Word: The Definition & Criteria

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language. Words can be classified according to their action and meaning, but it is challenging to define.

A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Example : ‘love’, ‘cricket’, ‘sky’ etc.

«[A word is the] smallest unit of grammar that can stand alone as a complete utterance, separated by spaces in written language and potentially by pauses in speech.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Morphology, a branch of linguistics, studies the formation of words. The branch of linguistics that studies the meaning of words is called lexical semantics.

See More:

Online English Grammar Course

Free Online Exercise of English Grammar

There are several criteria for a speech sound, or a combination of some speech sounds to be called a word.

- There must be a potential pause in speech and a space in written form between two words.

For instance, suppose ‘ball’ and ‘bat’ are two different words. So, if we use them in a sentence, we must have a potential pause after pronouncing each of them. It cannot be like “Idonotplaywithbatball.” If we take pause, these sounds can be regarded as seven distinct words which are ‘I,’ ‘do,’ ‘not,’ ‘play,’ ‘with,’ ‘bat,’ and ‘ball.’ - Every word must contain at least one root. If you break this root, it cannot be a word anymore.

For example, the word ‘unfaithful’ has a root ‘faith.’ If we break ‘faith’ into ‘fa’ and ‘ith,’ these sounds will not be regarded as words. - Every word must have a meaning.

For example, the sound ‘lakkanah’ has no meaning in the English language. So, it cannot be an English word.

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language.A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Contents

- 1 What is word and its example?

- 2 What is word and its types?

- 3 What is word linguistics?

- 4 What is the meaning of word?

- 5 What are words called?

- 6 What is word in language?

- 7 What is a word class in grammar?

- 8 Why do we define words?

- 9 Why do we say word?

- 10 What is morpheme and word?

- 11 What is word Slideshare?

- 12 Is word a noun or verb?

- 13 What are the parts of a word?

- 14 What is word Wikipedia?

- 15 What type of word is there?

- 16 What is word boundaries?

- 17 What is called sentence?

- 18 Is your name a word?

- 19 What are the 4 main word classes?

- 20 What is word class in syntax?

What is word and its example?

The definition of a word is a letter or group of letters that has meaning when spoken or written. An example of a word is dog.An example of words are the seventeen sets of letters that are written to form this sentence.

What is word and its types?

There are eight types of words that are often referred to as ‘word classes’ or ‘parts of speech’ and are commonly distinguished in English: nouns, determiners, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions.These are the different types of words in the English language.

What is word linguistics?

In linguistics, a word of a spoken language can be defined as the smallest sequence of phonemes that can be uttered in isolation with objective or practical meaning.In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a “word” may be learned as part of learning the writing system.

What is the meaning of word?

1 : a sound or combination of sounds that has meaning and is spoken by a human being. 2 : a written or printed letter or letters standing for a spoken word. 3 : a brief remark or conversation I’d like a word with you.

What are words called?

All words belong to categories called word classes (or parts of speech) according to the part they play in a sentence. The main word classes in English are listed below. Noun. Verb. Adjective.

What is word in language?

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sounds, or its representation in writing, that symbolizes and communicates a meaning and may consist of a single morpheme or a combination of morphemes. The branch of linguistics that studies word structures is called morphology.

A word class is a group of words that have the same basic behaviour, for example nouns, adjectives, or verbs.

Why do we define words?

The definition of definition is “a statement expressing the essential nature of something.” At least that’s one way Webster defines the word.Because definitions enable us to have a common understanding of a word or subject; they allow us to all be on the same page when discussing or reading about an issue.

Why do we say word?

‘Word’ in slang is a word one would use to indicate acknowledgement, approval, recognition or affirmation, of something somebody else just said.

What is morpheme and word?

Word vs Morpheme

A morpheme is usually considered as the smallest element of a word or else a grammar element, whereas a word is a complete meaningful element of language.

What is word Slideshare?

•“A word’ is a free morpheme or a combination of morphemes that together form a basic segment of speech” .

Is word a noun or verb?

word used as a noun:

A distinct unit of language (sounds in speech or written letters) with a particular meaning, composed of one or more morphemes, and also of one or more phonemes that determine its sound pattern. A distinct unit of language which is approved by some authority.

What are the parts of a word?

The parts of a word are called morphemes. These include suffixes, prefixes and root words. Take the word ‘microbiology,’ for example.

What is word Wikipedia?

A word is something spoken by the mouth, that can be pronounced. In alphabetic writing, it is a collection of letters used together to communicate a meaning. These can also usually be pronounced.Some words have different pronunciation, for example, ‘wind’ (the noun) and ‘wind’ (the verb) are pronounced differently.

What type of word is there?

The word “there” have multiple functions. In verbal and written English, the word can be used as an adverb, a pronoun, a noun, an interjection, or an adjective. This word is classified as an adverb if it is used to modify a verb in the sentence.

What is word boundaries?

A word boundary is a zero-width test between two characters. To pass the test, there must be a word character on one side, and a non-word character on the other side. It does not matter which side each character appears on, but there must be one of each.

What is called sentence?

A sentence is a set of words that are put together to mean something. A sentence is the basic unit of language which expresses a complete thought. It does this by following the grammatical basic rules of syntax.A complete sentence has at least a subject and a main verb to state (declare) a complete thought.

Is your name a word?

Yes, names are words. Specifically, they are proper nouns: they refer to specific people, places, or things. “John” is a proper noun; “ground” is a common noun. But both are words.

What are the 4 main word classes?

There are four major word classes: verb, noun, adjective, adverb.

What is word class in syntax?

In English grammar, a word class is a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially their inflections and distribution.It is also variously called grammatical category, lexical category, and syntactic category (although these terms are not wholly or universally synonymous).

Although

the borderline between various linguistic units is not always sharp

and clear, we shall try to define every new term on its first

appearance at once simply and unambiguously, if not always very

rigorously. The approximate definition of the term word

has already been given in the opening page of the book.

The

important point to remember about

definitions

is that they should indicate the most essential characteristic

features of the notion expressed by the term under discussion, the

features by which this notion is distinguished from other similar

notions. For instance, in defining the word one must distinguish it

from other linguistic units, such as the phoneme, the morpheme, or

the word-group. In contrast with a definition, a description

aims at enumerating all the essential features of a notion.

To

make things easier we shall begin by a preliminary description,

illustrating it with some examples.

The

word

may be described as the basic unit of language. Uniting meaning and

form, it is composed of one or more morphemes, each consisting of one

or more spoken sounds or their written representation. Morphemes as

we have already said are also meaningful units but they cannot be

used independently, they are always parts of words whereas words can

be used as a complete utterance (e. g. Listen!).

The

combinations of morphemes within words are subject to certain linking

conditions. When a derivational affix is added a new word is formed,

thus, listen

and

listener

are

different words. In fulfilling different grammatical functions words

may take functional affixes: listen

and

listened

are

different forms of the same word. Different forms of the same word

can be also built analytically with the help of auxiliaries. E.g.:

The

world should listen then as I am listening now (Shelley).

When

used in sentences together with other words they are syntactically

organised. Their freedom of entering into syntactic constructions is

limited by many factors, rules and constraints (e. g.: They

told me this story but

not *They

spoke me this story).

The

definition of every basic notion is a very hard task: the definition

of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics because the

27

simplest

word has many different aspects. It has a sound form because it is a

certain arrangement of phonemes; it has its morphological structure,

being also a certain arrangement of morphemes; when used in actual

speech, it may occur in different word forms, different syntactic

functions and signal various meanings. Being the central element of

any language system, the word is a sort of focus for the problems of

phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology and also for some other

sciences that have to deal with language and speech, such as

philosophy and psychology, and probably quite a few other branches of

knowledge. All attempts to characterise the word are necessarily

specific for each domain of science and are therefore considered

one-sided by the representatives of all the other domains and

criticised for incompleteness. The variants of definitions were so

numerous that some authors (A. Rossetti, D.N. Shmelev) collecting

them produced works of impressive scope and bulk.

A

few examples will suffice to show that any definition is conditioned

by the aims and interests of its author.

Thomas

Hobbes (1588-1679),

one

of the great English philosophers, revealed a materialistic approach

to the problem of nomination when he wrote that words are not mere

sounds but names of matter. Three centuries later the great Russian

physiologist I.P. Pavlov (1849-1936)

examined

the word in connection with his studies of the second signal system,

and defined it as a universal signal that can substitute any other

signal from the environment in evoking a response in a human

organism. One of the latest developments of science and engineering

is machine translation. It also deals with words and requires a

rigorous definition for them. It runs as follows: a word is a

sequence of graphemes which can occur between spaces, or the

representation of such a sequence on morphemic level.

Within

the scope of linguistics the word has been defined syntactically,

semantically, phonologically and by combining various approaches.

It

has been syntactically defined for instance as “the minimum

sentence” by H. Sweet and much later by L. Bloomfield as “a

minimum free form”. This last definition, although structural in

orientation, may be said to be, to a certain degree, equivalent to

Sweet’s, as practically it amounts to the same thing: free forms

are later defined as “forms which occur as sentences”.

E.

Sapir takes into consideration the syntactic and semantic aspects

when he calls the word “one of the smallest completely satisfying

bits of isolated ‘meaning’, into which the sentence resolves

itself”. Sapir also points out one more, very important

characteristic of the word, its indivisibility:

“It cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning, one or two

other or both of the several parts remaining as a helpless waif on

our hands”. The essence of indivisibility will be clear from a

comparison of the article a

and

the prefix a-

in

a

lion and

alive.

A lion is

a word-group because we can separate its elements and insert other

words between them: a

living lion, a dead lion. Alive is

a word: it is indivisible, i.e. structurally impermeable: nothing can

be inserted between its elements. The morpheme a-

is

not free, is not a word. The

28

situation

becomes more complicated if we cannot be guided by solid spelling.’

“The Oxford English Dictionary», for instance, does not

include the

reciprocal pronouns each

other and

one

another under

separate headings, although

they should certainly be analysed as word-units, not as word-groups

since they have become indivisible: we now say with

each other and

with

one another instead

of the older forms one

with another or

each

with the other.1

Altogether

is

one word according to its spelling, but how is one to treat all

right, which

is rather a similar combination?

When

discussing the internal cohesion of the word the English linguist

John Lyons points out that it should be discussed in terms of two

criteria “positional

mobility”

and

“uninterruptability”.

To illustrate the first he segments into morphemes the following

sentence:

the

—

boy

—

s

—

walk

—

ed

—

slow

—

ly

—

up

—

the

—

hill

The

sentence may be regarded as a sequence of ten morphemes, which occur

in a particular order relative to one another. There are several

possible changes in this order which yield an acceptable English

sentence:

slow

—

ly

—

the

—

boy

—

s

—

walk

—

ed

—

up

—

the

—

hill

up —

the

—

hill

—

slow

—

ly

—

walk

—

ed

—

the

—

boy

—

s

Yet

under all the permutations certain groups of morphemes behave as

‘blocks’ —

they

occur always together, and in the same order relative to one another.

There is no possibility of the sequence s

—

the

—

boy,

ly —

slow,

ed —

walk.

“One

of the characteristics of the word is that it tends to be internally

stable (in terms of the order of the component morphemes), but

positionally mobile (permutable with other words in the same

sentence)”.2

A

purely semantic treatment will be found in Stephen Ullmann’s

explanation: with him connected discourse, if analysed from the

semantic point of view, “will fall into a certain number of

meaningful segments which are ultimately composed of meaningful

units. These meaningful units are called words.»3

The

semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated by A.H.Gardiner’s

definition: “A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of

denoting something which is spoken about.»4

The

eminent French linguist A. Meillet (1866-1936)

combines

the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria and advances a

formula which underlies many subsequent definitions, both abroad and

in our country, including the one given in the beginning of this

book: “A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning

with a

1

E. Language.

An Introduction to the Study of Speech. London, 1921,

P.

35.

2 Lyons,

John. Introduction

to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Univ. Press, 1969.

P. 203.

3 Ullmann

St. The

Principles of Semantics. Glasgow, 1957.

P.

30.

4 Gardiner

A.H. The

Definition of the Word and the Sentence //

The

British Journal of Psychology. 1922.

XII.

P. 355

(quoted

from: Ullmann

St.,

Op.

cit., P. 51).

29

particular

group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment.»1

This

definition does not permit us to distinguish words from phrases

because not only child,

but

a

pretty child as

well are combinations of a particular group of sounds with a

particular meaning capable of a particular grammatical employment.

We

can, nevertheless, accept this formula with some modifications,

adding that a word is the smallest significant unit of a given

language capable of functioning alone and characterised by positional

mobility

within

a sentence, morphological

uninterruptability

and semantic

integrity.2

All these criteria are necessary because they permit us to create a

basis for the oppositions between the word and the phrase, the word

and the phoneme, and the word and the morpheme: their common feature

is that they are all units of the language, their difference lies in

the fact that the phoneme is not significant, and a morpheme cannot

be used as a complete utterance.

Another

reason for this supplement is the widespread scepticism concerning

the subject. It has even become a debatable point whether a word is a

linguistic unit and not an arbitrary segment of speech. This opinion

is put forth by S. Potter, who writes that “unlike a phoneme or a

syllable, a word is not a linguistic unit at all.»3

He calls it a conventional and arbitrary segment of utterance, and

finally adopts the already mentioned

definition of L. Bloomfield. This position is, however, as

we have already mentioned, untenable, and in fact S. Potter himself

makes ample use of the word as a unit in his linguistic analysis.

The

weak point of all the above definitions is that they do not establish

the relationship between language and thought, which is formulated if

we treat the word as a dialectical unity of form and content, in

which the form is the spoken or written expression which calls up a

specific meaning, whereas the content is the meaning rendering the

emotion or the concept in the mind of the speaker which he intends to

convey to his listener.

Summing

up our review of different definitions, we come to the conclusion

that they are bound to be strongly dependent upon the line of

approach, the aim the scholar has in view. For a comprehensive word

theory, therefore, a description seems more appropriate than a

definition.

The

problem of creating a word theory based upon the materialistic

understanding of the relationship between word and thought on the one

hand, and language and society, on the other, has been one of the

most discussed for many years. The efforts of many eminent scholars

such as V.V. Vinogradov, A. I. Smirnitsky, O.S. Akhmanova, M.D.

Stepanova, A.A. Ufimtseva —

to

name but a few, resulted in throwing light

1

A. Linguistique

historique et linguistique generate. Paris,

1926.

Vol.

I. P. 30.

2 It

might be objected that such words as articles, conjunctions and a few

other words

never occur as sentences, but they are not numerous and could be

collected into a

list of exceptions.

3 See:

Potter

S. Modern

Linguistics. London, 1957.

P.

78.

30

on this problem and achieved a

clear presentation of the word as a basic unit of the language. The

main points may now be summarised.

The

word

is the

fundamental

unit

of language.

It is a dialectical

unity

of form

and

content.

Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect

human notions, and in this sense may be considered as the form of

their existence. Concepts fixed in the meaning of words are formed as

generalised and approximately correct reflections of reality,

therefore in signifying them words reflect reality in their content.

The

acoustic aspect of the word serves to name objects of reality, not to

reflect them. In this sense the word may be regarded as a sign. This

sign, however, is not arbitrary but motivated by the whole process of

its development. That is to say, when a word first comes into

existence it is built out of the elements already available in the

language and according to the existing patterns.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

What is the definition of word in English grammar?

A word is a single unit of language. There are four main word classes: verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs. A clause is the basic unit of grammar, which is usually made up of a subject, a verb phrase and, sometimes, a complement.

What is the meaning of the word mean?

1 : a middle point or something (as a place, time, number, or rate) that falls at or near a middle point : moderation. 2 : arithmetic mean. 3 means plural : something that helps a person to get what he or she wants Use every means you can think of to find it.

What is the definition of Merriam Webster?

1a : the thing one intends to convey especially by language : purport Do not mistake my meaning. b : the thing that is conveyed especially by language : import Many words have more than one meaning.

How do I find the meaning of a word?

Using the context of the paragraph to define unknown words can also helpful. Although it takes practice, it is the easiest and most efficient way to identify words. Often, using the context is the only way to figure out the meaning of the word as it is used in the sentence, passage, or chapter. Consider the word “bar”.

Do words have meaning?

word: a single unit of language that represents abstractions of different order and can be spoken or written. Words, by themselves, do not have meanings. (The ‘meanings’ of words we read in a dictionary were assigned by lexicographers. And lexicographers depend on the meanings given to these words by other humans.)

How do you identify unfamiliar words?

Below are five strategies I encourage students to use when they encounter new words in a text.

- Look at the parts of the word.

- Break down the sentence.

- Hunt for clues.

- Think about connotative meaning (ideas, feelings, or associations beyond the dictionary definition).

What is unfamiliar word?

: not familiar: a : not well-known : strange an unfamiliar place. b : not well acquainted unfamiliar with the subject. Other Words from unfamiliar Synonyms & Antonyms Example Sentences Learn More About unfamiliar.

Why is it important to identify and understand words you didn’t know?

Answer. Explanation: Learning vocabulary is a very important part of learning a language. The more words you know, the more you will be able to understand what you hear and read; and the better you will be able to say what you want to when speaking or writing.

What is reading in your own words?

“Reading” is the process of looking at a series of written symbols and getting meaning from them. When we read, we use our eyes to receive written symbols (letters, punctuation marks and spaces) and we use our brain to convert them into words, sentences and paragraphs that communicate something to us.

When you don’t understand what somebody just said?

These sentences will help you when you don’t understand something even though you have heard it. Sorry, I’m afraid I don’t follow you. Excuse me, could you repeat the question? I’m sorry, I don’t understand.

What word describes things we don’t understand?

synonyms: opaque incomprehensible, uncomprehensible. difficult to understand.

How do you politely tell someone you can’t understand their accent?

Try to be subtle about it though, you do not want to overdo it. For example: “I am sorry could you please repeat that.” Or “ Would you mind repeating that for me a little slower, I did not catch that, did you mean snakes or snacks”. I suppose most of the times you can do without even having to mention the accent.

How do you politely interrupt a patient?

Primary Care

- Excuse yourself. Acknowledge you are making an interruption.

- Empathize. Let the patient know you’ve heard his or her complaints. This demonstrates respect and understanding.

- Explain. Let the patient know your reason for interrupting.

How do you interrupt someone in a nice way?

Tips for Interrupting

- Have a specific purpose.

- Use proper timing.

- Be as polite as possible.

- Use a gesture.

- Clear your throat.

- Keep a noticeable distance when interrupting someone else’s conversation.

- Get clarification.

- Thank the others for allowing you to interrupt.

What do you call a person who constantly interrupts?

“A chronic interrupter is often someone who is super-smart and whose brain is working much faster than the other people in the room. They want to keep everything moving at a faster clip, so often they will interrupt to make that happen,” says executive coach Beth Banks Cohn.

What do you call someone that talks over you?

A loquacious person talks a lot, often about stuff that only they think is interesting. You can also call them chatty or gabby, but either way, they’re loquacious. Of course, if you’ve got nothing to say, a loquacious person might make a good dinner companion, because they’ll do all the talking.

Do narcissists dominate conversation?

But they can only stand it for so long, and they usually prefer to dominate conversations with their own thoughts and opinions.

What’s another word for interrupt?

What is another word for interrupt?

| intrude | intervene |

|---|---|

| disconnect | disjoin |

| disrupt | disunite |

| divide | hinder |

| in | infringe |

What is the definition of interfere?

intransitive verb. 1 : to enter into or take a part in the concerns of others. 2 : to interpose in a way that hinders or impedes : come into collision or be in opposition.

What does interrupt mean definition?

1 : to stop or hinder by breaking in interrupted the speaker with frequent questions. 2 : to break the uniformity or continuity of a hot spell occasionally interrupted by a period of cool weather. intransitive verb. : to break in upon an action especially : to break in with questions or remarks while another is …

What’s another word for mess up?

What is another word for mess up?

| flub | bungle |

|---|---|

| screw up | foul up |

| goof up | louse up |

| muck up | make a mistake |

| muddle up | jack up |

Is messed up a bad word?

As to ‘messed up’, it can fit in all these instances with the same grammar and potential for ambiguity that often doesn’t matter. It’s just not at all taboo. It is still informal, just not taboo.

What do you mean by mess up?

informal. : to make a mistake : to do something incorrectly About halfway into the recipe, I realized that I had messed up, and I had to start over.

What does mess with someone mean?

informal. 1 : to cause trouble for (someone) : to deal with (someone) in a way that may cause anger or violence I wouldn’t want to mess with him.

Do not mess with me meaning?

Originally Answered: What does “don’t mess with me” mean? It means, “ don’t interfere in my affairs”. The person will not tolerate your interference. If you do so, you are indirectly being warned that, you would get into unnecessary trouble.

Are you messing with me means?

in. to bother or interfere with someone or something. Don’t mess with me unless you want trouble. Don’t monkey with the TV. It’s out of kilter. See also: mess, someone, something.

What is the meaning of dangerous to mess with?

(phrasal verb) in the sense of interfere with. to interfere in, or become involved with, a dangerous person, thing, or situation.

What is the definition of word in English grammar?

by

Alex Heath

·

2019-05-14

What is the definition of word in English grammar?

A word is a single unit of language. There are four main word classes: verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs. A clause is the basic unit of grammar, which is usually made up of a subject, a verb phrase and, sometimes, a complement.

What is the spoken word of God called?

Rhema is the word which the Lord has spoken, and now He speaks it again.”

Why did Jesus heal people?

Jesus healed the man from paralysis (physical) and he said to him “Your sins are forgiven” (spiritual healing). Jesus’ entire ministry was directed toward spiritual ends. Its primary objective was to restore human beings to proper relationship with God. Emotional needs of people were also addressed by Jesus.

What is Jesus healing?

Healing was essential to the ministry of Jesus because He had the power to perform miracles. During his earthly ministry, Jesus Christ performed miracles by touching, healing, and transforming countless lives.

What is the definition of miracles?

A miracle (from the Latin mirari, to wonder), at a first and very rough approximation, is an event that is not explicable by natural causes alone. A reported miracle excites wonder because it appears to require, as its cause, something beyond the reach of human action and natural causes.

How does Christianity define a miracle?

A miracle is an extraordinary event that goes against nature, cannot be explained by science and that Christians believe is caused by God. In Matthew’s day, people would have believed in miracles and did not need any scientific explanations or proof.

How do you describe faith?

In the context of religion, one can define faith as “belief in a god or in the doctrines or teachings of religion”. Religious people often think of faith as confidence based on a perceived degree of warrant, while others who are more skeptical of religion tend to think of faith as simply belief without evidence.

What are the three elements of miracles?

1.1 A Miracle as an Unusual Event

- 1 A Miracle as a Violation of a Natural Law.

- 2 A Miracle as an Overriding or Circumvention of a Natural Law.

- 3 A Miracle as a Coincidence with an Available Natural Explanation.

What are two elements of miracles?

This second definition offers two important criteria that an event must satisfy in order to qualify as a miracle: It must be a violation of natural law, but this by itself is not enough; a miracle must also be an expression of the divine will.

Why is faith necessary for a miracle?

You cannot have a miracle without faith Faith is always necessary for healing in the gospels – we can see this every time Jesus healed someone. Miracles strengthen faith. Therefore the miracle has to happen first and then a person will trust and have faith. People today require proof in order to have faith.

Why is having faith in God important?

Having faith is having trust. You have to trust with your entire being that God has your back that he will help you and take care of you. He knows what is best, but to truly embrace what he has planned for you, you have to fully trust. Our trust is not foolish, for our God is both faithful and good.

What is a miracle in the Bible?

Miracle, extraordinary and astonishing happening that is attributed to the presence and action of an ultimate or divine power.

How does God communicate with us?

God uses human channels to speak words of prophecy, tongues and interpretation and words of wisdom and knowledge (1 Cor. 12:8-10). God also expresses Himself through human vessels to distribute His message in anointed sermons, songs and writings.

What requirements are needed for a miracle to be accepted?

For a case to fulfil the criteria for a medical miracle, the healing must be instant and long-lasting. This decision is made by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, and requires scientific consultation to explore and exclude alternative explanations. The process is not transparent and the decision is final.

What Is the Definition of Word?

«The trouble with words,» said British dramatist Dennis Potter, «is that you never know whose mouths they’ve been in.».

ZoneCreative S.r.l./Getty Images

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sounds, or its representation in writing, that symbolizes and communicates a meaning and may consist of a single morpheme or a combination of morphemes.

The branch of linguistics that studies word structures is called morphology. The branch of linguistics that studies word meanings is called lexical semantics.

Etymology

From Old English, «word»

Examples and Observations

- «[A word is the] smallest unit of grammar that can stand alone as a complete utterance, separated by spaces in written language and potentially by pauses in speech.»

-David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003 - «A grammar . . . is divided into two major components, syntax and morphology. This division follows from the special status of the word as a basic linguistic unit, with syntax dealing with the combination of words to make sentences, and morphology with the form of words themselves.» -R. Huddleston and G. Pullum, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2002

- «We want words to do more than they can. We try to do with them what comes to very much like trying to mend a watch with a pickaxe or to paint a miniature with a mop; we expect them to help us to grip and dissect that which in ultimate essence is as ungrippable as shadow. Nevertheless there they are; we have got to live with them, and the wise course is to treat them as we do our neighbours, and make the best and not the worst of them.»

-Samuel Butler, The Note-Books of Samuel Butler, 1912 - Big Words

«A Czech study . . . looked at how using big words (a classic strategy for impressing others) affects perceived intelligence. Counter-intuitvely, grandiose vocabulary diminished participants’ impressions of authors’ cerebral capacity. Put another way: simpler writing seems smarter.»

-Julie Beck, «How to Look Smart.» The Atlantic, September 2014 - The Power of Words

«It is obvious that the fundamental means which man possesses of extending his orders of abstractions indefinitely is conditioned, and consists in general in symbolism and, in particular, in speech. Words, considered as symbols for humans, provide us with endlessly flexible conditional semantic stimuli, which are just as ‘real’ and effective for man as any other powerful stimulus. - Virginia Woolf on Words

«It is words that are to blame. They are the wildest, freest, most irresponsible, most un-teachable of all things. Of course, you can catch them and sort them and place them in alphabetical order in dictionaries. But words do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. If you want proof of this, consider how often in moments of emotion when we most need words we find none. Yet there is the dictionary; there at our disposal are some half-a-million words all in alphabetical order. But can we use them? No, because words do not live in dictionaries, they live in the mind. Look once more at the dictionary. There beyond a doubt lie plays more splendid than Antony and Cleopatra; poems lovelier than the ‘Ode to a Nightingale’; novels beside which Pride and Prejudice or David Copperfield are the crude bunglings of amateurs. It is only a question of finding the right words and putting them in the right order. But we cannot do it because they do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. And how do they live in the mind? Variously and strangely, much as human beings live, ranging hither and thither, falling in love, and mating together.»

-Virginia Woolf, «Craftsmanship.» The Death of the Moth and Other Essays, 1942 - Word Word

«Word Word [1983: coined by US writer Paul Dickson]. A non-technical, tongue-in-cheek term for a word repeated in contrastive statements and questions: ‘Are you talking about an American Indian or an Indian Indian?’; ‘It happens in Irish English as well as English English.'»

-Tom McArthur, The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press, 1992

According to traditional grammar, a word is defined as, “the basic unit of language”. The word is usually a speech sound or mixture of sounds which is represented in speaking and writing.

Few examples of words are fan, cat, building, scooter, kite, gun, jug, pen, dog, chair, tree, football, sky, etc.

You can also define it as, “a letter or group/set of letters which has some meaning”. So, therefore the words are classified according to their meaning and action.

It works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in the language.

The group of words makes a sentence. These sentences contain different types of functions (of the words) in it.

The structure (formation) of words can be studied with Morphology which is usually a branch (part) of linguistics.

The meaning of words can be studied with Lexical semantics which is also a branch (part) of linguistics.

Also Read: What is a Sentence in English Grammar? | Best Guide for 2021

The word can be used in many ways. Few of them are mentioned below.

- Noun (rabbit, ring, pencil, US, etc)

- Pronoun (he, she, it, we, they, etc)

- Adjective (big, small, fast, slow, etc)

- Verb (jumping, singing, dancing, etc)

- Adverb (slowly, fastly, smoothly, etc)

- Preposition (in, on, into, for, under, etc)

- Conjunction (and, or, but, etc)

- Subject (in the sentences)

- Verb and many more!

Now, let us understand the basic rules of the words.

Rules/Conditions for word

There are some set of rules (criteria) in the English Language which describes the basic necessity of becoming a proper word.

Rule 1: Every word should have some potential pause in between the speech and space should be given in between while writing.

For example, consider the two words like “football” and “match” which are two different words. So, if you want to use them in a sentence, you need to give a pause in between the words for pronouncing.

It cannot be like “Iwanttowatchafootballmatch” which is very difficult to read (without spaces).

But, if you give pause between the words while reading like, “I”, “want”, “to”, “watch”, “a”, “football”, “match”.

Example Sentence: I want to watch a football match.

We can observe that the above sentence can be read more conveniently and it is the only correct way to read, speak and write.

- Incorrect: Iwanttowatchafootballmatch.

- Correct: I want to watch a football match.

So, always remember that pauses and spaces should be there in between the words.

Rule 2: Every word in English grammar must contain at least one root word.

The root word is a basic word which has meaning in it. But if we further break down the words, then it can’t be a word anymore and it also doesn’t have any meaning in it.

So, let us consider the above example which is “football”. If we break this word further, (such as “foot” + “ball”), we can observe that it has some meaning (even after breaking down).

Now if we further break down the above two words (“foot” + “ball”) like “fo” + “ot” and “ba” + “ll”, then we can observe that the words which are divided have no meaning to it.

So, always you need to remember that the word should have atleast one root word.

Rule 3: Every word you want to use should have some meaning.

Yes, you heard it right!

We know that there are many words in the English Language. If you have any doubt or don’t know the meaning of it, then you can check in the dictionary.

But there are also words which are not defined in the English Language. Many words don’t have any meaning.

So, you need to use only the words which have some meaning in it.

For example, consider the words “Nuculer” and “lakkanah” are not defined in English Language and doesn’t have any meaning.

Always remember that not every word in the language have some meaning to it.

Also Read: 12 Rules of Grammar | (Grammar Basic Rules with examples)

More examples of Word

| Words List | Words List |

| apple | ice |

| aeroplane | jam |

| bat | king |

| biscuit | life |

| cap | mango |

| doll | nest |

| eagle | orange |

| fish | pride |

| grapes | raincoat |

| happy | sad |

Quiz Time! (Test your knowledge here)

#1. A word can be ____________.

all of the above

all of the above

a noun

a noun

an adjective

an adjective

a verb

a verb

Answer: A word can be a noun, verb, adjective, preposition, etc.

#2. A root word is a word that _____________.

none

none

can be divided further

can be divided further

cannot be divided further

cannot be divided further

both

both

Answer: A root word is a word that cannot be divided further.

#3. A group of words can make a ___________.

none

none

sentence

sentence

letters

letters

words

words

Answer: A group of words can make a sentence.

#4. Morphology is a branch of ___________.

none

none

Linguistics

Linguistics

Phonology

Phonology

Semantics

Semantics

Answer: Morphology is a branch of Linguistics.

#5. The meaning of words can be studied with ___________.

none

none

both

both

Morphology

Morphology

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

Answer: The meaning of the words can be studied with Lexical semantics.

#6. The word is the largest unit in the language. Is it true or false?

#7. Is cat a word? State true or false.

Answer: “Cat” is a word.

#8. A word is a _____________.

group of paragraphs

group of paragraphs

group of letters

group of letters

group of sentences

group of sentences

All of the above

All of the above

Answer: A word is a group of letters which delivers a message or an idea.

#9. A word is usually a speech sound or mixture of it. Is it true or false?

#10. The structure of words can be studied with ___________.

Morphology

Morphology

both

both

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

none

none

Answer: The structure of words can be studied with Morphology.

Results

—

Hurray….. You have passed this test! 🙂

Congratulations on completing the quiz. We are happy that you have understood this topic very well.

If you want to try again, you can start this quiz by refreshing this page.

Otherwise, you can visit the next topic 🙂

Oh, sorry about that. You didn’t pass this test! 🙁

Please read the topic carefully and try again.

Summary: (What is a word?)

- Generally, the word is the basic and smallest unit in the language.

- It is categorised based on its meaning.

- Morphology is the study of Words structure (formation) and Lexical semantics is the study of meanings of the words. These both belong to a branch of Linguistics.

- A word should have at least one root and meaning to it.

Also Read: What is Grammar? | (Grammar definition, types & examples) | Best Guide 2021

If you are interested to learn more, then you can refer wikipedia from here.

I hope that you understood the topic “What is a word?”. If you still have any doubts, then comment down below and we will respond as soon as possible. Thank You.

Definition of a Word

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sound having a particular meaning for an idea, object or thought and has a spoken or written form. In English language word is composed by an individual letter (e.g., ‘I’), I am a boy, or by combination of letters (e.g., Jam, name of a person) Jam is a boy. Morphology, a branch of linguistics, deals with the structure of words where we learn under which rules new words are formed, how we assigned a meaning to a word? how a word functions in a proper context? how to spell a word? etc.

Examples of word: All sentences are formed by a series of words. A sentence starts with a word, consists on words and ends with a word. Therefore, there is nothing else in a sentence than a word.

Some different examples are: Boy, kite, fox, mobile phone, nature, etc.

Different Types of Word

There are many types of word; abbreviation, acronym, antonym, back formation, Clipped words (clipping), collocation, compound words, Content words, contractions, derivation, diminutive, function word, homograph, homonym, homophone, legalism, linker, conjunct, borrowed, metonym, monosyllable, polysyllable, rhyme, synonym, etc. Read below for short introduction to each type of word.

Abbreviation

An abbreviation is a word that is a short form of a long word.

Example: Dr for doctor, gym for gymnasium

Acronym

Acronym is one of the commonly used types of word formed from the first letter or letters of a compound word/ term and used as a single word.

Example: PIA for Pakistan International Airline

Antonym

An antonym is a word that has opposite meaning of an another word

Example: Forward is an antonym of word backward or open is an antonym of word close.

Back formation

Back formation word is a new word that is produced by removing a part of another word.

Example: In English, ‘tweeze’ (pluck) is a back formation from ‘tweezers’.

Clipped words

Clipped word is a word that has been clipped from an already existing long word for ease of use.

Example: ad for advertisement

Collocation

Collocation is a use of certain words that are frequently used together in form of a phrase or a short sentence.

Example: Make the bed,

Compound words

Compound words are created by placing two or more words together. When compound word is formed the individual words lose their meaning and form a new meaning collectively. Both words are joined by a hyphen, a space or sometime can be written together.

Example: Ink-pot, ice cream,

Content word

A content word is a word that carries some information or has meaning in speech and writing.

Example: Energy, goal, idea.

Contraction

A Contraction is a word that is formed by shortening two or more words and joining them by an apostrophe.

Example: ‘Don’t’ is a contraction of the word ‘do not’.

Derivation

Derivation is a word that is derived from within a language or from another language.

Example: Strategize (to make a plan) from strategy (a plan).

Diminutive

Diminutive is a word that is formed by adding a diminutive suffix with a word.

Example: Duckling by adding suffix link with word duck.

Function word

Function word is a word that is mainly used for expressing some grammatical relationships between other words in a sentence.

Example: (Such as preposition, or auxiliary verb) but, with, into etc.

Homograph

Homograph is a word that is same in written form (spelled alike) as another word but with a different meaning, origin, and occasionally pronounced with a different pronunciation

Example: Bow for ship and same word bow for shooting arrows.

Homonym

Homonyms are the words that are spelled alike and have same pronunciation as another word but have a different meaning.

Example: Lead (noun) a material and lead (verb) to guide or direct.

Homophone

Homophones are the words that have same pronunciation as another word but differ in spelling, meaning, and origin.

Example: To, two, and too are homophones.

Hyponym

Hyponym is a word that has more specific meaning than another more general word of which it is an example.

Example: ‘Parrot’ is a hyponym of ‘birds’.

Legalism

Legalism is a type of word that is used in law terminology.

Example: Summon, confess, judiciary

Linker/ conjuncts

Linker or conjuncts are the words or phrase like ‘however’ or ‘what’s more’ that links what has already been written or said to what is following.

Example: however, whereas, moreover.

Loanword/ borrowed

A loanword or borrowed word is a word taken from one language to use it in another language without any change.

Example: The word pizza is taken from Italian language and used in English language

Metonym

Metonym is a word which we use to refer to something else that it is directly related to that.

Example: ‘Islamabad’ is frequently used as a metonym for the Pakistan government.

Monosyllable

Monosyllable is a word that has only one syllable.

Example: Come, go, in, yes, or no are monosyllables.

Polysyllable

Polysyllable is a word that has two or more than two syllables.

Example: Interwoven, something or language are polysyllables.

Rhyme

Rhyme is a type of word used in poetry that ends with similar sound as the other words in stanza.

Example; good, wood, should, could.

Synonym

Synonym is a word that has similar meaning as another word.

Example: ‘happiness’ is a synonym for ‘joy’.

This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

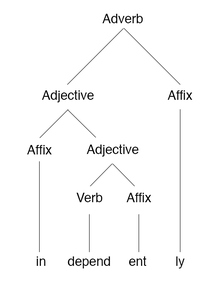

Morphology

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Jump to:

Definition |

Related Entries |

A word is the smallest unit of a language that can exist on its own in either written or spoken language. A morpheme such as -ly, used to create an adverb cannot exist without the adjective it modifies; it is not a word, although the adjective it modifies can exist alone and, therefore, is a word:

The woman was robbed. (4 words- an article a noun an auxiliary verb and a past participle. ‘Robbed’ consists of the verb ‘rob’ and the -ed morpheme to show that it is a past participle so the sentence has 5 morphemes.)

See Also:

Phoneme; Syllable; Sentence; Letter; Utterance

Category:

Functions & Text

Related to ‘Word’

Noun

How do you spell that word?

“Please” is a useful word.

Our teacher often used words I didn’t know.

What is the French word for car?

Describe the experience in your own words.

The lawyer used Joe’s words against him.

She gave the word to begin.

We will wait for your word before we serve dinner.

Verb

Could we word the headline differently?

tried to word the declaration exactly right

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

Despite the red flags, hundreds of investors were receiving their dividends on time and word was spreading.

—

For Lin, surviving sepsis left him determined to make sure that the word gets out about sepsis — and not just in English.

—

Hayes became the first woman to earn the honor in 1977, earning the title after her Grammy win for best spoken word recording for Great American Documents.

—

The Clue: This word starts with a consonant and ends with a vowel.

—