«Market forces» redirects here. For the novel by Richard Morgan, see Market Forces. For other uses, see Market.

In economics, a market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering their goods or services (including labour power) to buyers in exchange for money. It can be said that a market is the process by which the prices of goods and services are established. Markets facilitate trade and enable the distribution and allocation of resources in a society. Markets allow any tradeable item to be evaluated and priced. A market emerges more or less spontaneously or may be constructed deliberately by human interaction in order to enable the exchange of rights (cf. ownership) of services and goods. Markets generally supplant gift economies and are often held in place through rules and customs, such as a booth fee, competitive pricing, and source of goods for sale (local produce or stock registration).

Markets can differ by products (goods, services) or factors (labour and capital) sold, product differentiation, place in which exchanges are carried, buyers targeted, duration, selling process, government regulation, taxes, subsidies, minimum wages, price ceilings, legality of exchange, liquidity, intensity of speculation, size, concentration, exchange asymmetry, relative prices, volatility and geographic extension. The geographic boundaries of a market may vary considerably, for example the food market in a single building, the real estate market in a local city, the consumer market in an entire country, or the economy of an international trade bloc where the same rules apply throughout. Markets can also be worldwide, see for example the global diamond trade. National economies can also be classified as developed markets or developing markets.

In mainstream economics, the concept of a market is any structure that allows buyers and sellers to exchange any type of goods, services and information. The exchange of goods or services, with or without money, is a transaction.[1] The main parties of a market consist of all the buyers and sellers of a good who influence its price, which is a major topic of study of economics and has given rise to several theories and models concerning the basic market forces of supply and demand. A major topic of debate is how much a given market can be considered to be a «free market», that is free from government intervention. Microeconomics traditionally focuses on the study of market structure and the efficiency of market equilibrium; when the latter (if it exists) is not efficient, then economists say that a market failure has occurred. However, it is not always clear how the allocation of resources can be improved since there is always the possibility of government failure.

Definition[edit]

In economics, a market is a coordinating mechanism that uses prices to convey information among economic entities (such as firms, households and individuals) to regulate production and distribution. In his seminal 1937 article «The Nature of the Firm», Ronald Coase wrote: «An economist thinks of the economic system as being coordinated by the price mechanism….in economic theory we find that the allocation of factors of production between different uses is determined by the price mechanism».[2] Thus the usage of the price mechanism to convey information is the defining feature of the market. This is in contrast to a firm, which as Coase put it, «the distinguishing mark of the firm is the super-session of the price mechanism».[2]

Thus, Firms and Markets are two opposite forms of organizing production; Coase wrote:[2]

Outside the firm, price movements direct production, which is co-ordinated through a series of exchange transactions on the market. Within a firm, these market transactions are eliminated and in place of the complicated market structure with exchange transactions is substituted the entrepreneur-co-ordinator, who directs production.

There are also other hybrid forms of coordinating mechanisms, in between the hierarchical firm and price-coordinating market(e.g. global value chains, Business Ventures, Joint Venture, and strategic alliances).

The reasons for the existence of firms or other forms of co-ordinating mechanisms of production and distribution alongside the market are studied in «The Theory of the Firm» literature, with various complete and incomplete contract theories trying to explain the existence of the firm. Incomplete contract theories that are explicitly based on bounded rationality lead to the costs of writing complete contracts. Such theories include: Transaction Cost Economies [3] by Oliver Williamson and Residual Rights Theory[4] by Groomsman, Hart, and Moore.

Market-Firms’s dichotomy can be contrasted with the relationship between the agents transacting. While in a market the relationship is short term and restricted to the contract, in the case of firms and other co-ordinating mechanisms it is for a longer duration.[5]

In the modern world much economic activity takes place through fiat and not the market. Lafontaine and Slade (2007) estimates, in the US, that the total value added in transactions inside the firms equal the total value added of all market transactions.[6] Similarly, 80% of all World Trade is conducted under Global Value Chains (2012 estimate), while 33% (1996 estimate) is intra-firm trade.[7][8] Nearly 50% of US imports and 30% of exports take place within firms.[9] While Rajan and Zingales (1998) have found that in 43 countries two-thirds of the growth in value added between 1980 and 1990 came from increase in firm size.[10]

Types[edit]

A market is one of the many varieties of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations and infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering their goods or services (including labour) in exchange for money from buyers. It can be said that a market is the process by which the prices of goods and services are established. Markets facilitate trade and enable the distribution and allocation of resources in a society. Markets allow any trade-able item to be evaluated and priced. A market sometimes emerges more or less spontaneously or may be constructed deliberately by human interaction in order to enable the exchange of rights (cf. ownership) of services and goods.

Markets of varying types can spontaneously arise whenever a party has interest in a good or service that some other party can provide. Hence there can be a market for cigarettes in correctional facilities, another for chewing gum in a playground, and yet another for contracts for the future delivery of a commodity. There can be black markets, where a good is exchanged illegally, for example markets for goods under a command economy despite pressure to repress them and virtual markets, such as eBay, in which buyers and sellers do not physically interact during negotiation. A market can be organized as an auction, as a private electronic market, as a commodity wholesale market, as a shopping center, as complex institutions such as international markets and as an informal discussion between two individuals.

Markets vary in form, scale (volume and geographic reach), location and types of participants as well as the types of goods and services traded. The following is a non exhaustive list:

Physical consumer markets[edit]

Front view of Stuart Saunders Hogg Market, Kolkata

- Food retail markets: farmers’ markets, fish markets, wet markets and grocery stores

- Retail marketplaces: public markets, market squares, Main Streets, High Streets, bazaars, souqs, night markets, shopping strip malls and shopping malls

- Big-box stores: supermarkets, hypermarkets and discount stores

- Ad hoc auction markets: process of buying and selling goods or services by offering them up for bid, taking bids and then selling the item to the highest bidder

- Used goods markets such as flea markets

- Temporary markets such as fairs

- Real estate markets

Physical business markets[edit]

- Physical wholesale markets: sale of goods or merchandise to retailers; to industrial, commercial, institutional, or other professional business users or to other wholesalers and related subordinated services

- Markets for intermediate goods used in production of other goods and services

- Labour markets: where people sell their labour to businesses in exchange for a wage

- Online auctions and Ad hoc auction markets: process of buying and selling goods or services by offering them up for bid, taking bids and then selling the item to the highest bidder

- Temporary markets such as trade fairs

- Energy markets

Non-physical markets[edit]

- Media markets (broadcast market): is a region where the population can receive the same (or similar) television and radio station offerings and may also include other types of media including newspapers and Internet content

- Internet markets (electronic commerce): trading in products or services using computer networks, such as the Internet

- Artificial markets created by regulation to exchange rights for derivatives that have been designed to ameliorate externalities, such as pollution permits (see carbon trading)

Financial markets[edit]

Financial markets facilitate the exchange of liquid assets. Most investors prefer investing in two markets:

- The stock markets, for the exchange of shares in corporations (NYSE, AMEX and the NASDAQ are the most common stock markets in the United States)

- The bond markets

There are also:

- Currency markets are used to trade one currency for another, and are often used for speculation on currency exchange rates

- The money market is the name for the global market for lending and borrowing

- Futures markets, where contracts are exchanged regarding the future delivery of goods

- Prediction markets are a type of speculative market in which the goods exchanged are futures on the occurrence of certain events; they apply the market dynamics to facilitate information aggregation

- Insurance markets

- Debt markets

[edit]

- Grey markets (parallel markets): is the trade of a commodity through distribution channels which, while legal, are unofficial, unauthorized, or unintended by the original manufacturer[citation needed]

- markets in illegal goods such as the market for illicit drugs, illegal arms, infringing products, cigarettes sold to minors or untaxed cigarettes (in some jurisdictions), or the private sale of unpasteurized goat milk[11]

Mechanisms[edit]

Cabbage market by Václav Malý

In economics, a market that runs under laissez-faire policies is called a free market, it is «free» from the government, in the sense that the government makes no attempt to intervene through taxes, subsidies, minimum wages, price ceilings and so on. However, market prices may be distorted by a seller or sellers with monopoly power, or a buyer with monopsony power. Such price distortions can have an adverse effect on market participant’s welfare and reduce the efficiency of market outcomes. The relative level of organization and negotiating power of buyers and sellers also markedly affects the functioning of the market.

Markets are a system and systems have structure. The structure of a well-functioning market is defined by the theory of perfect competition. Well-functioning markets of the real world are never perfect, but basic structural characteristics can be approximated for real world markets, for example:

- Many small buyers and sellers

- Buyers and sellers have equal access to information

- Products are comparable

Markets where price negotiations meet equilibrium, but the equilibrium is not efficient are said to experience market failure. Market failures are often associated with time-inconsistent preferences, information asymmetries, non-perfectly competitive markets, principal–agent problems, externalities, or public goods. Among the major negative externalities which can occur as a side effect of production and market exchange, are air pollution (side-effect of manufacturing and logistics) and environmental degradation (side-effect of farming and urbanization).

There exists a popular thought, especially among economists, that free markets would have a structure of a perfect competition.[citation needed] The logic behind this thought is that market failure is thought to be caused by other exogenic systems, and after removing those exogenic systems («freeing» the markets) the free markets could run without market failures.[citation needed] For a market to be competitive, there must be more than a single buyer or seller. It has been suggested that two people may trade, but it takes at least three persons to have a market so that there is competition in at least one of its two sides.[12] However, competitive markets—as understood in formal economic theory—rely on much larger numbers of both buyers and sellers. A market with a single seller and multiple buyers is a monopoly. A market with a single buyer and multiple sellers is a monopsony. These are «the polar opposites of perfect competition».[13] As an argument against such logic, there is a second view that suggests that the source of market failures is inside the market system itself, therefore the removal of other interfering systems would not result in markets with a structure of perfect competition. As an analogy, such an argument may suggest that capitalists do not want to enhance the structure of markets, just like a coach of a football team would influence the referees or would break the rules if he could while he is pursuing his target of winning the game. Thus, according to this view, capitalists are not enhancing the balance of their team versus the team of consumer-workers, so the market system needs a «referee» from outside that balances the game. In this second framework, the role of a «referee» of the market system is usually to be given to a democratic government.

Research[edit]

Disciplines such as sociology, economic history, economic geography and marketing developed novel understandings of markets[14] studying actual existing markets made up of persons interacting in diverse ways in contrast to an abstract and all-encompassing concepts of «the market». The term «the market» is generally used in two ways:

- «The market» denotes the abstract mechanisms whereby supply and demand confront each other and deals are made; in its place, reference to markets reflects ordinary experience and the places, processes and institutions in which exchanges occurs[15]

- «The market» signifies an integrated, all-encompassing and cohesive capitalist world economy.

Economics[edit]

Political economy[edit]

Economics used to be called political economy, as Adam Smith defined it in The Wealth of Nations:[16]

Political economy, considered as a branch of the science of a statesman or legislator, proposes two distinct objects; first, to provide a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people, or, more properly, to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and, secondly, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for the public services. It proposes to enrich both the people and the sovereign.

The earliest works of political economy are usually attributed to the British scholars Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo, although they were preceded by the work of the French physiocrats, such as François Quesnay (1694–1774) and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727–1781). Smith describes how exchange of goods arose:[17]

«As it is by treaty, by barter, and by purchase, that we obtain from one another the greater part of those mutual good offices which we stand in need of, so it is this same trucking disposition which originally gives occasion to the division of labour. In a tribe of hunters or shepherds, a particular person makes bows and arrows, for example, with more readiness and dexterity than any other. He frequently exchanges them for cattle or for venison, with his companions; and he finds at last that he can, in this manner, get more cattle and venison, than if he himself went to the field to catch them. From a regard to his own interest, therefore, the making of bows and arrows grows to be his chief business, and he becomes a sort of armourer. Another excels in making the frames and covers of their little huts or moveable houses. He is accustomed to be of use in this way to his neighbours, who reward him in the same manner with cattle and with venison, till at last he finds it his interest to dedicate himself entirely to this employment, and to become a sort of house-carpenter. In the same manner a third becomes a smith or a brazier; a fourth, a tanner or dresser of hides or skins, the principal part of the clothing of savages. And thus the certainty of being able to exchange all that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men’s labour as he may have occasion for, encourages every man to apply himself to a particular occupation, and to cultivate and bring to perfection whatever talent of genius he may possess for that particular species of business.»

And explains how exchanged mediated by money came to dominate the market:[18]

«But when barter ceases, and money has become the common instrument of commerce, every particular commodity is more frequently exchanged for money than for any other commodity. The butcher seldom carries his beef or his mutton to the baker or the brewer, in order to exchange them for bread or for beer; but he carries them to the market, where he exchanges them for money, and afterwards exchanges that money for bread and for beer. The quantity of money which he gets for them regulates, too, the quantity of bread and beer which he can afterwards purchase. It is more natural and obvious to him, therefore, to estimate their value by the quantity of money, the commodity for which he immediately exchanges them, than by that of bread and beer, the commodities for which he can exchange them only by the intervention of another commodity; and rather to say that his butcher’s meat is worth three-pence or fourpence a-pound, than that it is worth three or four pounds of bread, or three or four quarts of small beer. Hence it comes to pass, that the exchangeable value of every commodity is more frequently estimated by the quantity of money, than by the quantity either of labour or of any other commodity which can be had in exchange for it.»

Microeconomics[edit]

Microeconomics (from Greek prefix mikro— meaning «small» and economics) is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and small impacting organizations in making decisions on the allocation of limited resources (see scarcity). On the other hand, macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix makro— meaning «large» and economics) is a branch of economics dealing with the performance, structure, behavior and decision-making of an economy as a whole, rather than individual markets.

Marginal revolution[edit]

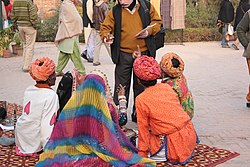

An Afghan market teeming with vendors and shoppers

The modern field of microeconomics arose as an effort of neoclassical economics school of thought to put economic ideas into mathematical mode. It began in the 19th century debates surrounding the works of Antoine Augustin Cournot, William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger and Léon Walras—this period is usually denominated as the Marginal Revolution. A recurring theme of these debates was the contrast between the labor theory of value and the subjective theory of value, the former being associated with classical economists such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Karl Marx (Marx was a contemporary of the marginalists). A labour theory of value can be understood as a theory that argues that economic value is determined by the amount of socially necessary labour time while a subjective theory of value derives economic value from subjective preferences, usually by specifying a utility function in accordance with utilitarian philosophy.

In his Principles of Economics (1890),[19] Alfred Marshall presented a possible solution to this problem, using the supply and demand model. Marshall’s idea of solving the controversy was that the demand curve could be derived by aggregating individual consumer demand curves, which were themselves based on the consumer problem of maximizing utility. The supply curve could be derived by superimposing a representative firm supply curves for the factors of production and then market equilibrium (economic equivalent of mechanical equilibrium) would be given by the intersection of demand and supply curves. He also introduced the notion of different market periods: mainly long run and short run. This set of ideas gave way to what economists call perfect competition—now found in the standard microeconomics texts, even though Marshall himself was highly skeptical it could be used as general model of all markets.

Market structure[edit]

Opposed to the model of perfect competition, some models of imperfect competition were proposed:

- The monopoly model, already considered by marginalist economists, describes a profit maximizing capitalist facing a market demand curve with no competitors, who may practice price discrimination.

- Oligopoly is a market form in which a market or industry is dominated by a small number of sellers. The oldest model was the spring water duopoly of Cournot (1838) [20] in which equilibrium is determined by the duopolists reactions functions. It was criticized by Harold Hotelling for its instability, by Joseph Bertrand for lacking equilibrium for prices as independent variables.

- Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that many producers sell products that are differentiated from one another (e.g., by branding or quality) and hence are not perfect substitutes. In monopolistic competition, a firm takes the prices charged by its rivals as given and ignores the impact of its own prices on the prices of other firms. The «founding father» of the theory of monopolistic competition is Edward Hastings Chamberlin, who wrote a pioneering book on the subject, Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933). Joan Robinson published a book called The Economics of Imperfect Competition with a comparable theme of distinguishing perfect from imperfect competition. Chamberlin defined monopolistic competition as «challenge to traditional viewpoint of economics that competition and monopoly are alternatives and that individual prices are to be explained in terms of one or the other». He continues: «By contrast it is held that most economic situations are composite of both competition and monopoly, and that, wherever this is the case, a false view is given by neglecting either one of the two forces and regarding the situation as made up entirely of the other».[21] Hotelling built a model of market located over a line with two sellers in each extreme of the line, in this case maximizing profit for both sellers leads to a stable equilibrium. From this model also follows that if a seller is to choose the location of his store so as to maximize his profit, he will place his store the closest to his competitor as «the sharper competition with his rival is offset by the greater number of buyers he has an advantage».[22] He also argues that clustering of stores is wasteful from the point of view of transportation costs and that public interest would dictate more spatial dispersion.

- William Baumol provided in his 1977 paper[23] the current formal definition of a natural monopoly where “an industry in which multifirm production is more costly than production by a monopoly”.

- Baumol defined a contestable market in his 1982 paper[24] as a market where «entry is absolutely free and exit absolutely costless», freedom of entry in Stigler sense: the incumbent has no cost discrimination against entrants. He states that a contestable market will never have an economic profit greater than zero when in equilibrium and the equilibrium will also be efficient. According to Baumol, this equilibrium emerges endogenously due to the nature of contestable markets; that is, the only industry structure that survives in the long run is the one which minimizes total costs. This is in contrast to the older theory of industry structure since not only is industry structure not exogenously given, but equilibrium is reached without an ad hoc hypothesis on the behavior of firms, say using reaction functions in a duopoly. He concludes the paper commenting that regulators that seek to impede entry and/or exit of firms would do better to not interfere if the market in question resembles a contestable market.

Market failure[edit]

Used cars market: due to presence of fundamental asymmetrical information between seller and buyer the market equilibrium is not efficient—in the language of economists it is a market failure

Around the 1970s the study of market failures came into focus with the study of information asymmetry. In particular, three authors emerged from this period: Akerlof, Spence and Stiglitz. Akerlof considered the problem of bad quality cars driving good quality cars out of the market in his classic «The Market for Lemons» (1970) because of the presence of asymmetrical information between buyers and sellers.[25] Michael Spence explained that signaling was fundamental in the labour market since employers can’t know beforehand which candidate is the most productive, a college degree becomes a signaling device that a firm uses to select new personnel.[26] Stiglitz provided some general conditions under which market equilibrium is not efficient: presence of externalities, imperfect information and incomplete markets.[27]

State interference[edit]

György Lukács, a founder of Western Marxism wrote about the essence of commodity-structure:.[28]

Before tackling the problem itself we must be quite clear in our minds that commodity fetishism is a specific problem of our age, the age of modern capitalism. Commodity exchange an the corresponding subjective and objective commodity relations existed, as we know, when society was still very primitive. What is at issue here, however, is the question: how far is commodity exchange together with its structural consequences able to influence the total outer and inner life of society? Thus the extent to which such exchange is the dominant form of metabolic change in a society cannot simply be treated in quantitative terms — as would harmonize with the modern modes of thought already eroded by the reifying effects of the dominant commodity form. The distinction between a society where this form is dominant, permeating every expression of life, and a society where it only makes an episodic appearance is essentially one of quality. For depending on which is the case, all the subjective phenomena in the societies concerned are objectified in qualitatively different ways.

Human labour is abstracted and incorporated in commodities:[29]

- Objectively: is so far as the commodity form facilitates the equal exchange of qualitatively different things

- Subjectively: human labour is both the common factor to which all commodities are reduced (in the abstract) and the principle governing the actual production of commodities (in reality)

The ultimate problem for the thought of the bourgeoisie is the crisis: the qualitative existence of the ‘things’ misunderstood as use-values become the decisive factor. The failure is characteristic of classical economics and bourgeoisie economics, inadequate at explaining the true movement of economic activity in toto. The state has a system of law corresponding to capitalist needs: bureaucracy, formal standardization of justice and civil service.[28]

C. B. Macpherson identifies an underlying model of the market underlying Anglo-American liberal democratic political economy and philosophy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: persons are cast as self-interested individuals, who enter into contractual relations with other such individuals, concerning the exchange of goods or personal capacities cast as commodities, with the motive of maximizing pecuniary interest. The state and its governance systems are cast as outside of this framework.[30] This model came to dominant economic thinking in the later nineteenth century, as so called liberal economists such as Ricardo, Mill, Jevons, Walras and later neo-classical economics shifted from reference to geographically located marketplaces to an abstract «market».[31] This tradition is continued in contemporary neoliberalism epitomised by the Mont Pelerin Society which gathered Frederick Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Milton Friedman and Karl Popper, where the market is held up as optimal for wealth creation and human freedom and the states’ role imagined as minimal, reduced to that of upholding and keeping stable property rights, contract and money supply. According to David Harvey, this allowed for boilerplate economic and institutional restructuring under structural adjustment and post-Communist reconstruction.[32] Similar formalism occurs in a wide variety of social democratic and Marxist discourses that situate political action as antagonistic to the market.

A central theme of empirical analyses is the variation and proliferation of types of markets since the rise of capitalism and global scale economies. The Regulation school stresses the ways in which developed capitalist countries have implemented varying degrees and types of environmental, economic and social regulation, taxation and public spending, fiscal policy and government provisioning of goods, all of which have transformed markets in uneven and geographical varied ways and created a variety of mixed economies.

Economic coordination[edit]

Drawing on concepts of institutional variance and path dependence, varieties of capitalism theorists (such as Peter Hall and David Soskice) identify two dominant modes of economic ordering in the developed capitalist countries:

- Coordinated market economies (such as Germany and Japan) based on relational or incomplete contracting, network monitoring based on the exchange of private information inside networks, and more reliance on collaborative, as opposed to competitive, relationships to build the competencies of the firm

- Anglo-American liberal market economies: firms coordinate their activities primarily via hierarchies and competitive market arrangements.

A coal power plant in Datteln—emissions trading or cap and trade is a market-based approach used to control pollution by providing economic incentives for achieving reductions in the emissions of pollutants

However, such approaches imply that the Anglo-American liberal market economies in fact operate in a matter close to the abstract notion of «the market». While Anglo-American countries have seen increasing introduction of neo-liberal forms of economic ordering, this has not led to simple convergence, but rather a variety of hybrid institutional orderings.[33] Rather, a variety of new markets have emerged, such as for carbon trading or rights to pollute. In some cases, such as emerging markets for water in England and Wales, different forms of neoliberalism have been tried: moving from the state hydraulic model associated with concepts of universal provision and public service to market environmentalism associated with pricing of environmental externalities to reduce environmental degradation and efficient allocation of water resources. In this case liberalization has multiple meanings:

- Privatization: change of ownership from state monopoly to private hands

- Commercialization: pursuing efficiency, cost-benefit analysis and profit maximization by introducing prices in comparison with the bill system proportional to property value

- Commodification: standardization, pricing to address water scarcity according to the Dublin principles and the Hague declaration

In a period of fiscal and ideological crisis, state failure is seen as the catalyst for liberalization, however the failure in assuring water quality can be seen as a driver for economic and ecological reregulation (in this case coming from the European Union). More broadly the idea of a water market failure can seen as the explanation for state intervention, generating a natural monopoly of hydraulic infrastructure and the regulation of externalities such as water pollution. The situation however is not that simple, as the regulator may have the duty of introducing competition, which can be:

- Direct competition or product competition

- Surrogate competition

- Competition for corporate control by mergers and takeovers

- Procurement competition

- Franchising

Introduction of metering can result in both restriction and increase of consumption with LRMC pricing being the regulator (Ofwat) preferred methodology.[34]

Marketing[edit]

Market distribution[edit]

Paul Dulaney Converse and Fred M. Jones wrote:[35]

Market distribution includes those activities which create place, time, and possession utilities. To the economist, market distribution is therefore part of production because it deals with the creation of utilities, and “distribution” refers to the distribution of wealth among the members of society. The businessman, however, thinks of distribution as selling his goods and getting them into the hands of the consumer. To the businessman, “distribution” means marketing—selling and transportation.

The methods of studying marketing are:

- Functional approach: services or functions performed, what goods they are performed upon, what middlemen perform them

- Commodity approach: what goods are marketed, what function are performed on them, what middlemen perform these functions

- Institutional approach: what institutions, or middlemen, are engaged in distribution, what functions they perform, what good they handle

Businesses market their products/services to a specific segments of consumers: the defining factors of the markets are determined by demographics, interests and age/gender. A small market is a niche market, while a big market is a mass market. A form of expansion is to enter a new market and sell/advertise to a different set of users.

Marketing management[edit]

The marketing management school, evolved in the late 1950s and early 1960s, is fundamentally linked with the marketing mix[36] framework, a business tool used in marketing and by marketers. In his paper «The Concept of the Marketing Mix», Neil H. Borden reconstructed the history of the term «marketing mix».[37][38] He started teaching the term after an associate, James Culliton, described the role of the marketing manager in 1948 as a «mixer of ingredients»; one who sometimes follows recipes prepared by others, sometimes prepares his own recipe as he goes along, sometimes adapts a recipe from immediately available ingredients, and at other times invents new ingredients no one else has tried. The functions of total marketing include advertising, personal selling, packaging, pricing, channeling and warehousing. Borden also identified the market forces affecting marketing mix:

- Consumer buying behavior

- Trade’s behavior (wholesale and retailing)

- Competitors position and behavior: industry structure, product choice, oversupply, pricing and innovation

- Governmental behavior: regulations

Borden concludes saying that marketing is more an art than a science. The marketer E. Jerome McCarthy proposed a four Ps classification (product, price, promotion, place) in 1960, which has since been used by marketers throughout the world.[39] Koichi Shimizu proposed a 7Cs Compass Model (corporation, commodity, cost, communication, channel, consumer, circumstances) to provide a more complete picture of the nature of marketing in 1981. Robert F. Lauterborn wrote about the Four P’s in 1990[40]

When Jerry McCarthy and Phil Kotler proposed their alliterative litany — Product, Price, Place and Promotion — the marketing world was very different. Roaring out of World War II with a

cranked-up production system ready to feed a lust for better living, American business linked management science to the art of mass marketing and rocketed to the moon. In the days of «Father Knows Best,» it all seemed so simple. The advertiser developed a product, priced it to make a profit, placed it on the retail shelf and promoted it to a pliant, even eager consumer. Mass media simultaneously taught consumptive culture and provided advertisers with efficient access to an audience which would behave, Dr. Dichter assured us, perfectly predictably, given the proper stimulation.

He instead advocated a four Cs classification which is a more consumer-oriented version of the four Ps that attempts to better fit the movement from mass marketing to niche marketing:

- Consumer: don’t focus on product, study consumer wants and needs

- Cost: forget price, instead understand the consumer cost to satisfy that want or need, even driving time versus time spent with family matters

- Communication: forget promotion, instead focus on communication and create dialogue

- Convenience: forget place, instead think about convenience to buy, know each market subsegment

Sociology[edit]

Economic rationality[edit]

Max Weber defines the measure of rational economic action as the:[41]

- Systematic distribution of utilities between present and future

- Systematic distribution of utilities between various potential uses

- Systematic production of utilities by manufacture or transportation by the owner of the means of production

- Systematic acquisition by agreement of the powers of control and disposal over utilities, mainly by establishing corporate groups or by exchange

Opposition of interests is typically resolved by bargaining or by competitive biding:

- Utilities, goods and labour are at the disposal of the individual without interference from others

- Transportation can be seen as a part of the process of production

- It is indifferent whether the individual is prevented from using force to interfere in the controls of others by means of a legal order, convention, custom, self-interest or moral standards

- Competition for the means of production may exist under various conditions

- Anything which may be transferred between individuals by compensation may be an object of exchange

- Conditions of exchange may be traditional, conventional (exchange of gifts) or rational (motivated by profit or need)

- Regulations may threaten the source of supply

Money may classified as:

- Coined money is called «free money» or «market money» when it is coined by the mint without limit of amount

- It is called «limited» money or «administrative money» if the issue of coinage if subject to a corporate group

- It is called regulated money if the kind and amount of coinage is subject to rules

Weber defines:

- Market situation: all the opportunities of exchanging a good for money that are known by the participants

- Marketability: degree of regularity that a good tends to be an object of exchange in the market

- Market freedom: degree of autonomy enjoyed by the participants in price determination and competition

- Market regulation: restrictions on marketability and market freedom, done by tradition, convention, law, voluntary action

Trade networks are very old and in this picture the blue line shows the trade network of the Radhanites, circa 870 CE

Weber defines «formal rationality of economic action» to designate the extent of quantitative calculation or accounting and «substantive rationality» as the degree a group of persons is or could be adequately provided with good by means of oriented course of social action. A prominent entry-point for challenging the market model’s applicability concerns exchange transactions and the homo economicus assumption of self-interest maximization. As of 2012, a number of streams of economic sociological analysis of markets focus on the role of the social in transactions and on the ways transactions involve social networks and relations of trust, cooperation and other bonds.[42] Economic geographers in turn draw attention to the ways exchange transactions occur against the backdrop of institutional, social and geographic processes, including class relations, uneven development and historically contingent path-dependencies.[43] Pierre Bourdieu has suggested the market model is becoming self-realizing in virtue of its wide acceptance in national and international institutions through the 1990s.[44]

Abstraction, market agencement and framing[edit]

Michel Callon traces the history of how the market as a place (fairs, flea markets, fish markets) became an abstract concept (market for ideas, dating market, job market) which he calls the interface market model.[45] This abstraction proceeds in three layers:

- Sellers, buyers, platform goods

- Competition

- Institutions

The interface market model thus establishes that:

- Agents and goods are distinguable

- A transfer is a communication of property rights

- Competition develops between agents

- A transaction consists of monetary payments

The limitations of this model are:

- They do not take into account the material composition of market activities

- They bracket out the constructive process of creating supply and demand, which leads to underestimating the crucial role played by bilateral transactions and the initiation of these transactions

- They create unrealism through the concepts of aggregated supply and demand and bring about difficulties in comprehending the actual mechanisms for establishing prices

- They create a total impasse on the complex processes that result in a separation between agents and goods

- The hypothesis that goods are platforms precludes us from recognizing they are processes

- A description of agents that underestimates their diversity, heterogeneity, and plasticity

Callon offer the market agencements (heterogenous assemblage) model as an alternative, its features being:

- Competition is the struggle to establish bilateral transactions that are never identical

- Innovation is fundamental to commercial activity

- Goods are processes

- Profilerating agents, plastic identities and networking

Market agencements function through framing, that is action is oriented to a strategic goal (obtaining bilateral transactions), for example market oriented passiva(c)tion:

- Detaches the good and liberates it from all those who participated in its elaboration and profiling

- Renders it apt to provoke courses of actions and to contribute to their realization (that is, imbues it with uses)

- Ensures that its behavior is at least to a certain extent controllable and predictable

- Organizes the attribution and transfer of property rights

Callon identifies the activities necessary for framing:

- Rendering goods pass(act)ive

- Activating agencies capable of evaluating and transforming these goods

- Organizing their encounter

- Ensuring the attachment of the goods to the agencies

- Obtaining consent to pay

- Setting a price and compelling payment–actions that combine and interweave with one another, with possible feedback loops and iterations

Embeddedness[edit]

Alfred Marshall wrote:[19]

Thus it is on the one side a study of wealth; and on the other, and more important side, a part of the study of man. For man’s character has been moulded by his every-day work, and the material resources which he thereby procures, more than by any other influence unless it be that of his religious ideals; and the two great forming agencies of the world’s history have been the religious and the economic. Here and there the ardour of the military or the artistic spirit has been for a while predominant: but religious and economic influences have nowhere been displaced from the front rank even for a time; and they have nearly always been more important than all others put together. Religious motives are more intense than economic, but their direct action seldom extends over so large a part of life. For the business by which a person earns his livelihood generally fills his thoughts during by far the greater part of those hours in which his mind is at its best; during them his character is being formed by the way in which he uses his faculties in his work, by the thoughts and the feelings which it suggests, and by his relations to his associates in work, his employers or his employees.

According to Max Weber the spirit of capitalism as preached by Benjamin Franklin is directly connected with utilitarianism, rationalism and Protestantism. Luther calling was not a monastic one but involves the fulfilments of obligations imposed by one’s position in the world. The pursuit of money and earthly goods was not viewed positively by Protestantism, the Puritans however emphasized that God blessings, like in the Book of Job, applied also to material life. The limitation of consumption inevitably results in capital accumulation, therefore, for Weber, the Puritan’s idea of the calling and ascetic conduct contributed to development of capitalism: saving is an ascetic activity.[46]

Embeddedness expresses the idea that the economy is not autonomous but subordinated to politics, religion, and social relations. Polanyi’s use of the term suggests the now familiar idea that market transactions depend on trust, mutual understanding, and legal enforcement of contracts.[47] Michel Callon’s concept of framing provides a useful schema: each economic act or transaction occurs against, incorporates and also re-performs a geographically and cultural specific complex of social histories, institutional arrangements, rules and connections. These network relations are simultaneously bracketed, so that persons and transactions may be disentangled from thick social bonds. The character of calculability is imposed upon agents as they come to work in markets and are “formatted” as calculative agencies. Market exchanges contain a history of struggle and contestation that produced actors predisposed to exchange under certain sets of rules. Therefore, for Challon, market transactions can never be disembedded from social and geographic relations and there is no sense to talking of degrees of embeddedness and disembeddeness.[48] During the 20th century two common forms of critique were made:

- Categories of 19th century social science such as class, modernity or the West were social constructions

- These categories were artificial and not universal

These are common themes in interpretive social science, cultural studies and post-structuralism. However, as Timothy Mitchell points out this mode of thought tends to put aside the real, the natural and nonhuman: the idea that a universal processes exists such as modernity, capitalism and globalization should not be taken for granted.[49] An emerging theme is the interrelationship, inter-penetrability and variations of concepts of persons, commodities and modes of exchange under particular market formations. This is most pronounced in recent movement towards post-structuralist theorizing that draws on Michel Foucault and Actor Network Theory and stress relational aspects of person-hood, and dependence and integration into networks and practical systems. Commodity network approaches further both deconstruct and show alternatives to the market models concept of commodities.[50]

[edit]

In social systems theory (cf. Niklas Luhmann), markets are also conceptualized as inner environments of the economy. As horizon of all potential investment decisions the market represents the environment of the actually realized investment decisions. However, such inner environments can also be observed in further function systems of society like in political, scientific, religious or mass media systems.[51]

Economic geography[edit]

Wilhelm Launhardt, a location theorist, wrote:[52]

The conditions governing the distribution and settling of the population over any area are dependent on the nature of its economic activity: and when this activity is engaged in the cultivation of the surface of the ground and in the husbandry of land and wood and on many kinds of handicrafts and small manufactures this distribution is to be assumed as uniform over the area; although, as a matter of fact, the population usually lives collected together in small hamlets, and the number of the inhabitants per unit of area, or density of population, varies according to the local conditions. Another part of the population, namely that which is engaged in wholesale commerce, the various professions of Art and Science, and that which consists of merchants and officials, lives collected in towns.

Transportation can be carried either by stone-paved roads or railways, the former not being fully developed by private capital alone. A widespread trend in economic history and sociology is skeptical of the idea that it is possible to develop a theory to capture an essence or unifying thread to markets.[53] For economic geographers, reference to regional, local, or commodity specific markets can serve to undermine assumptions of global integration and highlight geographic variations in the structures, institutions, histories, path dependencies, forms of interaction and modes of self-understanding of agents in different spheres of market exchange.[54] Reference to actual markets can show capitalism not as a totalizing force or completely encompassing mode of economic activity, but rather as «a set of economic practices scattered over a landscape, rather than a systemic concentration of power».[55]

Problematic for market formalism is the relationship between formal capitalist economic processes and a variety of alternative forms, ranging from semi-feudal and peasant economies widely operative in many developing economies, to informal markets, barter systems, worker cooperatives, or illegal trades that occur in most developed countries. Practices of incorporation of non-Western peoples into global markets in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did not merely result in the quashing of former social economic institutions. Rather, various modes of articulation arose between transformed and hybridized local traditions and social practices and the emergent world economy. By their liberal nature, so called capitalist markets have almost always included a wide range of geographically situated economic practices that do not follow the market model. Economies are thus hybrids of market and non-market elements.[56] Helpful here is J.K. Gibson-Graham’s complex topology of the diversity of contemporary market economies describing different types of transactions, labour and economic agents. Transactions can occur in black markets (such as for marijuana) or be artificially protected (such as for patents). They can cover the sale of public goods under privatization schemes to co-operative exchanges and occur under varying degrees of monopoly power and state regulation. Likewise, there are a wide variety of economic agents, which engage in different types of transactions on different terms: one cannot assume the practices of a religious kindergarten, multinational corporation, state enterprise, or community-based cooperative can be subsumed under the same logic of calculability. This emphasis on proliferation can also be contrasted with continuing scholarly attempts to show underlying cohesive and structural similarities to different markets.[42] Gibson-Graham thus read a variety of alternative markets for fair trade and organic foods or those using local exchange trading system as not only contributing to proliferation, but also forging new modes of ethical exchange and economic subjectivities.

Anthropology[edit]

Economic anthropology is a scholarly field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology begin with the Polish-British founder of anthropology, Bronisław Malinowski, and his French compatriot, Marcel Mauss, on the nature of gift-giving exchange (or reciprocity) as an alternative to market exchange. Studies in economic anthropology for the most part are focused on exchange but they a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical:[57] for example Trobianders described by Malinowski deviate from rational self-interested individual.[58]

Bronisław Malinowski’s path-breaking work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), addressed the question «why would men risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets?». He begins by describing trade in the South Sea:[58]

The coastal populations of the South Sea Islands, with very few exceptions, are, or were before their extinction, expert navigators and traders. Several of them had evolved excellent types of large sea-going canoes, and used to embark in them on distant trade expeditions or raids of war and conquest. The Papuo-Melanesians, who inhabit the coast and the outlying islands of New Guinea, are no exception to this rule. In general they are daring sailors, industrious manufacturers, and keen traders. The manufacturing centres of important articles, such as pottery, stone implements, canoes, fine baskets, valued ornaments, are localised in several places, according to the skill of the inhabitants, their inherited tribal tradition, and special facilities offered by the district; thence they are traded over wide areas, sometimes travelling more than hundreds of miles. Definite forms of exchange along definite trade routes are to be found established between the various tribes. A most remarkable form of intertribal trade is that obtaining between the Motu of Port Moresby and the tribes of the Papuan Gulf. The Motu sail for hundreds of miles in heavy, unwieldy canoes, called lakatoi, which are provided with the characteristic crab-claw sails. They bring pottery and shell ornaments, in olden days, stone blades, to Gulf Papuans, from whom they obtain in exchange sago and the heavy dug-outs, which are used afterwards by the Motu for the construction of their lakatoi canoes.

The economic situation can vary considerably depending on the tribes and islands: for example the Gumawana villagers are known as efficient sailors and for their skill in pottery, they are, however, island monopolists keeping the trade in their own hands without improving it. In a series of three expeditions, Malinowski carefully traced the network of exchanges of bracelets and necklaces across the Trobriand Islands and established that they were part of a system of inter-tribal exchange: it is known as the Kula ring, a closed circuit in which necklaces of red shells go in a clockwise motion and bracelets of white shell go in anticlockwise motion. Malinowski goes on to explain:[58]

Thus in the Introduction we called the Kula a “form of trade,” and we ranged it alongside other systems of barter. This is quite correct, if we give the word “trade” a sufficiently wide interpretation, and mean by it any exchange of goods. But the word “trade” is used in current Ethnography and economic literature with so many different implications that a whole lot of misleading, preconceived ideas have to be brushed aside in order to grasp the facts correctly. Thus the aprioric current notion of primitive trade would be that of an exchange of indispensable or useful articles, done without much ceremony or regulation, under stress of dearth or need, in spasmodic, irregular intervals—and this done either by direct barter, everyone looking out sharply not to be done out of his due, or, if the savages were too timid and distrustful to face one another, by some customary arrangement, securing by means of heavy penalties compliance in the obligations incurred or imposed.* Waiving for the present the question how far this conception is valid or not in general—in my opinion it is quite misleading—we have to realise clearly that the Kula contradicts in almost every point the above definition of “savage trade.” It shows to us primitive exchange in an entirely different light.

The Kula is not a surreptitious and precarious form of exchange. It is, quite on the contrary, rooted in myth, backed by traditional law, and surrounded with magical rites. All its main transactions are public and ceremonial, and carried out according to definite rules. It is not done on the spur of the moment, but happens periodically, at dates settled in advance, and it is carried on along definite trade routes, which must lead to fixed trysting places. Sociologically, though transacted between tribes differing in language, culture, and probably even in race, it is based on a fixed and permanent status, on a partnership which binds into couples some thousands of individuals. This partnership is a lifelong relationship, it implies various mutual duties and privileges, and constitutes a type of inter-tribal relationship on an enormous scale. As to the economic mechanism of the transactions, this is based on a specific form of credit, which implies a high degree of mutual trust and commercial honour—and this refers also to the subsidiary, minor trade, which accompanies the Kula proper. Finally, the Kula is not done under stress of any need, since its main aim is to exchange articles which are of no practical use.

French crown jewels in the Louvre exhibition

In the 1920s and later, Malinowski’s study became the subject of debate with the French anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, author of The Gift (Essai sur le don, 1925).[59] Malinowski emphasized the exchange of goods between individuals and their non-altruistic motives for giving: they expected a return of equal or greater value (colloquially referred to as «Indian giving»). In other words, reciprocity is an implicit part of gifting as no «free gift» is given without expectation of reciprocity. In contrast, Mauss has emphasized that the gifts were not between individuals, but between representatives of larger collectivities.

He stated that this exchange system was clearly linked to political authority.[60] He argued these gifts were a «total prestation» as they were not simple, alienable commodities to be bought and sold, but like the «Crown jewels» embodied the reputation, history and sense of identity of a «corporate kin group», such as a line of kings. Given the stakes, Mauss asked «why anyone would give them away?» and his answer was an enigmatic concept, «the spirit of the gift». A good part of the confusion (and resulting debate) was due to a bad translation. Mauss appeared to be arguing that a return gift is given to keep the very relationship between givers alive; a failure to return a gift ends the relationship; and the promise of any future gifts. Based on an improved translate, Jonathan Parry has demonstrated that Mauss was arguing that the concept of a «pure gift» given altruistically only emerges in societies with a well-developed market ideology.[60]

Rather than emphasize how particular kinds of objects are either gifts or commodities to be traded in restricted spheres of exchange, Arjun Appadurai and others began to look at how objects flowed between these spheres of exchange. They shifted attention away from the character of the human relationships formed through exchange and placed it on «the social life of things» instead. They examined the strategies by which an object could be «singularized» (made unique, special, one-of-a-kind) and so withdrawn from the market. A marriage ceremony that transforms a purchased ring into an irreplaceable family heirloom is one example whereas the heirloom, in turn, makes a perfect gift.

Mathematical modeling[edit]

Although arithmetic has been used since the beginning of civilization to set prices, it was not until the 19th century that data was systematically collected and more advanced mathematical tools began to be used to study markets in the form of social statistics. Business intelligence is also dated to the 19th century, but it was with the rise of the computer that business analytics exploded. More recent techniques involve data mining and marketing engineering.

Size parameters[edit]

Market size can be given in terms of the number of buyers and sellers in a particular market[61] or in terms of the total exchange of money in the market, generally annually (per year). When given in terms of money, market size is often termed «market value», but in a sense distinct from market value of individual products. For one and the same goods, there may be different (and generally increasing) market values at the production level, the wholesale level and the retail level. For example, the value of the global illicit drug market for the year 2003 was estimated by the United Nations to be US$13 billion at the production level, $94 billion at the wholesale level (taking seizures into account) and US$322 billion at the retail level (based on retail prices and taking seizures and other losses into account).[62]

-

United States home sales (blue)

-

Book Sales in the United Kingdom

-

See also[edit]

- Grocery store

- Justice and the Market

- Knowledge market

- Market economy

- Market engineering

- Market information systems

- Market microstructure

- Market town

- Shopper marketing

References[edit]

- ^ «Transaction», Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Coase, Ronald (1937). «The Nature of the Firm». Economica. Blackwell Publishing. 4 (16): 386–405. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x. JSTOR 2626876.

- ^ Williamson, Oliver E. (1989). «3: Transaction Cost Economies». Handbook of Industrial Organization. Vol. 1. Elsevier. pp. 135–182. doi:10.1016/S1573-448X(89)01006-X. ISBN 9780444704344.

- ^ Grossman, Sanford J.; Hart, Oliver D. (1986). «The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration». Journal of Political Economy. 94 (4): 691–719. doi:10.1086/261404.

- ^ Kállay, Balázs (2012). «Contract Theory of the Firm». Journal of Scientific Papers ECONOMICS & SOCIOLOGY. 5: 39–50. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2012/5-1/3.

- ^ Lafontaine, Francine; Slade, Margaret (2007). «Vertical Integration and Firm Boundaries: The Evidence» (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 45 (3): 629–685. doi:10.1257/jel.45.3.629. JSTOR 27646842.

- ^ «80% of trade takes place in ‘value chains’ linked to transnational corporations, UNCTAD report says». United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 27 February 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ «World Investment Report 1996». United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 1996. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Antras, Pol (2015). «Global Production: Firms, Contracts, and Trade Structure» (PDF). Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Rajan, Raghuram G.; Zingales, Luigi (1998). «Financial Dependence and Growth». The American Economic Review. 88 (3): 559–586. doi:10.3386/w5758. JSTOR 116849.

- ^

Heyne, Paul; Boettke, Peter J.; Prychitko, David L. (2014). The Economic Way of Thinking (13th ed.). Pearson. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-0-13-299129-2. - ^ O’Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8.

- ^ Robert S. Pindyck, Daniel L. Rubinfeld, Microeconomics, Pearson International Edition 2009

- ^ Diaz Ruiz, C.A. (2012). «Theories of markets: Insights from marketing and the sociology of markets». The Marketing Review. 12 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1362/146934712X13286274424316.

- ^ Callon, M. (1998) «Introduction: The Embeddedness of Economic Markets in Economics.» In The Laws of the Markets, edited by Michel Callon. Basic Blackwell/The Sociological Review pp. 1–57 1998, p.2).

- ^ A. Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776, Book IV, Of systems of political economy

- ^ A. Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776, Book I, Chapter II, Of the principle which gives occasion to the division of labour

- ^ A. Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776, Book I, Chapter V, Of the real and nominal price of commodities, or of their price in labour, and their price of money

- ^ a b A. Marshall, Principles of Economics, 1890

- ^ A. Cournot, Researches into the mathematical principles of the theory of wealth, 1838 https://archive.org/details/researchesintom00fishgoog

- ^ Chamberlin, E.H. (1937). «Monopolistic or Imperfect Competition?». Quarterly Journal of Economics. 51 (4): 557–580. doi:10.2307/1881679. JSTOR 1881679.

- ^ Hotteling, H. (1929). «Stability in Competition». The Economic Journal. 39 (153): 41–57. doi:10.2307/2224214. JSTOR 2224214.

- ^ Baumol, William J. (1977). «On the Proper Cost Tests for Natural Monopoly in a Multiproduct Industry». American Economic Review. 67 (5): 809–822. JSTOR 1828065.

- ^ Baumol W., Contestable Markets: An Uprising in the Theory of Industry Structure, American Economic Review vol 72 pp. 1-15 1982 http://econ.ucdenver.edu/beckman/research/readings/baumol-contestable.pdf

- ^ Akerlof, George A. (1970). «The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism». Quarterly Journal of Economics. 84 (3): 488–500. doi:10.2307/1879431. JSTOR 1879431.

- ^ Spence, A. M. (1973). «Job Market Signaling». Quarterly Journal of Economics. 87 (3): 355–374. doi:10.2307/1882010. JSTOR 1882010.

- ^ Greenwald, Bruce; Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1986). «Externalities in Economies with Imperfect Information and Incomplete Markets». Quarterly Journal of Economics. 101 (2): 229–264. doi:10.2307/1891114. JSTOR 1891114.

- ^ a b Lukács, György. (1971) History and Class Consciousness, Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat-I:The Phenomenon of Reification, Trans. Rodney Livingstone. Merlin Press. London.

- ^ Lukács, György. (1971) History and Class Consciousness. Trans. Rodney Livingstone. Merlin Press. London. p. 87

- ^ MacPherson, C.B. (1962) The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: From Hobbes to Locke. Oxford Clarendon Press. p.3

- ^ Swedberg, 1994, p. 258

- ^ Harvey, David (2005) A Short History of Neoliberalism Oxford University Press.

- ^ Peck, supra, p. 154)

- ^ Bakker, Karen (2005) «Neoliberalizing Nature?: Market Environmentalism in water supply in England and Wales» Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (3), 542–565

- ^ Converse, Paul Dulaney and Jones, Fred M. (1948). Introduction to Marketing — Principles of Wholesale and Retail Distribution. Prentice-Hall

- ^ Michael J Baker, Michael John Baker, Michael Saren, Marketing Theory: A Student Text, SAGE 2010

- ^

Borden, Neil. «The Concept of the Marketing Mix». Suman Thapa. Retrieved 24 April 2013. - ^ Borden, Neil H. (1965). «The Concept of the Marketing Mix». In Schwartz, George (ed.). Science in marketing. Wiley marketing series. Wiley. pp. 286ff. ISBN 9780471766001. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Needham, Dave (1996). Business for Higher Awards. Oxford, England: Heinemann.

- ^ Lauterborn, B. (1990). New Marketing Litany: Four Ps Passé: C-Words Take Over. Advertising Age, 61(41), 26.

- ^ Weber, Max. The Theory Of Social And Economic Organization. Free Press.

- ^ a b Swedberg, 1994, p. 267

- ^ Martin, Ron (2000) «Institutional Approaches in Economic Geography», Handbook of Economic Geography. Ed. Eric Sheppard and Trevor J. Barnes. Blackwell Publishers.Peck, 2005

- ^ Bourdieu, Pierre (1999) Acts of Resistance: Against the Tyranny of the Market. The New Press.p. 95

- ^

Callon, Michel (2021). Markets in the Making . Zone Books. - ^ Weber, Max (2012). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Start Publishing LLC.

- ^ Polanyi, Karl (2001). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Beacon Press.

- ^ Callon, 1998; Mitchell, 2002, p. 291,

- ^ Timothy Mitchell. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity

- ^ Hughes, Alex (2005) «Geographies of Exchange and Circulation: alternative trading spaces» Progress in Human Geography

- ^ Roth, Steffen (2012). «Leaving commonplaces on the common place: Cornerstones of a polyphonic market theory». Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry. 10 (3): 43–52. SSRN 2192754.

- ^ Launhardt Wilhelm 1900. The theory of trace: being a discussion of the principles of location, Lawrence Asylum Press

- ^

Swedberg, Richard (1994) «Markets as Social Structures» The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Ed. Neil Smelser and Richard Swedberg. Princeton University Press. OCLC 29703776, p. 258) - ^

Peck, J. (2005) «Economic Geographies in Space» Economic Geography 81(2) 129–175. - ^ (Gibson-Graham, J.K. (2006) Postcapitalist Politics. University of Minnesota Press,. p. 2).

- ^ (Mitchell, Timothy (2002) Rule of Experts. University of California Pressp. 270; Gibson-Graham 2006, supra pp. 53–78)

- ^ Bourdieu, Pierre (2017). Anthropologie économique — Cours au Collège de France 1992-1993. Editions du Seuil.

- ^ a b c Malinowski, Bronislaw. Argonauts Of The Western Pacific — An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea — Read Books Ltd.

- ^ Mauss, Marcel (1970). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Cohen & West.

- ^ a b Parry, Jonathan (1986). «The Gift, the Indian Gift and the ‘Indian Gift’«. Man. 21 (3): 453–473. doi:10.2307/2803096. JSTOR 2803096. S2CID 152071807.

- ^ investorwords.com > market size Retrieved on April 17, 2010

- ^ United Nations, «2005 World Drug Report,» Office on Drugs and Crime, June 2005, p. 16. [1]

Further reading[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Market.

- Pindyck, Robert S. and Daniel L. Rubinfeld, Microeconomics, Prentice Hall 2012.

- Frank, Robert H., Microeconomics and Behavior, 6th ed., McGraw-Hill/Irwin 2006.

- Kotler, P. and Keller, K.L., Marketing Management, Prentice Hall 2011.

- Baker, Michael J. and Michael Saren, Marketing Theory: A Student Text, Sage 2010. online.

- Aspers, Patrik, Markets, Polity Press 2011. online.

- Bauer, Leonard and Herbert Matis (1988) From moral to political economy: The Genesis of social sciences, History of European Ideas 9 (2), 125–143.

- Nathaus, Klaus and David Gilgen (Eds.), Change of Markets and Market Societies: Concepts and Case Studies. Historical Social Research 36 (3), Special Issue, 2011.

Recent Examples on the Web

That perk provides an additional financial boost to budget-conscious traders in the developing world, Binance’s biggest retail market by far.

—

Basketball, popular sport, big market, room for growth.

—

There has been more fear in the bond market, where Treasury yields have sunk on worries about a weaker economy and the banking system’s struggles.

—

Medora Lee is a money, markets, and personal finance reporter at USA TODAY.

—

Some cynics might suspect more-rational, if unattractive, explanations for this proposal, ranging from hyping AI (and the stock-market valuations that would go with those magic initials) to using regulation (or even just a pause) to distort the competitive landscape.

—

Money managers are warming up to prime money-market funds, vehicles that invest in everything from Treasurys to short-term loans to corporations, including banks.

—

Three of the award wins were for The Times’ series Legal Weed, Broken Promises, an investigation into California’s dysfunctional and corrupt recreational cannabis market, which exposed regulators’ failure to protect the state’s cannabis workers.

—

Such markets, with a menagerie of wildlife in close, crowded conditions with humans, are known to act as hotbeds of risk for viral adaption and spillovers.

—

In 2021, Miami Beach made headlines when, while still in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, the city marketed itself to visitors even though many nightclubs remained closed, leading to raucous street parties.

—

The beauty industry has long marketed ways for people to appear younger.

—

The play is deliberately being marketed as a musical comedy and not a country musical.

—

For instance, a generic drug could be marketed to treat one type of heart problem, but not another.

—

The property – which includes Fairfield Lake – was marketed to sell for more than $110 million.

—

The company markets dozens of toys and figurines from Disney properties, like Spider-Man, Buzz Lightyear, and Mickey Mouse.

—

Vitapost ProJoint Plus Vitapost ProJoint Plus is marketed as a premium joint support supplement with a formula that consists of glucosamine sulphate, boswellia serrata extract, chondroitin sulfate, turmeric, quercetin, methionine, MSM, and bromelain.

—

It is marketed under the brand name Nexletol.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘market.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

What Is a Market?

A market is a place where parties can gather to facilitate the exchange of goods and services. The parties involved are usually buyers and sellers. The market may be physical like a retail outlet, where people meet face-to-face, or virtual like an online market, where there is no direct physical contact between buyers and sellers. There are some key characteristics that help define a market, including the availability of an arena, buyers and sellers, and a commodity that can be purchased and sold.

Key Takeaways

- A market is a place where buyers and sellers can meet to facilitate the exchange or transaction of goods and services.

- Markets can be physical like a retail outlet, or virtual like an e-retailer.

- Other examples include illegal markets, auction markets, and financial markets.

- Markets establish the prices of goods and services that are determined by supply and demand.

- Features of a market include the availability of an arena, buyers and sellers, and a commodity.

Market

Understanding Markets

A market is any place where two or more parties can meet to engage in an economic transaction—even those that don’t involve legal tender. A market transaction may involve goods, services, information, currency, or any combination of these that pass from one party to another. In short, markets are arenas in which buyers and sellers can gather and interact.

Two parties are generally needed to make a trade. But, at minimum, a third party is required to introduce competition and bring balance to the market. As such, a market in a state of perfect competition, among other things, is characterized by a high number of active buyers and sellers.

Beyond this broad definition, the term market encompasses a variety of things, depending on the context. For instance, it may refer to the stock market, which is the place where securities are traded. It may also be used to describe a collection of people who wish to buy a specific product or service in a specific place, such as the Brooklyn housing market. Or it could refer to an industry or business sector, such as the global diamond market.

Certain decisions that help shape the market are determined by an economic system known as the market economy. In this system, factors like investments and the production, distribution, and pricing of goods and services are led by supply and demand from businesses and individuals. As such, a market economy is unplanned and is not part of a planned or command economy where the government dictates all of these factors. Examples of market economies include the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates the stock, bond, and currency markets. It puts provisions in place to prevent fraud while ensuring traders and investors have the right information to make the most informed decisions possible.

Supply and Demand

Whatever the context, a market establishes the prices for goods and other services. These rates are determined by supply and demand. The idea of supply and demand is one of the very basics of economics. Supply is created by the sellers, while demand is generated by buyers.

Markets try to find some balance in price when supply and demand are themselves in balance. But that balance can in itself be disrupted by factors other than price including incomes, expectations, technology, the cost of production, and the number of buyers and sellers participating.

To put it simply, the number of goods and services available is determined by what people want and how eager they are to buy. Sellers increase production when buyers demand more goods and services. Producers then increase their prices in order to realize a profit. When buyer demand decreases, companies have to drop their prices and, therefore, the number of goods and services they bring to market.

Physical and Virtual Markets

Markets may be represented by physical locations where transactions are made. These include retail stores and other similar businesses that sell individual items to wholesale markets selling goods to distributors. Or they may be virtual. Internet-based stores and auction sites such as Amazon and eBay are examples of markets where transactions can take place entirely online and the parties involved never connect physically.

Markets may emerge organically or as a means of enabling ownership rights over goods, services, and information. When on a national or other more specific regional level, markets may often be categorized as developed or developing markets. This distinction depends on many factors, including income levels and the nation or region’s openness to foreign trade.

The size of a market is determined by the number of buyers and sellers, as well as the amount of money that changes hands each year.

Types of Markets