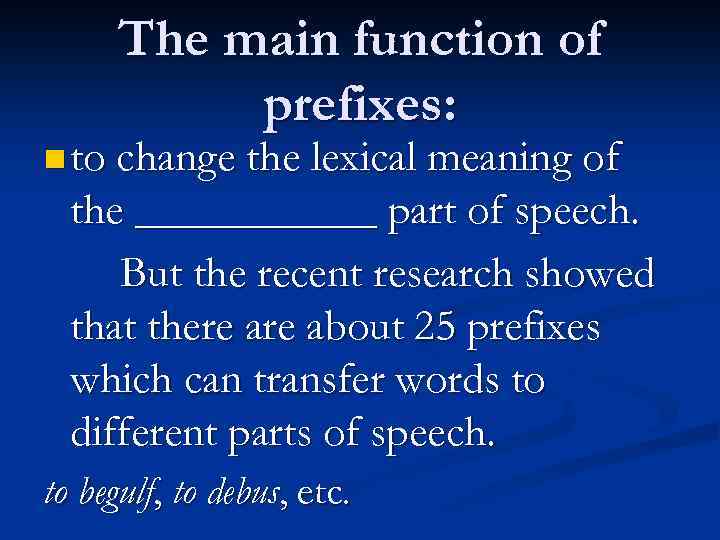

The main function of prefixes: n to change the lexical meaning of the ______ part of speech. But the recent research showed that there about 25 prefixes which can transfer words to different parts of speech. to begulf, to debus, etc.

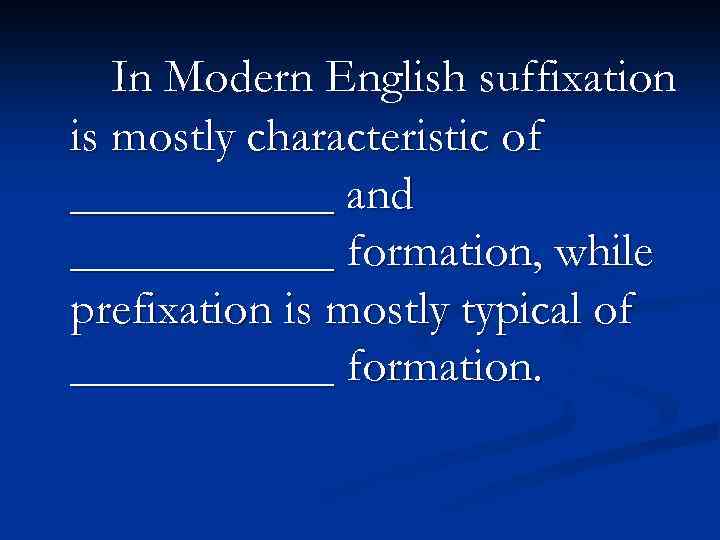

In Modern English suffixation is mostly characteristic of ______ and ______ formation, while prefixation is mostly typical of ______ formation.

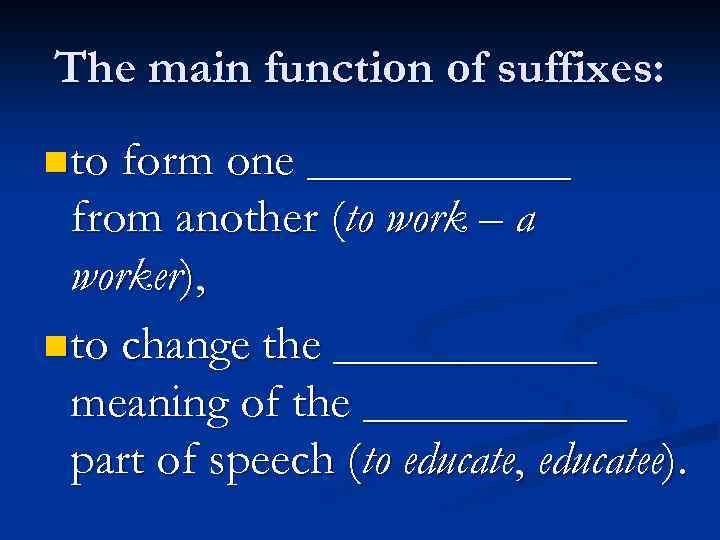

The main function of suffixes: n to form one ______ from another (to work – a worker), n to change the ______ meaning of the ______ part of speech (to educate, educatee).

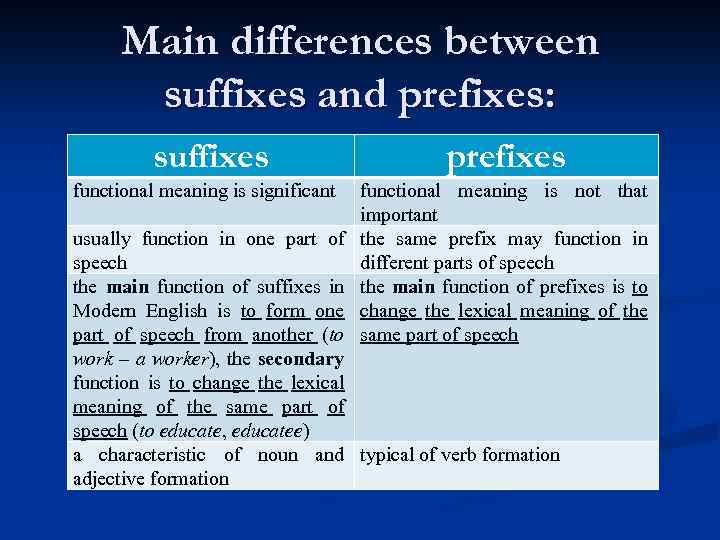

Main differences between suffixes and prefixes: suffixes functional meaning is significant prefixes functional meaning is not that important the same prefix may function in different parts of speech the main function of prefixes is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech usually function in one part of speech the main function of suffixes in Modern English is to form one part of speech from another (to work – a worker), the secondary function is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech (to educate, educatee) a characteristic of noun and typical of verb formation adjective formation

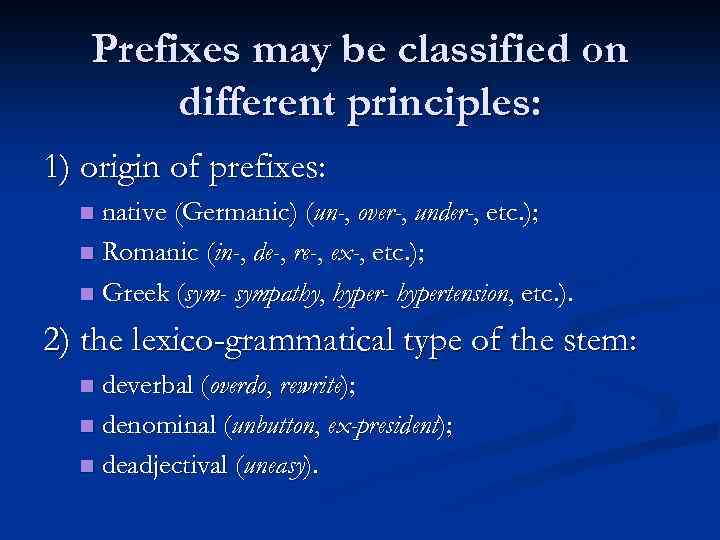

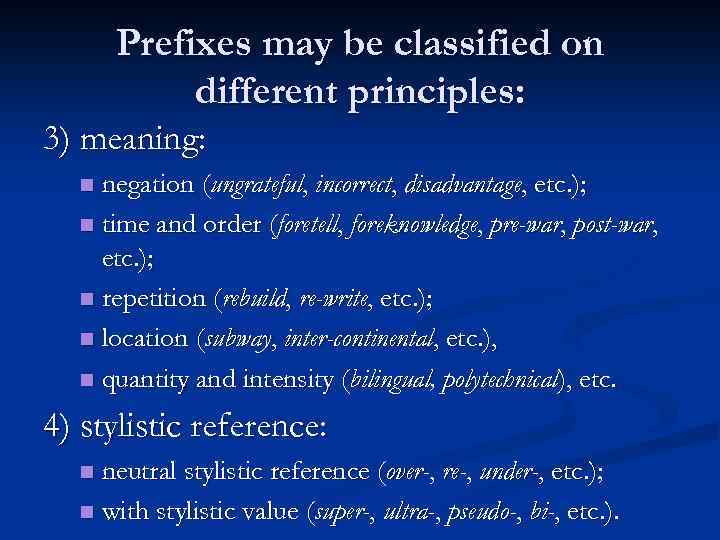

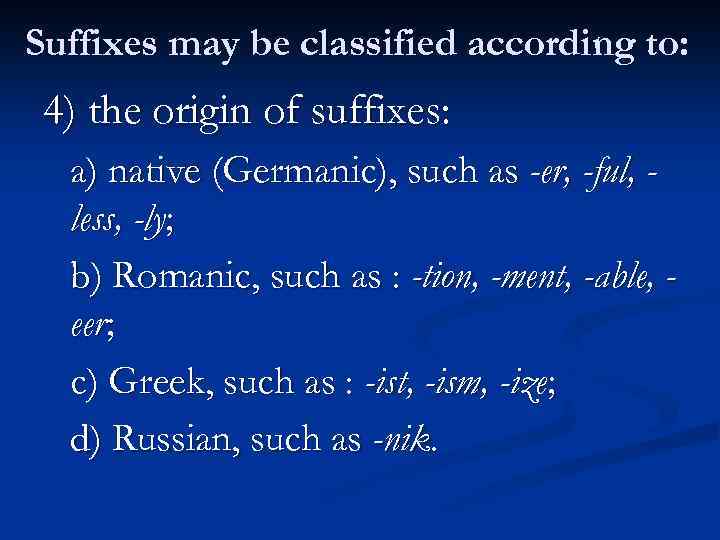

Prefixes may be classified on different principles: 1) origin of prefixes: native (Germanic) (un-, over-, under-, etc. ); n Romanic (in-, de-, re-, ex-, etc. ); n Greek (sym- sympathy, hyper- hypertension, etc. ). n 2) the lexico-grammatical type of the stem: deverbal (overdo, rewrite); n denominal (unbutton, ex-president); n deadjectival (uneasy). n

Prefixes may be classified on different principles: 3) meaning: negation (ungrateful, incorrect, disadvantage, etc. ); n time and order (foretell, foreknowledge, pre-war, post-war, etc. ); n repetition (rebuild, re-write, etc. ); n location (subway, inter-continental, etc. ), n quantity and intensity (bilingual, polytechnical), etc. n 4) stylistic reference: neutral stylistic reference (over-, re-, under-, etc. ); n with stylistic value (super-, ultra-, pseudo-, bi-, etc. ). n

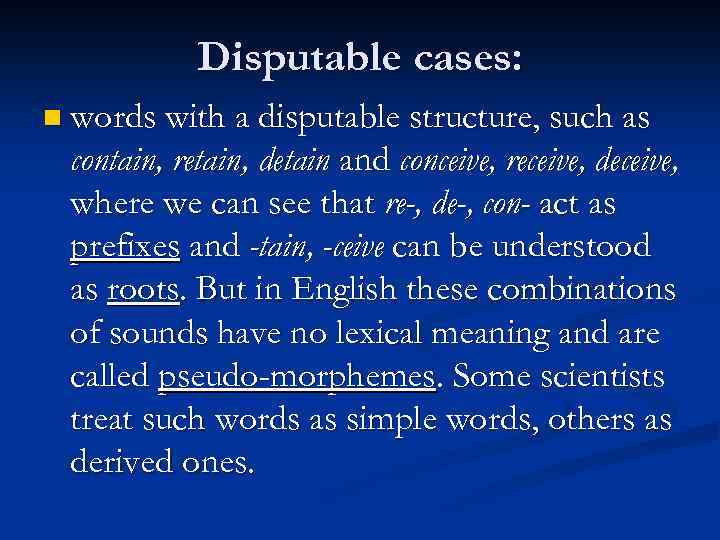

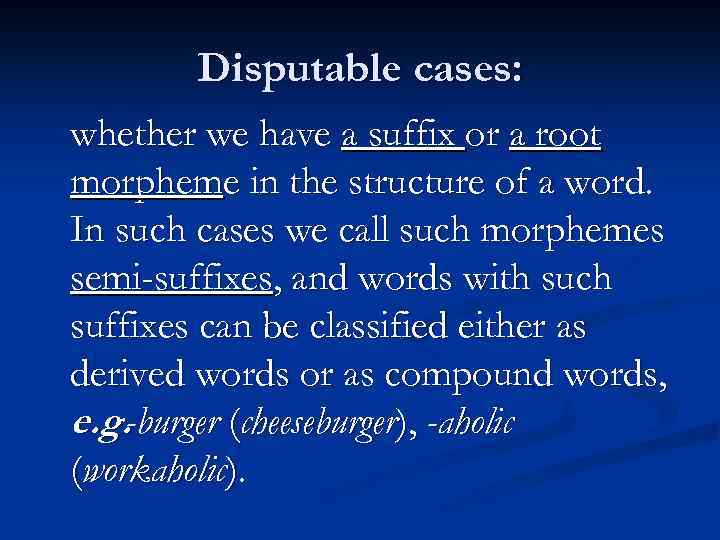

Disputable cases: n words with a disputable structure, such as contain, retain, detain and conceive, receive, deceive, where we can see that re-, de-, con- act as prefixes and -tain, -ceive can be understood as roots. But in English these combinations of sounds have no lexical meaning and are called pseudo-morphemes. Some scientists treat such words as simple words, others as derived ones.

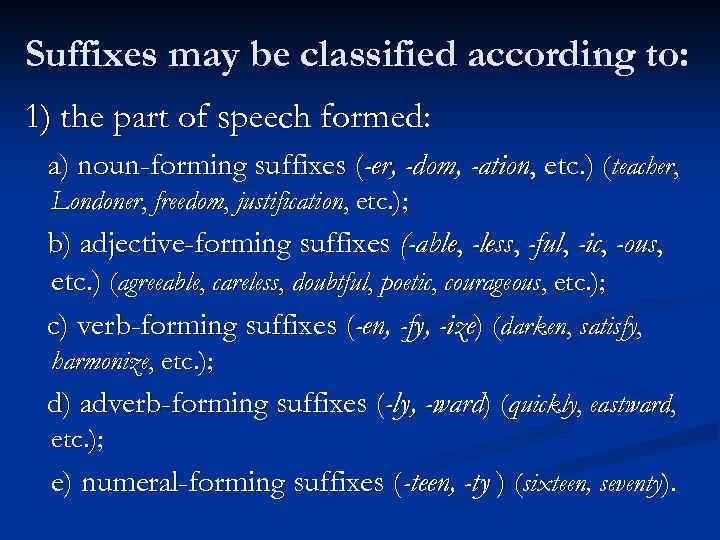

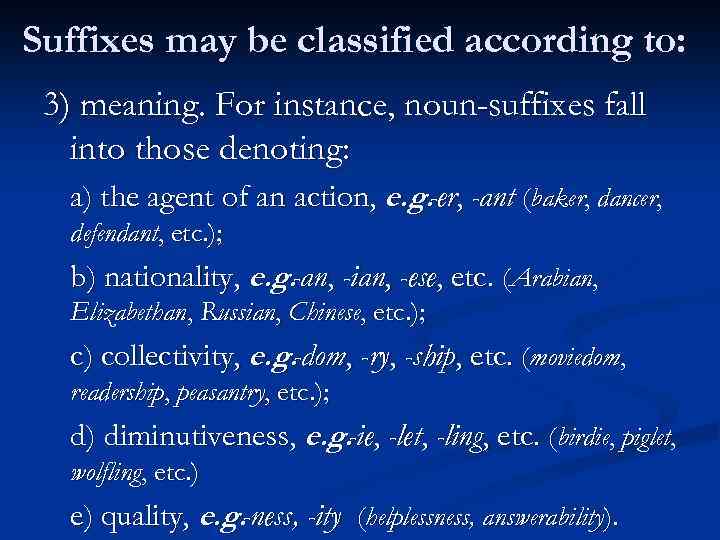

Suffixes may be classified according to: 1) the part of speech formed: a) noun-forming suffixes (-er, -dom, -ation, etc. ) (teacher, Londoner, freedom, justification, etc. ); b) adjective-forming suffixes (-able, -less, -ful, -ic, -ous, etc. ) (agreeable, careless, doubtful, poetic, courageous, etc. ); c) verb-forming suffixes (-en, -fy, -ize) (darken, satisfy, harmonize, etc. ); d) adverb-forming suffixes (-ly, -ward) (quickly, eastward, etc. ); e) numeral-forming suffixes (-teen, -ty ) (sixteen, seventy).

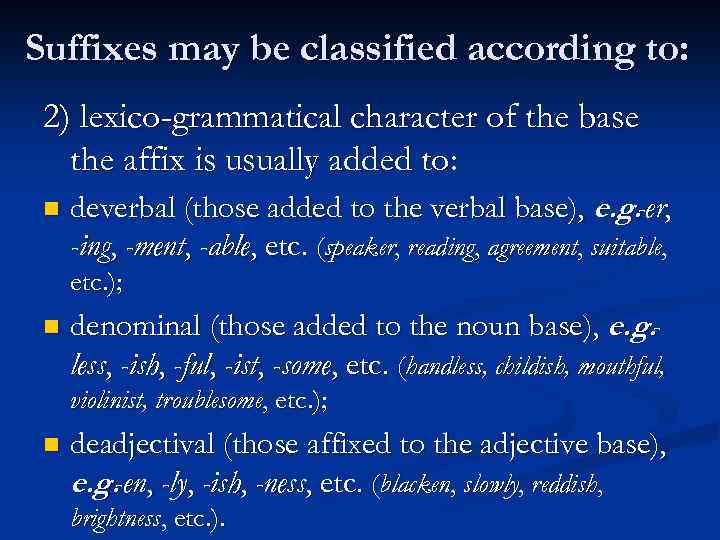

Suffixes may be classified according to: 2) lexico-grammatical character of the base the affix is usually added to: n deverbal (those added to the verbal base), e. g. -er, -ing, -ment, -able, etc. (speaker, reading, agreement, suitable, etc. ); n denominal (those added to the noun base), e. g. less, -ish, -ful, -ist, -some, etc. (handless, childish, mouthful, violinist, troublesome, etc. ); n deadjectival (those affixed to the adjective base), e. g. -en, -ly, -ish, -ness, etc. (blacken, slowly, reddish, brightness, etc. ).

Suffixes may be classified according to: 3) meaning. For instance, noun-suffixes fall into those denoting: a) the agent of an action, e. g. -er, -ant (baker, dancer, defendant, etc. ); b) nationality, e. g. -an, -ian, -ese, etc. (Arabian, Elizabethan, Russian, Chinese, etc. ); c) collectivity, e. g. -dom, -ry, -ship, etc. (moviedom, readership, peasantry, etc. ); d) diminutiveness, e. g. -ie, -let, -ling, etc. (birdie, piglet, wolfling, etc. ) e) quality, e. g. -ness, -ity (helplessness, answerability).

Suffixes may be classified according to: 4) the origin of suffixes: a) native (Germanic), such as -er, -ful, less, -ly; b) Romanic, such as : -tion, -ment, -able, eer; c) Greek, such as : -ist, -ism, -ize; d) Russian, such as -nik.

Suffixes may be classified according to: 5) productivity: a) productive, such as -er, -ize, -ly, ness; b) semi-productive, such as -eer, ette, -ward; c) non-productive, such as -ard (drunkard), -th (length).

Disputable cases: whether we have a suffix or a root morpheme in the structure of a word. In such cases we call such morphemes semi-suffixes, and words with such suffixes can be classified either as derived words or as compound words, e. g. -burger (cheeseburger), -aholic (workaholic).

Conversion. Typical semantic relations. Productivity of conversion.

The term conversion was first mentioned by H. _______ in 1891.

Conversion: n a morphological way of forming words when one part of speech is formed from another part of speech by changing its ______ The morphological paradigms of the word eye n as a noun: eye — eyes n as a verb: to eye, eyes, eyed, will eye

The clearest cases of conversion are observed between verbs and nouns, and this term is now mostly used in this narrow sense.

Conversion is very active both in nouns for verb formation: doctor to doctor, shop to shop in verbs to form nouns: to smile a smite, to offer an offer).

Typical semantic relations (verbs converted from nouns): a) names of _______ of a human body and _______ , _______ – verbs have instrumental meaning (to hammer, to rifle, to nail), b) verbs denote an action characteristic of the _______ denoted by the noun from which they have been converted (to crowd, to wolf, to ape),

Typical semantic relations (verbs converted from nouns): c) verbs denote acquisition, addition or deprivation if they are formed from nouns denoting an object (to fish, to dust, to paper), d) the name of a _______ – verbs denote the process of occupying the place or of putting smth. /smb. in it (to room, to house, to cage), e) the _______ denoted by the noun – verbs denote an action performed at the time (to winter, to week-end),

Typical semantic relations (verbs converted from nouns): f) the name of a _______ or occupation – verbs denote an activity typical of it (to nurse, to cook, to maid, to groom), g) the name of a _______ – verbs denote the act of putting smth. within the container (to can, to bottle, to pocket). h) the name of a _______ – verbs denote the process of taking it (to lunch, to supper).

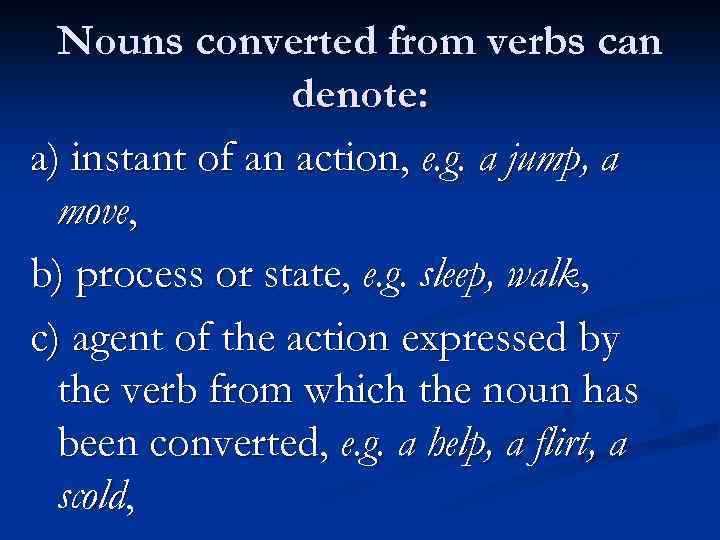

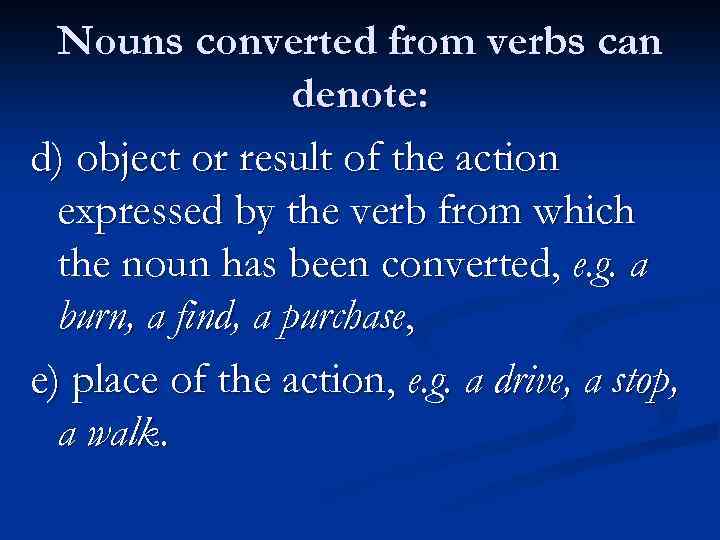

Nouns converted from verbs can denote: a) instant of an action, e. g. a jump, a move, b) process or state, e. g. sleep, walk, c) agent of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e. g. a help, a flirt, a scold,

Nouns converted from verbs can denote: d) object or result of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e. g. a burn, a find, a purchase, e) place of the action, e. g. a drive, a stop, a walk.

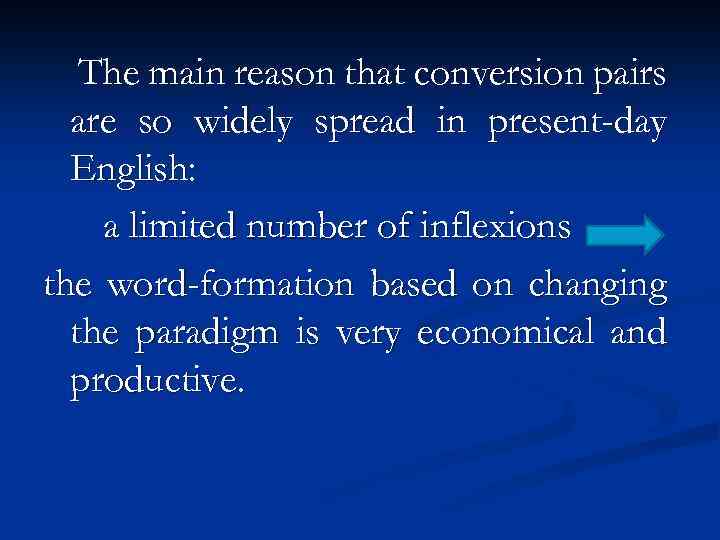

The main reason that conversion pairs are so widely spread in present-day English: a limited number of inflexions the word-formation based on changing the paradigm is very economical and productive.

Word-composition. Features of compoundwords. Classifications of compound-words.

Composition nthe way of word building when a word is formed by joining two or more _______ to form one word.

As English compounds consist of free forms, it is difficult to distinguish them from phrases.

Criteria of distinguishing compound words: 1) _______ (solid or hyphenated spelling), e. g. phrase-book, Sunday. 2) _______ (based on the position of stress). There is a tendency to put heavy stress on the 1 -st element (‘blackboard, ‘ice-cream). But this rule does not hold in some cases: with adjectives (new-‘born, easy-‘going) etc.

3) _______ (a compound is a combination forming a unit that expresses a single idea and that is not identical in meaning to the sum of the meanings of its components in a free phrase). 4) the unity of _____ and _____ functioning. Compounds are used in a sentence as one part of it and only one component changes grammatically, e. g. These girls are chatterboxes. «Chatter-boxes» is a predicative in the sentence and only the second component changes grammatically.

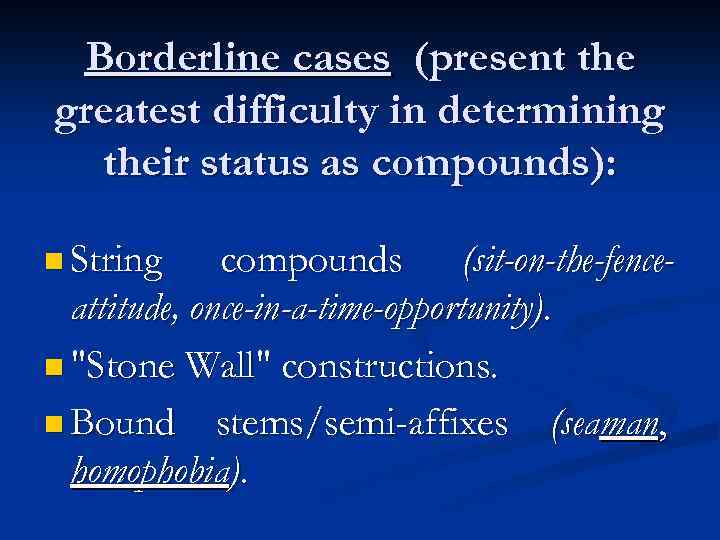

Borderline cases (present the greatest difficulty in determining their status as compounds): n String compounds (sit-on-the-fenceattitude, once-in-a-time-opportunity). n «Stone Wall» constructions. n Bound stems/semi-affixes (seaman, homophobia).

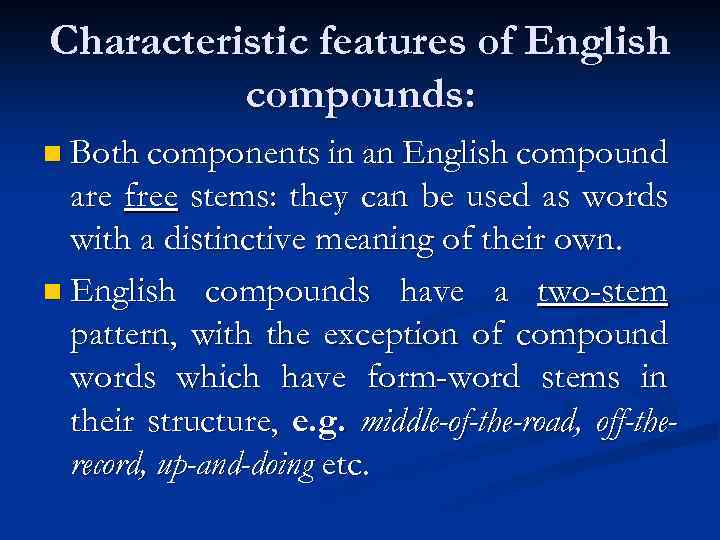

Characteristic features of English compounds: n Both components in an English compound are free stems: they can be used as words with a distinctive meaning of their own. n English compounds have a two-stem pattern, with the exception of compound words which have form-word stems in their structure, e. g. middle-of-the-road, off-therecord, up-and-doing etc.

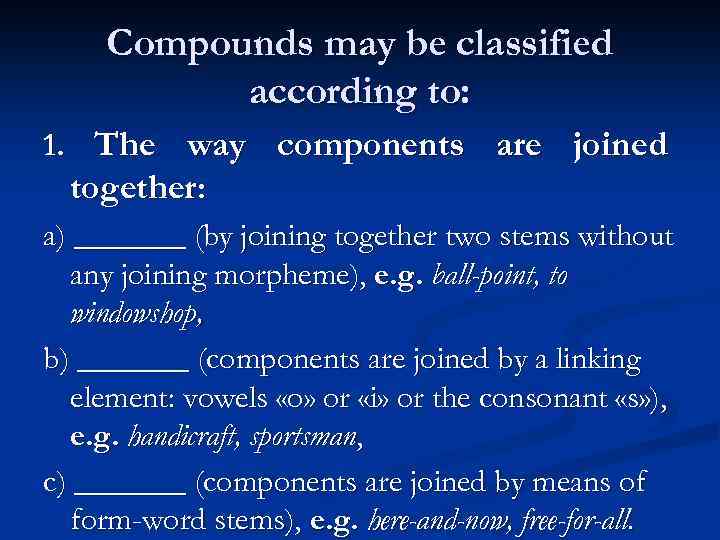

Compounds may be classified according to: 1. The way components are joined together: a) _______ (by joining together two stems without any joining morpheme), e. g. ball-point, to windowshop, b) _______ (components are joined by a linking element: vowels «o» or «i» or the consonant «s» ), e. g. handicraft, sportsman, c) _______ (components are joined by means of form-word stems), e. g. here-and-now, free-for-all.

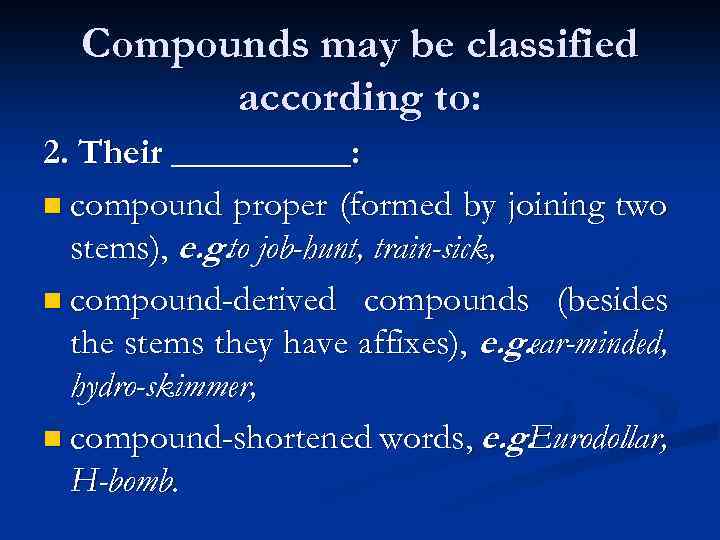

Compounds may be classified according to: 2. Their _____: n compound proper (formed by joining two stems), e. g. to job-hunt, train-sick, n compound-derived compounds (besides the stems they have affixes), e. g. ear-minded, hydro-skimmer, n compound-shortened words, e. g. Eurodollar, H-bomb.

Compounds may be classified according to: 3. Semantic relations: 1) _______ (the meaning of the whole is the sum total of the meanings of the components), e. g. music-lover, flower-bed 2) _______ , e. g. hotdog, wet-blanket

5. Secondary types of word-formation

_____ types of wordformation: n lexicalization, n sound-imitation, n reduplication, n back-formation, n sound and stress interchange, n shortening (abbreviation, acronymy, blends, clipping).

Besides major types of word-formation (affixation, composition and conversion) in English, there are some other types, which are less important for replenishment of vocabulary. Some of them (sound-interchange, stress shift and back-formation) were acting in the past and are more important for diachronic research of vocabulary. Such types as clipping, blending, and acronymy are very common in modern English.

Lexicalization: the process, when due to some semantic and syntactic reasons, the grammatical flexion in some word forms loses its _____ meaning and becomes isolated from the paradigm e. g. the plural of nouns like arms, colours of the words arm and colours. As the result these word forms (arms, colours) develop a different lexical meaning (arms = weapons and colours = flag) and become independent words. n

Sound-imitation: n the way of word-building when a word is formed by _______ different sounds. E. g. to whisper, to sneeze, to whistle, to buzz, to bark, to bubble.

Reduplication: n the way of word-formation within which new words are formed by _____ a stem, either without any phonetic changes or with a variation of the root-vowel or consonant. E. g. bye-bye, gee- gee, hush-hush, ping-pong, dilly-dally.

Back-formation: n the creation of new words by losing a _______ morpheme (babysitter to baby-sit, editor to edit, beggar to beg). It is opposite to suffixation, that is why it is called back-formation.

Sound-interchange n the creation of new words by changing the _____ (to breathe – breath, food – feed)

Stress-shift: n the process of forming new words by replacement of _______ from one syllable to another (‘import – to im’port, ‘record – to re’cord).

Types of Shortening: n substantivisation n acronyms and letter abbreviations n blends (сращения) n clippings (усечения)

Substantivisation: n is dropping of the final nominal member of a frequently used attributive word-group. The remaining adjective takes on the meaning and all syntactic functions of the noun and, in this way, develops into a new word. A number of nouns in English appeared in this way (documentary – a doc. film; finals – final examination; an editorial – an editorial article).

Abbreviation: na _____ form of a _____ word or a phrase used in a text in place of the whole for economy of space and effort.

Main types of shortenings: n _______ abbreviations (the result of shortening of words and word-groups only in written speech while orally the corresponding full forms are used. They are used for the economy of space and effort in writing), e. g. Mon — Monday, April, Mr. , Dr. n _______ abbreviations

Acronyms and letter abbreviations: Though the border-line between them is rather vague scholars make distinction between these 2 notions.

Letter abbreviations: n are mere replacements of longer phrases including names of well-known organizations, agencies, institutions, political parties, official offices. They are pronounced ______ and, as a rule, possess no linguistic forms proper to words (ITV = Independent Television; SST = Supersonic Transport)

Acronyms n are regular vocabulary units spoken as _______ (CLASS, yuppie). All acronyms, unlike letter abbreviations, perform the syntactic functions of ordinary words and can have grammatical inflexions. n Eg. : MP-MP’s-MPs

Acronyms may be formed in different ways: n from the initial letters or syllables of a phrase (NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization; UNO = United Nations Organization) n from the initial syllables of each word of a phrase (Interpol = international police)

Blends: n are words created when _______ and _______ segments of two words are joined together (smog = smoke + fog; brunch = breakfast + lunch).

Clipping: n is creation of new words by shortening a word of 2 or more _______ without changing its class membership (van = caravan, advantage (in tennis); dub = double; mike = microphone).

As a rule, lexical meanings of the clipped and the original word do not coincide. E. g. : Doc refers only to «sb. who practises medicine», while doctor denotes also «the higher degree given by a University, and a person who has received it» – Doctor of Philosophy, Doctor of Law).

Clippings fall into: n initial (van = advantage) n medial (specs = spectacles, maths = mathematics) n final (fan = fanatic)

Morphological Structure of Words

1.Types of Words: Monomorphic

Polymorphic

2.Morphemes: Types

DIVIDE THE FOLLOWING WORDS INTO MEANINGFUL PARTS

workers

pre-reading

loves

bicycles

classified

impossible

dresses

beautifully

OBJECTIVES

-

To know how to divide words into morphemes

-

To identify the different types of morphemes

-

To classify morphemes

GRAMMAR IS DIVIDED INTO MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX

-

Syntax –structure of sentences

-

Morphology –structure of words

-

Words

-

Words are composed of morphemes.

-

Words that consist of just one morpheme are monomorphic words.

-

Words that consist of more than one morpheme are polymorphic words

Morphemes are the smallest units of meaning -

Morphemes are classified according to different principles

-

Degree of independence: free or bound

-

Role they play in forming words: roots or affixes

-

Degree of independence

Free morphemes stand alone in the language. Ex. work -worker

write -writer

Bound morphemes are used exclusively with free or bound morphemes.

Ex. -er worker writer

leg- — legible

arrog- — arrogant

ROLE THEY PLAY IN FORMING WORDS

Root morphemes —

The root is the primary lexical unit of a word which carries semantic aspects of a word and cannot be reduced to smaller constituents.

It is the common element in a word family.

Roots can be free or bound

Most native English roots are free morphemes. Ex. read, eat, write

Most borrowed roots are bound

Arrog- -ance

Char- -ity

Leg- -ible

Toler- -able

Affixes

Affixes are always bound forms. Ex. -ful, -ly, -ity,

Affixes are classified into prefixes and suffixes.

Prefixes come before the base or root.

Ex. im- possible un- happy

-

Suffixes come after a base or root.

-

They may be inflectional or derivational.

Derivational morphemes

Change the meaning of a word or the part of speech or both. Derivational morphemes create new words.

Example: kind — kindness

friend — friendship

Inflectional morphemes

They can only be suffixes.

Example -s cats

-s reads

An inflectional morpheme creates a change in the function of a word. Ex. invited

English has only seven inflectional morphemes—plural, possessive -nouns

3rd.person singular, past tense, past participle, present participle -verbs

comparative , superlative — adjectives

allomorphs

Different phonetic forms or variations of a morpheme

/Z/ /S/ /IZ/

Plural dogs cats horses

3rd person reads talks dresses

eatable edible soluble

Jj is for Jottings 135. Morphemes.

There was a brief definition of morphemes in the article on learning vocabulary. Direct vocabulary instruction referred to using morphological knowledge to work out meanings of more complex words. So it’s probably time to go more thoroughly into morphemes and how important they really are. Knowledge of morphemes is important in phonics for both reading and spelling; and also in vocabulary and comprehension. That’s a broad sweep across both language and literacy.

A BASIC DEFINITION.

Here is a repeat of the definition given in the earlier article: Morphemes are the minimal units of words that have a meaning and cannot be subdivided further. An example of a free morpheme is “bad”, and an example of a bound morpheme is “ly.” It is bound because although it has meaning, it cannot stand alone.

So, morphology is the study of the internal structure of words. The word “morphology” is Greek, and is made up of two parts: “morph”, meaning “shape, form”; “-ology”, which means “the study of something”.

TYPES OF MORPHEMES.

- Free vs. Bound.

A morpheme can be either single words (free morphemes) or parts of words (bound morphemes). Thus a word consists of one or more morphemes.

A free morpheme can stand alone as a single word. Examples are:

picture

father

gentle.

A bound morpheme exists as only part of a word. Examples are:

-s as in dog+s;

-ed as in jump+ed;

un- as in un+happy;

mis- as in mis+fortune;

-er as in sing+er.

- Compound words.

When we join free morphemes together we make compound words. Examples are sunshine, eyeball, birthday, rainbow. Compound words make an easy introduction to the idea that words can have multiple parts.

- Inflectional vs. Derivational.

Morphemes can also be divided into inflectional or derivational morphemes.

This sounds tricky, but it really isn’t.

Inflectional Morphemes change what a word does in terms of grammar, but do not create a word. Let’s use the word jump as an example.

We have jump (base form); jumping (present progressive); jumped (past tense). The inflectional morphemes -ing and -ed are added to the base word jump, to indicate the tense of the word.

If a word has an inflectional morpheme, it is still the same word, with a few possible suffixes added. So if you looked up jump in the dictionary, then only the base word jump would get its own entry into the dictionary. Jumping and jumped are listed under jump, as they are inflections of the base word. Jumping and jumped do not get their own dictionary entry.

With an irregular past tense, such as ran (past tense of run), the past tense marker is not -ed, as usual. Instead, the past tense marker is a change in the vowel from ‘u’ to ‘a’. As always, English is a very complex language, and I’m jolly glad I didn’t have to learn it as a second language!

Derivational morphemes are different from inflectional morphemes, in that they do create (derive) a new word. And this new word gets its own entry in the dictionary. So derivational morphemes help us to create new words out of base words.

We will use the base word act as an example. We can create new words from act by derivational prefixes ( eg. re-, en-) and suffixes (eg. –or). Thus we have created three new words: re+act (react); en+act (enact); act-or (actor). Each of these new words has its own dictionary entry.

- Prefixes, Suffixes, and Roots/Bases.

We can divide morphemes into prefixes, suffixes and roots/bases.

- Prefixes are morphemes that attach to the front of a root/base word.

- Suffixes are morphemes that attach to the end of a root/base word, or to other suffixes.

- Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning.

- Generally, base words are free morphemes, which can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

- Whereas root words are bound morphemes that cannot stand by themselves (e.g. -ject as in subject/reject, and -volve as in evolve/revolve).

Most morphemes can be divided into:

- Anglo-Saxon (like re-, un-, -ness);

- Latin (like non-, ex-, -ion, -ify);

- Greek (like micro, photo, graph).

So morphemes can be very helpful for analysing unfamiliar words. For more on root words and analysis, check out the article on children or feet: using the right root.

BREAKING WORDS INTO MORPHEMES.

It is useful to break words into morphemes and, if you know the meaning of the some or all of them, you can unlock the meanings of difficult words. Here is an example: unreliability (“unable to be relied upon or trusted”).

We have un+rely+able+ity.

Un is a prefix with a negative meaning or not.

Rely is the base word meaning “depend upon with full trust or confidence”.

Able is a suffix meaning “capable of”.

Ity is a suffix referring to quality or condition (although I couldn’t have told you that one off the top of my head).

So even if the word unreliability were unfamiliar, by knowing the meanings of prefixes and suffixes and some base words, you can often deduce the meanings. And it’s fun being a word detective!

Indecisive: “Will I have a piece of pear from this bucket or not?” The morphemes are: in (not)+de(from)+cis (kill)+ive(denotes inclination). So if you are indecisive you have not killed off all options but one, so you have to choose between two or more.

SUGGESTIONS FOR MORPHEME ACTIVITIES.

Analysing the morphology of words is useful for explaining phonics patterns (graphemes) and spelling rules. This is in addition to discovering the meanings of unfamiliar words, as mentioned above. It also shows us how words are linked together. Recognising and analysing morphemes is also useful, therefore, for providing comprehension strategies. Activities can include:

- Sorting words by base or root words.

- Picking out prefixes and suffixes.

- Making new words by combining base words with one of a choice of several prefixes.

- Finding all the morphemes in multi-morphemic words (eg. unhappiness, indecisiveness, unstoppable, metamorphosis.)

- Give base words and prefixes/suffixes and see how many words students can build, and what meaning they might have. For example: Prefixes: un- de- pre- re- co- con-

Base Words: play help flex bend blue sad sat

Suffixes: -ful -ly -less -able/-ible -ing -ion -y -ish -ness –ment

As you can see, although we don’t hear the words “morpheme” or “morphology” very often, we are using them every time we speak or write. And knowing about morphemes and their meanings plays a very important part in reading, writing, spelling and language.

Check out the Facebook page: Aa is for Alpacas.

55

Bochkova

G.Sh.

A

COURSE IN ENGLISH GRAMMAR

Lecture

One

-

Grammar

as part of language. Grammar as a linguistic discipline. -

Parts

of grammar. Paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations of grammatical

units. -

The

main notions of grammar. Grammatical meaning, grammatical form.

Grammatical category.

1.

We should distinguish between language as an abstract system of signs

(meaningful units) and speech as the use of language in the process

of communication. Language and speech are interconnected. Language

functions in speech. Speech is the manifestation of language.

The main distinctions of

language and speech are:

-

language

is abstract while speech is concrete; -

language

is common, general for all the bearers while speech is individual; -

language

is stable, less changeable while speech tends to changes; -

language

is a closed system, its units are limited while speech tends to be

open and endless.

The system of language is

constituted by 3 subsystems: phonetics, vocabulary, grammar. The

three constituent parts of language are studied by the corresponding

linguistic disciplines: phonology, lexicology, grammar.

Grammar may be defined as a

system of word changing and other means of expressing relations of

word in the sentence.

Grammar

as a linguistic discipline may be practical (descriptive, normative)

or theoretical. Practical

grammar

describes the grammatical system of a given language.

Theoretical grammar

gives a scientific explanation of the nature and peculiarities of the

grammatical system of the language.

Modern English, as distinct

from Modern Russian, is a language of analytical structure. Relations

of words in the sentence are expressed mainly by the positions of

words or by special form-words. The main means of expressing

syntactic relations in Russian (a language of synthetic structure) is

the system of word changing.

2. Main units of grammar are a

word and a sentence. A word may be divided into morphemes, a sentence

may be divided into phrases (word- groups). A morpheme, a word, a

phrase and a sentence are units of different levels of language

structure. A unit of a higher level consists of one or more units of

a lower level.

Grammatical units enter into

two types of relations: in the language system (paradigmatic

relations) and in speech (syntagmatic relations).

In

the language system each unit is included into a set of connections

based on different properties. For example, word forms child,

children, child’s, children’s

have the same lexical meaning and have different grammatical

meanings. They constitute a lexeme.

Word-forms children, boys,

men, books have the same grammatical meaning and have different

lexical meanings. They constitute a grammeme (a categorical form, a

form class).

The

system of all grammemes (grammatical forms) of all lexemes (words) of

a given class constitutes a paradigm.

Syntagmatic

relations are the relations in an utterance: I

like children.

There

is an essential difference in the way lexical and grammatical

meanings exist in the language and occur in speech. Lexical meanings

can be found in a bunch only in a dictionary or in the memory of a

man, or, scientifically, in the lexical system of the language. In

actual speech a lexical morpheme displays only one meaning of the

bunch in each case and that meaning is singled out by the context or

the situation of speech (syntagmatically): He

runs fast. He runs a hotel.

The meanings of a grammatical

morpheme always come together in the word. They can be singled out

only relatively in contrast to the meanings of other grammatical

morphemes (paradigmatically).

Main grammatical units, a word

and a sentence, are studied by different sections of Grammar:

Morphology (Accidence) and Syntax. Morphology studies the structure,

forms and the classification of words. Syntax studies the structure,

forms and the classification of sentences. In other words, Morphology

studies paradigmatic relations of words; Syntax studies syntagmatic

relations of words and paradigmatic relations of sentences.

According to another approach

Morphology should study both paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations

of words. Syntax should study both paradigmatic and syntagmatic

relations of sentences.

Syntactic syntagmatics is a

relatively new field of study, reflecting the functional approach to

language, i.e. the description of connected speech, or discourse.

3. The basic notions of

grammar are the grammatical meaning, the grammatical form and the

grammatical category.

The

grammatical meaning is a general, abstract meaning which embraces

classes of words (ox –

oxen,

bush – bushes).

The grammatical meaning

depends on the lexical meaning and is connected with objective

reality indirectly, through the lexical meaning.

The

grammatical meaning is relative, it is revealed in relations of word

forms: put – puts.

The grammatical meaning is

obligatory. The grammatical meaning must be expressed if the speaker

wants to be understood.

The

grammatical meaning must have a grammatical form of expression

(inflexions, analytical forms, word-order, etc.). Compare the

word-forms reads, is

writing. Both forms

denote process, but only the second form expresses it grammatically.

The term form may be used in a

wide sense to denote all means of expressing grammatical meanings. It

may be also used in a narrow sense to denote means of expressing a

particular grammatical meaning (plural number, present tense, etc.).

Grammatical

elements are unities of meaning and form, content and expression. In

the language system there is no direct correspondence of meaning and

form. Two or more units of the plane of content (meaning) may

correspond to one unit of the plane of expression (polysemy,

homonymy) – bushes,

speaks,

man’s;

oxen,

spoken.

Two or more units of the plane of expression (form) may correspond to

one unit of the plane of content (synonymy) – books,

buses,

children,

feet, criteria, data,

nuclei.

-

In the system of language

grammatical elements are connected on the basis of similarity and

contrast.

Partially

similar elements, i.e. elements having common and distinctive

features, constitute oppositions: goes

– went, box – boxes, good – better – best.

Consider the opposition box – boxes. Members of the opposition

differ in form and have different grammatical meanings (singular and

plural). At the same time they express the same general meaning –

number.

The

unity of the general meaning and its particular manifestations, which

is revealed through the opposition of forms, is a grammatical

category. There may be

different definitions of the category laying stress either on its

notional or formal aspect. But the category exists only if there is

an opposition of at least two forms. If there is one form, there is

no category.

The minimal (two-member)

opposition is called binary.

Oppositions may be of three

main types:

-

privative. One member has a

certain distinctive feature. This member is called marked, or

strong (+). The other member is characterized by the absence of

this distinctive feature. This member is called unmarked, or weak

(-):

speak

– speaks +

-

equipollent. Both members of

the opposition are marked:

am+

— is+

-

gradual. Members of the

opposition differ by the degree of certain property:

good – better – best

Most grammatical oppositions

are privative.

The

marked (strong) member has a narrow and definite meaning. The

unmarked (weak) member has a wide, general meaning.

Grammatical

forms express meanings of different categories. The form goes denotes

present tense, 3rd

person, singular number, indicative mood, active voice, etc. These

meanings are revealed in different oppositions:

goes

– is going

goes

– went

goes

– has gone

But

grammatical forms cannot express different meanings of the same

category. So if a grammatical form has two or more meanings, they

belong to different categories.

In

certain contexts the difference between members of the opposition is

lost, the opposition is reduced to one member. Usually the weak

member acquires the meaning of the strong member: The

train starts at 8 p.m. tomorrow.

This kind of oppositional reduction is called neutralization.

On

the other hand, the strong member may be used in the context typical

for the weak member. This use is stylistically marked: He

is always complaining.

This kind of reduction is called transposition.

Grammatical

categories reflect phenomena of objective reality. Thus the category

of number in nouns reflects the essential properties of

noun-referents. Such categories may be called notional, or

referential. Other categories reflect peculiarities of the

grammatical structure of the language (number in verbs). Such

categories may be called formal, or relational.

Besides

grammatical, or inflexional categories, based on the oppositions of

forms, there are categories, based on the oppositions of classes of

words. Such categories are called lexico-grammatical, or selective.

Compare: стол

– доска

– окно;

большой

– большая

– большое.The

formal difference between members of a lexico-grammatical opposition

is shown syntagmatically: большой

стол.

Grammatical

categories may be influenced by the lexical meanings. Such categories

as number, case, voice strongly depend on the lexical meaning. They