Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure.[1][2][3][4] There is currently no scientific consensus on a definition.[5][6] Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.[7]

Research on emotion has increased over the past two decades with many fields contributing including psychology, medicine, history, sociology of emotions, and computer science. The numerous attempts to explain the origin, function and other aspects of emotions have fostered intense research on this topic. Theorizing about the evolutionary origin and possible purpose of emotion dates back to Charles Darwin. Current areas of research include the neuroscience of emotion, using tools like PET and fMRI scans to study the affective picture processes in the brain.[8]

From a mechanistic perspective, emotions can be defined as «a positive or negative experience that is associated with a particular pattern of physiological activity.»[4] Emotions are complex, involving multiple different components, such as subjective experience, cognitive processes, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behavior.[9][10] At one time, academics attempted to identify the emotion with one of the components: William James with a subjective experience, behaviorists with instrumental behavior, psychophysiologists with physiological changes, and so on. More recently, emotion is said to consist of all the components. The different components of emotion are categorized somewhat differently depending on the academic discipline. In psychology and philosophy, emotion typically includes a subjective, conscious experience characterized primarily by psychophysiological expressions, biological reactions, and mental states. A similar multi-componential description of emotion is found in sociology. For example, Peggy Thoits described emotions as involving physiological components, cultural or emotional labels (anger, surprise, etc.), expressive body actions, and the appraisal of situations and contexts.[11] Cognitive processes, like reasoning and decision-making, are often regarded as separate from emotional processes, making a division between «thinking» and «feeling». However, not all theories of emotion regard this separation as valid.[12]

Nowadays most research into emotions in the clinical and well-being context focuses on emotion dynamics in daily life, predominantly the intensity of specific emotions, and their variability, instability, inertia, and differentiation, and whether and how emotions augment or blunt each other over time, and differences in these dynamics between people and along the lifespan.[13]

Etymology[edit]

The word «emotion» dates back to 1579, when it was adapted from the French word émouvoir, which means «to stir up». The term emotion was introduced into academic discussion as a catch-all term to passions, sentiments and affections.[14] The word «emotion» was coined in the early 1800s by Thomas Brown and it is around the 1830s that the modern concept of emotion first emerged for the English language.[15] «No one felt emotions before about 1830. Instead they felt other things – ‘passions’, ‘accidents of the soul’, ‘moral sentiments’ – and explained them very differently from how we understand emotions today.»[15]

Some cross-cultural studies indicate that the categorization of «emotion» and classification of basic emotions such as «anger» and «sadness» are not universal and that the boundaries and domains of these concepts are categorized differently by all cultures.[16] However, others argue that there are some universal bases of emotions (see Section 6.1).[17] In psychiatry and psychology, an inability to express or perceive emotion is sometimes referred to as alexithymia.[18]

History[edit]

Human nature and the accompanying bodily sensations have always been part of the interests of thinkers and philosophers. Far more extensively, this has also been of great interest to both Western and Eastern societies. Emotional states have been associated with the divine and with the enlightenment of the human mind and body.[19] The ever-changing actions of individuals and their mood variations have been of great importance to most of the Western philosophers (including Aristotle, Plato, Descartes, Aquinas, and Hobbes), leading them to propose extensive theories—often competing theories—that sought to explain emotion and the accompanying motivators of human action, as well as its consequences.

In the Age of Enlightenment, Scottish thinker David Hume[20] proposed a revolutionary argument that sought to explain the main motivators of human action and conduct. He proposed that actions are motivated by «fears, desires, and passions». As he wrote in his book A Treatise of Human Nature (1773): «Reason alone can never be a motive to any action of the will… it can never oppose passion in the direction of the will… The reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them».[21] With these lines, Hume attempted to explain that reason and further action would be subject to the desires and experience of the self. Later thinkers would propose that actions and emotions are deeply interrelated with social, political, historical, and cultural aspects of reality that would also come to be associated with sophisticated neurological and physiological research on the brain and other parts of the physical body.

Definitions[edit]

The Lexico definition of emotion is «A strong feeling deriving from one’s circumstances, mood, or relationships with others.»[22] Emotions are responses to significant internal and external events.[23]

Emotions can be occurrences (e.g., panic) or dispositions (e.g., hostility), and short-lived (e.g., anger) or long-lived (e.g., grief).[24] Psychotherapist Michael C. Graham describes all emotions as existing on a continuum of intensity.[25] Thus fear might range from mild concern to terror or shame might range from simple embarrassment to toxic shame.[26] Emotions have been described as consisting of a coordinated set of responses, which may include verbal, physiological, behavioral, and neural mechanisms.[27]

Emotions have been categorized, with some relationships existing between emotions and some direct opposites existing. Graham differentiates emotions as functional or dysfunctional and argues all functional emotions have benefits.[28]

In some uses of the word, emotions are intense feelings that are directed at someone or something.[29] On the other hand, emotion can be used to refer to states that are mild (as in annoyed or content) and to states that are not directed at anything (as in anxiety and depression). One line of research looks at the meaning of the word emotion in everyday language and finds that this usage is rather different from that in academic discourse.[30]

In practical terms, Joseph LeDoux has defined emotions as the result of a cognitive and conscious process which occurs in response to a body system response to a trigger.[31]

Components[edit]

According to Scherer’s Component Process Model (CPM) of emotion,[10] there are five crucial elements of emotion. From the component process perspective, emotional experience requires that all of these processes become coordinated and synchronized for a short period of time, driven by appraisal processes. Although the inclusion of cognitive appraisal as one of the elements is slightly controversial, since some theorists make the assumption that emotion and cognition are separate but interacting systems, the CPM provides a sequence of events that effectively describes the coordination involved during an emotional episode.

- Cognitive appraisal: provides an evaluation of events and objects.

- Bodily symptoms: the physiological component of emotional experience.

- Action tendencies: a motivational component for the preparation and direction of motor responses.

- Expression: facial and vocal expression almost always accompanies an emotional state to communicate reaction and intention of actions.

- Feelings: the subjective experience of emotional state once it has occurred.

Differentiation[edit]

Emotion can be differentiated from a number of similar constructs within the field of affective neuroscience:[27]

- Emotions: predispositions to a certain type of action in response to a specific stimulus, which produce a cascade of rapid and synchronized physiological and cognitive changes.[9]

- Feeling: not all feelings include emotion, such as the feeling of knowing. In the context of emotion, feelings are best understood as a subjective representation of emotions, private to the individual experiencing them.[32][better source needed]

- Moods: diffuse affective states that generally last for much longer durations than emotions; they are also usually less intense than emotions and often appear to lack a contextual stimulus.[29]

- Affect: used to describe the underlying affective experience of an emotion or a mood.

Purpose and value[edit]

One view is that emotions facilitate adaptive responses to environmental challenges. Emotions have been described as a result of evolution because they provided good solutions to ancient and recurring problems that faced our ancestors.[33] Emotions can function as a way to communicate what’s important to individuals, such as values and ethics.[34] However some emotions, such as some forms of anxiety, are sometimes regarded as part of a mental illness and thus possibly of negative value.[35]

Classification[edit]

A distinction can be made between emotional episodes and emotional dispositions. Emotional dispositions are also comparable to character traits, where someone may be said to be generally disposed to experience certain emotions. For example, an irritable person is generally disposed to feel irritation more easily or quickly than others do. Finally, some theorists place emotions within a more general category of «affective states» where affective states can also include emotion-related phenomena such as pleasure and pain, motivational states (for example, hunger or curiosity), moods, dispositions and traits.[36]

Basic emotions[edit]

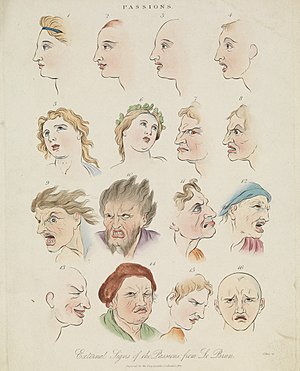

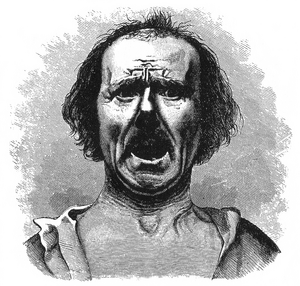

Examples of basic emotions

For more than 40 years, Paul Ekman has supported the view that emotions are discrete, measurable, and physiologically distinct. Ekman’s most influential work revolved around the finding that certain emotions appeared to be universally recognized, even in cultures that were preliterate and could not have learned associations for facial expressions through media. Another classic study found that when participants contorted their facial muscles into distinct facial expressions (for example, disgust), they reported subjective and physiological experiences that matched the distinct facial expressions. Ekman’s facial-expression research examined six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.[37]

Later in his career,[38] Ekman theorized that other universal emotions may exist beyond these six. In light of this, recent cross-cultural studies led by Daniel Cordaro and Dacher Keltner, both former students of Ekman, extended the list of universal emotions. In addition to the original six, these studies provided evidence for amusement, awe, contentment, desire, embarrassment, pain, relief, and sympathy in both facial and vocal expressions. They also found evidence for boredom, confusion, interest, pride, and shame facial expressions, as well as contempt, relief, and triumph vocal expressions.[39][40][41]

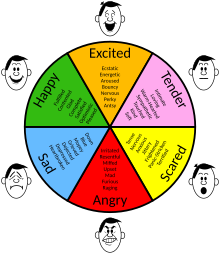

Robert Plutchik agreed with Ekman’s biologically driven perspective but developed the «wheel of emotions», suggesting eight primary emotions grouped on a positive or negative basis: joy versus sadness; anger versus fear; trust versus disgust; and surprise versus anticipation.[42] Some basic emotions can be modified to form complex emotions. The complex emotions could arise from cultural conditioning or association combined with the basic emotions. Alternatively, similar to the way primary colors combine, primary emotions could blend to form the full spectrum of human emotional experience. For example, interpersonal anger and disgust could blend to form contempt. Relationships exist between basic emotions, resulting in positive or negative influences.[43]

Jaak Panksepp carved out seven biologically inherited primary affective systems called SEEKING (expectancy), FEAR (anxiety), RAGE (anger), LUST (sexual excitement), CARE (nurturance), PANIC/GRIEF (sadness), and PLAY (social joy). He proposed what is known as «core-SELF» to be generating these affects.[44]

Multi-dimensional analysis[edit]

Two dimensions of emotions, made accessible for practical use[45]

Two dimensions of emotion

Psychologists have used methods such as factor analysis to attempt to map emotion-related responses onto a more limited number of dimensions. Such methods attempt to boil emotions down to underlying dimensions that capture the similarities and differences between experiences.[46] Often, the first two dimensions uncovered by factor analysis are valence (how negative or positive the experience feels) and arousal (how energized or enervated the experience feels). These two dimensions can be depicted on a 2D coordinate map.[4] This two-dimensional map has been theorized to capture one important component of emotion called core affect.[47][48] Core affect is not theorized to be the only component to emotion, but to give the emotion its hedonic and felt energy.

Using statistical methods to analyze emotional states elicited by short videos, Cowen and Keltner identified 27 varieties of emotional experience: admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire and surprise.[49]

Theories[edit]

Pre-modern history[edit]

In Buddhism, emotions occur when an object is considered as attractive or repulsive. There is a felt tendency impelling people towards attractive objects and impelling them to move away from repulsive or harmful objects; a disposition to possess the object (greed), to destroy it (hatred), to flee from it (fear), to get obsessed or worried over it (anxiety), and so on.[50]

In Stoic theories, normal emotions (like delight and fear) are described as irrational impulses which come from incorrect appraisals of what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Alternatively, there are ‘good emotions’ (like joy and caution) experienced by those that are wise, which come from correct appraisals of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’.[51][52]

Aristotle believed that emotions were an essential component of virtue.[53] In the Aristotelian view all emotions (called passions) corresponded to appetites or capacities. During the Middle Ages, the Aristotelian view was adopted and further developed by scholasticism and Thomas Aquinas[54] in particular.

In Chinese antiquity, excessive emotion was believed to cause damage to qi, which in turn, damages the vital organs.[55] The four humours theory made popular by Hippocrates contributed to the study of emotion in the same way that it did for medicine.

In the early 11th century, Avicenna theorized about the influence of emotions on health and behaviors, suggesting the need to manage emotions.[56]

Early modern views on emotion are developed in the works of philosophers such as René Descartes, Niccolò Machiavelli, Baruch Spinoza,[57] Thomas Hobbes[58] and David Hume. In the 19th century emotions were considered adaptive and were studied more frequently from an empiricist psychiatric perspective.

Western theological[edit]

Christian perspective on emotion presupposes a theistic origin to humanity. God who created humans gave humans the ability to feel emotion and interact emotionally. Biblical content expresses that God is a person who feels and expresses emotion. Though a somatic view would place the locus of emotions in the physical body, Christian theory of emotions would view the body more as a platform for the sensing and expression of emotions. Therefore, emotions themselves arise from the person, or that which is «imago-dei» or Image of God in humans. In Christian thought, emotions have the potential to be controlled through reasoned reflection. That reasoned reflection also mimics God who made mind. The purpose of emotions in human life are therefore summarized in God’s call to enjoy Him and creation, humans are to enjoy emotions and benefit from them and use them to energize behavior.[59][60]

Evolutionary theories[edit]

19th century[edit]

Perspectives on emotions from evolutionary theory were initiated during the mid-late 19th century with Charles Darwin’s 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.[61] Darwin argued that emotions served no evolved purpose for humans, neither in communication, nor in aiding survival.[62] Darwin largely argued that emotions evolved via the inheritance of acquired characters. He pioneered various methods for studying non-verbal expressions, from which he concluded that some expressions had cross-cultural universality. Darwin also detailed homologous expressions of emotions that occur in animals. This led the way for animal research on emotions and the eventual determination of the neural underpinnings of emotion.

Contemporary[edit]

More contemporary views along the evolutionary psychology spectrum posit that both basic emotions and social emotions evolved to motivate (social) behaviors that were adaptive in the ancestral environment.[63] Emotion is an essential part of any human decision-making and planning, and the famous distinction made between reason and emotion is not as clear as it seems.[64] Paul D. MacLean claims that emotion competes with even more instinctive responses, on one hand, and the more abstract reasoning, on the other hand. The increased potential in neuroimaging has also allowed investigation into evolutionarily ancient parts of the brain. Important neurological advances were derived from these perspectives in the 1990s by Joseph E. LeDoux and Antonio Damasio. For example, in an extensive study of a subject with ventromedial frontal lobe damage described in the book Descartes’ Error, Damasio demonstrated how loss of physiological capacity for emotion resulted in the subject’s lost capacity to make decisions despite having robust faculties for rationally assessing options.[65] Research on physiological emotion has caused modern neuroscience to abandon the model of emotions and rationality as opposing forces. In contrast to the ancient Greek ideal of dispassionate reason, the neuroscience of emotion shows that emotion is necessarily integrated with intellect.[66]

Research on social emotion also focuses on the physical displays of emotion including body language of animals and humans (see affect display). For example, spite seems to work against the individual but it can establish an individual’s reputation as someone to be feared.[63] Shame and pride can motivate behaviors that help one maintain one’s standing in a community, and self-esteem is one’s estimate of one’s status.[63][67][page needed]

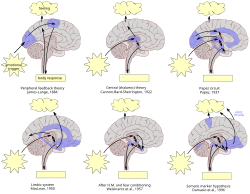

Somatic theories[edit]

Somatic theories of emotion claim that bodily responses, rather than cognitive interpretations, are essential to emotions. The first modern version of such theories came from William James in the 1880s. The theory lost favor in the 20th century, but has regained popularity more recently due largely to theorists such as John T. Cacioppo,[68] Antonio Damasio,[69] Joseph E. LeDoux[70] and Robert Zajonc[71] who are able to appeal to neurological evidence.[72]

James–Lange theory[edit]

In his 1884 article[73] William James argued that feelings and emotions were secondary to physiological phenomena. In his theory, James proposed that the perception of what he called an «exciting fact» directly led to a physiological response, known as «emotion.»[74] To account for different types of emotional experiences, James proposed that stimuli trigger activity in the autonomic nervous system, which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain. The Danish psychologist Carl Lange also proposed a similar theory at around the same time, and therefore this theory became known as the James–Lange theory. As James wrote, «the perception of bodily changes, as they occur, is the emotion.» James further claims that «we feel sad because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and either we cry, strike, or tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be.»[73]

An example of this theory in action would be as follows: An emotion-evoking stimulus (snake) triggers a pattern of physiological response (increased heart rate, faster breathing, etc.), which is interpreted as a particular emotion (fear). This theory is supported by experiments in which by manipulating the bodily state induces a desired emotional state.[75] Some people may believe that emotions give rise to emotion-specific actions, for example, «I’m crying because I’m sad,» or «I ran away because I was scared.» The issue with the James–Lange theory is that of causation (bodily states causing emotions and being a priori), not that of the bodily influences on emotional experience (which can be argued and is still quite prevalent today in biofeedback studies and embodiment theory).[76]

Although mostly abandoned in its original form, Tim Dalgleish argues that most contemporary neuroscientists have embraced the components of the James-Lange theory of emotions.[77]

The James–Lange theory has remained influential. Its main contribution is the emphasis it places on the embodiment of emotions, especially the argument that changes in the bodily concomitants of emotions can alter their experienced intensity. Most contemporary neuroscientists would endorse a modified James–Lange view in which bodily feedback modulates the experience of emotion. (p. 583)

Cannon–Bard theory[edit]

Walter Bradford Cannon agreed that physiological responses played a crucial role in emotions, but did not believe that physiological responses alone could explain subjective emotional experiences. He argued that physiological responses were too slow and often imperceptible and this could not account for the relatively rapid and intense subjective awareness of emotion.[78] He also believed that the richness, variety, and temporal course of emotional experiences could not stem from physiological reactions, that reflected fairly undifferentiated fight or flight responses.[79][80] An example of this theory in action is as follows: An emotion-evoking event (snake) triggers simultaneously both a physiological response and a conscious experience of an emotion.

Phillip Bard contributed to the theory with his work on animals. Bard found that sensory, motor, and physiological information all had to pass through the diencephalon (particularly the thalamus), before being subjected to any further processing. Therefore, Cannon also argued that it was not anatomically possible for sensory events to trigger a physiological response prior to triggering conscious awareness and emotional stimuli had to trigger both physiological and experiential aspects of emotion simultaneously.[79]

Two-factor theory[edit]

Stanley Schachter formulated his theory on the earlier work of a Spanish physician, Gregorio Marañón, who injected patients with epinephrine and subsequently asked them how they felt. Marañón found that most of these patients felt something but in the absence of an actual emotion-evoking stimulus, the patients were unable to interpret their physiological arousal as an experienced emotion. Schachter did agree that physiological reactions played a big role in emotions. He suggested that physiological reactions contributed to emotional experience by facilitating a focused cognitive appraisal of a given physiologically arousing event and that this appraisal was what defined the subjective emotional experience. Emotions were thus a result of two-stage process: general physiological arousal, and experience of emotion. For example, the physiological arousal, heart pounding, in a response to an evoking stimulus, the sight of a bear in the kitchen. The brain then quickly scans the area, to explain the pounding, and notices the bear. Consequently, the brain interprets the pounding heart as being the result of fearing the bear.[4] With his student, Jerome Singer, Schachter demonstrated that subjects can have different emotional reactions despite being placed into the same physiological state with an injection of epinephrine. Subjects were observed to express either anger or amusement depending on whether another person in the situation (a confederate) displayed that emotion. Hence, the combination of the appraisal of the situation (cognitive) and the participants’ reception of adrenaline or a placebo together determined the response. This experiment has been criticized in Jesse Prinz’s (2004) Gut Reactions.[81]

Cognitive theories[edit]

With the two-factor theory now incorporating cognition, several theories began to argue that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts were entirely necessary for an emotion to occur. One of the main proponents of this view was Richard Lazarus who argued that emotions must have some cognitive intentionality. The cognitive activity involved in the interpretation of an emotional context may be conscious or unconscious and may or may not take the form of conceptual processing.

Lazarus’ theory is very influential; emotion is a disturbance that occurs in the following order:

- Cognitive appraisal – The individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion.

- Physiological changes – The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response.

- Action – The individual feels the emotion and chooses how to react.

For example: Jenny sees a snake.

- Jenny cognitively assesses the snake in her presence. Cognition allows her to understand it as a danger.

- Her brain activates the adrenal glands which pump adrenaline through her blood stream, resulting in increased heartbeat.

- Jenny screams and runs away.

Lazarus stressed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes. These processes underline coping strategies that form the emotional reaction by altering the relationship between the person and the environment.

George Mandler provided an extensive theoretical and empirical discussion of emotion as influenced by cognition, consciousness, and the autonomic nervous system in two books (Mind and Emotion, 1975,[82] and Mind and Body: Psychology of Emotion and Stress, 1984[83])

There are some theories on emotions arguing that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts are necessary in order for an emotion to occur. A prominent philosophical exponent is Robert C. Solomon (for example, The Passions, Emotions and the Meaning of Life, 1993[84]). Solomon claims that emotions are judgments. He has put forward a more nuanced view which responds to what he has called the ‘standard objection’ to cognitivism, the idea that a judgment that something is fearsome can occur with or without emotion, so judgment cannot be identified with emotion. The theory proposed by Nico Frijda where appraisal leads to action tendencies is another example.

It has also been suggested that emotions (affect heuristics, feelings and gut-feeling reactions) are often used as shortcuts to process information and influence behavior.[85] The affect infusion model (AIM) is a theoretical model developed by Joseph Forgas in the early 1990s that attempts to explain how emotion and mood interact with one’s ability to process information.

- Perceptual theory

Theories dealing with perception either use one or multiples perceptions in order to find an emotion.[86] A recent hybrid of the somatic and cognitive theories of emotion is the perceptual theory. This theory is neo-Jamesian in arguing that bodily responses are central to emotions, yet it emphasizes the meaningfulness of emotions or the idea that emotions are about something, as is recognized by cognitive theories. The novel claim of this theory is that conceptually-based cognition is unnecessary for such meaning. Rather the bodily changes themselves perceive the meaningful content of the emotion because of being causally triggered by certain situations. In this respect, emotions are held to be analogous to faculties such as vision or touch, which provide information about the relation between the subject and the world in various ways. A sophisticated defense of this view is found in philosopher Jesse Prinz’s book Gut Reactions,[81] and psychologist James Laird’s book Feelings.[75]

- Affective events theory

Affective events theory is a communication-based theory developed by Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano (1996),[87] that looks at the causes, structures, and consequences of emotional experience (especially in work contexts). This theory suggests that emotions are influenced and caused by events which in turn influence attitudes and behaviors. This theoretical frame also emphasizes time in that human beings experience what they call emotion episodes – a «series of emotional states extended over time and organized around an underlying theme.» This theory has been used by numerous researchers to better understand emotion from a communicative lens, and was reviewed further by Howard M. Weiss and Daniel J. Beal in their article, «Reflections on Affective Events Theory», published in Research on Emotion in Organizations in 2005.[88]

Situated perspective on emotion[edit]

A situated perspective on emotion, developed by Paul E. Griffiths and Andrea Scarantino, emphasizes the importance of external factors in the development and communication of emotion, drawing upon the situationism approach in psychology.[89] This theory is markedly different from both cognitivist and neo-Jamesian theories of emotion, both of which see emotion as a purely internal process, with the environment only acting as a stimulus to the emotion. In contrast, a situationist perspective on emotion views emotion as the product of an organism investigating its environment, and observing the responses of other organisms. Emotion stimulates the evolution of social relationships, acting as a signal to mediate the behavior of other organisms. In some contexts, the expression of emotion (both voluntary and involuntary) could be seen as strategic moves in the transactions between different organisms. The situated perspective on emotion states that conceptual thought is not an inherent part of emotion, since emotion is an action-oriented form of skillful engagement with the world. Griffiths and Scarantino suggested that this perspective on emotion could be helpful in understanding phobias, as well as the emotions of infants and animals.

Genetics[edit]

Emotions can motivate social interactions and relationships and therefore are directly related with basic physiology, particularly with the stress systems. This is important because emotions are related to the anti-stress complex, with an oxytocin-attachment system, which plays a major role in bonding. Emotional phenotype temperaments affect social connectedness and fitness in complex social systems.[90] These characteristics are shared with other species and taxa and are due to the effects of genes and their continuous transmission. Information that is encoded in the DNA sequences provides the blueprint for assembling proteins that make up our cells. Zygotes require genetic information from their parental germ cells, and at every speciation event, heritable traits that have enabled its ancestor to survive and reproduce successfully are passed down along with new traits that could be potentially beneficial to the offspring.

In the five million years since the lineages leading to modern humans and chimpanzees split, only about 1.2% of their genetic material has been modified. This suggests that everything that separates us from chimpanzees must be encoded in that very small amount of DNA, including our behaviors. Students that study animal behaviors have only identified intraspecific examples of gene-dependent behavioral phenotypes. In voles (Microtus spp.) minor genetic differences have been identified in a vasopressin receptor gene that corresponds to major species differences in social organization and the mating system.[91] Another potential example with behavioral differences is the FOCP2 gene, which is involved in neural circuitry handling speech and language.[92] Its present form in humans differed from that of the chimpanzees by only a few mutations and has been present for about 200,000 years, coinciding with the beginning of modern humans.[93] Speech, language, and social organization are all part of the basis for emotions.

Formation[edit]

Neurobiological explanation[edit]

Based on discoveries made through neural mapping of the limbic system, the neurobiological explanation of human emotion is that emotion is a pleasant or unpleasant mental state organized in the limbic system of the mammalian brain. If distinguished from reactive responses of reptiles, emotions would then be mammalian elaborations of general vertebrate arousal patterns, in which neurochemicals (for example, dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin) step-up or step-down the brain’s activity level, as visible in body movements, gestures and postures. Emotions can likely be mediated by pheromones (see fear).[32]

For example, the emotion of love is proposed to be the expression of Paleocircuits of the mammalian brain (specifically, modules of the cingulate cortex (or gyrus)) which facilitate the care, feeding, and grooming of offspring. Paleocircuits are neural platforms for bodily expression configured before the advent of cortical circuits for speech. They consist of pre-configured pathways or networks of nerve cells in the forebrain, brainstem and spinal cord.

Other emotions like fear and anxiety long thought to be exclusively generated by the most primitive parts of the brain (stem) and more associated to the fight-or-flight responses of behavior, have also been associated as adaptive expressions of defensive behavior whenever a threat is encountered. Although defensive behaviors have been present in a wide variety of species, Blanchard et al. (2001) discovered a correlation of given stimuli and situation that resulted in a similar pattern of defensive behavior towards a threat in human and non-human mammals.[94]

Whenever potentially dangerous stimuli is presented additional brain structures activate that previously thought (hippocampus, thalamus, etc.). Thus, giving the amygdala an important role on coordinating the following behavioral input based on the presented neurotransmitters that respond to threat stimuli. These biological functions of the amygdala are not only limited to the «fear-conditioning» and «processing of aversive stimuli», but also are present on other components of the amygdala. Therefore, it can referred the amygdala as a key structure to understand the potential responses of behavior in danger like situations in human and non-human mammals.[95]

The motor centers of reptiles react to sensory cues of vision, sound, touch, chemical, gravity, and motion with pre-set body movements and programmed postures. With the arrival of night-active mammals, smell replaced vision as the dominant sense, and a different way of responding arose from the olfactory sense, which is proposed to have developed into mammalian emotion and emotional memory. The mammalian brain invested heavily in olfaction to succeed at night as reptiles slept – one explanation for why olfactory lobes in mammalian brains are proportionally larger than in the reptiles. These odor pathways gradually formed the neural blueprint for what was later to become our limbic brain.[32]

Emotions are thought to be related to certain activities in brain areas that direct our attention, motivate our behavior, and determine the significance of what is going on around us. Pioneering work by Paul Broca (1878),[96] James Papez (1937),[97] and Paul D. MacLean (1952)[98] suggested that emotion is related to a group of structures in the center of the brain called the limbic system, which includes the hypothalamus, cingulate cortex, hippocampi, and other structures. More recent research has shown that some of these limbic structures are not as directly related to emotion as others are while some non-limbic structures have been found to be of greater emotional relevance.

Prefrontal cortex[edit]

There is ample evidence that the left prefrontal cortex is activated by stimuli that cause positive approach.[99] If attractive stimuli can selectively activate a region of the brain, then logically the converse should hold, that selective activation of that region of the brain should cause a stimulus to be judged more positively. This was demonstrated for moderately attractive visual stimuli[100] and replicated and extended to include negative stimuli.[101]

Two neurobiological models of emotion in the prefrontal cortex made opposing predictions. The valence model predicted that anger, a negative emotion, would activate the right prefrontal cortex. The direction model predicted that anger, an approach emotion, would activate the left prefrontal cortex. The second model was supported.[102]

This still left open the question of whether the opposite of approach in the prefrontal cortex is better described as moving away (direction model), as unmoving but with strength and resistance (movement model), or as unmoving with passive yielding (action tendency model). Support for the action tendency model (passivity related to right prefrontal activity) comes from research on shyness[103] and research on behavioral inhibition.[104] Research that tested the competing hypotheses generated by all four models also supported the action tendency model.[105][106]

Homeostatic/primordial emotion[edit]

Another neurological approach proposed by Bud Craig in 2003 distinguishes two classes of emotion: «classical» emotions such as love, anger and fear that are evoked by environmental stimuli, and «homeostatic emotions» – attention-demanding feelings evoked by body states, such as pain, hunger and fatigue, that motivate behavior (withdrawal, eating or resting in these examples) aimed at maintaining the body’s internal milieu at its ideal state.[107]

Derek Denton calls the latter «primordial emotions» and defines them as «the subjective element of the instincts, which are the genetically programmed behavior patterns which contrive homeostasis. They include thirst, hunger for air, hunger for food, pain and hunger for specific minerals etc. There are two constituents of a primordial emotion – the specific sensation which when severe may be imperious, and the compelling intention for gratification by a consummatory act.»[108]

Emergent explanation[edit]

Emotions are seen by some researchers to be constructed (emerge) in social and cognitive domain alone, without directly implying biologically inherited characteristics.

Joseph LeDoux differentiates between the human’s defense system, which has evolved over time, and emotions such as fear and anxiety. He has said that the amygdala may release hormones due to a trigger (such as an innate reaction to seeing a snake), but «then we elaborate it through cognitive and conscious processes».[31]

Lisa Feldman Barrett highlights differences in emotions between different cultures, and says that emotions (such as anxiety) are socially constructed (see theory of constructed emotion). She says that they «are not triggered; you create them. They emerge as a combination of the physical properties of your body, a flexible brain that wires itself to whatever environment it develops in, and your culture and upbringing, which provide that environment.»[109] She has termed this approach the theory of constructed emotion.

Disciplinary approaches[edit]

Many different disciplines have produced work on the emotions. Human sciences study the role of emotions in mental processes, disorders, and neural mechanisms. In psychiatry, emotions are examined as part of the discipline’s study and treatment of mental disorders in humans. Nursing studies emotions as part of its approach to the provision of holistic health care to humans. Psychology examines emotions from a scientific perspective by treating them as mental processes and behavior and they explore the underlying physiological and neurological processes, e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy. In neuroscience sub-fields such as social neuroscience and affective neuroscience, scientists study the neural mechanisms of emotion by combining neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. In linguistics, the expression of emotion may change to the meaning of sounds. In education, the role of emotions in relation to learning is examined.

Social sciences often examine emotion for the role that it plays in human culture and social interactions. In sociology, emotions are examined for the role they play in human society, social patterns and interactions, and culture. In anthropology, the study of humanity, scholars use ethnography to undertake contextual analyses and cross-cultural comparisons of a range of human activities. Some anthropology studies examine the role of emotions in human activities. In the field of communication studies, critical organizational scholars have examined the role of emotions in organizations, from the perspectives of managers, employees, and even customers. A focus on emotions in organizations can be credited to Arlie Russell Hochschild’s concept of emotional labor. The University of Queensland hosts EmoNet,[110] an e-mail distribution list representing a network of academics that facilitates scholarly discussion of all matters relating to the study of emotion in organizational settings. The list was established in January 1997 and has over 700 members from across the globe.

In economics, the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, emotions are analyzed in some sub-fields of microeconomics, in order to assess the role of emotions on purchase decision-making and risk perception. In criminology, a social science approach to the study of crime, scholars often draw on behavioral sciences, sociology, and psychology; emotions are examined in criminology issues such as anomie theory and studies of «toughness,» aggressive behavior, and hooliganism. In law, which underpins civil obedience, politics, economics and society, evidence about people’s emotions is often raised in tort law claims for compensation and in criminal law prosecutions against alleged lawbreakers (as evidence of the defendant’s state of mind during trials, sentencing, and parole hearings). In political science, emotions are examined in a number of sub-fields, such as the analysis of voter decision-making.

In philosophy, emotions are studied in sub-fields such as ethics, the philosophy of art (for example, sensory–emotional values, and matters of taste and sentimentality), and the philosophy of music (see also music and emotion). In history, scholars examine documents and other sources to interpret and analyze past activities; speculation on the emotional state of the authors of historical documents is one of the tools of interpretation. In literature and film-making, the expression of emotion is the cornerstone of genres such as drama, melodrama, and romance. In communication studies, scholars study the role that emotion plays in the dissemination of ideas and messages. Emotion is also studied in non-human animals in ethology, a branch of zoology which focuses on the scientific study of animal behavior. Ethology is a combination of laboratory and field science, with strong ties to ecology and evolution. Ethologists often study one type of behavior (for example, aggression) in a number of unrelated animals.

History of emotions[edit]

The history of emotions has become an increasingly popular topic recently, with some scholars[who?] arguing that it is an essential category of analysis, not unlike class, race, or gender. Historians, like other social scientists, assume that emotions, feelings and their expressions are regulated in different ways by both different cultures and different historical times, and the constructivist school of history claims even that some sentiments and meta-emotions, for example schadenfreude, are learnt and not only regulated by culture. Historians of emotion trace and analyze the changing norms and rules of feeling, while examining emotional regimes, codes, and lexicons from social, cultural, or political history perspectives. Others focus on the history of medicine, science, or psychology. What somebody can and may feel (and show) in a given situation, towards certain people or things, depends on social norms and rules; thus historically variable and open to change.[111] Several research centers have opened in the past few years in Germany, England, Spain,[112] Sweden, and Australia.

Furthermore, research in historical trauma suggests that some traumatic emotions can be passed on from parents to offspring to second and even third generation, presented as examples of transgenerational trauma.

Sociology[edit]

A common way in which emotions are conceptualized in sociology is in terms of the multidimensional characteristics including cultural or emotional labels (for example, anger, pride, fear, happiness), physiological changes (for example, increased perspiration, changes in pulse rate), expressive facial and body movements (for example, smiling, frowning, baring teeth), and appraisals of situational cues.[11] One comprehensive theory of emotional arousal in humans has been developed by Jonathan Turner (2007: 2009).[113][114] Two of the key eliciting factors for the arousal of emotions within this theory are expectations states and sanctions. When people enter a situation or encounter with certain expectations for how the encounter should unfold, they will experience different emotions depending on the extent to which expectations for Self, other and situation are met or not met. People can also provide positive or negative sanctions directed at Self or other which also trigger different emotional experiences in individuals. Turner analyzed a wide range of emotion theories across different fields of research including sociology, psychology, evolutionary science, and neuroscience. Based on this analysis, he identified four emotions that all researchers consider being founded on human neurology including assertive-anger, aversion-fear, satisfaction-happiness, and disappointment-sadness. These four categories are called primary emotions and there is some agreement amongst researchers that these primary emotions become combined to produce more elaborate and complex emotional experiences. These more elaborate emotions are called first-order elaborations in Turner’s theory and they include sentiments such as pride, triumph, and awe. Emotions can also be experienced at different levels of intensity so that feelings of concern are a low-intensity variation of the primary emotion aversion-fear whereas depression is a higher intensity variant.

Attempts are frequently made to regulate emotion according to the conventions of the society and the situation based on many (sometimes conflicting) demands and expectations which originate from various entities. The expression of anger is in many cultures discouraged in girls and women to a greater extent than in boys and men (the notion being that an angry man has a valid complaint that needs to be rectified, while an angry women is hysterical or oversensitive, and her anger is somehow invalid), while the expression of sadness or fear is discouraged in boys and men relative to girls and women (attitudes implicit in phrases like «man up» or «don’t be a sissy»).[115][116] Expectations attached to social roles, such as «acting as man» and not as a woman, and the accompanying «feeling rules» contribute to the differences in expression of certain emotions. Some cultures encourage or discourage happiness, sadness, or jealousy, and the free expression of the emotion of disgust is considered socially unacceptable in most cultures. Some social institutions are seen as based on certain emotion, such as love in the case of contemporary institution of marriage. In advertising, such as health campaigns and political messages, emotional appeals are commonly found. Recent examples include no-smoking health campaigns and political campaigns emphasizing the fear of terrorism.[117]

Sociological attention to emotion has varied over time. Émile Durkheim (1915/1965)[118] wrote about the collective effervescence or emotional energy that was experienced by members of totemic rituals in Australian Aboriginal society. He explained how the heightened state of emotional energy achieved during totemic rituals transported individuals above themselves giving them the sense that they were in the presence of a higher power, a force, that was embedded in the sacred objects that were worshipped. These feelings of exaltation, he argued, ultimately lead people to believe that there were forces that governed sacred objects.

In the 1990s, sociologists focused on different aspects of specific emotions and how these emotions were socially relevant. For Cooley (1992),[119] pride and shame were the most important emotions that drive people to take various social actions. During every encounter, he proposed that we monitor ourselves through the «looking glass» that the gestures and reactions of others provide. Depending on these reactions, we either experience pride or shame and this results in particular paths of action. Retzinger (1991)[120] conducted studies of married couples who experienced cycles of rage and shame. Drawing predominantly on Goffman and Cooley’s work, Scheff (1990)[121] developed a micro sociological theory of the social bond. The formation or disruption of social bonds is dependent on the emotions that people experience during interactions.

Subsequent to these developments, Randall Collins (2004)[122] formulated his interaction ritual theory by drawing on Durkheim’s work on totemic rituals that was extended by Goffman (1964/2013; 1967)[123][124] into everyday focused encounters. Based on interaction ritual theory, we experience different levels or intensities of emotional energy during face-to-face interactions. Emotional energy is considered to be a feeling of confidence to take action and a boldness that one experiences when they are charged up from the collective effervescence generated during group gatherings that reach high levels of intensity.

There is a growing body of research applying the sociology of emotion to understanding the learning experiences of students during classroom interactions with teachers and other students (for example, Milne & Otieno, 2007;[125] Olitsky, 2007;[126] Tobin, et al., 2013;[127] Zembylas, 2002[128]). These studies show that learning subjects like science can be understood in terms of classroom interaction rituals that generate emotional energy and collective states of emotional arousal like emotional climate.

Apart from interaction ritual traditions of the sociology of emotion, other approaches have been classed into one of six other categories:[114]

- evolutionary/biological theories

- symbolic interactionist theories

- dramaturgical theories

- ritual theories

- power and status theories

- stratification theories

- exchange theories

This list provides a general overview of different traditions in the sociology of emotion that sometimes conceptualise emotion in different ways and at other times in complementary ways. Many of these different approaches were synthesized by Turner (2007) in his sociological theory of human emotions in an attempt to produce one comprehensive sociological account that draws on developments from many of the above traditions.[113]

Psychotherapy and regulation[edit]

Emotion regulation refers to the cognitive and behavioral strategies people use to influence their own emotional experience.[129] For example, a behavioral strategy in which one avoids a situation to avoid unwanted emotions (trying not to think about the situation, doing distracting activities, etc.).[130] Depending on the particular school’s general emphasis on either cognitive components of emotion, physical energy discharging, or on symbolic movement and facial expression components of emotion different schools of psychotherapy approach the regulation of emotion differently. Cognitively oriented schools approach them via their cognitive components, such as rational emotive behavior therapy. Yet others approach emotions via symbolic movement and facial expression components (like in contemporary Gestalt therapy).[131]

Cross-cultural research[edit]

Research on emotions reveals the strong presence of cross-cultural differences in emotional reactions and that emotional reactions are likely to be culture-specific.[132] In strategic settings, cross-cultural research on emotions is required for understanding the psychological situation of a given population or specific actors. This implies the need to comprehend the current emotional state, mental disposition or other behavioral motivation of a target audience located in a different culture, basically founded on its national, political, social, economic, and psychological peculiarities but also subject to the influence of circumstances and events.[133]

Computer science[edit]

In the 2000s, research in computer science, engineering, psychology and neuroscience has been aimed at developing devices that recognize human affect display and model emotions.[134] In computer science, affective computing is a branch of the study and development of artificial intelligence that deals with the design of systems and devices that can recognize, interpret, and process human emotions. It is an interdisciplinary field spanning computer sciences, psychology, and cognitive science.[135] While the origins of the field may be traced as far back as to early philosophical enquiries into emotion,[73] the more modern branch of computer science originated with Rosalind Picard’s 1995 paper[136] on affective computing.[137][138] Detecting emotional information begins with passive sensors which capture data about the user’s physical state or behavior without interpreting the input. The data gathered is analogous to the cues humans use to perceive emotions in others. Another area within affective computing is the design of computational devices proposed to exhibit either innate emotional capabilities or that are capable of convincingly simulating emotions. Emotional speech processing recognizes the user’s emotional state by analyzing speech patterns. The detection and processing of facial expression or body gestures is achieved through detectors and sensors.

The effects on memory[edit]

Emotion affects the way autobiographical memories are encoded and retrieved. Emotional memories are reactivated more, they are remembered better and have more attention devoted to them.[139] Through remembering our past achievements and failures, autobiographical memories affect how we perceive and feel about ourselves.[139]

Notable theorists[edit]

In the late 19th century, the most influential theorists were William James (1842–1910) and Carl Lange (1834–1900). James was an American psychologist and philosopher who wrote about educational psychology, psychology of religious experience/mysticism, and the philosophy of pragmatism. Lange was a Danish physician and psychologist. Working independently, they developed the James–Lange theory, a hypothesis on the origin and nature of emotions. The theory states that within human beings, as a response to experiences in the world, the autonomic nervous system creates physiological events such as muscular tension, a rise in heart rate, perspiration, and dryness of the mouth. Emotions, then, are feelings which come about as a result of these physiological changes, rather than being their cause.[140]

Silvan Tomkins (1911–1991) developed the affect theory and script theory. The affect theory introduced the concept of basic emotions, and was based on the idea that the dominance of the emotion, which he called the affected system, was the motivating force in human life.[141]

Some of the most influential deceased theorists on emotion from the 20th century include Magda B. Arnold (1903–2002), an American psychologist who developed the appraisal theory of emotions;[142] Richard Lazarus (1922–2002), an American psychologist who specialized in emotion and stress, especially in relation to cognition; Herbert A. Simon (1916–2001), who included emotions into decision making and artificial intelligence; Robert Plutchik (1928–2006), an American psychologist who developed a psychoevolutionary theory of emotion;[143] Robert Zajonc (1923–2008) a Polish–American social psychologist who specialized in social and cognitive processes such as social facilitation; Robert C. Solomon (1942–2007), an American philosopher who contributed to the theories on the philosophy of emotions with books such as What Is An Emotion?: Classic and Contemporary Readings (2003);[144] Peter Goldie (1946–2011), a British philosopher who specialized in ethics, aesthetics, emotion, mood and character; Nico Frijda (1927–2015), a Dutch psychologist who advanced the theory that human emotions serve to promote a tendency to undertake actions that are appropriate in the circumstances, detailed in his book The Emotions (1986);[145] Jaak Panksepp (1943–2017), an Estonian-born American psychologist, psychobiologist, neuroscientist and pioneer in affective neuroscience.

Influential theorists who are still active include the following psychologists, neurologists, philosophers, and sociologists:

- Michael Apter – (born 1939) British psychologist who developed reversal theory, a structural, phenomenological theory of personality, motivation, and emotion

- Lisa Feldman Barrett – (born 1963) neuroscientist and psychologist specializing in affective science and human emotion

- John T. Cacioppo – (born 1951) from the University of Chicago, founding father with Gary Berntson of social neuroscience

- Randall Collins – (born 1941) American sociologist from the University of Pennsylvania developed the interaction ritual theory which includes the emotional entrainment model

- Antonio Damasio (born 1944) – Portuguese behavioral neurologist and neuroscientist who works in the US

- Richard Davidson (born 1951) – American psychologist and neuroscientist; pioneer in affective neuroscience

- Paul Ekman (born 1934) – psychologist specializing in the study of emotions and their relation to facial expressions

- Barbara Fredrickson – Social psychologist who specializes in emotions and positive psychology.

- Arlie Russell Hochschild (born 1940) – American sociologist whose central contribution was in forging a link between the subcutaneous flow of emotion in social life and the larger trends set loose by modern capitalism within organizations

- Joseph E. LeDoux (born 1949) – American neuroscientist who studies the biological underpinnings of memory and emotion, especially the mechanisms of fear

- George Mandler (born 1924) – American psychologist who wrote influential books on cognition and emotion

- Jesse Prinz – American philosopher who specializes in emotion, moral psychology, aesthetics and consciousness

- James A. Russell (born 1947) – American psychologist who developed or co-developed the PAD theory of environmental impact, circumplex model of affect, prototype theory of emotion concepts, a critique of the hypothesis of universal recognition of emotion from facial expression, concept of core affect, developmental theory of differentiation of emotion concepts, and, more recently, the theory of the psychological construction of emotion

- Klaus Scherer (born 1943) – Swiss psychologist and director of the Swiss Center for Affective Sciences in Geneva; he specializes in the psychology of emotion

- Ronald de Sousa (born 1940) – English–Canadian philosopher who specializes in the philosophy of emotions, philosophy of mind and philosophy of biology

- Jonathan H. Turner (born 1942) – American sociologist from the University of California, Riverside, who is a general sociological theorist with specialty areas including the sociology of emotions, ethnic relations, social institutions, social stratification, and bio-sociology

- Dominique Moïsi (born 1946) – authored a book titled The Geopolitics of Emotion focusing on emotions related to globalization[146]

See also[edit]

- Affect measures

- Affective forecasting

- Emotion and memory

- Emotion Review

- Emotional intelligence

- Emotional isolation

- Emotions in virtual communication

- Facial feedback hypothesis

- Fuzzy-trace theory

- Group emotion

- Moral emotions

- Social sharing of emotions

- Two-factor theory of emotion

References[edit]

- ^ Panksepp, Jaak (2005). Affective neuroscience: the foundations of human and animal emotions ([Reprint] ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0195096736.

Our emotional feelings reflect our ability to subjectively experience certain states of the nervous system. Although conscious feeling states are universally accepted as major distinguishing characteristics of human emotions, in animal research the issue of whether other organisms feel emotions is little more than a conceptual embarrassment

- ^ Damasio AR (May 1998). «Emotion in the perspective of an integrated nervous system». Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 26 (2–3): 83–86. doi:10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00064-7. PMID 9651488. S2CID 8504450.

- ^ Ekman, Paul; Davidson, Richard J. (1994). The Nature of emotion: fundamental questions. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-0195089448.

Emotional processing, but not emotions, can occur unconsciously.

- ^ a b c d Schacter, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel T.; Wegner, Daniel M. (2011). Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. p. 310. ISBN 978-1429237192.

- ^ Cabanac, Michel (2002). «What is emotion?». Behavioural Processes. 60 (2): 69–83. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(02)00078-5. PMID 12426062. S2CID 24365776.

There is no consensus in the literature on a definition of emotion. The term is taken for granted in itself and, most often, emotion is defined with reference to a list: anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, and surprise. […] I propose here that emotion is any mental experience with high intensity and high hedonic content (pleasure/displeasure).

- ^ Lisa Feldman Barrett; Michael Lewis; Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones, eds. (2016). Handbook of emotions (Fourth ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1462525348. OCLC 950202673.

- ^ Averill, James R. (February 1999). «Individual Differences in Emotional Creativity: Structure and Correlates». Journal of Personality. 67 (2): 331–371. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00058. ISSN 0022-3506. PMID 10202807.

- ^ Cacioppo, John T.; Gardner, Wendi L. (1999). «Emotion». Annual Review of Psychology. 50: 191–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.191. PMID 10074678.

- ^ a b Cabral, J. Centurion; de Almeida, Rosa Maria Martins (2022). «From social status to emotions: Asymmetric contests predict emotional responses to victory and defeat». Emotion. 22 (4): 769–779. doi:10.1037/emo0000839. ISSN 1931-1516. PMID 32628033. S2CID 220371464.

- ^ a b Scherer KR (2005). «What are emotions? And how can they be measured?». Social Science Information. 44 (4): 693–727. doi:10.1177/0539018405058216. S2CID 145575751.

- ^ a b Thoits PA (1989). «The sociology of emotions». Annual Review of Sociology. 15: 317–342. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.15.1.317.

- ^ Barrett LF, Mesquita B, Ochsner KN, Gross JJ (January 2007). «The experience of emotion». Annual Review of Psychology. 58 (1): 373–403. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085709. PMC 1934613. PMID 17002554.

- ^ Reitsema, A.M. (2021). «Emotion dynamics in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic and descriptive review». Emotion. 22 (2): 374–396. doi:10.1037/emo0000970. PMID 34843305. S2CID 244748515.

- ^ Dixon, Thomas. From passions to emotions: the creation of a secular psychological category. Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0521026697. link Archived 9 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Smith TW (2015). The Book of Human Emotions. Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0316265409.

- ^ Russell JA (November 1991). «Culture and the categorization of emotions». Psychological Bulletin. 110 (3): 426–450. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.426. PMID 1758918. S2CID 4830394.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna. Emotions across languages and cultures: diversity and universals. Cambridge University Press. 1999.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Taylor, Graeme J. (June 1984). «Alexithymia: concept, measurement, and implications for treatment». American Journal of Psychiatry. 141 (6): 725–732. doi:10.1176/ajp.141.6.725. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 6375397.

- ^ Kagan, Jerome (2007). What is emotion?: History, measures, and meanings. Yale University Press. pp. 10, 11.

- ^ Mossner, Ernest Campbell (2001). The Life of David Hume. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-199-24336-5.

- ^ Hume, David (2003). A treatise of human nature. Courier Corporation.[ISBN missing]

- ^ «Emotion | Definition of Emotion by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Emotion». Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Schacter, D.L., Gilbert, D.T., Wegner, D.M., & Hood, B.M. (2011). Psychology (European ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ «Emotion». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2018. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Graham MC (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1478722595.

- ^ Graham MC (2014). Facts of Life: Ten Issues of Contentment. Outskirts Press. ISBN 978-1478722595.

- ^ a b Fox E (2008). Emotion Science: An Integration of Cognitive and Neuroscientific Approaches. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0230005174.

- ^ Graham MC (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. ISBN 978-1478722595.

- ^ a b Hume, D. Emotions and Moods. Organizational Behavior, 258–97.

- ^ Fehr B, Russell JA (1984). «Concept of Emotion Viewed from a Prototype Perspective». Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 113 (3): 464–486. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.464.

- ^ a b «On Fear, Emotions, and Memory: An Interview with Dr. Joseph LeDoux – Page 2 of 2 – Brain World». 6 June 2018. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Givens DB. «Emotion». Center for Nonverbal Studies. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ Ekman P (1992). «An argument for basic emotions» (PDF). Cognition & Emotion. 6 (3): 169–200. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.1984. doi:10.1080/02699939208411068. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ «Listening to Your Authentic Self: The Purpose of Emotions». HuffPost. 21 October 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Some people regard mental illnesses as having evolutionary value, see e.g. evolutionary approaches to depression.

- ^ Schwarz, N.H. (1990). «Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states». Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior, 2, 527–561.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Shiota, Michelle N. (2016). «Ekman’s theory of basic emotions». In Miller, Harold L. (ed.). The Sage encyclopedia of theory in psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. pp. 248–250. doi:10.4135/9781483346274.n85. ISBN 978-1452256719.

Some aspects of Ekman’s approach to basic emotions are commonly misunderstood. Three misinterpretations are especially common. The first and most widespread is that Ekman posits exactly six basic emotions. Although his original facial-expression research examined six emotions, Ekman has often written that evidence may eventually be found for several more and has suggested as many as 15 likely candidates.

- ^ Ekman, Paul; Cordaro, Daniel (20 September 2011). «What is Meant by Calling Emotions Basic». Emotion Review. 3 (4): 364–370. doi:10.1177/1754073911410740. ISSN 1754-0739. S2CID 52833124.

- ^ Cordaro, Daniel T.; Keltner, Dacher; Tshering, Sumjay; Wangchuk, Dorji; Flynn, Lisa M. (2016). «The voice conveys emotion in ten globalized cultures and one remote village in Bhutan». Emotion. 16 (1): 117–128. doi:10.1037/emo0000100. ISSN 1931-1516. PMID 26389648.

- ^ Cordaro, Daniel T.; Sun, Rui; Keltner, Dacher; Kamble, Shanmukh; Huddar, Niranjan; McNeil, Galen (February 2018). «Universals and cultural variations in 22 emotional expressions across five cultures». Emotion. 18 (1): 75–93. doi:10.1037/emo0000302. ISSN 1931-1516. PMID 28604039. S2CID 3436764.

- ^ Keltner, Dacher; Oatley, Keith; Jenkins, Jennifer M (2019). Understanding emotions. ISBN 978-1119492535. OCLC 1114474792.[page needed]

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (2000). Emotions in the practice of psychotherapy: clinical implications of affect theories. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10366-000. ISBN 1557986940. OCLC 44110498.

- ^ Plutchik R (2002). «Nature of emotions». American Scientist. 89 (4): 349. doi:10.1511/2001.28.739.

- ^ Panksepp, Jaak; Biven, Lucy (2012). The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotions (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393707311. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Scherer, Klaus R.; Shuman, Vera; Fontaine, Johnny R. J.; Soriano, Cristina (2013), «The GRID meets the Wheel: Assessing emotional feeling via self-report1», Components of Emotional Meaning, Oxford University Press, pp. 281–298, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199592746.003.0019, ISBN 978-0199592746, archived from the original on 29 January 2020, retrieved 20 December 2019

- ^ Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH (1957). The Measurement of Meaning. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252745393.[page needed]

- ^ Russell JA, Barrett LF (May 1999). «Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: dissecting the elephant». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (5): 805–819. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.805. PMID 10353204.

- ^ Russell JA (January 2003). «Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion». Psychological Review. 110 (1): 145–172. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.6245. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.145. PMID 12529060.

- ^ Cowen AS, Keltner D (2017). «Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. National Academy of Sciences. 114 (38): E7900–7909. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E7900C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702247114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5617253. PMID 28874542.

- ^ de Silva P (1976). The Psychology of Emotions in Buddhist Perspective. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Arius Didymus. «Epitome of Stoic Ethics» in the Anthology of Stobaeus. Book 2. Chapter 7. Section 10. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Cicero. Tusculan Disputations. Book 4. Section 6. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Book 2. Chapter 6. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Aquinas T. Summa Theologica. Q.59, Art.2. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Suchy Y (2011). Clinical neuropsychology of emotion. New York: Guilford.

- ^ Haque A (2004). «Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists». Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z. JSTOR 27512819. S2CID 38740431.

- ^ See for instance Antonio Damasio (2005) Looking for Spinoza.

- ^ Leviathan (1651), VI: Of the Interior Beginnings of Voluntary Notions, Commonly called the Passions; and the Speeches by which They are Expressed

- ^ Roberts, Robert (10 March 2021). «Emotions in the Christian Tradition». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Department of Philosophy, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Robert (2007). Spiritual Emotions: A Psychology of Christian Virtues. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0802827401. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1872). The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. Note: This book was originally published in 1872, but has been reprinted many times thereafter by different publishers

- ^ Hess, Ursula; Thibault (2009). «Darwin & Emotion Expression». The Principle of Serviceable Habits. American Psychologist. 64 (2): 120–128. doi:10.1037/a0013386. PMID 19203144. S2CID 31276371.

for most emotion expressions, Darwin insisted that they were functional in the past or were functional in animals but not in humans.

- ^ a b c Gaulin, Steven J.C. and Donald H. McBurney (2003). Evolutionary Psychology. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0131115293, Chapter 6, pp. 121–142.

- ^ Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, Kassam KS (January 2015). «Emotion and decision making» (PDF). Annual Review of Psychology. 66: 799–823. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043. PMID 25251484. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Damásio, António (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-13894-3.

- ^ de Waal, Frans (2019). Mama’s Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us about Ourselves. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-63506-5.

- ^ Wright, Robert (1994). The Moral Animal. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-76399-6. OCLC 33496013.

- ^ Cacioppo JT (1998). «Somatic responses to psychological stress: The reactivity hypothesis». Advances in Psychological Science. 2: 87–114.

- ^ Aziz-Zadeh L, Damasio A (2008). «Embodied semantics for actions: findings from functional brain imaging». Journal of Physiology, Paris. 102 (1–3): 35–39. doi:10.1016/j.jphysparis.2008.03.012. PMID 18472250. S2CID 44371175.

- ^ LeDoux J.E. (1996) The Emotional Brain. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ McIntosh DN, Zajonc RB, Vig PB, Emerick SW (1997). «Facial movement, breathing, temperature, and affect: Implications of the vascular theory of emotional efference». Cognition & Emotion. 11 (2): 171–95. doi:10.1080/026999397379980.

- ^ Pace-Schott EF, Amole MC, Aue T, Balconi M, Bylsma LM, Critchley H, et al. (August 2019). «Physiological feelings». Theories of emotion & physiology. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 103: 267–304. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.002. PMID 31125635.

Currently the predominant opinion is that somatovisceral and central nervous responses associated with an emotion serve to prepare situationally adaptive behavioral responses.

- ^ a b c James W (1884). «What Is an Emotion?». Mind. 9 (34): 188–205. doi:10.1093/mind/os-ix.34.188. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Carlson N (2012). Physiology of Behavior. Emotion. Vol. 11th edition. Pearson. p. 388. ISBN 978-0205239399.

- ^ a b Laird, James, Feelings: the Perception of Self, Oxford University Press

- ^ Reisenzein R (1995). «James and the physical basis of emotion: A comment on Ellsworth». Psychological Review. 102 (4): 757–761. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.102.4.757.

- ^ Dalgleish T (2004). «The emotional brain». Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 5 (7): 582–589. doi:10.1038/nrn1432. PMID 15208700. S2CID 148864726.

- ^ Carlson N (2012). Physiology of Behavior. Emotion (11th ed.). Pearson. p. 389. ISBN 978-0205239399.

- ^ a b Cannon WB (1929). «Organization for Physiological Homeostasis». Physiological Reviews. 9 (3): 399–421. doi:10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399. S2CID 87128623.

- ^ Cannon WB (1927). «The James-Lange theory of emotion: A critical examination and an alternative theory». The American Journal of Psychology. 39 (1/4): 106–124. doi:10.2307/1415404. JSTOR 1415404. S2CID 27900216.

- ^ a b Prinz, Jesse J. (2004). Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195348590.[page needed]

- ^ Mandler, George (1975). Mind and Emotion. Malabar: R.E. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0898743500.

- ^ Mandler, George (1984). Mind and Body: Psychology of Emotion and Stress. New York: W.W. Norton. OCLC 797330039.

- ^ Solomon, Robert C. (1993). The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 0872202267.

- ^ see the Heuristic–Systematic Model, or HSM, (Chaiken, Liberman, & Eagly, 1989) under attitude change. Also see the index entry for «Emotion» in «Beyond Rationality: The Search for Wisdom in a Troubled Time» by Kenneth R. Hammond and in «Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets» by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

- ^ Goldie, Peter (2007). «Emotion». Philosophy Compass. 1 (6): 6. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2007.00105.x.

- ^ Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. (1996). Affective events theory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 8: 1±74

- ^ Howard M Weiss; Daniel J Beal (June 2005). reflections on affective events theory. Emotion. Research on Emotion in Organizations. Vol. 1. pp. 1–21. doi:10.1016/S1746-9791(05)01101-6. ISBN 978-0762312344.