For broader coverage of this topic, see Volcanism.

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are diverging or converging, and most are found underwater. For example, a mid-ocean ridge, such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has volcanoes caused by divergent tectonic plates whereas the Pacific Ring of Fire has volcanoes caused by convergent tectonic plates. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching and thinning of the crust’s plates, such as in the East African Rift and the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field and Rio Grande rift in North America. Volcanism away from plate boundaries has been postulated to arise from upwelling diapirs from the core–mantle boundary, 3,000 kilometers (1,900 mi) deep in the Earth. This results in hotspot volcanism, of which the Hawaiian hotspot is an example. Volcanoes are usually not created where two tectonic plates slide past one another.

Large eruptions can affect atmospheric temperature as ash and droplets of sulfuric acid obscure the Sun and cool the Earth’s troposphere. Historically, large volcanic eruptions have been followed by volcanic winters which have caused catastrophic famines.[1]

Other planets besides Earth have volcanoes. For example, Mercury has pyroclastic deposits formed by explosive volcanic activity.[2]

Etymology

The word volcano is derived from the name of Vulcano, a volcanic island in the Aeolian Islands of Italy whose name in turn comes from Vulcan, the god of fire in Roman mythology.[3] The study of volcanoes is called volcanology, sometimes spelled vulcanology.[4]

Plate tectonics

Map showing the divergent plate boundaries (oceanic spreading ridges) and recent sub-aerial volcanoes (mostly at convergent boundaries)

According to the theory of plate tectonics, Earth’s lithosphere, its rigid outer shell, is broken into sixteen larger and several smaller plates. These are in slow motion, due to convection in the underlying ductile mantle, and most volcanic activity on Earth takes place along plate boundaries, where plates are converging (and lithosphere is being destroyed) or are diverging (and new lithosphere is being created).[5]

Divergent plate boundaries

At the mid-ocean ridges, two tectonic plates diverge from one another as hot mantle rock creeps upwards beneath the thinned oceanic crust. The decrease of pressure in the rising mantle rock leads to adiabatic expansion and the partial melting of the rock, causing volcanism and creating new oceanic crust. Most divergent plate boundaries are at the bottom of the oceans, and so most volcanic activity on the Earth is submarine, forming new seafloor. Black smokers (also known as deep sea vents) are evidence of this kind of volcanic activity. Where the mid-oceanic ridge is above sea level, volcanic islands are formed, such as Iceland.[6]

Convergent plate boundaries

Subduction zones are places where two plates, usually an oceanic plate and a continental plate, collide. The oceanic plate subducts (dives beneath the continental plate), forming a deep ocean trench just offshore. In a process called flux melting, water released from the subducting plate lowers the melting temperature of the overlying mantle wedge, thus creating magma. This magma tends to be extremely viscous because of its high silica content, so it often does not reach the surface but cools and solidifies at depth. When it does reach the surface, however, a volcano is formed. Thus subduction zones are bordered by chains of volcanoes called volcanic arcs. Typical examples are the volcanoes in the Pacific Ring of Fire, such as the Cascade Volcanoes or the Japanese Archipelago, or the eastern islands of Indonesia.[7]

Hotspots

Hotspots are volcanic areas thought to be formed by mantle plumes, which are hypothesized to be columns of hot material rising from the core-mantle boundary. As with mid-ocean ridges, the rising mantle rock experiences decompression melting which generates large volumes of magma. Because tectonic plates move across mantle plumes, each volcano becomes inactive as it drifts off the plume, and new volcanoes are created where the plate advances over the plume. The Hawaiian Islands are thought to have been formed in such a manner, as has the Snake River Plain, with the Yellowstone Caldera being the part of the North American plate currently above the Yellowstone hotspot.[8] However, the mantle plume hypothesis has been questioned.[9]

Continental rifting

Main article: Rift

Sustained upwelling of hot mantle rock can develop under the interior of a continent and lead to rifting. Early stages of rifting are characterized by flood basalts and may progress to the point where a tectonic plate is completely split.[10][11] A divergent plate boundary then develops between the two halves of the split plate. However, rifting often fails to completely split the continental lithosphere (such as in an aulacogen), and failed rifts are characterized by volcanoes that erupt unusual alkali lava or carbonatites. Examples include the volcanoes of the East African Rift.[12]

Volcanic features

The most common perception of a volcano is of a conical mountain, spewing lava and poisonous gases from a crater at its summit; however, this describes just one of the many types of volcano. The features of volcanoes are much more complicated and their structure and behavior depends on a number of factors. Some volcanoes have rugged peaks formed by lava domes rather than a summit crater while others have landscape features such as massive plateaus. Vents that issue volcanic material (including lava and ash) and gases (mainly steam and magmatic gases) can develop anywhere on the landform and may give rise to smaller cones such as Puʻu ʻŌʻō on a flank of Kīlauea in Hawaii.

Other types of volcano include cryovolcanoes (or ice volcanoes), particularly on some moons of Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune; and mud volcanoes, which are formations often not associated with known magmatic activity. Active mud volcanoes tend to involve temperatures much lower than those of igneous volcanoes except when the mud volcano is actually a vent of an igneous volcano.

Fissure vents

Volcanic fissure vents are flat, linear fractures through which lava emerges.

Shield volcanoes

Shield volcanoes, so named for their broad, shield-like profiles, are formed by the eruption of low-viscosity lava that can flow a great distance from a vent. They generally do not explode catastrophically, but are characterized by relatively gentle effusive eruptions. Since low-viscosity magma is typically low in silica, shield volcanoes are more common in oceanic than continental settings. The Hawaiian volcanic chain is a series of shield cones, and they are common in Iceland, as well.

Lava domes

Lava domes are built by slow eruptions of highly viscous lava. They are sometimes formed within the crater of a previous volcanic eruption, as in the case of Mount St. Helens, but can also form independently, as in the case of Lassen Peak. Like stratovolcanoes, they can produce violent, explosive eruptions, but the lava generally does not flow far from the originating vent.

Cryptodomes

Cryptodomes are formed when viscous lava is forced upward causing the surface to bulge. The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was an example; lava beneath the surface of the mountain created an upward bulge, which later collapsed down the north side of the mountain.

Cinder cones

Izalco volcano, the youngest volcano in El Salvador. Izalco erupted almost continuously from 1770 (when it formed) to 1958, earning it the nickname of «Lighthouse of the Pacific».

Cinder cones result from eruptions of mostly small pieces of scoria and pyroclastics (both resemble cinders, hence the name of this volcano type) that build up around the vent. These can be relatively short-lived eruptions that produce a cone-shaped hill perhaps 30 to 400 meters (100 to 1,300 ft) high. Most cinder cones erupt only once. Cinder cones may form as flank vents on larger volcanoes, or occur on their own. Parícutin in Mexico and Sunset Crater in Arizona are examples of cinder cones. In New Mexico, Caja del Rio is a volcanic field of over 60 cinder cones.

Based on satellite images, it was suggested that cinder cones might occur on other terrestrial bodies in the Solar system too; on the surface of Mars and the Moon.[13][14][15][16]

Stratovolcanoes (composite volcanoes)

Cross-section through a stratovolcano (vertical scale is exaggerated):

- Large magma chamber

- Bedrock

- Conduit (pipe)

- Base

- Sill

- Dike

- Layers of ash emitted by the volcano

- Flank

- Layers of lava emitted by the volcano

- Throat

- Parasitic cone

- Lava flow

- Vent

- Crater

- Ash cloud

Stratovolcanoes (composite volcanoes) are tall conical mountains composed of lava flows and tephra in alternate layers, the strata that gives rise to the name. They are also known as composite volcanoes because they are created from multiple structures during different kinds of eruptions. Classic examples include Mount Fuji in Japan, Mayon Volcano in the Philippines, and Mount Vesuvius and Stromboli in Italy.

Ash produced by the explosive eruption of stratovolcanoes has historically posed the greatest volcanic hazard to civilizations. The lavas of stratovolcanoes are higher in silica, and therefore much more viscous, than lavas from shield volcanoes. High-silica lavas also tend to contain more dissolved gas. The combination is deadly, promoting explosive eruptions that produce great quantities of ash, as well as pyroclastic surges like the one that destroyed the city of Saint-Pierre in Martinique in 1902. They are also steeper than shield volcanoes, with slopes of 30–35° compared to slopes of generally 5–10°, and their loose tephra are material for dangerous lahars.[17] Large pieces of tephra are called volcanic bombs. Big bombs can measure more than 4 feet (1.2 meters) across and weigh several tons.[18]

Supervolcanoes

A supervolcano is a volcano that has experienced one or more eruptions that produced over 1,000 cubic kilometers (240 cu mi) of volcanic deposits in a single explosive event.[19] Such eruptions occur when a very large magma chamber full of gas-rich, silicic magma is emptied in a catastrophic caldera-forming eruption. Ash flow tuffs emplaced by such eruptions are the only volcanic product with volumes rivaling those of flood basalts.[20]

A supervolcano can produce devastation on a continental scale. Such volcanoes are able to severely cool global temperatures for many years after the eruption due to the huge volumes of sulfur and ash released into the atmosphere. They are the most dangerous type of volcano. Examples include Yellowstone Caldera in Yellowstone National Park and Valles Caldera in New Mexico (both western United States); Lake Taupō in New Zealand; Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia; and Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania. Fortunately, supervolcano eruptions are very rare events, though because of the enormous area they cover, and subsequent concealment under vegetation and glacial deposits, supervolcanoes can be difficult to identify in the geologic record without careful geologic mapping.[21]

Submarine volcanoes

Satellite images of the 15 January 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai

Submarine volcanoes are common features of the ocean floor. Volcanic activity during the Holocene Epoch has been documented at only 119 submarine volcanoes, but there may be more than one million geologically young submarine volcanoes on the ocean floor.[22][23] In shallow water, active volcanoes disclose their presence by blasting steam and rocky debris high above the ocean’s surface. In the deep ocean basins, the tremendous weight of the water prevents the explosive release of steam and gases; however, submarine eruptions can be detected by hydrophones and by the discoloration of water because of volcanic gases. Pillow lava is a common eruptive product of submarine volcanoes and is characterized by thick sequences of discontinuous pillow-shaped masses which form under water. Even large submarine eruptions may not disturb the ocean surface, due to the rapid cooling effect and increased buoyancy in water (as compared to air), which often causes volcanic vents to form steep pillars on the ocean floor. Hydrothermal vents are common near these volcanoes, and some support peculiar ecosystems based on chemotrophs feeding on dissolved minerals. Over time, the formations created by submarine volcanoes may become so large that they break the ocean surface as new islands or floating pumice rafts.

In May and June 2018, a multitude of seismic signals were detected by earthquake monitoring agencies all over the world. They took the form of unusual humming sounds, and some of the signals detected in November of that year had a duration of up to 20 minutes. An oceanographic research campaign in May 2019 showed that the previously mysterious humming noises were caused by the formation of a submarine volcano off the coast of Mayotte.[24]

Subglacial volcanoes

Subglacial volcanoes develop underneath icecaps. They are made up of lava plateaus capping extensive pillow lavas and palagonite. These volcanoes are also called table mountains, tuyas,[25] or (in Iceland) mobergs.[26] Very good examples of this type of volcano can be seen in Iceland and in British Columbia. The origin of the term comes from Tuya Butte, which is one of the several tuyas in the area of the Tuya River and Tuya Range in northern British Columbia. Tuya Butte was the first such landform analyzed and so its name has entered the geological literature for this kind of volcanic formation.[27] The Tuya Mountains Provincial Park was recently established to protect this unusual landscape, which lies north of Tuya Lake and south of the Jennings River near the boundary with the Yukon Territory.

Mud volcanoes

Mud volcanoes (mud domes) are formations created by geo-excreted liquids and gases, although there are several processes which may cause such activity.[28] The largest structures are 10 kilometers in diameter and reach 700 meters high.[29]

Erupted material

The Stromboli stratovolcano off the coast of Sicily has erupted continuously for thousands of years, giving rise to its nickname «Lighthouse of the Mediterranean».

The material that is expelled in a volcanic eruption can be classified into three types:

- Volcanic gases, a mixture made mostly of steam, carbon dioxide, and a sulfur compound (either sulfur dioxide, SO2, or hydrogen sulfide, H2S, depending on the temperature)

- Lava, the name of magma when it emerges and flows over the surface

- Tephra, particles of solid material of all shapes and sizes ejected and thrown through the air[30][31]

Volcanic gases

The concentrations of different volcanic gases can vary considerably from one volcano to the next. Water vapor is typically the most abundant volcanic gas, followed by carbon dioxide[32] and sulfur dioxide. Other principal volcanic gases include hydrogen sulfide, hydrogen chloride, and hydrogen fluoride. A large number of minor and trace gases are also found in volcanic emissions, for example hydrogen, carbon monoxide, halocarbons, organic compounds, and volatile metal chlorides.

Lava flows

The form and style of eruption of a volcano is largely determined by the composition of the lava it erupts. The viscosity (how fluid the lava is) and the amount of dissolved gas are the most important characteristics of magma, and both are largely determined by the amount of silica in the magma. Magma rich in silica is much more viscous than silica-poor magma, and silica-rich magma also tends to contain more dissolved gases.

Lava can be broadly classified into four different compositions:[33]

- If the erupted magma contains a high percentage (>63%) of silica, the lava is described as felsic. Felsic lavas (dacites or rhyolites) are highly viscous and are erupted as domes or short, stubby flows.[34] Lassen Peak in California is an example of a volcano formed from felsic lava and is actually a large lava dome.[35]

- Because felsic magmas are so viscous, they tend to trap volatiles (gases) that are present, which leads to explosive volcanism. Pyroclastic flows (ignimbrites) are highly hazardous products of such volcanoes, since they hug the volcano’s slopes and travel far from their vents during large eruptions. Temperatures as high as 850 °C (1,560 °F)[36] are known to occur in pyroclastic flows, which will incinerate everything flammable in their path, and thick layers of hot pyroclastic flow deposits can be laid down, often many meters thick.[37] Alaska’s Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, formed by the eruption of Novarupta near Katmai in 1912, is an example of a thick pyroclastic flow or ignimbrite deposit.[38] Volcanic ash that is light enough to be erupted high into the Earth’s atmosphere as an eruption column may travel hundreds of kilometers before it falls back to ground as a fallout tuff. Volcanic gases may remain in the stratosphere for years.[39]

- Felsic magmas are formed within the crust, usually through melting of crust rock from the heat of underlying mafic magmas. The lighter felsic magma floats on the mafic magma without significant mixing.[40] Less commonly, felsic magmas are produced by extreme fractional crystallization of more mafic magmas.[41] This is a process in which mafic minerals crystallize out of the slowly cooling magma, which enriches the remaining liquid in silica.

- If the erupted magma contains 52–63% silica, the lava is of intermediate composition or andesitic. Intermediate magmas are characteristic of stratovolcanoes.[42] They are most commonly formed at convergent boundaries between tectonic plates, by several processes. One process is hydration melting of mantle peridotite followed by fractional crystallization. Water from a subducting slab rises into the overlying mantle, lowering its melting point, particularly for the more silica-rich minerals. Fractional crystallization further enriches the magma in silica. It has also been suggested that intermediate magmas are produced by melting of sediments carried downwards by the subducted slab.[43] Another process is magma mixing between felsic rhyolitic and mafic basaltic magmas in an intermediate reservoir prior to emplacement or lava flow.[44]

- If the erupted magma contains <52% and >45% silica, the lava is called mafic (because it contains higher percentages of magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe)) or basaltic. These lavas are usually hotter and much less viscous than felsic lavas. Mafic magmas are formed by partial melting of dry mantle, with limited fractional crystallization and assimilation of crustal material.[45]

- Mafic lavas occur in a wide range of settings. These include mid-ocean ridges; Shield volcanoes (such the Hawaiian Islands, including Mauna Loa and Kilauea), on both oceanic and continental crust; and as continental flood basalts.

- Some erupted magmas contain ≤45% silica and produce ultramafic lava. Ultramafic flows, also known as komatiites, are very rare; indeed, very few have been erupted at the Earth’s surface since the Proterozoic, when the planet’s heat flow was higher. They are (or were) the hottest lavas, and were probably more fluid than common mafic lavas, with a viscosity less than a tenth that of hot basalt magma.[46]

Mafic lava flows show two varieties of surface texture: ʻAʻa (pronounced [ˈʔaʔa]) and pāhoehoe ([paːˈho.eˈho.e]), both Hawaiian words. ʻAʻa is characterized by a rough, clinkery surface and is the typical texture of cooler basalt lava flows. Pāhoehoe is characterized by its smooth and often ropey or wrinkly surface and is generally formed from more fluid lava flows. Pāhoehoe flows are sometimes observed to transition to ʻaʻa flows as they move away from the vent, but never the reverse.[47]

More silicic lava flows take the form of block lava, where the flow is covered with angular, vesicle-poor blocks. Rhyolitic flows typically consist largely of obsidian.[48]

Tephra

Light-microscope image of tuff as seen in thin section (long dimension is several mm): the curved shapes of altered glass shards (ash fragments) are well preserved, although the glass is partly altered. The shapes were formed around bubbles of expanding, water-rich gas.

Tephra is made when magma inside the volcano is blown apart by the rapid expansion of hot volcanic gases. Magma commonly explodes as the gas dissolved in it comes out of solution as the pressure decreases when it flows to the surface. These violent explosions produce particles of material that can then fly from the volcano. Solid particles smaller than 2 mm in diameter (sand-sized or smaller) are called volcanic ash.[30][31]

Tephra and other volcaniclastics (shattered volcanic material) make up more of the volume of many volcanoes than do lava flows. Volcaniclastics may have contributed as much as a third of all sedimentation in the geologic record. The production of large volumes of tephra is characteristic of explosive volcanism.[49]

Types of volcanic eruptions

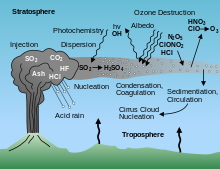

Schematic of volcano injection of aerosols and gases

Eruption styles are broadly divided into magmatic, phreatomagmatic, and phreatic eruptions.[50] The intensity of explosive volcanism is expressed using the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which ranges from 0 for Hawaiian-type eruptions to 8 for supervolcanic eruptions.[51]

- Magmatic eruptions are driven primarily by gas release due to decompression.[50] Low-viscosity magma with little dissolved gas produces relatively gentle effusive eruptions. High-viscosity magma with a high content of dissolved gas produces violent explosive eruptions. The range of observed eruption styles is expressed from historical examples.

- Hawaiian eruptions are typical of volcanoes that erupt mafic lava with a relatively low gas content. These are almost entirely effusive, producing local fire fountains and highly fluid lava flows but relatively little tephra. They are named after the Hawaiian volcanoes.

- Strombolian eruptions are characterized by moderate viscosities and dissolved gas levels. They are characterized by frequent but short-lived eruptions that can produce eruptive columns hundreds of meters high. Their primary product is scoria. They are named after Stromboli.

- Vulcanian eruptions are characterized by yet higher viscosities and partial crystallization of magma, which is often intermediate in composition. Eruptions take the form of short-lived explosions over the course of several hours, which destroy a central dome and eject large lava blocks and bombs. This is followed by an effusive phase that rebuilds the central dome. Vulcanian eruptions are named after Vulcano.

- Peléan eruptions are more violent still, being characterized by dome growth and collapse that produces various kinds of pyroclastic flows. They are named after Mount Pelée.

- Plinian eruptions are the most violent of all volcanic eruptions. They are characterized by sustained huge eruption columns whose collapse produces catastrophic pyroclastic flows. They are named after Pliny the Younger, who chronicled the Plinian eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

- Phreatomagmatic eruptions are characterized by interaction of rising magma with groundwater. They are driven by the resulting rapid buildup of pressure in the superheated groundwater.

- Phreatic eruptions are characterized by superheating of groundwater that comes in contact with hot rock or magma. They are distinguished from phreatomagmatic eruptions because the erupted material is all country rock; no magma is erupted.

Volcanic activity

As of December 2022, the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program database of volcanic eruptions in the Holocene Epoch (the last 11,700 years) lists 9,901 confirmed eruptions from 859 volcanoes. The database also lists 1,113 uncertain eruptions and 168 discredited eruptions for the same time interval.[52][53]

Volcanoes vary greatly in their level of activity, with individual volcanic systems having an eruption recurrence ranging from several times a year to once in tens of thousands of years.[54] Volcanoes are informally described as erupting, active, dormant, or extinct, but the definitions of these terms are not entirely uniform amongst volcanologists. The level of activity of most volcanoes falls upon a graduated spectrum, with much overlap between categories, and does not always fit neatly into only one of these three separate categories.[55]

Erupting

The USGS defines a volcano as «erupting» whenever the ejection of magma from any point on the volcano is visible, including visible magma still contained within the walls of the summit crater.

Active

While there is no international consensus among volcanologists on how to define an «active» volcano, the USGS defines a volcano as «active» whenever subterranean indicators, such as earthquake swarms, ground inflation, or unusually high levels of carbon dioxide and/or sulfur dioxide are present.[56][57]

Dormant and reactivated

The USGS defines a «dormant volcano» as Any volcano that is not showing any signs of unrest such as earthquake swarms, ground swelling, or excessive noxious gas emissions, but which shows signs that it could yet become active again.[57] Many dormant volcanoes have not erupted for thousands of years, but have still shown signs that they may be likely to erupt again in the future.[58][59]

In an article justifying the re-classification of Alaska’s Mount Edgecumbe volcano from «dormant» to «active», volcanologists at the Alaska Volcano Observatory pointed out that the term «dormant» in reference to volcanoes has been deprecated over the past few decades and that «[t]he term «dormant volcano» is so little used and undefined in modern volcanology that the Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (2000) does not contain it in the glossaries or index,»[60] however the USGS still widely employs the term.

Previously a volcano was often considered to be extinct if there were no written records of its activity. With modern volcanic activity monitoring techniques, it is now understood that volcanoes may remain dormant for a long period of time, and then become unexpectedly active again. For example, Yellowstone has a repose/recharge period of around 700,000 years, and Toba of around 380,000 years.[61] Vesuvius was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards before its eruption of 79 CE, which destroyed the towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii.

It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between an extinct volcano and a dormant (inactive) one. Pinatubo was an inconspicuous volcano, unknown to most people in the surrounding areas, and initially not seismically monitored before its unanticipated and catastrophic eruption of 1991. Two other examples of volcanoes which were once thought to be extinct, before springing back into eruptive activity were the long-dormant Soufrière Hills volcano on the island of Montserrat, thought to be extinct until activity resumed in 1995 (turning its capital Plymouth into a ghost town) and Fourpeaked Mountain in Alaska, which, before its September 2006 eruption, had not erupted since before 8000 BCE.

Extinct

Extinct volcanoes are those that scientists consider unlikely to erupt again because the volcano no longer has a magma supply. Examples of extinct volcanoes are many volcanoes on the Hawaiian – Emperor seamount chain in the Pacific Ocean (although some volcanoes at the eastern end of the chain are active), Hohentwiel in Germany, Shiprock in New Mexico, US, Capulin in New Mexico, US, Zuidwal volcano in the Netherlands, and many volcanoes in Italy such as Monte Vulture. Edinburgh Castle in Scotland is located atop an extinct volcano, which forms Castle Rock. Whether a volcano is truly extinct is often difficult to determine. Since «supervolcano» calderas can have eruptive lifespans sometimes measured in millions of years, a caldera that has not produced an eruption in tens of thousands of years may be considered dormant instead of extinct.

Volcanic-alert level

The three common popular classifications of volcanoes can be subjective and some volcanoes thought to have been extinct have erupted again. To help prevent people from falsely believing they are not at risk when living on or near a volcano, countries have adopted new classifications to describe the various levels and stages of volcanic activity.[62] Some alert systems use different numbers or colors to designate the different stages. Other systems use colors and words. Some systems use a combination of both.

Decade volcanoes

The Decade Volcanoes are 16 volcanoes identified by the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI) as being worthy of particular study in light of their history of large, destructive eruptions and proximity to populated areas. They are named Decade Volcanoes because the project was initiated as part of the United Nations-sponsored International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (the 1990s). The 16 current Decade Volcanoes are:

- Avachinsky-Koryaksky (grouped together), Kamchatka, Russia

- Nevado de Colima, Jalisco and Colima, Mexico

- Mount Etna, Sicily, Italy

- Galeras, Nariño, Colombia

- Mauna Loa, Hawaii, US

- Mount Merapi, Central Java, Indonesia

- Mount Nyiragongo, Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Mount Rainier, Washington, US

- Sakurajima, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan

- Santa Maria/Santiaguito, Guatemala

- Santorini, Cyclades, Greece

- Taal Volcano, Luzon, Philippines

- Teide, Canary Islands, Spain

- Ulawun, New Britain, Papua New Guinea

- Mount Unzen, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan

- Vesuvius, Naples, Italy

The Deep Earth Carbon Degassing Project, an initiative of the Deep Carbon Observatory, monitors nine volcanoes, two of which are Decade volcanoes. The focus of the Deep Earth Carbon Degassing Project is to use Multi-Component Gas Analyzer System instruments to measure CO2/SO2 ratios in real-time and in high-resolution to allow detection of the pre-eruptive degassing of rising magmas, improving prediction of volcanic activity.[63]

Volcanoes and humans

Solar radiation graph 1958–2008, showing how the radiation is reduced after major volcanic eruptions

Volcanic eruptions pose a significant threat to human civilization. However, volcanic activity has also provided humans with important resources.

Hazards

There are many different types of volcanic eruptions and associated activity: phreatic eruptions (steam-generated eruptions), explosive eruption of high-silica lava (e.g., rhyolite), effusive eruption of low-silica lava (e.g., basalt), sector collapses, pyroclastic flows, lahars (debris flow) and carbon dioxide emission. All of these activities can pose a hazard to humans. Earthquakes, hot springs, fumaroles, mud pots and geysers often accompany volcanic activity.

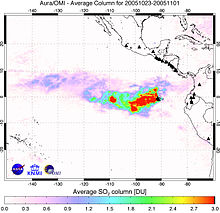

Volcanic gases can reach the stratosphere, where they form sulfuric acid aerosols that can reflect solar radiation and lower surface temperatures significantly.[64] Sulfur dioxide from the eruption of Huaynaputina may have caused the Russian famine of 1601–1603.[65] Chemical reactions of sulfate aerosols in the stratosphere can also damage the ozone layer, and acids such as hydrogen chloride (HCl) and hydrogen fluoride (HF) can fall to the ground as acid rain. Explosive volcanic eruptions release the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide and thus provide a deep source of carbon for biogeochemical cycles.[66]

Ash thrown into the air by eruptions can present a hazard to aircraft, especially jet aircraft where the particles can be melted by the high operating temperature; the melted particles then adhere to the turbine blades and alter their shape, disrupting the operation of the turbine. This can cause major disruptions to air travel.

Comparison of major United States supereruptions (VEI 7 and

A volcanic winter is thought to have taken place around 70,000 years ago after the supereruption of Lake Toba on Sumatra island in Indonesia,[67] This may have created a population bottleneck that affected the genetic inheritance of all humans today.[68] Volcanic eruptions may have contributed to major extinction events, such as the End-Ordovician, Permian-Triassic, and Late Devonian mass extinctions.[69]

The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora created global climate anomalies that became known as the «Year Without a Summer» because of the effect on North American and European weather.[70] The freezing winter of 1740–41, which led to widespread famine in northern Europe, may also owe its origins to a volcanic eruption.[71]

Benefits

Although volcanic eruptions pose considerable hazards to humans, past volcanic activity has created important economic resources. Tuff formed from volcanic ash is a relatively soft rock, and it has been used for construction since ancient times.[72][73] The Romans often used tuff, which is abundant in Italy, for construction.[74] The Rapa Nui people used tuff to make most of the moai statues in Easter Island.[75]

Volcanic ash and weathered basalt produce some of the most fertile soil in the world, rich in nutrients such as iron, magnesium, potassium, calcium, and phosphorus.[76] Volcanic activity is responsible for emplacing valuable mineral resources, such as metal ores.[76] It is accompanied by high rates of heat flow from the Earth’s interior. These can be tapped as geothermal power.[76]

Safety considerations

Many volcanoes near human settlements are heavily monitored with the aim of providing adequate advance warnings of imminent eruptions to nearby populations. Also, a better modern-day understanding of volcanology has led to some better informed governmental responses to unanticipated volcanic activities. While the science of volcanology may not yet be capable of predicting the exact times and dates of eruptions far into the future, on suitably monitored volcanoes the monitoring of ongoing volcanic indicators is generally capable of predicting imminent eruptions with advance warnings minimally of hours, and usually of days prior to any imminent eruptions.[77]

Thus in many cases, while volcanic eruptions may still cause major property destruction, the periodic large-scale loss of human life that was once associated with many volcanic eruptions has recently been significantly reduced in areas where volcanoes are adequately monitored. This life-saving ability is derived via such volcanic-activity monitoring programs, through the greater abilities of local officials to facilitate timely evacuations based upon the greater modern-day knowledge of volcanism that is now available, and upon improved communications technologies such as cell phones. Such operations tend to provide enough time for humans to escape at least with their lives prior to a pending eruption. One example of such a recent successful volcanic evacuation was the Mount Pinatubo evacuation of 1991. This evacuation is believed to have saved 20,000 lives.[78]

Citizens who may be concerned about their own exposure to risk from nearby volcanic activity should familiarize themselves with the types of, and quality of, volcano monitoring and public notification procedures being employed by governmental authorities in their areas.[79]

Volcanoes on other celestial bodies

The Tvashtar volcano erupts a plume 330 km (205 mi) above the surface of Jupiter’s moon Io.

The Earth’s Moon has no large volcanoes and no current volcanic activity, although recent evidence suggests it may still possess a partially molten core.[80] However, the Moon does have many volcanic features such as maria (the darker patches seen on the Moon), rilles and domes.[citation needed]

The planet Venus has a surface that is 90% basalt, indicating that volcanism played a major role in shaping its surface. The planet may have had a major global resurfacing event about 500 million years ago,[81] from what scientists can tell from the density of impact craters on the surface. Lava flows are widespread and forms of volcanism not present on Earth occur as well. Changes in the planet’s atmosphere and observations of lightning have been attributed to ongoing volcanic eruptions, although there is no confirmation of whether or not Venus is still volcanically active. However, radar sounding by the Magellan probe revealed evidence for comparatively recent volcanic activity at Venus’s highest volcano Maat Mons, in the form of ash flows near the summit and on the northern flank.[82] However, the interpretation of the flows as ash flows has been questioned.[83]

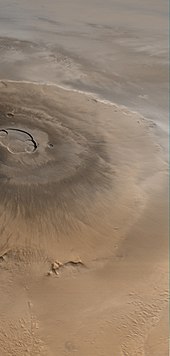

There are several extinct volcanoes on Mars, four of which are vast shield volcanoes far bigger than any on Earth. They include Arsia Mons, Ascraeus Mons, Hecates Tholus, Olympus Mons, and Pavonis Mons. These volcanoes have been extinct for many millions of years,[84] but the European Mars Express spacecraft has found evidence that volcanic activity may have occurred on Mars in the recent past as well.[84]

Jupiter’s moon Io is the most volcanically active object in the Solar System because of tidal interaction with Jupiter. It is covered with volcanoes that erupt sulfur, sulfur dioxide and silicate rock, and as a result, Io is constantly being resurfaced. Its lavas are the hottest known anywhere in the Solar System, with temperatures exceeding 1,800 K (1,500 °C). In February 2001, the largest recorded volcanic eruptions in the Solar System occurred on Io.[85] Europa, the smallest of Jupiter’s Galilean moons, also appears to have an active volcanic system, except that its volcanic activity is entirely in the form of water, which freezes into ice on the frigid surface. This process is known as cryovolcanism, and is apparently most common on the moons of the outer planets of the Solar System.[citation needed]

In 1989, the Voyager 2 spacecraft observed cryovolcanoes (ice volcanoes) on Triton, a moon of Neptune, and in 2005 the Cassini–Huygens probe photographed fountains of frozen particles erupting from Enceladus, a moon of Saturn.[86][87] The ejecta may be composed of water, liquid nitrogen, ammonia, dust, or methane compounds. Cassini–Huygens also found evidence of a methane-spewing cryovolcano on the Saturnian moon Titan, which is believed to be a significant source of the methane found in its atmosphere.[88] It is theorized that cryovolcanism may also be present on the Kuiper Belt Object Quaoar.

A 2010 study of the exoplanet COROT-7b, which was detected by transit in 2009, suggested that tidal heating from the host star very close to the planet and neighboring planets could generate intense volcanic activity similar to that found on Io.[89]

History of volcanology

Many ancient accounts ascribe volcanic eruptions to supernatural causes, such as the actions of gods or demigods. To the ancient Greeks, volcanoes’ capricious power could only be explained as acts of the gods, while 16th/17th-century German astronomer Johannes Kepler believed they were ducts for the Earth’s tears.[90] One early idea counter to this was proposed by Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), who witnessed eruptions of Mount Etna and Stromboli, then visited the crater of Vesuvius and published his view of an Earth with a central fire connected to numerous others caused by the burning of sulfur, bitumen and coal.[citation needed]

Various explanations were proposed for volcano behavior before the modern understanding of the Earth’s mantle structure as a semisolid material was developed.[citation needed] For decades after awareness that compression and radioactive materials may be heat sources, their contributions were specifically discounted. Volcanic action was often attributed to chemical reactions and a thin layer of molten rock near the surface.[citation needed]

See also

- List of extraterrestrial volcanoes

- List of volcanic eruptions by death toll

- Maritime impacts of volcanic eruptions

- Prediction of volcanic activity – Research to predict volcanic activity

- Timeline of volcanism on Earth

- Volcano Number – unique identifier for a volcano or related feature

- Volcano observatory – location used for monitoring and conducting research on volcanoes

References

- ^ Rampino, M R; Self, S; Stothers, R B (May 1988). «Volcanic Winters». Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 16 (1): 73–99. Bibcode:1988AREPS..16…73R. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.16.050188.000445.

- ^ Xu, Ru; Xiao, Zhiyong; Wang, Yichen; Xu, Rui (August 24, 2022). «Pitted-Ground Volcanoes on Mercury». Remote Sensing. 14 (17): 4164. Bibcode:2022RemS…14.4164X. doi:10.3390/rs14174164. ISSN 2072-4292.

- ^ Young, Davis A. (2003). «Volcano». Mind over Magma: The Story of Igneous Petrology. Archived from the original on November 12, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ «Vulcanology». Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Schmincke, Hans-Ulrich (2003). Volcanism. Berlin: Springer. pp. 13–20. ISBN 9783540436508.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, pp. 17–18, 276.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, pp. 18, 113–126.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, pp. 18, 106–107.

- ^ Foulger, Gillian R. (2010). Plates vs. Plumes: A Geological Controversy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6148-0.

- ^ Philpotts, Anthony R.; Ague, Jay J. (2009). Principles of igneous and metamorphic petrology (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–384, 390. ISBN 9780521880060.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, pp. 390–394, 396–397.

- ^ Wood, C.A. (1979). «Cindercones on Earth, Moon and Mars». Lunar and Planetary Science. X: 1370–1372. Bibcode:1979LPI….10.1370W.

- ^ Meresse, S.; Costard, F.O.; Mangold, N.; Masson, P.; Neukum, G. (2008). «Formation and evolution of the chaotic terrains by subsidence and magmatism: Hydraotes Chaos, Mars». Icarus. 194 (2): 487. Bibcode:2008Icar..194..487M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.10.023.

- ^ Brož, P.; Hauber, E. (2012). «A unique volcanic field in Tharsis, Mars: Pyroclastic cones as evidence for explosive eruptions». Icarus. 218 (1): 88. Bibcode:2012Icar..218…88B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.11.030.

- ^ Lawrence, S.J.; Stopar, J.D.; Hawke, B.R.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Cahill, J.T.S.; Bandfield, J.L.; Jolliff, B.L.; Denevi, B.W.; Robinson, M.S.; Glotch, T.D.; Bussey, D.B.J.; Spudis, P.D.; Giguere, T.A.; Garry, W.B. (2013). «LRO observations of morphology and surface roughness of volcanic cones and lobate lava flows in the Marius Hills». Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 118 (4): 615. Bibcode:2013JGRE..118..615L. doi:10.1002/jgre.20060.

- ^ Lockwood, John P.; Hazlett, Richard W. (2010). Volcanoes: Global Perspectives. p. 552. ISBN 978-1-4051-6250-0.

- ^ Berger, Melvin, Gilda Berger, and Higgins Bond. «Volcanoes-why and how .» Why do volcanoes blow their tops?: Questions and answers about volcanoes and earthquakes. New York: Scholastic, 1999. 7. Print.

- ^ «Questions About Supervolcanoes». Volcanic Hazards Program. USGS Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Francis, Peter (1983). «Giant Volcanic Calderas». Scientific American. 248 (6): 60–73. Bibcode:1983SciAm.248f..60F. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0683-60. JSTOR 24968920.

- ^ Venzke, E., ed. (2013). «Holocene Volcano List». Global Volcanism Program Volcanoes of the World (version 4.9.1). Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Venzke, E., ed. (2013). «How many active volcanoes are there?». Global Volcanism Program Volcanoes of the World (version 4.9.1). Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Ashley Strickland (January 10, 2020). «Origin of mystery humming noises heard around the world, uncovered». CNN.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 66.

- ^ Allaby, Michael, ed. (July 4, 2013). «Tuya». A dictionary of geology and earth sciences (Fourth ed.). Oxford. ISBN 9780199653065.

- ^ Mathews, W. H. (September 1, 1947). «Tuyas, flat-topped volcanoes in northern British Columbia». American Journal of Science. 245 (9): 560–570. Bibcode:1947AmJS..245..560M. doi:10.2475/ajs.245.9.560.

- ^ Mazzini, Adriano; Etiope, Giuseppe (May 2017). «Mud volcanism: An updated review». Earth-Science Reviews. 168: 81–112. Bibcode:2017ESRv..168…81M. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.03.001. hdl:10852/61234.

- ^ Kioka, Arata; Ashi, Juichiro (October 28, 2015). «Episodic massive mud eruptions from submarine mud volcanoes examined through topographical signatures». Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (20): 8406–8414. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.8406K. doi:10.1002/2015GL065713.

- ^ a b

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Tuff». Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Schmidt, R. (1981). «Descriptive nomenclature and classification of pyroclastic deposits and fragments: recommendations of the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks». Geology. 9: 41–43. doi:10.1007/BF01822152. S2CID 128375559. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Pedone, M.; Aiuppa, A.; Giudice, G.; Grassa, F.; Francofonte, V.; Bergsson, B.; Ilyinskaya, E. (2014). «Tunable diode laser measurements of hydrothermal/volcanic CO2 and implications for the global CO2 budget». Solid Earth. 5 (2): 1209–1221. Bibcode:2014SolE….5.1209P. doi:10.5194/se-5-1209-2014.

- ^ Casq, R.A.F.; Wright, J.V. (1987). Volcanic Successions. Unwin Hyman Inc. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-04-552022-0.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 70-72.

- ^ «Volcanoes». Lassen Volcanic National Park California. National Park Service. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Richard V.; Schmincke, H.-U. (1984). Pyroclastic rocks. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 210–211. ISBN 3540127569.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 73-77.

- ^ «Exploring the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes». Katmai National Park and Preserve, Alaska. National Park Service. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, p. 229.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 378.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Castro, Antonio (January 2014). «The off-crust origin of granite batholiths». Geoscience Frontiers. 5 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2013.06.006.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 377.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Schmincke 2003, pp. 132.

- ^ Fisher & Schmincke 1984, p. 89.

- ^ a b Heiken, G. & Wohletz, K. Volcanic Ash. University of California Press. p. 246.

- ^ Newhall, Christopher G.; Self, Stephen (1982). «The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI): An Estimate of Explosive Magnitude for Historical Volcanism» (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 87 (C2): 1231–1238. Bibcode:1982JGR….87.1231N. doi:10.1029/JC087iC02p01231. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2013.

- ^ Venzke, E. (compiler) (December 19, 2022). Venzke, Edward (ed.). «Database Search». Volcanoes of the World (Version 5.0.1). Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program. doi:10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW5-2022.5.0. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Venzke, E. (compiler) (December 19, 2022). Venzke, Edward (ed.). «How many active volcanoes are there?». Volcanoes of the World (Version 5.0.1). Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program. doi:10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW5-2022.5.0. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Martí Molist, Joan (September 6, 2017). «Assessing Volcanic Hazard». Oxford Handbook Topics in Physical Sciences. Vol. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190699420.013.32. ISBN 978-0-19-069942-0.

- ^ Pariona, Amber (September 19, 2019). «Difference Between an Active, Dormant, and Extinct Volcano». WorldAtlas.com. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Kilauea eruption confined to crater Archived July 17, 2022, at the Wayback Machine usgs.gov. Updated 24 July 2022. Downloaded 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b How We Tell if a Volcano Is Active, Dormant, or Extinct Archived July 25, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Wired. 15 August 2015. By Erik Klimetti. Downloaded 24 July 2022.

- ^ Nelson, Stephen A. (October 4, 2016). «Volcanic Hazards & Prediction of Volcanic Eruptions». Tulane University. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ «How is a volcano defined as being active, dormant, or extinct?». Volcano World. Oregon State University. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ «Mount Edgecumbe volcanic field changes from ‘dormant’ to ‘active’ — what does that mean?». Alaska Volcano Observatory. Alaska Volcano Observatory. May 9, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Chesner, C.A.; Rose, J.A.; Deino, W.I.; Drake, R.; Westgate, A. (March 1991). «Eruptive History of Earth’s Largest Quaternary caldera (Toba, Indonesia) Clarified» (PDF). Geology. 19 (3): 200–203. Bibcode:1991Geo….19..200C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0200:EHOESL>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ «Volcanic Alert Levels of Various Countries». Volcanolive.com. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ Aiuppa, Alessandro; Moretti, Roberto; Federico, Cinzia; Giudice, Gaetano; Gurrieri, Sergio; Liuzzo, Marco; Papale, Paolo; Shinohara, Hiroshi; Valenza, Mariano (2007). «Forecasting Etna eruptions by real-time observation of volcanic gas composition». Geology. 35 (12): 1115–1118. Bibcode:2007Geo….35.1115A. doi:10.1130/G24149A.1.

- ^ Miles, M.G.; Grainger, R.G.; Highwood, E.J. (2004). «The significance of volcanic eruption strength and frequency for climate» (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 130 (602): 2361–2376. Bibcode:2004QJRMS.130.2361M. doi:10.1256/qj.03.60. S2CID 53005926.

- ^ University of California – Davis (April 25, 2008). «Volcanic Eruption Of 1600 Caused Global Disruption». ScienceDaily.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: McGee, Kenneth A.; Doukas, Michael P.; Kessler, Richard; Gerlach, Terrence M. (May 1997). «Impacts of Volcanic Gases on Climate, the Environment, and People». United States Geological Survey. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ «Supervolcano eruption – in Sumatra – deforested India 73,000 years ago». ScienceDaily. November 24, 2009.

- ^ «When humans faced extinction». BBC. June 9, 2003. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- ^ O’Hanlon, Larry (March 14, 2005). «Yellowstone’s Super Sister». Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on March 14, 2005.

- ^ Volcanoes in human history: the far-reaching effects of major eruptions. Jelle Zeilinga de Boer, Donald Theodore Sanders (2002). Princeton University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-691-05081-3

- ^ Ó Gráda, Cormac (February 6, 2009). «Famine: A Short History». Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016.

- ^ Marcari, G., G. Fabbrocino, and G. Manfredi. «Shear seismic capacity of tuff masonry panels in heritage constructions.» Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture X 95 (2007): 73.

- ^ Dolan, S.G.; Cates, K.M.; Conrad, C.N.; Copeland, S.R. (March 14, 2019). «Home Away from Home: Ancestral Pueblo Fieldhouses in the Northern Rio Grande». Lanl-Ur. 19–21132: 96. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, M. D.; Marra, F.; Hay, R. L.; Cawood, C.; Winkler, E. M. (2005). «The Judicious Selection and Preservation of Tuff and Travertine Building Stone in Ancient Rome*». Archaeometry. 47 (3): 485–510. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2005.00215.x.

- ^ Richards, Colin. 2016. «Making Moai: Reconsidering Concepts of Risk in the Construction of Megalithic Architecture in Rapa Nui (Easter Island)» Archived November 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Rapa Nui–Easter Island: Cultural and Historical Perspectives, pp.150-151

- ^ a b c Kiprop, Joseph (January 18, 2019). «Why Is Volcanic Soil Fertile?». WorldAtlas.com. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Volcano Safety Tips Archived July 25, 2022, at the Wayback Machine National Geographic. By Maya Wei-Haas. 2015. Downloaded 24 June 2022.

- ^ Pinatubo: Why the Biggest Volcanic Eruption Wasn’t the Deadliest Archived July 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine LiveScience. By Stephanie Pappas. 15 June 2011. Downloaded 25 July 2022.

- ^ About to blow: Are we ready for the next volcanic catastrophe? Archived August 17, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Courthouse News Service. By Candace Cheung. 17 August 2022. Downloaded 17 August, 2022.

- ^ Wieczorek, Mark A.; Jolliff, Bradley L.; Khan, Amir; Pritchard, Matthew E.; Weiss, Benjamin P.; Williams, James G.; Hood, Lon L.; Righter, Kevin; Neal, Clive R.; Shearer, Charles K.; McCallum, I. Stewart; Tompkins, Stephanie; Hawke, B. Ray; Peterson, Chris; Gillis, Jeffrey J.; Bussey, Ben (January 1, 2006). «The constitution and structure of the lunar interior». Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 60 (1): 221–364. Bibcode:2006RvMG…60..221W. doi:10.2138/rmg.2006.60.3. S2CID 130734866.

- ^ Bindschadler, D.L. (1995). «Magellan: A new view of Venus’ geology and geophysics». Reviews of Geophysics. 33 (S1): 459. Bibcode:1995RvGeo..33S.459B. doi:10.1029/95RG00281.

- ^ Robinson, Cordula A.; Thornhill, Gill D.; Parfitt, Elisabeth A. (1995). «Large-scale volcanic activity at Maat Mons: Can this explain fluctuations in atmospheric chemistry observed by Pioneer Venus?». Journal of Geophysical Research. 100 (E6): 11755. Bibcode:1995JGR…10011755R. doi:10.1029/95JE00147.

- ^ Mouginis-Mark, Peter J. (October 2016). «Geomorphology and volcanology of Maat Mons, Venus». Icarus. 277: 433–441. Bibcode:2016Icar..277..433M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.022.

- ^ a b «Glacial, volcanic and fluvial activity on Mars: latest images». European Space Agency. February 25, 2005. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ «Exceptionally bright eruption on Io rivals largest in solar system». W.M. Keck Observatory. November 13, 2002. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ «Cassini Finds an Atmosphere on Saturn’s Moon Enceladus». PPARC. March 16, 2005. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Yvette (March 15, 2012). «Enceladus, Saturn’s Moon». Image of the Day Gallery. NASA. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ «Hydrocarbon volcano discovered on Titan». Newscientist.com. June 8, 2005. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Jaggard, Victoria (February 5, 2010). ««Super Earth» May Really Be New Planet Type: Super-Io». National Geographic web site daily news. National Geographic Society. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Williams, Micheal (November 2007). «Hearts of fire». Morning Calm (11–2007): 6.

Further reading

- Macdonald, Gordon; Abbott, Agatin (1970). Volcanoes in the Sea: The Geology of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-870-22495-9.

- Marti, Joan & Ernst, Gerald. (2005). Volcanoes and the Environment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59254-3.

- Ollier, Cliff (1969). Volcanoes. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-7081-0532-0.

- Sigurðsson, Haraldur, ed. (2015). The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (2 ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-385938-9. This is a reference aimed at geologists, but many articles are accessible to non-professionals.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Volcanoes.

- Volcanoes at Curlie

- U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency Volcano advice

- Volcano World

1

: a vent in the crust of the earth or another planet or a moon from which usually molten or hot rock and steam issue

also

: a hill or mountain composed wholly or in part of the ejected material

2

: something of explosively violent potential

Illustration of volcano

- 1 cinder cone

- 2 shield volcano

- 3 stratovolcano

Synonyms

Example Sentences

The volcano last erupted 25 years ago.

after months of tension the roommates’ living situation was a volcano

Recent Examples on the Web

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park has reopened more trails following the eruption of the world’s largest active volcano.

—

Perhaps this is why Etna is one of the world’s most active volcanos.

—

One of the world’s largest super volcanoes poses the potential to erupt with cataclysmic results for life on Earth, while experiencing about 3,000 mostly minor earthquakes each year.

—

Mauna Loa is the largest active volcano on the planet.

—

Mauna Loa, the world’s biggest active volcano, on Hawaii’s Big Island, erupted last month, after almost four quiet decades.

—

Mauna Loa, the world’s largest volcano, started erupting for the first time in nearly four decades on Nov. 27 and posed a threat to a major highway on Hawaii’s Big Island that connects the east and west sides of the island.

—

Where is Mauna Loa, the world’s largest active volcano, located?

—

Big Island are getting quite a show as Mauna Loa, the world’s largest active volcano, is spewing molten lava 150 feet in the air.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘volcano.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Italian or Spanish; Italian vulcano, from Spanish volcán, ultimately from Latin Volcanus Vulcan

First Known Use

1665, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Time Traveler

The first known use of volcano was

in 1665

Dictionary Entries Near volcano

Cite this Entry

“Volcano.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/volcano. Accessed 13 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on volcano

Last Updated:

5 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Scientific

- Cultural

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

[ vol-key-noh ]

/ vɒlˈkeɪ noʊ /

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun, plural vol·ca·noes, vol·ca·nos.

a vent in the earth’s crust through which lava, steam, ashes, etc., are expelled, either continuously or at irregular intervals.

a mountain or hill, usually having a cuplike crater at the summit, formed around such a vent from the ash and lava expelled through it.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of volcano

1605–15; <Italian <Latin Volcānus, variant of VulcānusVulcan

Words nearby volcano

volcaniclastic, volcanic pipe, volcanic tuff, volcanism, volcanize, volcano, volcanogenic, Volcano Islands, volcanology, Volcker, vole

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to volcano

alp, bluff, butte, cliff, crag, elevation, eminence, height, mesa, mount, palisade, peak, pike, precipice, range, ridge, sierra, tor, abundance, drift

How to use volcano in a sentence

-

Cassini’s instruments also detected the presence of silica, which can get mixed with water in undersea volcanoes.

-

It also includes active volcanoes such as the Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania, and the DallaFilla and Erta Ale in Ethiopia.

-

The Natural History Museum in London, England offers a guide to making your own model volcano at home.

-

In one of the most poignant scenes in her book, she is hiking on Mauna Kea — the next volcano over from Greene’s Mars habitat — and finds a fern growing amid the volcanic desolation.

-

He particularly likes this approach that linked cycles of pressure inside the volcano with weather conditions.

-

And as we left, spears of sunlight painted the top of the nearby volcano Galeras.

-

Standing on the edge of the Burfell volcano, you realize what a fragile construct modern civilization is.

-

It ends with Godzilla lured away from Tokyo with a bird call and trapped in a volcano.

-

When the volcano blew its top, thousands perished, immolated by fire, boiling magma, and ash.

-

This week they got Mike Tyson and Razor Ruddock over at the Mirage, where the fake volcano blows up every twenty minutes.

-

A volcano broke out in the island of St. George, one of the Azores.

-

Fujiyama, the noted volcano of Japan, is twelve thousand three hundred and sixty-five feet high.

-

And what was a mere laughing, crying child of a man like Aristide Pujol in front of a Ducksmith volcano?

-

Torrents of lava poured over the sides of the volcano and destroyed whole villages on the shores of the lake.

-

Outwardly cold, Sir Henry seemed to his youthful observer, who now knew him better, to resemble a volcano coated with ice.

British Dictionary definitions for volcano

noun plural -noes or -nos

an opening in the earth’s crust from which molten lava, rock fragments, ashes, dust, and gases are ejected from below the earth’s surface

a mountain formed from volcanic material ejected from a vent in a central crater

Word Origin for volcano

C17: from Italian, from Latin Volcānus Vulcan 1, whose forges were believed to be responsible for volcanic rumblings

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Scientific definitions for volcano

An opening in the Earth’s crust from which lava, ash, and hot gases flow or are ejected during an eruption.

A usually cone-shaped mountain formed by the materials issuing from such an opening. Volcanoes are usually associated with plate boundaries but can also occur within the interior areas of a tectonic plate. Their shape is directly related to the type of magma that flows from them-the more viscous the magma, the steeper the sides of the volcano.♦ A volcano composed of gently sloping sheets of basaltic lava from successive volcanic eruptions is called a shield volcano. The lava flows associated with shield volcanos, such as Mauna Loa, on Hawaii, are very fluid.♦ A volcano composed of steep, alternating layers of lava and pyroclastic materials, including ash, is called a stratovolcano. Stratovolcanos are associated with relatively viscous lava and with explosive eruptions. They are the most common form of large continental volcanos. Mount Vesuvius, Mount Fuji, and Mount St. Helens are stratovolcanos. Also called composite volcano See more at hot spot island arc tectonic boundary volcanic arc.

The American Heritage® Science Dictionary

Copyright © 2011. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Cultural definitions for volcano

A cone-shaped mountain or hill created by molten material that rises from the interior of the Earth to the surface.

notes for volcano

Volcanoes tend to occur along the edges of tectonic plates.

The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition

Copyright © 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

One volcano puts out more toxic gases — one volcano — than man makes in a whole year. And when you look at this ‘climate change,’ and when you look at the regular climate change that we all have in the world, we have warm and we have cooling spells.

John Raese

ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD VOLCANO

From Italian, from Latin VolcānusVulcan1, whose forges were believed to be responsible for volcanic rumblings.

Etymology is the study of the origin of words and their changes in structure and significance.

PRONUNCIATION OF VOLCANO

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF VOLCANO

Volcano is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES VOLCANO MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Volcano

A volcano is a rupture on the crust of a planetary mass object, such as the Earth, which allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface. Earth’s volcanoes occur because the planet’s crust is broken into 17 major, rigid tectonic plates that float on a hotter, softer layer in the Earth’s mantle. Therefore, on Earth, volcanoes are generally found where tectonic plates are diverging or converging. For example, a mid-oceanic ridge, such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has volcanoes caused by divergent tectonic plates pulling apart; the Pacific Ring of Fire has volcanoes caused by convergent tectonic plates coming together. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching and thinning of the crust’s interior plates, e.g., in the East African Rift and the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field and Rio Grande Rift in North America. This type of volcanism falls under the umbrella of «plate hypothesis» volcanism. Volcanism away from plate boundaries has also been explained as mantle plumes.

Definition of volcano in the English dictionary

The definition of volcano in the dictionary is an opening in the earth’s crust from which molten lava, rock fragments, ashes, dust, and gases are ejected from below the earth’s surface. Other definition of volcano is a mountain formed from volcanic material ejected from a vent in a central crater.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH VOLCANO

Synonyms and antonyms of volcano in the English dictionary of synonyms

Translation of «volcano» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF VOLCANO

Find out the translation of volcano to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of volcano from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «volcano» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

火山

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

volcán

570 millions of speakers

English

volcano

510 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

ज्वालामुखी

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

بُرْكان

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

вулкан

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

vulcão

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

আগ্নেয়গিরি

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

volcan

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Gunung berapi

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Vulkan

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

噴火口

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

화산

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Gunung geni

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

núi lửa

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

எரிமலை

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

ज्वालामुखी

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

volkan

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

vulcano

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

wulkan

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

вулкан

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

vulcan

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

ηφαίστειο

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

vulkaan

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

vulkan

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

vulkan

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of volcano

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «VOLCANO»

The term «volcano» is very widely used and occupies the 15.516 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Very widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «volcano» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of volcano

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «volcano».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «VOLCANO» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «volcano» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «volcano» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about volcano

10 QUOTES WITH «VOLCANO»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word volcano.

A democracy is a volcano which conceals the fiery materials of its own destruction. These will produce an eruption and carry desolation in their way.

There will be no funeral! Before I get too old and ill, I’ll go to South America and live among the Pemon people and meditate. When the time is right, they can throw my body into the volcano.

One of the most amazing locations I’ve ever been is the top of the volcano in Tanzania, Africa. It’s an actual volcano where you really have this lava every day.

All civilization has from time to time become a thin crust over a volcano of revolution.

There’s always an excitement around the Strip whenever something new being built. It was always the biggest and the best hotel or, you know, over-the-top things. And so, family would be coming in from out of town, and it was such a thrill to be showing them this, you know, erupting new volcano or whatever it was.

If your heart is a volcano, how shall you expect flowers to bloom?

First of all, there was a volcano of words, an eruption of words that Shakespeare had never used before that had never been used in the English language before. It’s astonishing. It pours out of him.

So when I read this story, it unlocked a volcano of unanswered questions, because the questions had never been asked. It was an opportunity to come to terms with the lot of repressed history — and history of repression.

I wrote a novel about Israelis who live their own lives on the slope of a volcano. Near a volcano one still falls in love, one still gets jealous, one still wants a promotion, one still gossips.

One volcano puts out more toxic gases — one volcano — than man makes in a whole year. And when you look at this ‘climate change,’ and when you look at the regular climate change that we all have in the world, we have warm and we have cooling spells.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «VOLCANO»

Discover the use of volcano in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to volcano and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

It is the Day of Death and the fiesta is in fullswing.

As the day wears on, it becomes apparent that Geoffrey must die. It is his only escape from a world he cannot understand. UNDER THE VOLCANO is one of the century’s great undisputed masterpieces.

An island people are fighting for their lives. La Palma’s Cumbre Vieja has erupted — soon ash and lava will annihilate everything, unless the locals can destroy the volcano first. A desperate group set out, armed with high explosives.

4

Super Volcano: The Ticking Time Bomb Beneath Yellowstone …

What will happen, in human terms, when it erupts? Greg Breining explores the shocking answer to this question and others in a scientific yet accessible look at the enormous natural disaster brewing beneath the surface of the United States.

Whenever thoughts pop into Louis’s head, he can’t control his mouth, and he ends up interrupting everybody.

6

Volcano Cowboys: The Rocky Evolution of a Dangerous Science

An absorbing exploration of the sometimes deadly science of volcanology shows how this steadily developing discipline has evolved since the Mt. St. Helens eruption and describes the dangerous conditions under which its researchers work.

7

Volcano and Geothermal Tourism: Sustainable Geo-resources …

This comprehensive book covers the most important issues of this growing tourism sector whilst incorporating relevant global research, making it an essential resource for all in the field. Includes colour plates.

Patricia Erfurt-Cooper, Malcolm Cooper, 2010

8

A Volcano in My Tummy: Helping Children to Handle Anger

A Volcano in My Tummy is about helping 6 to 15 year olds handle their anger so that they can live successfully, healthily, happily and nonviolently, with motivation, without fear and with good relationships.

Warwick Pudney, Éliane Whitehouse, 1996

Tom and Kevin are camping when they become trapped in the wilderness by an erupting volcano.

Burst into the fiery world of volcanoes with this perfect project workbook — includes two pages of funky stickersFully updated with pages of funky volcano stickers and even more games and activities, Eye Wonder Volcano is a fantastic guide …

Kindersley Dorling, Lisa Magloff, 2013

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «VOLCANO»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term volcano is used in the context of the following news items.

Volcanic ash prompts closure of Bali airport and three others in …

Jakarta, Indonesia (CNN) Ash spewing from an Indonesian volcano has brought chaos for travelers on the popular resort island of Bali and beyond, prompting … «CNN, Jul 15»

Residents flee as volcano erupts on Japanese island

Tokyo (CNN) Residents of the Japanese island of Kuchinoerabu have been urged to evacuate to get out of the path of an erupting volcano. Mount Shindake … «CNN, May 15»

Evacuation as Calbuco volcano erupts in Chile

The Calbuco volcano in southern Chile has erupted twice in the space of a few hours — having lain dormant for decades. Footage from the area shows a huge … «BBC News, Apr 15»

Chile’s Villarica Volcano Erupts, Forcing Thousands to Evacuate

SANTIAGO, Chile — A volcano in southern Chile erupted early Tuesday, spewing heavy smoke and lava and prompting officials to evacuate thousands of … «NBCNews.com, Mar 15»

Lava from Hawaii volcano destroys first house on Big Island (VIDEO)

A breakout occurs from an inflated lobe of the Kilauea volcano lava flow as seen in this U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) handout photo taken near the village of … «RT, Nov 14»

Hawaii volcano about to consume its first home, with lava meters away

This October 28, 2014 image provided by the US Geological Survey(USGS) shows the lava that has pushed through a fence marking a property boundary above … «RT, Oct 14»

Weather hits recovery of bodies from erupting Japanese volcano

The search for bodies from an erupting volcano in central Japan was suspended Thursday as weather conditions deteriorated. Officials are concerned that … «CNN, Oct 14»

Mount Ontake volcano erupts in Japan

… the alert level to three on a scale of one to five. It has warned that debris from the volcano could fall up to four kilometres (2.5 miles) away. More information … «BBC News, Sep 14»

Lava from Kilauea Volcano threatens to cut off community on …

The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory has issued a warning for a Big Island beach community threatened to be cut off by lava flow from Kilauea Volcano. «CNN, Sep 14»

Iceland’s volcano ash alert lifted

An eruption near Iceland’s Bardarbunga volcano that briefly threatened flights has ended, local officials say. The fissure eruption at the Holuhraun lava field … «BBC News, Aug 14»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Volcano [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/volcano>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

Meaning Volcano

What does Volcano mean? Here you find 53 meanings of the word Volcano. You can also add a definition of Volcano yourself

1 |

0 An elevated area of land created from the release of lava and ejection of ash and rock fragments from and volcanic vent.

|

2 |

0 VolcanoA surface feature of the Earth that allows magma, ash and gas to erupt. The vent can be a fissure or a conical structure.

|

3 |

0 VolcanoA vent in the surface of the Earth, from which lava, ash, and gases erupt, forming a structure that is roughly conical.

|

4 |

0 Volcano1610s, from Italian vulcano «burning mountain,» from Latin Vulcanus «Vulcan,» Roman god of fire, also «fire, flames, volcano» (see Vulcan). The name was first applied to [..]

|

5 |

0 VolcanoA vent in the crust of the earth which spits out molten rock, ash, and gases.

|

6 |

0 Volcanoan opening in the Earth’s crust, through which lava, ash, and gases erupt, and also the cone built by eruptions. Read more in the NG Education Encyclopedia

|

7 |

0 VolcanoA break or vent in the crust of a planet or moon that can spew extremely hot ash, scorching gases, and molten rock. The term volcano also refers to the mountain formed by volcanic material.

|

8 |