Learning how to write in short form is a skill. It takes time, but it’s certainly doable. This article will look at some good choices for writing “and” in short form. It’s a common word, so the more options we can provide to avoid repeating it, the better!

How Can I Write “And” In Short Form?

There are a few great examples of “and” in the short form. Some of them, you might even be familiar with. Why not check out some of the best ones here:

- &

- N

- ‘N’

- +

- /

- Et

- Whatever you want

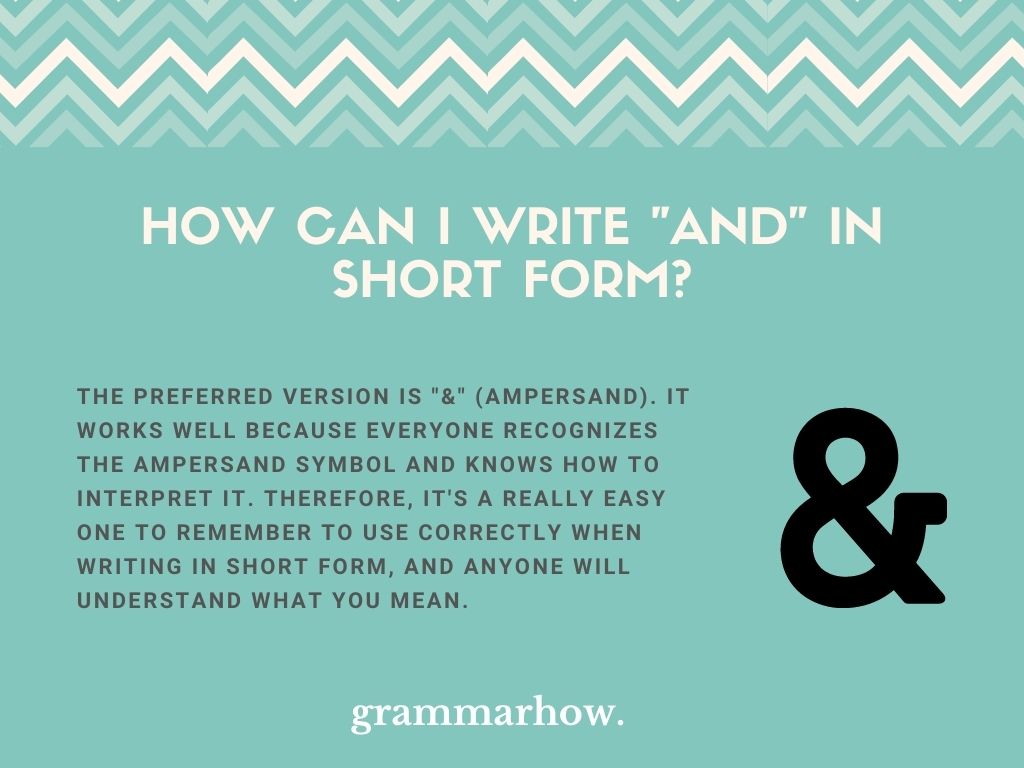

The preferred version is “&” (ampersand). It works well because everyone recognizes the ampersand symbol and knows how to interpret it. Therefore, it’s a really easy one to remember to use correctly when writing in short form, and anyone will understand what you mean.

&

“&” is the most universally recognized symbol for “and.” It works well when we want to write in the short form because everyone will be able to make sense of it. If you are planning on sharing your notes with others, this is your best bet to help them understand it.

It’s not always common for short-form notes to be shared. Usually, we are the only people who read them after we’ve taken the notes. However, if you are likely to share your notes, we recommend the ampersand because everyone knows that it means “and.”

Also, it’s a fairly quick symbol to create with a pen. While it might look a little wavy and difficult to create at first, it’s really simple to create it with one brush stroke.

You should test it by first doodling an ampersand and then writing “and” on a piece of paper. You will notice that the ampersand is a lot quicker to complete than “and,” which is what also makes it such a powerful choice for writing in the short form.

- Jack & Joseph will be arriving at 6 later tonight or tomorrow, depending on event finish time.

- Boss & supervisor want meeting at 3. Will attend office ready for that time.

- Friday & Saturday have booked time off. Will enjoy that time away from work.

N

“N” is a one-letter option we can use to replace “and.” We use “N” because it closely resembles the sound that you make when saying “and” (since the “N” is an important letter when pronouncing it).

Using one letter instead of three is a great way to shorten your writing. Since “N” and “and” are so similar, many short-form writers like to stick to this letter usage whenever they’re showing that multiple things should be put into the same group.

Remember, the whole point of the short form is to save you time when taking notes. It’s also to help you look back on your notes and remember what you were writing at the time.

Since “N” is already recognized as an “and” form, we can always rely on remembering what we meant. It’s a great short-form choice for this reason.

Also, it’s entirely up to the writer whether they want to capitalize the letter or not. Some people like to capitalize it to make it stand out, while others like to write it in the lower case because it’s quicker to write.

- Michelle N Rodrigo are up to no good again.

- Tom N Jenkins need to go to the store later tonight

- Cat n dog both out of food, so should get some later.

‘N’

“‘N’” is an extension of the one we explained previously. You might notice that the letter “N” is still used here. However, we’ve also included apostrophes on either side to really highlight that “N” is different from the rest of the sentence.

For some people, this inclusion of extra apostrophes is unnecessary. After all, the whole point of writing in the short form is that it should be quicker and easier to write.

‘N’ and “and” have the same amount of characters (three), so there isn’t anything that shows that ‘N’ will be quicker. However, it’s a stylistic choice. If you like to include the apostrophes to get it to stand out, there should be no reason why you can’t.

- Rock ‘n’ roll date underway.

- Friday ‘n’ Tuesday booked in for spa day.

- Football ‘n’ hockey nights have been set to record.

+

“+” is one of the most popular short-form choices for replacing “and.” Many people use the plus sign whenever they can because it’s one of the more obvious ways to show that two or more things should be grouped together.

The symbol originates from mathematical equations. You are probably already familiar with using plus signs to add things up. Well, the same idea applies when you write plus signs in the short form.

However, this time, instead of adding numbers together, you’re adding words, people, or things. The plus sign helps to group those things up into values that matter and allows you to refer back to your short-form when needed.

The best part about writing in the short form is that you are typically the only person who needs to read it. As we’ve already stated, as long as you know what you’re using the symbols for, there’s no reason why you can’t choose whatever one you want.

- Company director + chair want meeting with big boss on Friday.

- Friday + Monday need to be in office to make sure ready for the presentation.

- Interview + date on same day, so can recycle the clothes you wear for both occasions.

/

Next, we want to go over the slash. It’s not one of the most common options, but we think it’s still beneficial. Some short-form writers swear by the slash, which is why we included it.

“/” allows us to break up two different objects in a sentence. While some people might think the “/” means “or,” others like to use it as both “and” and “or,” depending on the context.

If you’re writing short form that you know other people will be reading, perhaps it’s best to avoid using the forward-slash symbol. However, if you are the only person reading your short form and you know what the slash is for, you can use it to replace “and.”

Since many people only write in the short form for their own sakes (i.e. to help them take notes of a class or presentation), they are the only people who need to understand what they’ve written. That’s why slashes work well, so long as you’re the audience.

If you ever show your short-form notes to other people, you might cause a bit of confusion.

- Steve / Marcus wanted to have a holiday in the Spring.

- Pythag / Newton both have designed something I’m supposed to know about in school today.

- Teachers / students want to gather in the playground to have a soccer match for lunchtime.

Et

We want to touch on “et.” It’s not the best option, which is why we put it last. However, some people like to use it.

“Et” is the Latin form of “and.” It’s commonly seen in other Latin phrases like “et al.,” but we rarely use it as the short form of “and.” However, some people like to use Latin forms like this (and it is still one letter shorter than “and”).

The idea of writing in short form is to make it quicker to write. “Et” is a much quicker word to write down than “and.” In fact, you should give it a try on a piece of paper in front of you.

Since short form developed from notepads, it is much more common to write with a pen, and “et” is much quicker to complete than “and.”

While some people might find “et” to be pretentious because of its Latin roots, there’s nothing wrong with using it if you like it. Some people simply do not like to use symbols.

- Tom et Callie will be coming to party tonight at 3.

- He et she will be there. Make sure there is room for both to arrive.

- They et co. have decided to make it a gathering for the masses.

Whatever You Want

Okay, this last one is a bit outlandish, but stick with us. Since most people write in short form to help them take notes, they tend to be the only people who will read it.

Therefore, you can technically use whatever symbol, letter, or word you want to replace “and.” As long as it’s shorter than “and,” and you know what it means when you read it back, you can use anything.

The whole point of the short form is to allow you to look back on your notes and decipher them when it matters. It’s wise to keep the same letter, symbol, or word throughout your short-form writing if you’re going to make up your own.

You might end up confusing yourself more if you have multiple different symbols that all mean the same thing. So, if you’re going to use whatever you want to use, make sure it stays consistent at the very least!

You may also like: When Should I Use “&” vs. “And”? Easy Ampersand Guide

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here.

Lecture №3. Productive and Non-productive Ways of Word-formation in Modern English

Productivity is the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are readily understood by the speakers of language. The most important and the most productive ways of word-formation are affixation, conversion, word-composition and abbreviation (contraction). In the course of time the productivity of this or that way of word-formation may change. Sound interchange or gradation (blood-to bleed, to abide-abode, to strike-stroke) was a productive way of word building in old English and is important for a diachronic study of the English language. It has lost its productivity in Modern English and no new word can be coined by means of sound gradation. Affixation on the contrary was productive in Old English and is still one of the most productive ways of word building in Modern English.

WORDBUILDING

Word-building is one of the main ways of enriching vocabulary. There are four main ways of word-building in modern English: affixation, composition, conversion, abbreviation. There are also secondary ways of word-building: sound interchange, stress interchange, sound imitation, blends, back formation.

AFFIXATION

Affixation is one of the most productive ways of word-building throughout the history of English. It consists in adding an affix to the stem of a definite part of speech. Affixation is divided into suffixation and prefixation.

Suffixation

The main function of suffixes in Modern English is to form one part of speech from another, the secondary function is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech. (e.g. «educate» is a verb, «educator» is a noun, and music» is a noun, «musical» is also a noun or an adjective). There are different classifications of suffixes :

1. Part-of-speech classification. Suffixes which can form different parts of speech are given here :

a) noun-forming suffixes, such as: —er (criticizer), —dom (officialdom), —ism (ageism),

b) adjective-forming suffixes, such as: —able (breathable), less (symptomless), —ous (prestigious),

c) verb-forming suffixes, such as —ize (computerize) , —ify (minify),

d) adverb-forming suffixes , such as : —ly (singly), —ward (tableward),

e) numeral-forming suffixes, such as —teen (sixteen), —ty (seventy).

2. Semantic classification. Suffixes changing the lexical meaning of the stem can be subdivided into groups, e.g. noun-forming suffixes can denote:

a) the agent of the action, e.g. —er (experimenter), —ist (taxist), -ent (student),

b) nationality, e.g. —ian (Russian), —ese (Japanese), —ish (English),

c) collectivity, e.g. —dom (moviedom), —ry (peasantry, —ship (readership), —ati (literati),

d) diminutiveness, e.g. —ie (horsie), —let (booklet), —ling (gooseling), —ette (kitchenette),

e) quality, e.g. —ness (copelessness), —ity (answerability).

3. Lexico—grammatical character of the stem. Suffixes which can be added to certain groups of stems are subdivided into:

a) suffixes added to verbal stems, such as: —er (commuter), —ing (suffering), — able (flyable), —ment (involvement), —ation (computerization),

b) suffixes added to noun stems, such as: —less (smogless), —ful (roomful), —ism (adventurism), —ster (pollster), —nik (filmnik), —ish (childish),

c) suffixes added to adjective stems, such as: —en (weaken), —ly (pinkly), —ish (longish), —ness (clannishness).

4. Origin of suffixes. Here we can point out the following groups:

a) native (Germanic), such as —er,-ful, —less, —ly.

b) Romanic, such as : —tion, —ment, —able, —eer.

c) Greek, such as : —ist, —ism, -ize.

d) Russian, such as —nik.

5. Productivity. Here we can point out the following groups:

a) productive, such as: —er, —ize, —ly, —ness.

b) semi-productive, such as: —eer, —ette, —ward.

c) non-productive , such as: —ard (drunkard), —th (length).

Suffixes can be polysemantic, such as: —er can form nouns with the following meanings: agent, doer of the action expressed by the stem (speaker), profession, occupation (teacher), a device, a tool (transmitter). While speaking about suffixes we should also mention compound suffixes which are added to the stem at the same time, such as —ably, —ibly, (terribly, reasonably), —ation (adaptation from adapt). There are also disputable cases whether we have a suffix or a root morpheme in the structure of a word, in such cases we call such morphemes semi-suffixes, and words with such suffixes can be classified either as derived words or as compound words, e.g. —gate (Irangate), —burger (cheeseburger), —aholic (workaholic) etc.

Prefixation

Prefixation is the formation of words by means of adding a prefix to the stem. In English it is characteristic for forming verbs. Prefixes are more independent than suffixes. Prefixes can be classified according to the nature of words in which they are used: prefixes used in notional words and prefixes used in functional words. Prefixes used in notional words are proper prefixes which are bound morphemes, e.g. un— (unhappy). Prefixes used in functional words are semi-bound morphemes because they are met in the language as words, e.g. over— (overhead) (cf. over the table). The main function of prefixes in English is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech. But the recent research showed that about twenty-five prefixes in Modern English form one part of speech from another (bebutton, interfamily, postcollege etc).

Prefixes can be classified according to different principles:

1. Semantic classification:

a) prefixes of negative meaning, such as: in— (invaluable), non— (nonformals), un— (unfree) etc,

b) prefixes denoting repetition or reversal actions, such as: de— (decolonize), re— (revegetation), dis— (disconnect),

c) prefixes denoting time, space, degree relations, such as: inter— (interplanetary) , hyper— (hypertension), ex— (ex-student), pre— (pre-election), over— (overdrugging) etc.

2. Origin of prefixes:

a) native (Germanic), such as: un-, over-, under— etc.

b) Romanic, such as: in-, de-, ex-, re— etc.

c) Greek, such as: sym-, hyper— etc.

When we analyze such words as adverb, accompany where we can find the root of the word (verb, company) we may treat ad-, ac— as prefixes though they were never used as prefixes to form new words in English and were borrowed from Romanic languages together with words. In such cases we can treat them as derived words. But some scientists treat them as simple words. Another group of words with a disputable structure are such as: contain, retain, detain and conceive, receive, deceive where we can see that re-, de-, con— act as prefixes and —tain, —ceive can be understood as roots. But in English these combinations of sounds have no lexical meaning and are called pseudo-morphemes. Some scientists treat such words as simple words, others as derived ones. There are some prefixes which can be treated as root morphemes by some scientists, e.g. after— in the word afternoon. American lexicographers working on Webster dictionaries treat such words as compound words. British lexicographers treat such words as derived ones.

COMPOSITION

Composition is the way of word building when a word is formed by joining two or more stems to form one word. The structural unity of a compound word depends upon: a) the unity of stress, b) solid or hyphеnated spelling, c) semantic unity, d) unity of morphological and syntactical functioning. These are characteristic features of compound words in all languages. For English compounds some of these factors are not very reliable. As a rule English compounds have one uniting stress (usually on the first component), e.g. hard-cover, best—seller. We can also have a double stress in an English compound, with the main stress on the first component and with a secondary stress on the second component, e.g. blood—vessel. The third pattern of stresses is two level stresses, e.g. snow—white, sky—blue. The third pattern is easily mixed up with word-groups unless they have solid or hyphеnated spelling.

Spelling in English compounds is not very reliable as well because they can have different spelling even in the same text, e.g. war—ship, blood—vessel can be spelt through a hyphen and also with a break, insofar, underfoot can be spelt solidly and with a break. All the more so that there has appeared in Modern English a special type of compound words which are called block compounds, they have one uniting stress but are spelt with a break, e.g. air piracy, cargo module, coin change, penguin suit etc. The semantic unity of a compound word is often very strong. In such cases we have idiomatic compounds where the meaning of the whole is not a sum of meanings of its components, e.g. to ghostwrite, skinhead, brain—drain etc. In nonidiomatic compounds semantic unity is not strong, e. g., airbus, to bloodtransfuse, astrodynamics etc.

English compounds have the unity of morphological and syntactical functioning. They are used in a sentence as one part of it and only one component changes grammatically, e.g. These girls are chatter-boxes. «Chatter-boxes» is a predicative in the sentence and only the second component changes grammatically. There are two characteristic features of English compounds:

a) Both components in an English compound are free stems, that is they can be used as words with a distinctive meaning of their own. The sound pattern will be the same except for the stresses, e.g. «a green-house» and «a green house». Whereas for example in Russian compounds the stems are bound morphemes, as a rule.

b) English compounds have a two-stem pattern, with the exception of compound words which have form-word stems in their structure, e.g. middle-of-the-road, off—the—record, up—and—doing etc. The two-stem pattern distinguishes English compounds from German ones.

WAYS OF FORMING COMPOUND WORDS

Compound words in English can be formed not only by means of composition but also by means of:

a) reduplication, e.g. too—too, and also by means of reduplication combined with sound interchange , e.g. rope-ripe,

b) conversion from word-groups, e.g. to micky—mouse, can—do, makeup etc,

c) back formation from compound nouns or word-groups, e.g. to bloodtransfuse, to fingerprint etc ,

d) analogy, e.g. lie—in (on the analogy with sit-in) and also phone—in, brawn—drain (on the analogy with brain—drain) etc.

CLASSIFICATIONS OF ENGLISH COMPOUNDS

1. According to the parts of speech compounds are subdivided into:

a) nouns, such as: baby-moon, globe-trotter,

b) adjectives, such as : free-for-all, power-happy,

c) verbs, such as : to honey-moon, to baby-sit, to henpeck,

d) adverbs, such as: downdeep, headfirst,

e) prepositions, such as: into, within,

f) numerals, such as : fifty—five.

2. According to the way components are joined together compounds are divided into: a) neutral, which are formed by joining together two stems without any joining morpheme, e.g. ball—point, to windowshop,

b) morphological where components are joined by a linking element: vowels «o» or «i» or the consonant «s», e.g. («astrospace», «handicraft», «sportsman»),

c) syntactical where the components are joined by means of form-word stems, e.g. here-and-now, free-for-all, do-or-die.

3. According to their structure compounds are subdivided into:

a) compound words proper which consist of two stems, e.g. to job-hunt, train-sick, go-go, tip-top,

b) derivational compounds, where besides the stems we have affixes, e.g. ear—minded, hydro-skimmer,

c) compound words consisting of three or more stems, e.g. cornflower—blue, eggshell—thin, singer—songwriter,

d) compound-shortened words, e.g. boatel, VJ—day, motocross, intervision, Eurodollar, Camford.

4. According to the relations between the components compound words are subdivided into:

a) subordinative compounds where one of the components is the semantic and the structural centre and the second component is subordinate; these subordinative relations can be different: with comparative relations, e.g. honey—sweet, eggshell—thin, with limiting relations, e.g. breast—high, knee—deep, with emphatic relations, e.g. dog—cheap, with objective relations, e.g. gold—rich, with cause relations, e.g. love—sick, with space relations, e.g. top—heavy, with time relations, e.g. spring—fresh, with subjective relations, e.g. foot—sore etc

b) coordinative compounds where both components are semantically independent. Here belong such compounds when one person (object) has two functions, e.g. secretary-stenographer, woman-doctor, Oxbridge etc. Such compounds are called additive. This group includes also compounds formed by means of reduplication, e.g. fifty-fifty, no-no, and also compounds formed with the help of rhythmic stems (reduplication combined with sound interchange) e.g. criss-cross, walkie-talkie.

5. According to the order of the components compounds are divided into compounds with direct order, e.g. kill—joy, and compounds with indirect order, e.g. nuclear—free, rope—ripe.

CONVERSION

Conversion is a characteristic feature of the English word-building system. It is also called affixless derivation or zero-suffixation. The term «conversion» first appeared in the book by Henry Sweet «New English Grammar» in 1891. Conversion is treated differently by different scientists, e.g. prof. A.I. Smirntitsky treats conversion as a morphological way of forming words when one part of speech is formed from another part of speech by changing its paradigm, e.g. to form the verb «to dial» from the noun «dial» we change the paradigm of the noun (a dial, dials) for the paradigm of a regular verb (I dial, he dials, dialed, dialing). A. Marchand in his book «The Categories and Types of Present-day English» treats conversion as a morphological-syntactical word-building because we have not only the change of the paradigm, but also the change of the syntactic function, e.g. I need some good paper for my room. (The noun «paper» is an object in the sentence). I paper my room every year. (The verb «paper» is the predicate in the sentence). Conversion is the main way of forming verbs in Modern English. Verbs can be formed from nouns of different semantic groups and have different meanings because of that, e.g.:

a) verbs have instrumental meaning if they are formed from nouns denoting parts of a human body e.g. to eye, to finger, to elbow, to shoulder etc. They have instrumental meaning if they are formed from nouns denoting tools, machines, instruments, weapons, e.g. to hammer, to machine-gun, to rifle, to nail,

b) verbs can denote an action characteristic of the living being denoted by the noun from which they have been converted, e.g. to crowd, to wolf, to ape,

c) verbs can denote acquisition, addition or deprivation if they are formed from nouns denoting an object, e.g. to fish, to dust, to peel, to paper,

d) verbs can denote an action performed at the place denoted by the noun from which they have been converted, e.g. to park, to garage, to bottle, to corner, to pocket,

e) verbs can denote an action performed at the time denoted by the noun from which they have been converted e.g. to winter, to week-end.

Verbs can be also converted from adjectives, in such cases they denote the change of the state, e.g. to tame (to become or make tame), to clean, to slim etc.

Nouns can also be formed by means of conversion from verbs. Converted nouns can denote: a) instant of an action e.g. a jump, a move,

b) process or state e.g. sleep, walk,

c) agent of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a help, a flirt, a scold,

d) object or result of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a burn, a find, a purchase,

e) place of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a drive, a stop, a walk.

Many nouns converted from verbs can be used only in the Singular form and denote momentaneous actions. In such cases we have partial conversion. Such deverbal nouns are often used with such verbs as: to have, to get, to take etc., e.g. to have a try, to give a push, to take a swim.

CRITERIA OF SEMANTIC DERIVATION

In cases of conversion the problem of criteria of semantic derivation arises: which of the converted pair is primary and which is converted from it. The problem was first analized by prof. A.I. Smirnitsky. Later on P.A. Soboleva developed his idea and worked out the following criteria:

1. If the lexical meaning of the root morpheme and the lexico-grammatical meaning of the stem coincide the word is primary, e.g. in cases pen — to pen, father — to father the nouns are names of an object and a living being. Therefore in the nouns «pen» and «father» the lexical meaning of the root and the lexico-grammatical meaning of the stem coincide. The verbs «to pen» and «to father» denote an action, a process therefore the lexico-grammatical meanings of the stems do not coincide with the lexical meanings of the roots. The verbs have a complex semantic structure and they were converted from nouns.

2. If we compare a converted pair with a synonymic word pair which was formed by means of suffixation we can find out which of the pair is primary. This criterion can be applied only to nouns converted from verbs, e.g. «chat» n. and «chat» v. can be compared with «conversation» – «converse».

3. The criterion based on derivational relations is of more universal character. In this case we must take a word-cluster of relative words to which the converted pair belongs. If the root stem of the word-cluster has suffixes added to a noun stem the noun is primary in the converted pair and vica versa, e.g. in the word-cluster: hand n., hand v., handy, handful the derived words have suffixes added to a noun stem, that is why the noun is primary and the verb is converted from it. In the word-cluster: dance n., dance v., dancer, dancing we see that the primary word is a verb and the noun is converted from it.

SUBSTANTIVIZATION OF ADJECTIVES

Some scientists (Yespersen, Kruisinga) refer substantivization of adjectives to conversion. But most scientists disagree with them because in cases of substantivization of adjectives we have quite different changes in the language. Substantivization is the result of ellipsis (syntactical shortening) when a word combination with a semantically strong attribute loses its semantically weak noun (man, person etc), e.g. «a grown-up person» is shortened to «a grown-up». In cases of perfect substantivization the attribute takes the paradigm of a countable noun, e.g. a criminal, criminals, a criminal’s (mistake), criminals’ (mistakes). Such words are used in a sentence in the same function as nouns, e.g. I am fond of musicals. (musical comedies). There are also two types of partly substantivized adjectives: 1) those which have only the plural form and have the meaning of collective nouns, such as: sweets, news, finals, greens; 2) those which have only the singular form and are used with the definite article. They also have the meaning of collective nouns and denote a class, a nationality, a group of people, e.g. the rich, the English, the dead.

«STONE WALL» COMBINATIONS

The problem whether adjectives can be formed by means of conversion from nouns is the subject of many discussions. In Modern English there are a lot of word combinations of the type, e.g. price rise, wage freeze, steel helmet, sand castle etc. If the first component of such units is an adjective converted from a noun, combinations of this type are free word-groups typical of English (adjective + noun). This point of view is proved by O. Yespersen by the following facts:

1. «Stone» denotes some quality of the noun «wall».

2. «Stone» stands before the word it modifies, as adjectives in the function of an attribute do in English.

3. «Stone» is used in the Singular though its meaning in most cases is plural, and adjectives in English have no plural form.

4. There are some cases when the first component is used in the Comparative or the Superlative degree, e.g. the bottomest end of the scale.

5. The first component can have an adverb which characterizes it, and adjectives are characterized by adverbs, e.g. a purely family gathering.

6. The first component can be used in the same syntactical function with a proper adjective to characterize the same noun, e.g. lonely bare stone houses.

7. After the first component the pronoun «one» can be used instead of a noun, e.g. I shall not put on a silk dress, I shall put on a cotton one.

However Henry Sweet and some other scientists say that these criteria are not characteristic of the majority of such units. They consider the first component of such units to be a noun in the function of an attribute because in Modern English almost all parts of speech and even word-groups and sentences can be used in the function of an attribute, e.g. the then president (an adverb), out-of-the-way villages (a word-group), a devil-may-care speed (a sentence). There are different semantic relations between the components of «stone wall» combinations. E.I. Chapnik classified them into the following groups:

1. time relations, e.g. evening paper,

2. space relations, e.g. top floor,

3. relations between the object and the material of which it is made, e.g. steel helmet,

4. cause relations, e.g. war orphan,

5. relations between a part and the whole, e.g. a crew member,

6. relations between the object and an action, e.g. arms production,

7. relations between the agent and an action e.g. government threat, price rise,

8. relations between the object and its designation, e.g. reception hall,

9. the first component denotes the head, organizer of the characterized object, e.g. Clinton government, Forsyte family,

10. the first component denotes the field of activity of the second component, e.g. language teacher, psychiatry doctor,

11. comparative relations, e.g. moon face,

12. qualitative relations, e.g. winter apples.

ABBREVIATION

In the process of communication words and word-groups can be shortened. The causes of shortening can be linguistic and extra-linguistic. By extra-linguistic causes changes in the life of people are meant. In Modern English many new abbreviations, acronyms, initials, blends are formed because the tempo of life is increasing and it becomes necessary to give more and more information in the shortest possible time. There are also linguistic causes of abbreviating words and word-groups, such as the demand of rhythm, which is satisfied in English by monosyllabic words. When borrowings from other languages are assimilated in English they are shortened. Here we have modification of form on the basis of analogy, e.g. the Latin borrowing «fanaticus» is shortened to «fan» on the analogy with native words: man, pan, tan etc. There are two main types of shortenings: graphical and lexical.

Graphical abbreviations

Graphical abbreviations are the result of shortening of words and word-groups only in written speech while orally the corresponding full forms are used. They are used for the economy of space and effort in writing. The oldest group of graphical abbreviations in English is of Latin origin. In Russian this type of abbreviation is not typical. In these abbreviations in the spelling Latin words are shortened, while orally the corresponding English equivalents are pronounced in the full form, e.g. for example (Latin exampli gratia), a.m. – in the morning (ante meridiem), No – number (numero), p.a. – a year (per annum), d – penny (dinarius), lb – pound (libra), i. e. – that is (id est) etc.

Some graphical abbreviations of Latin origin have different English equivalents in different contexts, e.g. p.m. can be pronounced «in the afternoon» (post meridiem) and «after death» (post mortem). There are also graphical abbreviations of native origin, where in the spelling we have abbreviations of words and word-groups of the corresponding English equivalents in the full form. We have several semantic groups of them: a) days of the week, e.g. Mon – Monday, Tue – Tuesday etc

b) names of months, e.g. Apr – April, Aug – August etc.

c) names of counties in UK, e.g. Yorks – Yorkshire, Berks – Berkshire etc

d) names of states in USA, e.g. Ala – Alabama, Alas – Alaska etc.

e) names of address, e.g. Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr. etc.

f) military ranks, e.g. capt. – captain, col. – colonel, sgt – sergeant etc.

g) scientific degrees, e.g. B.A. – Bachelor of Arts, D.M. – Doctor of Medicine. (Sometimes in scientific degrees we have abbreviations of Latin origin, e.g., M.B. – Medicinae Baccalaurus).

h) units of time, length, weight, e.g. f./ft – foot/feet, sec. – second, in. – inch, mg. – milligram etc.

The reading of some graphical abbreviations depends on the context, e.g. «m» can be read as: male, married, masculine, metre, mile, million, minute, «l.p.» can be read as long-playing, low pressure.

Initial abbreviations

Initialisms are the bordering case between graphical and lexical abbreviations. When they appear in the language, as a rule, to denote some new offices they are closer to graphical abbreviations because orally full forms are used, e.g. J.V. – joint venture. When they are used for some duration of time they acquire the shortened form of pronouncing and become closer to lexical abbreviations, e.g. BBC is as a rule pronounced in the shortened form. In some cases the translation of initialisms is next to impossible without using special dictionaries. Initialisms are denoted in different ways. Very often they are expressed in the way they are pronounced in the language of their origin, e.g. ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, United States) is given in Russian as АНЗУС, SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) was for a long time used in Russian as СОЛТ, now a translation variant is used (ОСВ – Договор об ограничении стратегических вооружений). This type of initialisms borrowed into other languages is preferable, e.g. UFO – НЛО, CП – JV etc. There are three types of initialisms in English:

a) initialisms with alphabetical reading, such as UK, BUP, CND etc

b) initialisms which are read as if they are words, e.g. UNESCO, UNO, NATO etc.

c) initialisms which coincide with English words in their sound form, such initialisms are called acronyms, e.g. CLASS (Computor-based Laboratory for Automated School System). Some scientists unite groups b) and c) into one group which they call acronyms. Some initialisms can form new words in which they act as root morphemes by different ways of wordbuilding:

a) affixation, e.g. AVALism, ex- POW, AIDSophobia etc.

b) conversion, e.g. to raff, to fly IFR (Instrument Flight Rules),

c) composition, e.g. STOLport, USAFman etc.

d) there are also compound-shortened words where the first component is an initial abbreviation with the alphabetical reading and the second one is a complete word, e.g. A-bomb, U-pronunciation, V -day etc. In some cases the first component is a complete word and the second component is an initial abbreviation with the alphabetical pronunciation, e.g. Three -Ds (Three dimensions) – стереофильм.

Abbreviations of words

Abbreviation of words consists in clipping a part of a word. As a result we get a new lexical unit where either the lexical meaning or the style is different form the full form of the word. In such cases as «fantasy» and «fancy», «fence» and «defence» we have different lexical meanings. In such cases as «laboratory» and «lab», we have different styles. Abbreviation does not change the part-of-speech meaning, as we have it in the case of conversion or affixation, it produces words belonging to the same part of speech as the primary word, e.g. prof. is a noun and professor is also a noun. Mostly nouns undergo abbreviation, but we can also meet abbreviation of verbs, such as to rev. from to revolve, to tab from to tabulate etc. But mostly abbreviated forms of verbs are formed by means of conversion from abbreviated nouns, e.g. to taxi, to vac etc. Adjectives can be abbreviated but they are mostly used in school slang and are combined with suffixation, e.g. comfy, dilly etc. As a rule pronouns, numerals, interjections. conjunctions are not abbreviated. The exceptions are: fif (fifteen), teen-ager, in one’s teens (apheresis from numerals from 13 to 19). Lexical abbreviations are classified according to the part of the word which is clipped. Mostly the end of the word is clipped, because the beginning of the word in most cases is the root and expresses the lexical meaning of the word. This type of abbreviation is called apocope. Here we can mention a group of words ending in «o», such as disco (dicotheque), expo (exposition), intro (introduction) and many others. On the analogy with these words there developed in Modern English a number of words where «o» is added as a kind of a suffix to the shortened form of the word, e.g. combo (combination) – небольшой эстрадный ансамбль, Afro (African) – прическа под африканца etc. In other cases the beginning of the word is clipped. In such cases we have apheresis, e.g. chute (parachute), varsity (university), copter (helicopter), thuse (enthuse) etc. Sometimes the middle of the word is clipped, e.g. mart (market), fanzine (fan magazine) maths (mathematics). Such abbreviations are called syncope. Sometimes we have a combination of apocope with apheresis, when the beginning and the end of the word are clipped, e.g. tec (detective), van (vanguard) etc. Sometimes shortening influences the spelling of the word, e.g. «c» can be substituted by «k» before «e» to preserve pronunciation, e.g. mike (microphone), Coke (coca-cola) etc. The same rule is observed in the following cases: fax (facsimile), teck (technical college), trank (tranquilizer) etc. The final consonants in the shortened forms are substituded by letters characteristic of native English words.

NON-PRODUCTIVE WAYS OF WORDBUILDING

SOUND INTERCHANGE

Sound interchange is the way of word-building when some sounds are changed to form a new word. It is non-productive in Modern English, it was productive in Old English and can be met in other Indo-European languages. The causes of sound interchange can be different. It can be the result of Ancient Ablaut which cannot be explained by the phonetic laws during the period of the language development known to scientists, e.g. to strike – stroke, to sing – song etc. It can be also the result of Ancient Umlaut or vowel mutation which is the result of palatalizing the root vowel because of the front vowel in the syllable coming after the root (regressive assimilation), e.g. hot — to heat (hotian), blood — to bleed (blodian) etc. In many cases we have vowel and consonant interchange. In nouns we have voiceless consonants and in verbs we have corresponding voiced consonants because in Old English these consonants in nouns were at the end of the word and in verbs in the intervocalic position, e.g. bath – to bathe, life – to live, breath – to breathe etc.

STRESS INTERCHANGE

Stress interchange can be mostly met in verbs and nouns of Romanic origin: nouns have the stress on the first syllable and verbs on the last syllable, e.g. `accent — to ac`cent. This phenomenon is explained in the following way: French verbs and nouns had different structure when they were borrowed into English, verbs had one syllable more than the corresponding nouns. When these borrowings were assimilated in English the stress in them was shifted to the previous syllable (the second from the end). Later on the last unstressed syllable in verbs borrowed from French was dropped (the same as in native verbs) and after that the stress in verbs was on the last syllable while in nouns it was on the first syllable. As a result of it we have such pairs in English as: to af«fix -`affix, to con`flict- `conflict, to ex`port -`export, to ex`tract — `extract etc. As a result of stress interchange we have also vowel interchange in such words because vowels are pronounced differently in stressed and unstressed positions.

SOUND IMITATION

It is the way of word-building when a word is formed by imitating different sounds. There are some semantic groups of words formed by means of sound imitation:

a) sounds produced by human beings, such as : to whisper, to giggle, to mumble, to sneeze, to whistle etc.

b) sounds produced by animals, birds, insects, such as: to hiss, to buzz, to bark, to moo, to twitter etc.

c) sounds produced by nature and objects, such as: to splash, to rustle, to clatter, to bubble, to ding-dong, to tinkle etc.

The corresponding nouns are formed by means of conversion, e.g. clang (of a bell), chatter (of children) etc.

BLENDS

Blends are words formed from a word-group or two synonyms. In blends two ways of word-building are combined: abbreviation and composition. To form a blend we clip the end of the first component (apocope) and the beginning of the second component (apheresis) . As a result we have a compound- shortened word. One of the first blends in English was the word «smog» from two synonyms: smoke and fog which means smoke mixed with fog. From the first component the beginning is taken, from the second one the end, «o» is common for both of them. Blends formed from two synonyms are: slanguage, to hustle, gasohol etc. Mostly blends are formed from a word-group, such as: acromania (acronym mania), cinemaddict (cinema adict), chunnel (channel, canal), dramedy (drama comedy), detectifiction (detective fiction), faction (fact fiction) (fiction based on real facts), informecial (information commercial), Medicare (medical care), magalog (magazine catalogue) slimnastics (slimming gymnastics), sociolite (social elite), slanguist (slang linguist) etc.

BACK FORMATION

It is the way of word-building when a word is formed by dropping the final morpheme to form a new word. It is opposite to suffixation, that is why it is called back formation. At first it appeared in the language as a result of misunderstanding the structure of a borrowed word. Prof. Yartseva explains this mistake by the influence of the whole system of the language on separate words. E.g. it is typical of English to form nouns denoting the agent of the action by adding the suffix -er to a verb stem (speak- speaker). So when the French word «beggar» was borrowed into English the final syllable «ar» was pronounced in the same way as the English —er and Englishmen formed the verb «to beg» by dropping the end of the noun. Other examples of back formation are: to accreditate (from accreditation), to bach (from bachelor), to collocate (from collocation), to enthuse (from enthusiasm), to compute (from computer), to emote (from emotion), to televise (from television) etc.

As we can notice in cases of back formation the part-of-speech meaning of the primary word is changed, verbs are formed from nouns.

23

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

The main types of words in English and their morphological structure.

2.

Affixation (or derivation).

3.

Compounding.

4.

Conversion.

5.

Abbreviation (shortening).

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material

available

in the language.

Before

turning to various processes of word-building in English, it would be

useful

to analyze the main types of English words and their morphological

structure.

If

viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units

which are

called

morphemes.

Morphemes

do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of

words.

Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All

morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots

(or

radicals)

and

affixes.

The

latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes

which

precede the root in the

structure

of the word (as in re-real,

mis-pronounce, un-well) and

suffixes

which

follow

the root (as in teach-er,

cur-able, dict-ate).

Words

which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived

words or

derivatives

and

are produced by the process of word-building

known

as affixation

(or

derivation).

Derived

words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully

competing with this structural type is the so-called root

word which

has

only

a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by

a great

number

of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings

(house,

room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and,

in Modern English, has been

greatly

enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion

(e.g.

to

hand, v.

formed

from the noun hand;

to can, v.

from can,

n.;

to

pale,

v. from pale,

adj.;

a

find,

n.

from to

find, v.;

etc.).

Another

wide-spread word-structure is a compound

word consisting

of two or

more

stems (e.g. dining-room,

bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing).

Words of

this

structural type are produced by the word-building process called

composition.

The

somewhat odd-looking words like flu,

lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb are

called

curtailed

words and

are produced by the way of word-building called shortening

(abbreviation).

The

four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings)

represent

the

main structural types of Modern English words, and affixation

(derivation),

conversion,

composition and shortening (abbreviation) — the most productive ways

of

word-building.

83

The

process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or

several

affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very

important

and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the

main types

of

affixes.

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two

large

groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some

Native Suffixes

-er

worker,

miner,

teacher,

painter,

etc.

-ness

coldness,

loneliness,

loveliness,

etc.

-ing

feeling,

meaning,

singing,

reading,

etc.

-dom

freedom,

wisdom,

kingdom,

etc.

-hood

childhood,

manhood,

motherhood,

etc.

-ship

friendship,

companionship,

mastership,

etc.

Noun-forming

-th

length,

breadth,

health,

truth,

etc.

-ful

careful,

joyful,

wonderful,

sinful,

skilful,

etc.

-less

careless,

sleepless,

cloudless,

senseless,

etc.

-y

cozy,

tidy,

merry,

snowy,

showy,

etc.

-ish

English,

Spanish,

reddish,

childish,

etc.

-ly

lonely,

lovely,

ugly,

likely,

lordly,

etc.

-en

wooden,

woollen,

silken,

golden,

etc.

Adjective-forming

-some

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Verb-

forming

-en

widen,

redden,

darken,

sadden,

etc.

Adverb-

forming

-ly

warmly,

hardly,

simply,

carefully,

coldly,

etc.

Borrowed

affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English

vocabulary.

We can recognize words of Latin and French origin by certain suffixes

or

prefixes;

e. g. Latin

affixes:

-ion,

-tion, -ate,

-ute

,

-ct,

-d(e), dis-, -able, -ate,

-ant,

—

ent,

-or, -al, -ar in

such words as opinion,

union, relation, revolution, appreciate,

congratulate,

attribute, contribute, , act, collect, applaud, divide, disable,

disagree,

detestable,

curable, accurate, desperate, arrogant, constant, absent, convenient,

major,

minor, cordial, familiar;

French

affixes –ance,

—ewe,

-ment, -age, -ess, -ous,

en-

in

such words as arrogance,

intelligence, appointment, development, courage,

marriage,

tigress, actress, curious, dangerous, enable, enslaver.

Affixation

includes a) prefixation

–

derivation of words by adding a prefix to

full

words and b) suffixation

–

derivation of words by adding suffixes to bound

stems.

Prefixes

and suffixes have their own valency, that is they may be added not to

any

stem at random, but only to a particular type of stems:

84

Prefix

un-

is

prefixed to adjectives (as: unequal,

unhealthy), or

to adjectives

derived

from verb stems and the suffix -able

(as:

unachievable,

unadvisable), or

to

participial

adjectives (as: unbecoming,

unending, unstressed, unbound); the

suffix —

er

is

added to verbal stems (as: worker,

singer, or

cutter,

lighter), and

to substantive

stems

(as: glover,

needler); the

suffix -able

is

usually tacked on to verb stems (as:

eatable,

acceptable); the

suffix -ity

in

its turn is usually added to adjective stems

with

a passive meaning (as: saleability,

workability), but

the suffix —ness

is

tacked on

to

other adjectives, having the suffix -able

(as:

agreeableness.

profitableness).

Prefixes

and suffixes are semantically distinctive, they have their own

meaning,

while the root morpheme forms the semantic centre of a word. Affixes

play

a

dependent role in the meaning of the word. Suffixes have a

grammatical meaning,

they

indicate or derive a certain part of speech, hence we distinguish:

noun-forming

suffixes,

adjective-forming suffixes, verb-forming suffixes and adverb-forming

suffixes.

Prefixes change or concretize the meaning of the word, as: to

overdo (to

do

too

much),

to underdo (to

do less than one can or is proper),

to outdo (to

do more or

better

than),

to undo (to

unfasten, loosen, destroy the result, ruin),

to misdo (to

do

wrongly

or unproperly).

A

suffix indicates to what semantic group the word belongs. The suffix

-er

shows

that the word is a noun bearing the meaning of a doer of an action,

and the

action

is denoted by the root morpheme or morphemes, as: writer,

sleeper, dancer,

wood-pecker,

bomb-thrower, the

suffix -ion/-tion,

indicates

that it is a noun

signifying

an action or the result of an action, as: translation

‘a

rendering from one

language

into another’ (an

act, process) and

translation

‘the

product of such

rendering’;

nouns with the suffix -ism

signify

a system, doctrine, theory, adherence to

a

system, as: communism,

realism; coinages

from the stem of proper names are

common,.

as Darwinism.

Affixes

can also be classified into productive

and

non-productive

types.

By

productive

affixes we

mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in a

particular

period of language development. The best way to identify productive

affixes

is to look for them among neologisms

and

so-called nonce-words,

i.e.

words

coined

and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually

formed on the

level

of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive

patterns in

word-building.

When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an

unputdownable

thriller, we

will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in

dictionaries,

for it is a nonce-word coined on the current pattern of Modern

English

and

is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming

borrowed suffix –

able

and

the native prefix un-,

e.g.: Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish,

dyspeptic-lookingish

cove with an eye like a haddock.(From

Right-Ho, Jeeves by P.G.

Wodehouse)

The

adjectives thinnish

and

baldish

bring

to mind dozens of other adjectives

made

with the same suffix: oldish,

youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish,

yellowish,

etc. But

dyspeptic-lookingish

is

the author’s creation aimed at a humorous

effect,

and, at the same time, providing beyond doubt that the suffix –ish

is

a live and

active

one.

85

The

same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: “I

don’t like

Sunday

evenings: I feel so Mondayish”. (Mondayish is

certainly a nonce-word.)

One

should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency

of

occurrence

(use). There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which,

nevertheless,

are no longer used in word-derivation (e.g. the adjective-forming

native

suffixes

–ful,

-ly; the

adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin –ant,

-ent, -al which

are

quite frequent).

Some

Productive Affixes

Some

Non-Productive Affixes

Noun-forming

suffixes

-th,

-hood

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—ly,

-some, -en, -ous

Verb-forming

suffix -en

Compound

words are

words derived from two or more stems. It is a very old

word-formation

type and goes back to Old English. In Modern English compounds

are

coined by joining one stem to another by mere juxtaposition, as

raincoat,

keyhole,

pickpocket,

red-hot, writing-table. Each

component of a compound coincides

with

the word. Compounds are the commonest among nouns and adjectives.

Compound

verbs are few in number, as they are mostly the result of conversion

(as,

to

weekend) and

of back-formation (as, to

stagemanage).

From

the point of view of word-structure compounds consist of free stems

and

may

be of different structure: noun stems + noun stem (raincoat);

adjective

stem +

noun

stem (bluebell);

adjective

stem + adjective stem (dark-blue);

gerundial

stem +

noun

stem (writing-table);

verb

stem + post-positive stem (make-up);

adverb

stem +

adjective

stem (out-right);

two

noun stems connected by a preposition (man-of-war)

and

others. There are compounds that have a connecting vowel (as,

speedometer,

handicraft),

but

it is not characteristic of English compounds.

Compounds

may be idiomatic

and

non-idiomatic.

In idiomatic compounds the

meaning

of each component is either lost or weakened, as buttercup

(лютик),

chatter-box

(болтун).

These

are entirely

demotivated compounds. There

are also motivated

compounds,

as lifeboat

(спасательная

лодка). In non-idiomatic compounds the

Noun-forming

suffixes

—er,

-ing,

—ness,

-ism (materialism),

-ist

(impressionist),

-ance

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—y,

-ish, -ed (learned),

—able,

—less

Adverb-forming

suffix

—ly

Verb-forming

suffixes

—ize/-ise

(realize),

—ate

Prefixes

un-

(unhappy),re-

(reconstruct),

dis-

(disappoint)

86

meaning

of each component is retained, as apple-tree,

bedroom, sunlight. There

are

also

many border-line cases.

The

components of compounds may have different semantic relations; from

this

point of view we can roughly classify compounds into endocentric

and

exocentric

compounds.

In endocentric compounds the semantic centre is found

within

the compound and the first element determines the other, as

film-star,

bedroom,

writing-table.

In

exocentric compounds there is no semantic centre, as

scarecrow.

In

Modern English, however, linguists find it difficult to give criteria

for

compound

nouns; it is still a question of hot dispute. The following criteria

may be

offered.

A compound noun is characterized by a) one word or hyphenated

spelling, b)

one

stress, and by c) semantic integrity. These are the so-called

“classical

compounds”.

It

is possible that a compound has only two of these criteria, for

instance, the

compound

words headache,

railway have

one stress and hyphenated or one-word

spelling,

but do not present a semantic unity, whereas the compounds

motor-bike,

clasp-knife

have

hyphenated spelling and idiomatic meaning, but two even stresses

(‘motor-‘bike,

‘clasp-‘knife).

The word apple-tree

is

also a compound; it is spelt either

as

one word or is hyphenated, has one stress (‘apple-tree),

but it is not idiomatic. The

difficulty

of defining a compound lies in spelling which might be misleading, as

there

are

no hard and fast rules of spelling the compounds: three ways of

spelling are

possible:

(‘dockyard,

‘dock yard and

dock-yard).

The

same holds true for the stress

that

may differ from one reference-book to another.

Since

compounds may have two stresses and the stems may be written

separately,

it is difficult to draw the line between compounds proper and nominal

word-combinations

or syntactical combinations. In a combination of words each

element

is stressed and written separately. Compare the attributive

combination

‘black

‘board, a

board which is black (each element has its own meaning; the first

element

modifies the second) and the compound ‘blackboard’,

a

board or a sheet of

slate

used in schools for teaching purposes (the word has one stress and

presents a

semantic

unit). But it is not always easy as that to draw a distinction, as

there are

word-combinations

that may present a semantic unity, take for instance: green

room

(a

room in a theatre for actors and actresses).

Compound

derivatives are

words, usually nouns and adjectives, consisting of

a

compound stem and a suffix, the commonest type being such nouns as:

firstnighter,

type-writer,

bed-sitter, week-ender, house-keeping, well-wisher, threewheeler,

old-timer,

and

the adjectives: blue-eyed,

blond-haired, four-storied, mildhearted,

high-heeled.

The

structure of these nouns is the following: a compound stem

+

the suffix -er,

or

the suffix -ing.

Adjectives

have the structure: a compound stem, containing an adjective (noun,

numeral)

stem and a noun stem + the suffix -ed.

In

Modern English it is an extremely

productive

type of adjectives, e.g.: big-eyed,

long-legged, golden-haired.

In

Modern English it is common practice to distinguish also

semi-suffixes, that

is

word-formative elements that correspond to full words as to their

lexical meaning

and

spelling, as -man,

-proof, -like: seaman, railroadman, waterproof, kiss-proof,

ladylike,

businesslike. The

pronunciation may be the same (cp. proof

[pru:f]

and

87

waterproof

[‘wL:tq

pru:f],

or differ, as is the case with the morpheme -man

(cp.

man

[mxn]

and seaman

[‘si:mqn].

The

commonest is the semi-suffix -man

which

has a more general meaning —

‘a

person of trade or profession or carrying on some work’, as: airman,

radioman,

torpedoman,

postman, cameramen, chairman and

others. Many of them have

synonyms

of a different word structure, as seaman

— sailor, airman — flyer,

workman

— worker; if

not a man but a woman

of

the trade or profession, or a person

carrying

on some work is denoted by the word, the second element is woman,

as

chairwoman,

air-craftwoman, congresswoman, workwoman, airwoman.

Conversion

is

a very productive way of forming new words in English, chiefly

verbs

and not so often — nouns. This type of word formation presents one

of the

characteristic

features of Modern English. By conversion we mean derivation of a

new

word from the stem of a different part of speech without the addition

of any

formatives.

As a result the two words are homonymous, having the same

morphological

structure and belonging to different parts of speech.

Verbs

may be derived from the stem of almost any part of speech, but the

commonest

is the derivation from noun stems as: (a)

tube — (to) tube; (a) doctor —

(to)

doctor, (a) face—(to) face; (a) waltz—(to) waltz; (a) star—(to)

star; from

compound

noun stems as: (a)

buttonhole — (to) buttonhole; week-end — (to) weekend.

Derivations

from the stems of other parts of speech are less common: wrong—

(to)

wrong; up — (to) up; down — (to) down; encore — (to) encore.

Nouns

are

usually

derived from verb stems and may be instanced by such nouns as: (to)

make—

a

make; (to) cut—(a) cut; to bite — (a) bite, (to) drive — (a)

drive; to smoke — (a)

smoke;

(to) walk — (a) walk. Such

formations frequently make part of verb — noun

combinations

as: to

take a walk, to have a smoke, to have a drink, to take a drive, to

take

a bite, to give a smile and

others.

Nouns

may be also derived from verb-postpositive phrases. Such formations

are

very common in Modern English, as for instance: (to)

make up — (a) make-up;

(to)

call up — (a) call-up; (to) pull over — (a) pullover.

New

formations by conversion from simple or root stems are quite usual;

derivatives

from suffixed stems are rare. No verbal derivation from prefixed

stems is

found.

The

derived word and the deriving word are connected semantically. The

semantic

relations between the derived and the deriving word are varied and

sometimes

complicated. To mention only some of them: a) the verb signifies the

act

accomplished

by or by means of the thing denoted by the noun, as: to

finger means

‘to

touch with the finger, turn about in fingers’; to

hand means

‘to give or help with

the

hand, to deliver, transfer by hand’; b) the verb may have the meaning

‘to act as the

person

denoted by the noun does’, as: to

dog means

‘to follow closely’, to

cook — ‘to

prepare

food for the table, to do the work of a cook’; c) the derived verbs

may have

the

meaning ‘to go by’ or ‘to travel by the thing denoted by the noun’,

as, to

train

means

‘to go by train’, to

bus — ‘to

go by bus’, to

tube — ‘to

travel by tube’; d) ‘to

spend,

pass the time denoted by the noun’, as, to

winter ‘to pass

the winter’, to

weekend

— ‘to

spend the week-end’.

88

Derived

nouns denote: a) the act, as a

knock, a hiss, a smoke; or

b) the result of

an

action, as a

cut, a find, a call, a sip, a run.

A

characteristic feature of Modern English is the growing frequency of

new

formations

by conversion, especially among verbs.

Note.

A grammatical homonymy of two words of different parts of speech —

a

verb

and a noun, however, does not necessarily indicate conversion. It may

be the

result

of the loss of endings as well. For instance, if we take the

homonymic pair love

— to

love and

trace it back, we see that the noun love

comes

from Old English lufu,

whereas

the verb to

love—from

Old English lufian,

and

the noun answer

is

traced

back

to the Old English andswaru,

but

the verb to

answer to

Old English

andswarian;

so

that it is the loss of endings that gave rise to homonymy. In the

pair

bus

— (to) bus, weekend — (to) weekend homonymy

is the result of derivation by

conversion.

Shortenings

(abbreviations)

are words produced either by means of clipping

full

word or by shortening word combinations, but having the meaning of

the full

word

or combination. A distinction is to be observed between graphical

and

lexical

shortenings;

graphical abbreviations are signs or symbols that stand for the full

words

or combination of words only in written speech. The commonest form is

an

initial

letter or letters that stand for a word or combination of words. But

to prevent

ambiguity

one or two other letters may be added. For instance: p.

(page),

s.

(see),

b.

b.

(ball-bearing).

Mr

(mister),

Mrs

(missis),

MS

(manuscript),

fig.

(figure). In oral

speech

graphical abbreviations have the pronunciation of full words. To

indicate a

plural

or a superlative letters are often doubled, as: pp.

(pages). It is common practice

in

English to use graphical abbreviations of Latin words, and word

combinations, as:

e.

g. (exampli

gratia), etc.

(et cetera), i.

e. (id

est). In oral speech they are replaced by

their

English equivalents, ‘for

example’,

‘and

so on’,

‘namely‘,

‘that

is’,

‘respectively’.

Graphical

abbreviations are not words but signs or symbols that stand for the

corresponding

words. As for lexical

shortenings,

two main types of lexical

shortenings

may be distinguished: 1) abbreviations

or

clipped

words (clippings)

and

2) initial

words (initialisms).

Abbreviation

or

clipping

is

the result of reduction of a word to one of its

parts:

the meaning of the abbreviated word is that of the full word. There

are different

types

of clipping: 1) back-clipping—the

final part of the word is clipped, as: doc

—

from

doctor,

lab — from

laboratory,

mag — from

magazine,

math — from

mathematics,

prefab —

from prefabricated;

2) fore-clipping

—

the first part of the

word

is clipped as: plane

— from

aeroplane,

phone — from

telephone,

drome —

from

aerodrome.

Fore-clippings

are less numerous in Modern English; 3) the

fore

and

the back parts of the word are clipped and the middle of the word is

retained,

as: tec

— from

detective,

flu — from

influenza.

Words

of this type are few

in

Modern English. Back-clippings are most numerous in Modern English

and are

characterized

by the growing frequency. The original may be a simple word (as,

grad—from

graduate),

a

derivative (as, prep—from

preparation),

a

compound, (as,

foots

— from

footlights,

tails — from

tailcoat),

a

combination of words (as pub —

from

public

house, medico — from

medical

student). As

a result of clipping usually

nouns

are produced, as pram

— from

perambulator,

varsity — for

university.

In

some

89

rare

cases adjectives are abbreviated (as, imposs

—from

impossible,

pi — from

pious),

but

these are infrequent. Abbreviations or clippings are words of one

syllable

or

of two syllables, the final sound being a consonant or a vowel

(represented by the

letter

o), as, trig

(for

trigonometry),

Jap (for

Japanese),

demob (for

demobilized),

lino

(for

linoleum),

mo (for

moment).

Abbreviations

are made regardless of whether the

remaining

syllable bore the stress in the full word or not (cp. doc

from

doctor,

ad

from

advertisement).

The

pronunciation of abbreviations usually coincides with the

corresponding

syllable in the full word, if the syllable is stressed: as, doc

[‘dOk]

from

doctor

[‘dOktq];

if it is an unstressed syllable in the full word the pronunciation

differs,

as the abbreviation has a full pronunciation: as, ad

[xd],

but advertisement

[qd’vq:tismqnt].

There may be some differences in spelling connected with the

pronunciation

or with the rules of English orthoepy, as mike

— from

microphone,

bike

— from

bicycle,

phiz —

from physiognomy,

lube — from

lubrication.

The

plural

form

of the full word or combinations of words is retained in the

abbreviated word,

as,

pants

— from

pantaloons,

digs — from

diggings.

Abbreviations

do not differ from full words in functioning; they take the plural

ending

and that of the possessive case and make any part of a sentence.

New

words may be derived from the stems of abbreviated words by

conversion

(as

to

demob, to taxi, to perm) or

by affixation, chiefly by adding the suffix —y,

-ie,

deriving

diminutives and petnames (as, hanky

— from

handkerchief,

nighty (nightie)

— from

nightgown,

unkie — from

uncle,

baccy — from

tobacco,

aussie — from

Australians,

granny (ie)

— from grandmother).

In

this way adjectives also may be

derived

(as: comfy

— from

comfortable,

mizzy — from

miserable).

Adjectives

may be

derived

also by adding the suffix -ee,

as:

Portugee

— for

Portuguese,

Chinee — for

Chinese.

Abbreviations

do not always coincide in meaning with the original word, for

instance:

doc

and

doctor

have

the meaning ‘one who practises medicine’, but doctor

is

also

‘the highest degree given by a university to a scholar or scientist

and ‘a person

who

has received such a degree’ whereas doc

is

not used in these meanings. Among

abbreviations

there are homonyms, so that one and the same sound and graphical

complex

may represent different words, as vac

(vacation), vac (vacuum cleaner);

prep

(preparation), prep (preparatory school). Abbreviations

usually have synonyms

in

literary English, the latter being the corresponding full words. But

they are not

interchangeable,

as they are words of different styles of speech. Abbreviations are

highly

colloquial; in most cases they belong to slang. The moment the longer

word

disappears

from the language, the abbreviation loses its colloquial or slangy

character

and

becomes a literary word, for instance, the word taxi

is

the abbreviation of the

taxicab

which,

in its turn, goes back to taximeter

cab; both

words went out of use,

and

the word taxi

lost

its stylistic colouring.

Initial

abbreviations (initialisms)

are words — nouns — produced by

shortening

nominal combinations; each component of the nominal combination is

shortened

up to the initial letter and the initial letters of all the words of

the

combination

make a word, as: YCL — Young

Communist League, MP

—

Member

of Parliament. Initial

words are distinguished by their spelling in capital

letters

(often separated by full stops) and by their pronunciation — each

letter gets

90

its

full alphabetic pronunciation and a full stress, thus making a new

word as R.

A.

F. [‘a:r’ei’ef] — Royal

Air Force; TUC.

[‘ti:’ju:’si:] — Trades

Union Congress.

Some

of initial words may be pronounced in accordance with the’ rules of

orthoepy,

as N. A. T. O. [‘neitou], U. N. O. [‘ju:nou], with the stress on the

first

syllable.

The

meaning of the initial word is that of the nominal combination. In

speech

initial words function like nouns; they take the plural suffix, as

MPs, and

the

suffix of the possessive case, as MP’s, POW’s.

In

Modern English the commonest practice is to use a full combination

either

in

the heading or in the text and then quote this combination by giving

the first initial

of

each word. For instance, «Jack Bruce is giving UCS concert»

(the heading). «Jack

Bruce,

one of Britain’s leading rock-jazz musicians, will give a benefit

concert in

London

next week to raise money for the Upper Clyde shop stewards’ campaign»

(Morning

Star).

New

words may be derived from initial words by means of adding affixes,

as

YCL-er,

ex-PM, ex-POW; MP’ess, or adding the semi-suffix —man,

as

GI-man.

As

soon

as the corresponding combination goes out of use the initial word

takes its place

and

becomes fully established in the language and its spelling is in

small letters, as

radar

[‘reidq]

— radio detecting and ranging, laser

[‘leizq]

— light amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation; maser

[‘meizq]

— microwave amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation. There are also semi-shortenings, as, A-bomb

(atom

bomb),

H-bomber

(hydrogen

bomber), U-boat

(Untersee

boat) — German submarine.

The

first component of the nominal combination is shortened up to the

initial letter,

the

other component (or components) being full words.

4.7.

ENGLISH PHRASEOLOGY: STRUCTURAL AND SEMANTIC

PECULIARITIES

OF PHRASEOLOGICAL UNITS, THEIR CLASSIFICATION

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

Main approaches to the definition of a phraseological unit in

linguistics.

2.

Different classifications of phraseological units.

3.

Grammatical and lexical modifications of phraseological units in

speech.

In

linguistics there are two main theoretical schools treating the

problems of

English

phraseology — that of N.N.Amosova and that of A. V. Kunin. We shall

not

dwell

upon these theories in detail, but we shall try to give the guiding

principles of

each

of the authors. According to the theory of N.N. Amosova. A

phraseological unit

is

a unit of constant context. It is a stable combination of words in